Myanmar at a glance: 2002-03 · COUNTRY REPORT Myanmar (Burma) February 2002 The Economist...

Transcript of Myanmar at a glance: 2002-03 · COUNTRY REPORT Myanmar (Burma) February 2002 The Economist...

COUNTRY REPORT

Myanmar (Burma)

February 2002

The Economist Intelligence Unit15 Regent St, London SW1Y 4LRUnited Kingdom

Myanmar at a glance: 2002-03OVERVIEWDiscussions between the ruling State Peace and Development Council(SPDC) and the National League for Democracy (NLD) on a possible returnto constitutional government will be protracted. The junta will attempt toplacate international opinion sufficiently to allow more foreign directinvestment without allowing the NLD to resume its role as the electedgovernment. The revamp of top government posts that took place in late2001 may allow the junta more room to manoeuvre in its negotiations withthe NLD and with international donors. Although sparse official figuressuggest that the economy is growing fairly rapidly, food production appearsto be falling and industrial output, apart from the mining and energysectors, is sluggish. Inflation at double-digit rates is pushing down themarket exchange rate of the kyat and there is no prospect of an end to themultiple-currency regime until donors can be persuaded to provide supportfor a devaluation of the official exchange rate.

Key changes from last monthPolitical outlook• The reshuffling of government and military posts in the closing months

of 2001 has not so far produced any change in the junta’s domestic orforeign policies. However, some small concession toward the NLD maywell be offered during 2002-03.

Economic policy outlook• No change is foreseen to the junta’s unsuccessful attempts to control the

economy and stimulate agricultural and industrial production. Theregime’s efforts at controlling inflation and currency depreciation willremain ineffective.

Economic forecast• Officially measured real annual GDP growth will remain above 5%, but

actual growth will be slower. Manufacturing will be hampered by powershortages while energy and mining will enjoy a boom.

The Economist Intelligence UnitThe Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managingoperations across national borders. For over 50 years it has been a source of information on businessdevelopments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide.

The EIU delivers its information in four ways: through our digital portfolio, where our latest analysis isupdated daily; through printed subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual referenceworks; through research reports; and by organising seminars and presentations. The firm is a member ofThe Economist Group.

LondonThe Economist Intelligence Unit15 Regent StLondonSW1Y 4LRUnited KingdomTel: (44.20) 7830 1007Fax: (44.20) 7830 1023E-mail: [email protected]

New YorkThe Economist Intelligence UnitThe Economist Building111 West 57th StreetNew YorkNY 10019, USTel: (1.212) 554 0600Fax: (1.212) 586 0248E-mail: [email protected]

Hong KongThe Economist Intelligence Unit60/F, Central Plaza18 Harbour RoadWanchaiHong KongTel: (852) 2585 3888Fax: (852) 2802 7638E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.eiu.com

Electronic deliveryThis publication can be viewed by subscribing online at www.store.eiu.com

Reports are also available in various other electronic formats, such as CD-ROM, Lotus Notes, onlinedatabases and as direct feeds to corporate intranets. For further information, please contact your nearestEconomist Intelligence Unit office

Copyright© 2002 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. All rights reserved. Neither this publication norany part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by anymeans, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permissionof The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited.

All information in this report is verified to the best of the author's and the publisher's ability. However,the EIU does not accept responsibility for any loss arising from reliance on it.

ISSN 1361-1445

Symbols for tables“n/a” means not available; “–” means not applicable

Printed and distributed by Patersons Dartford, Questor Trade Park, 151 Avery Way, Dartford, Kent DA1 1JS, UK.

Myanmar (Burma) 1

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Contents

3 Summary

4 Political structure

5 Economic structure5 Annual indicators6 Quarterly indicators

7 Outlook for 2002-038 Economic policy outlook9 Economic forecast

14 The political scene

17 Economic policy

19 The domestic economy19 Output and demand21 Employment, wages and prices22 Financial indicators23 Sectoral trends25 Foreign trade and payments

List of tables

10 International assumptions summary11 Forecast summary18 Central government tax revenue18 Interest rates20 Output by state-owned enterprises21 Foreign direct investment22 Consumer prices23 Money supply and credit24 Tourist arrivals25 Merchandise trade balance25 Exports of main commodities26 Imports of main commodities27 Imports by category27 International liquidity

List of figures

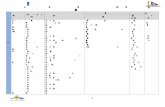

13 Gross domestic product13 Kyat real exchange rate

2 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

21 Inflation22 Exchange rate, 200124 Tourist arrivals

Myanmar (Burma) 3

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Summary

February 2002

The ruling junta (the State Peace and Development Council, SPDC) is likely tocontinue contact with the National League for Democracy (NLD). A trans-itional government may be announced, but the SPDC will aim to retain a keyrole. Power shortages and a tough external environment will slow GDP growthin 2001/02. Inflation is likely to surge and the kyat will remain under severepressure. Any major steps towards political reform would unlock increased aidand investment, lifting GDP growth and helping to stabilise the kyat.

Lieutenant-General Win Myint has been sacked from the SPDC and a numberof government posts have been reshuffled. However, the top SPDC positionshave remained unchanged, and the change in line-up is not expected to usherin any policy changes. Ten of 12 regional military commanders have beenreplaced, and the army’s military intelligence wing has been restructured.Closed-door talks with the NLD have continued, but remain at a confidence-building stage. The SPDC is not expected to hand over power or introducesweeping political reforms. Ethnic minority political leaders have grownincreasingly impatient at their exclusion from the dialogue. An InternationalLabour Organisation (ILO) mission found that the use of forced labour by themilitary remains widespread. A state visit by the president of China hascemented close ties at a time of flux for Myanmar.

Import substitution continues. Budget woes persist, despite rising revenue.Interest rates have turned negative once again.

Although statistics are rare and unreliable, it is clear that economic growth isslowing. Industrial output remains sluggish, except in the mining and energysectors, where some new projects have recently begun operation. Foreigninvestment has slumped as international sanctions against the junta arereinforced by worries about instability and the unfavourable business climate.Inflation and money supply are soaring, while the kyat continues to slide.

Rice exports have increased sharply despite falling rice yields and output. Afishing dispute with Thailand has been resolved. Copper output is rising andprospects for a new gold mining joint venture look good. Tourist arrivals havecollapsed, not just because of the September 11th terrorist attacks on the US.

The trade deficit has narrowed as a result of rapidly rising gas exports. Foreignexchange reserves remain critically low. Japan has resumed some aid projects.

Editors: Ken Davies (editor); Graham Richardson (consulting editor)Editorial closing date: January 29th 2002

All queries: Tel: (44.20) 7830 1007 E-mail: [email protected] report: Full schedule on www.eiu.com/schedule

Outlook for 2002-03

The political scene

Economic policy

The domestic economy

Sectoral trends

Foreign trade andpayments

4 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Political structure

Union of Myanmar

Military council

Following a military coup in September 1988, the State Law and Order RestorationCouncil (SLORC) took all executive power; in November 1997 the SLORC was renamedthe State Peace and Development Council (SPDC)

Chairman of the SPDC, Senior General Than Shwe

The Pyithu Hluttaw (People’s Assembly) was abolished after the military coup in 1988;an election was held for a new People’s Assembly in May 1990, resulting in anoverwhelming victory for the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD), but thejunta has refused to allow parliament to meet; in September 1998 the NLD set up a ten-person “people’s parliament” committee to represent the deputies elected in 1990.Closed-door talks are now taking place between the SPDC and the NLD

May 27th 1990; next election date unknown

The SPDC controls all the organs of state power

Since the military coup, political parties have in theory been permitted to operate on thebasis that they are officially registered, but they face many restrictions. A number oforganisations, most ethnically based, were in armed conflict with the government formany years. Many have now reached an accommodation with the government, althoughsome groups continue armed resistance. The Union Solidarity Development Association(USDA) was set up in 1993 as a welfare organisation and support bloc for the junta

National League for Democracy (NLD); National Unity Party (NUP); Shan NationalitiesLeague for Democracy (SNLD) and other ethnically based parties

Chairman Senior General Than ShweVice-chairman General Maung AyeSecretary-1 Lieutenant-General Khin NyuntSecretary-2 VacantSecretary-3 Vacant

Prime minister & minister of defence Senior General Than ShweDeputy prime ministers VacantAgriculture Major-General Nyunt TinCommerce Brigadier-General Pyi SoneConstruction Major-General Saw TunEnergy Brigadier-General Lun ThiFinance & revenue Khin Maung TheinForeign affairs Win AungIndustry (One) Aung ThaungIndustry (Two) Major-General Saw LwinMining Brigadier-General Ohn MyintTelecommunications, post & telegraphs Brigadier-General Thein Zaw

Kyaw Kyaw Maung

Official name

Form of state

The executive

Head of state

National legislature

National elections

National government

Main political organisations

Main political parties

Main members of the StatePeace & Development Council

Key ministers

Central Bank governor

Myanmar (Burma) 5

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Economic structure

Annual indicators

1997 1998 1999 2000a 2001a

GDP at market prices (Kt bn)b 1,119.5 1,609.8 2,190.3 2,344.5 2,898.6

GDP (US$ bn)b 4.7 4.8 6.4 6.6 4.7

Real GDP growth (%)b 5.7 5.8 10.9c 6.2d 5.0

Consumer price inflation (av; %) 29.7 51.5 18.4 –0.1d 20.0

Population (m)e 45.8 46.5 47.1 47.8 48.5

Exports of goods fob (US$ m) 974.5 1,065.2 1,281.1 1,618.8d 1,758.5

Imports of goods fob (US$ m) 2,106.6 2,451.2 2,159.6 2,134.9d 2,215.6

Current-account balance (US$ m) –412.2 –494.2 –281.8 –242.9 –335.8

Foreign-exchange reserves excl gold (US$ m) 249.8 314.9 265.5 223.0 210.0

Total external debt (US$ bn) 5.1 5.6 6.0 5.6 5.3

Debt-service ratio, paid (%) 7.7 5.5 5.2 7.7 9.5

Exchange rate (av) Kt:US$f 240.5 333.9 340.8 355.3 620.0

January 29th 2002

Kt6.675:US$1

Origins of gross domestic product 1997 % of total Components of gross domestic product 1997 % of total

Agriculture 58.8 Total consumption 89.6

Industry 10.6 Total investment 13.3

Manufacturing 7.5 Increase in stocks –2.2

Services 30.6 Exports of goods & services 0.6

GDP at current prices 100.0 Imports of goods & services –1.3

GDP at current prices 100.0

Principal exports 2000b US$ m Principal imports 2000b US$ m

Pulses & beans 225.3 Machinery & transport equipment 399.2

Teak & other hardwoods 186.5 Base metals & manufactures 218.1

Fish, fish products & prawns 135.0 Electrical machinery 170.3

Metals & ores 45.9 Edible oils 72.1

Rice 32.6 Pharmaceuticals 62.6

Total incl others 1,626.7 Total incl others 2,367.2

Main destinations of exports 2000 % of total Main origins of imports 2000 % of total

Thailand 15.1 Singapore 24.5

US 14.6 Thailand 12.7

India 9.8 South Korea 12.6

China 6.8 China 11.8

Singapore 6.2 Japan 8.8

a EIU estimates.b Financial year (beginning April 1st of year shown). c Data from official statements but no annual Economic Survey has beenpublished since 1998. d Actual. e Mid financial year. f Free-market exchange rates.

6 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Quarterly indicators

1999 2000 20014 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr 3 Qtr 4 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr 3 Qtr

PricesConsumer prices (1995=100) 285.3 270.9 273.4 271.4 265.1 270.8 302.7 348.5 % change, year on year 12.8 3.6 2.4 –1.7 –7.1 0.0 10.7 28.4

Financial indicatorsExchange rate Kt:US$ (av) 6.23 6.35 6.48 6.56 6.68 6.65 6.82 6.77 Kt:US$ (end-period) 6.27 6.39 6.43 6.61 6.60 6.78 6.78 6.66Interest rates (%) Central Bank 12.0 12.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 Deposit 10.5 10.5 9.5 9.5 9.5 9.5 9.5 9.5 Lending 16.0 16.0 15.0 15.0 15.0 15.0 15.0 15.0M1 (end-period; Kt bn) 345.8 382.6 403.9 435.0 465.0 559.6 608.0 n/a % change, year on year 22.6 24.4 31.6 32.1 34.5 46.3 50.5 n/aM2 (end-period; Kt bn) 562.2 618.5 663.1 743.2 800.5 911.5 988.6 n/a % change, year on year 29.7 31.4 37.1 38.8 42.4 47.4 49.1 n/a

Sectoral trendsProduction Ricea (annual totals; ‘000 tonnes) 20,125 ( 20,100 ) ( 20,600b ) Rubber (‘000 tonnes) 12.4 8.9 3.8 3.1 16.1 10.0 4.2 3.6 Tin in concentrates (tonnes) 31 44 42 54 76 75 54 66 Zinc in concentrates (tonnes) 149 113 86 402 612 860 174 129

Foreign trade (Kt m)Exports fob 1,562 1,885 2,948 2,783 2,984 3,148 4,890 3,816Imports cif –3,807 –4,644 –3,876 –3,117 –3,790 –4,117 –6,054 –4,709Trade balance –2,245 –2,759 –928 –333 –806 –969 –1,164 –893

Foreign payments (US$ m)Merchandise trade balance –251.8 –298.0 –109.8 –25.2 –83.2 n/a n/a n/aServices balance 66.1 41.6 36.6 –5.0 –61.2 n/a n/a n/aIncome balance –6.4 –7.9 –8.2 –10.5 –9.6 n/a n/a n/aNet transfer payments 80.7 94.1 69.9 64.1 69.1 n/a n/a n/aCurrent-account balance –111.4 –170.2 –11.5 23.5 –84.9 n/a n/a n/aReserves excl gold (end-period) 266.5 279.5 262.1 273.5 223.0 200.9 246.1 n/a

a Fiscal year, beginning April of year shown. b Estimate.Sources: FAO; International Rubber Study Group, Rubber Statistical Bulletin; Myanmar Central Statistical Organisation, Selected Monthly Economic Indicators; IMF, International Financial Statistics.

Myanmar (Burma) 7

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Outlook for 2002-03

In November 2001 Myanmar’s ruling military junta—known as the State Peaceand Development Council, or SPDC—undertook its biggest governmentreshuffle since 1997. Some six government ministers were removed from office,along with one member of the SPDC’s ruling council, Secretary-3, Lieutenant-General Win Myint. At the same time, ten of the 12 powerful regional militarycommanders (who also sit on the SPDC) were recalled to Yangon. Nominally apromotion—all ten were made lieutenant-general and given new posts—themove may be aimed at cutting ties between the regional commanders and thefiefdoms they once controlled.

The change in government line-up is not expected to herald any major policychanges, as the three most powerful generals—the prime minister and SPDCchairman, Senior General Than Shwe, the SPDC Vice-chairman, GeneralMaung Aye, and Secretary-1, Lieutenant-General Khin Nyunt—have allretained their posts. However, the reshuffle and reorganisation of the armedforces commands may be a sign that the SPDC is tightening its grip inpreparation for the creation of some kind of transitional government. Closed-door talks are continuing with the National League for Democracy (NLD), whichwon an overwhelming victory at the last general election in 1990, but hassubsequently been kept out of power by the junta. It is not clear what proposals,if any, are being discussed by the two sides. However, Razali Ismail, the UNenvoy to Myanmar, who visited the country again in November, has hinted inrecent months that the junta may be preparing for the formation of atransitional council including more civilian members. Such a body could be inpower for several years while work on a new constitution is completed, clearingthe way for a fresh election. For its part, the NLD may now be willing torescind its claim to the right to form a government immediately, in exchangefor some limited participation in government.

However, even if such a transitional government is announced, sweepingpolitical reform remains unlikely. The slow release of political prisoners inrecent months suggests that the SPDC will keep such prisoners as bargainingpawns for its negotiations with international donors, as well as with the NLD.Although the NLD has been able to reopen some offices and to resume someparty activities, its activities remain heavily restricted. The NLD leader, AungSan Suu Kyi, remains under house arrest, while other top NLD leaders are stillunder military surveillance.

Even those SPDC members who favour the current talks do not want to see themilitary loosen its grip on the country. Instead, it appears that the SPDC hopesit can reduce international pressure by forming a transitional government,while at the same time securing future military domination of the politicalscene through influencing a new constitution and the outcome of a freshelection. A future transitional government might include a token civilianpresence, but would probably be dominated by military leaders or their allies.The SPDC can also be expected to seek a continued strong role for the militaryvia the new constitution. For some years a junta-appointed committee hasbeen working on a new constitution, one that enshrines a strong central role

Domestic politics

8 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

for the military, including reserving seats in parliament for the armed forcesand setting aside key government ministries for military appointees. The juntahas also indicated in the past that it plans to hold a fresh election once thenew constitution is in place. Accordingly, the SPDC has built up a pro-militarypolitical grouping, the Union Solidarity Development Association (USDA),which now has around 16m members, according to official estimates. In 2001the junta also sought to revamp both a military veterans association and theNational Unity Party, the political vehicle that lost the 1990 election.

At first sight, an interim government on such terms appears to have little tooffer the NLD. Taking part in such a government would certainly be a high-riskstrategy. For example, although the party remains popular and can be expectedto perform well if the SPDC does hold an election, setting aside seats for themilitary would almost certainly ensure that the NLD is unable to repeat itslandslide victory of 1990. However, there does appear to be a growing feelingwithin the NLD that modest reform is better than no reform at all.

Ethnic minorities, some of which are still in military conflict with the centralgovernment, are growing increasingly dissatisfied at their exclusion from thetalks. A wide range of ethnic leaders, including those who have signed cease-fires with the SPDC and some of those who are continuing armed resistance,are hoping to work together in 2002 to push for tripartite dialogue. Ethnicminority rebellions are likely to persist until such groups can be brought intothe dialogue process, and while military offensives by the SPDC continue.

An International Labour Organisation (ILO) mission visiting in Novemberfound that the use of forced labour remains widespread. External pressure onthe junta to bring a stop to such practices is likely to continue. The EU and theUS are unlikely to lift sanctions and other measures taken against the SPDCuntil there are concrete signs of change (such as the drafting of a road map forpolitical reform or the release of all remaining political prisoners).Nevertheless, despite the lack of effective political reform, the UN and otherinternational bodies appear to be taking a wait-and-see approach to the currentdialogue. Closer to home, a number of Asian nations, particularly Malaysia,have been actively supportive of the current confidence-building talks, andMyanmar-Malaysia ties appear to be deepening. Japan, too, has resumed somesmall-scale aid projects, indicating that more funds will be disbursed if thereare significant steps towards political reform.

Economic policy outlook

The junta’s economic policies continue to be dominated by central planningand efforts at import substitution. Development of the agriculture and energysectors remains a priority, in order to improve domestic supplies and producesurpluses for export. The junta sees self-sufficiency in food production inparticular as a key factor in ensuring social stability, but few new policies havebeen introduced to stimulate these sectors.

The junta has been unable to overcome a persistent huge budget deficit(although the scale of the deficit is not reflected in government statistics).

Policy trends

International relations

Myanmar (Burma) 9

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Faced with a lack of capital to fund its budget deficits, the junta has slashedspending on areas such as health and education. State infrastructureinvestment has continued, but has been partly funded by the use of forcedlabour on public works projects. As its ability to collect revenue is limited—theuntaxed grey economy is huge—the SPDC will continue to print money tofund its deficit, resulting in renewed inflationary pressure.

Myanmar maintains a dual exchange-rate system, with an unrealistic officialexchange rate of around Kt6.7:US$1 co-existing with a market exchange ratethat plunged in 2001 from about Kt410:US$1 in January to Kt720:US$1 by theend of the year. The SPDC has made clear that it will not undertake anadjustment of the inflated official exchange rate without external assistance.

An end to the political impasse would also bring an end to the aid freeze, theremoval of sanctions on new investment imposed by the US in 1997 (andextended by the president, George W Bush, in May 2001) and an end to touristboycotts. Any government in which the NLD had a significant role in policyformation could also be expected to undertake sweeping economic reformswith the assistance of multilateral institutions. Such developments wouldresult in a faster rate of growth and a much stronger external environmentthan the Economist Intelligence Unit is currently forecasting.

Economic forecast

We expect global output to fall further in the first quarter of 2002 after havingshrunk in the last quarter of 2001. The US and Japan will remain in recessionthrough the first quarter of 2002. Growth in the US—a key destination forMyanmar’s garment exports—will then pick up quite rapidly in the second halfof 2002. Japan’s economic performance, however, will remain poor in 2002.We forecast that Japan’s GDP will contract by 1.4% in 2002 before returning tomodest growth in 2003. Myanmar's key export markets in Asia—Thailand,India and China—will experience more rapid growth in 2002 than in 2001,although from a weak base. Output in Singapore will contract by 0.8% in 2002following an estimated contraction of 2.2% in 2001. Sluggish growth in Asiawill further reduce Myanmar’s dwindling inflows of foreign investment, muchof which now comes from within the region.

Aside from garments, Myanmar’s main exports will remain agriculturalcommodities such as pulses, fish products, timber and rubber, and othernatural resources, particularly natural gas and metals. There will be a modestupturn in prices in 2002-03 for a number of these commodities, including riceand rubber, thanks to the slow improvement in world demand from mid-2002onwards. However, prices of other commodities important to Myanmar, suchas copper, will continue to fall in 2002, damping Myanmar’s export earnings.Energy import dependent Myanmar will benefit from the drop in oil prices in2002, but oil imports will remain high in volume terms compared withhistorical levels, the result of continued disruption of domestic power supplies.

The external environment for Myanmar could improve dramatically if there isfurther marked progress on the political front. Myanmar’s exports to the USand EU are currently curtailed by the loss of many trade privileges normally

International assumptions

10 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

accorded to developing countries. The EU has removed the generalised systemof preferences (GSP) on agricultural and industrial goods because of Myanmar’spoor labour welfare standards. The US imposed sanctions banning all newinvestment in Myanmar by US firms in 1997.

International assumptions summary(% unless otherwise indicated)

2000 2001 2002 2003

Real GDP growthWorld 4.7 2.2 2.4 4.2OECD 3.8 0.9 0.9 3.0EU 3.3 1.5 1.3 2.5

Exchange rates (av)¥:US$ 107.8 121.5 128.8 123.5US$:€ 0.924 0.896 0.960 1.015SDR:US$ 0.758 0.785 0.771 0.751

Financial indicators€ 3-month interbank rate 4.48 4.28 3.13 4.60US$ 3-month Libor 6.53 3.78 1.91 5.07

Commodity pricesOil (Brent; US$/b) 28.5 24.3 18.3 20.2Gold (US$/troy oz) 279.3 268.8 255.0 250.0Food, feedstuffs & beverages

(% change in US$ terms) –6.1 –1.0 11.9 13.4

Industrial raw materials (% change in US$ terms) 13.4 –9.7 1.3 14.8

Note. Regional GDP growth rates weighted using purchasing power parity exchange rates.

The junta ceased publishing its annual national accounts data in 1998, andestimating growth and conditions in various sectors involves employing a greatdeal of anecdotal evidence. However, it appears clear that Myanmar’s economyis on a slowing trend. After surging by 10.9% in 1999/2000 (fiscal year, April-March), real GDP growth slowed to 6.2% in 2000/01 according to the latestIMF data. (There are some doubts over the leap in GDP in 1999/2000, despite agood performance by the agricultural sector, but we have now incorporated theofficial figures for GDP growth in 1999/2000 and 2000/01.) The SPDC itself isforecasting a slowdown in GDP over the next five years. In late NovemberLieutenant-General Khin Nyunt stated at a conference in Yangon that real GDPwould average 6% during the current 2001/02-2005/06 five-year plan, downfrom annual average growth of 8.4% during the previous five-year period.

We expect Myanmar’s real GDP growth to slow to 5% in 2001/02, pickingup slightly to 5.1% in 2002/03 as global demand recovers. After twosuccessive good harvests of rice and other key crops, agricultural output was hitby flooding in 2001/02. There will be some slight gains in agricultural outputin 2002/03 as the junta will continue to use subsidies and incentives to bringmore land into production. However, any gains will be constrained bycontinued shortages of fertiliser and other key inputs.

Overall industrial-sector growth will remain relatively slow in 2002-03,averaging around 6.3% year on year. Erratic and costly power suppliescombined with continued weak external and domestic demand and sluggish

Economic growth

Myanmar (Burma) 11

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows will continue to hold back growth ofthe industrial sector. During the first six months of 2001/02, FDI approvals fellby 90.3% year on year to only US$8m. A slight upturn in FDI is likely in2002/03 as key Asian economies—the main investors in manufacturing inMyanmar—experience stronger growth. However, without sweeping economicreforms, foreign investor interest in Myanmar will remain muted.

While the outlook for the manufacturing sector remains grim, the mining andenergy sector will continue to expand relatively rapidly in 2002-03. Exportearnings from major new energy projects—including the Yadana and Yetagunoffshore gasfields—are now increasing, albeit remaining below target becauseof slack demand from Thailand, the end-destination for Myanmar’s gas. Anumber of mining projects are also now on stream, including the Monywacopper mine, and earnings from exports of metals and ores are rising, albeitfrom a low base. Again, however, power shortages and weak domestic demandremain problems.

Growth in services will remain slack in 2002-03. Strong inflation (not fullyreflected in the official data) combined with widespread poverty will continueto constrain retail spending. The tourism sector will pick up towards the end ofthe forecast period as arrivals from neighbouring countries start to recover.However this will be from a very low base and earnings will remain far belowtheir potential levels—unless political reforms occur, resulting in an end to thetourist boycott.

Forecast summary(% unless otherwise indicated)

2000a 2001a 2002b 2003b

Real GDP growthc 6.2d 5.0 5.1 5.9

Gross fixed investment growthc 7.0 6.0 6.9 7.0

Gross agricultural production growthc 5.0 3.2 3.2 4.2

Unemployment rate (av) 5.8 5.1 4.7 4.2

Consumer price inflation Average –0.1c 20.0 30.0 6.2 Year-end –6.3c 43.0 19.8 5.5

Short-term interbank rate 15.3c 15.0 15.0 16.0

Government budget balance (% of GDP)c –0.3 –0.3 –0.1 –0.1

Exports of goods fob (US$ bn) 1.6c 1.8 1.9 2.3

Imports of goods fob (US$ bn) 2.1c 2.2 2.4 2.8

Current-account balance (US$ bn) –0.2c –0.3 –0.3 –0.2 % of GDPe –3.7 –7.2 –5.8 –4.0

External debt (year-end; US$ bn) 5.6 5.3 5.6 5.8

Exchange ratesf

Kt:US$ (av) 355.3 620.0 800.0 931.5 Kt:¥100 (av) 329.7 525.3 710.7 838.1 Kt:€ (av) 328.2 571.8 878.4 1,050.5 Kt:Bt (av) 8.86 14.34 20.19 23.39

a EIU estimates. b EIU forecasts. c Financial year (beginning April 1st of year shown). d Actual. e Atfree-market exchange rate (which understates size of GDP). f Free-market exchange rates.

12 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

A good harvest and a drop in rice prices brought a marked slowdown ininflationary pressures in 2000. That downturn proved short-lived, however.From mid-2001 the low base period, the continued monetisation of the fiscaldeficit, and supply-side factors such as rising food prices and a leap in importedprice pressures, brought a surge in inflation. We estimate that Myanmar’sconsumer price inflation averaged around 20% year on year in 2001, with afurther increase to an annual average of 30% year on year likely in 2002. Thereal picture is even worse, as official data severely understate the degree ofupward pressure on prices. In 2003 inflationary factors are expected to weakenas the government is forced to take measures to restrain price rises for fear ofendangering social stability.

The SPDC’s efforts to stabilise the slumping free-market exchange rate havehad little success, and by end-December the currency had reached Kt723:US$1,from a low of Kt850:US$1 in mid-May. The free-market exchange rate has beenundermined by acute foreign-exchange shortages. Weak reserves, highinflation and political uncertainty will continue to hold down the value of thefree-market kyat during 2002/03. Only a marked improvement in the politicalclimate (which would herald a rise in aid and investment inflows) would seethe kyat strengthen significantly. We estimate that the free-market exchangerate averaged Kt620:US$1 in 2001 (Kt690:US$1 in the financial year 2001/02).Despite the possible modest improvement in export earnings in 2002, weexpect the free-market rate to depreciate further to around Kt800:US$1 in2002, the result of high inflation and continued shortage of reserves.

The SPDC will remain reluctant to realign the grossly overvalued officialexchange rate, which has averaged around Kt6.3-6.7:US$1 for the last fewyears. We believe that the junta is unlikely to undertake any sharp realignmentof the official rate without substantial international assistance (the junta hasspoken of needing as much as US$1bn-3bn). The SPDC would have little togain from a devaluation of the official rate in the short term, as most private-sector trade is already conducted at the free-market rate, limiting any potentialboost to exports from devaluation, while debt repayments would become moredifficult. A devaluation of the official rate would also cause financial problemsfor some state-owned enterprises, which are currently able to purchase foreignexchange at the inflated official rate.

The SPDC is also unlikely to withdraw foreign exchange certificates (FECs), aunit introduced at parity with the dollar in 1993 but now trading slightly belowthe free-market kyat. The amount of FECs in circulation is believed to be morethan double total foreign-exchange reserves, meaning that the SPDC has insuf-ficient resources to back the unit. We therefore expect the multiple exchange-rate regime to be maintained throughout the forecast period. The NLD has,though, made clear its commitment to broad structural reforms including anadjustment of the exchange-rate regime if the political situation changes.

Myanmar’s exports experienced something of a boom in 2001, jumping 80.1%year on year during January-October in kyat terms, easily outpacing imports.The trade data must be viewed with caution: trade figures are subject tosubstantial revision and are distorted by widespread smuggling and money

Inflation

Exchange rates

External sector

Myanmar (Burma) 13

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

laundering. Exports appear to have been boosted by a leap in gas exportswhen the massive Yadana and Yetagun offshore projects came on stream.We estimate that gas earnings overtook pulses to become Myanmar’s singlelargest source of export revenue in 2001. Exports of pulses, rice andhardwoods also rose strongly in value terms in the first ten months of 2001despite sluggish demand in some key regional export markets. Imports alsorose strongly in January-October, up 26.2% year on year, as the governmentcontinued to import fuel to compensate for power shortages.

World prices for some of Myanmar’s key exports, including rice and rubber,will increase in 2002-03, while exports of gas from the Yadana and Yetagungasfields and from mining projects will also increase steadily. Imports willremain stagnant in 2002, thanks to slack domestic demand and the weaknessof the kyat, picking up more strongly in 2003. As a result, the merchandisetrade deficit will remain relatively small compared with 1990s levels.

However, the services balance, which recorded a tiny surplus of US$12.1m in2000, is estimated to have fallen into deficit in 2001 for the first time in 16years. This deficit is forecast to persist in 2002-03 because of an expected sharpdecline in tourism receipts. Current inward transfers—probably dominated byremittances from overseas workers—are now a vital source of foreign exchangeand a key factor in controlling the current-account deficit. The tougher climatefor Myanmar workers in Thailand resulting from both the crackdown on illegalworkers and sluggish growth there will keep such earnings well below late1990s levels during 2002-03.

As a result of these trends, we expect the current account to remain in deficit in2002-03. Sluggish inflows of foreign investment and limited access to otherforms of international capital will ensure that foreign-exchange reservesremain worryingly low. As a result, without political reform and an end to theinternational aid freeze Myanmar will remain on the brink of a balance-of-payments crisis throughout 2002-03. The SPDC is likely to deal with thisproblem by continuing to imposing a mix of ad-hoc administrative controls ontrade and foreign exchange and running up further arrears on its external debt.

14 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

The political scene

On November 9th the ruling military junta, known as the State Peace andDevelopment Council (SPDC), undertook the largest change in governmentline-up since 1997. One member of the SPDC and six ministers in the SPDC-appointed government were sacked or allowed to retire. The two sackedofficials were Lieutenant-General Win Myint, Secretary-3 in the SPDC, and thedeputy prime minister and minister of military affairs, Lieutenant-General TinHla. In addition, the minister for culture, Win Sein, the minister for co-operatives, Aung San, the minister for immigration and population, Saw Tun,together with deputy prime ministers Vice-Admiral Maung Maung Khin (alsohead of the Myanmar Investment Commission) and Lieutenant-General TinTun, were all described as “retiring”, some for health reasons.

Military intelligence officials indicated in mid-November that the three deputyprime minister posts would be left empty. However, on November 16th theSPDC announced new appointments to the three other vacant ministerialpositions—culture, co-operatives and immigration. Tin Win was moved fromthe Prime Minister’s Office to become both minister of labour and minister ofculture. (The previous minister of labour, Major-General Tin Ngwe, was movedto the Prime Minister’s Office.) Another minister at the Prime Minister’s Office,Lieutenant-General Tin Ngwe (no relation of Major-General Tin Ngwe), wasmoved to become Minister of Co-operatives. Finally, the minister of socialwelfare, relief and resettlement, Major-General Sein Htwa, was also given thepost of minister of immigration and population.

While the ministerial posts were quickly filled, the post of Secretary-3 in theSPDC was still vacant as of mid-January. It is likely that the Secretary-3 postmay be left empty, as with the post of Secertary-2, which was left vacantfollowing the death in a helicopter accident of Lieutenant-General Tin Oo inFebruary 2001. There is speculation that the Secretary-2 and Secretary-3 postshave not been filled due to disagreements over the appointments between twofactions within the SPDC, loyal to the SPDC vice-chairman, General MaungAye, or to the military intelligence head and SPDC Secretary-1, Lieutenant-General Khin Nyunt. It is not clear how the recent changes have affected thesetwo factions. Despite real differences, the two sides seem to be keeping anuneasy balance of power, and there is little evidence following the newappointments that one side has gained at the expense of the other.

As in 1997, the changes in government line-up are expected to have little realimpact on policymaking. The SPDC, rather than the government, makes allkey policy decisions, and there has been no significant change in the SPDCline-up. The three most powerful figures in the SPDC—the prime minister andSPDC chairman, Senior-General Than Shwe, the SPDC vice-chairman, GeneralMaung Aye, and Secretary-1, Lieutenant-General Khin Nyunt—have allretained their posts.

Instead, there is speculation that the reshuffle reflects an attempt by the SPDCto at least be seen to be tackling corruption, following pressure from regionalallies such as Malaysia to improve the country’s business climate. Both General

Business as usual followinggovernment changes

The government isreshuffled

Myanmar (Burma) 15

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Win Myint and General Tin Hla appear to be under investigation forcorruption. General Win Myint was head of the Union of Myanmar EconomicHoldings (UMEH), a sprawling SPDC-owned enterprise involved in sectors suchas mining, fishing and banking, while General Tin Hla also had businessconnections. A number of government and SPDC figures sacked in 1997 werealso investigated for corruption. However, corruption is rife in Myanmar at alllevels of business and government, and the removal of a few ministers is notlikely to alter this.

The military also underwent a big shake-up in November. Ten of the country’s12 powerful regional military commanders (who all sit on the 16-memberSPDC) were recalled to Yangon. The only two regional commanders to retaintheir posts were the coastal region commander, Brigadier-General Aye Kywe,and the south-eastern commander, Brigadier General Myint Swe. On December18th ten new regional military commanders were appointed, drawn fromlower-level military ranks. In mid-December the 29 units of the powerfulMilitary Intelligence (MI) wing were also restructured into 12 MI battalions,stationed alongside the 12 regional military commands. In addition, four newbureaux of special operations have been formed under the Yangon defenceministry to supervise the regional and divisional military commands.

In a press conference on November 17th Major-General Kyaw Win, deputyhead of military intelligence, reported that the restructuring was simply meantto bring “new blood” into the armed forces. In theory, the move is a step up forthe ten former regional commanders, all of whom have been promoted tolieutenant-general. However, there may be more to the reorganisation. The topSPDC leaders may be trying to sever the former regional commanders’ ties totheir regional fiefdoms—and to the forces under their control. In addition, thecreation of the regional bureaux and the recall to Yangon of ten of the 12military commanders who sit on the SPDC may be an attempt to create somedistance—at least in appearance—between the military and government.

However, there is still no real separation between the SPDC, the governmentand the military. The SPDC controls government appointments and manyministers hold senior military rank. The SPDC itself is entirely comprised ofmilitary and intelligence leaders—including the ten former regionalcommanders. While four of the former regional commanders were appointedas heads of the new bureaux of special operations, the other six were appointedto a raft of important military posts. For example, in mid-November the formertriangle region military commander, Lieutenant-General Thein Sein, wasappointed adjutant general—a post previously held by the sacked General WinMyint. The former north-east commander, Major-General Tin Aung Myint Oowas given the post of quartermaster general, previously held by the sackedGeneral Tin Hla.

In November 2001 the UN special envoy to Myanmar, Razali Ismail, made hisfifth visit of the year. Mr Razali has been closely involved in trying to keep upthe momentum of ongoing talks between the SPDC and the National Leaguefor Democracy (NLD). The NLD won the last election, held in 1990, but theSPDC has refused to hand over power. Since October 2000 the SPDC has been

Despite a shake-up, themilitary still calls the shots

Little progress in talkswith the NLD

16 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

engaged in secretive, confidence-building talks with the leader of the NLD,Aung San Suu Kyi, who remains under house arrest in Yangon. During therecent trip, Mr Razali met with both senior SPDC generals and top NLD leaders,including Aung San Suu Kyi. Following the talks, he declared that he remained“optimistic”, despite the lack of progress after more than a year of dialogue.

Concern is growing within the international community—and the NLD—atthe lack of concrete progress. The SPDC appears to be doing just enough tokeep the contact going and to prevent an intensification of internationalpressure. The last year has seen the lifting of some restrictions on NLDactivities. An NLD spokesperson, U Lwin, reported in late October that theparty's Central Executive Committee was able to have regular meetings and tovisit the party’s headquarters, while party offices have been reopened in 24constituencies in Yangon Division. In addition, some 200 political prisoners—mainly NLD members—were released in 2001. However, the NLD appears to begrowing impatient at the slow pace of change. At a party gathering onJanuary 4th, the NLD issued a statement demanding the release of Aung SanSuu Kyi along with all remaining political prisoners. (The NLD estimates thatmore than 800 of its members remain in jail, while Amnesty Internationalestimates that 1,500 political prisoners remain behind bars in Myanmar.) TheNLD statement also urged faster progress in the talks and called for theinvolvement of ethnic minority representatives.

Despite the modest signs of thaw, there is little expectation of swift politicalreform. Virtually nothing is known about the substance of the closed-doortalks, but the SPDC is not expected simply to recognise the 1990 electionvictory and hand over power. Rather, over the next two or three years theSPDC may form a transitional government that will include more civilianmembers, perhaps including some representatives from the NLD. At the sametime, the SPDC would like to complete a new constitution, clearing the way fora fresh election. Even if such a road map for political reform is announced, theSPDC can be expected to seek continued strong military control, for exampleby setting aside seats in any future parliament for armed forces appointees.

In November Senior General Than Shwe informed the Japanese prime minister,Junichiro Koizumi, that the SPDC would not prevent Aung San Suu Kyi playinga key role in government if she were elected. However, the SPDC appears to betaking steps to sideline the NLD in any future election. The SPDC has alreadyformed a range of pro-military groups to provide it with electoral support. Keyamong these organisations is the Union Solidarity Development Association(USDA), which now has some 16m members according to the SPDC (includingcivil servants and others who are pressured to join). Reorganisation of theNational Unity Party (NUP, the party that represented the military junta in the1990 election) also began in 2001. In late October an NUP party conferencewas held to discuss fund-raising and recruitment.

Ethnic minority leaders are becoming increasingly impatient at the continuedrestrictions on ethnic parties and with the lack of inclusion of any ethnicminority representatives in the NLD-SPDC dialogue. In October the UN’sspecial rapporteur for human rights in Myanmar, Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, held a

There is little prospect ofrapid political reform

Ethnic minority leadersremain dissatisfied

Myanmar (Burma) 17

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

meeting with leaders of five ethnic groups who reported that ethnically basedpolitical parties—including those of the Mon, Chin and Karen—were stillunable to operate freely. Ethnic leaders have called for a UN-backed conferenceof all ethnic political leaders, including the leaders of rebel groups and thosethat have signed ceasefires with the SPDC, to enable them to decide on acommon position and to push for their participation in future talks. During ameeting with ethnic leaders in November Mr Razali indicated that he supportedthe holding of a broad-based meeting of ethnic minority leaders in 2002.

Following a monitoring visit in October, the International Labour Organisation(ILO) reported that forced labour remained widespread in areas under militarycontrol. The SPDC has rejected this finding, although independent sourcessuggest that forced labour is continuing. In November, SPDC officials com-mented that they would continue to work with the ILO, but rejected the ILO’srequest to establish a permanent mission in Myanmar.

In mid-December the president of China, Jiang Zemin, visited Myanmar,becoming the first Chinese head of state to do so since 1988. During the tripMr Jiang signed co-operation agreements on areas including investment, oilproduction and agriculture, and concluded deals worth around US$100m inagriculture, infrastructure and human resources development. China has beenone of the junta’s closest allies over the past decade, supplying military trainingand considerable investment. Myanmar has also become a key trading partnerfor China’s Yunnan province, especially because the Chinese government istrying to develop the country’s relatively poor inland regions. China’s leadersare likely to want to maintain ties and influence with the SPDC in the event ofany political changes in Myanmar, particularly as the SPDC seems to bemoving closer to ASEAN stalwarts such as Malaysia.

Economic policy

A recent study of Myanmar’s economy by the Asian Development Bank (ADB)highlighted a range of economic policy shortcomings, including printingmoney to fund chronic budget deficits and using administrative controls todeal with foreign-exchange shortages. Rather than tackling economic reform,the SPDC has continued its inward-looking policies aimed at attaining greatereconomic self-reliance. The SPDC hopes to increase domestic production ofitems such as edible oils, fertilisers and paper in a bid to reduce reliance onimports. For example, during the 2001/02-2005/06 five-year plan, the SPDCplans to build 15 paper and pulp mills with a capacity of 50-500 tonnes/day,eliminating the need for paper imports. However, the SPDC has done little toencourage such industries, which are hampered by a shortage of investmentand a tough business climate.

Preliminary data from the Central Statistical Organisation (CSO) show a 19.9%year-on-year rise in central government tax revenue in 2000/01 (April-March),to Kt68.6bn (US$10.3bn at the hugely overvalued official exchange rate, or

The ILO keeps up thepressure

China ties remain strong

Import substitutioncontinues

Budget woes persist despiterising revenues

18 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

US$110.6m at the 2001 average free-market exchange rate). The main gainscame in commodities and services tax and profit tax, up 34.6% and 46.1% yearon year respectively, more likely to be the result of improved tax compliancerather than any upturn in the economy. Income tax revenue fell by 3.1% yearon year in 2000/01, while revenue from customs duties dropped 0.3% asimports declined (see Foreign trade and payments).

The SPDC has not yet produced a full budget breakdown for all levels ofgovernment in 2000/01. In 1999/2000, the budget deficit reached a high 5% ofcurrent-price GDP, at Kt109.7bn (US$16.4bn at the official exchange rate orUS$176.9m at the free-market rate). Despite the jump in central governmenttax revenue in 2000/01, little improvement is expected in the overall deficitlevel since the SPDC has already severely compressed spending on areas such ashealth and expenditure, leaving little room for further cuts.

Central government tax revenue(Kt m, unless otherwise indicated)

Apr-Jun Apr-Jun1999/2000 2000/01 % change 2000/01 2001/02 % change

Tax revenue 57,242 68,615 19.9 9,282 12,206 31.5 Commodities & services tax 24,591 33,089 34.6 3,256 5,250 61.2 Income tax 16,931 16,410 –3.1 2,455 2,117 –13.8 Profit tax 4,234 6,187 46.1 600 820 36.7 Customs tax 5,174 5,158 –0.3 1,301 1,982 52.3 Lottery & stamp duty 6,312 7,771 23.1 1,670 2,037 22.0

Source: Central Statistical Organisation, Selected Monthly Economic Indicators.

For a brief period in 2000 Myanmar’s interest rates turned strongly positive inreal terms. However, after a surge in inflation through the second half of 2001(see The domestic economy), real interest rates are now steeply negative oncemore. As a result, savings rates are expected to remain low, which is bad news forMyanmar’s under-capitalised banks. According to the Asian Development Bank,the domestic savings rate averaged only 12.3% during 1988/99-1999/2000.

Interest rates(%)

1999 2000 20013 Qtr 4 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr 3Qtr 4 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr 3 Qtr

Central bank ratea 12.0 12.0 12.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 10.0 10.0

Deposit rate (6-month) 10.5 10.5 10.5 9.5 9.5 9.5 9.5 9.5 9.5

Lending rate (working capital, state-owned enterprises) 16.0 16.0 16.0 15.0 15.0 15.0 15.0 15.0 15.0

a End-period.Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics.

Interest rates turn negativeagain

Myanmar (Burma) 19

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

The domestic economy

Output and demand

There is considerable uncertainty over Myanmar’s exact rate of economicgrowth. The State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) claims that GDProse by 10.9% year on year in real terms in the 1999/2000 financial year (April-March). That figure is believed to be an overestimate, although it has now beenaccepted by the IMF and has been incorporated—with severe reservations—into the Economist Intelligence Unit’s forecasts. The SPDC has not published afull set of national accounts for more than three years. Although accurate dataare not available, there are clear signs that the economy is on a slowing trend.In late November Lieutenant-General Khin Nyunt stated at a conference inYangon that real GDP growth was forecast to average 6% during the current2001/02-2005/06 five-year plan, down from annual average growth of 8.4%during the previous five-year period. The IMF’s International Financial Statisticsreports that real GDP growth slowed to 6.2% year on year in 2000/01 (presum-ably from data supplied by Myanmar’s Central Statistical Organisation, CSO).

We expect GDP growth to slow further to 5% in 2001/02. No strong upturn isexpected in the agricultural sector (which accounts for about 58% of GDP)after two years of fairly good harvests. At the same time, widespread power cutsare leaving manufacturers reliant on costly imported diesel, raising productioncosts. In 2002 Myanmar’s key regional trade and investment partners willexperience slower growth, while weakening demand in the US will hitMyanmar’s garment export sector.

Repeated power blackouts have left manufacturers reliant on expensive diesel-powered generators. At the same time, external demand for Myanmar’s limitedrange of manufactured products has been hampered by international sanctionsand boycotts, while regional demand is expected to weaken further in 2002.Changeable domestic regulations, corruption and shortages of foreign exchangealso remain headaches for manufacturers. As a result, overall industrial output isexpected to remain sluggish this year. A full assessment is impossible, as theSPDC does not publish regular industrial output data, only data on the outputof selected state-owned industries.

Nevertheless, there are some areas where output is reasonably buoyant, notablyenergy and mining, where a number of major projects have recently come onstream (see Sectoral trends). In addition, there has been a modest increase instate and private investment in some import-substitution industries such asrefined edible oils and paper. Paper output by state enterprises rose 21.4% yearon year during the first five months of 2001/02 (April-August), according toCSO data. In late 2001 the China Metallurgical Construction (Group)Corporation held a ground-breaking ceremony for a US$90m bleached pulpfactory which uses bamboo as its raw material. The project is a joint venturewith Myanmar Paper and Chemical Industries, a state-owned enterprise underthe Ministry of Industry (One). Scheduled for completion in 2004, the projectis expected to produce 200 tonnes of pulp per day. Another 14 more paper

Economy is on a slowingtrend

Industrial output remainssluggish

20 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

mills are planned under the SPDC’s current five-year plan, to reduce relianceon imported paper products.

Output by state-owned enterprises(tonnes, unless otherwise indicated)

Apr-Aug Apr-Aug1999/2000 2000/01 % change 2000/01 2001/02 % change

Cotton yarn (’000 lb) 10,658 13,401 25.7 4,885 5,238 7.2

Cotton fabrics (‘000 yards) 21,044 25,561 21.5 10,249 9,739 –5.0

Paper 15,760 17,087 8.4 6,970 8,463 21.4

Cement 350,784 418,923 19.4 147,154 156,749 6.5

Sugar 29,560 90,302 205.5 – – –

Source: Central Statistical Organisation, Selected Monthly Economic Indicators.

Obstacles to trade and investment

Trade restrictions: Additional restrictions were imposed on imports in September2000, with traders limited to importing Kt1m/month. This came on top of restrictionson both exports and imports imposed in March 1998, under the terms of which onlyprescribed items may be imported. Importers must purchase essential imports beforepermission is given to import selected non-essential items. The junta also banned privateexports of key commodities.

US sanctions: In April 1997 the US banned all new investment in Myanmar by UScompanies.

US divestment laws: One US state (Massachusetts) has proposed a bill requiring thestate’s pension fund to divest from companies that do business with Myanmar. The citycouncils of Los Angeles and Minneapolis have already passed similar measures. Themove follows a Supreme Court ruling overturning the Massachusetts selectivepurchasing law; this imposed financial penalties on any firm bidding for state contractsthat did business with Myanmar.

EU restrictions: In March 1997 the EU withdrew generalised system of preferences(GSP) benefits on agricultural goods. Myanmar had already lost GSP on industrialgoods.

Canadian restrictions: In August 1997 Canada removed Myanmar’s GSP benefits.

Consumer boycotts: Active and well-organised consumer boycott campaigns havecontributed to the decision by a number of international companies to pull out ofMyanmar or to cease sourcing goods from there.

During the first six months of 2001/02, foreign direct investment (FDI)approvals fell 90.3% year on year to only US$8m. FDI approvals collapsed inthe late 1990s as a result of the Asian economic crisis, combined withinternational sanctions, concerns over political stability and the poor businessclimate in Myanmar. There was a very modest upturn in 2001/02, when FDIapprovals reached US$231.4m, but first-half data suggest that a drop in overall

Foreign investment slumpsagain

Myanmar (Burma) 21

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

approvals is likely during the current financial year. Myanmar’s neighbours—now key investors—are expected to experience an economic slowdown in 2002which is likely to limit FDI inflows in Myanmar even further. Foreign investorswill remain concerned by the potential for political risk, as highlighted byeight major pension funds in December. The eight, including top Europeanpension funds such as Jupiter Asset Management, responsible for a combinedUS$560bn in assets, hinted that they avoid allocating funds to investments inMyanmar, warning companies that investing in Myanmar “poses risks toshareholders”.

Foreign direct investment(US$ m, unless otherwise indicated)

Apr-Sep Apr-Sep Apr-Sep1999/00 2000/2001 % change 2000/01 2001/02 % change

Manufacturing 13.1 77.4 490.8 24.3 8.0 –67.0

Oil & gas 5.3 47.6 798.1 47.6 0.0 –

Transport 0.0 2.5 – 0.0 0.0 –

Hotels & tourism 15.5 5.3 –65.8 0.0 0.0 –

Mining 18.5 1.1 –94.0 0.6 0.0 –

Total incl others 55.6 184.3 231.4 82.4 8.0 –90.3

Source: Central Statistical Organisation, Selected Monthly Economic Indicators.

Employment, wages and prices

There was a marked upturn in inflation in the first nine months of 2001according to data from the CSO, with consumer price inflation averaging 13%year on year. There was a surge in inflation from mid-year, with consumer priceinflation averaging 34.6% year on year in September. The rise is partly a cor-rection following a slump in inflation in 2000, when good harvests brought adrop in food prices (the food subsector has the heaviest weighting in the index).However, the depreciation of the kyat in 2001 also sharply increased importprice pressures (see Financial indicators), and all sectors, including fuel, clothingand housing, experienced a strong upturn in inflation in January-September.

Inflation surges again

22 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

The official data are believed to understate the actual rate of inflation. Thequick feed-through of import price inflation suggests that inflation may havebeen higher than expected in 2001. As a result, since our last main report wehave revised up our estimate for consumer price inflation in 2001 to an annualaverage of 20%.

Consumer prices

1999 2000 20011 Qtr 2 Qtr 3 Qtr 4 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr 3 Qtr 4 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr 3 Qtr

Yangon index (1995=100)a 261.6 266.9 276.0 285.3 270.9 273.4 271.4 265.1 270.8 302.7 388.7b

% change, year on year 37.5 20.9 10.4 12.8 3.6 2.4 –1.7 –7.1 0.0 10.7 43.2

a Rebased from 1990=100. b Estimated from CSO figures.Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics.

Financial indicators

The kyat has remained under heavy pressure, sinking to around Kt720:US$1 byend-2001 on the free-market. (By comparison, the relatively little-used officialrate averaged around Kt6.8:US$1 in 2001). Partial failure of Myanmar’s mainhydropower plant has left many companies reliant on costly imported diesel,putting severe pressures on Myanmar’s over-stretched foreign-exchange reserves(see Foreign trade and payments). The sinking currency sparked rumours thatlower-value notes were to be removed from circulation, as in 1987, when manypeople lost their savings. The SPDC has repeatedly denied such rumours, butthe nervous population has little faith in the kyat. Many people have continuedto invest in dollars, gold or large consumer durables such as cars, seen as saferstores of value.

Confidence also remains weak in Myanmar’s third currency unit, the foreignexchange certificate (FEC), introduced in 1993 at parity with the dollar andwidely used by Myanmar businesses. Rumours that outstanding FECs werealmost double the level of foreign-exchange reserves in 2001 prompted fearsthat the FEC could also be withdrawn from use without full compensation. TheSPDC has repeatedly denied that it is planning such a move, but the FEC

There is heavy pressure onthe kyat

Myanmar (Burma) 23

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

exchange rate nevertheless followed the free-market kyat downwards in 2001,ending the year at around Kt690:US$1.

In recent years the SPDC had some modest success in controlling its hugebudget deficit through expenditure compression. However, surging moneysupply growth in 2000 and in the first half of 2001 suggests that the SPDC mayonce again have resorted to printing money. Broad money (M2) rose sharply by47.4% year on year in the first quarter of 2001, accelerating to growth of 49.1%year on year in the second quarter.

Money supply and credit(Kt m unless otherwise indicated; end-period)

1999 2000 20013 Qtr 4 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr 3 Qtr 4 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr

Money (M1) 329,272 345,765 382,573 403,926 434,956 464,968 559,625 608,035 % change, year on year 21.3 22.6 24.4 31.6 32.1 34.5 46.3 50.5

Quasi-money 206,297 216,459 235,911 259,159 308,218 335,574 351,890 380,534

Broad money (M2) 535,569 562,224 618,484 663,085 743,174 800,542 911,515 988,569 % change, year on year 29.4 29.7 31.4 37.1 38.8 42.4 47.4 49.1

Total credit 550,996 585,994 634,891 684,976 757,820 819,364 918,709 1,022,920 Claims on central government 335,964 343,385 432,366 445,987 465,266 483,240 611,468 645,892 Claims on local government n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Claims on non-financial public enterprises 42,537 53,960 3,513 22,977 48,238 69,158 3,373 33,930 Claims on private sector 172,495 188,649 199,012 216,012 244,316 266,966 303,867 343,098

Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics.

Sectoral trends

In a speech in September 2001 the home affairs minister, Colonel Tin Hlaing,spoke of the shortage of fertiliser and commented that rice yields, acreage andoutput were likely to dip in 2001 (October 2001, page 23). Fertiliser importsdropped by 47.2% year on year in April-October (the first seven months of2001/02). Flooding in June is likely to have disrupted harvesting for the sum-mer rice crop, while falling rice prices may have encouraged some farmers toswitch to more lucrative crops. Despite these problems, rice exports jumped by325.9% year on year in volume terms in April-October. However, the increasewas compared with a very low base period. In addition, rice exports may becoming from the high stocks that remain after two years of good harvests.

On January 11th the fisheries ministry announced that new concessions wouldbe granted to Thai fishermen, but only in the form of joint ventures. Investorswould also have to pay fees of Bt500,000 (US$11,364) per month for eachtrawler. Thai fishing concessions were cancelled in 1999 after the storming ofthe Myanmar embassy in Bangkok by pro-democracy protestors. The newagreement is expected to boost fish export earnings through the second half of2001/02. (Exports of prawns fell by 5.7% year on year in volume terms in April-October, while exports of fish and fish products dropped by 7.1% year on year.)

Money supply surges

Rice outlook is patchy

New fishing concessionsgranted

24 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

For many years tight state control over production and exports limited foreigninvestment in the mining sector. However, in recent years a few large-scaleprojects have got off the ground, including the Monywa copper mine, inSagaing Division, run by Ivanhoe Mines of Canada in a 50:50 joint venturewith the SPDC’s Myanmar Number 1 Mining Enterprise. Phase one of theproject is now complete, with copper output estimated at 28,000-35,000tonnes/year (t/y). Phase two involves development of the massive Letpadaungcopper field, field, with reserves of 1bn tonnes of ore with a 0.4% coppercontent. Originally scheduled for completion in 2003, in late December it wasreported that Letpadaung would not come on stream until 2004. When fullyoperational, the Monywa project is expected to produce some 125,000 t/y ofcopper, making it one of the largest copper mines in Asia.

In late December Ivanhoe Mines announced plans for a further joint venture,this time to develop the Modi Taung gold deposit near Mandalay. The depositwas discovered in late 2000. Subsequent testing by Ivanhoe revealed that 97%of the gold could be recovered by conventional mining techniques, althoughthe full size of the deposit is not yet known.

Total tourist arrivals slumped by 70.9% year on year in April-October (the firstseven months of 2001/02). Tourist arrivals were falling sharply even before thedrop in international travel following the September 11th attacks on the US.Efforts to turn the tourist industry into a major source of foreign exchange havefailed. Arrivals have been held down by factors including poor infrastructure,shortages of low-cost accommodation for independent travellers, concerns overthe risk of political instability and a worldwide boycott campaign organised bythe pro-democracy movement.

Tourist arrivalsApr-Oct Apr-Oct

1997/98 1998/99 1999/2000 2000/01 2000/01 2001/02

Arrivals 265,122 287,394 246,007 208,676 138,940 40,465

% change, year on year 5.4 8.4 –14.4 –15.2 3.6 –70.9

Source: Central Statistical Organisation, Selected Monthly Economic Indicators.

Late start for Letpadaung

Ivanhoe to invest in gold

Tourist arrivals collapse

Myanmar (Burma) 25

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Foreign trade and payments

Despite weak demand from key Asian markets such as Thailand, Myanmar’sexports leapt 84.8% year on year in the first seven months of 2001/02, toKt9.6bn (US$1.4bn at the over-valued official rate or US$15.5m at the free-market rate). Imports also rose strongly, despite the restrictions imposed by theSPDC in 1998 on imports of many consumer and other items. The rise inimports had been expected. Power shortages, the result of the failure of the keyLawpita hydropower plant, have resulted in heavy imports of costly diesel topower the country’s generators.

Trade data are subject to frequent, large revisions and are distorted bywidespread smuggling, money laundering and the use of three exchange rates.

Merchandise trade balance(Kt m)

Apr-Oct Apr-Oct1999 2000 % change 2000/01 2001/02 %change

Exports 7,073.5 10,569.3 49.4 5,170.3 9,561.1 84.8

Imports cif 14,463.9 15,426.3 6.7 8,182.3 12,074.5 47.6

Balance –7,390.4 –4,857.0 –34.3 –3,012 –2,513.4 –16.6

Sources: IMF, International Financial Statistics; Central Statistical Organisation, Selected Monthly Indicators.

Export growth in April-October was boosted by a 368.4% year on year increasein gas export earnings to Kt 2.6bn, now that massive Yadana offshore gasproject is fully on stream. Gas exports overtook exports of pulses to becomeMyanmar’s single largest source of export revenue in April-October. Exports ofteak and hardwoods also continued to rise strongly in value terms, althoughthese figures may be inflated by smuggling (illegally logged Thai timber isreportedly sent across the border to Myanmar before being re-imported).

Exports of main commodities(volume in ‘000 tonnes; value in Kt m; fiscal years)

1999/2000 2000-01 % change Apr-Oct 2000 Apr-Oct 2001 % change Volume Value Volume Value Volume Value Volume Value Volume Value Volume Value

Pulses 650.7 1,179.3 753.1 1,485.3 15.7 25.9 371.8 783.8 654.0 1,224.3 75.9 56.2

Prawns 14.2 530.0 15.2 598.1 7.0 12.8 8.7 368.8 8.2 299.9 –5.7 –18.7

Rice 54.9 64.9 241.8 214.7 340.4 230.8 102.8 105.2 437.8 338.6 325.9 221.9

Fish & fish products 31.4 231.9 49.2 291.9 56.7 25.9 24.0 145.7 22.3 148.3 –7.1 1.8

Rubber 29.2 75.2 20 65.9 –31.5 –12.4 11.1 36.3 12.5 40.6 12.6 11.8

Teak 234.0 726.7 212.8 968.8 –9.1 33.3 127.8 580.2 120.3 847.4 –5.9 46.1

Hardwood 335.3 198.2 278.5 260.4 –16.9 31.4 187.5 157.6 176.4 276.0 –5.9 75.1

Metals & ores 33.5 288.5 34.8 302.3 3.9 4.8 17.9 168.3 17.8 171.4 –0.6 1.8

Maize 88.8 54.4 142.7 88.9 60.7 63.4 29.0 18.8 20.9 13.6 –27.9 –27.7

Gas – 31.2 – 1,110.5 – 3,459.3 – 588.5 – 2,756.5 – 368.4

Othersa – 5,368.8 6254.7 – 16.5 – 2,767.4 – 3,320.7 – 20.0

a Mainly border trade.Source: Central Statistical Organisation, Selected Monthly Economic Indicators.

The trade deficit narrows

Gas exports surge

26 Myanmar (Burma)

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Rice exports soared by 325.9% year on year in April-October, albeit from a verylow base. Two successive good harvests have left the SPDC with higher thanusual rice stocks, boosting exports. However, continued restrictions on Thaifishing concessions may be behind the very weak exports of fish and prawns inApril-October, both of which fell in volume terms.

After falling year on year in 2000/01, imports jumped by 47.6% year on year inkyat terms during April-October, the first seven months of 2001/02. The leapwas driven by surging oil imports, up 1,965.1% year on year in April-October,to Kt1.4bn. This reflects continued domestic power shortages rather than anupturn in domestic energy use. The 47.2% drop in fertiliser imports is badnews for the key agricultural sector, which relies heavily on imported inputs.Imports of consumer goods also fell, down 25.2% year on year during April-October. No official explanation was given for the drop in imports of consumergoods, but it is possible that there has been tighter implementation of importcontrols. Government-sector imports drove the overall increase in April-October, leaping 395.6% year on year. Imports by the private sector, on otherhand, dropped by 2.2% year on year in value terms. This suggests that importlicenses and scarce foreign exchange have been allocated to state-ownedenterprises at the expense of the private sector, while private-sector domesticinvestment may also be sagging.

Imports of main commodities(Kt m; fiscal years)

Apr-Oct Apr-Oct1999/2000 2000/01 % change 2000/01 2001/02 % change

Crude oil 554.6 95.7 –82.7 68.1 1,406.3 1,965.1

Machinery & transport equipment 3,289.4 2,631.3 –20.0 1,295.6 2,717.3 109.7

Base metals & manufactures 1,722.8 1,437.7 –16.5 765.7 831.8 8.6

Electrical machinery 1,578.3 1,122.5 –28.9 620.3 797.2 28.5

Edible oils 477.6 475.3 –0.5 291.6 340.6 16.8

Cement 252.9 187.1 –26.0 92.6 126.8 36.9

Paper & paper board 343.7 344.3 0.2 180.7 277.5 53.6

Pharmaceuticals 302.2 413 36.7 232.8 223.1 –4.2

Rubber manufactured goods 205.0 242.8 18.4 152.1 145.3 –4.5

Fertiliser 329.0 254.4 –22.7 193.4 102.2 –47.2

Unspecified itemsa 6,480.6 7,022.0 8.4 3,974.7 4,634.1 16.6

Total incl others 16,264.8 14,899.7 –8.4 8,182.3 12,074.5 47.6 Government 4,823.3 3,009.5 –37.6 1,023.2 5,071.4 395.6 Private 11,441.5 11,890.2 3.9 7,159.1 7,003.1 –2.2

a Mainly border trade.Source: Central Statistical Organisation, Selected Monthly Economic Indicators.

Imports are rising again

Myanmar (Burma) 27

EIU Country Report February 2002 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2002

Imports by category(Kt m; fiscal years)

Apr-Oct Apr-Oct Apr-Oct2000/01 2001/02 % change 2000/01 2001/02 % change

Capital goods 5,335.1 4,060.6 –23.9 2,014.3 3,922.4 94.7

Intermediate goods 5,132.0 4,579.8 –10.8 2,274.1 5,237.7 130.3

Consumer goods 5,797.7 6,259.3 8.0 3,893.9 2,914.4 –25.2

Source: Central Statistical Organisation, Selected Monthly Economic Indicators.

According to the latest data from the IMF’s International Financial Statistics,reserves reached US$256.2m (including gold) by end-June 2001. Despite themodest narrowing of the merchandise trade deficit in the first seven months of2001-02, boosted by earnings from gas exports, foreign exchange remainsextremely scarce. The SPDC has had little access to international aid and loansfor more than a decade, while in recent years foreign investment approvalshave also slumped. The international community will continue to wait forsigns of political reform before resuming large-scale aid and lending, leavingMyanmar on the brink of a balance-of-payments crisis.

International liquidity(US$ m, end period)

1999 2000 20011 Qtr 2 Qtr 3 Qtr 4 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr 3 Qtr 4 Qtr 1 Qtr 2 Qtr

Foreign exchange 328.6 341.0 305.0 265.3 279.2 262.0 273.3 222.8 200.8 246.0

SDRs & IMF reserve position 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 0.3 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.1

Gold (national valuation) 11.0 10.8 11.2 11.1 10.9 10.8 10.5 10.6 10.2 10.1

Total international reserves 339.7 351.9 316.5 276.6 290.4 272.9 284.0 233.5 211.1 256.2Source: IMF, International Financial Statistics.

In recent years Myanmar has attracted only a small amount of internationalhumanitarian and development aid. Aid inflows are set to rise in 2001/02,albeit modestly, as Japan disburses funds for a number of small infrastructureprojects, including a planned US$5.1m rural water-supply project and US$6.5road and electrification project, both in Shan State. However, as of mid-Januarythere had still been no decision from Japan on aid earmarked for the repair ofthe Lawpita hydroelectric power plant, which supplies the bulk of the country’selectricity. The Japanese government has come under pressure from somecampaign groups and other members of the international community to waitfor concrete signs of political reform before disbursing funds.

Reserves remain criticallylow

Some development aidresumes