MRG 18899:MRG 18899 - BBC Newsnews.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/20_03_07_minority.pdf ·...

Transcript of MRG 18899:MRG 18899 - BBC Newsnews.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/20_03_07_minority.pdf ·...

In 1948, the United Nations General Assembly

adopted the Universal Declaration of Human

Rights, which proclaimed that ‘all human beings are

born free and equal in dignity and rights’. Sadly, for

many minorities and indigenous peoples around the

world, this inspirational text – with its emphasis on

equality and non-discrimination – remains a dream,

not a reality.

Ethnic or sectarian tensions are evident in many parts

of our globe. In places, they have boiled over into

bitter violence. The Middle East situation continues

to deteriorate – with some minority communities

fearing for their very survival. In Africa, the crisis in

Darfur is deepening, as government-sponsored militia

continue to carry out massive human rights abuses

against traditional farming communities. In Europe,

the spotlight has fallen on Muslim minorities – with

rows flaring over the Danish cartoons and the

wearing of the veil and burqa.

ISBN 1 904584 59 4

Now more than ever, world leaders must insist that

the rights of minorities and indigenous peoples be

respected. The participation of minorities is essential

if conflict is to be prevented and lasting peace to be

built. This second annual edition of the State of theWorld’s Minorities looks at the key developments

over 2006 affecting the human rights and security of

ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities and

indigenous peoples. It includes:

p a preface by the UN’s Independent Expert on

Minority Issues

p a unique statistical analysis of Peoples under

Threat 2007

p a special focus on the participation of minorities,

with analysis from leading academics on electoral

representation and the European system

p an eye-witness report from Sri Lanka, on the

impact on minorities of the resurgence of conflict

p comprehensive, regional sections, outlining the main

areas of concern as well as any notable progress.

The State of the World’s Minorities is an invaluable

reference for policy-makers, academics, journalists and

everyone who is interested in the conditions facing

minorities and indigenous peoples around the world.

State oftheWorld’sMinorities2007

minority rights group international

State oftheWorld’sMinorities2007Events of 2006

minority rights group international

Stateof theWorld’s M

inorities 2007Events of 2006

Minority

Rights

Group

International

MRG_18899_FC 2/3/07 11:08 Page 1

MRG_18899_FC 2/3/07 11:08 Page 2

State oftheWorld’sMinorities2007

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 1

AcknowledgementsMinority Rights Group International (MRG)gratefully acknowledges the support of allorganizations and individuals who gave financial andother assistance for this publication including theSigrid Rausing Trust and the European Commission.Commissioning Editor: Richard Green

Minority Rights Group InternationalMinority Rights Group International (MRG) is anon-governmental organization (NGO) working tosecure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguisticminorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, andto promote cooperation and understanding betweencommunities. Our activities are focused oninternational advocacy, training, publishing andoutreach. We are guided by the needs expressed byour worldwide partner network of organizationswhich represent minority and indigenous peoples.

MRG works with over 150 organizations innearly 50 countries. Our governing Council, whichmeets twice a year, has members from 10 differentcountries. MRG has consultative status with theUnited Nations Economic and Social Council(ECOSOC), and observer status with the AfricanCommission on Human and People’s Rights. MRGis registered as a charity and a company limited byguarantee under English law. Registered charity no.282305, limited company no. 1544957.

© Minority Rights Group International, March2007. All rights reserved.

Material from this publication may be reproducedfor teaching or for other non-commercial purposes.No part of it may be reproduced in any form forcommercial purposes without the prior expresspermission of the copyright holders.

For further information please contact MRG. ACIP catalogue record of this publication is availablefrom the British Library.

ISBN 1 904584 59 4Published March 2007Design by Texture +44 (0)20 7739 7123Printed in the UK

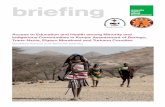

Cover photoA Tamil child living with her family in the damagedremains of Jaffna railway station, Sri Lanka, having beendisplaced by the civil war. Howard Davies/Exile Images

Inside cover photo

Dalit children collect wood in Uttar Pradesh, India.Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

Minority Rights Group International54 Commercial Street, London, E1 6LT, UnitedKingdom. Tel +44 (0)20 7422 4200, Fax +44 (0)207422 4201, Email [email protected] www.minorityrights.org

Getting involvedMRG relies on the generous support of institutionsand individuals to further our work. All donationsreceived contribute directly to our projects withminorities and indigenous peoples.

One valuable way to support us is to subscribe toour report series. Subscribers receive regular MRGreports and our annual review. We also have over 100titles which can be purchased from our publicationscatalogue. In addition, MRG publications areavailable to minority and indigenous peoples’organizations through our library scheme.

MRG’s unique publications provide well-researched,accurate and impartial information on minority andindigenous peoples’ rights worldwide. We offer criticalanalysis and new perspectives on international issues.Our specialist training materials include essentialguides for NGOs and others on international humanrights instruments, and on accessing internationalbodies. Many MRG publications have been translatedinto several languages.

If you would like to know more about MRG,how to support us and how to work with us, pleasevisit our website www.minorityrights.org, or contactour London office.

Select MRG publications:p Assimilation, Exodus, Eradication: Iraq’s minority

communities since 2003p Preventing Genocide and Mass Killing:

The Challenge for the United Nationsp Minority Rights in Kosovo under International Rulep Electoral Systems and the Protection and

Participation of Minorities

This document has been produced withthe financial assistance of the EuropeanUnion. The contents of this document

are the sole responsibility of Minority Rights GroupInternational and can under no circumstances be regard-ed as reflecting the position of the European Union.

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 2

State oftheWorld’sMinorities2007Events of 2006With a preface by Gay J McDougall,UN Independent Expert on Minority Issues

Minority Rights Group International

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 3

PrefaceGay J McDougall,UN Independent Expert on Minority Issues

Peoples underThreatMark Lattimer

NewsSri Lanka Flash PointFarah Mihlar

PublicParticipationby MinoritiesMinority Members of National LegislaturesAndrew ReynoldsMinority Protection in EuropeKristin Henrard

AfricaEric Witte

AmericasMaurice Bryn

6

9

18

25

25

32

4460

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 4

Asia and PacificJoshua Castellino and Emma Eastwood

EuropeHugh Poulton

Middle EastEric Witte

ReferencePeoples under Threat 2007Minority Members in National LegislaturesExplaining Minority RepresentationStatus of Ratification of Major International andRegional Instruments Relevant to Minority andIndigenous Rights

AppendicesUN Declaration on the Rights of Persons belongingto National or Ethnic, Religiousand Linguistic MinoritiesWhat are Minorities?ContributorsSelect Bibliography

7489

103116

118124128130

142143

145145147

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 5

PrefaceGay J McDougall,UN Independent Expert onMinority Issues

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 6

It is increasingly clear that ethnicity and religion areamong the most potent mobilizing forces insocieties. This is exacerbated in societies in whichethnicity and religion mark the fault lines betweenthe haves and the have-nots, the powerful and thepowerless, those who have hope and those whodespair. In the past few months, this has beengraphically illustrated by the turbulence in theMiddle East – but, as this annual review byMinority Rights Group International shows, thesetensions are commonplace around the world.However, it is important to emphasize that ethnic orreligious diversity alone is neither a precondition fornor a determinant of violent conflict. The existenceof minority groups in what may be perceived to bean otherwise homogeneous society is not aninherent cause of conflict.

While acknowledging the reality of ethnic orreligious dimensions in many conflicts, the morefundamental causes of these conflicts generally liebelow the surface, buried, often intentionally, by thosewith an interest in fomenting conflict. In somesituations, the purveyors of war are actually seekingpower and profits by immoral or illegal means, andthey often find easy cover in deflecting blame ontothose who are most powerless and most different.Also, in times of hardship, racism is often employed todivert attention from the root causes of despair. Andtargeting an easily identifiable group for exclusion orexploitation allows some to feel comfort in amythology that dehumanizes certain people based onhow they look or what they believe, the language theyspeak or where their ancestors called home.

Wars with ethno-religious components are deeplycomplex and must be better understood if we are tostand a chance of preventing, in this century, thebloodshed that marked the last. We must dispel themyth that diversity is, in itself, a cause of tensionand conflict.

In contrast, we must promote the understandingthat diverse societies can be among the healthiest,the most stable and prosperous. Respect forminority rights is crucial to this understanding.Minority rights are based on the principle of anintegrated society, where each can use their ownlanguage, enjoy their culture and practise theirreligion while still embracing a broader, inclusivenational identity.

The opportunity to participate fully andeffectively in all aspects of society, while preserving

group identity, is essential to true equality and mayrequire positive steps on the part of governments.Minority rights are not about giving somecommunities more than others. Rather, they areabout recognizing that, owing to their minoritystatus and distinct identity, some groups aredisadvantaged and are at times targeted, and thatthese communities need special protection andempowerment.

Equality for all does not always come naturally oreasily when political power and influence over theinstitutions of state lie predominantly in the handsof certain groups, which, perhaps due to theirmajority status, have a political advantage. Historyhas shown us, time and again, the immense damagecaused to nations, peoples and regions by those whouse the power at their disposal for the benefit ofonly some, while excluding or actively oppressingothers as a means to maintain, entrench or extendtheir power.

For such societies, the exclusion, discriminationand resentment that are fostered by such powerimbalance, create the conditions under which faultlines may occur along ethnic or religious grounds. Itis perhaps here, in the fundamental flaws ordysfunctioning of governmental power, that theseeds of tensions and grievances are sown that latermay emerge into conflicts. Such conflicts aremisunderstood as being purely ethnic or religiousconflicts, based upon difference and the perceivedinability of different groups to live peacefullytogether. In fact they are often more correctlyconflicts of greed and inequality than they areconflicts of diversity.

Today, in almost every corner of our world itseems that that there is a growing suspicion of‘otherness’ or difference, whether it be ethnic,religious or based on other grounds. This climate offear is also open to abuse by those who might seekto exploit divisions between different religiousfaiths, or those who might justify oppression in thename of security.

In this worrying climate, the principles enshrinedin the UN Declaration on the Rights of National orEthnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities are asrelevant today as ever, and as needed for healthy,diverse societies. In adopting this Declaration in1992, states have pledged to protect the existence –and identity – of minorities within their territory, toestablish conditions of equality and non-

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

Preface 7

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 7

discrimination, and to ensure effective participationof minorities in public life. The Declaration is abenchmark – codifying the minimum treatmentthat those belonging to minority communitiesshould expect from their governments. It is centralto my mandate to promote implementation of thisvital Declaration, and I pursue my work in theknowledge that, in doing so, I am also promotingconflict prevention; urging that injustices andinequities be identified at an early stage so thatlasting solutions may be found.

Gay J McDougall

Preface State of the World’sMinorities 2007

8

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 8

Peoples underThreatMark Lattimer

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 9

It is something of a paradox that, in the period fromthe aftermath of the Cold War to the early years ofthe ‘war on terror’, the world became, by mostobjective criteria, much safer. Certainly, the numberof conflicts fought around the world has steadilyfallen and, the great Congolese war apart, the totalnumber of people who have died in them hasdecreased too. Each research institute compiles itsfigures somewhat differently, but most conflictexperts recorded 20 or fewer major armed conflictsin 2006, compared to a high of over 30 in 1991.Of course, whether a community feels safe is asmuch a judgement about the future as an evaluationof the present. The recent use in Western states ofemergency powers and other mechanisms curtailingcivil liberties is a response to armed attacks in theUSA, Spain and the UK which are in many respectsunprecedented, although very rare. But the great tollof death from political violence continues in thecountries of the South, in Africa, Asia and theMiddle East, and today’s wars have this in commonwith the ethno-nationalist conflicts that succeededthe fall of the Soviet Union: the violence isoverwhelmingly targeted by ethnicity or religion.Wars as a whole may be less common, but in three-quarters of the major armed conflicts around theworld in 2006, particular ethnic or religious groupswere the principal target. In 2007, minorities havemore cause than most to feel unsafe.

New threats in 2007Minority Rights Group International (MRG) hasused recent advances in political science to identifywhich of the world’s peoples are currently undermost threat. As explained in the last edition of Stateof the World’s Minorities, academic researchers haveidentified the main antecedents to episodes ofgenocide or mass political killing over the last halfcentury (see State of the World’s Minorities 2006).Approximating those main antecedents by usingcurrent data from authoritative sources, includingthe World Bank, the Organization for EconomicCooperation and Development (OECD) andleading conflict prevention institutes, enables theconstruction of the Peoples Under Threat 2007table (see p.11 for short version and Table 1,pp.118–22 in the Reference section for the fullversion). The indicators used comprise measures ofprevailing armed conflict; a country’s priorexperience of genocide or mass killing; indicators of

group division; democracy and good governanceindicators; and a measure of country credit risk as aproxy for openness to international trade.

The position of Somalia at the top of the table for2006 attests to a highly dangerous combination offactors. In June 2006 the Union of Islamic Courts(UIC), an Islamic coalition seeking to restore lawand order to Somalia, took over Mogadishu andsubsequently much of the country, curbing thepower of Somalia’s warlords. However, in December,Ethiopian armed forces acting in support of theTransitional Federal Government (TFG), andsupported by the USA, overthrew the UIC, whichhad received support from Eritrea and a number ofMiddle Eastern states. The TFG is unlikely to beable to retain control of the country without outsidesupport. While one side has portrayed itself asfighting terrorists linked to al-Qaeda, and the otherclaims it is fighting Christian invaders, the mostimmediate fear is now a renewal of atrocities againstcivilians in the context of Darood–Hawiye inter-clan rivalry and a threat to minorities both inSomalia and in neighbouring Ethiopia. Althoughthe UIC emphasized the importance of movingaway from clan politics and had achieved somesuccess in overcoming ‘clanism’, it was nonethelessparticularly associated with the Hawiye clan. It alsoprovided overt support for Oromo and Ogaden self-determination movements in Ethiopia. There is nowa grave threat of violent repression against thesepopulations, as well as other groups in Somalia inthe context of a power vacuum and/or continuedintervention by neighbouring states.

The situation in Iraq continues to deteriorate.Figures released by the United Nations (UN) basedon body counts in Iraq’s hospitals and morguesshowed over 3,000 violent civilian deaths a monthfor most of the latter half of 2006. These weremainly comprised of killings by death squads, oftenlinked to the Iraqi government itself; attacks bySunni insurgent groups; and deaths in the contextof military operations conducted by theMultinational Force in Iraq. The UN HighCommissioner for Refugees estimates that between40,000 and 50,000 Iraqis flee their homes everymonth. What is less well publicized is the particularplight of Iraq’s smaller communities, the 10 per centof the population who are not Shia Arab, SunniArab or Sunni Kurd. These minorities, whichinclude Turkomans, Chaldo-Assyrians, Armenians,

Peoples under Threat State of the World’sMinorities 2007

10

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 10

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

Peoples under Threat 11

Rank Country Group Total

1 Somalia Darood, Hawiye, Issaq and other clans; 21.95Bantu and other groups

2 Iraq Shia, Sunnis, Kurds, Turkomans, Christians; 21.61smaller minorities

2 Sudan Fur, Zaghawa, Massalit and others in Darfur; 21.50Dinka, Nuer and others in the South; Nuba, Beja

4 Afghanistan Hazara, Pashtun, Tajiks, Uzbeks 21.03

5 Burma/ Myanmar Kachin, Karenni, Karen, Mons, Rohingyas, 20.40Shan, Chin (Zomis), Wa

6 Dem. Rep. of Hema and Lendu, Hunde, Hutu, Luba, Lunda, 19.88the Congo Tutsi/Banyamulenge, Twa/Mbuti

7 Nigeria Ibo, Ijaw, Ogoni, Yoruba, Hausa (Muslims) 19.22and Christians in the North

8 Pakistan Ahmadiyya, Baluchis, Hindus, Mohhajirs, 18.97Pashtun, Sindhis

9 Angola Bakongo, Cabindans, Ovimbundu 16.68

10 Russian Federation Chechens, Ingush, Lezgins, indigenous 16.29northern peoples, Roma

11 Burundi Hutu, Tutsi, Twa 16.20

12 Uganda Acholi, Karamojong 16.18

13 Ethiopia Anuak, Afars, Oromo, Somalis 16.11

14 Sri Lanka Tamils, Muslims 16.00

15 Haiti Political/social targets 15.72

16 Côte d’Ivoire Northern Mande (Dioula), Senoufo, Bete, 15.62newly settled groups

17 Rwanda Hutu, Tutsi, Twa 15.31

18 Nepal Political/social targets, Dalits 15.07

19 Philippines Indigenous peoples, Moros (Muslims) 15.06

20 Iran Arabs, Azeris, Baha’is, Baluchis, Kurds, Turkomans 15.02

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 11

Mandean-Sabeans, Faili Kurds, Shabaks, Yezidis andBaha’is, as well as a significant community ofPalestinians, made up a large proportion of therefugees fleeing to neighbouring Jordan and Syria in2006. In addition to the generalized insecurity theyface, common to all people in Iraq, minorities sufferfrom specific attacks and threats due to their ethnicor religious status, and cannot benefit from thecommunity-based protection often available to thelarger groups.

With Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan taking threeout of the top four places in the table, and Pakistanrising eight places to be ranked eighth, thecorrelation between peoples under threat and thefront lines in the US-led ‘war on terror’ is evenstarker than it was in 2005–6. The debate aboutwhether US foreign policy on terrorism is makingAmericans safer or not continues to rage in the US,but it is now surely beyond doubt that it has madelife a lot less safe for peoples in the countries wherethe ‘war on terror’ is principally being fought.

The most significant risers in the table in additionto Pakistan are listed below. Perhaps the moststartling case is that of Sri Lanka, where peace talksfailed and the conflict between the government andthe Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam re-erupted,causing over a thousand civilian deaths and thedisplacement of hundreds of thousands in 2006 (seethe report by Farah Mihlar). Civilians in Tamil areasare at particular risk, as is the country’s Muslimpopulation, which is caught between the two sidesbut was excluded from the peace negotiations.

Another long-running self-determination conflictthat experienced a resurgence in 2006 was inTurkey, where a Kurdish splinter group carried outbomb attacks in major cities. It remains to be seenwhether the ongoing negotiations over Turkey’saccession to the European Union will temper theambitions of some parts of the Turkish governmentand military to increase repression of the Kurds. Infact, Kurds throughout the region face heightenedthreats in 2007, with both Turkey and Iran massingtroops on their respective borders with Iraq,claiming that Iraqi Kurdistan is being used as a baseby armed Kurdish groups from which to launchattacks on their territory.

Iran’s position in the top 20 does not relate solelyto the threat against Iranian Kurds but also to thecountry’s other minorities (including Ahwazi Arabs,Baluchis and Azeris), who in total constitute nearly

40 per cent of the population. Successive Iraniangovernments have been hostile to demands forgreater cultural freedom for ethnic minoritycommunities, and the US-led intervention in Iraqand the international stand-off over Iran’s nuclearprogramme have left the government deeply wary ofany perceived foreign involvement with minoritygroups. President Ahmadinejad has blamed Britishforces for being involved in ‘terrorist’ activities inKhuzistan, a mainly Arab province borderingsouthern Iraq.

The military coup in Thailand in September 2006was effected without significant bloodshed, althoughThailand’s status as a popular Western touristdestination ensured it received widespread mediacoverage. Less well known is the fact that the coupfollowed an escalation in the conflict in the south ofthe country between the government and separatistgroups, placing the mainly Muslim population in thesouthern border provinces at increased risk.

That both Lebanon and Israel and the OccupiedTerritories/Palestinian Authority have risen in thisyear’s table comes as no surprise following the warbetween Israel and Hezbollah in 2006 and anescalation of Israeli military operations in theOccupied Territories. (Israel did not appear in lastyear’s table due to the absence of data on some ofthe indicators.) Israel’s bombardment of Lebanonfell particularly heavily on the Shi’a population, butthe war has destabilized the country as a whole,placing all communities at the greatest risk since theearly 1990s of a return to civil war. In Gaza, anIsraeli offensive followed the kidnapping of anIsraeli soldier in June, with a total of over 600Palestinians killed in 2006 as a whole. Throughoutthe Occupied Territories/Palestinian Authority, thepopulation faces an increased threat, not just fromIsraeli military operations but also from civil conflictbetween rival Palestinian factions.

Three states have fallen out of the top 20 in 2006:Indonesia, where a peace agreement signed in 2005in Aceh has so far held, and Liberia and Algeria,both of which continue to recover following the civilwars that tore those countries apart in the 1990s.

Finally, it should be noted that although thenumber of African states in the top 20 has fallenslightly since 2005–6, Africa continues to accountfor half of the countries at the top of the table,making it still the world’s most dangerous regionfor minorities.

Peoples under Threat State of the World’sMinorities 2007

12

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 12

Participation as preventionThe identification of communities at grave riskaround the world prompts the immediate question:what can be done to improve their situation?International action is considered later in thischapter; here, we concentrate on one factor at thenational level which, perhaps more than any other,has the potential to address minority grievances andto prevent the development of violent conflict. Thepublic participation of minorities, their activeengagement in the political and social life of a state,underpins all other efforts to protect the rights ofminorities and acts as a safety valve when major sitesof disagreement between communities threaten toturn violent.

Within the state, public participation can takemany forms, including, most importantly,representation in parliament (this is considered inmore detail in Andrew Reynolds’ chapter below)and in the executive branch of government, andparticipation in the judiciary, civil service, armedforces and police. More generally, it extends totaking part in the economic and social life of a state,

such that minorities feel they have a real stake in thesociety in which they live, that it is their society asmuch as that of anyone else. In areas whereminority communities are geographicallyconcentrated, it may also include a measure ofautonomy or self-government.

In an important speech he made on a visit toIndonesia, the former UN Secretary-General KofiAnnan also made this point when he wascommenting on the extreme case of separatism.

‘Minorities have to be convinced that the state reallybelongs to them, as well as to the majority, and thatboth will be the losers if it breaks up. Conflict is almostcertain to result if the state’s response to separatismcauses widespread suffering in the region or among theethnic group concerned. The effect then is to make morepeople feel that the state is not their state, and soprovide separatism with new recruits.’

Even within one state, very different responses toclaims for regional autonomy can develop. In India,for example, the positive approach shown to

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

Peoples under Threat 13

Rank Rise in rank Country Group Totalsince 2006

8 8 Pakistan Ahmadiyya, Baluchis, Hindus, Mohhajirs, 18.97Pashtun, Sindhis

14 47 Sri Lanka Tamils, Muslims 16.00

15 13 Haiti Political/social targets 15.72

20 5 Iran Arabs, Azeris, Baha’is, Baluchis, Kurds, Turkomans 15.02

33 12 Yemen Political/social targets 12.63

35 7 Lebanon Druze, Maronite Christians, Palestinians, 12.25Shia, Sunnis

39 15 Turkey Kurds, Roma 12.02

40 7 Guinea Fulani, Malinke 11.83

53 New entry Thailand Chinese, Malay-Muslims, Northern Hill Tribes 10.96

54 New entry Israel/OT/PA Palestinians in Gaza/West Bank, Israeli Palestinians 10.83

Major risers since 2006

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 13

managing decentralized governance in Tamil Naducan be contrasted with the state’s hostility towardsautonomy claims in Punjab, Kashmir and Nagaland.In the Russian Federation, the accommodation ofautonomy in a region such as Tatarstan can similarlybe contrasted with the gross human rights violationsthat continue to be committed in Chechnya in thename of combating separatism. Each situation is ofcourse different, but it is notable that, in the case ofIndonesia itself, perhaps the most significant faller inthis year’s Peoples under Threat table, the nationalparliament in July 2006 adopted a framework for

autonomy that will enable the first direct localelections to be held in the region of Aceh, the sceneof nearly three decades of separatist conflict. Since apact was signed in August 2005, the Free AcehMovement has reportedly dissolved its armed wingand the Indonesian government has withdrawntroops from Aceh.

But, in many states, it is public participation atthe national level that constitutes the key issue forminority protection and conflict prevention. Here itis worth making a distinction between the formalmechanisms of participation, such as elections, andhaving a genuine say in how a country is run (theformer being a necessary but not sufficientcondition for the latter). That Iraq has been pushedfrom the top of the list in this year’s table is due to a

Peoples under Threat State of the World’sMinorities 2007

14

Below: Internally displaced man in Bartallah,Mosul, Iraq. Three of his family were assassinated.Mark Lattimer/MRG

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:37 Page 14

slightly less negative showing under the cited WorldBank governance indicators, particularly for ‘Voiceand Accountability’, a measure of the extent towhich citizens of a country are able to participate inthe selection of governments, including anassessment of the political process and human rights(note that the indicators were published inSeptember with a nine-month lag). Yet the fact thatIraqi citizens were able to participate in electionsand that the main communities are all representedin government has not prevented the polity frombeing fatally fractured. The same could be said ofBosnia and Herzegovina, which remains stubbornlyalongside Serbia in the upper part of the table,despite over a decade having passed since the power-sharing deal established under the Dayton PeaceAgreement. It is clear that the internationalcommunity still has a lot to learn about theapplication of public participation in practice.

For public participation to help reduce the threatof violent conflict it needs to be more than simplyan entry ticket to a shouting match. It needs toconstitute participation in governance, and that inturn depends on a basic level of governmentaleffectiveness and rule of law. However, in both Iraqand Bosnia the mechanisms for communityrepresentation introduced under internationalcontrol have themselves exacerbated or entrenchedthe division of the state on ethnic or sectarian lines,and induced a level of state failure. Following theoccupation of Iraq in 2003, the coalition authoritiesestablished an Iraqi Governing Council in whichmembership was strictly apportioned along ethnicand sectarian lines. Political patronage ensured thatwhole ministries became dominated by officialsfrom the minister’s own sect or group, and sectarianpolitics quickly became the defining feature of thenew Iraqi state. This mistake was compounded atthe first Iraqi elections in January 2005, when theelectoral system based on a national list combinedwith a boycott in Sunni Arab governorateseffectively ensured that Sunni Arabs were largelyexcluded from political representation during a keyyear in the country’s attempted transition todemocracy. In other states with a long history ofethnic conflict, such as South Africa or Nigeria,constitutional and electoral mechanisms have beenestablished which aim to promote inclusive politicalsystems, with representation across ethnic orreligious communities.

The subject of political participation andcommunity representation in very divided societiesmerits further study, given its fundamentalimportance to peace-building and stability, and thefocus on participation in this edition of the State ofthe World’s Minorities is intended as a contribution.But just a brief review of country situationsillustrates the obvious danger of constitutional orelectoral systems which make ethnicity or religion aprincipal mobilizing factor in politics, leading to thecreation of a majority or dominant group which isdefined by ethnicity or sect.

This should be contrasted with the growing rangeof examples, some quoted above, of where effectiveparticipation of minorities has helped to resolve orprevent conflict, through the promotion of moreinclusive political systems, whether at national orregional level. In addition to power-sharingagreements, a wide range of mechanisms are availableto promote such participation appropriate to thegiven situation, including rules or incentives forpolitical parties to appeal across communities, theadoption of electoral systems that favour rather thanmarginalize minorities, systems of reserved seats,special representation, formal consultative bodies,formal or informal quotas in public administration,and positive action programmes, as well asarrangements for greater self-government in regionswhere minorities are geographically concentrated.

Given the very high correlation around theworld between minority status and poverty, itshould also become a priority for internationaldevelopment agencies to promote the participationof minorities in their programmes, particularly atnational and local level. It is now widely acceptedthat anti-poverty initiatives are unlikely to achievelong-term success unless the poor are closelyconsulted and involved in their formulation anddelivery, yet minorities are typically excluded fromthe planning of development programmes, oftenthrough the same societal discrimination that is theroot cause of their impoverishment in the firstplace. This is one reason why developmentprogrammes, while often bringing importantbenefits to a society, rarely succeed in targetingeffectively the poorest communities.

The international responseAfter the hopes raised by the UN World Summit inSeptember 2005, the international response in 2006

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

Peoples under Threat 15

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 15

to the situation of peoples under threat can only bedescribed as disappointing.

The headline case during 2006 continued to bethe mass, ongoing crimes under international lawcommitted against the population of the Darfurregion of Sudan, which the Sudanese government ismanifestly failing to protect. The World Summitresolved that, in such cases, the UN SecurityCouncil should be ‘prepared to take collectiveaction’ in a manner that is ‘timely and decisive’. Inthe event, the reaction of the Security Council wasseen to be belated and divided. The strategy of theSudanese government has been to emphasize itscooperation with the existing African Union (AU)mission in Darfur – while on the ground effectivelycontrolling the AU forces’ access to much of theregion – and to oppose the deployment of anystronger UN force, relying on divisions in theSecurity Council and in particular the support ofChina, a major trading partner and heavy investorin the Sudanese oil industry. In August 2006, theSecurity Council did finally approve a 20,000-strongUN force, but Sudan continues to withhold consentfor its deployment. Meanwhile, the situation inDarfur has deteriorated and continuing attacks bySudanese armed forces and Janjaweed militia oncivilian targets threaten to push the death toll farbeyond the 200,000 that have already perished.

A measure of what international peacekeepingforces can achieve was demonstrated during 2006 inneighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo,where the UN’s largest peacekeeping force oversawthe successful conclusion of the country’s first freeelections for 45 years, a major milestone on the roadto peace. However, despite a new readiness on thepart of the UN peacekeepers to react robustly tothreats from militia groups, armed conflictcontinued in the east in both Ituri and Kivu (leavingthe position of the Congo unchanged, near the topof the Peoples under Threat table).

In the programme of UN reform initiated at theWorld Summit in 2005, the most importantdevelopment for human rights was the replacementof the discredited Commission on Human Rightswith a new Human Rights Council. The vision wasfor a smaller body that would meet more often,combining improved expertise and objectivity withgreater clout within the UN system. By the end of2006, however, uncertainty still prevailed over themodus operandi of the Council’s two main tools: the

new system of Universal Periodic Review, by whichstates’ human rights records would be assessed bytheir peers, and the Council’s special rapporteursand working groups, with the future of the countryrapporteurs called into question. More worryinglystill, the Council quickly attracted accusations ofpolitical bias, and even criticism from the UNSecretary-General, after it held two special sessionsdevoted to the situation in Gaza and one to theIsrael–Hezbollah conflict, but failed to lookcritically at other major cases of human rightsviolations around the world. It finally held a specialsession on Darfur in December, but passed a weakresolution, authorizing a high-level mission to assessthe human rights situation but failing to recognizethe culpability of the Sudanese government for theabuses committed in Darfur. This was despite thefact that indisputable links between the governmentand the militias responsible for much of the killinghad been reported almost two years earlier by theInternational Commission of Inquiry on Darfurestablished by the UN Security Council.

Two recently established UN mechanisms have,however, played an important role in protectingminorities. The Independent Expert on MinorityIssues has consistently highlighted minorityprotection issues worldwide, including issuingcommunications on the situation of Haitians in theDominican Republic and on minority women inBurma (Myanmar). The Special Adviser to the UNSecretary-General on the Prevention of Genocidehas undertaken two missions to Darfur, one to Côted’Ivoire and one to the Thai–Burmese border toinvestigate events in Burma’s Karen state followingan intensification of Burmese military operationsfrom November 2005 onwards. The Special Advisermakes recommendations concerning civilianprotection, establishing accountability for violations,the provision of humanitarian relief and steps tosettle the underlying causes of conflict.

The outgoing Secretary-General, Kofi Annan,established in May an Advisory Committee on thePrevention of Genocide to provide guidance to theSpecial Adviser and to contribute to the UN’sbroader efforts to prevent genocide. The committee’sreport, which has not been published, is believed torecommend strengthening the role of the SpecialAdviser by ensuring he report directly to theSecretary-General, improve his access to the SecurityCouncil and increase resources to the office, as well

Peoples under Threat State of the World’sMinorities 2007

16

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 16

as calling for improved cooperation within andoutside the UN system to obtain informationspecifically focused on early warning of genocideand other crimes against humanity. Therecommendations have been sent to the incomingSecretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, and his responsewill be an early test of the new Secretary-General’scommitment to improving civilian protection frommass atrocities.

The principal normative development during 2006was the finalization of the Declaration on the Rightsof Indigenous Peoples, which had occupied the UNCommission on Human Rights for over a decade. Atits first meeting in June, the Human Rights Councilapproved a text of the Declaration that recognizedindigenous peoples’ rights to live in freedom, peaceand security; not to be subjected to forcedassimilation, destruction of their culture or forcedpopulation transfer; and recognized their rights toself-determination and self-government in mattersrelating to their internal and local affairs, and topractise their languages and cultural traditions.

However, in November the third committee ofthe UN General Assembly passed a proceduralmotion blocking approval of the Declaration, atleast until later in 2007. The motion was putforward by Namibia on behalf of the African groupon the committee and promoted by statesincluding Canada, the USA, Australia and NewZealand, which had claimed during the debate thatthe Declaration may negatively affect the interestsof other sectors of society. Although theDeclaration’s force would essentially have beenhortatory and not legally binding, the motion wasinterpreted as an attempt to weaken the documentor to ditch it altogether.

The failure to approve the Declaration isillustrative of a widespread refusal by states torecognize the special, and often very dangerous,position in which indigenous peoples and minoritiesmore generally find themselves, and their urgentneed for better international protection. Evenaffluent states that are free of internal armed conflictand whose territorial integrity remains unchallenged– whatever other security threats they face –frequently ignore the extent of discrimination facedby minorities and often indulge in a tendency toblame any community dispute or integrationproblem on the minority community itself. As theUN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide

wrote in the State of the World’s Minorities 2006,‘Governments in both the South and the Northpersist in labelling some people a threat simplybecause they are members of a minority.’ Yet anyassessment of prevailing conflicts and human rightsviolations around the world indicates that it isminorities themselves who are at greatest risk, usuallyat the hands of their own governments. Without thepolitical courage to admit that reality, and to respondappropriately, the world is unlikely to become a saferplace for minorities any time soon. p

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

Peoples under Threat 17

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 17

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 18

19

Sri LankaFlash PointFarah Mihlar

The coastal route to Galle is a picturesque one. Inthe 115 km trip south from the Sri Lankan capital,Colombo, the view of the sparkling, blue IndianOcean is almost uninterrupted. Fishermen returnwith their day’s catch; bustling, roadside markets linethe verges; girls in crisp white uniforms, with black,plaited hair scurry off to school. Unsurprisingly, theresorts in and around the southern port town aresome of the country’s top tourist destinations,drawing visitors from around the world.

The scenes are relaxed, even idyllic. But on BoxingDay 2004, Galle was one of the towns that wasravaged by the tsunami that ripped through most ofSri Lanka’s coastline, reducing entire villages to rubbleand killing some 40,000 people. Sri Lankans like me,who saw the waves crash in, and lived through thoseterrible days, have them etched in our memories. Thepanic, the horror, the grief of the bereaved were alsoplayed and replayed on television stations across theworld. Though less in the international limelight,many families remained displaced in camps as we setout to drive to Galle to report on the plight of thetsunami victims, two years after the disaster.

But, on approaching the town, Sri Lanka’srecurring nightmare of the past 20 years was aboutto engulf us. Not a natural disaster, but a man-madeone. A catastrophe that has ripped apart this pear-shaped island in the Indian Ocean and blighted thelives of successive generations of Sri Lankans.

The first sign is the panic. A mass frenzy ofpeople, mobbing vehicles, blocking our wayforward. A bamboo pole is hoisted across the road asa flimsy barrier. Young men surround us, bangingwindows telling us to go back. The driver nervouslylowers the shutters.

Left: A soldier stands guard near the site of thesuicide bomb attack in Colombo, Sri Lanka, inDecember 2006.

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 19

Sri LankaFlash Point

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

20

‘The Tigers are attacking Galle. There is firingall over. You’ll be killed,’ someone shouts throughthe window.

In the mêlée, we can barely comprehend thenews. Everyone knew that Sri Lanka’s stutteringpeace process between the government and theLiberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) was aboutto collapse. But, even in the worst of times duringthe two-decade war, the southern coast was rarelyattacked. Galle, like most southern towns, remainedlargely unscathed through all the big battles, whichwere confined to the country’s north and east.

We draw into the side of the road, and waitnervously in the blazing sun. We turn on the radio.It tells of an audacious assault by the Tamil Tigerson the Galle port and adjoining naval base. Tworebel boats, carrying suicide bombers had launchedan attack – prompting the navy to retaliate. Reportson the radio keep referring to the battle, just a fewhundred metres away from where we are parked.Two people are reported killed.

We turn back and attempt another route. Wemake it to the nearby village of Katugoda, wheredozens of children were orphaned, women widowedand livelihoods lost, when the tsunami struck. Butnow, to add to their misfortune, the war has arrivedpractically in their backyard.

‘We heard four loud bangs, and went runningout,’ says Fauzun Nizam, a social worker who hadbeen meeting with tsunami widows, when theTigers’ attack happened. ‘Our hearts werepounding. I did not know what was happening. Ithought “Oh God! Why?” First the tsunami andthen this,’ she adds.

The attack sent jitters across Sri Lanka. It broughthome the painful reality that, after four years ofrelative peace, the war had returned. The ceasefireagreement signed between the government of SriLanka and Tamil Tigers in 2002 was in tatters. Atthe time, the deal was hailed by the internationalcommunity and embraced by the war-weary people.For the first time in decades, Sri Lankans from thesouth were able to travel to the north and east. Foodand clothes started to flow to the war-torn areas,banks and businesses opened new branches.Property began to boom, mainly propelled byexpatriate Sri Lankans most of whom had fled thecountry as refugees.

But the euphoria didn’t last long. Distrust betweenthe government and Tamil Tigers, extremist stances

by both parties and the rebels’ lack of commitment toa negotiated settlement to the conflict, saw the peaceprocess slowly crumble. The situation was furthercomplicated by a historic split within the Tamil Tigersmovement, which the Tigers’ leadership felt was beingexploited by the government.

Muslim minorities under attackThe impact of the resurgent conflict is being feltall over Sri Lanka. Almost half-way between Galleand Colombo lies the town of Aluthgama. School-teacher Mehroonniza Careem and her family fledhere after heavy fighting erupted in the war-tornnorth-eastern town of Muttur in July 2006. TheMuttur battle is considered by many to be themoment that sealed the end of the ceasefire. MrsCareem is the principal of a well-known Muslimgirls’ school in the area. She is a dignified, strong-minded woman, but even she shudders as sherecalls how the town came under attack by theTigers and the government launched a fiercecounter-offensive.

‘First we heard huge blasts through the night,none of us could sleep, we were terrified, we couldhear the explosions just near our house.’

Mrs Careem sought refuge in her school only tofind that thousands of others had done the same.

‘We were like matchsticks in a matchbox, eachperson stuck against the other, heads touching legs,’she says.

But the civilians sheltering in the school were notspared. Mrs Careem says the Sri Lankan armyattacked the buildings, claiming that the rebels hadinfiltrated the complex. ‘People fled, hoping to getto another town,’ she says. ‘We later heard some ofthem were killed by the Tigers.’

Mrs Careem did not just lose her home in theupsurge of violence – her beloved second son hasgone too. Just days before the Muttur attack, hedisappeared – allegedly kidnapped by the rebels –his whereabouts now unknown. When we meet, it isRamadan, a holy month for Muslims. Mrs Careemis putting her faith in God, for the return of her 24-year-old son, Ramy. She cannot speak of her child,without breaking down. ‘My son is mentally unwell.He has to take medication every day, otherwise hebecomes very sick. I am pleading with them torelease him.’

The toll exacted by Sri Lanka’s decades’ long civilwar has been immense. It has cost more than

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 20

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

Sri LankaFlash Point

21

60,000 lives and displaced hundreds of thousands ofcivilians. There have been multiple human rightsviolations, rapes, and thousands of people have‘disappeared’. The causes of the conflict are complex– but the war pits the Tamil Tigers against theSinhalese-dominated government of Sri Lanka.

The Sinhalese Buddhists, who make up 70 percent of Sri Lanka’s population, control the statemachinery – the military as well as the government.The Tamils – the majority of whom are Hindus –are ethnically distinct and speak their own language.The rebel movement, the Tamil Tigers, want tocarve out a separate state for minority Tamils in thenorth and east of the country.

Minority suffering ignoredBut trapped in the middle, often ignored in thereporting of the Sri Lankan conflict, are the otherminority communities. After Tamils, Muslims are thesecond largest minority in Sri Lanka – numberingnearly a million. They have suffered tremendously inthe conflict but they are often the ‘forgottenminority’ and their plight is rarely acknowledged.

Sri Lankan Muslims are scattered across thecountry, but a majority live in the coastal areas.Their presence is a throwback mainly to the Arab-Indian traders who married local women and settledin the island many centuries after the Sinhalese andTamils. Their dominance in eastern Sri Lanka – insome small towns they form the majority – andtheir insistence on their separate and unique identityhas brought them into conflict with the TamilTigers, who see the Muslim presence as a hindranceto their homeland claim.

One of the most horrific episodes occurred inOctober 1990, when the Tigers engaged in acampaign to ‘ethnically cleanse’ areas theycontrolled. Nearly 100,000 Muslims were given 24hours to leave. Most fled, taking nothing with them,forced into flimsy boats in the monsoon deluge.Crowded and panicked, some families lost theirinfant babies, who fell into the sea. The purgeripped apart Tamil and Muslim communities, whohad previously lived peacefully side by side.

‘I remember how we left, our Tamil neighbourscrying, helpless, seeing us leave,’ says JuwairiyaUvais, who was a young girl at the time. ‘Hundredsand hundreds of people were all walking fromdifferent villages towards the beach.’

Juwairiya, her family and many others escaped to

the north-western town of Puttalam – the closestpoint that offered relative safety.

Yet, 16 years on, families still live in what wereintended to be temporary camps. Juwairiya – whonow works for a local charity – showed me aroundsome of them. It was a stormy day, and we struggledto enter homes through flooding muddy pathways.Half built with bricks, topped with thatched roofs,the families call these dwellings their homes. Butnot a single individual I spoke to could produce alegal document to claim ownership of the land.

In the backyards, little children in tattered clotheschased chickens, while water dripped through thedry coconut-palm leaf roofs. Poverty is entrenched.Many Muslims driven from their homes in 1990were left penniless. Well-to-do businessmen werereduced to working as labourers at onion farms.During Ramadan, Juwairiya helps to coordinatelarge sums of money traditionally given as charity inthis month by wealthy Muslims in Colombo. ‘Therewas a time we used to give charity, now for the lastso many years we are recipients,’ she says.

The renewed conflict has also added to theuncertainty surrounding people’s lives. In Puttalam,as elsewhere in the country, more militarycheckpoints have sprung up as the authorities seekto crack down on the rebels’ activities. When we arestopped at one of them, Juwairiya struggles toexplain who she is to the Sinhala-speaking soldiers.There are a few tense moments. Juwairiya is notcarrying the proper identity papers and, as shecomes from the north-east, she speaks Tamil. In thecurrent jittery climate, these two factors might be

80 km0

SRI LANKA

Puttalam

Colombo

Jaffna

Galle

Trincomalee

Batticaloa

Aluthgama

Mannar

Muttur

INDIA

SRI LANKA

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 21

Sri LankaFlash Point

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

22

enough to get her arrested. Luckily, she is wearing aheadscarf and, after a few moments discussion, thesoldiers accept that she is Muslim, working with thedisplaced community, and wave her on.

It is not just Muslims who find themselvesstruggling to build new lives for themselves inPuttalam. Sinhalese Christians were also pushed outby the Tigers during the purge of the north-east.The Christians are Sri Lanka’s smallest religiousminority, found in both the ethnic Tamil andSinhalese communities, and who mostly convertedduring the 400-year colonial occupation of theisland by the Portuguese, Dutch and British.

Many of the displaced Christians in Puttalam livein one camp, close to the sea. The men eke out aliving as fishermen, but, poor as they are, theirfutures are now even more precarious. The Galleattack was just one illustration of the rebels’ capacityto launch sea-borne attacks. With the resumption ofthe war, the authorities have imposed harshrestrictions on sea travel. For fishermen, this meansthat they cannot set sail early in the morning.

‘They tell us we can only go after 5:30 in themorning. There are no fish to catch at that time.We have to start much earlier,’ says fishermanHerbert Jones.

Even if the rules were relaxed, Mr Jones believesthat the fishermen living in the displaced people’scamp, would still come off worse. ‘The sea issupposed to belong to everyone but we don’t belongto the village so we don’t get to fish.’

Four hours’ drive to the south, in the capitalColombo, at first glance, it seems as if it is adifferent world. Despite the renewed war, the citycentre – as always – displays an amazing sense ofresilience, ticking on despite the gloom. Hotels hostparties most nights, restaurants are bursting withcustomers and the city bustles with an almostsurreal sense of normalcy.

Behind the façade, however, you see a city undersiege. Armed soldiers are everywhere, standing attemporary barricades with red Stop signs, flaggingdown vehicles to be checked for explosives. In2006, Colombo has had more than five targetedbomb blasts, mainly aimed at opponents of theTamil Tigers.

Traditionally, moderate Tamils have been singledout by the Tigers, who have a reputation for nottolerating political opposition from among theirown ethnic community. In August 2005, Foreign

Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar, an ethnic Tamil,was shot dead by a sniper at his home. In August2006, Kethesh Loganathan, also a Tamil and deputyhead of the government’s peace secretariat, was shotdead. No one was ever brought to justice for thosemurders – but they were widely assumed to havebeen carried out by the Tamil Tigers.

Tamils targetted by militaryDuring the conflict, Tamil moderates have foundthemselves doubly victimized. Vulnerable to rebelreprisals, they are also attacked by governmentforces, who believe them to be rebels or supportiveof the Tamil Tigers. Under the terrorism laws, theill-treatment of Tamils, subjected to illegal detentionand torture, is well-documented. Moreover, Tamilsin lower-class groups face routine harassment –something that has become more pronounced overthe past few months.

The story of Janaki Sinnaswami, who is 59, is alltoo common. A Tamil who makes a living as adomestic worker in the wealthy houses of Colombo,she and her family have borne the brunt of SriLanka’s bitter ethnic conflict. Her first home wasdestroyed in the infamous 1983 riots, when Sinhalamobs, with political backing, went on a rampagedestroying Tamil houses, shops and businesses in allthe main cities, and attacking Tamil families, killing,raping and injuring.

It was the first time an entire minority communitywas targeted and attacked in such a brutal andwidespread manner, and is widely seen as theprecursor to all-out war between the Tamil Tigers andthe government. For Janaki, the loss of her home wasa setback from which the family never recovered. Herfamily moved back to the crowded parental home inthe slums, where seven adults and six children werecooped up in one room. Her husband – unable tocope – became an alcoholic and died. With no moneyto educate her oldest son, he grew up illiterate.Incredibly, against all the odds, Janaki scraped togetherthe money from her work as a maid and succeeded ineducating her two youngest children.

But now, with the collapse of the peace process,things have again taken a turn for the worse. Inthe slums, the military are again raiding thehouses of Tamils.

‘They bang on our doors at midnight hours.Army men come with guns and they check ourentire house, open everything, ask us who we are

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 22

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

Sri LankaFlash Point

23

harbouring,’ Janaki says. ‘I have told my mistress Ican’t work late, I have to go home because I have ayoung daughter and they can do anything to herwhen I am not at home.’

But if the situation for Tamils in Colombo isbad, in the war-torn north, it is much worse. In2006, the renewed fighting claimed 3,000 lives –the majority of them in the north and east. Overthe years, these areas have been shattered by theconflict. They are heavily mined in places, withlittle paths wending across a dry, barren landscape;families have been forced to flee their homes time

and time again. In the recent fighting, the situationhas bordered on catastrophic, with the northeffectively cut off from the rest of the country – themain roads have been blocked. At least one UNconvoy carrying humanitarian supplies into thenorth-east had to turn back because of heavyfighting, with officials warning that the situation insome places was ‘desperate’.

‘In some areas people are moving to starvation,but what is food compared to human dignity?’ saysRevd Dr Rayappu Joseph, the Bishop of Mannar, inthe north-west. The bishop is a well-known – butcontroversial – human rights activist. He is oftenattacked in the nationalist press for his alleged linksto the Tamil Tigers, an accusation he staunchlydenies. Shuttling between government and Tamil-

Below: A woman who fled from the town of Mutturprepares to make morning tea near a tent at the AlAysha refugee camp in Kantale in August 2006.

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 23

Sri LankaFlash Point

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

24

controlled areas the bishop has first-handinformation on the plight of the people. He tellsstories of young men being shot down or kidnappedunder suspicion of being involved with the Tigers.He claims the killings often occur close to militaryor police checkpoints. Other human rights activistsin the area, who refused to be identified, fearing fortheir lives, corroborate the information.

In December 2006, the government gave thesecurity forces sweeping powers to search, arrest andquestion suspects. The fear is that these draconianmeasures could result in even more people beingarrested and held incommunicado. As the crisisdeepens, Bishop Joseph says, ‘We are helpless people.There is no one to help us, there is no one to save us.’

With the resurgence in the conflict, the ghosts ofthe past have returned to haunt Sri Lanka. Whitevans, the horrifying symbol attached todisappearances in the early 1980s, have come back.The vans appear at the doorstep of homes in broaddaylight, hauling in men and young boys aspetrified families look on.

The University Teachers for Human Rights(UTHR), one of Sri Lanka’s best-known humanrights groups, accused the Tamil Tigers in a reportpublished in June 2006. ‘Fathers are huddled intheir homes with their children fearing to go out,lest they are dragged into a van by thugs and are notseen again,’ the report says.

In previous reports, the UTHR pointed the fingerat the government, reporting on incidents where themilitary, in collusion with renegade Tamil groups,have been involved in abductions and killings.

Statistics are hard to come by, but in the monthof September alone, just in the northern town ofJaffna, Sri Lanka’s Human Rights Commissionreceived 41 complaints of abductions. The men whoare kidnapped rarely return; what happens to themremains a mystery. Although often presumed dead,years may pass without any official or rebelacknowledgement of the killing. Bodies may neverbe returned to grieving families.

The boys who are abducted are forced to take uparms. Since May 2006 UNICEF has received 135reports of children being abducted to fight for Tamilmilitants in the war. And there are accusations thatthe government is implicated in child kidnappingstoo. Although it denies involvement with thedissident Tamil armed groups, the credibility ofthose denials was dealt a blow in November 2006,

when the government’s position was contradicted bya senior UN official.

Following a visit to Sri Lanka, Allan Rock, aspecial adviser to the UN representative for childrenand armed conflict, said he ‘found strong andcredible evidence that certain elements of theGovernment security forces are supporting andsometimes participating in the abductions andforced recruitment of children’. His findings were anembarrassment to the government, which hadalways claimed to hold the moral high ground overthe Tamil Tigers by accusing them of using childsoldiers. It was this fact, combined with otherhuman rights violations, that resulted in a ban onthe Tamil Tigers and their political and fundraisingactivities in most Western states.

For many Sri Lankans, the collapse of the peaceprocess and resurgence of violence has marked aterrifying new chapter in Sri Lanka’s conflict-riddenhistory. One of the biggest fears is that it is nowimpossible to say who is responsible for the killingsand abductions. Is it the government, is itparamilitary groups, is it the Tamil Tigers, or is itrenegade factions? In 2006, several Tamil journalists,academics and peace activists with differentaffiliations have randomly been gunned down in asinister string of killings that point to numerousperpetrators. Even more worrying, no one has beentried or found guilty for these crimes.

‘Today the alarm is sounding for Sri Lanka. It ison the brink of a crisis of major proportions,’ saidPhillip Alston, the UN Special Rapporteur on extra-judicial killings, to the UN General Assembly inOctober 2006. But many Sri Lankans feel that suchappeals are falling on deaf ears – that the world isnot interested in their plight. With no vast oilreserves, or strategic importance to world powers,Sri Lankans feel they are being left to face a bleakfuture by themselves. As Lalith Chandana, aChristian fisherman living in the Puttalam camp,puts it, ‘Every day we hear about peace but … wehave no hope peace will come.’

Colombo, November 2006

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 24

Public Participationby MinoritiesMinority Membersof the NationalLegislaturesAndrew Reynolds

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 25

When the first democratic National Assemblyconvened in Cape Town, South Africa, in 1994 itwas the living embodiment of Archbishop DesmondTutu’s dream of a ‘rainbow nation’: an Assemblythat was not merely elected by all but included all.Black sat with white on the government’s benches,coloured MPs joined with Afrikaners in opposition.But, beyond that, the Assembly of 1994 containedNdebele, Pedi, Tswana, Sotho, Venda, Xhosa andZulu, along with Indian South Africans, Anglo-whites, Afrikaans-speaking Cape coloureds andAfrikaans speakers of Dutch or French Huguenotdescent. The descendants of Mohandas Gandhi,Henrik Verwoerd and Govan Mbeki sat together,side by side.

South Africa’s ethos of political inclusion haswaned a little over the past 12 years, but the over-representation of minority groups still remains thenorm. While the inclusion of minorities is lessvisible in most other parts of the world, there is nota nation-state, rich or poor, democratic or not,where minority groups do not press for their voicesto be heard at the highest levels of decision-making.Most countries seek to create at least a small spacefor minorities in their national parliaments: thereare Christians and Samaritans in the PalestinianAuthority, Maoris in the New Zealand house,nomadic Kuchi in the Afghan Wolesi Jirga,German-speaking MPs in Poland, and Romamembers of the Romania parliament. Whether theserepresentatives are enough, have influence ongovernment policy, or are even representative of theminority groups they come from, are crucialquestions, but when minority communities have norepresentatives in national legislatures we can bepretty sure that those minority groups are not beingheard in the policy dialogue, their rights are beingdisregarded and their importance in electoralcompetition is small.

In many respects, the question of promotingminority representation is akin to the attentionincreasingly being paid to ensuring the participationof women in politics. There are now more womenMPs around the world than ever before and an evergrowing number of countries that use specialmechanisms to increase their number of womenMPs. While the question of how best to promoteminority representation has received far lessattention, it is an evolving issue for bothinternational organizations and nation-states seeking

to build more stable and inclusive societies. Infragile and divided societies, ensuring that asignificant number of minority MPs are elected is anecessary, if not sufficient, condition of short-termconflict prevention and longer-term conflictmanagement. There is not a single case of peacefuldemocratization where the minority community wasexcluded from representation.

The full participation of minorities in politics doesnot necessarily mean veto power, nor does it implythat minority MPs are the only politicians capable ofprotecting and advancing the dignity and politicalinterests of marginalized groups. But a progressivedemocracy which values inclusion is characterized bya situation where members of minority groups canrun for office, have a fair chance of winning, andthen have a voice in national, regional and locallyelected government. Having representatives of one’sown group in parliament is not the end of politicalinvolvement, but it is the beginning.

Perhaps of most importance, the inclusion ofboth majorities and minorities within nationalparliaments can reduce group alienation andviolence in those divided societies where politics isoften viewed as a win-or-lose game. Many peacesettlements over the past 25 years have revolvedaround inclusive electoral systems or reserved seatsfor communal groups as part of broader power-sharing constructs. There is a debate about how bestto include minority MPs. Should systems bedesigned so that minorities can be elected through‘usual channels’ or are special affirmative actionmeasures needed, like quotas or specialappointments? Furthermore, is it better whenminority MPs represent ‘minority parties’ that arerooted in an ethnic community, or should they beintegrated into the ‘mainstream’ parties, which maybe ideologically driven or dominated by majoritycommunal groups. This analysis refrains fromdelving too deeply into that debate and focuses onthe first part of the question: exactly how many MPsin the parliaments of the world are from minoritycommunities and what explains their election?

Minority MPs: a league tableThe league table shown in Table 2, Referencesection (pp. 124–6) is the product of detailedresearch on the presence of minority MPs innational legislatures around the world. Suchcomparative data has not been published before and

Public Participationby Minorities

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

26

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 26

the 50 cases shown represent approximately aquarter of all countries; we have included bothdemocracies and non-democracies, rich and poorcountries, and legislatures from all continents.

Just under half, or 23 of the nation-states, over-represent their minorities when seat share iscompared to population share, while the remaining27 cases, on average, under-represent minoritygroups. The table details 115 distinct minority groupsin the 50 countries: 54 are over-represented in theirlegislatures while 59 are under-represented. A fewminority groups have MPs in legislatures in numberswell above what their population share would suggest.Most notable are Zanzibaris in Tanzania, whites inSouth Africa, Maronites in Lebanon, Croats inBosnia and Herzegovina, Walloons in Belgium,Sunnis in Iraq and Herero in Namibia. Sometimesminorities achieve significant representation becausetheir members vote in higher numbers than othergroups, but, more often, the ‘over-representation’ is aproduct of special mechanisms. In contrast, Russianspeakers in Latvia and Estonia, Serbs in Montenegro,Albanians in Macedonia, Bosniaks in Bosnia andHerzegovina, Arabs in Israel and Catalans in Spainare all significantly under-represented.

The top of the league table is something of asurprise. No single type of country consistentlyover-represents minority populations. The top 10most ‘inclusive’ legislatures in the world are foundin Africa, Europe, Oceania, North America and theMiddle East. Some are peaceful, wealthy, Westerndemocracies, while others are poor, democraticallyweak, and wrestling with ethnic divisions which stillturn violent. The strands that unite the countriesthat over-represent their minority communities arefour-fold: first, there are post-conflict democracieswhere minority inclusion was a core plank of thepower-sharing settlement which brought about anend to civil war and the beginnings of multi-partydemocracy – e.g. Bosnia and Herzegovina, Lebanonand South Africa. Second, there are nation-statesthat entrenched power-sharing democracy over acentury ago and, while the pressures for minorityinclusion may have ebbed over time, the norm ofinclusion has remained strong – e.g. Belgium andSwitzerland. Third, there are cases which do well onthe inclusion of minorities in their parliamentsbecause significant elements of society and partypolitics are sensitive to minority issues and valueminority candidates – e.g. Canada, Finland, the

Netherlands and New Zealand. Last, there arecountries where the very geographical concentrationof a minority group allows such groups to gainsignificant representation in their nationallegislatures – e.g. Kiribati, Sri Lanka and Tanzania.

Interestingly, the three top cases are all in sub-Saharan Africa: Namibia, South Africa andTanzania. Why should these new and sometimestroubled states produce parliaments that are soinclusive of their many minorities? The SouthAfrican parliament is the most ethnicallyrepresentative of any democratic legislature in theworld. For the reasons discussed below, thepromotion of multi-ethnic parties and the deliberate‘over-representation’ of minorities was thewatchword of the first decade of democracy inSouth Africa. The same has been true in Namibia,where the liberation movement, the South WestAfrica People’s Organization (SWAPO), while beingrooted in the Ovambo majority, sought to presentitself as a catch-all party, similar to the AfricanNational Congress (ANC) in South Africa or theCongress Party of India. In the current NamibianNational Assembly 10 distinct ethnic groups arerepresented and the majority Ovambo group(representing 60 per cent of the population) onlyhave 50 per cent of the seats. It is true that theCongress of Democrats, Democratic TurnhalleAlliance of Namibia, Monitor Action Group,National Unity Democratic Organisation,Republican Party and United Democratic Frontopposition parties have non-Ovambo (bar one)MPs, but SWAPO has two Baster, four Caprivian,two Damara, four Herero, six Kavango, five Nama,three white, a coloured and a San representative.Tanzania’s high spot in the table is a result of theover-representation of the island of Zanzibar in theirNational Assembly.

South Africa is an interesting case study of thepositive good of including minorities in governanceover and above their population size. Post-apartheidSouth Africa has consistently done well onindicators of minority representation as a result oftwo pressures towards accommodation. First, thepost-apartheid peace settlement of 1994 (andpermanent Constitution of 1996) rested upon auniversally accepted principle of multi-ethnicinclusion in the new politics of the nation. Aprinciple beyond that of mere equality, whichemphasized the very opposite of the former

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

Public Participationby Minorities

27

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 27

apartheid laws, that is, the new South Africangovernment would deliberately reach out tominorities to visibly demonstrate their full role ingovernance. Second, it quickly became apparentthat, to be successful, any Xhosa party had to reachout to non-Xhosa, a Zulu party would atrophy ifZulu nationalism remained its raison d’être, andwhite parties could only gain leverage if theybecame multi-ethnic vehicles. Thus, the ANCunder Nelson Mandela deliberately placedcoloureds, Indians, whites and Zulus high up on itslists of candidates in 1994 and 1999. This diversitygoes beyond the simple black–white divide. As a‘catch-all’ national movement, the ANC seeks toexist in a universe beyond the Xhosa communitywhich has historically dominated its leadership. Itstrives to attract the votes of Ndebele, Pedi, Sotho,Tswana, Venda, along with Zulu in KwaZulu,coloureds in the Cape, and English- and Afrikaans-speaking whites throughout the country. Theseappeals are often based on policy promises, but justas much on having senior ‘ethnic’ politicians highup on the party lists. The same has been true forthe opposition – the white-dominated DemocraticAlliance places non-white leaders in visiblepositions – and was even true for the now defunctNational Party, which, in its failure to attractsufficient non-white leaders and voters, wasultimately subsumed into the ANC in the mostremarkable power-shift between two long opposedmovements in the history of modern politics. While

the level of minority over-representation hasdeclined under Thabo Mbeki, it still exists in 2006.Nevertheless, consolidating democracy and stabilitywill rest upon continuing this ethos of minorityinclusion and respect.

At the executive level, South Africans have also feltthat it is important to visibly include minorities. AsTable 1 shows, white and Indian South Africans weredramatically ‘over-represented’ in the first decade ofdemocratic governance under Presidents NelsonMandela and Thabo Mbeki. The over-representationof whites and Indians was most pronounced in 1994and 1999, but when ministers and their deputies aretaken together it remains to this day.

The deliberate reaching out to smaller minoritygroups and institutions, designed to ensure thewidest inclusion possible, was particularly key in1994, when South Africa made its first tentativesteps towards a multi-party electoral democracy.Two very small parties gained representation in thefirst National Assembly (the Freedom Front andPan-Africanist Congress of Azania), facilitatingconflict resolution by democratic rather than violentmeans. Although the Afrikaner Freedom Front onlywon nine (or 2 per cent) of the seats, theimportance of their inclusion in democraticstructures was disproportionate to their numbers.General Constand Viljoen’s Freedom Frontrepresented a volatile Afrikaner constituency thatcould easily have fallen into the hands of whitesupremacist demagogues such as Eugene

Public Participationby Minorities

State of the World’sMinorities 2007

28

Black White Coloured Indian

1994 Ministers 52% 26% 7% 15%

Ministers and Deputies 51% 28% 5% 15%

1999 Ministers 76% 7% 3% 14%

Ministers and Deputies 76% 9% 2% 12%

2006 Ministers 81% 11% 4% 4%

Ministers and Deputies 68% 18% 4% 8%

Population 74% 14% 8% 2%

Table 1 Cabinet ministers in South Africa

MRG_18899:MRG_18899 2/3/07 10:38 Page 28

Terre’blanche had its representatives been shut outof the political process. As it was, Viljoen, as formerhead of the South African Army, became chair ofthe National Assembly’s Defence Select Committeeand the paramilitary Afrikaner resistance faded away.

Representing a very different place and time, theinclusion of minority politicians in Canada today isa second positive example of how majority politicscan provide a space to hear and reassure minoritycommunities. Electoral system specialists wouldexpect the First Past the Post system of elections inCanada to provide a high hurdle to the election ofnon-white, non-majority MPs, but Canadian partiesand voters have managed to circumvent themajoritarianism of their Anglo election system toproduce a parliament which includes, and over-represents, Asians, Canadians of African extractionand Francophone Canadians. Inuits are under-represented in the House of Commons but theyhave some access to self-governance through thesemi-autonomous province of Nunavut.