Monetary Review - Danmarks Nationalbanks hjemmeside · motif for the first coin in a series of 7-10...

Transcript of Monetary Review - Danmarks Nationalbanks hjemmeside · motif for the first coin in a series of 7-10...

2003

Da

nm

ark

s Na

tion

alb

an

kM

on

eta

ry R

ev

iew

03

Danmarks Nationalbank

Monetary Review 4th Quarter

Danmarks Nationalbank Havnegade 5 DK-1093 Copenhagen K

Telephone +45 33 63 63 63 Fax +45 33 63 71 25

www.nationalbanken.dk E-mail: [email protected]

D A N M A R K S

N A T I O N A L

B A N K 2 0 0 3

4

4

4-kvartal-2003-UK.pmd 19-11-2003, 08:281

12-12-2003 07:14 Antal sider: 1 Rev. nr. kolofon Oprettet af Alice Colombo

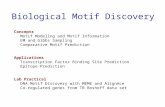

The small picture on the front cover is a section of the Århus City Hall Tower, chosen as the

motif for the first coin in a series of 7-10 thematic coins that are issued over a number of

years.

Text may be copied from this publication provided that Danmarks Nationalbank is specifi-

cally stated as the source. Changes to or misrepresentation of the content are not permit-

ted.

The Monetary Review is published by Danmarks Nationalbank and is issued quarterly.

Managing Editor: Jens Thomsen

Editor: Anders Møller Christensen

The Monetary Review can be ordered from:

Danmarks Nationalbank, Information Desk, Havnegade 5, DK-1093 Copenhagen K.

Telephone +45 33 63 70 00 (direct) or +45 33 63 63 63.

E-mail: [email protected]

www.nationalbanken.dk

Scanprint as, Viby J

ISSN 0011-6149

(Online) ISSN 1398-3865

12-12-2003 07:16 Antal sider: 2 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\indhold.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

Recent Economic and Monetary Trends.............................................. 1 SCP – Scandinavian Cash Pool .............................................................. 23

New Statistics Database at Danmarks Nationalbank's Website ........ 27 Volatility in Inflation and Economic Activity in the Nordic Countries............................................................................. 29

Anders Møller Christensen and Niels Lynggård Hansen, Economics

For some years, inflation and activity have fluctuated less in Denmark than in the

other Nordic countries. This is mainly attributed to the Danish fiscal-policy

framework aiming at reducing debt, as well as a consistent fixed-exchange-rate

policy. These policies have shielded Denmark from a number of so-called home-

made shocks.

Inflation Differentials in the Euro Area .............................................. 41

Borca Babic, Economics

The article outlines possible causes of the inflation differentials among the 12

euro area member states since the transition to the third stage of EMU in Janu-

ary 1999. Several factors, including real economic convergence and differences in

the member states' cyclical positions, have contributed.

The IMF and Danmarks Nationalbank's Balance Sheet...................... 53

Louise Mogensen, Financial Markets

Danmarks Nationalbank's balance sheet is affected by various financial accounts

with the International Monetary Fund, IMF. The risk in connection with these

transactions is kept at a very low level.

China's Role in the Global Economy.................................................... 61 Gitte Wallin Pedersen, International Relations

China's role in the world economy has grown significantly after 25 years with

sustained high growth rates. This development has focused international atten-

tion on China and the possible economic consequences to the rest of the world.

Contents

12-12-2003 07:16 Antal sider: 2 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\indhold.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

The Investment Services Directive – a New Basis for Securities Trading in Europe ................................................................................. 77

Birgitte Bundgaard and Anne Reinhold Pedersen, Financial Markets

Political agreement on a new Investment Services Directive may increase com-

petition in the markets once the directive enters into force. The much-needed

adaptation of legislation to the market development will facilitate the integra-

tion of the securities markets in the EU and benefit the business community and

private investors, even though several of the changes implemented by the direct-

ive are not substantial.

The Credit Channel in Monetary-Policy Analyses ............................... 85 Anders Mølgaard Pedersen, Economics

The credit channel is an aggregate term for a number of theories implying that

monetary policy also has an impact via a change in the supply of bank loans. This

article provides an overview of these theories and their practical relevance. In

Denmark the credit channel is presumably less significant than in most other

countries.

Press Releases ........................................................................................ 103

Tables and Graphs Section

Vol. XLII , No. 4

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

1

Recent Economic and Monetary Trends

This review covers the period from the beginning of September to the middle of November 2003

INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MARKETS

An international economic upturn has become more pronounced since the summer. The USA has seen increasing growth and Japan surprisingly positive growth since the turn of the year, and the growth estimates for 2003 and 2004 have been adjusted upwards. Improved confidence indi-cators and an increase in GDP in the 3rd quarter could mark the begin-ning of a recovery in the euro area.

The expectations in the financial markets of an improvement of the world economy are reflected in the steepening of the yield curve since the early summer. Long-term bond yields have risen since the low in June, cf. Chart 1. The increases were observed during the summer, while

10-YEAR GOVERNMENT BOND YIELDS Chart 1

Source: EcoWin.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Jan Mar May Jul Sep Nov Jan Mar May Jul Sep Nov

Per cent

Germany USA Japan2002 2003

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

2

in mid-November the yields were slightly lower than the level from the beginning of September. The 10-year government bond yield in both Germany and the USA was approximately 4.3 per cent in mid-November, while the corresponding Japanese bond yield was 1.3 per cent. The USA, Japan and the euro area have kept the monetary-policy interest rates unchanged since June, but there are increasing expectations of mone-tary-policy tightenings during 2004.

Stock prices were almost unchanged from September to mid-November. The slowdown followed a generally rising trend in the USA, Japan and the euro area from March to mid-September. Since March, the US S&P 500 index has increased by almost 25 per cent, the Nikkei index in Japan has risen by approximately 13 per cent and the DJ Stoxx 50 index for the euro area has risen by just over 20 per cent.

On the foreign-exchange markets the dollar continued it's weakening trend. From the beginning of 2002 to October 2003 the effective ex-change rate of the dollar weakened by almost 10 per cent, cf. Chart 2. The dollar's continued weakness recently may reflect uncertainty con-cerning the imbalances in the US economy, including the sustainability of the current-account deficit. The deficit was previously financed via private capital flows, but in recent years it has increasingly been fin-

US DOLLAR VIS-À-VIS OTHER CURRENCIES Chart 2

Note: Source:

Monthly observations. For the bilateral exchange rates an increase in the index indicates a strengthening of the dollar against the currency in question. An increase in the effective-dollar-rate index indicates a strengthening of the dollar against the weighted average of the currencies included in the index. The currencies shown are weighted as follows in the effective-exchange-rate index: euro 17 per cent, Canadian dollar 17 per cent, yen 12 per cent, Mexican peso 11 per cent and renminbi 9 per cent. EcoWin.

70

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

110

115

120

125

Jan Apr Jul Oct Jan Apr Jul Oct

Effective exchange rate Euro Canadian dollar Yen Mexican peso Renminbi

2002 2003

Index, January 2002 = 100

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

3

anced by Asian central banks, which have thus accumulated large dollar claims. At the meeting in Dubai in September, the G7 countries called for a more flexible, market-based development of exchange rates be-tween the major economies. The Bank of Japan temporarily reduced its otherwise massive interventions in the foreign-exchange market in order to prevent the yen from strengthening. In the period under review the euro, the Canadian dollar and the Japanese yen strengthened by 6-8 per cent vis-à-vis the dollar. The Mexican peso depreciated vis-à-vis the dol-lar, while the Chinese renminbi remained unchanged (China pursues a fixed-exchange-rate policy vis-à-vis the dollar).

In the period under review the prices for cyclically-sensitive industrial metals rose steadily in the light of improved growth prospects. In mid-November, these prices were just over 10 per cent higher than at the beginning of September.

The oil price ended the period where it started. At the beginning of the period, the oil price decreased after the release of higher-than-expected increases in global oil stocks. The decrease was followed by increases after OPEC's surprising decision to reduce production as from 1 November, and the price (Brent) briefly exceeded 30 dollars per barrel. In mid-November the oil price was just under 30 dollars per barrel.

At the time of going to press the gold price was the highest for 7 years, cf. Chart 3. This is presumably due to several factors, for instance that the gold-producing countries have raised the gold price after the

GOLD PRICE Chart 3

Note: Source:

Monthly observations. EcoWin.

250

275

300

325

350

375

400

USD per troy ounce

Gold

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

4

dollar's depreciation vis-à-vis their currencies, since gold is settled in dollars.

THE INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY

Growth in the euro area has been subdued since the turn of the year, while the USA and Japan have experienced increasing growth in the 2nd and 3rd quarters, cf. Chart 4. However, the sustainability of the recovery in the US economy is subject to some uncertainty. The uncertainty is particularly related to the USA's large current-account deficit and government-budget deficit. The US labour market is also a source of concern, since it has shown only weak signs of improvement despite the latest increase in output.

USA The US economy grew by 1.7 per cent quarter-on-quarter in the 3rd quarter. The growth rate has thus been on the increase since the turn of the year, cf. Chart 4. Private consumption accounted for the greatest part of the increase, including an increase by 6.1 per cent in consump-tion of durable consumer goods against the previous quarter. Growth in investments rose, hopefully pointing to a broadly-based upswing.

A major driving force for the increasing growth in 2003 has been the USA's strongly expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. The USA has

QUARTERLY GDP GROWTH IN 2003 Chart 4

Source: EcoWin.

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

Per cent, quarter-on-quarter

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q1 Q2 Q3

Euro area USA Japan

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

5

made more adjustments to its economic policy than any other country since the start of 2001, cf. Chart 5. The package of tax measures adopted in the spring entered into force in the 3rd quarter, implying e.g. general income-tax cuts and tax cuts for families with children. The monetary-policy interest rate has been reduced on an ongoing basis since 2001 to a historical low of 1 per cent. At the same time, long-term interest rates have been low. The level of interest rates has stimulated private con-sumption, and the 3rd quarter was no exception. This is indicated by the significant increase in households' purchases of durable consumer goods and the resilience of the housing market.

Employment has risen since August, and unemployment fell to 6 per cent in October. In a historical perspective, however, the labour market has developed weakly since the recovery began in late 20011, cf. Box 1. One explanation is lower output growth in this upswing than in previ-ous upswings and exceptionally strong productivity growth. Annual growth in hourly productivity was 4.7 per cent in the 3rd quarter.

The strongly expansionary fiscal policy has aggravated the imbalances. According to an IMF2 estimate, the government deficit is expected to be 6 per cent of GDP in 2003. This more than offsets the current-account deficit, which is estimated at 5.1 per cent of GDP. The private savings deficit has thus disappeared.

Weak employment growth and the imbalances cast doubt about the sustainability of the recovery when the stimuli from economic policy fade away. In addition, the increase in long-term interest rates since the early summer has dampened the stimulus to private consumption from conversion of housing loans.

1 The start of the recovery has been dated by the US research and analysis institute, National Bureau of

Economic Research, NBER. 2 IMF, World Economic Outlook, September 2003.

FISCAL POLICY AND MONETARY POLICY IN THE PERIOD 2001-03 Chart 5

Note: Source:

Fiscal policy is compiled as the structural budget balance as a percentage of GDP. A deterioration of the balance indicates expansion of fiscal policy. The 2003 figures are the IMF's estimates from September 2003. A further easing of Japan's monetary policy by an increase in the target for the banks' deposits with the Bank of Japan is not illustrated in the Chart. IMF, World Economic Outlook, September 2003.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

2001 2002 2003

Per cent

Euro area USA Japan UK

Monetary-policy interest rate

-8

-7

-6

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

Euro area USA Japan UK

2000 20032000 20032000 20032000 2003

Per cent of GDP Fiscal policy

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

6

A JOBLESS RECOVERY IN THE USA Box 1

In the US economy, employment has shown a weak trend in recent years. The eco-

nomic cycle bottomed out in November 2001, and since then employment has fallen

by just over 3/4 million people despite the GDP increase of 6 per cent. The cyclical

upturn since 2001 has therefore been called a jobless recovery. The employment

trend contrasts strongly with previous cyclical upturns where employment typically

showed a strong increasing trend, cf. the Chart (left-hand panel). However, the

current pattern has also been observed before. The previous recession in 1991 in

the USA was followed by a period of growth without job creation. Two consecutive

recoveries with atypical employment trends call for an analysis of the underlying

factors.

One reason why employment has shown a weaker trend in this recovery than on

previous occasions is that the GDP trend has also been weaker than normal despite

the increase, cf. the Chart (right-hand panel).

Ben S. Bernanke, one of the Federal Reserve Governors, recently emphasised

productivity growth as the most significant reason for the absence of job creation1:

Annual productivity growth has been 4.5 per cent on average since the trough of

the recession, i.e. stronger growth than in previous upswings. This reflects higher

productivity growth in general since the mid-1990s and probably also a delayed

effect of major investments in high-tech equipment which the business enterprises

are now learning to put to optimum use. However, other factors may also have con-

tributed to the weak employment pattern. Bernanke mentions four factors: 1) After

the boom years in the late 1990s many business enterprises had a labour surplus,

which entailed an untenable employment level when the recession set in in March

2001. 2) The business enterprises have been reluctant to hire and invest due to po-

litical and economic uncertainty. 3) The business enterprises may have utilised exist-

ing labour rather than hiring new employees in view of rising indirect payroll costs.

4) Structural changes in the US economy have led to permanent rather than tempo-

rary job losses to a higher degree than what is normal during a recession. This

applies to e.g. the manufacturing industry. Since it takes time to create new jobs in

other sectors and retraining may be involved, this may have contributed to the

weak development trend.

EMPLOYMENT AND GDP IN THE USA Chart

Note: Source:

The Charts show the trend in relation to the cyclical trough (the beginning of the expansion) which is 0. EcoWin, NBER and own calculations.

1 Speech at the Global Economic and Investment Outlook Conference, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on 6 November 2003.

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

-24 -21 -18 -15 -12 -9 -6 -3 0 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24Month from trough

Average of last 6 recessions Current

Trough = 100 Employment

92

94

96

98

100

102

104

106

108

110

-8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8Quarter from trough

Average of last 6 recessions Current

Trough = 100GDP

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

7

The Federal Open Market Committee, FOMC, has kept interest rates unchanged since the reduction at end-June by 0.25 per cent to 1 per cent. Inflation measured by the broad consumer-price index, CPI, was 2 per cent in October. Core inflation, i.e. CPI excluding food and energy, was 1.3 per cent in October and has been on the decrease for a long time. At the meeting at the end of October, the FOMC maintained its view that the probability, though minor, of an unwelcome fall in infla-tion exceeds that of a rise in inflation. The FOMC therefore found that the risk of inflation becoming undesirably low remains the predominant concern, so monetary-policy accommodation can be maintained for a considerable period.

Japan The national accounts show surprising growth in the Japanese economy, cf. Chart 4. GDP rose by 0.6 per cent in the 3rd quarter after a growth rate of 0.5 per cent in the 1st quarter and 0.9 per cent in the 2nd quarter.

As opposed to real GDP, nominal GDP has been flat since the middle of 2001. The strong GDP growth in constant prices according to the latest national accounts is thus the result of an amplified decrease in the GDP deflator, i.e. the price index adjusting the GDP development from current to constant prices, cf. the left-hand panel of Chart 6. The de-crease is attributable to e.g. a strong drop in the deflator for business investments and is significant compared to the corresponding deflator in the USA, cf. the right-hand panel of Chart 6. Real GDP has to a certain extent shown the opposite pattern of the All Activity Index. This index represents weighted indicators for output in the manufacturing, con-struction and service sectors and thus covers most of the economy. Since the beginning of 2002, the growth rate of this index has been somewhat lower than that of GDP.

The most recent increase was primarily driven by business investments and exports. The course of business investments should be viewed in the

NOMINAL AND REAL GDP IN JAPAN Chart 6

Source: EcoWin.

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

110

115

Index, 1995=100

Business investments, Japan Business investments, USA1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

Deflation of business investments in Japan and the USAGDP deflator and real and nominal GDP

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

110

115

Index, 1st qrt. 1995 = 100

GDP deflator Real GDP Nominal GDP1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

8

light of improved earnings in business enterprises. Despite the good growth rates recently, Japan's structural problems persist, e.g. in the financial sector.

The labour market has improved a little. Employment has risen slightly over the past year, and in the 2nd and 3rd quarters wages have been almost unchanged against the previous year, cf. Chart 7.

The decreasing price trend has also subsided. The lower deflation rate is partly attributable to temporary factors, although increasing demand and the labour-market improvements may also have exerted upward pressure on prices. The Bank of Japan has eased monetary policy further and stated that it intends to pursue expansionary monetary policy until inflation has been positive for a prolonged period and until the Bank of Japan's forecasts show that this will continue.

The euro area The euro area economy shows weak signs of improvement after the stag-nation in the 1st half of the year. GDP growth was 0.4 per cent in the 3rd quarter according to the flash estimate. The preliminary data show GDP growth in both Germany (0.2 per cent), France (0.4 per cent) and Italy (0.5 per cent). In all three countries the increase was driven by exports.

The GDP growth is in line with the fact that business confidence indi-cators since the spring have pointed towards increased activity towards the end of the year. The German IFO index has risen in the last months.

WAGE AND PRICE INCREASES IN JAPAN Chart 7

Source: EcoWin.

-2.0

-1.5

-1.0

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

Wage-increase rate Inflation

2000 2001 2002 2003

Per cent, year-on-year

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

9

Until recently, the increase primarily reflected growing optimism con-cerning the future. A similar pattern was observed in 2002 when the improvement in the indicators did not materialise. In view of the latest increases in the index concerning the current situation, cf. Chart 8, this pattern is less likely to repeat itself.

A comparison with previous business cycles shows that it is not abnor-mal for an economic upturn in the euro area to lag behind the US by a few quarters. The improvement in the US economy already observed is thus expected to have a positive impact on growth in the euro area, cf. Box 2.

After an increase since 2001 unemployment stabilised at just over 9 per cent over the summer. Despite the very subdued economic growth since the end of 2001, employment has been relatively stable. Con-versely, the USA has seen stronger activity, but decreasing employment. The increase in labour productivity in the USA has thus been consider-ably stronger than in the euro area, cf. Chart 9. One likely explanation is rigid labour-market structures in some euro area member states.

The German and French governments continue their reform efforts in an attempt to reduce the high unemployment and boost economic growth. The reforms are followed up by income-tax cuts in both coun-tries. In October, the Bundestag voted in favour of more labour market measures. This represented another step towards implementation of the reforms in Agenda 2010. The measures include lower unemployment

IFO INDEX FOR THE FORMER WEST GERMANY Chart 8

Source: EcoWin.

75

80

85

90

95

100

105

110

115

120

Index, 1991 = 100

Total Expectation of future situation Assessment of current situation

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

10

benefit and a more stringent unemployment benefit regime. At the same time, the Bundestag adopted earlier implementation of a tax re-form whereby income-tax cuts will become effective already in 2004.

EFFECT ON THE EURO AREA OF RISING DEMAND IN THE USA Box 2

Rising demand in the USA can have a positive impact on activity in the euro area. This is

not only due to the direct trade channel between the euro area and the USA, but also to

increased integration of the financial markets and the resulting effects on confidence.

Euro area exports (excluding intra-euro area trade) account for approximately 15

per cent of GDP. Exports to the USA account for approximately 15 per cent of this

share. The direct trade channel thus explains part of the increase in euro area exports,

but the general increase in world trade also plays a role. Besides the direct trade

channel the integration of the financial markets can also have an effect via interest

rates and stock prices. Another factor, which is more difficult to measure, is the effect

on investments and private consumption of increased confidence in the euro area as a

result of higher growth in the USA.

In the global macromodel NiGEM1 a positive shock to private consumption in the

USA of 1 per cent of GDP is simulated. In the model, private consumption will sub-

sequently be higher than normal since consumption in a certain period depends on

consumption in the preceding period. GDP will rise immediately, followed by a

gradual dampening of the effect, cf. the Chart (left-hand panel). The positive shock

to demand in the USA will affect euro area exports by approximately 0.7 per cent in

the first two quarters and GDP by just under 0.2 per cent, cf. the Chart (right-hand

panel). The effect will subsequently decline. The increase in GDP can be explained

by rising exports to the USA, but also rising exports to other countries in view of

the expansion of world trade, cf. the Chart (right-hand panel). The increase in con-

sumption in the USA thus benefits the whole world in the form of increased trade.

EFFECT ON THE EURO AREA OF A SHOCK TO PRIVATE CONSUMPTION IN THE USA

Note: Source:

The effect is compiled as the percentage deviation from a base line scenario. Own calculations in NiGEM.

Monetary policy in both the USA and the euro area is subject to a Taylor rule in the

simulation whereby monetary policy will be tightened if the output gap widens. In

the longer term, this will bring the model back to equilibrium.

NiGEM does not account for a possible effect via the confidence channel and only

partly accounts for the effect via the financial markets. The effect on GDP in the euro

area is thus probably underestimated.

1 NiGEM is compiled by the National Institute of Social and Economic Research in London.

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

0 1 2 3Quarters after shock

Per cent

Private consumption in the USA GDP in the USA

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

0 1 2 3Quarters after shock

Per cent

Euro area eports GDP in the euro area World trade

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

11

Before the bills can become law, most of them must, however, be proc-essed by the Bundesrat where they have already been rejected once. In France, in connection with the adopted pension reform that will tighten the requirements concerning full pension entitlement in the public sec-tor, a debate of health and labour-market reforms has been initiated. These reforms should go hand in hand with income-tax cuts in 2004.

Several member states' government budget deficits are expected to exceed the limit of 3 per cent of GDP stipulated in the EU Treaty, cf. Chart 10. The worst cases are France and Germany, whose deficits are expected by the European Commission1 to be around 4 per cent for 2003 and 2004. Against this background, the European Commission in October recommended to the Council of Ministers for Economic Affairs and Finance, Ecofin, that notice be given to France to take measures to tighten fiscal-policy in 2004 and 2005 to bring the budget deficit below 3 per cent of GDP by 2005 at the latest. In the middle of November the Commission made a similar recommendation for Germany. If these recommendations are adopted (which was not yet the case at the time of going to press), and if the countries fail to comply, the next step will be to impose sanctions against the two countries. With the recommen-dations for France and Germany the Commission has already stretched

1 The European Commission's autumn forecast 2003.

PRODUCTIVITY IN THE EURO AREA AND THE USA Chart 9

Note: Source:

The latest observation for the euro area is the 2nd quarter since employment data for the 3rd quarter are not yet available. EcoWin.

96

98

100

102

104

106

108

Index, 2001 = 100

Euro area USA

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

12

the interpretation of the Stability and Growth Pact to take into ac-count their low economic growth. The fact that the Commission's pro-posal has attracted considerable attention shows that the Stability and Growth Pact works and that it encourages implementation of respon-sible fiscal policy compared to a situation without such rules. Neverthe-less, the upcoming decisions on France and Germany, including whether the Commission's proposal will be further softened, will have a significant impact on the Stability and Growth Pact's "bite" in the future.

Inflation in the euro area has been stable at around 2 per cent since April and was 2 per cent in October with certain variations across the member states.1 Core inflation2 declined during 2002 and has been close to 1.7 per cent in recent months. This was also the level in October. The ECB has made no adjustment to monetary policy since the reduction of the minimum bid rate by 0.5 per cent to 2 per cent in June.

UK The UK economy was almost unaffected by the international economic slowdown thanks to strong domestic demand. A significant adjustment of the national accounts for the 2nd quarter showed that the growth

1 Cf. Inflation Differentials in the Euro Area p. 41 ff.

2 HICP excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco.

EXPECTED BUDGET BALANCE IN THE EU MEMBER STATES Chart 10

Source: The European Commission's autumn forecast 2003.

-5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3

Finland

Denmark

Sweden

Belgium

Spain

Luxembourg

Ireland

Austria

Greece

Netherlands

Italy

UK

Portugal

Germany

Frace

Per cent of GDP

2003 2004

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

13

rate was 0.6 per cent in the 2nd quarter as well as in the 3rd quarter. Since retail sales and consumer confidence rose in the 3rd quarter, pri-vate consumption continued to be a significant growth factor.

As in the USA, fiscal policy and monetary policy provided strong stimu-li, cf. Chart 5. The European Commission expects a budget deficit of 2.8 per cent in 2003. The low interest rates have supported the housing market, where house prices have increased for a long time. House prices also rose in the period August-October, thereby continuing to stimulate private consumption to a considerable extent.

In November, the Bank of England raised the interest rate by 25 basis points to 3.75 per cent. As the basis for its decision the Monetary Policy Committee stated that credit is still strong, and both private consump-tion and the housing market have slowed less than expected. The rate of increase in house prices is still the principal explanation of the difference between HICP inflation and RPIX inflation, which were 1.4 per cent and 2.7 per cent, respectively, in October. Unlike the RPIX index, the HICP does not include house prices (via rent).

Sweden Sweden saw subdued growth in the 1st half of 2003. Exports nevertheless increased, despite the international economic slowdown, while domestic activity was dampened by unchanged investments and modest growth in public consumption. Private consumption was relatively strong, and fa-vourable retail sales observations from July to September indicate that this tendency continued in the 3rd quarter.

The monetary-policy interest rate has not been changed since the re-duction in July to 2.75 per cent. Inflation measured by the UND1X index was 1.9 per cent in October. Inflation has thus decreased from the high level at the beginning of the year, which was primarily attributable to rising energy prices.

In the referendum on 14 September the Swedish population rejected EMU membership. Just over 56 per cent voted against membership, while just under 42 per cent voted in favour. This result was expected in the financial markets and caused moderate reactions. The Swedish krona weakened briefly after the result, but has strengthened a little since then.

Norway Mainland GDP in Norway moved sideways in the 1st half of the year. The economy was severely affected by the international economic slowdown that coincided with the domestic cost pressure and the strong Nor-wegian krone in 2002, which had a severe adverse impact on Norway's

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

14

competitiveness. However, the rate of wage increase was dampened by rising unemployment.

The appreciation of the Norwegian krone in 2002 exerted downward pressure on inflation measured by the KPI-JAE index which declined to below the target of 2.5 per cent. Inflation was 0.9 per cent in August and September. On 17 September Norges Bank lowered the interest rate for the seventh time since December 2002, and the Norwegian krone has depreciated by approximately 10 per cent in effective terms since the turn of the year.

The government's budget proposal for 2004 shows a government defi-cit in even greater conflict with Handlingsreglen (Guideline) than in 2002 and 2003. According to Handlingsreglen the structural non-oil budget deficit must be equivalent to the expected real return on the Petroleum Fund.

The 10 acceding countries The acceding countries have seen relatively robust growth, despite the international economic slowdown. However, growth declined in the 2nd quarter in Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and the Baltic states, while the expansion of the Polish economy, which started from a trough at the end of 2001, continued. On the other hand, the European Commission expects a significant deterioration of Poland's government budget deficit in 2004. Poland is definitely not the only acceding country with a large government budget deficit. The deficits of Hungary, Slo-vakia, the Czech Republic, Cyprus and Malta are also expected to consid-erably exceed 3 per cent of GDP in 2003 according to the Commission's estimates. The Czech Republic is the extreme case with an expected defi-cit of 8.0 per cent.

In September, both Estonia and Latvia approved EU membership in referendums. It has thus been finally resolved that all ten acceding coun-tries will become EU member states on 1 May 2004.

Argentina In September, Argentina concluded a new agreement with the Interna-tional Monetary Fund, IMF, on a new 3-year arrangement to borrow for a total of 12.5 billion dollars. Prior to the conclusion of the agreement Argentina had defaulted on a payment of 3 billion dollars to the IMF. This was the largest default in the IMF's history, and at the same time Argentina is the first major country to default on its obligations vis-à-vis the IMF.

In the IMF voting procedure on the new arrangement to borrow the Nordic-Baltic constituency and some other countries abstained. In the

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

15

opinion of the Nordic-Baltic constituency the arrangement did not meet a number of the important requirements which are normally imposed on countries facing an economic crisis. It is therefore questionable whether the arrangement will help to restore confidence among inter-national creditors and investors.

THE DEVELOPMENT IN THE DANISH FINANCIAL MARKETS

In the period under review the Danish krone has been stable at a level slightly stronger than the central rate in ERM II of kr. 7.46038 per euro. Danmarks Nationalbank intervened little in the foreign-exchange mar-ket. In September and October the foreign-exchange reserve decreased by kr. 1.5 billion to kr. 228.5 billion at the beginning of November.

On 8 September the Danish krone was included in the international currency settlement system, CLS Bank International. This system thus provides for settlement of transactions in 11 different currencies: the US, Canadian, Singapore and Australian dollars, the euro, the pound ster-ling, the Swiss franc, the Japanese yen, the Norwegian and Danish kroner and the Swedish krona. The increased number of currencies in CLS reduces the settlement risk in international foreign-exchange trad-ing. However, the operational risk is concentrated. An automated sys-tem for cross-border collateral between Denmark, Norway and Sweden has been developed to facilitate Scandinavian CLS participants' access to intraday liquidity in the Scandinavian currencies, cf. below on the Scan-dinavian Cash Pool, p. 23.

In the period under review, Danmarks Nationalbank did not adjust the lending rate, the current-account rate or the discount rate, cf. Chart 11. In mid-November, the lending rate thus remained at the level after the last interest-rate reduction in June, i.e. 2.15 per cent, while the current account rate and the discount rate were 2 per cent.

Long-term yields showed the same pattern as long-term yields in the USA and the euro area. The period thus began with an interest-rate decrease, which was replaced by an increase. For the period as whole, the level of interest rates was almost unchanged.

On 23 September, most of eastern Denmark experienced a power fail-ure for a few hours during the day. The power failure did not cause any major problems in the money market. In connection with the power failure, Danmarks Nationalbank contributed liquidity in the form of extraordinary repurchases of certificates of deposit.

In August the ECB announced that the maturity of monetary-policy loans in the euro area would be reduced from 14 to 7 days with effect from the tender on 9 March 2004. Danmarks Nationalbank has chosen to

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

16

retain a maturity of 14 days for its monetary-policy loans and certificates of deposit. This maturity has proved suitable for management of the liquidity in kroner, and the experience with Danmarks Nationalbank's monetary-policy instruments has generally been good.1

Lending by banks and mortgage-credit institutes increased by ap-proximately 6 per cent in 2003 against 2002, cf. Chart 12. Growth in lending to households has been almost two percentage points above average, while growth in lending to business enterprises has been a few percentage points below average.

The households' loans from banks and mortgage-credit institutes are not always used for consumption or investment in real assets. The households may choose to place the borrowed funds in financial assets such as securities and deposits. The recent relatively high growth in lend-ing to households may thus reflect some households' borrowing now for planned expenditure later.

A more complete picture of the households' loans and placements can be achieved by including other financial statistics, cf. Box 3. This shows that the increase in lending to households in the first two quarters of 2003 was almost offset by financial placements. In the 3rd quarter of 2003 the households' net financial savings decreased significantly against the 3rd quarter of 2002. This estimate of the households' net financial savings is subject to some uncertainty, but the decrease may be the first sign of acceleration in the households' consumption and hous-ing investments.

As from 1 October amended legislation allowed the mortgage-credit institutes to offer mortgage-credit loans where amortisation is deferred for up to 10 years. Deferred-amortisation loans can be fixed-rate or adjustable-rate loans. The deferred-amortisation period can be placed at the beginning of the loan's term or it can be selected or deselected as requested by the borrower. Deferred-amortisation loans can be re-financed by raising new deferred-amortisation loans. The deferred-amortisation period can thus be prolonged beyond 10 years. However, refinancing requires reassessment of the collateral by the mortgage-credit institute to ensure compliance with the loan limits.

The introduction of deferred-amortisation loans widens the range of products available to the consumers, which is positive. However, this makes greater demand on advice in order to give the borrower an over-view of the current and future financial situation.

1 Recent years' experience with the use of monetary-policy instruments in Denmark is described in the

article Use of Monetary-Policy Instruments, Danmarks Nationalbank, Monetary Review, 1st Quarter 2003.

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

17

INTEREST RATES IN DENMARK Chart 11

Source: DN database and EcoWin.

LENDING BY BANKS AND MORTGAGE-CREDIT INSTITUTES Chart 12

Note: Source:

Business includes non-financial and financial corporations, excluding monetary financial institutions. Danmarks Nationalbank.

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov

Per cent

Discount rate Lending rate 3-month Cibor 10-year government bond yield

2002 2003

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Households Business Total

Per cent, year-on-year

19991998 2000 2001 2002 2003

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

18

THE COMPILATION OF HOUSEHOLD LOANS AND PLACEMENTS Box 3

Danmarks Nationalbank currently publishes a range of monthly financial statistics

with a short delay. These statistics can be used for an early compilation of the loans

and placements of various sectors during the month.

The Chart shows the household sector's net financial savings broken down by major

components. The households primarily raise loans from banks and mortgage-credit

institutes (MFIs), where they also place a proportion of their savings as deposits. The

remainder of their financial savings is placed primarily in Danish and foreign securities

and in pension schemes via life assurance companies and pension funds.

HOUSEHOLDS' LOANS AN C Chart

Note: Source:

A negative value of "Loans from MFIs" indicates that the households have increased their loans. A positive value of "Deposits with MFIs" indicates that the households have increased their deposits. "Net purchases of securities, etc." includes the households' savings in pension schemes via life assurance companies and pension funds. The net financial savings are calculated here as the net item of the three bars. Danmarks Nationalbank.

The data on the households' accounts with MFIs stem from the MFI balance-sheet

statistics. Data on the households' net purchases of Danish and foreign securities are

based on Danmarks Nationalbank's securities statistics and statistics concerning finan-

cial payments to and from abroad. The households' savings via life assurance compa-

nies and pension funds are compiled as the household sector's own financial savings

in the form of net deposits with MFIs and net purchases of securities.

The monthly calculation in the Chart can in principle be made already on the 18th

banking day after the month covered by the statistics. As from the spring of 2004,

Danmarks Nationalbank will publish quarterly financial accounts of the total financial

assets and liabilities for the principal sectors of the economy. These accounts will be

based on a wider range of sources and provide a more comprehensive picture of the

loans and placements of each sector.

-40

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

40

Loans from MFIs Deposits with MFIs Net purchases of securities, ect. Net financial savings

Kr. billion

Q1 2002 Q2 2002 Q3 2002 Q4 2002 Q1 2003 Q2 2003 Q3 2003

D PLA EMENTS

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

19

THE DANISH ECONOMY

The Danish economy was not unaffected by the international economic slowdown. After a small increase in the 1st quarter, GDP decreased by 0,6 per cent in the 2nd quarter. The decrease was particularly attribut-able to domestic demand, with e.g. declining business investments, but also private consumption receded in the 1st half of 2003. Exports were affected by weak cyclical development abroad, but nevertheless fared relatively well compared to other countries' exports. Manufactured ex-ports have thus gained market shares so far in 2003.

After the slowdown in the 1st half of 2003 the Danish economy now shows sign of an upswing. Growing turnover and imports of machinery, etc. indicate a rise in business investments, cf. Chart 13. Increasing retail sales furthermore indicate growth in private consumption. In July and August retail sales were higher than in the period May-June. Car sales also increased from the very low level of the spring, but have been stable recently. The national average of growth in house prices con-tinues to exceed growth in the consumer price index. In the Greater Copenhagen area, which had previously seen the strongest price in-creases, the price for one-family houses nevertheless decreased by a few per cent in the 3rd quarter. Higher disposable income and an expected improvement of the labour market support private consumption in a

MACHINERY AND EQUIPMENT INVESTMENTS IN DENMARK Chart 13

Source: Statistics Denmark.

10

14

18

22

26

30

70

80

90

100

110

120

Machinery and equipment investments

Sales to domestic market and imports of capital goods (right-hand axis)

Kr. billion January 2000 = 100

1995 1996 1998 2000 20021997 1999 2001 2003

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

20

forward-looking perspective. Finally, exports will benefit from an upturn in the international export markets.

There are indications that the adverse development in the labour mar-ket is coming to an end. The seasonally-adjusted unemployment rate did rise in September, but although the increase offsets the fall in July and August, the indications from the spring of accelerating unemployment no longer apply. One explanation of the declining unemployment in July and August is that unemployed who were not unemployed last year received holiday pay in their summer holiday rather than daily cash benefits, whereby they were excluded from the statistics. The increase in unemployment in September was thus not surprising.

According to Statistics Denmark's quarterly compilation of public fin-ances, the general-government budget balance has shown a decreasing trend in 2003, cf. Chart 14. The statistics are available up to and includ-ing the 2nd quarter. The deterioration of the budget balance is a strong reflection of the automatic response of public finances to a weakening of the taxation base concurrently with rising expenditure for the unem-ployed. Despite the constraint implemented in 2003, public consumption has also been higher than planned. In the 1st half of 2003 public con-sumption was 1.8 per cent stronger than in the 1st half of 2002. In view of the expansion by 2.1 per cent in 2002 it will be more than difficult to meet the target of an increase in public consumption by 2 per cent for 2002 and 2003 taken as one.

GENERAL GOVERNMENT BUDGET BALANCE IN DENMARK Chart 14

Source: Statistics Denmark.

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

Per cent of GDP

General government budget balance, 4-quarter moving average

2000 2001 2002 2003

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

21

The rising trend in the surplus on the current-account of the balance of payments continued in August and September. The surplus for the last 12 months was approximately kr. 36 billion in September, i.e. approxi-mately kr. 9 billion higher than in the preceding 12-month period. The increase is attributable to improvements in the balance of goods and services. Both imports and exports rose in September, and the increase in exports followed a pronounced decline in the preceding months. The improvement of the balance of payments and the declining government surplus in the 1st half of 2003 imply a clear increase in the private sec-tor's saving surplus. This increase can be regarded as an automatic cycli-cal reaction, as it reflects weak development in private consumption and investments, cf. the earlier remarks on the statistics on the private sec-tor's net financial placements.

The sluggish labour market is reflected in the pattern of prices and wages. The annual rate of wage increase within the Danish Employers' Confederation's area subsided throughout the year and was 3.6 per cent in the 3rd quarter.

Inflation measured by the HICP index has receded a little during the year. Recently, inflation has been subdued by declining growth in im-port prices as the effective krone rate increased, cf. Chart 15. HICP infla-tion was 1.7 per cent in September and 1.1 per cent in October. The fall from September to October primarily reflects lower indirect taxes on alcohol and cigarettes. Inflation in Denmark is thus still a little lower

PRICES AND EXCHANGE RATE FOR DENMARK Chart 15

Source: Statistics Denmark and own calculations.

-2

0

2

4

6

8

94

96

98

100

102

1041980 = 100

HICP Price index, imports Nominal effective exchange rate (right-hand axis)

20002000 20022001 2002 2003

Per cent, year-on-year

12-12-2003 07:24 Antal sider: 22 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\001-022.doc

Oprettet af Alice Colombo

22

than inflation in the euro area. Nevertheless, the increase in the HICP excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco was 2.4 per cent in October in Denmark against 1.7 per cent in the euro area. Domestic market-determined inflation has overall shown a declining trend during 2003 to around 2 per cent, but rose to 2.5 per cent in October, cf. the Tables and Graphs Section. The principal factor contributing to the latest increase is that falling import prices did not fully lead to lower consumer prices for imported goods.

12-12-2003 07:25 Antal sider: 3 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\023-025.doc

Oprettet af Lone Natorp

23

SCP – Scandinavian Cash Pool

SCP is an automated system for the pledging of cross-border collateral between Denmark, Norway and Sweden. The system was developed in order to facilitate the Scandinavian CLS1 participants' access to intraday liquidity in the Scandinavian currencies.

The main principle of SCP is that liquidity raised at the central bank of one country may be pledged as collateral for loans from the central bank of another country. The participant pledges collateral at the na-tional central bank by transferring liquidity to a special account that is pledged to the foreign central bank. The latter is notified automatically of the pledged amount and on that basis grants credit to the particip-ant. When the participant has repaid the loan to the foreign central bank, the national central bank is informed automatically that the col-lateral may be released, i.e. the amount on the pledged account is automatically transferred back to the participant's current account. SCP may only be used to pledge collateral for intraday credit. 2

SCP is based on existing structures and systems. The liquidity is raised at the national central bank according to national procedures and within national systems. The liquidity is pledged to the foreign central bank via an ordinary transfer between accounts in the national RTGS system. The communication between the central banks is automated and based on existing standards (SWIFT). This structure ensures that cross-border collateral can be pledged via SCP in less than one minute.

BACKGROUND TO AND USE OF SCP

The Scandinavian currencies became part of CLS in September 2003. As a consequence the requirements of the participants' procurement of li-quidity in these currencies have been expanded. Moreover, three of the Scandinavian participants have made a commitment to contribute to the CLS Liquidity Facilities in all three currencies, which means that they must be able to raise large amounts in one or several of the Scandin-

1 CLS (Continuous Linked Settlement) is an international foreign-exchange settlement system. For

further information, see Financial Stability, 2003 page 97. 2 For further information on SCP reference is made to www.nationalbanken.dk under Tasks/Payment

systems/Collateral. For a description of the legal basis for SCP, see Niels C. Andersen and Kirsten Gürt-ler, The Provision of Collateral to Danmarks Nationalbank in a Legal Perspective, Danmarks National-bank, Monetary Review, 3rd Quarter 2003.

12-12-2003 07:25 Antal sider: 3 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\023-025.doc

Oprettet af Lone Natorp

24

avian currencies at short notice. CLS is the primary reason for the estab-lishment of SCP.

However, the use of SCP is not limited to CLS purposes, and the system is open to other than the CLS banks. For instance, SCP will make it pos-sible for banks with activities in more than one Scandinavian country to centralise the pledging of collateral and liquidity management in one country and nonetheless still cover their intraday liquidity requirements in the two other countries.

Today four of the five Scandinavian CLS participants also participate in SCP. During the first month after the Scandinavian currencies became part of CLS, SPC was primarily used to pledge collateral in Denmark in order to obtain intraday liquidity in Norway and Sweden. The explana-tion may be that the participants primarily hold their collateral in Den-mark, or that the payments to CLS are relatively larger in Sweden and Norway compared to the liquidity available in the country in question.

FOCUS ON CROSS-BORDER PLEDGING OF COLLATERAL

The establishment of CLS has generally increased focus on the possibility of pledging cross-border collateral. Particularly the large international banks are motivated by other factors besides CLS to require easier access to cross-border intraday liquidity. In March 2003 a task force under The Payments Risk Committee set up by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York with participants from 13 large international banks published a report on cross-border pledging of collateral and access to intraday liquidity.1

According to the report, the need for cross-border intraday liquidity is increasing. The internationalisation of the financial markets entails that banks increasingly operate beyond their domestic markets. The banks represented in the task force state that around half their payment activ-ities take place in foreign markets, and therefore they require cross-border liquidity. Over the years payment and settlement systems have moreover been introduced which in many ways enhance the overall security of the financial system, but which also make higher demands of the participants' liquidity procurement. CLS is only the most recent example.

The task force recommends that the central banks for the CLS cur-rencies to a larger extent accept securities denominated in foreign cur-rencies as collateral for intraday liquidity. In addition, the task force set

1 The Payments Risk Committee, Report by the Cross-border Collateral Pool Task Force, Managing

Payment Liquidity in Global Markets: Risk Issues and Solutions.

12-12-2003 07:25 Antal sider: 3 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\023-025.doc

Oprettet af Lone Natorp

25

out a number of models for how the central banks might build up an infrastructure for the pledging of cross-border collateral. The models are described in the Box.

On the basis of the report, the opportunities and requirements for fa-cilitating access to cross-border liquidity are being discussed among the central banks. It is clear that in the first instance the need for a facility for pledging cross-border collateral is greatest among the large inter-national players participating in payment settlement in the USA, Europe and Asia. On the other hand, easier access to cross-border intraday liquidity may serve as an incentive to smaller banks to increase their international activities.

MODELS FOR PLEDGING CROSS-BORDER COLLATERAL Box

In the Risk Committee's report the proposed facilities for pledging cross-border collat-

eral are collectively referred to as Cross-border Collateral Pool Facilities. Three basic

models are described. For two of them different options are presented:

• Securities Collateral Pool: In this model, market participants would be able to utilise

foreign securities as collateral for intraday credit at a central bank. The report rec-

ommends an option where all central banks open custodian accounts with one or

perhaps two international central securities depositories (CSDs). A bank requesting

credit in a given currency transfers securities to the account of the relevant central

bank. The CSD notifies the central bank that securities have been pledged as collat-

eral, after which the central bank grants the credit.

• Cash Collateral Pool: In this model, market participants would be able to pledge

foreign currency to a central bank as collateral for intraday credit. One option en-

tails that all central banks open accounts with each other. A bank wishing to pledge

collateral in e.g. US dollars and obtain intraday credit in e.g. pounds sterling, trans-

fers dollars to the Bank of England's account at the Federal Reserve Bank. Against

collateral in this deposit the Bank of England provides credit in sterling. A drawback

of the Cash model is that it cannot be used if one of the central banks is closed.

• Central Bank Guarantee Model: This model is based on the central banks guaran-

teeing each other that collateral has been pledged, either as securities or cash.

When a bank has transferred the collateral to a special guarantee account at a cen-

tral bank, the central bank granting the intraday credit is notified. This model also

requires that the central banks are open at the same time.

The overall recommendation in the report is the establishment of a Securities Collat-

eral Pool. Securities and CSDs are well-known elements of the existing arrangements

for pledging collateral to central banks, and the model functions across time zones.

SCP is a combination of elements from the Cash Collateral Model and the Central

Bank Guarantee Model.

12-12-2003 07:26 Antal sider: 1 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\027.doc Opret-

tet af Kristian Sparre Andersen

27

New Statistics Database at Danmarks Nationalbank's Website

On 29 October Danmarks Nationalbank added a new statistics database to its website, www.nationalbanken.dk. The database contains more than 10,000 time series on 8 different topics. The content of the data-base is expanded on an ongoing basis and by the beginning of 2004 will comprise 12 topics covering the entire spectrum of financial statistics published by Danmarks Nationalbank.

The new database supplements the ordinary statistical publications, comprising the "Nyt" series and the corresponding tables supplements, on the website. Within each topic the database will as a minimum con-tain all time series included in the publications, but in the longer term the database will include far more time series in the form of supple-mentary specifications of the main items of the statistics.

The database will not lead to any changes in the statistical publica-tions. The "Nyt" publications will still highlight and comment in more detail on the most significant development trends in order to support users' application of the statistics.

In future, the database will be updated simultaneously with the issue of the statistical publications.

The database is accessed by downloading predefined tables or by users defining tables with the required time series. In both cases it is possible to choose between different file formats and to indicate the period to be covered by the series. In addition, users have the option to save a search result for later use, e.g. when new data is released for the statis-tics covered by the search.

12-12-2003 07:29 Antal sider: 11 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\029-039.doc

Oprettet af Josephine Rasmussen

29

Volatility in Inflation and Economic Activity in the Nordic Countries

Anders Møller Christensen and Niels Lynggård Hansen, Economics

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the Nordic countries have been on different tracks in monetary policy. Finland participates in the single European currency, the euro, and Denmark pursues a fixed-exchange-rate policy vis-à-vis the euro. Both countries have thus given up their independent monetary policy to gain stable exchange-rate relations instead. Already in 1993 Sweden announced that an inflation target of 2 per cent would apply to monetary policy as from 1995, whereby the exchange rate would not be managed, but determined by market forces. In 2001, Norway applied an inflation target, but in practice the transition from the fixed-exchange-rate policy vis-à-vis a basket of currencies was gradual and took several years.

Monetary and exchange-rate policy are central elements of the overall economic policy. Based on the Nordic countries' different monetary-policy regimes this article compares the economic development in these four countries in certain areas where differences in monetary policy theoretically should emerge. An outline of the framework for stabilisa-tion policy, including monetary policy, is followed by an analysis of the movements in central macroeconomic variables in the Nordic countries. Finally, possible explanations are offered for differences in the devel-opment of these variables. Iceland is excluded from the analysis since its population is so much smaller than the other Nordic populations that for this reason alone its economy shows far greater fluctuation. In contrast, the other Nordic countries are relatively similar in size and enjoy so many common characteristics concerning the way society operates that a comparison makes sense.

The comparison shows that Denmark's economic performance in re-cent years has been more stable than that of the other Nordic countries. However, so many other factors besides economic policy have been part of the development that it is difficult to draw any firm conclusion from an analysis of this type. Such analyses are more useful for asking ques-

12-12-2003 07:29 Antal sider: 11 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\029-039.doc

Oprettet af Josephine Rasmussen

30

tions than for providing unequivocal answers, but relevant questions make a good driving force for future analyses.

Bearing in mind these caveats one possible explanation is that medium-term orientation of fiscal policy and a consistent fixed-exchange-rate policy shield an economy from the domestic shocks at-tributable to short-sighted fiscal policy and exchange-rate fluctuations. At the same time, the automatic stabilisers of fiscal policy cushion a ma-jor proportion of the external shocks in an appropriate manner.

THE OPPORTUNITIES AND LIMITATIONS OF STABILISATION POLICY

Stabilisation policy is normally taken to mean economic policy designed to dampen the fluctuations in inflation and activity, cf. the Box, which describes a frequently used theoretical framework for stabilisation pol-icy. Monetary and fiscal policy are the most important forms of stabilisa-tion policy.

The level and development of the average standard of living depends primarily on productivity in the broader sense. Key issues in this connec-

A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK FOR STABILISATION POLICY Box

The theoretical literature on stabilisation policy1 largely agrees that the long-term un-

employment level – or the long-term potential output level, i.e. the output level

compatible with stable price development in the medium term, cannot be influenced to

any significant extent by stabilisation policy. The latter determines whether inflation is

low or high on average, as well as the extent of deviation between actual and potential

output on the one hand and actual and average inflation on the other hand. More fun-

damental factors such as the long-term unemployment level are determined by struc-

tural factors.

To be more specific, current inflation is determined by historical inflation (+), ex-

pected future inflation (+), the deviation of output from the potential level, i.e. out-

put gap (+) and whether the exchange rate is weaker (+) or stronger than its equilib-

rium level. The signs in brackets signify the effect. The current output gap is deter-

mined by the output gap in preceding periods (+), expected output gap in coming

periods (+), whether the exchange rate is weaker (+) or stronger than its equilibrium

level and whether interest rates are lower (+) or higher than the so-called natural

level. Both inflation and the output gap are furthermore affected by shocks to the

economy. Other factors can also be considered, e.g. fiscal policy, which is regarded as

given and thus unaffected by the development in the variables analysed, i.e. inflation,

output gap, interest rates and exchange rate. The optimum course of interest rates

can be determined by adding a supplementary model for the exchange rate and

knowledge of the trade-off between the output gap and the deviation of inflation

from the desired level as perceived by the authorities. A less ambitious aim is to ana-

lyse the implications of various ways to determine interest rates.

12-12-2003 07:29 Antal sider: 11 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\029-039.doc

Oprettet af Josephine Rasmussen

31

CONTINUED Box

Due to shocks and historical factors the output gap will always vary and inflation will

always deviate from the desired level. The model described here implies an immediate

contrast between the two considerations. The objective of the interest-rate policy is to

ensure a politically wanted trade-off between the two. The contrast disappears in the

longer term, so that only the choice between high or low inflation remains, while the

output gap continues to vary around zero.

The immediate trade-off between a low degree of volatility in the output gap and

a low degree of volatility in inflation around the desired level can be illustrated in a

so-called Taylor curve, cf. Chart 1. If the authorities attach great importance to stabili-

sation of inflation, they have to put up with a high degree of variability in the output

gap. This is the case if the central bank is an inflation nutter2. This corresponds to the

SIT point (Strict Inflation Target). It is necessary to accept very large unemployment fluc-

tuations in order to further stabilise inflation. Conversely, the more weight is attached

to keeping unemployment close to the sustainable level in the longer term, i.e. an out-

put gap close to zero, the more unstable inflation will be illustrated by the SOT point

(Strict Output-Gap Target). The FIT point (Flexible Inflation Target) describes a more

normal situation where both factors are considered important. The plotted curve shows

possible efficient outcomes. Basically, the position of the curve is determined by the

shocks to the economy. The smaller the shock, the more southwesterly the curve. A

credible and clear monetary policy is also believed to push the curve in this direction.

The points below the curve cannot be achieved using stabilisation-policy measures,

while points above and to the right of the curve reflect inefficient stabilisation policy.

From point A it is always possible to achieve improvements in one direction without any

costs pulling in the other direction.

TRADE OFF BETWEEN VARIABILITY IN INFLATION AND OUTPUT GAP Chart 1

1 A relatively informal review can be found in contributions to Rethinking Stabilization Policy, 2002, A Sympo-sium Sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. This Box is inspired particularly by Lars E.O. Svens-son's contribution, Monetary Policy and Real Stabilization, as well as several other contributions by the same author.

2 Mervyn King introduced the term in Changes in UK Monetary Policy: Rules and Discretion in Practice, Journal of Monetary Economics 39 (1997), pp. 81-97.

Inflation variability

FIT

SIT

SOT

*

*A

Ou

tpu

t-g

ap v

aria

bili

ty

12-12-2003 07:29 Antal sider: 11 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\029-039.doc

Oprettet af Josephine Rasmussen

32

tion are the quality of the labour force, attitudes to change and compe-tition, management competencies in business enterprises, a well-defined legal framework, taxation rules and rules concerning receipt of transfer payments, market proximity, existing resources such as climate, physical capital stock and commodities and many other issues. Several factors, including structural policy, can impact on these fundamental issues.

In practice, there is no sharp distinction between stabilisation policy and structural policy. Any change of tax rules will thus affect both the short-term economic course by dampening or strengthening fluctuations and the long-term course by influencing the population's incentive to e.g. look for work or make purchases across national borders. Similarly, interest and exchange-rate fluctuations may have more long-term impli-cations for the dynamics in society, since they affect the realised as well as the expected future return on investment in real capital. Notwith-standing these caveats, a distinction between stabilisation policy and structural policy must be regarded as useful.

In Sweden and Norway, monetary policy is based on flexible inflation targeting regimes. Applying the theoretical framework outlined in the Box, this provides a good and politically desirable trade-off between the variability in inflation and in the output gap. According to this theoret-ical framework, a fixed-exchange-rate policy implies a less-than-optimum trade-off between the targets1, e.g. corresponding to point A in Chart 1.

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

Inflation measured as the rate of increase in the HICP, the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices in Europe, and the output gap2 for the four Nordic countries since 1996 is shown in Chart 2. Table 1 shows lower variability in inflation, unemployment and output in Denmark than in the other Nordic countries3. Output variability was clearly lowest in Denmark, unemployment variability showed more similar patterns, with Denmark at the low end, while inflation variability in Denmark was only half the level in Sweden and Norway. Finland was somewhere in the middle.

The choice of period was determined by two factors. Firstly, the HICP began to be published in 1995, so it is not possible to calculate the infla-

1 Cf. Lars E.O. Svensson, Exchange Rate Target or Inflation Target for Norway, in Anne Berit

Christiansen and Jan Fredrik Qvigstad (ed.), Choosing a Monetary Policy Target, Oslo 1997 and p. 268 in the reference to the same author in the Box.

2 Defined as actual output less potential output as a percentage of potential output.

3 Assuming an independent normal distribution of inflation rates, the volatility in inflation in Denmark

is significantly lower than in Norway and Sweden.

12-12-2003 07:29 Antal sider: 11 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\029-039.doc

Oprettet af Josephine Rasmussen

33

tion rate before January 1996. Secondly, the early 1990s represented a very turbulent period in Sweden and Finland, which would perform very poorly in a comparison including these years. Such a comparison would not account for the shift in economic policy that was initiated around 1993. Taking 1996 as the starting year means that the initial difficulties will not affect the results significantly.

Furthermore, it should be noted that the narrower price measures en-

tering monetary-policy making in Norway and Sweden show a lower

degree of variability than the HICP. Norway applies the KPI-JAE, i.e. the

consumer-price index adjusted for indirect taxes and energy products, as

HICP AND OUTPUT GAP, 1996-2003 Chart 2

Note: Source:

Output gaps for 2003 are OECD estimates. The most recent HICP observation is from October 2003. Eurostat and OECD, Economic Outlook 73.

STANDARD DEVIATION FOR THE PERIOD 1996-2003 Table 1

Denmark Finland Norway Sweden

HICP, per cent, year-on-year ............................ 0.53 0.78 1.02 0.90 Applied inflation target1, per cent, year-on-year ..................................................... .. .. 0.65 0.76 Output gap, per cent of GDP .......................... 0.67 2.13 1.08 1.83 Unemployment rate, change month-on-month .............................................

0.13 0.10 0.14 0.24

Source: Eurostat and OECD, Economic Outlook 73. 1 Norway applies the KPI-JAE, and Sweden applies the UND1X. The KPI-JAE is available only as from August 1999, and

the rate of increase is thus measured as from August 2000.

-0,5

0,0

0,5

1,0

1,5

2,0

2,5

3,0

3,5

4,0

4,5

-7

-6

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3Per cent, year-on-year Per cent of GDP

Finland

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003-0,5

0,0

0,5

1,0

1,5

2,0

2,5

3,0

3,5

4,0

4,5

-7

-6

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3Per cent, year-on-year Per cent of GDP

Denmark

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

-0,5

0,0

0,5

1,0

1,5

2,0

2,5

3,0

3,5

4,0

4,5

-7

-6

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3Per cent, year-on-year Per cent of GDP

Norway

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003-0,5

0,0

0,5

1,0

1,5

2,0

2,5

3,0

3,5

4,0

4,5

-7

-6

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3Per cent, year-on-year Per cent of GDP

Sweden

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

Output-gap (right-hand axis)HICP

12-12-2003 07:29 Antal sider: 11 Rev. nr. 2 H:\kvo\ENG\2003\4qtr\tiltryk\029-039.doc

Oprettet af Josephine Rasmussen

34

target variable in monetary policy. In Sweden, the UND1X, i.e. the con-

sumer price index adjusted for indirect taxes and interest expenditure

for owner-occupied housing, plays a significant role. However, the HICP

is the most expedient measure for a comparison of the course of infla-

tion in different countries, since this is the very purpose of the HICP. Denmark seems to have performed well. Moreover, the results are re-

markable. Denmark's monetary policy is oriented towards maintaining a fixed exchange rate vis-à-vis the euro, so it does not respond to inflation or unemployment unless the foreign-exchange conditions are affected1. As mentioned, the theoretical framework described in the Box predicts that a fixed-exchange-rate policy will ceteris paribus result in higher volatility in inflation and/or output than a policy such as flexible infla-tion targeting that directly aims at dampening these fluctuations.

POSSIBLE EXPLANATIONS