Ko Puheke te maunga Ko Rangaunu te moana Ko Whangatane te awa Ko Ngai Takoto te iwi

Modeling Willingness to Pay for Coastal Tourism Resource Protection in Ko Chang Marine National...

Transcript of Modeling Willingness to Pay for Coastal Tourism Resource Protection in Ko Chang Marine National...

This article was downloaded by: [Umeå University Library]On: 15 November 2014, At: 14:21Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office:Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism ResearchPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscriptioninformation:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rapt20

Modeling Willingness to Pay for CoastalTourism Resource Protection in Ko ChangMarine National Park, ThailandSunida Piriyapadaa & Erda Wanga

a Department of Human Resource and Tourism Management, School ofBusiness Management, Dalian University of Technology, No. 2 LinggongRoad, Dalian 116024, People's Republic of ChinaPublished online: 29 Apr 2014.

To cite this article: Sunida Piriyapada & Erda Wang (2014): Modeling Willingness to Pay for Coastal TourismResource Protection in Ko Chang Marine National Park, Thailand, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research,DOI: 10.1080/10941665.2014.904806

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2014.904806

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”)contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and ourlicensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, orsuitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publicationare the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor &Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independentlyverified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for anylosses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilitieswhatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to orarising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantialor systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and usecan be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Modeling Willingness to Pay for Coastal TourismResource Protection in Ko Chang Marine National

Park, Thailand

Sunida Piriyapada∗

and Erda WangDepartment of Human Resource and Tourism Management, School of Business Management,

Dalian University of Technology, No. 2 Linggong Road, Dalian 116024, People’s Republic of

China

The value of non-market resources is important information for the nature-based parkinvestment and management. In this paper, we estimate visitors’ willingness to pay(WTP) an entrance fee for beach resource protection of the Ko Chang Marine Park inThailand using a standard contingent valuation method of a single-bounded (SB) anddouble-bounded (DB) dichotomous choice format. An on-site stratified sampling surveyof 409 beach visitors was conducted at the park along the White Sand Beach shoreline.By comparing the two survey methods, the average WTP for a Thai beach visitor isabout $12.01 under the SB elicitation survey and $7.27 per adult per visit under theDB elicitation method, respectively. It turns out that the foreign visitors’ WTP is twiceas much as that of Thai visitors’ WTP. These can be translated to the lower and upperbounds of an aggregated value ranging between $10.33 million and $17.41 million perannum. The policy implications for the park management are addressed.

Key words: contingent valuation, dichotomous choice, a logit model, WTP

Introduction

Beaches are not only a major source of attrac-

tions for tourists but also fundamental assets

in the natural balance of coastal ecosystems

(Birdir, Unal, Birdir, & Williams, 2013). In

consideration, Thailand possesses many valu-

able beach resources along 2600 km of the

coastline and offshore islands, which include

well-defined beach areas suitable for tourism.

Unfortunately, beaches around Thailand are

now under threat from human activities such

as solid waste, surface water pollution and

encroachment (Wattayakorn, 2006). The Ko

Chang Marine National Park (KCMNP) is

one of the most valuable coastal resources of

Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 2014http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2014.904806

∗Email: [email protected]

# 2014 Asia Pacific Tourism Association

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

all beach recreation sites, where the marine-

based tourism activities are well recognized,

which makes the island to be the key tourism

sites in Thailand. In the KCMNP, White

Sand Beach is the most popular beach visited

and its economic importance grows with a

strong concentration of tourism facilities. At

the same time, this long stretch of seacoast

has been seriously depleted and degraded

(Department of Mineral Resources, 2013),

mainly because competitive uses of natural

resources and many of them are not consistent

with environmental protection. Thus, it is

necessary to justify the various coastal

tourism projects based on a full consideration

of economics, social and environment.

While environmental resource valuation

could link human and natural systems to

ensure ecologically sustainable development

(Chen & Jim, 2008; Howarth & Farber,

2002). Most environmental goods and services,

for example, beach visits, healthy fish and wild-

life species, are not revealed in market prices. A

commonly used method to disclose a non-

market resource valuation is the contingent

valuation which is considered as the stated pre-

ference techniques; in which a market partici-

pant can be asked to state his or her

willingness to pay (WTP) for alternative levels

of the environmental resource amount and

quality improvement or willingness to accept

(WTA) for compensation with various levels

of environmental quality deterioration (Mitch-

ell & Carson, 1989). Although an abundance

of research literature on non-market resource

valuation is available, most research works

were based on the environment and conditions

in developed countries such as the USA and the

UK and seldom research work has been done in

developing countries (Wang, Shi, Kim, &

Kamata, 2013), especially so for relatively

small countries, such as Thailand. This may

be due to inadequate financial support received

from the governments and the shortage of

research personnels as well (Adjaye & Tapsu-

wan, 2008). This work asymmetry restricts

utility of the well-recognized research method

such as contingent valuation method (CVM)

(Whittington, 2002).

The objectives of this study involve the fol-

lowing three aspects: (i) to provide another

case study on non-market resource valuation

based on beach park resources in Thailand, deli-

vering more fresh empirical results to represent

the situation of the Southeast Asian countries;

(ii) to identify factors which contribute to the

level of visitors’ WTP to the park resources

and identify WTP differences between Thai

tourists and foreign visitors and (iii) to address

policy implications under alternative park man-

agement strategies. The results of this study

could be used as references for the park entrance

fees based on the beach users’ WTP.

This paper is organized as follows: second

section gives a literature review on CVM

applications to the beach resource conserva-

tion in the developed and developing

countries; third section presents the character-

istics of the studied location; fourth section

discusses the research methodology and data

collection; fifth section provides the analytical

framework and WTP results; and followed by

a final section of the conclusion.

Literature Review

The CVM is utilized to elicit individuals’ WTP

for non-market benefits or their WTA a com-

pensation for non-market costs (Mitchell &

Carson, 1989). Theoretically, the underlying

CVM is a survey-based economic method-

ology frequently created in a hypothetical

market to assess those individuals’ preferences

from the marginal utility of the environmental

values, which it could not be measured upon

2 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

actual behaviors and therefore does not have a

price in the market. Economists have tra-

ditionally a much-debated issue in the critics

of the CVM studies (Hausman, 2012) since

the CVM produces unreliable estimates due

to the hypothetical CVM data. Therefore, it

can result in economic values that are biased

upwards, affecting the validity and credibility

of the stated preference estimates (Ajzen,

Brown, & Carvajal, 2004; Collins &

Vossler, 2009; Poe & Vossler, 2011).

However, economics make efforts to eliminate

hypothetical bias in eliciting accurate econ-

omic values through a well-designed question-

naire that such bias and inconsistency has been

successfully minimized (Carson, 2012).

Many CVM studies reported economic

benefits associated with coastal and marine

resources in the developed and developing

countries (Birdir et al., 2013), the CVM has

been commonly applied to measure direct use

values in various types of marine recreational

activities such as snorkeling (Park, Bowker,

& Leeworthy, 2002), diving (Adjaye & Tapsu-

wan, 2008; Parsons & Thur, 2008) and fishing

(Yamazaki, Rust, Jennings, Lyle, & Frijlink,

2011); indirect use values include improved

surface water quality (Borg & Scarpa, 2010;

Wang et al., 2013), coastal defense (Koutrakisa

et al., 2011),beach erosion protection (Logar

& Van den Bergh, 2012) and improved beach

quality (Birdir et al., 2013). A valuation of

beach protection benefit in Thailand which is

closely related to this paper is that of Saengsu-

pavanich, Seenprachawong, Gallardoa, and

Shivakoti (2008). They use the single-

bounded (SB) elicitation CVM to estimate the

WTP for protecting a public recreational

beach at Nam Rin beach. In their study, they

attempted to integrate environmental econ-

omics and coastal engineering in managing

port-induced coastal erosion occurring at the

study beach by using Map Ta Phut port as a

case study. The result indicated that the WTP

estimates of 280 beach users for beach resource

protection were $24.8 per year. The total use

value of Nam Rin beach became approxi-

mately $2.11 million annually.

Based on the tourists’ WTP for coastal

resource protection, we found that some

studies focused on the impact of the candidate

entrance price and recommended methods for

imposing an appropriate entrance price. This

pricing policy could be used as an economic

instrument to achieve the dual goals of

revenue generation and conservation (Wang

& Jia, 2012). A case study was designed to esti-

mate the coastal resource benefits arising from

proposing biodiversity conservation and

environmental protection at Dalai Lake Pro-

tected Area in northeast China. Wang and Jia

(2012) used the CVM to assess a tourist’s

WTP an entrance fee to support park funding

and local development in order to sustain the

protected area. The results revealed that

73.6% of the 1618 respondents were willing

to accept a higher entrance fee which was

71.08 RMB ($10.72) per visit, which was

higher than the current entrance fee (20 RMB,

$3.02). Likewise, Togridou, Hovardas, and

Pantis (2006) addressed the issue of determin-

ing national park fees for the National

Marine Park in Greece. They also examined

visitors’ actual and estimated consensus regard-

ing WTP. According to their findings, approxi-

mately 81% of 484 visitors agreed to pay a fee

ranging from E1 to E100, the WTP estimates

from the minimum (E1) to median (E5)

amounts would yield the lower and upper

limits of a source of revenue, these were

E300,000 and E1,400,000, the lower limit of

the aggregated value could cover maintenance

costs of the Protected Area Management

Body. While a study has focused on estimating

the value of public beach access and also com-

bined it with other attributes, e.g. water

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

quality, beach nourishment or beach erosion

protection. Shivlani, Letson, and Theis (2003)

use the CVM to estimate visitor preferences

for public beach amenities and beach restor-

ation in South Florida, the US Beach visitors

were willing to pay higher to support beach

nourishment ($1.69 per visit) when enhancing

nesting habitat for turtles ($2.12 per visit) was

combined as an attribute of beach nourishment.

Study Area

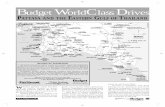

The KCMNP is the second largest island after

Phuket, and geographically situated at 11856′–

12816′N and 102825′ –102861′E in the Trat pro-

vince of Eastern Thailand, covering an area of

650 km2, of which 458 km2 consists of surface

water. The KCMNP is made up of more than

40 islands with approximately 5 km2 of coral

reef areas (Figure 1). It features fine beaches

with an abundance of natural resources and

plentiful marine life. There are many hills,

forests, waterfalls and streams, and the sur-

rounding ground water serves as an important

sourceof freshwater to thenation’s consumption

(Mu Ko Chang National Park, 2013). With its

long stretches of sandy beaches and bay areas,

the western coast side of Ko Chang has been

planned for the coast park tourism development

zone by the Thailand government. All the sur-

rounding islands of the KCMNP belong to tropi-

cal climatic destinations, which are dominated

by the southwestern monsoon: wet from May

to October, cool and dry in winter from Novem-

ber to February and hot and dry in summer from

March to April. The long and hot summer in Ko

Chang has an average temperature of 278C. The

KCMNP was designated as the National Marine

Park in 1982 by the Thailand government, and it

was assigned to the local government councils

for playing a role in administration (Mu Ko

Chang National Park, 2013).

In this study, we concentrate on the most

popular beach area which was selected for the

study, namely Haad Sai Khao (White Sand

Beach). At present, it can be accessed as a free

beach, of course, this beach park exhibits a dis-

tinctive style of tourism attraction to satisfy

various tourists’ preferences. Since 2002,

along with the increase in tourism demand,

White Sand Beach has generated a significant

amount of economic benefits each year for the

local economy. There are many small and

medium enterprises related to coastal rec-

reational businesses located on this land area

which can attract more than 2000 visitors

daily during the peak tourism season (Novem-

ber–April). According to the government stat-

istics in 2012, over 900,000 tourists visited the

KCMNP, which generated some $255 million

(Department of Tourism, Thailand, 2013).

There are three broad groups of beach visitors:

local residents, domestic visitors and foreign

tourists. However, tourism development in tro-

pical coastal areas frequently results in signifi-

cant environmental degradation over the

years, as a result of a rapid increase in tourism

demand and inadequate input to the park man-

agement (United Nations Environment Pro-

gramme, 2007).

A park entrance fee upon arrival has been

levied in most Thailand-protected areas. At the

time of this study (2013), tourists were regularly

charged to use public park amenities, varying

from 10 to 400 Thai Baht ($0.33–$13.34) per

person per visit (Department of National Parks,

Wildlife and Plant Conservation, 2012).

However, the KCMNP does not charge an

entrance fee on visitation except for entering

into the waterfall areas. International tourists

are usually charged 200 Thai Baht ($6.67) per

visitor, exchange rates of $1.00 ¼ 29.985 Thai

Baht at the time of the study (Bank of Thailand,

2013), while a local tourist pays one-fourth of

this price (Mu Ko Chang National Park, 2013).

4 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

The waterfall entry fees collected from tourists

are an important source of funds for environ-

mental protection. Annual revenue generated

by each park is returned to the government’s

coffers, which in turn provide an annual operat-

ing budget to the protected area based on land

area and local jurisdictional responsibility

rather than the park visitation rate. This results

in the problem whereby the KCMNP with the

heavy use of tourism resources does not obtain

sufficient public funds for park management

and investment (Adjaye & Tapsuwan, 2008).

Methodology

WTP Elicitation Methods

In order to elicit the mean WTP, we conducted

a dichotomous choice (DC) CVM or referen-

Figure 1 Map of the KCNMP.

(Source: Tourism Authority of Thailand, 2013).

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

dum questionnaire format to explore respon-

dents’ WTP based on the recommendations

of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration for the CVM (Arrow et al.,

1993). In their simplest form, bid amounts

are proposed to a respondent who either

accepts or rejects the amount. One advantage

of this elicitation method is a price taking

approach quite similar to a take-it-or-leave-it

market transaction (Xu, Loomis, Zhang, &

Hamamura, 2006). Compared with the

open-ended WTP questions, studies by

Hoehn and Randall (1987) and Carson,

Groves, and Machina (2000) indicated that

the DC approach is realistic and easier to

assess public preferences to the provision of

non-market goods. However, like other WTP

elicitation methods, the approach may be sen-

sitive to yea-saying problem in the double-

bounded dichotomous choice contingent

valuation method (DB DCCVM) (Kanninen

& Khawaja, 1995), whereby respondents

simply accept to pay a given monetary

amount, it has been subjected to a critical

drawback in bid thresholds, due to some evi-

dences that the responses to the initial bid

may be inconsistent with the responses to the

second bid, as a result, the latter reveals the

lower WTP (Hanemann, Loomis, & Kanni-

nen, 1991; Xu et al., 2006).

Adjaye and Tapsuwan (2008) argued that

the dichotomous choice contingent valuation

method (DCCVM) suffers from a number of

biases due to: (i) this method is based on

hypothetical rather than real choices and there-

fore subject to hypothetical bias from the over-

estimation; (ii) biases in the double-bounded

dichotomous choice method (the starting

point bias, shift effects, anchoring effects and

framing effects) are inherent and (iii) the “yea

saying” in the DB DCCVM may be motivated

by the social pressure faced by respondents

during the survey. CV researchers make

efforts to minimize sources of bias in the

method and to ensure that respondents take

the question seriously. Arrow et al. (1993) rec-

ommended that a CV instrument should

contain questions designed to detect the pres-

ence of the various biases. They also suggested

that the survey must include other questions to

verify whether respondents have done so. Even

though the starting bid was not correctly

specific, the higher bid provides effective insur-

ance against too low a choice of the initial price,

and the lower bid provides insurance against

too high a choice (Cooper, Hanemann, & Sign-

orello, 2002). This helps to considerably solve

the criticism in CVM studies, namely starting

point bias as well as anchoring effects and

yea-saying (Adjaye & Tapsuwan, 2008).

The SB format involves offering respondents

a single payment amount which they can

respond with either a “yes” or a “no” to the

offered bid. The probability (Pi) that a respon-

dent will answer a “yes” (Pyi ) or a “no” (Pn

i ) is

Pyi = 1 − G(BID; u), (1)

Pni = G(BID; u), (2)

where G(BID; u) is a statistical distribution

function of a parameter vector u and BID is a

bid offer, which can be estimated using the

logit regression model (Adjaye & Tapsuwan,

2008). The logit model can be expressed as

two forms, the log-logistic cumulative density

function

G(BID; u) = 1

[1 + expa−b(ln Bid)], (3)

and the logistic cumulative density function,

G(BID; u) = 1

[1 + expa−b(Bid)], (4)

6 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

where u ; (a,b), a and b are the intercepts and

the slope coefficients being valued, respectively.

G(BID;u) expresses the cumulative density func-

tion of the individual’s true maximum WTP.

Hanemann (1984) concluded that a utility max-

imization reflects the probability of a “yes”

response to the BID, when the BID is less than

or equal to maximum WTP or the probability

of a “no,” if the BID is greater than the

maximum WTP. According to Hanemann

et al. (1991), the log-likelihood function for all

respondents is

ln Ls(u) =∑N

i=1

{dyi ln Py

i (BIDi) + dni ln Pn

i (BIDi)},

=∑N

i=1

{dyi ln[1 − G(BIDi; u)]

+ dni ln G(BIDi; u)}, (5)

where dyi is unity if the ith response is “yes” and

zero otherwise, whereas, dni is unity if the ith

response is “no” and zero otherwise (Adjaye

& Tapsuwan, 2008).

Therefore, there are four possible outcomes:

(i) both responses are “yes” (Pyyi ); (ii) both

responses are “no” (Pnni ); (iii) a “yes” followed

by a “no” (Pyni ) and (iv) a “no” followed by a

“yes” (Pnyi ). For any given underlying WTP

distribution Gc(.), the likelihood of the prob-

ability that a respondent will respond these

outcomes is

Piyes

yes

( )= Pyy

i = 1 − Gc(BIDU), (6)

Pino

no

( )= Pnn

i = Gc(BIDL), (7)

Piyes

no

( )= Pyn

i =Gc(BIDU)−Gc − (BID), (8)

Pino

yes

( )= Pny

i =Gc(BID)−Gc − (BIDL). (9)

In this sense, the log-likelihood function for

the DB model is referred to by Hanemann

et al. (1991) as follows:

ln Ls(u) =∑N

i=1

[dyyi ln Pyy

i + dnni ln Pnn

i

+ dyni ln P

yn+dnyi

ln Pnyi

]

i ,

(10)

where dyyi , dnn

i , dyni and dny

i are binary-valued

indicator variables that are equal to one

when the two responses are one of the four

possible outcomes (Pyyi , Pnn

i , Pyni and Pny

i ), and

zero otherwise.

WTP Econometric Model

As the manner given by Hanemann (1984), we

assume that there exists a market participant

who has an indirect utility function V(Y,

BID, Q, S), in which it has some unobservable

components of the utility. The level of the indi-

vidual’s WTP depends on personal income

(Y ), the bid offer (BID), the quality of

natural sites (Q) and a vector of socioeco-

nomic characteristics (S). When offered a

given amount for a change in the quality of

natural sites (Q0 � Q1), the probability of

the respondent saying yes is

v(Y − BID, Q1, S) + 11

≥ v(Y − 0, Q0, S) + 10, (11)

where e0 and e1 are identically, independently

distributed (i.i.d.) random variables with zero

means. Assuming the individual’s response to

a binary question is a random variable with

some cumulative distribution function (c.d.f)

in the declared WTP. Therefore, the prob-

ability of a yes (Pyi ) that the individual will

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

accept the proposed bid can be written as

DV = [v(Y − BID, Q1, S) + 11

≥ v(Y − 0, Q0, S) + 10]. (12)

When faced with a binary dependent vari-

able and that variable is a qualitative choice

behavior, the logit model is then estimated

the probability function by maximum likeli-

hood (ML). Bengochea-Morancho, Fuertes-

Eugenio, and Saz-Salazar (2005) indicated

that the ML estimator has better properties

than others when the dependent variable is

categorical. The probability that an individual

will say a “yes” for a bid offer in the SB elicita-

tion format can be modeled in log-logistic

form as

Pyi =FhDv= (1+exp−Dv)−1

Pyi

1

1+exp{− (a−b1, lnBID+b2 lnQ+b3 lnS)}

(13)

and the double-bounded (DB) elicitation

format can be formulated in the logistic form

as

Pyi =FhDv= (1+exp−Dv)−1

Pyi =

1

1+exp{(−a−b1,BID+b2Q+b3S)}

(14)

where Fh is a cumulative distribution func-

tion, a is a constant and b is the coefficient

of a bid offer (BID), respectively.

Following Hanemann (1984), the con-

strained mean WTP (WTPmean) for the SB

and DB DCCVM were estimated in the next

expressions:

The single − bounded log − logistic model:

WTPmean = exp−a∗/b x(p/b)

( sin (p/b)),

(15)

The double−bounded logistic model: WTPmean

= ln(1+expa∗)

b,

(16)

where a∗ belongs to the adjusted intercept and

b denotes the slope regression coefficient value

for the proposed bid amount (Adjaye & Tap-

suwan, 2008).

Model Specification

As usual, the WTP amounts offered are

hypothesized as dependent variables, which

are influenced by a number of independent

variables, including socioeconomic character-

istics, individuals’ preferences and knowledge

about environmental issues. The WTP func-

tion can then be derived as the following:

Yi = f (BID, GEN, AGE, HH, EDU, INCOME,

CROWDED, REEFS, BEACHQ,

WATERQ, OVERALLQ, STILL),

where Yi represents the respondent’s WTP in a

binary number, BID is a bid offer. The socioe-

conomic variables include the visitor’s gender

(GEN), age (AGE), household size (HH), edu-

cational attainment (EDU) and personal

income (INCOME). Furthermore, the model

also incorporates variables which can reflect

the site quality characteristics. Those variables

are perceive crowding (CROWDED), abun-

8 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

dant of coral reefs (REEFS), beach quality

(BEACHQ), bathing water quality

(WATERQ), the surrounding environment

(OVERALLQ) and visitor’s intention toward

his or her future visit to the site (STILL).

Data Collection

Beach visitors along the White Sand beach

shoreline in the KCNMP were interviewed in

person during the tourism season from

January to March in 2013. The in-person

interviews are strongly recommended by

Mitchell and Carson (1995) and Xu et al.

(2006) because this method could ensure the

quality and accuracy from a survey of the

respondents. To decrease the sample error, a

stratified random sampling was adopted in

the formal survey (Wang & Jia, 2012).

According to the park visitation statistics

from 2003 to 2012 (Department of Tourism,

Thailand, 2013), the ratio of domestic visitors

(including the number of local visitors) to

foreign visitors was approximately 63%:

37%. Every 10th visitor entering the survey

locations was intercepted for interview. A

total of 409 questionnaires were selected for

the interviewing process by trained interview

specialists. Therefore, the sample comprised

256 Thai visitors and 153 foreign visitors.

The questionnaire was designed with

support from the park management personnel

who are familiar with the beach uses and man-

agement. A focus group discussion was held

with a total of 60 individuals’ participation

for pretest conducted in December 2012 in

order to detect sources of potential bias and

identify misunderstand wording in the ques-

tionnaire (Arrow et al., 1993; Huhtala, 2004;

Nunes, 2002). Four interviewers were

involved, three of them college degree

holders, and one researcher participated in

the full CV survey. For this purpose, a two-

day training was held to ensure that the inter-

viewers could operate live interviews and fill in

the survey form correctly. Thai and English

used in the survey were administered in the

original version. To minimize significant

changes in the meaning, the Thai version was

independently translated into English by a

bilingual translator whose native tongue was

Thai, and a native English speaker who was

also fluent in Thai then retranslated the Thai

version into English. After comparing the

two versions, the different points were ident-

ified and resolved by consensus (Leelapattana,

Keorochana, Johnson, Wajanavisit, & Laoha-

charoensombat, 2011). During the survey

period, only the foreign visitors who could

speak English were interviewed by an English

degree holder.

Before the interview, the respondents were

clearly explained the CV survey’s content

and each specific question. In case that the

respondents misunderstood some questions,

the interviewees made clarification at the

scene. Only adults were required (aged 18 or

above), in the case of family groups, the head

of the family was invited for the interview.

During the sampling period, the interviewer

surveyed three times a day, namely at 10:00,

14:00 and 16:00, when visitor numbers

reached the site maximum in order to catch

more beach visitors. Each interview took

about 30 minutes, once the visitors were

recruited into the study, a small gift as a

token of appreciation was presented.

Survey Instrument

The survey questionnaire comprised four sec-

tions. The first section dealt with problem

statements and the purpose of the research,

the respondents were explained by talking

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

about the status of the beach park environ-

ment and ecological system and emphasized

the importance of the environmental protec-

tion in the KCMPN. To reduce rejection

rates and obtain accurate information, the

respondents were informed that the data

from the survey would be used to estimate

economic value of recreational resources for

academic research (Lee & Han, 2002).

The second section consisted of visitor

activities, travel expenses, time spent at the

park and visitors’ preferences over the site

attributes. In a measurement of visitors’ pre-

ferences, the respondents were asked to scale

a score for five variables, those variables

included crowding condition, coral reef,

beach quality, bathing water quality and the

surrounding environment using the nine-

point Likert scale method. The third part con-

tained the questions on the WTP estimates and

the reasons for a negative WTP.

Based on the pretest, we adopted both

payment card and open-ended questions to

test the focus group conducted in order to

make the questionnaire effective and to

verify the starting bid used in the formal

survey (Cooper, 1993). After revising the ques-

tionnaire, the question sequence was restruc-

tured, the wording of the questionnaire was

refined to properly improve clarity between

the respondents and the interviewers; and the

payment vehicle was chosen to be an entrance

fee. This is due to the fact that tourists in the

protected areas are familiar with park

entrance fees (Lee, 1997). As noted by

Barral, Stern, and Bhattarai (2008), the

entrance fee is the realistic and acceptable

mechanism for users of non-market resource

services. Mitchell and Carson (1989) stated

that CV questions related to personal status

should be placed at the end of the survey. In

the final section, socioeconomic data about

respondents, including gender, age, monthly

income, level of education, family size, as

well as country of residence were collected.

In practice, a CVM hypothetical scenario

and the SB and DB DCCVM questions were

used to elicit the WTP amount by asking

respondents to state the maximum amount

they would be willing to pay as an entrance

fee for beach resource protection. To this

respect, the hypothetical market scenario was

designed to show the status quo (current

beach resource conditions) and after charging

visitors for conservation (improved coastal

resource quality), the hypothetical scenario

was used to familiarize the respondents.

Since the on-site survey was conducted where

the respondents were sampled on the beach,

they were able to notice the current state of

beach resource degradation. Therefore, the

hypothetical scenario asked in the WTP ques-

tion was easily understood. Concerning ques-

tions in the DB approach, the respondent

was asked whether he would be willing to

pay an initial bid at random, if he said “yes”

to the first bid amount (e.g. $10), he was

then offered the second bid at the next higher

amount (the second bid equaled to $20); if

the initial response was ‘no’ to $10, he was

proposed a lower amount (i.e. $5). However,

if he said ‘no’ to both the initial and the

lower bids, the reasons of a negative WTP

were enquired. With regard to a list of bid

prices, the initial bid levels used in the SB ques-

tions were randomly chosen with one of the

five bid amounts ($3, $5, $10, $20 and $30),

followed by the second bid offered in the DB

format, that was half or double of the initial

bid, accordingly. As a result, five sets of the

DB questions were ($3, $1.5 and $7), ($5,

$2.5 and $10), ($10, $5 and $20), ($20, $10

and $40) and ($30, $15 and $60), respectively,

(Barral et al., 2008; Eagles, McCool, &

Haynes, 2002). The full CV questionnaire is

presented in the appendix.

10 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

Data Description

As regards the definition of visitors, domestic

visitors mean the national visitors who tra-

veled and stayed at the site at least one night

and less than one year, including the day

visitor who spent less than one day at the

park and went home the same day. A foreign

tourist is a person visiting the KCMNP on a

foreign passport for leisure, entertainment

and other purposes and staying at least one

day. Descriptive statistics for those variables

used in the regression analysis are summarized

in Table 1.

Most long-stay foreign visitors came from

European countries, which account for 85%.

A long-stay visitor means that a visitor will

stay at the destination area for at least one

month of time. The respondents’ sex ratio is

about 65:35 between male and female; Thai

and foreign visitors are, respectively,

accounted for 67% and 33%. The dominant

age group of Thai visitors is about 21–30

years (48.05%), followed by 31–40 years

(35.55%). Most foreign respondents are in

the age of 40–50 years (57.52%). The

majority of Thai respondents had a high

school education (42.19%), followed by a

college degree (34.77%), with an average

household size of 3.97. Of the foreign respon-

dents, 32.03% had completed high school and

24.18% had bachelor degrees as their highest

level of educational attainment. The personal

annual income of Thai visitors is relatively

lower with the average being $11,633, about

one-third of the income earned by foreign visi-

tors. Domestic visitors of 69.14% earn less

than $10,000 in income per year, followed

by $10,000–$19,999 (27.34%). The lower

level of annual income is simply due to a

high proportion of visitors who are students

who obviously make less money or no

income. By contrast, foreign respondents

earn more than $60,000 per year of income

(50.33%), followed by $30,000–$39,999

income groups (19.61%). About 32% of the

foreigners are employed in private sectors (fol-

lowed by government officials (22.22%) and

self-employed (18.30%). Among Thai visitors,

46.09% classify themselves as firm employees,

and 22.27% of them are university students.

In the CVM questions, respondents were

asked to scale a variable from 1 to 9 about

their perception of the beach’s overall

current conditions. About 76% of the beach

visitors felt somewhat crowded at White

Sand beach (scores 4–5). Visitors also

expressed that the coastal beach quality has a

strong effect on their decision of visiting the

beach although in general the beach visitors

are satisfied with the beach conditions (with

the average score of 7–8).

Table 2 reports the percentage of responses

to the CVM questions on WTP for the beach

resource protection; as one would expect, the

probability of a “yes” to the initial bid

decreased when the bid level increased, and

the reverse was true for the probability of a

“no,” which is supportive by the economic

theory of demand (Chen & Jim, 2008;

Kotchen, Kallaos, Wheeler, Wong, &

Zahller, 2009; Wang & Jia, 2012).

In the survey response rate, 78.5% of

respondents would accept an entrance fee for

the beach park preservation, whereas the

“zero” WTP was chosen by 88 respondents

(21.5%). The reasons behind a negative WTP

were given by the protestor: (i) 37 of the pro-

testors were unwilling to pay because they

could not afford to pay more travel expenses;

(ii) 31 believed that it was the government’s

responsibility and; (iii) 20 stated that they

were satisfied with the current beach con-

ditions. Following standard practice in the

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

Table 1 Variable Definitions and Descriptive Statistics

Variables Label

Thai visitors Foreign visitors

Mean (std. dev) Mean (std. dev)

WTP Dependent variable, takes the value 1, if the respondent accepts

the offered bid amount, 0 if they refuse to pay

lnBID/BID Hypothetical amounts of the offered bid

Socioeconomic variable

GEN Gender, 1 if the respondent is male, 0 otherwise 0.65 (0.479) 0.67 (0.474)

AGE Age in year 34.46 (9.788) 43.46 (14.990)

HH Household size 3.97 (1.942) 2.64 (1.206)

EDU Level of education (scale variable: 1–5) 1.60 (1.199) 1.69 (1.622)

INCOME Average annual income before tax in ’000 ($) 11.633 (12.996) 36.346 (23.778)

Perception about quality of the current beach conditions

CROWDED Crowding condition (scale variable: 1–9, from low to high satisfaction) 4.85 (1.975) 5.17 (1.937)

REEFS Coral reef condition (scale variable: 1–9, from low to high satisfaction) 1.67 (2.890) 2.23 (3.121)

BEACHQ Beach quality (scale variable: 1–9, from low to high satisfaction) 7.31 (1.307) 7.31 (1.351)

WATERQ Bathing water quality (scale variable: 1–9, from low to high satisfaction) 7.47 (1.308) 7.04 (1.869)

OVERALLQ The surrounding environment (scale variable: 1–9, from low to high

satisfaction)

7.02 (1.496) 7.04 (1.566)

STILL The intention of visiting the site in future, 1 if the respondent will revisit

the site, 0 otherwise

0.89 (0.319) 0.87 (0.336)

Notes: (i) Numbers in parentheses refer to standard errors; (ii) in this CV study, it is important to note that ln BiD is the bid offer in the SB questions and BID variablerepresents the bid offer in the DB format.

12

Sunid

aP

iriyapad

aan

dE

rda

Wan

g

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

CVM analyses, the respondents were asked to

screen the protest zero bidder; this was to

ensure that the respondents who rejected the

proposed entrance fee were not influenced by

a result of protest beliefs (Cho, Newman, &

Bowker, 2005). Thus, these protest responses

were deleted from the CVM sample because

it was assumed that the protest responses can

introduce bias for the valuation (Garcıa-Llor-

ente, Martın-Lopez, & Montes, 2011). The

respondents who answered reason (ii) were

classified as the protest bidders who objected

to an aspect of the CV survey or the WTP

(Adjaye & Tapsuwan, 2008; Cho et al.,

2005). The final sample used in the model

was 378 respondents, which consisted of 236

Thai visitors and 142 foreign visitors.

Empirical Results

In this study, we were concerned with measur-

ing the WTP estimates of Thai and foreign visi-

tors, as well as comparing the results of the

logit models in the SB and DB approaches.

The ML estimates in the log-logistic of the

SB model and the linear DB functional forms

of WTP values are shown in Table 3. The

correlation test was conducted by using the

stepwise regression procedure in order to

select variables into the model. From the

analysis, all socioeconomic factors used of

the respondents were not highly correlated

with the one another.

The coefficients of the bid offer variable

(lnBID and BID) are negative and statistically

significant (p , 0.01) across all models,

which are consistent with the previous CVM

literatures studied by Saengsupavanich et al.

(2008) and Kotchen et al. (2009). This indi-

cates that the probability of a “yes” response

decreases as the bid price offered increases

and vice versa. Similarly, the coefficient of

the gender variable is negative and significant

(p , 0.05) across all models, which means

females are more likely to pay an entrance

fee for beach resource conservation (Bord &

O’Connor, 1997; Brown & Taylor, 2000).

The age variable has positive coefficients that

are statistically significant across Thai

samples, which means that in this particular

sample the older visitors are relatively more

acceptable to pay the bid offered than the

younger ones. By contrast, the household size

variable is estimated negative and significant

(p , 0.05) in all models, this suggests that

Table 2 Distribution of WTP response in the DB DCCVM

Initial bid Yes/yes (%) Yes/no (%) No/yes (%) No/no (%)

$3 9.02 11.65 3.88 2.36

$5 4.38 8.53 4.83 5.37

$10 3.53 5.21 3.25 8.69

$20 1.94 2.13 1.63 7.55

$30 0.89 1.54 0.65 12.97

Total 19.76 29.06 14.24 36.94

Notes: (i) The five entrance fees were distributed randomly among respondents; (ii) the responses to the initial and thefollow-up bids are recorded as Y for a “yes” and N for a “no,” the proposed bid levels are listed above.

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 13

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

Table 3 Maximum-Likelihood Estimates from the SB and DB DCCVM

Variable

SB model DB model

Thai visitors Foreign visitors Thai visitors Foreign visitors

CONS 0.1848∗ (3.37) 21.2666∗∗ (22.16) 0.2357∗ (2.89) 0.8269∗ (2.93)

ln BID 20.9781∗ (24.12) 20.9466∗ (23.18) – –

BID – – 20.3353∗ (23.86) 20.1284∗ (22.93)

GEN 20.8328∗ (23.78) 20.0994∗ (22.53) 20.0683∗∗ (22.09) 20.2145∗∗ (22.12)

AGE 0.0094∗ (4.58) 0.0363 (1.45) 0.0087∗ (4.41) 0.0496 (1.53)

HH 20.0238∗∗ (22.36) 20.1836∗ (25.19) 20.022∗∗ (22.36) 20.1991∗ (25.04)

EDU 0.0058 (1.08) 0.3232∗ (3.33) 0.1668 (1.17) 0.2998∗ (3.14)

INCOME 0.0683∗∗ (2.56) 0.0835 (0.73) 0.0756∗∗ (2.39) 0.0965 (1.18)

CROWDED 20.0075 (21.36) 20.0286 (20.93) 20.0093 (21.46) 20.0202 (21.09)

REEFS 20.0489 (21.37) 20.1225∗ (25.49) 20.0454 (21.48) 20.1014∗ (25.33)

BEACHQ 0.1359∗∗ (2.11) 0.1368 (1.26) 0.0899∗∗ (2.54) 0.1426 (1.34)

WATERQ 0.1594 (1.56) 0.1161∗ (3.34) 0.1212 (1.42) 0.1295∗ (3.29)

OVERALLQ 0.0236 (0.96) 0.1767 (1.59) 0.0199 (1.19) 0.2855 (1.36)

STILL 0.4895∗ (4.45) 0.5232∗ (3.34) 0.4553∗ (4.35) 0.3896∗ (3.16)

N 236 142 236 142

McFadden R2 0.457 0.483 – –

FCCC – – 0.492 0.563

X2 215.79∗ 185.902∗ 212.95∗ 181.853∗

Log likelihood 2584.543 2274.235 2986.22 2576.61

Notes: T-ratios are in parentheses.∗Statistical significance at the 1% level.∗∗Statistical significance at the 5% level.

14

Sunid

aP

iriyapad

aan

dE

rda

Wan

g

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

the respondents who have a larger family size

are less likely to pay the entrance fee. The edu-

cational level is another variable found to be

positively influenced by the WTP amount

pledged across all Thai visitor models, this

may imply that those well-educated respon-

dents are more likely to pay an increased

WTP amount (Hanley, Colombo, Kristrom,

& Watson, 2009). Similarly, the income vari-

able shows a significant positive influence on

the possibility to pay across foreign visitor

models, indicating that richer respondents

would notably raise WTP.

The SB and DB logit models also accom-

pany environmental variables which can

reflect the site quality attributes, those

environmental factors such as crowding con-

dition and coral reefs have negative effects

on the WTP across all models, implying that

the respondents who felt crowded by the

number of tourists encountered at the study

site and the coral reefs are in danger are

willing to pay for improving natural con-

ditions. However, when the dissatisfaction

reached a certain level, the respondents are

no longer willing to afford an entrance fee

for protecting beach park environment

(Wang and Jia, 2012). On the contrary, we

found the positive effects in beach quality,

bathing water quality and the surrounding

environment coefficients across the SB and

DB models, this may be explained that the

respondents who perceived beach park degra-

dation. They are more likely to pay for the

beach conservation values. The sign of the

mixed effects may depend on the site charac-

teristics and the physically degraded period.

Perhaps more surprising is the positive and

statistically significant coefficient (p , 0.01)

on the intention of visiting the site in future

variable, which implies that the visitors who

have an intention to visit the beach park in

the next time are more likely to respond “a

yes” for the proposed bid if they feel satisfied

with the current beach conditions.

A goodness-of-fit measure of McFadden’s

pseudo R2 was tested, the larger McFadden’s

pseudo R2 values of the log-logistic SB

models demonstrate the explanatory power

of the model (between 46% and 48%),

which is relatively high for cross-sectional

data (Christie et al., 2004). In addition, the

chi-squared tests indicated that all the SB and

DB logit models are statistically significant (p

, 0.01). Kanninen and Khawaja (1995) noted

that a standard goodness-of-fit measure of

McFadden’s pseudo R2 could not be calcu-

lated for the DB logit model. This arises

because the restricted log of the likelihood

function is undefined. As a result, they rec-

Table 4 Estimates of Mean WTP from the SB and DB DCCVM

Mean WTP (US$) Thai visitors (N ¼ 236) Foreign visitors (N ¼ 142)

SB $12.01 ($7.84, $33.85) $25.33 ($14.66, $54.37)

Lower and upper 95% confidence interval

DB $7.27 ($2.68, $14.56) $14.47 ($5.18, $30.92)

Lower and upper 95% confidence interval

Note: Bootstrap method is reported in the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals around mean WTPestimates in parentheses.

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 15

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

ommended an alternative measure which is the

fully correctly classified cases (FCCC) method

to evaluate the goodness-of-fit for the DB

model. McCluskey, Durham, and Horn

(2009) defined that the FCCC approach is

used to calculate the percentage of respon-

dents that the model correctly classified, each

observation into the four categories (yes/yes,

no/no, yes/no and no/yes).

Table 4 presents the estimation results of the

mean WTP for both SB and DB elicitation

methods that were calculated by the formulas

illustrated in eqs. (15) and (16). The mean

WTP for a Thai visitor using the SB method

is $12.01 per adult per visit, while that for

the mean WTP of a foreign visitor is twice as

high as the Thai visitor’s WTP as well as the

estimated WTP results in the DB model. More-

over, we derived the 95% confidence intervals

using a bootstrapping approach for calculat-

ing confidence intervals of elasticities. Using

a t-test of the differences between the lower

and upper limits of the 95% confidence inter-

vals suggests that there is no statistically sig-

nificant difference between Thai and foreign

visitors (calculated t-test is 7.195).

Compared with the previous CVM studies,

these WTP values lie within the range of valua-

tions estimated from coastal beach resources.

For example, Walpole, Goodwin, and Ward

(2001) employed an upper and lower

bounded DCCVM to examine the effect of

hypothetical rises in the entrance fee on visita-

tion at Komodo National Park, Indonesia. The

mean WTP estimate was $11.70, which is a

more closely the result of the mean WTP of a

Thai visitor’s WTP ($12.01) in the SB

approach, as well as the CVM study by

Wang and Jia (2012), they used the multiple

bounded discrete choice elicitation method to

estimate the WTP a higher entrance fee for

biodiversity conservation and environmental

protection at the Dalai Lake Protected Area

in China. The results found that the tourists’

mean WTP ranged between 75.05 RMB and

85.17 RMB (approximately $10.32–$12.35)

per adult per visit.

A simple way to calculate the aggregate

benefit of beach resource protection is to mul-

tiply the estimated WTP per trip resulted from

the DB model as a lower bound estimate, and

that of the SB model as an upper bound esti-

mate by the average number of park visitors

over 10 years. Based on 2003–2012, park vis-

itation figures of Thai and foreign visitors were

356,789 and 177,360, respectively (Depart-

ment of Tourism, Thailand, 2013) and the cor-

responded sample average number of trips

were 3.33 and 1.76, respectively. Thus, the

total annual trips are estimated to be

1,188,107 of Thai visitors and 312,154 of

foreigners, respectively. These respective

tourism statistics are then multiplied by the

WTP per-visitor-trip of $7.27 and $14.47,

respectively, for Thai and foreign visitors

under the DB method, which results in a

lower bound estimate of $8.64 million and

$4.52 million per annum. Similarly, using the

SB model results of the mean WTP to get an

upper bound estimate of $12.01 and $25.33

of per-visitor-trip, we obtain an upper bound

estimate of $14.27 million and $7.91 million

per annum, respectively, in aggregate. These

can be converted to the lower and upper

bounds of an aggregate WTP ranging from

$13.16 million to $22.18 million. Assuming

that 78.5% of the respondents would be

willing to pay an entrance fee for coastal

resource preservation, the aggregate WTP

benefits are worth between $10.33 million

and $17.41 million per year. These substantial

benefits suggest that preserving beach

resources can generate an extraordinary

amount of economic benefits.

16 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

Summary and Conclusions

This study values the WTP an entrance fee for

beach resource protection along the White

Sand Beach coastline in the KCMNP. In the

process, the CVM method is utilized to

measure the WTP estimates in terms of per-

visitor-trip. Specifically, both SB and DB DC

CVMs are used in estimating the WTP based

on the field survey data. The results show

that the mean WTP per beach visitor trip is

$12.01 and $7.27 for Thai visitors under the

SB and the DB models, respectively; $25.33

and $14.47 for foreign visitors, respectively,

under the same models.

The results also reveal that the variables of a

bid offer, gender, household size and the inten-

tion of visiting the site in future are the most sig-

nificant predictors of the beach visitors’ WTP

(p ≤ 0.05), regardless of which model is used

in the estimation. Based on the SB and DB esti-

mation results, 73.5% of the respondents

accepted WTP an entrance fee for coastal

beach protection, we found that the lower

and upper bounds of annual aggregate WTP

range from $10.33 million to $17.41 million

per year. According to the park management

official, the park’s operating cost in 2012 was

$287,500 (Mu Ko Chang National Park,

2013), which is much smaller than the value

of estimated beach park conservation. Based

on our findings, the majority of the respondents

(87%) have intention to visit the KCMNP

again in the future. The park management

can certainly raise the park entrance fees at

both park gate spots and waterfall areas. If

the entrance fee was raised to $7.27 for Thai

visitors and $14.47 for foreign visitors, as the

mean WTP obtained in the DB model (Adjaye

& Tapsuwan, 2008), the KCMNP would

have possible revenues of $5.16 million per

year. Because of the park authorities’ limited

financial resources, entrance fees are an impor-

tant vehicle for natural site protection, even

though collecting entrance fees may reduce

the number of tourists visiting the park,

which could mitigate overcrowding and

beach resource disturbance (Davis & Tisdell,

1995), while preserving positive WTP and

enhancing the tourists’ experience. However,

if the visitors pay an entrance fee to the site,

given that domestic visitors have a lower

WTP, they might reduce their visits in the

future, inducing a larger foreign consumption.

This might create social problems since a

national resource would be mainly consumed

by international visitors.

Visitors’ survey responses and WTP value

estimation of the beach resource protection

provide important information for improving

the park management. With regard to the visi-

tors’ attitudes toward park management, two

points deserve to be mentioned. One is crowd-

ing problem on the site, which perhaps reflects

the over capacity use of the beach resources.

Therefore, the park management has to pay

attention to the number of visitors arrived,

especially during the peak tourism seasons.

Some actions must be taken to cut the

number of visitors to enter the sites per day

or even in a specific time period during the

day. Several measures could be adopted to

limit the beaches in their carrying capacity

use, including visitor diversion scheme,

raising entrance price command control, etc.

The other one is that based on the survey

responses, most visitors have shown their con-

cerns over the beaches’ environmental pol-

lution, which may create serious negative

effect on the travelers’ repeated visit(s), the

level of their WTP, and certainly their length

of stay, thus reducing the park’s revenue

potential in the future. Therefore, both Thai

central and local governments should input

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 17

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

more resources to environmental protection

for the beaches to ensure no further deterio-

ration of beach amenity. On the other hand,

it is recommended that the park authority

should take some proactive measures in

dealing with environmental protection. In an

operational level, this may include taking

care of the public toilets, showers, water

sources, trash cans, parking lots, walk path-

ways, information signs and local facilities

for convenience. Understand that doing an

adequate management work requires a signifi-

cant amount of financial support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China Grant

No. [70871014] and No. [71271040], and

the Institution of High Education Doctor

Subject Special Research Fund, Ministry of

Education, the People’s Republic of China.

References

Adjaye, J. A., & Tapsuwan, S. (2008). A contingent valua-

tion study of scuba diving benefits: Case study in Mu Ko

Similan Marine National Park, Thailand. Tourism

Management, 29(6), 1122–1130. doi:10.1016/j.

tourman.2008.02.005

Ajzen, I., Brown, T. C., & Carvajal, F. (2004). Explaining

the discrepancy between intentions and actions: The

case of hypothetical bias in contingent valuation. Per-

sonality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(9), 1108–

1121. doi:10.1177/0146167204264079

Arrow, K., Solow, R., Portney, P., Leamer, E., Radner, R.,

& Schuman, H. (1993). Report of the national oceanic

and atmospheric administration panel on contingent

valuation (vol. 58, pp. 4602–4614). US Department

of Commerce, Washington, DC: Federal Register.

Bank of Thailand. (2013). Discount and foreign exchange

rates 2013. Retrieved from http://www.bot.or.th/Thai/

Statistics/FinancialMarkets/ExchangeRate/_layouts/Appli

cation/ExchangeRate/ExchangeRate.aspx

Barral, N., Stern, M. J., & Bhattarai, R. (2008). Contingent

valuation of ecotourism in Annapura Conservation Area,

Nepal: Implications for suistanable park finance and

local development. Ecological Economics, 66(2–3),

218–227. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.02.004

Bengochea-Morancho, A., Fuertes-Eugenio, A. M., & Saz-

Salazar, S. (2005). A comparison of empirical models

used to infer the willingness to pay in contingent valua-

tion. Empirical Economics, 30(1), 235–244. doi:10.

1007/s00181-005-0236-x

Birdir, S., Unal, O., Birdir, K., & Williams, A. T. (2013).

Willingness to pay as an economic instrument for

coastal tourism management: Cases from Mersin,

Turkey. Tourism Management, 36, 279–283.

Bord, R. J., & O’Connor, R. E. (1997). The gender gap in

environmental attitudes: The case of perceived vulner-

ability to risk. Social Science Quarterly, 78(4), 830–840.

Borg, N. B., & Scarpa, R. (2010). Valuing quality changes

in Caribbean coastal waters for heterogeneous beach

visitors. Ecological Economics, 69(5), 1124–1139.

doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.12.007

Brown, K., & Taylor, L. (2000). Do as you say, say as you

do: Evidence on gender differences in actual and stated

contributions to public goods. Journal of Economic Be-

havior & Organization, 43(1), 127–139. doi:10.1016/

S0167-2681(00)00113-X

Carson, R., Groves, T., & Machina, M. (2000). Incentives

and informational properties of preference questions.

Department of Economics, University of California-

San Diego, La Jolla, CA.

Carson, R. T. (2012). Contingent valuation: A practical

alternative when prices aren’t available. Journal of

Economics Perspectives, 26, 27–42.

Chen, W. Y., & Jim, C. Y. (2008). Costebenefit analysis of

the leisure value of urban greening in the new Chinese

city of Zhuhai. Cities, 25(5), 298–309.

Cho, S. H., Newman, D. H., & Bowker, J. M. (2005).

Measuring rural homeowners’ willingness to pay for

land conservation easements. Forest Policy and Econ-

omics, 7(5), 757–770. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2005.03.007

Christie, M., Hanley, N., Warren, J., Hyde, T., Murphy,

K., & Wright, R. (2004). A valuation of biodiversity

in the UK using choice experiments and contingent

valuation. Paper presented at the envecon 2004:

Applied Environmental Economics Conference, UK

Network of Environmental Economists, London.

Collins, J. P., & Vossler, C. (2009). Incentive compatibil-

ity tests of choice experiment value elicitation questions.

Journal of Environmental Economics and Management,

58(2), 226–235. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2009.04.004

18 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

Cooper, J. C. (1993). Optimal bid selection for dichoto-

mous choice contingent valuation surveys. Journal of

Environmental Economics and Management, 24(1),

25–40. doi:10.1006/jeem.1993.1002

Cooper, J. C., Hanemann, M., & Signorello, G. (2002).

One-and-one-half-bound dichotomous choice contin-

gent valuation. Review of Economics and Statistics,

84(4), 742–750. doi:10.1162/003465302760556549

Davis, D., & Tisdell, C. (1995). Recreational scuba diving

and carrying capacity in marine protected areas. Ocean

& Coastal Management, 26(1), 19–40. doi:10.1016/

0964-5691(95)00004-l

Department of Mineral Resources, Thailand. (2013).

Geology for coastal management of Thailand. Retrieved

from http://www.dmr.go.th/ewtadmin/ewt/dmr_web/

main.php?filename¼geo_coastal___EN

Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conser-

vation. (2012). National park fees, reservations, and

regulations. Retrieved from http://www.dnp8.com/

dnp8/index.php?option¼com_content&view¼article&

id¼97&Itemid¼77

Department of Tourism, Thailand. (2013). Tourism stat-

istics. Retrieved September 30, 2013, from http://

www.tourism.go.th

Eagles, P. F. J., McCool, S. F., & Haynes, C. D. (2002).

Sustainable tourism in protected areas: Guidelines for

planning and management. Cambridge: IUCN.

Garcıa-Llorente, M., Martın-Lopez, B., & Montes, C.

(2011). Exploring the motivations of protesters in con-

tingent valuation: Insights for conservation policies.

Environmental Science & Policy, 14(1), 76–88.

doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2010.11.004

Hanemann, M. (1984). Welfare evaluations in contingent

valuation experiments with discrete responses. Ameri-

can Journal of Agricultural Economics, 66(3),

332–341. doi:10.2307/1240800

Hanemann, M., Loomis, J., & Kanninen, B. (1991). Stat-

istical efficiency of double-bounded dichotomous choice

contingent valuation. American Journal of Agricultural

Economics, 73(4), 1255–1263. doi:dx.doi.org/10.

2307/1242453

Hanley, N., Colombo, S., Kristrom, B., & Watson, F.

(2009). Accounting for negative, zero and positive will-

ingness to pay for landscape change in a national park.

Journal of Agricultural Economics, 60(1), 1–16. doi:10.

1111/j.1477-9552.2008.00180

Hausman, J. (2012). Contingent valuation: From dubious

to hopeless. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(4),

43–56. doi:10.1257/jep.26.4.43

Hoehn, J., & Randall, A. (1987). A satisfactory benefit–

cost indicator from contingent valuation. Journal of

Environmental Economics and Management, 14(3),

226–247. doi:10.1016/0095-0696(87)90018-0

Howarth, B. R., & Farber, S. (2002). Accounting for the

value of ecosystem services. Ecological Economics,

41(3), 421–429. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00091-5

Huhtala, A. (2004). What price recreation in Finland? A

contingent valuation study of non-market benefits of

public outdoor recreation areas. Journal of Leisure

Research, 36(1), 23–44.

Kanninen, B. J., & Khawaja, M. S. (1995). Measuring

goodness of fit for the double-bounded logit model.

American Agricultural Economics Association, 77(4),

885–890. doi:10.2307/1243811

Kotchen, M., Kallaos, J., Wheeler, K., Wong, C., &

Zahller, M. (2009). Pharmaceuticals in wastewater: Be-

havior, preferences, and willingness to pay for a disposal

program. Journal of Environmental Management,

90(3), 1476–1482. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.10.

002

Koutrakisa, E., Sapounidisa, A., Marzettib, S., Marinc, V.,

Rousseld, S., Martinof, S., . . . , Malvarezh, C. G.

(2011). ICZM and coastal defence perception by

beach users: Lessons from the Mediterranean coastal

area. Ocean & Coastal Management, 54(11), 821–

830. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.09.004

Lee, C., & Han, S. (2002). Estimating the use and preser-

vation values of national parks’ tourism resources using

a contingent valuation method. Tourism Management,

23(5), 531–540. doi:10.1016/s0261-5177

Lee, C. K. (1997). Valuation of nature-based tourism

resources using dichotomous choice contingent valua-

tion method. Tourism Management, 18(8), 587–591.

doi:10.1016/s0261-5177(97)00076-9

Leelapattana, P., Keorochana, G., Johnson, J., Wajanavi-

sit, W., & Laohacharoensombat, W. (2011). Reliability

and validity of an adapted Thai version of the Scoliosis

Research Society-22 questionnaire. Journal of Chil-

dren’s Orthopaedics, 5(1), 35–40. doi:10.1007/

s11832-010-0312-4

Logar, I., & Van den Bergh, J. C. J. M. (2012). Respon-

dent uncertainty in contingent valuation of preventing

beach erosion: An analysis with a polychotomous

choice question. Journal of Environmental Manage-

ment, 113, 184–193. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.08.

012

McCluskey, J. J., Durham, C. A., & Horn, B. P. (2009).

Consumer preferences for socially responsible pro-

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 19

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

duction attributes across food products. Agricultural

and Resource Economics Review, 38(3), 345–356.

Mitchell, R. C., & Carson, R. T. (1989). Using surveys to

value public goods: The contingent valuation method.

Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

Mitchell, R. C., & Carson, R. T. (1995). Current issues in

the design, administration, and analysis of contingent

valuation surveys. In P. O. Johansson, B. Kristrom &

K. G. Maler (Eds.), Current issues in environmental

economics (pp. 10–34). Manchester: Manchester Uni-

versity Press.

Mu Ko Chang National Park. (2013). General infor-

mation. Retrieved from http://www.dnp.go.th/

parkreserve/asp/style1/default.asp?npid¼211&lg¼2

Nunes, P. A. L. D. (2002). The contingent valuation of

natural parks: Assessing the Warmglow propensity

factor. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Park, T., Bowker, J. M., & Leeworthy, V. R. (2002).

Valuing snorkeling visits to the Florida Keys with

stated and revealed preference models. Journal of

Environmental Management, 65(3), 301–312. doi:10.

1006/jema.2002.0552

Parsons, G. R., & Thur, S. M. (2008). Valuing changes in

the quality of coral reef ecosystems: A stated preference

study of scuba diving in the Bonaire National Marine

Park. Environmental & Resource Economics, 40(4),

593–608. doi:10.1007/s10640-007-9171-y

Poe, G. L., & Vossler, C. A. (2011). Consequentiality and

contingent values: An emerging paradigm. In J. Bennett

(Ed.), The international handbook on non-market

environmental valuation (416 pp). Cheltenham:

Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. doi:10.4337/

9780857931191

Saengsupavanich, C., Seenprachawong, U., Gallardoa, W.

G., & Shivakoti, G. P. (2008). Port-induced erosion pre-

diction and valuation of a local recreational beach. Eco-

logical Economics, 67(1), 93–103. doi:10.1016/j.

ecolecon.2007.11.018

Shivlani, M. P., Letson, D., & Theis, M. (2003). Visitor

preferences for public beach amenities and beach restor-

ation in South Florida. Coastal Management, 31(4),

367–386. doi:10.1080/08920750390232974

Togridou, A., Hovardas, T., & Pantis, J. D. (2006). Determi-

nants of visitors’ willingness to pay for the National

MarineParkofZakynthos,Greece.EcologicalEconomics,

60(1), 308–319. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.12.006

Tourism Authority of Thailand. (2013). Interactive map:

Mu Ko Chang Marine National Park. Retrieved from

http://www.tourismthailand.org/travel-and-transport/

interactive-map

United Nations Environment Programme. (2007). UNEP/

GEF project on reversing environmental degradation

trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand,

Coral Reef Demonstration Site, Mu Koh Chang, Thai-

land. Retrieved from http://www.unepscs.org/

components/com_remository_files/downloads/MRT-4-

D2-Koh-Chang.pdf

Walpole, M. J., Goodwin, H. J., & Ward, K. G. R. (2001).

Pricing policy for tourism in protected areas: Lessons

from Komodo National Park, Indonesia. Conservation

Biology, 15(1), 218–227. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.

2001.99231.x

Wang, H., Shi, Y. Y., Kim, Y. H., & Kamata, T. (2013).

Valuing water quality improvement in China: A case

study of Lake Puzhehei in Yunnan Province. Ecological

Economics, 94, 56–65. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.

07.006

Wang, P. W., & Jia, J. B. (2012). Tourists’ willingness to

pay for biodiversity conservation and environment pro-

tection, Dalai Lake protected area: Implications for

entrance fee and sustainable management. Ocean &

Coastal Management, 62, 24–33. doi:10.1016/j.

ocecoaman.2012.03.001

Wattayakorn, G. (2006). Environmental issues in the Gulf

of Thailand. In E. Wolanski (Ed.), The environment in

Asia Pacific Harbours (pp. 249–259). The Netherlands:

Springer.

Whittington, D. (2002). Improving the performance

of contingent valuation studies in developing

countries. Environmental and Resource Economics,

22, 323–367.

Xu, Z., Loomis, J., Zhang, Z., & Hamamura, K. (2006).

Evaluating the performance of different willingness to

pay question formats for valuing environmental restor-

ation in rural China. Environment and Development

Economics, 11(5), 585–601. doi:10.1017/

s1355770×06003147

Yamazaki, S., Rust, S. A., Jennings, S. M., Lyle, J. M., &

Frijlink, S. (2011). A contingent valuation of rec-

reational fishing in Tasmania, DPIPWE (IMAS

Report). Retrieved from http://ecite.utas.edu.au/

76224

20 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

Appendix

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 21

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

22 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 23

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

24 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

Willingness to Pay for Coastal Resource Protection in Ko Chang Park 25

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N

ovem

ber

2014

26 Sunida Piriyapada and Erda Wang

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Um

eå U

nive

rsity

Lib

rary

] at

14:

21 1

5 N