Mintz, S, and S McNeil. “Introduction.” America's Reconstruction: … · 2018. 11. 5. ·...

Transcript of Mintz, S, and S McNeil. “Introduction.” America's Reconstruction: … · 2018. 11. 5. ·...

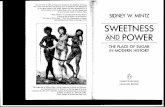

Introduction

Reconstruction, one of the most turbulent and controversial eras in American history, began during the Civil War and ended in 1877. It witnessed America's first experiment in interracial

democracy. Just as the fate of slavery was central to the meaning of the Civil War, so the divisive politics of Reconstruction turned on the status the former slaves would assume in the

reunited nation. Reconstruction remains relevant today because the issues central to it -- the role of the federal government in protecting citizens' rights, and the possibility of economic and racial justice -- are still unresolved.

Northern victory in the Civil War decided the fate of the Union and of slavery, but posed numerous problems. How should the nation be reunited? What system of labor should replace

slavery? What would be the status of the former slaves? Central to Reconstruction was the effort of former slaves to breathe full meaning into their newly

acquired freedom, and to claim their rights as citizens. Rather than passive victims of the actions of others, African Americans were active agents in shaping Reconstruction.

After rejecting the Reconstruction plan of President Andrew Johnson, the Republican Congress enacted laws and Constitutional amendments that empowered the federal government to enforce the principle of equal rights, and gave black Southerners the right to vote and hold

office. The new Southern governments confronted violent opposition from the Ku Klux Klan and similar groups. In time, the North abandoned its commitment to protect the rights of the former

slaves, Reconstruction came to an end, and white supremacy was restored throughout the South.

For much of this century, Reconstruction was widely viewed as an era of corruption and

misgovernment, supposedly caused by allowing blacks to take part in politics. This interpretation helped to justify the South's system of racial segregation and denying the vote to blacks, which

survived into the 1960s. Today, as a result of extensive new research and profound changes in American race relations, historians view Reconstruction far more favorably, as a time of genuine progress for former slaves and the South as a whole.

For all Americans, Reconstruction was a time of fundamental social, economic, and political change. The overthrow of Reconstruction left to future generations the troublesome problem of

racial justice.

Mintz, S, and S McNeil. “Introduction.” America's Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War,

Digital History, 2018, www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/exhibits/reconstruction/epilogue.html.

A New Birth of Freedom: Reconstruction During the Civil War

At the war's outset, the Lincoln administration insisted that restoring the Union was its only

purpose. But as slaves by the thousands abandoned the plantations and headed for Union lines, and military victory eluded the North, the president

made the destruction of slavery a war aim -- a decision announced in the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863.

The Proclamation also authorized the enlistment of black soldiers.

By the end of the Civil War, some 200,000 black soldiers had served in the Union army and navy, staking a claim to citizenship in the postwar nation.

During the war, "rehearsals for Reconstruction" took place in the Union-occupied South. On the

South Carolina Sea Islands, the former slaves demanded land of their own, while government officials and Northern investors urged them to return to work on the plantations.

In addition, a group of young Northern reformers came to the islands to educate the freedpeople and assist in the transition from slavery to freedom. The conflicts among these groups offered a

preview of the national debate over Reconstruction.

Rehearsal for Reconstruction

As the Union army occupied Southern territory, it began to devise policies to deal with the transition from slavery to freedom, and the interrelated questions of access to land and the organization of free

labor. Many of the issues central to Reconstruction were fought out on the Sea Islands of South Carolina, even as the Civil War

continued.

The most famous "rehearsal for Reconstruction" took place on the Sea Islands just off the coast of South Carolina.

When the Union navy occupied the area in November 1861, the white population fled, leaving behind a community of some 10,000 slaves, who believed freedom meant access to land and the

ability to direct their own labor.

Freedmen’s aspirations soon brought them into conflict with new arrivals from the North -- Treasury agents hoping to restore cotton

production, investors seeking to acquire Sea Island land, and a group of young reformers, known as Gideon's Band, who sought to assist

the freedpeople by providing education and preparing them for the competitive world of free labor.

Published by the Pennsylvania Freedmen's Relief Association, this broadside is illustrated with a picture of "Sea-island

School, No 1--St. Helena Island [South Carolina], Established April, 1862."

May 1863 letters from teachers at St. Helena Island describe their young students as "the prettiest little things you ever saw, with solemn little faces, and eyes like stars." Vacations

seemed a hardship to these students, who were so anxious to improve their reading and writing that they begged not to "be

punished so again." Voluntary contributions from various organizations aided fourteen hundred teachers in providing literacy and vocational education for 150,000 freedmen.

Some of the black and white teachers and missionaries from the North, known as Gideon's Band, who went to the Sea

Islands to work with the freedpeople. The first group arrived in

March 1862 and included women such as Susan Walker, a close friend of Salmon Chase (1808-1873), then Secretary of

the Treasury.

These women taught the former slaves to read and sew and were responsible for distributing and selling the clothing sent to them by northern freedmen's aid associations.

Freedmen living on the Sea Islands and throughout the Union-occupied South labored for wages under terms of

yearly contracts drawn up under army supervision. Although the contract labor system allowed production to

resume by stabilizing labor relations during the war, it kept the vast majority of freedmen poor and landless.

In June 1862, the federal government authorized the sale of abandoned lands at public auction.

Although some former slaves pooled their resources to acquire land, Northern investors purchased most of the property.

On January 16, 1865, Union general William T. Sherman, shortly after capturing Savannah, issued Special Field Order 15, setting aside land on the Sea Islands and along the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia for black settlement.

Intended to provide temporary refuge for the large number of former slaves following his army,

Sherman's order nonetheless had the effect of raising blacks' expectations that the land would belong to them permanently. Later, under President Andrew Johnson, the land was restored to its prewar owners.

Mintz, S, and S McNeil. “A New Birth of Freedom: Reconstruction During the Civil War.” America's

Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War, Digital History, 2018,

www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/exhibits/reconstruction/epilogue.html.

The Meaning of Freedom: Black and White Responses to the End of Slavery

Confederate defeat and the end of slavery brought far-reaching changes in the lives of all Southerners. The destruction of slavery led inevitably to conflict between blacks seeking to

breathe substantive meaning into their freedom by asserting their independence from white control, and whites seeking to retain as much as possible of the old order.

The meaning of freedom itself became a point of conflict in the Reconstruction South. Former slaves relished the opportunity to flaunt their liberation from the innumerable regulations of

slavery.

Immediately after the Civil War, they sought to give meaning to freedom by reuniting families separated under slavery, establishing their own churches and schools, seeking economic

autonomy, and demanding equal civil and political rights.

Most white Southerners reacted to defeat and

emancipation with dismay. Many families had suffered the loss of loved ones and the destruction of property. Some thought of leaving the South altogether, or retreated into

nostalgia for the Old South and the Lost Cause of the Confederacy.

In 1865 and 1866 many white Southerners joined memorial associations that established Confederate

cemeteries and monuments throughout the region. Others, unwilling to accept a new relationship to former slaves, resorted to violent opposition to the new world being created around them.

Building the Black Community: The Family

Reuniting families separated under slavery, and solidifying

existing family relations, were essential to the black definition of freedom. The family stood as the main pillar of the postwar black community.

Most slaves had lived in family units, although they faced the constant threat of separation

from loved ones by sale. Freedpeople made remarkable

efforts to locate loved ones - a Northern reporter in 1865

encountered a former slave who had walked more than 600 miles searching for his wife and children, from whom he had

been sold away during slavery. Slave marriages had no legal standing; now tens of thousands

of freedpeople registered their unions before the army, Freedmen's Bureau, and local governments.

After the war, African Americans searched with varying degrees of success for family members separated by slave

sales or by the disruptions of war.

Building the Black Community: The Church

The creation of autonomous black churches was a major achievement of the Reconstruction era,

and a central component of blacks' conception of freedom.

The first institution fully controlled by African-Americans, the church played a

central role in the black community.

Before the Civil War, many rural slaves had held secret religious meetings

outside the supervision of their owners.

Other slaves, along with free blacks, had belonged to biracial congregations

controlled by whites, many of which required black members to sit in the back

of the church or the galleries during services.

With emancipation, blacks withdrew from these institutions to create their own

churches. They pooled their resources to purchase land and erect church buildings.

A place of worship, the church also housed schools, social events, and political gatherings, and

sponsored benevolent and fraternal societies. Black ministers also came to play a major role in

Reconstruction politics.

Building the Black Community: The School

Education, denied them under slavery, was essential to the African-American understanding of freedom. Young and old, the freedpeople flocked to the schools established after the Civil War.

For both races, Reconstruction laid the foundation for public schooling in the South.

Northern benevolent societies, the Freedmen's Bureau, and, after 1868, state governments, provided most of the funding

for black education, but the initiative often lay with blacks themselves, who purchased land, constructed buildings, and raised money to hire teachers.

The desire for learning led families to move to towns and cities

so that their children could have access to education, and children to instruct their parents after school hours.

Reconstruction also witnessed the creation of the nation's first

black colleges, including Howard University in Washington, D.C., Fisk University in Tennessee and Hampton Institute in

Virginia. Initially, these institutions emphasized the training of black teachers and by 1869, blacks

outnumbered whites among the nearly 3,000 men and women teaching the freedpeople in the South.

Before the Civil War, only North Carolina among Southern states had established a comprehensive system of education

for white children. During Reconstruction, public education came to the South.

During reconstruction, the Freedman's Bureau, missionary

societies, and blacks themselves established over 3,000 schools in the South, laying the foundation for public education in the region.

Many young men and women who attended freedman's schools became teachers who instructed the next generation.

Chartered by an act of Congress in 1867, Howard University offered black students preparatory and collegiate programs, including course work in law, medicine, education, and pharmacy.

The university was named for Gen. Oliver O. Howard, head of the Freedman's Bureau, who later served as the University's president.

Quest for Economic Autonomy and Equal Rights

The desire for autonomy and equality shaped African-Americans' definition of freedom. Blacks

wished to take control of the conditions under which they labored, and carve out the greatest possible economic independence. In public life, they demanded recognition of their equal rights as American citizens.

Immediately after the Civil War, blacks throughout the South organized mass meetings and

conventions demanding equality before the law, the right to vote, and equal access to schools, transportation, and other public facilities.

The end of slavery, they insisted, enabled America for the first time to live up to the full

implications of its democratic creed by abandoning racial discrimination and accepting blacks (or at least the adult males among them) into the political nation.

Free blacks, ministers, artisans, and former soldiers predominated at these early meetings. Many of the delegates would go on to distinguished careers of public service during

Reconstruction.

Memory and Mourning

Most Southern whites responded to defeat with grief and dismay. "The demoralization is complete," wrote a Georgia girl. "We are whipped, there is no doubt about it."

Privately, white Southerners struggled to come to terms with the appalling loss of life, a disaster

without parallel in the American experience.

Many women had taken on new roles during the Civil War, assuming greater and greater

authority for managing farms and plantations while their husbands were absent, or serving as nurses, teachers, and in other professions.

The death of nearly 260,000 soldiers meant that women would continue to fill these roles, even as they struggled to help surviving husbands and sons adapt to the reality of defeat.

While some white Southerners looked to the future and a New South, others turned with nostalgia to a romanticized view of slavery and of the Confederacy, increasingly remembered as a noble Lost Cause.

The establishment of cemeteries and Confederate memorial days reflected this effort to carve

out a recognition of the Confederate war effort in the South's public space.

Violence

Violence swept across parts of the South in the aftermath of the Civil War, reflecting the immense tensions created by the end of slavery and Confederate defeat, and white Southerners'

determined resistance to blacks' quest for autonomy.

Freedpeople were assaulted and murdered for attempting to

leave plantations, disputing contract settlements, seeking to enter white-controlled churches, and refusing to step off sidewalks to allow white

pedestrians to pass.

Occasionally, as in the Memphis and New Orleans riots of

1866, black communities became the victims of wholesale assault by white mobs, aided by the local police.

In these outbreaks, schools, churches, and other community

institutions, symbols of black freedom, became the targets of violence, as well as private homes and individual African-

Americans.

Mintz, S, and S McNeil. “The Meaning of Freedom: Black and White Responses to Slavery.” America's

Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War, Digital History, 2018,

www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/exhibits/reconstruction/epilogue.html.

From Slave Labor to Free Labor

The most difficult task confronting many Southerners during Reconstruction was devising a new

system of labor to replace the shattered world of slavery. The economic lives of planters, former slaves, and nonslaveholding whites, were transformed after the Civil War.

Planters found it hard to adjust to the end of slavery. Accustomed to absolute control over their labor force, many sought to restore the old discipline, only to meet determined opposition from the freedpeople, who equated freedom with economic autonomy.

Many former slaves believed that their years of unrequited labor gave them a claim to land; "forty acres and a mule" became their rallying cry. White reluctance to sell to blacks, and the

federal government's decision not to redistribute land in the South, meant that only a small percentage of the freedpeople became landowners. Most rented land or worked for wages on white-owned plantations.

During Reconstruction, many small white farmers, thrown into poverty by the war, entered into cotton production, a major change from prewar days when they concentrated on growing food

for their own families.

Out of the conflicts on the plantations, new systems of labor slowly emerged to take the place of slavery. Sharecropping dominated the cotton and tobacco South, while wage labor was the rule

on sugar plantations.

Increasingly, both white and black farmers came to depend on local merchants for credit. A cycle

of debt often ensued, and year by year the promise of economic independence faded.

Free Labor

The postwar South remained overwhelmingly agricultural. The implements of work were the same as before the war, but relations between planters, laborers, and merchants had changed forever.

As under slavery, most rural blacks worked on land owned by whites. But they now exercised control over their personal lives,

could come and go as they pleased, and determined which members of the family worked in the fields.

In early Reconstruction, many black women, seeking to devote

more time to their families, sought to withdraw from field labor, a decision strongly resisted by plantation owners.

Children, whose labor had been dictated by the owner under slavery, now attended school.

As a result, landowners complained of a persistent "labor shortage"

throughout Reconstruction, another way of saying that free labor could not be controlled as rigidly as slave labor.

Some urban growth occurred during Reconstruction, both in cities

like Richmond and smaller market centers scattered across the cotton belt. Cities offered more

diverse work opportunities for both black and white laborers.

Under the sharecropping system, which emerged as the dominant labor system in the rural South, black families

rented individual plots of land. The system placed a premium on utilizing the labor of all members of the family.

During Reconstruction, cotton remained the South's most important crop with the tools and methods of production

essentially the same as before the war.

Most former slaves now worked as sharecroppers, who kept one-third to one-half of the crop for themselves with the remainder going to the landowner. Although the system

afforded workers some degree of autonomy, it kept most in a state of poverty and impeded the South's economic development.

After the war, rice production continued along the southeast coast. Rice workers used traditional tools and methods developed in West Africa.

A variety of labor systems coexisted on rice plantations but nearly all included the traditional task system developed in antebellum days. In the task system, laborers, rather than working in

gangs under an overseer, performed assigned tasks after which they hunted, fished, or grew crops on their own time. As a result, rice workers enjoyed a greater degree of autonomy than

most former slaves, who worked under tighter controls.

Sugar workers continued to labor in closely supervised gangs after the Civil War. The system persisted because each plantation had its own steam-powered sugar mill that required a large

crop and labor force to insure economic viability.

An influx of Northern capital allowed sugar planters to pay their workers in cash, but conflicts between owners and workers arose over wages and discipline.

After the Civil War, a growing number of white workers, including many children, found

employment in tobacco and textile factories. African-Americans were largely excluded from factory employment in the South.

The Planter's Domain

The system of sharecropping, in which individual families rented portions of a plantation, arose in large measure as a compromise between planters' desire for a disciplined labor force, and

blacks' insistence on controlling their own day-to-day labor.

Many planters were devastated economically by the Civil War. The loss of capital invested in slaves, and life savings that had been patriotically invested in Confederate bonds, reduced many

to poverty. Some were compelled, for the first time in their lives, to do physical labor. Those who managed to resume production believed it would be next to impossible to prosper using free

black labor.

It was widely believed that African-Americans would work only when coerced. Charges of "indolence" were directed not against blacks unwilling to work at all, but at those who preferred

to work for themselves rather than signing contracts with planters.

Many landowners wrote into labor contracts detailed provisions requiring freedpeople to labor in gangs as under slavery, and obey their employers' every command. But contracts could not create a submissive labor force; because of the labor shortage, dissatisfied freedpeople could

always find employment elsewhere.

Winslow Homer's cartoon criticizing the post-war attitudes of

many Southern whites toward freedpeople depicts a leisured white planter admonishing his former slave, "My boy, we've toiled and taken care of you long enough - now, you've got to

work!"

After the Civil War, country stores offered a variety of goods

shipped from the North.

Farmers and sharecroppers often could not afford to make a purchase except "on credit" at exorbitant interest rates.

Widespread use of credit increased debt and poverty among rural Southerners during the Reconstruction era.

The White Farmer

Many white small farmers turned to cotton production during Reconstruction as a way of obtaining needed cash. As cotton prices declined, many lost their land. By 1880, one third of the

white farmers in the cotton states were tenants rather than landowners, and the South as a whole had become even more dependent on cotton than it had been before the war.

Before the Civil War, the majority of the South's white population owned no slaves. Few of these farmers grew much cotton; they preferred to concentrate on food crops for their own families, marketing only a small surplus, and making most of the tools, clothing, and other items they

needed at home.

The widespread destruction of the war plunged many small farmers into debt and poverty, and

led many to turn to cotton growing. The increased availability of commercial fertilizer and the spread of railroads into upcountry white areas, hastened the spread of commercial farming.

By the mid-1870s, the South's cotton output reached prewar levels. But now, nearly forty

percent was raised by white farmers. Like black sharecroppers, those who wished to borrow money were forced to pledge the year's cotton crop as collateral. Some found economic

salvation in cotton farming, but many others fell further and further into debt.

Mintz, S, and S McNeil. “From Slave Labor to Free Labor.” America's Reconstruction: People and Politics

After the Civil War, Digital History, 2018,

www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/exhibits/reconstruction/epilogue.html.

Rights and Power: The Politics of Reconstruction

Reconstruction was an era of unprecedented political conflict and of far-reaching changes in the

nature of American government.

At the national level, new laws and constitutional amendments permanently altered the federal

system and the definition of citizenship.

In the South, a politically mobilized black community joined with white allies to bring the Republican party to power, while excluding those accustomed to ruling the region.

The national debate over Reconstruction centered on three questions: On what terms should the defeated Confederacy be reunited with the Union?

Who should establish these terms, Congress or the President? What should be the place of the former slaves in the political life of the South?

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln announced a lenient plan, with suffrage limited

to whites, to attract Southern Confederates back to the Union. By the end of his life, however, Lincoln had come to favor extending the right to vote to educated blacks and

former soldiers.

Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson, in 1865 put into effect his own Reconstruction plan, which gave the white South a free hand in establishing new

governments. Many Northerners became convinced that Johnson's policy, and the actions of the governments he established, threatened to reduce African Americans to a

condition similar to slavery, while allowing former "rebels" to regain political power in the South.

As a result, Congress overturned Johnson's program.

Between 1866 and 1869, Congress enacted new laws and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments to the Constitution, guaranteeing blacks' civil rights and giving black men the right

to vote.

These measures for the first time enshrined in American law the principle that the rights of

citizens could not be abridged because of race. And they led directly to the creation of new governments in the South elected by blacks as well as white - America's first experiment in interracial democracy.

Presidential Reconstruction

In 1865 President Andrew Johnson implemented a plan of Reconstruction that gave the white

South a free hand in regulating the transition from slavery to freedom and offered no role to blacks in the politics of the South. The conduct of the governments he established turned many Northerners against the president's policies.

The end of the Civil War found the nation without a settled Reconstruction policy.

In May 1865, President Andrew Johnson offered a pardon to all white Southerners except Confederate leaders and wealthy planters (although most of these later received individual

pardons), and authorized them to create new governments.

Blacks were denied any role in the process. Johnson also ordered nearly all the land in the hands

of the government returned to its prewar owners -- dashing black hope for economic autonomy.

At the outset, most Northerners believed Johnson's plan deserved a chance to succeed. The course followed by Southern state governments under Presidential Reconstruction, however,

turned most of the North against Johnson's policy. Members of the old Southern elite, including many who had served in the Confederate government and army, returned to power.

The new legislatures passed the Black Codes, severely limiting the former slaves' legal rights and economic options so as to force them to return to the plantations as dependent laborers. Some states

limited the occupations open to blacks. None allowed any blacks to vote, or provided public funds for their education.

The apparent inability of the South's white leaders to accept the reality of emancipation undermined Northern support for Johnson's policies.

Succeeding to the presidency after Lincoln's death, Johnson failed to provide the nation with enlightened leadership, or deal effectively

with Congress. Racism prevented him from responding to black demands for civil rights, and personal inflexibility rendered him

unable to compromise with Congress.

Johnson's vetoes of Reconstruction legislation and opposition to the Fourteenth Amendment alienated most Republicans. In 1868, he came within one vote of being removed from office by

impeachment.

He was returned to the U.S. Senate in 1875, but died within a few months of taking office.

"Selling a Freeman to Pay His Fine at Monticello, Florida," Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper,

January 19, 1867.

The Black Codes, a series of laws passed by Southern states

to define freedman's rights and responsibilities, imposed serious restrictions upon former slaves.

According to Florida's Black Code, blacks who violated broke

labor contracts could be whipped, pilloried, and sold for up to one year's labor.

The Black Codes created an uproar among many Northerners, who considered them to be another form of slavery.

Congress and Civil Rights

Reconstructing the South became a divisive issue in national politics, pitting President Johnson

against the Republican majority in Congress. Eventually, Congress implemented its own plan of Reconstruction, based on federal action protecting the rights of the former slaves.

Federal laws and two further Constitutional Amendments established the principle of equal rights for all citizens,

regardless of race.

When Congress assembled in December 1865, Radical

Republicans called for the overthrow of the governments established under President Johnson's Reconstruction policy and the establishment of new ones with black men as well as white allowed to vote. Moderate Republicans, still hoping to work with the president, rejected this

plan.

Following their lead, Congress adopted two bills, one extending the life of the Freedmen's

Bureau, the second, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, guaranteeing blacks' equality before the law, short of the suffrage.

Johnson's veto of these measures moved many moderates into the radical camp, and

inaugurated a bitter conflict over control of Reconstruction policy, which culminated in 1868 when he was nearly removed from office by impeachment.

In 1866, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act over Johnson's veto, and proceeded to approve the Fourteenth Amendment, which forbade states to deprive any citizen of the "equal protection of the laws," the first Constitutional guarantee of the principle of equal civil rights regardless of

race.

This was a major change in the federal system, establishing the national government as the

arbiter of citizens' rights, and empowering it to overturn discriminatory measures adopted by state governments.

The Civil Rights Bill was the first major law in American history to be passed over a presidential veto.

Ratified in 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited states from abridging the right to vote

because of race, although it allowed other restrictions based on education, property and sex to remain in effect.

The Fifteenth Amendment declared that the right to vote could not be denied “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” It did not explicitly guarantee the right to hold office or serve on juries;

nor did it ensure federal protection of voting rights.

Nevertheless, at a time when only seven northern states

allowed blacks to vote, the Fifteenth Amendment represented a significant step toward legal equality.

In 1865, Congress established the Freedmen's Bureau to

provide assistance to former slaves. Union Army general Oliver O. Howard was the Bureau's Commissioner.

Political cartoons used racist imagery to reflect Democratic charges that government assistance would benefit indolent freedman at the expense of whites, and linking suffrage for

blacks with the enfranchisement of Chinese immigrants and Native Americans.

Among other responsibilities, bureau agents negotiated labor contracts and settled disputes between black and white Southerners. The Bureau's jurisdiction in civil matters eventually

became a point of controversy.

The National Debate Over Reconstruction; Impeachment; and the Election of Grant

The breach between President and Congress inaugurated a period of bitter debate over Reconstruction. Congress failed in 1868 to remove Johnson from office, but the election of Ulysses S. Grant as his successor guaranteed that Reconstruction as established by the

Republican party would continue.

Despite strong appeals to racial prejudice and the principle of states rights by Johnson's

supporters, the Northern electorate gave Republicans a resounding triumph in the elections of 1866.

The following March, Congress enacted the Reconstruction Act over Johnson's veto, placing the

South under temporary military rule. The law extended the vote to Southern black men, while temporarily depriving many white leaders of the rights to vote and hold office.

The Reconstruction Act launched the period of Congressional, or Radical, Reconstruction, which lasted until 1877.

The conflict between President Johnson and Congress did not end with the passage of the

Reconstruction Act. When, in February 1868, Johnson removed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, in violation of the recently-enacted Tenure of Office Act, he was impeached by the

House of Representatives.

The Senate failed by one vote to remove him from office. Shortly after the trial, the Republicans

nominated Ulysses S. Grant, the North's greatest war hero, for president. Grant defeated Democrat Horatio Seymour in the election of 1868.

President Johnson's ability to work with Congress and his public popularity ended as he followed

a plan of Reconstruction that gave Southern whites a free hand in establishing new governments that threatened to reduce African-Americans to a condition similar to

slavery.

After Johnson vetoed several Reconstruction measures passed by Congress, his opponents charged him with autocratic behavior.

Much of the debate over Reconstruction swirled around the Freedman's Bureau and efforts to extend suffrage to non-whites.

The 1868 presidential campaign revolved around the issues of Reconstruction. The Democrats' nominee, Horatio Seymour, ran on a platform opposing Reconstruction.

"This Is A White Man's Government" became the slogan of a Democratic campaign that openly appealed to racial fears and

prejudice.

Political cartoonist Thomas Nast ridiculed the Democratic party as a coalition of Irish immigrants (left), white supremacists like Nathan Bedford Forrest, leader of the Ku Klux Klan (center), and

Northern capitalists represented by Horatio Seymour (right). Nast's cartoon depicted Democrats as the oppressors of the black race, represented by a black Union soldier felled while carrying

the American flag and a ballot box.

Reconstruction Government in the South

Under the terms of the Reconstruction Act of 1867, Republican governments came to power

throughout the South, offering blacks, for the first time in American history, a genuine share of political power. These governments established the region's first public school systems, enacted

civil rights laws, and sought to promote the region's economic development.

The coming of black suffrage under the Reconstruction Act of 1867 produced a wave of political mobilization among African Americans in the South.

In Union Leagues and impromptu gatherings, blacks organized to demand equality before the law and economic opportunity.

Blacks were joined by white newcomers from the North - called "carpetbaggers" by their political opponents. And the Republican party in some states attracted a considerable

number of white Southerners, to whom Democrats applied the name "scalawag" - mostly Unionist small farmers but including

some prominent plantation owners.

By 1870, the former Confederate states had been readmitted to the Union under new constitutions that marked a striking

departure in Southern government. For the first time in the region's history, state-funded public school systems were

established, as well as orphan asylums and other facilities.

The new governments passed the region's first civil rights

laws, reformed the South's antiquated tax system, and embarked on ambitious and expensive programs of economic development, hoping that railroad and factory development would produce a prosperity shared by both races.

Composed of slave ministers, artisans, and Civil War veterans, and blacks who had been free before the Civil War, a black political leadership emerged that pressed aggressively for an end to

the South's racial caste system.

African Americans served in virtually every governmental capacity during Reconstruction, from member of Congress to state and local officials. Their presence in positions of political power

symbolized the political revolution wrought by Reconstruction.

Widely used as travel bags in the mid 19th century, carpetbags became associated with

Northern white Republicans who moved South after the Civil War.

"Carpetbagger," a derisive term devised by Reconstruction's opponents, has remained part of the vocabulary of American politics.

Mintz, S, and S McNeil. “Rights and Power: The Politics of Reconstruction.” America's Reconstruction: People

and Politics After the Civil War, Digital History, 2018,

www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/exhibits/reconstruction/epilogue.html.

The Ending of Reconstruction

In the 1870's, violent opposition in the South and the North's retreat from its commitment to

equality, resulted in the end of Reconstruction. By 1876, the nation was prepared to abandon its commitment to equality for all citizens regardless of race.

As soon as blacks gained the right to vote, secret societies sprang up in the South, devoted to restoring white supremacy in politics and social life. Most notorious was the Ku Klux Klan, an organization of violent criminals that established a reign of terror in some parts of the South,

assaulting and murdering local Republican leaders.

In 1871 and 1872, federal marshals, assisted by U. S. troops, brought to trial scores of

Klansmen, crushing the organization. But the North's commitment to Reconstruction soon waned. Many Republicans came to believe that the South should solve its own problems without further interference from Washington. Reports of Reconstruction corruption led many

Northerners to conclude that black suffrage had been a mistake. When anti-Reconstruction violence erupted again in Mississippi and South Carolina, the Grant administration refused to

intervene.

The election of 1876 hinged on disputed returns from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, where Republican governments still survived. After intense negotiations involving leaders of both

parties, the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, became president, while Democrats assumed control of the disputed Southern states. Reconstruction had come to an end.

The Opposition to Reconstruction

From the outset, Reconstruction governments aroused bitter opposition among the majority of

white Southerners. Though they disagreed on specific policies, all of Reconstruction's opponents agreed that the South must be ruled by white supremacy.

The reasons for white opposition to Reconstruction were many. To numerous former

Confederates, the new governments appeared as living reminders of military defeat. Their ambitious programs of economic development and school construction produced rising taxes and

spiraling state debts. In some states, these programs also spawned corruption, in which Democrats as well as Republicans shared, but which served to discredit Republican rule. Many whites deeply resented the absence of the region's former leaders from positions of power, and

planters disliked the tendency of local officials to side with former slaves in labor disputes.

The essential reason for the growing opposition to Reconstruction, however, was the fact that

most Southern whites could not accept the idea of African Americans voting and holding office, or the egalitarian policies adopted by the new governments. Beginning in 1867, Southern Democrats launched a campaign of vilification against Reconstruction, employing lurid appeals to

racial prejudice as well as more measured criticisms of Reconstruction policies.

The Ku Klux Klan

Founded in 1866 as a Tennessee social club, the Ku Klux Klan was soon transformed into an organization of terrorist criminals, which spread into nearly every Southern state. Led by planters, merchants, and Democratic politicians, the Klan committed some of the most brutal

acts of violence in American history.

The Klan first came to national prominence during the 1868 presidential campaign, when its

members assassinated Arkansas congressman James M. Hinds, three South Carolina legislators, and other Republican leaders. In Georgia and Louisiana, it established a reign of terror so

complete that blacks were unable to go to the polls, and Democrats carried both states in the presidential election.

Klan violence accelerated in 1869 and 1870. The organization singled out local Republican leaders, including white officeholders and teachers. Most victims, however, were freedpeople,

including political organizers as well as former slaves who had acquired land or engaged in contract disputes with employers. Institutions like black churches and schools frequently became targets. The Klan's aim was to restore white supremacy in all areas of Southern life -- in

government, race relations, and on the plantations.

The new Southern governments generally proved unable to restore order. Only the intervention

of federal marshals in 1871, backed up by the army, succeeded in crushing the Klan.

The goal of the Klan was to destroy Reconstruction efforts by murdering African Americans and the white Republican politican or those who educated black children.

The Klan's threats of violence terrorized black and white Republicans.

This cartoon sent a threat to a carpetbagger from Ohio, the

Rev. A. S. Lakin, who had just been elected president of the University of Alabama, and Dr. N. B. Cloud, a scalawag serving as Superintendent of Public Instruction of Alabama.

The Klan succeeded in driving both men from their positions.

The North's Retreat

Despite the Grant administration's effective response to Klan terrorism, the North's commitment to Reconstruction waned during the 1870s. Many Radical leaders passed from the scene, their place taken by politicians less committed to the ideal of equal rights for black citizens. Many

Northerners felt the South should be able to solve its own problems without constant interference from the North.

In 1872, a group of Republicans alienated by corruption within the Grant administration bolted the party. These Liberal Republicans nominated New York editor Horace Greeley for president, and he was endorsed by the Democrats. Greeley's campaign stressed that the South would

prosper under "local self-government," with the "best men" (traditional white leaders) restored to power.

Despite Grant's reelection, Northerners were growing tired of Reconstruction, a reaction accelerated when a depression began in 1873, pushing economic issues to the forefront of politics instead of sectional ones. Racism, which had waned in the aftermath of the Civil War,

now reasserted itself. Influential Northern newspapers portrayed Southern blacks not as upstanding citizens but as little more than unbridled animals, incapable of taking part in

government.

When, in 1874 and 1875, anti-Reconstruction violence again reared its head in the South, few Northerners believed the federal government should intervene to suppress it.

As white Americans grew weary of Reconstruction, derogatory images of African Americans became more prevalent and accepted in the North as well as in the South.

As public interest in the issues of Reconstruction began to wane, a more idealized view of the South began to emerge, with prosperous plantations manned by industrious blacks working

under the supervision of benevolent whites.

The Centennial Election

In 1876, the United States marked the centennial of the Declaration of Independence. A yearlong exposition in Philadelphia celebrated a century of material and moral progress. Yet the year's election campaign was again marked by violence in the South. The Bargain of 1877

resolved disputes over the election's results, and resulted in the final abandonment of Reconstruction.

By 1876, Reconstruction had been overthrown in all the Southern states except South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. The presidential election hinged on the outcome in these states, which both parties claimed to have carried.

After prolonged controversy and behind-the-scenes negotiations, Democratic and Republican leaders worked out a solution to the disputed election of 1876. In the Bargain of 1877,

Republican Rutherford B. Hayes became president, and he, in turn, recognized Democratic control of the remaining Southern states and promised to end federal intervention in the South. United States troops who had been guarding the state houses in South Carolina and Louisiana

were ordered to return to their barracks (not to leave the region entirely, as is widely believed). The Redeemers, as the Southern Democrats who overturned Republican rule called themselves,

now ruled the entire South.

Mintz, S, and S McNeil. “The Ending of Reconstruction.” America's Reconstruction: People and Politics After

the Civil War, Digital History, 2018, www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/exhibits/reconstruction/epilogue.html.

Epilogue: The Unfinished Revolution

In the generation after the end of Reconstruction, the Southern states deprived blacks of their

right to vote, and ordered that public and private facilities of all kinds be segregated by race. Until job opportunities opened in the North in the twentieth century, spurring a mass migration

out of the South, most blacks remained locked in a system of political powerlessness and economic inequality. A hostile and biased historical interpretation of Reconstruction as a tragic era of black supremacy became part of the justification for the South's new system of white

supremacy.

Not until the mid-twentieth century would the nation again attempt to come to terms with the

political and social agenda of Reconstruction. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s is often called the Second Reconstruction. Its achievements were far-reaching. Today, racial segregation has been outlawed, blacks vote on the same terms as whites, and more black

Americans hold public office than ever before.

Like the first Reconstruction, however, the second failed to erase the economic inequalities that

originated in slavery and were reinforced by decades of segregation. Many black Americans have entered the middle class, but unemployment and poverty remain far higher than among whites.

Some Americans believe the nation has made major progress in living up to the ideal of equality.

Others are more impressed with how far we still are from that ideal.

Mintz, S, and S McNeil. “Epilogue: The Unfinished Revolution.” America's Reconstruction: People and

Politics After the Civil War, Digital History, 2018,

www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/exhibits/reconstruction/epilogue.html.