MINERVA ANESTESIOLOGICA - Siaarti · P. Di Marco (Roma, Italy) J. T ... Pediatric Anesthesia...

Transcript of MINERVA ANESTESIOLOGICA - Siaarti · P. Di Marco (Roma, Italy) J. T ... Pediatric Anesthesia...

EDITORIAL BOARD

EDITOR IN CHIEFF. CavaliereRoma, Italy

General Critical CareAssociate Editor

G. M. Albaiceta (Oviedo, Spain)Section Editor

G. Biancofiore (Pisa, Italy)E. De Robertis (Napoli, Italy)

Circulation Critical CareSection Editor

S. Scolletta (Siena, Italy)E. Bignami (Milano, Italy),

Respiration Critical CareSection Editor

S. Grasso (Bari, Italy)P. Terragni (Sassari, Italy),

Neurocritical CareSection Editor

F. S. Taccone (Brussels, Belgium)

Section EditorA. Giannini (Milano, Italy)

Section EditorM. Allegri (Parma, Italy)F. Coluzzi (Roma, Italy)

ETHICS PAIN

Section EditorB. M. Cesana (Brescia, Italy)

MEDICAL STATISTIC

General AnesthesiaAssociate Editor

M. Rossi (Roma, Italy)Section Editor

E. Cohen (New York, USA)P. Di Marco (Roma, Italy)

J. T. Knape (Utrecht, The Netherlands)O. Langeron (Paris, France)

P. M. Spieth (Dresden, Germany)

Pediatric AnesthesiaSection Editor

M. Piastra (Roma, Italy)

Obstetric AnesthesiaSection Editor

E. Calderini (Milano, Italy)

Regional AnesthesiaSection Editor

A. Apan (Giresun, Turkey)M. Carassiti (Roma, Italy)

CRITICAL CARE ANESTHESIA

MANAGING EDITORA. Oliaro

Torino, Italy

MINERVA ANESTESIOLOGICAITALIAN JOURNAL OF ANESTHESIOLOGY AND ANALGESIA

MONTHLY JOURNAL FOUNDED IN 1935 BY A. M. DOGLIOTTIOFFICIAL JOURNAL OF ITALIAN SOCIETY OF ANESTHESIOLOGY, ANALGESIA,

RESUSCITATION AND INTENSIVE CARE (S.I.A.A.R.T.I.)

Vol. 82 - No. 3 MINERVA ANESTESIOLOGICA V

This journal is PEER REVIEWED and is quoted in:

Current Contents, SciSearch, PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus

G E N E R A L I N F O R M A T I O N

Subscribers: Payment to be made in Italy: a) by check; b) by bank transfer to: Edizioni Minerva Medica, INTESA SANPAOLO Branch no. 18 Torino. IBAN: IT45 K030 6909 2191 0000 0002 917 c) through postal account no. 00279109 in the name of Edizioni Minerva Medica, Corso Bramante 83-85, 10126 Torino; d) by credit card Diners Club International, Master Card, VISA, American Express. Foreign countries: a) by check; b) by bank transfer to: Edizioni Minerva Medica, INTESA SANPAOLO Branch no. 18 Torino. IBAN: IT45 K030 6909 2191 0000 0002 917; BIC: BCITITMM c) by credit card Diners Club International, Master Card, VISA, American Express. Members: for payment please contact the Administrative Secretariat SIAARTI.Notification of changes to mailing addresses, e-mail addresses or any other subscription information must be received in good time. Notification can be made by sending the new and old information by mail, fax or e-mail or directly through the website www.minerva-medica.it at the section “Your subscriptions - Contact subscriptions department”.Complaints regarding missing issues must be made within six months of the issue’s publication date.Prices for back issues and years are available upon request.© Edizioni Minerva Medica - Torino 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.Monthly publication. Authorized by Turin Court no. 281 of 24-1-1953.

Published byEdizioni Minerva Medica - Corso Bramante 83-85 - I-10126 Turin (Italy)

Tel. +39 (011) 678282 - Fax +39 (011) 674502 Website: www.minervamedica.it

Editorial office: [email protected] - Subscriptions: [email protected]: [email protected]

Presidential Office: Antonio Corcione, UOC Anestesia e TIPO, Azienda Ospedaliera dei Colli, V. Monaldi, Via Leonardo Bianchi 1, 80131 Naples, Italy - Tel. 081 7065214. E-mail: [email protected]

Technical Secretariat: S.I.A.A.R.T.I., Viale dell’Università 11, 00185 Rome, Italy - Tel. 06 4452816

E-mail: [email protected] - Website: www.siaarti.it

Administrative Secretariat S.I.A.A.R.T.I. - Edizioni Minerva Medica - Corso Bramante 83-85 - 10126 Turin, Italy - Tel. +39 (011) 678282 - Fax +39 (011) 674502 - E-mail: [email protected]

ITALY

Individual: Print € 130,00 Print+Online € 135,00 Online € 140,00

Institutional: Print € 180,00

Online Small € 350,00 Medium € 407,00 Large € 429,00

Print+Online Small € 367,00 Medium € 420,00 Large € 446,00

EUROPEAN UNION

Individual: Print € 225,00 Print+Online € 235,00 Online € 245,00

Institutional: Print € 300,00

Online Small € 351,00 Medium € 409,00 Large € 429,00

Print+Online Small € 378,00 Medium € 430,00 Large € 456,00

OUTSIDE THEEUROPEAN UNION

Individual: Print € 250,00 Print+Online € 260,00 Online € 270,00

Institutional: Print € 335,00

Online Small € 383,00 Medium € 446,00 Large € 462,00

Print+Online Small € 404,00 Medium € 467,00 Large € 483,00

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTIONS

VI MINERVA ANESTESIOLOGICA March 2016

Impact factor: 2,134

This Journal complies with the Code of Self-Discipline of Medical/Scientific Publishers associated with FARMAMEDIA and may accept advertisingThis Journal is associated with

I N S T R U C T I O N S T O A U T H O R S

Minerva Anestesiologica is the journal of the Italian National Society of Anaesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care (SIAARTI). Minerva Anestesiologica publishes scientific papers on Anesthesiology, Intensive care, Analgesia, Perioperative Medicine and related fields. Manuscripts are expected to comply with the instructions to authors which conform to the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Editors by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (http://www.icmje.org/).Articles not conforming to international standards will not be con-sidered for acceptance. Submission of manuscriptsPapers should be submitted directly to the online Editorial Office at the Edizioni Minerva Medica website:www.minervamedicaonlinesubmission.it Duplicate or multiple publicationSubmission of the manuscript means that the paper is original and has not yet been totally or partially published, is not currently under evaluation elsewhere, and, if accepted, will not be published else-where either wholly or in part. Splitting the data concerning one study in more than one publi-cation could be acceptable if authors justify the choice with good reasons both in the cover letter and in the manuscript. Authors should state the new scientific contribution of their manuscript as compared to any previously published article derived from the same study. Relevant previously published articles should be included in the cover letter of the currently submitted article.Permissions to reproduce previously published materialMaterial (such as illustrations) taken from other publications must be accompanied by the publisher’s permission.CopyrightThe Authors agree to transfer the ownership of copyright to Minerva Anestesiologica in the event the manuscript is published. Ethics committee approvalAll articles dealing with original human or animal data must include a statement on ethics approval at the beginning of the methods sec-tion, clearly indicating that the study has been approved by the ethics committee. This paragraph must contain the following informa-tion: the identification details of the ethics committee; the protocol number that was attributed by the ethics committee and the date of approval by the ethics committee.The journal adheres to the principles set forth in the Helsinki Declaration (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html) and states that all reported research concern-ing human beings should be conducted in accordance with such principles. The journal also adheres to the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals (http://www.cioms.ch/publications/guidelines/1985_texts_of_guidelines.html) recommended by the WHO and requires that all research on animals be conducted in accordance with these principles. Patient consentAuthors should include at the beginning of the methods section of their manuscript a statement clearly indicating that patients have given their informed consent for participation in the research study.Every precaution must be taken to protect the privacy of patients.Conflicts of interestAuthors must disclose possible conflicts of interest including finan-cial agreements or consultant relationships with organizations involved in the research. All conflicts of interest must be declared both in the authors’ statement form and in the manuscript file. If there is no conflict of interest, this should also be explicitly stated as none declared. All sources of funding should be acknowledged in the manuscript. AuthorshipAll persons and organizations that have participated to the study must be listed among the Authors or in the acknowledgements. Authors must meet the criteria for authorship established by the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Editors by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (http://www.icmje.org/).

Authors’ statementPapers must be accompanied by the authors’ statement (http://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/minerva-anestesiologica/index.php) relative to copyright, originality, authorship, ethics and conflicts of interest, signed by all authors.Disclaimer The Publisher, Editors, and Editorial Board cannot be held respon-sible for the opinions and contents of publications contained in this journal.

The authors implicitly agree to their paper being peer-reviewed. All manuscripts will be reviewed by Editorial Board members who reserve the right to reject the manuscript without entering the review process in the case that the topic, the format or ethical aspects are inappropriate. In addition, the Editorial Board admits for submis-sion manuscripts previously submitted for publication to another journal but rejected with reviewers’ comments. In such cases, authors are requested to submit the scientific comments of the other journal and their point-by-point reply to the reviewers’ comments in the manuscript file. This will help to speed up the peer review process.Once accepted, all manuscripts are subjected to copy editing. If modifications to the manuscript are requested, the corresponding author should send to the online Editorial Office the revised manu-script under two separate files, one file containing the revised clean version and another containing both a letter with point-by-point responses to the reviewers’ comments and the revised version with corrections highlighted.Correction of proofs should be limited to typographical errors. Substantial changes in content (changes of title and authorship, new results and corrected values, changes in figures and tables) are subject to editorial review. Changes that do not conform to the journal’s style are not accepted. Corrected proofs must be sent back within 3 working days to the online Editorial Office of Minerva Anestesiologica. In case of delay, the editorial staff of the journal may correct the proofs on the basis of the original manuscript.Publication of manuscripts is free of charge. Colour figures and excessive alterations to proofs will be charged to the authors. Authors will receive instructions on how to order reprints and a copy of the manuscript in PDF.For further information about publication terms please contact the Editorial Office of Minerva Anestesiologica, Edizioni Minerva Medica, Corso Bramante 83-85, 10126 Torino, Italy - Phone +39-011-678282 - Fax +39-011-674502 - E-mail: [email protected].

Article types

Original papers are reports of original researches on the topics of interest to the journal and do not exceed 3000 words, 6 figures or tables, and 40 references. Papers reporting randomized control-led trials should be in accordance with the CONSORT statement (http://www. consort-statement.org).Review articles are comprehensive papers that outline current knowl-edge, usually submitted after prior consultation with the Editors and do not exceed 4000 words, 6 figures or tables, 70 references. Reviews should be in accordance with the PRISMA statement (www.prisma-statement.org).Experts’ opinion are papers reviewing the literature, usually invited by the Editor in Chief and do not exceed 3000 and 2000 words with 50 and 40 references respectively.Editorials are brief comments, commissioned by the Editor-in-Chief and express author’s opinion about published papers or topical issues and do not exceed 1000 words and 20 references.Letters to the Editor (Correspondence) are brief comments on articles published in the journal or with other topics of interest and do not exceed 500 words, 5 references and 1 figure or table.

Preparation of manuscripts

Text fileThe formats accepted are Word and RTF. The paper must contain title, authors’ details, notes, abstract, key words, text, references and

titles of tables and figures. Tables and figures should be submitted as separate files.

Title and authors’ details• Shorttitle(notexceeding100characters,spacesincluded),

with no abbreviations. • Firstnameandsurnameoftheauthors.• Affiliation(section,departmentand institution)ofeach

author.

Notes• Datesofanycongresswherethepaperhasalreadybeenpre-

sented. • Mentionofanyfundingorresearchcontractsorconflictof

interest. • Acknowledgements.• Name,address,e-mailofthecorrespondingauthor.

Abstract and key words Articles should include an abstract not exceeding 250 words. For original papers, the abstract should be structured as follows: background (status of knowledge and aim of the study), methods (experimental design, patients and interventions), results (what was found), conclusions (meaning of the study). Key words should refer to the terms from Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) of the Index Medicus. No abstracts are required for editorials or letters to the Editor.

Text

Units of measurement, symbols and abbreviations must conform to international standards. Measurements of length, height, weight and volume should be given in metric units (meter, kilogram, liter) or their decimal multiples. Temperatures must be expressed in degrees Celsius. Blood pressure must be expressed in millimeters of mer-cury. All hematological and clinicochemical measurements should be expressed in metric units using the International System of Units (IS). The use of unusual symbols or abbreviations is strongly discour-aged. The first time an abbreviation appears in the text, it should be preceded by the words for which it stands.For original papers the text must be subdivided into the following sections: introduction, materials and methods, results, discussion, conclusions. The introduction should describe the present state of knowledge on the subject and clearly state the aim of the research. The Materials and methods section should provide enough infor-mation to allow other researchers to reproduce results and should include a statistics section. Detailed statistical methodology must be described in order to enable the reader to evaluate and verify the results. Please report power analysis, randomized procedure, tests of normality, descriptive parameters, statistical tests and the probability level chosen for statistical significance. Drugs should be identified by their international non-proprietary name. If special equipment is used, then the manufacturer’s details (including town and country) should be given in parentheses. The Results section should describe the outcome of the study. Data presented in tables and graphs should not duplicate those presented in the text. Very large tables should be avoided. The Discussion should include the interpretation of the results obtained, an analysis of the limits of the study, and references to work by other authors. Conclusions should highlight the significance of the results for clinical practice and experimental research.

References

The list of references should only include works that are cited in the text and that have been published or accepted for publication (a copy of the acceptation letter can be requested) in journals cited in peer-reviewed Index Medicus journals. Websites can also be cited providing the date of access. Bibliographical entries in the text should be quoted using superscripted Arabic numerals. References must be set out in the standard format approved by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (www.icmje.org).Footnotes and endnotes must not be used in the preparation of references.

JournalsEach entry must specify the author’s surname and initials (list all authors when there are six or fewer; when there are seven or more, list only the first six and then “et al.”), the article’s original title, the name of the Journal (according to the abbreviations used by Index Medicus), the year of publication, the volume number and the number of the first and last pages. When citing references, please follow the rules for international standard punctuation carefully.Examples– Standard articleSutherland DE, Simmons RL, Howard RJ. Intracapsular technique of transplant nephrectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1978;146:951-2.– Organization as authorInternational Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals. Ann Int Med 1988;108:258-65.– Issue with supplementPayne DK, Sullivan MD, Massie MJ. Women’s psychological reactions to breast cancer. Semin Oncol 1996;23(1 Suppl 2): 89-97.

Books and mono graphsFor occasional publications the names of the Authors, the title, edi-tion, place, publisher and year of publication must be given.Examples– Books by one or more AuthorsRossi G. Manual of Otorhinolaryngology. Turin: Edizioni Minerva Medica; 1987. – Chapter from bookDe Meester TR. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. In: Moody FG, Carey LC, Scott Jones R, Ketly KA, Nahrwold DL, Skinner DB, editors. Surgical treatment of digestive diseases. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1986. p. 132-58. – Congress proceedingsKimura J, Shibasaki H, editors. Recent advances in clinical neu-rophysiology. Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of EMG and Clinical Neurophysiology; 1995 Oct 15-19; Kyoto, Japan. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1996. Titles of tables and figuresTitles of tables and legends of figures should be included both in the text file and in the file of tables and figures.File of tablesEach table should be submitted as a separate file. Formats accepted are Word and RTF. Each table must be typed correctly and prepared graphically in keeping with the page layout of the journal, numbered in Roman numerals and accompanied by the relevant title. Notes should be inserted at the foot of the table and not in the title. Tables should be referenced in the text sequentially. Tables should be self-explanatory and have a brief title and a legend if appropriate. File of figuresEach figure should be submitted as a separate file. Formats accepted: JPEG set at 300 dpi resolution preferred; other formats accepted are TIFF and PDF (high quality). Figures should be numbered in Arabic numerals and accompanied by the relevant legend. Figures should be referenced in the text sequentially.Histological photographs should always be accompanied by the magnification ratio and the staining method.If figures are in color, it should always be specified whether color or black and white reproduction is required.Authors of Original Articles are invited to submit figures for con-sideration as part of the cover design of an issue of the Journal. The Editorial Board will select from among the most interesting published Original Articles a figure they deem appropriate as a cover image for the issue in which the Original Article is published.

INSTRUCTIONS TO AUTHORS

For any fur ther in for ma tion vis it our web sitewww.minervamedica.it

271Organ donation after circulatory death in Italy? Yes we can!Nanni Costa A., Procaccio F.

274ORIGINAL ARTICLESDynamic view of postoperative pain evolution after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective observational studyGrosu I., Thienpont E., De Kock M., Scholtes J. L., Lavand’Homme P.

284Continuous vs. intermittent vancomycin therapy for Gram-positive infections not caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus AureusDuszynska W., Taccone F. S., Hurkacz M., Wiela-Hojenska A., Kübler A.

294Potential neurotoxicity of anesthetic drugs in young children: who cares? A survey among European anes-thetistsWeber F., Van Beek S., Scoones G.

257EDITORIALSIt is time for anesthetists to act as perioperative physi-ciansDeflandre E., Lacroix S.

259How should pediatric anesthesia respond on the dis-cussion about neurotoxicity in daily practice?Kaufmann J., Laschat M.

262The end of an era of pharmaconutrition and immu-nonutrition trials for the critically-ill patient?Festen B., Van Zanten A. R.

265Predictive scores for postoperative pulmonary compli-cations: time to move towards clinical practiceBall L., Pelosi P.

268How genomics can improve the management of septic patientsVincent J-L.

MINERVA ANESTESIOLOGICA

Vol. 82 March 2016 No. 3

CONTENTS

Vol. 82 - No. 3 MINERVA ANESTESIOLOGICA I

OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF ITALIAN SOCIETY OF ANESTHESIOLOGY, ANALGESIA,RESUSCITATION AND INTENSIVE CARE (SIAARTI)

ITALIAN JOURNAL OF ANESTHESIOLOGY AND ANALGESIAMONTHLY JOURNAL FOUNDED IN 1935 BY A. M. DOGLIOTTI

OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF ITALIAN SOCIETY OF ANESTHESIOLOGY, ANALGESIA,RESUSCITATION AND INTENSIVE CARE (S.I.A.A.R.T.I.)

CONTENTS

II MINERVA ANESTESIOLOGICA March 2016

301Comparison of blood culture and multiplex real-time PCR for the diagnosis of nosocomial sepsisDinç F., Akalin H., Özakin C., Sinirtaş M., Kebabçi N., Işçimen R., Kelebek Girgin N., Kahveci F.

310Time course of cytokines, hemodynamic and meta-bolic parameters during hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapyCoccolini F., Corbella D., Finazzi P., Brambillasca P., Benigni A., Prussiani V., Ceresoli M., Manfredi R., Poiasina E., Bertoli P., Catena F., Bianchetti A., Bontempelli M., Lorini L. F., Sonzogni V., Ansaloni L.

320REVIEWSImmunonutrients in critically ill patients: an analysis of the most recent literatureAnnetta M. G., Pittiruti M., Vecchiarelli P., Silvestri D., Caricato A., Antonelli M.

332How to optimize and use predictive models for post-operative pulmonary complicationsMazo V., Sabaté S., Canet J.

343The role of genomics to identify biomarkers and sign-aling molecules during severe sepsisDouglas J. J., Russell J. A.

359EXPERTS’ OPINION“Why can’t I give you my organs after my heart has stopped beating?”An overview of the main clinical, organisational, ethical and legal issues concerning organ donation after circulatory death in ItalyGiannini A., Abelli M., Azzoni G., Biancofiore G., Citterio F., Geraci P., Latronico N., Picozzi M., Procaccio F., Riccioni L., Rigotti P., Valenza F., Vesconi S., Zamperetti N.

369LETTERS TO THE EDITORRegional blocks for breast surgery: is it enough?Huercio I., Abad-Gurumeta A., Gilsanz F.

370Regional block for breast surgery: is it enough? Authors’ replyBouzinac A.

371Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in avalanche victim with deep hypothermia and circulatory arrestFacchetti G., Carbuglia N., Bucci V., Taraschi F., Paparoni S., Gyra A., Marinangeli F.

372Incidence and laryngoscopic grade of adult patients with Mallampati class zero airwayMiyoshi H., Kusunoki S., Nakamura R., Kawamoto M.

374TOP 50 MINERVA ANESTESIOLOGICA REVIEWERS

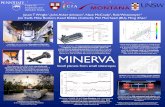

About the cover: the cover shows the Engström narcosis respirator model 200 projected around 1956 and produced by Gambro Engström AB. From the SIAARTI collection of medical devices at Viale dell’Università 11, Rome, Italy.

V O L U M E 8 2 · N o. 3 · M A R C H 2 0 1 6

Vol. 82 - No. 3 MiNerVa aNestesiologica 257

in this issue of Minerva Anestesiologica, grosu et al. have taken into account the evo-lution of pain after total knee arthroplasty (tKa).8 this original paper is interesting as it confirms the need for a holistic view of the patient. Indeed, the authors were interested in the patient’s pain (acute and chronic); but also, they measured the influence of pain on quality of life. This care corresponds to a method of the perioperative medicine.

As part of perioperative medicine, other ap-proaches could complement this patient’s care. Some examples are detailed hereafter. The preoperative anesthesia consultation should not only be used to identify high-risk patients (e.g. cardiac patients) but also should allow to track more efficiently “new risks” for patients. Among these, the anaesthetist can identify pa-tients with an increased likelihood of devel-oping postoperative chronic pain.9 Sessler et al. perfectly demonstrated that perioperative management conditioned patient’s outcome.7 For TKA, while the technique is not without risk, several authors have confirmed the su-periority of neuraxial anesthesia compared to general anesthesia in terms of postoperative infections, quality of life and 30-day mortal-ity.10-12 Postoperative pain should be treated quickly and adequately. Untreated acute pain is a major risk factor for chronicity of these.8, 13 However, some issues are still unresolved.14

Whether the patient will be dead or alive at the end of the operation is no longer the

matter. Intraoperative mortality has dramati-cally decreased since the early 1980s, even if variability could be observed between coun-tries.1-3 In an outstanding editorial, Grocott et al. have shown the need for anesthetists to in-tegrate the concept of perioperative medicine.4 This idea is not recent as in the late 1990s some visionary authors looked at the periop-erative medicine as the future of anesthesia.5, 6 as grocott et al. specify, many disciplines set one’s sight on perioperative medicine. How-ever, anesthetists are still the best placed to become leaders in this field. Indeed, we have an ideal combination of training, skills, knowl-edge, and experience.4

Therefore, a comprehensive view on the whole perioperative period is necessary. The perioperative management should start during the preoperative anaesthetic visit, follow with a “goal-directed patient-centred” intraopera-tive management and finish with postoperative care. This last one should not be limited to the recovery room, but will continue on the ward and even more after hospital discharge. There is growing evidence that our anesthesia influ-ences patient’s outcome, as surgical proce-dures do.7

E D I T O R I A L

It is time for anesthetists to act as perioperative physicians

eric DeFlaNDre 1-3 *, Simon LACROIX 3

1Cabinet Medical ASTES, Jambes, Belgium; 2University of Liege, Liege, Belgium; 3Clinique Saint-Luc of Bouge, Namur, Belgium*Corresponding author: Eric Deflandre, Chaussee de Tongres, 29, 4000 Liege-Rocourt, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected]

Anno: 2016Mese: MarchVolume: 82No: 3Rivista: Minerva anestesiologicaCod Rivista: Minerva Anestesiol

Lavoro: 10888-MAStitolo breve: ANAESTHETISTS SHOULD ACT AS PERIOPERATIVE PHYSICIANSprimo autore: DEFLANDREpagine: 257-8citazione: Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:000-000

Comment on p. 274

Minerva Anestesiologica 2016 March;82(3):257-8© 2015 EDIZIONI MINERVA MEDICAThe online version of this article is located at http://www.minervamedica.it

DeFlaNDre ANAESTHETISTS SHOULD ACT AS PERIOPERATIVE PHYSICIANS

258 MiNerVa aNestesiologica March 2016

4. Grocott MP, Pearse RM. Perioperative medicine: the fu-ture of anesthesia? Br J Anaesth 2012;108:723-6.

5. Van Aken H, Thomson D, Smith G, Zorab J. 150 years of anesthesia--a long way to perioperative medicine: the modern role of the anaesthesiologist. Eur J Anaesthesiol 1998;15:520-3.

6. rock P. the future of anesthesiology is perioperative medicine. anesthesiol clin 2000;18:495-513.

7. Sessler DI, Sigl JC, Kelley SD, Chamoun NG, Manberg PJ, Saager L, et al. Hospital stay and mortality are in-creased in patients having a “triple low” of low blood pressure, low bispectral index, and low minimum alveo-lar concentration of volatile anesthesia. anesthesiology 2012;116:1195-203.

8. Grosu I, Thienpont E, De Kock M, Scholtes JL, Lavand’homme P. Dynamic view of postoperative pain evolution after total knee arthroplasty: a prospec-tive observational study. Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82: 274-83.

9. Janssen KJ, Kalkman CJ, Grobbee DE, Bonsel GJ, Moons KG, Vergouwe Y. The risk of severe postoperative pain: modification and validation of a clinical prediction rule. Anesth Analg 2008;107:1330-9.

10. Liu J, Ma C, Elkassabany N, Fleisher LA, Neuman MD. Neuraxial anesthesia decreases postoperative systemic infection risk compared with general anesthesia in knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg 2013;117:1010-6.

11. Memtsoudis SG, Sun X, Chiu YL, Stundner O, Liu SS, Banerjee S, et al. Perioperative comparative effective-ness of anesthetic technique in orthopedic patients. An-esthesiology 2013;118:1046-58.

12. Lirk P, Hollmann MW. Outcome after regional anesthe-sia: weighing risks and benefits. Minerva Anestesiol 2014;80:610-8.

13. Lavand’homme P. The progression from acute to chronic pain. curr opin anaesthesiol 2011;24:545-50.

14. Allegri M, Clark MR, De Andres J, Jensen TS. Acute and chronic pain: where we are and where we have to go. Minerva Anestesiol 2012;78:222-35.

15. Allegri M, De Gregori M, Niebel T, Minella C, Tinelli c, govoni s, et al. Pharmacogenetics and postoperative pain: a new approach to improve acute pain management. Minerva Anestesiol 2010;76:937-44.

16. Vetter TR, Goeddel LA, Boudreaux AM, Hunt TR, Jones KA, Pittet JF. The Perioperative Surgical Home: how can it make the case so everyone wins? BMC Anesthesiology 2013;13:6.

17. Martin J, Cheng D. Role of the anesthesiologist in the wider governance of healthcare and health economics. Can J Anaesth 2013;60:918-28.

18. Walder B, Maillard J, Lubbeke A. Minimal clinically im-portant difference: a novel approach to measure changes in outcome in perioperative medicine. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015;32:77-8.

19. Hyder JA, Niconchuk J, Glance LG, Neuman MD, Cima rr, Dutton rP, et al. What can the national quality forum tell us about performance measurement in anesthesiol-ogy? Anesth Analg 2015;120:440-8.

20. Wacker J, Staender S. The role of the anesthesiologist in perioperative patient safety. curr opin anaesthesiol 2014;27:649-56.

In the future, the pharmacogenetic approach might then bring some answers.15

Anesthesia practice has profoundly im-proved in terms of safety, activities and per-spectives.3 This shows how anesthesia is able to move forward and how it tries to meet the requirements of our current society. Another change in practice will be achieved by the implementation of the Perioperative Surgical Home.16 This comprehensive reform will aim to improve the quality of care (patient-cen-tred); but it will also lead to an economy of means. For some authors, the access of anes-thetists to the wider governance of healthcare and health economics (both within the hospital and in new non-hospital structures) will have a positive economic impact.17

For all of these changes, we will never for-get to measure and implement practice quality parameters.18, 19 For the time being, we cannot manage what we do not measure. “Primum non nocere, deinde curare”: outcome quality indicators are essential. The role of the anaes-thetist in perioperative patient safety is defi-nitely inescapable.20

Anesthesia is moving outside the operative room. If anesthesia succeeds in imposing one-self in perioperative period, it will gain cred-ibility towards patient and other physicians. Conversely, if we spoil this opportunity, others will jump at it.

References

1. Lienhart A, Auroy Y, Pequignot F, Benhamou D, Warsza-wski J, Bovet M, et al. Survey of anesthesia-related mortality in France. Anesthesiology 2006;105:1087- 97.

2. Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, Pelosi P, Metnitz P, spies c, et al. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet 2012;380:1059-65.

3. Clergue F. The challenges of anesthesia for the next decade: the Sir Robert Macintosh Lecture 2014. Eur J anaesthesiol 2015;32:223-9.

Conflicts of interest.—The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.Article first published online: September 17, 2015. - Manuscript accepted: September 16, 2015. - Manuscript received: August 21, 2015.(Cite this article as: Deflandre E, Lacroix S. It is time for anesthetists to act as perioperative physicians. Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:257-8)

Vol. 82 - No. 3 MiNerVa aNestesiologica 259

are the threat to baby brains” 2 certainly fueled the emotional component of the debate. the impact of this topic in pediatric anesthesia is very noticeable during daily practice and will undoubtedly remain prevalent in the future. apart from the increasing anxiety of parents and other medical specialties, it must be as-sumed that lawsuits concerning disabled pre-mature children will increasingly focus on the anesthetic care.

in this issue of Minerva Anestesiologica, a survey by Frank Weber et al. tackles the im-pact the discussion about neurotoxicity has on pediatric anesthesiologists.3 they focused on the thoughts of the colleagues and if they have changed their daily practice as a conse-quence. By contacting the participants in the aPricot trial (www.esahq.org/apricot), they reached a large, selected group of scien-tifically interested pediatric anesthesiologists from all over europe. this study is able to add valuable information to assess the influence of the current knowledge and discussion about neurotoxicity on the daily routine of pediatric anesthesia specialists in europe.

surprisingly, only half of the participants (mostly specialists in anesthesia) felt them-selves well informed about the issue of neu-rotoxicity in pediatric anesthesia. two thirds of the participants reported that neurotoxicity affected their daily practice, in most of the

the current discussion of the impact of nar-cotics on the neurological development

of neonates and small children is a result of animal studies. invariably, the exposure to an-esthetic agents in these studies was not consis-tent with routine clinical practice and the ex-perimental setup a consequence of the desire and need to obtain a significant result in order to ensure publication.

only fragmented and contradictory evidence is available for humans, however, various sci-entific publications call for a “heightened level of concern” on this issue.1 Furthermore, the non-scientific media has processed this topic providing various articles and editorials with alarming headlines such as “Does anesthesia make your child stupid?”. Both the academic and lay press create the impression of this be-ing a statement rather than a question. a re-cent alternative view editorial highlighted that maintaining homeostasis (avoiding arterial hy-potension, hypocapnia, hyponatremia and hy-poglycemia) may be even more important for the neurodevelopment of premature babies. it also suggested that these imbalances are too often tolerated during daily anesthetic prac-tice. although this message is providing a bal-ance and is absolutely correct, the distinctive headline “Anesthetists rather than anesthetics

E D I T O R I A L

How should pediatric anesthesia respond on the discussion about neurotoxicity in daily practice?

Jost KaUFMaNN 1, 2 *, Michael lascHat 1

1Department of Pediatric Anesthesia, Children’s Hospital of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; 2Faculty of Health, University Witten/Herdecke, Witten, germany*Corresponding author: Jost Kaufmann, Department of Pediatric Anesthesia, Children’s Hospital of Cologne, Amsterdamer Str. 59, D-50735 Cologne, Germany. E-mail: [email protected]

Anno: 2016Mese: MarchVolume: 82No: 3rivista: Minerva anestesiologicacod rivista: Minerva anestesiol

Lavoro: 10897-MAStitolo breve: PEDIATRIC ANESTHESIA AND NEUROTOXICITY IN DAILY PRACTICEprimo autore: KaUFMaNNpagine: 259-61citazione: Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:000-000

comment on p. 294

Minerva Anestesiologica 2016 March;82(3):259-61© 2015 EDIZIONI MINERVA MEDICAthe online version of this article is located at http://www.minervamedica.it

KaUFMaNN PEDIATRIC ANESTHESIA AND NEUROTOXICITY IN DAILY PRACTICE

260 MiNerVa aNestesiologica March 2016

4. this institutional competence also re-quires the treatment of vulnerable babies with-in well-prepared structures; this necessitates adoption of institution-wide teaching and edu-cation of their special needs;

5. pediatric anesthesia should be performed or supervised by trained pediatric anesthesi-ologists only. it is well accepted that this group can provide stability and will result in less complications than someone only occasionally treating such patients;

6. finally, pediatric anesthesiologists should respond and be recognized as competent partners for perioperative medicine of a very special patient group. as such they must be involved in the planning of the necessity and best time point for elective surgery to reach the best possible compromise between surgi-cal interests and the issue of an optimal patient safety.

Frank Weber et al. defend a “wait-and-see” kind of approach concerning the influence of the daily practice due to the debate on neuro-toxicity and supported this by valid evidence and an unexcited but consequent questioning of daily practice. this is actually the only rea-sonable way forward. We share their desire for more evidence from future clinical prospective trials. We would like to extend this request to an increased use and evaluation of comprehen-sive cardiovascular and cerebral monitors (e.g. Nirs). We need to get close to an optimal ho-meostasis until now the ‘other’ important but less recognized threat to baby brains.

References

1. rappaport Ba, suresh s, Hertz s, evers as, orser Ba. anesthetic neurotoxicity — clinical implications of ani-mal models. N Engl J Med 2015;372:796-7.

2. Weiss M, Bissonnette B, engelhardt t, soriano s. an-esthetists rather than anesthetics are the threat to baby brains. Pediatr Anesth 2013;23:881-2.

3. Weber F, van Beek s, scoones g. Potential neurotoxicity of anaesthetic drugs in young children: who cares? a sur-vey among european anaesthetists. Minerva anestesiol 2016;82:294-303.

4. anand KJ. clinical importance of pain and stress in pre-term neonates. Biol Neonate 1998;73:1-9.

5. Bouza H. the impact of pain in the immature brain. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2009;22:722-32.

6. Porter FL, Grunau RE, Anand KJ. Long-term effects of pain in infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1999;20:253-61.

cases only affecting the preoperative plan-ning.

Just 18% reported changes in their individu-al practice of anesthesia. a remarkably portion of one third of the participant declared an an-esthesia without the use of anesthetics (high-dose opioids only and muscle relaxant drugs) to be ethically justifiable. The intention is to avoid cardiovascular instability in those vul-nerable patients. there is good evidence from neonatal intensive care that inadequate seda-tion and analgesia is harmful for developing babies both physically 4, 5 (increasing rate of cerebral hemorrhage) and psychologically 6, 7 (life-time reduced stress and pain-tolerance). this statement, however, does not answer the question, if adequate pain and stress relieve can be achieved by opioids only (for instance remifentanil) or not. At this point, no final judgment can be given and one should not create the impression of being able to achieve this. It just remains to note that some experts perform anesthesia without sedative drugs and some do not.

Modern pediatric anesthesia should be able to achieve both adequate depth of anesthesia and pain control as well as stable cardiovascu-lar conditions. as long as essential questions in neurodevelopment are not answered con-clusively, pediatric anesthesiologists should rely on what is known and can be summarized clearly:

1. local anesthesia should be used wherever applicable and possible (e.g. as a sole method); this allows the amount of sedative medication to be kept low but still achieving clinically ad-equate depth of anesthesia.

2. the focus on homeostasis should result in proper monitoring using all modern methods that are available (e.g. generous use of inva-sive blood pressure measurement and transcu-taneous capnography);

3. a compromised cardiovascular situation must be addressed immediately with appro-priate fluid therapy and catecholamines. This requires prior preparation and practical knowl-edge (e.g. a list how to prepare practicable di-lutions and weight-dependent drug-rates). this is institutional competence;

PEDIATRIC ANESTHESIA AND NEUROTOXICITY IN DAILY PRACTICE KaUFMaNN

Vol. 82 - No. 3 MiNerVa aNestesiologica 261

to increased pain sensitivity in later childhood? Pain 2005;114:444-54.

7. Peters JW, Schouw R, Anand KJ, van Dijk M, Duiv-envoorden HJ, Tibboel D. Does neonatal surgery lead

Conflicts of interest.—The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.Article first published online: October 20, 2015. - Manuscript accepted: October 19, 2015. - Manuscript received: August 29, 2015.(Cite this article as: Kaufmann J, laschat M. How should pediatric anesthesia respond on the discussion about neurotoxicity in daily practice? Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:259-61)

262 Minerva anestesiologica March 2016

oxidant capacity and immunoparalysis during their icU stay, it seems attractive to modulate these responses. However, in daily practice the actual immune-status in individual patients is rarely measured. in addition, to demonstrate beneficial effects these immune-modulating nutrients should induce a combination of mul-tiple actions such as reducing an overactive inflammatory response, restoring reduced an-tioxidant capacity and preventing occurrence of immunoparalysis. From a basic science per-spective this may be a wrong assumption and has never been proven for single nutrients and thus can be considered to good to be true.

it has been suggested that low baseline plasma glutamine levels reflect conditional deficiency and are associated with increased mortality. However, recently at least 12 stud-ies challenging aspects of this hypothesis have been summarized.5 at discharge high plasma glutamine levels are associated with increased long-term (1-year) mortality.6 there is a trend that glutamine supplementation confers more harm in patients with higher baseline gluta-mine levels.4 recently several researchers have suggested that glutamine supplemen-tation may be a maladaptive response to an adaptive process.7, 8

With respect to fish oil we lack studies that show an association of low baseline eicosa- pentaenoic acid (ePa) and docosahexaenoic

For decades trials have been performed to study effects of enriched or supplemented

(par)enteral nutrition with immune-modulat-ing macronutrients (e.g. glutamine, arginine and fish-oil) and micronutrients (e.g. selenium, vitamin c, vitamin e, and zinc) versus stan-dard feeds on outcome of ICU patients.1 this concept is also known as pharmaconutrition, suggesting specific nutritional components may exert pharmacological beneficial effects.

In this issue of Minerva Anestesiologica, annetta et al. have reported results of a re-view of the latest evidence-based information on immunonutrition, concluding that there is no convincing evidence that immunonutrients may be beneficial for critically-ill patients.2 they suggest that these substances invariably increase costs of health care and may be unsafe or even harmful in some subgroups, particu-larly in septic patients.3, 4 Therefore, currently routine administration of immune-nutrients (glutamine, arginine, omega-3 fatty acids and selenium) cannot be recommended in the crit-ically-ill.

Why do the latest large multicenter trials not show benefits and even show harm in contrast with earlier observations?

As many ICU patients encounter phases of systemic inflammatory response, reduced anti-

E D I T O R I A L

The end of an era of pharmaconutrition and immunonutrition trials for the critically-ill patient?

Barbara FESTEN, Arthur R. van ZANTEN *

Department of Intensive Care, Gelderse Vallei Hospital, Ede, The Netherlands*Corresponding author: Arthur R. van Zanten, Hospital Medical Director, Department of Intensive Care, Gelderse Vallei Hospital, Ede, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected]

Anno: 2016Mese: MarchVolume: 82No: 3Rivista: Minerva anestesiologicaCod Rivista: Minerva Anestesiol

Lavoro: titolo breve: PHARMACONUTRITION AND IMMUNONUTRITION TRIALSprimo autore: FESTENpagine: 262-4citazione: Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:262-4

comment on p. 320.

Minerva Anestesiologica 2016 March;82(3):262-4© 2015 EDIZIONI MINERVA MEDICAThe online version of this article is located at http://www.minervamedica.it

PHarMaconUtrition anD iMMUnonUtrition trials FESTEN

vol. 82 - no. 3 Minerva anestesiologica 263

lected: ICU patients do not consistently have low baseline glutamine levels.5 Moreover, glu-tamine deficiency is not associated with sever-ity of illness (APACHE–II scores).11

not only low, but also high baseline gluta-mine levels are associated with increased mor-tality.10 in sepsis probably only high glutamine levels are related to mortality, not low levels.11

Based on data from the REDOXS and Meta-Plus studies it was suggested that after gluta-mine supplementation specifically patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, re-nal failure and medical patients with circulato-ry failure were at high-risk for higher 6-month mortality.4, 12

selenium has been studied in randomized clinical trials in critically-ill patients both as monotherapy or in antioxidant cocktails. Me-ta-analyses have suggested benefits with sele-nium therapy in the most severely ill patients. in the largest study on glutamine and antioxi-dants, the REDOXS study, no improvements in clinical outcomes with antioxidants were found and harm was shown in patients with renal dysfunction.11 in addition, the MetaPlus study investigators found increased 6-month mortality in medical patients when provided extra glutamine and selenium in enriched en-teral nutrition. recently, it was suggested that effects of selenium and glutamine may be de-pendent on the dose, the route of administra-tion, and whether administered in combination or with other nutrients and the specific patient population studied.5

Over time benefits of glutamine supple-mentation in studies have disappeared. since 2003 no positive studies on mortality have been published.13 Most beneficial results on glutamine were reported in older single-cen-ter studies. considering exclusive parenteral glutamine supplementation multicenter rcts show increased mortality, in contrast to single center studies showing reduced mortality.14, 15 typically multicenter trials are valued as more important than single-center studies.

in some studies non-isonitrogenous inter-ventions have been studied.5 Benefits of glu-tamine supplementation in these studies may be due to higher protein intake. In addition,

(DHa) levels and worse outcome. Plasma EPA-levels after fish oil supplementation in critically-ill rarely have been studied. there-fore, we cannot be sure whether levels are low in critically-ill patients, and whether supple-mentation normalizes plasma levels and in-duces beneficial or negative effects. This may provide an explanation that with respect to fish oil supplementation divergent results have been published.

supplemental glutamine does not reduce the endogenous production from the muscle in critically-ill patients and muscle production of glutamine in the critically-ill is not maxi-mized. these observations are not concordant with a conditional deficiency hypothesis.5

Free drugs induce pharmacological effects. Maybe we should study associations of im-mune-modulating nutrients taking into account aspects of protein-binding and third-spacing and no longer rely on total plasma levels. Fur-thermore, we are unaware of up-regulation or down-regulation of (post)receptor and other intracellular metabolic pathways for specific immune-modulating nutrients during critical illness.

It is questionable whether reference plasma levels and recommended daily allowances can be extrapolated to critically-ill patients. vita-min D supplementation was recently studied in icU patients. amrein and collaborators used high dose supplementation once at a dose of 540,000 IU followed by monthly maintenance doses of 90,000 IU for 5 months. It did not re-duce hospital length of stay, hospital mortality, or 6-month mortality. in the severe vitamin D deficiency subgroup (≤12 ng/mL) hospital mortality was significantly lower, but this find-ing should be considered hypothesis generat-ing and requires further study. Remarkably, many patients on high dose supplementation did not demonstrate normalized plasma levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D.9 We lack dose-find-ing studies for almost all immune-modulating nutrients for critically-ill patients.

recent summarized data on glutamine sug-gested we have studied the wrong subgroups of critically-ill patients. Those patients with low glutamine levels were frequently not se-

FESTEN PHarMaconUtrition anD iMMUnonUtrition trials

264 Minerva anestesiologica March 2016

4. Van Zanten AR, Sztark F, Kaisers UX, Zielmann S, Fel-binger TW, Sablotzki AR, et al. High-protein enteral nutrition enriched with immune-modulating nutrients vs standard high-protein enteral nutrition and nosocomial infections in the ICU: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:514-24.

5. Van Zanten AR. Glutamine and antioxidants: status of their use in critical illness. curr opin clin nutr Metab Care 2015;18:179-86.

6. Smedberg M, Grass JN, Pettersson L, Norberg Å, Rooy-ackers O, Wernerman J. Plasma glutamine concentra-tion after intensive care unit discharge: an observational study. Crit Care 2014;18:677.

7. van den Berghe g. low glutamine levels during criti-cal illness--adaptive or maladaptive? N Engl J Med 2013;368:1549-50.

8. Van Zanten AR, Hofman Z, Heyland DK. Consequenc-consequenc-es of the REDOXS and METAPLUS Trials: the end of an era of glutamine and antioxidant supplementation for critically ill patients? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2015;39:890-2.

9. Amrein K, Schnedl C, Holl A, Riedl R, Christopher KB, Pachler C, et al. Effect of high-dose vitamin D3 on hospital length of stay in critically ill patients with vi-tamin D deficiency: the VITdAL-ICU randomized clini-cal trial. JAMA 2014;312:1520-30. Erratum in: JAMA 2014;312:1932.

10. Rodas PC, Rooyackers O, Hebert C, Norberg A, Werner-man J. Glutamine and glutathione at ICU admission in relation to outcome. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:591-7.

11. Heyland DK, Elke G, Cook D, Berger MM, Wischmeyer Pe, albert M, et al.; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Glutamine and Antioxidants in the critically ill patient: a post hoc analysis of a large-scale randomized trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2015;39:401-9.

12. Manzanares W, Langlois PL, Heyland DK. Pharmaconu-trition with selenium in critically ill patients: what do we know? Nutr Clin Pract 2015;30:34-43.

13. Fadda V, Maratea D, Trippoli S, Messori A. Temporal trend of short-term mortality in severely ill patients re-ceiving parenteral glutamine supplementation. clin nutr 2013;32:492-3.

14. Wischmeyer PE, Dhaliwal R, McCall M, Ziegler TR, Heyland DK. Parenteral glutamine supplementa-tion in critical illness: a systematic review. Crit Care 2014;18:R76.

15. Pasin L, Landoni G, Zangrillo A. glutamine and antioxidants in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2013;369:482-4.

16. Buijs N, Brinkmann SJ, Oosterink JE, Luttikhold J, Schierbeek H, Wisselink W, et al. intravenous glutamine supplementation enhances renal de novo arginine syn-thesis in humans: a stable isotope study. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:1385-91.

glutamine can be metabolized to arginine.16 in sepsis patients, arginine supplementation has been associated with increased mortality, possibly by inducing nitric oxide production. Thus, interfering with the glutamine metabolic pathway may potentially lead to unpredictable arginine production.

In conclusion, as the first dictum in medicine is to do no harm, we should now abandon the concept of immunonutrition or pharmaconutri-tion for lack of benefits and serious safety con-cerns, at least until the proper basic research has clarified the potential harmful pathways.8 Moreover, we have to design studies that select patients in homogeneous subgroups of ICU pa-tients, with real deficiencies and not those with adaptive responses. control groups have to be selected carefully, and evidence from small single centers should lead to confirmative pro-spective multicenter trials. critical care nutri-tion has arrived in the era of evidence-based medicine. Supposed beneficial concepts have to be prospectively tested. the latest trials as summarized by annetta et al.,2 in our opinion should lead to revised guidelines downgrading immunonutrition and pharmaconutrition for use in critically-ill patients.

References 1. Hegazi RA, Wischmeyer PE. Clinical review: optimizing

enteral nutrition for critically ill patients--a simple data-driven formula. Crit Care 2011;15:234.

2. annetta Mg, Pittiruti M, vecchiarelli P, silvestri D, cari-cato a, antonelli M. immunonutrients in critically ill pa-tients: an analysis of the most recent literature. Minerva Anestesiol 2015;81:323-34.

3. Heyland D, Muscedere J, Wischmeyer PE, Cook D, Jones G, Albert M, et al.; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. A randomized trial of glutamine and antioxidants in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1489-97.

Funding.—Inclusion fees for patients in the MetaPlus trial from Nutricia were paid to the local ICU research foundation.Conflicts of interest.—Dr. Festen declares no conflict of interest. Dr. van Zanten has received honoraria for advisory board meetings, and lectures, and travel expenses from Abbott, Baxter, Danone, Fresenius Kabi, Nestlé, Novartis, and Nutricia.Article first published online: July 28, 2015. - Manuscript accepted: July 23, 2015. - Manuscript revised: July 22, 2015. - Manuscript received: May 27, 2015.(Cite this article as: Festen B, van Zanten AR. The end of an era of pharmaconutrition and immunonutrition trials for the critically-ill patient? Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:262-4)

Vol. 82 - No. 3 MiNerVa aNestesiologica 265

thors report a useful classification of the risk factors identified by several studies: patient versus procedure-related and modifiable ver-sus non-modifiable factors. The most intrigu-ing message of this review is that two main pitfalls hamper the translation in the clinical practice of the knowledge derived from studies on predictive scores: first, describing and ex-plaining statistical associations does not nec-essarily mean predicting outcome; second, the physician needs reliable and validated tools to modify the clinical practice in order to reduce incidence of PPCs.

Every year more than two hundreds millions major surgical procedures are performed, with a significant burden in terms of public health costs and more than one million patients devel-oping complications,3 with PPCs being a major determinant.4 Thus, risk stratification for PPCs could be a first important step toward a reduc-tion in surgery-related mortality, which has been shown to be higher than expected in large prospective multicenter studies such as the Eu-ropean Surgical Outcomes Study (EuSOS).5

The single risk factors identified by the dif-ferent cohort studies are not univocal. The most reported ones are advanced age,2, 6, 7 low preoperative SpO2,2 recent respiratory infec-tion,2 preoperative anemia,2 type or setting of surgery,2, 6, 8 duration of surgery,2, 7 high Amer-

in this issue of Minerva Anestesiologica, Mazo et al.1 present a systematic review and

in-depth analysis concerning the development and clinical application, in form of scores, of predictive models for postoperative pulmo-nary complications (PPC). The authors pro-pose an articulate methodological reflection on the design, validation and implementation of these clinical scores. The attention is ini-tially focused on statistical modeling, discuss-ing the appropriateness of choice of potential predictors of outcome, as well as the relevance of external validation of predictive scores. In anesthesia, there is particular interest towards simple clinical predictors of PPCs that can be assessed at the pre-operative visit. In this paper, Mazo et al. underline how researchers should make efforts to translate descriptive explanatory models into useful tools for the clinical practice. The authors report that, sur-prisingly, despite the high incidence of PPCs, limited efforts were made by the scientific community to validate scores to predict their incidence: since 2000, 1519 studies in differ-ent fields of medicine included prospective ex-ternal validation of risk scores, of them only 40 concerning the postoperative period, and only one regarding PPCs incidence.2 the au-

E D I T O R I A L

Predictive scores for postoperative pulmonary complications:

time to move towards clinical practiceLorenzo BALL, Paolo PELOSI*

Department of Surgical Sciences and Integrated Diagnostics, IRCCS AOU San Martino-IST, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy*Corresponding author: Paolo Pelosi, Department of Surgical Sciences and Integrated Diagnostics, IRCCS AOU San Martino-IST, University of Genova, Largo Rosanna Benzi 8, 16131 Genova, Italy. E-mail: [email protected]

Anno: 2016Mese: MarchVolume: 82No: 3Rivista: Minerva AnestesiologicaCod Rivista: Minerva Anestesiol

Lavoro: 10788-MAStitolo breve: PREDICTIVE SCORES FOR PPCprimo autore: BALLpagine: 265-7citazione: Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:265-7

Comment on p. 332.

Minerva Anestesiologica 2016 March;82(3):265-7© 2015 EDIZIONI MINERVA MEDICAThe online version of this article is located at http://www.minervamedica.it

BALL PREDICTIVE SCORES FOR PPC

266 MiNerVa aNestesiologica March 2016

along with a careful respiratory monitoring 14 seems to be a preventive measure that any cli-nician could and should implement.

Several preoperative interventions have been suggested to reduce the incidence of PPCs: smoking cessation, correction of ane-mia, delaying surgery in patients with recent respiratory infection, choosing shorter surgical procedures in high-risk patients. Concerning postoperative management, different measures have been tested or are under investigation, in-cluding but not limited to postoperative incen-tive spirometry or respiratory physiotherapy, bundle interventions like the I-COUGH proto-col15 and postoperative short-term CPAP. Most of these strategies have not been systemati-cally tested on large prospective randomized trials: this opens a new space for predictive scores. In fact, patient selection based on vali-dated predictive scores should be considered in the design of all future studies, in order to rapidly achieve an adequate level of evidence on preventive measures, identifying sub-sets of high-risk patients potentially benefiting from the different approaches.

The methodological robustness advocated by Mazo and coworkers1 should be an epitome for research practice, not limited to the field of prevention of postoperative pulmonary com-plications. Figure 1 illustrates applications of predictive scores for PPCs in clinical activ-ity and research. Concerning research, scores can help in the design of smaller pilot studies focusing on high-risk patients, and in wider cohorts are useful to match or stratify patient subgroups according to their risk class.

Reducing complications, hospital length of stay and ultimately patient mortality after sur-gery will be a challenge in the next decades. A battle that must be fought by researchers alongside with first-line clinicians, with the consciousness that every single measure that we adopt in the clinical routine has a small impact on percent incidence of complications but, given the high and growing number of sur-gical interventions performed every day, this translates in thousands of lives that could be potentially saved: it is time to move towards the clinical practice!

ican Society of Anesthesiologists class,6, 8 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,6,8 con-gestive heart failure,6, 8 perioperative nasogas-tric tube placement7 and positive cough test.7 Not all of these factors are easy to modify, thus the road to clinical application of predictive scores splits in two interconnected paths: risk assessment and tailored patient management. A quick risk stratification seems a reasonable way for a better resource allocation,9 choosing at the preoperative visit which patients could benefit from a planned admission to the inten-sive care unit, the postanesthesia care unit or the direct admission to the surgical ward. Peri-operative care medicine is a growing branch of anesthesiology, investigating different in-terventions that can modify the course of the occurrence of postoperative complications. It has been widely demonstrated that mechanical ventilation itself can initiate lung injury also in healthy lungs, providing the rationale for applying protective ventilation strategies also in the operating room,10, 11 and a recent meta-analysis concluded that the routine application of low tidal volumes should be considered for all patients,12 while the role of routine high PEEP plus recruitment maneuvers alone was reshaped by a large randomized trial.13 Thus, adopting protective ventilatory strategies12

Figure 1.—Potential applications of scores for predicting postoperative pulmonary complications.

PREDICTIVE SCORES FOR PPC BALL

Vol. 82 - No. 3 MiNerVa aNestesiologica 267

tive respiratory complications. Anesthesiology 2013; 118:1276-85.

9. Mazo V, Sabate S, Canet J. A race against time: planning postoperative critical care. Anesthesiology 2013;119:498-500.

10. Eikermann M, Kurth T. Apply Protective Mechanical Ventilation in the Operating Room in an Individualized Approach to Perioperative Respiratory Care. Anesthesi-ology 2015;123:12-4.

11. Guldner A, Kiss T, Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SN, Canet J, Spieth PM, et al. Intraoperative Protective Mechani-cal Ventilation for Prevention of Postoperative Pulmo-nary Complications: A Comprehensive Review of the Role of Tidal Volume, Positive End-expiratory Pres-sure, and Lung Recruitment Maneuvers. Anesthesiology 2015;123:692-713.

12. Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SN, Barbas CS, Beiderlinden M, Biehl M, Binnekade JM, et al. Protective versus Conven-tional Ventilation for Surgery: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2015;123:66-78.

13. Hemmes SN, Gama de Abreu M, Pelosi P, Schultz MJ. High versus low positive end-expiratory pressure dur-ing general anaesthesia for open abdominal surgery (PROVHILO trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;384:495-503.

14. Ball L, Sutherasan Y, Pelosi P. Monitoring respiration: what the clinician needs to know. Best Pract Res Clin An-aesthesiol 2013;27:209-23.

15. Cassidy MR, Rosenkranz P, McCabe K, Rosen JE, McAneny D. I COUGH: reducing postoperative pulmo-nary complications with a multidisciplinary patient care program. JAMA Surg 2013;148:740-5.

References 1. Mazo V, Sabaté S, Canet J. How to optimize and use pre-

dictive models for postoperative pulmonary complica-tions. Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:335-45.

2. Mazo V, Sabate S, Canet J, Gallart L, de Abreu MG, Bel-da J, et al. Prospective external validation of a predictive score for postoperative pulmonary complications. Anes-thesiology 2014;121:219-31.

3. Weiser TG, Makary MA, Haynes AB, Dziekan G, Berry WR, Gawande AA, et al. Standardised metrics for global surgical surveillance. Lancet 2009;374:1113-7.

4. Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SN, Barbas CS, Beiderlinden M, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Futier E, et al. Incidence of mortality and morbidity related to postoperative lung injury in patients who have undergone abdominal or tho-racic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:1007-15.

5. Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, Pelosi P, Metnitz P, spies c, et al. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet 2012;380:1059-65.

6. Smetana GW, Lawrence VA, Cornell JE, American Col-lege of P. Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:581-95.

7. McAlister FA, Bertsch K, Man J, Bradley J, Jacka M. In-cidence of and risk factors for pulmonary complications after nonthoracic surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:514-7.

8. Brueckmann B, Villa-Uribe JL, Bateman BT, Grosse-Sundrup M, Hess DR, Schlett CL, et al. Development and validation of a score for prediction of postopera-

Conflicts of interest.—The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.Article first published online: September 3, 2015. - Manuscript accepted: July 31, 2015. - Manuscript revised: July 23, 2015. - Manu-script received: July 2, 2015.(Cite this article as: Ball L, Pelosi P. Predictive scores for postoperative pulmonary complications: time to move towards clinical practice. Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:265-7)

268 Minerva anestesiologica March 2016

different combinations will likely be needed to fulfil different roles. Moreover, no test will ever be perfect and all biomarkers will have to be used in conjunction with other clinical elements.

As highlighted by Douglas and Russell,4 biomarkers have three key potential roles in sepsis: diagnosis, prediction of response to therapy, and prognosis. Accurate recognition of the presence of an infection is vital, espe-cially if the infection is associated with some form of organ dysfunction (what we call “sep-sis”). In these conditions, early diagnosis, al-lowing rapid, appropriate therapy to be started, is of utmost importance to prevent complica-tions and deterioration into multiple organ failure and death.5, 6 Importantly, diagnostic techniques can involve not only identifying the presence of infection, but also ruling out infec-tion in a patient with suggestive clinical signs and symptoms, but who may not need antibi-otics. Biomarkers can also help to separate vi-ral from bacterial infections, or may indicate that coverage of fungal pathogens is necessary (or not, so avoiding unnecessary antifungal therapy). Some techniques, for example using microbial DNA, can also help more rapidly identify specific microorganisms than conven-tional microbiological techniques.7 although this approach is not perfect and cannot (yet) replace traditional culture and sensitivity test-

our understanding of the molecular mecha-nisms of sepsis has advanced immeasur-

ably since Schottmueller first made the link 100 years ago between infection and the host response stating that “Sepsis is present if a focus has developed from which pathogenic bacteria, constantly or periodically, invade the blood stream in such a way that this causes subjective and objective symptoms”.1 We now know that sepsis, the dysregulated host response to infection,2 is a highly complex reaction that involves the expression of hun-dreds of genes and the repression of a similar number.3 Yet, there is still much we do not un-derstand. In this issue of Minerva Anestesiolo-gica, Douglas and Russell, established experts in this field, provide a comprehensive article 4 covering some of the newly developed (and developing) genomics technology that will help unravel further the complexities of sepsis, and importantly what impact this new knowl-edge may have on our ability to more effec-tively and rapidly diagnose and treat sepsis by the identification and validation of biomarkers.

Given the multifaceted nature of the sepsis response, the chances of finding a single sep-sis (bio)marker are remote; this concept is too naïve. Rather, combinations of biomarkers will be of greater value and more reliable, and

E D I T O R I A L

How genomics can improve the management of septic patients

Jean-louis vincent

Department of Intensive Care, Erasme Hospital, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, BelgiumCorresponding author: Jean-Louis Vincent, Department of Intensive Care, Erasme Hospital, Route de Lennik 808, 1070 Brussels, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected]

Anno: 2016Mese: MarchVolume: 82No: 3Rivista: Minerva AnestesiologicaCod Rivista: Minerva Anestesiol

Lavoro: 10854-MAStitolo breve: GENOMICS IN SEPSIS MANAGEMENTprimo autore: VINCENTpagine: 268-70citazione: Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:000-000

Comment on p. 343.

Minerva Anestesiologica 2016 March;82(3):268-70© 2015 eDiZioni Minerva MeDicaThe online version of this article is located at http://www.minervamedica.it

GENOMICS IN SEPSIS MANAGEMENT vincent

Vol. 82 - No. 3 Minerva anestesiologica 269

most from activated protein C,9 although this observation came too late for this drug, which is no longer available.10 Nevertheless, related compounds will likely appear in the future and may benefit from this approach. Improved use of steroids is another example. Wong et al. re-vealed how steroids can modify gene expres-sion in septic patients 11 and later showed how this approach could help to identify patients in septic shock who may benefit from steroids, or be harmed by them.12

Mortality rates for patients with sepsis re-main unacceptably high, yet results of studies of new therapies in patients with sepsis have been disappointing. The field of genomics is opening up a whole new means of diagnosing, prognosticating, and directing treatment in sepsis, which will necessitate a change in our approach to the management of these patients and to trial design. The review by Douglas and russell 4 provides an excellent base to help understand current use of this technology and explore future applications.

References

1. Schottmueller H. Wesen und Behandlung der Sepsis. Inn Med 1914;31:257-80.

2. Vincent JL, Opal S, Marshall JC, Tracey KJ. Sepsis defi-nitions: time for change. Lancet 2013;381:774-5.

3. Wong HR, Cvijanovich N, Allen GL, Lin R, Anas N, Meyer K, et al. Genomic expression profiling across the pediatric systemic inflammatory response syn-drome, sepsis, and septic shock spectrum. Crit Care Med 2009;37:1558-66.

4. Douglas JJ, Russell JA. The role of genomics to identify biomarkers and signaling molecules during severe sepsis. Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:346-61.

5. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: interna-tional guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:165-228.

6. Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Balamuth F, Alpern ER, Lavelle J, Chilutti M et al. Delayed antimicrobial therapy increas-es mortality and organ dysfunction duration in pediatric sepsis. Crit Care Med 2014;42:2409-17.

7. Vincent JL, Brealey D, Libert N, Abidi NE, O’Dwyer M, Zacharowski K, et al. Rapid Diagnosis of Infection in the Critically Ill (RADICAL), a multicenter study of molecu-lar detection in bloodstream infections, pneumonia and sterile site infections. Crit Care Med 2015;43:2283-91.

8. Bouadma L, Luyt CE, Tubach F, Cracco C, Alvarez A, Schwebel, C et al. Use of procalcitonin to reduce patients’ exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units (PRORATA trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:463-74.

9. Man M, Close SL, Shaw AD, Bernard GR, Douglas IS,

ing, it may help orient early antibiotic choices towards the most likely causative organisms.

Many biomarker studies have demonstrat-ed that the concentration of the biomarker in question is higher in non-survivors than in sur-vivors of sepsis. But the use of sepsis mark-ers for prognosis is probably less relevant to the clinician. Prognostic biomarkers can help in triage decisions, because a patient with biomarker values suggestive of severe infec-tion should probably be admitted to the ICU rather than to the regular floor. However, it is extremely unlikely that decisions to discon-tinue therapeutic efforts would (or should) be based on the level of a biomarker. In fact, the opposite may be true; for example, one would not withdraw life support if a raised biomarker level indicated that there was a chance of per-sisting sepsis with, therefore, some remaining hope of treatment and cure.

Perhaps the most appealing use of biomark-ers is their potential therapeutic application. In this context, they have several potential functions. First, repeated measurements can help follow the response to therapy. A change in biomarker level, indicating reduced sever-ity of infection, could be used as a surrogate for an appropriate response to therapy. If there is a marked and consistent change, this could be seen as an indication to shorten the dura-tion of the antibiotic therapy.8 If, on the other hand, biomarker values do not change in the right direction, this may indicate that the anti-biotic regimen is not appropriate and should be altered, a reassessment of the need to drain a septic source should be made, and/or a further search for an infected focus should be institut-ed. A second possible therapeutic application is in the correct orientation of therapy. Genom-ics, proteomics, metabolomics can identify the predominant processes in individual patients enabling therapies to be targeted more appro-priately than is currently the case. As a simple example, a patient who expresses a lot of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) will be more likely to benefit from anti-TNF strategies than a patient with less-marked TNF expression. Likewise, genetic markers could potentially have helped to identify patients who would have benefited

vincent GENOMICS IN SEPSIS MANAGEMENT

270 Minerva anestesiologica March 2016

with repression of adaptive immunity gene programs in pediatric septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:940-6.

12. Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Anas N, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Bigham MT, et al. Developing a clinically feasible personalized medicine approach to pediatric septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:309-15.

Kaner RJ, et al. Beyond single-marker analyses: mining whole genome scans for insights into treatment responses in severe sepsis. Pharmacogenomics J 2013;13:218-26.

10. Vincent JL. The rise and fall of drotrecogin alfa (activat-ed). Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:649-51.

11. Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Fre-ishtat RJ, Anas N, et al. corticosteroids are associated

Conflicts of interest.—The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.Article first published online: September 3, 2015. - Manuscript accepted: September 3, 2015. - Manuscript received: July 31, 2015.(Cite this article as: Vincent JL. How genomics can improve the management of septic patients. Minerva Anestesiol 2016;82:268-70)

Vol. 82 - No. 3 MiNerVa aNestesiologica 271

From an ethical point of view, DcD pro-grams should be supported by a large scale awareness of the fact that DcD donation never affects patient treatment in terms of appro-priateness criteria. Most potential DcD do-nors die in icU after limitation of futile treat-ment including life support (controlled DcD, cDcD);6 in this case, organ donation repre-sents an acceptable end-of-life outcome.4, 5, 7

in italy, cDcD has been previously con-sidered unadvisable 8 in view of a probable conflict of interest in end-of-life procedures, which still pose problems in spite of the ex-cellent guidelines provided by the italian so-ciety of anesthesiology and intensive care (siaarti).9

italian law demands an excessive certainty of death, requesting an absence of ecg activity for 20 minutes, against the 5 minutes required in most countries; thus DcD has been consid-ered unsuitable in italy in spite of successful DcD programs run in several countries.10

Nevertheless, since 2007 the pilot project alba 11 has proved that DcD is possible in ita-ly for kidney transplantation after unexpected cardiac arrest occurring outside or inside the hospital (uncontrolled DcD, uDcD),6 using post mortem abdominal organ perfusion by ECMO before retrieval. Unfortunately, diffi-culties in organization and shortage in resourc-es have limited this procedure and the number of utilized organs.

Deceased organ donation (oD) should be strongly pursued as an essential target

of the Health system, basically in intensive care units (icU) and emergency Departments (eD), since a great number of patients await-ing a transplant cannot benefit from this life saving treatment due to the persisting organ shortage.1 Deceased oD may occur after death declaration based on neurological criteria (do-nation after brain death, DBD) or cardiac cri-teria (donation after circulatory death, DcD).2

in 2014, italy achieved 1383 donors and only one after cardiac death, leading to 2981 transplants against more than 8800 awaiting patients.3

ethical and clinical cornerstones related to donation procedures are high quality patient treatment and full respect of the dead-donor rule.

Unfortunately oD is an uncommon activity for most icU professionals and not system-atically included into end-of-life patients. Pro-gressive changes in etiology and the increased age of patients dying in icU with acute cere-bral lesions might greatly decrease the number of brain deaths and DBD transplantable organs. consequently DcD becomes a strategic target for the future; yet, DcD should never replace donation after brain death, which represents the essential context for multiorgan recovery.4, 5

E D I T O R I A L

organ donation after circulatory death in italy? Yes we can!

alessandro NaNNi costa, Francesco Procaccio *

centro Nazionale trapianti (cNt), istituto superiore di sanità, rome, italy*corresponding author: Francesco Procaccio, via giano Della Bella, 34, rome, italy. e-mail: [email protected]

anno: 2016Mese: MarchVolume: 82No: 3rivista: Minerva anestesiologicacod rivista: Minerva anestesiol

lavoro: 11021-Mastitolo breve: orgaN DoNatioN aFter circUlatorY DeatH iN italYprimo autore: NaNNi costapagine: 271-3citazione: Minerva anestesiol 2016;82:000-000

comment on p. 359.