michie government and the city.pdf

Transcript of michie government and the city.pdf

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

1/394

http://www.cambridge.org/9780521827690 -

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

2/394

This page intentionally left blank

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

3/394

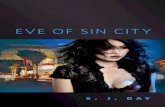

The British Government and the City of Londonin the Twentieth Century

The relationship between the British government and the City of London has become central to debates on modern British economic,political and social life. For some the Citys nancial and commer-cial interests have exercised a dominant inuence over governmenteconomic policy, creating a preoccupation with international mar-kets and the strength of sterling which impaired domestic industrialand social well-being. Others have argued that government seriouslyconstricted nancial markets, jeopardising Britains most successfuleconomic sector. This collection of essays is the rst book to addressthese issues over the entire twentieth century. It brings together leadingnancial and political historians to assess the governmentCity rela-tionship from several directions and by examination of key episodes. Assuch, it will be indispensable not just for the study of modern Britishpolitics and nance, but also for assessment of the worldwide problemof tensions between national governments and international nancialcentres.

The editors are professors of history at the University of Durham.Ranald Michies many publications in international nancial history

include The London and New York Stock Exchanges 18501914 (1987),The City of London. Continuity and Change Since 1850 (1992) and TheLondon Stock Exchange: A History (1999). Philip Williamson is authorof National Crisis and National Government. British Politics, the Economyand Empire 19261932 (1992), Stanley Baldwin. Conservative Leadershipand National Values (1999) and articles on interwar politics and nance.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

4/394

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

5/394

The British Government andthe City of London in the

Twentieth Century

edited by

Ranald Michie and Philip Williamson

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

6/394

Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, So Paulo

Cambridge University PressThe Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , UK

First published in print format

- - - - -

- - - - -

Cambridge University Press 2004

2004

Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521827690

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place

without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

- - - -

- - - -

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of sfor external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does notguarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org

hardback

eBook (EBL)eBook (EBL)

hardback

http://www.cambridge.org/9780521827690http://www.cambridge.org/http://www.cambridge.org/http://www.cambridge.org/9780521827690 -

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

7/394

Contents

Notes on contributors page vii Acknowledgements xConventions and abbreviations xi

Introduction 1

Par t I The long perspective

1 The City of London and government in modern

Britain: debates and politics 5

2 The City of London and the British government: thechanging relationship 31

Par t II Markets and society

3 Markets and governments 59

4 Financial elites revisited 76

5 The City and democratic capitalism 19501970 96

Par t III Government and political parties

6 The Treasury and the City 117. .

7 The Liberals and the City 19001931 135

v

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

8/394

vi List of contents

8 The Conservatives and the City 153. . .

9 Labour party and the City 19451970 174

Part IV The interwar period

10 Moral suasion, empire borrowers and the new issuemarket during the 1920s 195

11 GovernmentCity of London relations under the goldstandard 19251931 215

12 The City, British policy and the rise of the ThirdReich 19311937 236

Part V 19452000

13 Keynesianism, sterling convertibility, and Britishreconstruction 19401952 257

14 Mind the gap: politics and nance since 1950 276

15 Domestic monetary policy and the banking system inBritain 19451971 298

.

16 The new City and the state in the 1960s 322 .

17 The Bank of England 19702000 340. . .

Select bibliography 372Index 377

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

9/394

Notes on contributors

is a Lecturer in Economic History at the Universityof Leicester. He has published several articles on Australian overseasborrowing and the London Stock Exchange.

is Senior Lecturer in International History at theLondon School of Economics. He is author of British Capitalism at the Crossroads, 19191932: A Study in Politics, Economics, and Interna-tional Relations (1987 ) and articles on aspects of contemporary history.He is currently writing a history of the world political-economic crisisof 192733.

is Professor of Economic History at Cass BusinessSchool, London. He has published widely on monetary and nancialhistory and on commercial policy. Recent publications include Capi-tal Controls (2002) and, co-edited with G. E. Wood, Monetary Unions(2003). He is now working on the political economy of nancial regu-lation.

is Professor of Economic History at the UniversityPierre Mend` es France, Grenoble, and a visiting research fellow in theBusiness History Unit at the London School of Economics. His manypublications include City Bankers 18901914 (1994) and Big Business:the European Experience in the Twentieth Century (1997). He is currentlyworking on the performance of European business and on the historyof international nancial centres during the last two centuries.

is Head of the Department of History, InternationalRelations and Politics at Coventry University. His publications includeDoing Business with the Nazis: Britains Economic and Financial Rela-tions with Germany, 193139 (2000) and he is currently writing a studyof how multinational enterprises managed political risk in interwarEurope.

vii

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

10/394

viii Notes on contributors

. . worked in the Bank of England from 1968 to 1985,becoming Chief Adviser, and returned as an external member of theMonetary Policy Committee from 1997 to 2000. He was NormanSosnow Professor of Banking and Finance at the London School of

Economics until 2002, and is now deputy director of the SchoolsFinancial Markets Group. He has written extensively on economic andmonetary history, central banking, and nancial regulation.

. . . is Reader in Modern British History at the Universityof Oxford, and a Fellow and Tutor at Magdalen College. He is theauthor of The Crisis of Conservatism 18801914 (1995) and Ideologies of Conservatism (2002). His study of Margaret Thatchers reputation will

appear in 2005. is Professor of Modern History at the University of

East Anglia. He is the author of Free Trade and Liberal England, 1846 1946 (1997 ) and several articles on the City of London and economicpolicy. He is currently working on the international history of free tradeand globalisation since 1776.

is Professor of History at the University of Durham.His many publications in nancial history include The City of London.Continuity and Change Since 1850 (1992 ), and The London StockExchange. A History (1999 ). He is now working on the London for-eign exchange market.

is Senior Lecturer in History at Cardiff University. Hehas written extensively on twentieth-century British economic historyand policy and is currently writing a history of the global economy

from 1944 to 2000. His most recent book is Prots of Peace: the Political Economy of Appeasement (1996).

. . is Professor of History at the University of Stirling. Hispublications include British Rearmament and the Treasury, 19321939 (1979) and The Treasury and British Public Policy, 19061959 (2000 ).He is currently working on Treasury responses to Keynes in the period192546.

. is Senior Lecturer in Economic History at theUniversity of Glasgow, and co-editor of Financial History Review .Among his recent publications are essays in Mission Historique dela Banque de France, Politiques et Pratiques des Banques dEmission enEurope, XVIIeXXe si` ecle (2003), and S. Battilossi and Y. Cassis (eds.),European Banks and the American Challenge (2002).

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

11/394

Notes on contributors ix

. is Professor of International Economic His-tory at the University of Glasgow. She has published widely on inter-national monetary and nancial relations since 1945 including Britainand the Sterling Area: from Devaluation to Convertibility in the 1950s

(1994 ) and Hong Kong as an International Financial Centre (2001). Sheis currently engaged on a project reassessing Britains sterling policy195873.

is Senior Lecturer in the School of Management,University of Liverpool. Among his publications are The Finance of British Industry 19181976 (1978), The Big Bang (1986) and The Secu-rities Markets (1989). He is currently working on the gilt-edged market

in the latter half of the nineteenth century. is Professor of Economic History at Brunel Univer-

sity, London. He has written widely on twentieth-century Britisheconomic history and policy. His work relating to the Labour partyincludes Democratic Socialism and Economic Policy. The Attlee Years,19451951 (1997 ), and The Labour Governments 19641970, III:Economic Policy (2004).

is Reader in Modern History at the University of Leeds. His recent publications include The Labour Party and Taxation:Party Identity and Political Purpose in Twentieth-Century Britain (2001),and he is now interested in labour law and the nature of work.

is Professor of History at the University of Durham, and author of National Crisis and National Government. BritishPolitics, the Economy and Empire 19261932 (1992 ), Stanley Baldwin.

Conservative Leadership and National Values (1999), and articles oninterwar politics and nance.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

12/394

Acknowledgements

This book draws on papers submitted to a conference held in the Univer-sity of Durham in 2001. The purpose of that conference was to explorethe issues and allow all participants to develop their arguments. Unfor-tunately it was not possible to publish all the conference papers, but theeditors are grateful to all the speakers and contributors to the debate.They are grateful also to the London Stock Exchange for funds whichsupported both the organisation of the conference and the preparation of the book, and to Christine Woodhead for her editorial assistance.

x

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

13/394

Conventions and abbreviations

Full names of historical individuals are given in the index. This also givesthe terms of ofce of the Bank of England Governors, Chancellors of theExchequer and the Prime Ministers mentioned in the text.

Unless otherwise stated, the place of publication is London.

BEQB Bank of England Quarterly BulletinBoE Bank of England ArchivesBT Board of Trade papers, in the National

Archives/Public Record Ofce

CAB Cabinet Ofce papers, in the NationalArchives/Public Record OfceCO Colonial Ofce papers, in the National

Archives/Public Record OfceCPA Conservative Party Archives, Bodleian

Library, OxfordEcHR Economic History ReviewFO Foreign Ofce papers, in the National

Archives/Public Record OfceGATT General Agreement on Tariffs and TradeHC Deb House of Commons Debates , 5th series, with

volume and column (c., cc.) numbersKynaston, City of London David Kynaston, The City of London , in

4 volumes:I A World of its Own 18151890 (1994)II Golden Years 18901914 (1995)III Illusions of Gold 19141945 (1999)IV A Club No More 19452000 (2001)

LPA Labour Party Archives, National Museumof Labour History, Manchester

PP Parliamentary Papers

xi

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

14/394

xii Conventions and abbreviations

PREM Prime Ministers private ofce papers, inthe National Archives/Public RecordOfce

Radcliffe Committee Committee on the Working of the

Monetary System, 19579T Treasury papers, in the National

Archives/Public Record OfceWilson Committee Committee to Review the Functioning of

Financial Institutions, 19779

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

15/394

Introduction

The nature of the relationship between the government and the City of London, or more abstractly between politics and nance, is a centralissue in studies of modern Britain. The relationship is assumed to havebeen close and to have had wide repercussions, but thereafter disagree-ments have emerged. It is a problem in economic and nancial history:to what extent has the relationship affected the performance and struc-ture of the economy in general, and the development of its nancial andindustrial sectors in particular? It is a problem in political history andpolitical science: have government and the City had shared or divergent

interests? Which has been more powerful? Has government unduly con-stricted the Citys nancial markets, or has the City exerted excessiveinuence over the policy agenda and particular decisions? For imperialhistorians the question has been how far did City interests shape Britishoverseas expansion and, later, the character of decolonisation? Historiansof international relations have asked how far City interests have supportedor conicted with particular government foreign policies. The relation-ship is also an issue in social history and sociology: was there a signicant

merger of personnel and interest between the Citys nancial elite andthe governing elites, at the expense of other socio-economic groups?

This book brings together political and nancial historians to investi-gate the governmentCity relationship during the twentieth century, con-sidered from various directions and by attention to revealing episodes. Inthe rst section, the opening chapter describes the issues as these haveemerged in recent historical studies and assesses them from a politicalperspective, while the second chapter traces the relationship over thelong-term from a nancial and economic perspective. The next sectionof three essays then considers issues relating to the broad economic andsocial environments: the boundaries between markets and government,the debate over the extent to which the City generated a distinctive socio-political elite and, in contrast, postwar efforts to democratise ownershipof nancial assets. The essays in the third section examine the perspectiveof the Treasury, as the department of government most in contact with

1

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

16/394

2 Introduction

City institutions, and then those of each of the main political parties:the Conservative party throughout, and the Liberal and Labour partiesduring their periods of greatest potential impact on City activities.

Before 1914 governmentCity interactions were limited, while both

world wars produced exceptional conditions, in which the state imposeddetailed control over the Citys activities, with its co-operation or acqui-escence. Examination of the particular character and changing nature of governmentCity relations is therefore best undertaken on the interwarand the post-1945 years. The section on the interwar period has chapterson the attempt to restore the pre-1914 relationship in radically changedeconomic and political conditions, and examples of how it operated inthe spheres of two other government departments, the Colonial and For-eign Ofces. The chapters in the post-1945 section examine aspects of the governmentCity relationship during the long period of a managedand increasingly beleaguered economy, followed by the impact of a newnancial internationalism. It concludes with an overview of the relation-ship over the last thirty years of the century from the perspective of theBank of England.

The aim of this book has been to advance debate on the government City relationship by adding historical depth and understanding, not toseek agreement among the contributors nor to draw general conclusions.What can be said is that the relationship is in the process of fundamentalchange because of the growing involvement of more players on each side.It is no longer sufcient to consider only the role of the British govern-ment, because the European Union is becoming increasingly important indetermining the laws, rules and methods of all in the City of London. Nor

can the City any longer be identied just with British banks and Britishnancial institutions serving British clients, not only because it is a majorparticipant in global nancial markets but also because, with many of its major businesses now foreign-owned, it is answerable to head ofceslocated all around the world. The debate on the relationship between theBritish government and the City of London is increasingly just one partof the debate on the relationship between any nancial centre and its hostgovernment, between those who regulate and those who are regulated,and between national sovereignty and trans-national power at a time of nancial globalisation. These are not new issues, but they have entered anew phase over the last twenty-ve years.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

17/394

Part I

The long perspective

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

18/394

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

19/394

1 The City of London and governmentin modern Britain: debates and politics

Philip Williamson

Substantial historical interest in the City of London is a recentdevelopment. Financial historians studied its main institutions, some of its leading banks and aspects of monetary policy, but it received littlecomment even from other economic historians and was usually ignoredin more general histories. Only in the 1980s did the City, consideredas a whole, become a unit of study and enter the mainstream of histori-cal attention, and only then did it attract interest from political scientistsand sociologists. Partly this reected the contemporary prominence of the City, due to the transformations which were then taking place in the

nancial system and the publicity given to the fabulous incomes and con-spicuous consumption of nancial dealers. A larger reason was a shift inthe long-running debate about the relative decline of the British econ-omy, meaning primarily manufacturing industry. After numerous otherpossible causes had been investigated, the nancial sector now seemedto be the chief culprit. At rst attention focused on the supposed failureof the banks and the Stock Exchange to supply industry with adequateamounts or appropriate forms of capital. 1 Increasingly, however, the dam-

age inicted by the City seemed more wide-ranging: except during thetwo world wars, it had exercised the dominant inuence over governmenteconomic policy. Such claims connected with work by historians in otherelds, and gave the City, and indeed nancial history, an entirely newsalience. Soon the issue of the relationship between the British govern-ment and the City of London acquired its own momentum, as it appearedto offer cogent explanations for many features of Britains domestic andinternational experience since 1850.

The author is indebted to the British Academy for the award of a research readership,during which this chapter was completed.

1 Helpful reviews of this debate are Y. Cassis, British nance: success and controversy, in J. van Helten and Y. Cassis (eds.), Capitalism in a Mature Economy (Cheltenham, 1990),pp. 122, and F. Capie and M. Collins, Have th e Banks Failed British Industry? (Instituteof Economic Affairs, Hobart Paper 119, 1992 ).

5

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

20/394

6 Philip Williamson

The cases made for the Citys inuence over government have beenchallenged, and some specic claims have provoked debates. This chapterreviews the various arguments, and from a political perspective suggestsways in which the discussion might be advanced. It urges more careful

specication of its leading terms, fuller consideration of the character of its main participants, particularly what is understood by government,and a wider investigation of inuences on the policy process. Both theCity and the government have been more complex and more uid enti-ties, and been subjected to a broader range of pressures, than is some-times allowed. The discussion of governmentCity relations has had thestrength of drawing together historians and social scientists from the var-ious elds of economics, nance, sociology, government, politics andimperial relations; even so, some disciplinary barriers remain, inhibitinga more precise understanding of the extent and nature of the interactions.

Debates

One of the earliest historical discussions of governmentCity relationsemerged from the debate on the causes of interwar unemployment. For

Sidney Pollard, the governments determination in the early 1920s tore-establish the gold standard was a bankers policy: it expressed thespecic self-interest of a narrow section of the City and its spokesman,the Bank of England, while the Treasury as ever reected the needsof the City rather than the country, with terrible costs for industry andemployment. 2 Later, this type of argument was broadened as the mainissue became Britains relative industrial decline, regarded as a persis-tent problem dating from the late nineteenth century. For Pollard again,

industry has every time to be sacriced on the altar of the Citys andthe nancial systems primacy, because the Bank of England an d thebanking community largely determined the Treasurys priorities. 3

Such conceptions also became integral to general interpretations of Britains long-term socio-economic and political development. At theirheart was a growing realisation that notwithstanding the industrial revo-lution the nancial and commercial sector had always been a strong anddynamic element in the British economy, indeed arguably more impor-tant for its performance than the manufacturing sector. The general inter-pretations drew support from socio-economic and cultural studies which

2 S. Pollard, Introduction to S. Pollard (ed.), The Gold Standard and Employment Policiesbetween the Wars (1970 ), pp. 126.

3 S. Pollard, The Wasting of the British Economy. British Economic Policy 1945 to the Present (1982), pp. 345, 73, 858, 1501; also S. Pollard, Britains Prime and Britains Decline.The British Economy 18701914 (1989), pp. 23556.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

21/394

City and government: debates and politics 7

independently concluded that the leaders of nance capital were morepowerful than those of industrial capital, and after 1850 acquired a spe-cial relationship with the governing landed classes. William Rubinsteinestablished that the wealth of the nancial and commercial middle class

of metropolitan southern England excee d ed that of the industrial mid-dle class of provincial northern Britain. 4 Youssef Cassis argued that amerger of the Citys nancial elite with the landed elite had produced anacceptance of City views on economic policy. 5 For Martin Wiener thesocial and cultural absorption of new middle-class wealth by old landedwealth had produced a gentrication of dominant values, smotheringthe industrial spirit. 6

The earliest of the general interpretations came from the new left.Perry Anderson argued that the survival of a pre-modern ruling classand its penetration by monied interests explained both the conservatismof the British state and the hegemonic position of the City. 7 For FrankLongstreth the banking fraction of capital had achieved primacy in thestate system, which enabled the City to dominate economic policy andthe political realm. 8 Geoffrey Ingham, in a sociological challenge tothese neo-Marxist interpretations, gave a different explanation. The Bank

of England and the Treasury were not mere instruments of the City, buthad independent sources of power and independent interests. Rather, theCitys hegemony was the product of a core institutional nexus of theCity, the Bank and the Treasury, bound together by their one mutualinterest preserving stable money forms. 9 From a different perspec-tive, Peter Cain and Anthony Hopkins argued that prolonged alliancebetween the landed and nancial interests had generated a gentlemanlycapitalism, whose character explained the form not just of the British

4 W. D. Rubinstein, Wealth, elites and the class structure of modern Britain, Past and Present 76 (1977), 99126, and W. D. Rubinstein, Men of Property (1981).

5 Y. Cassis, City Bankers 18901914 (Cambridge, 1995 ; rst edn in French, 1984 ), esp.ch. 8; and see similarly, reaching further into the twentieth century, M. Lisle-Williams,Beyond the market: the survival of family capitalism in the English merchant banks, andM. Lisle-Williams, Merchant banking dynasties in the English class structure: ownership,solidarity and kinship in the City of London, British Journal of Sociology 35 (1984), 241 71, 33362.

6 M. Wiener, English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit 18501980 (Cambridge,1981), with specic references to the City on pp. 1289, 145.

7 P. Anderson, Origins of the present crisis, New Left Review 23 (1964), 2653, andP. Anderson, The gures of descent, New Left Review 161 (1987), 2077; and seeA. Gamble, Britain in Decline. Economic Policy, Political Strategy and the British State (1981),pp. 13443.

8 F. Longstreth, The City, industry and the state, in C. Crouch (ed.), State and Economyin Contemporary Capitalism (1979 ), pp. 15790.

9 G. Ingham, Capitalism Divided. The City and Industry in British Development (1984 ), esp.pp. 911, 37, 12739, 1789, 21516, 219, 22932.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

22/394

8 Philip Williamson

state but also of the British empire. As a branch of gentlemanly capital-ism the City had a disproportionate inuence in British economic lifeand economic policy making. 10

These converging characterisations of the Citys inuence over the gov-

ernment, especially Inghams concept of a CityBankTreasury nexus,have had considerable inuence. This is evident in studies of the bi-metallism controversy in the late nineteenth century and the nancialcrisis at the outbreak of the First World War; in Robert Boyces discus-sion of the politics of economic internationalism under the gold standardregime of 192531; in an investigation of the emergence of Euromarketsin the 1950s, and in a much-noticed 1990s critique of the contemporarystate. 11 In Ewen Greens review of the issues from the 1880s to 1960, theCitys lobbying power, structural links with the state and overlapping eco-nomic ideology with the Treasury ensured that, in the long run, bankingsector priorities were translated into government priorities. 12 For ScottNewton and Dilwyn Porter the power of the core nexus was a lead-ing explanation for the failure of industrial modernisation since 1900. 13

In such accounts government economic policy turned upon a contestbetween the international interests of the City or nance and the more

national concerns of industry or production, with the Citys interestsnormally prevailing. This was not simply because of its economic impor-tance and its provision of funds to the government. It also resulted fromfurther forms of power: an early integration of the nancial and rulinglanded elites; the Citys economic cohesion, geographical concentrationand physical proximity to, and institutional connections with, the gov-ernment. The effect was that government always tended to identify theCitys interests with the national interest.

In their coherence, explanatory economy and treatment of a long time-scale, these conceptualisations of governmentCity relations have seemed

10 P. J. Cain and A. G. Hopkins, Gentlemanly capitalism and British expansion overseas.I. The old colonial system 16881850 and II. New imperialism 18501945, EconomicHistory Review 39 (1986), 50125, and 40 (1987), 126; and P. J. Cain and A. G.Hopkins, British Imperialism , 2 vols. (1993 ; revised one-volume edn, 2001 ).

11 E. H. H. Green, Rentiers versus producers? The political economy of the bimetalliccontroversy c. 18801898, English Historical Review 103 (1988), 588612; J. Peters, TheBritish government and the Cityindustry divide: the case of the 1914 nancial crisis,Twentieth Century British History 4 (1993 ), 12648; R. W. D. Boyce, British Capitalismat the Crossroads 19191932 (Cambridge, 1987 ), esp. ch. 1; G. Burn, The state, theCity and the Euromarkets, Review of International Political Economy 6 (1999 ), 22561;W. Hutton, The State Were In (1995), pp. 223, 7981, 11236.

12 E. H. H. Green, The inuence of the City over British economic policy c. 18801960,in Y. Cassis (ed.), Finance and Financiers in European History 18801960 (Cambridge,1992 ), pp. 193218.

13 S. Newton and D. Porte r, Modernization Frustrated. The Politics of Industrial Decline inBritain since 1900 (1988 ): see the themes stated on pp. xixv.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

23/394

City and government: debates and politics 9

powerful and persuasive. Yet like other general interpretations they riskbecoming schematic and reductionist, establishing assumptions whichforeclose further investigation and exclude alternative explanations. Suchterms as the City and government might be given excessive force, and

be presented as unitary agents capable of uniform intentions. Coinci-dences of outlook between the two might be mistaken for causation;opinions of particular bankers might be elevated into proof of City dom-ination, when quite different and more adequate explanations of govern-ment decisions could be found. There certainly seem to be difcultieswith these approaches. Doubts have been expressed about the extentof the Citys cohesion, its distance from industry and its political inu-ence. 14 Episodes which appeared to be prime cases of division betweennance and industry, notably the debates on bimetallism and tariffsbefore 1914, have on further scrutiny been found to be less clear cut. 15

The notion of an Edwardian identity of views between political circlesand banking circles 16 sits uneasily with the Unionist partys adoptionof tariff reform, which challenged the Citys long-standing attachmentto free trade, and the Liberal governments 1909 budget, which arousedconsiderable City protest for threatening capital accumulation. Against

the government decision in 1925 to restore the gold standard might beset its original 1919 decision to abandon it, despite the recommendationof its own banker-dominated ofcial committee, largely because of con-cerns about unemployment and the attitudes of industrial labour. 17 Theoutcomes of the sterling and budget crises of 1931, for all the allegationsof a bankers ramp, were more the product of party-political manoeu-vres than City or Bank of England pressure. 18 Nor is it difcult to ndfriction between the Bank of England and Treasury ofcials or govern-

ment ministers, whether over use of the gold reserves in 1917, bank rate

14 See the important sceptical commentaries by M. Daunton: Gentlemanly capitalismand British industry 18201914, Past and Present 122 ( 1989 ), 11958; Financial elitesand British society 18801950, and Finance and politics: comments, in Y. Cassis (ed.), Finance and Financiers , pp. 12346, 28390; and Home and colonial, Twentieth CenturyBritish History 6 (1995), 34458.

15 See the A. C. Howe and E. H. H. Green debate in English Historical Review 105 (1990),37791, 67383; Daunton, Gentlemanly capitalism, pp. 14951; A. C. Howe, FreeTrade and Liberal England, 18461946 (Oxford, 1997 ), pp. 199204, 2336; E. H. H.Greens modied analysis, Gentlemanly capitalism and British economic policy 1880 1914: the debate over bimetallism and protectionism, in R. E. Dumett (ed.), Gentle-manly Capitalism and British Imperialism (1999), pp. 4467, and the Howe and Greenchapters 7 and 8 below.

16 Cassis, City Bankers , p. 308.17 P. Cline, Reopening the case of the Lloyd George Coalition and the postwar economic

transition 191819, Journal of British Studies 10 ( 1970 ), 16275.18 P. Williamson, National Crisis an d Nati onal Government. British Politics, the Economy and

Empire 19261932 (Cambridge, 1992 ), chs. 811.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

24/394

10 Philip Williamson

in the 1920s, credit control in the 1950s and 1960s, or public sectorexpenditure in the 1960s and 1970s. Even combined Bank and Treasuryadvice did not necessarily prevail: in 1952 a joint plan for an immediatereturn to sterling convertibility (Robot) was defeated by Conservative

ministers. Three major governm ent enquiries on the nancial system in 192931, 19579 and 19779 19 attest to recurrent political doubtsabout City activities.

More considerable still is the perspective in studies of the City of London itself. For the period after 1914 these reveal much governmentor Bank of England control, regulation and intervention, not only dur-ing the emergencies of the two world wars and their immediate after-math when it is accepted that the government overrode most Cityactivities but even during normal periods of peacetime. The gov-ernments borrowing and funding requirements, measures to supportthe balance of payments, taxation policies, nationalisation of utilities,credit restrictions and even labour legislation all affected, and frequentlyinhibited, the business and international competitiveness of City rmsand markets. 20 In the 1970s a common City view was that the nancialcommunity was the victim of government action and was incapable of

putting its case effectively in Whitehall or Westminster.21

When after1971, culminating in Big Bang in 1986, the government and the Banktook measures to overcome restrictive practices within the City prac-tices created or encouraged by their own earlier interventions its struc-tures and activities were again decisively shaped by government action,even though the outcomes were often different from what had beenintended.

Neither particular cases of Citygovernment tensions nor a persistent

government imprint on the City are necessarily incompatible with theargument that the City had a strong inuence over economic policy. Theweight of particular episodes might still seem to favour the prevailinginterpretations, while the effects of government within the City could havebeen of a different order to the Citys effects on government. Neverthe-less, such counter-cases and contrary perspectives emphasise the need forcaution. It may be that, as Martin Daunton has written, the notion thateconomic policy was dominated by an alliance of the City and Treasury

19 Respectively the (Macmillan) Committee on Finance and Industry, the (Radcliffe) Com-mittee on the Working of the Monetary System, and the (Wilson) Committee to Reviewthe Functioning of Financial Institutions.

20 These are leading themes in R. C. Michie, City of London. Continuity and Change Since1850 (1992 ), and R. C. Michie, The London Stock Exchange. A History (Oxford, 1999 ).

21 M. Moran, Finan ce capi tal and pressure-group politics in Britain, British Journal of Political Science 11 ( 1981 ), 382, 399.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

25/394

City and government: debates and politics 11

is a regrettable commonplace of modern British history which obscuresother, and more interesting, features of policy formation. 22

The City

The contrasting histories of the City of London by Ranald Michie andDavid Kynaston have both shown that as an economic entity the Citydees easy generalisation. It might be dened as a national and inter-national clearing house, a collection of markets used by intermediariesin trade, money, securities and nancial services. As such its essenceand its strength consisted in the remarkable diversity and exibility of itsactivities. 23 Its markets and rms were highly specialised in their func-tions, types of client and geographical areas of expertise, and even withinthe City itself they operated in a highly competitive environment. Pre-cisely because it was an international clearing house the City was vul-nerable to sharp structural changes in the world economy especiallythe two world wars and the 192932 depression as was its nancialsector to sudden international capital ows. Some instances of supposedCity pressure on government, notably during successive sterling crises,

are more fully understood as emanating from foreign markets and insti-tutions. Another of the Citys core businesses, providing funds for theBritish state, meant that from the First World War onwards many of its activities were subordinated to the demands of a massively enlargednational debt. The effect was that the Citys activities and its structure of rms changed considerably over the century from 1914 to the 1950s los-ing much of its long-established commercial and international nancialbusiness and becoming increasingly concerned with domestic nance,

before new forms of trans-national nance emerged during the 1960sand re-established its international pre-eminence. 24

Assessments of the City of Londons long-term inuence over govern-ment policy need to give careful attention to these changes in composi-tion. Yet so diverse, uid, competitive and prone to external pressureswere its activities, and so tied to the immediate conditions and uctua-tions of their specialist markets were its brokers, bankers and merchants,that the ability of the City as a whole to form a coherent policy interestrequires demonstration, rather than being taken for granted. 25 It can be

22 M. Daunton, How to pay for the war: state, society and taxation in Britain 191724,English Historical Review 111 (1996), 916.

23 Michie, City of London , pp. x, 213, and see the evocation of complexity and uidity inD. Kynaston, The City of London , 4 vols. (19942001 ).

24 See Michie, City of London , and his chapter 2 below.25 For further comment from various directions, see Daunton, Gentlemanly capitalism,

14651, and Daunton, Financial elites, pp. 13942; R. C. Michie, Insiders, outsiders

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

26/394

12 Philip Williamson

argued that the demands of its various businesses for easy access to andready international exchange of money did create common interests inopen markets, free international trade, a stable and convertible currency,government credit-worthiness and low taxes. These were, however, very

general concerns which left room for differences over extent and means;and once each was expressed as a specic policy preference, they couldconict. For example, during the Edwardian period City men were facedwith a choice between free trade and low direct taxation. Most opposed Joseph Chamberlains tariff reform campaign when it started in 1903, butafter 1906 an increasing number accepted it as preferable to the Liberalgovernments tax increases. 26

In practice, when historians use the term the City they rarely mean thewhole accumulation of economic activities located in the City of London.Most often it is treated as a synonym for the City-based banks, leavingaside the commodity markets, trading companies, shipping interests, andeven the insurance markets and the Stock Exchange. Yet even here thereare complications. This City is usually identied with only some of the banks, and at different times with different types of bank. Beforethe 1930s these are the leading merchant banks, with their international

businesses, but from the 1940s they become the clearing banks, whoseprincipal concerns were domestic.Such semantic shifts in the historical literature indicate an important

point about contemporary meanings. From the perspective of the govern-ment and the Bank of England, what principally constituted the Cityvaried, not just over time but according to what seemed most relevantfor their purposes. There was the City which rarely impinged on theirconcerns, and which when it did tended to be regarded as a problem

or irritant. This was true of the Stock Exchange, whose interests a ndopinions usually carried little weight in government or with the Bank. 27

There was the City which handled the technical and normally routinebusiness of government borrowing. Its leading bankers were importantand needed to be consulted, but this business rarely gave rise to issueswhich can properly be termed economic policy. The City whose viewswere considered signicant for policy reasons might consist of a different

and the dynamics of change in the City of London since 1900, Journal of ContemporaryHistory 33 (1998), 54771; M. Moran, Power, policy and the City of London, inR. King (ed.), Capital and Politics (1983 ), pp. 4951; S. Checkland, The mind of theCity, Oxford Economic Papers , n.s. 9 (1957 ), pp. 2645, 2734, 2768; R. Roberts andD. Kynaston, City State. How the Markets Came to Rule Our World (2001 ), p. 17.

26 See Howes chapter below, pp. 141 3.27 Michie, London Stock Exchange , pp. 186, 4235, 601.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

27/394

City and government: debates and politics 13

set of bankers; and as economic policy objectives changed from maint-enance of the gold standard to management of the domestic economy sothe relevant types of bankers altered. Is the City said to be important forgovernment policy in the 1900s the same City which seems to inuence

policy in the 1950s? How far can cases made for the Citys capacity andmeans for inuencing government in the 1900s be generalised to applyto the 1950s?

The City as a whole was not organised as a pressure group or interest.In the early part of the century, occasional petitions to senior ministerswere organised by the bankers and merchants of the City, notably on theissue of the 1909 budget. 28 In 1920 there was even a joint representationfrom the heads of the Bank of England, clearing and merchant banks,Stock Exchange and London chamber of commerce, proposing a radicalsolution to the problem of the postwar oating debt. 29 But these wereexceptional actions at the height of perceived crises, not part of sustainedefforts to shape policy and they had little or no impact on govern-ment. A parliamentary committee of bankers had only an indistinct andtransitory existence before 1914. From the 1960s some attempts weremade to unite nance capital, embracing all the various nancial busi-

nesses within one organisation, but without success. Particular types of bank or market members did form representative associations, such asthe Accepting Houses Committee and London Discount Market Associ-ation, but compared to industrial and trade associations these were slowto develop and, like them, were concerned with self-regulation, imple-mentation of ofcial requirements, and technical issues of direct con-cern to their members, not matters of general economic policy. Some,including the Accepting Houses Committee, were also weak and for long

periods practically moribund. Only during the 1970s, in response toincreased government intrusion in the City, d id pressure groups emergeor older associations become lobbying bodies. 30 Until then such activityhad seemed unnecessary, because the leading banks regarded the Bank of England as its representative and channel of communication in dealingswith the government.

28 The Times , 15 May 1909, and see Kynaston, City of London , II, pp. 4946, and below,pp. 121 2, 140 .

29 M. Daunton, Just Taxes. The Politics of Taxation in Britain, 19141979 (Cambridge, 2002),p. 77. For another example, of coordinated letters from leading bankers during the 1931crisis, see Williamson, National Crisis , pp. 282, 293.

30 Cassis, City Bankers , pp. 27184; Moran, Finance capital and pressure-group politics,pp. 3856, 38993, 3979. In a similar shift, in 1979 the Stock Exchange joined theConfederation of British Industries: Michie, London Stock Exchange , pp. 4867.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

28/394

14 Philip Williamson

The Bank of England

For some historians the Bank of England is part of the City, for othersan instrument of the government. This reects both an ambiguity which

was always inherent in its various functions, and its changing relation-ship with the government during the century. In some respects the Bankobviously did act on behalf of the City, meaning those sectors of theCity which it considered especially important at particular times. As itsresponsibilities included the stability of the nancial system, it helped toreorganise markets disrupted by war or depression, and to rescue ailingbanks and nance houses; indeed until the 1980s it tacitly guaranteedthe solvency of all the Citys leading banks. Its expanding supervisionof the banking system and later other City markets and rms became ameans of protecting them from government interference. As the Cityscontact with the Treasury and the elected government, it upheld or advo-cated policies which it believed would benet the nancial system, andprotested against government measures which it considered damaging tothat system or its particular parts on occasion placing severe pressure onministers by insisting that preservation of nancial condence should take

priority over all other policies. Sometimes, as over credit restriction in the1950s, it even obstructed government policies. 31 For all these purposes,as far and as long as possible the Bank distanced, even insulated, itself from government and defended its independence as an institution andits control of monetary policy. These originally seemed to be guaranteedby its delegated powers under the gold standard, and its being in privateownership. Even after the nal departure from the gold standard in 1931transferred ultimate monetary authority to the Treasury and even after the

Bank was nationalised in 1946, it still asserted its operational autonomyand right to give independent advice, even though this could contradictthe governments electoral or other public commitments. 32 The Bank

31 J. Fforde, The Bank of England and Public Policy 19411958 (Cambridge, 1992 ), ch. 10;A. Ringe and N. Rollings, Domesticating the market animal? The Treasury and theBank of England 195560, in R. A. W. Rhodes (ed.), Transforming British Government ,I, Changing Institutions (2000 ), pp. 1237.

32 For excellent studies of these various aspects, see D. Kynaston, The Bank of Englandand the government and R. Roberts, The Bank of England and the City, in R. Robertsand D. Kynaston (eds.), The Bank of England. Money, Power and Inuence, 16941994(Oxford, 1995 ), pp. 1955, 152184; A. Cairncross, The Bank of England: relationshipswith the government, the civil service and Parliament, in G. Toniolo (ed.), Central Banks Independence in Historical Perspective (Berlin, 1988 ), pp. 3972; M. Collins andM. Baker, Bank of England autonomy: a perspective, in C.-L. Holtfrerich, J. Reis andG. To niolo (eds.), The Emergence of Central Banking from 1918 to the Present (Aldershot,1999 ), pp. 1333; M. M oran, Monetary policy and the machinery of government,Public Administration 59 ( 1981 ), 4761.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

29/394

City and government: debates and politics 15

was notably successful in ensuring that the nationalisation act preservedits position as the intermediary or barrier between government andthe banking system, denying the Treasury powers of direction over theclearing banks. 33

Nevertheless the Bank did not regard itself as merely the representa-tive or voice of the City. As its deputy Governor told the MacmillanCommittee in 1929, it considered its main duty to be to conduct itsoperations in the interests of the community as a whole . . . free fromthe control of particular groups or interests. While such statements werechiey intended to justify the Banks political independence, they alsoimplied a position of independence within the City and a readiness, wherejudged appropriate, to direct, control and discipline the activities of itsrms and markets. 34 In the 1930s and 1940s this could involve pres-sure on merchant and clearing banks to assist depressed industries orsmall industrial companies, against the banks own sense of appropriateor sound banking business. 35 On a much larger scale, under the pressuresof war, depression and government economic management the Banksresponsibilities as banker to the government and guardian of the cur-rency and the nancial system obliged it to play a large part in shaping

the Citys nancial structures and activities. By its own operations or bymoral suasion it organised or regulated the money markets and capitalissues to suit the governments borrowing requirements and the fundingof its short-term debt. Together with the Treasury it imposed exchangecontrols and embargos or restrictions on overseas investment in order tostabilise the currency and the exchange rate. 36 From the 1940s it issuedrequests always treated as instructions to clearing banks and othernancial houses for restraint in their advances: its objections were not to

the principle of credit restriction, but to Treasury views on method and

33 S. Howson, British Monetary Policy 194551 (Oxford, 1993 ), pp. 11017; Fforde, Bankof England , pp. 1013.

34 See P. Williamson, Financiers, the gold standard and British politics, 19251931, in J. Turner (ed.), Businessmen and Politics. Studies of Business Activity in British Politics 1900 1945 (1984 ), p. 109. For an account of this period with different emphases, see Boyce,chapter 11 below.

35 R. S. Sayers, The Bank of England 18911944 , 3 vols. (1976 ), I, ch. 14; W. R. Garsideand J. I. Greaves, The Bank of England and industrial intervention in interwar Britain, Financial History Review 3 (1996 ), 749; R.Coopey and D. Clarke, 3i: Fifty Years Invest-ing in Industry (Oxford, 1995 ), pp. 1623. Among the Banks reasons was a desire topre-empt government intervention in industry as well as in banking: defence of privateenterprise extended beyond the City to manufacturing companies.

36 Roberts, The Bank of England and the City, 16076, 17881; Sayers, Bank of England ,I, chs. 9, 13, and II, ch. 19; S.Howson, Domestic Monetary Management in Britain 191938 (Cambridge, 1975 ); J. Atkin, Ofcial regulation of British overseas investment 1914 1931, EcHR 23 (1970), 32435; D. Mo ggridg e, British Monetary Policy 19241931. The Norman Conquest of $4.86 (Cambridge, 1972 ), chs. 79.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

30/394

16 Philip Williamson

degree. While these interventions were presented as being in the Citysgeneral interest as well as the national interest, they nevertheless curtailed,redirected, or cushioned the business of particular markets and individ-ual rms. They were also the main reason for the growth of organisation

among City rms. These associations were encouraged or initiated by theBank in order to facilitate the implementation of controls, regulations andrequests.

In signicant respects the discount houses and leading banks becameunpaid agents of the state, indeed were incorporated into public policymaking. 37 Of course the relationship was far from operating in one direc-tion only. In order to ensure the banks co-operation, the Bank conferredprivileges on them, accepted their systems of self-regulation and restric-tive practices, and had to be solicitous about their interests. Yet even thistended to tie the banks to the Bank of England, as they became dependenton its assistance in preserving their cartels against unregulated competi-tors. As the historian of the Bank during the 1950s commented, a widereffect was that civil servants and ministers came to regard the bankingsystem as a creature to be manipulated through the Bank in the inter-ests of short-term macro-economic policies. Despite occasional public

and private protests the banking system became used to accepting suchmanipulation, with damage to their own efciency and to the servicesprovided to its customers. 38 The Stock Exchange underwent a similarprocess. From 1914 onwards its business was impaired by Treasury aswell as Bank of England restrictions, but it learned to exploit these tostrengthen itself against competitors and became so accustomed to exer-cising quasi-ofcial responsibilities that it seemed almost an arm of thestate. 39

Although the Bank had responsibilities towards the government, plainlyit was not just the instrument of government any more than it was simplythe representative of City bankers. From Montagu Normans early gov-ernorship during the 1920s it had its own opinions not just on bankingmatters but also on wider domestic and international economic issues.Moreover, as the leading nancial institutions and associations communi-cated with the government through the Bank, their concerns were liableto be ltered through its own perceptions and objectives. In practice,within government City inuence chiey amounted to the views andinterpretations of the Bank of England. These were expressed forcefully

37 Moran, Finance capital and pressure-group politics, 383, 3878, 3939; B. Grifths,The development of restrictive practices in the U.K. monetary system, Manchester School 41 (1973), 318.

38 Fforde, Bank of England , p. 782.39 Michie, London Stock Exchange , esp. pp. 18296, 2914, 3245, 330, 3657, 4257,

545, 594, 637.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

31/394

City and government: debates and politics 17

and tenaciously, and carried weight with Treasury ofcials. Neverthelessafter 1914 the Bank was always acutely aware of where the real powerlay. Even during the 1920s, a supposed peak of its inuence, it acceptedthat its monetary measures should take account of political considera-

tions, so contrary to gold standard rules it managed the exchangerate in order to minimise controversial bank rate increases. 40 Insulationfrom direct government intervention, though a form of power in terms of banking affairs, from the 1940s probably became a weakness in relationto economic policy, in that the Bank was detached from the processesof demand management. 41 From its perspective, assertions of indepen-dence, even including its efforts to have the gold standard restored in1925, were less demonstrations of strength than defensive or rearguardactions against the expansion of government and against political pres-sures for policies it regarded as harmful. After 1931 its sphere of inde-pendence contracted by stages, as the governments efforts to stabiliseand then, from the 1940s, to manage the economy intensied. Not until1970, however, did a Bank of England Governor state that the Bank isan arm of Government in the City though even then OBrien insistedon its special advisory role and his successor, Richardson, spoke of it as

having independence within government.42

Plainly enough, the keys toexplaining the Banks relative (but until the 1990s, declining) autonomyand to assessing the extent of City inuence lie in the attitudes andactions of the Treasury and the elected government.

The Treasury

Even more than the Bank of England, the Treasury manifestly had its

own distinctive concerns. For Ingham, this remains compatible with theCitys power because the Treasurys institutional interests within the statebureaucracy caused it to align itself with the Bank and the wider City.Certainly the Treasurys claims to be the chief department of governmentwere reinforced by its connection with the Bank as the main channel forbankinggovernment communications, and by their joint responsibilityfor monetary policy. It was a relationship which Treasury ofcials jeal-ously guarded, on occasion co-operating with the Bank to exclude partici-pation by other departments. 43 Negatively, though, Inghams point has

40 Moggridge, British Monetary Policy , chs. 79; Kynaston, The Bank of England and thegovernment, pp. 278.

41 M. Moran, The Politics of Banking. The Strange Case of Competition and Credit Control (1984 ), p. 24; Moran, Power, policy, pp. 545.

42 Kynaston, The Bank of England and the government, pp. 512; Moran, Monetarypolicy, p. 49.

43 A good ex ampl e, directed against the Board of Trade, is noted in George Pedens chapter

below, p. 131 .

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

32/394

18 Philip Williamson

an underexplored implication. Government relations with the City werenot conned just to the Treasury, and investigation of other departmentsor government agencies with interests and responsibilities in commer-cial and nancial affairs might complicate verdicts on the directions of

Citygovernment inuence. For example, the Foreign Ofce had assis-tance before 1914 from merchant bankers ready to lubricate its diplo-matic objectives with loans, and in the 1920s from the Bank of Englandsnancial diplomacy in its efforts to advance European re-stabilisation. 44

Between the wars the Colonial and Dominions Ofce resisted Treasuryand Bank efforts to ration imperial capital issues. 45 From the 1960s inves-tigations emanating from the Board of Trade and Department of Tradeand Industry forced the end of restrictive practices among clearing banksand in the Stock Exchange.

It is also true that the Treasurys responsibility for public nances nec-essarily made it attentive to the Citys nancial markets. Governmentdebt had to be made attractive to investing institutions, and these wantedto be sure of government efforts to maintain sound nance and to resistination. But this did not mean that the governments position was weakor dependent: the money markets and the banks needed the gilt-edged

securities and Treasury bills, as these formed the fundamental assets andinstruments for many of their activities. Nor did the Treasury requireBank or City pressure in order to balance the budget, restrain publicexpenditure, and check excessive public borrowing, because these wereprecisely its own functions. As George Peden has commented, the Trea-sury had its own reasons for pursuing policies of sound nance evenwhen these met the approval of the City. 46 It had its own reasons toofor supporting sound money and open markets, because aside from their

supposed economic benets it regarded these as supplying the economicdisciplines which reinforced its control of public nances. So, for exam-ple, the decisions from December 1919 to impose deation and returnto the gold standard were taken primarily on Treasury advice, reacting asmuch to chronic domestic budget and debt management problems as toBank of England concerns with the Citys international position. 47 Anywider City inuence was superuous. Although Treasury ofcials andChancellors of the Exchequer readily admitted their (surely inevitable)

44 P. Thane, Financiers and the British state. The case of Sir Ernest Cassel, BusinessHistory 28 ( 1986 ), 8099; Sayers, Bank of England , I, chs. 8, 15; but for later tensionssee Neil Forbess chapter 12 below.

45 See Bernard Attards chapter 10 below.46 G. C. Peden, The Treasury and Public Policy, 19061959 (Oxford, 2000 ), pp. 12, 518;

and see also his chapter 6 below.47 Howson, Domestic Monetary Management , pp. 1223, 259, 3343; Peden, Treasury ,

pp. 14058.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

33/394

City and government: debates and politics 19

reliance on the Banks expertise in the nancial markets, 48 such state-ments should not be mistaken for subservience towards the Bank, stillless the wider City, on broader nancial and economic issues. Althoughit was not until the late 1940s that the Treasury developed from a pub-

lic nance department into an economic ministry, George Peden, SusanHowson, Roger Middleton and Peter Clarke have shown that during theinterwar years its ofcials were already generating their own sophisti-cated economic understandings, which included the bearing of monet-ary conditions on the broader economy. 49 There seemed good reasonsfor regarding international nancial stability and the international use of sterling as benecial for the British economy; for considering the Citysoverseas earnings and its contributions to the balance of payments andto the demand for British manufactured exports as valuable for generaleconomic well-being; and, after the Second World War, for preserving theSterling Area and being worried about the potential damage of the ster-ling liabilities and an adverse balance of payments. There seemed goodreasons too for defending sterling and the credit of British banks againstinternational nancial panics or speculation, even if this meant askingfor assistance from foreign central banks or the International Monetary

Fund and as already noted, Treasury reactions to such crises shouldnot be equated in any simple way with responses to City interests. 50 Inthemselves these Treasury attitudes do not require explanation by generalnotions of Bank of England or City dominance over policy, though thisis not to deny that their inuence was signicant in particular Treasuryresponses.

Yet the Treasury always had to attend to far more than just Bank adviceand any further City interests. Examination of particular episodes sug-

gests not only that where it agreed with them it did so for its own purposes,but also that it was perfectly capable of rejecting their views or taking adifferent approach. It was quite unmoved by the City protest over the1909 increases in direct taxation, and despite the imposing gures behindthe 1920 City plan for the oating debt a remarkable (indeed ironic)proposal for a temporary addition to the already war-inated rates of

48 E.g. Kynaston, The Bank of England and the government, pp. 345.49 Peden, Treasury ; Howson, Domestic Monetary Management ; R. Middleton, Towards the

Managed Economy (1985), esp. chs. 3, 5, 8; P. Clarke, The Treasurys analytical modelof the British economy between the wars, in M. Furner and B. Supple (eds.), The Stateand Economic Knowledge (Cambridge, 1990), pp. 171207.

50 The point is well made for the mid 1960s in R. Stones, Governmentnance relationsin Britain 19647: a tale of three cities, Economy and Society 19 ( 1990 ), 3641, 52, butit applies also to other sterling crises from 1931 to 1992; and see the distinction made inRoberts and Kynaston, City State , p. 17, between City rms and international nancialmarkets.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

34/394

20 Philip Williamson

income tax and super-tax it dismissed it as politically impossible. 51

Once Treasury ofcials took overall charge of monetary policy after the1931 crisis they ignored the Banks wish to return once again to the goldstandard, and ensured that exchange rates and in te rest rates were sta-

bilised at levels which assisted industrial recovery. 52 While sympathetictowards the Banks efforts to restore market disciplines from the late1940s, over the following decades they could not accept its views on theextent to which the balance-of-payments and ination problems shouldbe met by public sector cuts and incomes policies. Indeed, for much of the century the levels of public expenditure and taxation were a recurrentsource of difference between them. Here the Treasury was itself usuallyghting rearguard actions, under Conservative governments as well asLiberal and Labour applying what brakes it could, but unable to arrestthe long-term trend towards increased spending and an expanding publicsector. It was not just that the Treasury could never wholly resist unwel-come pressures from the spending departments. Nor was it just that aspart of the government it could not ignore interests other than those of the City those of industry, labour, welfare recipients, and taxpayers. 53

The Treasury also had its own views on what constituted the best interests

of the government and the nation, perceptions which were independentof particular economic interests because its responsibilities were not justeconomic or nancial: it had also to help preserve the political stability,military security and diplomatic weight of the state. Most obviously of all, the Treasury was not a free agent.

Government and policy

The strongest claims for the Citys inuence on government have comefrom economic, social or Marxist studies. For political historians theseclaims have surprising features. One is their socio-economic reduction-ism, the narrowing of explanation to economic interests, nancial elitesor gentlemanly capitalists this at a time when even social history andstudies of popular movements and elections were abandoning or consider-ably qualifying notions of economic or social determination. Althoughthe concept of a CityBankTreasury nexus does emphasise an inde-pendent role of sorts for the Treasury, it practically ignores the mostpublic aspect of the state: the elected governments which, after all, hadnal responsibility for nancial and economic policies. Still less does it

51 Peden, Treasury , p. 45; Daunton, Just Taxes , pp. 778.52 Howson, Domestic Monetary Management , pp. 8095.53 In addition to the studies in note 49, see for a mor e recent period C. Thain, The Treasury

and Britains decline, Political Studies 32 ( 1984 ), 58195.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

35/394

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

36/394

22 Philip Williamson

next seventy years. These defeats on free trade, sterlings internationalstatus, taxation, Bank of England independence were the outcome notjust of inexorable forces of global economic change, but of governmentdecisions and political debate. Above all there was war. The activities

and prosperity of much of the City from the 1850s depended on a stableinternational economy: it needed peace, indeed from the 1890s someleading bankers made efforts to reduce Anglo-German tensions. 56 Incontrast to the governments eighteenth-century wars which stimulatedthe Citys development, those of the twentieth century were hugely dam-aging to the City. After 1945 both Labour and Conservative governmentsretained great-power aspirations, which gave them their own reasons forcontinuing to attach importance to the international strength of sterling.In 1964 it was very much the Labour leaderships decision to resist deval-uation. 57 Yet from the late 1950s there were growing Treasury and Bankdoubts about the nancial costs of post-imperial power politics and theviability of the sterling exchange rate, while a new nancial City wasemerging which dealt in currencies other than sterling, and had littleinterest in its fate. In domestic policies the priority that governmentsgave to social and political objectives, especially following the impact

of the two world wars, expansions of the electorate in 1918 and 1928and emergence of the Labour party, had similarly transforming effects.The increased provision of social services and from 1945 the commit-ments to full employment, demand management and nationalisation hadmajor implications for sound nance and the operations of the nancialsystem. Yet in these policy fundamentals the Bank of England had noinuence. As government grew hugely in size, scope and impact on theeconomy, and as political faith in the efcacy of the market declined or

was qualied (until the 1970s), so the signicance attached to Bank of England advice and City views on matters beyond the nancial marketsdeclined considerably. Just as the nature of the City changed during thecentury so, still more obviously, did that of government: verdicts aboutpolicy inuence over the long term are doubly hazardous.

The sources of and constraints upon economic policy have beencomplex, with party commitments and political manoeuvres being asimportant as ofcial advice, competing economic ideas and pressurefrom economic interest groups. Nor have these elements been discrete:what economic groups perceive as their interest could be shaped bypast or potential government action; City bankers could be inuenced

56 P. Thane and J. Harris, British and European bankers 18801914: an aristocraticbourgeoisie?, in P. Thane, G. Crossick and R. Floud (eds.), The Power of the Past (1984), p. 223.

57 A. Cairncross and B. Eichengreen, Sterling in Decline (1983 ), pp. 16093.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

37/394

City and government: debates and politics 23

more by their party allegiance than conventional views about theireconomic interests. 58 The concept of economic policy itself can be one-dimensional, if it is treated as unitary rather than as a set of policies.Given the party-political concerns of ministers and the pressures upon

them, these policies rarely had perfect economic coherence: their primaryrationale was political, not economic. As Rob Stones has argued, overallpolicy was the result of a fractured and fragile set of processes, withspecic policies pointing in different, even contradictory, directions asministers attempted to achieve several objectives and to placate numer-ous groups at once, with the effect that the government was placed inseveral different relationships with any particular group such as the Citybankers. His example is the Labour government in 19647 taking mea-sures to preserve condence in sterling, while simultaneously pursuingits own objective of domestic growth through credit and taxation poli-cies which the Bank of England and City nanciers intensely disliked. 59

Other cases can readily be found. During the early 1930s a display of strict budgetary orthodoxy helped sustain nancial condence at a timewhen cheap money, managed exchange rates and tariffs were being intro-duced. Assessment of the presence or degree of Bank or City inuence

may depend on the selection of the policy or policies being examined.Of course some, perhaps many, senior politicians took no interest in andwere ignorant of banking and monetary issues, leaving themselves at themercy of Treasury and Bank advice. Notoriously, Lord Passeld (SidneyWebb) as a former member of the 1931 Labour Cabinet declared afterthe suspension of the gold standard that nobody even told us we coulddo that. 60 But too much should not be concluded from such examples.As Anthony Howe, Ewen Green and Jim Tomlinson show, 61 each party

had politicians who were certainly not intimidated or much impressed byBank or even Treasury views. In contrast to the Labour ministers duringthe 1931 crisis, Conservative ministers in the new National Coalition gov-ernment were so self-assured in their own assessments of nancial con-dence and so intent on their party objectives that they ignored the Banksdirest warnings, until the Bank eventually concluded that further defence

58 Good instances of economic histories of policy which address its complexities, includ-ing the political dimensions, are J. Tomlinson, Public Policy and the Economy since1900 (Oxford, 1991 ), and R. Middleton, Government versus the Market. The Growthof the Public Sector, Economic Management and British Economic Performance c. 18901979 (Cheltenham, 1996 ).

59 Stones, Governmentnance relations in Britain, 33 and passim .60 As originally noted in Dalton diary, 12 Jan. 1932, quoted in Williamson, National Cri-

sis, p. 14. Matters had, however, been considerably more complicated than this artlessstatemen t imp lies: see Williamson, National Crisis , ch. 9.

61 Chapters 7 9 below.

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

38/394

24 Philip Williamson

of sterling was futile. 62 A common politicians view of City opinion wasthat it was hopelessly irrational, ckle, self-interested, politically unreal-istic, and anyway likely to be divided. 63 One striking suggestion aboutCity inuence, that it could be decisive in the choice of Chancellors of

the Exchequer, should be treated with sce pti cism: party and personalconsiderations were always more important. 64 Nevertheless, it may seemremarkable that governments for long left the Bank of England and thenancial City with substantial independence and that, with the excep-tion of the Labour party from 1931 to 1945, the political parties did notmake them subjects for political campaigns or election manifestos. Partof the explanation was the political promise, pressure or constraint of other, apparently more pressing, issues. Of greater importance were thesuccessive forms of governing political economy.

The politics of political economy

In the commonly Marxist or marxisant accounts of City hegemony overeconomic policy, the British state is assumed to have been a committee fororganising the affairs of the dominant socio-economic elite or alliance.

There is, however, a different understanding of the state which betterexplains the nature of government and policy over the last two centuries.By directing attention to the political aspects of the orthodox economicdoctrines inherited from the nineteenth century, this also explains theunusual position of the Bank of England and the City without makingexcessive claims about their power.

The purpose of the major nancial and commercial reforms from thelate 1810s to the 1850s was not simply economic. Faced with severe

social unrest and radical protest, the chief preoccupations of successivegovernments were political stabilisation, integration and legitimation. 65

62 Williamson, National Crisis , pp. 32830, 41016.63 E.g. Thane, Financiers and the British state, pp. 89, 95; Kynaston, City of London , III,

pp. 5, 62, 110; Daunton, How to pay for the war, pp. 9058.64 Cf. Boyce, British Capitalism at the Crossroads , pp. 21, 723, 380n.64, and Peden, Trea-

sury , pp. 12, 193, 430. There are difculties with the evidence adduced for the casesusually cited. That for the 1919 appointment consists of speculation by the Chancel-lor, Austen Chamberlain, not an explanation from the Prime Minister, Lloyd George.Baldwin as Prime Minister in 1923 and 1924 did mention City opinion, but only as onefactor and only in the context of trying to persuade a reluctant Neville Chamberlainto accept the chancellorship, statements unlikely to have revealed the main reasons forhis choice. Horne, supposedly disliked in the City for his 19212 chancellorship, hadnevertheless been Baldwins rst choice in 1923, and his refusal then (and changed partycircumstances) meant that there was no question of his being offered the post in 1924.The evidence for Lyttelton in 1951 is retrospective and ambiguous.

65 For this paragraph and the next, see P. Harling and P. Mandler, From scal-militarystate to laissez-faire state, Journal of British Studies 32 (1993), 4470; B. Hilton, Corn,

-

8/10/2019 michie government and the city.pdf

39/394

City and government: debates and politics 25

Senior politicians of all parties, sharing an autonomous ethos of goodgovernment, sought to defend authority, hierarchy and property in gen-eral, more than the interests of any specic economic group or sectionof the propertied classes. Indeed, in order to disarm radical criticism

and restore condence in established institutions, the agreed principlewas that government had to be seen to be free from dependence upon,obligation towards and pressure from particular interests including theBank of England and the City. Accordingly, as far as possible the stateceased to be a participant in economic activities. With the gold standard,the Bank Charter Act, free trade and balanced budgets, governments cre-ated a framework for free markets, an automatic mechanism for economicadjustments and rules for public nance. This was the political essenceof Victorian laissez-faire , later extended to that other highly sensitive area,industrial relations. A minimal, non-interventionist state that was or wassuccessfully presented as impartial towards competing interests wouldalso be a strong state, able within conventional political limits to pursueits own purposes and meeting little resistance in nancing its activities.

These reforms were carried against opposition from the Bank of England and City commercial interests, some of which were severely hit

by the loss of mercantilist and tariff legislation. On the other hand, thereforms assisted a new breed of merchants and nanciers able to exploitthe great expansion of the international and British economies from the1850s to 1914. Government had not just exerted its supremacy over theCity; however unintentionally, it had also taken a large part in reconstruct-ing its economic activities. Although in the event new City interests werebeneciaries of the reforms, it does not follow that the gold standard, freetrad e and sound public nance became their special ideological prop-

erty. 66 These doctrines and the associated concept of a disinterestedstate continued to serve the purposes of the political parties and gov-ernment ofcials, by excluding from politics a range of actions whichmight destabilise not just the nancial and economic system, but alsoeach partys political position and even the political system itself. Thesedoctrines also became embedded in general political culture, becausenotwithstanding some challenges from the 1880s they were on balance

Cash, Commerce (Oxford, 1977), esp. chs. 2, 8, and conclusion; Howe, Free Trade and Liberal England , pp. 1323, 5564; R. McKibbin, The Ideologies of Class. Social Relationsin Britain 18801950 (Oxford, 1990), pp. 2632, 38; P. Thane, Government and societyin England and Wales, 17501914, in F. M. L. Thompson (ed.), The Cambridge Social History of Britain 17501950 , 3 vols. (Cambridge, 1990), III, esp. pp. 2633; Daunton,Home and colonial, pp. 3516, and Daunton, Trusting Leviathan. The Politics of Taxationin Britain 17991914 (Cambridge, 2001), pp. 267, 378, 388.