Memo about Los Angeles Swap Deals

-

Upload

davidsirota -

Category

Documents

-

view

69 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Memo about Los Angeles Swap Deals

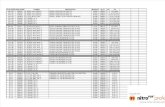

MEMORANDUM

To: Lisa Donner

Marcus Stanley

From: Ross Wallin

212 755 7876 [email protected]

Bradley Miller

212 897 9499

Date: June 24, 2014

Re: Disgorgement of Underwriter Gains from Violation of MSRB’s Fair Dealing Rule

As you requested, we have researched whether the SEC can bring enforcement actions

related to interest rate swaps and related securities transactions that public entities entered

into as part of complex municipal securities financings. We conclude that Americans for

Financial Reform and your member organizations have strong legal arguments to urge the

SEC to bring actions for disgorgement for the failure of underwriting banks to comply

with securities laws and regulations and disclose fully to public entities the risks of such

financings. Our research strongly suggests that underwriters may have failed in many

instances to meet the requirement to deal fairly with public entities as required by the

Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) fair dealing rule, Rule G-17. Claims for

civil penalties may be time-barred, but claims for disgorgement likely are not.

Developments in the Municipal Financing Market

Between 2002 and 2008, underwriters pitched to conservative issuers generally averse to

interest rate risk a new type of transaction designed to create “synthetic” fixed-rate debt

that would be cheaper for them than traditional, “natural” fixed-rate debt. To do so,

underwriters persuaded many public entities to issue debt with an interest rate that

changed weekly or monthly. To hedge the interest rate risk, underwriters encouraged

issuers to enter into interest rate swaps. The swaps required that the issuer pay a fixed

rate to the counterparty, usually the underwriter, and that the counterparty pay a

“floating” rate based on an index, usually Libor.

Investors in the variable rate debt – usually auction rate securities (ARS) or variable-rate

demand obligations (VRDOs) – could sell or “put” their securities on a weekly basis.

Investors in ARS could sell their securities in a weekly auction that usually was managed

by one of the underwriters; investors in VRDOs could sell their securities each week

through a “remarketing agent” – again, usually the underwriter or an affiliate – who

2

would sell the VRDOs to other investors. The VRDOs often would have a “liquidity

provider” in the form of a letter of credit or standby bond purchase agreement.

The interest rate on an issuer’s variable-rate debt was reset weekly at the level required to

“clear the market” of the securities that investors offered for resale that week. For ARS, a

“Dutch auction” set the weekly rate; for VRDOs, the remarketing agent set the rate. Both

ARS and VRDOs usually included an upper limit on the possible interest rate affecting

the risks to the issuer. VRDOs traditionally were capped at a fixed, maximum rate. ARS

traditionally were capped to a short-term index. Later, it became more common for ARS

to be capped at a high, fixed rate, which greatly increased the risk to issuers, but

protected the balance sheets of the underwriters.

The complex variable-rate financings were much more profitable for underwriters than

routine, fixed-rate financings. The financings required additional transactions that

generated additional fees, but the real profit for underwriters was from the interest rate

swaps. Few public officials or finance officers knew what a swap should cost, and the

swaps were the least discussed, least transparent, and most profitable transactions for

underwriters. The swaps were typically for terms of 20 or 30 years. By contrast, swaps in

the private sector that are designed to hedge similar interest rate exposure are very rarely

for terms of more than seven years.

Underwriters also assured issuers that the interest rate on the securities and on the index

upon which the swaps were based would move in tandem and played down the factors

that could cause the rates to diverge. The market conditions that determined the interest

rate for the variable-rate debt were very different from the market conditions that

determined the index rate, however.

A lot can go wrong in complex transactions, and a lot did go wrong. During the financial

crisis, market clearing interest rates shot up for many ARS and VRDOs. In most cases,

the interest rates shot up because investors became concerned about the creditworthiness

of liquidity providers and bond insurers, which resulted in concern that they might not be

able to exercise their puts on VRDOs or sell their ARS at auction. At the same time,

Libor, the index to which the swaps were usually tied, stopped moving in tandem with

the interest rates on ARS or VRDOs. Instead, Libor rates collapsed late in 2008 and were

then held down in an effort to revive the economy. As a result, the floating payments on

the swaps and the issuers’ variable-rate debt did not offset each other to produce a

“synthetic” fixed rate as advertised.

The mismatch of interest rates and changes in ARS structures has resulted in huge

financial losses for public issuers. Many have had to refinance or restructure their

VRDOs and ARS on highly disadvantageous terms. Others remain in the swaps, which

require significant payments because the fixed rate the public issuers agreed to pay is so

much higher than the Libor rate they receive. Moreover, because the swaps typically are

for terms of 20 or 30 years, the termination fees required to get out of the transactions are

often exorbitant.

3

Fair Dealing – MSRB Rule G-17

There is a strong argument that underwriters on these transactions did not comply with

Rule G-17 of the MSRB. Rule G-17 requires that “[i]n the conduct of its municipal

securities…activities,” an underwriter “shall deal fairly with all persons and not engage

in any deceptive, dishonest, or unfair practice.”

In numerous statements over the past 17 years, the MSRB has stated that Rule G-17

obligates underwriters to deal fairly and not engage in unfair practices with municipal

issuers. See Interpretive Letter, Purchase of New Issue from Issuer (Dec. 1, 1997);

Interpretive Notice Regarding G-17, on Disclosure of Material Facts (Mar. 18, 2002);

Reminder Notice on Fair Practice Duties to Issuers of Municipal Securities (Sept. 29,

2009). Moreover, the MSRB has emphasized repeatedlythat whether or not an

underwriter has dealt fairly with a municipal issuer depends on the “facts and

circumstances of an underwriting.” E.g., Interpretive Letter (Dec. 1, 1997).

To comply with Rule G-17, underwriters must explain complex transactions in an

understandable way to issuer personnel and disclose material risks. In addition, they must

not encourage municipal issuers to enter into transactions that serve the underwriter’s

interest, without any regard for the issuer’s interest. Indeed, it is hard to imagine how an

underwriter could deal fairly with a municipal issuer if the underwriter failed to satisfy

these rudimentary requirements.

In 2012, the MSRB issued an Interpretive Notice that focused specifically on the types of

transactions described in this memorandum. See Interpretive Notice Concerning the

Application of MSRB Rule G-17 to Underwriters of Municipal Securities (Aug. 2, 2012).

That Interpretive Notice, like many before it, reiterates the longstanding requirement that

underwriters deal fairly with municipal issuers. In addition, it highlights the obligation of

underwriters to explain complex transactions and the risks associated with them to

municipal issuers. Specifically, it notes that underwriters must disclose “material

financial risks,” such as “market, credit, operational, and liquidity risks” in a “fair and

balanced manner based on principles of fair dealing and good faith.” Id. MSRB Guidance

concerning the Interpretative Notice states also that underwriters should not treat their

communications with issuers as “merely a sales pitch without regulatory consequence.”

See Guidance on Implementation of Interpretive Notice Concerning the Application of

MSRB Rule G-17 to Underwriters of Municipal Securities (July 18, 2012).

We believe that it is appropriate to read the 2012 Interpretive Notice largely as

expounding on the long-standing obligations of underwriters under the Rule. Guidance on

the Interpretive Notice states specifically that, “[a]lthough many of the specific elements

identified by the Notice are fully articulated by the MSRB for the first time, all of them

4

arise from the fundamental duty of fairness to the issuer that the MSRB has already

required under Rule G-17 for some time.” Guidance (July 18, 2012).1

The various Interpretative Notices of the MSRB also are consistent with the requirements

of the common law of fraud and misrepresentation. In a recent arbitration, an Alabama

private utility, Baldwin County Sewer Service, prevailed in a claim against Regions Bank

related to a similar financing.2 There, the bank advised the private utility that variable-

rate bonds in combination with an interest rate swap based on Libor would create a

synthetic fixed rate for the utility that would be cheaper than natural fixed-rate debt. In

fact, the arbitrators found, the bank recommended the transaction because it was more

profitable for the bank than “the usual interest-bearing direct loans.” Rather than moving

in tandem, interest rates on the debt went dramatically higher while Libor went down.

The arbitrators noted that the transaction documents were “thousands of pages” and filled

with language that the arbitrators described as “arcane,” “rather obtuse,” and “esoteric.”

The general counsel for the utility “admitted his confusion in interpreting the language”

that described how the interest rate on the debt was determined. The arbitrators were not

troubled by the boilerplate statements in the documents in which the utility acknowledged

that it had read and understood all of the terms of the agreements and had not relied on

any representations by the bank. The arbitrators concluded that the utility reasonably

relied on the bank’s representations given the “relative sophistication and bargaining

power of the parties,” and granted the utility rescission of the swaps under the Alabama

common law of misrepresentation.

Potential Enforcement Actions by the SEC for Disgorgement

Many complex municipal securities financings suffered from some of the same defects as

the Baldwin County transaction. Specifically, we believe that underwriters often

recommended complex municipal securities financings that included swaps because the

transactions were more profitable for the underwriter, not cheaper for the issuer. In

addition, the disclosures of significant known risks were not “fair and balanced” but

rather were often missing or misleading or at best buried in legal jargon.

The SEC has enforcement authority for violation of the MSRB’s Rules. The SEC

routinely seeks and courts routinely grant disgorgement of ill-gotten gains from

violations of the federal securities laws. Disgorgement actions generally are not subject to

the five-year statute of limitations for “a fine, penalty, or forfeiture.” 28 U.S.C. Section

2462. Rather, the SEC and courts regard disgorgement as an equitable remedy that

“deprives wrongdoers of the profits obtained from their violations.” Zacharias v.

Securities and Exchange Commission, 569 F.3d 458, 472 (D.C. Cir. 2009). See also

Riordan v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 627 F.3d 1230, 1234 n.1 (D.C. Cir.

2010) (“It could be argued that disgorgement is a kind of forfeiture…where the

1The 2012 Interpretive Notice did provide new guidance on the “manner and timing” of certain disclosures. See

Guidance (July 18, 2012). 2The arbitration ruling is available at

http://www.al.com/business/index.ssf/2014/05/regions_to_pay_10_million_for.html#Arbitration ruling.

5

sanctioned party is disgorging profits not to make the wronged party whole, but to fill the

Federal Government’s coffers…. Here…the disgorged moneys will apparently be

returned to the New Mexico State Government and not retained by the U.S.

Government.”).

To discuss this further, please contact:

Ross Wallin (212) 755-7876 [email protected]

Brad Miller (212) 897-9499 [email protected]