Mechanical Circulatory Support - HIGHLAND CARDIOLOGY€¦ · Mechanical Circulatory Support John C....

Transcript of Mechanical Circulatory Support - HIGHLAND CARDIOLOGY€¦ · Mechanical Circulatory Support John C....

-

Mechanical CirculatorySupport

John C. Greenwood, MDa,*, Daniel L. Herr, MDb

KEYWORDS

� Mechanical circulatory support � Intra-aortic balloon pump� Ventricular assist device � Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)� Cardiogenic shock

KEY POINTS

� The routine use of an intra-aortic balloon pump is no longer recommended for patientswith refractory cardiogenic shock.

� Common ventricular assist device (VAD) complications include thrombosis, bleeding,right-sided heart failure, infection, cerebral vascular accidents, arrhythmias, and devicefailure.

� Driveline infection is the most common infectious complication for the patient with a VAD.� Ventricular arrhythmias are most common within the first 3 months after VAD placementand should be cardioverted in a timely fashion.

� Venoarterial ECMO is a treatment modality that can be considered in the patient with re-fractory cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest from a reversible cause.

INTRODUCTION

Mechanical circulatory support, a term that most emergency physicians did notconcern themselves with 10 years ago, is now an area of patient care that emergencyphysicians must understand. The role of mechanical support for both acute andchronic heart failure is rapidly growing. For example, as of April 2012 more than10,000 HeartMate (Pleasanton, CA, USA) left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) hadbeen implanted, yet only a handful of the patients who received these devices willgo on to receive a heart transplant.1 Most of these patients will never receive a trans-plant and will spend most of their time receiving outpatient care. The use of extracor-poreal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for refractory cardiogenic shock and cardiac

Funding Sources: Nothing to disclose.Conflict of Interest: Nothing to disclose.a Division of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine,110 South Paca Street, 2nd Floor, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA; b Critical Care Service, Cardiac Sur-gery ICU, Shock Trauma Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 22 South GreeneStreet, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA* Corresponding author.E-mail address: [email protected]

Emerg Med Clin N Am 32 (2014) 851–869http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2014.07.009 emed.theclinics.com0733-8627/14/$ – see front matter � 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

mailto:[email protected]://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1016/j.emc.2014.07.009&domain=pdfhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2014.07.009http://emed.theclinics.com

-

Greenwood & Herr852

arrest is also rapidly growing. As of January 2013, more than 200 centers providesome type of extracorporeal support and more than 4200 cardiac patients havebeen treated by extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).2

This review has several purposes: (1) to discuss the use of the intra-aortic balloonpump (IABP) in patients with cardiogenic shock, (2) to describe the complicationsand management strategies for the critically ill patient with an LVAD, and (3) to explorethe emerging role of ECMO in the emergency department for patients presenting incardiac arrest.

IABP

The IABP has classically been regarded as the mainstay of mechanical support for pa-tients in cardiogenic shock (CS). This device provides hemodynamic support by aug-menting diastolic arterial blood pressure during the normal cardiac cycle. Byincreasing diastolic blood pressure, IABP counterpulsation is believed to improve cor-onary perfusion, reduce myocardial oxygen demand, and reduce left ventricular after-load during systole.3 IABP therapy is the most widely used form of mechanicalhemodynamic support in patients with CS secondary to acute myocardial infarction.4

Historically, American and European guidelines have recommended the use of IABPtherapy, giving it a class IB and class IC recommendation, respectively.5,6 However,an emerging body of literature questions the outcome and mortality benefits ofIABP therapy for CS associated with acute myocardial infarction (AMI).7–9 As a result,American and European guidelines have downgraded the use of IABP therapy to classIIa and IIb recommendations, respectively.10–13

Despite the recent controversy surrounding the routine use of IABP therapy, it isimportant for the emergency physician to be aware of the traditional indications foran IABP, the mechanisms of support, and the contraindications. The traditional indica-tions for IABP insertion include refractory CS caused by AMI, refractory unstableangina, and mechanical causes, such as acute mitral regurgitation, papillary musclerupture, and ventricular septal defect. Generally accepted contraindications to coun-terpulsation therapy are aortic insufficiency, aortic dissection, and chronic end-stageheart failure with no anticipation of recovery.Thedeviceconsistsof adouble-lumen8.0-French to9.5-Frenchcatheterwith a25-mL

to 50-mL balloon at the distal end. The IABP catheter is inserted percutaneously using aSeldinger technique through the femoral artery. Traditionally, the IABP balloon is placedafter measuring the distance from the insertion point to the manubrium, followed byconfirmation with a chest radiograph, or alternatively it can be placed under direct fluo-roscopic guidance. Ultrasound is also being used to guide tube placement at some cen-ters.14 The balloon itself is positioned 2 to 3 cm distal to the left subclavian artery and isinflated during the diastolic portion of the cardiac cycle.Evidence behind the use of IABP therapy for refractory CS has historically been

mixed, especially for CS secondary to myocardial infarction. There is some evidencethat IABP therapy reduces preoperative mortality in a subset of patients, includingthose with CS secondary to acute mitral regurgitation or a ventricular septal defect af-ter myocardial infarction.15 The routine use of IABP therapy in refractory CS has fallenout of favor. A meta-analysis performed on the use of IABP in ST-elevation myocardialinfarction (STEMI) found insufficient evidence to routinely recommend this therapy.16

These findings were followed by the IABP Shock-II Trial, a multicenter, randomized,prospective study,8,9 which found no significant reduction in short-term (30-day) orlong-term (12-month) all-cause mortality for patients in CS related to AMI undergoingearly revascularization. Despite these observations, a small subset of patients,

-

Mechanical Circulatory Support 853

specifically those with acute mitral regurgitation or ventricular septal defect, couldbenefit from this intervention. Therefore, it may be considered as a temporizing mea-sure while the patient is being prepared for the operating room.

VENTRICULAR ASSIST DEVICE

Ventricularassistdevices (VADs)arebeingusedmorecommonly todayasadurable formofmechanical circulatory support, especially for patients awaiting long-term recovery ortransplantation. It is important that the emergency physician be able to recognize thetype of device, and become aware of the indications and complications for this type ofmechanical circulatory support, as well as how to promptly manage them.There are 3 major indications for placement of a VAD. Similar to most other mechan-

ical circulatory devices, VADs are used as either a bridge to transplantation, bridge torecovery, or destination therapy. Permanent LVAD implantation (destination therapy)can be performed in certain patients with advanced heart failure and a low chanceof transplant.17,18 In some patients, a VAD can be considered as a “bridge to decision”when more time is needed to determine if further definitive treatment would benefit thepatient.19 In the most recent American College of Cardiology Foundation/AmericanHeart Association STEMI guidelines, VADs were given a IIa recommendation as analternative treatment for refractory CS.11

There are 2major types of VADs, which are classified by their mechanism of support.Older, first-generation VADs provide circulatory support through a pulsatile flow pumpthat is driven by a pneumatic motorized pump. Except for patients with right ventricularfailure, these devices are less frequently used today. The older, external VAD pumpsare large and bulky, which decreases the patient’s mobility. Pulsatile VADs requirefrequent pump exchanges, which makes them less desirable as well.Newer-generation VADs provide circulatory support though continuous-flow pumps

that work by axial or centrifugal flow. Continuous-flow pumps have a number of ad-vantages over the older, pulsatile-flow devices. They are often smaller, more durable,and have higher energy efficiency and lower thrombogenicity. These devices are sur-gically implanted and have minimal external hardware.VAD commercial brands include the Heart Assist 5 (Houston, TX, USA), HeartWare

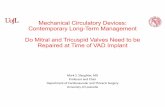

HVAD (Framingham, MA, USA), Jarvic 2000 (New York, NY, USA), and Thoratec Heart-Mate II (Pleasanton, CA, USA). The most common LVAD in use today is the axial flowHeartMate II; however, with recent advances in VAD technology, the HeartWare cen-trifugal flow device is now more commonly inserted. The centrifugal pumps are con-nected directly to the patient’s left ventricle and lie within the pericardium (abovethe diaphragm). Blood returns to the ascending aorta by way of a separate return can-nula. Axial flow pumps have a left ventricular outflow cannula that is connected in se-ries to an intracorporeal pump located either above or below the diaphragm (Fig. 1).The evaluation and management of a patient with a VAD can be challenging. It is

important that the emergency physician be aware of common complications thatcan occur with VAD patients, as well as the laboratory and diagnostic tests that shouldbe considered. During the initial evaluation, it is important to ask the patient or thepatient’s family how to contact their VAD coordinator and cardiothoracic surgeon.These contacts are often able to provide vital information about the patient and canhelp coordinate the patient’s care and disposition through the emergency department.The initial evaluation of any VAD patient should begin with a thorough initial history,

physical examination, and laboratory testing. When evaluating the device, the firststep should be to auscultate the motor to listen for a characteristic “hum” to ensurethe device is running.

-

Fig. 1. The appearance of different LVAD pumps on chest radiograph. (A) Jarvic 2000 post-auricular driveline placement. (B) Jarvic-2000 abdominal placement. (C) HeartWare centrif-ugal flow device. (D) Thoratec HeartMate II.

Greenwood & Herr854

Assessing vital signs can be challenging in the patient with a continuous-flow de-vice. These patients often lack central or peripheral pulses if the patient’s intrinsic car-diac contractility is poor. Therefore, their blood pressure should be measured with amanual blood pressure cuff and arterial Doppler. To obtain the mean arterial pressure(MAP), locate either the brachial or radial artery with your Doppler device. Inflate thecuff until you no longer hear auditory flow, then slowly release pressure from themanual cuff. The patient’s MAP is determined at the pressure where arterial flow isheard. The goal MAP is between 70 and 80 mm Hg, with a maximum of 90 mm Hg.Excessive elevations in blood pressure can significantly increase the risk for stroke.Consider arterial line placement early, as this will provide continuous, accurate mea-surements of the patient’s MAP. Closely examine the VAD driveline for signs of infec-tion, damage, or bleeding (Fig. 2). Last, review the patient’s control box for any alarmsand ensure the VAD has adequate battery power (Fig. 3).Pulse oximetry also can be difficult to obtain, and may be unreliable in patients with

a subtle pulse or no pulse. It is important to confirm low values with a rapid arterialblood gas sample.VADs are preload dependent. For a VAD to run efficiently, the patient’s intravascular

volume must be filled appropriately. Hypovolemia can lead to a reduction in VADpower secondary to reduced blood flow.

-

Fig. 2. Abdominal driveline location with surrounding erythema concerning for cellulitis.

Mechanical Circulatory Support 855

These devices are also afterload sensitive. Uncontrolled increases in MAP higherthan 90 mm Hg will often reduce LVAD power, flow, cardiac output, and distal perfu-sion. Patients with a MAP greater than 80 are at increased risk of cerebral vascularevents (ie, hemorrhage, ischemia) and should be treated promptly with afterload-reducing medications.20 A flow diagram for the differential diagnosis based on com-mon VAD alarms is presented in Fig. 4.

Common VAD Complications

Common complications associated with VADs include thrombosis, bleeding, right-sided heart failure, infection, cerebral vascular accidents, arrhythmias, and device fail-ure. Patients with VADs are at increased risk for bleeding complications, as they areusually on chronic systemic anticoagulation (ie, Coumadin [warfarin]) and antiplatelettherapy (ie, aspirin, dipyridamole). The most common international normalized ratio(INR) target for patients with LVADs is 2.0 to 3.0; however, patients with a HeartWaredevice target a slightly higher INR of 2.5 to 3.5. The most commonly reported types ofbleeding that VAD patients encounter are epistaxis, gastrointestinal, mediastinal, andintracranial hemorrhage.21 Hemorrhagic events are commonly caused by a suprather-apeutic INR, intestinal arteriovenous malformations, or bleeding dyscrasias, such asacquired von Willebrand disease.22,23

Fig. 3. HeatWare control box and battery packs. (A) Battery/power bar. (B) Alarm notifica-tion light. (C) Extra battery packs.

-

Fig. 4. Common VAD complications and their associated control box alarms. LV, leftventricular.

Greenwood & Herr856

Treatment of the bleeding VAD patient should begin with standard therapy toreverse an elevated INR with fresh frozen plasma or prothrombin complex concen-trate, if available. Platelet dysfunction due to acquired von Willebrand disease is com-mon and is believed to be the result of platelet exposure to the mechanical sheerstress that occurs with continuous-flow devices.22,24 Treatment with desmopressinor cryoprecipitate may be effective. Platelet transfusions may also be necessary ifthe patient is taking antiplatelet medications. Rapid thrombelastography may assistin targeted blood component therapy to reverse coagulopathy.25

VAD pump thrombosis should be considered in any patient presenting with cardiacarrest, decreased pump flow, pump power spikes, recurrent heart failure, or echocar-diographic findings that raise concern for abnormal left ventricular unloading.26

Thrombosis is a worrisome long-term complication, as it can result in stroke, periph-eral embolism, heart failure, and death.27,28 Thromboembolic events have been re-ported in 2.7% to 35.0% of all patients.29 HeartMate devices were once thought tohave a lower incidence of thrombosis of approximately 3%, because of their specificmechanical design.30,31 However, a recent study detected a rapid increase in Heart-Mate II VAD thrombosis: up to 8.4% at 3 months for devices implanted after 2011.32

The reason for this increase is unclear.Pump thrombus should be suspected if hemolysis is detected by laboratory studies, if

the lactate dehydrogenase is greater than 1500mg/dL or 2.5 to 3.0 times the upper limitof normal, if the patient has hemoglobinuria, or if the plasma-free hemoglobin level iselevated.21,26,33 Systemic anticoagulation with a continuous heparin infusion shouldbe initiated if pump thrombosis is suspected. The VAD teamshould be consulted quicklyto discuss emergent treatment options, including thrombolytic agents, antiplatelet ther-apy, and the potential need for emergent surgical pump replacement or explantation ofthe device.Suction (or “suck-down”) events can occur in patients with decreased left ventricular

filling caused by right ventricular failure, restrictive or hypertrophic cardiomyopathies,arrhythmias, or hypovolemia.20,34 These patients often present with hypotension.Suck-down events can be visualized under bedside echocardiography as the left ven-tricular chamber being equivalent in size to theVADcannula (Fig. 5). Prompt recognitionand treatment with an intravenous fluid bolus can reverse this problem rapidly.

Infectious Complications

Infectious complications are a major concern for patients with implanted hardwareand can occur anywhere along the device circuit. Driveline, pump pocket, and deviceinfections can be devastating and occur most frequently within the first 3 months after

-

Fig. 5. A suck-down event visualized by bedside echocardiography.

Mechanical Circulatory Support 857

placement, although they can occur at any time.35,36 VAD infections are themost com-mon cause of death among patients who require this device for long-term mechanicalcirculatory support.35

The most common location of infection is the driveline insertion site. Patients withinfected hardware often present with symptoms of malaise, low-grade fever, andmild tenderness around the driveline. The most common infecting organisms areskin and gastrointestinal pathogens: Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epider-midis, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, and Klebsiella species.37–40

Fungal infections have been reported and are estimated to occur in approximately9% of VAD patients. Candida infections are less frequent than bacterial infectionsbut are responsible for the highest mortality rates.41–43

During implantation, the VAD pump is commonly placed within the pericardium, inan anatomic “pocket” within the intra-abdominal cavity, or in the preperitoneal spacebelow the lateral rectus muscle. The “pump pocket” is at risk for infection because it iscontiguous with the driveline. Consider a pump pocket infection in VAD patients pre-senting with fever, leukocytosis, and abdominal pain, especially in the setting of adriveline infection.36,44 An abdominal ultrasound or computed tomography scan ishighly recommended to identify a VAD-related fluid collection or abscess.Pump endocarditis can occur when the hardware itself becomes colonized with a

bacterial pathogen. The presentation is similar to that of nonmechanical endocarditis.Symptoms include low-grade fever, signs of septic emboli on physical examination,and even pump obstruction. Sources include the driveline infection, transient bacter-emia or fungemia, and other health care–associated infections from urinary or pulmo-nary sources.45 Pump endocarditis carries a particularly high mortality, estimated tobe as high as 50% in several case series.46,47

Treatment of any suspected VAD infection should begin with aggressive fluidresuscitation to maintain adequate preload. Early broad-spectrum antibiotic

-

Greenwood & Herr858

administration should include treatment for both methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA)and gram-negative bacterial infections. Empiric antifungal therapy should probably begiven as well. Definitive source control with surgical drainage of the localized fluidcollection, device exchange, or explantation for transplant is often required.

Arrhythmias

Patients with a VAD may present to the emergency department with cardiacarrhythmia, classified as either primary or secondary, based on the underlying cause.Primary arrhythmias are intrinsic to the electrical conduction pathways of the heart

and occur independently of the VAD itself. Ventricular arrhythmias are common andcan be caused by cannula migration, malposition over time, electrical remodeling,secondary scaring, or fibrosis.48,49 Because the patient’s cardiac output is supportedby the VAD, primary arrhythmias, such as a supraventricular tachycardia or ventriculartachycardia, are often tolerated without clinical signs or symptoms.50

A persistent primary arrhythmia can eventually cause right ventricular failure andreduced left ventricular filling, ultimately leading to reduced cardiac output. As a result,primary arrhythmias should be managed in a timely fashion with cardioversion or anti-arrhythmicmedications. There is limited evidence to guide the choice of antiarrhythmicmedication inpatientswith aprimary arrhythmia.Amiodarone isoftenusedasa first-lineagent, although the use of b-blockers can also be considered. Mexiletine can be givenduring in-patient management for refractory ventricular tachycardia.48,49

Secondary causes of cardiac arrhythmias can occur if the left ventricular septum orfree wall is sucked into the VAD outflow tract. Hypovolemia and inadequate pulmonaryvenous return are the most common causes of a secondary arrhythmia.51

In the emergency department, it is often difficult to determine whether the patient’sarrhythmia has a primary or secondary cause. The management of any VAD patientpresenting with an abnormal rhythm should begin with a prompt fluid challengefollowed by an emergent bedside echocardiogram to determine if the patient wouldbenefit from more aggressive volume resuscitation or adjustments of the VADsettings.

Mechanical Failure

Pump failure is one of the most feared complications in VAD patients. Signs of pumpfailure include an absence of detectable blood pressure by Doppler, the absence of arunningmotor on auscultation, or the absence of power displayed on the VAD’s controlbox. If pump failure is suspected, it is important to immediately contact the patient’scardiothoracic surgeon, VAD engineer, and on-call nurse to obtain vital informationabout the make and model of the hardware.In any patient without evidence of perfusion (eg, MAP

-

Mechanical Circulatory Support 859

contraindicated. If the patient continues to have a MAP of zero after 1 minute, connectthe patient’s manual hand pump or initiate chest compressions.

ECMOOverview

Over the years, major advances in technology have increased the availability and abil-ity to use ECMO as a viable form of prolongedmechanical circulatory support. The his-torical roller pumps used for cardiopulmonary bypass were associated with higherrates of pump-induced hemolysis and lower flow rates compared with the newer cen-trifugal pump heads.52,53 The transition from older bubble-type oxygenators to newerhollow-membrane silicone oxygenators has also reduced blood trauma significantly,allowing increased duration of extracorporeal support.54

Two major forms of ECMO circuits are used today. Venovenous ECMO (VV ECMO)is used primarily for patients in refractory respiratory failure. Currently there are no uni-versally agreed on indications for the initiation of VV ECMO, but general indicationsinclude refractory hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and the failure of conventional mechanicalventilatory strategies.55 In general, initiation of VV ECMO is rare in the emergencydepartment, because this modality is chosen well after more advanced resuscitationmeasures have been attempted.VV ECMO can be considered the “ultimate” form of lung rest therapy, as ventilator

strategies can be used to minimize barotrauma, volutrauma, and biotrauma. In the pa-tient with refractory respiratory failure on ECMO, it is generally acceptable to followARDSnet ventilation strategies (between 4 and 8 mL/kg of ideal body weight, withplateau pressures

-

Fig. 6. (A) Maquet CARDIOHELP ECMO circuit. (B) Centrifugal pump. (C) Silicone membraneoxygenator.

Greenwood & Herr860

VV ECMO cannulation can be performed by a number of methods under ultrasoundor fluoroscopic guidance. Traditionally, two 21-French to 28-French cannulas areused. Deoxygenated blood is removed from the inferior vena cava by way of a multi-port cannula inserted into the right femoral vein and advanced to the level of T11/T12.It is important to avoid advancing this catheter higher than approximately the level ofT8, as this can lead to hepatic vein obstruction. Deoxygenated blood is then sent tothe pump’s oxygenator and finally returned to the right heart through a cannulainserted into the right internal jugular vein.Access can also be obtained by placing a single, 23-French, dual-lumen catheter

(eg, Avalon) in the right internal jugular vein. When using a single-cannula, bicavalapproach, the internal jugular ECMO catheter is advanced through the right atriumso that the proximal drainage port rests in the superior vena cava and the distalport rests just beyond the cavoatrial junction in the inferior vena cava.58 Oxygenatedblood is returned through a separate cannula by way of a central port located in theright atrium to provide flow across the tricuspid valve.VA ECMO cannulation can be performed centrally in the operating room under

direct vascular visualization, but is more frequently being performed percutaneouslyat the patient’s bedside. Using a Seldinger technique with serial dilations, a

-

Mechanical Circulatory Support 861

21-French venous catheter is inserted into the common femoral vein and a 15-Frenchor 17-French arterial catheter is inserted into the contralateral femoral artery. Thearterial catheter is advanced to the distal aorta to deliver retrograde blood flow forperfusion.The catheter can be directly visualized with fluoroscopy or ultrasound. A great deal

of care must be taken when performing the serial dilations to avoid laceration of thefemoral vessels. Complications such as acute embolism/thrombosis, commonfemoral artery dissection, perforation, and compartment syndrome can be devas-tating.59 Once the femoral arterial cannula is in place, it is important to monitor for crit-ical limb ischemia. A supplemental backflow cannula can be placed distal to theascending arterial cannula in the superficial femoral artery to provide blood flow ifthere is concern for limb hypoperfusion.60,61 After cannulation, initial cardiac outputtargets of 1.5 to 2.0 L/min are acceptable but should be titrated up gradually to 3.0to 6.0 L/min. Because arterial flow will be continuous, a pulse pressure of approxi-mately 10 mm Hg is considered acceptable.62

During VA ECMO, the retrograde aorta-to-left ventricular pressure gradient is veryhigh, but the aortic valve should be able to function normally. A post cannulation trans-esophageal or transthoracic echocardiogram should be performed to check for properopening of the aortic valve, aortic regurgitation, left ventricular distention, and tampo-nade.63 Although usually unnecessary, vasopressor and inotropic agents are occa-sionally required to reach target blood pressure and cardiac output, respectively.Unlike VV ECMO, which allows the left heart to provide pulsatile flow to the systemic

vasculature, VA ECMO provides continuous blood flow through the arterial system. Af-ter initiation, VA ECMO usually rapidly reduces pulmonary arterial pressures, improvesend-organ perfusion, and increases PaO2. For the postarrest patient, the pump’s heatexchanger can be used to facilitate targeted temperature management.

Clinical Uses for ECMO

Toxic overdosesMedical management of most cardiotoxic ingestions remains largely supportive, asthe effects of these toxic ingestions are often self-limited. A number of case seriesand reports have been published about the utility of VA ECMO in the overdose patientpresenting with refractory CS. For patients presenting early to medical centers withpersonnel experienced with extracorporeal support, this technology can be used asa bridge to recovery.Cardiovascular failure is a leading cause of death in patients with severe, acute drug

intoxication.64–66 In 2010 alone, cardiovascular medication overdoses accounted for9.4% of all fatalities. According to the American Association of Poison Control Cen-ters, calcium-channel and beta-blocking medications were involved in 30% of theseoverdoses and accounted for more than 45% of deaths related to cardiovascularmedications.64

A growing body of literature supports the use of VA ECMO in the overdose patient,especially when the offending agent leads to refractory CS or arrhythmias. Case seriesdescribe overdoses with diltiazem, verapamil, flecainide, acebutolol, and other antide-pressants agents.67–72 In many of these reports, VA ECMOwas instituted early to pro-vide effective perfusion and avoid multiorgan dysfunction. After the initiation ofextracorporeal support, the duration of therapy was generally less than 1 week.

MyocarditisOne well-described use of ECMO is in fulminant CS secondary to acute myocarditis.Infective myocarditis is an acquired inflammatory muscle disorder that is more

-

Greenwood & Herr862

common in the pediatric patient population.73 It can be caused by a wide spectrum ofinfectious organisms, as well as toxic and hypersensitivity reactions. Viral pathogensare the most common offending agents, specifically parvovirus B19 and humanherpes virus 6.74,75

Fulminant myocarditis is characterized by the presence of hypotension, respiratoryfailure, and signs of end-organ hypoperfusion. For patients presenting in shock, initialmanagement often requires mechanical ventilation, inotropic agents, and vasopres-sors. If the patient is unresponsive to initial medical management, mechanical circula-tory support might be required. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation appears to bean effective therapy for these patients and can be used as a bridge to recovery.76

The decision to initiate mechanical circulatory support can be difficult, becausethere are no absolute indications. Most experts agree that the decision to initiateECMO should be strongly considered in the patient presenting with acute end-organ dysfunction, a refractory ventricular arrhythmia, or cardiac arrest.77

ECMO for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and ECMO-assisted CPR (eCPR)The utility of ECMO in managing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is perhaps one of themost exciting developments in the expanded role of extracorporeal support. Histori-cally, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes remained poor despite advances inACLS protocols and the use of conventional CPR. Return of spontaneous circulation(ROSC) rates are regularly reported to be less than 40%. Additionally, survival to hos-pital discharge rates range from 7% to 11%, and for those who do leave the hospital,favorable neurologic outcome is achieved in only 3% to 5%.78,79 Outcomes haveimproved with post-ROSC therapeutic hypothermia,80,81 rapid defibrillation,82 cardio-cerebral resuscitation,83–85 and rapid revascularization.86,87

Initiating ECMO for a patient in cardiac arrest remains a heroic procedure, with asmall body of growing literature to support its use. In general, there is a lack of largerandomized trials evaluating the efficacy of eCPR. Most of the published reports sup-porting its use are case reports and small observational studies with heterogeneouspatient populations.Appropriate patient selection is critical, as the use of ECMO should be only a tempo-

rizing, not definitive, treatment strategy. Accepted indications include a brief arrestperiod, a condition believed to be reversible (such as coronary occlusion, refractoryarrhythmia, or toxin-induced arrest), or a condition that is amenable to transplantationor rapid revascularization. There are a number of suggested contraindications toeCPR, which are listed in Box 1. With respect to the duration of CPR, most publishedreports have included only those who had not achieved ROSC within 10 to 30 minutesof conventional CPR.88–91

Box 1

Common exclusion criteria for initiation of ECMO-assisted CPR

� History of severe neurologic damage� Intracranial hemorrhage� Terminal malignancy� Traumatic arrest with uncontrolled bleeding� Unwitnessed arrest or prolonged arrest� Aortic dissection� Severe peripheral arterial disease

-

Mechanical Circulatory Support 863

A number of studies have reported improved survival and neurologic outcomes withthe useof eCPR for patientswith in-hospital cardiac arrest.89,92,93Whenusedasabridgeto revascularization in patients who experienced cardiac arrest due to ST-elevationmyocardial infarction, a significant 30-day mortality benefit has been achieved.92

More importantly, for thosewith a primary cardiac cause of arrest or shock, an improved6-month survival with minimal neurologic impairment has been reported.93

The ability to initiate ECMO for patients presenting to the emergency departmentwithout-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) has become possible with advances in ECMOtechnology. In 2012, Bellezzo and colleagues94 published a staged approach for theinitiation of ECMO for OHCA in the emergency department. This small study demon-strated that ECMO can be initiated in the emergency department and, if done carefully,can significantly improve neurologic recovery. Larger reports have shown a significant30-day survival and improvement in neurologic outcomes as well.95–97

The use of ECMO is extremely resource intensive and the cost alone could prohibitits widespread adoption. The amount of data for the use of VA ECMO in patients withOHCA remains limited, and it is still unclear which patients will benefit most fromECMO therapy. But as the body of literature continues to grow, it appears that rapidinitiation of ECMO in the emergency department for OHCA is possible. It is importantfor the emergency physician to keep in mind that ECMO can be used as a temporarybridge to a more definitive procedure, such as revascularization, the use of a VAD, ortransplantation.

SUMMARY

Patients who require mechanical circulatory support are some of the most critically illpatients one can encounter in the emergency department. As the use of these tech-nologies continues to grow, emergency physicians have increasing opportunities toparticipate in the advancement of these potentially life-saving technologies. It isimperative that emergency physicians not only understand the complexities of thesepatients, but also be well-prepared to handle the many complications that can occurwith these emerging therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank and acknowledge Linda J. Kesselring, MS, ELS, for copyeditingthe article and incorporating revisions into the final article.

REFERENCES

1. HeartMate II� left ventricular assist device (LVAD) fact sheet. Available at: www.thoratec.com/downloads/heartmate-II-fact-sheet-b100-0812-final.pdf. AccessedJanuary 21, 2014.

2. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. ECLS Registry report. Internationalsummary. 2013. Available at: www.elso.org/index.php?option5com_content&;view5article&id585&Itemid5653. Accessed January 21, 2014.

3. Scheidt S, Wilner G, Mueller H, et al. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation incardiogenic shock: report of a co-operative clinical trial. N Engl J Med 1973;288:979–84.

4. Thiele H, Allam B, Chatellier G, et al. Shock in acute myocardial infarction: theCape Horn for trials? Eur Heart J 2010;31:1828–35.

5. Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the man-agement of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction–executive summary.

http://www.thoratec.com/downloads/heartmate-II-fact-sheet-b100-0812-final.pdfhttp://www.thoratec.com/downloads/heartmate-II-fact-sheet-b100-0812-final.pdfhttp://www.elso.org/index.php?option=com_content%26;view=article%26id=85%26Itemid=653http://www.elso.org/index.php?option=com_content%26;view=article%26id=85%26Itemid=653http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref1http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref1http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref1http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref2http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref2http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref3http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref3

-

Greenwood & Herr864

A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart AssociationTask Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1999 guide-lines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction). J Am CollCardiol 2004;44:671–719.

6. Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarctionin patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force onthe Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the Eu-ropean Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2909–45.

7. Zeymer U, Bauer T, Hamm C, et al. Use and impact of intra-aortic balloon pumpon mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardio-genic shock: results of the Euro Heart Survey on PCI. EuroIntervention 2011;7:437–41.

8. Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, et al. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation inacute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock (IABP-SHOCK II):final 12month results of a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 2013;382:1638–45.

9. Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, et al. Intraaortic balloon support for myocar-dial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1287–96.

10. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for themanagement of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a reportof the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart AssociationTask Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:485–510.

11. American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiog-raphy and Interventions, O’Gara PT, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for themanagement of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American Col-lege of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Prac-tice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:e78–140.

12. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acutemyocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. EurHeart J 2012;33:2569–619.

13. Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, et al. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization:the Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Car-diology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery(EACTS). Eur Heart J 2010;31:2501–55.

14. Sustiı́c A, Medved I, Simi�c O. Ultrasound-guided placement of intra-aorticballoon pump. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2002;19:149–50.

15. Kettner J, Sramko M, Holek M, et al. Utility of intra-aortic balloon pump supportfor ventricular septal rupture and acute mitral regurgitation complicating acutemyocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2013;112:1709–13.

16. Sjauw KD, Engström AE, Vis MM, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis ofintra-aortic balloon pump therapy in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: shouldwe change the guidelines? Eur Heart J 2009;30:459–68.

17. Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. Third INTERMACS Annual Report: theevolution of destination therapy in the United States. J Heart Lung Transplant2011;30:115–23.

18. Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, et al. Long-term mechanical circulatory sup-port (destination therapy): on track to compete with heart transplantation?J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:584–603.

19. Peura JL, Colvin-Adams M, Francis GS, et al. Recommendations for the use ofmechanical circulatory support: device strategies and patient selection: a scien-tific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;126:2648–67.

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref3http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref3http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref3http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref3http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref4http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref4http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref4http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref4http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref5http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref5http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref5http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref5http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref6http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref6http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref6http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref7http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref7http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref8http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref9http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref9http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref9http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref9http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref9http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref10http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref10http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref10http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref11http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref12http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref12http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref12http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref13http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref13http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref13http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref14http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref14http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref14http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref15http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref15http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref15http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref16http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref16http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref16http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref17http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref17http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref17http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref17

-

Mechanical Circulatory Support 865

20. Slaughter MS, Pagani FD, Rogers JG, et al. Clinical management of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Trans-plant 2010;29(Suppl 4):S1–39.

21. Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, et al. Advanced heart failure treated withcontinuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2241–51.

22. Geisen U, Heilmann C, Beyersdorf F, et al. Non-surgical bleeding in patientswith ventricular assist devices could be explained by acquired von Willebranddisease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;33:679–84.

23. Letsou GV, Shah N, Gregoric ID, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding from arteriove-nous malformations in patients supported by the Jarvik 2000 axial-flow left ven-tricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:105–9.

24. Klovaite J, Gustafsson F, Mortensen SA, et al. Severely impaired von Willebrandfactor-dependent platelet aggregation in patients with a continuous-flow leftventricular assist device (HeartMate II). J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:2162–7.

25. Ashbrook M, Walenga JM, Schwartz J, et al. Left ventricular assist device-induced coagulation and platelet activation and effect of the current anticoagu-lant therapy regimen. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2013;19(3):249–55.

26. Goldstein DJ, John R, Salerno C, et al. Algorithm for the diagnosis and manage-ment of suspected pump thrombus. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013;32:667–70.

27. Aaronson KD, Slaughter MS, Miller LW, et al. Use of an intrapericardial,continuous-flow, centrifugal pump in patients awaiting heart transplantation. Cir-culation 2012;125:3191–200.

28. Pagani FD, Miller LW, Russell SD, et al. Extended mechanical circulatory sup-port with a continuous-flow rotary left ventricular assist device. J Am Coll Cardiol2009;54:312–21.

29. Piccione W. Left ventricular assist device implantation: short and long-term sur-gical complications. J Heart Lung Transplant 2000;19(Suppl 8):S89–94.

30. Rose EA, Levin HR, Oz MC, et al. Artificial circulatory support with textured inte-rior surfaces. A counterintuitive approach to minimizing thromboembolism. Cir-culation 1994;90(5 Pt 2):II87–91.

31. Frazier OH, Rose EA, Macmanus Q, et al. Multicenter clinical evaluation of theHeartMate 1000 IP left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;53:1080–90.

32. Starling RC, Moazami N, Silvestry SC, et al. Unexpected abrupt increase in leftventricular assist device thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:33–40.

33. Shah P, Mehta VM, Cowger JA, et al. Diagnosis of hemolysis and device throm-bosis with lactate dehydrogenase during left ventricular assist device support.J Heart Lung Transplant 2014;33:102–4.

34. Topilsky Y, Pereira NL, Shah DK, et al. Left ventricular assist device therapy inpatients with restrictive and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail2011;4:266–75.

35. Holman WL, Park SJ, Long JW, et al. Infection in permanent circulatory support:experience from the REMATCH trial. J Heart Lung Transplant 2004;23:1359–65.

36. Holman WL, Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, et al. Infection after implantation of pulsatilemechanical circulatory support devices. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139:1632–6.e2.

37. Gordon RJ, Weinberg AD, Pagani FD, et al. Prospective, multicenter study ofventricular assist device infections. Circulation 2013;127:691–702.

38. Kalya AV, Tector AJ, Crouch JD, et al. Comparison of Novacor and HeartMatevented electric left ventricular assist devices in a single institution. J HeartLung Transplant 2005;24:1973–5.

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref18http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref18http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref18http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref19http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref19http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref20http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref20http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref20http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref21http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref21http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref21http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref22http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref22http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref22http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref23http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref23http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref23http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref24http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref24http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref25http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref25http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref25http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref26http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref26http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref26http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref27http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref27http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref28http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref28http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref28http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref29http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref29http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref29http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref30http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref30http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref31http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref31http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref31http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref32http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref32http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref32http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref33http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref33http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref34http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref34http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref34http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref35http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref35http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref36http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref36http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref36

-

Greenwood & Herr866

39. Sivaratnam K, Duggan JM. Left ventricular assist device infections: three casereports and a review of the literature. ASAIO J 2002;48:2–7.

40. Sinha P, Chen JM, Flannery M, et al. Infections during left ventricular assist de-vice support do not affect posttransplant outcomes. Circulation 2000;102:III194–9.

41. Aslam S, Hernandez M, Thornby J, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of fungalventricular-assist device infections. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:664–71.

42. Shoham S, Shaffer R, Sweet L, et al. Candidemia in patients with ventricularassist devices. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:e9–12.

43. Bagdasarian NG, Malani AN, Pagani FD, et al. Fungemia associated with leftventricular assist device support. J Card Surg 2009;24:763–5.

44. ChinnR,DembitskyW,EatonL, et al.Multicenter experience: preventionandman-agement of left ventricular assist device infections. ASAIO J 2005;51:461–70.

45. Holman WL, Skinner JL, Waites KB, et al. Infection during circulatory supportwith ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;68:711–6.

46. Argenziano M, Catanese KA, Moazami N, et al. The influence of infection on sur-vival and successful transplantation in patients with left ventricular assist de-vices. J Heart Lung Transplant 1997;16:822–31.

47. Monkowski DH, Axelrod P, Fekete T, et al. Infections associated with ventricularassist devices: epidemiology and effect on prognosis after transplantation.Transpl Infect Dis 2007;9:114–20.

48. Boyle A. Arrhythmias in patients with ventricular assist devices. Curr Opin Car-diol 2012;27:13–8.

49. Pedrotty DM, Rame JE, Margulies KB. Management of ventricular arrhythmias inpatients with ventricular assist devices. Curr Opin Cardiol 2013;28:360–8.

50. Oz MC, Rose EA, Slater J, et al. Malignant ventricular arrhythmias are well toler-ated in patients receiving long-term left ventricular assist devices. J Am CollCardiol 1994;24:1688–91.

51. Vollkron M, Voitl P, Ta J, et al. Suction events during left ventricular support andventricular arrhythmias. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007;26:819–25.

52. Hoerr HR, Kraemer MF, Williams LJ, et al. In vitro comparison of the bloodhandling by the constrained vortex and twin roller blood pumps. JECT 1987;19:316–21.

53. Bennett M, Horton S, Thuys C, et al. Pump-induced haemolysis: a comparison ofshort-term ventricular assist devices. Perfusion 2004;19:107–11.

54. Iwahashi H, Yuri K, Nosé Y. Development of the oxygenator: past, present, andfuture. J Artif Organs 2004;7:111–20.

55. Brodie D, Bacchetta M. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for ARDS inadults. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1905–14.

56. Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, et al. Efficacy and economic assessment ofconventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenationfor severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised con-trolled trial. Lancet 2009;374(9698):1351–63.

57. Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock: current concepts andimproving outcomes. Circulation 2008;117:686–97.

58. Javidfar J, Brodie D, Wang D, et al. Use of bicaval dual-lumen catheter for adultvenovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1763–8.

59. Bisdas T, Beutel G, Warnecke G, et al. Vascular complications in patients under-going femoral cannulation for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support.Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:626–31.

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref37http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref37http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref38http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref38http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref38http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref39http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref39http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref40http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref40http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref41http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref41http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref42http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref42http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref43http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref43http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref44http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref44http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref44http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref45http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref45http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref45http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref46http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref46http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref47http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref47http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref48http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref48http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref48http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref49http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref49http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref50http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref50http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref50http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref51http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref51http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref52http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref52http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref53http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref53http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref54http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref54http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref54http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref54http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref55http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref55http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref56http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref56http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref56http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref57http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref57http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref57

-

Mechanical Circulatory Support 867

60. Gander JW, Fisher JC, Reichstein AR, et al. Limb ischemia after commonfemoral artery cannulation for venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygena-tion: an unresolved problem. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:2136–40.

61. Foley PJ, Morris RJ, Woo EY, et al. Limb ischemia during femoral cannulation forcardiopulmonary support. J Vasc Surg 2010;52:850–3.

62. Chauhan S, Subin S. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, an anesthesiolo-gist’s perspective: physiology and principles. Part 1. Ann Card Anaesth 2011;14:218–29.

63. Catena E, Tasca G. Role of echocardiography in the perioperative managementof mechanical circulatory assistance. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2012;26:199–216.

64. Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, et al. 2010 Annual report of the Amer-ican Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System(NPDS): 28th annual report. Clin Toxicol 2011;49:910–41.

65. DeWitt CR, Waksman JC. Pharmacology, pathophysiology and management ofcalcium channel blocker and beta-blocker toxicity. Toxicol Rev 2004;23:223–38.

66. Lai MW, Klein-Schwartz W, Rodgers GC, et al. 2005 Annual Report of the Amer-ican Association of Poison Control Centers’ national poisoning and exposuredatabase. Clin Toxicol 2006;44:803–932.

67. Durward A, Guerguerian AM, Lefebvre M, et al. Massive diltiazem overdosetreated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med2003;4:372–6.

68. Holzer M, Sterz F, Schoerkhuber W, et al. Successful resuscitation of a verapamil-intoxicated patient with percutaneous cardiopulmonary bypass. Crit Care Med1999;27:2818–23.

69. Rooney M, Massey KL, Jamali F, et al. Acebutolol overdose treated with hemodial-ysis and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Clin Pharmacol 1996;36:760–3.

70. Shenoi AN, Gertz SJ, Mikkilineni S, et al. Refractory hypotension from massivebupropion overdose successfully treated with extracorporeal membraneoxygenation. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011;27:43–5.

71. Vivien B, Deye N, Megarbane B, et al. Extracorporeal life support in a case offatal flecainide and betaxolol poisoning allowing successful cardiac allograft.Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:409–12.

72. Goodwin DA, Lally KP, Null DM Jr. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation sup-port for cardiac dysfunction from tricyclic antidepressant overdose. Crit CareMed 1993;21:625–7.

73. Ghelani SJ, Spaeder MC, Pastor W, et al. Demographics, trends, and outcomesin pediatric acute myocarditis in the United States, 2006 to 2011. Circ Cardio-vasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:622–7.

74. Sagar S, Liu PP, Cooper LT Jr. Myocarditis. Lancet 2012;379:738–47.75. Feldman AM, McNamara D. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1388–98.76. Saji T, Matsuura H, Hasegawa K, et al. Comparison of the clinical presentation,

treatment, and outcome of fulminant and acute myocarditis in children. Circ J2012;76:1222–8.

77. Teele SA, Allan CK, Laussen PC, et al. Management and outcomes in pediatricpatients presenting with acute fulminant myocarditis. J Pediatr 2011;158:638–43.e1.

78. McNally B, Robb R, Mehta M, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest surveillance–Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES), United States, October 1,2005–December 31, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60:1–19.

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref58http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref58http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref58http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref59http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref59http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref60http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref60http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref60http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref61http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref61http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref61http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref62http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref62http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref62http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref63http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref63http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref63http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref64http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref64http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref64http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref65http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref65http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref65http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref66http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref66http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref66http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref67http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref67http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref68http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref68http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref68http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref69http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref69http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref69http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref70http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref70http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref70http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref71http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref71http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref71http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref72http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref73http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref74http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref74http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref74http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref75http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref75http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref75http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref76http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref76

-

Greenwood & Herr868

79. Kudenchuk PJ, Redshaw JD, Stubbs BA, et al. Impact of changes in resuscita-tion practice on survival and neurological outcome after out-of-hospital cardiacarrest resulting from nonshockable arrhythmias. Circulation 2012;125:1787–94.

80. Belliard G, Catez E, Charron C, et al. Efficacy of therapeutic hypothermia afterout-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation 2007;75:252–9.

81. Testori C, Sterz F, Holzer M, et al. The beneficial effect of mild therapeutic hypo-thermia depends on the time of complete circulatory standstill in patients withcardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2012;83:596–601.

82. Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, et al. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospitalcardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc QualOutcomes 2010;3:63–81.

83. Ewy GA. Cardiocerebral resuscitation: the new cardiopulmonary resuscitation.Circulation 2005;111:2134–42.

84. Kellum MJ, Kennedy KW, Barney R, et al. Cardiocerebral resuscitation improvesneurologically intact survival of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. AnnEmerg Med 2008;52:244–52.

85. YangCL,WenJ, Li YP,etal.Cardiocerebral resuscitationvscardiopulmonary resus-citation for cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:784–93.

86. Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, et al. Early revascularization and long-termsurvival in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. JAMA2006;295:2511–5.

87. Dumas F, Cariou A, Manzo-Silberman S, et al. Immediate percutaneous coronaryintervention is associated with better survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest:insights from the PROCAT (Parisian Region Out of hospital Cardiac ArresT) regis-try. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2010;3:200–7.

88. Le Guen M, Nicolas-Robin A, Carreira S, et al. Extracorporeal life supportfollowing out-of-hospital refractory cardiac arrest. Crit Care 2011;15:R29.

89. Avalli L, Maggioni E, Formica F, et al. Favourable survival of in-hospitalcompared to out-of-hospital refractory cardiac arrest patients treated with extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation: an Italian tertiary care centre experience.Resuscitation 2012;83:579–83.

90. Chen JS, Ko WJ, Yu HY, et al. Analysis of the outcome for patients experiencingmyocardial infarction and cardiopulmonary resuscitation refractory to conven-tional therapies necessitating extracorporeal life support rescue. Crit CareMed 2006;34:950–7.

91. KagawaE, Inoue I, KawagoeT, et al. Assessment of outcomesanddifferencesbe-tween in- and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients treatedwith cardiopulmonaryresuscitation using extracorporeal life support. Resuscitation 2010;81:968–73.

92. Chung SY, Sheu JJ, Lin YJ, et al. Outcome of patients with profound cardiogenicshock after cardiopulmonary resuscitation and prompt extracorporeal membraneoxygenation support: a single-center observational study. Circ J 2012;76:1385–92.

93. Shin TG, Choi JH, Jo IJ, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation inpatients with inhospital cardiac arrest: a comparison with conventional cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med 2011;39:17.

94. Bellezzo JM, Shinar Z, Davis DP, et al. Emergency physician-initiated extracor-poreal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2012;83:966–70.

95. Nagao K, Kikushima K, Watanabe K, et al. Early induction of hypothermia duringcardiac arrest improves neurological outcomes in patients with out-of-hospitalcardiac arrest who undergo emergency cardiopulmonary bypass and percuta-neous coronary intervention. Circ J 2010;74:77–85.

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref77http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref78http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref78http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref78http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref79http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref79http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref79http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref80http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref80http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref80http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref81http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref81http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref82http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref82http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref82http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref83http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref83http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref84http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref84http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref84http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref85http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref85http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref85http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref85http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref86http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref86http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref87http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref88http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref88http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref88http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref88http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref89http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref89http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref89http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref90http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref90http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref90http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref91http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref91http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref91http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref92http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref92http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref93http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref93http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref93http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref93

-

Mechanical Circulatory Support 869

96. Kagawa E, Dote K, Kato M, et al. Should we emergently revascularize occludedcoronaries for cardiac arrest? Rapid-response extracorporeal membraneoxygenation and intra-arrest percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation2012;126:1605–13.

97. Fagnoul D, Taccone FS, Belhaj A, et al. Extracorporeal life support associatedwith hypothermia and normoxemia in refractory cardiac arrest. Resuscitation2013;84:1519–24.

http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref94http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref94http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref94http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref94http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref95http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref95http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0733-8627(14)00064-9/sref95

Mechanical Circulatory SupportKey pointsIntroductionIABPVentricular assist deviceCommon VAD ComplicationsInfectious ComplicationsArrhythmiasMechanical Failure

ECMOOverviewECMO Pump Set-Up and CannulationClinical Uses for ECMOToxic overdosesMyocarditisECMO for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and ECMO-assisted CPR (eCPR)

SummaryAcknowledgmentsReferences