MAX KADE CENTER G -A STUDIES · 2013. 10. 11. · in the concentration camps. After Brecht and his...

Transcript of MAX KADE CENTER G -A STUDIES · 2013. 10. 11. · in the concentration camps. After Brecht and his...

MAX KADE CENTER

FOR GERMAN-AMERICAN

STUDIES

MARCH 2004

Newsletter of the Max Kade CenterEditor: Frank Baron; e-mail: [email protected]

Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures; The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66045Telephone: (785) 864-4803; Fax: (785 98; www.ku.edu/~maxkade

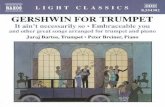

Egon Breiner: An Austrian in ExilePeter Breiner

State University of New York at Albany

gimes, he continued his politicalactivity as a member of the nowunderground Austrian Socialist

Party and was repeatedly jailed forillegal resistance activity againstthe regime. After the Anschluss, hecontinued his activity. However,one day while Breiner was on hisway home, a friend told him thatthe Gestapo had been looking forhim at his parents’ home. Not re-turning home, he acquired a forgedpassport and fled to Zürich, Swit-zerland, where he stayed with anumber Swiss socialists. He thentraveled to Paris (staying withKostya Zetkin, the son of Clara

Zetkin) and from there to Swedenwhere he joined a number of Aus-trian socialist refugees. He lived in

Stockholm and worked as amachinist from 1939 to 1941.His roommate was BrunoKreisky. In 1941, through theintervention of Joseph But-tinger and Muriel Gardiner,Eleanor Roosevelt made avail-able a number of visas for Aus-trian socialists to immigrate tothe United States. BrunoKreisky received one of thesevisas, but at the last minute forpersonal reasons, he decided tostay in Stockholm. He offeredhis visa to Egon Breiner. Fear-ing Sweden could be invaded

any day, Breiner accepted the visa.He then traveled to Moscow andfrom there took the trans-Siberianrailway to Vladivostok. From therehe sailed on the Annie Johnson, thelast boat to cross the Pacific beforethe German invasion of Russia.Like the unexpected visa to theU.S., the trip on the Annie Johnsonproved to be one of several turn-ing points in his life. On the boathe met, among others, BertoltBrecht, with whom he becamewell-acquainted. Once in Los

Egon Breiner’s life and bookcollection reflect important ele-ments of the Austrian exile expe-rience. Professor PeterBreiner, Egon Breiner’s son,who generously donated thecollection to the center, hassummarized the backgroundand context in which thesevaluable books came together.

Egon Breiner was born in1910 in the Leopoldstadt sec-tion of Vienna to a Hungarianfather and a German-speakingmother from Bohemia. Bothparents were Jewish. He wasan avid reader and became in-terested in politics at a youngage. He dropped out of school atthe age of 15 and joined the youtharm of the Austrian Socialist Party.He proved to be an extremely ableleader and in his 20s became thedistrict leader [Bezirksleiter] of theyoung socialists in Leopoldstadt.He took many courses on litera-ture at the Volkschule and enthu-siastically embraced the culturallife of Vienna. He attended musi-cal performances, the theater, andthe Vienna opera. During theDollfuss and Schuschnigg re-

Egon Breiner in the 1990s

knowledge of Austrian and Ger-man literature, and could never re-sist buying multiple editions of thesame much-loved work, whetherit was the collected plays ofNestroy, the novels of Max Frisch,or The Good Soldier Schweik ofHašek. From the 1960s to the endof his life, Austrian writers andsometimes film makers passingthrough Los Angeles would stopat his house for coffee and cake,

and he would use these visits totell stories of his experiences be-fore and shortly after he came tothe United States.

Although he was engaged inprogressive politics in the UnitedStates, his true love was his homecountry. Indeed, so strong was hisnostalgia for Austria that he waswilling to overlook some of thedarker moments of its history. Hewas especially enthusiastic aboutthe governmental success of theparty to which he had unstintinglydevoted his youth, the AustrianSocialist Party, and was full ofadmiration for both the Chancel-lor of Austria, Bruno Kreisky, andthe comprehensive Austrian wel-fare state. Much of this enthusi-asm stemmed from a fact that ishard to appreciate today, namelythat the pre-World War II AustrianSocialist Party had been for himnot just an ordinary political partyseeking state power, but almost an

ersatz family, providing him withfriends, education, and a sense ofmoral direction. Moreover, thisparty in the postwar period up anduntil the end of the twentieth cen-tury represented to him the em-bodiment of Austria as a societyof decency and solidarity. Thus hewas willing to accept, with a mini-mum of criticism, the party’s scan-dals, political compromises, andslow decay into a leadership ofparty operatives. The turn to theright in Austria distressed himimmensely. Similarly, althoughAustria had lost the enormous cul-tural influence it had exercised be-fore World War II, Breiner fol-lowed its literary output with en-thusiasm. On his many trips hecollected the latest novels alongwith a host of books in dialect. Inshort, from the 1960s to his deathin 2000, he lived in two worlds,the world of Los Angeles, with itsculture of music, theater, and poli-tics, and the world of Austria (andto a lesser extent, Germany), thehome of his cultural and politicalallegiances.

The library of Egon Breinerrepresents multiple worlds. It com-bines German and Austrian clas-sics, contemporary German andAustrian literature, and historicaland political books tracing theradical ups and downs of CentralEurope. In many ways, the libraryrepresents his life. That is, he wasa product of several cultures, allnow lost: the extraordinary cul-tural life of fin de siècle Viennaand its modernist offshoots in thelate 20s and 30s; the moral andeducational world of the AustrianSocialist Party; and the world ofGerman and Austrian emigrés inLos Angeles in the post-World WarII period. He often mourned thepassing of these cultures, and inan odd way with his death in Oc-tober of 2000, the world in whicha person without an academic de-gree could almost single-handedlyabsorb and keep alive the cultureof Central Europe seemed to havedisappeared with him.

Angeles, he came to know manyof the members of the Brecht circleincluding Helly Brecht, HansEisler, Paul Dessau, and PeterLorre, as well as other refugeewriters and artists such asAlexander Döblin and FranzWerfel. Although he worked as amachinist at Southern Pacific Rail-road by day, he spent many eve-nings in the Brecht house in SantaMonica. In 1942 he married aViennese refugee doctor,Leopoldine Reinisch. During thewar years, despite the hardships,he and Leopoldine circulatedamong the many refugees in LosAngeles. The one dark aspect ofthis period was that he had leftboth his parents and his brother be-hind in Vienna, and he did notlearn of their fate until after thewar. His brother and parents diedin the concentration camps.

After Brecht and his circle leftthe United States, Breiner, at leaston the surface, settled into the lifeof a typical member of the post-World War II generation. He hadtwo sons, Peter, born in 1947 andTom, born in 1952. He bought ahouse in the Hollywood Hills andcontinued working as a machinist.Nonetheless, he and Leopoldineconstituted a circle of Austrian andGerman refugees—this time notrenowned—who met regularly intheir house to discuss culture, poli-tics, and life in Europe. Breinerstayed in contact with his manyfriends and acquaintances in Aus-tria. Many of them had enteredpolitics in the newly constitutedneutral country. He, followed thecareer of Bruno Kreisky with par-ticular interest. In 1956, Breinervisited Austria for the first timesince he had fled. It was one ofmany visits he would make in thecourse of his life. Though he hadonce entertained the possibility ofreturning, he never did so, but hewatched the political develop-ments with great interest from thesidelines. He also pursued one ofthe great passions of his life, bookcollecting. He had an enormous

Egon Breiner in the 1930s

John Spalek and the Record of the Exile Experienceof exile studies. For orientation on any exile topic, itis necessary to consult his Guide to the ArchivalMaterials and the multivolume DeutscheExilliteratur seit 1933. His interest in Ernst Tollerand Lion Feuchtwanger has resulted in important bib-liographic publications.

The Max Kade Center has been the beneficiaryof Spalek’s talent for book collecting. The exile col-

lection reflects hisbroad knowledgeof a field that ex-tends into everyconceivable disci-pline. The most re-cent transfer ofbooks from his li-brary was theFranz Werfel col-lection, probablythe most compre-

hensive collection of its kind. To draw attention tothe special features of this recent acquisition, theExile Society Conference of September 4–7, 2003,devoted five lectures to Franz Werfel.

Lawrence Artist’s Work on Display at the Max Kade Center

Nancy came to the United States to continue her stud-ies. She majored in mathematics and later turned toart. She earned a master of fine arts degree with anemphasis in jewelry design and metal working.

Bjorge’s childhood fascination provides the ba-sis and inspiration of her art. She discoverd that aunique form of art could evolve from the simplicityof blank paper. Her paper sculptures are not basedon the origami; the inspiration for her art comes fromfurther back in the past, in the ancient use of paperin Asia. Bjorge has taken this art form and createdher own, unmistakably individualistic style. She de-veloped this style by looking into the past and re-shaping a combination of Chinese and Western art.

Professors Keel and Baron will be part of a del-egation that will be present at the opening of the ex-hibition at the Eutin County Library.

To commemorate thefifteenth anniversary of theLawrence-Eutin sister cityexchanges, Nancy Bjorgehas been invited to exhibither art work in Eutin. Theexhibition will open onJune 2, during the visit of atwenty-member Lawrencedelegation.

Bjorge was born inShanghai and raised inHong Kong. One of the ac-tivities that influenced herart was the ceremony of

paying respect to the family’s ancestors. The chil-dren had to fold paper. After completing high school,

Books Published by John Spalek

Nancy Bjorge

Historian H. Stuart Hughes asserts that the “mi-gration to the United States of European intellectu-als fleeing fascist tyranny . . . the most importantcultural event—or series of events—of the secondquarter of the twentieth century. . . . Emigration inthe 1930s went beyond any previous cultural expe-rience: in its range of talent and achievement; it wasindeed something new in the modern history of West-ern man.” JohnSpalek has been in-defatigable in hisefforts to recoverand preserve thelegacy of this ex-traordinary histori-cal phenomenon.His achievementswere recognized re-cently in a lengthyarticle of Aufbau(October 30, 2003). He also received special honorsfrom the Toller Society.

Spalek’s publications represent a network of in-formation crucial for scholarly research in the field

This year the conference of graduate students ofGerman at the University of Kansas addressed thetopic “Today’s Image of the German-SpeakingWorld.” The two-day eventtook place at the Max KadeCenter on February 20–21.Professor Ludwig M.Eichinger, Institut fürDeutsche Sprache, Man-heim, and Max Kade Visit-ing Professor, delivered thekeynote address, “Dialekteund regionale Substandards:Zum sprachlichen Alltag inder Bundsrepublik Deutsch-land.” The KU graduate stu-dents who contributed were:Thorsten Huth, “‘Germans Must Be Quite Arrogant,Then?!’—The Cultural Lens in the (German) Lan-guage”; Scott Seeger, “On Being and SpeakingFrisian: Perception and Identity in theWiedingharde”; Michael T. Putnam, “The Connec-tion between Dynamic Antisymmetry and Prosodic

The Eighth Annual Graduate Students’ Conferencein German Studies

Scott Seeger

Kansas Association of Teachers of GermanSchülerkongress 2004

Some 300 high school students of German fromtwenty-three high schools in Kansas descended uponLawrence for the “2004 Schülerkongress” sponsoredby the Kansas Association of Teachers of German incooperation with the Department of Germanic Lan-guages and Literatures at the University of Kansason Saturday, February 28, 2004. Over thirty KU fac-ulty and graduate students in German together withguest professors from Germany and Hungary judgedcontests in poetry and prose. Contest categories in-cluded poetry and prose recitations, oral proficiencyinterviews, spelling bees, and a cultural informationtest. Prize winners received a total of 150 medalsduring an awards assembly in the afternoon. Eachparticipating school was recognized with a framedcertificate. During the awards assembly, exchange

students from Germany and Switzerland congratu-lated the American students on their enthusiasm andtheir willingness to give up a Saturday for the sake ofGerman language and culture competitions.

Stress Assignment in XP-Scrambling”; Melody Har-ries, “Germany’s Role in the Expanding EuropeanUnion”; Nora Bruegmann, “Persönlichkeitsent-

wicklung in Thomas BrussigsAm kürzeren Ende derSonnenallee”; and ViktóriaBagi, “Zum Vaterbild heran-wachsender Jungen amAnfang und Ende des 20.Jahrhunderts.” Former KUstudent Monika Moyrer, whois presently pursuing Ph.D.studies at the University ofMinnesota, returned toLawrence to deliver a talk on“‘Parkhauskatzen schleppenfünf sechs Pfoten’: Space,

Language, and Diasporic Aesthetics in Herta Müller’sCollege Poetry.” Professor Eichinger, who took ac-tive part in all the discussions, commented that thegraduate students had succeeded in creating a profes-sional forum for the public presentation of theirresearch.

Hungarian Course Being Offered

An Internet-supported course on “SurvivalHungarian“ will be offered for the first time thissummer at the Edwards campus in Overland Park.Mónika Pacziga, graduate student from theUniversity of Budapest and Hungarian instructor atKU for the past two years, has worked closely withMatt Garrett at the Academic Computer Center andJonathan Perkins at the Ermal Garinger AcademicResource Center to develop the course. The newmaterial and course structure will enable students tomake rapid progress in acquiring the skills tocommunicate effectively in Hungarian.

The focus is on language skills, vocabulary, andexpressions in everyday situations. The units bypasscomplex grammar explanations. Words, phrases, and idiomatic expressions are introduced immediately incombination with pronunciation. Students can simply click on any text and hear a native speaker articulatecorrect sounds. Practice exercises also reinforce words or phrases with immediate sound. The Internetmaterials provide user-friendly support for steady progress.

The development of this course has been made possible with the generous support the European StudiesProgram, the KU Graduate School, and the Center for International Business.

The KU Edwards campus will offer HNGR 453, Survival Hungarian,in the summer session, Tuesdays and Thursdays from 7 to 10 p.m. Specialarrangements can be made for students from the Lawrence campus. Forenrollment information, contact Dan Mueller at [email protected]. Forcourse information consult the instructor, Andrea Némedi([email protected]).

Némedi received M.A. degrees in Comparative Literature (2001),English (2002), and German (2003) from the University of Szeged. Since2001, Némedi has been enrolled in the Comparative LiteratureDepartment’s Ph.D. program of the University of Szeged, where she hasbeen working in the field of literary theory. With the support of DAADscholarships, she studied in Germany twice. In the fall of 1998, she attendedthe Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, and during the academic year2002–2003 she studied at the University of Cologne. She enrolled in theprogram of the German Department at KU in the fall of 2003 to work

toward a Ph.D. degree in German literature. Her research interest is digital literature, including hyperfiction,multimedia, and Internet literature. She is especially interested in how the computer influences the wayliterary texts are written and read. She has taught German courses at several different levels.

See www.ku.edu/ces/ns/index

Mónika Pacziga

Andrea Némedi

The orthographic norm for Modern German has beenthe subject of some controversy since the adoptionof “spelling reforms” in 1998. As Director of theInstitut für Deutsche Sprache in Mannheim, MaxKade Professor Ludwig Eichinger finds himself inthe center of the storm. Here he discusses two of thereforms, the rules governing the spelling of com-pound verbs and the spelling of the voiceless “s”after long and short vowels. The changes becomepermanent in 2005.

Man kennt Konrad Duden in Deutschland. Mitseinem Namen verbindet man die Regeln für diedeutsche Rechtschreibung, die seit dem Beginn deszwanzigsten Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebietgalten. Seither waren die Vorschriften immerdetaillierter und umfangreicher geworden, so kamauch immer einmal wieder die Idee auf, denRegelapparat grundlegend zu reformieren. In den1970er Jahren verstärkte sich der Eindruck, dass esZeit wäre, die leitenden Prinzipien der deutschenSchreibung klarer herauszustellen, an besondersschwierigen Stellen eindeutigere Entscheidung-shilfen zu geben und so das Schreiben zu erleichtern.Als Folge davon wurde von den Bildungspolitikernder deutschsprachigen Länder eine Kommissioneingesetzt, die diese Fragen klären sollte. Sie fandihren Platz am Institut für Deutsche Sprache und sieerarbeitete eine neue Regelung, die 1998 in denöffentlichen Institutionen eingeführt wurde, und ab2005 endgültig in Kraft tritt.

An zwei Beispielen soll gezeigt werden, vonwelcher Art die Dinge sind, die neu geregelt wurden.Zum einen ist es im Deutschen in bestimmten Fällen

nicht leicht zu sagen, wann zweianscheinend selbständige Wörter zueinem zusammen geschriebenwerden und wann nicht. Mit derEntscheidung zwischen diesenMöglichkeiten waren in der altenRechtschreibung inhaltliche Unter-schiede verbunden. Die Neuregelunglegt dagegen starken Wert auf formalnachvollziehbare Entscheidungen.Das soll das Lernen der Recht-schreibung erleichtern. Letztlichführen die neuen Regelungen dazu,dass man mehr getrennt schreibt. Umdas zu erreichen, wurden Unter-schiede in der Schreibung auf-

gegeben, die entsprechende Information muss nun demKontext entnommen werden. So schreibt man jetztkennen lernen (‘get to know’) wie schreiben lernen(‘learn to write’) getrennt, weil es sich jeweils um zweiInfinitive handelt, obwohl man im ersten Fall nichtetwas lernt (‘learn to know’). Diese Neuerungenwerden heftig diskutiert, man wird, um die Reformvernünftig fortzuschreiben, beobachten müssen, wiedie Schreiber längerfristig mit solchen Fällen umgehenwerden.

Der zweite Fall ist weitaus weniger umstritten, erbetrifft die Verwendung der Buchstaben <ss> und <ß>.In der neuen Schreibung steht das Zeichen <ß> nurnoch für einen geschärften S-Laut nach langen Vokalen(Fuß, aber nass), früher zudem am Wort- oderSilbenende, unabhängig von der Art des Vokals bzw.der Silbe. Bei zweisilbigen Wörtern sieht man denGrund für diese Veränderung genauer, hier gehört das<ß> zur folgenden Silbe (Fü-ße), bei der Schreibung<ss> gehört zu jeder Silbe ein <s> (Näs-se). Da solcheFormen in allen Texten recht häufig sind—so ist jaunter anderem die Konjunktion dass (‘that’) betroffen,die man früher mit <ß> schrieb—erkennt man an ihrTexte, die in neuer Rechtschreibung geschrieben sind,am klarsten. Alle anderen Dinge sind weitaus seltener.

Warum kennt man Konrad Duden noch immer?—Weil die Rechtschreibung ein sichtbarer Teil derSprachkultur ist, in den man nicht ohne Mühehineingewachsen ist. Veränderungen werden daherauch kritisch betrachtet. Aber auch die Schreibungkennt eine Entwicklung und die Rechtschreibreformist nicht ihr Ende, sondern eher etwas wie ein amtlicherWegweiser in diesem Prozess.

Ludwig Eichinger with Graduate Students at the Max Kade Center

Die Orthographiereform—keine leichte Aufgabe

Ludwig M. Eichinger

German Language Varieties Worldwide:Internal and External Perspectives

Edited byWilliam D. Keel and Klaus J. Mattheier

of Mannheim and Max Kade Professor at KU in2004) considered the near impossibility of develop-ing an adequate methodology for sociolinguistic re-search in such complex speech communities. Thelinguist using the traditional method of direct inter-view was faced with the dilemma of having to ob-serve and record without partaking in the life of thecommunity. And, even the researcher who devotedthe time to, in effect, become part of the communityremained limited by the roles taken by each indi-vidual in the community. A central concern is thedifferentiation between transfer processes in lan-guage contact situations and the phenomenon of lan-guage attrition, simplification or decay in the lastphases. The phenomenon of language decay in lin-guistic isolation includes a number of consequences,such as the breakdown of grammatical categories (forexample, the loss of case distinctions in the nounphrase, the loss of tense or aspectual distinctions inthe verb). The focus of the sixteen essays is the in-vestigation of the sociolinguistic phenomena of Ger-man linguistic enclaves. The multifaceted develop-ments converge in the final analysis in the juxtapo-sition of language maintenance and language loss.

William D. Keel and Klaus J. Mattheier (eds.),German Language Varieties Worldwide: Internal andExternal Perspectives (2003) resulted from a con-ference held in 2001, at the Max Kade Center. Atthat conference, researchers of German settlementdialect varieties found in the United States, Brazil,Mexico, Hungary, Romania, and the former SovietUnion discussed and debated current issues. One ofthe central issues discussed was speech island death.Despite the prospect of the ultimate demise of thelarge array of German linguistic enclaves around theworld, Mattheier (University of Heidelberg and MaxKade Professor at KU in 2000) argued that this situ-ation presented an opportunity for linguists andsociolinguists to gain significant insights for thetheory of linguistic change. He also placed speechisland research within the larger context of interna-tional minority studies. For Mattheier, the point inthe life of a speech island at which stability turns toinstability is the key to understanding the life cycleof such linguistic enclaves. One of the longest sur-viving German dialect communities in the NewWorld is that of the Pennsylvania Germans. LudwigEichinger (Institute für Deutsche Sprache/University

The Humboldt Digital Library

This digital library of the works of Alexandervon Humboldt entails a comprehensive re-creationof the explorer’s five-year journey to the Americas(1799–1804). In its final form, the library networkwill show the twenty-nine volumes that Humboldtpublished, along with direct links to relevant infor-mation from current databases. In the books,Humboldt records his observations of Venezuela, Co-lombia, Ecuador, Peru, Mexico, and Cuba. Disci-plines covered include botany, zoology, geology, an-thropology, archeology, and history. Although theproject team has its sights on a library in four lan-guages (French, German, Spanish, and English), at

the present stage, work is limited to English transla-tions. With the aid of a Transcoop grant, scholars fromthe University of Kansas, (the Max Kade Center, theMuseum of Natural History, and the Department ofAnthropology), the Berlin Humboldt Research Cen-ter, the Eutin State Library, and the Technical Uni-versity of Offenburg have formulated the content andstructure of the digital library. Contributors to theproject plan to create a user-friendly environment andnetwork that can tap information from rare books,many of which have been accessible only to a fewreaders. Although the digital library can showHumboldt’s pivotal role for various disciplines

Authority, Culture, and Communication:The Sociology of Ernest Manheim

Edited byFrank Baron, David N. Smith, and Charles Reitz

Like other exiles of his gen-eration—Max Horkheimer,Theodor Adorno, ThomasMann, Bertolt Brecht, ErikErikson, Herbert Marcuse, andErich Fromm—Ernest Man-heim contributed subtly, yet sig-nificantly, to the deprovinciali-zation of culture in his adoptedhome. Born in Budapest, hebegan his graduate studies inVienna, Kiel, and Leipzig be-fore the Hitler regime forcedhim to flee. He settled first inLondon and later in Chicagoand Kansas City. His writingand teaching assisted a genera-tion of younger scholars to be-come keenly conscious of theconflicts and contradictions atthe heart of American political, moral, and academicculture. The essays in this collection, both by andabout Ernest Manheim, attest to the depth and detailof his social theory on subjects of continuing andgrowing relevance: the sociology of communicationand public opinion, the sociology of authority, thesociology of anomie and alienation, and the sociol-ogy of social science and education. In quiet contrastto the logical positivism that had attained a near-mo-nopoly in U.S. graduate schools of philosophy andsociology, Manheim, along with a few others, offereda critical distillate of European approaches, which

Ernest Manheim

brought the insights of phenom-enology, existentialism, Marx-ism, and critical theory from themargins to the heart of intellec-tual life in this country.Manheim’s work communicatedthe vibrancy of both its classicaland contemporary German intel-lectual sources, and, in a human-istic and enlightened manner,stressed the essential connectionof education to the attainment ofthe social potential of the humanrace. Manheim developed atransformative social logic of thepublic sphere thirty years beforeJürgen Habermas did. In theearly 1950s, while other aca-demics feared jeopardizing theircareers for the relatively un-

popular cause of racial equality, Manheim demon-strated rare courage and high integrity in agreeing totestify as an expert witness in the major civil rightslawsuit of the century, Brown vs. the Board of Edu-cation of Topeka, Kansas. Likewise, his multiculturalcosmopolitanism, his opposition to any kind ofmonoculturalism, and his critique of the patriarchalfamily remain at the cutting edge of social and cul-tural theory today.

This book of essays by and about Manheim willappear in Munich with Synchron Publishers in March2004.

(Humboldt) influenced such scientists as Darwin,Wallace, and Agassiz, as well as the naturalist Muirand the landscape artist Church), it will also revealthe relevance of his observations for the modernworld.

As a vivid example of Humboldt’s extraordinarypersonality and achievements, we can point to theimages of his Washington visit, which occurred 200

years ago, upon the conclusion of his American trav-els. A Web site designed to become linked later tothe digital library reveals historical connections tothe expedition of Lewis and Clark. See www.ku.edu/~maxkade/humboldt/main.htm. It has been linked toseveral sites, including that of the Smithsonian In-stitution in Washington.

Recent Events at the Max Kade CenterGriseldisnovelle im Deutschland des 15.Jahrhunderts,” Anne Allen-Winston (Carbondale),“Fifteenth-Century Women as Simultaneous Tran-scribers and Editors of Sermons,” Charles Nauert(Columbia), “Jakob Wimpheling as a Pioneer ofChristian Humanism,” Michael Keefer (Guelph,

Canada), “Damnation byDisplacement: Contribu-tions to the Legend ofFaustus by Luther,Melanchthon, and Johan-nes Wier,” Ernst Dick(Lawrence, KS), “Löw-hardus, Son of Siegfried:The Invention of a Hero ina Rediscovered 17th-Cen-tury Chapbook,” andMarianneli Sorvakko-Spratte (Kirchheimbolan-den, Germany), “The FaustLegend and Its Transfor-mations in Finland.”

October 25, 2003. Aprogram of violin music,performed by AleksandrSnytkin, Noemi Milorado-

vic, Francesca Manheim, Kathy Haid-Berry, andJeannine Elasewich, featured compositions by BélaBartók and Ernest Manheim.

March 6, 2004. With the imminent expansionof the European Union, interest has increased incountries linked to the former Austro-HungarianEmpire. A prominent new member of the EuropeanUnion will be Hungary. Visiting Fulbright ProfessorGyörgy Szönyi (University of Szeged) is teaching acourse this semester in order to provide the histori-cal background for new developments. In a culturalvariation of this political theme, Professor Szönyidelivered a public lecture: “Under the Influence:Hungarian Gypsy Music and the Classical Tradition.”Tracing developments in Hungary from the medi-eval period into the twentieth century, he gave re-corded samples of a nation’s cultural heritage, andhe showed that this legacy made a dramatic imprinton classical music throughout Europe.

György Szönyi

September 4–7, 2003. Conference, The Alchemyof Exile: Creative Responses to Expulsion from Nazi-Dominated Europe, jointly sponsored by the NorthAmerican Society for Exile Studies and the Max KadeCenter. Participants from the United States, Germany,Austria, Hungary, and Turkey took part. Included inthe program was a concert ofmusic by Kurt Weill, PaulHindemith, and MichaelCohen. Joyce Castle, mezzosoprano; Elaine Brewer, harp;Edward Laut, cello, and JohnBoulton, flute, performedCohen’s “I Remember,”based on the Diary of AnneFrank. Professor HelgaSchreckenberger (Universityof Vermont), former KUgraduate student and presi-dent of the North AmericanSociety for Exile Studies re-ported in her newsletter thatthe conference was a “greatsuccess.” She added: “Theexcellent concert, in particu-lar, was a wonderful andmoving experience.” JörgThunecke’s detailed description about each of thetwenty-six presentations is in the journal of theGesellschaft für Exilforschung, published in Decem-ber 2003.

September 19–20, 2003. Conference: The MaxKade Center participated in this year’s Central Renais-sance Conference by sponsoring four sessions. FormerKU graduate students Anne Winston-Allen and PaulGebhardt were on the program, which focused on theperiod 1400–1700. The program consisted of: Will-iam Hopkins (Rochester), “Johannes Tauler as a Pre-decessor?” Hartmut Rudolph (Potsdam), “The ApostlePeter as a Key to the Lay Theology of Paracelsus,”Joseph B. Dallett (Ithaca, NY), “Deviant Constructs:Inherent Images in the Labyrinthus MedicorumErrantium and Wider Traditions,” Andrew Weeks(Normal), “Image and Image Magic in the Works ofParacelsus,” Frank Baron (Lawrence), “The Mysteryand Magic of Renaissance Names: The Case ofParacelsus,” Paul Gebhardt (Mount Vernon), “Die

In Memoriam Michael Scherer

Bill Keel

We were saddened to learn of the death of Dr. Michael “Mike” Scherer in Munich, Germany, on Febru-ary 3 at the age of 81. With Toni Burzle, Dr. Scherer had been instrumental in establishing the first KUSummer Language Institute in Germany near Holzkirchen, when he held an appointment as visiting assis-tant professor in German at KU (1960–1961). He returned to KU for two years as visiting associate profes-sor in German (1962–1964) and directed the 1964 Summer Language Institute in Holzkirchen before re-turning to his duties in the Bavarian educational system. He eventually became a higher official in theBavarian Ministry for Education in Munich. He and his wife, Elisabeth, taught many years in the SLI inHolzkirchen, especially during the decade of the 1980s, when both were semiretired. They organized manytrips to museums, concerts, theater and opera performances in Munich for KU students. Michael Schererexpressed it best in his letter of resignation to Deans Waggoner and Heller in the spring of 1964: “In mynew position in Germany, it will be my avowed aim to continue to work for close understanding betweenmy home country and the United States of America. Above all, I will always be available for any service Ican render in connection with future programs of the University of Kansas to be carried through in Ger-many.” He kept that promise, and hundreds of our students benefited from his lifelong dedication to oursummer institutes. He loved to meet with students and faculty from our SLI in Holzkirchen in a Munichbeer garden and discuss politics or current cultural trends in Germany and the U.S.—he was still doing thatlast summer in his ninth decade. He is survived by his wife in Munich and his daughter in New York.

The University of KansasMax Kade Center for German-American StudiesSudler HouseDepartment of Germanic Languages and LiteraturesLawrence, KS 66045-2127

Nonprofit OrganizationU.S. Postage

PAIDLawrence, KSPermit No. 65