Mao Tse Tung

-

Upload

marianne-allam -

Category

Documents

-

view

232 -

download

6

Transcript of Mao Tse Tung

MAO TSE-TUNG BIOGRAPHYMao Tse-tung was born December 26, 1893, in Shao-shan, Hunan province.

Mao Tse-tung attended primary school,where he studied traditional Confucian classics. His mother was devoutly Buddhist. Mao Tse-tung served briefly in the republican army. Mao then spent six months studying in the provincial library.

Mao graduated from Hunan First Normal School. He went to Peking, and worked as a library assistant at Peking University. At University, Mao Tse-tung made contact with intellectual radicals who later were high in the Chinese Communist party. In 1919, Mao Tse-tung returned to Hunan. Here, Mao Tse-tung engaged in political activity. He organized groups, and published a political review.

In 1920, Mao Tse-tung married Yang K'ai-hui. Yang K'ai-hui was later executed by the Chinese Nationalists in 1930. Mao later married Ho Tzu-chen, but divorced her in 1937. Then, married married Chiang Ch'ing.

Mao Tse-tung was a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party. A Chinese soviet was founded in Juichin, Kiangsi province, with Mao as chairman. But a series of extermination campaigns by Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist government forced the CCP to abandon Juichin in 1934. This was the start of the Long March. Mao Tse-tung was able to gain control of the Chinese Communist Party, puttin an end to Russian direction. The Communist forces reached Shensi, October 1935, after a march of 10,000 km.

The Japanese invasion during W.W.11, forced the CCP and the Kuomintang to form a united front. Mao Tse-tung rose in stature as a national leader. Under Mao Tse-tung, the Chinese Communist Party membership rose from 40,000 members in 1937 to 1,200,000 members in 1945. After the end of W.W.11, the united front split and civil war erupted. The Chinese Communist Party came to power and Chiang's government was forced to flee to Taiwan.

When the United States rebuffed Mao Tse-tung, China developed a close alliance with the USSR. During the early 1950s, Mao Tse-tung served as chairman of the Communist party, chief of state, and chairman of the military commission.

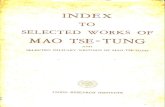

During the Cultural Revolution Mao's sayings, printed in a little red book, and buttons bearing his image were distributed. Mao Tse-tung died in Peking on September 9, 1976.

Writings and calligraphy

Mao's calligraphy: A bronze plaque of a poem by Li Bai. (Chinese: 白帝城毛泽东手书李白诗铜匾

Mao was a prolific writer of political and philosophical literature.[114] He

is the attributed author of Quotations From Chairman Mao Tse-Tung,

known in the West as the "Little Red Book" and in Cultural Revolution China as the "Red Treasure Book" (红宝书): this is a collection of

short extracts from his speeches and articles, edited by Lin Biao and

ordered topically. Mao wrote several other philosophical treatises,

both before and after he assumed power. These include:

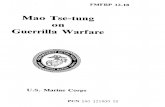

On Guerrilla Warfare (《游击战》); 1937

On Practice (《实践论》); 1937

On Contradiction (《矛盾论》); 1937

On Protracted War (《论持久战》); 1938

In Memory of Norman Bethune (《纪念白求恩》); 1939

On New Democracy (《新民主主义论》); 1940

Talks at the Yan'an Forum on Literature and Art (《在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话》); 1942

Serve the People (《为人民服务》); 1944

The Foolish Old Man Who Removed the Mountains (《愚公移山》); 1945

On the Correct Handling of the Contradictions Among the People (《正确处理人民内部矛盾问题》); 1957

Mao was also a skilled Chinese calligrapher with a highly personal

style. In China, Mao was considered a master calligrapher during his

lifetime.[115] His calligraphy can be seen today throughout mainland

China.[116] His work gave rise to a new form of Chinese calligraphy

called "Mao-style" or Maoti, which has gained increasing popularity

since his death. There currently exist various competitions specializing

in Mao-style calligraphy.[117]

[edit]Literary worksMain article: Poetry of Mao Zedong

Mao's calligraphy of his poem "Qingyuanchun Changsha"

Politics aside, Mao is considered one of modern China's most

influential literary figures, and was a prolific poet, mainly in the

classical ci and shiforms. His poems are all in the traditional Chinese

verse style.

As did most Chinese intellectuals of his generation, Mao received a

rigorous education in Chinese classical literature. His style was deeply

influenced by the great Tang Dynasty poets Li Bai and Li He. He is

considered to be a romantic poet, in contrast to the realist poets

represented by Du Fu.

Many of Mao's poems are still popular in China and a few are taught

as a mandatory part of the elementary school curriculum. Some of his

most well-known poems are: Changsha (1925), The Double

Ninth (1929.10), Loushan Pass (1935), The Long

March (1935), Snow (1936), The PLA Captures Nanjing (1949), Reply

to Li Shuyi (1957.05.11), and Ode to the Plum Blossom (1961.12).

Personal life

There are few academic sources discussing Mao's private life, which

was very secretive at the time of his rule. However, after Mao's death,

his personal physician Li Zhisui published a memoir of unique insight

into Mao's private life: The Private Life of Chairman Mao, which claims

that Mao chain smoked cigarettes, never bathed or brushed his teeth,

rarely got out of bed, was addicted to sleeping pills and had a large

number of sexual partners from whom he contracted venereal

disease.[113]

Having grown up in Hunan, Mao spoke Mandarin with a heavy Xiang

Chinese accent that is very pronounced on recordings of his

speeches.[citation needed]

Mao Zedong (1893-1976)

Chinese political leader, poet and statesman, founder of People's Republic of China. Mao Zedong's ideas varied between flexible pragmatism and utopian visions, exemplified in the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. His literary production contains mainly speeches, essays and poems. Mao published some 40 poems written in classical tradition with political message. Worshiped by millions, Mao is also considered one of the 20th century most brutal dictators. It has been estimated that he was

responsile for well over 70 million deaths.

At bluegreen twilight I see the rough pines serene under the rioting clouds. The cave of the gods was born in heaven, a vast wind-ray beauty on the dangerous peak. (1961, Written on a Photograph of the Cave of the Gods)

As a poet Mao continued the tradition, in which educated people composed poetry simply as an accomplishment. His texts showed talent, and he did not use the most banal idioms familiar from the works of Communist writers of his own generation. However, it is possible that Mao did not write all the poems credited to him. Much the same could be said of many of his political publications. In his early verse, Mao showed the influence of Tang (618-907) and Sung (960-1127) poets. On his walk across the Middle Kingdom, he recorded its modern history and used the mystical past to to illuminate the present. Several of his poems depicted the first battles of the peasant army and national events. After 1949 the the content became more meditative. Mao's best-known poem is the 'Snow', written in 1936, but published after he went in 1945 on a plane trip to Chongging. "North country scene: / A hundred leagues locked in ice, / A thousand leagues of whirling snow. / Both side of the Great Wall / One single white immensity."

Mao was born in the village of Shaoshan in the Hunan Province of China. At the age of six he began to work on his parents' farm. His father, Mao Jen-sheng, was a peasant farmer, who beat his sons regularly. Mao's mother, Wen Chi-mei, was a devout Buddhist. After graduating from a teacher's training in Changsha, Mao continued his studies at the University of Beijing, where he worked as an assistant at the library. During this period he discovered Marx, but also began to hate books and all things highly cultivated. Under the influence of Li Dazhao and Chen Duxiu, China's first major Marxist figures, Mao turned to Marxism. In 1921 Mao became a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party. During Bertrand Russell's visit to Hunan, he argued for the legitimacy of seizing power by force against Russell's reformist views. In the 1920s he concentrated on political work in his native Province and Jianxi Province. His highly pragmatic strategy was one of the main influences on Fidel Castro, when in 1959 he was able to take over Cuba with Che Guevara.

"The people are like water and the army is like fish," Mao wrote in Aspects of China's Anti-Japanese Struggle (1948). He recognized the revolutionary potential of the peasantry. Marx and Lenin had seen in their urban doctrine the working class as the leading revolutionary force. However, when first articulated, Mao's views were rejected by the Party in favor of orthodox policy. Mao himself was also an exception to the rule: he was one of only three peasants to gain control of his country throughout its long history - the

others were the founders of the Han and Ming dynasties.

Mountain. Peaks pierce the green sky, unblunted. The sky would fall but for the columns of mountains. (1934-35)

Under Comitern policy of cooperating with the Nationalists, Mao held important posts with the Guomingdang. Following the Guomindang massacre of Communist in 1927, Mao established a base in Jiangxi Province. There he directed his first major purge against dissidents.

Mao's fourth wife Chiang Ch'ing (1914-1991) was an actor. She gained first fame in Shanghai among others in Ibsen's play A Doll's House. In 1933 she joined the Communist Party, meeting Mao in Yenan and marrying him. Mao was more than twenty years older than she and had eight children. During Cultural Revolution she became an enormous force, but after Mao's death she was imprisoned with her three radical associates Wang Hongwen, Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan. The group was called the Gang of Four. It is told, that on the day of their arrest every wine shop in Beijing was sold out of alcohol. Chiang Ch'ing committed suicide in 1991.

After the break with the Nationalist Party, Mao started the guerrilla tactics, stating later that "political power grows out of the barrel of a gun." In 1934 the Nationalist government destroyed the Jiangxi Soviet, and the Communist forces started the legendary retreat and the Long March, an anabasis of 6,000 miles which has been compared to the march of Alexander the Great. In 1935 Mao's political power increased when he was elected Chairman of the Politburo. Mao's rural based guerrilla warfare led to the fall of the government. To fund the Red Army, Mao grew opium.

During World War II Mao did not fight the Japanese, but planned to divide China with Japan. The new People's Republic of China was proclaimed in 1949. The Communists were headed by Mao, who gained the upper hand over his Russian-backed adversaries. In 1949 Mao met Stalin, but after Nikita Khrushchev in his famous speech denounced Stalinism in 1956, China broke with Moscow. Stalin held Mao's son Anying hostage for for years. The "thaw" period in the Soviet Union (1955-64) was noted also in China and in 1956 Mao launched the slogan "let a hundred flowers bloom".

Mao's prestige was reinforced by his "Thought." He labelled the ideas of his opponents as "mechanical" or "dogmatic." "Be resourceful, look at all sides of a problem, test ideas by experiment, and work hard for the common good," Mao said. The basis of his ideology was Marxism-Leninism, but he adapted it to Chinese conditions, and partly he followed such CCP's

theoreticians as Chen Boda and Ai Siqi. The support of the Communists among intellectuals also was rising. Zhang Dongsun, who was the most perceptive philosopher of the modern China, saw that Communists were China's only practical way out.

In his 'Talks at the Yan'an Forum on Literature and Art' (1942, Tsai Yenan wen-i tso-t'an hui shang it chiang-hua) Mao issued a set of perspective guidelines for literature, in which he emphasized the status folk tradition and oral and performing literature. The novel of land reform were followed by novels on agricultural collectivization, the central theme of art at that time. Novelists also praised the Party, the revolution, and the people. Some writers dealt with the heroism of soldiers during the Korean war. In 1958 Mao started the "Great Leap Forward", industrial and agricultural program, which did not have the success he expected. He urged to construct backyard steel furnaces to gain the Western steel production. This unrealistic project was not without a certain good will, although results were tragic: about 30 million people died in the famine (in some sources 45 million people were worked, starved or beaten to death), when ill-trained peasants were forced to carry out the gigantic industrialization plan. Mao was aware of the consequences of the policy, saying that "it is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill."

Following the disaster of the "Great Leap Forward", a new series of novels on communization appeared by authors with peasant backgrounds, among them Liu Quing and Hao Ran. The reading public was more drawn to a wave of historical novels celebrating the history of the communist revolution. Most notable were Luo Guangbin's and Yang Yiyan's works. Nevertheless, none of the new novels of socialist realism proved sufficiently politically correct to survive the censorship during the power struggle of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

By 1965 Mao feared that he was losing control. He appealed to the populace against the Party apparatus and consolidated again his power by the Cultural Revolution. Red Guards were formed in 1966 and sent into the countryside to force bureaucrats, professors, technicians, intellectuals, and other nonpeasants into rural work. In the vengeful outburst of hatred and ignorance, tens of thousands were murdered or forced to give up their jobs, and China's economy suffered. "A revolution is not the same as inviting people to dinner, or writing as essay, or painting a picture... A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another." Mao had said (in Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, 1965) The publishing of new books and the introduction of new ideas virtually stopped. Except for the works of the deceased Lu Xun, all modern works were banned. From 1966 for the following six years publication of art journals was suspended. Art schools were closed and artists disbanded. Large numbers of old temples

and monuments were smashed or vandalized. In the end, the disorder was so bad that the army was called in to repress the Red Guards and other fractions. After the chaos, Mao decided open doors to the West. China's Relationship with the United States were strained, but in 1972 President Richard Nixon journeyed to China, and broke the ice. All practical negotiations were handled by Zhou Enlai and Henry Kissinger; at the meeting with Nixon, Mao kept the discussion on a fairly abstract level.

According to Mao's personal physician Zhisui Li (in The Private Life of Chairman Mao), the leader of China used heavily barbiturates although otherwise he was in excellent health. Later in life Mao developed paranoia; Li Zhisui mentions also Mao's aversion to bathing. His personal life became secretive and in many ways morally corrupt. Lin Biao, who was designated by Mao as his successor, died under mysterious circumstances in 1969. After Lin's fall, the prime minister Zhou Enlai was a moderator between the opposing camps of Liu Shaoqi and Mao. Zhou died in 1975, and the leadership of the moderates was taken over by Deng Xiaoping. Mao's death in 1976 broke his wife's hold on power. Mao had smoked cigarettes his whole life, and he had also suffered from bronchitis, pneumonia, and emphysema. Aaccording to some sources, Mao's last words were: "I feel ill; call the doctors."

Mao's ”The Little red Book” or Mao Zedong on People's War (1967) became in the 1960s the ultimate authority for political correctness. It was carried about by millions during "Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution" of 1968. The plastic-bound work, edited by the minister of defense, Lin Piao, consisted of quotations from several Mao's writings, among them Significance of Agrarian Reforms in China, Strategic Problems of China's Revolutionary War, On the Rectification of Incorrect Ideas in the Party, A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire, On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People. Another compendium, also edited by Lin Piao, was entitled Long Live Mao Tse-Tung Thought.

Mao's conception of democracy was based on the leading role of the Communist party. Its the tightly disciplined organization would lead the masses. Though Confucianism emphasized submission to authorities and bureaucratic centralization, He was hostile to the philosophy, which he saw as the central ideology of China's past. Later in his career "The Great Helmsman" compared himself with Chin Shih-huang, the first Emperor, who unified China in 221 B.C.

For the most part, Mao's own philosophical work in the 1930s was summaries of Soviet texts. Two essays, 'On practice' and 'On contradiction' were printed in revised form in 1950 and 1952. These works, which could have been written in 1937, were studied and emulated throughout China.

Like Lenin, Mao made a distinction between antagonist and non-antagonist contradictions, but Mao's thought was partly derived from the Chinese system of yin and yang. He stated that contradictions would continue to arise in society even after socialist revolution. With this claim he supported his doctrine of permanent revolution, which was earlier launched by Trotsky. His success in guerrilla warfare led him to declare in 1947, that "the atom bomb is a paper tiger".

Mao's thoughts were also popular among Western intellectuals and radicals, who opposed "Soviet revisionism." American journalist E.P. Snow made Chinese Communist movement known already in the 1930s with his book Red Star Over China(1937). Snow's personal relationships with the leaders of China continued decades. He was granted permission travel in 1960 around the country. In his book The Other Side of the River Snow failed to report of China's 1959-61 famine, possibly the worst in history. Much of the grain which was produced in China during this period was traded for the Soviet weapons-technology. However, Mao's popularity has been enduring even after his death.

For further reading: Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-62 by Frank Dikotter (2010); Mao: The Unknown Story by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (2005); Chinese Marxism by Adrian Chan (2003); Children's Literature in China: From Lu Xun to Mao Zedong by Mary Ann Farquhar (1999); Mao Zedong by Jonathan D. Spence (1999);China's Road to Disaster by Frederick C. Teiwes and Warren Sun (1998); The 100 Most Influential Books Ever Written by Martin Seymour-Smith (1998); Battling Western Imperialism: Mao, Stalin, and the United States by Michael M. Sheng (1998); Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine by Jasper Becker (1997); The Private Life of Chairman Mao by Zhisui Li (1996, paperback); Mao Zedong by Rebecca Stefoff (1996, for young adults); No Tears for Mao by Niu-Niu et al (1995); Burying Mao by Richard Baum (1994); China Without Mao by Immanuel C.Y. Hsu (1990); The Thought of Mao Tse-Tung by Stuart Schram (1989, paperback);Inheriting Tradition by K. Louie (1986); Marxism, Maoism, and Utopianism by Maurice J. Meisner (1982); Chinese Thought, From Confucius to Mao Ts-E-Tung by Herrlee Glessner Glee (1971, paperback); Red Star over China by E.P. Snow (1937, rev. ed. 1968) -See also: Mao Tun - Suom.: Maolta on julkaistu runosuomennoksia antologiassa Itä on punainen. Muita käännöksiä: Mao Tse-tung; Runot (suom. Pertti Nieminen), essee- ja puhekokoelma Teoksia 1-2, Otteita puhemies Mao Tse-tungin teoksista, ”Punainen kirja” (1967)

Selected works:

Dialectical Materialism (Lecture Notes), Dalian: Dazhong Bookshop (n.d.)

Zhongguo she hui ge jie ji de fen xi, 1927

A Report of an Investigation into the Peasant Movement of Hunan, 1927

Wind Sand Poems (written in the 1930s, published years later)

Gendankai ni okeru konichi minzoku toitsu sensen no nimmu, 1937

Kang zhan bi sheng lun, 1937

China: The March Toward Unity, 1937 (with others)

Jiyu dokuritsu no shina kensetsu o mezashite, 1938

Lun chi jiu zhan, 1938

Kang Ri you ji zhan zheng di zhan shu wen ti, 1938 - Aspects of China’s Anti-Japanese Struggle (tr. 1948) / Strategic Problems in the Anti-Japanese Guerrilla War (tr. 1954)

The New Stage, by Mao Tse-tung. Report to the Sixth Enlarged Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist party of China, 1938

Zhongguo kang zhan de qian tu, 1938

You ji zhan zheng de zhan lue wen ti, 1938 - On Guerrilla Warfare (translated and with an introd. by Samuel B. Griffith II, 1961; introduction to 2nd ed. by Arthur Waldron and Edward O'Dowd; introduction and translation by Samuel B. Griffith II; bibliographical essay by Edward O'Dowd, 1992)

Kuan yu hsien cheng chu wen t'i, 1940

Zai Yan’an wen yi zuo tan hui shang de jiang hua, 1943 - Problems of Art and Literature (tr. 1950) / Talks at the Yenan Forum on Art and Literature (tr. 1956) / A Definitive Translation of Mao Tse-tung on Literature and Art (edited by Thomas N. White, 1967) / Mao Zedong's "Talks at the Yan'an Conference on Literature and Art" (a translation of the 1943 text with commentary, 1980)

China’s "New Democracy," 1944

Lun chi jiu zhan, 1944

Our Task in 1945, 1945

The Fight for a New China, 1945

Lun lian he zheng fu, 1945 - On Coalition Government (tr. 1945)

Jing ji wen ti yu cai zheng wen ti, 1947 - Mao Zedong and the Political Economy of the Border Region (translated by Andrew Watson, 1980)

Mao Tse-tung’s "Democracy"; A Digest of the Bible of Chinese Communism, 1947 (commentary by Lin Yutang, with expurgated passages restored)

Zhongguo ge ming zhan zheng de zhan lue, 1947

Turning point in China, 1948

Zhongguo ge ming he Zhongguo gong chan dang, 1948 - Chinese Revolution and the Communist Party of China (tr. 1950) / The Chinese Revolution and the Chinese Communist Party (tr. 1954)

Mao Zedong tong zhi lun xin min zhu zhu yi, 1948

The Autobiography of Mao Tse-tung, 1949 (2nd rev. ed.)

Hunan nong min yun dong kao cha bao gao, 1949

Lun ren min min zhu zhuan zheng, 1949 - On People’s Democratic Dictatorship (tr. 1949) / On People’s Democratic Rule (tr. 1950)

Lessons of the Chinese Revolution, 1950 (with Liu Shao-chi)

Significance of Agrarian Reforms in China, 1950

Mao Tse-tung hsuan chi, 1951

Shi jian lun, 1951 - On Practice: On the Relation Between Knowledge and Practice-Between Knowing and Doing, 1951

Strategic Problems of China’s Revolutionary War, 1951

Maoism, a Sourcebook: Selection from the Writings of Mao Tse-tung, 1952

Maodun lun, 1952 - On Contradiction, 1952

Gong chan dang ren fa kan zi, 1952 - Introductory Remarks to "The Communist" (tr. 1953)

Guan yu jiu zheng dang nei de cuo wu si xiang, 1952 - On the Rectification of Incorrect Ideas in the Party (tr. 1953)

Mind the Living Conditions of the Masses and Attend to the Methods of Work, 1953

On the Tactics of Fighting Japanese Imperialism, 1953

Report of an Investigation into the Peasant Movement in Hunan, 1953

A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire, 1953

Why Can China’s Red Political Power Exist, 1953

On the Protracted War, 1954

The Policies, Measures and Perspectives of Combating Japanese Invasion, 1954

Selected Works, 1954-62 (5 vols.)

Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society, 1956

The Question of Agricultural Co-operation, 1956

On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People, 1957

Imperialism and all Reactionaries Are Paper Tigers, 1958

Mao chu-hsi shih-tz'u san-shih chiu shou, 1958 [Poems of Mao Tse-tung]

On "Imperialism and All Reactionaries Are Paper Tigers", 1958

Lun wen xue yu yi shu, 1958 - On literature and art (3d ed., 1967)

Nineteen Poems, 1958 (with notes by Chou Chen-fu and an appreciation by Tsang Keh-chia)

Mao Zedong xuan ji suo yin, 1960

Mao Tse-tung on Art and Literature, 1960 (2nd ed.)

Comrade Mao Zedong on Marxist Philosophy, 1960 (extracts)

Mao Zedong's Philosophical Thought, 1960

New-Democratic Constitutionalism, 1960

Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, 1960-65, 1977 (5 vols.)

Chinese Communist Revolutionary Strategy, 1945-1949, 1961

Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung, 1961 (5 vols.)

Mao Tse-tung: An Anthology of his Writings, 1962 (edited with an introd. by Anne Fremantle)

The Political Thought of Mao Tse-tung, 1963 (ed. Stuart R. Schram)

Selected Military Writings of Mao Tse-tung, 1963

Mao chu-hsi shih-tz'u san-shih-ch'i shou, 1964 - Poems of Mao Tse-

tung (translated by Wong Man, 1966) / The Poems of Mao Tse-tung (translation, introd., notes by Willis Barnstone in collaboration with Ko Ching-po, 1972) / Poems of Mao Tse-tung (translated by Nieh Engle and Paul Engle, 1972) / Reverberations: A New Translation of Complete Poems of Mao Tse-tung (with notes by Nancy T. Lin, 1980) / Mao Zedong Poems (translated by Zhao Zhentao, 1980) / Snow Glistens on the Great Wall (translation, notes & historical commentary by Ma Wen-yee, 1986) / Poems of Mao Tsetung (translated by Kim Unsong, 1994)

Mao Zedong zhu zuo xuan du, 1964 (2 vols.)

Mao Zhu Xi Yu Lu, 1966 [Quotations of Chairman Mao, with Lin Biao] - "The Little Red Book" (first version, 1964)

Basic Tactics, 1966 (translated and with an introd. by Stuart R. Schram, foreword by Samuel B. Griffith, II)

Four Essays on Philosophy, 1966

Quotations From Chairman Mao, 1966

Mao Tse-tung on War, 1966

Mao Zedong lun wen yi, 1966

Poems, 1966

Ten More Poems of Mao Tse-tung, 1967

Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, 1967 (edited and with an introductory essay and notes by Stuart R. Schram, foreword by A. Doak Barnett)

Selected Readings, 1967

Mao Tse-tung’s Quotations: The Red Guard’s Handbook, 1967

Mao zhu xi yu lu = Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, 1967

Selected Readings of Mao Zedong's Writings, 1968 (2 vols.)

The Thoughts of Chairman Mao Tse-tung, 1967

Mao zhu xi de wu pian zhu zuo, 1968 - Five Articles by Chairman Mao Tse-tung (tr. 1968)

Mao zhu xi lun ren min zhan zheng = Chairman Mao Tse-tung on People’s War, 1968

The Wisdom of Mao Tse-tung, 1968

On Revolution and War, 1969 (edited with an introd. and notes by M. Rejai)

Supplement to Quotations from Chairman Mao, 1969

Mao Papers, Anthology and Bibliography, 1970 (edited by Jerome Ch?en)

Mao Zedong xuan ji = Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, 1970 (2 vols.)

Selected Works, 1970 (abridged by Bruno Shaw)

Quan shi jie ren min tuan jie qi lai = People of the World Unite and Defend the U. S. Agressors and All their Running Dogs!, 1971

Six Essays on Military Affairs, 1972

Wei ren min fu wu = Serve the People, in Memory of Norman Bethune, The Foolish Old Man Who Removed the Mountains, 1972

The Writings of Mao Zedong, 1949-1976, 1986 (Mao Zedong et al)

What Peking Keeps Silent About, 1972

Zhongguo ren min jie fang jun zong bu guan yu chong xing ban bu san da ji lu ba xiang zhu yi de xun ling = On the Reissue of the Three Main Rules of Discipline and the Eight Points for Attention, 1972

Mao Tse-tung Unrehearsed: Talks and Letters, 1956-71, 1974 (edited and introduced by Stuart Schram; translated by John Chinnery and Tieyun)

Annotated Quotations from Chairman Mao, 1975 (annotated by John DeFrancis)

Ten Poems and Lyrics, 1975 (translation and woodcuts by Wang Hui-Ming)

A Critique of Soviet Economics, 1977 (translated by Moss Roberts)

Maoism As It Really Is: Pronouncements of Mao Zedong, Some Already Known to the Public and Others Hitherto Not Published in the Chinese Press, 1981 (translated by Cynthia Carlile, ed. O.E. Vladimirov et al.)

Mao Zedong shu xin shou ji xuan = A Selection of Letters by Mao

Zedong with Reproductions of the Original Calligraphy, 1983

Mao Zedong ji. Bu juan = Supplements to Collected Writings of Mao Tse-tung, 1983-86 (10 vols.)

The Writings of Mao Zedong, 1949-1976, 1986-1992 (2 vols., edited by Michael Y.M. Kau, John K. Leung)

Mao Zedong's Collected Annotations on Philosophy, 1988

Secret Speeches of Chairman Mao: From the Hundred Flowers to the Great Leap Forward, 1989 (edited by Roderick MacFarquhar et al.)

Mao zhu wei kan gao, "Mao Zedong si xiang wan sui" bie ji ji qi ta = Maozhu weikan gao, "Mao Zedong sixiang wansui" beiji ji qita = Unofficially Published Works of Mao Zedong, Additional Volumes of "Long live Mao Zedong’s thought" and Other Secret Speeches of Mao, 1989 (15 vols.)

Mao Zedong on Dialectical Materialism: Writings on Philosophy, 1937, 1990 (edited by Nick Knight)

Report from Xunwu, 1990 (Xunwu diao cha, translated, and with an introduction and notes by Roger R. Thompson)

Mao’s Road to Power: Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, 1992-2005 (7 vols., ed. Stuart R. Schram)

Mao Zedong on Diplomacy, 1998 (compiled by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China and the Party Literature Research Center under the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China)

Mao Zedong shi ci = Mao Zedong Poems, 2001

On Practice and Contradiction, 2007 (introduction by Slavoj Zizek)

Mao Zedong shu fa da zi dian, 2010 (3 vols.)