Mahmood Rehearsed Spontaneity and the Conventionality of Ritual Dsiciplines of Salat

-

Upload

silverjade -

Category

Documents

-

view

142 -

download

10

Transcript of Mahmood Rehearsed Spontaneity and the Conventionality of Ritual Dsiciplines of Salat

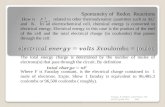

Rehearsed Spontaneity and the Conventionality of Ritual: Disciplines of "Ṣalāt"Author(s): Saba MahmoodSource: American Ethnologist, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Nov., 2001), pp. 827-853Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological AssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3094937 .

Accessed: 12/01/2014 11:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Wiley and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve andextend access to American Ethnologist.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity and the conventionality of ritual: disciplines of salat

SABA MAHMOOD University of Chicago

In the anthropology of ritual, one productive area of debate has focused on how the formal and conventional character of ritualized behavior is linked to, or distinct from, informal, routine, and pragmatic activity. In this article, I en- gage and extend this debate by analyzing various understandings of the Mus- lim act of prayer (salat) among a women's piety movement in contemporary Cairo, Egypt. Rather than assume a priori that conventional gestures and be- haviors necessarily accomplish the same goals, I inquire into the variable re-

lationships assigned to rule-governed behavior within different conceptions of the self under particular regimes of truth, power, and authority. In the sec- ond half of the article, I link my analysis of ritual to issues of embodiment, emotions, and individual autonomy, examining parallel conceptions of salat that coexist in some tension in contemporary Egypt. [ritual, embodiment, emotions, discipline, subject formation, Islam]

One distinguishing feature of ritual action is its formal and rule-governed charac- ter, which anthropologists have often juxtaposed with informal and spontaneous ac- tivity. Even among those anthropologists who have disagreed about whether ritual ac- tion is a type of human behavior (e.g., Bloch 1975; Douglas 1973; Turner 1969) or an aspect of all kinds of human action (e.g., Leach 1964; Moore and Myerhoff 1977), there seems to be consensus that ritual activity is conventional and socially pre- scribed, a characteristic that sets it apart from mundane activities (Bell 1992).1 This key opposition between formal and informal (or routine) behavior has provided the basis of other conceptual oppositions within theoretical elaborations on ritual, such as stereotypical versus spontaneous action, rehearsed versus authentic emotions, public demeanor versus private self.2 These series of interconnected distinctions are at the center of a productive and fruitful dialogue among anthropologists concerning the variable ways in which people link conventional or ritualized behavior with informal or mundane activity in different cultural systems.

One central concern within anthropological studies of ritual has been the place of emotion in ritual performance (see Bloch 1975; Evans-Pritchard 1965; Obeyesek- ere 1981; Radcliffe-Brown 1964; Rosaldo 1980; Tambiah 1985; Turner 1969). Draw-

ing on depth psychology, Victor Turner, for example, argues that ritual action is a means of, and space for, channeling and divesting the antisocial qualities of powerful emotions.3 Stanley Tambiah, on the other hand, in breaking from such an approach, contends that ritual as conventionalized behavior is not meant to "express intentions, emotions, and states of mind of individuals in a direct, spontaneous, and 'natural

way.' " Rather, according to Tambiah, ritual distances individuals from "spontaneous and intentional expressions because spontaneity and intentionality are, or can be,

American Ethnologist 28(4):827-853. Copyright ? 2001, American Anthropological Association.

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

american ethnologist

contingent, labile, circumstantial, even incoherent or disordered" (1985:132). Fol-

lowing this line of thought, other anthropologists have suggested that ritual is a space of "conventional" and not "genuine" (i.e., personal or individual) emotions (Kapferer 1979). Notably, despite some obvious differences, these contrasting conceptions of the role emotions play in ritual performance share a view of ritual as socially pre- scribed and formal behavior and, therefore, opposed to routine and pragmatic ac- tion.4 Ritual, in these views, is understood to be the space where individual psychic drives are either channeled into conventional patterns of expression or temporarily suspended so that a conventional social script may be enacted. Common to both these positions is the understanding that ritual activity is where emotional spontaneity comes to be controlled.

In this article, I would like to engage and extend this conversation, with special attention to how specific organizations of self and authority articulate differential rela-

tionships between informal activity and rule-prescribed social behavior (such as rit- ual). In drawing attention to the conceptual pairs that have informed the study of rit- ual, my aim is not to dismiss these oppositions, but to show the ways in which these

concepts are linked in complicated and variable ways depending on the discursive and practical conditions of authority and variable conceptions of personhood. Thus, my intent here is not to propose yet another definition of ritual but to inquire into the

relationships that conventional or formal acts articulate with intentions, spontaneous emotions, and bodily capacities under different contexts of power and truth.5

In doing so, I draw on ethnographic fieldwork I conducted among a women's pi- ety movement based in the mosques of Cairo, Egypt. The primary focus of this move- ment was the teaching and studying of Islamic scriptures, social practices, and forms of bodily comportment considered germane to the cultivation of the ideal virtuous self. As I will show, for the women I worked with, the ritual act of Muslim prayer (salat) did not require the suspension of spontaneous emotion and individual inten- tion, neither was it a space for a cathartic release of unsocialzed or inassimilable ele- ments of the psyche. Rather, in interviews with me, mosque participants identified the act of prayer as a key site for purposefully molding their intentions, emotions, and de- sires in accord with orthodox standards of Islamic piety. As a highly structured per- formance-one given an extensive elaboration in Islamic doctrine-prayer (salat) was understood by the women I worked with to provide an opportunity for the analysis, assessment, and refinement of the set of ethical capacities entailed in the task of real-

izing piety in the entirety of one's life, and was not a space conceptually detached from the daily tasks of routine living. I will argue, therefore, that the conscious process by which the mosque participants induced sentiments and desires in themselves, in accordance with a moral-ethical program, simultaneously problematizes the "natu- ralness" of emotions as well as the "conventionality" of ritual action, calling into

question any a priori distinction between formal (conventional) behavior and sponta- neous (intentional) conduct.

In as much as the women I worked with understood the body as a developable means for realizing the pious self, they took issue with other conceptions of salat prevalent in contemporary Cairo, especially those that treat the body as a signifying medium that stands in no determinate relationship to the self. In my discussion of these differences, I begin with the assumption that the significance of similar kinds of bodily practices even in the same cultural milieu is best apprehended through an analysis of the particular conception of self and authority in which these practices re- side. Further, I argue that insofar as conventional and rule-governed behavior cannot be read simply as a social imposition that constrains the self but rather (under certain

828

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity

conditions) as the means by which the self is realized, my analysis has implications for how anthropologists might think about the politics of individual freedom.

piety and conventionality

As part of the Islamic revival (al-Sahwa al-lslamiyya) in Egypt, the women's

mosque movement emerged 20 years ago when women started to organize weekly religious lessons-first at their homes and then within mosques-to read the Quran, the hadTth (the sayings and actions of the Prophet Muhammad), and associated exe-

getical literature.6 According to the participants, the women's mosque movement

emerged in response to the perception that religious knowledge, as a means to organ- izing daily conduct, had become increasingly marginalized under modern structures of secular governance. This trend, usually referred to by the movement's participants as secularization ('almana) or westernization (taghrb), is seen to have reduced Is- lamic knowledge (both as a mode of conduct as well as a set of principles) to an ab- stract system of beliefs that has no direct bearing on the practicalities of daily living. An important aspect of the mosque movement's critique of Egyptian society focuses on the ways in which the understanding and performance of acts of worship (ibadat) have been transformed in the modern period. In interviews with me, the participants argued that ritual acts of worship in the popular imagination have increasingly ac-

quired the status of customs, a kind of "Muslim folklore," undertaken as a form of en- tertainment or as a means to display a religio-cultural identity. Such an under-

standing, many of them said, has resulted in a decline of the role of ritual performance as a means to the training and realization of piety in the entirety of one's life, a role

they seek to restore through the remedial pedagogy of the mosque lessons. The women's mosque movement, therefore, seeks to preserve those virtues, ethi-

cal capacities, and forms of reasoning that the participants perceive to have become unavailable or inaccessible to ordinary Muslims. The practical efforts of the mosque movement are directed at instructing Muslims not only in the proper performance of

religious duties and acts of worship but, more importantly, familiarizing them with the

exegetical tradition of the Quran and the hadith. Instruction in this tradition, however, is geared less toward inculcating a scholarly knowledge of the texts than toward a

practical understanding of how these texts should guide one's conduct in daily affairs. Insofar as the mosque movement aims to make Egyptian society more religiously de- vout within the existing structures and policies of the state, it is distinct from the state- oriented Islamist political groups that have been the focus of most academic studies of the Islamist movement. Yet the women's mosque movement should not be under- stood as a withdrawal from sociopolitical engagement in as much as the form of piety it seeks to realize entails the transformation of many aspects of social life in Egypt.7

This is the first time in Egyptian history that such a large number of women, from a wide variety of socioeconomic backgrounds, has played a central role in the institu- tion of the mosque and Islamic pedagogy, both of which have been male-dominated domains. The women's mosque movement, however, does not aim to reinterpret the male exegetical tradition from a feminist stance, but is exclusively grounded in the es- tablished interpretive tradition of Islam associated with the four schools of Sunni Is- lamic thought (Hanbali, Shafa'i, Maliki, and Hanafi).8 Although most Egyptian women have had some measure of training in piety, the mosque movement is unique in making a

religious discourse that had largely been limited to male institutions of high theology popular among women from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds (Mahmood in

press).9 It now competes with parallel secular traditions of self-cultivation available to

contemporary Egyptians.10

829

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

american ethnologist

The forms of piety being taught by the mosque participants should not be seen, however, simply as a recuperation of past traditions. The conditions within which this form of piety is being realized are quite distinct from those previously encountered by women. Whether it is working in mixed-sex offices, riding public transportation, at-

tending coeducational schools, or consuming contemporary forms of mass entertain- ment, women in Egypt have to deal with a variety of situations that their mothers' and

grandmothers' generations did not encounter. As many of the mosque participants ar-

gued, their movement is precisely a response to the problem of living piously under conditions that have become increasingly ruled by a secular rationality. I have ex-

plored the paradox such a movement poses to the study of gender and feminist poli- tics elsewhere (Mahmood 2001). My focus in this article is on the role certain forms of conventional behavior and emotional expressions play within the larger disciplinary program pursued by the mosque participants in their cultivation of piety.

prayer and pragmatic action

The condition of piety was described by the mosque participants I knew as the

quality of "being close to God": a manner of being and actingthat suffused all of one's acts, both religious and worldly in character. Although the consummation of a pious deportment entailed a complex ethical disciplinary program, at a fundamental level it

required that the individual perform those acts of worship made incumbent upon Muslims by God (al-fara'iid), as well as Islamic virtues (fada' i) and acts of beneficence that secure God's pleasure (al-a'mal al-saliha).1' Examples of the latter include practic- ing modesty, fulfilling social and familial obligations, and performing supererogatory prayers. The attitude with which these acts are performed is as important as their pre- scribed form: Sincerity (al-ikhlas), humility (khushol), and feelings of virtuous fear and awe (khashya or taqwa), are all emotions by which excellence and virtuosity in piety are measured and marked. Many of the mosque attendees observed to me that al- though they had always been aware of the basic duties required of them as Muslims, it was only their attendance in the mosque groups that provided them with the neces- sary skills to be able to achieve excellence and higher levels of devotion in their practice.

According to the mosque participants with whom I spoke, among the minimal re- quirements critical to the formation of a virtuous Muslim is the act of praying five times a day. The performance of prayer (sing. salat, pl. salawat) is considered to be so centrally important in Islam that whether someone who does not pray regularly can qualify as a Muslim has been a subject of intense debate among theologians.12 Salat is an act of prayer the correct execution of which depends on the following elements: (1) an intention to dedicate the prayer to God, (2) a prescribed sequence of gestures and words, (3) a physical condition of purity, and (4) proper attire. While fulfilling these four conditions renders prayer acceptable (maqbol), I was told it is also desir- able that salat be performed with all the feelings, concentration, and tenderness of the heart appropriate to when one is in the presence of God-a state called khush'.

Although it is understandable that an ideal such as khushou had to be learned through intense devotion and training, it was surprising to me that mosque partici- pants considered the desire to pray five times a day (with its minimal conditions of performance) an object of pedagogy. As many of the participants reported to me, they did not pray diligently and seemed to lack the requisite will to accomplish what was required of them. Because such states of will were not assumed to be natural by the teachers and their followers, women took extra care to teach each other the means by which the desire to pray could be cultivated and strengthened in the course of con- ducting the sort of routine, mundane actions that occupied most women during the day.

830

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity

The complicated relationship between the performance of salat and one's daily activities was revealed to me in a conversation with three women, all of whom regu- larly attended lessons in different mosques of their choice in Cairo. They were part of a small number of women whom I had come to regard as experienced in the cultiva- tion of piety. My measure for coming to such a judgment was none other than the one used by the mosque participants: They not only carried out their religious duties (al- fara'id) diligently, but also attested to their faith (iman) by continuously doing good deeds (al-a'mal al-saliha) and practicing virtues (al-fadai'l). As the following exchange makes clear, the women pursued the process of honing and nurturing the desire to

pray through the performance of seemingly unrelated deeds during the day until that desire became a part of their conditions of being.

The setting for this conversation was a mosque in downtown Cairo. Because all three of the women work as clerks in the local state bureaucracy in the same building, it was convenient for them to meet in the neighboring mosque in the late afternoons after work on a weekly basis. Their discussions sometimes attracted other women, who had come to the mosque to pray. In this instance, a young woman in her early twenties had been sitting and listening intently, when she suddenly interrupted the discussion to ask a question about one of the five basic prayers required of Muslims, a

prayer known as al-fajr. This prayer is performed right after dawn breaks and before sunrise. Many Muslims I know consider it the most demanding and difficult of prayers because it is hard to leave the comfort of sleep to wash and pray and also because the

period within which it must be performed is very short. This young woman expressed the difficulty she encountered in performing the task of getting up for the morning prayer and asked the group what she should do about it. Mona, a member of the

group who is in her midthirties, turned to the young woman with a concerned expres- sion on her face and asked, "Do you mean to say that you are unable to get up for the

morning prayer habitually and consistently?" The girl nodded in agreement. Bearing the same concerned expression on her face, Mona said, "You mean to say that you forbid yourself the reward [sawab] of the morning prayer? This surely is an indication of ghafla on your part?" The young woman looked somewhat perturbed and guilty but

persisted and asked, "What does ghafla mean?" Mona replied that it refers to what

you do in the day: If your mind is mostly occupied with things that are not related to God, then you are in a state of ghafla (carelessness, negligence). According to Mona, such a condition of negligence results in inability to say the morning prayer.

Looking puzzled, the young woman asked, "What do you mean what I do in the

day? What does my saying of the prayer [salat] have to do with what I do in the day?" Mona answered:

It means what your day-to-day deeds are. For example, what do you look at in the day? Do you look at things that are prohibited to us by God, such as immodest images of women and men? What do you say to people in the day? Do you insult people when you get angry and use abusive language? How do you feel when you see someone do- ing an act of disobedience [ma'asi]? Do you get sad? Does it hurt you when you see someone committing a sin or does it not affect you? These are the things that have an effect on your heart [qalbik], and they hinder or impede [ta'attal] your ability to get up and say the morning prayer. [The constant] guarding against disobedience and sins wakes you up for the morning prayer. Salat is not just what you say with your mouth and what you do with your limbs. It is a state of your heart. So when you do things in a day for God and avoid other things because of Him, it means you're thinking about Him, and therefore it becomes easy for you to strive for Him against yourself and your desires. If you correct these issues, you will be able to rise up for the morning prayer as well.

831

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

american ethnologist

Perhaps responding to the young woman's look of concentration, Mona asked her, "What is it that annoys you [bitghfzik] the most in your life?" The young woman answered that her sister fought with her a lot, and this bothered her and made her an-

gry most days. Mona replied:

You, for example, can think of God when your sister fights with you and not fight back with her because He commands us to control our anger and be patient. For if you do get angry, you know that you will just gather more sins [dhunub], but if you are quiet then you are beginning to organize your affairs on account of God and not in accord with your temperament. And then you will realize that your sister will lose the ability to make you angry, and you will become more desirous [raghiba] of God. You will be- gin to notice that if you say the morning prayer, it will also make your daily affairs eas- ier, and if you don't pray it will make them hard.

Mona looked at the young woman who had been listening attentively and asked: "Do you get angry and upset [tiz'ali] when you don't say your morning prayer?" The

young woman answered yes. Mona continued:

But you don't get upset enough that you don't miss the next morning prayer. Perform- ing the morning prayer should be like the things that you can't live without: for when you don't eat, or you don't clean your house, you get the feeling that you must do this. It is this feeling that I am talking about: there is something inside you that makes you want to pray and gets you up early in the morning to pray. And you're angry with your- self when you don't do this or fail to do this.

The young woman looked on and listened, not saying much. At this point, we moved back to our previous discussion, and the young woman stayed with us until the end.

The answer that Mona provided to this young woman is not a customary answer, such as invoking the fear of God's retribution for habitually failing to perform one's

daily prayers. Mona's response reflects the sophistication and elaboration of someone who has spent considerable time and effort in familiarizing herself with an Islamic in-

terpretive tradition of moral discipline. I would like to draw attention here to the

economy of discipline at work in Mona's advice to the young woman, particularly the

ways in which ordinary tasks in daily life are made to attach to the performance of consummate worship. Notably, when Mona links the ability to pray to the vigilance with which one conducts the practical chores of daily living, all mundane activities- like getting angry with one's sister, the things one hears and looks at, the way one

speaks-become a place for securing and honing particular moral capacities. As is evident from the preceding discussion, the issue of punctuality clearly entails more than the simple use of an alarm clock: it encompasses an entire attitude one cultivates in order to create the desire to pray. Of significance is the fact that Mona does not as- sume that the desire to pray is natural, but that it must be created through a set of dis- ciplinary acts. These include the effort to avoid seeing, hearing, and speaking about things that make faith (iman) weaker and instead engaging in those acts that strengthen the desire for, and the ability to enact, obedience to God's will. The re- peated practice of orienting all acts toward securing God's pleasure is a cumulative process the net result of which, on one level, is the ability to pray regularly and, on an- other level, the creation of a pious self.

This understanding of ritual prayer posits an ineluctable relationship between conventional or rule-governed action and routine and practical conduct. Note that in Mona's formulation, ritual prayer is conjoined and interdependent with pragmatic and utilitarian activities of daily life, actions that must be monitored and honed as conditions for the performance of the ritual itself. Insofar as disciplining mundane

832

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity

conduct is integral to the consummation of ritual action, this understanding proble- matizes the separation that some theorists of ritual have drawn between ritual and

pragmatic action (e.g., Bloch 1974; Leach 1964; Turner 1976). For women like Mona, the performance of salat is one among a continuum of other practices that serve as the

necessary means to the realization of a pious self and are the critical instruments in the teleological program of self-formation. This understanding was echoed in a com- ment I often heard among the mosque participants to the effect that the act of prayer performed for its own sake, and without adequate regard for how it contributes to the realization of piety, is "lost power" (quwwa mafqcda).

Mona's discussion of ritual prayer problematizes another polarity, central to a number of anthropological discussions of ritual, that between the spontaneous ex-

pression of emotion and its theatrical performance. This polarity, found in the work of Evans-Pritchard (1965) and Maurice Bloch (1975) among others, is most succinctly stated by Tambiah in the quote I cite above: "ritual as conventionalized behavior is not designed or meant to express intentions, emotions, and states of mind of individu- als in a direct, spontaneous, and 'natural way"' (1985:132). Demonstration of affect in ritual, according to Tambiah, should not be understood as "a 'free expression of emo- tions' but a disciplined rehearsal of 'right attitudes' " (1985:134).13 Tambiah's point would seem to capture well certain aspects of Mona's understanding of ritual as a

space for the enactment of socially prescribed behaviors, including those involving the expression of affect. Yet such a parceling of spontaneous emotions and disci-

plined gesture and attitude remains incongruous with other key aspects of the formu- lation of ritual prayer that Mona elaborates.

As is clear from the example above, in Mona's understanding the enactment of conventional gestures and behaviors devolves on the spontaneous expression of well rehearsed emotions and individual intentions, thereby directing attention to how one learns to express "spontaneously" the "right attitudes." For women like Mona, ritual (i.e., conventional, formal action) is understood as the space par excellence of making their desires act spontaneously in accord with pious Islamic conventions. Thus, ritual

worship, for the women I worked with, was both enacted through, and productive of, intentionality, volitional behavior, and sentiments-precisely those elements that are assumed by Tambiah and others to be bracketed in the performance of ritual. Impor- tantly, in this formulation ritual is not regarded as the theater in which a preformed self enacts a script of social action. Rather, it is one among a number of sites where the self comes to acquire and give expression to its proper form. In addition, insofar as such a view seeks to construct and mold emotions according to a prescribed program of self formation, it also problematizes the notion that ritual is a space of release for natural or physiological emotions (Turner 1969)-a point that I explore below in my discussion of the emotion of fear and its role in the performance of prayer.14

Talal Asad, in a significant article on the emergence of the anthropological cate-

gory of ritual, argues that that it was only at the turn of the 20th century in Western

European history that ritual lost its earlier meaning as "a script for regulating practice" (ritual as a manual) and came to be understood primarily as a type of practice, sym- bolic and communicative in character, and distinct from technical and effective be- havior (1993:57-58). Asad links this shift to a number of developments in European history whereby the modern self increasingly came to be interiorized, its outward ex-

pressions conceptually detached from an essential core of the privatized self, a site from which authentic emotions were understood to emanate (see also Burke 1997; Hundert 1997; Smith 1997). Building on this argument, Asad analyzes a number of monastic rites from the medieval Christian period understood by the monks who

833

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

american ethnologist

practiced them as disciplinary practices "directed at forming and reforming Christian

dispositions" (1993:131). As he argues, liturgical practices, among the Cistercian monks he studied, were not simply symbolic and communicative acts, but perform- ances through which the subject's very will, desire, intellect, and body came to ac-

quire a particular form. Indeed, if, as Asad argues, the meaning of ritual cannot be fixed in terms of its for-

mal or conventional character within European history, then the question arises: How are scholars to analyze formal and rule-governed behavior so as to understand the

radically different roles it plays under different conceptions of self and authority? Thus, rather than assuming a priori that formal behavior necessarily stands in a par- ticular relationship to social authority and the subject's actions, Asad's work encour-

ages the question: What are the variable and varied relations between conventional behavior and the formation of the self under different traditions of discipline and self formation?"5

Asad focuses on medieval Christian understandings of ritual. In what follows I want to analyze two contrasting understandings of ritual behavior and its relationship to moral action that coexist within contemporary Egypt. My intent is to show that con- ventional behavior may articulate variable relationships with specific conceptions of the self, not only across different historical registers as Asad's work suggests, but also within the same cultural milieu. In order to explore this point, I will juxtapose Mona's discussion with another understanding of ritual prayer found among many Egyptian Muslims today. As my analysis will demonstrate, beneath these two arguments about the meaning and performance of salat lie very different assumptions about the rela-

tionship between the body, in its various gestural and emotive capacities, and the moral self. Thus, my exposition of the mosque participant's understanding of ritual

prayer should not be taken to stand in for an "Islamico-cultural" conception of the self that applies to all contemporary Egyptian Muslims. Rather, my analysis is an elucida- tion of two radically different economies of prayer, with their concomitant matrices of

power, truth, and disciplinary practices, which coexist in some tension in Egypt to-

day.

economies of discipline

A central aspect of ritual prayer, as understood by most mosque participants and captured in Mona's discussion above, is that it serves both as a means to pious con- duct and an end. In this logic, ritual prayer (salat) is an end in that Muslims believe God requires them to pray, and a means insofar as it is born out of, and transforms, daily action, which in turn creates or reinforces the desire for worship. Thus, the de- sired goal (i.e., pious worship) is also one of the means by which that desire is culti- vated and gradually made realizable. In fact, in this world view, neither consummate worship nor the acquisition of piety is possible without the performance of prayer in the prescribed (i.e., codified) manner and attitude. As such, ritual worship is both part of a larger program of discipline through which piety is realized and a critical condi- tion for the performance of piety itself.

Despite its centrality to the mosque participants, this understanding of ritual as both means and end was not one shared by all Egyptian Muslims. Consider, for exam- ple, Mona Hilmi's interpretation of salat. Hilmi is a columnist who writes for Rcz al- Yusuf, a popular weekly magazine that represents a liberal-nationalist perspective in the Egyptian press. What prompted the appearance of her article was the arrest of sev- eral teenagers from upper-middle-class and upper-class families for allegedly partici- pating in "devil worship" ('abdat al-shaitan). This incident was widely reported in the

834

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity

Egyptian press and, in part, prompted a discussion about the appropriate role of relig- ion-in particular ritual worship-in Egyptian society. Hilmi writes:

The issue is not whether people perform rituals, and acts of worship [bibadat] either to get recompense or reward [sawab], or out of fear of God, or the desire to show off in front of other people. The issue instead is how rituals [tuqos] and worship [Libadat] pre- pare for the creation of a type of person who thinks freely, is capable [mauhil] of en- lightened criticism on important daily issues, of distinguishing between form and essence, between means and ends, between secondary and basic issues. The biggest challenge is how to transform love for God inside every citizen [mawatin wa mawatina] into continuous self-criticism of our daily behaviors and manners, and into an awak- ening of innovative/creative revolutionary thought that is against the subjugation of the human beings and the destruction of his dignity. [Hilmi 1997:81 ]

Clearly Hilmi's argument engages the importance of religious practice in Egyp- tian society, but it is an interpretation of ritual practice that is quite distinct from the one that Mona and her friends espoused. First, Hilmi and the women with whom I worked voice clear differences about the kind of person to be created in the process of performing rituals. Hilmi imbues her view of what a human being should become with the language and goals of liberal-nationalist thought. For example, the highest goal of worship for her is to create a human being capable of "enlightened criticism on important daily issues" and "revolutionary thought that is against the subjugation of human beings" (1997:81). As a result, Hilmi addresses "the citizen" (mawatin wa mawatina) in her call to duty rather than "the faithful" (mu'min wa mu'mina) or "slaves of God" ('ibad Allah), the terms more commonly used by the women with whom I worked. In contrast, for many of the mosque participants, the ultimate goal of worship was the natural and effortless performance of the virtue of submission to God. Even though women like Mona subjected their daily activities to self-criticism (as the author recommends), it was done in order to secure God's approval and pleas- ure rather than to hone those capacities referred to by Hilmi and central to the defini- tion of the modern-autonomous citizen.'16 do not mean to suggest that the discourses of nationalism have been inconsequential in the development of the mosque move- ment or that the modern state and its forms of power (social, political, and economic) have not shaped the lives of the women I worked with in important ways. My point is simply that the inculcation of ideals of enlightened citizenship was not the aim of worship for the women of the mosque movement as it seems to be for Hilmi. What these contrasting interpretations of ritual prayer reveal is not only a disagreement re- garding the goals of the act, but also distinctly different presuppositions about the re- lationship between conventional and routine behavior in the construction of the self.

This becomes further evident if I contrast the views of Hilmi with the means and end relationship undergirding Mona's conception of salat (discussed above). For Hilmi, I would argue, it seems that the goal of creating modern autonomous citizens remains independent of the means she proposes (i.e., Islamic rituals). Indeed, various modern societies, it appears, have accomplished the same goal through other means. In Hilmi's schema, I would contend, therefore, that the means (i.e., ritual salat) and the end (i.e., the model liberal citizen) can be characterized without reference to each other; and a number of quite different means may be employed to achieve one and the same end. In other words, whereas rituals such as salat may, in Hilmi's view, be

usefully enlisted for the project of creating a self-critical citizenry, they are not neces-

sary but contingent acts in the process. Hence Hilmi emphasizes the citizen's ability to distinguish between essence and form-that is, between an inner meaning concep- tually independent from the outward performances that express it-and the dangers

835

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

american ethnologist

of conflating the two. In contrast, for women like Mona, ritual acts of worship, as I show above, are the sole and ineluctable means of forming pious dispositions. In other words, prescribed rituals are the means by which pious capabilities are devel-

oped and internal to their practice. What I want to suggest is that in an imaginary like Mona's, where external behav-

ioral forms and formal gestures are integral to the realization and expression of the self, the concept of the self and its relation to the body (its variable modes of action and expression) are quite different from the ones discussed by Hilmi. In Hilmi's view, external behavior may serve as a means of disciplining the self but, as I have shown above, remains inessential to that self.17 Thus the conceptual articulation of formal

practices in relation to oneself and others differs in these two imaginaries and, by ex- tension, the implications for power and authority vary as well (a point to which I re- turn in the conclusion).

Let me elaborate on this point by drawing on an article written by Gregory Star- rett (1995) in which he analyzes different commentaries written by Muslims and non- Muslims about Islamic rituals in both the pre- and postcolonial period in Egypt.18 Star- rett argues that the performance of Islamic rituals may be usefully explored through Bourdieu's notion of habitus and body hexis (Bourdieu 1977, 1980). Starrett begins by taking issue with Bourdieu's claim that hexis and habitus are necessarily best under- stood as unconscious and ineffable phenomena, learned through imitative practice rather than explicit discourse. Starrett makes his critique in light of the well-developed corpus of explicit instruction and commentary that exist in Islam regarding embodied

practices. According to Starrett, issues of bodily hexis-what he terms "embodiment of ideology in habit"-may be best understood "as a set of processes through which individuals and groups consciously ascribe meaning to ... bodily disposition, and es- tablish, maintain, and contest publicly its political valence" (1995:954).

To support this argument, Starrett draws on two distinct bodies of writing about Islamic rituals. The first is a set of remarks made by colonial officers, European mis- sionaries, and travelers in the late 19th century about the primitive and irrational character of Islamic beliefs and rituals. For these observers, Islamic ritual was marked

by a profusion of movement, sound, emotion, and a general preoccupation with the

inconsequential minutia of bodily practices rather than an attention to matters of the soul (1995:955-960). Starrett juxtaposes these comments with contemporary writings in Egypt on the subject, particularly passages about Muslim prayer (salat) from text- books used in the curricula of public schools. Not unlike the passage I quote above (Hilmi 1997), these textbooks recruit the individual and collective performance of salat into the project of creating a modern Egyptian citizenry, proffering a list of the ra- tional and scientific benefits that accrue from the performance of salat, both to the in- dividual and the social body.19 Starrett argues: "This evaluation of the hexis of prayer reverses the Victorian reading of Muslim rituals (which marked them as primitive and stultifying), making them God's own sign of cultural advancement and order" (1995:963). Starrett concludes that "various Muslim interpretations of their own bod- ily disposition, [and] Victorian interpretations of that disposition ... while different in content, are formally similar. All invest the body hexis with ideological contents that serve in part to validate the worldview of the observer and establish specific social and political relationships with the observed" (1995:964; emphasis added).

Although I agree with Starrett that debates about bodily matters express struggles over contrasting models of society and community, his treatment of the status of the body in these debates needs to be questioned. Starrett evaluates the body largely as a signifying medium that can be read differentially by different sociopolitical actors in

836

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity

accord with their ideological interests. But what he fails to consider is whether the

body's potentiality is significant to every ideological system in the same way? Is the body with its behavioral forms simply the theater in which ideological scripts are en- acted and to which different readings may be ascribed? In this article, I have tried to

argue that the body's conceptual relationship with the self and others, and the ways in which it articulates with structures of authority, varies under different discursive re-

gimes of power and truth precisely because the body's ritual practices endow it with different kinds of capabilities.

In order to grasp this point it is necessary, however, to understand the body and its behavioral forms not only in its capacity as a signifying medium, but also as a tool for becoming a certain kind of a person and attaining certain kinds of states (Asad 1993; Mauss 1979). Starrett is correct, of course, that the nationalist discourse treats the body as a signifying medium wherein the ordered performance of collective wor-

ship is taken to be a sign of a well-disciplined nation (as do other public events of na- tional import). Yet for women like Mona, as is clear from my discussion above, bodily forms are at the center of the self's potentialities, both in the subjective and social sense. What I have presented here are two distinctly different views of ritual, one in which ritual organizes practices aimed at the development and formation of an em- bodied self, and another in which, to borrow Asad's words, ritual "offers a reading of a social institution" (1993:78). It is important, therefore, to recognize the disparate or-

ganizations of the body-self undergirding these different conceptions of ritual and to

analyze the conditions under which parallel and overlapping traditions of reasoning and moral formation exist, not only in different historical and cultural contexts, but also within a single cultural milieu.

habitus and (un)conscious intentions

In this article, insofar as I address the theme of bodily inculcation through ritual

practice, it is worthwhile to examine briefly the utility of Bourdieu's (1977, 1980) no- tion of habitus for the analysis of Islamic teachings. Although Bourdieu's concept of habitus has proven to be a productive tool for discussions of embodiment, its useful- ness in the analysis of the kind of disciplinary practices I have explored above, I would ague, is somewhat limited. Bourdieu proposed the notion of habitus as a means to integrate conceptually phenomenological and structuralist approaches so as to elucidate how the supraindividual structure of society comes to be lived in human

experience. For Bourdieu, habitus is a "generative principle" through which "objec- tive conditions" of a society are inscribed in the bodies and dispositions of social ac- tors (1977, 1980). According to Bourdieu, structured dispositions that constitute habi- tus correspond to an individual's class or social position and are engendered "in the last analysis, by the economic bases of the social formation in question" (1977:83). Although Bourdieu acknowledges that habitus is learned-in the sense that no one is born with it-his primary concern is with the unconscious power of habitus through which objective social conditions become naturalized and reproduced. He argues that "practical mimesis" (the process by which habitus is acquired)

has nothing in common with an imitation that would presuppose a conscious effort to reproduce a gesture, an utterance or an object explicitly constituted as a model ... [instead] the process of reproduction ... tend[s] to take place below the level of con- sciousness, expression and the reflexive distance which these presuppose .... What is 'learned by the body' is not something that one has, like knowledge that can be bran- dished, but something that one is. [1980:73]

837

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

american ethnologist

Apart from the socioeconomic determinism that characterizes Bourdieu's discus- sion of bodily dispositions, what I find problematic in this approach is the lack of at- tention to the pedagogical process by which a habitus is learned. 20 As is clear from the ethnographic example I provide above, among the mosque participants I worked with, the body was thematized as a site of moral training and cultivation, thereby problematizing the narrow model of unconscious imbibing that Bourdieu assumes in his discussion of habitus. Yet conscious training in the habituation of virtues itself was undertaken, paradoxically, to make consciousness redundant to the practice of these virtues. This is evident in Mona's advice to the young woman when she says that one should become so accustomed to the act of praying five times a day that when one does not pray one feels just as uncomfortable as when one forgets to eat: At this stage, the act of prayer has attained the status of almost a physiological need that is fulfilled without conscious reflection. Yet it would be a mistake to say that mosque partici- pants believe that once a virtue has taken root in one's disposition it issues forth per- functorily and automatically. Insofar as the point is not simply thatone acts virtuously but also how one enacts a virtue (with what intent, emotion, commitment, etc.), con- stant vigilance and monitoring of one's practices is a critical element in this model of ethical formation. This economy of self-discipline, therefore, draws attention to the role self-directed action plays in the learning of an embodied disposition and its rela-

tionship to "unconscious" ways of being.21 Bourdieu's failure to attend to pedagogical moments and practices in the process of acquiring a habitus results in a neglect of the

historically and culturally specific embodied capacities that different conceptions of the subject require. It also neglects the precise role various traditions of bodily disci-

pline play in becoming a certain kind of a subject.22 In analyzing the role of conscious training in the acquisition of embodied dispo-

sitions within the practices of the mosque movement, I have found it useful to draw on an older genealogy of habitus that was first developed by Aristotle and later came to inform both the Christian and Muslim traditions.23 Habitus in this formulation is concerned with ethical formation and presupposes a specific pedagogical process by which a moral character is acquired. In this understanding, both vices and virtues- insofar as they are considered to be products of human endeavor, rather than revela-

tory experience or natural temperament-are acquired through the repeated perform- ance of actions that entail a particular virtue or vice, until all behavior comes to be

regulated by the habitus. Thus habitus in this tradition of moral cultivation implies a

quality that is acquired through human industry, assiduous practice, and discipline such that it becomes a permanent feature of a person's character. Premeditated learn- ing is a teleological process aimed at making moral behavior a nondeliberative aspect of one's disposition. Bourdieu, in drawing on the Aristotelian tradition, retains the sense of habitus as durable, embodied dispositions, but he leaves aside the pedagogi- cal aspect of the Aristotelian notion as well as the context of ethics within which the concept was developed. Thus, although Bourdieu uses habitus in a more restricted sense to focus on how ideology is inscribed on the body, the practices of the mosque participants suggest a more complicated usage in which issues of moral formation stand in a specific relationship to a particular kind of pedagogical model.

The Aristotelian understanding of the process by which moral character is formed influenced a number of Islamic thinkers, foremost among them the 11th-century theologian Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (d. 1 1 1 1), but also al-Miskawayh (d. 1030), Ibn Rushd (d. 1 198), and Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406).24 Al-Ghazali's work has exerted consid- erable influence on Muslim reformers in the modern period and is also continuously referenced and cited among the participants of the mosque movement.25 Although

838

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity

al-Ghazali's work and its contemporary adaptations do not use the term habitus per se, the principle invoked in explaining how outward behavior shapes moral character bears a clear resemblance to Aristotelian discussions of habitus.

The historian Ira Lapidus, in his analysis of the work of the 14th-century Muslim thinker Ibn Khaldun, discusses this principle in relation to the Arabic term malaka.

Lapidus argues that although Ibn Khaldun's use of the term malaka has often been translated as "habit," its sense is best captured in the Latin term habitus, what Lapidus describes as "that inner quality developed as a result of outer practice which makes

practice a perfect ability of the soul of the actor" (1984:54).26 Malaka, therefore, is an

acquired excellence at a moral or practical craft, learned through repeated practice until that practice leaves a permanent mark on the character of the person. In terms of faith, malaka, according to Lapidus, "is the acquisition, from the belief of the heart and the resulting actions, of a quality that has complete control over the heart so that it commands the action of the limbs and makes every activity take place in submissive- ness to it to the point that all actions, eventually, become subservient to this affirma- tion of faith. This is the highest degree of faith. It is perfect faith" (1984:55-56). What is notable in this formulation is the way inward dispositions (emotions, intentions, de- sires, etc.) are understood to articulate with visible behaviors (gestures, speech, bodily motions, etc.), and the two are made to synchronize in accord with a specific model of exemplary behavior.

induced weeping, fear, and felicity

Let me elaborate the principle undergirding the model of ethical formation out- lined above through an analysis of one of the organizing principles within the discipli- nary practices of the mosque lessons: the triad of fear (al-khauf), hope (al-raja'), love (al-hubb).27 The process of cultivating and honing a pious disposition among the mosque participants centered not only around the practical tasks of daily living, but also the creation and orientation of the emotions such a disposition entailed. No other theme of the mosque lessons captured the emotive aspect of this disciplinary program better than the tripartite theme of fear-hope-love, so often evoked by the teachers and attendees. As elaborated in the mosque lessons, the principle of fear (al-khauf) refers to the dread one feels from the possibility of God's retribution (e.g., fires of hell), an

experience that leads one to avoid indulging in those actions and thoughts that may earn His wrath and displeasure; hope (al-raja') is the anticipation of the beneficence (hasanat) one accrues with God for undertaking religious duties and good deeds; and the principle of love (al-hubb) refers to the affection and devotion one feels for God, which in turn inspires one to pursue a life in accordance with His will and pleasure. Thus, each emotion is tied to an economy of action that follows from the experience of that particular emotion.

For a long period during my work with the mosques, I understood this tripartite matrix of emotion and action in terms of the "carrot and stick" of religious discipline. It appeared to me that the elements of hope and love were the "carrot" of religion, in- somuch as the promise of gaining merit or recompense (hasanat) with God inspired one to undertake religious duties. Likewise, fear of God's wrath was the "stick" that motivated one to abstain from sins and vices. It was only toward the end of my two-

year period of fieldwork that I began to realize the triad's complex relationship to the

larger system of pedagogy wherein these emotions are constituted, not simply as mo- tivational devices, but as integral aspects of pious action itself. Moreover, it became

apparent to me that the argument that people are driven to behave piously because of the fear of hell or the promise of beneficence leaves unexplained what it seeks to answer:

839

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

american ethnologist

specifically how these emotions come to be cultivated and command authority in the

topography of a particular moral-passional self. In what follows, therefore, I want to attend to the specific texture of these emotions-in particular fear-and how they came to be constituted as motives for, and modalities of, pious conduct in the realiza- tion of an obedient and virtuous life.

Consider the following excerpt from a mosque lesson delivered by one of the most popular mosque teachers (da'iyat), Hajja Samia, to an audience of 500 women.

Hajja Samia, a woman in her early forties, was well known for her repeated evoca- tions of fear in her weekly lessons and was sometimes criticized by her audience for these evocations. In response, she had the following to say one morning as she

wrapped up her hour-long lesson (dars):

People criticize us for evoking fear in our lessons [durus]. But look around you: do you think ours is a society that is afraid of God? If we were afraid of Him and his fury [qa- har], do you think we would behave in the way we do? We are all humans and com- mit mistakes, and we should ask for forgiveness from Him continually for these. But to commit sins intentionally, as a habit, is what is woeful! Do we feel remorse and cry at this condition of the Islamic community [umma]? No! We do not even know we are in this condition. The last shred of fear in our hearts has been squeezed out by the count- less sins we commit, so that we don't even know the difference between what is per- missible and what is not [haram wa halal. Remember that if we cannot cry out of fear of the fires of hell, then we should certainly cry at the condition of our souls!

These remarks are striking for the ineluctable relationship Hajja Samia draws be- tween the ability to fear God and capacities of moral discernment and action. In this

formulation, the emotion of fear does not serve simply as a motivation for the pursuit of virtue and avoidance of vice; it has an epistemic value-enabling one to know and

distinguish between what is good for oneself and for one's community and what is bad (described in accordance with God's program). Notably, according to Hajja Samia, the repeated act of committing sins intentionally and habitually has the cumu- lative effect such that one becomes the kind of person who has lost the capacity to fear God, which, in turn, is understood as the ultimate sign of the inability to judge the status of one's moral condition.28 For many Muslims, the ability to fear God is consid- ered one of the critical registers by which one monitors and assesses the progress of the moral self toward virtuosity, and the absence of fear is the marker of an inade-

quately formed self. Hajja Samia, therefore, interprets the incapacity of Egyptian Mus- lims today to feel frightened of the retribution of God to be both the cause and the

consequence of a life lived deliberately without virtue. The various elements in this economy of emotion and action were clarified to me

further by one of the long-time attendees of Hajja Samia's lessons. Umm Amal, a gen- tle woman in her late fifties, had recently retired after having worked as an administra- tor in the Egyptian airline for most of her life. Having raised two children single-hand- edly and through adversity, she had acquired a forgiving and accommodating temperament that seemed to be quite the opposite of Hajja Samia, who was often strict and unrelenting in her criticisms of the impious behavior of Egyptian women. It came as a surprise to me, therefore, when Umm Amal defended Hajja Samia's em-

phasis on fear in her lessons, in particular her evocations of topics such as the tortures of hell and the pain of death. I asked Umm Amal what she meant when she said that she feared God and how she thought it affected her ability to feel close to God. She re- sponded:

I feel fear of God not simply because of threats of hell and torments of the grave [aidhab al-qabr], though these things are also true because God mentions them in the

840

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity

Quran. But for me the real fear of God stems from two things: from the knowledge that He is all powerful [qudratihil, and from the knowledge of the sins that we have com- mitted in our lives and continue to commit without knowing. Imagine God is the Lord of all worlds. And knowing this engenders fear and awe [khashya] in you. This is dif- ferent from fear [al-khaufl that paralyzes you, but it is fear that motivates you to seek His forgiveness and come closer to Him. Because fear that paralyzes you, or makes you feel despondent about His kindness [rahma] is objectionable and reprehensible [madhmum]. But fear that propels you toward Him is commendable and praiseworthy [mahmnidl. So one who fears is not someone who cries all the time but one who re- frains from doing things that make him afraid of punishment.... So yes, when I hear talk about fear [kalam(an al-khaufJ it has an effect on me because it reminds me of the acts of disobedience I have committed unknowingly, given how absorbed I have been in my life with raising my children and working, and makes me want to seek forgive- ness for them. You see if I am not reminded, then I forget, and I become accustomed to making these mistakes and sins. Most of us don't sin intentionally, but we do so with- out knowing. Talk of fear reminds us of this and forces us to change our behaviors [tassarufatina]. But the greatness of my Lord [rabbi] is that He continually forgives us. This causes me to love Him as much as I fear His capacity for greatness.

Umm Amal's answer is remarkable for delineating the topography of fear and love undergirding virtuous action. Notably, these emotions are not simply subjective states but linked to action. Umm Amal, therefore, draws a distinction between fear that results in inaction (considered reprehensible, madmom) and fear that compels one to act virtuously (perceived as desirable or praiseworthy, mahmod). Fear of God in this conception is a cardinal virtue the force of which one must feel subjectively and act on in accord with its dictates.29 She also draws a distinction between ordinary fear (khauf) and fear with reverence or awe (khashya). Khauf is what you feel, as an- other mosque participant put it, when you walk alone into a dark unknown space, but

khashya is what you feel when you confront something or someone whom you regard with respect and veneration, an aspect of God that Umm Amal calls "His omnipo- tence" (qudratihi).30 Yet it is precisely the qualities that inspire khashya in Umm Amal that also inspire her to love God. Thus, in Umm Amal's view, love and fear of God are

integrally related to her ability to recognize God's greatness both in His capacity to

punish, as well as to forgive and sustain His creatures despite their tendency to err. Umm Amal's response also speaks to the roles fear and love play in the habitu-

ation of virtues and vices. Unlike Hajja Samia, she is talking about Muslims who com- mit acts of disobedience (m'asi) out of negligence, rather than conscious intention. Yet even vices committed out of negligence, if done repeatedly, have the same effect as do intentionally committed vices in that once they have acquired the status of hab- its they can come to corrode the requisite will to obey God.3 This logic assumes that

although someone with a pious disposition can err, the repeated practice of erring from God's program results in the sedimentation of this quality in one's character. This accords with the Aristotelian understanding of habitus insomuch as the repeated performance of vices (as well as virtues) results in the formation of a virtueless (or vir- tuous) disposition. Fear of God is the capacity by which one becomes cognizant of this state and begins to correct it. Thus, it is repeated invocations of fear and the econ-

omy of actions following from it that train one to live piously (a spur to action), and are also a permanent condition of the pious self (al-nafs al-muttaqi).

Although the importance of fear to this pedagogical model of ethical formation is clear from the examples above, the question arises how this emotion is acquired and cultivated, especially because the mosque participants do not consider fear of God to be natural but something that has to be learned? According to the women I worked

841

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

american ethnologist

with, there are many avenues that provide training in fear. One is the space of the

mosque lessons. I was surprised to find out that many of the attendees who came to hear Hajja Samia regularly were drawn by her ability to engender fear. When I asked one of these women why she preferred Hajja Samia's severe and strident (mutashad- did) style of delivery, she responded:

We live in a society in which it is hard to remain pious and to be protective of our relig- ion [nihfiz'ala dinnina]. When we hear this kind of talk, it startles us and keeps us from getting lost in the attractions of the world. You see the path to piety [taqwa] is very dif- ficult. Hajja Samia and others are afraid that unless they use [the rhetorical style of] takhwff [to cause to fear], people will lose all the effort they have exerted in getting there. They want people to hold on to their efforts in the path of piety [taqwa] and this is why they use takhwif. 32

Hajja Samia, therefore, did not simply prescribe fear as a necessary condition for

piety, but deployed a discourse and rhetorical style that elicited it as well.33 In doing so, she punctuated her lessons with evocations of the fires of hell, trials of death, and the final encounter with God after death. This style of preaching aimed at the creation of fear in the listeners is termed tarhfb (and at times takhwif), and its antonym targhfb refers to the evocation of love for God in the audience: most mosque teachers stressed the importance of maintaining a fine balance between these two rhetorical strategies. Cassette-recorded sermons that used the takhwif style were also widely popular among the women I worked with because they were perceived to be particularly ef- fective in inducing the emotion of virtuous fear (taqwa) in the listener.34

In addition to these avenues, the ritual act of worship (salat) is a critical space for the inculcation and realization of virtuous fear. Ideally, salat is performed with humil-

ity and submission, a state called khushu', a critical element of which is one's ability to palpably fear God. In this conception, fear is not only a motivation to prayer but also a necessary aspect of its performance, an "adverbial virtue" that imparts to the act of prayer the specific quality through which it becomes consummate. 35 A similar un-

derstanding of fear is implicit in Hajja Samia's remarks above, which indicate that fear of God is constitutive of the faculty of moral discernment, and as such informs and

permeates all pious conduct. In other words, in this economy of discipline virtuous fear is the motivation for, as much as a modality of, action.

Notably, to the extent that fear is understood as a motivation to action it accords with the belief in certain cultural traditions that emotions are causative of action, a view that has been noted and analyzed in considerable detail by some historians and

anthropologists of emotion (James 1997; Lutz and White 1986; Rosaldo 1980). What is significant here, however, is that the emotion of fear not only propels one to act, but is also considered to be integral to action. Thus, fear is an element internal to the very structure of a pious act, and as such it is a condition for (to use J. L. Austin's terms) the felicitous performance of the act.36 In other words, what this understanding draws at- tention to is not so much how particular emotions as modes of action constitute differ- ent kinds of social structure (Abu-Lughod 1986; Good and Good 1988; Myers 1986), but more how particular emotions are constitutive of specific actions, conditions by which those actions attain their excellence.

The way consummate excellence was achieved in one's prayers was a topic of heated discussion among the mosque participants. One of the widely circulated booklets among the mosque groups was entitled "How to Feel Humility and Submis- sion [khusho'] in Prayer?" (Maharib 1991). The booklet provided instruction to women on how to pray with khushua, focusing not only on the act of salat itself but also on the conditioning of one's thoughts and actions before and after its performance.37

842

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity

One of the techniques mentioned in this booklet, and extensively discussed by the mosque participants, is that of weeping during the course of prayer, especially at the time of supplications, as a means for the expression and realization of a fearful and reverential attitude (khashya) toward God. Weeping in this context, however, is not tantamount to crying provoked by the pain of personal sufferings. Instead, it must is- sue forth out of a sense of being overwhelmed by God's greatness and enacted with the intention of pleasing Him. In other words, the act of weeping in prayer is not meant to be cathartic of one's sorrow and grief, a release of stressful emotions gener- ated by the tensions of life that Turner has described in relation to ritual practice in other contexts (Turner 1969; see also Scheff 1977). On the contrary, according to the mosque participants I know, the act of crying in prayer for the sake of venting one's feelings, rather than expressing one's awe for God, renders the ritual null and void (batil). Similarly, Muslim theologians have long considered crying in prayer for the sake of impressing fellow Muslims to be an idolatrous act (shirk). Notably, the empha- sis participants place on the intention with which one performs these emotions com- plicates those anthropological views that suggest that rituals have little to do with the practitioners' intentions or emotions (e.g., Bloch 1975; Tambiah 1985).38 Virtuous fear and weeping are not understood by the mosque participants to be generic emo- tions, nor are they devoid of intentionality-rather, they are specific to the economy of motivation and action of which they are a constitutive part and, in an important sense, impart to a particular action its distinctive quality.39

The ability to cry effortlessly with the right intention did not come easily to most women, however, and had to be cultivated through acts of induced weeping during salat. Booklets of the kind mentioned above suggest different strategies for the attain- ment of this state, and women are advised to try a number of visual, kinesthetic, ver- bal, and behavioral techniques in order to provoke the desired affect (see Maharib 1991). This entailed various exercises of imagination geared to exciting one's emo- tions, evoking the pious tenderness that khusho( entails and that leads to weeping. Ac- cording to the women I know, common exercises included: envisioning that one was being physically held between the hands of God during prayer; visualizing crossing the legendary bridge (al-sarat), narrow as a sharp blade, that all Muslims will be re- quired to walk in the Hereafter but that only the pious will be able to traverse success- fully; or avoiding the fires of hell that lie underneath. Other women would talk about imagining the immensity of God's power and their own insignificance. The principle underlying these exercises is that repeated invocations of weeping, with the right in- tention, habituate fear of God to the point that it infuses all of one's actions, in particu- lar salat. In other words, repeated bodily behavior, with the appropriate intention (however simulated in the beginning), leads to the reorientation of one's motivations, desires, and emotions until they become a part of one's "natural" disposition. Nota-

bly, in this economy of discipline, disparity between one's intention and bodily ges- tures is not interpreted as a disjunction between outward social performance and one's "genuine" inner feelings-rather, it is considered to be a sign of an inadequately formed self that requires further discipline and training to bring the two into harmony in accord with a teleological model of self-formation.

It is tempting to interpret the act of weeping in prayer as obligatory, with none of the spontaneity of ordinary feelings. In other words, Tambiah's remarks seem to cap- ture well what I have described thus far when he says,

ordinary acts "express" attitudes and feelings directly (for example, crying denotes dis- tress in Western society) and "communicate" that information to interacting persons (the person crying wishes to convey to another his feeling of distress). But ritualized,

843

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

american ethnologist

conventionalized, stereotyped behavior is construed in order to express and commu- nicate, and is publicly construed as expressing and communicating certain attitudes congenial to an ongoing institutionalized intercourse.. .. Stereotyped conventions ... code not intentions but 'simulations' of intentions. [1985:132; emphasis added]

However tempting such a reading may seem, I would argue that it would be a mistake to reduce the practice of weeping in prayer to a cross-cultural example of conventionalized behaviors that are assumed to achieve the same goal in all contexts. This is so for two reasons. First, such a view does not give adequate attention to those

performances of conventional behavior that are aimed at the development and forma- tion of the self's spontaneous and effortless expressions. As is clear from the discus- sion above, the pedagogical program among the mosque participants was geared pre- cisely toward making prescribed behavior natural to one's disposition, and one's

virtuosity lay in being able to spontaneously enact its most conventional aspects in a ritual context as much as in ordinary life, thereby making any a priori separation be- tween individual feelings and socially prescribed behavior unfeasible. Similarly, as I have shown above, simulating "proper" intentions, did not (to use Tambiah's words) "code" real intentions but, was a disciplinary act undertaken to bridge the gap be- tween how one "really felt" and how one was "supposed to feel"-thereby making a distinction between simulation and reality rather porous.

Second, the process of inducing fear and weeping in oneself during salat compli- cates the separation Tambiah draws between ordinary and conventional emotions in- sofar as it suggests the disciplinary aspects of the most individualized and unstruc- tured feelings and emotional expressions. As much recent anthropological literature has pointed out, given that emotions are discursively and historically constructed, it is difficult to sustain a meaningful separation between what are called "real individual"

feelings and those that are a part of what Tambiah calls "institutionalized intercourse" (Lutz and Abu-Lughod 1990; Yanagisako and Delaney 1995). Thus, to understand how ritual functions in different discursive contexts of power and subject formation, it is important to interrogate the specific and differential ways in which conventional

performances are linked to emotions or feelings rather than assume that they cohere in a singular and definitive manner.

conclusion

In this exploration of the embodied practices of the mosque movement, I have

analyzed the body not so much as a signifying medium to which different ideological meanings are ascribed, but more as a tool or developable means through which cer- tain kinds of ethical and moral capacities are attained. Rather than focus on the expe- rience of the body, I have explored the process by which an experienced body is pro- duced and an embodied subject is formed. I use the notion of experience in this analysis to refer to the skills and aptitudes acquired through training, practice, and ap- prenticeship to a particular field of study.40 Such an understanding of experience seems to capture well the principle of self-formation that informed the practices of the women I worked with, wherein through the repeated performance of certain acts they attempted to re-orient their volition, desires, emotions, and bodily gestures to accord with norms of pious conduct.

My insistence in this article on exploring differential conceptions of ritual is geared toward problematizing the attribution of essential meaning to the coventional and formal character of ritual. I direct attention to how formality is variously concep- tualized in different discursive traditions and made to articulate with disparate structures

844

This content downloaded from 128.143.23.241 on Sun, 12 Jan 2014 11:46:48 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rehearsed spontaneity

of authority and models of the self. In exploring the role that the ritual act of Muslim

prayer played in the formation of pious selves among the women I worked with, I have suggested that the relationship between conventional behavior and pragmatic action needs to be complicated further than anthropological theories of ritual suggest. I have proposed that the mosque participants' understanding of ritual prayer is best

analyzed as a disciplinary practice that complexly combines pragmatic action (i.e., day-to-day mundane activities) with formal and highly codified behavior. Rather than assume that conventional gestures and behaviors necessarily accomplish the same

goals a priori, I suggest the need for inquiry into the variable relationships that formal conventionalized behavior (such as ritual) articulate with different conceptions of the self under particular regimes of truth, power, and authority.

Finally, insofar as my analysis complicates the distinction between a subject's "true" desires and obligatory social conventions-a distinction critical to liberal no- tions of freedom-it represents a challenge to how progressive or liberal scholars think about politics. The politics that ensues from the assumption of such a disjunc- tion necessarily aims to identify the moments and places where conventional norms