Magus and Alchemist

-

Upload

vilowebsite -

Category

Documents

-

view

249 -

download

0

Transcript of Magus and Alchemist

-

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

1/23

The Smithsonian Institution

The Magus and the Alchemist: John Graham and Jackson PollockAuthor(s): Elizabeth LanghorneReviewed work(s):Source: American Art, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Autumn, 1998), pp. 46-67Published by: The University of Chicago Presson behalf of the Smithsonian American Art MuseumStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109316.

Accessed: 11/12/2012 13:40

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at.http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

The University of Chicago Press, Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Smithsonian Institutionare

collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toAmerican Art.

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpresshttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=smithhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/3109316?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/3109316?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=smithhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

2/23

The

Magus

and the

Alchemist

John

Graham nd

Jackson

ollock

Elizabeth

Langhorne

1

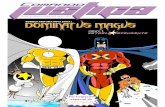

Jackson ollock,Masquedmage,ca.

1938-41.

Oil on

canvas,

101.6

x

61 cm

(40

x 24

1/8

in.).

Collection of

the ModernArt Museum of Fort

Worth,

Museum

purchase

made

possible

by

a

grant

from

the

Burnett

Foundation

In

a

dinner

conversation with

his

close

friend Nicholas

Carone,

in

his last

years,

Jackson

Pollock

(1912-1956)

acknowl-

edged

John

Graham's

(1881-1961)

importance for him. Carone was pressing

Pollock,

"People

understand the

paint-

ing-talk

about the

technique,

the

dripping,

the

splattering,

the automatism

and

all

that,

but

who

really

knows

the

picture,

the

content?...

Well,

who?

Greenberg?"

Pollock

replied,

"No. He

doesn't know what it is

about. There's

only

one man who

really

knows what it's

about-John

Graham."'In recent

years

Clement

Greenberg's

formalist

account

of abstract

art

has

come under

heavy

fire,

but no

new, equally comprehensive

theory

has taken its

place

that

would

account

for the

formation and

importance

of

abstract art

during

and

after

World

War

II. The

encounter

of

Pollock and

Graham

points

toward

just

such

a

theory.

In

"Avant-Garde and Kitsch"

and

"Towards

a

Newer

Laocoon,"

Greenberg

asserted that

in

a

decaying

modern

culture that is

no

longer

able to

justify

the

inevitability

of

its

particular

forms

and

where kitsch is

rampant,

the

best contem-

porary, plastic

art is

abstract: "The

history

of

avant-garde painting

is that of a

progressive

surrender to the resistance

of

its

medium;

which

resistance consists

chiefly

in the flat

picture plane's

denial of

efforts to 'hole

through'

it for realistic

perspectival

pace."

Thus

Greenberg

came

to

appreciate

Pollock's ole in

tackling

he

problem

aced

by

the

young

American

painters-how

"to oosen

up

the rather trictlydemarcatedllusion of

shallow

depth"

n

late

synthetic

cubism

and

recapture

he tensions

between

flatness

and illusionism

o

fundamental

to

the best

of modernist

painting.2

And

yet,

even as artist

and critichad a lot to

offerone

another-Greenberg

lending

Pollocka

knowingeye,

encouragement,

and critical

acclaim;

Pollock

offering

Greenberg

onfirmation

nd advance-

ment of his

aesthetic

heories-their basic

concerns

were

very

different.

An

artist or

whomtheevolutionof form was inti-

mately

bound

up

with the

evolution

of

symbols

n

theserviceof lifewas

being

used

by

a criticto advance

a

master

narrative f art forart's ake.

This differencen

sensibility

was

already

lear

n

Greenberg's ebruary

1947

reviewof exhibitions

by

Pollock

and

Jean

Dubuffet.

Asserting

hat

Pollock,

as a masterof

"recreated

lat-

ness,"

was the

equal

of the

great

Euro-

pean painter

Dubuffet,

Greenberg

referred o what

variousartists

made

of

Paul Klee'sall-over

scratchings

nto the

material urfaceof a

painting:

Where he

Americans

mean

mysticism,

Dubuffet

means

matter,

material,

ensation,

47

American rt

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

3/23

Ir

V's

NNW

bid

or

-

?40i-

jo,

?rk

v

v'r

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

4/23

the all too

empirical

and immediateworld-

and the

refusal

o be taken in

byanything

coming rom

outside

t.

Dubuffet's

mono-

chromemeans

a

state

ofmind,

not a secret

insight

into

the

absolute;

his

positivism

accounts

for

the

superior

argeness f

his

art.

Greenberg

was

right

about American

painters'

interest in

the

spiritual

dimen-

sion of

art. Even

in

the late

1930s

and

early

1940s

they

were

practicing

what

Stephen

Polcari

has

called

their

versions

of T. S. Eliot's

"mythic

method,"

fusing

aspects

of

anthropology, comparative

mythology,

and

depth psychology

in

an

attempt

to discover

meaning

in

the face

of war

and to

express

such

meaning

in

an

abstract and automatist

art.3

Pollock, too,

shared such

concerns,

but not

the

positivism

Greenberg

ad-

mired. The veryforms thatso fascinated

Greenberg

n Pollock's work were in fact

the

products

of a

spiritual

quest

of

just

the sort

Greenberg

dismissed. In a

December

1947

review of the work of

Adolph

Gottlieb,

whom

Greenberg

saw

as "the

leading

exponent

of

a

new

indig-

enous

school of

symbolism"

that included

Mark

Rothko,

Clyfford

Still,

and Barnett

Newman,

he wrote:

"I

myself

would

question

the

importance

this school

attributes to the

symbolical

or 'meta-

physical' content of its art; there is

something

half-baked and

revivalist,

in

a

familiar American

way,

about

it."

Given

such

sentiments,

it is not

surprising

that

Pollock

warned Fritz

Bultman,

with

whom he loved to

discuss

just

such issues:

"It'snot

something

you

can discuss with

Greenberg."4

He

was

well

aware

his

understanding

of the task of artwas not

that of his most

supportive

critic.

Through-

out

his

life,

Pollock

believed

the one

person

who

understood

what he was

up

to was Graham.

The two men met no later than the

late fall

of

1940,

when Graham

was

fifty-

three and Pollock

twenty-eight.

By

November

1941,

when

Graham

invited

Pollock to exhibit

at

the

McMillen

Gallery,

Pollock

was

a

frequent

visitor

to

Graham's studio at

54

Greenwich

Avenue,

which

was filled with

his

collec-

tion

of

African,

Oceanic,

and Melanesian

objects,

Renaissance

bronzes,

Greek and

Egyptian

statuettes,

and

an

extensive

collection of mirrors

and

crystal

balls.

To his old

friend Reuben

Kadish,

Pollock

compared

the act of

crossing

Graham's

studio threshold

to

entering

a

temple

or

sanctuary.

Kadish

likened Pollock's

reverence for

Graham to that of a

cult

follower for

his

guru.5

What was it

about

Graham that

so attracted Pollock? Given

his recent

encounter

with

the art of

Picasso,

his

growing

fascination with

primitive

art,

and his

Jungian

psycho-

therapy,

it is

hardly

surprising

that he

should

have

found

in

Graham,

who

shared these interests, a kindred spirit.

Even before he met

him,

Pollock had

come to

appreciate

Graham's

System

and

Dialectics

ofArt

(1937)

and

even

more his

article

"Picasso and Primitive Art." The

latter so

impressed

Pollock that he

quite

uncharacteristically

wrote

Graham a

letter.6

As Pollock

told

Carone,

he

also

went to see

Graham,

because

"he knew

something

about art and I had to know

him. I

knocked

on his

door,

told

him I

had read his article and that

he

knew. He

looked at me a long time, then just said,

'Come

in."7

Graham saw

primitive

artists as the

precursors

of

modern abstraction. Never

seduced

by

the desire to

imitate

or

compete

with

nature,

they always

re-

sponded

to the

"possibilities

of the

plain

operating space,"

or the

two-dimensional

format in

painting.

The

primitive

artist

thus understood what the modern

painter,

coming

from

and

reacting

to a

tradition

informed

by

five

hundred

years

of

working

with

the

rules

of

perspective

that evolved

during

the Renaissance,had

come

to understand anew.

This

under-

standing

permitted

"a

persistent

and

spontaneous

xercise of

design

and

compo-

48

Fall

1998

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

5/23

sition." The

primitive

artist,

Graham

maintained,

worked

"freely

within the

pure

form,

shifting

at

will,

assembling

and

dissembling

the

character-feature

of form."

Graham

tied

the

freedom of

handling

and

the

ambiguity

of

feature found

in

primitive

art to free

access

to the

uncon-

scious,

couching

his

discussion

not in the

To

his

oldfriend

Reuben

Kadish,

Pollock

compared

the act

of

crossing

Graham's tudio

thresh-

old to

entering

a

temple

or

sanc-

tuary.

Kadish

likenedJackson's

reverence

for

Graham

to that

of

a cultfollower for his guru.

ethnographic

terms of how the

art related

to

its creators'

beliefs

in

the

spirit

world,

but

in

the

psychological

terms of

the

Jungian

collective

unconscious,

"the

creative factor and

the

source

and the

storehouse

of

power

and

of

all

knowledge,

past

and future."

Through

the forms

used

in

their

art,

primitive people

"satisfied

their

particular

totemism and exteriorized

their prohibitions (taboos) in order to

understand

them

better,

consequently

to deal with them

successfully."

The

drawings

Pollock

gave

to his

therapist

Dr.

Joseph

Henderson

showed

him

similarly

struggling

with

his

inhibitions, fears,

and

hopes,

while

engaged

in

formal

experimentation.8

Kindred

Spirits

In the

abstractwork of

primitive

artists

Graham was thus

discovering

both a

therapeutic

function and

an

extraordinary

wealth of two-dimensional

forms.

Certainly

Graham's

evocative,

aphoristic

formulations

would

never

have found

their

way

into

a

scholarly

anthropological

volume

on

primitive

art;

even

in

the New

York art world of the

1930s

his

pro-

nouncements,

heavily

laced with

mysti-

cism,

were

considered

extreme.

Neverthe-

less,

his

intuitions

about

the

spontaneous,

metamorphic, expressiveproperties

of

primitive

art

signaled

a new

approach

to

abstraction

and to

the

art

of

Picasso,

whom Graham

thought

the

paradigmatic

modern

artist:

"No

artist

ever

had

greater

vision or

insight

into

the

origin

of

plastic

forms

and

their

logical

destination

than

Picasso

....

Picasso's

painting

has

the

same ease

of

access to the

unconscious

as

have

primitive artists-plus

a conscious

intelligence."

Graham

pointed

not to Les

Demoiselles

dAvignon

(1907),

where the

influence

of

African

sculpture

is

obvious,

but rather to works from 1927 or later,

most

particularly

those from

1930

to

1933.

Characteristic of

these

primitive

art forms is the

interchangeability

and

conflation of different members of the

human

body,

and

it is this

physical

fluidity

that Graham dramatized

in

his

caption describing

an Eskimo

mask

he

had chosen as the

frontispiece

for his

article:

"There

is

typical primitive

insis-

tence

that

nostril and

eye

are of the same

origin

and

purpose.

Two similar orifices

seem to say: two eyes and two nostrils."

About

Picasso's work he

was less

specific.

Phrases such

as

"[Picasso is]

painting

women

in

interlocking figures

of

eight,"

evoke the artist's

use

of

a free metamor-

phic

line

to

depict

different anatomical

parts.

More

suggestive

was Graham's

choice of

illustrations,

among

them that

masterpiece

of

Picasso's transformative

imagination,

Girl

before

a

Mirror

(fig.

2).

This

image probably provoked

an

immediate and visceral

response

in

Pollock-the

first

explicit

evidence of

that connection was

Masqued

Image

(fig. 1).9

Pollock's instinctive

grasp

of

Picasso's

mastery

was

certainly

supported

by

the

conviction with which

Graham

49

American Art

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

6/23

nw,

i7l

AIL:

AWAOM

MINIMUM

O W

lo

2

Pablo

Picasso,

Girl

before

a

Mirror,

1932.

Oil on

canvas,

162.3

x

130.2

cm

(64

x

51

?

in.).

Museum

of

Modern

Art,

New

York,

Gift

of

Mrs. Simon

Guggenheim

spoke up

for Picassoandabstract rt

n

the

1930s.

Graham's

words

nspired

many

of the artistswho would later

become

abstract

xpressionists,

ncluding

Pollock.

But what attracted

Pollock

to Graham

more

than the latter's

proselytizing

or

modernistart and

Picassowas

their

mutual

understanding

f

the

significance

of an

art

that,

while

articulated

n

terms

of

modern

psychoanalysis,

wed

more

to

the

sort of esoteric deas

Greenberg

o

disliked.Pollockhad firstbeenintro-

duced to such ideas

n

high

school

by

his

art

teacher,

Frederic

ohn

de

St. Vrain

Schwankovsky,

ho not

only

instilled

in his students

an

appreciation

for

Matisse,

but

also

introduced

them to

Rosicrucianism, Hinduism, Buddhism,

yoga,

reincarnation,

and

karma-all

in

order

to

teach

them

"how

to

expand

their

consciousnesses,"

to meet them-

selves.10

t was a lesson not lost on

Pollock

and

one

significantly

reinforced

by

his

therapist,

who shared the

Jungian

conviction

in

the

healing

power

of

images.

To

Graham,

too,

the

quest

for self

mattered more than the abstract

play

of

forms.

But

this

did

not mean that he had

abandoned the

attempt

to make

painting

serve

his

quest.

By

1943,

Graham

had,

in

his own

painting

and

in

his

pronounce-

ments,

denied Picasso

(he

erased

his

name

from

System

nd Dialectics

ofArt)

and

turned back to the Renaissance. He still

believed in the artistas visionary and

diviner;

but no

longer

convinced that

wisdom could be

brought

forth from the

immemorial

past

through

the

evolution

of

form,

he

turned to

symbolic

images

as

a

"secret,

sacred

language.

.

. in

adora-

tion, evocation,

conjuration

of this

world's forces or

spirits."

The

psychologi-

cal and

the

formal

gave

way

to the

overtly

mystical

and the

symbolic.

While in

1937

Graham

could claim

that "culture

as

a

process

is the

evolution

of

form,"

he

would

later state that the

"true attraction

of

any

art

is

its

symbolical

language....

The

successive evolution of

symbols

constitutes

the

culture of a

nation.'11

Such Hermetism

made

its

appearance

in Graham's work

well before

1943,

in

such a fashion

in

Sun and Bird

(fig.

3)

as to

suggest,

if

not

an

influence on

Pollock's

growing

symbolic

awareness in

Bird

(fig.

4)

and

Magic

Mirror

(see

fig.

10),

at

least shared interests.

Constance

Graham remembers that

the

two

went

together

to the Museum of Modern

Art's

exhibition Indian Art

of

the United

States.12

Pollock's

Bird

and Graham's Sun

and

Bird

not

only

date

from that

time,

but

also are

strikingly

similar

in their

50

Fall

1998

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

7/23

?f

t

3

John

Graham,

Sun and

Bird,

ca.

1941-42.

Oil on

canvas,

53.3

x

45.7

cm

(21

x 18

in.).

Private

collection

4

Jackson

Pollock,

Bird,

1941.

Oil

and sand

on

canvas,

70.5

x 61.6 cm

(27

3

x

24

1

in.).

Museum

of

Modern

Art,

New

York,

Gift of

Lee

Krasner n memoryof Jackson

Pollock

overall

hieratic,

ymmetrical

omposition,

their

differentiation

etween

darkness

and

light,

and the

presence

of a

bird

with

outstretched

wings.

In

the

Graham,

he

more

mmediately

videntbird s flanked

by

a

sun disk on the left

and

a

crescent

moon on the

right.

These formsreflect

Graham'sincreasinglysoteric nterests-

theosophy,

hatha

yoga,

tantric

yoga,

numerology,

ystems

of

proportion

derived

rom

Pythagorean

nd Platonic

sources,

alchemy,

and

astrology.13

Sun

and Bird

especially onveys

Graham's

preoccupation

with the

last

two.

The

likely

source or its

imagery

was

an

illustration

n

PierreMabille'sarticle

"Notessur e

symbolisme"

n

the

1936

issue of Minotaure.

A

birdwith

outspread

wings

is enclosed

n

a

triangle,

which

hangs

on a

central

axis,

a crescentmoon

and

a

blazing

un

appear

beneath he

lower

points

of the

triangle fig.

5).

14

Mabille'sarticle

pointed

out the

magical

efficacy

of

the

symbolic

mage,

both for

the

ancients,

who

used

them

in

their

Hermetic exts

and

in

religious

and

initiatory

eremonies,

nd for the modern

painter.

His

illustrations,

hough

uniden-

tified and

unexplained,

derive rom

Hermetic

exts

on

alchemy.

The HermeticTradition

The Hermetic

radition,

which

traced

its

origin

backto the

mythical

Egyptian

Hermes

Trismegistus

nd couched ts

teachings

under

he veil of

enigma,

allegory

and

symbols,

had declinedwith

the

rise

of

scienceand the

triumph

of the

Enlightenment.

Partly

due

to the

work of

Eliphas

Levi,

t revived

n

intellectual nd

artistic ircles

n

late-nineteenth-century

France

and

especially

nfluenced

ymbol-

ist andthensurrealist rt.

Holding

to a

universe

n

which

every

being

possessed

a

spirit

and

the

macrocosm

orresponded

to

the

microcosm,

Hermetic

hought

51

American

rt

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

8/23

5

Unidentified

artist,

alchemical

image,

published

n Minotaure

vol.

2,

no.

8

(1936):

2

. . .

. .

....

attempted

o discover he hidden aws

that ruled

the

universe

and

thereby

o

accomplish

what is

called

he Great

Work-the realization

f

spirit

n

matter.15

The alchemist'sGreatWorkthus

focused

on

matter,

pecifically

ase

metals.The

usualgoal

was

to transform

lead

into

gold.

On one level this effort

was a

protochemistry;

n

another,

n

accordwith old belief

n

the

spiritual

significance

f

matter,

he

effort

at

transformation as

directednot

just

toward he

material

without,

but toward

the

soul,

within. As leadis transmuted

into

gold,

so

the soul can be

purified,

dissolved,

and

crystallized

new,

to reveal

spirit.

Alchemy

hus

offered he modern

painter

a

metaphor

lluminating

his or

her

own work.

Alchemy's

ymbols

provided

he artistwith a new

subject

matter-i.e.,

allegorical

igns referring

o

self transformation. aken as a

magical

operation,

he

manipulation

f

symbols

might

not

simply

refer

o

but

actually

constitute

uch

a

spiritual

process.

The

manipulation

f

pigment

n

the

act of

painting

might

be

understood,

ike the

alchemist's

ransformation

f base ead

into

gold,

as a

process

of

meaningful

elf-

transformation.

or artists

who took the

premises

of

alchemy

eriously,

t could

becomeavehiclefor

investing piritual

and

emotional

meaning

n

the

act

of

painting-whether

painting

symbols

or

manipulating

aw

pigment.

Graham's

nderstanding

f the

magical

powers

of art

was

bound

up

with

his involvement

with

alchemy.

n

Sun

and

Bird,

a birdhoversover

an

oval

egg

shape.

In

alchemy

he

egg

stands

or

prima

materia

containing

he

captive

soul,

the chaos

apprehended

nside

the

alchemist's

etort."6

unand

moon

signify

the underlyingdivisionof all existence

into

opposite

principles-whether day-

night,

male-female,

pirit-matter,

ctive-

passive,

ixed-changing-that

stimulate

the eternal

vital

current.

n

astrology,

sisterscienceof

alchemy,

he zodiacal

sign

Capricorn

marks he

beginning

of

the

process

of

dissolution,

here associated

with

the

changing

moon,

while

Pisces,

placed

on the face

of

the

sun,

denotes

a

final

moment,

an

end that

simultaneously

contains

he

beginning

of

the new

cycle.

Thus

Graham's

lacement

of zodiacal

signs

reiterateshe

dynamic

between

opposites-solve

et

coagula,

issolveand

reconstitute.

The

eagle

or

phoenix

also

speaks

of

periodic

death

and

rebirth;

n

alchemy

t

symbolizes

he liberated

oul.

Here

the

bird

s

shown

rising

rom

the

egg,

the

prima

materia.

Traditionally

consecrated

o the

sun,

the

phoenix

speaks

of

eternal

ife within continual

death.

Perhaps

to

emphasize

this

connection,

Graham

itled his

painting

Sun

and

Bird.

Astrological

signs frequently comple-

ment alchemical

images, following

a law

of Hermetic wisdom

that "whatever s

below is like that which is above." Saturn

corresponds

o

lead,

the materia hat is

52

Fall

1998

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

9/23

A

lii

ii ?

6

John

Graham,

Untitled

("Litera-

ture

of

the

Future"),

a.

1940.

Drawing,

29.2

x

20.3

(11

1/2

x

8

in.).

Private ollection

the basis of the alchemist's

art;

Jupiter

corresponds

to

tin,

a

light

metal,

the first

manifestation

of

spirit

in the

alchemical

work.17In Sun and

Bird,

the

astrological

signs

for

the

planets

on

either

side of the

bird's head-Saturn

on the left

and

Jupiter

on the

right-reiterate

the nature

of the alchemical

work,

and

represent

the

"rulers"

of

the zodiacal

signs

below. Thus

Graham reiteratesthe central alchemical

themeof the

painting-the

play

of

opposites

and

the transformation f

matter

o a

higher,

more

spiritual

evel.

Self-Transformation

Biographical

etailsconfirm

hat

the

alchemical-astrological

ymbolism

n Sun

and

Bird

does indeed

refer o and delin-

eate

Graham's

rocess

of

personal

elf-

transformation.Graham

was

born in

Kiev

on 8 or

9

January

1887

(by

the

Gregorian

calendar)

under

he

sign

of

Capricorn.

He

describeshis motheras "a

sorceress,

r a

witch..,

immersed

n

occult

knowledge,"

who

retrievedGraham

as an infant

from

a

rockwhere

an

eagle

had lefthim

during

a

"night

of

apocalypse"

nd "deluvian

outpour....

The

eagle,

aftera few

circles,

went straightup.... My mother,whenI

grew

up

...

explained

hat

I

was the son

of

Jupiter

and a

mortalwoman

and that

is

why

He hadto send me to live with the

human

beings,though

I was not

alto-

gether

human.'8

Graham

thought

of

himself "more ike a sacred

androgyne,

the

missing

ink

between he swine nature

and

the

human

nature."'19

ith

such tales

Graham laborated

personal

myth,

and

used elementsof that

myth

in

Sun and

Bird

o recordand continue

his

own

work

of self-transformation.

The

theme of birth

refers

not

just

to

Graham's

ebirthas

an

adept

n

the

Hermetic

radition,

but

veryprobably

to

his

reentry

nto artas

well.

Although

Grahamhad

developed

his

reputation

s

a

painter

both

in

Parisand New York

n

the

late

1920s

and

early

1930s,

he had

stoppedpainting

n

1933,

though

he

continued

his

activities

as

collector,

connoisseur,

and vocal advocate of

modernist

painting.

Only

around

1939

did

he

start

to

paint

again.

In an

untitled

drawing

(fig.

6),

he

diagrams

his under-

standing

of

art

using

the

"philosophical

geometry"

of

alchemy,

the

circle,

the

triangle,

and the

square.20

The circle that

53

American rt

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

10/23

7

John

Graham,

ird

Watcher,

1941.

Oil

on

canvas,

64.2 x

51.4

cm

(25

?

x

20 ?

in.).

Indiana

University

Art Museum

dominates the

composition corresponds

to

prima

materia,

primordial

matter,

but

the additional

sunrays

make

this circle a

symbol

of

the creative

light,

the

spiritual

agent.

The circle

is

penetrated

by

a

downward

pointing triangle,with

ART

written

large

at its

top

and horizontal

lines

crossing

its bottom

tip.

In

different

positions

the

triangle

symbolizes

the four

elements of

material existence: downward

pointing

and crossed

by

a

horizontal

axis,

as shown

here,

it

signifies

earth-that

is,

matter

in

its solid form.

The

square

in

the

bottom

tip

of the

triangle

is a

further

signification

of

matter,

experienced

by

the five

senses,

as indicated

by

the

number five. Art for Graham would

appear

to be the concretization of the

interpenetration

of

spirit

and matter.

In

alchemy

primordial light

or

spirit,

when

54

Fall

1998

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

11/23

:

8

John

Graham,

Untitled

(From

White to

Red),

n.d. Colored

pencil,

ballpointpen, felt-tippedpen,

crayon,

and

pencil

on manila

older,

29.8

x

22.5

cm

(11

3?x

8

7/8in.).

Museum

of

Modern

Art,

New York.

Gift

of PatriciaF. Graham

n

memory

of her

husband,

John

David

Grahamand his

brother,

Nicholas G.

W. Thorne

intercepted

by

a material surfacethat then

reflects and individualizes

it,

is referred

to

as a

"ray."Probably

Graham referred

to

this materialized

spirit

when he said there

is "no new

way

to

paint..,.

except

with

some kind

of

ray."21

Sun and

Bird

elaborates Graham's concern with the

interception

of

spirit by

matter. It is not

surprising,

therefore,

that as Pollock

struggled

to

find

himself

through

art,

he should have

recognized

Graham as

an artist who "knew."

John

Graham

was

by

no means

the

only

one to

propose

a

spiritual

dimension

for art and artist.

An

undercurrent

in

surrealist

circles,

this

view received one

of

its

most

explicit

expressions

in

Transition,

a review

published

in

Paris

between

1932

and

1938

that Graham

regularly brought

back to

show

his

artist

friends.22

n

1935

the

editor

Eugene

Jolas

had called

for a

new

kind of creator

who

redevelops

n

himself

ncientand mutilated

sensibilitieshathavean

analogy

with those

used n the

mythological-magical

nside

of

thought

n the

primitive

man,

with

pro-

phetic

revelations,

ith

orphicmysteries,

with

mystictheology,

.. with the attitudes

of

the

early

omantics,

ith the mental

habits till extant n

folklore

nd

fairy

tales,

with

clairvoyances,

ay

and

night

dream-

ing,evenwith subhuman rpsychotic

thinking.23

In

Vertical,

published

in

the United States

in

1941

as a

sequel

to

Transition,

Jolas

called

for

a reconstitution of

"the

myth

of continuous ascent as

being

the

myth

underlying

man's ceaseless

aspirations

towards

the

liberation of the soul." He

cites the

myths

of

Icarus and

Daedalus,

Pegasus,

Nike, Christ,

and

the

winged

horse

of the Norsemen

as

versions

of this

myth. Sun and Bird could be viewed as

Graham's variation

on this

theme,

cast

by

him

in

distinctly

alchemical

and

astrological

terms.

Other

such variations

by

Pollock

include

Bird,

Naked

Man,

and

Birth,

which owe more to his

longstanding

interest

in

the

spiritual

significance

of

American Indian

art

and are

responses

to

the challenges posed

by the Mexican

muralists and

by

Picasso. Graham chose

to include

Birth in

the exhibition Ameri-

can and French

Painting

that was held at

the McMillen

Gallery

from

January

to

February

of

1942.24

In these works

Pollock,

no doubt indebted

to

Graham,

began

to

work

out

a

mystic spiritual

identity

for

himself. Whether Pollock's

55

American

rt

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

12/23

Birdor Graham's

Sunand

Birdwas

executed

first s

unknown;

nor

is it

relevant.

What does

matter are the

shared

interests

of the two

artists,

which

find

striking

expression

in

two other

canvases

by

Graham,

Bird Watcher

(fig.

7)

and

Untitled

(1942).

While in

Sun

and Bird

Graham

had

depicted

the

adept's

Great

Work,

these

paintings

speak

to

its central

and

final

achievement:

the union

of

a

heightened

masculine

spirituality

with a

purified

feminine

matter,

the

masculine-feminine

androgyne,

symbolized

by

the

"conjunc-

tion"

of

sun

and

moon,

Sulphur

and

Quicksilver,

or

King

and

Queen.

To

express

this union

Graham

paints

the

female

principle

in Bird

Watcher

with

a central

diamond

eye,

the

diamond

a

traditional

alchemical

image

signifying

the philosopher's stone, or the union of

matter

and

spirit:

spiritualized

matter.

Graham's

involvement

with

the

mystical

diamond

can

be

traced

back to the

sole

remnant

of

his

autobiography,

From

W

to R

(From

White o

Red) ca.

1936).

The

frontispiece

shows,

in

addition

to the

central

sun marked

by

a

large

number

four,

a

prominent

diamond motif

(fig.

8).

Marked

by

the

letter

G,

it

echoes

Graham's

name

lettered next

to it

and

associates the

diamond

with

Graham's

own

person.

The

diamond's

horizontal

axis

extends to

the

left,

toward

the

head

of the

man,

and

to the

right,

toward

another

man's lower

back,

pointing

at

the two

polar

principles

of

mind and

body

that

Graham

wished to

reunite.25

To

return

to

Graham's

Bird

Watcher:

as

striking

as

her

diamond

eye

is

the

fact

that she

is a Picassoid

woman,

done

in

a

late

synthetic

cubist

style

and kin

to

Picasso's

1937

and

1938

female

images

as

represented

here

by

Seated

Woman

(fig.

9).

Graham

applies

his

understand-

ing

of

pictorial

alchemy

to Picasso's

imagery

of

the

1930s.

It

seems

likely

that it

was

Graham,

who,

as

early

as

1941,

helped

shape

Pollock's

response

to

Girl

before

Mirror n termsof

spirit-matter,

evident

n

Magic

Mirror,

nd

who

in

1942

was

to stimulate

Pollock's

ncreas-

inglymystical

andalchemical

pproach

o

Picasso's

muse,

evident n Moon

Woman

(1942)

and Male

and

Female

1942).26

Magic

Mirror

fig.

10)

is alsoa

re-

sponse

and

a

challenge

o

Picasso

even

asit

begins

to

illuminate

a

path beyond

him.

On firstview

Magic

Mirror

ffers

an

all-over

ield of

shimmering,

pales-

cent,

white

paint

n

which

scattered

ines,

red,

black,

and

yellow

are

placed

on

the

surface

or

buried

n

the

white;

variously

straight

or

curved,

heir

placement

creates

a

gentle

balance

between

stasis

and

movement.

The

only

image

that

stands

out is

the

winged phallus

at

the

top

of

the

central

vertical

axis.Pollock

addresses

his

potent symbol

to a

Picassoid

woman

(the

titlesuggestsGirlbefore Mirror)whose

outlines

shimmer

ust

behind or

beneath

thefield of

animated

paint.27

The

juxtaposition,

o

striking

once

observed,

of

phallus

and

female

mage

beneath,

echoes

Untitled

CR

555)

(fig.

11),

the

drawing

n

which

Pollock

first

clearly

proposed

he union

of male

and

female

opposites

as

the

way

to

articulate

the

dimensions

of a fuller

self. In

that

work

a

strong,

hree-dimensionally

modeled

phallicentity

extends

a

pair

of

hands,piteously, owarda skeletal,

weakly

defined

emale

orso,

flanked

by

a

bulland

a horse.

In

Magic

Mirror

he

skeletal

emale

s

replacedby

the

image

of

Picasso's

ertile

muse,

whom

the

winged

phallus

addresses

ot

directly,

but

through

he veilof

thewhite

paint

that

covers

her. This

constitutes

Pollock's

irst

full-scale

projection

of this theme

onto

the

two-dimensional

surface

of

the

canvas.

New

is the assertion

of the

third

dimension,

a

literalized

concrete

third

dimension

created

by

the

layering

of

female

image,

white

paint,

and

topmost

linear definition

of the

winged phallus.28

Pollock would

seem

to

equate

Picasso's

muse with

the thick,

crusty

surface

56 Fall

1998

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

13/23

1

9

Pablo

Picasso,

Seated

Woman

(Dora),

1938.

Pen

and

ink,

gouache,

and colored chalk

on

paper,

76.5

x

56

cm

(30

'/8

x 22

in.).

Foundation

Beyeler,

Riehen/Basel

that characterizes

Girl

before

a

Mirror

and

many

of Picasso's

late

synthetic

cubist

paintings.

Picasso's

perceptual

probing

of

exter-

nal concrete

reality

in

analytic

cubism

ultimately

had led

to an acute awareness

of

the abstract

nature of

lines,

planes,

tonal

values,

and

finally

colors, textures,

and other

literal material

elements

that

go

into the

making

of an artistic

image.

The

Renaissance-based,

still illusionistic three-

dimensional

pictorial

space

of

analytic

cubism,

which had

become

increasingly

shallow

during

he course

of

early

cubist

experimentation,

ave

way

around

1912

to

a

radically

ew kind

of

pictorial

pace:

an

emphatically

material nd

two-

dimensional

urface.

On

this surface

Picasso

chose not to

push

on to

nonob-

jective

abstraction,

ut instead

o

synthe-

size

abstract

ictorial

lements

with

renewed eferenceso external

eality:

synthetic

cubism.

And after

1925

he

allowed

his references o

external

eality

to

be suffused

with a

new,

surrealist-

inspired

eleaseof

feelings,

magination,

and eroticism.

n

many

ways

Pollock's

art of the

early

1940s

presupposes

his

heightened

awareness

f the

abstract,

material

means

of

art,

so

evident

n

a

work such

as Girl

before

Mirror.

Pollock

proposed

o animate

he thick

paint

of late

synthetic

cubism,

or,

in

termsof his personalandartisticquest,

to

bring

to bear

his new male

potency

on

the

material

spect

of Picasso's

muse,

by

threading

he

movementof

linear

mpulse

through

he field

of thick

paint.

Pollock

here reclaims

he

masculinity

hat at

age

twenty

he had

associatedwith

sculpture.29

Now,

almosta decade

ater,

he asserted

command

of the three-dimensional

materiality

f

paint

with an

explicitly

male confidence.

n

a

transposed

me-

dium,

he was

beginning

o

make

good

on

the artisticambitions

tatedearlier

to his father: hat

he needednot

merely

to

subdue

matter

"with he aid of

a

jack

hammer,"

ut

to

engage

t

in

a kind

of

dialogue.

The

thoughts

and

feelings

ymbolized

by

the

winged

phallus

ind

expression

n

a linear

mpulse,

hose

symbolized

by

the

femalemuse

in

the

material ield of

thick

paint.

To

support

this more abstract

play

of

line

and

paint,

Pollock relies on

his

new command of

the vertical and

literally

three-dimensional

axial structure

of a

canvas. In the lower half of

Magic

Mirror,

echoing

the

alignment

of

the

phallus,

thick black

lines on

the

painting's

topmost layer

establish a

predominant

57

American rt

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

14/23

10

Jackson

Pollock,

Magic

Mirror,

1941. Oil,

granular

iller,

and

glass

on

canvas,

116.8 x

81.3

cm

(46

x

32

in.).

Menil

Collection,

Houston

'14

Li

jr

i1

it.

to?

NZ

-r7V

4F

......

..........

-1,Q

i'N

.

...

V;

tM

la 4..r

I

i

.

...

...

vi

FA

45

V.,

downwardhruston a

diagonal

romleft

to

right.

These

lines

suggest

an arm

and

hand

that

grasp

he

grainy,

andy

paint.

Around

a

striking

red

dot

of

paint,

three-quartershewayup the centralaxis,

a

rotating

pattern

of

red and

black ines

swings

irst

down,

then

around,

up,

and

to the

right,

wherea fetal

configuration

58

Fall

1998

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

15/23

11

Jackson

ollock,

Untitled

CR

555),

ca.

1939-40.

Crayon

and

colored

pencil

on

gray

paper,

31

x

47.6

cm

(12

?

x

18

3

in.).

Collection of

Phyllis

and David

Adelson,

Brookline,

Massachusetts

I

floats,

sketched

in

largely

yellow

lines.30

In

future

works Pollock

would

be able

to

project

his schematic orchestration

of

movement,

not

just

into lines

animating

varying

densities of

paint,

but into the

linear

pulses

of

poured paint.

Magic

Mirror is

the

seed

of the

animated

materiality

and

underlying

structure

of

the

poured

paintings

of

1947-50.

While

in

Masqued Image

and

Magic

Mirror

Pollock offers sketchy representationsof

a

yellow

fetus,

in the latter he offers far

more: the

fetus

of his future

art.

"Foetus,

ancestor

of

all

forms

and

beasts at one

and the same

time,

like

a

rosebud holds

in

itself threat

of all

potentialities

dor-

mant but

potent."31

Because

paint

mattered

more to

Pollock than

mere

words

or

explicit

symbolism,

he was able to incarnate

spirit

in matter

in

a

way

that eluded his intel-

lectual

guru.

What

prevented

Graham

from

mastering

the kind

of

pictorial

alchemy

he

gestured

toward is shown

by

his

Untitled

(fig.

12),

an

explicitly

Hermetic and

symbolic

version of Girl

before

a

Mirror,

radically

different

from

the terms of

appreciation

put

forward

in

the

1937

article "Primitive Art and

Picasso."

If he

had

spoken

there of the

spontaneous play

of

metamorphic

form

on the two-dimensional

surface,

Graham

now

gives

the

contemplating

woman an

eye

surrounded

by

a

downward

pointing

triangle,

reminiscent of the

alchemical

geometry

that

symbolized

his understand-

ing

of art as an

interpenetration

of

matter

and spirit n the untitleddrawingdiscussed

above. Graham reiterates this

understand-

ing

in

the mirror-canvasat which the

woman

gazes:

a

phallus

hovers over the

feminine vase. Picasso also

implies

such

sexual

association

in

his canvases of the

1930s.

By

making

the

androgynous

puns

within Picasso's

images explicit,

Graham

once

again

defines art as

the

interpenetra-

tion of

opposites

projected

in

sexual

terms,

a definition that

would

also seem

to

have

influenced Pollock's

Magic

Mirror. Pollock's

winged

phallus

hovering

at the

top

of the

painting

over the female

body

is

in

tune

with the

sexual terms

of

Graham's

Hermetic version of the Picasso

canvas. And

the

proposal

in

Magic

Mirror

59

American

rt

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

16/23

12

John

Graham,

Untitled

(Artist

Sweating

Blood),

ca.

1942-43.

Oil

on

canvas,

76.8

x

61 cm

(29

?

x

23

1/2

n.).

Privatecollection

to enliven

a femalematerial

urface

with

a male

inear

mpulse,

o central

o Pollock's

art,

s

in

tune

with

Graham's nderstand-

ing

of art as an

interpenetration

f

spirit

and

matter.32

Graham

had

long-standing

deasabout

how this

might

be

accomplished

t

an

abstract evel.

In

Untitled,

we

find

him

poised

at

the

threshold

hat

separates

is

newer

convictions

about the

importance

of

symbols

and his older convictions

aboutthe

spiritual

potentialof the

abstractmaterial f

paint,

which linked

him

to the tradition

n

modern

art of

content

in

abstraction.

Like

Malevich

in his

1916

and

1919

manifestoes n

"Suprematism,"

n

System

nd Dialectics

ofArt

Grahamhad

equated upreme

feeling

n

art

with

abstraction.

Like

Kandinsky,

e

had believed

n

the

soul's

quest

for

formalembodiment

n

a work

of

art. Not

only

did he

talk of

the

power

of

abstract

rt,

but

throughout

he

1920s

and 1930s

attempted

o

practice

t in his

own

mode

of

abstract

painting,

which he

calledminimalism:"Minimalisms the

reducing

of

painting

o

the minimum

ingredients

or

the sakeof

discovering

the

ultimate,

ogical

destinationof

painting

n

the

process

of

abstracting.

Painting

tartswith a

virgin,

uniform

canvasand

if

one worksad infinitum t

reverts

again

to a

plain

uniformsurface

(dark

n

color),

but enriched

by

process

and

by experiences

ived

through.

Founder:

Graham."Given his commitment o

abstraction,

Graham

ould call

painting

"essentially

modernart because ts

basic

element-SPACE-was first

consciously

used

only

in

the most recent

imes,

since

the

Impressionists."33

e

specifies,"Space

has

these

aspects:

)

extension

or

continu-

ity;

b)

plane

as

a

specific

extension,

.e.,

a

two-dimensional

xtension;

)

matteror

a

multipliedplane;

d)

form or matter

precipitated

nd

specified;

)

volume or

an

optical

delusionbased

on the

phenom-

enon of

binocularity

r

a

sight

from

two

points

with an

arbitrary

ifference;

)

energy

or matter

n

discharge

r

liquida-

tion." He

dismisses he illusion of

space,

emphasizing

nstead he role of the

subject."Subjectively

onsidered,

orm s

an

ability

o

mould

space

n

definite

and

final

shapes

hat function

together

n

concert.

Subjectively

form is an

ability

to

command,

to

imprison

space

in

signifi-

cant

units,

it is an

ability

to control

the stream of

energy

in

regard

to

space ....

Pure form

in

space speaks

of

great psychological

dramasmore

poignantly

than

psychological

art can

ever

do."

Here Graham

presents

an

energy-based metaphor

for the role of

60 Fall

1998

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

17/23

13

John

Graham, Studio,

1941.

Oil

on

canvas,

61 x

76.2

cm

(24

x

30

in.).

Private

ollection

oil$

4W,

.;wK

31L

Ar

CA

A

old

MO=

pk?

Alk

V4

6

the

psyche

in

art that

Pollock

by

1941

was

already

beginning

to realize in

his increas-

ingly

abstract

art.34

Graham

credits Picasso with

such

a

mastery

of

pictorial space,

but

not

with a

final

push

into the realm of

pure

form.

In

his

private

Journal

of

1944-46,

Graham wrote: "The painting-a fin-

ished

one-presupposes

two

stages:

1)

first

you try

to

brake

[sic]

the whole

space

into

drastic

shapes,

design

it

evocatively,

organically

and

this is a

hard,

long

and

strainuous

[sic]

process

in

itself

(Picasso

does not

go

beyond

this

stage)

and

2)

second,

the

hardest task is to

forget

about

all

you

have

accomplished.

. .

reform like

a

general

after a battle

your

regiments,

your

forces and attack over from an

entirely

different

point

of view or

angle."

The

second

stage

would seem to be the

more

thoroughly

abstract,

the effort to

go

for

something

more

supreme,

more

nonobjective.

"A

painting

is a

self-

sufficient

phenomenon

and does not

have to

rely

upon

nature. Artist

[sic]

uses

nature

in

much the same

way

as aviator

does-he uses

flying

field to start

the

flight

but once startedhe dismisses the

field

and

can

fly

endlessly

as

long

as

motor

holds."35

That

in

1941

Graham was still

push-

ing himself in the direction of abstraction

is

evident

in

his

"Studio"series

(fig.

13),

which

Sidney

Janis

illustrated

in

his

1944

book Abstract

and SurrealistArt in

America.

In

the

accompanying

statement

made

in

1942

Graham

explains

that the

series "startedwith a

realistic interior

consisting

of

an old armchair with a

little

lamb's

hide thrown over

its

back,

a

green

plant,

a

square

antique

mirror

above the

chair

and secretaire to

the

right.

Every

subsequent

painting

of

this

subject

became a

further abstraction or

summa-

tion of the

phenomena

observed." Even

as Graham

writes of

pure

form,

his forms

remain,

as is clear

in

Studio,

surprisingly

rooted

in the external

subject

matter.

61 American Art

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

7/26/2019 Magus and Alchemist

18/23

14

John

Graham,

Omphale,

1943.

Oil and

pencil

on canvas

47.63

x

30.48 cm (18

3

x 12 in.). Collection

of Allan Stone

Gallery,

New

York

He is like an aviator

having

difficulty

taking

off.

By

1943 he

despaired

of the further

evolution

of form.

Since Picasso "had

done it

all,"

he turned

with a

vengeance

to

symbolic

Renaissance

figuration.

The

wounded

Omphale

(fig.

14)

is

quite

characteristic.

In

Apotheosis

fig.

15),

a

late

self-portrait,

the

heroic

figure

carries

on

his shoulders

emblems

of the sun and

moon;

the achieved

state

of

spiritual

illumination

is

symbolized

by

the third

inner

eye

of

yoga enlightenment

and

shafts

of

light

emanating

from the

fierce head.

Whereas Graham beat a retreatfrom

his

long

standing

convictions

about the

power

of abstraction

to

the

domain

of

symbols,

Pollock

maintains

an

allegiance

to both.

His

embrace

of the

spiritual

potential

of

paint

in

1941

would seem to

owe much

to Graham: Graham's

descrip-

tion

of

pure

form

as matter and

space,

"matter

as a

multiplied

plane,"

suggests

Pollock's sense

of

thick

matter and of

three-dimensional

space

as

literally

three-

dimensional

layers

in

Magic

Mirror.

Space

as "energyor matter in discharge or

liquidation"

suggests

Pollock's ambition

to drive

linear

impulse through

matter-

this last

definition

even seems to describe

Pollock's future

poured paintings.

In

Magic

Mirror,

Pollock

simultaneously

embraces both

symbolic

imagery, echoing

Graham's

reading

of Girl

before

a

Mirror

in

Untitled,

and

expression

with the

purer

means of

line

and

paint.

Why

does Pollock

begin

to succeed

in

enlivening

the

material

plane

on

a

relatively

abstract

level,

even as Graham

found

himself

at

an

impasse?

Already

in

Magic

Mirror Pollock had found a

way

of

meaningfully

linking

the

evolution

of

symbols

and the

evolution

of form

by

finding

abstract

pictorial equivalents

for

his

symbolic images.

Crucial

here is

the

axial structure

that

supports

both.

It

is

possible

that it

was Graham

who first

directed

Pollock's attention

to the

planimetric

structure

of

Mondrian's

works,

which Graham

read,

not as "mere

geometrical

simplifications

but as ana-

logues

of

profound,

if esoteric, emotional

states."

If

so,

there

was still a decisive

difference:

unlike

Graham,

Pollock did

not start his

painting

in

response

to

62 Fall

1998

This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.52.75 on Tue, 11 Dec 2012 13:40:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -