Mag. Matthias Gruber Risk sharing in the Euro area and the ...cdd73d05-dc7b-4d3c-b... · 3 BMF...

Transcript of Mag. Matthias Gruber Risk sharing in the Euro area and the ...cdd73d05-dc7b-4d3c-b... · 3 BMF...

Risk sharing in the Euro area and the European UnionLimitations, lessons learned and potential leaps forward

Mag. Matthias Gruber

3

BMF Working Paper Series

Risk sharing in the Euro area and the European UnionLimitations, lessons learned and potential leaps forward

Abstract: Since the onset of the financial and European debt crisis, market based risk sharing has decreased and it has become apparent that some form of ex-post risk sharing – so when something has already gone wrong – among the members of the Euro area might be useful or even necessary. In this vein Euro area member states established a sovereign lending framework to help each other in case of dire need. There is no consensus on further policy areas that could be subject to risk sharing among Euro area and potentially other European Union member states for the time being. However, the outlook is such that it is not unlikely to see further integration and risk sharing within the framework of the Banking Union over the next years. Certain general elements for risk sharing between countries can be determined for the mechanisms that are in place in Europe today for providing financial assistance to the benefit of sovereigns. This paper aims at identifying, structuring and valuing these general elements, thus providing decision support for any future discussion on ex-post risk sharing among Euro area countries.

The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the Ministry of Finance of Austria. Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author.

All cut-off dates for data are end of 2015 if not stated otherwise.

4

List of abbreviationsAPP Asset Purchase Programme by the ECB

BoP Balance of Payments Facility

BRRD Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive

CRA Credit Rating Agency

DGS Deposit Guarantee Scheme

DRI ESM Instrument for the Direct Recapitalization of Banks

EAD Exposure at Default

EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

EC Excess-commitment

ECB European Central Bank

EDIS European Deposit Insurance Scheme

EFSF European Financial Stability Facility

EFSM European Financial Stability Mechanism

ESBies European Safe Bonds

ESCB European System of Central Banks

ESM European Stability Mechanism

EU European Union

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GLF Greek Loan Facility

GNI Gross National Income

IFC International Finance Corporation

IFI International Financial Institution

IMF International Monetary Fund

LGD Loss Given Default

OG Over-guarantee

OMT Outright Monetary Transactions

PD Probability of Default

QE Quantitative Easing

RWA Risk Weighted Assets

SRB Single Resolution Board

SRF Single Resolution Fund

SRM Single Resolution Mechanism

SSM Single Supervisory Mechanism

US United States (of America)

VAT Value Added Tax

5

IntroductionIn early 2010 the first Euro area financial assistance programme was applied for and decided upon eventually in May of the same year1. In the absence of procedures, mechanisms and an institutional setup, the then 16 Euro area member states agreed to pool bilateral loans to the beneficiary member state to avoid a liquidity crisis. At the same time the Heads of State or Government decided to put two temporary mechanisms in place, creating a 500 billion Euro envelope for financial assistance to financially vulnerable Euro area countries. In 2012 a permanent insti-tution, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), started its operations, taking over the existing tasks from its tempo-rary predecessors. Those financial assistance mechanisms were operating on very different grounds, both legally and in terms of liability.

Already prior to the ESMs inauguration, discussions started on how to increase flexibility of the instruments available to the ESM in order to be able to address market disrup-tions more precisely2. In parallel, discussions on the cre-ation of a Banking Union for the Euro area Member States and potentially others has led to the creation of a single banking supervisory authority under the European Central Bank (Single Supervisory Mechanism – SSM), a Single Res-olution Mechanism (SRM) in the form of an acting board with a resolution fund (SRB/SRF) attached that should cover for potential resolution costs and lastly unified rules on national deposit guarantee schemes (DGS) (a common deposit insurance scheme has yet to be developed). Today, the ESM, while still a young organisation, already finds itself in a significantly different environment com-pared to when it was designed and inaugurated. And the environment will continue to evolve.

1 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cmsUpload/100502-%20Eurogroup_statement.pdf 2 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/european-council/pdf/20110311-Conclusions-of-the-Heads-of-State-or-Government-of-the-euro-area-of-11-march-2011-EN_pdf/; http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/european-council/pdf/20110721-Statement-by-the-Heads-of-State-or-Government-of-the-euro-area-and-EU-institutions-EN_pdf/ and http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/european-council/pdf/20120629-Euro-Area-Summit-Statement-EN_pdf/: in addition to loans, EFSF/ESM should be able to intervene in the primary and secondary market for bonds, provide precautionary assistance through credit lines or special earmarked loans for the recapitalization of financial institutions (so called “indirect” recap), as well as the direct recapitalization of banks.

The purpose of the article is threefold. Firstly, I want to look at the three main instruments designed over the last few years or currently under discussion, which all imply a certain amount of risk sharing among Euro area countries:

Financial assistance to sovereigns via loans to Euro area member states,

Credit line to the banking sector via Bridge Financing to the Single Resolution Fund and

Investments in bank equity via the Direct Bank Recapi-talization Instrument.

Secondly and foremost, I want to analyse the three main financing mechanism types established since the onset of the sovereign debt crisis and draw up some lessons learned from:

pooled loans (“100% Cash”), a joint guarantee framework (“100% guarantee or

commitment”) and a mix of the two (“Cash/Commitment mix”).

Lastly, I want to draw general conclusions and define specific considerations to be undertaken in the potential context of a possible future risk sharing exercise.

The outline of this discussion paper is as follows: Chapter 1 describes the instruments available or under discussion to provide financial assistance in brief and touches upon the limitations of the current frameworks. Chapter 2 explains and elaborates on the underlying structure and mechanics of the already existing risk sharing mechanisms in the Euro area and the European Union. Chapter 3 describes a model aiming at quantifying the expected cost of financial assistance granted under each of the main mechanisms outlined in Chapter 2. Chapter 4 gives an overview over the amounts provided by member states to back the financial assistance measures undertaken since 2010. Chapter 5 will then go into potential options to improve the ESM framework and to reconsider the financial stability architecture in the Euro area and the Banking Union. Chapter 6 will conclude the discussion.

6

Why could risk sharing be useful or even necessary between Member States?The European Union is not a federal state like the United States of America but more of a group of likeminded mem-ber states that agreed to cooperate and coordinate in cer-tain policy areas. A number of important policies remained national to a vast extent. Especially budgets are decided upon nationally, where responsibilities for both revenues and expenditure come together. The EU budget has a size of some 1% of Gross National Income and is thus not of macroeconomic significance.

However, the sovereign debt crisis since 2010 has shown that fiscal turmoil in one member state can have significant spill-over effects on other countries in the Union. Even though it is not possible to identify a precise counterfactual, a joint approach to risk taking appeared justifiable and indeed direly needed during crisis times, given the narrow financial interconnections of member states through cross boarder financial institutions of all kinds and the internal market.

According to Article 3 of the ESM-Treaty, “[t]he purpose of the ESM shall be to mobilise funding and provide stabili-ty support under strict conditionality, appropriate to the financial assistance instrument chosen, to the benefit of ESM Members which are experiencing, or are threatened by, severe financing problems, if indispensable to safegu-ard the financial stability of the euro area as a whole and of its Member States.” Similar objectives are stated in the EFSF framework agreement and the other relevant legal documentation underlying the different EU instruments for financial assistance (see Chapter 2 for more detail).It has been widely discussed whether or not programme design and financing were appropriate for those countries that have received financial assistance, amongst others most recently by Bruegel3 and the IMF4. From a purely financing and institutional side, the instrument tool-box of ESM (and its predecessor EFSF) was able to deliver what was needed at the time, which is liquidity support at favourable cost for the beneficiary countries.

However, in 2012 the limits of financial assistance through public loans were reached as one Euro area member states had to arrange for a voluntary debt restructuring exercise with private sector investors in order to bring nominal debt down by almost one third and thus being in a position to re-establish debt sustainability. As the financial sector of this member state was one of the largest creditors at the time, the debt restructuring exercise led to large capital needs for the domestic banking sector, which had in turn to be covered by the public sector again.

This drastic example as one out of many should de-monstrate how deeply intertwined the relations between individual member states’ public finances and the respec-tive domestic banking sectors can be5 . Several steps and initiatives were taken throughout the last years to loosen this link, still it remains to be seen to what extent negative feedback loops between the public and the banking sector were reduced.

Starting as early as 2011 and 2012 it was questioned whether the tool-box of ESM financial assistance instru-ments was sufficient to make it a highly efficient crises resolution mechanism for the Euro area6. At the time no compromise could be reached regarding ESMs role in banking going beyond the instrument for so called “indirect bank recapitalization” (via dedicated loans to a beneficiary member state) before the ESM-Treaty was signed in early 2012. However, as a consequence of severe financial mar-ket turmoil in most of the Euro area member states, the ESM members stretched for a deal as early as June7 2012 in order to break – or at least alleviate – the deadly em-brace between failing banks and public finances. After long lasting discussions, in parallel to the creation of a Banking Union, Euro area finance ministers in their role as ESM Go-vernors finally decided in December 2014, […] to establish the ESM instrument for the direct recapitalisation of institu-tions […] as a financial assistance instrument […]”8.

3 http://bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/publications/20140219ATT79633EN_01.pdf 4 http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2015/110915.pdf 5 The sovereign bank loop has also widely been discussed and analysed. See for instance: https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2014/122214.pdf http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1293 6 for instant http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/995a3f18-d001-11e1-bcaa-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3wMimF5BC or http://www.lisboncouncil.net/publication/publication/70-making-european-stability-mechanism-work.html 7 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/european-council/pdf/20120629-Euro-Area-Summit-Statement-EN_pdf/ 8 http://esm.europa.eu/pdf/20141208%20Establishment%20of%20the%20instrument%20for%20the%20direct%20recapitalisation%20of%20institutions.pdf

Chapter 1: Instruments and limits for the provision of public financial assistance

7

The introduction of the direct recapitalisation instrument (DRI) was a far reaching step. While the ESM in its initial conception included some form of risk sharing, the burden clearly remained with the member state benefitting from financial assistance (even if it would take a hundred years to repay the debt). With DRI responsibility and risk sharing between euro area states as ESM members was shifted to a whole new level, as all members were accepting to carry a certain risk together, still very limited in size for the time being, in order to safe an ailing bank established in one of its members territory. Preconditions for this deci-sion were severe market panic in June 2012 (sovereign yields for some large Euro area member states stood at 7% and above) on the one hand and the establishment of the Single Supervisory Mechanism as well as the Single Resolution Board on the other hand. Most of the immedia-te market pressure on sovereign yields has emanated since then, mainly as a result of the ECB interventions announ-ced and undertaken since August 2012. Still the potential fallout from banking problems on some countries is non negligible.

DRI is a unique instrument in the international financial assistance architecture. Whereas the World Bank/Interna-tional Finance Corporation (IFC), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) or other Interna-tional Financial Institutions can invest in bank equity under development considerations, neither the IMF nor one of the other European assistance facilities (BoP, EFSM or Macro-Financial Assistance to third countries) has a com-parable instrument in its tool-box for crises financing. None of the existing instruments is designed to acquire shares in distressed banks lacking a sufficiently strong growth po-tential. In order to address member states’ concerns about the risks of such a joint operation, the current ESM-DRI setup includes a number of clauses that limit the scope of its usability. Amongst others it can basically only be applied for member states that are financially strongly strained, thus, effectively limiting DRI to banks in a hostile macroe-conomic environment with a potentially vulnerable outlook and weak, impaired assets. Also it poses a non-negligible burden on the implicitly benefitting member states, in which the bank is located. Still, member states go much further in terms of risk sharing and joint action than with any other similar instrument. Amongst others, ESM would be the steward for the ESM members to hold and manage the equity stake in a saved bank9.

The 5-Presidency-Report has identified the improvement of the DRI as one of its priorities10. However, as long as the reservations of some member states regarding large scale

risk sharing with lacking control over national policies and the new bail-in regime not yet fully proven in practice are not dissolved, the application of DRI remains unlikely for the time being. But even if the scope of the instrument in its current form is rather narrow, the door for deeper common risk sharing was opened.

Finally in December 201311 and again in December 201512 Eurogroup and ECOFIN Ministers agreed to put a sys-tem of bridge financing in place to backstop the newly established Single Resolution Fund (SRF). This backstop is designed as a system of national credit lines to the indi-vidual country compartments within the SRF for the time being. However, a common backstop should be created by 2024 at the latest that is intended to further loosen the link between national public households and potential bank failures. In the absence of a political decision on whether an existing or new institution should take over the role of the common backstop, the paper amongst others aims at identifying an analytical footing for how the financing mechanism to backstop the SRF should be shaped.

The question that remains to be answered is what an efficient strategy could be for cases in which the existing and envisaged practices, procedures and mechanisms for risk sharing among the private and public sector on the one hand and among countries on the other hand reach their limits. The question could either arise once public indebtedness of one European country reaches levels that make it no longer sustainable with high degree of certain-ty, as the IMF puts it13, or if the sovereign bank feedback dynamics are such that spill-over effects are large enough to pull public finances in one or more countries in Europe down.

9 http://www.esm.europa.eu/pdf/20141208%20Guideline%20on%20Financial%20Assistance%20for%20the%20Direct%20Recapitalisation%20of%20Institutions.pdf 10 http://ec.europa.eu/priorities/economic-monetary-union/docs/5-presidents-report_en.pdf 11 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/council-eu/eurogroup/pdf/20131218-SRM-backstop-statement_pdf/ 12 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/12/08-statement-by-28-ministers-on-banning-union- and-bridge-financing-arrangements-to-srf/ 13 http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2015/052715.pdf

8

In the first few years of the European sovereign debt crisis risk sharing took place in the form of loans to a sover-eign provided jointly. The lowest common denominator was thus collective sharing of credit risk originating from one member of the club by means of extended maturity transformation at below market prices. The underlying political assumption behind this approach was that the-re is basically no sovereign credit risk originating from European countries and that no nominal write-offs would ever be necessary. By pricing credit risk according to this assumption significantly different than the market at the time, the net present value of public debt was substanti-ally lowered. The same principle applies for the option of credit lines that are offered below market prices and thus limiting liquidity risk on the one hand and which provide the fall-back option to transform debt at market terms into long-term loans at concessional terms. Where problems of a member state emanated mostly from the financial sector, equity risk was transformed to credit risk from the point of view of the countries providing financial assistance through the instrument of dedicated so called loans for the “indi-rect” recapitalisation of loans outside of a fully fletched macro-economic adjustment programme with wide ranging policy conditionality. The principle of shifting the burden of equity risk back to the financial market via bail-in of debt or of partially carrying it jointly among all member states was established at later stages of the ongoing crisis.

From a theoretical point of view it is difficult to apply concepts of risk sharing and insurance in this context. Risk sharing or financing in the context of this paper takes place where there is no longer a market participant willing to take over certain risks such that there is no market price available and the need for public risk sharing arises. As events triggering these kind of risk sharing measures are rare, there is not much data and estimates have to be built on believes and experts opinions to a large extent. Also the environment in which the analysed risk sharing and financing mechanisms take place is determined by a limited pool of members, so there is little room for broader risk sharing and mitigation options. There is a certain risk transfer element, as those countries, in which large parts of the risk originate, do not necessarily carry a corre-

sponding share of the immediate burden of risk sharing (for further detail see Chapter 4). However, risk absorption and joint financing provides a broader benefit – a com-mon good – to all members of the pool, namely financial stability.

In the absence of structures and institutions at the onset of the Euro area sovereign debt crisis member states arranged the first financial assistance programme in the form of pooled bilateral loans (the so called Greek Loan Facility – GLF). All member states had to fund their share in the loan individually whenever a disbursement was due. Those loans were elevating national public gross debt levels for providers and the recipient accordingly. As a second problem, some member states were facing higher financing costs than what they received in return for the bilateral loan at some point in time. Thus, as no creditor state should incur any budgetary costs through granting financial assistance, a complex compensation framework had to be established to reimburse those member states. The terms of those loans had to be amended from time to time in order to improve the debt servicing capacity of the beneficiary. In the end some member states might end up being faced with funding costs higher than the revenue from their share in the pooled loan.

Therefore the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) was created, a company agreed upon by the countries of the Euro area in May 2010. EFSF was then incorporated in Luxembourg under Luxembourgish law in June 2010 backed by guarantees of its member states14. The joint ap-proach should enable EFSF to raise funding in the market with a high rating attached and thus lower funding costs. Ministers of Finance were furthermore hoping that the guarantees would not materialize on their public balance sheets as compared to the pooled bilateral loans. Despite that hope Eurostat decided to fully reroute EFSF loans to beneficiary member states to the guarantor states, thereby again elevating the individual national stocks of gross public debt. In addition, due to shortcomings in the EFSF structure the guarantee ceiling had to be augmented substantially by introducing large amounts of over-guar-antees15. This joint and several liability structure basically

14 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/en/misc/114977.pdf 15 http://efsf.europa.eu/mediacentre/news/2011/2011-011-efsf-amendments-approved-by-all-member-states.htm 16 http://esm.europa.eu/press/releases/20121008_esm-is-inaugurated.htm

Chapter 2: Risk sharing mechanisms in the Euro area and the European Union

9

made the then six AAA-guarantor states liable for the entire outstanding debt of EFSF, should the lower rated members not be willing or able to deliver on their guaran-tees.

Bearing said structural encumbrances in mind, Euro area leaders decided to create a permanent fully-fledged new International Financial Institution (IFI) with indepen-dent boards, hoping that such an approach would create sufficient confidence in the market for sovereign bonds that the sovereign debt crisis would come to an end. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) was established in October 201216 as a Treaty based IFI, following decisions of the Heads of State and Government of the Euro area and the ECOFIN council in 2010 and 201117. Since then, ESM members have paid in more than 80 bil-lion Euros in paid-in capital and provided more than 620 billion Euros as callable capital to the institution (see Graph 1 below). As laid out in Article 3 of the Treaty18, ESM funds its financial assistance operations through means raised in the market, whereas the paid-in capital serves as security for investors and remains untouched for pro-gramme financing.

In the following I would like to shed some light on the underlying mechanics of risk sharing mechanisms in use so far by the Euro area member states. Other Mechanisms backed by all EU member states will not be looked at in detail, though I will refer to similarities. This risk sharing assessment is merely from a Member States perspective. Investors and Credit Rating Agencies perspectives will only be touched upon briefly and treated as given externalities.

From a very narrow risk perspective, the Greek Loan Facility (GLF) type is the “cheapest” option for the highest (AAA/AA) rated member states19, as one Euro of financial assistance comes at a cost of one Euro. Also there are no ex-ante payments into the risk sharing pool that would imply opportunity costs for the insurance against certain risks. As long as public gross debt is at a reaso-nably low level, which is likely for high rated countries, and interest received covers own financing cost entirely. However, given that the amendments to the GLF have led to very low interest payments by the debtor country, this result would only hold in the context of a sovereign loan for very optimistic assumptions on own funding costs for a longer period of time and it definitely does not hold with certainty for those member states with weaker credit ra-tings assigned, elevated levels of public debt and high and volatile financing costs.

The underlying Inter-creditor agreement between the countries contributing to the GLF includes an option to step out of the obligations under the agreement, once a member becomes a programme country itself. If a member steps out of the framework, its share in future contribu-tions has to be taken over by the remaining members, which will increase their share accordingly (i.e. share per Euro provided, it does not increase the nominal obligations to pay but lowers the overall amount to be disbursed)20.

In the EFSF framework all members are jointly and seve-rally liable with over-guarantees of up to 165% (the gua-rantee maximum amount divided by the maximum lending capacity). This structure shifted most of the immediate risk to the highest rated members of the guarantee-envelo-pe. Over-guarantees are added on top of each individual share of the guarantee and thus add credit risk of up to 65% of the share of each respective high rated member state on top of the credit risk for the financial assistance granted to one beneficiary member state (six EFSF mem-bers would have had to be held liable to pay back 100% of each Euro raised in the market). The risk assessment for the EFSF structure is thus depending on the assump-tions on probability of “primary” default for the beneficiary debtor country as well as “secondary” default for the lower rated co-guarantors and the actual Losses Given Default attached. On the other hand, as there is no upfront cash payment, funding backed by EFSF type guarantees is “free lunch” in terms of funding costs, as long as no guarantee is called. Unfortunately, Eurostat decided in January 2011 that the funds raised in the framework of the European Financial Stability Facility must be recorded in the gross government debt of the euro area Member States partici-pating in a support operation, in proportion to their share of the guarantee given21.

The underlying framework agreement between the coun-tries contributing to EFSF also includes an option to step out of the obligations under the agreement, once a mem-ber becomes a programme country itself. This option could be waived if a country is benefitting from financial as-sistance other than a macroeconomic adjustment program-me according to criteria outlined in the specific instrument guidelines22. Hence, the contribution keys for the financing mechanisms to be analysed will depend on the purpose of the applied instrument (for further detail see Chapter 4).

The ESM structure is a combination of the two concepts above, where the liability side (authorised capital stock) is backed by an upfront paid-in cash share (paid-in capital)

17 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cmsUpload/Conclusions_Extraordinary_meeting_May2010-EN.pdf18 http://www.esm.europa.eu/pdf/ESM%20Treaty/20150203%20-%20ESM%20Treaty%20-%20EN.pdf19 For the purpose of this paper the notion “highest rated member states” includes those Euro area countries that were assigned with at least AA by Standard and Poor’s, Fitch as well as DBRS and at least Aa2 by Moody’s as of 31.12.2015. The criterion is slightly stricter than the regular definition of investment grade bonds. The reason is that those countries that formed the “backbone” of the EFSFs rating since 2010 should be covered.20 if share of countries x and y are 5% and 10% respectively, country x would have to take over 5% of the 10% of the stepping out country y: 21 http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/5034386/2-27012011-AP-EN.PDF22 http://efsf.europa.eu/attachments/efsf_guideline_on_recapitalisation_of_financial_institutions.pdf

10

and a guaranteed share (callable capital or authorised capital unpaid). In the ESM framework members are again jointly and severally liable for the ESMs liabilities, though with limits. The implicit over-guarantee (i.e. sum of calla-ble capital divided by the lending capacity not covered by paid-in capital) is lower for ESM than for EFSF. However, where EFSF guarantors are liable for each bond issued individually to the extent of the applicable over-guarantee, ESM shareholders could be asked to redeem a maturing liability in full in the theoretical case that capital would be depleted and a sufficiently large number of members is not honouring its obligations. This is of course merely a hypothetical case and, given the maturity structure of both institutions’ liabilities, not of major concern.

In addition, where guarantors have to cover up for inte-rest and costs of EFSF in full on top of the guarantees on capital, commitments to ESM are limited to the individual nominal shares so including interest.

In January 2013 Eurostat decided that, contrary to the EFSF, debt of a beneficiary country will be recorded as due to the ESM. Operations undertaken by the ESM, such as borrowing on financial markets and granting loans to beneficiary countries, will be recorded in the books of the ESM and will not be re-routed to the Euro Area Member States23. Lastly, in the ESM framework, beneficiary mem-ber states do not have the option of stepping out of the guarantee obligations as with the EFSF, which again limits the individual shares of the contributing member states to some extent.

Both EFSF and ESM hold liquidity to varying degrees, amongst others to cater for upcoming payment obliga-tions. In addition ESM runs a T-bill programme and holds a certain amount of paid-in capital in highly liquid assets to further foster liquidity and improve credit strength. Lastly, both institutions have a prudent funding strategy with debt maturities of currently up to 40 years. The immediate risk of a call on guarantees and callable capital is thus stret-ched along the curve of outstanding debt.

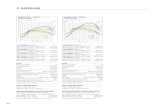

The following Graph 1 shows the EFSFs and ESMs capital structure and visualizes the significant credit enhance-ment to be provided in the form of over-guarantees or excess-commitments in order to ensure the targeted len-ding capacity at the highest credit rating possible.

EFSF had a credit rating at the cut-off date of AA/Aa1/AA from Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch24. ESM had a credit rating at the cut-off date of Aa1/AAA from Moody’s and Fitch Ratings, but none by Standard & Poor’s amongst others for conceptual reasons25.

Note again that the concept of over-guarantees has to be distinguished for the two different institutions. While for EFSF the applicable over-guarantee is capped at a certain percentage per debt instrument issued, it is more of an average observation per member state for ESM. So for one Euro issued under EFSF, each member can be held liable for its own share plus up to 65% of that individual share plus interest. In contrast, each member under ESM holds a certain share for which each member is entirely liable regardless of the amounts at risk including interest. For instance, if ESM were to issue debt of one euro and all but one member default in the event of a capital call, the remaining member would have to redeem said one euro in full. In a second step, there are internal mechanisms to settle unfulfilled payment obligations that were taken over by other member states for both EFSF and ESM.

As the liability side of EFSF is entirely backed by guaran-tees, the EFSF’s rating is fully depending on the credit worthiness of its guarantors. It is thus more directly linked to downgrades of individual member states then it is the case for the ESM.

Now putting all the elements of the three financing mecha-nisms under scrutiny (GLF type with “100% cash”, EFSF type with “100% guarantees or commitments” and ESM type with a “cash/commitment mix”; where guarantees and commitments can imply some form of over-guarantee or excess-commitment) together, the effectiveness of each type can be quantified based on a number of assumptions and specifications (for further details see Chapter 3):

23 http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/1015035/2041337/Eurostat-Decision-on-ESM.pdf/6e87bbe1-f081-43a4-8543-cc62f32eefc124 http://efsf.europa.eu/investor_relations/rating/index.htm [23.03.2016]25 http://www.esm.europa.eu/investors/rating/index.htm [23.03.2016]

Graph 1

11

Mechanisms 100% Cash 100% Guarantee / Commitment

Cash/Commitment Mix

Properties “GLF” type “EFSF” type “ESM” type

Cash √ (ad-hoc) - √

(up-front)

Guarantee/Commitment - √ (up-front)

√ (up-front)

Credit enhancement: over-guarantees or excess-commitment - √ √

Additional liquidity required - (at national level) √ √

Funding costs fully covered Not necessarily By definition By definition

Individual contribution keys

Variable due to stepping-out

option (fixed nominally)

Variable due to stepping-out option

(fixed nominally)

Fixed (no stepping out)

Debt rerouted to public balance sheet √ √ -

Probability of Primary Default and Loss given Primary Default of beneficiary member state,

Probability of and Loss Given Secondary Default of co-guarantors and share of defaulting co-guarantors,

the purpose of the financial assistance operation, which is amongst others relevant for the contribution keys of contributing member states (stepping out

option!), the amount of over-guarantee or excess-commitment

applied, whether a cash payment has to be made by creditor/

guarantor member state (i) ex-ante (before risk sha-ring exercise is actually needed), (ii) ad-hoc (once an actual risk has to be shared or a disbursement has to be funded) or (iii) ex-post (once a guarantee has to be drawn or a commitment fulfilled),

whether debt is (statistically) rerouted by Eurostat and own funding costs, maturities and interest/dividends

received by creditor/guarantor member states.

It should also be referred to explicitly at this point that this analysis does not reflect at all on the various aspects of the organisational and operational setting of the mecha-nisms described. ESM as an institution has undoubtedly a number of advantages as compared with its ad-hoc predecessors that were more or less created overnight and

are definitely not designed to stay there for a longer period of time.

Just to mention them, other forms of risk sharing that are applied in the European Union and play a role in crises financing in one way or the other are the European Union budget and the balance sheet of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB).

The European Union budget is endowed with so called own resources, which are partly collected from national sourc-es, mostly VAT revenues, and sources considered common revenues, mostly customs. Every Member States contrib-utes to the common budget according to a contribution key, derived from a number of key indicators (mainly Gross Nation Income – GNI) without any kind of over-guarantee attached. The total (actual) payments ceilings in the finan-cial framework are always lower than the own resources ceiling. The margin between own resources ceiling and the ceiling for payment appropriations allows the financial framework to be used, to cover unforeseen expenses26. Amongst others, this margin is used to back bonds issued in the context of the Balance of Payments assistance (BoP for non-euro area EU-member states27) and the European Financial Stability Mechanism (EFSM for euro area member states28). In economic terms, each member state is sever-

26 http://ec.europa.eu/budget/explained/budg_system/fin_fwk0713/fin_fwk0713_en.cfm27 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32002R0332&from=EN as amendedhttp://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32008R1360&from=EN andhttp://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32009R0431&from=EN28 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32010R0407&from=EN as amended http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32015R1360&from=EN

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics and properties of the three possible risk sharing structures:

12

ally liable, similar to a guarantee without over-guarantee. The European Union, however, has a sizeable budget and thus sufficient liquidity available. A Euro area budget could theoretically mimic these features, though it is not likely to be realized anytime soon for political reasons.

Note that the relative contributions to the EU budget of each member vary slightly over time due to changes in the underlying indicators, whereas figures for Gross National Income play an important role. It appears that the rat-ing of the EU budget is not adversely affected by these changes. The European Union had a credit rating of AAA/Aaa (outlook stable) from Fitch and Moody’s as well as an AA+ (outlook negative) rating from Standard & Poor’s29 at the cut-off date30.

EFSM, EFSF and ESM have in common that they are backed by some form of guarantee (guarantees, callable capital and the margin). Regardless of the actual construc-tion of a commitment the legal nature of a commitment needs to be sufficiently assuring to investors, for which questions on the governing law need to be addressed.

For the European Central Bank (ECB), profits and losses that cannot be offset against provisions are shared among the participating national central banks according to the capital subscription key31.

Other forms of pooled funding are for instance the EIB that has a somewhat similar capital structure as the ESM (paid-in plus callable capital from all 28 EU member states)32 and the SRF, for which Banking Union member states collect contributions based on the SRM-Regulation33 and the Intergovernmental Agreement34 and provide credit lines to assure a certain amount of liquidity in the national compartments.

Another key factor for a crises financing mechanism is that funds need to be readily available, once a decision to dis-burse is made. Liquidity is therefore of utmost importance, which is one more reason why all mechanisms described above aimed at achieving the highest possible grade from Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs).

Creditor seniority and equal treatment are issues to be considered for sovereign loans. GLF and EFSF loans are pari passu, while ESM financial assistance in general benefits from the institution’s preferred creditor status.

For banking related activities the question of seniority is different. Bridge financing to the SRF is repaid through ex-post levies collected from the entire banking sector and is thus no liability in their balance sheets. On the other end of the spectrum, equity potentially acquired under a direct recapitalisation exercise is by definition the first share to absorb losses in case of insolvency or resolution.One last aspect that should be mentioned is the invol-vement of national parliaments in crises financing that evol-ved during the Euro area sovereign debt crises throughout a number of Euro area member states. The involvement is most evidently visible for ESM as compared to the other mechanisms as ESM constitutes by far the largest exposure for members as well as the only permanent obligation com-pared to the temporary mechanisms GLF and EFSF.

Few EU member states have national procedures in place for the EU’s BoP Facility and the EFSM to date. However, it could be possible that if either the capacity or the role in banking related crises financing of one or both of these two EU mechanisms would be extended, national parli-aments in more and more member states might want to have a say in the decision making process.

Concluding this chapter, it should be mentioned that the three mechanisms analysed in detail as well as the other mechanisms mentioned do not represent the entire univer-se of options. A number of alternative concepts have been discussed in the last few years for different ways to share risks among member states that will not be analysed in this paper. Just to name a few, for instance a “blue bond” proposal was created by Bruegel35, a concept for a “Schul-dentilgungfonds” (bond redemption funds) by the German Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirt-schaftlichen Entwicklung36, European Safe Bonds (ESBies) by the euro-nomics group37 and a special report was drawn up by the EU Expert Group on Debt Redemption Fund and Eurobills38.

As a thought experiment, a completely different appro-ach for Euro area countries could have been to provide guarantees or collateral directly to programme countries to back individual national debt issuances, instead of fun-ding financial assistance loans via a joint mechanism. This instrument is used for instance by the Japanese and the US government to support access to funding for countries under fiscal stress (for example in 2014 to the benefit of Ukraine and Tunisia or most prominently during the late

29 http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/eu_borrower/index_en.htm as of 23.03.201630 The Analysis does not yet take into considerations the potential fallout from the decision of the UK to end its membership in the EU.31 https://www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/orga/capital/html/index.en.html32 http://www.eib.org/attachments/general/statute/eib_statute_2013_07_01_en.pdf33 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014R0806&from=EN34 http://register.consilium.europa.eu/doc/srv?l=EN&f=ST%208457%202014%20INIT35 http://bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/publications/1005-PB-Blue_Bonds.pdf36 http://www.sachverstaendigenrat-wirtschaft.de/fileadmin/dateiablage/download/publikationen/arbeitspapier_01_2012.pdf37 https://euronomics.princeton.edu/esb/38 http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/articles/governance/2014-03-31-redemption_fund_and_eurobills_en.htm

13

1980ies and throughout the 1990ies when large quantities of Bonds commonly known as “Brady Bonds” were backed by the US Treasury to the benefit of several developing and emerging market countries 39).

Regardless of any operational or organisational pros and cons of those alternative approaches, the assessment of exposure for the guaranteeing member states to interest and credit or equity risk would have been the same as for the three mechanism types GLF, EFSF and ESM. Thus, the same considerations regarding the provision of liquidity, loss absorption capacity and potentially credit-enhance-ment would apply for alternative approaches.

39 https://www.jbic.go.jp/en/information/press/press-2014/1008-30692 https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/july-24-2014-government-tunisia-issues-500-million-bond-us-guarantee https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/press-releases/may-16-2014-government-ukraine-issues-us-1-billion-bond-us-guarantee http://www.people.hbs.edu/besty/projfinportal/ssb%20brady%20primer.pdf

14

In order to rank the different financing mechanisms dis-cussed in this paper, a valuation tool was established that models and generalises the individual features of the struc-tures analysed into a framework with restricted complexity. The model is deliberately simple and does only consider a limited number of factors to evaluate the expected value of one Euro of financial assistance granted by the three main mechanisms (pooled loans, pooled guarantees and cash-commitment-mix) applied since 2010. The other financing options, such as the EU budget as discussed only very briefly in Chapters 1 and 2, are not considered in this evaluation exercise.

The expected value E(a), where a defines all necessary underlying parameters, is determined as follows:

E(a)= PD*EAD*LGD

For simplicity reasons EAD is defined as one unit per member state participating in the scheme. In this model E(a) is compiled by several terms, whereas PD is treated as exogenous and EAD and LGD are impacted by several factors:

(1) – (2) – (3) – (4) = (5)

(1) Expected revenues from financial assistance granted

+ (1-PPD)*(1+r)maturity

+ PPD*[(1+r)years to D-1]+(1-LGPD)*(1+r)(maturity-years to D)

+ (1-PPD)*(1+d)maturity +PPD*(1+d)years to D

(2) Capital and funding costs

- (1+i)maturity

(3) Expected cost of beneficiary defaulting

- PPD*LGPD*(1+i)(maturity-years to D)-1

(4) Expected additional cost of co-guarantors defaulting

- PPD*LGPD*PaLSD* 1 *(1+i)(maturity-years to D)

(5) = Expected value of one Euro financial assistance granted for creditor/guarantor MS

where:

PPD Probability of Primary Default of beneficiary member stateEAD Exposure at DefaultLGD Loss Given DefaultPaLSD Probability of and Loss Given Secondary Default of co-guarantors (PSD * LGSD)

π (OG) Share of co-guarantors to be taken over by other member states as a function of maxi mum Over-guarantee/Excess-commitment.

The parameter indicates by how much the individual contribution to financial assistance is increased by the share of defaulting co-guarantors and ranges between 0% andmaturity Number of years for which financial as sistance is granted

years to D Number of years after granting financial as sistance at which a beneficiary defaultsi Own funding costr Interest received (not necessarily the same as i)d Dividends received on paid-in capital (not necessarily the same as i or r)

(1-π)

Chapter 3: Expected value of financial assistance granted

40 While the EFSF guarantee limit does not include interest, it is covered by ESMs authorised capital. The maximum share of co-guarantors defaulting relevant for the maximum lending volume of 500 billion Euros is thus smaller or equal to ~32% depending on ESMs own funding costs.

15

and

(1 ) the first line is straightforward and shows the calcula-tion of the expected amount to be amortized once financial assistance granted is redeemed plus optional dividend payments on paid-in capital.

(2) the second line entails the calculation of capital and funding costs for those options, where member states have a liability in their books throughout the lifetime of financial assistance granted even if no cash payment has been made, that have to be born in any case. For the EFSF type the value is one, because member states only have their share rerouted to national public debt but there is no immediate cost or benefit attached to the guarantee. For ESM as there is not additional liability rerouted to national public debt beyond the capital share has to be paid in in advance.

(3) the third line deducts additional costs that only occur for those options, in which no upfront cash payment has been made, once a beneficiary defaults with a certain Pro-bability of Default. This is not relevant for GLF, where all costs and interest received is accounted for in the first two lines. However, once a member state defaults on EFSF or ESM and a guarantee is drawn or callable capital is called, member states will incur costs for financing their share in the financial assistance lost.

(4) the fourth line shows how the additional cost for those options is deducted, where over-guarantees or excess-commitment apply if co-guarantors in EFSF or ESM default on their guarantee or callable capital subsequent-ly to a beneficiary member state defaulting. The formula makes it clear that this cost element will be rather limited from an entirely probability based point of view.

The basic rational between the different calibrations of the model are again simple:

Maturities are longer for financial assistance in the form of sovereign loans (currently between 30 to 45 years) than for banking related operations (between two to three years for loans to SRB/SRF and five to seven years for equity investments).

Default is the moment in the lifetime of the invest-ment, where actual losses on the nominal amount have to be realised. Years to Default defines the number of years for which the investment performs as planned. Default in this model is a single event, at which a one-off loss has to be written off. There is no consecutive restructuring or loss incurrence, both for loans and equity.

41 http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14346-2015-INIT/en/pdf 42 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52013XC0730(01)&from=EN

In this context, sovereign loans are associated with a low to medium risk of outright default and very long maturities, as there will almost always be a debt restructuring until the respective beneficiary is in a position to service its debt. However, if a potential default would only occur after several years, the time span to default was set at 10 years in the model which is the current grace period enshrined in the terms and conditions for GLF, EFSF and ESM loans.

Banking related operations could occur either in the form of loans to the SRM or in the form of equity investments through DRI, which are associated with either low or high risk and short to medium term maturities respectively. A loan to SRM would be short-lived with a maturity of up to three years41 as currently defined for the temporary backstop. The assumption is that a hypothetical default would most likely occur during or after the second year. There is no predefined maximum time horizon for equity investments, so a proxy of 7 years is used, which is derived from state aid rules42. A potential default or more accurately loss absorption in this context would most likely occur towards the end of this period.

Own funding costs of contributing member states can range between very low cost if shorter term funding is considered and higher cost if an average nominal inte-rest rate paid on the entire outstanding stock of public debt is considered. Funding costs do not necessarily have to be covered by interest received, dividends, profits or fees. This could especially be the case for GLF type financing where member states with lower credit ratings and/or higher debt stocks outstanding could be confronted with revenue flows that do not cover their own funding costs.

The purpose of the model is to assess which financing mechanism should be used for which kinds of applications. I will therefore use the three cases described in detail in Chapter 2 to determine the risk and cost associated with each option. The various assumptions used are purely hypothetical and not based on econometric analysis. In the absence of historical data, the scenarios for Proba-bilities and Loss Given Default are not empirically tested. The parameters chosen aim at forming a reasonable scenario and describing the underlying mechanics of the three different financial assistance financing arrangements.

16

The approach differs from a standard credit rating agency assessment that looks at the Probability of Default over a specific time horizon. In this model all investments are compared over the entire distribution of Probability of De-fault in order to identify areas in which different financing mechanisms could perform differently. However, relevant individual values for PD can of course be chosen for each type of investment to enable a credit rating based evaluati-on and to produce comparable one-off pictures.

For the tables and graphs shown in the Annex, different figures for own funding costs and maturities were applied, whereas maturities are associated with different kinds of operations and thus risk and loss distribution (see next page), everything else being equal.

A standard set of Probabilities of Primary and Secondary Default, maturities and funding costs as well as potential revenues will be used for the scenarios. The parameters LGD, and years to D are not assumed flat over the entire lifetime of an operation and are subject to risk weighting along specific probability distributions. The following gra-phs show how the risk relevant parameters evolve over the relevant ranges.

From a singular perspective, the Loss Given Primary De-fault is varying with the purpose chosen, while Probability of Secondary Default (including Loss Given Secondary Default) and share of defaulting co-guarantors is steady as it is attached to the same sovereign risk in all three cases.

The displayed distributions for Losses given Primary Default as well as for the point in time of occurrence of a default are the basis for the results of the cost assessment for the individual financing mechanism types discussed on the following pages (note that percentages are used for the parameter Years to Default as the actual maturity of the investment differs significantly for the three types con-sidered: Sovereign loan, SRF loan and Equity investment).

Graph 2

17

Default has a very distinct meaning for all the three types of investment. For an extremely long term sovereign loan, default of a country rated at the brink of investment grade, is not entirely out of the world, even though still not very likely. If ever to occur, losses are assumed to lie in a range between 10 to 30% of capital for most of the cases. A loan to the Single Resolution Fund would be short-lived, between 2 to 3 years, and backed by the entire banking sector of the Banking Union. An actual default appears quite unlikely, though if ever to occur losses are assumed to be higher than for a sovereign loan. Lastly, default for an equity investment has the meaning of realising a loss. Given the distressed environment and state of the bank itself, such an event is more likely than not.Different parameters play a role in the assessment depen-ding on the three cases of application. Overall the assess-ment is robust regarding the underlying mechanics of the modelled mechanisms and thus in terms of deducted ran-kings. It is therefore possible to draw general conclusions from the analysis (see Graph 3 and graphs in the Annex).

The expected values are sensitive regarding the assumpti-on on own funding costs and duration of an operation. The more expensive capital costs for ex-ante paid-in capital or cash the more attractive is a guarantee structure. The main disadvantage of ESM that comes into play in the model is the fact that paid-in capital has to be provi-ded, which is never to be reimbursed to the contributing member states. The presence of dividends received on paid-in capital would naturally alter the results. Also if this component would be considered sunk costs and thus less relevant for the analysis, the effect would be significant-ly lowered to funding costs of the paid-in share, which affects the difference in expected values for risks shared

only with longer durations such as sovereign loans. On the other hand, ESMs operations are not recorded on national public debt and there is no stepping out option under the ESM-Treaty, which in turn constitutes a significant advan-tage for higher rated member states that have to provide a smaller share in such a setting. Also ESM is assigned with the higher rating that is more robust than the one for GLF (measured as hypothetical average rating of Euro Area countries) or for EFSF. The latter case makes the ESM the cheapest option for beneficiary debtor countries as it stands today.

The ESM type appears to be less attractive as own fun-ding costs for the national shares in paid-in capital of ESM have to be financed regardless of the actual Probability and Losses given Primary and Secondary Default. In the absence of any dividends received, own funding costs result in being the main cost driver for the ESM type option. If dividends are received on ESM paid-in capital and the paid-in capital share is not considered to be a cost component, ESM turns out to be the most cost effective mechanism to finance stability support. It also needs to be mentioned again that ESM is the only mechanism that does not foresee a stepping out option for beneficiaries of sovereign loans.

For medium term operations, as associated in this cont-ext with operations with potentially higher Losses Given Default, the GLF type expected costs develop in parallel to the EFSF types’ expected cost, as long as own funding costs are covered in full. Only for longer term operations and very high Probabilities and Losses Given Default, GLF type costs converge towards ESM types’ full cost. Own funding costs play a significant role in this development. If own funding costs are higher than revenues received in re-turn, the GLF type financing structure is inferior to an EFSF or ESM type structure. It should be noted in this respect that it is not unlikely for lower rated contributing member states that own funding costs cannot be entirely covered for the GLF type financing structure.

Over-guarantees and excess-commitments play a limited role in the analysis and do only matter for very high ratios of Loss Given Default and a share of co-guarantors defaul-ting.

Also dividends on paid-in capital do not alter the overall picture significantly.

18

Summing up, the three financing mechanism types con-verge only either for very high Probabilities of Primary and Secondary Default as well as high Losses given Primary and Secondary default or for low to medium risk of pri-mary default, assuming low own funding costs in the risk based cost assessment. That means that where very high probabilities of primary default and large losses of the in-vestment are assumed – as it could be the case for certain banking related operations – the difference between EFSF type and ESM type structure could become less signifi-cant for the member states contributing to the financing mechanism.

Graph 3: Baseline Scenario (see also Annex)

19

The following chapter will provide an overview over the origins of risks as well as the contributions by member states to share these risks ex-post, i.e. once something has gone wrong. Potential risks in this respect emanate mostly either from public gross debt, or from bank balance sheets as outlined in Chapter 2 (for banking related activ-ities, both total and risk weighted assets (RWA) are used as an indicator).

When Euro area member states are pooled according to their individual credit ratings as of the end of the year 2015, two major blocks can be formed. Graph 4 shows that potential risks emanate to a larger extent from those countries that are rated below high grade (AAA or AA) as compared to their cumulated shares of Gross Domestic Product.

Graph 4

Sources: European Central Bank, European Commission, European Central Bank via Macrobond, own calculations

As a next step I will look at the amounts provided in cash and via guarantees or commitments by the indivi-dual member states to back the financing mechanisms GLF, EFSM, EFSF and ESM. The following graphs compile information for the exposure of Euro area countries in the context of mechanisms applied to provide crises financing to other Euro area countries. EFSM, which is not under scrutiny in detail, is looked at in this chapter as a special form of a financing mechanism backed entirely by gua-rantees purely for illustrative reasons. The figures differ

greatly for programme countries due to the stepping out option on the one hand and the new members of the Euro area on the other hand.

Graph 5a

*) relevant for national public debt according to Maastricht criteria as accounted for by Eurostat

ESM paid-in capital is relevant for gross public debt under the assumption that it is debt financed

Graph 5b

Sources: European Commission, ESM, EFSF, national stati-stics offices, own calculations

*) EFSM is backed by the EU-budget, thus by all 28 EU member states

Note that the figures for ESM include the entire authorised capital (thus also the unused amounts)

Chapter 4: Who contributes and how much?

20

Countries that entered the Euro area after GLF and EFSF were agreed did not retroactively become members of tho-se two financing arrangements, as both were only conside-red to be short-lived at the point of time of their creation. Only the EU budget and the ESM-Treaty foresee an option for countries to become new members of the mechanism. This option applies retroactively, i.e. new members are fully liable for exposure incurred before their membership. When again pooling the member states according to their individual credit ratings as of the end of the year 2015, two major blocks can be formed.

Graph 6

Sources: European Commission, ESM, EFSF, own calculations*) EFSM contribution keys are 5 year averages for the peri-od 2011-2015 for all 28 EU member states

The potential impact of the United Kingdom leaving the European Union is not reflected

Whereas those member states that were assigned with the highest credit ratings represent 62.3 % of Euro area GDP (cut-off date 31.12.2015 as compared to 61.5 % at the end of 2012), their share in the Solidarity measures ranges between 57.7 % for ESM and 62.3 % for EFSF (the Total measured as overall weighted average is 58.8 %). Note that the contribution keys for GLF and EFSF would have initially been closer or almost similar to the ESM figures but were retroactively elevated through the subsequent stepping-out of co-creditors or co-guarantors respectively (i.e. programme countries). In this context it needs to be recalled that for certain types of financial assistance it is not foreseen for beneficiaries to step out of guarantee framework (stepping-out ex-ante is by no means related to a subsequent potential Secondary Default of a co-guar-antor!). From a general point of view, it is hard to tell how large the shares to be taken over would be in a hypo-thetical future actual application of the mechanisms. The

following analysis will reflect on the numerous specifics of the financing mechanisms to the extent possible, while still remaining as broad as possible, based on experience made during the years 2010 to 2015. The different burden sharing agreements for GLF, EFSM, EFSF and ESM play a role for the question whether or not some form of credit enhancement is required for the financing arrangements, depending on the size and struc-ture of the guarantee or commitment framework.

If the contributions are pooled according to the underlying credit ratings and in addition compared to the targeted lending capacity, it can be seen in the following graph that the largest part of the first hit in a theoretical worst case, black-swan kind of scenario, in which most of the member states are unable to honour their commitments, will be taken by the highest rated member states.

Graph 7

Sources: European Commission, EFSF, ESM, own calculations*) EFSM is backed by the EU budget and thus by all 28 EU member states

ESM Paid-in capital is shared according to the ratios shown above in Graph 7. From this perspective some 9.4 % out of the 16 % displayed come from AAA/AA rated member states and the remaining roughly 6.6 % from lower rated member states. Thus the total share of AAA/AA countries is around 81.4 % of total hypothetical immediate maxi-mum loss absorption for ESM.

However, following the risk based approach outlined in Chapter 3 it will become clearer that this immediate maxi-mum risk will not materialize for higher rated member sta-tes with high probability (see Table 2). Given the prudent liquidity and funding strategy of EFSF and ESM, the risk of large concentrated calls on guarantees or callable capital is substantially lowered.

21

Table 2: AAA/AA countries’ share in the mechanisms considered under different perspectives

Mechanism Cash nom. Share*)

immediatefirst hit share**)

risk weightedshare***) Sovereign loans

risk weightedshare****) Banking related

rating based simulation based rating based simulation based

shares

GLF 100% 60.4% 61.4% 61.4% 61.4% 61.4% 61.4%

EFSM 0% 63.2% 63.2% 63.2% 63.2% 63.2% 63.2%

EFSF 0% 57.9% 100.0% 62.3% 62.5% 57.9% 58.1%

ESM 16% 57.7% 81.2% 57.7% 57.8% 57.7% 57.8%*) initial contribution key for AAA/AA countries in the pool without stepping out and potential default of co-

guarantors**) maximum share to be covered by AAA/AA countries ***) contribution keys for AAA/AA countries after stepping out of programme countries (historical values where

applicable) and default of some co-guarantors based on based on Standard and Poor’s standardised Probabilities of Default and own simulations (assumptions are built upon Standard and Poor’s rating table: assumed probabilitie for default is 14.6% for a sovereign loan)

****) assuming no stepping out

If a crises financing or risk sharing mechanism is ought to be assigned with a sufficiently high rating there will have to be some sort of credit enhancement, either in the form of paid-in cash or by way of providing over-guarantees or excess-commitment. Especially AAA/AA countries thus face a trade-off between (potentially uncovered) own funding costs on the one hand or (potentially higher) risk exposure due to higher regular contribution keys or higher over-gua-rantees or excess-commitment on the other hand. Establis-hing a fair contribution key is definitely not a clear cut and straightforward task, as it is depending on a number of assumptions and believes as well as relying on the purpose of the risk sharing measure in question. The revealed pre-ference of Euro area and European Union member states appears to anchor the individual contributions mostly to the economic strength of each member and not to the origin of risk.

22

In this chapter I will elaborate on potential options to improve the existing ex-post risk sharing framework in Europe against the background of the before mentioned lessons learned and the analysis of different funding and risk sharing structures as outlined in Chapters 2, 3 and 4.

Readers should be aware that none of the following policy options have been assessed regarding their legal and political feasibility in full detail. The author considers these proposals as potential elements for any form of future joint funding and risk sharing structure apart from any central form of Euro area or European budget, deposit insurance or alike. It should also be noted that the discussion does not reflect in detail upon issues such as incentive compa-tibility and the design of policy conditionality but focuses mostly on financing and risk sharing options.

i) Streamline the financial assistance architecture

ESM has taken over the tasks of the various temporary financial assistance financing arrangements GLF, EFSF and EFSM. However, due to the repeated alteration of terms and conditions and thereby extension of maturities, the temporariness of these mechanisms is as long as 45 years as of today.

Thus, in the Medium to long run ESM as the main institu-tion of the Euro area should take over EFSFs assets and liabilities to effectively become the sole provider of stability support. ESM could also do so for the same reasons with the bilateral loans of the Greek Loan Facility.

This merger, however difficult to implement, would serve several purposes. Firstly, it would integrate Euro area financial assistance under one roof. Secondly, it would free public balance sheets of creditor and guarantor coun-tries from debt incurred and rerouted to finance stability support. Thirdly, the concentration of financial assistance within the ESM would sprawl the burden to all current Euro area member states as a number of them are not party to the GLF and the EFSF. Furthermore, it would take away budgetary costs as the financing costs for the GLF for some member states might be higher than what is recei-ved in interest payments someday. Lastly, it would finally establish ESM as the single debt issuing body for the pur-

pose of financing stability support. The increased stock of ESM debt securities could lead to more liquidity for those bonds and thus potentially slightly lower funding costs.

The ESM as a crisis financing mechanism solely designed to support a limited number of members will by definition not become active very often but only during rare times of financial crises. In the presence of rather deep financial turmoil ESMs available resources might not be sufficient. For example, as a consequence of the deepening sover-eign debt crisis the Eurogroup decided, amongst others, to extend the joint EFSF/ESM-lending capacity from 500 to 700 billion Euros43. If ESM would take over existing financial assistance programmes and loans under GLF and/or EFSF, it could be argued that its capacity would need to be increased in order to have the necessary “fire power”. One of the options to temporarily increase the lending capacity of ESM would be to add a guarantee like structure to the ESM. This “inflation mode” could allow the ESM to borrow additional means in the market backed by additi-onal commitments of ESM member states under certain circumstances and potentially only for a limited amount of time (this proposal should be read against the background the analysis in Chapter 3).

This mechanism could be structured by way of mirro-ring EFSF type guarantees for the ESMs callable capital (authorised but not called) on top of the existing capital stock. The trigger for activating the inflation mode could be for instance that the Forward Commitment Capacity (FCC) falls below a certain threshold (say 20 to 30% of the overall capacity) or the FCC would no longer be sufficient to cover certain financing needs (for instance a potential Secondary Market Purchase Programme target level or the current size of the SRF if ESM were to provide a credit line to the SRM).

Further improvements to the ESMs capital structure to take into account the dynamics outlined in Chapter 3 on the risk implications of the different mechanisms to share risks or fund financial assistance measures could be warran-ted. Taking cash flow management’s, rating agencies’ and member states’ perspectives into consideration, it could make sense to apply different ratios of cash to guarantees/commitments for the specific purpose in question:

43 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/129381.pdf

Chapter 5: Proposals to improve the existing risk sharing framework in Europe

23

Exposure through sovereign loans to member states Exposure to the banking sector, either through invest-

ment in bank equity or potentially a future direct credit line to SRB

In addition to the existing ways to call on capital under Article 9 of the ESM-Treaty, shareholding member states could consider introducing contingent capital calls as well as a temporary capital increase:

A contingent capital call is a decision to call on au-thorised unpaid capital if certain conditions are met. It would improve the quality of a capital call under Article 9 (2) by adding legal certainty, basically making it a guarantee in economic terms.

Temporary capital could allow the ESM to call on authorised unpaid capital where needed to back cer-tain risks and return it to shareholding member states – once an operation has successfully been terminated – without limiting the overall capital ceiling.

Both options would improve the capital structure of the ESM, either if the institution were to temporarily extend its balance sheet or to invest in riskier assets such as bank equity under DRI.

In designing such a mechanism it would be of utmost importance to clarify how the structure would work, as the backing of ESMs debt issuance should not be altered in terms of quality and as ESM should not create a dual mar-ket for its bonds issued. Besides the legal implications, the question has to be discussed with Credit Rating Agencies how this would be reflected in the ESMs credit assess-ment. A potential way forward could be to strengthen the Forward Commitment Capacity framework in combination with the rules applicable to capital calls and make it more binding in order to clarify that ESMs bonds issued would at all times be backed by sufficient paid-in and callable capital.

ii) Improve risk sharing and risk mitigation among private and official sector

Risk sharing can be seen from two distinct perspectives in the context of this paper. One is on public risk sharing, so how member states share a certain burden amongst each other, whereas the other is on how to share risk between private investors and the public sector.

Regarding the first perspective, Chapter 4 provides an overview over the amounts at stake within the risk sharing mechanisms in place to tackle the Euro area sovereign debt crisis. The model presented in Chapter 3 analyses the

underlying dynamics. One means to go beyond the current understanding of sharing risks by using fixed contribu-tion keys would be to introduce asymmetric (temporary) capital calls, as a special case of temporary capital sug-gested under proposal i). Such an asymmetric call would ask a certain country to temporarily pay in more capital than its share would initially ask for. The clear benefit as compared with credit enhancement via over-guarantees or excess-commitment is that the overall exposure would be lower and that it would place risk mitigation measures at its origin. This mechanism could for instance serve the purpose to stabilize the ESMs overall credit rating if one countries’ credit worthiness is deteriorating. Such a measure would be temporary, until the credit rating of that country has improved again. Otherwise, it could help to set the right incentives for a country benefitting from a certain risk sharing measure. The member state in ques-tion would need to keep some skin in the game, if risks were shared via the ESM but control over the origin of the risk is at least partially national and not entirely within the joint reach of Euro area countries. Such a mechanism would work in a similar spirit as the agreement on burden sharing under Article 9 of the ESM Guideline on Financial Assistance for the Direct Recapitalisation of Institutions.

Regarding the perspective of risk sharing among the private and public sector, as discussed in Chapter 1, it should in general be the primary goal to limit exposure of public means to private risks to the extent possible. Amongst others, recital 13 of the ESM-Treaty foresees the option of private sector involvement in the context of full macroeconomic adjustment programmes in line with IMFs experience. Current discussions within the IMF go into the direction of required debt restructuring prior to IMF assistance44.

In the same spirit as the IMF, ESM should assess how debt could be made sustainable both through concessional lending at unconventional terms as well as through com-pulsory (in the medium to long run automatic) maturity extensions for debt held by private investors in the run-up of an ESM programme. This would aim at avoiding heavy refinancing needs during an ESM programme, reduce overall interest payments of a country due to concessional lending terms and reduce the net present value of debt. For financial stability reasons the focus however should lie with limited adjustments to the terms and conditions of debt, as the latest Euro area debt restructuring has amongst others effectively driven the banking sector of two Euro area countries into insolvency. Automatic re-pro-filing elements should thus only be enshrined into newly issued debt, for instance, based on general provisions as outlined in Article 12 (3) of the ESM-Treaty foreseeing the introduction of Collective-Action-Clauses into Euro area

44 For further information, see: http://www.imf.org/external/np/spr/2015/conc/index.htm and http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2015/040915.pdf

24

sovereign debt. A potential sweetener for such a scheme could be to trigger such clauses only for countries under an ESM macro-economic adjustment programme and only if needed to achieve certain debt sustainability targets, whereas net present value losses for holders of debt of a potential beneficiary country should remain limited. The latter could work by adjusting interest rates accordingly, by linking maturity extensions to higher coupon payments. Such a framework, however, has to ensure that provisions do not lead to self-fulfilling prophecies, amplify market panic and undesirable herding behaviour. Where debt is supposedly not sustainable with high certainty and a large share of means from an adjustment programme goes into refinancing of existing obligations, vast maturity exten-sions via very long lived ESM loans might turn out to be unavoidable after all. It appears to be most suitable to find some form of mixed burden sharing for those cases where private investors could chose to amend terms and conditions in line with ESM loans or accept nominal write offs for their claims. In parallel, ESM would shoulder the remaining burden through lengthy maturities, low inter-est rates and potentially further debt burden alleviating measures.

In the long run the equation should be simple. Excessive risk taking and debt accumulation by private investors should be solved in general via bail-in and restructuring. Where excessive private sector risk accumulation leads to systemic stress that can no longer be managed through such measures, risk sharing among member states should avoid fiscal distress of individual countries. Risk sharing measures should furthermore be limited to stretch credit risks by maturity transformation. Losses from private sec-tor risks should not be covered by public finances. Where losses from financial sector related activities cannot be avoided, member states should be reimbursed by collect-ing ex-post contributions from the banking sector.

However, in practice this will also mean that as long as banks’ risk exposure remains to a large or at least some extent geared to national factors, further risk mitigating measures that go into the direction outlined by the Eu-ropean Commission in the context of their proposal for a European Deposit Insurance Scheme would be required45.

iii) Streamline the financial stability architecture