M I R S R SI I S - Forgotten Books · johannes br ah ms, fet. 20 a p en ci l drawi ng du ne f ro m...

Transcript of M I R S R SI I S - Forgotten Books · johannes br ah ms, fet. 20 a p en ci l drawi ng du ne f ro m...

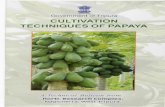

JOHANNES BRAHMS , fET. 20

A P E NC I L DRAW ING DU N E F ROM T H E L I F E I N 1 8 53 , AT DU ss ELDOR F , mv j. j. u. L A U R E N S ,uF MONT I'ELL I ER ( 1 80 1 T H E I 'OSSESS I U N O F F RAU P RO F E SSO R MAR IA lam E o r BuNN ,

WHnsE P E RM I SS I O N | T I S H E R E T H E O R IG I N A L m m wuxc H AS A N I NSCRH 'T I H N

LEcm LE N T H E REPRO DU CT ION ) Tu 'l‘

H E E F F ECT T H AT TH E DR AW I NG WAS DO N E ATscH U MANN

'

s R EQU E ST ; TH E A RT I ST'S N AM E 13 T H E R E S I 'HL ' I‘ ‘L A U R E NT ,’ AND T H E DAT E H A S

BE E N A L' I' EN ED TO 1 8 54

INTRODU CTORY NOTE ON

ENTHU SIASM

HE fol lowing pages a re certa in to inspire distrust

in the m inds of some readers because of their

enthusiastic tone. Now, although enthusiasm is no

longer considered a dangerous form of insanity, as i t

was in the eighteenth century, yet its presence is stil l

regarded as tending to obscure the judgment, a nd the

word conveys, whether intentionally or not,some idea of

a mood that is necessarily transitory. The lamp that is

trimmed gives the brightest a nd purest light, a nd the very

sound of“enthusiasm ” suggests some of the unpleasant

accompaniments of a n untrimmed wick. But is “en

thusia sm” rightly predicted ofall eulogy ? I s all eulogy

to be distrusted on the ground that no opinion ca n be at

once favourable a nd dispassionate ? One sees how absurd

the word sounds in regard to the supreme things ofthe

world in art a nd l iterature. Enthusiasm about the Bible,

Shakespeare, Dante,M ichel Angelo, or Beethoven savours

of a young ladies’ seminary, a nd in a grown-up person is

as unfitting on the one hand as impartial criticism

would be on the other, although in the days shortly

following the creation ofthe supreme things, enthusiasm

a nd impartiality were quite appropriately exhibited

vi BRAHMS

towards them . Surely a frame ofmind exists in which

admiration for the greatest things is unmixed with a ny

restless anxiety to discover flaws, a frame of mind free

from all feverish desire to gush ” over things which,having attained the position of classics, remain for the

world’s calm a nd steady delight. Perhaps the most recent

of the incontestably supreme things in the world ofmusic

to cal l forth a display of“ impartiality was the l ife-work

of Beethoven,upon whose death there were written

obituary notices which must amuse the modern critic,a nd should warn him against a timid excess ofcoolness.

The fact that the tone ofmany ofthe obituary notices of

Brahms was unwittingly couched in the same kind of

temperate” language would of itself suggest the idea

that that master’s work was destined to rank among the

great things of the world. I t may be wel l to make i t

clear that the fol lowing pages a re not written with a ny

desire to make unwilling converts, but to explain the

writer’s own personal conviction regarding the music of

Brahms. For him it has always been diffi cult to get into

the position of a person who finds Brahms puzzling or

crabbed ; from the date ofthe early performances ofthe

first sextet at the Popular Concerts the master’s ways of

expressing himself, his idioms, have always seemed the

most natural a nd gracious that could be conceived. Not

that a ny unusual degree ofmusical insight ca n be claimed,nor a ny desire felt to disguise the few occasions on which

passages have not been absolutely clear at a first hearing ;but it would be hardly honest to disarm criticism by

adopting a n artificial impartiality ” when the joy aroused

INTRODU CTORY NOTE ON ENTHUSIASM vu

by that first experience has spread a nd grown with nu

wavering steadiness for over thirty years, during which

each new work, as it appeared, has beeneagerly welcom ed

as a new revelation of a spirit already ardently loved. I t

may be remarked that on that first occas ion of encountering the name of Brahms on a concert programme, the

m usic was allowed to make its own impression. Musical ly

incl ined elders, anxious to train the young in the orthodox

ways, as orthodoxy was understood in the seventies, were

accustomed, with the best intentions, to cal l Handel sub

lime, Bach dry, Mozart shallow, a nd Mendelssohn sweet ;ofBeethoven they spoke in tones that reminded the child

ofSunday, tel ling him he could not expect to understand

it ti l l he wa s older, or to enjoy it til l much later thus, a ll

unconsciously, they damped for many years a ny ardour

he might have fel t for the great masters. But Brahms wa s

a new name a nd could not be “placed so that at once

a nd for ever afterwards he seemed to speak to the heart

with a rare directness, to use phrases that seemed to come

from the home of the soul, a nd to speak so intimately as

even to destroy a ny wish for personal communication with

the m a n lest that might perchance detract from the

eloquence of his music.

I . A. FU LLER-MAITLAND

CONTENTS

CRAP .BIOGRAPH ICAL

I I . BRAHMS AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES

I I I . CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BRAHMS

IV. THE P IANOFORTE WORKS

V. CONCERTED MUSIC

THE ORCHESTRAL WORKS

THE SONGS

VI I I . MU SIC FOR SOLO VOICES IN COMBINATION

THE CHORAL WORKS

L IST OF THE COMPOS ITIONS OF BRAHMS, ARRANGEDIN ORDER OF OPU S-NU MBER S

L IST OF F IRST LINES AND T ITLES OF VOCAL

COMPOSITIONS

INDEX

LI ST OF I LLU STRATlONS

JOHANNES BRAI—IMS, JET. 20

From a pencil drawing by J. J. B. Laurens. By perm ission of FranProfessor Ma ria Ba ie

BRAHMS AND REMENYIFACING PAGE

From a daguerreotype in the possessionofMr. Edward Speyer

BRAHMS IN H IS LIBRARY

From a photogra ph by Fra uPeninger

AUTOGRAPH LETTER FROM BRAHMS

BRAHMS MONU MENT AT VIENNABy perm issionofMessrs . Breitkopf and Ha rte)

BRAHMS AND JOACHIMFrom a photogr a ph

BRAHMS CONDUCTINGFrom a dra wing by Prof.W. von Beckora th

BRAHMS AT THE P IANOFrom a dra wing by Prof. W. va nBeckera th

BRAHMS CONDUCTINGFrom a drawing by Prof.W. van Beckera th

BRAHMS CONDUCTINGFrom a drawing by Prof.W. va nBeckera th

BRAHMS CONDUCTINGFrom a drawing by Prof.W. vonBeckera th

BRAHMS CONDUCTINGFrom a drawing by Prof.W. vonBeeqa th

AUTOGRAPH CANON BY BRAHMS .

Reproduced from I . A. Fuller-H a itlnnd’

s Ma stersby perm issionofMessrs . Ha rper 8; Bros.

XI

Germ a n Music

6

BR AHM S

CHAPTER I

BI OGRAP HI CAL

HE advanta ges of a n uneventfu l life, so obvious inthe case of the happy nations that have no

history, a re less patent in regard to artistic careers.Goethe’s “Wer nie seinBrod mit Thranen ass is one of

the most hackneyed quotations in existence, a nd is alwaysbrought forward to prove the great benefit resulting frompersonal affliction upon the minds of thosewho deal withthe arts. I t IS soeasy to showby its means that one m a n

must have been a n excel lent painter beca use he could not

get on with his wife, another a fine poet beca use hecommitted suicide, or that the operas of a third mustbe of excel lent quality because the composer forged abanknote. Had Beethoven been the uncle of a respectable nephew instead of a hopeless ne

’

er-do-weel, hadWagner prolonged his wedded life a nd not meddled with

pol i tics, had Schubert been rich instead of poor, hadHandel kept his eyesight, we may be sure that certainwriters of the present day would have been found toplace them , on this account, among the composers of

8 l

2 BRAHMS

whom Mendelssohn is the popular type, with his unfailingoutward prosperity a nd his frequent lapses from musicalgreatness. We may admit that the indigestible characterofmodern Russian food has had much to do with thepessimism of modernRussianmusic ; but the bread oftearsis seldom made offlour, a nd many a great m a n has eaten i twhose outward life seems to have passed in a n unruffied

calm, a nd whose biographer is at his wits’

end to findsome stain on his reputation, some skeleton in the cupboard to be brought forth as evidence ofhis close intimacywith the “heavenly powers.

” These skeletons do undoubtedly serve the purpose ofawakening interest in thework of the owners of their cupboards ; a nd the publicvogue of a m a n with whom scandal has been busy isnaturally greater than that ofone against whose conductnothing ca n be adduced. I f a man’s work declare itselfas ofsupreme quality throughout, a nd prove that he hasbeen “ commercing with the skies

,

”we a re surely per

m itted to regard him as a rare exception to Goethe’s rule,

or to admit the possibility that his sorrows may have beenreal enough, even though they were hidden from the

keenest human eye. A man’s creations a re far surerevidence of his emotional range than a ny l ist of socialupheavals, personal privations, or scandalous actions a nd

while those whose being vibrates to every characteristicmood of a musician’s art need no outside testimony to

his greatness, the less fortunate persons to whom that artis a sealed book a re not l ike ly to be convinced of itsimportance by a categorical account of the sorrows themusician endured.

Such a n outwardly uneventful l ife was that of JohannesBrahms, a nd it is only necessary to give a rapid summaryofthe main facts, pointing out the few incidents which

4 BRAHMS

Norm a fantasia, a nd at the second a duet by the same

popular virtuoso with F rau Meyer-David, the concertgiver. Nearly a year afterwards, on 2 1 September, 1848,he gave a concert ofhis own, a t which he played a fugue

ofBach, besides other things more suited to the taste of

that day. On 14 April, 1 849, he gave another concert,playing the “Waldstein ” sonata of Beethoven, some

popular pieces, a nd a fantasia by himself“on a favourite

waltz.

”After this formal opening ofhis career as a n

executant, he had to endure the drudgery of playingnight after night in dancing saloons. During the nextfive years his l ife must have been a hard one, a nd

perhaps some of the necessary brea d oftears was eatenat this time. Various small engagements, one ofwhichwas that ofaccompanist behind the scenes ofthe StadtTheater

,a nd teaching (at the high fee ofabout a shil l ing

a lesson) occupied him, a nd in his spare time he readvoraciously, poetry turning itself, half consciously, intomusic in his brain. Many songs were composed at this

period of his life, when he was compel led, like Wagner,to do hack-work for publishers in the way ofarrangementsa nd transcriptions, operatic a nd otherwise ; these werepublished under the pseudonym of“ G. W. Marks, a nd

it would seem as though another nom de plum e,

“KarlWiirth, was kept for work ofa more ambitious kind

,such

as duet for piano a nd Violoncel lo, a nd a trio for pianoa nd strings, which were played at a private concert on

5 July, 1851 , a nd duly announced on the programme asthe work of Karl Wiirth ” a copy of the programme isstil l in existence on which Brahms has substituted inpencil his true name for the other.Not till 1853 did a brighter day dawn for the com

poser. A certain viol inist named Rem ényi, whose real

BI OGRAPHI CAL 5

name was Hoffmann, a nd who was ofa mixed German,Hungarian, a nd Jewish origin, had appeared in Hamburgas early as 1849, ostensibly on his way to America withother Hungarian refugees. He found the “ farewel lconcert as profitable as numberless English artists havefound it at various times, a nd after the departure ofhiscompatriots for the U nited States he still l ingered on in

Hamburg until 18 51 . He then seems to have gone toAmerica for a time, but he reappeared, at first in Paris, in1 852 , a nd at Hamburg again in the winter of 1852—3.

I t was arranged that Brahms should act as his aecom

pa nist at three concerts, at Winsen, L iineburg, a nd Cel le,a nd finally should proceed thence to Hanover, whereJoachim was court concertmeister leader of the

band), a nd assistant capellmeister (conductor), havinggiven up his position as leader ofthe opera orchestra .

The number ofconcerts was extended to about seven inall, at which the same programme was gone through bythe two performers. Beethoven’s sonata in C minor fromOp. 30 was the most important composition performed.

At Cel le, where the only decent piano was a semitone too

low for the viol inist’s convenience, Brahms undertook to

play the sonata in C sharp minor, at a moment’s notice.

Rem ényi was not a great artist, a nd would be ofsmallimportance in the career of Brahms if he had not

happened to beslightly acquainted with Joachim.

The meeting between Joachim a nd Brahms, which was

the beginning of a lifelong a nd most fruitful intimacy,took place at Joachim

’s rooms in H a nover,I a nd it was

obvious to the older m a n that Brahms was no ordinarymusician. In the oration pronounced by Joachim at

the dedication of the Brahms monument at Meiningen,

See Miss Ma y’s Life, i. 106, note.

6 BRAHMS

7 October, 1899, this first meeting is thus referred to

I t was a revelation to m e when the song 0 versm k’

struck my ears. And his piano-playing besides was so

tender, so full offancy, so free, so fiery, that it held m e

enthralled . After hearing such compositions as the youngcomposer had brought with him,

which included variousmovements of sonatas, the scherzo Op. 4, a sonata for

piano a nd viol in, a trio, a nd a string quartet, beside severalsongs

,Joachim saw plainly that the association with a

performer of R em ényi’

s stamp was not l ikely to be alasting one, a nd he invited Brahms to visit him at

Gottingen (where he— Joachim— was about to attendlectures) in the event of his tiring of his present post.There was some discussion between the two as tothe order in which it would be advisable to publishBrahms’s early com positions .

I At the time Joachimcould do no more than give Brahms a letter ofintroduction to L iszt, as the pair of players intended to go to

Weimar. The account ofthe interview with L iszt, givenby Wi l liam Mason,

who was present, may be read inM iss May’s L ife.

2 That L iszt played at sight the scherzoa nd approved of its style, is the one fact that is reallyimportant ; it is curious to read that after R aff haddetected its (very obvious) l ikeness to Chopin

’s pieces inthe same form ,

Brahms assured a friend that he had noknowledge whatever ofthe Polish master’s scherzos . The

reception ofthe two players by L iszt was of the mostcordial, a nd they found, what so many others found beforea nd afterwards, a n atmosphere offlattering appreciation,practical kindness, a nd surroundings which could not butappeal to a ny ardent a nd artistic soul. I t was L iszt’s wayto express to the full all the admiration he fel t, but on

See thejoa c/n'

m Correspondence, i. 10 - 12 .

2 Vol. i. 1 10 .

BIOGRAPHICAL 7

this occasion a letter ofhis to Bulow I proves that hereally thought highly of the C major sonata. For Six 2

w eeks the fellow-travel lers stayed at Weimar, but

gradually it became clear to Brahms at least that the spel lofArmida’s garden must be resisted, a nd every nightwhen he went to bed he resolved to cut the visit short,but every morning a new enchantment seemed to be putupon him, a nd he stayed. The charm was broken almostas effectually as that ofVenus in Ta nn/zd

’

user , but in a lesspoetical manner. Wi l l iam Mason tel ls us in his M em or ies

qfa Musica l L ife that L iszt was on one occasion playinghis beloved sonata in B minor, a nd

,glancing round at

a very expressive moment ofthe piece, saw that Brahmswas slumbering peaceful ly ; the composer stopped abruptly

a nd left the room . The figure of R em ényi goes out

of the story ; his po l itical a nd musical proclivitiescontinued to appeal to L iszt, a nd in the year after hewas made viol inist to Queen V ictoria. Although armedwith Joachim ’s letter, Brahms hesitated for some l ittletime before presenting himself to Schumann at Diisseldorf.

Steeped in the classical traditions he had learnt from

Marxsen,he had been almost deaf to the appeal of

Schumann’s music, for which a great friend, Fra uleinLouise

Japha,had unbounded admiration. Brahms had sent

Schumann a number ofhis early compositions in 18 50 ,

when Schumann was at Hamburg ; but the o lder masterwas then too busy to Open the parcel. When he didmake up his mind to go over from Mehlem , where he hadbeen staying almost ever since his departure from Weimar,he was welcomed at once by the Schumanns,whose ex pec

ta tions had been aroused by Joachim . When Brahms sat

F r a nz Liszt, von Julius Ka pp, p. 2 8 1 .

2 According to Ka pp, p. 2 80 Ka lbeck sa ys the tim e wa s three weeks .

8 BRAHMS

down to the piano to play one of his compositions to

Schumann, the latter interrupted him with the words,Clara must hear this,

”a nd he told his wife, when she

came into the room ,Here, dear Clara, you will hear such

m usic as younever heard before now, begin again, young

m a n '” They kept Brahms to dinner, a nd received him

into their intim a cy.

I To Joachim Schumann wrote the

memorable words, This is he that should come” —words

which,with the equally fam ous article, New Ba knen,

claimed for Brahms a place in the royal succession of

the great German composers. The article was al l themore powerful since Schumann broke in i t his four years’

silence as a critic. I t was not a n altogether unqualifiedbenefit to Brahms, seeing that it naturally aroused muchantagonism both among the many musicians who did not

yet know Brahms’s compositions, a nd also among the few

who, knowing them,did not l ike them . In October,

1 853, Brahms collaborated with Schumann a nd AlbertDietrich in the composition of a sonata for piano a nd

viol in as a present ofwelcome to Joachim , who visitedDusseldorf. The first movement, by Dietrich, a nd the

intermezzo a nd finale by Schumann, have not been published, as Joachim, who possessed the autograph

, con

sidered the latter master’s contribution not to be quiteworthy of him, a nd to Show signs ofthe mental ailmentwhich was so soon to overshadow him ; but he gave permission for the publication, after Brahms

’s death, ofthe

scherzo in C minor, which was the youngest man’s share.

Later in the same year came a visit to Leipzig, a nd a n

appearance at the Gewandhaus, at one ofDavid ’s quartetconcerts, in which Brahms played his own C ma jor sonata

Dr. A. Schubring’s Schum a nm

'

a na , quoted by Ka lbeck, [Ma nner

Bra hm s,-i. 12 1 .

I O BRAHMS

felt that,standing as he had done in a relation of peculiar

intimacy with Schumann, he could not enter as a candidate

for the post,which was given to Julius Tausch indue course.

In 18 56, after Schumann’s death, Brahms arranged to

rel ieve Madame Schumann ofsome ofthe lessons she wasengaged to give, a nd among the pupils was a F ra uleinLauravon Meysenbug, whose father a nd brother were officials atthe court ofL ippe-Detmold

,a nd whose mother was a n a c

compl ished amateur pianist. P rincess Friederike ofL ippe

Detmo ld was another ofMadame Schumann’s pupils, a nd

in consequence ofthe connection thus formed,Brahms wasoffered a kind of informal appo intment at the court of

Detmold,where he was to conduct a choral society recentlyre-organized

, to perform at the court concerts, a nd to con

tinue the P rincess’s musical education. H is duties onlylasted through the winter season, from September to

December, a nd he gained much useful experience as aconductor during the two years ofhis engagement at thecourt

,which he retained until January, 1860 . About this

time he made the acquaintance ofa young GOttingen lady,F rauleinAgathe von S iebold,with whom he seems to havefallen in love there a re various signs that it was a serious

passion on his part, but worldly considerations made amarriage out of the question, a nd the fact that in hisG major sextet there occurs this theme in the first movement is the most important record ofthe episode.

1L

In 18 59 the first performance of the D minorconcerto for pianoforte, with the composer in the so lo

See Litzm ann’s Cla ra Sel mm a m z, iii. 70 .

BI OGRAPHI CAL 1 1

part, took place at Hanover, Leipzig, and Hamburg,

being received at the first two very coldly. At the

Gewandhaus of Leipzig its reception was distinctlyunfavourable but Brahms took his repulse phIIOSOphica lly,a nd in a letter to Joachim (who had conducted it atHanover) he says :

“ I bel ieve it is the best thing thatcould happen to m e ; for it compels one to order one’sthoughts a nd to pluck up courage for the future.

”

I t is perhaps significant that the loudest notes of

disapproval were from the extreme classicists ofLeipzigthe partisans of the new school ofWeimar found more init to praise, a nd it is greatly to their credit that they hadthe courage to say so. I t has been suggested tha t this

praise was bestowed as part ofa del iberate plan to get

ho ld ofBrahms’s allegiance to thenew school a nd its tenetsbut whether it was so or not, the event showed that hisdevotion to the classical models had undergone no change.

Brahms’s position in regard to the new school was settledonce for al l by a n awkward accident. In 1860 , it hadbeen given out in the New Zez

'

tscizrg'

ft fz'

e'

r Musz’

k, the

organ of the new school, that al l the most prominentmusicians of the day were in favour of the “ musicof the future, as i t was cal led. Brahms fel t it to

be his duty to protest against this falsehood, a nd con

sented to Sign a document expressing disapproval ofthehigh-handed a nd who l ly gratuitous assumption ; the

E rkla'

m ng seems to have been written by Joachim a nd

Bernhard Scholz, a nd a great number of influential

m usicians undertook to subscribe it, but while it wasactually going round for

.

signatures, a version of it got intoprint in the Berlin Eeko, with only four names appended

to it that those of Brahms a nd Joachim were among the

Seeja de/rim Correspondence, i. 227-9.

1 2 BRAHMS

four was, of course, not forgotten nor forgiven by the

Weimar partisans.t

The text of the famous “Declaration may be thus

translated

The undersigned have for some time fol lowed withregret the course pursued by a certain party, whose organ

i s Brendel’s Zez'

tscizrzfi fur M a sz'

k.

The said Zez’

tscbrzft gives wide publicity to the opinion

that musicians ofearnest aims a re in agreement with thetendencies followed by the paper, a nd recognize in the

compositions of the leaders of the movement works of

artistic value, a nd that the dispute as to the so-called“ Music of the Future has been already fought out,

particularly in North Germany, a nd decided in favour of

the movement.The undersigned consider it their duty to protest

against such a misstatement of facts, a nd to declare fortheir part at least that they do not recognize the principlesexpressed in Brendel

’s Z a nd that they ca n onlybewail or condemn, as against the inmost a nd essentialnature ofmusic, the productions ofthe leaders a nd pupilsofthe so-called “ New German ” school

,which on the one

hand give practical expression to these principles, a nd on

the other necessitate the establishm ent ofnew a nd un

heard-oftheories .

JOHANNES BRAHMS.

JOSEPH JOACH IM .

JU L I U S OTTO GR IMM.

BERNHARD SCHOLZ.

On the whole ’question of the letter, a nd Bra hm s’s a ttitude towa rds

it, see the joa clzz'

m Cor respondence, i. 257, 268—9, 2 74 , 279. Also

Ka lbeck, i. cha p. x.

BIOGRAPHICAL 13

This wa s accompanied by the fol lowing letter to thosewho were invited to add their names

We feel that all to whom this is presented for signaturemay wish to add much to this declaration ; as we believethat each of them is in perfect agreement with the senseof the foregoing, we beg them earnestly to reflect on the

importance ofnot putting aside the protest, a nd we havetherefore tried to sim pl ify the above document sent forsignature. In case you a re willing to associate yourselfwith us, we ask you to send in this page, duly signed, toHerr Johannes Brahms, Hohe Fuhlentwiete 74, Hamburg.The declaration with the names in alphabetical order wil lbe published in the musical periodicals.

s e a éove signa tories.

I t is obvious that every additional name would haveadded greatly to the effect ofthis document, which may ormay not have been a very politic one but with only fournames, although these included two ofthe most prominentof the German classicists, it could not but excite derision,a nd foster the inimical feel ings ofthe m en at whom itwas directed. I t was, as we ca n all see now, a n ex

pedient of no practical util ity whatever ; but there a re

moments when i t is beyond human power to resist thetemptation to nail to the counter such lies as had beenuttered in the newspaper. Music, surely more than the

other arts, has been l iable to these outbursts of personalfeel ing, a nd every artistic revolution in its history mustha ve stirred up recriminations ofone kind or another.Happily we do not know exactly in what terms Palestrina a nd the masters of the polyphonic school of thesixteenth century were attacked by the m en who strovefor some new means of expression. We know a good

14 BRAHMS

deal more about the war ofthe Gluckists a nd P iccinnists

in Paris,a nd more stil l about the silly rivalry between

popular Singers in the period of Hande lian Operas in

London. In Germany the lovers of music a re alwayscuriously a pt to take s ides a nd split into two opposingparties, a nd it is easy to see that in many cases there

is a good deal of reason on both sides. The classical

party, whether itself creative or not, must feel responsiblefor the handing down of a great tradition in its purity,a nd that it should exaggerate the iconoclastic intentionsofthe other side is perhaps inevitable the party identifiedw ith tendencies that a re new will, of course, secure theapproval ofthe majority ; a nd, while always ready enoughto pose as martyrs for truths that have been revealed to

them alone, will as certainly minimize a ny originalitywhich the works ofthe classicists may display. We knownow that the “Declaration” was not a protest by hidebound pedants against all the modern tendencies, butwas really directed a gainst special heresies which weretraced in some of L iszt’s Symphonic Poems . Brahms,as appears from his correspondence with Joa chim ,

I was

particularly anxious not to include the music ofWagnerin his condemnation of the modern tendencies

, a nd itmust not be forgotten that the friends did not take the

initiative in the matter, but were bound to traverse the im

plied statement that al l the eminent musicians ofGermanywere on the one S ide. While we know that the classicalforms seemed to him sacred

, yet on occasion he foundit expedient to modify them in var ious ways

, not froma ny poverty ofhis own ideas

,but as it were to encour

a ge the natural development ofa living organism . The

new school,”for whose thoughts the older forms were

i. 274 .

B IOGRAPHI CAL I 5

too scanty or too strictly defined, did, after al l , verylittle indeed towards a ny really fruitful development ofmusical form, a nd it is hard to get rid of the suspicionthat the older forms were thrown aside by their leaderon account of the easily recognized difficulties they

present to one whose musical ideas a re virtually without distinction. I t is idle to guess what m ight have beenthe state ofmusical parties in Germany at the presentday if the Weimar schoo l had confined themselves tothe accurate statement that a large number ofmusicianshad embraced their principles ; but i t is hardly probablethat a ny degree ofpersonal or artistic intimacy could everhave endured between m en whose constitutional modestymade them hate all that was tawdry, a nd those to whom

the adulation ofa large public was as the breath of theirnostri ls, a nd who cared little for the real merits oftheirmusic as long as it was l ikely to surprise or tickle the

ears of thei r audiences.

L iszt’s admirable breadth of view, his boundlessgenerosity towards musicians of every kind

,a nd his sur

passing genius as a n executant, must have counted for verymuch in his own day ; but there is no gainsaying the

fact that adoption ofhis methods ofcomposition a nd of

artistic ideals based upon his, has brought German m usicinto a most singular state at the present time. I t is clearthat Brendel himself thought he had gone rather toofa r in support ofthe Weimar clique ; for he afterwardsal lowed Schubring to express his convictions that Brahmswas one ofthe giants ofmusic, a m a n on the level ofBach

,

Beethoven, a nd Schumann, a nd had to make his peacewith the “

new composers as best he might in a“ hedging a rticle,

I in which he makes a somewhatludicrous attempt to run with the hare a nd hunt with the

Ka lbeck , i. 490 .

16 BRAHM

hounds. The extraordinary warmth of feel ing exhibitedby the new school after the “Declaration a nd after the

memorable letter written by Joachim to L iszt has been,no doubt rightly, ascribed to the great influence wieldedby Joachim , a nd in a lesser degree by Brahms. Had the

New Schoo l ” realized how many a nd how influentialwere the names that would have appeared below the“Declaration if its appearance had not been forestalled,it is at least possible that their resentment would not havebeen so exclusively against Brahms a nd Joachim a nd itis even possible that Wagner’s famous jua

’entlzum in der

Muszlé , the pamphlet which rendered a ny idea ofreconciliation for ever impossible, might never have been written.

The names of those who had promised to support the“Declaration a re referred to in the letters betweenJoachima nd Brahms, but it does not appear that they were made

in a ny way public before the issue of the correspondencein 190 8 .

At Hamburg Brahms was busily a nd congenial ly occu

pied as conductor of a choir of ladies, on whose behalfhe wrote the various sacred a nd secular works for femalevoices which a re so numerous among his early opusnumbers. Many more were written, but were burnt bythe composer, all but a single part (second soprano), inwhich Ka lbeck discovered the germs of several matureworks 2 The cho ir was developed from the fortuitousassociation of some ladies in the music arranged byGradener for the marriage ofa pastor named Sengelm a nn

with a F raulein Jenny von Ahsen. Brahms played theorgan at the ceremony, a nd Gradener composed a motetfor female voices, the effect ofwhich was so good, that

Moser’

sjoseplzjoa efiim , p. 151 . English tra nsla tion, p. 167.

i. pp. 277, 386.

18 BRAHMS

fiuz'

ret, gesungen werden durfte, als mochte es noch a n der

Zeit sein dieses Opus a n das Tageslicht zu stel len.

P ro prim o w'

a re zu rem a rquiren dass die Mitgliederdes F r a uenchors d a sein m iissen.

“ Als wird verstanden ; dass sie sich oélzgireu sol len,den Stehungen und Singungen der Societa t regelm a ssig

beizuwohnen.

So nun Jemand diesenArticul nicht gehorig observiretund, wo Gott fiir sei, der Fal l pa ssirete, dass Jemand widerjedesDecorum so fehlete, dass er wahrend einesExercitium s

ganz fehletesol l gestraft werden mit einer Busse von 8 Schill ingen

H C (Hamburger Courant).P ro secuua

’o ist zu beachten, dass die Mitglieder des

F rauenchors d a sein m iissen.

“AIS ist zunehmen, Sie sollenpra ecise zur anberaumtenZeit da sein.

Wer nun hiewieder also sundiget, dass er das ganzeViertheil einer Stunde zu sp

'

a t der Societa t seine schuldigeR everentz und Aufwartung machet, 5 0 11 um 2 SchillingeH.C. gestra fet werden.

I hrer grossenM eriten um denF ra uenchor wegen undin Betracht ihrer verm uthlich hochst mangelhaften und

ungliicklichen Complexion, so l l nun hier fiir die nichtgenug zu fa vorireua

’e und a a

’

orireua ’e Dem oiselle L a ura

Ga rbe ein Abom zem eut hergestellt werden, wesm a ssen sie

nicht jedesmal zu bezahlen braucht, sondern aber ihro a m

Schluss des Quartals eine m oderirte Rechnung praesentiret wird )

P ro ter tio : Da s einkom m ende Geld mag denenBettel leuten gegeben werden und wird gewiinscht, dassN iemand davon gesa ttiget werden m Oge.

P roqua rto ist zumerken, dass dieMusika lieugrossen

BI OGRAPHI CAL 19

theils der Discretion der Da m es a nvertrauet sind . Derohalben sol len sie wie fremdes E igenthum von den ehr und

tugendsamen Jungfrauenund F rauen in rechter L ieb undaller H iibschheit gehalten werden, auch in keinerlei Weiseausserhalb der Socz

'

eta'

t werden.

“ P ro guirzto : Wa s nicht mit Singen kann, das sehenwir als ein Neutrum a n. Wi l l heissen : ZuhOrer werdengeduldet indessen aber pro or a

’ina rio beachtet, was Gestalt

sonsten die rechte Nutzbarkei t der Exera'

tia nicht bescha ffet werden m Ochte.

Obgem eldeter gehorig spea fi zirter Erlass wird durch

gegenwa rtiges Genera l-R escript a njetzo jeder m anniglich

public gemacht und $0 11 in Wiirden gehalten werden, bisder F ra ueuc/zor seine Endscha ft erreichet hat.

“ Sol l test du nun nicht nur vor dich ohnverbruchlich

darob halten,sondern auch alles Ernstes daran sein, dass

andere a ufkeinerlei Weise nochWege da rwider thun nochhandeln m Ogen.

An dem beschiehet U nsere Meinung und erwarte a ero

gewiinschte und wohlgewogene Approba ti'

on.

Der ich verharre in tiefster Devotion und Vener a tion

des F rauenchors allzeit dienstbeflissener schreibfertiger

und taktfester

JOHANNES KRE I SLER , JU N.,

a lia s : BRAHMS

Geben aufMontag,den 3oten. des Moua ts Aprili.

“A.D.

I t is far from easy to convey the exact meaning ofthe

quaint old-world language, a nd to render it by a ny adequate

The words in ita lics a ppea r in Rom an type in Ka lbeck’

s Life, the rest

being in Germ a n cha ra cter.

20 BRAHMS

English equivalent seems quite impossible ; the followingtranslation aims at nothing more than giving the general

drift of the document

AVERTIMENTO

Inasmuch as it is a nundoubted enhancement of pleasure

that it should be wel l-regulated a nd in order, it is herebydecla red a nd made plain to those inquiring spirits whowish to become members of the very useful and lovelyLa dies’ Choir, that they must sign the whole of the clausesa nd periods of the here-following script, before they ca n

enjoy the above title a nd ta ke part in the musical enjoyment a nd diversion.

I ought to have got the thing started before now,I but

(from) the advent oflovely spring until the end ofsummer,

is a season proclaimed as the most fitting for singing, a ndthe time is ripe for the execution ofthe scheme.

In the first place, it is to be noticed that the membersof the Ladies’ Choir a re to be t h e r e .

That is to say : they shall undertake to attend regularlythe meetings a nd practices ofthe Society.

Ifa ny one shall not observe this condition, a nd if thecase should happen (which Heaven forfend that a ny one

Should so err against decorum as to miss a whole practice

I The m ea ning of the phra se unter der Ba nk wischen is clea rly,“ to

sweep under the bench,”but it is difficult to be sure inwha t sense the phra se

is used. On the one ha nd, it ha s been suggested tha t it refers (a s a phra se

usua l inHa m burg houses ) to the periodical Spring clea ning,” but it is m ore

proba ble (considering the lega l cha ra cter ofthe whole docum ent) tha t the“ Ba nk referred to is the “ lange Ba nk,” or shelf, on which deeds werepla ced in rows, those not im m edia tely wa nted being pushed a long it, so tha t

to shove anything a long the long shelf”m ea ns to postpone it indefinitely.

Conversely, inthe a bove, I should ha ve swept it out from under the shelf”

m a y bea r the m eaning suggested in the text, but the genera l gist ofthe pa ra

gra ph is clea rly to confine the chora l pra ctices to the spring a nd sum m er.

BI OGRAPHI CAL 2 1

she shall be m ulcted in a fine of 8 shill ings

(Hamburg currency) .In the second place, i t is to be noticed, that themembers

of the L adies’ Choir a re to be t h e r e .

That is to say,they shall be punctual to the appointed

time.

Ifa ny one so transgresses as to be a whole quarter ofa n hour too late in paying his due respect a nd attendanceto the Society, he shall be fined 2 shillings (Hamburgcurrency).

(On account ofher great merit in regard to the choir,a nd in respect ofher probably highly faul ty a nd unfortunate [del icacy of]constitution, a subscription shall be gotup for the never-enough-to—be-favoured-a nd-adored Dem oi

sel le Laura Garbe, so that she need not pay every time [that

she is absent or late], but that a reduced account shall bepresented to her at the end ofthe quarter.)

In the third place, the money so col lected may be given

to the poor, a nd i t is hoped that none ofthem will be sur

feited therewith .

In the fourth place, i t is to be noticed, that the musicis for the most part confided to the discretionofthe ladies.Therefore the honourable a nd virtuous ladies, married orsingle, shall preserve i t neatly a nd fairly, l ike the property

ofsome one else, a nd it is by no means to go outside

the so ciety.

In the fifth place : Whatsoever cannot sing with us, weregard as ofthe neuter gender. That is to say, L isteners

a re tolerated, only so far as they do nothing that couldinterfere with the practical utility ofthe practices.

The above permission is definitely made by the presentdocument, a nd shall be observed by each a nd all of the

public,until the Ladies’ Choir shal l come to a n end.

2 2 BRAHMS

Yousha l l not only comply with this without fail, butshall do your best endeavour to prevent others from

disobeying the rules.To whom our decisions a re submitted [P]a nd whose

desired a nd wel l-weighed approval is awaited in deepestdevotion a nd veneration ; by the Ladies

’ Choir’s diligent

ready-writer a nd time-beater,

JOHANNES KRE I SLER , JU N.,

a lia s BRAHMS

I t is not surprising to hear that the joke about

Demo iselle Garbe a nd her frequent unpunctuality was

not especially pleasing to the poor lady, who consultedF rau Schumann about it. That lady, who was one of

those who signed the document as being a member oftheLadies’ Choir, pointed out that in such a document as thisher name would be handed down to posterity. I t all seemsa little childish, a nd the whole business ofthe rules has, ofcourse, lost a good deal of what point it ever had, but itseems worth preserving for its quaint phraseology. F rau

Schumann’s presence in Hamburg at the date of the document is denied by M iss Ma y,

I but Ka lbeck says that Sheplayed on 20 Apri l, ten days before the above date, ata concert of Otten’s Musical Society, at which Brahmsrepeated the so lo part in his il l-fated concerto. I t wasawkwardly placed in the programme, a nd the reception of

the first movement was so unfavourable that the composer

got up a nd whispered to Otten, the conductor, that hemust decline to go on with the work. Happily Ottenpersuaded him to finish it. The episode has nothing ini tself remarkable, but in regard to the failure of this work .

here a nd in Leipzig, we a re in danger of forgetting that

L ife, i. 254 .

BI OGRAPHI CAL 2 3

Brahms’s stoical manner was only assumed, a nd here wesee how sorely he fel t the attitude ofthe public. I t mayor may not have had to do with the composer

’s slowlyformed determination to go a nd l ive inVienna, which hevisited in 1862 , apparently meaning to remain only a shorttime.

The migration from Hamburg a nd the ultimate adoption ofVienna as a home, is generally a nd convenientlyheld to mark the principal division in the outward careerofBrahms. An appointment to the conductorship of theVienna S ingakademie was perhaps the immediate cause of

the change of abode, a nd although the oflice was onlyretained for a year or two, yet, by the time Brahms gave itup, Vienna had become so attractive to him that he madeit his head-quarters for the rest ofhis life. The conceptiona nd completion ofhis great Deutsc/zes R equiem occupiedhim chiefly for the next five years or so. Not that hislabours in other fields were unimportant, for the com

positions ofthe early Viennese period include his two mostexacting pianoforte so los, the Handel a nd Paganini ”

variations,the two quartets for piano a nd strings, Opp. 2 5

a nd 26, the quintet in F minor, Op. 34 , the M ageloue

romances, a nd many other vocal works. I t is, happily,unnecessary for the ordinary lover ofBrahms’s R equiem to

settle definitely whether it was intended to enshrine the

memory ofthe composer’s mother (a theory supported by

the disposition of the fifth section,the famous soprano solo

a nd chorus, a nd by the direct testimony of Joachim a nd

other friends), or whether it was, as strenuously argued byHerr Ka lbeck, suggested by the tragedy of Schumann

’send. Possibly both a re in a measure true ; the composermay have been first led to meditate on death a nd itsproblems by the death ofSchumann— the first deep per

24 BRAHMS

sonal sorrow he ca n have known— but we know that inchronological sequence its composition followed his ownprivate loss. F rau Brahms died in 1865, a nd the R equiemwas completed in 1868 by the addition of the numberalready referred to. Before the performance of the firstthree numbers the widower had married again, a ndthere a re few things more beautiful in Brahms’s l ife thanhis conduct to his stepmother, over whose interests, a ndthose ofher son by a former marriage, F ritz Schnack, hewatched with rare loyalty. H is father died in 1872 , F rauCaroline Brahms surviving her i l lustrious stepson by fiveyears. About the period ofthe R equiem , or rather later,came several other works in which a chorus takes part,such as R ina ldo, for male voices, a nd three ofthe noblestchoral compositions in existence : the R itapsoa

’ie, for con

tra lto solo, male choir, a nd orchestra ; the Schicksa lsliea’

a nd Triumplzliea'

,the last, in eight parts,with solo for bass,

in commemoration ofthe German victories in the war of1 870—1 . For three seasons, 1872—5, Brahms was con

ductor ofthe concerts ofthe Gesel lschaft der Musikfreunde,a nd the programmes ofthe period given inM iss May

’s L ifea re enough to fi l l us with envy. During this time hismusic was continually advancing in popularity, a nd the

great public ofVienna was conquered by the remarkable

performance ofthe R equiem there on 2 8 February,1875.

This new attitude ofthe public gave the cue to the rest ofthe world, a nd during a tour in Hol land in 1876 even theD minor concerto roused enthusiasm when the composer

played it at U trecht. The“Haydn variations for orchestra

were given in various musical centres, always with greatsuccess, but it was the first symphony, in C minor, thatstamped Brahms as the legitimate representative ofthe greatdynasty ofGerman composers. I t had been long expected ;

BIOGRAPHICAL 2 5

for the musical world must have realized that the m a nwhocould show himsel f so great a master of thematic development as Brahms had done in many chamber compositions

(the last of which were the three string quartets, Opp. 51a nd 67, a nd the quartet for piano a nd strings

,Op. a nd

who could handle the orchestra so skilfully as he hadhandled it in the Haydn variations, could give the

world a new symphonic masterpiece. As such the workin C minor could hardly be universally accepted at onceif it had not stirred up opposition a nd discussion, its realimportance might wel l have been questioned, but by thistime Brahms himself most probably cared but little for theopinions of friendly or adverse critics, although his warmheart was always appreciative of the enthusiasm of hisintimate friends ; a nd the verdict ofsuch people as Joachima nd F rau von Herzogenberg was always eagerly awaitedby him . Inmany cases their criticisms were followed, a ndalterations made in deference to them . The first symphonyis one of the great landmarks in the history of Brahms’spopularity in England ; for when i t was quite new the

U niversity ofCambridge offered to the composer a nd to

Joachim the honorary degree ofMus .D., which cannot begranted in a bsentia . Joachim would in a ny case be inEngland, a nd Brahms hesitated for some time whether toaccept the invitation, but finally refused it in consequenceof the publicationofa premature announcement concerninghis appearance at the Crystal P alace. He acknowledgedthe compliment of the U niversity by allowing the firstEnglish performance ofthe new symphony to take placeat a concert given by the Cambridge U niversity Musical

Society on8 March, 1877, a nd i t was conducted by Joachim,

who contributed his own Eleg ia c Overture, conducting i thimsel f, a nd playing the solo part ofBeethoven

’s concerto.

Autograph letter from Brahms to a correspondentunknown (but not impossibly Sir George Grove), relatingto the death of C. F . Pohl, the biographer ofHaydn,who died in Vienna in April, 1887. Facsimile includedby kind permission of the Brahms-Gesellschaft, a nd

ofW. Barclay Squire, Esq., the owner of the originalletter.

TRANSLATION

DEAR AND MUCH HONOURED SI R ,P lea se a ccept a t this tim e m y tha nks a ndfriendlygreetings.

Things ha ve not a ltered with us m uch of la te [litera lly, In our

ca se the recently or quickly pa ssed tim e ha s not signified m uch].We still deplore our friend m ost Sincerely. I a m a s gra teful a s I

wa s before for your expressions offeeling. In the course ofthewinter I ha ve seen our sick friend often, never without hisrem em bering you a ffectiona tely. He never la cked sym pa thy

a nd loving ca re, a nd the excellent people with whom he liveda re highly to be com m ended in tha t respect . A few days beforehis dea th, I went to I ta ly, a nd only found your letter when I

returned to Thun.

“ I t wa s a grea t plea sure to m e to rea d your words, a nd to

know them a ddressed to m yself. Will you let m e a ga in tha nk

you for them ? My tha nks com e from the heart, a s they m ustwhen I think ofour friend, the best a nd m ost a ffectiona te fellowon ea rth. With hea rty greetings,

Your devoted,“

J . BRAHMS ”

28 BRAHMS

forte pieces, Opp. 1 16—19, of the Germ an folk-songs, of the

works suggested by the masterly clarinet playing of

P rofessor Muhlfeld, a nd ofthose wonderful Ernste Gesc’

iuge

which close the master’s list of compositions with suchnoble meditations on death a nd what l ies beyond the

grave. These were partly inspired by the death ofF rau

Schumann on 20 Ma y, 1896, which was a terrible shock toBrahms ; mentally, he was grievously afflicted by it, a ndphysically he never completely recovered from a chil lcaught at her funeral. Between this time a nd his owndeath the only work he accomplished was the arrangementofa set ofeleven chorale-preludes for the organ, written atvarious dates, though not published til l after his death.

In September, 1896,he went to Carlsbad for a cure ; hesuffered very greatly during the winter, but managed toattend several concerts, such as those given by the Joachim

Quartet in Vienna in January (when his G major quintetwas played with great success), the Philharmonic Concertof 7 March; when his fourth symphony a nd Dvoi' ak

’

s

Violoncel lo concerto (a piece for which he had unboundedadmiration) were played, a nd he went twice to the opera.He passed away— the cause ofdeath being degenerationofthe liver— in the presence ofhis kind housekeeper, F rauCelestine Truxa, on 3 April, 1897, at the lodging, 4,Ca rlsga sse, where he had lived quietly for a quarter of

a century. He was buried in the Central F riedhof on

6 April, a nd many were the memorial concerts given in hishonour all the world over .

By a strange mischance, a will about which he consultedhis old friends Dr. a nd F rau Fel l inger was not executed,a nd the only valid testament was in the form ofa letter toS imrock, the publisher. There were compl ications of

various kinds, sundry cousins making claims to the

BI OGRAPHI CAL 29

master’s property. U ltimately a compromise was arrivedat, with the result that the blood relations have beenrecognised as hei rs to all but the l ibrary, which is now inthe possession ofthe Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde ; that

F rau Trux a ’s legacy has been paid, a nd that certain sumsaccepted by the societies [the L iszt Pensionverein of

Hamburg, the Czerny Verein, a nd the Gesel lschaft derMusikfreunde], by which they wil l u ltimately benefit, havebeen invested, a nd the income arising from them securedfor the payment of the l ife-annuity to Herr Schna ck ’”l [theson ofF rau Caroline Brahms, who died in

The first monument to the master’s memory was thatexecuted by H i ldebrandt, which was uncovered atMeiningen on 7 October, 1899 . On the seventiethanniversary of the master’s birth, 7 Ma y, 190 3, amonument, designed by F raulein I lse Conra t, was erectedat the grave. F ive years later, on the same anniversary,another monument was inaugurated at Vienna, the workof Rudo lf Weyr ; a nd on the birthday in 190 9 amonument by Ma x Kl inger was unveiled at Hamburg,near the entrance to the new Musikhalle, a nd a com

memorative tablet was placed on the house where Brahmsstayed at Dusseldorf. Houses inwhich he lived at Vienna,I schl, a nd Thun have been decorated in the same way. A

Brahms Museum,planned so as to conform exactly to the

dimensions ofBrahms’s rooms at I schl, a nd to contain thefurniture from those rooms, has been founded at Gm iindenby Dr. V ictor von M iller zu Aichholz, who has col lectedmany autographs a nd personal rel ics ofall kinds.

I t would be diflicult to name a ny famous m a nwho had

so great a n objection as Brahms had to the habit of

wearing his heart upon his sleeve. He carried his

Miss Ma y’s Life, 11. 290 .

30 BRAHMS

characteristic reticence so fa r that his brusquerie of

manner is the feature most familiar to the readers ofthebooks about him. There a re already many hundreds ofstories

,some of them no doubt true, which Show a certain

mischievous disposition, especially towards people whom

he suspected ofa wish to “ lionize ” him ; but his quietacts ofkindness more than counterbalance these superficial

eccentricities, which after all seem more l ike the smalltransgressions ofa vigorous child. There were numberless points inwhich he remained a child throughout his life,as though he trailed his clouds ofglory longer than mostm en. That he should have been devoted to his tin so ldiersas a child is ofcourse nothing at al l remarkable, but it israther significant that he should have careful ly kept themin his possession until he wa s twenty-eight years old, a ndhave shown them to his friend Dietrich, saying that hecould not bear to part with them .

I He shared with manyofthe great m en ofthe world a faculty for going to sleepat a moment’s notice, a nd rising refreshed after only a fewminutes’ slumber. I t is undoubtedly true that he wascareless in the matter ofdress, a nd that he hated anythinglike ceremonial customs or stiff behaviour ; on the platformhis manner ofbowing (in 18 59) was, according to Joachim,

like the action ofa swimmer who comes to the surface a ndshakes the water from his hair.2 Oflicia l recognition ofhiseminence meant less than nothing to him his indifferencewas by no means a pose, but was just the result ofthehatred he fel t towards certain sycophantic recipients ofcourt favour . Much was formerly heard of his bluff ways

,

which no doubt did often cause pain to many sensitivesouls but the publication ofhis correspondence with such

Recollections , by Dietrich a ndWidm ann, tra ns . pp. 37, 38 .

Litzm a nn, Cla r a Scl mm a nn, iii. 48 .

BIOGRAPHICAL 3 1

intimates a s the Herzogenbergs, J. O. Grimm, Joachim ,

a nd, above all,Madame Schumann, shows how del icate washis tact in the real things ofl ife,how ready hewa s to Showhis practical sympathy with other people

,though his

friends may have had to humour his little idiosyncrasiesin the matter ofhis personal habits a nd comforts, a nd howtruly generous was his nature. Once, when leaving hisparents’ home after a visit to them (when his ownmeanshad become comparatively ample for his needs), he put anumber of bank-notes between the pages ofhis Copy of

Handel’s S aul, a nd said to his father when taking leave,Dear father, if things go badly with you, the bestconsolation is always in music. Read carefully in m y

old S a ul a nd you’l l find what you want . H is loving carefor F rau Schumann, for his stepmother a nd her son, a nd

for others who looked to him for help of one kind or

another, is abundantly clear, a nd a larger-minded or moreopen

-handed m a n surely never lived . He appreciated thepleasures of life a nd was not afraid to let his enjoyment be

seen ; yet he was no voluptuary, careless ofthe ultimatedestiny of the race or of the individual. Even if we hadnothing to go by but the words of his choral works, weshould know that the problems of human destiny, of life,death

, a nd immortality, engrossed him throughout his life.

The Sclzicksa lsliea'

, Rhapsoa’ie, Requiem ,

the two motets,Op. 74, a nd the apart-songs, Op. 104, tel l us, evenwithoutthe evidence of the Serious Songs, which were the lastpublication of his life, that he was a nearnest thinker, a ndthat he had faced the great questions bravely a nd hadfound a n answer to them which for him was sufficient.

While Shr inking from the dogmas of the Churches, a ndveryShy of owning the beliefs he held, be yet shows his deepconviction of the immorta l ity ofthe soul a nd a sure a nd

32 BRAHMS

certain hope ofits future happiness. In letters to F rau vonHerzogenberg,

I he asks her to find “ heathenish ” wordsfrom Scripture for him to set, meaning thereby such textsas appear in the first three ofthe Serious Songs . Though

the landmarks of rel igions might be removed, thoughdoctrines that guided the l ives ofhis ancestors might beassailed a nd discredited, though the higher criticism mightseem to demol ish the credibility ofthe Scripture records,

yet a great a nd merciful system is dimly apprehended, a ndupon this he rel ies for comfort a nd guidance. The

publication ofthe commonplace-book in which he wrotefavourite extracts from the l iterature ofdifferent countries 2

has throwna fresh l ight on his own inner life, a nd i llustrateshis big

,healthy nature (see p.

This may be a convenient place to attempt a summaryof the Brahms literature, including the L ives a nd the

published correspondence, the issue ofwhich makes thebiographer’s task especial ly easy in the present day.

The first authoritative life of the master,by Dr.

HermannDeiters, appeared in the S a m m lung m usz'

ka lzkclzer

Vortrage in 1880 ; it was translated into English by RosaNewm a rch, a nd published,with additions, in 1888 ; reissuedafter the master’s death, in 1898.

J . B. Vogel’s jolta nnes Bra hm s, sein Lebensga ng

'

,

appeared in 188 8 .

Heinrich Reim a nn’

s joha nnes Branm s was published,without date, by the Berlin H a rm onie

,as one ofa useful

series of il lustrated monographs on great composers. I t

appeared soonafter the composer's death

,with a S l ip inserted

at the beginning giving the date ofthat death as 1896 !

Correspondence, i. 20 0 ; trans ., 274 .

2 Des jungen Kreislers Sclza tzka'

stlein, her a usgegeben von [ofiannesBr a hm s, wa s published by the Bra hm s-Gesellscha ft in 190 8 .

BI OGRAPHI CAL 33

Ma x Ka lbeck’

s exhaustive biography of the master, themost thoroughgoing work ofits kind, is not yet completed ,a nd it is doubtful whether the difliculties which arose afterthe second instalment was published will ever be sur

mounted. The first volume appeared in 190 4, carryingthe narrative ofhis life only as far as 1862 ; the second,completed in 190 9 (intwo half-volumes), goes down to 1 874.

A remarkably good a nd complete biography was writtenby Miss F lorence Ma y, a nd published in two volumes in190 5. The author had previously contributed some“ Personal Recol lections of Brahms to a short-l ivedperiodical, The Musica l Ga zette (published by JosephWil l iams inH. C. Colles

’

s Branm s (John Lane, 190 8) contains awonderful amount of valuable information in a smallspace.

Erinnerungen a njo/za nnes Bra km s,by Albert Dietrich

a nd J . V. Widmann were issued in a n Englishtranslation by Dora Hecht in 1899, a nd published bySeeley Co.

The letters ofthe eminent surgeon Dr. Theodor Billroth,one of the most intimate friends ofBrahms, himself a nenthusiastic musician a nd writer on the art

,contain many

interesting details ofthe master.Joachim’s oration at the unveil ing of the Meiningen

monument in 1 899 was published as Zum Gea’

c'

z'

clztnzlrs a’es

M eislersjo/za nnes Bra /zm s .

The Neues Wiener Tagebla tt for 9 Ma y, 190 1, containsH. von Meysenbug

’

s Ans jona nnes Bra km s’

jugendtagen,a nd the same periodical on 3 a nd 4 April in the followingyear printed K. von Meysenbug

’

s contribution with the

same title.

The 74m m of the Gesel lschaft HamburgischerD

34 BRAHMS

Kunstfreunde for 190 2 contains a n interesting series of

B ra /zm s -Erinnerungen a us dem Tageéucic von F ra u

Wa sseroa udirector Lenta , geb. M eier .

The account oftheVienna monument,Zur Entnullunga’

es Bra /zm s-Den/em a l in Wien, 7 M a i,190 8, contains some

interesting articles . A picture of the monument itself is

inserted facing page 34 .

A special Brahms number ofthe periodical called DieMusik, issued M a y, 190 3, contains var ious articles a nd

i l lustrations. The Brahms-Gesel lschaft, founded afterthe master’s death, has done excel lent work in publishing his correspondence, as wel l as in other ways. Six

vo lumes have already appeared , containing the master’s

own letters a nd those of his correspondents. Vols. I .a nd I I . contain the correspondence with Herr a nd F rauvonHerzogenberg, edited by Ma x Ka lbeck, 190 8 . They havebeen translated by Hannah Bryant, a nd published byJohn Murray, London, in 190 9. The husband a nd wifewere in some ways the most intimate friends ofBrahms,with the exception of Joachim a nd Madame Schumann.

Both the Herzogenbergs were accomplished musicians, thehusband a com poser of some distinction, the wife skilledin interpretation, a nd possessed of a remarkable insighta nd critica l faculty. Both allowed themselves to criticizeeach new work ofBrahms with perfect freedom, a nd it isinteresting to see how often he took their hints a nd actedupon them . These volumes a re especial ly interesting tostudents ofthe details inBrahms’s workmanship, thoughvery Often the reader is struck by his disregard ofsomeimportant question put to him by F rau vonHerzogenberg,

or by his habit ofdismissing what she says with a curtword or two that falls oddly on English ears accustomedto the conventional courtesies ofdaily l ife. The impres

BI OGRAPHI CAL 35

sion made by these two volumes is that the bulk ofthe

actual mater ial of the letters comes from the Herzogenbergs rather than from Brahms but in the third volume ofthe series (edited byWilhelm Alt-mann) Brahms is the chiefwriter. The letters deal with the composition a nd the firstperformance ofthe R equiem , a nd a re ofthe highest valueto students ofthat work. Reintha ler organized the quasicomplete performance ofthe R equiem inBremenCathedralon 10 April, 1868 ; a nd the correspondence about thatwork, as wel l as about later compositions of the master,is most interesting. The letters range from 1867 untilReintha ler

’

s death in 1896. The next division ofthe bookcontains six letters ofBrahms to Ma x Bruch

,with nine

from Bruch to Brahms, which deal principally with Bruch’s

works rather than with those ofBrahms, although therea re passages concerning the R equiem to be found in

them . To Hermann Deiters Brahms wrote a good manydetails concerning his works, notably the Haydn variations a nd the two overtures these a re printed next with asingle letter to P rofessor Heim soeth, ofBonn, about the

Schumann festival of1873. A few short communicationsfrom Brahms to Reinecke, ofno great importance, lead to

the correspondence with P rofessor Rudorff, a section

of great interest, spread over the years 1865 to 18 86.

There a re two facsimiles of the corrections undertaken by Brahms a nd R udorff respectively of acorrupt passage in the score of a flute concerto of

Mozart ; a nd some details concerned with the edition

ofChopin’s complete works a re given. The last section

of the volume contains letters to a nd from Bernhard

Scholz a nd his wife, who were among the closer friendsof the composer ; it will be remembered that Scholz was

one of the four signatories ofthe famous protest. The

36 BRAHMS

correspondence dates from 1874 to 18 8 2 , or rather thosedates cover all the letters that have been preserved . JuliusOtto Grimm, the remaining signatory of the protest,whose correspondence with Brahms occupies the fourthvolume of the series, edited by R ichard Barth, was themaster’s friend from 1853, a nd outlived him by six years,although he was six years o lder. The volume gives us arepresentative picture ofall the different sides ofBrahms’snature, for there a re plenty ofboyish jokes enshrined in it,as wel l as discussions on music, a nd many references to thelady, Agathe vonS iebold, upon whom Brahms’s affectionswere fixed at the time of his tenure of the post at thecourt of L ippe—Detmold, a nd who l ived at GOttingen,where Grimm was director ofthe Musical Academy. The

fifth a nd sixth vo lumes ofthe letters, edited by AndreasMoser, take us into the inmost shrine ofBrahms’s life, forthey contain the correspondence with Joachim , a nd showus the faithful picture ofthe wonderful friendship which

produced such rich fruit in the history ofmusic. Withthese, a nd the letters

[

to a nd from Madame Schumann,published in the third volume of her L ife by L itzmann

the reader is admitted into the close intimacy of

the master.The Brahms-Gesellschaft also printed the extract-book

or commonplace-book in which Brahms put down passagesthat struck him in the l iterature ofmany countries. He

cal led itDesjungenKreislers Sc/ia tzka'

stlein— a nd this titleis kept by the editor, Carl Krebs, who issued it in 190 8 in

a cover in imitation ofthe original paper-bound book. I t

contains over six hundred aphorisms a nd quotations fromall manner ofsources, as well as a number ofweightysentences by Joachim, marked F . A. E.

”

(see pp. 32 ,The English reader may be directed to some important

BIOGRAPHICAL 37

contributions to the Brahms literature, such as the fol lowing

S tudies in Modern Music, by W. H. Hadow, secondseries, 1895.

S tudies in Music, reprinted from Tlte Musicia n, 190 1 ,contains a n article on Brahms by the late Philipp Spitta.James Huneker’s Mezzotints inM odernMusic contains

a n article on Brahms, called The Music ofthe Future.

”

Daniel Gregory Mason’s F rom Grieg to Bra hm s, New

York, 190 5, has a thoughtful article.

J . L . Erb’s B r a hm s is a summary published in Dent’sM a ster Musicia ns , 190 5.

The Contempora ry R eview for 1897 contains a n articleon Brahms a nd the C lassical Position.

”

Georg Henschel read a paper on“Personal R ecollec

tions ” of the composer before the Royal Institution in190 5.

In F rench some very interesting books were written bythe la te Hugues Imbert, who did a great work inobtaininga hearing for Brahms in F rance . His chief book on the

subject isjolta nnes'

Bra itm sJ a vie et son ceuvre, Paris, 190 6.

The later editions of the dictionaries ofGrove a nd

R iemann contain extensive articles.

CHAP TER I I

BRAHMS AND H I S CONTEMPORAR I ES

S a supplement to the necessari ly meagre summary ofthe outward events in the l ife ofBrahms, it may not

be uninteresting to touch upon his own preferences inmusic, to trace the course by which his works becameknown throughout the World, to consider the influence of

his contemporaries upon him,a nd to gather as far as may

be possible the opinions formed about him by musiciansofdifferent generations. The first 15 of course, far lessimportant than the rest, for composers a re most rarelydowered with the critical faculty, a nd the only value weca n set upon the Opinions even ofa Brahms is for the sakeofthe light they throw upon his own nature. The fact,for example, that Ca rm en was one of the composer

’sfavourite operas does not affect our estimate ofthat workone way or another. I t is unlikely that a ny ofthe Brahmsenthusiasts think more highly ofit because he admired it,a nd we may do his professed detractors the justice to

suppose that none ofthem has gone SO far as to slightBizet’s masterpiece because Brahms praised it. But it isofno l ittle interest to the student ofhis character to knowthat he could heartily admire the frank, straightforwardmelodies a nd the characterization ofa work so very farremoved in style from what a re generally supposed to be

38

BRAHMS AND H I S CONTEMPORARIES 39

the distinguishing marks of his own music. I t is of fargreater importance to make clear the attitude of Brahmstowards the work ofWagner, a n attitude concerning whichso many misstatements have been industriously circulated,that too much stress ca n hardly be laid upon the actualfacts of the case. In German musical circles there has

for many years been a habit of making sharp divisionsbetweenthe admirers ofa ny two great contemporaries. Theharm it did in the case ofMendelssohn a nd Schumann iswel l known to every student ofmusical history a ndwhilethe musical world ofGermany continues to find a greatpart ofits artistic enjoyment in the diversion of splittingitself into opposing camps, no observer ca n wonder that

Brahms Should have been set up, entirely against his will,as the chief bulwark against the music ofthe new school.About the year 1860 the materials for a new arrangement ofparties were just preparing, a nd the main difficulty in the

way of a comfortable split was the personality a nd the artof Schumann himself. He had founded the Neue Zeit

sc/trift, a nd in many ways had shown himself in the

advanced ranks ofhis time, so that the “new partycould by no means dispense with his name on the otherhand, he had declared himsel f, with what might be almostcalled his last words to the world, a champion of the musicof Brahms, who, a few years before, had definitely severedhimself from the “

new”

party. These latter, havingcelebrated the 2sth anniversary of the foundation of

Schumann’s periodical by a festival of four days in1859, arranged a festiva l in Schumann

’s special honour,

at his birthplace, Zwickau, in June, 1860 . A generalinvitation was issued to all music-lovers to attend the

festival ; but beyond this, neither Madame Schumann,Joachim, nor Brahms received a ny further communication

4o BRAHMS

with regard to the celebration. I t may not have beenintentionally done in order to slight those who stoodnearest to Schumann in life, but the net result to the

new” party was that the marked absence of these

intimates on such a n occasion could be convenientlyturned to the uses of the combatants, a s it was of

course implied that they had stayed away out of jealousy.F rom this time forth, the new

” school was nevertired of trying to make out that Schumann’s friendswanted to keep his music a nd his fame as a kind ofprivate property of the ir own, a nd even that the truetraditions of Schumann’s music were not to be foundamong those who knew him best. This assumption ofthe L iszt party may even now be occasionally observedin criticism, but ofcourse there was not the slightestfoundation for supposing that the

“ classical party everthought ofmaking themselves into a kind ofsect. Theywere ultimately forced into completely breaking with the“new

” party, but it was the new party with which lay

the responsibility for the cleavage. With regard to L iszt’smost representative works, the symphonic poems, Brahmsshared with Wagner a nd Joachim the unfavourableopinions which Wagner could not very wel l express,as the others were perfectly free to do ; but for the

art ofWagner himself Brahms had nothing but admiration. In the correspondence with Joachim at the time of

the unfortunate protest against the Weimar fabrications,Brahms is careful to make it clear that he does not includeWagner among the m en whose influence he wishes tocounteract.t What has been cal led the Wa hnfried

”

atmosphere, with its hothouse exhalations,could never

have been congenial to Brahms, a nd the personalities of

Seejoa clzim Correspondence, i. 274 .

42 BRAHMS

breath ofadverse criticism . But, apart from constitu

tiona l diversity, Brahms understood a nd sympathized with

Wagner’s music at a time when the Wagner cause wassti ll to be won.

The exact opposite of this is true in regard to the

relations ofBrahms with Tchaikovsky. The account oftheir meeting at Hamburg in 18 89 shows that

“the per

sona lity ofBrahms, his purity a nd loftiness ofaim, a nd

earnestness of purpose, won Tchaikovsky’s sympathy.

Wagner’s personality a nd views were, on the contrary,

antipathetic to him but his music awoke his enthusiasm,

while the works ofBrahms left him unmoved to the end

ofhis l ife.

” 1 I t is wel l known that the art ofeach ofthetwo had little which could appeal to the other. I t maybe suggested that there was a reason for this quite apartfrom the polemics which have so much to do with musicon the Continent. Brahms

,as we shall see, had a Special

l iking for themes built on the successive notes ofa chordit is one of Tchaikovsky’s most obvious characteristicsthat in his most beautiful a nd individual subjects, themovement is what is called conjunct that is

,the suc

cessive notes a re those ofa scale, not ofa chord. Almost

every theme in the “ P athetic ” symphony, to take the

best-known instance, is formed in this way, a nd a carefulstudy of the Russian’s themes from this point of viewofstructure will Show a surprising preponderance ofthosewhich a re built on successive notes of the scale. The

difference is perhaps not one that would be obvious at

once, least ofal l to the composers themselves, for it isprobable that neither was conscious ofhis own predilections in the formation ofthemes but for this very reason

complete sympathy would be the less easy to establish

Gra ve’s Dictiona ry (2nd v. 39.

BRAHMS AND HI S CONTEMPORARI ES 43

between them. Remembering, too, that one was preeminently a colourist, the other pro-eminently a draughts

m a n, the wonder would have been if they had appreciated

one another’s music. The same cause might, it is true,be supposed to interfere with Brahms’s admirationofWagner, since

“ Wagner was the greatest pioneer oforchestral colouring in modern music ; but the works ofthe great music -dramatist stand so obviously apart from

the rest ofmusic, a nd in particular from the classicalmodels, that they could be thoroughly enjoyed as completeart-products in their own way, even by a champion of the

classical tradition.

The figure ofR ubinstein loomed large on the world inhis lifetime, a nd it is ofsome interest to see what he a nd

Brahms thought of each other. Ka lbeck I gives a n

extract from a letter of Rubinstein’s to L iszt, in whichthe virtuoso’s fi rst impressions a re amusingly summed“P

Pour cc qui est de Brahms, je ne saurais pas trop

préciser l’

im pression qu’il m ’a faite ; pour le salon il

n’

est pa s assez gracieux, pour la salle de concert, il nestpas assez fougueux, pour les champs, il n

’

est pa s assezprimitif

,pour la vi lle, pas assez général— j

’ai peu de foi ences natures Another less agreeable reference to

Brahms is reported at secondhand in B‘

ulow’s letters,a nd we may hope that Rubinstein never m ade i t : “ Si

j’

a va is voulu courtiser la presse, on n’

entendra it pas parlerni de Wagner ni de Brahms.” I t is hardly necessary to

po int out that of all m enwho ever lived, Brahms was theleast likely to courtiser la presse, while Rubinstein los tno opportunity ofadding to the very temporary edifice of

his renown as a composer. U nfortunately, we have no

i. 268 .

44 BRAHMS

record ofwhat Brahms’s opinion wa s of Rubinstein’smusic, beyond a passing reference to his ways of composing

, a nd in pa rticular, to a sight Brahms once had of aset of perfectly blank music-pages provided with a fulltitle a nd opus-number, before a note of the songs hadbeenwritten.

I Rubinstein’s appreciation of the music ofBrahms seems to have been l imited to a performance of amovement from the D major serenade at one of theconcerts ofthe Music Society ofSt . Petersburg in 1864.

At his later historical pianoforte recitals not a note ofBrahms was played, although he conducted choral worksof his on various occasions .Al though there is no record ofBrahms being present

at the performance of Verdi’s operas in his I talianjourneys, his admiration for the I talian m aster’s R equiemwas hearty, immediate, a nd sincere. One ofHans vonBiilow

’

s not infrequent al terations ofopinion was in regardto this composition, against which he spoke at first withcharacteristic lack of moderation. Some time afterBrahms had expressed his del ight in it

, Biilow changedhis mind, as he did with fine generosity in respect to themusic of Brahms himself. German writers have spentmuch time in debating why Brahms wrote no opera, a ndone of them, Alfred Kuhn by name, went so far as toinvent a n interview with the composer on the subject.The upshot of the story, quoted from the S tr a ssburger

P ost of 13 April, 1897, may be read in J . K.Widm a nn’

s

R ecollections,2 a nd it is clear that the master was in no

way disinclined to write a n opera if a good libretto wasforthcoming. He discussed many subjects withWidmann,but, as a ll the world knows, the cantata R ina ldo remainsthe only example ofhow he might have treated opera had

Ka lbeck, I I . 179, note 2 .2 English tra ns., 10 7.

BRAHMS AND HI S CONTEMPORARIES 45

he found a good book. Looking at his completed workas a who le, it is easy to see that his subtle way ofdealingwith deep emotions, which comes out in so many ofthesongs, must have been lost on the stage or abandoned for amore superficial style which would not have been truly con

genial or characteristic . I t is curious to learn from the

same source I that Brahms considered the ideal conditionsofopera to consist in a combination of spoken dialogue or

recita tivo secco, with set-pieces for the lyrical climaxes. I t

would have been dlffiCU lt even for Brahms to obtain the

approval of the world at large for a method of operat icwriting which must be considered a little reactionary inthe present day a nd while the method of continuousmusic had the weighty support ofWagner a nd all thetypica l ly modern composers ofall nations, it would havebeen a miracle if a n opera composed on the other system,

even by a great master, had really succeeded. On the

who le we need not regret that Brahms left the Operaticstage to others . The kindly interest he took in the careerofHermann Goetz was no doubt largely due to com

passion for his sta te ofhealth ; be greatly admired The

Ta m ing of the Shrew, but regretted the posthumous production ofF ra ncesca da R im ini, though he had aided withhis counsel those who undertook to complete the work ;but the two m en were so widely different in character a nd

disposition that they never could have become intimate,even if Brahms had not unintentionally wounded Goetz’ssupersensitive nature by asking him, Do you also amuseyourself with such things ?” when he saw some newlywritten sheets ofmusic on his desk . Of course Goetz waswrong to be annoyed, a nd his solemn reply,

“ That is thehol iest thing I possess ! ” naturally piqued Brahms, who