louis i kahn

-

Upload

gungun-tcd -

Category

Documents

-

view

521 -

download

4

Transcript of louis i kahn

The evolution of plans for the current building took almost 15 years, from the first ideas for a "new library" to its final

form. At least three different projects were undertaken to plan for the library, with the results of the first two bearing

no resemblance to what we now know as the Class of 1945 Library. However rocky its inception, the building is now

viewed as an architectural gem. In 1997, the Library was awarded the American Institute of Architects’ Twenty-five

Year Award. The citation of the award states:

"An outstanding collaboration of design and technology, this icon of cleanly articulated structure is a cultural center and modern architectural masterpiece for the original quadrangle of the renowned Academy. The massive block of dark-red brick reveals a surprising delicacy. It is artistically ahead of its time and will continue to enlighten as a spiritual touchstone of great design for generations of architects."

Initially, the Academy simply planned to put an addition on the original Davis Library, which had been designed by

Ralph Adams Cram. When these plans were rejected by the school’s trustees as inadequate solutions to the

school’s library requirements, a new effort focused on designing a separate building. The trustees' charge to this

effort was "to anticipate the Academy's needs for the next 25 years and to design an exterior that would 'blend in

with our beautiful Georgian buildings.'"1

J a m e s T u c k e r Rodney Armstrong, then Academy Librarian, worked with

a faculty committee and an architect appointed by the trustees over the next

several years. In 1964, however, newly-appointed principal Richard W. Day,

reviewing the results of this effort, which was at the stage of developing final

working drawings, was dismayed at what he saw. He fired the architect and

started over.

Day appointed Rodney Armstrong to chair a small faculty committee, whose

members Armstrong could choose, to develop a program statement for the

library, develop plans for a separate building, and recommend an architect

to the trustees. In Armstrong's words, Principal Day's charge to the committee was "to rewrite the program and to

propose 'the outstanding contemporary architect in the world' to design Exeter's new library. We were to receive and

consider suggestions from trustees, colleagues, alumni and friends, and to travel anywhere, here and abroad, as we

thought best, to look at buildings." 2

Meeting in 1964 and 1965, the committee conferred with numerous architects before recommending Louis I. Kahn,

FAIA, as the architect, whom they admired "for his sympathetic use of brick and his concern for natural light."3 Their

recommendation was accepted in November 1965.

The final design document, entitled "Proposals for the Library at Phillips Exeter Academy," also had the subtitle of

"Program of Requirements for the New Library Recommended by the Library Committee of the Faculty." Published

in its final version in June 1966, the document is unusual in its approach, breadth, and conclusions.

Working both with Kahn and with Engelhardt, Engelhardt and Leggett, educational consultants from Purdy Station,

New York, the committee covered every aspect of the building, from philosophy to practical details, with great

emphasis on the atmosphere desired both within and without the building. In addition to outlining functional

requirements for the library, the committee specified site and exterior design, design details, staff facilities, spatial

relationships, and items such as air conditioning, lighting, electrical and mechanical equipment, and security, fire,

and water protection. Some excerpts best capture the flavor of the document:

© S t e v e R o s e n t h a l "The quality of a library, by inspiring a superior faculty

and attracting superior students, determines the effectiveness of a school. No

longer a mere depository of books and magazines, the modern library becomes

a laboratory for research and experimentation, a quiet retreat for study, reading

and reflection, the intellectual center of the community.… Fulfilling needs of a

school expected eventually to number one thousand students, unpretentious,

though in a handsome, inviting contemporary style, such a library would affirm

the regard at the Academy for the work of the mind and the hands of man."4

One of the most striking notes in the document is that "the emphasis should not be on housing books but on

housing readers using books. It is therefore desirable to seek an environment that would encourage and insure the

pleasure of reading and study."5 Following this logic, the committee goes on to recommend a variety of choices of

seating areas for students and faculty, including both hard and soft chairs, near windows and in interior areas of the

building. A requirement for either a garden or a shaded terrace at another level is also specified.

At the end of the document, discussing spatial relationships, the committee stresses "that a reader as he enters be

able to sense at once the building’s plan."6 Kahn admirably accomplished this charge. Entering from the main

entrances on the ground floor, and climbing the stairs to the first floor, the visitor can immediately perceive the

relationship of reference area, circulation desk, and book stacks.

Supervision of student behavior and security of the collections were not given much prominence in the design

document, as the Academy’s experience with both had been good. This led to a specification that the circulation

desk be located on the first floor, rather than on the ground floor directly inside the main entrance, as is traditional in

most libraries. Placing the circulation desk closer to the center of library activities ensured that service took priority

over supervision.

Embracing the committee’s specification on the use of traditional Exeter brick, stone, and slate, Kahn also

incorporated extensive use of natural wood (primarily teak and white oak), travertine, and concrete, producing a

building that is warm, impressive and highly functional.

________________________________________

1 Rodney Armstrong, "Lou Who?," The Phillips Exeter Bulletin Spring 2004: 26.

2 Armstrong, 26.

3 Rodney Armstrong, "The New Library," The Phillips Exeter Bulletin Summer 1967: 8.

4 Rodney Armstrong, Elliot G. Fish, and Albert C. Ganley, Proposals for The Library at The Phillips Exeter Academy (Exeter, NH: Phillips Exeter Academy, 1966), 1.

5 Armstrong et al., 6.

6 Armstrong et al., 22.

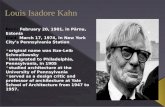

Louis Isadore Kahn (born Itze-Leib Schmuilowsky) (February 20, 1901 or 1902 – March 17, 1974) was a world-renowned American architect of Estonian Jewish origin,[1] based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. After working in various capacities for several firms in Philadelphia, he founded his own atelier in 1935. While continuing his private practice, he served as a design critic and professor of architecture at Yale School of Architecture from 1947 to 1957. From 1957 until his death, he was a professor of architecture at the School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania. Influenced by ancient ruins, Kahn's style tends to the monumental and monolithic; his heavy buildings do not hide their weight, their materials, or the way they are assembled.

He trained in a rigorous Beaux-Arts tradition, with its emphasis on drawing, at the University of

Pennsylvania. After completing his Bachelor of Architecture in 1924, Kahn worked as senior

draftsman in the office of City Architect John Molitor. In this capacity, he worked on the design for

the 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition.[5]

In 1928, Kahn made a European tour and took a particular interest in the medieval walled city

of Carcassonne, France and the castles of Scotland rather than any of the strongholds

of classicism or modernism.[6] After returning to the States in 1929, Kahn worked in the offices of Paul

Philippe Cret, his former studio critic at the University of Pennsylvania, and in the offices

of Zantzinger , Borie and Medary in Philadelphia.[5] In 1932, Kahn and Dominique Berninger founded

the Architectural Research Group, whose members were interested in the populist social agenda and

new aesthetics of the European avant-gardes. Among the projects Kahn worked on during this

collaboration are unbuilt schemes for public housing that had originally been presented to the Public

Works Administration.[5]

Among the more important of Kahn's early collaborations was with George Howe.[7] Kahn worked with

Howe in late 1930s on projects for the Philadelphia Housing Authority and again in 1940, along with

German-born architect Oscar Stonorov for the design of housing developments in other parts

of Pennsylvania.[8]

The National Assembly Building (Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban ) ofBangladesh

Kahn did not find his distinctive architectural style until he was in his fifties. Initially working in a fairly

orthodox version of the International Style, a stay at the American Academy in Rome in the early

1950s marked a turning point in Kahn's career. The back-to-the-basics approach he adopted after

visiting the ruins of ancient buildings in Italy, Greece, and Egypt helped him to develop his own style

of architecture influenced by earlier modern movements but not limited by their sometimes dogmatic

ideologies.

In 1961 he received a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts to

study traffic movement [9] [10] in Philadelphia and create a proposal for a viaduct system. He describes

this proposal at a lecture given in 1962 at the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado:

In the center of town the streets should become buildings. This should be interplayed with a sense of

movement which does not tax local streets for non-local traffic. There should be a system of viaducts

which encase an area which can reclaim the local streets for their own use, and it should be made so

this viaduct has a ground floor of shops and usable area. A model which I did for the Graham

Foundation recently, and which I presented to Mr. Entenza, showed the scheme.[11]

Kahn's teaching career began at Yale University in 1947, and he was eventually named Albert F.

Bemis Professor of Architecture and Planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1962

and Paul Philippe Cret Professor of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania in 1966 and was

also a Visiting Lecturer at Princeton University from 1961 to 1967. Kahn was elected a Fellow in

the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1953. He was made a member of the National Institute of

Arts and Letters in 1964. He was awarded the Frank P. Brown Medalin 1964. He was made a

member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1968 and awarded the AIA Gold Medal,

the highest award given by the AIA, in 1971[12] and the Royal Gold Medal by the RIBA in 1972

Yale University Art Gallery , New Haven, Connecticut,(1951–1953), the first significant commission

of Louis Kahn and his first masterpiece, replete with technical innovations. For example, he

designed a hollow concrete tetrahedral space-frame that did away with the need for ductwork and

reduced the floor-to-floor height by channeling air through the structure itself. Like many of Kahn's

buildings, the Art Gallery makes subtle references to its context while overtly rejecting any

historical style.

Richards Medical Research Laboratories , University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

(1957–1965), a breakthrough in Kahn's career that helped set new directions for modern

architecture with its clear expression of served and servant spaces and its evocation of the

architecture of the past.

The Salk Institute, La Jolla, California, (1959–1965), was to be a campus composed of three main

clusters: meeting and conference areas, living quarters, and laboratories. Only the laboratory

cluster, consisting of two parallel blocks enclosing a water garden, was actually built. The two

laboratory blocks frame an exquisite view of the Pacific Ocean, accentuated by a thin linear

fountain that seems to reach for the horizon.

First Unitarian Church , Rochester, New York (1959–1969), named as one of the greatest religious

structures of the 20th century by Paul Goldberger, Pulitzer Prize-winning architectural critic.

[14] Tall, narrow window recesses create an irregular rhythm of shadows on the exterior while four

light towers flood the sanctuary walls with indirect natural light.

Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad , in Ahmedabad , India (1962).

Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban (National Assembly Building) in Dhaka, Bangladesh (1962–1974),

considered to be his masterpiece and one of the great monuments of International Modernism.

Phillips Exeter Academy Library , Exeter, New Hampshire, (1965–1972), awarded the Twenty-five

Year Award by the American Institute of Architects in 1997. It is famous for its dramatic atrium

with enormous circular openings into the book stacks.

Kimbell Art Museum , Fort Worth, Texas, (1967–1972), features repeated bays of cycloid-shaped

barrel vaults with light slits along the apex, which bathe the artwork on display in an ever-

changing diffuse light.

Yale Center for British Art , Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, (1969–1974).

Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park , Roosevelt Island, New York, (1972–1974), unbuilt.

Louis Kahn's work infused the International style with a fastidious, highly personal taste, a poetry of

light. His few projects reflect his deep personal involvement with each. Isamu Noguchi called him "a

philosopher among architects." He was known for his ability to create monumental architecture that

responded to the human scale. He was also concerned with creating strong formal distinctions

between served spaces and servantspaces. What he meant by servant spaces was not spaces for

servants, but rather spaces that serve other spaces, such as stairwells, corridors, restrooms, or any

other back-of-house function like storage space or mechanical rooms. His palette of materials tended

toward heavily textured brick and bare concrete, the textures often reinforced by juxtaposition to

highly refined surfaces such as travertine marble.

While widely known for his spaces' poetic sensibilities, Kahn also worked closely with engineers and

contractors on his buildings. The results were often technically innovative and highly refined. In

addition to the influence Kahn's more well-known work has on contemporary architects (such

as Mazharul Islam, Tadao Ando), some of his work (especially the unbuilt City Tower Project) became

very influential among the high-tech architects of the late 20th century (such as Renzo Piano, who

worked in Kahn's office, Richard Rogers and Norman Foster). His prominent apprentices

include Mazharul Islam, Moshe Safdie, Robert Venturi, Jack Diamond.

Many years after his death, Kahn continues to inspire controversy. Interest is growing in a plan to

build a Kahn-designed Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park at the southern tip of Roosevelt

Island.[18] A New York Times editorial opined:

There's a magic to the project. That the task is daunting makes it worthy of the man it honors, who

guided the nation through the Depression, the New Deal and a world war. As for Mr. Kahn, he died in

1974, as he passed alone through New York's Penn Station. In his briefcase were renderings of the

memorial, his last completed plan.[19]

The editorial describes Kahn's plan as:

...simple and elegant. Drawing inspiration from Roosevelt's defense of the Four Freedoms – of

speech and religion, and from want and fear – he designed an open 'room and a garden' at the

bottom of the island. Trees on either side form a 'V' defining a green space, and leading to a two-

walled stone room at the water's edge that frames the United Nations and the rest of the skyline.

Critics note that the panoramic view of Manhattan and the UN are actually blocked by the walls of that

room and by the trees.[20] Other as-yet-unanswered critics have argued more broadly that not enough

thought has been given to what visitors to the memorial would actually be able to do at the site.[21] The

proposed project is opposed by a majority of island residents who were surveyed by theTrust for

Public Land, a national land conservation group currently working extensively on the island.[22]

The movement for the memorial, which was conceived by Kahn's firm almost 35 years ago, needed to

raise $40 million by the end of 2007; as of July 20, it had collected $5.1 million.[23] There is a merest

hint in Architectural Record about the often-heard argument that it must be built because it was

literally Kahn's last project;[24] and this is rebutted by those who've said the plans aren't enough like

Kahn's other work for it to be touted as a memorial to Kahn as well as FDR.[25]

Louis Isadore Kahn (1901-1974), U.S. architect, educator, and philosopher, is one of the foremost twentieth-century architects. Louis I. Kahn evolved an original theoretical and formal language that revitalized modern architecture. His best known works, located in the United States, India, and Bangladesh, were produced in the last two decades of his life. They reveal an integration of structure, a reverence for materials and light, a devotion to archetypal geometry, and a profound concern for humanistic values.

Born in 1901 on the Baltic island of Osel, Louis Isadore Kahn's family emigrated to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1905, where Louis Isadore Kahn lived the rest of his life. Trained in the manner of the Ecole des Beaux Arts under Paul Philippe Cret, Louis Isadore Kahn graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Fine Arts in 1924. Among his first professional experiences was the 1926 Philadelphia Sesquicentennial Exhibition. In the following years Louis Isadore Kahn worked in the offices of Philadelphia's leading architects, Paul Cret (1929-1930) and Zantzinger, Borie and Medary (1930-1932). During the lean years of the 1930s, Louis Isadore Kahn was devoted to the study of modern architecture and housing in particular. Louis I. Kahn undertook housing studies for the Architectural Research Group (1932-1933), a short-lived organization Louis Isadore Kahn helped to establish, and for the Philadelphia City Planning Commission.

i n the later 1930s Louis I. Kahn served as a consultant to the Philadelphia Housing Authority and the United States Housing Authority. His familiarity with modern architecture was broadened when Kahn worked with European emigres Alfred Kastner and Oskar Stonorov. In the early 1940s Louis Isadore Kahn associated with Stonorov and George Howe, with whom Louis Isadore Kahn designed several wartime housing projects such as Carver Court in Coatesville, Pennsylvania (1941-1944) and Pennypack Woods in Philadelphia (1941-1943). His interest in public housing culminated in Philadelphia's Mill Creek Housing project (1951-1963). From these experiences, Louis Isadore Kahn developed a deep sense of social responsibility reflected in his later philosophy of the "institutions" of man.

The year 1947 was a turning point in Louis Isadore Kahn 's career. Kahn established an independent practice and began a distinguished teaching career, first at Yale University as Chief Critic in Architectural Design and Professor of Architecture (1947-1957) and then at the University of Pennsylvania as Cret Professor of Arch

itecture (1957-1974). During those years, his ideas about architecture and the city took shape. Eschewing the international style modernism that characterized his earlier work, Kahn sought to redefine the bases of architecture through a reexaminntion of structure, form, space, and light. Louis Isadore Kahn described his quest for meaningful form as a search for "beginnings," a spiritual resource from which modern man could draw inspiration. The powerful and evocative forms of ancient brick and stone ruins in Italy, Greece, and Egypt where Louis I. Kahn traveled in 1950-1951 while serving as Resident Architect at the American Academy in Rome were an inspiration in his search for what is timeless and essential. The effects of this European odyssey, the honest display of structure, a desire to create a sense of place, and a vocabulary of abstract forms rooted in Platonic geometry resonate in his later masterpieces of brick and concrete, his preferred materials. Louis Isadore Kahn reintroduced geometric, axial plans, centralized spaces, and a sense of solid mural strength, reflective of his beaux-arts training and eschewed by modern architects.

Louis Isadore Kahn 's first mature work, the addition to the Yale University Art Gallery (New Haven. Connecticut. 1951-1953). indicates his interest in experimental structural systems. The floor slabs of poured-in-place concrete were inspired by tetrahedral space frames. The raw texture of the concrete reveals his belief that the method of construction should not be concealed. The hollow, pyramidal spaces in the ceiling, which accommodate lighting and mechanical systems, anticipate his later idea of "served and servant spaces" the hierarchical definition of a buildings functions. The expression of served and servant spaces is clearly enunciated in two later works, the Richards Medical Research Building at the University of Pennsylvania (1957-1965) and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies (LaJolla, California, 1959-1965). In the design of the Richards Building. Louis Isadore Kahn gave form to a brilliant structural system devised with the engineer August E. Komendant, with whom Louis Isadore Kahn collaborated on numerous projects. The laboratories were constructed of precast, post-tensioned reinforced concrete, a system that permitted large flexible laboratory spaces. The servant spaces containing stairs and exhaust chimneys become monumental brick towers attached to the perimeter of the cellular laboratory spaces The towers form a silhouette complementing the chimneys and towers of the neighboring collegiate Gothic dormitories, and in an abstract guise they suggest the towers of medieval Italian towns that Louis Isadore Kahn admired. In the design of the Salk Institute. Louis Isadore Kahn gives further expression to servant spaces with a 9-ft-high mechanical floor sandwiched between laboratory floors Much more than the demonstration of service spaces, the Salk Institute is an example of Louis Isadore Kahn 's desire to give form to the institutions of man. In a spectacular setting overlooking the Pacific Ocean, two long laboratory wings flank a stonepaved plaza bisected by a narrow rill. In accord with the wishes of the patron and founder, Dr. Jonas Salk, Louis Isadore Kahn created an environment where the interdependency of scientific and humanistic disciplines could be realized.

While Louis Isadore Kahn exhibited a compelling concern for structure, Louis Isadore Kahn sought to infuse his buildings with the symbolic meaning of the institutions they housed. Composed of austere geometries, his spaces are intended to evoke an emotional, empathetic response. "Architecture," Kahn said, "is the thoughtful making of spaces" (1). Beyond its functional role, Louis Isadore Kahn believed architecture must also evoke the feeling and symbolism of timeless human values. Louis I. Kahn attempted to explain the relationship between the rational and romantic dichotomy in his "form-design" thesis, a theory of composition articulated in 1959. In his personal philosophy, form is conceived as formless and unmeasur-able, a spiritual power common to all mankind. It transcends individual thoughts, feelings, and conventions.

Form characterizes the conceptual essence of one project from another, and thus it is the initial step in the creative process. Design, however, is measurable and takes into consideration the specific circumstances of the program. Practical and functional concerns are contained in design. The union of form and design is realized in the final product, and the building's symbolic meaning is once again unmeasurable.

The Phillips Exeter Academy Library at Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire is the

largest secondary school library in the world. Built by renowned architect Louis Kahn, it is widely

recognized as an architectural masterpiece of international significance. Its most notable feature is a

dramatic atrium with enormous circular openings that reveal several floors of book stacks.

Contents

[hide]

1 History

2 Choosing Louis Kahn as architect

3 Architecture

4 Architectural interpretations

5 Recognition

6 References

7 External links

[edit]History

The first library at Phillips Exeter Academy was a single small room. A member of the class of 1833

remembered it as containing "old sermons and some history, scarcely ever read." Even as late as

1905 the library had only two rooms and 2000 volumes.

In 1912 the richly furnished Davis Library was added to the campus with space for 5000 volumes.

Although a major improvement, its atmosphere was inhospitable by today's standards. Stacks were

locked to students. The librarian's office was located at the entrance to the stacks to maximize control

over entry. Decisions about library programs and book selections were in the hands of an all-male

faculty committee instead of the female library staff.

In 1950 Rodney Armstrong became librarian, the first with a graduate degree in library science. One

of his first moves was to open the stacks to students. That solved one problem, but the real difficulty

was the lack of space. The library contained 35,000 volumes at that point, many of them stored in

cardboard boxes for lack of shelf room. After years of effort, Armstrong eventually succeeded in

bringing a new library to the academy.[1]

Renowned architect Louis Kahn was chosen to design the new library in 1965 and it was ready for

occupancy in 1971.[2]:390,394 The building is widely recognized as an architectural masterpiece.

Influential architectural historian Vincent Scully, for example, used a photo of it as the frontispiece for

his book Modern Architecture and Other Essays.[3]

On November 16, 1971, classes were suspended for a day, and students, faculty, and staff moved

books (the library had 60,000 volumes by this time) from the old Davis Library into the new library.[4]:204

Henry Beford, who became librarian shortly after the new library was occupied, supervised the

transition not only to the new building but also to a new way of operating a library. Staff librarians were

encouraged to see themselves as co-instructors with the regular faculty and to put less emphasis on

shushing library patrons. A piano was installed and the library began sponsoring lectures and

concerts.

In 1977 Jacquelyn Thomas became librarian, the first with full faculty status. Today she oversees a

staff of seven, all with graduate degrees in library science.[1] During Thomas' tenure the library's

collection and programming grew to a size appropriate to a small liberal arts college. Today the library

houses 160,000 volumes on nine levels and has a shelf capacity of 250,000 volumes,[5] making it the

largest secondary school library in the world.[6] [7] The library also contains a collection of works by

alumni/ae as well as the Academy Archives.

The library was the first building on campus to be computerized thanks to the foresight of Armstrong

and Kahn, who made sure the library had sufficient conduit space for the cabling needed by the

coming computer revolution.[1]

In 1995, the library was officially named the Class of 1945 Library, honoring Dr. Lewis Perry, Exeter's

eighth principal (1914–1946).[5]

[edit]Choosing Louis Kahn as architect

Exeter Library atrium with crossbeams above and circular double staircase below

The project to build a new and larger library began in 1950 and progressed slowly for several years.

By the mid-1960s, O'Connor & Kilham, the architectural firm that had designed libraries

for Barnard, Amherst and West Point,[1]:26 had been chosen and had drafted plans for a new building

with traditional architecture.[4]:184 Richard Day arrived as the new principal of the academy at that point,

however, and found their design to be unsatisfactory. He dismissed the architects, declaring his

intention to hire "the very best contemporary architect in the world to design our library".[4]:184

The school's building committee was tasked with finding a new architect. Influential members of the

committee became interested in Louis Kahn at an early stage, but they interviewed several other

prominent architects as well, including Paul Rudolph, I. M. Pei, Philip Johnson and Edward Larrabee

Barnes.[2]:390Kahn's prospects received a boost when Jonas Salk, whose son had attended Exeter,

called Armstrong and invited him to visit the Salk Institute in California, which Kahn had recently built

to widespread acclaim. Kahn was awarded the commission for the library in November 1965.[4]:186

Kahn had already thought deeply about the proper design for a library, having earlier submitted

proposals for a new library at Washington University.[8]:305 He also expressed a deep reverence for

books, saying, "A book is tremendously important. Nobody ever paid the price of a book, they only

paid for the printing".[9]:290 Describing the book as an offering, Kahn said, "How precious a book is in

light of the offering, in light of the one who has the privilege of the offering. The library tells you of this

offering".[10]

The building committee carefully considered what they wanted in a new library and presented their

ideas to Kahn in an unusually detailed document that went through more than fifty drafts.[4]:187

The early designs included some items that were eventually rejected, such as a roof garden and two

exterior towers with stairs that were open to the weather. They were removed from the plans when the

building committee reminded Kahn that neither of those features would be practical in New England

winters.[4]:189

[edit]Architecture

The building committee's document specified that the new library should be "unpretentious, though in

a handsome, inviting contemporary style".[11] Kahn accordingly made the building's exterior relatively

undramatic, suitable for a small New England town. Its facade is primarily brick with teak wood panels

at most windows marking the location of a pair of wooden carrels. The bricks are load-bearing; that is,

the weight of the outer portion of the building is carried by the bricks themselves, not by a hidden steel

frame. Kahn calls this fact to the viewer's attention by making the brick piers noticeably thicker at the

bottom where they have more weight to bear. The windows are correspondingly wider toward the top

where the piers are thinner.[8]:309 Kahn said, "The weight of the brick makes it dance like a fairy above

and groan below."[12]

Exeter Library Exterior

The corners of the building are chamfered (cut off), allowing the viewers to see the outer parts of the

building's structure. The Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects says, "Kahn sometimes perceived a

building as enclosed by 'plate-walls,' and to give emphasis to this structural form, he interrupted the

plates at the corner, leaving a gap between them. The Library at Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter,

New Hampshire (1967–1972) is a classic example".[13]:540

Many of Kahn's buildings have something about them that evokes the timeless atmosphere of the

European and Egyptian ruins he studied so intently. Kahn expressed this concept here with the

unfinished appearance created by the chamfered corners and the uppermost part of the building,

which from the ground looks something like a deserted floor with empty window frames.[14]:12

A shadowed arcade circles the building on the ground floor. The entrance is definitely not a focal point

of the building; first-time visitors must often hunt to find it. The original design called for landscaping

with a paved forecourt that would have indicated the entrance without disrupting the symmetry of

the facade.[4]:191Architectural historian William Jordy said, "Perverse as the hidden entrance may

seem, it emphatically reinforces Kahn's statement that his design begins on the periphery with the

circle of individual carrels, each with its separate window."[15]

Exeter Library atrium with edge of circular stairway at lower right

A circular double staircase built from concrete and faced with travertine greets the visitor upon entry

into the library. At the top of the stairs the visitor enters a dramatic central hall with enormous circular

openings that reveal several floors of book stacks. At the top of the atrium, two massive concrete

cross beams diffuse the light entering from the clerestory windows.

Carter Wiseman, author of Louis Kahn: Beyond Time and Style, said, "The many comparisons of the

experience of entering Exeter's main space to that of entering a cathedral are not accidental. Kahn

clearly wanted the students to be humbled by the sense of arrival, and he succeeded."[4]:194 David

Rineheart, who worked as an architect for Kahn, said, "for Lou, every building was a temple. Salk was

a temple for science. Dhaka was a temple for government. Exeter was a temple for learning."[4]:180

Because the stacks are visible from the floor of the central hall, the layout of the library is clear to the

visitor at a glance, which was one of the goals the Academy's building committee had set for Kahn.[11]

The central room is 52 feet (15.8 m) high, as measured from the floor to the beginning of the roof

structure, and 32 feet (9.8 m) wide. Those dimensions approximate a ratio known as the Golden

Section, which was studied by the ancient Greeks and has been considered the ideal architectural

ratio for centuries.[8]:309

Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci

The circle and the square that are combined so dramatically in the atrium were considered to be the

paradigmatic geometric units by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius.[2]:129 He also noted that the

human body is proportioned so that it can fit in both shapes, a concept that was famously expressed

with a combined circle and square byLeonardo da Vinci in his drawing Vitruvian Man.

The library is constructed in three concentric areas (Kahn called them "doughnuts").[16]:87 In the words

of Robert McCarter, author of Louis I. Kahn, "From the very beginning of the design process, Kahn

conceived of the three types of spaces as if they were three buildings constructed of different

materials and of different scales – buildings-within-buildings".[8]:306 The outer area, which houses the

reading carrels, is made of brick. The middle area, which contains the heavy book stacks, is made

of reinforced concrete. The inner area is the atrium.

The outer "building," which holds the carrels, consists of four brick structures, each of them 16 feet

(4.9 m) deep and each acting as one of the four outside walls. Figure 6 in an academic paper

called "The Tectonic Integration of Louis I. Kahn′s Exeter Library" provides a helpful exploded view

drawing of the library's constituent parts.[17] The shape of the four brick carrel structures can also be

seen from outside the library at the chamfered corners. They are built with load-bearing brick, a style

of construction whose heavy internal structural elements help to create the cloistered atmosphere that

Kahn felt was appropriate for library carrels.[8]:305

The specifications of the Academy's building committee called for a large number of carrels (the

library has 210[5]) and for the carrels to be placed near windows so they could receive natural light.

[2]:390 The latter point matched Kahn's personal inclinations perfectly because he himself strongly

preferred natural light: "He is also known to have worked by a window, refusing to switch on an

electric light even on the darkest of days."[18] Each pair of carrels has a large window above, and each

individual carrel has a small window at desk height with a sliding panel for adjusting the light.

The placement of carrel spaces at the periphery was the product of thinking that began years earlier

when Kahn submitted proposals for a new library at Washington University. There he dispensed with

the traditional arrangement of completely separate library spaces for books and readers, usually with

book stacks on the periphery of the library and reading rooms toward the center. Instead he felt that

reading spaces should be near the books and also to natural light.[8]:304 For Kahn, the essence of a

library was the act of taking a book from a shelf and walking a few steps to a window for a closer look:

"A man with a book goes to the light. A library begins that way. He will not go fifty feet away to an

electric light."[9]:76 Each carrel area is associated with two levels of book stacks, with the upper level

structured as a mezzanine that overlooks the carrels. The book stacks also look out into the atrium.

The library's heating and cooling needs are supplied by the nearby dining hall, which Kahn built at the

same time as the library.[4]:202

[edit]Architectural interpretations

The interpretations of Kahn's design offered by architectural experts sometimes vary in interesting

ways:

Massive cross beams that diffuse the light at the top of the atrium

Cross braces: There is general agreement that the role of the massive cross braces at the top of the

atruim is to provide structural strength and also to diffuse the light. Kahn scholar Sarah Goldhagen,

however, thinks there is more to the story than that: "the concrete X-shaped cross below the skylit

ceiling at the Exeter Library is grossly exaggerated for dramatic effect."[19] Professor Kathleen James-

Chakraborty goes even further: "Above, in the most sublime gesture of all, floats a concrete cross

brace, illuminated by clerestory windows. Its weight, which appears ready to come crashing down

upon the onlooker, revives the sense of threat dissipated elsewhere by the reassuring familiarity of the

brick skin and wood details".[16]:87 Kahn similarly floated a massive concrete structure in the ceiling of

the First Unitarian Church of Rochester, which he designed a few years earlier.

Ruins: Several scholars have noted that Kahn deliberately introduced elements into several of his

buildings that give them the ageless atmosphere of ruins. Kahn himself spoke of "wrapping ruins

around buildings," although in the context of another project.[14]:10 In his essay "Louis I. Kahn and the

Ruins of Rome,"Vincent Scully, a prominent supporter of this interpretation, said, "And in his library at

Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, Kahn won't even let it become a building; he wants it to

remain a ruin. The walls don't connect at the top. They remain like a hollow shell..."[14]:12 Architect and

Kahn scholarRomaldo Giurgola, on the other hand, avoids this interpretation in the entry he wrote for

Louis Kahn in the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects. In it, while discussing the arrangement of

exterior elements of Kahn's National Assembly Building of Bangladesh, Giurgola wrote, "This

relationship with daylight was the determining element behind this solution, rather than the formal

desire to 'create ruins,' as some critics have suggested." In the very next paragraph Guirgola

describes the chamfered corners of the library at Phillips Exeter by saying only that Kahn used this

device to show that the structural importance of the corner is greatly reduced in buildings like the

Exeter library that are constructed with reinforced concrete and other modern materials.[13]:540

[edit]Recognition

In 1997 the American Institute of Architects gave the library their Twenty-five Year Award for

architecture of enduring significance, which is given to no more than one building per year.

In 2005 the United States Postal Service issued a stamp that recognized the library as one of

twelve Masterworks of Modern American Architecture.[20]

In 2007, the library was ranked #80 on the List of America's Favorite Architecture by the American

Institute of Architects.

[edit]References

1. ^ a b c d Clark, Susannah (2006). "An Open Book". The Exeter Bulletin (Phillips Exeter Academy)

(Winter).

2. ^ a b c d Brownlee, David; David De Long (1991). Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture. New York:

Rizzoli International Publications. ISBN 0-8478-1330-4.

3. ̂ Scully, Vincent (2003). Modern Architecture and Other Essays. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press. ISBN 0-691-07441-0.

4. ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wiseman, Carter (2007). Louis I. Kahn. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-73165-0.

5. ^ a b c "About the Library". Phillips Exeter Academy. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

6. ̂ Fabrikant, Geraldine (Jan 26, 2008). "At Elite Prep Schools, College-Size Endowments". New York

Times.

7. ̂ http://www.petersons.com/collegeprofiles/Profile.aspx?inunid=17407&reprjid=17 "Peterson's – Philips

Exeter Academy"

8. ^ a b c d e f McCarter, Robert (2005). Louis I. Kahn. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-4045-9.

9. ^ a b Kahn, Louis; Alessandra Latour (1991). Louis I. Kahn: Writings, lectures, interviews. New York:

Rizzoli International Publications. ISBN 978-0-8478-1356-8.

10. ̂ Wurman, Richard Saul, ed (1986). What Will Be Has Always Been: The Words of Louis I. Kahn. New

York: Rizzoli International Publications. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-8478-0606-5. (as quoted in Robert

McCarter's Louis I. Kahn, page 304)

11. ^ a b "Design of the Library". Phillips Exeter Academy. Retrieved Feb 8, 2011.

12. ̂ Huxtable, Ada Louise (2008). On Architecture: Collected Reflections on a Century of Change. New

York: Walker Publishing Company. p. 190. ISBN 978-0802717078.

13. ^ a b Placzek, Adolf, ed (1982). "Louis Kahn". Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects. New York: Collier

MacMillan. ISBN 0-02-925010-2.

14. ^ a b c Scully, Vincent (1993). Louis I. Kahn and the Ruins of Rome. California Institute of Technology.

15. ̂ Jordy, William (2005). Symbolic Essence and Other Writings on Modern Architecture and American

Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 254. ISBN 0-300-09448-5.

16. ^ a b James-Chakraborty, Kathleen (2004). "Our Architect". The Exeter Bulletin (Phillips Exeter

Academy) (Spring).

17. ̂ "The Tectonic Integration of Louis I. Kahn′s Exeter Library". Journal of Asian Architecture and Building

Engineering 9 (1): 31–37. 1910.

18. ̂ Fleming, Steven (2006). "Theorising Daylight: Kahn's Unitarian Church and Plato's Super-Form, The

Good". arq: Architectural Research Quarterly (Cambridge University Press) 10 (1):

25.doi:10.1017/S1359135506000091.

19. ̂ Goldhagen, Sarah (2001). Louis Kahn's Situated Modernism. New Haven, Conn: Yale University

Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-300-07786-5.

20. ̂ "Architectural Excellence Receives Stamps of Approval from the Postal Service". US Postal Service.

Retrieved June 3, 2010

Louis Isadore Kahn (born Itze-Leib Schmuilowsky) (February 20, 1901 or 1902 – March 17, 1974)

was a world-renowned American architect of Estonian Jewish origin,[1] based

in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. After working in various capacities for several firms in

Philadelphia, he founded his own atelier in 1935. While continuing his private practice, he served as a

design critic and professor of architecture at Yale School of Architecture from 1947 to 1957. From

1957 until his death, he was a professor of architecture at the School of Design at the University of

Pennsylvania. Influenced by ancient ruins, Kahn's style tends to the monumental and monolithic; his

heavy buildings do not hide their weight, their materials, or the way they are assembled.

Contents

[hide]

1 Biography

o 1.1 Early life

o 1.2 Career

o 1.3 Death

o 1.4 Personal life

2 Important works

3 Timeline of works

4 Legacy

5 Gallery

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

[edit]Biography

[edit]Early life

Jesse Oser House, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania (1940)

Louis Kahn, whose original name was Itze-Leib (Leiser-Itze) Schmuilowsky (Schmalowski), was born

into a poor Jewish family in Pärnu and spent the rest of his early childhood in Kuressaare on

the Estonian island of Saaremaa, then part of the Russian Empire. At age 3, he saw coals in the stove

and was captivated by the light of the coal. He put the coal in an apron which later seared his face.

[2] He carried these scars for the rest of his life.[3]

In 1906, his family immigrated to the United States, fearing that his father would be recalled into the

military during the Russo-Japanese War. His actual birth year may have been inaccurately recorded

in the process of immigration. According to his son's documentary film in 2003[4] the family couldn't

afford pencils but made their own charcoal sticks from burnt twigs so that Louis could earn a little

money from drawings and later by playing piano to accompany silent movies. He became

a naturalized citizen on May 15, 1914. His father changed their name in 1915.

[edit]Career

He trained in a rigorous Beaux-Arts tradition, with its emphasis on drawing, at the University of

Pennsylvania. After completing his Bachelor of Architecture in 1924, Kahn worked as senior

draftsman in the office of City Architect John Molitor. In this capacity, he worked on the design for

the 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition.[5]

In 1928, Kahn made a European tour and took a particular interest in the medieval walled city

of Carcassonne, France and the castles of Scotland rather than any of the strongholds

of classicism or modernism.[6] After returning to the States in 1929, Kahn worked in the offices of Paul

Philippe Cret, his former studio critic at the University of Pennsylvania, and in the offices

of Zantzinger, Borie and Medary in Philadelphia.[5] In 1932, Kahn and Dominique Berninger founded

the Architectural Research Group, whose members were interested in the populist social agenda and

new aesthetics of the European avant-gardes. Among the projects Kahn worked on during this

collaboration are unbuilt schemes for public housing that had originally been presented to the Public

Works Administration.[5]

Among the more important of Kahn's early collaborations was with George Howe.[7] Kahn worked with

Howe in late 1930s on projects for the Philadelphia Housing Authority and again in 1940, along with

German-born architect Oscar Stonorov for the design of housing developments in other parts

of Pennsylvania.[8]

The National Assembly Building (Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban) ofBangladesh

Kahn did not find his distinctive architectural style until he was in his fifties. Initially working in a fairly

orthodox version of the International Style, a stay at the American Academy in Rome in the early

1950s marked a turning point in Kahn's career. The back-to-the-basics approach he adopted after

visiting the ruins of ancient buildings in Italy, Greece, and Egypt helped him to develop his own style

of architecture influenced by earlier modern movements but not limited by their sometimes dogmatic

ideologies.

In 1961 he received a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts to

study traffic movement [9] [10] in Philadelphia and create a proposal for a viaduct system. He describes

this proposal at a lecture given in 1962 at the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado:

In the center of town the streets should become buildings. This should be interplayed with a sense of

movement which does not tax local streets for non-local traffic. There should be a system of viaducts

which encase an area which can reclaim the local streets for their own use, and it should be made so

this viaduct has a ground floor of shops and usable area. A model which I did for the Graham

Foundation recently, and which I presented to Mr. Entenza, showed the scheme.[11]

Kahn's teaching career began at Yale University in 1947, and he was eventually named Albert F.

Bemis Professor of Architecture and Planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1962

and Paul Philippe Cret Professor of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania in 1966 and was

also a Visiting Lecturer at Princeton University from 1961 to 1967. Kahn was elected a Fellow in

the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1953. He was made a member of the National Institute of

Arts and Letters in 1964. He was awarded the Frank P. Brown Medalin 1964. He was made a

member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1968 and awarded the AIA Gold Medal,

the highest award given by the AIA, in 1971[12] and the Royal Gold Medal by the RIBA in 1972.

[edit]Death

In 1974, Kahn died of a heart attack in a men's restroom in Pennsylvania Station in New York.[13] He

went unidentified for three days because he had crossed out the home address on his passport. He

had just returned from a work trip to Bangladesh, and despite his long career, he was deeply in debt

when he died.

[edit]Personal life

Kahn had three different families with three different women: his wife, Esther, whom he married in

1930; Anne Tyng, who began her working collaboration and personal relationship with Kahn in 1945;

and Harriet Pattison. His obituary in the New York Times, written by Paul Goldberger, mentions only

Esther and his daughter by her as survivors. But in 2003, Kahn's son with Pattison, Nathaniel Kahn,

released an Oscar-nominated biographical documentary about his father, titled My Architect: A Son's

Journey, which gives glimpses of the architecture while focusing on talking to the people who knew

him: family, friends, and colleagues. It includes interviews with renowned architect contemporaries

such as B. V. Doshi, Frank Gehry, Ed Bacon, Philip Johnson, I. M. Pei, and Robert A. M. Stern, but

also an insider's view of Kahn's unusual family arrangements. The unusual manner of his death is

used as a point of departure and a metaphor for Kahn's "nomadic" life in the film.

[edit]Important works

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas (1966–72)

Yale University Art Gallery , New Haven, Connecticut,(1951–1953), the first significant commission

of Louis Kahn and his first masterpiece, replete with technical innovations. For example, he

designed a hollow concrete tetrahedral space-frame that did away with the need for ductwork and

reduced the floor-to-floor height by channeling air through the structure itself. Like many of Kahn's

buildings, the Art Gallery makes subtle references to its context while overtly rejecting any

historical style.

Richards Medical Research Laboratories , University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

(1957–1965), a breakthrough in Kahn's career that helped set new directions for modern

architecture with its clear expression of served and servant spaces and its evocation of the

architecture of the past.

The Salk Institute, La Jolla, California, (1959–1965), was to be a campus composed of three main

clusters: meeting and conference areas, living quarters, and laboratories. Only the laboratory

cluster, consisting of two parallel blocks enclosing a water garden, was actually built. The two

laboratory blocks frame an exquisite view of the Pacific Ocean, accentuated by a thin linear

fountain that seems to reach for the horizon.

First Unitarian Church , Rochester, New York (1959–1969), named as one of the greatest religious

structures of the 20th century by Paul Goldberger, Pulitzer Prize-winning architectural critic.

[14] Tall, narrow window recesses create an irregular rhythm of shadows on the exterior while four

light towers flood the sanctuary walls with indirect natural light.

Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad , in Ahmedabad, India (1962).

Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban (National Assembly Building) in Dhaka, Bangladesh (1962–1974),

considered to be his masterpiece and one of the great monuments of International Modernism.

Phillips Exeter Academy Library , Exeter, New Hampshire, (1965–1972), awarded the Twenty-five

Year Award by the American Institute of Architects in 1997. It is famous for its dramatic atrium

with enormous circular openings into the book stacks.

Kimbell Art Museum , Fort Worth, Texas, (1967–1972), features repeated bays of cycloid-shaped

barrel vaults with light slits along the apex, which bathe the artwork on display in an ever-

changing diffuse light.

Yale Center for British Art , Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, (1969–1974).

Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park , Roosevelt Island, New York, (1972–1974), unbuilt.

[edit]Timeline of works

Interior of Phillips Exeter Academy Library, Exeter, New Hampshire (1965–72)

All dates refer to the year project commenced

1935 – Jersey Homesteads Cooperative Development, Hightstown, New Jersey

1940 – Jesse Oser House, 628 Stetson Road, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania

1947 – Phillip Q. Roche House, 2101 Harts Lane, Conshohocken, Pennsylvania

1951 – Yale University Art Gallery, 1111 Chapel Street, New Haven, Connecticut

1952 – City Tower Project, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (unbuilt)

1954 – Jewish Community Center (aka Trenton Bath House), 999 Lower Ferry Road, Ewing, New

Jersey

1956 – Wharton Esherick Studio, 1520 Horseshoe Trail, Malvern, Pennsylvania (designed

with Wharton Esherick)

1957 – Richards Medical Research Laboratories, University of Pennsylvania, 3700 Hamilton

Walk, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

1957 – Fred E. and Elaine Cox Clever House, 417 Sherry Way, Cherry Hill, New Jersey

1959 – Margaret Esherick House, 204 Sunrise Lane, Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[15]

1958 – Tribune Review Publishing Company Building, 622 Cabin Hill Drive, Greensburg,

Pennsylvania

1959 – Salk Institute for Biological Studies, 10 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California

1959 – First Unitarian Church, 220 South Winton Road, Rochester, New York

1960 – Erdman Hall Dormitories, Bryn Mawr College, Morris Avenue, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania

1960 – Norman Fisher House, 197 East Mill Road, Hatboro, Pennsylvania

1961 – Point Counterpoint II, barge used by the American Wind Symphony Orchestra

1962 – Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India

1962 – National Assembly Building, Dhaka, Bangladesh

1963 – President's Estate, Islamabad, Pakistan (unbuilt)

1965 – Phillips Exeter Academy Library, Front Street, Exeter, New Hampshire

1966 – Kimbell Art Museum, 3333 Camp Bowie Boulevard, Fort Worth, Texas

1966 – Olivetti-Underwood Factory, Valley Road, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

1968 – Hurva Synagogue, Jerusalem, Israel (unbuilt)

1969 – Yale Center for British Art, Yale University, 1080 Chapel Street, New Haven, Connecticut

1971 – Steven Korman House, Sheaff Lane, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania

1972 – Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, Roosevelt Island, New York City, New York

(unbuilt)[16]

1973 – The Arts United Center,(Formerly known as the Fine Arts Foundation Civic Center) Fort

Wayne, Indiana [17]

[edit]Legacy

360° panorama in the courtyard of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, California (1959–65).

Louis Kahn Memorial Park, 11th & Pine Streets, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Louis Kahn's work infused the International style with a fastidious, highly personal taste, a poetry of

light. His few projects reflect his deep personal involvement with each. Isamu Noguchi called him "a

philosopher among architects." He was known for his ability to create monumental architecture that

responded to the human scale. He was also concerned with creating strong formal distinctions

between served spaces and servantspaces. What he meant by servant spaces was not spaces for

servants, but rather spaces that serve other spaces, such as stairwells, corridors, restrooms, or any

other back-of-house function like storage space or mechanical rooms. His palette of materials tended

toward heavily textured brick and bare concrete, the textures often reinforced by juxtaposition to

highly refined surfaces such as travertine marble.

While widely known for his spaces' poetic sensibilities, Kahn also worked closely with engineers and

contractors on his buildings. The results were often technically innovative and highly refined. In

addition to the influence Kahn's more well-known work has on contemporary architects (such

as Mazharul Islam, Tadao Ando), some of his work (especially the unbuilt City Tower Project) became

very influential among the high-tech architects of the late 20th century (such as Renzo Piano, who

worked in Kahn's office, Richard Rogers and Norman Foster). His prominent apprentices

include Mazharul Islam, Moshe Safdie, Robert Venturi, Jack Diamond.

Many years after his death, Kahn continues to inspire controversy. Interest is growing in a plan to

build a Kahn-designed Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park at the southern tip of Roosevelt

Island.[18] A New York Times editorial opined:

There's a magic to the project. That the task is daunting makes it worthy of the man it honors, who

guided the nation through the Depression, the New Deal and a world war. As for Mr. Kahn, he died in

1974, as he passed alone through New York's Penn Station. In his briefcase were renderings of the

memorial, his last completed plan.[19]

The editorial describes Kahn's plan as:

...simple and elegant. Drawing inspiration from Roosevelt's defense of the Four Freedoms – of

speech and religion, and from want and fear – he designed an open 'room and a garden' at the

bottom of the island. Trees on either side form a 'V' defining a green space, and leading to a two-

walled stone room at the water's edge that frames the United Nations and the rest of the skyline.

Critics note that the panoramic view of Manhattan and the UN are actually blocked by the walls of that

room and by the trees.[20] Other as-yet-unanswered critics have argued more broadly that not enough

thought has been given to what visitors to the memorial would actually be able to do at the site.[21] The

proposed project is opposed by a majority of island residents who were surveyed by theTrust for

Public Land, a national land conservation group currently working extensively on the island.[22]

The movement for the memorial, which was conceived by Kahn's firm almost 35 years ago, needed to

raise $40 million by the end of 2007; as of July 20, it had collected $5.1 million.[23] There is a merest

hint in Architectural Record about the often-heard argument that it must be built because it was

literally Kahn's last project;[24] and this is rebutted by those who've said the plans aren't enough like

Kahn's other work for it to be touted as a memorial to Kahn as well as FDR.[25]

• The perimeter study carrels are illuminated from windows above the reader's eye level; smaller windows at eye level afford views to the campus or conversely can be closed by a sliding wooden shutter for privacy and concentration. There is contact with and building upon origins in both the library and the [Kimbell] museum. They span time as an architecture of basic fact and of progression as we move onward, aware of both where we have come form and where we are.”

My Architect: A Son's Journey is a 2003 documentary film about the American architect Louis Kahn. Kahn led an extraordinary career and left three families behind when he died of a heart attack in a Penn Station bathroom.

One of his most memorable quotes is “When I went to high school, I had a teacher in the arts, who was head of the department of Central High, William Grey, and he gave me a course in Architecture, the only course in the high school I am sure, in Greek, Roman, Renaissance, Egyptian, and Gothic Architecture, and at that point two of my colleagues and I realized that only Architecture was to be my life, and how accidental our existences are, really, and how full of influence by

circumstance.” Louis I. Kahn, quote from the documentary film “My Architect, A Son’s Journey” a film by his son Nathaniel Kahn.

The film was made by Louis Kahn's illegitimate son Nathaniel Kahn, and features interviews with many giants of modern architecture, including I.M. Pei,Anne Tyng and Philip Johnson. Throughout the film, Kahn visits all of his father's buildings including Yale Center for British Art, Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban and the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad.

My Architect was nominated for the 2003 Academy Award for Documentary Feature. [1]

[edit]

![1969 LOUIS I KAHN And [the artist gets inspiration] also ... LOUIS I KAHN Silence and Light Quiet and enigmatic, Louis I Kahn (b /90 I, Oeste/, Estonia, d /97 4)was probably the most](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5ae58e837f8b9a6d4f8b70ae/1969-louis-i-kahn-and-the-artist-gets-inspiration-also-louis-i-kahn-silence.jpg)