Locality deprivation and Type 2 diabetes incidence: A local test of relative inequalities

-

Upload

matthew-cox -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Locality deprivation and Type 2 diabetes incidence: A local test of relative inequalities

ARTICLE IN PRESS

0277-9536/$ - se

doi:10.1016/j.so

�CorrespondE-mail add

p.boyle@st-and

Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–1964

www.elsevier.com/locate/socscimed

Locality deprivation and Type 2 diabetes incidence:A local test of relative inequalities

Matthew Coxa,�, Paul J. Boylea, Peter G. Daveyb,Zhiqiang Fenga, Andrew D. Morrisb

aSchool of Geography and Geosciences, St Andrews University, Irvine Building, North Street, St Andrews, Fife KY16 9AL, UKbUniversity of Dundee, UK

Available online 24 August 2007

Abstract

There is increasing evidence that the socio-spatial context of the local area in which one lives can have an effect on

health, but teasing out contextual influences is not a simple task. We examine whether the incidence of Type 2 diabetes in

small areas in Tayside, Scotland is associated with deprivation in neighbouring areas, controlling for the deprivation of the

area itself. As such, this is a genuinely ‘contextual’ variable situating each small area in the context of surrounding places.

We test two opposing hypotheses. First, a ‘psycho-social’ hypothesis might suggest that negative social comparisons made

by individuals in relation to those who surround them could lead to chronic low-level stress via psycho-social pathways,

the physiological effects of which could promote diabetes. Thus, we would expect people living in deprived areas

surrounded by less deprived areas to have an increased risk of diabetes, compared to those living in similarly deprived

areas that are surrounded by equally or more deprived areas. Alternatively, a neo-materialist approach might suggest that

the social, cultural and environmental resources in the surrounding environment will influence circumstances in a

particular area of interest. Poorer areas surrounded by less deprived areas would benefit from the better resources in the

wider locality, while less deprived areas surrounded by poorer areas may be hampered by the poorer resources available

nearby. We refer to this as the ‘pull-up/pull-down’ hypothesis. Our results show that, as expected, area deprivation is

positively related to diabetes incidence (po0.001), whilst deprivation inequality between areas and their neighbours is

negatively related (p ¼ 0.006). Type 2 diabetes is more common in deprived areas, but lower in deprived areas that are

surrounded by relatively less deprived areas. On the other hand, less deprived areas that are surrounded by relatively more

deprived areas have higher diabetes incidence than would be expected from the deprivation of the area alone. Our model

results are consistent with a pull-up/pull-down model and lend no support to a ‘psycho-social’ interpretation at this local

scale of analysis.

r 2007 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes; Deprivation; Relative inequality; Pull-up/pull-down hypothesis; Psycho-social hypothesis; Scotland; UK

e front matter r 2007 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

cscimed.2007.05.043

ing author. Tel.: +441334 422383.

resses: [email protected] (M. Cox),

rews.ac.uk (P.J. Boyle).

Introduction

The prevalence of Type 2 diabetes is rising in theUK (Gatling et al., 1998; Harvey, Craney, & Kelly,2002) and throughout the developed world (Amos,McCarthy, & Zimmet, 1997; Passa, 2002; Wild,

ARTICLE IN PRESSM. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–19641954

Roglic, Green, Sicree, & King, 2004). It occurs whenthe cells of the body become less sensitive to theaction of the hormone insulin, when the body failsto produce enough insulin or, as is most often thecase, as a combination of these two factors. Insulinis the key hormone involved with the storage andcontrolled release of the chemical energy availablefrom food. Without insulin, glucose circulating inthe blood is not taken up by the cells, which resultsin a chronic state of hyperglycaemia (increasedblood glucose). In the short term, hyperglycaemiawill manifest in extreme tiredness, weight loss,thirst and copious urination. However in the longterm, hyperglycaemia results in micro- and macro-vascular damage and leads to a host of serioushealth problems including blindness, kidney failure,cardiovascular disease, and foot ulcers that, ifinfected, can lead to amputation. These seriousconsequences make Type 2 diabetes a key publichealth concern.

The underlying aetiology of Type 2 diabetesremains unclear, although the development ofthe condition has been shown to have a geneticcomponent (Kaprio et al., 1993). Various individualrisk factors have been identified, including poordiet and lack of exercise (UK Prospective DiabetesStudy IV, 1988) and, as with many diseases, it is wellestablished that the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes isrelated to material deprivation (Connolly, Unwin,Sherriff, Bilous, & Kelly, 2000; Evans, Newton,Ruta, MacDonald, & Morris, 2000; Meadows,1995; Whitford, Griffin, & Prevost, 2003). Morerecently, and of particular relevance to this study,national-level analysis suggests that calorie con-sumption, obesity and diabetes mortality arepositive related to income inequality in 21 devel-oped nations (Pickett, Kelly, Brunner, Lobstein, &Wilkinson, 2005), and this suggests that there maybe a relationship between the incidence of diabetesand the presence of socio-economic inequalities.

Our analysis in Tayside seeks, first, to examinewhether the incidence (rather than prevalence) ofType 2 diabetes is related to deprivation and,second, whether variations in deprivation withinthe local context also influence the incidence ofType 2 diabetes. In so doing, we present an analysiswhich examines a potentially important contextualinfluence—the role of socio-economic conditions inareas neighbouring a particular place of interest.The premise is that the local ‘socio-spatial’ contextthat one lives in has a significant impact on healthvia a complex interplay of social, cultural and

environmental interactions which take place withinand between local areas. Indeed, ‘deprivationinequalities’ within wards in England & Waleshave previously been shown to be associatedwith limiting long-term illness (Boyle, Gatrell, &Duke-Williams, 1999). This raises the intriguingquestion of whether living in a poor area sur-rounded by richer areas is better or worse for one’shealth than living in a poor area surrounded bysimilarly poor or worse off areas (Boyle, Gatrell, &Duke-Williams, 2004). Therefore, this paper ex-plores whether the incidence of Type 2 diabetes insmall areas is raised or lowered if surrounding areasare more or less deprived.

Two opposing models could be anticipated.A psycho-social interpretation might suggest thatsocial comparisons would lead to worse health inareas surrounded by better off places, other thingsbeing equal. A neo-materialist model might arguethat the proximity of less deprived areas confersmaterial advantages, which lower the incidence ofdiabetes. This analysis therefore contributes to thedebate concerning the relative importance of theseopposing theoretical positions (Adler, 2006; Lynch,2000; Lynch & Davey Smith, 2002; Lynch, DaveySmith, Kaplan, & House, 2000; Macleod, DaveySmith, Metcalfe, & Hart, 2005; Macleod, DaveySmith, Metcalfe, & Hart, 2006; Wilkinson, 1994,2000a, 2000b), and stresses the importance of localcontextual effects.

The psycho-social interpretation is informed, tosome extent, by the ‘income inequality’ debate.Income inequality refers to the difference in earn-ings between people at the top and bottom ofsociety and this type of national-level measure hasbeen associated with both mortality and morbidityoutcomes (e.g. Kaplan, Pamuk, Lynch, Cohen, &Balfour, 1996; Kennedy, Kawachi, Lochner, &Prothrow-Smith, 1996; Ross, Wolfson, Dunn,Berthelot, Kaplan, & Lynch, 2000; Sanmartinet al., 2003; Waldman, 1992; Wilkinson, 1992).Although this broad hypothesis has attractedcriticism (e.g. Deaton, 2003; Gravelle, Wildman, &Sutton, 2002), proponents argue that incomeinequality may be detrimental to health via keypsycho-social pathways associated with a person’sstanding in society, and the hypothesis has beenused to explain why substantial health inequalitiesexist in developed nations, despite the decline inabsolute poverty that most have experienced.Wilkinson (1992, 1996, 1999), a key proponent ofthe income inequality thesis, believes that in the

ARTICLE IN PRESS

1The UK Census, which is the main source of reliable socio-

economic data for small geographical areas, has never included

an income question.

M. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–1964 1955

presence of such social inequalities, poorer people indeveloped societies compare themselves unfavour-ably with the rest of society and that thiscomparison is damaging to health. The argumentcentres on social class identity within the nationalclass structure and he argues that through the socialtension and weak social affiliation resulting fromsuch comparisons, individuals who perceive them-selves as poor may experience chronic low-levelstress as a result of the psycho-social impact of theirperceived relative social position. Such low-levelstress may result in an unintentional physiologicalresponse, akin to flight-or-fight, which can affect ahost of neuroendocrinic, physiological and immu-nological variables (Brunner, 1997). This thesis isparticularly relevant to our study as over stimula-tion of the neuroendocrine pathways throughchronic stress could well influence the developmentof Type 2 diabetes (Brunner & Marmot, 1999) asthey play an important role in homeostasis and themobilisation of energy within the body. It has alsobeen suggested that, in addition to the physiologicaleffects of stress, relative poverty may have detri-mental effects on health via ‘comfort’ behaviours(e.g. smoking or high alcohol consumption) and theinability to affect positive lifestyle change as a resultof the lack of control operated over one’s own life.Other such behaviours associated with relativepoverty include sedentarism, increased calorie in-take, and poor food choice which are also thoughtto diabetogenic (Pickett et al., 2005). It thereforeseems relevant to examine the role of relativeinequalities in relation to diabetes incidence.

Most previous studies that have identified rela-tionships between health outcomes and incomeinequality have been conducted for large geogra-phical areas, such as nations (Wilkinson, 1996),American states (Kennedy, Kawachi, & Prothrow-Smith, 1996a, 1996b), or metropolitan areas (Lynchet al., 1998). Much of the income inequalityargument rests on the comparisons that individualsare expected to make with the rest of society:Wilkinson believes that social comparisons centreon social class identity within the national classstructure, which are best measured across wholesocieties. However, social comparisons may occur atdifferent scales and relate to different processes(Atkinson & Kintrea, 2004) and it seems intuitivelyplausible that people’s perception of their socialstatus and position will also be formed in relation tothose they live among in local neighbourhoods.Indeed, there is mounting evidence from multi-level

analyses of the significant role of the neighbourhoodcontext in health outcomes (Pickett & Pearl, 2001).Therefore it would seem entirely possible that thepsycho-social factors implicated in the developmentof diabetes at the societal level are also relevant inthe local context—if people compare themselves tothose in society in general, it would seem logical thatthey also compare themselves to those who livearound them, particularly if the circumstances oftheir neighbours are noticeably better or worse thantheir own.

In the absence of reliable small area income data,1

we therefore analyse ‘relative deprivation inequal-ity.’ If psycho-social factors are important at thisscale of analysis, we might expect those living indeprived areas that are surrounded by less deprivedareas to have a higher incidence of diabetes thanwould otherwise be expected, as a result of negativesocial comparisons. On the other hand, those wholive in less deprived areas that are surrounded bypoorer areas may make positive comparisons andhave lower levels of diabetes than would otherwisebe expected. This is not intended to be a direct testof the income inequality thesis, but it is clearlyinformed by similar processes.

The contrasting neo-materialistic interpretationof the effects of socio-economic inequalities onhealth would emphasise the impact of povertythroughout the life-course of an individual and theassociated under-investment within the areas inwhich they live. In this interpretation, a person’smaterial well-being and life opportunities, usuallyindicated by variables such as car ownership, homeownership and educational attainment, are held tobe the critical factors underpinning health outcomesand they are expected to be far more influential thanthe possible psychological effects of relative socialposition within a social hierarchy (Shaw, Dorling,Gordon, & Davey-Smith, 2004). From a geogra-phical perspective, the areas in which poor peoplelive have, in general, poorer physical, social andhealth infrastructures when compared to lessdeprived areas and this may be expected to havean effect on health (Macintyre, Ellaway, & Cum-mins, 2002). Building on such work, the ‘pull-up/pull-down’ hypothesis (Boyle et al., 2004; Gatrell,1997) suggests that the positive or negative socialand environmental resources in the surrounding

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 1

Data sources used to identify diabetes cases in the Diabetes Audit

and Research Tayside Scotland (DARTS) dataset

Source Details

Diabetes prescription

database

Identifies any Tayside resident

dispensed antidiabetic drugs or

diabetic monitoring devices

Hospital diabetes

clinics

Identifies Tayside residents attending a

diabetic clinic according to the four

hospital datasets used in Tayside

Mobile diabetes eye

units

Identifies Tayside residents attending

community screening for diabetic

retinopathy and includes routine data

on Type and duration of diabetes.

Every general practice in Tayside is

invited to refer all patients with

diabetes for screening

Regional biochemistry

database

Analyzes results of diagnostic blood

tests for diabetes for Tayside residents.

A positive diagnosis of diabetes in

DARTS was conferred from the

results of appropriate tests

The Scottish

Morbidity Record

(SMR1)

Identifies Tayside patients discharged

from hospital with a primary or

secondary diagnosis of diabetes

M. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–19641956

area will influence circumstances in a particular areaof interest. For example, those living in a deprivedarea that is surrounded by relatively less deprivedareas may benefit from the better local services,recreation facilities and fresh food availability,allied with greater social regard for health-promot-ing behaviours concerning diet, exercise and smok-ing in these neighbouring areas. This may lead tolower incidences of diabetes than would otherwisebe expected (‘pull-up’). On the other hand, thehealth of those in a less deprived area, which issurrounded by more deprived areas may be nega-tively influenced by the surrounding cultural, socialand environmental circumstances (‘pull-down’). Insummary, the ‘pull-up/pull-down’ hypothesis, andthe ‘psycho-social’ hypothesis as engendered bynegative social comparisons, would seem to predictopposing consequences for the geographical distri-bution of diabetes incidence resulting from thepresence of relative socio-economic inequalitiesbetween nearby small areas. By examining relativedeprivation inequality (the difference in deprivationbetween an area and surrounding nearby areas), wecan assess whether our results for diabetes incidenceare consistent with either a pull-up/pull-down or apsycho-social effect and, as such, our paper is agenuine test of one aspect of socio-spatial context.

Method

The Type 2 diabetes data used in this study aredrawn from the Diabetes Audit and ResearchTayside Scotland (DARTS) dataset (Morris et al.,1997). This dataset is the result of an ongoingproject to combine clinical diabetes-related datasetsin order to provide a comprehensive register ofpeople with diabetes in Tayside along with asso-ciated clinical data via electronic record linkage. Tomaximise the complete ascertainment of cases ofdiabetes in Tayside, DARTS incorporates datafrom a range of sources (Table 1).

The classification of diabetes type is undertakenusing the following algorithm: if the person wastreated with insulin and was 35 years or less at thetime of diagnosis they were recorded as having Type1 diabetes. If they were treated by oral hypogly-caemic agents or were over 35 years old at diagnosis(regardless of treatment), they were recorded ashaving Type 2 diabetes. However, the database hassubsequently been refined by a team of three nursefacilitators who have visited each general practise inthe region to examine the primary care records of

every patient identified with diabetes to verify boththe diagnosis and type of diabetes record onDARTS. This process of data validation hadoccurred at least twice for each of GP practiseacross the region at the point in time when the datawas extracted for this study.

It is thought that up to a million people in the UKmay have undiagnosed Type 2 diabetes (DiabetesUK, 2005), and therefore it is highly likely that therewere unascertained cases of Type 2 diabetes inTayside which were not considered in this study.However, DARTS is the most comprehensiveregister of diabetes in the UK and thus the bestpossible data source for this study.

We collected information from the DARTSdatabase on the 3917 people in Tayside with a dateof diagnosis for Type 2 diabetes recorded betweenthe 1 January 1998 and the 31 December 2001. Foreach case, we know the age, sex and residentiallocation. These cases were distributed across 3382Output Areas (the smallest areas used for thedissemination of the 2001 Census data in Scotland).Rates were highest in the urban areas, which tend tobe more deprived, and lower in more rural areas.

We modelled the distribution of cases in five agegroups (0–44 yrs; 45–54 yrs; 55–64 yrs; 65–74 yrs;75+yrs) by sex, giving 33,820 observations, using

ARTICLE IN PRESS

2We also explored whether raising distance to different powers

(steepening the distance decay effect) influenced the results,

although none improved the fit more than using distance squared.

M. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–1964 1957

negative binomial regression with the significancelevel set a priori at po0.05. This regressiontechnique is appropriate for studies of sparse data.The age- and sex-specific denominator populationsfor the Output Areas were extracted from the 2001Census. The natural log of the age- and sex-specificpopulation was included as an offset to account forthe expected increase in the number of cases withthe population size of the Output Area.

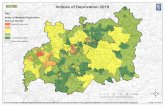

A number of independent variables were mod-elled separately and then in combination. The ageand sex variables were the only explanatory vari-ables available for the individual cases from theDARTS data; the remaining variables were allecological, having been extracted for Output Areasfrom the 2001 Census data. These included the % ofnon-white residents in the Output Area, thepopulation density of the Output Area and a seriesof variables that are typically used to measuredeprivation. These were the % of residents inhouseholds with no car; the residents in householdswith 1 or more persons per room as a % of allresidents in households (overcrowding); the % ofresidents in households with a head of household insocial class IV and V; and unemployed maleresidents aged over 16 as a proportion of allresidents aged over 16. The Carstairs DeprivationIndex (Carstairs & Morris, 1991), which is acomposite variable based on the four variablesdescribed above, was also included and is mapped inFig. 1. Many of the most deprived Output Areas arein Dundee, which is the largest city in Tayside.

Importantly, we also included a measure ofdeprivation inequality, which compared the Car-stairs deprivation score in each area with thedeprivation scores in the surrounding areas. Ratherthan simply comparing the deprivation score foreach area and its adjacent neighbours, we used agravity model approach to weight surroundingscores for each target area. The ‘influence’ of everyOutput Area in or within 20 km of Tayside (tonegate potential border effects) on the target OutputArea was measured as a function of its populationsize and the square of the distance between itspopulation-weighted centroid and that for the targetarea

I ij ¼Pi Pj

D2ij

,

where I ij denotes the influence of OAi on OAj; Pi

denotes the population of OAi; Pj denotes the

population of OAj; D2ij denotes the distance squared

between OAi and OAj .The influence of each Output Area was then

measured by dividing population by distance to givea weight, which was further divided by the sumof the weights so that the final weights for all theareas combined summed to one. By applying theseweights to their respective Output Area deprivationscore and then summing the scores, we are left withan overall locality deprivation score, whereby theOutput Areas with the greatest weight (those closeto the target area, or with a large population) hadthe greatest input.2 Thus, to derive the averagedeprivation score for the target OA (Ai) from thesurrounding areas we calculated

Ai ¼

Pkj Cj I ijPk

j I ij

,

where Cj is Carstairs deprivation score at OAj and k

is the number of surrounding OAs.To calculate deprivation inequality we subtracted

the relevant locality deprivation score from theOutput Area deprivation score of the area ofinterest. If the Output Area was more deprivedthan its surrounds then deprivation inequalitywas positive: if the area was less deprived it wasnegative.

This relative deprivation index provides a usefulcomparative variable which is genuinely ‘contex-tual.’ Many studies have used deprivation scores toreflect context. However, as Graham, Boyle, Curtis,& Moore (2004) argue, these scores are, of course,derived from the characteristics of the individualswho live in these places (see also Greenland, 2001).They are not strictly ‘contextual’ in the sense thatenvironmental measures of pollution, or accessibil-ity to health care would be (Macintyre et al., 2002)and it is not easy to determine whether anyrelationship between deprivation and health repre-sents the socio-economic ‘composition’ of indivi-duals in an area or the socio-economic ‘context’of that area. Does an ecologically-derived carownership variable (a variable that is commonlyused in the creation of deprivation indices) actas a surrogate for the affluence of the residentsin an area or does it reflect the accessibility of thearea, as those in more remote places may be forcedto own cars regardless of their income? Whether

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Fig.1.Carstairsdeprivationin

Tayside,

Scotland,2001.

M. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–19641958

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 3

Type 2 diabetes incidence (multivariate model)

Variable Parameter

estimate

Standard

error

p-value

Individual-level variables

Age

45–54 2.090241 0.0660653 o0.001

55–64 2.719943 0.0618786 o0.001

65–74 2.987469 0.0611352 o0.001

75+ 2.653115 0.0661805 o0.001

Sex (female) �0.3265832 0.0325839 o0.001

Area-level variables

Carstairs area

deprivation

0.0879695 0.0098484 o0.001

Deprivation inequality �0.0387508 0.0141039 0.006

M. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–1964 1959

deprivation should be treated as a contextualvariable is, therefore, debateable. However, therelative deprivation variable that we use here—thedifference in deprivation between an area andsurrounding nearby areas—certainly is contextual,as it compares the relative circumstances of eachplace and its surrounds.

Results

The results of a series of univariate negative bino-mial regression models for Type 2 diabetes incidenceare shown in Table 2. As expected, women were lesslikely to be diagnosed with diabetes (po0.001) andthe incidence of Type 2 diabetes increased signifi-cantly with age (po0.001). Diabetes was alsopositively and significantly related to some of thesocio-economic characteristics of the Output Areaincluding the % of residents in households withno car (po0.001), the % of residents in householdswith head of household in social classes IV and V(po0.001), unemployed male residents aged over 16as a proportion of all residents aged over 16(po0.001), and Carstairs deprivation (po0.001).However, there was no significant association withthe % of households that were overcrowded, the %of non-white residents, or population density. Depri-vation inequality was positively and significantly

Table 2

Type 2 diabetes incidence (univariate models)

Variable Parameter

estimate

Standard

error

p-value

Individual-level variables

Age

45–54 2.049512 0.0661572 o0.001

55–64 2.678852 0.061982 o0.001

65–74 2.938581 0.0612284 o0.001

75+ 2.574394 0.0662146 o0.001

Sex (female) �0.2867863 0.0412582 o0.001

Area-level variables

% households no car 0.0082165 o0.0019395 o0.001

% households

overcrowded

0.0159351 0.0090818 0.079

% low social class 0.0146561 0.0026629 o0.001

% non white ethnic

group

�0.0087938 0.0060636 0.147

% unemployment 0.0113572 0.0028155 o0.001

Carstairs area

deprivation

0.0522753 0.0076443 o0.001

Deprivation

inequality

0.0501347 0.0109731 o0.001

Population density �1.27E-08 7.98E-07 0.987

associated with the incidence of Type 2 diabetes(po0.001).

The results from a multivariate regression re-vealed an important difference to the univariateanalysis (Table 3). Age (po0.001), sex (po0.001),area deprivation (po0.001) and deprivation in-equality (p ¼ 0.006) remained significant. However,after allowing for age, sex and area deprivation, therelationship between Type 2 diabetes incidence anddeprivation inequality became negative. This sug-gests that, having controlled for area deprivation,areas surrounded by relatively less deprived areashad lower Type 2 diabetes incidence than wouldotherwise be expected, whereas areas surrounded byrelatively more deprived areas had a higher in-cidence of Type 2 diabetes than would otherwise beexpected.

Discussion

We have examined how the relative deprivationcircumstances of small areas are related to Type 2diabetes and proposed two competing hypotheses.First, the ‘psycho-social’ hypothesis would suggestthat those living in deprived areas surrounded byareas that were relatively less deprived, would havepoorer health than expected from the deprivationcircumstances of the area in which they lived. Thishypothesis builds on the work of Wilkinson andothers, who argue that income inequality withinsocieties influences the health of the worse off viathe psychological and emotional impact of living inthose circumstances. Wilkinson (2006) suggests thatthe most important psychosocial risk factors asso-ciated with inequality are low social status, weak

ARTICLE IN PRESS

3In common with the relative inequalities literature our psycho-

social interpretation focuses on comparisons of relative socio-

economic status. It is, of course, possible that people will

compare themselves across various other dimensions, perhaps

M. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–19641960

friendship networks, and the poor quality of earlychildhood experience, whilst chronic stress has beenput forward as the biological mechanism throughwhich these risk factors affect health (Wilkinson &Pickett, 2006).

Wilkinson’s arguments relate to comparisonsmade by people at the societal or national levelwhile our study explores similar issues of compar-ison but at a different spatial scale and usingmeasures of deprivation, rather than income in-equality. Wilkinson and Picket (2006), and others(Franzini, Ribble, & Spears, 2001; Hsieh & Pugh,1993; Subramanian & Kawachi, 2004) report thatincome inequality is more strongly associated withhealth when measured at the national, or possiblyregional, level, than at the local level. According toWilkinson and Pickett (2006, p. 1774), this isbecause:

income inequality in small areas is affected by thedegree of residential segregation of rich and poorand that the health of people in deprivedneighbourhoods is poorer not because of theinequality within their neighbourhoods, butbecause they are deprived in relation to the widersociety. If that is what matters, then it is to beexpected that inequality will only be sensitive tothis broader pattern of deprivation if inequality ismeasured across the wider framework in whichthe relevant social comparisons are made. Thefact that measures of inequality made acrosslarger areas are more closely related to healthbears out this pointy The lower class identity ofpeople in a poor neighbourhood is inevitablydefined in relation to a hierarchy which includesa knowledge of the existence of superior classeswho may live in other areas some distance away.

We find the focus on comparisons at the societallevel overstated. Wilkinson and Picket acknowledgethat the hierarchy, which defines people’s identitiesincludes knowledge of superior classes who live ‘inother areas some distance away,’ and, as Wilkinson(2006) recently put it:

Perhaps the underlying message is that the mostwidespread and potent kind of stress in modernsocieties centres on our anxieties about how otherssee us, on our self-doubts and social insecurities.As social beings, we continuously monitor howothers respond to us, so much so that it issometimes as if we experienced ourselves througheach other’s eyes. Shame and embarrassment

have been called the social emotions as theyshape our behaviour to meet acceptable stan-dards and spare us from the stomach-tighteningwe feel when we have made fools of ourselves infront of othersy It appears that it is also howsociety gets under the skin to affect health.

If people make comparisons with others insociety, the results of which are so powerful as tohave implications for their mental and physicalhealth, it seems reasonable to assume that peoplewould also make comparisons between themselvesand those who live around them. In Britain, at least,neighbourly comparisons with ‘the Joneses’ are awell-recognised feature of suburban life. And thereare numerous examples in the geographical litera-ture which indicate that people’s behaviours arelikely to be influenced by those who live aroundthem. We know that people tend to live close toothers with similar characteristics and that out-comes such as self-rated health (Bowling, Barber,Morris, & Shah, 2006; Stafford, Martikainen,Lahelma, & Marmot, 2004; Wen, Browning, &Cagney, 2003), cardio-vascular disease (Borrell,Roux, Rose, Catellier, & Clark, 2004; Davey Smith,Hart, Watt, Hole, & Hawthorne, 1998) and evenfertility behaviour may be strongly associated withthe local context within which people reside. Szreter(1996, p. 546), for example, puts this clearly whendiscussing historical variations in fertility patternsduring the demographic transition:

It is because fertility change was mediated byshifting roles and norms that it principallyoccurred not to whole social classes or toindividual occupations but to social groups andcommunities. This is because roles, norms andsocial identities are essential elements of theshared language of any mutually recognising,communicating human group. They are con-structed by and embodied in the shared socialpractices and values of social groups or whatmight more accurately be termed ‘communication

communities’.

Those who are prone to make comparisonsbetween themselves and others (and it seemsreasonable to suppose that this will vary dependingon a person’s personality3; see Woods, 1989) may

ARTICLE IN PRESSM. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–1964 1961

well compare themselves to others in the localneighbourhood, as well as to those in society moregenerally. People may have perceptions of theirclass identity in relation to wider society, as positedby the income inequality hypothesis, but we believethat they may also make social comparisons withothers in their local context. Wilkinson does notbelieve that local area comparisons should con-tribute to the health outcomes proposed under therelative inequality hypothesis (Wilkinson, 1997).However, if perceived relative inequality is animportant determinant of health, surely it ishard to imagine that positive or negative local

comparisons would not also impact on health—indeed, it seems to us that such local comparisonsare likely to be at least as informed and meaningfulto most people as comparisons with ‘society ingeneral.’

Our second, and opposing, ‘pull-up/pull-down’hypothesis is a more materialistic interpretation ofthe effects of socio-economic inequalities on health,which is concerned with poverty and the likelyresources available to people in the areas in whichthey live. A person’s material well-being and lifeopportunities are held to be the critical factorsunderpinning health outcomes and they are ex-pected by many to be far more influential than thepossible psychological effects of relative socialposition within a social hierarchy (Shaw et al.,2004). Thus, according to Stafford and Marmot(2003, pp. 357–358):

In a ‘collective resources model’, people in non-deprived areas have better health than people indeprived areas because there are more collectiveresources (including material and social re-sources, such as services, job opportunities, andsocial supports). The ability of wealthier, morepowerful individuals to attract high qualityamenities and services enhances the area for allresidents. The beneficial effect of living in anarea with greater collective resources may begreater for poorer individuals; they may be lessable to purchase goods and services privately andmay be more dependent on locally providedfacilities.

However, many studies, including Stafford andMarmot (2003), simply measure such local contextual

(footnote continued)

including health status (see Graham, MacLeod, Dibben, &

Johnston, 2004).

effects using a deprivation score calculated forthe particular area that a person lives in. Wesuggest that understanding the role of local circum-stances, or ‘collective resources’, on people’s healthneed not focus entirely on the characteristics of thesmall, often arbitrary administrative area in whichthey happen to reside. In addition, we argue thatthe surrounding context is likely to be influential,particularly in places that are surrounded by areasthat are relatively dissimilar—what we refer to asthe pull-up/pull-down hypothesis (Gatrell, 1997).

Thus, we explored local relative inequalities bycomparing the deprivation circumstances betweenthe place of residence and the wider locality inwhich people lived in each small area withinTayside, Scotland. Our empirical results suggestthat, controlling for the deprivation of the area ofresidence, deprivation inequality between smallareas is significantly and negatively related to anincreased incidence of Type 2 diabetes. Placessurrounded by relatively less deprived areas have alower incidence of Type 2 diabetes, whereas areassurrounded by more deprived areas have a higherincidence.

These results are compatible with a pull-up/pull-down materialist hypothesis, rather than a psycho-social hypothesis based on negative comparisons,and the mechanisms through which this may workare varied. Living nearer better off areas mighthave a range of benefits, including better access tofacilities such as reasonable food outlets, parks,health services; more employment opportunities;different social role models and so on. On the otherhand, being surrounded by worse off places mayintroduce rather more negative social, economic andcultural lifestyle influences.

Our results do not refute the validity of therelative inequality hypothesis as it is possible that itseffects are only operationalised at a societal level.Indeed, it could be argued that our results simplydemonstrate that social comparisons do not appearto matter at the local level, at least according to thismethod of measuring differences between nearbysmall places. Certainly, identifying the relevantreference group with which a person might comparethemselves is not a simple task (Atkinson &Kintrea, 2004; Dunn, Veenstra, & Ross, 2006), butit does seem to us that while those prone to makingcomparisons between themselves and others mightbe influenced by national-level social class identitiesit is also quite likely that they would be influencedby more everyday local comparisons. As Franzini

ARTICLE IN PRESSM. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–19641962

and Fernandez-Esquer (2006, p. 791); see alsoCrocker, Major, and Steele, 1998) argue:

According to contemporary stigma research,people who perceive themselves as relativelydeprived, discriminated, or stigmatized chooseas comparison targets individuals similar tothemselves because this type of comparison ismore informative and diagnostic for personalperformance.

At the very least, our results are compatible withthe argument that materialist factors may be moreinfluential than psycho-social comparisons at thisscale of analysis.

A small number of studies have also foundrelationships between health and deprivation in-equality. Ben-Shlomo, White, and Marmot (1996)reported a relationship between deprivation in-equality and mortality for (the relatively large)English local authorities. Meanwhile, Boyle et al.(1999, 2004) found relationships between depriva-tion variability and self-reported morbidity inCensus Wards in England and Wales. This studyimproves on that work by: focusing on a single,diagnosed medical condition; employing a moreaccurate and versatile measure of deprivationinequality based on a gravity model approachwhich compares deprivation between places, ratherthan simply considering the variability in depriva-tion within places; and using a measure of depriva-tion that is inherently ‘contextual’.

Our study is not, however, without problems.First, the lack of data on individuals (we only haveage and sex for people with diabetes) is a particularproblem, as it would be useful to control forindividual circumstances before assessing the impactof the local context. We also know nothing aboutthe exposure time for people in different areas andwe have shown elsewhere that health-selectivemobility can influence the relationship betweenhealth and deprivation (Boyle, Norman, & Rees,2004; Cox, Boyle, Davey, & Morris, 2007; Norman,Boyle, & Rees, 2005). However, since our focus wason small-area effects, it was impossible to find theappropriate micro-data on diabetes sufferers thatwould allow us to explore these issues. Second, itis possible that those living in areas that aresurrounded by better off places may be differentto those living in similarly deprived places that aresurrounded by worse off places; a selection effectmay be occurring. However, given that we controlfor the deprivation of each area, which is a variable

created from the socio-economic characteristics ofpeople living in places, this seems unlikely. Finally,while we have suggested that the psychosocialimpact of living in an area that is surrounded byless deprived places would be expected to have anegative effect on health, it is feasible that it mighthave exactly the opposite effect. People may feelthat being surrounded by relatively richer placesraises the social status of the wider area to whichthey belong, and hence this may have a positiveeffect on health. This is possible but, we feel, lessconvincing than our suggested interpretation. Giventhat the essence of the relative inequality hypothesissuggests that people will suffer from perceivingthemselves as being worse off than others in society,it would seem reasonable to assume that this effectwould also occur at a local level. Moreover, for aperson to make such a positive comparison wouldrequire that they had a clear impression of othersimilarly deprived areas and how those areas relateto their surrounds. Those who have moved betweensimilarly deprived areas in different contexts maybe able to make such judgements but, for others,making such a complex set of relative comparisonswould seem to be unlikely.

Overall, our results suggest that ‘collectiveresources’ in the local area are likely to have moreimpact on health than negative local-area psycho-social comparisons and, as a result, this study makesan important contribution to the debate about therelative importance of psychosocial and materiali-stic influences on health. These findings have broadpublic health implications, particularly in relation toneighbourhood planning and segregation issues.

References

Adler, N. E. (2006). When one’s main effect is another’s error:

Material vs. psychosocial explanations of health disparities.

A commentary on Macleod et al., ‘‘Is subjective social status a

more important determinant of health than objective social

status? Evidence from a prospective observational study of

Scottish men’’ (61: 9, 2005, 1916–1929). Social Science &

Medicine, 63, 846–850.

Amos, A. F., McCarthy, D. J., & Zimmet, P. (1997). The rising

global burden of diabetes and its complications: Estimates

and projections to the year 2010. Diabetic Medicine, 14(Suppl. 5),

S1–S85.

Atkinson, R., & Kintrea, K. (2004). Opportunities and despair,

it’s all in there’: Practitioner experiences and explanations of

area effects and life chances. Sociology, 38, 437–455.

Ben-Shlomo, Y., White, I. R., & Marmot, M. G. (1996). Does the

variation in the socio-economic characteristics of an area

affect mortality? British Medical Journal, 312, 1013–1014.

ARTICLE IN PRESSM. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–1964 1963

Borrell, L. N., Roux, A. V. D., Rose, K., Catellier, D., &

Clark, B. L. (2004). Neighbourhood characteristics and

mortality in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study.

International Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 398–407.

Boyle, P. J., Gatrell, A. C., & Duke-Williams, O. (1999). The

effect on morbidity of variability in deprivation and popula-

tion stability in England and Wales: An investigation at small-

area level. Social Science & Medicine, 49, 791–799.

Boyle, P. J., Gatrell, A. C., & Duke-Williams, O. (2004). Limiting

long-term illness and locality deprivation in England &Wales:

Acknowledging the ‘socio-spatial context’. In P. Boyle, S.

Curtis, E. Graham, & E. Moore (Eds.), The geographies of

health inequality in the developed world (pp. 293–308).

London: Ashgate.

Boyle, P. J., Norman, P., & Rees, P. H. (2004). Changing places.

Do changes in the relative deprivation of areas influence

limiting long-term illness and mortality among non-migrant

people living in non-deprived households? Social Science &

Medicine, 58, 2459–2471.

Bowling, A., Barber, J., Morris, R., & Shah, E. (2006). Do

perceptions of neighbourhood environment influence health?

Baseline findings from a British survey of aging. Journal of

Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 476–483.

Brunner, E. J. (1997). Stress and the biology of inequality. British

Medical Journal, 314, 558–565.

Brunner, E., & Marmot, M. (1999). Social organisation, stress,

and health. In M. Marmot, & R. G. Wilkinson (Eds.), Social

determinants of health (pp. 17–43). Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Carstairs, V., & Morris, R. (1991). Deprivation and health in

Scotland. Aberdeen University Press.

Connolly, V., Unwin, N., Sherriff, P., Bilous, R., & Kelly, W.

(2000). Diabetes prevalence and socioeconomic status:

A population based study showing increased prevalence of

Type 2 diabetes mellitus in deprived areas. Journal of

Epidemiology & Community Health, 54, 173–177.

Cox, M., Boyle, P. J., Davey, P., & Morris, A. (2007). Does

health-selective migration following diagnosis strengthen the

relationship between Type 2 diabetes and deprivation? Social

Science & Medicine, 65, 32–42.

Crocker, J., Major, B., & Steele, C. (1998). Social stigma. In

D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook

of social psychology (pp. 504–553). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Davey Smith, G., Hart, C., Watt, G., Hole, D., & Hawthorne, V.

(1998). Individual social class, area-based deprivation, cardi-

ovascular disease risk factors, and mortality: The Renfrew

and Paisley Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community

Health, 52, 399–405.

Deaton, A. (2003). Health, inequality, and economic develop-

ment. Journal of Economic Literature, 41, 113–158.

Diabetes UK (2005). Diabetes affects record numbers. /http://

www.diabetes.org.uk/news/sept05/record.htmS.

Dunn, J. R., Veenstra, G., & Ross, N. (2006). Psychosocial and

neo-material dimensions of SES and health revisited: Pre-

dictors of self-rated health in a Canadian national survey.

Social Science & Medicine, 62, 1465–1473.

Evans, J. M. M., Newton, R. W., Ruta, D. A., MacDonald, T. M.,

& Morris, A. D. (2000). Socio-economic status, obesity and

prevalence of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic

Medicine, 17, 478–480.

Franzini, L., & Fernandez-Esquer, M. E. (2006). The association

of subjective social status and health in low-income Mexican-

origin individuals in Texas. Social Science & Medicine, 63,

788–804.

Franzini, L., Ribble, J., & Spears, W. (2001). The effects of

income inequality and income level on mortality vary by

population size in Texas counties. Journal of Health and

Social Behavior, 42(4), 373–387.

Gatling, W., Budd, S., Walters, D., Mullee, M. A., Goddard, J. R.,

& Hill, R. D. (1998). Evidence of an increasing prevalence of

diagnosed diabetes mellitus in the Poole area from 1983 to

1996. Diabetic Medicine, 5, 1015–1021.

Gatrell, A. (1997). Structures of geographical and social space

and their consequences for human health. Geografiska

Annaler, 79, 141–154.

Graham, E., Boyle, P. J., Curtis, S., & Moore, E. (2004). Health

geographies in the developed world. In J. Boyle, S. Curtis, E.

Graham, & E. Moore (Eds.), The geography of health

inequalities: Views from Britain and North America

(pp. 3–36). London: Ashgate.

Graham, E., MacLeod, M., Dibben, C., & Johnston, M. (2004).

Siting wealth and illness: The case of recovery from myocardial

infarction. In P. J. Boyle, S. Curtis, E. Graham, & E. Moore

(Eds.), The geography of health inequalities: Views from Britain

and North America (pp. 351–370). London: Ashgate.

Gravelle, H., Wildman, J., & Sutton, M. (2002). Income, income

inequality and health: What can we learn from aggregate

data? Social Science & Medicine, 54, 577–589.

Greenland, S. (2001). Ecologic versus individual-level sources of

bias in ecologic estimates of contextual health effects.

International Journal of Epidemiology, 30, 1343–1350.

Harvey, J. N., Craney, L., & Kelly, D. (2002). Estimation of the

prevalence of diagnosed diabetes from primary care and

secondary care source data: Comparison of record linkage

with capture–recapture analysis. Journal of Epidemiology &

Community Health, 56, 18–23.

Hsieh, C. C., & Pugh, M. D. (1993). Poverty, income inequality,

and violent crime: A meta-analysis of recent aggregate data

studies. Criminal Justice Review, 18, 182–202.

Kaplan, G. A., Pamuk, E. R., Lynch, J. W., Cohen, R. D., &

Balfour, J. L. (1996). Inequality in income and mortality in

the United States: Analysis of mortality and potential

pathways. British Medical Journal, 312, 999–1003.

Kaprio, J., Tuomilehto, J., Koskenvuo, M., Romanov, K.,

Reunanen, A., Eriksson, J., et al. (1993). Concordance for

type 1 (insulin-dependent) and type 2 (non-insulin-dependent)

diabetes mellitus in a population-based cohort of twins in

Finland. Diabetologia, 36(5), 471–472.

Kennedy, B. P., Kawachi, B. P., Lochner, L., & Prothrow-Smith, D.

(1996). Social capital, income inequality and mortality.

American Journal of Public Health, 87, 1491–1498.

Kennedy, B. P., Kawachi, B. P., & Prothrow-Smith, D. (1996a).

Income distribution and mortality cross sectional ecological

study of the Robin Hood index in the United States. British

Medical Journal, 312, 1004–1007.

Kennedy, B. P., Kawachi, B. P., & Prothrow-Smith, D. (1996b).

Important corrections. British Medical Journal, 312, 1194.

Lynch, J. W. (2000). Income inequality and health: Expanding

the debate. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 1001–1005.

Lynch, J. W., & Davey Smith, G. (2002). Commentary: Income

inequality and health: The end of the story? International

Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 549–551.

Lynch, J. W., Davey Smith, G., Kaplan, G., & House, J. (2000).

Income inequality and mortality: Importance to health of

ARTICLE IN PRESSM. Cox et al. / Social Science & Medicine 65 (2007) 1953–19641964

individual income, psychosocial environment, or material

conditions. British Medical Journal, 320, 1200–1204.

Lynch, J. W., Kaplan, G. A., Pamuk, E. R., Cohen, R. D.,

Heck, K. E., Balfour, J. L., et al. (1998). Income inequality

and mortality in metropolitan areas of the United States.

American Journal of Public Health, 88, 1074–1080.

Macintyre, S., Ellaway, A., & Cummins, S. (2002). Place effects

on health: How can we conceptualise, operationalise and

measure them? Social Science & Medicine, 55, 125–139.

Macleod, J., Davey Smith, G., Metcalfe, C., & Hart, C. (2005). Is

subjective social status a more important determinant of

health than objective social status? Evidence from a prospec-

tive observational study of Scottish men. Social Science &

Medicine, 61, 1916–1929.

Macleod, J., Davey Smith, G., Metcalfe, C., & Hart, C. (2006).

Subjective and objective status and health: A response to

Adler’s ‘‘When one’s main effect is another’s error: Material

vs. psychosocial explanations of health disparities. A com-

mentary on Macleod et al., ‘‘Is subjective social status a more

important determinant of health than objective social status?

Evidence from a prospective observational study of Scottish

men’’ (61(9), 2005, 1916–1929). Social Science & Medicine, 63,

851–857.

Meadows, P. (1995). Variations of diabetes mellitus prevalence in

general practice and its relation to deprivation. Diabetic

Medicine, 12, 696–700.

Morris, A. D., Boyle, D. I. R., MacAlpine, R., Emslie-Smith, A.,

Jung, R. T., Newton, R. W., et al. (1997). The diabetes audit

and research in Tayside Scotland (DARTS) study: Electronic

record linkage to create a diabetes register. British Medical

Journal, 315, 524–528.

Norman, P., Boyle, P. J., & Rees, P. (2005). Selective migration,

health and deprivation: A longitudinal analysis. Social

Science & Medicine, 60, 2755–2771.

Passa, P. (2002). Diabetes trends in Europe. Diabetes metabolism

research and reviews, 18(Suppl. 3), S2–S8.

Pickett, K. E., Kelly, S., Brunner, E., Lobstein, T., &

Wilkinson, R. G. (2005). Wider income gaps, wider waist-

bands? An ecological study of obesity and income inequality.

Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(8), 670–674.

Pickett, K. E., & Pearl, M. (2001). Multilevel analyses of

neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes:

A critical review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community

Health, 55, 111–122.

Ross, N. A., Wolfson, N. G., Dunn, J. R., Berthelot, J.-M.,

Kaplan, G. A., & Lynch, J. W. (2000). Relation between

income inequality and mortality in Canada and in the United

States: Cross sectional assessment using census data and vital

statistics. British Medical Journal, 320, 898–902.

Sanmartin, C., Ross, N. A., Tremblay, S., Wolfson, M.,

Dunn, J. R., & Lynch, J. W. (2003). Labour market income

inequality and mortality in North American metropolitan

areas (research report). Journal of Epidemiology and Commu-

nity Health, 57, 792–797.

Shaw, M., Dorling, D., Gordon, D., & Davey-Smith, G. (2004).

The widening gap—Health inequalities in Britain at the end

of the twentieth century. In P. Boyle, S. Curtis, E. Graham,

& E. Moore (Eds.), The geographies of health inequality in the

developed world (pp. 77–100). London: Ashgate.

Stafford, M., & Marmot, M. (2003). Neighbourhood deprivation

and health: Does it affect us all equally? International Journal

of Epidemiology, 32, 357–366.

Stafford, M., Martikainen, P., Lahelma, E., & Marmot, M.

(2004). Neighbourhoods and self rated health: A comparison

of public sector employees in London and Helsinki. Journal of

Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 772–778.

Subramanian, S. V., & Kawachi, I. (2004). Income inequality and

health: What have we learned so far? Epidemiologic Review,

26, 78–91.

Szreter, S. (1996). Fertility, class, and gender in Britain

1860– 1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study IV. (1988). Characteristics of

newly presenting type 2 diabetic patients: Male preponder-

ance and obesity at different ages: Multi-centre study.

Diabetic Medicine, 5, 154–159.

Waldman, R. J. (1992). Income distribution and infant mortality.

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 1283–1302.

Wen, M., Browning, C. R., & Cagney, K. A. (2003). Poverty,

affluence, and income inequality: Neighborhood economic

structure and its implications for health. Social Science &

Medicine, 57, 843–860.

Whitford, D. L., Griffin, S. J., & Prevost, A. T. (2003). Influences

on the variation in prevalence of Type 2 diabetes between

general practices: Practice, patient or socioeconomic factors?

British Journal of General Practice, 53, 9–14.

Wild, S., Roglic, G., Green, A., Sicree, R., & King, H. (2004).

Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000

and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care, 27(5), 1047–1053.

Wilkinson, R. G. (1992). Income distribution and life expectancy.

British Medical Journal, 304, 165–168.

Wilkinson, R. G. (1994). The epidemiological transition: From

material scarcity to social disadvantage? Daedalus, 123(4),

61–78.

Wilkinson, R. G. (1996). Unhealthy societies: The affliction of

inequality. London: Routledge.

Wilkinson, R. G. (1997). Income, inequality and social cohesion.

American Journal of Public Health, 87, 104–106.

Wilkinson, R. G. (1999). Putting the picture together: Prosperity,

redistribution health and welfare. In M. Marmot, & R. G.

Wilkinson (Eds.), Social determinants of health (pp. 256–274).

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilkinson, R. G. (2000a). Deeper than ‘‘neo-liberalism’’: A reply

to David Coburn. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 997–1000.

Wilkinson, R. G. (2000b). Inequality and the social environment:

A reply to Lynch et al. Journal of Epidemiology and

Community Health, 54, 411–413.

Wilkinson, R. G. (2006). The impact of inequality: Empirical

evidence. Renewal, 14.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2006). Income inequality and

population health: A review and explanation of the evidence.

Social Science & Medicine, 62, 1768–1784.

Woods, J. V. (1989). Theory and research concerning social

comparisons of personal attributes. Psychological Bulletin,

106, 231–248.