Literature Review- Major Depressive Disorder

-

Upload

cooper-feild -

Category

Documents

-

view

39 -

download

0

Transcript of Literature Review- Major Depressive Disorder

RUNNING HEAD: PERSPECTIVES IN MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER (MDD) 1

Current research and perspectives in major depressive disorder: A literature review

Cooper John Feild

Southern Utah University

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 2

Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is increasing in prevalence throughout the United

States. This article examines recent research into its epidemiology, which is promising but thus

far inconclusive. The same can be said of the three individual categories of its etiology: its

anatomical, physiological, and genetic etiology are currently being investigated intensely.

Research that examines MDD recovery, factors in suicide, and behavioral manifestations are also

considered here. Finally, recent perspectives and research into depression treatment are

examined. Although the origins of the disorder are complex, effective treatments have been

established. Recent knowledge into depression research can help providers gain insight into their

patient’s unique needs.

Current research and perspectives in major depressive disorder

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a pervasive disorder that is growing more common in the

United States. Although it can occur jointly with other diseases and mental disorders, it is unique

in its symptoms, epidemiology, etiology, and treatment. A common disorder, there is convincing

evidence that such historical figures as Abraham Lincoln, Vincent Van Gogh, Isaac Newton,

Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Woolf, and Patty Duke suffered from depression or related

conditions (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2015). While medical knowledge and societal

awareness of MDD are both increasing, there is still much development needed in both areas.

Recently, progress has been made in understanding the psychosocial and physiological origins of

depression, including its genetic implications, effects on brain anatomy, effects on messenger

pathways, and how it affects mood and personality. Most researchers agree that MDD etiology

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 3

and treatment is so multi-faceted and variable that a single diagnostic test and treatment for the

condition will never be found. However, with increased exposure and research, there will be

much more hope for those increasing numbers of people diagnosed with depression in the future.

Further research will also help providers know how to care for the diverse range of people with

MDD even though their symptoms can vary widely from person to person.

Symptoms

A review article published in the New England Journal of Medicine succinctly stated that

depression is related to normal feelings such as sadness and bereavement, but is distinguished as

abnormal psychology because these feelings do not remit when the cause of these emotions is

removed. The emotional and physical reaction to an event is also disproportionate to its cause in

the depressed patient (Belmaker & Agam, 2008). It is important to note that in MDD symptoms

are severe enough that they interfere with normal life activities such as eating, working, sleeping,

studying, and participating in activities previously deemed fun or pleasurable. Specifically, signs

and symptoms of depression include (but are not limited to due to individual variations):

Persistent sad, anxious, or empty feelings, feelings of hopelessness or pessimism, feelings of

guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness, irritability, restlessness, fatigue, decreased energy,

difficulty concentrating, remembering details, and making decisions, insomnia, early-morning

wakefulness, excessive sleeping, overeating, appetite loss, thoughts of suicide, suicide attempts,

or somatic symptoms such as aches, pains, headaches, cramps, etc. that do not ease with normal

treatment (National Institute of Mental Health, 2015). Self-reported symptoms and self-reported

personality descriptives are used in both the diagnosis of MDD and in research related to MDD.

Variables such as psychomotor retardation, dysphoria, anhedonia, insomnia, appetite loss, and

irritability were used in a recent study to identify neural indicators of error processing in

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 4

depressed patients (Weinberg et al., 2015). Questionnaires, surveys, and inventories used to

screen for depression are usually based on self-reported feelings such as hopelessness, sadness,

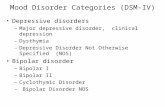

lack of motivation, and other such feelings. The DSM-V criteria for MDD is found in Appendix

A, and specifies that five or more of these symptoms must be present during the same 2-week

period, represent a change from previous functioning, and include either a depressed mood or

loss of interest or pleasure. The symptoms also must cause social or occupational distress or

impairment and not be the direct result of a substance or other medical condition (American

Psychiatric Association, 2013. See appendix A)

Kepfer et al. pointed out that “[MDD] not only produces decrements in health that are

equivalent to those of other chronic diseases (eg, angina, arthritis, asthma, and diabetes), but also

worsens mean health scores substantially more when comorbid with these diseases, than when

the diseases occur alone” (2012, p. 1). The social effects of depression are also troubling. A large

study of over 1,000 depressed patients found that 79% reported experiencing discrimination in at

least one life domain. 37% had stopped themselves from initiating a close personal relationship,

25% stopped themselves from applying for work, and 20% from applying for education or

training (Lasalvia, 2012).

Epidemiology

With such detrimental effects to the health and happiness of patients, the epidemiology of

depression has been an important area of focus for researchers. About 6.7% of U.S. adults

experience MDD. Women are 70% more likely than men to experience MDD during their

lifetime, and non-Hispanic blacks are 40% less likely than non-Hispanic whites to experience

depression. The average age of onset in MDD is thirty-two years old, but 3.3% of 13-18 year

olds have experienced MDD (NIH, 2015). The lifetime risk of MDD is about 17% (Anxiety and

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 5

Depression Association of America, 2015). It has been shown that social isolation increases risk

for depression, but that excessive rumination with others about depression can also have negative

effects (American Psychological Association, 2015). Anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress

disorders, obsessive-compulsive, panic disorder, social phobia, heart disease, obesity, stroke,

cancer, HIV/AIDS, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, and other chronic diseases often accompany

depression (NIH, 2015), although there is question if these conditions lead to depression or are

results of depression. As aging events such as menopause, poor health, or loss of cognitive

ability occur, depression also increases. There is evidence that there is aggregation of major

depression in families (with genetic influences the major factor), with heritability estimated to be

31-42%. Sullivan et al. stated that there is little supporting evidence that environmental

influences common to members of a family are important in causation of MDD, but they

emphasized that environmental effects are highly individual and should never be discounted

(Sullivan et al., 2000).

Etiology

One reason that such effort has been put into analyzing the epidemiology of MDD is that

the etiology of depression is so complex. Researchers hope that a strong understanding of the

epidemiology of depression can help make sense of the numerous anatomical, physiological,

genetic, psychological, and social data about MDD. This would therefore help us come to a solid

conclusion about the etiology of MDD. This has not shown to be the case. The etiology of

depression is extremely complex, and recent research has only elucidated this point. The typical

medical model pattern of finding the cause of a disease and developing a treatment based off that

cause is inadequate in dealing with MDD. However, there is still value in recent research into

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 6

MDD etiology, and we do have a better understanding of depression now than even a decade

ago.

Anatomical etiology

One study showed that patients with MDD had significant hippocampal volume reduction

without smaller volumes of other brain regions or whole brain volume, even after controlling for

brain size, age, alcohol exposure, and education (Bremner, 2000). The same study showed that

the amygdala was larger on average, but not significantly. However, in 2010 Lee et al. stated that

“Functional changes in brain regions such as the pre-frontal/cingulate cortex, hippocampus,

striatum, amygdala, and thalamus are correlated with depression” (p. 6). Theirs was an extensive

literature review on the subject, and they further cited radiological data that showed reduced

volumes of orbitofrontal and subgenual anterior cingulate cortices, reductions in hippocampal

volume, and glial reduction in the anterior cingulate gyrus. Abnormal sizing of the nucleus

accumbens, amygdala, and hypothalamus seem to be directly related to many of the emotional

symptoms mentioned earlier. Kupfer et al. state simply that neural systems that support emotion

processing, reward seeking, and regulation of emotion are all dysfunctional in MDD (2012).

However, Bemner et al. were careful to point out that they were unsure if depression was causing

development of a smaller hippocampus or if people with a naturally smaller hippocampi were

more likely to have depression. This same chicken-and-egg question can be asked of the entire

subject of anatomical etiology of MDD: Is depression (whatever its cause) causing lesions and

abnormalities to occur in depressed patients’ brains, or are people that already have these lesions

and abnormalities the ones being diagnosed and treated for depression? Only further research,

and specific investigation into each brain area, will reveal the answers.

Physiological etiology

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 7

In this review, the overwhelming majority of articles dealing with causes of depression focused

on physiological etiology. This includes analyses of hormonal pathways, messenger systems,

signal molecules and receptors, etc. The monoamine-deficiency hypothesis is a long-standing

possible cause of depression. After it was discovered that drugs that antagonized monoamine

oxidase (which catabolizes norepinephrine and serotonin) were successful antidepressants, it was

postulated that a lack of availability of these two hormones was at the root of depression. Recent

research suggests that while epinephrine and serotonin have important roles in the mechanisms

of some pharmacological treatments for depression, additional neurochemical factors are

necessary to actually cause depression. Recent studies have opened up the possibility that

previous explanations that focus extensively on monoamine oxidase are too simplistic, and that

the problem may lie further downstream in the second-messenger pathways and G-protein

messenger systems that are modulated by epinephrine and serotonin (Belmaker and Agam,

2008). However, Belmaker and Agam pointed out that the monoamine theory has demonstrated

incredible predictive power, stating that “Almost every compound that has been synthesized for

the purpose on inhibiting norepinephrine or serotonin reuptake has proven to be a clinically

effective antidepressant” (2008, p 57). Despite this they postulate that the monoamine-deficiency

hypothesis might only explain about a third of MDD cases.

Another area of current research is stress-induced depression. It has been shown that

chronic stress is an important component in depression, but that it might not be a sufficiently

strong factor to actually cause depression. It has been found in animal studies that antagonism of

corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors, glucocorticoid receptors, and vasopressin

receptors might have antidepressant effects (Lee et al., 2010). Other studies have explained why

by showing that patients with depression may have elevated plasma cortisol levels, elevated

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 8

CRH levels in the cerebrospinal fluid, and that the normal cortisol-suppression response is absent

in about half of severely depressed patients (Belmaker & Agam, 2008). Thus, even if its role as a

causative factor is not currently understood, stress and cortisone are viable targets for treatment

of depressed patients.

Both stress and genetic polymorphisms are implicated in the reduction of brain-derived

neurotrophic factors (BDNF), a lack of which are also implicated in depression causation. The

first evidence of this pathway came when it was realized that long-term antidepressant use

helped restore BDNF in patients (Lee et al., 2010). However, the causative role of a lack of

BDNF is unclear, and might even be gender-specific. One study showed that depression-related

behaviors stemming from elimination of BDNF in mice were evident, but only in female mice

(Lee et al., 2010). Some researchers optimistically peg BDNF as the link between stress,

neurogenesis, and hippocampal atrophy in depressed patients (Belmaker & Agam, 2008). The

pathways implicated in this statement are still under investigation, and it is unsure if a genetic

lack of BDNF or other factors eventually leading to reduced BDNF are more to blame in

causation.

Two final physiological possibilities were brought up in the literature: That of histone

involvement in depression and circadian rhythm involvement. Histones are the focus of some

depression research because it has been shown that both electroconvulsive shock therapy (ECT)

and anti-depression medications seem to have an inhibitory effect on histone deacetylaces, while

ECT has been shown to increase acetylated histone H3 at BDNF promoters (Lee et al., 2010).

With regard to circadian rhythm, it has been shown that disruptions to this can bring on seasonal

depression and that patients suffering from MDD may have internally disrupted circadian

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 9

rhythms. Increased understanding into the factors that control circadian rhythms may yield novel

ideas regarding causation and treatment of depression (Lee et al., 2010).

Genetic etiology

The final possible etiology mode discussed here will be genetic etiology, although a few broad

statements might serve to best explain the role of genetics in depression. First, dozens of well-

designed studies including thousands of patients are yet to reveal a single causatory genetic

factor in depression. Second, different types of depression (and different resultant symptoms)

have been shown to involve different regions of the genome. Third, genetic markers can

favorably be used to predict effectiveness of anti-depressants (Kupfer et al., 2012). The MDD

Working Group of the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium published A mega-analysis of genome-

wide association studies for MDD. A few important points from this 2013 paper that included

over 100,000 subjects are:

“The primary finding of this paper is that no locus reached genome-wide

significance in the combined discovery and replication analysis of MDD” (p 7).

“These results for MDD are in sharp contrast to the now substantial experience

with GWAS for other complex human traits…the vast majority of GWAS with

sample sizes > 18 000 found at least one genome-wide significant finding

(178/189 studies, 94.2%), and yet we found no such associations for MDD” (p 8).

“There has been considerable speculation that gene-environment interactions are

particularly salient for MDD. It is possible that MDD can only be understood if

genetic and environmental risk factors are modeled simultaneously” (p 10).

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 10

Genetics will continue to be an important area of study with MDD, but researchers investigating

genetic causation appears to face nearly the same problem as those studying MDD-related

physiology, anatomy, or psychology. That is, the disorder is so complex it is unlikely that a

single genetic, physiological, or anatomical finding will explain the origin of MDD. Belmaker

and Agam believe that this idea is actually important for those suffering from MDD, saying:

“Avoidance of premature closure on any one scientific theory of the mechanism of depression

will best serve the search for new, more effective treatments” (2008 p, 65). Because of the

individual nature of MDD etiology and treatment, keeping more possibilities on the table is very

important for patients.

For the Patient

While understanding the causes of depression is important, it is equally important to keep

in mind how MDD affects the life experience of patients. The remainder of this paper will deal

with the status of current treatment outlooks and methods. In these areas, the literature shows

reasons for equal parts optimism and caution. Although depression will be a lifelong illness in

many patients, research has shown that cognitive-based behavioral therapy (CBT) during

depressive episodes is effective in reducing relapse and recurrence. Continuation of

psychological treatment after episodes can also significantly extend survival time following

recovery (Teasdale et al., 2000). Providers must be diligent in determining the extent of a

patient’s recovery and remission. Incomplete recovery from a first lifetime major depressive

episode has been shown to negatively influence long-term outcomes. Judd et al. found that

patients in recovery that had residual subthreshold depressive symptoms went on to have a

significantly more severe and chronic course of illness. This included more depressive episodes,

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 11

more chronic major depressive episodes, shorter well intervals, and much fewer weeks free of

depressive symptoms (2000).

The provider must also be aware of how he or she is being received by the patient. An

understanding that the provider is open, willing to help, and accepting of the patient’s fears,

worries, guilt, and inadequacy can itself be therapeutic to the patient. Providers that offer a basic

biological explanation of MDD can help take away the inexplicable and threatening character of

depression in the patient’s mind (Bschor & Adli, 2008). Fostering this provider-patient

relationship will also allow the provider to understand how MDD is manifest in that patient’s

cognition, personality, and behavior. These manifestations are highly variable in depression and

will determine the provider’s approach to psychotherapy and, to some extent, pharmacotherapy.

Some patients describe being too friendly and having a lack of assertiveness- this is evidence of

depression causing an elevated need for relatedness. Other patients might express problems with

being self-directed, cold, and avoiding social interactions- this is evidence of depression causing

increased self-criticism. Depression in Americans has been shown to be manifest by greater

hostility and dominance, while Germans described being more frequently exploited by others

(Dinger et al., 2015). A provider must be aware of these individual and cultural differences.

Special care must be taken with pessimistic or self-critical patients. Research has shown

that a tendency for pessimism increases the risk for future suicidal acts (Oquendo et al., 2014).

Self-criticism is highly correlated with depression severity, and is associated with an increased

risk for serious, lethal suicide attempts (Dinger et al., 2015). One study found that the strongest

predictors of suicidal acts were past suicidal behavior, a high subjective rating of depression

severity, and cigarette smoking. Impulsive and aggressive traits were also shown to be predictors

of suicidal acts (Oquendo et al., 2014). The authors of that study interpret their results as

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 12

showing that suicidal behavior is not merely a response to a stressor, but is a manifestation of the

individual’s diathesis. Bschor and Adli suggest that specific steps should be taken for suicidal

patients. First, an immediate psychotherapeutic crisis intervention should take place with a

trusted provider. Second, the patient should also begin working with a specialized

psychotherapist if being treated in primary care. Third, short-term follow up at close intervals

should occur in conjunction with “Clear, unambiguous agreement on the time and place of the

next session”. Fourth, a concrete offer of 24-hour help availability should be extended. Fifth, an

anti-harm and anti-suicide pact should be established. Sixth, inpatient referral or involuntary

commitment might be necessary. Seventh, benzodiazepine can be used in acute suicidality (2008,

p. 784).

Individual modes of psychotherapy were not assessed in this review. However, most

psychotherapeutic approaches usually involve the following aspects: Confidence in the care

provider (as mentioned above), resource activation (or identification and then reinforcement of a

patient’s abilities), problem actualization (or addressing particular areas of conflict), problem

coping (or support through emotional, cognitive, or active solution strategies), and motivational

clarification (or recognizing and addressing problematic modes of perception, behavior, and

dysfunctional cognitions). When properly administered, various forms of psychotherapy have

been shown to be effective in treating MDD (Bschor & Aldi, 2008).

If pharmacotherapy will be used, the choice of antidepressant medication will depend on

the provider’s assessment of the patient’s symptoms, the side-effect profile of the drug, and, if

the information is available, the patient’s genetic predisposition to respond to specific agents.

Since all medications are comparatively effective in severe depression, consideration of side-

effects becomes the largest determinate of the prescription (Bschor & Adli, 2008). As with the

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 13

prescription of any other medication, drug-drug interactions, diet-drug interactions, and drug

effects on other medical conditions must be considered. A detailed assessment of the different

antidepressant medications will not be undertaken here.

Finally, other modes of therapy might be considered. As alluded to earlier, ECT has been

shown to be effective, and it is experiencing a resurgence in popularity. It is especially indicated

in treatment-resistant depression. Beneficial effects usually become apparent after one to three

weeks with three ETC sessions per week. Recurrences of depressive episodes during the early

part of the therapy is the major therapeutic drawback (Bschor & Adli, 2008). Novel treatments

still under development and research for use with MDD are deep brain stimulation and

transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Both methods have been shown to be more effective

than placebo and possibly comparable to the effectiveness of antidepressant medication in early

testing, but side effects are poorly understood and warrant caution (Kupfer et al., 2012).

Conclusion

Despite being perhaps the most well-known of all mental illness, there is a common

strain that runs through MDD symptoms, epidemiology, etiology, and effective treatments: they

are diverse and highly individual. Thus, the proper care of the patient is highly dependent on two

things. First, there must be responsibility on the patient’s part. He or she has the final say in what

treatments are effective and leading to a better life and which are not. Second, the provider must

approach each patient as an individual and carefully assess their unique symptoms. If both of

these things happen, MDD is a treatable disorder, despite our lack of exact understanding of its

mechanisms. And if that very lack of understanding leaves providers and patients with a sense of

discovery and longing for answers, perhaps it is better for patient care in the long run that we

don’t understand its mechanisms and never do.

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 14

Works Cited

American Psychological Association. Depression. (2015). Retrieved April 23, 2015, from

http://apa.org/topics/depress/index.as

Anxiety and Depression Association of America. (2015). Depression. Retrieved April 23, 2015, from http://www.adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/depression

Belmaker, R. H., & Agam, G. (2008). Major depressive disorder. New England Journal of

Medicine, 358(1), 55-68.

Bremner, J. D., Narayan, M., Anderson, E. R., Staib, L. H., Miller, H. L., & Charney, D. S. (2000).

Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry, 157 (1), 1433-1441.

Bschor, T., & Adli, M. (2008). Treatment of depressive disorders. Dtsch Arztebl Int, 105(45), 782-792.

Dinger, U., Barrett, M. S., Zimmermann, J., Schauenburg, H., Wright, A. G., Renner, F., ... & Barber, J.

P. (2015). Interpersonal Problems, Dependency, and Self‐Criticism in Major Depressive

Disorder. Journal of clinical psychology, 71(1), 93-104.

Judd, L. L., Paulus, M. J., Schettler, P. J., Akiskal, H. S., Endicott, J., Leon, A. C., ... & Keller, M. B.

(2000). Does incomplete recovery from first lifetime major depressive episode herald a chronic

course of illness? Am J Psychiatry, 157 (9), 1501-1504.

Kupfer, D. J., Frank, E., & Phillips, M. L. (2012). Major depressive disorder: new clinical,

neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. The Lancet, 379(9820), 1045-1055.

Lasalvia, A., Zoppei, S., Van Bortel, T., Bonetto, C., Cristofalo, D., Wahlbeck, K., ... & ASPEN/INDIGO

Study Group. (2013). Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination reported by

people with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional survey. The lancet, 381(9860), 55-62.

PERSPECTIVES IN MDD 15

Lee, S., Jeong, J., Kwak, Y., & Park, S. K. (2010). Depression research: where are we now? Molecular

brain, 3(1), 8.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (2015). People with mental illness enrich our lives. Retrieved April

21, 2015, from http://www2.nami.org/Template.cfm?Section= Helpline1&template

=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=4858

National Institute of Mental Illness (2015). Depression. Retrieved April 23, 2015, from

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml

Oquendo, M. A., Galfalvy, H., Russo, S., Ellis, S. P., Grunebaum, M. F., Burke, A., & Mann, J. J. (2014).

Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in

patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry, 161 (8): 1433-

1441.

Ripke, S., Wray, N. R., Lewis, C. M., Hamilton, S. P., Weissman, M. M., Breen, G., ... & Degenhardt, F.

(2013). A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive

disorder. Molecular psychiatry, 18(4), 497-511.

Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review

and meta-analysis. Genetic Epidemiology, 157(10).

Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., Ridgeway, V. A., Soulsby, J. M., & Lau, M. A. (2000).

Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive

therapy. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 68(4), 615.

Weinberg, A., Kotov, R., & Proudfit, G. H. (2015). Neural Indicators of Error Processing in Generalized

Anxiety Disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and Major Depressive Disorder.