Lipsey Im Part3

Transcript of Lipsey Im Part3

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

1/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

Part Three: Markets for Inputs

Part Three goes behind the scenes of the goods markets considered in Part Two to look atthe markets for the traditional inputs to production: capital and labour. There is somecoverage of technology too, but natural resources and land are scarcely mentioned. We start

with the general theory of input markets, and then go on to consider labour and capital inturn.

Chapter 10 considers input markets in general, and assumes that all markets (both input andoutput) are competitive. It opens with some introductory remarks on the term distribution ofincome and some information on current income distribution in the UK. The links betweeninput and output decisions are then spelled out. After these preliminaries the analysis followsthe pattern set for goods markets in Chapter 3 by tackling the demand side of the marketfirst, with a derivation of the basic result that a profit-maximizing firm will set the marginalrevenue product of an input equal to its marginal cost. The industrys demand curve for aninput is then compared with that of the firm, and the four Marshallian determinants of theelasticity of demand for inputs are considered. The supply side is brought in next, initially

treating each main input at a fairly aggregate level. The two sides of the market are thenbrought together, with the text noting that this poses no new problem (page 216) as theanalysis is parallel to that for the goods market. There are however issues of input-pricedifferentials and pay equity to be considered, along with the concept of economic rent.

The remaining two chapters form a pair, analysing respectively the markets for labour andfor capital. The longest section in Chapter 11 is on wage differentials and their possiblecauses. As with the rest of the chapter the discussion has a strongly applied flavour and agood number of practical examples; topics such as sex discrimination and minimum wageslaws show well how economic principles can be put to use. The final section of the chapterconsiders heterogeneity in the labour force. It introduces concepts such as signalling,monitoring costs and internal labour markets that reflect recent areas of research ineconomics. Two of the three case studies at the end of the chapter discuss the high pay ofsuperstars and chief executives that generates so many current newspaper headlines.

Chapter 12 moves on to the other main input to production, capital. We start off with ideas ofdepreciation, present value and future returns as a preparation for finding the equilibriumpositions of first the firm and then the whole economy. The second part of the chapterexplores some of the issues that arise in an NPV investment decision. It also introduces theidea of an option and applies it to the decision to close down a (temporarily?) loss-makingfirm. The final section analyzes the current Information and Communication Technology (ICT)revolution and the New Economy it is generating. It introduces the idea of a General PurposeTechnology (GPT): an innovation, such as electricity or the computer, which has sufficient

transforming effects to create a New Economy. The section lists recent changes, grouped intofour types of technologyprocess, product, organizational, and social and politicaland endsby noting the consequences of the ever-declining costs faced by many ICT firms in terms ofbarriers to entry for new firms.

This part of the book concludes the formal treatment of microeconomic theory for asuccessful market economy. The possibility of market failure and a role for the governmentare still to come in Part Four, but the bulk of basic microeconomics has now been covered.

Notes for users of the previous edition

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

2/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

This Part is very similar to its predecessor in the eleventh edition. As in Parts One and Twothere are some new boxes, generally early in the chapters so remaining boxes getrenumbered. Illustrative examples and numbers have all been updated, but the bulk of themain text is little changed. The biggest exception is the last section of Chapter 12, where a fairamount of re-ordering has taken place, but even here the net additions and deletions remainfairly small. With one exception (Question 5 in Chapter 12) the end-of-chapter questions areunchanged too.

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

3/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

Chapter 10: Demand and Supply of Inputs

This chapter is the first of the three in this part of the book, and focuses on input markets ingeneral. In this chapter all markets (both input and output) are competitive. There are fivemain sections plus some case studies.

The first section, an Overview, starts with a brief explanation of the terms distribution

theory and thefunctional distribution of income. Box 10.1 looks at a particular aspect ofincome distribution: that between rich and poor in the UK. The text then moves on to the linkbetween firms output decisions (studied earlier in Chapters 6 and 7) and their demands forinputs, which is the basis of the neoclassical theory of distribution. This is summarizedbriefly, and the parallels between goods markets and input markets are stressed. Thesection ends by spelling out the assumptions of other prices constant and competitivemarkets which will be made for the rest of the chapter.

The second section moves on to the demand for inputs in more detail, introducing the idea of

a derived demand and noting that the demand curve for any input is downward sloping. The

reasons for this differ in the long run (when all inputs are variable) and the short run (whenthey are not), and are accordingly analysed separately. Substitution and income effects areused here, as introduced in Chapter 6. The basic result that a profit-maximizing firm will setthe marginal revenue product of an input equal to its marginal cost is derived and explainedat some length. This generates the firms demand curve for the input, which in turn leads onto the industry demand. The section ends with a discussion of the elasticity of input demandand the influences on it. There are three boxes in the text: one on produced inputs in thesupply chain, a relatively mathematical one on the demand for inputs where more than oneof them is variable, and one on the principles of derived demand.

The next section considers the other (supply) side of input markets. It starts at the highestlevel of aggregation with the total supply of resources, discussing capital, land and labour

separately. Box 10.5 derives the backward-bending labour supply curve usingindifference curves. The section then moves on to the supply of inputs for a particular use,stressing the role of input mobility (again treating each of the three main inputs separately).It ends with a short paragraph on the supply of inputs to individual firmsthat is, the lowestlevel of aggregation.

The fourth section looks at The operation of input markets. Reward differentials, bothdisequilibrium and equilibrium, are considered, along with the factors that cause them to

disappear or persist respectively. This leads logically on to the question of pay equity, wherethe text notes the need to take the non-monetary aspects of different jobs into account, andother variables affecting the supply and demand for labour.

The fifth section is a discussion of the concept ofeconomic rent, including Box 10.6 tracingthe term back to Ricardo. The proportion of an inputs payment that is due to rent is showndiagrammatically to depend on the shape of the supply curve and the mobility of the input(which itself depends on whether we are considering a single firm, an industry or anoccupation). Wayne Rooney makes an appearance here as an example of a high earner.

The chapter is rounded off with two case studies. The first traces the history of fuelsubstitution in UK electricity generation from the 1950s to 2008, showing how it varied inresponse to both input prices and politica l demands (during the 1984 miners strike). Thesecond case study looks at employment in UK manufacturing over a similar period, stressingthe point that the UKs relative decline in world terms masks a growth in absolute output and

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

4/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

productivity. A major part of the story (page 221) is explained in terms of technologicalchange, with globalization and company restructuring important too.

Notes for users of the previous edition

This chapter corresponds closely to Chapter 10 in the eleventh edition. There is somerelatively minor rewriting and updating (the latter especially in the case studies). Box 10.1 onactual UK income inequality is new (replacing the more abstract one on distribution theory inthe previous book) and Box 10.2 on produced inputs has been considerably revised andextended. Remaining boxes and the end-of-chapter questions are unchanged.

Connoisseurs of previous editions will note another new name in the line of footballers whoillustrate the phenomenon of economic rent (page 220). Wayne Rooney fills the slotoccupied by David Beckham, Michael Owen and Ryan Giggs in the eleventh, tenth and nintheditions respectively. Such is the comparative brevity of a top players career!

Answers to end-of-chapter questions

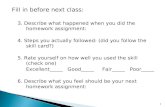

1 The first four columns in the following table provide the necessary information:

Workers Mowers MPP MRP MR MRP W

7 99 202 4408 110 11 1100 180 3080 4609 120 10 1000 160 1600 480

10 129 9 900 142 1278 50011 137 8 800 126 1008 52012 144 7 700 112 784 540

13 150 6 600 100 600 56014 155 5 500 90 450 58015 159 4 400 82 328 60016 162 3 300 76 228 620

(a) See table.

(b) See table.

(c) This question is an application of Equation (10.2) or (10.2) on page 208. The firm willhire 14 workers, as the 14th workers MRP is just equal to the cost of hiring them.Strictly speaking the firm will be indifferent as to whether it takes on the 14th worker

or not, but we generally assume that it will do so in these circumstances. (If there areany non-labour variable costssuch as steelto be considered then this wouldmean the firm would stop at Worker 13, if not earlier.)

2 The complication here is that the price of lawnmowers is no longer fixed. Note that thiscase goes beyond what is explained in the text.

The fifth column in the table in Question 1 shows the MRcalculated from the equation inthe question. We multiply this by the MPPof labour to get a new MRP (labelled MRP inthe sixth column of the table). With the cost of a worker still at 500, the firm will employ13 workers.

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

5/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

3 The final column in the table shows the wage W produced by the equation in thequestion. Comparing this with MRP the firm will again employ 13 workers.

4 This is a revision question, based on the material in the text on pages 205212.

5 The elasticity of demand for an input in one specific use is determined by Marshalls fourfactors set out on pages 211212. The elasticity in general use is likely to depend on hownarrowly the input is defined (all labour versus skilled labour versus computerprogrammers, for example), which will affect its possibilities of substitution. Otherwisesome sort of average of the specific uses will be relevant; for example, if land is generallyan unimportant input in production then its elasticity of demand will be low.

6 Land in central London is scarce and there are a lot of competing uses for it. If hotelscould not charge high prices for their rooms they would not be able to afford the high

rents and would go out of business. If the land is not occupied by a hotel there are plentyof other businesses willing to pay for it. It is the high demand in general that matters. Ifthe high demand was only for hotels (and not for shops and restaurants and offices) thenthe demand for land in central London would not be that high.

The rule is that the scarce resource attracts the economic rent in any situation of highdemand for the final product. Central London can always recruit labour and capital fromoutside, but it cannot import land.

See Box 10.6 for further discussion of the term economic rent.

7 The highest proportion of rent would go to either pop stars or professional footballers(both discussed in the text on page 220); it is not clear which. One difference between thetwo is that there is no equivalent of the football club for pop starstheir brand is theirown, whereas for footballers their club is also important. Wayne Rooney could move(again) to another club or leave football altogether; the pop star does not really have thefirst of these options.

After that one possible order would be: doctors, university teachers, computerconsultants, taxi drivers, shop assistants. However other rankings are clearly possible,and this question would make a good basis for a class discussion.

8 In all three cases the rising demand for the final product will translate to increaseddemand for all inputs used in their production. In the short run this may affect price morethan quantity, depending on how quickly input supply can be increased; for example,organic vegetable production can be increased from existing organic producers, but newones cannot be in place for some years (due to the need for a certain time gap since non-organic production took place on that land). Cheap flights may either displace other flightsor expand the overall flight market; in the former case aircraft and other inputs can beredeployed, but in the latter new resources will be needed. This may take time (to trainnew pilots and build new aircraft), so in the short run we would expect to see a rise inpilots wages and aircraft leasing charges.

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

6/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

Chapter 11: The Labour Market

As its name suggests this chapter moves on from the general discussion of input markets inChapter 10 to concentrate on the labour market. It contains two main sections plus some casestudies.

The first section is a fairly long and detailed consideration of wage differentials, illustrated inBox 11.1 with a topical FTarticle on the pay of senior executives, which were touched uponbriefly in Chapter 10. However the differentials covered here are ones which persist inequilibrium, such as those associated with variations in age or education. A number of causesof these differentials are identified and analyzed here, including the following:

The existence of non-competing groups (in segmented markets).

Variations in human capital, acquired through either formal education or on-the-job training.The former is analyzed in terms of its costs or benefits to the individual and the latter byexamining the impact on rates of pay after different periods of employment.

Sex and race, with a specific consideration of why women are paid less than men in Box11.3. A fairly standard model of labour market discrimination, using supply and demand

curves for an elite market and an ordinary market, is used to analyze some extreme formsof discrimination, such as those in apartheid South Africa.

Labour market structures, in particular in the degree of competition on both sides of themarket. The argument is set out separately for a non-union and a unionized labour force.The last case is the one where a monopsonist faces a monopolist union, at which point theargument moves beyond simple demand and supply analysis into the realm of bargainingtheory (not covered here).

Product market structures, that is whether final goods markets are competitive ormonopolistic.

Minimum wage laws. The text refers here to the UK legislation which came into force in April1999, as an example of a comprehensive minimum wage (that is, one that does not vary

across occupations).

Teaching Note The caption to Figure 11.2 refers to the concept of discounting whenanalyzing the costs and benefits of entering further education; this concept has not beendiscussed previously (it is introduced early in the next chapter).

The second section of the chapter introduces the idea of heterogeneity in the labour force. Asnoted in the introduction to the chapter, more and more employees are hired for their brainrather than their brawn nowadays (pages 224225), and this section analyzes some of themany institutions and practices (page 225) which have developed to minimize the associated

costs of monitoring and signalling. The ideas of principal-agent theory, moral hazard and

adverse selectionare brought in at this point. Relational contracts, efficiency wages, andsignallingare introduced as responses to the informational problems faced in real life. Finallythere is a subsection on internal labour markets, including the reasons firms use them and the

analogy with a tournament. The high pay of senior executives appears here as part of theincentive structure facing all employees.

The chapter ends with three case studies and a brief conclusion. The first case study putsforward some explanations of the massive earnings of superstars; the second expands on theearlier discussion of senior executives pay; and the third reports briefly on the impact of theUKs minimum wage since 1999.

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

7/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

Notes for users of the previous edition

This chapter follows Chapter 11 in the eleventh edition closely, with only minor rewriting. Theintroduction has been somewhat revised, but much of the main text is hardly altered apart fromupdating things like the level of minimum wages in the UK. Box 11.1 on the pay of seniorexecutives is new; the old Box 11.1 becomes new Box 11.2; and the old Box 11.2 on mensand womens pay gets some updating and a new graph en route to becoming the new Box11.3. All three case studies have been updated and revisions here are more extensive, with thethird study (The impact of minimum wages) being much reduced. There are a couple ofwording changes in the end-of-chapter questions but nothing that affects the answers.

Answers to end-of-chapter questions

1 We assume here that all workers are paid the same wage (the discriminating case follows inQuestion 2). The table below is based on the one used in Chapter 10:

Workers Mowers MRP W Wage Bill WB

7 99 440 30808 110 3080 460 3680 6009 120 1600 480 4320 640

10 129 1278 500 5000 68011 137 1008 520 5720 72012 144 784 540 6480 76013 150 600 560 7280 80014 155 450 580 8120 84015 159 328 600 9000 88016 162 228 620 9920 920

The wage bill is simply W multiplied by the number of workers, and WB shows thechanges in it as employment is expanded. Note the steady increase in this last column,reflecting the acceleration in the wage bill as more workers are taken on. W and WBrepresent the curves labelled Sand MC respectively in Figure 11.4.

Comparing WB with MRPshows thatthe monopsonist will employ 11 workers.

2 If the monopsonist can discriminate then employment will be the same as it was in thecompetitive case in Chapter 10that is, 13 workers. See Figure 11.4 and the discussion onpage 233.

3 Then we would be back to the competitive solution of Chapter 10, Question 2, with 13workers employed.

4 This is a very general question, and most of the material in the section on Wagedifferentials will be relevant, as will the subsection in Chapter 10 on Equilibriumdifferentials(pages 217218). Reasons will include both demand and supply factors, andnon-monetary aspects of remuneration should not be overlooked.

Teaching Note This would be an interesting question for a class discussion before the

material in this chapter has been taught

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

8/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

5 As the question implies, most labour is not homogeneous, as discussed in the second mainsection (pages 236240). Unskilled labour may be fairly homogeneous, but even then someworkers will be better or more experienced than others. As you go up the skills and trainingladder the degree of heterogeneity increases rapidly. This gives rise to the sort of problemsof incentives and monitoring costs discussed in the text, and indeed the risks of adverseselection and moral hazard introduced on page 236.

6 All three aspects are specifically covered in the text (page 238).

7 The principal-agent problem is discussed on page 237, and some solutions follow in thetext: efficiency wages and promotion opportunities, for example, will both help. Anothersolution is share options (touched on in the second case study), which help to align themanagers objectives with those of the shareholders. Paying by commission rather than a

fixed salary can have the same effect further down the firm. It may also help to delegatepower and responsibility to local managers, who will have a better idea of how hardemployees in their own area are really working. Franchising is one way to achieve this inappropriate circumstances. Finally team-working or rewards for group performance of somesort may also help, as they give employees incentives to monitor other employees effortsand prevent slacking.

Good students will no doubt come up with other solutions, perhaps based on places wherethey have themselves worked.

8 See the text on page 238. Students should be able to come up with other signals apart from

the university degree used there. A distinction can usefully be drawn between signals ofgeneral quality (a 2:1 degree in any subject, for example) and signals specific to a particularjob (an engineering degree or fluent Spanish or word-processing skills)

Teaching Note It is worth reinforcing the point that signalling is done by (potential)employees; employers use of your degree in deciding whether to hire you, for example, is

termed screening(this concept is not covered in the book).

9 One obvious difference is implied by the word internal. Goods markets are generally opento anyone (buyer or seller) and operate on a short term basis: a transaction is a one-offevent without any implications for the future (this is not to say that firms do not try to gainrepeat business, of course, but unless there is a contract for this it is not part of the deal inany formal sense). In an internal labour market (as discussed on pages 238240) bycontrast there are deliberate long-term strategies and decisions, with implicit or explicitagreements that rewards are being given and received over the longer term. Thetournaments analyzed on page 239 are a good example of this.

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

9/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

Chapter 12: Capital, Investment and New Technology

This chapter complements the previous one on labour by examining the other inputs toproduction (although land is not included). There are three main sections, corresponding to thethree elements in the title above, plus two case studies.

The first section, on capital, starts by clearing up some terms and definitions. The first of these

is the return on capital, where uncertainty and supernormal profit are assumed away to leaveus with a pure return and depreciation only (there is a reference here back to Chapter 6, wherethe various terms were introduced). Then the consequences of capital lasting more than oneperiod are brought in, together with the distinction between the prices of rental and purchaseand the implications of lumpiness (indivisibilities) in some capital goods. The third topic here is

the present value of a stream of future returns, including the concept of discounting firstmentioned briefly in Chapter 11. The present value is explained from the point of a view of afirm, wholly in terms of the rate of interest; there is nothing on the reasons for an individual todiscount the future. Box 12.1 looks at the growth of capital services over the last sixty years inthe UK, Box 12.2 picks out a particular type of assetbrandsfor analysis, and Box 12.3

explains the future value of a present sum (what would be called terminal value in the many -period case).

These various concepts are then brought together in the next subsection on the Equilibrium of

the firm. The firms internal rate of discount is stated as being equal to the market rate ofinterest (suitably adjusted for risk in each case) (page 250) but it should be noted that the riskadjustment is not really explained here (it is latersee below). The firms decision to purchasecapital is discussed, along with the link between the size of its capital stock and the rate ofinterest. The final subsection on Equilibrium for the whole economycarries this last argumentover to the aggregate level, first for the short run and then for the long run. Finally the effects oftechnological change in the very long run are considered briefly, with a reference forward to thefuller treatment in Chapter 26. The section concludes that the income of capital is the purereturn plus a risk premium plus any economic profit or loss. It is the pure return that allocatescapital to its most productive uses.

The second part of the chapter is entitled The investment decision, and is a discussion of

some of the issues that arise in an NPV calculation. First up is the choice of discount rate,including a return to the risk premium mentioned earlier and the need to use market-determined discount rates even if the capital being used was generated internally. The effectsof inflation are covered next, and the text emphasizes the need to work consistently in either

real ornominal figures, not some mixture of the two. Finally sunkcostsare analyzed, in twoparts: the first stresses that bygones are bygones (page 254), and costs sunk in the pastshould not influence current decisions; the second uses insights from option pricing theory

(Box 12.5 explains what options are) to argue that wait and see has a value in itself, andinvestments involving significant sunk costs should only go ahead if this value is less than theNPV of proceeding. This argument is also applied to the (irreversible) decision to close down afirm, where again the possibility that market conditions may improve in the future has a value.

The third section explores New technology, including the information and communicationtechnology (ICT) revolution and the new economy. After a short resum of some of thetechnological advances that have transformed our lives in the last hundred years it introduces

the idea of a General Purpose Technology(GPT). This is a wide-ranging innovation, such aswriting, printing, electricity or the motor vehicle, or more recently computers and flexiblemanufacturing. GPTs have major impacts on social and economic structures, typicallyproducing a step fall in the cost of providing some good or service, and leading to the creation

of a new economy. The transformations wrought by the introduction of writing and printing are

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

10/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

given as examples, and lead naturally into an exploration of the current ICT revolution and itsparticular new economy. Much of this consists of a long list of the changes that haveoccurred, grouped under the four headings of Process technologies, Product technologies,Organizational technologies and Social and political technologies. The section ends bynoting that many ICT firms face cost curves that decline continually, and this has majorimplications in terms of the barriers to entry for new firms, leading to a winner takes alloutcome.

The chapter ends with two case studies. The first looks at the value of entry restriction in taxi-licensing systems, contrasting the system in New York (where there are a fixed number ofmedallions) with that in London (free entry to those who pass the Knowledge). The secondconcerns city land prices and the height of skyscrapers, including a contrast between NewYork and London; it argues that London developed skyscrapers later than New York forgeological reasons and that, even when engineers overcame these problems, sunk costsmeant that Londons height profile took some time to adjust and mimic that of New York.

Notes for users of the previous edition

This chapter is fairly similar to its predecessor in the eleventh edition. Its structure remains thesame, but there is a bit more revision of the content than in the previous chapters in this Part,plus a couple of new boxes. The main text in the first two sections is almost the same as it wasbefore, apart from minor updating of examples. Box 12.1 on capital services growth in the UKis new, so the old Box 12.1 becomes 12.2 (and is also augmented with some recent examplesof brand values) and 12.2 becomes 12.3 (with no other changes). Box 12.4 (12.3 before) onreal and nominal interest rates gets an extra final paragraph as well as being updated. The oldBox 12.4 is renumbered to 12.5.

The early part of the third section of the chapter (New technology) looks somewhat different,

but this is more due to moving material around than changing it (although there are some newadditions too). The first two paragraphs in The ICT revolution (eleventh edition, page 262)have been brought forward and the recent innovations sub-heading has been deleted. Thereis a new paragraph on knowledge-based economies and an accompanying Box (12.6)entitled Intangible assets matter. This and earlier changes mean that the final Box 12.5 onThe winners curse is now Box 12.7; it also gets some updating.

The first case study now compares taxi licensing in New York and London, rather than Torontoand London, which has obviously led to some rewriting of the text; the other case study isunchanged. The end-of chapter questions are largely the same as before; the exception isQuestion 5, where the examples used have been revised.

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

11/14

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

12/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

5 For the first two examples here, note that the introduction to the chapter points out that non-renewable resources are discussed on the books website, but not in the book itself.

(a) This requires us to estimate the present value of the stream of income that can beobtained from exploiting optimally the companys reserves. The description of thecompany as relatively small means that it can safely be assumed to be a price -taker.We need to make some assumptions about the firms discount rate, and clearly someestimate of the future path of oil prices will also be needed. The more the oil price isexpected to increase in the future, the more it will make sense to postpone theextraction of the oil.

The simplest calculation would be to assume a steady rate of extraction (perhaps thecurrent rate) continuing until the oil is all gone, using an illustrative discount rate and thecurrent oil price. This would provide an initial valuation, which would illustrate the basicprinciples and act as a baseline to see what improvements were possiblesuch asspeeding up or slowing down the rate of extraction and making varying assumptions

about future oil prices. Sensitivity to the discount rate could also be tested.

The question is a pretty open one, so the results are all going to be a bit rough andready. It is probably more about ensuring students understand the issues thanproducing any particular answer.

(b) This is similar to part (a) except that we are now dealing with all the resources of thecommodity, so the price-taking assumption no longer holds. The broad structure of thecalculations would be the same. The value of the reserves should depend onconsumers valuation of the commodity, for which any current price would be at least astarting point. The final answer will depend on how fast the reserve is extracted, andthis could open up a discussion about how the speed of extraction could or should be

decided. Intergenerational issues come in here too; how far should we deny ourselvesthe benefits of the commodity in order to preserve some of them for our children andgrandchildren?

This question is likely to generate an even more open discussion than the previous one,bringing in more normative issues of how we should value finite resources when we aredealing with the entire stock.

(c) The PV of a perpetual stream of income is just the annual payment divided by thediscount ratesee Equation (12.3) on page 249. In this case the discount rate is likelyto be high, reflecting the risk that the bond will not be honoured. A rate of 20 or 30 percent seems plausible.

(d) The mathematical expected return on the ticket is 2, assuming its probability ofwinning is one in a million. The present value of 2 is 2/(1+r), say 1.91 if ris 5 percent. Note that it doesnt matter whether you take the expected value and discount it, ordiscount the two possible outcomes and then take the expected value. Note too that theprice the neighbour paid is not relevant.

Teaching Note This last question is a good illustration of how risk in economics meansvariability of a return in both directions, rather than the everyday interpretation of a high chanceof something going wrong (only). The variability here is largely on the upside, so the risk isreally of a good outcome rather than a bad one.

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

13/14

-

8/10/2019 Lipsey Im Part3

14/14

Lipsey & Chrystal: Economics 12eInstructor's Manual

Oxford University Press, 2011. All rights reserved.

probably a reduced ability to price-discriminate;

whereas on the other side are opportunities such as:

cheap reproduction facilitates short production runs, which makes it economical to caterfor niche markets, emerging bands, etc;

music can be moved between different digital media easily and cheaply; back-up copies using different media can be made;

quality has probably been enhanced (although note that not everyone would agree withthis).