Linda Nochlin - The Construction o f Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting

Transcript of Linda Nochlin - The Construction o f Work and Leisure in Impressionist Painting

The Construction o f Work and Leisure inImpressionist Painting

Berthe Morisot's Wet Nurse and Julie [ 1 I of 1879is an extraordinary painting.z Even in the contextof an oeuvre in which formal daring is relativelyunexceptional, this work is outstanding. "All thatis solid melts into air"-Karl Marx's memorablephrase, made under rather different circum-stances, could have been designed for the purposeof encapsulating Morisot's painting in a nutshell. 3Nothing is left of the conventions of pictorial con-struction: figure versus background, solid formversus atmosphere, detailed description versussketchy suggestion, the usual complexities of com-position or narration. All are abandoned for a com-position almost disconcerting i n its three-part sim-plicity; a facture so open, so dazzlingly unfetteredas to constitute a challenge to readability; and acolorism so daring, so synoptic in its rejection oftraditional strategies of modeling as to be almostFauve before the fact. 4

Morisot's Wet Nurse is equally innovative in itssubject matter. For this is not the old motif of theMadonna and Child, updated and secularized, as

From Linda Nochlin, Women, Art, and Power and OtherEssays ( New York Harper & Row, Publishers, 1988), pp.37-56. Copyright © 1988 by Linda Nochlin, Reprinted bypermission of the author and flarperCollins.

13

MORISOTS WET NURSE

LINDA NOCHLIN

Tant de clairs tableaux irises, lei, exacts, primesautiers.. . .

-Sttplunc Mallanncl

it is in a work like Renoir's Aline Nursing or inmany of the mother-and-child paintings by theother prominent woman tiietnber of the Impres-sionist group, Mary Cassatt. It is, surprisinglyenough, a work scene. The "mother" in the sceneis not a real mother but a so-called seeonde mere,or wet nurse, and she is feeding the child not outof "natural" nurturing instinct but for wages, as amember of a flourishing industry. 5 And the artistpainting her, whose gaze defines her, whose activebrush articulates her form, is not, as is usually thecase, a man, but a woman, the woman whose childis being nursed. Certainly, this painting embodiesone of the most unusual circumstances in the his-tory of art-perhaps a unique one: a woman paint-ing another woman nursing her baby. Or, to putit another way, introducing what is not seen butwhat is known into what is visible, two workingwomen confront each other here, across the bodyof "their" child and the boundaries of class, bothwith claims to motherhood and mothering, both,one assumes, engaged in pleasurable activitywhich, at the same time, may be considered pro-duction in the literal sense of the word. Whatmight be considered a mere use value if the paint-ing was produced by a inerc amateur, the milkproduced for the nourishment of one's own child,

MORISOT ' S U'I:7 \UAS/i

that the female rural laborer was absent fromFrench painting of the second half of the nine-teenth century. Millet often represented peasantwomen at work at domestic tasks like spinning orchurning, and Jules Breton specialized in scenes ofidealized peasant women working in the fields.But it is nevertheless significant that in the quin-tessential representation of the labor of the femalepeasant, Millet's Cleaners, women arc repre-sented engaged not in productive labor-that is,working for profit, for the market-but rather forsheer personal survival-that is, for the nurtur-ancc of themselves and their children, picking upwhat is left over after the productive labor of theharvest is finished.? The glaneuses are thus assimi-lated to the realm of the natural-rather like ani-mals that forage to feed themselves and theiryoung-rattler than to that of the social, to therealm of productive labor. This assimilation of thepeasant woman to the position of the natural andthe nurturant is made startlingly clear in a paint-ing like Giovanni Scgantini's Two Mothers [21,which makes a visual analogy between cow andwoman as instinctive nurturers of their young.

Work occupies an ambiguous position in therepresentational systems of Impressionism, themovement to which Morisot was irrevocably con-nected; Or one might say that acknowledgment ofthe presence of work themes in Impressionism hasuntil recently been repressed in favor of discoursesstressing the movement's "engagement withthemes of urban leisure."" Meyer Schapiro, aboveall, in two important articles of the 1930s, laiddown the basic notion of impressionism as a repre-sentation of middle-class leisure, sociability, andrecreation depicted from the viewpoint of the en-lightened, sensually alert middle-class consumer.`'One could contravene this contention by pointingto a body of Impressionist works that do, in fact,continue the tradition of representing rural laborinitialed in the previous generation by Courbetand \1111ct and popularized III more sentimentalform b%- Breton and Bast i cn-Lepage Pissarro, par-ticularly, continued to develop the motif of thepeasant, particularly the laboring or resting peas-ant woman, and that of the market woman in bothI mpressionist and Neo-Impressionist vocabularies,

233

right down through the 1880s. Berthe Morisotherself turned to the theme of rural labor severaltimes: once in The Haymaker, a beautiful prepara-tory drawing for a larger decorative composition;again, in a little painting, In the Wheat Field, of1 875; and still another time (more ambiguously,because the rural "workers" in question, far frombeing peasants, are her daughter, Julie, and herniece Jeanne picking cherries) in The Cherry Treeof 1 891-92. 1 0 Certainly, one could point to a sig-nificant body of Impressionist work representingurban or suburban labor. Degas did a whole seriesof ironers;rr Caillehotte depicted floor scrapersand house painters; and Morisot herself turned atleast twice to the theme of the laundress: once inLaundresses Hanging Out the Wash [3] of 1875,a lyrical canvas of commercial laundresses plyingtheir trade in the environs of the city, paintedwith a synoptic lightness that seems to belie thelaboriousness of the theme; and another time inWoman Hanging the Washing (41, of 1881, aclose-up view where the rectangularity of the lin-ens seems wittily to reiterate the shape and textureof the canvas, the laundress to suggest the work ofthe woman artist herself. Clearly, then, the Im-pressionists by no means totally avoided the repre-sentation of work.

To speak more generally, however, interpretingImpressionism as a movement constituted primar-ily by the representation of leisure has to do asmuch with a particular characterization of labor aswith the iconography of the Impressionist move-ment. In the ideological constructions of theFrench Third Republic, as I have already pointedout, work was epitomized by the notion of rurallabor, in the time-honored, physically demanding,naturally ordained tasks of peasants on the land.The equally demanding physical effort of balletdancing, represented by Degas, with its hours ofpractice, its strains, its endless repetition andsweat, was constructed as something else, some-thing different: as art or entertainment. Of coursethis construction has something to do with theway entertainment represents itself: often thewhole point of the work of dancing is to make itlook as though it is not work, that it is spontaneousand easy.

is now to be understood as an exchange value. Inboth cases-the milk, the painting-a product isbeing produced or created for a market, for profit.

Once we know this, when we look at the pictureagain we may find that the openness, the disem-bodiment, the reduction of the figures of nurserand nursling almost to caricature, to synopticadumbration, may be the signs of erasure, of ten-sion, of the conscious or unconscious occlusion ofa painful and disturbing reality as well as the signsof daring and pleasure-or perhaps these signs,under the circumstances, may be identical, insepa-rable from each other. One might say that thisrepresentation of the classical topos of the mater-nal body poignantly inscribes Morisot's conflictedidentity as devoted mother and as professionalartist, two roles which, in nineteenth-century dis-course, were defined as mutually exclusive. The

W''et Nurse, then, turns out to be much morecomplicated than it seemed to be at first, and itsstimulating ambiguities may have as much to dowith the contradictions involved in contemporarymythologies of work and leisure, and the way thati deologies of gender intersect with these paired

LINDA NQCHLIN

notions, as they do with Morisot's personal feel-ings and attitudes.

Reading The Wet Nurse as a work scene inevi-tably leads me to locate it within the representa-tion of the thematics of work in nineteenth-cen-tury painting, particularly that of the womanworker. It also raises the issue of the status of workas a motif in Impressionist painting-its presenceor absence as a viable theme for the group ofartists which counted Morisot as an active mem-ber. And I will also want to examine the particularprofession of wet-nursing itself as it relates to thesubject of Morisot's canvas.

How was work positioned in the advanced artof the later nineteenth century, at the time whenMorisot painted this picture? Generally in the artof this period, work, as Robert Herbert hasrroted, 6 was represented by the rural laborer, usu-ally the male peasant engaged in productive laboron the farm. This iconography reflected a certainstatistical truth, since most of the working popula-tion of France at the time was, in fact, engagedin farm work. Although representations of themale farm worker predominated, this is not to say

2 Ciovaimi Scgantini. Ac Tim Nlothers, detail, 1868 Milan, Calleria d'Arte Moderna.

724

3. l3crthc Morisot,Laundresses Hanging Out theWash, 1875. Washington,D C., National Gallery,titellon Collection.

But there is a still more interesting generalpoint to be made about Impressionism and itsreputed affinity with themes of leisure and plea-sure. It is the tendency to conflate woman'swork-whether it be her work in the service orentertainment industries or, above all, her work inthe home-with the notion of leisure itself. As aresult, our notion of the iconography of work,framed as it is by the stereotype of the peasant inthe fields or the weaver at his loom, tends to ex-clude such subjects as the barmaid or the beerserver from the category of the work scene andposition them instead as representations of leisure.One might even say, looking at such paintings asManet's Bar at the Polies-Bergere or his BeerServer from the vantage point of the new women'shistory, that middle- and upper-class men's leisureis sustained and enlivened by the labor of women:entertainment and service workers like those rep-resented by Manet. 12 It is also clear that theserepresentations position women workers-bar-maid or beer server-in such a way that they seemto be there to be looked at-visually consumed, asit were-by a male viewer. In the Beer Server of

LINDA NOCHLIN

1878, for example, the busy waitress looks outalertly at the clientele, while the relaxed male inthe foreground-ironically a worker himself, iden-tifiable by his blue smock-stares placidly at thewoman performer, half visible, doing her act onthe stage. The work of cafe waitresses or perform-ers, like those represented by Degas in his pastelsof cafe concerts, is often connected to their sexual-ity or, more specifically, the sex industry of thetime, whether marginally or centrally, full time orpart time. What women, specifically lower-classwomen, had to sell in the city was mainly theirbodies. A comparison of Manet's Ball at theOpera-denominated by the German critic JuliusMeier-Graefe as a Pleischehorse, or flesh mar-ket-with Degas's Cotton Market in New Orleansmakes it clear that work, rather than being anobjective or logical category, is an evaluative oreven a moral one. Men's leisure is produced andmaintained by women's work, disguised to looklike pleasure. The concept of work under theFrench Third Republic was constructed in termsof what that society or its leaders stipulated asgood, productive activity, generally conceived of

238

7. Jose de Frappa, Bureau de Nourriee.

daughter and her wet nurse 2 I creating a sociologi-cal document of a particular kind of work or evena genre scene of some engaging incident involvedin wet-nursing. Both Julie and her wet nurse serveas motifs in highly original Impressionist paint-ings, and their specificity as documents of socialpractice is hardly of conscious interest to the cre-ator of the paintings, who is intent on creating anequivalent for her perceptions through visualqualities of color, brushwork, light, shape-or thedeconstruction of shape-and atmosphere. Nordo we think of Morisot as primarily a painter ofwork scenes; she was, indeed, one of those artistsof the later nineteenth century-like Whistlerand Manet, among others-who helped constructa specific iconography of leisure, figured by youngand attractive worsen, whose role was simply to bethere, for the painter, as a languid and self-ab-sorbed object of aesthetic contemplation-a kindof human still life. Her Portrait of ;Mme AlarieHubbard of 1874 and Young Girl Reclining of1893 are notable examples of this genre. Morisot

LINDA NOCHI.I N

is associated, quite naturally, not with workscenes, however ambiguous, but rather with therepresentation of domestic life, mothers, or, morerarely, fathers-specifically her husband, EugeneManet-and daughters engaged in recreation [8].This father-and-daughter motif is, like the themeof the wet nurse, an unusual one in the annals ofI mpressionist painting, and one with its own kindsof demands. Male Impressionists who, like Mori-sot, turned to the domestic world around them forsubject matter, painted their wives and children asa matter of course. Here is a case where being awoman artist makes an overt difference: Morisot,in turning to her closest relatives, paints a fatherand child. She depicts her husband and daughterdoing something concrete-playing with a boatand sketching or playing with toy houses-andwith a vaguely masculine air.

Despite the fact that scenes of leisure, languor,and recreation are prominent in %torisot's oeuvre,there is another way we might think of work i nrelation to her production. The notion of the work

MORISQT S tr'ET;I MSE

selves, in general they preferred a healthy wetnurse to a nervous new mother. Few tipper-classwomen in the later nineteenth century wouldhave dreamed of breast-feeding their own chil-dren; and only a limited proportion of women ofthe artisan class, who had to work themselves orwho lived in crowded quarters, had the chance todo so. If Renoir proudly represented his wife nurs-i ng their son Jean, it was not because it was so"natural" for her to do so, but perhaps because, onthe contrary, it was not. Renoir's Wife, in any case,was not of the same social class as Berthe Morisot;she was of working-class origin. Bcrtlhe Itlorisot,then, was being perfectly "natural" within theperimeters of her class in hiring a wet nurse. Itwould not be considered neglectful and certainlywould not have to be excused by the fact that shewas a serious professional painter: it was simplywhat people of her social station did.

The wet nurse, in various aspects of her career,was frequently represented in popular visual cul-ture, and her image appeared often in the press ortit genre paintings dealing with the typical trades

6. Edgar Degas, Carriage at the Races, 1869. Boston, Museum of Finc Arts.

?37

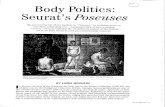

or professions of the capital. A forgotten painterof the later nineteenth century, Jose de Frappa, inhis Bureau de 1Vourrice 17) depicted the medicalexamination of potential wet nurses in an employ-ment bureau. Husband, mother-in-law, and doc-tor evidently participated in the choice of a candi-date. Wet-nursing was frequently the subject ofhumorous caricatures right down to the beginningof the twentieth century, when sterilization andpasteurization enabled mothers to substitute thenewly hygienic bottle for the human breast-andthereby gave rise to cartoons dealing with the wetnurse attempting to compete with her replace-ment.ze With her ruffled, beribboned cap andjacket or cape, she was frequently depicted in illus-trations of fashionable parks, where site aired hercharges, or in those of upper-class households. Hercharacteristic form could even serve to illustratethe letter A'-for nourrice-in a children's alpha-bet. Degas, like Seurat, was evidently struck by thetypical back view of this familiar figure andsketched it in one of his notebooks.

Morisot i s not, of course, in her paintings of her

23 6

ernment stepped in to regulate the industry in1874 with the so-called Lot Roussel, which super-vised wet nurses and their clients on a nationwidebasis. 14 Members of the aristocracy or upper hour-geoisie such as Berthe Morisot, however, did nothave to resort to this "regulated" industry. Theyusually hired a nourrice sur lieu, or live-in wetnurse, who accompanied the infant, took it to thepark, and comforted it-but was there mainly toprovide the baby with nourishment. 15 The omni-presence of the wet nurse in the more fashionablepurlieus of Parisian society is indicated in Degas'sCarriage at the Races [6], where the Valpingons,husband and wife, are accompanied by their dog,by their son and heir, Henri, and by the veritablestar of the piece, the wet nurse, depicted in the actof feeding the baby. 16 A foreign painter like theFinnish Albert Edelfelt, when depicting thecharms of Parisian upper-class life, quite naturallyi ncluded the wet nurse in his Luxembourg Gar-

dens, a painting of 1887 now i n the Antell Collec-tion in Helsinki; and Georges Seurat incorporatedthe figure, severely geometrized, into the crosssection of French society he represented in 11

Sunday on the Island of I,a Grande-Jatte.

The wet nurse was, on the one hand, consideredthe most "spoiled" servant in the house and, at

LINDA NOCIILIN

S. Anonymous photograph,wet nurses in a public parkabout 1900.

the same time, the most closely watched and su-pervised. She was in some ways considered morelike a highly prized mileh cow than a humanbeing. Although she was relatively highly paid forher services, often bringing home 1,200 to 1,800francs per campaign-her salary ranked just underthat of the cordon bleu chef 17-and was oftenpresented with clothing and other valuable gifts,her diet, though plentiful and choice, was care-fully monitored and her sex life was brought to ahalt; and of course, she had to leave her own babyat home in the care of her own mother or anotherfamily member.'a

The wet nurse was always a country woman,and generally from a specific region of the coun-try: the Morvan, for instance, was consideredprime wet-nurse territory. I 9 VVet-nursing was theway poor country women with few valuable skillscould snake a relatively large sum of money: sellingtheir services to well-off urban families. The anal-ogy with today's surrogate mothers snakes itselffelt immediately, except that the wet nurse wasnot really the subject of any moral discourse aboutexploitation; on the contrary: although some doc-tors and child-care specialists complained aboutthe fact that natural mothers refused to take na-ture's way and breast-feed their children them-

MORISQT'S U'ET,\URSF

as wage-earning or capital production. Women'sselling of their bodies for wages did not fall underthe moral rubric of work; it was constructed assomething else: as vice or recreation. Prostitutes(ironically, referred to colloquially as "workinggirls" today), a subject often represented byDegas, like the businessmen represented in hisMembers of the Stock Exchange, are of courseengaging in a type of commercial activity. Butnobody has ever thought to call the prints fromDegas 's monotype series of brothel representa-tions "work scenes," despite the fact that prosti-tutes, like wet nurses and barmaids and laun-dresses, were an important part of the work forceof the great modern city in the nineteenth cen-tury, and in Paris, at this time, a highly regulated,government-supervised form of labor.t 3

If prostitution was excluded from the realm ofhonest work because it i nvolved women sellingtheir bodies, motherhood and the domestic laborof child care were excluded from the realm ofwork precisely because they were unpaid.Woman's nurturing role was seen as part of hernatural function, not as labor. The wet nurse. (5j,

4. Berthe Morisot,Woman Hanging theWashing, 1881.Copenhagen, lvyCarlsberg Clyptotek.

235

then, is something of an anomaly in the nine-teenth-century scheme of feminine labor. She islike the prostitute in that she sells her body, or itsproduct, for profit and her client's satisfaction;but, unlike the prostitute, she sells her body for avirtuous cause. She is at once a mother-secondemere, remplagant--and an employee. She is per-forming one of woman's "natural" functions, butshe is performing it as work, for pay, in a way thatis eminently not natural but overtly social in itsconstruction.

To understand Morisot's Wet Nurse and /ulie,one has to locate the profession of wet-nursingwithin the context of nineteenth-century socialand cultural history. Wet-nursing constituted alarge-scale industry in France in the eighteenthand nineteenth centuries. In the nineteenth cen-tury, members of the urban artisan and shopkeep-ing classes usually sent their children out to benursed by women in the country so that wiveswotild be free to work. So large was the industrienourrieiere and so patent the violations of sanita-tion, so high the mortality rate and so unsteadyti,e financial arrangements involved that the gov-

MORIscrr's w v- NURSE

of painting itself is never disconnected from herart and is perhaps allegorized in various toilettescenes in which women's self-preparation andadornment stand for the art of painting or subtlyrefer to it.zz A simultaneous process of lookingand creating are prime elements of a woman'stoilette as well as picture-making, and sensualpleasure as well as considerable effort is i nvolvedi n both. One could even go further and assert thati n both-maquillage and painting-a private cre-ation is being prepared for public approbation.

Painting was work of the utmost seriousness forMorisot. She was, as the recent exhibition cata-logue of her work reveals to us,Z 3 unsparing ofherself, perpetually dissatisfied, often destroyingworks or groups of works that did not satisfy herhigh standards. Her mother observed that when-

ever she worked, she had an "anxious, unhappy,almost fierce look," adding, "This existence ofhers is like the ordeal of a convict in chains." 24

There is another sense in which Morisot'soeuvre may be associated with the work of paint-ing: the way in which the paintings reveal the actof working which creates them, are sparkling, in-vigorating, and totally uneffortful-looking registersof the process of painting itself. In the best ofthem, color and brushstroke are the deliberatelyrevealed point of the picture: they are, so to speak,works about work, in which the work of lookingand registering the process of looking in paint oncanvas or pastel on paper assumes an importancealmost unparalleled in the annals of painting. Onemight almost say that the work of painting is notso strongly revealed until the time of the late

8. Berthe Morisot, Eugene Manet and His Daughter, lulic, in the Garden, 1883. Private collection,

239

MORI$01''S WET NURSE

i mpossible to distinguish or understand anythingat all." 26

In her late Girl with a Greyhound (10}, a por-

trait of Julie with a dog and an empty chair,painted in 1893, Morisot dissolves the chair intoa vision of evanescent lightness: a work of omis-sion, of almost nothingness. Compared with it,Van Gogh's famous Gauguin's Chair looks heavy,solid, and a little overwrought. Yet Morisot's chair

is moving, too. Its ghostliness and disernbodimentremind us that it was painted shortly after herhusband's death, perhaps as an emblem of hisabsent presence within the space of his daughter'sportrait. And perhaps for us, who know that shepainted this at the end of her life, it may consti-tute a moving yet self-effacing prophecy of herown impending death, an almost unconsciousmeans of establishing-lightly, only in terms ofthe work itself-her presence within an linagerepresenting, for the last time, her beloved onlychild.

I n insisting on the importance of work, specifi-cally the traces of manual activity, in Morisot'sproduction, I am not suggesting that Morisot'swork was the same as the onerous physical laborinvolved in farm work or the routine mechanicalefforts of the factory hand-nor that it was identi-cal with the relatively mindless and constrictedduties of the wet nurse. We can, however, seecertain connections: in a consideration of both thework of the wet nurse and that of the woman artistthe element of gender asserts itself. Most criticsboth then and now have emphasized Morisot'sgender; her femininity was constructed from anessentialist viewpoint as delicacy, instinctiveness,naturalness, playfulness-a construction implyingcertain natural gendered lacks or failures: lack ofdepth, of substance, professionalism or leadership,for instance. `h'hy else has Xlorisot always beenconsidered as somehow a secondary Impressionist,despite her exemplary fidelity to the movementand its aims? Why has her very flouting of thetraditional "law's" of painting been seen as a weak-ness rather than a strength, a failure or lack ofknowledge and ability rather than a daring trans-gression? Why should the disintegration of formcharacteristic of her best work not be considered

24 1

a vital questioning of Impressionism from within,a "making strange" of its more conventional prac-tices? And if we consider that erosion of form tobe a complexly mediated inscription of internal-ized conflict-motherhood versus profession-then surely this should be taken as seriously as themore highly acclaimed psychic dramas of maleartists of the period: Van Gogh's struggle with hismadness; Cczaune's with a turbulent sexuality;Gauguin's with the countering urgencies of so-phistication and primitivism.

I would like to end as I began, with Karl Marx'smemorable phrase: "All that is solid melts intoair." But now I would like to consider the wholepassage, from the Communist Manifesto, from

which I (and Marshall Berman, author of a booktitled by that passage) extracted it. Here is thewhole passage: "All fixed, fast-frozen relations,with their train of ancient and venerable preju-dices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they canossify: All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy

is profaned, and men at last are forced to face. . . the real conditions of their lives and theirrelations with their fellow men."

I am not in any sense suggesting that Morisotwas a political or even a social revolutionary-Earfrom it. But I am saying that her strange, fluid,unclassifiable, and contradiction-laden image lVet

Nurse and Julie inscribes many of those character-istic features of modernism and modernity thatMarx is of course referring to in his celebratedpassage-above all, modernism's profoundlydeconstructive project. Sweeping away "all fixedand frozen relations with their accompanyingprejudices and opinions"-this is certainly Mori-

sot's project as well. And in some way too, she isin this picture, being forced to face, at the sametime that it is impossible for her fully to face, thereal condition of her life and her relations with afellow woman. Thinking of Marx's words, looking

at k1orlsot's painting, I sense these real conditionshovering on the surface of the canvas, a surface asyet not fully explored, untested but still potentiallythreatening to "ancient and venerable prejudicesand opinions"-about the nature of work, aboutgender, and about painting itself.

24 0

9. Berthc Morisot,Self-Portrait, 188"5 ArtInstitute of Chicago.

1 0. Berthc Morisot,Cirl with a Creyhound(lulie Vfanet), 1893.Paris, MuskMarmottan

LINDA NOCHLIN

Monet or even that of Abstract Expressionism,although for the latter, of course, looking and reg-istering were not the issue. 25

Even when Morisot looked at herself, as in her1 885 Self-Portrait with Julie, boldly, on unprimedcanvas, or in her pastel Self-Portrait [91 of thesame year, the work of painting or marking wasprimary. These are in no sense flattering or evenconventionally penetrating self-portraits: they are,especially the pastel version, working records of anappearance, deliberate in their telling asymme-tries, their revelation of brushwork or marking,unusual above all for their omissions, their selec-tive recording of a motif that happens to be theauthor's face. The pastel Self-Portrait is almostpainfully moving. It is no wonder that criticssometimes found her work too sketchy, unfin-ished, bold to the point of indecipherability. Re-ferring to two of her pastels, for example, CharlesEphrussi declared: "One step further and it will be

242NQTI;S

l. Preface to the catalogue of the posthumous exhibi-tion of Berthe Morisot's paintings, Durand-Rue] Gallery,

Paris, March 5-23, 1896.2. The painting was exhibited under the title Nourriee

et behe ( Wet Nurse and Baby) at the Sixth I mpressionist

Exhibition of 1880. It is also known under the title La

Nourrice Angele allaitant Julie Manet ( The Wet Nurse

Angle Feeding Julie Manet) and Nursing. See the exhibi-

tion catalogue The New fainting: Impressionism, 1874-

1886, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and National

Gallery of Art. Washington, D.C., 1986, No. 110, p. 366,and Charles F. Stuckey and William P. Scott, Berthe

Morisot: Impressionist, exhibition catalogue, National

Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.: Kimball Art Museum,

Fort Worth, Texas; Mount Holyoke College Art Museum,1987-88, Fig. 41, p. 89 and p. 88.

3. Karl Marx's statement may be found in Robert C.Tucker, ed., 11e Marx-Engels Reader (New York: Nor-ton, 1978), p. 476.

h

4. The critic Gustave Geffroy responded to the IVetAJ"-s'e u..iatu.. quelitioe whstt its tewi,Werl 1'vlutisut's wink

from the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition in La Justice of

April 21, 1881, by waxinQp lyrical: "The forms are alwaysvague in Bcrthe MOTiSO[ s paintings, but a strange lifeanimates them. Tile artist has found tile means to fix theplay of t:ulurs, me yuivenng between things and the airthat envelops them. - . Pink, pale green, faintly gilded

Irt sings with an i nexpressible harmony." Cited' i n Thew Painting. Impressionism, 1874-1886, p. 366,5. Indeed, one might suspect that the unusual sketchi-

ness and rapidity or the brushwork may have had some-thing to do with Morisot's haste to complete her paintingwithin tlro pp"""

"f;4tingle nursing ceccion. Neverthelecc,

she obviously did not consider the painting a mere prepara-tory study, since she exhibited it in public as a finishedwork.

6 Robert Herbert, "City vs. Country: The Rural Imagei n French Painting from Millet to Gauguin," Artforunr 8( February 1970): 44-55.

7 See Jean-Claude Chamborcdon, "Peintures des rap-ports sociaux et invention de 1'eternel paysan: Les deuxmani&res de Jean-FranWis Millet," Actes do la rechercheet sciences sociales, Nos. 17-18 ( November 1977): 6-28.

8. Thomas Crow, "Modernism and Mass Culture in theVisual Arts," in Alodemism and Modernit), : Tire Vancou-ver Conference Papers, ed. Benjamin H. D. Buchloh,Serge Guilbaut, and David Solkin, Nova Scotia, "I'he NovaScotia College of Art and Design, 1983, p. 226,

9 See Meyer Schapiro, "The Social Bases of Art," inProceedings of the First ;1 rtists • (:ongress against War andFascism, New York, 1936, pp. 31-37, and "The Nature

LINDA NOCHLIN

of Abstract Art," Tile Marxist Quarterly' I (January 1937):

77-98, reprinted in Schapiro, Alodem Art: 77 re Nineteenth

and 7lventieth Centuries ( New York: George Brazi]lcr),

especially pp. 192--93.1 0. For an illustration of The Nay maker, see Herthc'

Morisot: Impressionist, colorplate 93, p. 159; (or In the

Vt•'heat(eld, Kathleen Adler and Tamar Garb, Berthe

Morisot (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1987),

Fig. 89; and The Cherry Tree, Berthe Aforisot: Impression-

ist, co)orplate 89, p. 153.I l

For a detailed discussion of Degas's ironers and

laundresses, sec Eunice Lipton, Looking into Degas: (In-

easy Images of Women and.1fodem Life ( Berkeley: Uni-versity of California Press, 1986), pp. 116-50.

1 2. For the role of tile barmaid i n French nineteenth-

centory society and iconography, see 1'. ). Clark, The

Paintingof Modern Life: Paris in the ArtofAlanetand Ills

Followers (Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press,1984), pp. 205-58, and Novalenc Ross, Manet's "Bar atthe Folies-Bergere"and the _'ffy•ths of Popular illustration( Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1982).

1 3 For information about government regulation ofProstitution. see Alain Corbin, I.as Fillas de nose: Miseresexuelle et prostitution aux 19e et 20e sieeles ( Paris, 1978);for tile representation of prostitution in the art of the laternineteenth century, see Hollis Clayson, ' Avant-Garde andPoin,bier I mages of 19th Century French Prostitution:The %'latter of klodernicm, Modernity and Social Ideol-ogy," i n .11odernism and Modernity, pp. 43-64. Meier-Gracfc uses the term "Flcischborse" i n Fdouard Allanet( Munich: Piper Vcrlag, 1912), p. 216.

1 4- For the Roussel Law of December 23, 1874, secGcrorge U. Sussman, Selling Mothers' f1lilk: The Wet-Nursing Business it, France: 1715-1914 ( Urbana: Univer-sity of Illinois Press, 1982), pp. 128-29 and 166-67.

1 5. For an excellent examination of the role of the wetnurse in the nineteenth century, focusing on the nourricesur lieu and including an analysis of tile medical discoursesurrounding tile issue of maternal breast-feeding, seeFanny f ay-Sallois, Les _fourrices a Paris au .k7A'e siccle(Paris: Payot, 1980).

1 6. I am grateful to Paul Tucker for pointing out thepresence of the wet nurse in this painting.

1 7_ Fay-Sallois, Les ;fourricec it Paris aux -VI.Ve siccle,p. 201.

1 8. I"or tile figures of the wages cited, see Sussman,Selling Alothers" "lilk: The Ifet-,i'rrrsirtg Business inFrance. 1715-191y. p. 155, and for the salary of the live-inwet nurse and her treatment grncrally, see Fay-Sallois, Les, 1 orrrrices h Paris aux . \7fe siccle, pp. 20(1-39.

1 9. Sussman, Selling , 19others'.11ilk 771e IT ,et-Nursing

MORISOT'S WET NURSE

Business in France: 1715-1914, pp. 152-54.20. See, particularly, the vicious cartoon depicting a wet

nurse attempting to boil her breast in emulation of bottlesterilization, published by Fay-Sallois, Les Nourrices cParis au XIXe siecle, p. 247. Other interesting cartoonsfeaturing wet-nursing and the practices associated with itappear on pp. 172-73, p. 188, and p. 249 of this work,which is amply illustrated-

2 1. There are at least two other works by Morisot repre-senting her daughter, Julie, and her wet nurse: an oil paint-i ng, Julie with Her Nurse, 1880, now in the Ny CarlsbergGlyptotek, Copenhagen, reproduced as Fig. 68 i n Adlerand Carb, Berthe Morisot, and a watercolor entitledLuncheon in the Country of 1879, i n which the wet nurseand baby are seated at a table with a young boy, probablyMorisot's nephew Marcel Gobillard, reproduced as Color-plate 32, p. 77, i n Stuckey and Scott, Berthe Morisot:Impressionist.

22. See, for example, Woman at Her Toilette, ca. 1879,

24 3

in the Art Institute of Chicago or Young Woman Powder-ing Ha Face of 1877, Paris, Mus6e d'Orsay.

23. Charles Stuckey and William Scott, Berthe Morisot-Impressionis4 National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. ;Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas; Mount Ho-lyoke College Art Museum, 1987-88.

24. Stuckey and Scott, Berthe Morisok- Impressionis4 p.187.

25. See, for example, Charles Stuckey's assertion that,i n the case of Wet Nurse and Julie, "it is difficult to thinkof a comparably active paint surface by any painter beforethe advent of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s."Berthe Morisot.- Impressionis4 p. 88.

26. Cited in Stuckey and Scott, Berthe Morisot: Impres-sionist, p. 88.

27. Cited by Marshall Berman in All That Is Solid Meltsinto Air. Tine Experience of Modernity ( New York: Simon& Schuster, 1 982), p. 21.