Lieberman Nested (1)

-

Upload

leonardo-leite -

Category

Documents

-

view

237 -

download

1

Transcript of Lieberman Nested (1)

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

1/18

American Political Science Review Vol. 99, No. 3 August 2005

Nested Analysis as a Mixed-Method Strategyfor Comparative ResearchEVAN S. LIEBERMAN Princeton University

D

espite repeated calls for the use of mixed methods in comparative analysis, political scientistshave few systematic guides for carrying out such work. This paper details a unified approach

which joins intensive case-study analysis with statistical analysis. Not only are the advantagesof each approach combined, but also there is a synergistic value to the nested research design: forexample, statistical analyses can guide case selection for in-depth research, provide direction for morefocused case studies and comparisons, and be used to provide additional tests of hypotheses generatedfrom small-N research. Small-N analyses can be used to assess the plausibility of observed statisticalrelationships between variables, to generate theoretical insights from outlier and other cases, and todevelop better measurement strategies. This integrated strategy improves the prospects of making validcausal inferences in cross-national and other forms of comparative research by drawing on the distinctstrengths of two important approaches.

L

ong-standing methodological debates highlight-ing inherent tradeoffs in the main modes of com-parative analysis have tended to force scholars to

choose between one of two imperfect approaches. Onthe one hand, even while defending its merits, Lijphart(1971, 685) succinctly identified the central shortcom-ing of the comparative method as the problem ofmany variables, small number of cases. In the yearsto follow, some scholars argued that such attempts todraw generalconclusions from intensive analysis of oneor a few cases have been flawed by various problems ofselection bias, lack of systematic procedures, and inat-tention to rival explanations (e.g., Achen and Snidal1989; Geddes 1990; King, Keohane, and Verba 1994).Alternatively, other scholars have argued not only thatsome of the critiques of qualitative research may be

overdrawn and the contributions of these works un-derappreciated, but also that the complex phenomenaand causal processes associated with big, national-leveloutcomes require a more close-range analytic tool thatis less likely to generate spurious results (e.g., Collier,Brady, and Seawright 2004; Collier and Mahoney 1996;Munck 1998; Rogowski 1995). Qualitatively orientedscholars have their own tradition of challenging thestatistical approach, including Sartoris (1970) power-ful invective against conceptual stretching, which inturn has been refuted by scholars such as Jackman(1985), who argues that the comparative method is aweak approximation of the statistical method, (165)and that cross-national statistical analyses have a lot

to offer (179).

EvanS. Lieberman is AssistantProfessorof Politicsat PrincetonUni-versity, 239 Corwin Hall,Princeton,NJ 08544 ([email protected]).

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 2002 An-nual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston,MA, and at a 2004 Workshop on multilevel models at PrincetonUniversity. In addition, Larry Bartels, Andrew Bennett, NancyBermeo, David Collier, Michael Coppedge, John Gerring, MarcMorj e Howard, David Laitin, Phil Shively, students inmy QualitativeMethods graduate seminars at Princeton, members of the PrincetonComparative Politics Working Group, three anonymous reviewersand the editorof theAPSR all provided extremely helpful commentsand suggestions.

Although such back-and-forth debate has served toilluminate the shortcomings in various methodologicalapproaches, it has also provided momentum for greater

synthesis of research styles and findings. Two decadesafter publication of Lijpharts (1971) article, Collier(1991) pointed out that advances in both statisticaland small-N approaches, and evidence of increasingcommunication across the two approaches, held greatpromise for scholarly progress. Both King, Keohane,and Verbas Designing Social Inquiry (1994) and Bradyand Colliers Rethinking Social Inquiry (2004) havedemonstrated that each mode of analysis can be suc-cessfully used to achieve similar social scientific ends,while using somewhat different tools. And yet, thesecontributions have largely assumed that there will con-tinue to be substantial divisions of scholarly labor, even

as research findings across the methodological divideare often ignored. In a somewhat different formulation,several scholars have called for greater integration ofmethodological approaches (Achen and Snidal 1989;Tarrow 1995) or the mixing of methods. Despite theinitially appealing nature of such a resolution, scholarshave received little guidance about how to blend thesemodes of analysis. As Bennett (2002) points out in apaper reviewing some of the ways in which case study,statistical, and formal methods have been combined inpolitical science, there is a need to focus on the waysin which such combinations could be increased andimproved. Clearly, not all forms of mixed strategieswill provide greater insights into particular research

problems. In fact, some may simply generate moreconfusion than clarity.

This article systematizes a unified mixed methodapproach to comparative research, which I call nestedanalysis.1 It combines the statistical analysis of a large

1 In this article, I discuss Coppedges (2005) use of what he callsnested inference in an analysis of the breakdown of democracyin Venezuela. Although he is methodologically self-conscious in de-scribing how case study and quantitative/large sample analyses arecombined in an application, that study represents one variation ofthe approach I describe in this article, which attempts to anticipateandsystematize a broader range of research problems and strategies.

435

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

2/18

Nested Analysis for Comparative Research August 2005

sample of cases with the in-depth investigation of oneor more of the cases contained within the large sample.This would include the study of a nation-state nestedwithin an analysis of 50 nation-states; the study of twoprovinces nested within an analysis of 20 provinces; orthe study of an institution nested within an analysisof 100 institutions. Although all of the examples dis-cussed in the article are concerned with country- or

national-level analyses, the strategies described hereshould apply to any comparative analysis of socialunits for which both quantitative and in-depth casestudy data can be obtained. Thus, the approach couldbe applied to the analysis of individual behaviors orattitudes, but only if the researcher were willing andable to gather new data about particular individualsthrough intensive interview or related approaches incombination with quantitative analyses of large-scalesurveys. If the study concerned specific, well-studiedindividuals, such as presidents or legislators, for whichadditional information could be gleaned from in-depthresearch of particular cases, the approach describedhere would indeed apply.2

I should be clear that the strategy described hereis quite distinct from the message outlined by King,Keohane, and Verba (1994). Rather than advocat-ing that there are lessons useful for qualitative re-searchers that can be gleaned from the logic of sta-tistical analysis (or vice-versa, an argument they donot make) I show that there are specific benefits tobe gained by deploying both analytical tools simulta-neously, and I emphasize the benefits of distinct com-plementarities rather than advocating a single style ofresearch. Although the move from small-N analy-sis (SNA) to nested analysis obviously requires thatone find additional cases (King, Keohane, and Verba

1994, 20829), it assumes that it may be extremelydifficult and inefficient to gather perfectly equivalentdata for each case, and that the inferential oppor-tunities from the large-N analysis (LNA) will bedistinctive.3

OVERVIEW OF THE NESTED ANALYSISAPPROACH

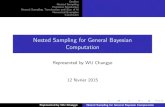

I describe a set of strategies for gaining maximum ana-lytic leverage when combining SNA and LNA within asingle framework (summarized in Figure 1). Althoughthere is an enormous variety of analytical strategiescontained under these two subheadings, both in terms

of actual number of units analyzed and the scope ofthe time dimension considered, for the purposes of this

2 However, for most analyses of individual behaviors or attitudes,for which the large-N component of the data is contained in asurvey, I would not expect this approach to be feasible, becausescholars are unlikely to be able to conduct further in-depth researchwith the original respondents. Moreover, the prospect of explainingthe exceptional nature of a particular individual is unlikely to be ofintrinsic interest in the way scholars are likely to be interested in theparticularities of larger social units, such as national states.3 By cases I mean the shared unit of analysis. In cross-nationalresearch, each case is a country.

paper, it is useful to make a general distinction: I defineLNA as a mode of analysis in which the primary causalinferences are derived from statistical analyses whichultimately lead to quantitative estimates of the robust-ness of a theoretical model; I define SNA as a mode ofanalysis in which causal inferences about the primaryunit under investigation are derived from qualitativecomparisons of cases and/or process tracing of causal

chains within cases across time, and in which the rela-tionship between theory and facts is captured largelyin narrative form.4 The strategy of combining the twoapproaches aims to improve the quality of conceptu-alization and measurement, analysis of rival explana-tions, and overall confidence in the central findings ofa study. The promise of the nested research design isthat both LNA and SNA can inform each other to theextent that the analytic payoff is greater than the sumof the parts. Not only is the information gleaned com-plementary, but also each step of the analysis providesdirection for approaching the next step. Most promi-nently, LNA provides insights about rival explanationsand helps to motivate case selection strategies for SNA,

whereas SNA helps to improve the quality of measure-ment instruments and model specifications used in theLNA.

As a thumbnail sketch, the approach involves start-ing with a preliminary LNA and making an assess-ment of the robustness of those results. If the modelis well specified and the results are robust, one pro-ceeds to Model-testing Small-N Analysis, and if not,to Model-building Small-N Analysis. In each case, asshown in Figure 1, the analyst must again make assess-ments about the findings from such analysis, using di-rections and insights gleaned from the SNA, and thoseassessments provide a framework for either ending the

analysis or carrying out additional iterations of SNA orLNA. Detailing the nature of the particular strategiesfor carrying out each type of analysis, as well as thenature of the assessments, is the central goal of theremainder of the paper.

Nested analysis is resolutely catholic in its assump-tions and objectives. It assumes an interest in both theexploration of general relationships and explanationsand the specific explanations of individual cases andgroups of cases. For example, a nested research designimplies that scholars will pose questions in forms suchas What causes social revolutions?, while simultane-ously asking questions such as What was the causeof social revolution in France? Nested analysis helps

scholars to ask good questions when analyzing theirdata and to be resourceful in finding answers.

Before proceeding to detail the procedures asso-ciated with nested analysis, it is important to situ-ate the strategy within the context of two other pro-posals for alternative methodological approaches.First, Charles Ragin (1987, 2000) attempts to steer amiddle path between quantitative and qualitative

4 As is discussed in the text, qualitative analysis is the hallmark, butnot the defining feature of SNA. Within-case analyses may include arange of statistical analyses of data that are not available across thelarger sample of primary unit cases (i.e., countries).

436

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

3/18

American Political Science Review Vol. 99, No. 3

FIGURE 1. Overview of the Nested Analysis Approach

Start: Preliminary Large-N Analysis (LNA)

YesNo

No

Yes

Yes

No

Model-testing Small-N Analysis (Mt-SNA) Model-building Small-N Analysis (Mb-SNA)

End analysis (I I I)

No

Yes

Idio

syn

crati

ccase

Assessment: Robust and satisfactory results?

Assessment: Does the SNA fit

the original model?Assessment: Does the SNA suggest a

new, coherent model?

Assessment:

Reasons for poor

fit in SNA?

Assessment:

Possible to test new

model with LNA?

Theoretic

alF

law

Repeat

Model-testing

Do

Model-building

Case selection: On-the-line only

Deliberate or random

Case selection: On- and Off-the-line

End analysis (II)

Model-testing LNA

End analysis (IV)End analysis (I)

Deliberate only

research with his specification of a Boolean approachand elaboration of a fuzzy set/Qualitative Compar-ative Analysis (FsQCA). Ultimately, his strategy fo-cuses on integrating close-range analysis to ensure theproper delineation of theoretically relevant popula-tions and valid classification of cases, with an algorithmthat finds the necessary and sufficient conditions asso-ciated with particular sets of phenomena. Second, theBayesian approach (Western and Jackman 1994), likethe FsQCA approach, and distinct from the classicalregression model, relies heavily on investigator knowl-edge of cases and processes, but does this through the

formal introduction of subjective probability estimates.However, neither the stated approaches to Bayesiananalysis nor FsQCA provide direction about how togather additional research in the SNAthey assumea seamless discovery process of outside knowledge,with almost no focus on the specific role of gather-ing and reporting case materials. In making prescientcritiques of standard cross-country regression analy-ses, advocates of both the Bayesian and the FsQCAapproaches allow for the inductive incorporation ofknowledge from cases, but as currently formulated,they provide little guidance about the cases we shouldstudy or what role they ought to play in the assess-

ment of theoretical findings.5 As such, both of theseapproaches may serve as partial correctives to cross-country regression analysis, but neither is complete.For the purposes of nested analysis, both FsQCA andBayesian approaches may be used in the LNA, andthe guidelines developed here for combining such ap-proaches with SNA should still apply.

It is also important to indicate that the nested anal-ysis approach is agnostic with respect to the sourceof theory formation. Although others have explicitlyincluded the development of formalthat is, math-ematically specifiedtheory in their discussions andproposals for integrating approaches to the study ofcomparative politics (Bates et al. 1998; Laitin 2002),the nested analysis approach has no particular affinityfor any single theoretical approach, except for a moregeneral positivist goal of causal inference. Such theorymay be developed and conveyed in a nonmathematicalform (i.e., No bourgeoisie, no democracy) or throughthe use of mathematical operators and proofs. Alongthese lines, the nested analysis approach allows for both

5 Certainly, the nested analysis approach could be described as afolk Bayesian approach (McKeown 2004, 15862) in that it seeksto formally introduce investigator knowledge of the world.

437

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

4/18

Nested Analysis for Comparative Research August 2005

the testing of deductively formed hypotheses and theinductive generation of theory. Many of the benefits ofnested analysis explicitly reston the assessment that theoverall state of theory in cross-national research is rel-atively thin with respect to the questions being asked,and that empirical analysis is required both to develophypotheses and to test them. Of course, the natureof the specific hypothesesincluding the reliance on

microfoundational or macrostructural mechanismsislikely to shape the evidentiary requirements, particu-larly in the SNA (as discussed later). In the remainderof the article, my use of the term modelimplies only ageneral theoretical argument that relates explanatoryto outcome variables, and should not be taken to implya formal model.

The central objective of the remainder of the articleis to specify a set of procedures for integrating LNAsand SNAs. Although it is neither possible nor desirableto identify a cookie-cutter approach to analysis, the sys-tematization of these steps should provide a clear logicfor integrating the two types of analyses and for iden-tifying the types of assumptions and justifications that

are required for analysis. As always, scholarly tastesand subjective judgments about the robustness of theresults influence how the nested analysis will proceed,6

but it is important to ensure a high degree of trans-parency, particularly when adding complexity to thescope of analysis.

I use examples of published and unpublished studiesto demonstrate the use of various techniques withinthe larger approach of nested analysis, but the article isnot intended to be a review of the literature as much asan outline for the execution of nested analysis. Indeed,because almost none of the examples actually employthe specific language or framework developed here,

I only claim that these examples help to clarify howaspects of the approach have been used in particularstudies and with what benefit.

STARTING THE ANALYSIS:PRELIMINARY LNA

Scholars engage new research projects with varyinglevels of background information about a specificcase or set of cases, but the nested analysis formallybegins with a quantitative analysis, or preliminaryLNA. Thus, a prerequisite for carrying out a nestedanalysis is availability of a quantitative dataset, with asufficient number of observations for statistical analy-sis,7 and a baseline theory. The preliminary LNA pro-vides information that should ultimately complementthe findings of the SNA, and that will guide the execu-tion of the SNA. Particularly for scholars who would

6 Indeed, there is no consensus about the robustness of a particular

R2 statistic, or what amount of process-tracing evidence should beconsidered persuasive.7 There is no clear lower bound for the number of cases that canbe analyzed through a statistical analysis, but fewer cases obviouslyreduce the degrees of freedom and intrinsic power of the analysis. Itis rare to see quantitative analyses of fewer than 12 cases in cross-country regression analyses.

have carried out SNA exclusively, the preliminary LNArequires explicit consideration of the universe of casesfor which the theory ought to apply, and identificationof the range of variation on the dependent variable. Italso provides opportunities to generate clear baselineestimates of the strength of the relationship betweenvariables, including estimates of how confident we canbe about those relationships given a set of assumptions

about probabilities and frequencies. When scholars be-gin with strong hypotheses and good data, the prelim-inary LNA can be understood as a more conventionalhypothesis-testing analysis.

The content of the LNA may take one of severalforms, depending on the availability of data, and thenature of the causal modelfor example, dependingon whether the outcome is understood to be gradedor dichotomous, and whether the hypothesized rela-tionship is understood in probabilistic or deterministicterms. One may use multivariate regression analysis;fuzzy set/qualitative comparative analysis (FsQCA);bivariate/correlational analysis, or simply descriptivestatistics to analyze the scores on the dependent vari-

able. Decisions about which brand of analysis to use,and the nature of the modellinear or curvilinear, forexamplemust be made with respect to available dataand theory. In any case, the goal of the preliminaryLNA is to explore as many appropriate, testable hy-potheses as is possible with available theory and data.Indeed, the very feasibility of nested analysis is a prod-uct of the increasing availability of datasets producedby other scholars and international organizations, obvi-ating the need for independent data collection, at leastat this preliminary stage. (Significant independent col-lection of data at this stage can be justified only whena scholar has very strong initial hypotheses and great

confidence in how to measure key variables.) However,it is important to note that the preliminary LNA shouldavoid the insertion of any control variables that do nothave a clear theoretical justification, such as regionaldummy variables. Such variables are likely to soak upsome of the cross-country variance, leaving less to beexplained in the SNA, but in the absence of good the-ory, such controls weigh against the nested approach,which aims to answer the very question of why groupsof countries might vary in systematic ways.

A core strength of LNA relative to SNA is its abilityto simultaneously estimate the effects of rival explana-tions and/or control variables on an outcome of inter-est. To a large extent, SNA in the field of comparative

politics has relied on variants of Mills methods in orderto deal with country-level rival explanationsthat is,scholars identify cases that score similarly on severalkey variables, using shared traits as a basis for ana-lytical equivalence approximating statistical control.8

Although the strategy of identifying cases with rela-tively similar scores on such variables can be a pow-erful one, in a nonexperimental setting, important dif-ferences among cases can almost always be identified,

8 See Gerring 2001 (20914) for a summary of these methods, oftenunderstood as most similar and most different systems researchdesigns.

438

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

5/18

American Political Science Review Vol. 99, No. 3

and these emerge as possible rival explanations. Re-gardless of whether ones causal model is probabilisticor deterministic, some degree of covariance betweena rival explanatory variable and the outcome requiresattention within a SNA based on the juxtaposition ofsimilar cases. One may attempt to draw on theory toargue why a particular variable is an implausible influ-ence, but skeptics are likely to demand empirical proof.

Moreover, one may attempt to carry out within-caseanalysis (Collier 1999) to address rival hypotheses, butagain, there may be no over-time variation or otherrelevant data to analyze; or, one may try to find anadditional similar case with less variation on the of-fending variable, but in a world with a limited numberof highly heterogeneous countries, such options maybe limited. Alternatively, SNA scholars can ignore thecross-case variance or simply concede that there is noway to address the problem with available data. Obvi-ously, these are not ideal solutions.

Depending on the question or the cases under inves-tigation, LNA may be able to lend a hand. Assumingthat the LNA is conducted as a regression, the relevant

dependent variable can be regressed on measures ofthe rival explanatory variable under investigation inorder to assess the strength of a relationship, particu-larly when the SNA provides no solid basis for analysis.For example, in her study of multilateral sanctions, LisaMartin (1992) precedes her analysis of four major casestudies with a set of regression analyses, which allowsher to assess the general plausibility and implausibilityof several possible explanations of why states coop-erate to impose economic sanctions. She argues thatthis technique has allowed us to narrow the rangeof hypotheses deserving more-detailed analysis bysuggesting that some hypotheses . . . have little empir-

ical support (92). For example, she finds no supportfor Keohanes (1984) declining hegemony thesis inthe LNA (91), which allows her to focus her attentionon other possible explanations in the subsequent SNA.In the absence of such LNA, Martin would have beenforced to consider Keohanes (1984) important hypoth-esis in the SNA, imposing analytic costs, and leavingreaders to wonder about the weight of this explanationin the larger sample. Alternatively, if the LNA hadprovided initial support for the Keohane thesis, Martineither would have been forced to accept the usefulnessof that modeland perhaps demonstrate that othercomplementary explanations were possibleor wouldhave been forced to demonstrate in quite convincing

terms within the SNA why statistical relationships werelikely spurious. Clearly the most powerful refutation ofa rival explanation is the presentation of disconfirmingevidence in both LNA and SNA, but given data andanalytic constraints, the ability to rule out a hypothesisin the LNA provides sound justification for focusing onother explanations in the SNA.

At least as important as its ability to dismiss rivalexplanations, LNA provides a unique instrument forassessing the strength of partial explanations or con-trol variables. Because country-level outcomes tend tobe the product of several factors, preliminary LNA islikely to find that some variables are significant predic-

tors of the outcome under investigation, even if theycan account for only a limited portion of the cross-country variance. For example, in a study of the de-velopment of the tax state, Lieberman (2003) beginshis analysis by demonstrating that approximately 40%of the cross-national variation in levels of income taxcollections is predicted by levels of GDP/capita. Al-though this variable is essentially treated as a control

variable throughout the book, it is extremely useful tohave an estimate of the extent to which such a vari-able helps to explain patterns of variation on the out-come. Much small-N research involves the comparisonof similar cases. However, because we only observecases in which there is little to no variation on keycontrol variables, we have little basis for making infer-ences about the need to control on those variables, orabout how strong an influence we should expect thosevariables to have on the outcomes under investigation.The puzzle of a particular case or set of cases can bemade clear when we have some estimate of predictedoutcomes given a set of parameter estimates and thecase scores on those variables.9

ASSESSING THE FINDINGS OF THE LNA:ARE THE RESULTS ROBUSTAND SATISFACTORY?

Beyond providing insights into the range of varia-tion on the dependent variable, and estimates of thestrength of rival hypotheses and controlvariables, LNAalso provides important information about how tocarry out the next stage of the analysisintensive ex-amination of one or more cases. First, the scholar mustassess the findings: did the preliminary LNA providestrong grounds for believing that the initial theoretical

model explained the phenomenon being studied?As noted previously, it is not possible to provideabsolute criteria for answering the question about therobustness of the LNA results because subjective as-sessments about the state of knowledge and what con-stitutes strong evidence weigh heavily.10 Depending onthe nature of the LNA, standard assessments about thestrength of parameter estimates must be used to evalu-ate goodness of fit between the specified model and theempirical data. Nonetheless, one important tool is cen-tral to the nested analysis approach: the actual scoresof the cases should be plotted graphically relative tothe predicted scores from the statistical estimate,11 andwith proper names attached. This provides an oppor-

tunity to make specific assessments of the goodness

9 Although it is true that these initial parameter estimates are likelyto be biased because of model misspecifications, including missingvariable bias, our presumption is that when we do not have a fullyspecified or complete theoretical model, it is useful to gain a senseof what can be explained by the theory and data that are available.10 For a classic statement on the use of common sense and profes-sionaljudgment in theuse of quantitative analysis, seeAchen (1982),especially pp. 2930.11 At the extreme, if no statistical relationship is found between anyof the explanatory variables and the outcome of interest, one couldsimply use a central tendency of the data, such as the mean, as abaseline model, and country cases could be plotted as deviationsfrom the mean.

439

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

6/18

Nested Analysis for Comparative Research August 2005

of model fit with the available cases. In combinationwith the parameter estimates generated from the LNA,the scholar must decide if the unexplained variance islargely the product of random noise, or if there is rea-son to believe that a better model/explanation couldbe formulated. As in any statistical analysis, diagnos-tic plots may highlight suspect patterns of nonrandomvariation in one or more casesthe identification of

outliers. However, unlike in surveys of individuals,where case identities are anonymous and thus irrel-evant for analysis, in the study of nation-states andmany other organization forms, the location of specificcases with respect to the regression line may stronglyinfluence ones satisfaction with the model. For exam-ple, a scholar may feel unsatisfied with a model thatcannot explain a case perceived to be of great signif-icance within the scholarly literature (e.g., the Frenchrevolution in the study of revolutions), or the identi-fication of an outlier case may immediately suggest anew theoretical specification with potentially broaderapplication. If a scholar enters the research project withspecific hunches about seemingly anomalous outcomes,

analysis of the actual-versus-predicted-scores plot maydemonstrate that one or more cases are indeed outliersthat may warrant more theoretical attention. Indeed,Liebermans (2003) study was motivated by a hunchthat differences in the Brazilian and South African taxstructures were striking and not readily explainable,and the preliminary LNA confirmed that this was trueeven when key control variables were taken into ac-count. Of course, such preliminary analysis could haveserved to foreclose unnecessary research by demon-strating that a particular case was (surprisingly) wellexplained by the existing state of theory.

Using such analyses, the scholar must answer the

question: Were all of the most important hypothesestested and were the results robust/satisfactory? Theanswer to this question informs the approach to thenested case analyses, or SNA, as described in the fol-lowing section.

NESTING INTENSIVE CASE STUDIES (SNA)INTO THE ANALYSIS

The second major step of the nested analysis involvesthe intensive analysis of one or more country cases.12

Of course, there is nothing particularly distinctiveabout the simple combination of LNA and SNA; schol-ars have long recognized the value of triangulation

for descriptive and causal inference.13 My contentionis that there are several important strategies that canbe gleaned from assessment of the LNA, which willnarrow the larger menu of options for executing theSNA.14 Moreover, I emphasize that the best use of

12 SNA involves multiple within-case observations, across space,time, and/or otherdimensions.LNA may also involve multiple obser-vations of country cases when cross-sectional data are pooled acrosstime.13 See, for example, Ragin (1987, 6984) for an excellent analysis ofseveral combined approaches.14 Just as there are many styles and strategies for statistical analysis,there are at least as many approaches to SNAan approach that,

SNA is to leverage its distinct complementarities withLNA, not to try to implement it with the exact sameprocedures as one would carry out regression analysis.Although many small-N scholars may have an im-plicit regression model in their head when they carryout their analyses, there are clear benefits to being ex-plicit.15

It is important to recall that the goal of a nested

analysis is ultimately to make inferences about theunit of analysis that is shared between the two typesof analysistypically countries or country-periods. Inpursuing this goal, a nested analysis requires a shiftingof levels of analysis because the SNA component de-mands an examination ofwithin-case processes and/orvariation.16 The SNA should be used to answer thosequestions left open by the LNAeither because therewere insufficient data to assess statistical relationshipsor because the nature of causal order could not be con-fidently inferred. For example, in a hypothetical studyof the determinants of government policy, in whichthe LNA confirmed a hypothesized relationship be-tween institutional form and policy outcome, the SNA

would likely investigate the specific actions of groupsand/or individuals within a given country. This wouldbe done in an attempt to find specific evidence that thepatterns of human organization hypothesized to havebeen influenced by the institutional form were actuallymanifest in reality. Moreover, the SNA is particularlyuseful for investigating the impact of rival explanationsfor which we lack good cross-country data.

The synergistic qualities of LNA and SNA reflect thedifferent types of data that each brings to the analysisof a problem, and their relative strengths in the task ofcausal inference. Here it is extremely useful to highlightthe distinction between a data-set observation, which

corresponds to a row in a rectangular dataset, anda causal-process observation, which is the founda-tion for process-oriented causal inference. (It) providesinformation about mechanism and context (Collier,Brady, and Seawright 2004, 253). We can say that LNAis, by definition, comprised only of dataset observa-tions, whereas the hallmark of SNA is a much smallernumber of dataset observations and a host of causalprocess observations.17 Within-case analysis generallyentails the scrutiny of a heterogeneous set of materials,

almost by necessity, involves lessmethodologicalstructurethan LNAbecause the analysis is strongly oriented toward discovery of novelsocial and political processes that take place in distinctly different

ways acrosstime andspace. In recentyears, there hasbeen increasingmethodological attention to the different types of strategies used byscholars when studying one or a few cases intensively. However,echoing the statements made previously with respect to LNA, thisis not the place to review all of the distinctions about how suchwork is carried out. See, for example, contributions in Mahoneyand Rueschemeyer 2003, Brady and Collier 2004, and George andBennett (2005).15 Thanks to Phil Shively for highlighting this central point.16 See Gerring (2004) for a discussion of within-unit analysis in casestudies.17 The number of rows in a dataset is typically understood as thenumber of country cases, or N, that distinguishes small-N andlarge-N research. By now, most methodologists agree that a small-Nstudy will have many observations, but as Collier, Brady, and Sea-wright (2004) point out, different inferential strategies are used to

440

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

7/18

American Political Science Review Vol. 99, No. 3

including printed documents, interviews, and other ob-servations that provide important information aboutthe social phenomena we seek to understand. Becausesuch materials are produced in such different shapesand forms across time and space, it is often impossibleto specify, a priori, a set of very precise coding rules thatwould allow for an easily repeatable data collection andanalysis process. These materials provide more fine-

grained measurements of a host of events and behav-iors, at both the micro- and macrolevels, and often inclose temporal proximity to one another. Such data arevirtually impossible to capture across large numbers ofcountries in a consistent manner. Scholars gain analyticleverage when they scrutinize the theoretical implica-tions of these observations, either by testing existinghypotheses or by inductively developing new proposi-tions about general relationships between causes andeffects.

Although the distinction between LNA and SNA isgenerally between quantitative and qualitative modesof analysis, some aspects of SNA may involve quantita-tive analyses at different levels of analysis. For example,

one could analyze a survey of individuals for a givencountry if that analysis could shed light on the dynam-ics of the social or political process being studied forthe country at large. Analyses of individual behaviorare specifically relevant to the nested approach onlyto the extent that they shed light on the larger ques-tions being considered in the LNA. In a similar man-ner, the SNA might include time-series analysis (usingcountry-year as the unit of observation) as a way oflinking cause to effect or for dealing with case-specificrival explanations, particularly when the LNA was car-ried out as cross-sectional analysis. For example, inLieberman (2003), time-series analyses of the produc-

tion of government tax collections in the SNA of SouthAfrica helped to rule out the rival explanatory powerof the role of early reliance on mining revenues, whichwould not have been possible in the cross-countryLNA, for which comparable data were not available.

The inclusion of additional theoretically valid casesis always preferred in LNA, but practical constraints oninvestigator skills and time as well as the desirabilityand feasibility of reporting in-depth analyses on mul-tiple cases create important tradeoffs which must beweighed by scholars when selecting cases for the SNA.There is no theoretical benchmark akin to probabilitytheory that small-N scholars can draw on to establishprecise guidelines about what constitutes compelling

evidence. The very nature of causal process obser-vations is that they are highly heterogeneous: somedocumented observations may serve as particularly

interpret such data. It is worth noting that even with these additionalobservations, such research is dubbed small-Na convention that Iuse here. Meanwhile, the proliferation of TSCS analyses of country-level data is widely touted as useful strategies for increasing analyticpower through a larger N (e.g., Beck and Katz 1995), but as Westernand Jackman (1994, 4145) observe, the time-invariant quality ofmany variables considered in cross-country analyses often impliesthat TSCS adds minimal additional analytic leverage for the overallproblem being studied.

powerful smoking gun evidence linking cause to ef-fect, whereas others may simply serve as incrementalsteps that increase the plausibility of a set of theoreticalclaims. Small-N analysis provides the opportunity toimplement various quasi-experimental explorationsby looking at the impact of various shocks or treat-ments within the historical record.18

Particularly if one were to follow the recommenda-

tions of King, Keohane, and Verba (1994) to increasethe number of observations, scholars might incorrectlyconclude that the best strategy for the SNA compo-nent of the nested analysis would be to analyze asmany country cases as possible. On the contrary, sucha strategy tends to lead to a diminution of the corestrengths of the SNA. Increased degrees of freedomare provided by the LNA, and nested analysis shouldrely on the SNA component to provide more depththan breadththat is, given a fixed amount of schol-arly resources, more energy ought to be devoted toidentifying and analyzing causal process observationswithin cases, rather than to providing thinner insightsabout more cases. Because the inherent weakness of

SNA is its inability to assess external validity, there isno point in trying to force it do this when the LNAcomponent of the research design can do that work.Notwithstanding this advice, it will almost always beuseful to evaluate more than one case in the SNA; theelaboration of concepts and mechanisms can best beaccomplished through comparison. A great strengthof small-N analysis is the juxtaposition of both similarand contrasting cases, helping to make transparent theoperationalization of concepts that are largely hiddenin the analysis of a statistical dataset. Furthermore,comparison provides an empirical basis for makingnarrative assessments of counter-factual claimsthat

is, an event would have happened a different way hadthe score on a key variable or set of variables beendifferent (George 1979).

To the extent that scholars increasingly employ vari-ants of nested analysis, standards will need to be estab-lished as to what constitutes an actual case study. Forexample, in studies that report statistical and case studyfindings, Reiter and Stam (2002), and Huth (1996) de-ploy what can be described as mini-case analyses.These help to alert readersto examples of the argumentbeing made by highlighting how well-known cases fitwithin their typologies and the degree to which theyconfirm to theoretical expectations. However, in theseexamples, the use of SNA is rather limited, and so little

additional analytic value is gained. In these studies, thecase analyses provide proper names for the indepen-dent and dependent variable scores, but they do notprovide much elaboration about the alternative waysin which these scores were measured in comparison tothe measurement procedures followed in the large-Ndataset. Moreover, Reiter and Stam and Huth do notproceed with process tracing, linking cause to effectwith any significant narrative. Just as statistical analyses

18 See Campbell and Stanley 1966. I develop a set of strategies forexploring institutional hypotheses in small-N cross-country researchin Lieberman 2001a.

441

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

8/18

Nested Analysis for Comparative Research August 2005

must report on the sample size of the dataset, SNA de-mands full and clear exposition of the array of sourcesconsulted and the depth of the historical analysis con-sidered prior to writing the narrative.19 As the numberof cases in the SNA increases, the individual case anal-yses are likely to become increasingly superficial, andthe distinct advantages of SNA are likely to diminish.

Beyond emphasizing the general complementari-

ties, it is also important to focus the SNA based onthe specific findings and analysis of the LNA. Recall-ing the question posed at the end of the previoussectionnamely, the analysts assessment of the ro-bustness of the preliminary LNASNA will then pro-ceed along one of two tracks. If the answer is yes, theresults were robust, as indicated in Figure 1, then thegoal of the SNA will be almost exclusively focused ontesting the model estimated in the LNA. On the otherhand, if the findings were not deemed to be robust,or if one or more important hypotheses could not beexplored, including if the analyst believes that the ap-propriate theoretical model has not yet been specified,the SNA will be oriented toward model building. As

I detail in the sections that follow, the decision aboutwhetherto proceedwith a model-testing Small-NAnal-ysis (Mt-SNA) or a model-building Small-N Analysis(Mb-SNA) will inform the scope of the analysis, thecase selection strategy, and the analysis-ending criteriafor the SNA. Practitioners may respond that SNA is it-self a mix of model building and model testing and thatthe dichotomy is a false one. Although it is true thatthese may be ideal-type approaches, there is enor-mous benefit to being self-conscious about the centralintention of ones research in the SNA stage, partic-ularly because the nested approach provides distinctsets of guidelines for the respective strategies. Assess-

ment of the preliminary LNA constitutes an importantdecision-point in how the nested approach will be car-ried out (as depicted in Figure 1), providing importantguidelines for an appropriate analytic scope for theSNA.

Model-Testing SNA (Mt-SNA)

When scholars decide they are content with both thespecification and fit of the model specified in the LNA,the main goal of the in-depth component of the nestedresearch design is to further test the robustnessof thosefindings. Given the potential for problems of endo-geneity and poor data in statistical analyses carried out

at the country level of analysis, statistical results alonerarely provide sufficient evidence of the robustness of atheoretical model. Almost inevitably, strong questionsarise about causal order,heterogeneity of cases, andthequality of measurement. SNA provides an importantopportunity to counter such charges. As Achen andSnidal (1989, 16869) point out in an article otherwisequite critical of how such work is often practiced, Case

19 We should not establish as a standard for SNA that a longer nar-rative necessarily implies more careful research and/or analysis. Ourassessment of the findings should be based on the methods used togather and to analyze such data.

studies are an important complement to both theory-building and statistical investigations . . . they allow aclose examination of historical sequences in the searchfor causal processes . . . Comparison of historical casesto theoretical predictions provides a sense of whetherthe theoretical story is compelling.

As the goal is to complement the LNA, the use ofSNA in nested analysis should aim to gain contextu-

ally based evidence that a particular causal model ortheory actually worked in the manner specified bythe model. Can the start, end, and intermediate stepsof the model be used to explain the behavior of real-world actors? Although this recommendation runscounter to the admonitions of Przeworski and Teune(1970), who argue that the ultimate goal should be toeliminate such labels, I believe that the nested analy-sis approach resonates more broadly with the generalgoals and expectations of scholars engaged in com-parative research. That is, not only are we interestedin our ability to make sense of patterns of variation,but also we would also like to use theory to accountfor decidedly important and seemingly anomalous out-

comes in specific times and places. Moreover, unlikein some forms of medical research, where researchersare more likely to be content to find that a cause(say a drug used for minor pain relief) is related toa particular effect (say, better coronary health), evenif they cannot identify the causal pathway of this re-lationship, social scientists are much less likely to becontent with analogous findings. A good social sciencetheory should not merely predict a particular relation-ship between independent and dependent variables,but it should also explain how and why these factorsare related to one another (Gerring 2005), suggestingimplications for what types of events and/or processes

lie between cause and effect. SNA aims to make spe-cific observations between those two points, verifyingthe plausibility of the stated mechanisms in terms ofactions, outcomes, and/or perceptions. The SNA oughtto demonstrate within the logic of a compelling nar-rative that in the absence of a particular cause, itwould have been difficult to imagine the observedoutcome.

In the case of Mt-SNA, scholars can justifiably fo-cus their investigative resources on researching andanalyzing the statistically significant results. The com-bination of theory and statistical results compels us togatherevidencein the form of primaryand secondaryprinted sources, interviews, surveys, and the other types

of materials typically consulted for the development ofan in-depth case analysisthat allows us to write a de-tailed narrative from the vantage-point of the preferredmodel. The evidence required for the SNA dependsupon the nature of the theory. For instance, in a highlystructural argument, actors may not be very aware ofthe circumstances that shape their actions, and so evi-dence of large-scale processes and events will be moreappropriate than in the case of agent-oriented models,in which we would expect evidence of individual-levelcalculations and deliberate action.

While retaining a focus on assessing the plausibilityof the preferred model, Mt-SNA should also aim to

442

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

9/18

American Political Science Review Vol. 99, No. 3

address two types of rival explanations.20 First, if therewere strong hypotheses that could not be consideredin the LNA because of lack of cross-country data, theanalyst should try to assess the strength of the hypoth-esis in the case study or studies. If cause and effectdo not co-vary in the predicted manner, and/or if itis not possible to develop a coherent causal narrativeguided by the rival model, the rival hypothesis can

be dismissed. Second, the scholar should verify thatthe cause preceded the effect. Cross-country statisticaldatabases (used in the LNA) are often highly limitedin terms of temporal scope, and SNA can be used toverify that prior historical factors did not produce theobserved result.

Model-Building SNA (Mb-SNA)

When the state of theory is initially weak or refutedby the LNA and/or the quality of the cross-countrystatistical data is not sufficient to adequately assess thechief hypotheses, the SNA will be called on to do morework. In this instance, the nested analysis approachdemands a more wide-ranging and inductive Mb-SNA.Although scholars may initiate a research project withonly general theoretical hunches, Mb-SNA involvesusing various case materials to develop well-specifiedtheoretical accounts of cross-country variation on theoutcome of interest. Moreover, the Mb-SNA ought tobe used to identify measures that are valid and re-liable indicators of the analytic constructs within thetheoretical model. A clear shortcoming of LNA as it isoften practiced in cross-country research is that manyoff-the-shelf datasets tend to be used, and variablesmay not actually measure what the theory describes.21

Particularly in the instance of Mb-SNA, the investiga-

tors proximity to a wide range of data sources shouldfacilitate the development of valid measures.

As stated at the outset, many scholars may eschewthe goal of identifying broadly generalizable theoriesor covering laws22 and may use the LNA portion of thenested analysis approach simply to point out the limitsof existing data and theory, motivating a more inductivesearch for explanations within a single case or smallset of cases. Others seek more nomothetic findings. Ineither case, the scholar engaged in Mb-SNA does notproceed with the notion that a fully specified model isavailable and must develop explanations for the puzzleof varied outcomes. Although the Mt-SNA approachassumes that the refuted alternative hypotheses were

20 For a fuller discussion of the use of qualitative research to addressrival explanations, see Collier, Brady, and Seawright 2004.21 See, for example, Lieberman 2001b for a discussion of how cross-country taxation data may (or may not) correspond with theoreticalconstructs about the relationships between state and society. Ragin(2000) makes an important point that the scale of country-level in-dicators (e.g., GDP/capita) may not correspond to differences in theunderlying construct (e.g., level of development), and conceptuallysensitive cutpoints and calibrations may be required.22 For a thoughtful challenge to the notion that comparative analysisshould always involve the pursuit of nomological covering laws, seeZuckerman 1997.

adequately tested, the Mb-SNA approach invites re-examination of all theoretically strong propositions tothe extent that data are available.

Inevitably, close-range analysis of one or a few coun-try cases entails making difficult choices about whichmaterials to investigate and which leads to pursue.Nevertheless, in most instances Mb-SNA has severaladvantages compared to SNA carried out in the ab-

sence of a preliminary LNA (i.e., a nonnested design).First, the scholar is equipped with useful, if partial,information about the strength of rival explanationsand control variables. Of course, the reason for thenegative results may be due to the poor quality of thedata in the first place, but at the very least there is someindication about the weakness of relationships. Sec-ond, to the extent that the preliminary LNA providesa reasonable measure of the dependent variable, theMb-SNA can focus on accounting for estimated differ-ences between cases, or between cases andsome centraltendency of the population, having controlled for theeffects of other influences. Third, the nested approachmay induce the analyst to specify clearer concepts

and models than conventional SNA, because eventhe anticipation of analyzing the results with statisti-cal/quantitative tools implies the need for careful delin-eation of cause and effect. In this case, the SNA will becarried out with an eye toward theoretical parsimonyand clarity, which are not always hallmarks of the SNAapproach.

CASE SELECTION STRATEGIES FOR SNA

Nested analysis provides a solution to many of the ten-sions that exist in the current state of methodological

advice about case selection strategies: scholars oftenjustify intensive case study work becauseof a sensethatthey lack sufficient data and analysis of such cases, andyet most case selection strategies require that we justifythat selection at the outset based on what we think weknow about a particular case or set of cases, often inrelation to a broader universe of cases. Nested analysisprovides some assistance for squaring this circle, bydetailing some guidelines for the daunting task of caseselection with respect to the findings of the prelimi-nary LNA. These strategies are useful when a scholarenters a research project without a prior inclination toinvestigate a particular case(s) and/or for assessing theanalytic utility of certain case selection choices when

a scholar already has a predisposition toward thosecases prior to carrying out the preliminary LNA. In-deed, the nested analysis approach can leverage theaccumulation of case-relevant skills and background(including language skills, case familiarity, etc.) whichare important assets for most qualitatively orientedscholars. There is rarely a perfect case selection strat-egy for SNA. Rather, there is a set of options andchoices that, again, may be narrowed significantly bythe LNA. Specifically, we can make informed choicesabout whether to select cases based on predicted andactual scores on the independent or dependent variableand whether or not to select cases randomly.

443

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

10/18

Nested Analysis for Comparative Research August 2005

Selecting Cases Relative to the PreliminaryModel (On- or Off-the-Line)

Perhaps no aspect of the methodological literature oncase selection has left scholars engaged in small-N re-search more confused than the question of whetherto select cases based on values on the independent ordependent variables. Particularly in the area of cross-

national research, scholars have highlighted the pitfallsof selecting a case based on an extreme score on thedependent variable and attempting to infer generalconclusions about the larger universe of cases (Geddes1990). More recently, methodologists have highlighteda wider range of case selection options that will mit-igate such problems, including the explicit accountingof the selection mechanism (King, Keohane, and Verba1994, 12837). More stridently, they recommend thatscholars should select cases based on scores on theexplanatory variablea strategy that does not lead toanalogous pitfalls of selection bias (King, Keohane,and Verba, 1994: 13742)while insisting that suchcases be selected without knowledge of the dependent

variable scores (14246). Unfortunately, this solution,which attempts to replicate the inferential logic of ex-perimental research, is largely impractical. In the firstplace, it assumes very strong theory, which is oftennot the case in cross-national research. In the sec-ond, because qualitatively oriented scholars tend toapproach research questions from the perspective oftrying to understand the determinants of puzzling out-comes, they are almost certain to know the scores onthe outcome variable.

A second issue that comes up is whether we shouldinvestigate cases that are seemingly anomalous or casesthat prove a more general point. Is the role of in-

depth analysis to assess the value of preferred theories,to lead us to new propositions, and/or to gain better in-sights into cases deemed to be of intrinsic interest? Thenested analysis approach provides a strong foundationfor adjudicating among the competing goals and in-ferential logic associated with case selection strategies,asking the scholar to make decisions about case selec-tion in the context of the assessment of the preliminaryLNA, which includes an assessment of confidence inones theoretical model.

When carrying out Mt-SNA, scholars should onlyselect cases for further investigation that are well pre-dicted by the best fitting statistical model. Recall herethat a decision has already been made that cases out-

side the confidence interval are not of theoretical in-terest and should be treated as unexplained noise.Country cases that are on, or close to, the 45-degreeline (plotting actual dependent variable scores againstregression-predicted scores) should be identified aspossible candidates for in-depth analysis. As discussedpreviously, in this instance SNA provides a check forspurious correlation and can help to fine-tune a the-oretical argument by elaborating causal mechanisms.Although intensive investigation of on-the-line casesmay lead to the identification of alternative explana-tions, the primary goal is to assess the strength of aparticular model. As such, there is little value to the

pursuit of cases that are not well predicted by themodel.

Moreover, when carrying out Mt-SNA, one shouldselect cases based on the widest degree of variation onthe independent or explanatory variables that are cen-tral to the model. Because the goal is to demonstratethe robustness of a particular causal argument, the onuson the scholar is to identify process-tracing evidence

from cause to effect. The opposite approachof start-ing with the outcome and working backwardswouldbe much less efficient given the assessment of confi-dence in the original model. By selecting cases withvaried scores on the explanatory variables, the scholarcan use the SNA to demonstrate the nature of thepredicted causal effect associated with the model incontrasting contexts.

Both Swank (2002) and Martin (1992) provide ex-amples of book-length studies in which early chaptersreport statistical analyses that pave the way for Mt-SNA. According to Martin (1992, 92), For those vari-ables that showed statistically significant effects, theanalyses complement the case studies by improving

our confidence in the generalizability of our results.In each case, LNA provides initial confirmations ofthe authors core hypotheses and dismisses several ri-val hypotheses. However, in both cases, the authorsacknowledge that questions about causality arise andthat a range of possible mechanisms could be linkingindependent and dependent variables. As a result, theyboth select cases based on different scores on the cen-tral hypothesized explanatory variables and demon-strate the plausibility of their hypotheses by tracingthe impact of alternative scores on those variables topredicted outcomes in the respective cases. (Graphi-cally, this would be akin to selecting cases such as B, D,

E, and F from Figure 2, in which a range of predictedvalues are considered.) Both scholars are deliberate inthis approach For instance, Martin (1992, 11) writes,This quantitative work allows me to further refinethese hypotheses and provide a framework for the casestudies that follow. Both Swank and Martin reportadditional findings and nuances about the cases theydescribe beyond demonstrating the plausibility of hy-pothesized relationships from the statistical results. Forexample, Swank points out that large-scale variablessuch as international capital mobility (captured inthe LNA) are connected to discrete policy outcomessuch as social expenditure through specific historicalepisodes (presumably distinct from an argument in

which the mechanism is through long-term trends, orslowshifts), such as German unification or Italian polit-ical system restructuring (Swank 2002, 278). Within thecase studies, we observe how actors behave, and we arepresented with a more transparent accounting of causalmechanisms. Compared to an otherwise quite similarstudy such as Garretts (1998) examination of the roleof partisan politics in mediating the pressures of global-ization, whichpresents only statistical findings,Swanksuncovering of cases and mechanisms provides signifi-cant additional evidence and insight. In the absenceof such SNA, we would have been left to imagine themultiple causal pathways possibly associated with the

444

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

11/18

American Political Science Review Vol. 99, No. 3

FIGURE 2. Case Selection from a Hypothetical Regression Analysis

3020100

30

20

10

0

A

BC

D

E

F

G

H

Regression Adjusted Predicted Value

3020100

Actualvalue

ofdependentvariable

0

A

BC

D

E

F

G

H

statistical associations, and with greater skepti-cism about the general robustnessthat is, non-spuriousnessof the results.

On the other hand, a very different set of strategiesfor case selection should be adopted in the case of Mb-SNA. First, at least one case that has not been wellpredicted by the best-fitting statistical model shouldbe selected. Although it may be useful to select addi-tional cases that are on the best-fit line for comparativeanalysis, the assessment that the preliminary statisticalmodel was not sufficiently robust or that there werenot sufficient data available to test certain critical hy-potheses compels the scholar to examine cases thatare not explainable by the right-hand-side variablesincluded in the preliminary LNA. It is important tokeep in mind the distinction between cases that are notwell explained by the model (say, more than 2 standard

deviations from the predicted value) and truly extremecases that are several standard deviations from anyother cases (e.g., case H in Figure 2). In the latterinstance, the extreme nature of the case placementmakes it more likely that the outcome was producedby a different causal process than most of the othercases in the population(and/or that some measurementerror was involved). When such a distribution of casesis presented, case selection will hinge on whether thescholar is more interested in making sense of that de-viance, or of developing a general theory that directlyaccounts for greater numbers of (less extreme) countrycases.

Only when the scholar has good reason to believethat a particular case is on-the-line for entirely spu-rious reasons would it be useful to select such a case

for Mb-SNA. However, in such instances the heuristicvalue of the preliminary LNA becomes increasinglyobscured, and hence, of limited value.

In contrast to the Mt-SNA, case selection in Mb-SNA involves selection of cases based on initial scoreson the dependentvariable. Because Mb-SNA proceedswith vaguer theoretical hunches, the central goal is totry to account for important patterns of variation onthe outcome.23 Although it is important to try to en-sure that among the cases selected there is sufficientvariation on the explanatory variables of greatest in-terest at the outset,this is of secondary concern becausethere is much less confidence at the outset of the SNAthat such variables will be significant when the research

and analysis are complete. The very nature of Mb-SNAimplies that we may lack the scores on the explanatoryvariables of interest at the outset of the project, makingit impossible to use the explanatory variables for caseselection. Although the strategy of selecting on the de-pendent variable has been a potential pitfall for muchsmall-N scholarship, the nested approach provides

23 Certainly, much social science analysis begins with the question,What is the effect of X?, but almost always, there is a clear Y oroutcome in mind. Such instances are examples of strong theory. Itis very rare that a scholar will start with an explanatory variable, butsearch inductively for an outcome to explain.

445

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

12/18

Nested Analysis for Comparative Research August 2005

important correctives: the preliminary LNA providesa framework for selecting cases that vary widely on thevariables of interest, and to the extent that the scholarhopes to draw general conclusions about the applica-tion of the resulting model, nested analysis involvesthe assessment of the hypothesis in subsequent LNA(discussed in the following section). Because causal in-ference in the nested approach does not rely solely on

the small-N portion, the standard pitfalls of selectionbias are less likely to lead to faulty inferences.Using nested analysis, the preliminary LNA can be

used to motivate structured comparisons for SNA, in-cluding a mix of on-the-line and/or off-the-linecases. In the simplest manifestation, when countriesthat would ordinarily be predicted to have similar out-comes wind up with different outcomes, perhaps oneither side of the regression line, and with at least onecase outside the confidence interval, scholars are pre-sented with useful analytic puzzles that merit furtherexamination (e.g., cases A, D, and C in Figure 2). Alongthese lines, the useof thenested approach could help toexpand the scope of structured focused comparisons.

Although there is a long tradition of deploying variantsof Mills method of difference to gain analytic lever-age in cross-national comparative analysis, the require-ment of identifying similar cases tends to limit schol-ars to comparing cases within regions, forcing certainsets of comparisons to reemerge: France/Germany,U.S./Canada, Brazil/Argentina, and so forth. Toa large extent, the underlying logic of such compar-isons requires that the scholar make the implausibleargument that the two or more countries are virtuallyidentical in every way except on the relevant indepen-dent and dependent variables. As typically practiced(i.e., in the absence of LNA), the method virtually

precludes making comparisons of countries at differ-ent levels of economic development, because that fac-tor is assumed to have a causal influence on mostoutcomes of interest to Political Scientists. For exam-ple, comparisons between the United States and Indiamight ordinarily be dismissed as not particularly usefulbecause of vast differences in levels of economic devel-opment. However, within a nested analysis, one mightfind in the preliminary LNA that indicators of devel-opment do not hold any explanatory weight for theoutcome of interest, and that colonial legacy (Anglo inboth cases) and state structure (federal in both cases)are important predictors of the outcome, leading tosimilar point estimates and compelling a focused analy-

sis of the two countries. Alternatively, in a strategy thatapproximates Mills method of agreement, one mightselect cases with differing regression predicted values,and attempt to explain similarities in outcomes (e.g.,cases B and G). In either case, LNA can set the stagefor a comparative analysis that might otherwise seemimplausible. The juxtaposition of such country casesallows for the additional exploration of the role of rivalhypotheses that might not have been considered in theLNA because of lack of theory or data.

The nested analysis approach provides a self-conscious strategy for what many case-oriented schol-ars already do in practice: begin a research problem

with an intuition that a particular case defies conven-tional wisdom or theorizing about a particular phe-nomenon, and then proceed inductively to generateexplanations and theories that account for that excep-tionalism. When using nested analysis, a potentiallyimportant finding of the preliminary LNA is that vari-ables ordinarily thought to be associated with the out-come turn out to be statistically unrelated in the large

sample. Alternatively, if the preliminary LNA demon-strates that the case was well predicted by conventionalvariables, this would give good reason to rethink theintuition of the cases uniqueness. If the LNA confirmsthe cases outlier status, however, this provides strong

justification for intensive study.As an example of such a move, Coppedge (2005)

motivates the question of patterns of regime changeover-time in Venezuela through various engagementswith theory and preliminary LNA.24 On the one hand,he demonstrates that on its own, a variable measuringover-time changes in level of economic developmentdoes a relatively good job of predicting democraticbreakdown in that case. On the other hand, the in-

clusion of other factors helps to provide a better fittingmodel of regime outcomes more generally (across alarge sample of approximately 4,000 country-years),and such a model does not predict the observed over-time changes in Venezuelas political regime. From thisperspective, the need for the case study is clear: existingwisdom on the subject could notaccount for an impor-tant political outcome, and there is room for a newhypothesis or set of hypotheses to help address thisconundrum. To accomplish this, Coppedge engages inan inductive Mb-SNA. (Incidentally, it is important tonote that when using pooled time-series cross-sectiondata, the country is still the unit about which one

tries to make inferences, but the inclusion of historicaldata implies an interest in accounting for dynamics orhistorical patterns that describe each country, in thecontext of time-varying parameters.)

Selecting Cases Randomly or Deliberately

Scholars using nested analysis also face choices aboutwhether theselection of cases should be done randomlyor deliberately (nonrandomly). Again, the best strat-egy depends largely on the goals of the SNA and alsoon scholarly tastes and the scholars familiarity with

24 My definition and label of the nested approach are somewhatdifferent from Coppedges (2005). He explains, Nested inductionconsists of a case study nested within a large-sample quantitativeanalysis. This method has three steps: 1) explaining the case of inter-est as much as possible using large-sample empirical estimates of theimpact of general explanatory factors; 2) using the large-N estimatesto pinpoint what is not well explained by the general factors (theresiduals), and 3) using traditional case-study methods to proposesupplementary explanations for the residuals (1). My approach ismore expansive, incorporating a wider variety of research problemsand results. Moreover, I opt for the label nested analysis insteadof his nested induction because I see no reason to limit this formof research necessarily to inductive theory-building. Although caseanalysis almost inevitably demands induction, there is no reasonthat this approach could not be used to examine deductively derivedpropositions.

446

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

13/18

American Political Science Review Vol. 99, No. 3

and access to certain case materials. In most cases, de-liberate selection will be the most appropriate strategy,but there may be specific instances when, in the courseof carrying out Mt-SNA, random case selection canbe used to address specific concerns about investigatorbias. In any event, explicit consideration of this optionforces us to reflect on potential sources of bias and mea-surement error in SNA, which should be considered in

all aspects of the nested analysis.Though rarely used in practice, when carrying outMt-SNA, it may be desirable and appropriate to use arandom case selection strategy. In a work-in-progress,James Fearon and David Laitin (2005) elect to furthertest their statistical model (2003) with narrative anal-yses of a set of randomly selected cases.25 Fearon andLaitin (2005) opt for this approach, arguing that thedeliberate selection of cases risks high levels of inves-tigator bias. In particular, they say that the random se-lection of cases can provide an opportunity for a freshreading from the standard literature about a country.Moreover, they are concerned that in-depth investiga-tion of cases they know well will induce confirmation

of theories based on the very informationthat was usedto derive the theory in the first place. Importantly, therationale for random selection is not the developmentof a representative sample, as is the case in other formsof research, including survey research. The number ofcases involved is simply too small to generate a use-ful representation of the entire population of countrycases.

There are strengths and weaknesses associated withthe random case selection option. On the one hand,there is good reason to believe that this strategyshouldlead to less investigator biasHowever, it is only ap-propriate when the model specified in the LNA pro-

vides a good fit and when the investigator is less inter-ested in identifying new hypotheses than in assessingthe degree to which the logic of the theory behindthe statistical model actually resonates with causes andeffects within particular case histories. If a scholar canactually apply a model to a countrywithwhich he or shehad little initial familiarity, confirm the independentand dependent variable scores with new measures, andfind theoretically predicted links between cause andeffect, such findings would provide considerable con-firmation of the robustness of the model. As Fearonand Laitin (2005) suggest, a good strategy is to stratifycases based on independent and dependent variablescores in order to ensure a wide range of variation in

case scores while attempting to economize on the totalnumber of case studies carried out.

Despite certain appeal in the reduction of bias as-sociated with random selection, the promised benefitsmust be weighed against pragmatic investigator lim-itations. The very rationale of this strategy commitsscholars to cases where they may lack the technicalskills for careful readings of country data, and mostly, ifnot exclusively, to secondary sources that may already

25 However, they do not limit themselves to the selection of well-predicted cases.

be heavily biased by a particular theoretical bent.26

This strategy may be particularly problematic whenscholars carry out research in issue areas for which acomplete secondary literature does not exist (in thecase of Fearon and Laitin (2005), their focus on civilwars implies that this concern does not hold), requiringscholars to probe deeply into primary materials in or-der to carry out the analysis. One solution would be to

enlist country experts to collaborate on country-basedresearch generated from random selection and to askthem to adjudicate among best-fitting models (whilebeing blind to the preferred model). This is an idealstrategy from a methodological standpoint if such anopportunity is available and appeals to ones scholarlystyle, but it also imposes high research costs.

Although the random selection approach is an in-triguing option, most scholars will likely opt for a delib-erate, or nonrandom,approach to the selection of cases.Particularly because problems of selection bias do notapply in the LNA component of the nested analysisresearch design, minimization of this bias in the SNAcomponent is not likely to justify the costs associatedwith random case selection. Indeed, as stated at the out-set,many scholars areinterested to see whether generaltheories can help to make sense of particular cases anddo not view case analysis as merely a means for assess-ing general theories. When selecting cases deliberately,the standard benefits of SNA are much more likely toapply, including the ability of the scholar to gain accessto (often highly heterogeneous) data and to sensitivelyanalyze such data with an appropriate degree of con-textual background to make valid comparisons acrosscases. For example, evidence of the harsh exchange ofwords in various legislative contexts is likely to havevery different implications for how we interpret the

degree of cohesion or polarization across polities, de-pending on the norms of parliamentary debate. Or, inthecase of racial/ethnic politics, thecoding of bigotedlanguage and the subtle ways in which discriminatorypractices get carried out may only be apparent to aseasoned analyst. Valuable field research, the qualityof which is greatly enhanced through language skills,is more likely to be endeavored if country cases aredeliberately selected.

Indeed, when engaged in Mb-SNA, random selec-tion of cases should absolutely be avoided becausesuch an approach would be tantamount to saying, Idont have a good theory, and I dont have an intuitionabout why a particular case would be illuminating forconstructing a theory, which is hardly a solid founda-tion for investigation. Of course, many scholars whofind themselves engaged in Mb-SNA will arrive at thisform of analysis because, as discussed in the previouslycited examples, they had already identified cases ofpotential theoretical interest. Alternatively, such caseswill be selected because a scholar believes that he orshe has a particular expertise, such as language skills,

26 For example, see Lustick (1996) for a discussion of the problemsof bias in secondary sources in political science research. For a moregeneral discussion of the problem of random selection in SNA, seeKing, Keohane, and Verba (1994, 12528).

447

-

8/2/2019 Lieberman Nested (1)

14/18

Nested Analysis for Comparative Research August 2005

background, or historical knowledge, or because of aparticular interest in a case.

When a scholar is intent on studying a particular caseor set of cases, the nested analysis approach obviatesthe need to make the artificial claim that the case is thebest one for studying a particular research question.Rather, the approach allows the scholar to identify theparticular information that he or she wants to glean