LEONARD BERNSTEIN Overture to Candide...

Transcript of LEONARD BERNSTEIN Overture to Candide...

30 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ www.rvsymphony.org

Program Notes By Ed Wight

LEONARD BERNSTEIN Overture to Candide (1956)

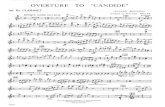

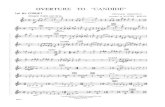

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 4 clarinets (including E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, tenor drum, triangle, glockenspiel, xylophone, harp, and strings

Duration: about 5 minutes

What could be more appropriate for the festive opening of a new season than a celebration? 2018 provides the opportunity to

honor the Centennial of America’s most celebrated musician – Leon-ard Bernstein.

As a gifted pianist, he could have easily pursued a career as virtu-oso soloist. Instead, he burst onto the national scene as a last-minute substitute for conductor Bruno Walter in 1943 – and never looked back. He became the first American to conduct at La Scala, the first American-born principal conductor of the New York Philharmonic, and prominently helped revive Mahler’s music. Bernstein also made lasting contributions as a composer in both classical genres (three

Tickets 541-708-6400 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ 31

symphonies, an opera, the Mass, the Concerto for Orchestra) and Broadway (On the Town, Candide, West Side Story). The 2001 New Grove Dictionary states “as composer, conductor, pianist, and peda-gogue…He was the most famous and successful native-born figure in the history of American classical music.”

When he turned to the comic operetta Candide, Bernstein already enjoyed extensive theater experience. He’d written the ballet Fancy Free, the opera Trouble in Tahiti, and the musicals On the Town and Wonderful Town. Yet Candide became Bernstein’s ‘Fidelio’ – after a dis-appointing 2-month run on Broadway, he revised it often over the next two decades. Lillian Hellman had the original idea for this musi-cal version of Voltaire’s 1759 satire, and many hands contributed to the subsequent revisions.

The overture includes three prominent themes from the operetta. And perhaps only Bernstein could write a Broadway overture in a variant of classical music’s most sophisticated structure: sonata form. After the opening fanfare, Bernstein turns to the ‘Battle Music’ for the primary theme. A challenging and rhythmically complex transi-tion in the woodwinds leads to the rich and lyrical secondary theme for the strings (the love duet ‘Oh Happy We’). After new scoring for the recap, the coda turns to Bernstein’s send-up of coloratura style ‘Glitter and be Gay.’ Despite the vicissitudes of the operetta, critic Jeff Midkiff writes “the Overture was a hit, and swiftly became one of the most popular of all concert curtain-raisers.”

ROBERT SCHUMANNPiano Concerto in A minor, op. 54 (1845)

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings

Duration: about 31 minutes

By the time Robert Schumann turned to orchestral writing in 1841, his musical accomplishments were already extraordinary.

Throughout the 1830s, he “created a revolutionary new form of pia-no music” (musicologist Charles Rosen). While sets of brief character pieces for piano already existed, Schumann’s collections “were not just heard as individual numbers, but [also] formed a whole…Each set had something like a narrative structure” (Davidsbundlertanze, Op. 6 and Carnaval, Op. 9, etc.). Then in 1840, he wrote “the only song

32 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ www.rvsymphony.org

cycles that truly rival Schubert’s in stature and frequency of performance” (music historian Richard Taruskin). He made the piano and voice equal in importance, and his most striking innovation was the oc-casional long postlude in the piano, some-times incorporating entirely new material” (Rosen). Schumann’s songs also expand-ed the range of musical depictions “far beyond any of his predecessors, with effects of irony, sarcasm, ecstasy and desperation.”

Furthermore, he also founded the music journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in 1834 and “Schumann’s contribution to music criticism is immense” (Leon Botstein). His judgments of composers and music were often prescient, as Schumann’s “first and last published writings hailed the advent of young and still unrecognized geniuses, Chopin and Brahms” (Gerald Abraham). In addition, Schumann became the most prominent early critic of the virtuoso concertos – “empty of con-tent” — that dominated the genre by the 1830s. Thus his Fantasie for piano and orchestra of 1841, which became the first movement of his piano concerto four years later, primarily avoided virtuosic display. (Nonetheless, perhaps only Franz Liszt could consider this challeng-ing work a ‘concerto without piano.’)

Schumann also transformed the concerto genre, creating “a land-mark in Romantic music” in the process (Alan Walker). The orchestra and soloist share an unusual quantity of thematic material, and early audiences were struck by the amount of piano and orchestral dialogue. That begins with the tender opening theme which dominates the con-certo to an unprecedented degree. The first phrase is stated with a woodwind choir before the piano completes it. Schumann maintains this unusual chamber music aura throughout much of the concerto, with full orchestral outbursts being few and far between. Every major section of the 1st-movement Sonata-form concerto structure chang-es tempo (and often meter as well) as it presents fresh variants of the lyrical, song-like primary theme — reinforcing the ‘Fantasy’ aspect. Even the cadenza is transformed, featuring much new material.

Tickets 541-708-6400 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ 33

He fashions a gentle second-movement Intermezzo, set in A B A form. Schumann bases the rising motive of the opening solo-orches-tral dialogue on the second bar of the 1st movement’s primary theme. Then a lovely cello theme dominates the middle section. The Inter-mezzo leads without a break into a lively and spacious Sonata-form fi-nale – also based on aspects of that primary theme. Schumann offers a march-like variant of it as the opening theme. And purists might spot some virtuoso passages here after all, whose brilliance serves to balance the gentle lyricism of the earlier movements.

Music historian Donald Tovey wrote that the concerto “attains a beauty and depth quite transcendent of any mere prettiness.” This glorious and “unique” (Botstein) concerto soon became one of Schumann’s most popular works. It thus provides yet another exam-ple of Schumann making “significant contributions to all the musical genres of his day” (New Grove). Reinhard Kapp writes that “After Mendelssohn’s death, he can be reckoned a national institution…Schumann’s standing as the leading representative of ‘pure’ music, the heir of Beethoven, was unchallenged for some time to come.”

ZOLTÁN KODÁLY Háry János Suite (1927)

Instrumentation: 3 flutes (all doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (first doubling E-flat clarinet and second doubling alto saxophone), 2 bas-soons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 cornets, 3 trombones, tuba, cimba-lom (played here on harpsichord), timpani, xylophone, tambourine, chimes, glockenspiel, snare drum, trian-gle, cymbals, bass drum, tamtam, celesta, piano, and strings

Duration: about 25 minutes

The musical culture in 19th-century Hungary was not ideal. “Many gift-

ed native musicians emigrated in their childhood or youth (Liszt, Joachim, Ni-kisch, etc.) because of inadequate train-ing and limited opportunity” (2001 New Grove Dictionary). Even the founding of the Academy of Music at Budapest in 1875 initially produced little emphasis on

34 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ www.rvsymphony.org

Hungarian music, because the composition department favored German and neo-Wagnerian style. No single individual did more to change this situation than Zoltán Kodály.

Kodály and Béla Bartók started collecting Hungarian folksongs (“ancient peasant melodies that had survived practically unchanged in Hungarian villages”) on a systematic basis in 1905. These differed from the 19th century Hungarian popular songs (such as Liszt’s ‘Hun-garian Rhapsodies’) which had previously, and erroneously, been con-sidered folksongs. While Bartók ranged farther afield, this folk style influenced Kodály in his works of 20th century Hungarian art music. Besides his compositions and folk music research, he was also a suc-cessful music educator. “In the 1920s and 30s, the ‘Kodály Method’ became the progressive opposition to the pro-German musical culture that flourished between the wars” (New Grove).

The main musical objective of the singspiel (light opera) Háry János, written in 1926 “was to bring genuine folksong to the operatic stage” (New Grove Opera Dictionary). Háry János was an actual foot soldier in the Napoleonic wars, then returned home to be a successful

Tickets 541-708-6400 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ 35

potter and regale his companions with fictional, Quixote-like escapades as a military hero. While this comic operetta based on those tales still holds the stage in Hungarian houses, the suite Kodály derived from it (on Bartók’s recommendation) won immediate international acclaim.

The suite is honeycombed with Hungarian elements. The first movement opens with a dramatic rising glissando in most parts — an ‘orchestral sneeze,’ a sign in Hungarian culture that what follows al-most certainly isn’t true.

In the 2nd movement (‘Viennese Musical Clock’), Napoleon’s wife Marie Louise has fallen in love with Háry, and they travel to Vienna with Orsze — Háry’s fiancée. The consistent, balanced regularity of the melodic phrasing reflects the mechanical precision of the clock.

In contrast, the 3rd movement features the wonderfully irregular, unpredictable phrasing of an authentic Hungarian folksong (first in the viola, followed by a lovely version for oboe and strings). The solo cimbalom, a special hammered dulcimer-like instrument invented in Budapest in the 1870s, provides further echoes of home (played on harpsichord this weekend).

The fourth movement depicts the military battle between Napoleon’s army and the Hungarian forces led by (General) Háry, who defeats them. A march written as a brass fanfare evokes the military scene, until it is mocked by the saxophone (remember the sneeze!). That satiric saxophone returns for the funeral march of the retreating Napoleon.

Kodály sets the following Intermezzo in A B A form. The opening theme employs a minor-mode song from Istvan Gati’s 1802 piano method book. The solo French Horn begins a softer, major-mode cen-tral section on a melody from a collection of Hungarian dances in the 1820s. And the continuous 16th-note passages for the cimbalom (harpsichord) evoke the Style Hongrois, of Hungarian Gypsy music.

For the celebration of ‘The Emperor and his Court’ finale, Kodály writes a joyous march. He bases the first contrasting episode, begun by a brief brass choir, on yet another folksong. In this festive Rondo movement, the opening theme returns periodically, and in full orches-tral splendor to close the suite.