Leadership Skills for Board Members - Bristol … Skills for Board Members comprises the...

Transcript of Leadership Skills for Board Members - Bristol … Skills for Board Members comprises the...

Leadership Skills for Board Members

G O V E R N A N C E

A Guidebook for Board Members of Community Development Organizations

Launched in 1982 by Jim and Patty Ro u s e ,

The Enterprise Foundation is a national,

nonprofit housing and community d e ve l o p-

ment organization dedicated to bringing lasting

i m p rove m e n t s to distressed communities.

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT LIBRARY™This book is part of the Enterprise CommunityDevelopment Library, an i n valuable re f e rence collectionfor nonprofit organizations dedicated to revitalizing andreconnecting neighborhoods to mainstream America.One of many resources available t h rough Enterprise, itoffers industry - p roven information in simple, easy-to-read formats. From planning to governance, fund rais-ing to money management, and program operations tocommunications, the Community De ve l o p m e n tL i b r a ry will help your organization succeed.

ADDITIONAL ENTERPRISE RESOURCESThe Enterprise Foundation provides nonprofit organizations with expert consultation and training as well as an extensive collection of print and onlinetools. For more information, please visit our Web siteat www.enterprisefoundation.org.

Copyright 1999, The Enterprise Foundation, Inc.All rights reserved.ISBN: 0-942901-27-4

No content from this publication may be reproduced ortransmitted in any form or by any means, electronic ormechanical, including photocopying, recording or any infor-mation storage and retrieval system, without permissionfrom the Communications department of The EnterpriseFoundation. However, you may photocopy any worksheets or sample pages that may be contained in this manual.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authori-tative information on the subject covered. It is sold with theunderstanding that The Enterprise Foundation is not render-ing legal, accounting or other project-specific advice. Forexpert assistance, contact a competent professional.

Table of Contents

Introduction 2

Organizational Ownership 3

Board Leadership Roles 4

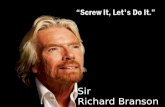

What Makes an Effective Leader? 6

Leadership Skills 7

Conduct meetings 7

Build participation 7

Gather and communicate information 8

Evaluate and assess progress 8

Resolve conflict 9

Manage the problem-solving, decision-making process 11

Group Dynamics 13

Leading Through Difficult Times 17

Leaving a Legacy 21

1

About This Manual

What are leadership skills for board members?

Leadership Skills for Board Members comprises the fundamen-tal traits, roles and skills necessary for building strong, effectiveleadership within nonprofit community development organiza-tions. Board leadership keeps an organization healthy and on track, and it provides the best defense when times are rough.

Leadership Skills for Board Me m b e r sis designed for board members of nonprofit community development organizations who want tobecome more effective leaders within their organization. The infor-mation in this manual can help you establish a good leadershipp rocess or improve how your organization is currently governed. It covers topics such as:

■ Leadership positions on boards

■ Five traits of effective leaders

■ Conflict resolution

■ Problem-solving management

■ Troublesome personalities

■ Preparing in advance for difficult times

This manual is one of the books within the Governanceseries of The Enterprise Foundation’s Community Development Library™. The series provides detailed information on:

■ Understanding board basics

■ Building and managing a better board

■ Evaluating the organization

■ Evaluating the executive director

Leadership comes in different forms and can befound throughout any healthy organization. Ind i recting and guiding others, leaders steer theg roup tow a rd a common goal. Leading theb o a rd of a nonprofit organization means guidingb o a rd members in their work of achieving theo r g a n i z a t i o n’s mission, its charitable purpose.

Rather than presenting abstract theories aboutl e a d e r s h i p, this manual focuses on leadershipskills as they relate to the board chair (alsocalled the board president), board officersa n d committee chairs.

DIFFERING BOARD COMPOSITIONS

People are asked to serve on boards because theyhave something important to contribute. Theyserve without pay because they believe in theorganization’s cause. Board members (also calledtrustees) tend to be thoughtful, motivated anddedicated people — and people with minds oftheir own.

The boards of community development organi-zations are often more diverse in their profes-sional backgrounds, previous board service,technical expertise, and racial and ethnic com-position than other nonprofit boards may be.Turning this collection of capable individualsinto a single intelligent, productive and unifiedentity takes effective leadership, especially onthe part of the board chair.

Leadership Skills for Board Me m b e r soffers practi-cal ideas to help you do just that. Written primar-ily for board members, this manual is designed tobe a practical guide, offering specifics on how toestablish solid board operations and manage theinevitable drama that unfolds when more thanone person must make difficult decisions.

At times, this manual tells you what to do andrelies on you, as organizational leaders, to decidehow. That’s because we assume you already havewhat it takes to lead. Leadership Skills for BoardMembersis not a primer on leadership, butinstead offers insights for those who lead a com-munity development organization. It points outissues that other boards may take for granted —the kind that may mean the difference betweensuccess and failure for your organization.

2

Introduction

The board, as the legal owner of the nonprofitcommunity development organization, plays arole much like that of a parent; ultimate respon-sibility for the organization rests with it. Thismeans trustees cannot be passive observers anymore than parents can afford to let a 3-year-oldplay in the street. Both amount to negligenceand can lead to danger.

It is an unfortunate fact that some volunteerboard members are negligent in this way, butmost often their neglect is unintentional. Manyare recruited and installed without knowingtheir obligations and responsibilities. They siton the board for months, even years, withoutassuming real ownership. They never under-stand that the organization’s life is in theirhands, that responsibility for its survival, itssuccess, lies with them.

Before a volunteer board can consistently act inthe best interest of its organization, its trusteesmust understand and accept responsibility forthe organization’s success or failure — obtainingthe needed resources, protecting organizationalassets, implementing sound policies and beingaccountable to outside stakeholders.

To ensure that members understand their duty,they should participate in a detailed orientationdescribing legal and other obligations that comewith board service. Providing each potentialb o a rd member with a re c ruitment packet spellingout the expected commitment of time, skill andother re s o u rces will give those who cannot com-mit an opportunity to eliminate themselves fro mconsideration. The result will be a group oft rustees who know and accept the re s p o n s i b i l i t i e sof ow n e r s h i p.

3

Organizational Ownership

Typically, board operations are led by peoplewho fill these positions:

■ The chair, or president, of the board

■ Board officers

■ Committee chairs

THE BOARD CHAIR OR PRESIDENT

The highest leadership position in a nonpro f i torganization is the board’s chief volunteer officer,usually re f e r red to as the chair or the pre s i d e n t .For simplicity, this manual uses the term chair.

The chair provides overall leadership by govern-ing the board of directors, which in turn gov-erns the organization. With this leadership rolecomes power and authority, usually expressedthrough persuasion rather than command. Thechair assumes the greatest responsibility for theorganization’s operations and finances, and thusits overall well-being and success.

An important function of the board’s chief vol-unteer is to guide the group in developing poli-cies that shape the organization’s future. Thechair must be able to envision how the board,its committees, the executive director and staffshould function and work together to achievethe agency’s mission. The art of board leadershipis bringing these elements together to form astrong, productive partnership.

BOARD OFFICERS

Officers are responsible for the board’s internala d m i n i s t r a t i ve functions, having been electedby the board according to the bylaws or operat-ing policies. Ty p i c a l l y, volunteer boards includea board chair, a vice chair, a tre a s u rer and as e c re t a ry. (Some states re q u i re a minimum oft h ree officers — a chief officer, a tre a s u re ra n d a s e c re t a ry — through their nonpro f i tcorporation laws.)

The chair is the leader of the board and theorganization it serves. The vice chair replacesthe chair in that person’s absence. The secretaryrecords the minutes, safeguards all corporaterecords and ensures that the organization’s legalfilings are complete and accurate. The treasurerplays the very crucial role of financial overseer.An organization may have additional officers,but these four are the minimum for soundboard operations, even if one trustee holdsmore than one post.

4

Board Leadership Roles

THE COMMITTEE CHAIR

Except for very new or very small boards, mostboards work through committees. Their smallersize allows members to work together more effi-ciently. As a subset of the board, each commit-tee has a defined purpose. Some committees,such as the executive committee, exist as longas the board exists and are called standing com-mittees.Others, such as a merger committee,exist for a specific short-term purpose and arecalled ad hoc committees.

The bylaws or board operating policies shouldspell out the details of committee appointments.A committee member may be appointed by thec h a i r, elected by the board or automatically desig-nated to a committee by virtue of his position asa board officer. For example, the board tre a s u re rmay automatically be the finance committeechair or the vice chair may head the nominatingcommittee. Most committee members are alsob o a rd members, but nonboard committee mem-bers can add expertise without creating anunwieldy governing board.

Because committees do the work of the board,committee chairs must have strong leadershipskills. They must develop work plans and movecommittee members steadily toward their com-pletion. Like the board chair, the committeechair must guide the committee through diffi-cult decisions and must sometimes settle inter-personal conflicts.

The mark of a successful committee is that itadds value to the board by saving time ande n e r g y. It mobilizes the expertise needed toa c h i e ve the organization’s mission. The marko f a successful chair is a pro d u c t i ve committee,and a successful committee chair is often agood candidate for board chair.

5

A board’s effectiveness depends largely on thecapabilities of its individual trustees, so pro-spective members should be chosen carefully.Selecting good leaders is not an exact science,but there are some key qualities to look for, interms of both personal characteristics and skill.

LEADERSHIP TRAITS

Effective leaders share many of the same per-sonal characteristics. Some — like charisma —are difficult to define and even harder to teach.Other traits are easier to observe, and boardmembers who exhibit them may be ideal candi-dates for positions of leadership. Look fortrustees who are:

■ Mission focused

■ Visionary

■ Motivating and inspirational

■ Analytical

■ Objective

One way to determine if these traits arepresent is to give trustees one-time leadershipassignments and watch for these qualities toshow themselves.

Mission Focused

The effective leader keeps the organizationfocused on its primary goals. This person is con-stantly asking the board the right questions: “Iswhat we are doing helping us fulfill our mis-sion?” “Does each decision, each action, moveus toward our goals?” The leader constantlycommunicates the organization’s mission, bothinternally and externally, and keeps the boardand the staff on target.

V i s i o n a r y

A leader envisions the organization’s present ro l e ,as well as its role in the future. For communityd e velopment organizations especially, an effectiveleader envisions what the community’s future canbe and how the organization can help achievethat vision. The leader visualizes this potentialby understanding the “big picture,” for both theorganization and the community it s e rve s .

Motivating and Inspirational

The leader must activate others, not only to par-ticipate on the board and be interested in themission, but also inspire them to commit theirtime, energy and other re s o u rces. A leader shouldlook for and highlight eve ry tru s t e e’s contribu-tions and the value they add to the mission of theorganization. Volunteer board members need tok n ow they are appreciated, and each needs moti-vation to give of their particular gifts — whetherit is their expertise, time, contacts or finances.

A n a l y t i c a l

Leaders must direct the board’s attention to howthe organization can benefit from new opportu-nities or avoid possible pitfalls and then helptrustees weigh their choices. They lead the wayby asking searching questions: “What will wegain if we take this opportunity? What will welose if we pass it up?” “How can we avert thispotential crisis?” They welcome — even encour-age — opportunities to discuss the pros andcons, recognizing that hard choices ofteninvolve considerable risk.

O b j e c t i v e

A leader — especially the board chair — mustbe objective and impartial. This person musthave an open mind in all discussions and a will-ingness to listen to sometimes intensely differentviewpoints. The chair should be able to expressboth sides of a debate to help the board reachan informed decision.

6

What Makes an Effective Leader?

Leadership skills complement the strong per-sonal traits of good leaders, whether they areleading the board or a committee. Unlike per-sonal characteristics, skills can be learned andsharpened through education and experience.An effective board leader should be able to:

■ Conduct meetings

■ Build participation

■ Gather and communicate information

■ Evaluate and assess progress

■ Resolve conflict

■ Manage the problem-solving, decision-making process

The last two skills are covered in moredetail because they address issues that can beparticularly challenging for less experiencedboard leaders.

CONDUCT MEETINGS

Leaders should be skilled in planning andconducting meetings. What does it mean toconduct a well-run meeting? Here are someimportant steps:

■ Develop a well-thought-out agenda clearlyidentifying issues to be discussed and actionsto be taken; be sure everyone has an advancecopy.

■ Begin each meeting by stating its purpose (andperhaps how it relates to the board’s or com-mittee’s larger goals), and end by summarizinghow this purpose was accomplished.

■ Encourage and facilitate participation bycommittee members.

■ Keep the group focused on its task andtime frame.

■ If tasks are assigned, secure that person’scommitment to complete the task by itsdeadline and press for follow-through.

BUILD PARTICIPATION

Trustee participation is essential to meaningfulboard discussions and decision making.Effective board leaders learn to build and sustaina high level of participation, at both the boardlevel and the committee level. Those who leadthe board and its committees can use severaltechniques to encourage sustained participation:

■ En s u re that all trustees have agendas and sup-p o rting materials several days before themeeting. This is crucial for meetings wheremembers discuss and vote on policy issues.W h e n e ver possible, alert them to the issuesthat may re q u i re hard decisions so they havetime to pre p a re for the d i s c u s s i o n .

■ Establish and enforce communication proto-cols — standard rules of order that ensureorderly, courteous conversation during meet-ings. But just as important, send the messagethat the board wants to hear from all trustees,no matter what their point of view. Ridicule,dismissal and interruption should never be tol-erated. After all, it takes only one embarrassingexperience to warn others not to say toomuch.

■ Ask for help or advice. Board leaders do notk n ow it all and should assume that the board(or committee) as a team is smarter than eachindividual member. Let the trustees know theircontributions enrich the work of the board .

7

Leadership Skills

GATHER AND COMMUNICATE INFORMATION

Information is a critical business tool, andthe effective leader must learn to use it well.Information processing is the essence of mostboard and committee assignments. Committees,which do the work for the board, typicallysearch for information, distill and analyze it,and make recommendations to the board forofficial action.

The committee chair must first be able to iden-tify the kinds of information the committeeshould gather. For example, the resource devel-opment committee might research fund-raisingstrategies with high yields and low costs. Thenominating committee may gather the namesof experienced professionals and motivatedcommunity residents as potential nominationsto the board. The real estate development com-mittee might research projected property valuesfor its target area over the next three years.

Having defined the information needed, thechair must then decide how to mobilize mem-bers to gather that information and bring itback to the committee for analysis. This can beas simple as assigning tasks to committee mem-bers and setting dates for their reports. A clearand manageable process is an absolute must, asis holding members responsible for completingtheir assignments well and on time. Withoutstructure, committees tend to meander, accom-plishing little of substance and frustrating vol-unteer board members whose lives are busyenough already.

Full participation from committee members isalso key. Overworking the most enthusiasticmembers will probably shorten their participa-tion on the committee, and perhaps even on theboard. That loss may diminish the committee’sability to achieve its goals in the short term andthe board’s in the long run. Ask for help fromor assign tasks to committee members who vol-unteer infrequently; some people simply needmore encouragement.

The leader’s next duty is to analyze the informa-tion and present recommendations to the board.This process must be defined up front and canbe delegated. The process does not have to bedifficult; it can be as simple as this:

1. Call a meeting specifically to analyze theinformation and develop recommendations.This may require subcommittee work beforethat meeting. Also, the discussion will usuallybe richer if members get advance copies ofsupporting data.

2. Assign someone to verbally summarize thec o m m i t t e e’s findings and how these find-ings shape pending re c o m m e n d a t i o n s .

3. Hold an open discussion on the issue, keep-ing in mind the meeting’s purpose.

4. End the meeting with a summary of what wasdecided, the wording of the re c o m m e n d a t i o n sto the board and any subsequent actions.

Finally, the committee chair must be a conduitfor information to the board. The effective com-mittee chair learns who in the organizationneeds what information and when they need it.The chair stays informed and keeps othersinformed with accurate and timely data thatsupports both policy and operations.

EVALUATE AND ASSESS PROGRESS

Committees exist to help the board do its work.Accordingly, committee chairs should periodi-cally review the quality and effectiveness of theircommittees’ work and determine if the work ishelping the organization fulfill its mission. Theyshould routinely monitor performance and keeptheir committees moving toward their goals.

This assumes that each committee has a we l l -defined purpose. Each committee chair muste n s u re that it does and that there are at least a f ewo b j e c t i ve measures of its success. Pe r i o d i c a l l y, thecommittee chair should evaluate the committee’saccomplishments against its goals and submit awritten pro g ress re p o rt to the board. This practicehelps keep the committee on target and high-lights potential trouble while it is still manage-able, serving as a request for help.

8

RESOLVE CONFLICT

Conflict is a natural part of life. Many conflictsare minor and easily resolved, but occasionallythey become more serious and threaten theboard’s ability to do its work. Conflict, if leftunchecked, gives rise to competition, distrust,hostility and a host of other destructive attitudesand behaviors. In extreme cases, uncheckedconflict will destroy an organization.

Once a serious conflict is evident to everyone on the board, trustees may mistakenly try one of two possible solutions — fight or flight. Thefirst approach assumes that the combatants needto fight out their problems so operations can getback to normal. The second seeks to avoid theproblem by announcing that it no longer exits.Both approaches tend to backfire. There is abetter alternative — conflict resolution.

Conflict resolution helps people deal with theirdifferences in ways that are neither adversarialnor confrontational. Some conflicts requirethird-party mediation, especially if your boardis small or has a high percentage of friends orrelatives, factors that reduce everyone’s abilityto remain objective. But you may wish to tryconflict resolution on your own before youturn to outside help.

Whether you handle the problem internallyor contract a third party, the facilitator of theconflict resolution exercise must have insight onhow to intervene when conflict appears. Thesteps a board leader or neutral mediator woulduse to resolve group conflict are:

S T E P 1SEPARATE THE PROBLEM FROM THE PERSON

Conflict is rooted in a problem.Two or moreindividuals hold different opinions about thatproblem, and their disagreement becomes hos-tile. Though the hostility takes center stage, theproblemis the real issue and is legitimate boardbusiness (unless it is just a personal dispute, andthat kind needs to be settled on the combatants’own time). The mediator must refocus the boardon the problem, and away from the disputingparties — without trampling their right to beheard. Then he can call a halt to the heated dis-cussion by announcing a 10-minute break andencourage everyone to return for the next partof the discussion with a calmer attitude.

S T E P 2IDENTIFY THE PROBLEM

Identify the heart of the problem. Listen care-fully for objective information, separating thereal issues from the speaker’s feelings aboutt h e issue — or about those who disagre e .T h i s i s n o t to suggest that people’s feelingsa re u n i m p o rtant, but the board’s job is to solveorganizational problems and make decisions.Ke e p e ve ryone focused on the real issue.

S T E P 3IDENTIFY EACH DISPUTING PARTY’SPOSITION AND C O N C E R N

Re v i ew the situation that led to the conflict,specify the problem and clarify the major con-cerns about it. Determine each combatant’sposition and what they wish to gain. Is eachwilling to negotiate? What do the part i e sb e l i e ve they will lose? What does each onethink about the other’s point of view? W h a twould help them move closer to re s o l u t i o n ?

9

Overworking the most enthusiasticmembers will probably shorten theirparticipation on the committee, andperhaps even on the board.

S T E P 4EXPLORE OPTIONS THAT WILL ADDRESSEACH PERSON’S CONCERN

What positive options could address bothparties’ top concerns? What would one partywant the other party to do? What concessions iseach party willing to make? What changes couldbe made to improve the situation? A table ofoptions measured against desired outcomes canbe useful to help find common ground.

S T E P 5AGREE TO ACT ON A JOINT RESOLUTION

Identify options both (or all) parties can agreeon, even minor ones. Address each combatant’sneeds. Record the options and secure the formalagreement of the disputing parties to considerthe matter resolved once the options have beenimplemented.

S T E P 6IMPLEMENT THE AGREED-UPON ACTION

Depending on the complexity of the solution,draft an implementation plan, or simply assigntasks to board members. Include deadlines foraccomplishing your objectives.

S T E P 7EVALUATE THE SUCCESS OF THE SOLUTION

The former competitors should meet todiscuss whether the solution is working aseveryone hoped it would. If they do not thinkit is, the group should consider repeating theseproblem-solving steps.

1 0

■ Use fair practices.

■ See conflict as normal and managing conflict as a process, not a goal.

■ Separate personal issues from the prob-lem; attack the problem, not the people.

■ Clarify interests, capitalizing on jointi n t e r e s t s and reconciling differing interests as much as possible.

■ Make proposals consistent with organizational values.

■ Facilitate two-way communication.

■ Advocate specific options, respectingt h e options suggested by others.

■ Keep an open mind.

■ Be sensitive to underlying issues andemotions; do not push when others arereluctant to expose their feelings.

■ Think carefully before speaking, takinginto account diverse interests andapproaches of the o t h e r s .

Ten Tips for Resolving Conflict

© 1999, The Enterprise Foundation, Inc.

MANAGE THE PROBLEM-SOLVING ANDDECISION-MAKING PROCESS

Individuals make decisions and solve problemsin their own way. Some are intuitive in theirapproach, while others are more deliberate andspend more time gathering facts. Successfullyleading these individuals through problem solv-ing and decision making requires know-howand practical experience.

Here are a few steps board leaders can use tohelp bring their groups to consensus. Althoughthese steps focus on problem solving, you canuse a similar process to make decisions that donot necessarily involve problems.

S T E P 1DEFINE THE PROBLEM

When a problem is clearly present but not soclearly defined, continue to ask questions untilthe heart of the matter emerges. This may takesome time. It will surely take patience if theanswers are not immediately apparent to thegroup. Here is a sample set of questions youmay want to ask:

■ What do you think the problem is? Why?

■ What is happening that should not be happening?

■ What should be happening that is not?

■ Who suffers as a result of this problem?

■ Where and when does the problem seemto arise? Any idea why?

■ How extensive (widespread or severe) is theproblem? Is it growing worse?

Using a flip chart, record the answer to eachquestion. Next, review the responses to deter-mine if there are recurring themes, especiallycontributing factors. The result should be avalid working theory about the nature, extentand cause of the problem. Identifying the realproblem is the first step in solving it.

1 1

S T E P 2LIST ALL POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS

Use a brainstorming exe rcise to encourage bre a k-t h rough thinking and generate a large number ofpossible solutions. Set the ground rules at thebeginning and ensure that the group abides bythem. Eve ry suggestion makes it to the flip chartwithout evaluation or even comment. No idea istoo far-fetched. Encourage risk taking and fullp a rticipation. Help the group build on onea n o t h e r’s thoughts. Keep eve ryo n e’s attention onthe task, squelching any side discussions that arise.

S T E P 3EVALUATE AND CHOOSE THE BEST OPTION

Re c o rd the possible consequences, good and bad,of each idea presented during brainstorming.( Keep the evaluation focused on the merits ofeach idea, rather than on the person who sug-gested it.) Then rate each solution based on theb o a rd’s ability to implement it, considering theinternal and external re s o u rces re q u i red. Choosethe best option or options. The group should ve r-ify access to the re s o u rces needed to solve thep roblem and perhaps revisit this step if theirassumptions prove to have been overly optimistic.

S T E P 4IMPLEMENT THE BEST OPTION

An individual or subcommittee should beassigned to decide upon an implementationplan for the board’s or committee’s approval.The level of detail should be sufficient to movethe solution quickly forward. It should alsoinclude benchmarks and time frames. Theappropriate people or organizations should beassigned implementation tasks and given thenecessary authority or other resources to carrythem out.

S T E P 5ASSESS THE RESULTS

The plan should contain a built-in qualityassessment to ensure satisfactory progressthroughout the implementation period. If, atany time, the solution appears to be not work-ing, then the group should consider modifyingthe solution or revisiting some or all of theproblem-solving steps. If you cannot solve theproblem on your own, consider bringing inexpert help.

1 2

The board is led by committed trustees withsolid leadership skills. However, even very capa-ble leaders can be blindsided by the difficultiesthat often surface when different kinds of peo-ple try to work together. Generally, the problemcan be traced to a breakdown in communica-tions, something board activities depend on.Although numerous factors play a role in com-municating, or the lack thereof, two stand out:cultural differences and “troublesome” personal-ities. Here are some points for board leaders tothink about as they work to keep the lines ofcommunication open.

THE DIVERSITY FACTOR

Di versity has been a buzzword in corporateAmerica for several years now. But what does itreally mean for a board? Community deve l o p-ment organizations often work in communitiesthat are home to people from various nations,cultural traditions and races, often increasing thed i versity of the board of trustees and the staff.

At times, these differences spark trouble, evenwhen everyone has the best intentions. This isespecially true when board leaders fail to recog-nize differences in the way people communicateor simply fail to respect those differences aslegitimate. When people are kept “outside,”they know it and resent it. Resentment andunity do not mix and will hinder the board’sability to do its job.

Here are a few tips to help everyone feel athome on your board:

■ Acknowledge differences and really learn toappreciate them.

■ Take time to learn about the different culturesrepresented on the board and in the commu-nity, especially what is considered polite, rude,offensive and inappropriate. For example, ifpublic disagreement is considered rude in onetrustee’s culture, this will affect his ability tocontribute to problem-solving exercises.

■ Remember, “it has always been done this way”is not necessarily an endorsement. Be open toother possibilities.

■ Just as men and women often communicatein different ways, expect people from differ-ent backgrounds to express themselves differ-ently from you. Learn their customs anda p p roaches, and help others in the group tolearn them.

■ Group process usually requires some compro-mise on everyone’s part. As your understand-ing of everyone’s differences grows, you canlead the group in finding common ground,with everyone giving a little in favor of smoothboard relations.

TROUBLESOME PERSONALITIES

Sometimes, expert group facilitation skills alonewill not disarm disruptive people. These trou-blesome types, while often assets to the organi-zation, can bring a meeting to a standstill, ruffleeveryone’s feathers and send the group’s collec-tive blood pressure through the roof ! Althoughthere are many types of group-process saboteurs,here are seven of the most common ones, withideas to help board leaders deal with them.

These saboteurs are the At t a c k e r, the De r a i l e r, theIn t e r ru p t e r, the Know - It-All, the Mo n o p o l i ze r,the Na y s a yer and the W h i s p e re r.

1 3

Group Dynamics

The Attacker

This is the member who likes to launch per-sonal attacks on other trustees — even the chair.This person may have trouble separating thecontentious issue from the people involved inthe disagreement.

Here are tips for handling the Attacker:

■ When you, as board or committee chair,re c e i ve the attack, resist the instinct to denythe charges and defend yo u r s e l f. Step backa n d take a moment to collect yo u r s e l f.W h e n it is appropriate, thank the attackerf o r the observation (if not the delive ry) andask others in the group for their opinion.Chances are fellow trustees will rush to yo u rdefense, given the o p p o rt u n i t y.

■ Turn the issue back to the Attacker for a moreuseful response, one related to the substanceof the discussion. For example: “You believeI want the executive director to have a salaryincrease only because I worked with him 10years ago. His accomplishments and compara-tive salaries are listed in the subcommittee’sreport. What conclusion do you draw fromthis information?”

■ Refocus the discussion on ideas rather thanindividuals. For example: “Dr. Raymond,surely Mrs. Copperman isn’t the only mem-ber with a dissenting opinion in this matter.Let’s write the pros and cons of the matteron a flip chart and have an open discussion.We may not resolve the issue today, butwe will hear everyone’s viewpoint withoutinterruption or judgment. Are we all in agreement?”

The Derailer

This person has a particular skill for takingnearly any discussion off the main point toone either remotely relevant or not relevantat all. A clear sign this person’s roaminghas struck a nerve is angry looks from fellowboard members.

Here are a few tips for getting the Derailer backon track:

■ Hit the brakes quickly. Once it becomes obvi-ous the Derailer is at it again, interrupt and askthis trustee to explain the connection betweenhis point and the current topic. For example,“ How does your point relate to a potential hikein our service fees?” If the trustee does not getback on topic right away, try the next technique.

■ Refer the group — but mainly the Derailer —back to the agenda, reminding them all ofpoints yet to cover and decisions yet to be made.Encourage everyone to remain focused so themeeting will end on time, having met its goals.

■ Suggest that this “new” topic be addressedunder New Business, discussed at the end ofthe meeting, or even added to the agenda ofthe next meeting. (If you agree to any of these,be sure you follow through.) If other trusteeshave issues that are somewhat related, encour-age them to make a list and present it to theboard. The group then can agree on a way toaddress the issues so everyone is heard.

1 4

The Interrupter

The Interrupter starts talking before others havefinished. Often the Interrupter does not intendto be rude, but simply grows impatient or overlyexcited. The Interrupter is afraid that his latest,red-hot idea or observation will be lost if notshared immediately.

Here are a few tips for calming the Interrupter:

■ Remember that one of your most importantroles is to see that eve ryone is heard. This cannothappen if no one can finish a thought; so dealwith the Interrupter firmly every time — nomatter that person’s rank or stature. Remind thegroup regularly of meeting protocols, chief ofwhich is that one person at a time has the floor.

■ Interrupt the Interrupter immediately withsomething like this: “Hold on, Tony; letMary finish what she was saying.”

■ Between meetings, point out to the chronicInterrupter how disruptive and disrespectfulhis behavior is to other members. Suggest thathe bring a pad of paper to write down ideasand express them at an appropriate point inthe meeting.

■ Consider making the Interrupter the recorderto exercise his listening skills.

The Know-It-All

The Know-It-All uses credentials, age, tenure,wealth, status — or maybe just a double doseof hubris — to solve every dispute in her favor.“Well, I do have a Ph.D. in urban planning. Iknow it will not work the way you people seemto think it will.”

Here are tips for bringing the Know-It-All backto reality:

■ Acknowledge the Know-It-All’s expertise once,but emphasize that the issue is being consid-ered by the groupbecause the board as a bodymust understand the issues before it candevelop sound policy.

■ Ex p ress the fact that you value maximum gro u pparticipation and the creativity and innovationit can generate. “Yes, we know this is your spe-cialty and you may be right, but one reason weare tackling the problem as a group is to comeup with some new insights and solutions. Yourexperience may actually keep you from consid-ering new ways to attack the problem.” “Weappreciate your opinion; now let’s hear fromsomeone with a contrasting view; someonemay have ideas we have not yet considered.”

The Monopolizer

These are the talkers; they seem compelled tochatter on incessantly, even when they haveput the entire room to sleep.

He re are a few tips for quieting the Mo n o p o l i ze r :

■ Set time limits for each discussion item in theagenda and remind the group, and especiallythe Monopolizer, that time is limited.Stipulate that everyone make their pointbriefly and then concede the floor to others.

■ Interrupt tactfully. Step in when theMonopolizer takes a breath — you have tobe quick! — summarize the point and inviteother opinions.

■ If you have to stop the Monopolizer while heor she is in high gear, try this useful device.Choose a phrase that the Monopolizer has justuttered. The phrase itself does not matter verymuch; it simply acts as an excuse for cutting inand taking back the meeting. For example:“An inevitable decline ... that’s very interest-ing, Edna. Robert, do you agree that decline isinevitable in this situation?” Hand the ques-tion to a more restrained talker, and you willget back on track more easily.

1 5

The Naysayer

This is the negative member, the one whobrings the rain to eve ry parade and still man-ages to empty that glass the optimists call halffull. You can re c o g n i ze the Na y s a yer by com-monly uttered, if not cherished, phrases. Fo rexample, “That will n e ve r w o rk,” or “T h a t’s aterrible plan,” or even “I don’t see why we keeptalking about this.” Eve ry Na y s a yer has per-sonal favo r i t e s .

Here are tips for lightening up the Naysayer:

■ Using your meeting protocols, encourageeveryone at the start to suspend judgment ofall ideas until they have been fully explored.Have the group agree to abide by this stan-dard. Use it to correct the Naysayer.

■ Validate the Naysayer’s feelings: “I can see youdon’t think this idea will work...” Then ask forother points of view from the group.

■ Ask the Naysayer for positive, helpful sug-gestions — ones he thinks will work or arenot ridiculous. Stress the need for ideas thatsolveproblems.

The Whisperer

Cousin to the Interrupter, this trustee is con-stantly found whispering to a neighbor duringmeetings. Too often, you have two Whisperers.This is one of the most distracting and irritatingtypes of meeting sabotage.

Here are some tips for quieting theWhisperer’s buzzing:

■ If you are standing, walk over to the W h i s p e re r sand glance at them, but continue to listen tothe group’s discussion if not continuing to talkyourself. This low-key intervention often getsimmediate results.

■ If the Whisperer becomes contagious andothers around the room begin to whisper,call them back to order: “Everyone, let’s keepa single focus here. We won’t get anythingdone if small groups go off in all directions.”

■ For the hardened Whisperer, try a school-teacher’s old trick. Stop the meeting and ask,“You two seem really interested in something.Do you want to share your thoughts withthe rest of the group?” If they decline, askthem to rejoin the larger group discussionand remain focused.

■ If these techniques fail to stop a couple ofchronic Whisperers, talk with them afterthe meeting and ask them to sit apart at thenext meeting to avoid temptation.

Group dynamics always bring the unexpected.It is highly possible that even after you haveused every technique you know, unruly typesmay remain unruly. Unfortunately, every board,sooner or later, runs into one of these types.When this happens, remember there is no sub-stitute for decisive action. When a trustee con-tinuously refuses to cooperate with existingprotocols after being warned, that trustee mustbe removed from the board. Follow the dis-missal procedure outlined in your bylaws. Oneperson cannot be allowed to keep the boardfrom doing its job.

1 6

Now that the board has dedicated trustees, capa-ble leaders and a structure that facilitates soundcommunications, the organization should berunning smoothly. This is the ideal time for theboard to prepare for trouble. The best prepara-tion takes place long before trouble arrives.

Although trouble can come from many sources,here are four different kinds of organizationaltrouble, followed by suggestions on how theboard can prepare for each one:

■ Financial adversity

■ Legal violations

■ The public relations nightmare

■ Leadership crisis

FINANCIAL ADVERSITY

There are two main types of financial adversity,one caused by malfeasance and the other by economic shifts.

M a l f e a s a n c e

Malfeasance occurs when a trustee self-deals ora staff member embezzles funds or defrauds anorganizational stakeholder. This can cause a crisisof confidence within the nonpro f i t’s group ofs u p p o rters and leave the organization on shakyfinancial ground. Any violation that jeopard i ze syour 501(c)(3) Internal Re venue Se rvice (IRS)status and your state nonprofit corporation sta-tus creates a crisis.

While a clever enough person can maneuveraround even the best safeguards, the board cantake steps to effectively reduce the likelihood ofmalfeasance. Here are some tips that will help:

■ Institute a conflict-of-interest and disclosurepolicy that eve ry trustee must sign. Re q u i reeach trustee to identify all organizationalaffiliations. Define unacceptable behavior —especially self-dealing — and its penalties.Take swift, decisive action when a violationi s u n c ove red, no matter how import a n tt h e v i o l a t o r.

■ Adopt a financial management policy manualthat ensures everyone who can spend the orga-nization’s money comes under review by some-one else in the organization. Follow thosepolicies faithfully. Have a firm other than theone that provides accounting services to yourorganization conduct an annual audit. Be care-ful of using firms headed by friends or relativesof board or staff members who have a hand infinancial transactions.

■ Develop a contracting and procurementpolicy that prevents self-dealing, as well aswasteful spending.

■ Ensure that the board reviews standard finan-cial statements regularly, asks tough questionswhen warranted and insists on the correctanswers. Never hesitate to have an objectivecertified public accountant examine the booksif something seems amiss.

Economic Shifts

Used loosely, this term refers to the changingfinancial fortunes that affect most communitydevelopment nonprofits from time to time.Federal, state and local governments and privatefoundations provide most of the program fundsfor these nonprofits. If their funding prioritiesshift, the nonprofits are left scrambling for newmoney. Here are some tips to help you avoid thered ink:

■ Expect these shifts and prepare for them bydiversifying your funding sources as much asis practical.

■ Examine worst-case scenarios long before youare in one. If your primary program fundsevaporate, will you dissolve the corporation,merge with another agency, cut back on ser-vices, reduce your staff size?

■ Look for ways to improve the results of yourprogram while containing costs. This can giveyou the edge in the fierce competition forcharitable dollars.

■ Think of ways to use new technology toaccomplish your work. You may be able to freestaff time for more substantive work, delayingor even avoiding the need to hire new staff.

1 7

Leading Through Difficult Times

LEGAL VIOLATIONS

Trustees or staff can be guilty of violating thelaw, and some violations lead to big trouble. Beespecially alert for fraud, discrimination, sexualharassment of staff or customers and failure tofile employee tax withholdings. Here are somehelpful tips:

■ Develop a personnel policy manual for yourstaff and operating protocols for the boardthat describe and prohibit various kinds ofunlawful behavior. Set severe penalties for seri-ous offenses, and implement your policyquickly when the need arises.

■ Adopt a contracting and procurement policythat contains safeguards against intentionalmisuse or squandering of funds by eithertrustees or staff. Be sure you know where yourmoney is going. Many would-be thieves havetried to siphon funds by appearing to engage acontractor, sending payments to the dummycorporation’s account and pocketing the cash.Develop thorough checks and balances, anduse them without fail.

■ Train every staff member who works directlywith customers, the public and vendors, andprovide clear standards of conduct.

■ For staff members in sensitive positions, yo umay re q u i re a successful criminal backgro u n dcheck as a condition for initial and continuede m p l oyment. This type of policy can bet r i c k y, so ask for your legal counsel’s advice.Take special care to protect potentially vulner-able populations such as children, the infirmand the elderly.

THE PUBLIC RELATIONS NIGHTMARE

You should have a crisis management plan thattells your board and staff how to respond to apublic relations nightmare because bad publicitycan come your way regardless of whether it isjustified. Developing such a plan is a job for aprofessional, so bring in a communicationsexpert early in the planning stage. Here are afew tips to help keep your reputation intact:

■ The board should be pre p a red to re p resent theorganization in a crisis. The spokesperson isgenerally the board chair. No one else, otherthan the appointed spokesperson, should speakto the press or anyone else about the matter,either by telephone or in person, except to re f e rthem to the authorized spokesperson.

■ Develop a communications plan that alertsevery trustee, member of management andstaff — in that order — about any potentialpublic-relations problem. Make every effort toensure these internal audiences are not blind-sided by front-page news.

■ Use press appearances to reassure your stake-holders and to preserve the integrity of theorganization. Do not let the press maneuveryou into admissions, blame or premature pro-nouncements. Use the interview to your advantage.

■ Remain poised in all public appearances. Youcan enhance your abilities by practicing.

■ Establish and cultivate relationships with localreporters so that your organization is morelikely to receive fair treatment from the press.

For more information on effective media tech-niques, see Media Relations: Publicizing YourEffortsin the Communicationsseries of theCommunity Development Library.

1 8

Develop a communications plan that alertsevery trustee, member of management andstaff — in that order — about any poten-tial public-relations problem.

LEADERSHIP CRISIS

A leadership crisis comes from the board orfrom the chief executive. Here are some ofthe more damaging problems these leadersmay cause.

Board Troubles

There are three troublesome qualities thatyou must address if you want to maintain astrong board:

Absenteeism. Consider asking each trustee tosign a form at the start of his or her tenure thatincludes a commitment to attend regular andcalled meetings. Most board policies permit afew unexcused absences, but regardless ofwhether the absences are excused, the boardmust do its work. If a trustee’s attendance is too sporadic, that trustee adds little value to the board. Consider asking that trustee tobecome an “advisory council” member, remain-ing involved with the organization with fewerdemands on his or her time. (Of course, youwill have to create an advisory council if you do not already have one, but the advisory coun-cil can be a great tool for tapping the expertiseof busy people.)

Disloyalty. Every trustee must be loyal to theboard and its organization, even when thatloyalty costs the trustee the chance for personalgain. Trustees may have access to confidentialor privileged information, or perhaps influenceand prestige, by virtue of board membership.Using either for personal gain is a reason toconsider termination from the board. An orga-nization that uses public funds and receives taxexemptions is open to more criticism than for-profits in some ways; your trustees must bepeople of integrity.

Indolence. Unless you have figureheads on yourboard, every trustee must be willing to work onbehalf of the organization. This may meanaccepting committee assignments, representingthe organization in public, helping with fund-raising activities or just keeping abreast of whatis happening in the organization and its indus-try. Inactive trustees are dead weight. If you canfind ways to energize them, do it. If not, askthem privately to rise to the task or step downfrom the board. If they refuse, exercise the dis-missal provision in your bylaws and find a com-mitted and energetic replacement.

Trouble With the Chief Executive

The board re c ruits, hires, supervises and fires thec o r p o r a t i o n’s chief exe c u t i ve. Dismissing thise xe c u t i ve invo l ves one of the toughest dutiesmost boards will face, but when it must be done,the board must know how to do it corre c t l y.

Before taking this drastic step, the board mem-bers should have made every reasonable effort tosolve their problems with the chief executive.The basis for their interaction should be thepersonnel policy and the due process it outlinesas well as any contract between the executiveand the board.

Here are some early interventions that mayeliminate the need to talk about dismissal:

■ Conduct informal assessments, offering con-structive feedback to the executive to helpprevent the escalation of existing problems.Simply letting the executive know how theboard views the executive’s performance canhave a positive effect. Often employees adjusttheir performance when they see their short-comings. The board must point out theseshortcomings clearly and firmly as soon asthey become evident, but avoid intentionalpersonal attacks.

■ Coach the executive to help her improve herjob performance, especially when the difficultystems from a lack of specific knowledge orinformation that is peculiar to your organiza-tion. You may see quick results if trustees takethe time to teach, guide and share. After all,supporting the chief executive is one of theduties of the board.

1 9

■ Conduct formal assessments through specific,comprehensive reviews at intervals agreed toby both the board and the chief executive.Following criteria established at the outset byboth parties, these assessments are usuallybased on annual organizational goals andobjectives. The primary purpose of such anevaluation is to help the executive performmore effectively. Neither the board nor theexecutive should expect success without theother’s support.

■ Remember that federal, state and local regula-tions govern specific policies, procedures andactions related to personnel matters. Theseinclude the Americans with Disabilities Act,drug-free workplace rules, anti-discriminationlaws and others.

■ Learn about and understand regulationsthat require you to allow employees to obtaincounseling through an employee assistanceprogram or some other counseling resourcebefore you can terminate employment. Thecounseling may be for job-related matters orfor personal problems that affect job perfor-mance. Substance abuse, stress, depressionand mental illness fall into this category.

■ Investigate. Dig deeply into all the facts when-ever an apparent problem arises concerningyour chief executive. Your decisions must befair and objective, and they must be madequickly when the situation warrants.

■ Listen very carefully. Allow the executiveample opportunity to explain what happenedand why. Listen without pre-judging. Theboard must give everyone involved a fairhearing and collect all the facts before rendering judgment.

■ Keep records. Documentation during theproblem-resolution stage is important, becauseyou must be able to demonstrate fair, equi-table and reasonable treatment when dismissalis inevitable. The record of the board’s interac-tion with the executive may help the boardreach critical decisions about the chief execu-tive’s future.

■ Match corrective action to the offense, takingthe executive director’s record into considera-tion. A series of minor offenses may accumu-late and justify discipline that the director’slast act alone would not justify. On the otherhand, a long history of good performance mayjustify less severe treatment when the executivecommits an offense.

When dismissal is your only option, be sure tofollow your organization’s policies to avoid animmediate lawsuit. (It may not prevent one,but ignoring your own policies is an open invi-tation to litigation.) If you must dismiss, be fair,but be quick about it; the problem will onlyfester when left unresolved. A similar option isto request the chief executive’s resignation. Thismay be the preferred option when the boardand the executive simply do not see eye to eye.

If dismissal is inevitable, take steps to controlpublic relations. Do not risk being put onthe defensive after a disgruntled former execu-tive begins to spread ugly rumors. Identifyyourmessage and get it communicated tothe right audiences.

While community improvement earns yourboard many accolades, less appreciated taskscome with the territory. Working to correctjob performance problems or dismissing yourchief executive when necessary may make theboard feel like the bad guy, but your firstloyalty is to the organization and its mission.You must make tough choices when thatmission is at stake.

For more detailed information and guidanceon the board’s responsibility for the executivedirector, see Evaluating Your Executive Director,another book in the Governanceseries of theCommunity Development Library.

2 0

Documentation during the problem-resolutionstage is important, because you must be ableto demonstrate fair, equitable and reasonabletreatment when dismissal is inevitable.

The board of trustees is like a living organism— it grows and changes over time. Typically,trustees serve for a period of years and then endtheir board service, being replaced by the nextmembers. Through this continuous change inboard composition, the organization mustremain stable. The board has at least two waysto leave a valuable legacy: adopt organizationalpolicies and groom others to lead.

ORGANIZATIONAL POLICIES

Policies can be assembled into one or moremanuals to keep board and staff informed of thecorporation’s policies and procedures and of anychanges to those policies and procedures. Theyalso explain how the organization functions. Inaddition, policies help protect the board andstaff by ensuring fair and predictable treatment.The board has its own operating manual. Theremay be one or more manuals that address staffand day-to-day operations.

The Board Manual

Compiled for the trustees, this manual is acomprehensive source of information aboutthe organization and its governance. It containsbackground and history along with importantorganizational documents. Because trustees ofcommunity development organizations are usu-ally volunteers who meet only periodically, theboard manual helps keep them organized andinformed. The board manual also serves as animportant orientation tool for new trustees.

Often organized in a three-ring binder, theboard manual may include some or all ofthese documents:

■ Articles of incorporation

■ Bylaws

■ IRS letter of determination (of tax-exempt status)

■ Mission statement

■ Copies of formal organizational plans, such asthe strategic, business and fund-raising plans

■ Formal financial statements and audit reports

■ Current operating and program budgets andbudget-to-actual reports

Operations Manuals

An organization may have one or more manualsto describe the flow of daily life in the organi-zation. They include financial management policies, personnel policies and standard operating procedures.

A financial management policy is one of themost important documents an organizationhas because it delineates many of the ways theboard meets its duty to safeguard organizationalassets. Accounting policies detailing the processfor spending and reporting the organization’sfunds are the backbone of the document. Anexperienced certified public accountant isa valuable ally in developing these policies.The board should play an important role intheir implementation.

Other policies that address daily organizationallife are usually crafted by management or by hire dconsultants. The most common are personnelpolicies and standard operating pro c e d u re s .

Personnel policies describe the benefits providedby the organization to the employees, the stan-dards they are expected to uphold and how tofile a grievance if the employee believes he orshe has been mistreated. The provisions in thismanual often impact hiring and firing decisionsand should be carefully crafted. Legal adviceduring policy development is critical since fed-eral and state laws govern personnel matters.

Standard operating procedures detail routineorganizational activities — from internal com-munications and dress codes to safety measuresand attendance reporting. As the number ofstaff increases, an organization’s standard proce-dures grow in importance because they mini-mize the impact of turnover on operations andimprove overall communication and efficiency.

2 1

Leaving a Legacy

GROOMING OTHERS FOR LEADERSHIP

Ef f e c t i ve leaders see the importance of gro o m-ing others for leadership. The strategic infusionof capable new leaders gives an organizationt h e vitality it needs to surv i ve for many ye a r s .An organization benefits from the wisdoma n d experience of seasoned board leadersj o i n e d with the passion and creativity ofn ew ones. The search for the right balancei s a n ongoing process that helps keep theb o a rd f rom settling into stale ways oft h i n k i n g and acting.

One way to ensure strong organizational leadership for the coming years is to cre a t ea leadership re c ruitment plan, perhapst h ro u g h the nominating committee. Id e n t i f ycandidates from among the organization’sp r i m a ry stakeholders, especially the targetcommunity and other service organizations.Consider inviting them to take part in com-mittee work or one-time organizationalp rojects, building the relationship betwe e nthem and the organization.

Another option is to offer formal leadershiptraining sessions to anyone interested in com-munity leadership, either with your organiza-tion or another one. This can be an effectivetool for mobilizing young adults in the com-munity who are looking to develop and usetheir leadership skills. It also offers re t i re dpersons the chance to use their time andt a l e n t for a worthwhile cause.

The exe rcise of leadership development may produce new leaders for your board ,b u t i t also helps existing leaders grow intheir ability to serve the organization — a classic win-win situation.

STEPPING ASIDE GRACEFULLY

Is there an optimum tenure for board officers andcommittee chairs? Some serve very competentlyover a period of years, while others lose interestor burn out from the stress of serving long terms.While there is no rule for optimum terms, hereare several ideas for consideration. (Althoughthis information can refer to officers or commit-tee chairs, the term “officer” is used here.)

■ In the first year of the term, an officer is justbeginning to grasp the position’s roles andresponsibilities, even if this person has been onthe board for years. Accordingly, a two-yearterm is better than a shorter one, and a three-year term may be even better.

■ Each board must decide whether to permitsuccessive terms. But even if they are permit-ted, an officer should serve a second term onlywhen he or she can offer benefits another can-didate cannot. A second term that is used as areward for faithful service may not be the bestchoice for the organization and its mission.

■ The board should be aware of certain warningsigns that signal the need to end an officer’sterm. These include a lack of interest in boardmatters, indications that board business is nolonger a key priority and the use of personalinfluence or control that blocks or sabotagesnew ideas.

No doubt there are leaders with vision, ingenu-ity and character who provide tremendousdirection for many years. But when a leaderbegins to damage the organization, the boardshould consider a new role for that officer.When that time comes, the officer should stepaside gracefully, with public recognition by theboard and its community of the immense con-tribution this officer has made to the organiza-tion over the years.

In the ideal world, capable leaders would servetheir terms, leave the board when the timecomes and remain friends of the organization,passing along their wisdom, skill and enthusi-asm to others for as long as they can.

2 2

THE ENTERPRISE FOUNDATIONThe Foundation’s mission is to see that all low-income people in the United States have accessto fit and affordable housing and an opport u n i t yto move out of poverty and into the mainstreamof American life. To achieve that mission, westrive to:

■ Build a national community revitalization movement.

■ Demonstrate what is possible in low-income communities.

■ Communicate and advocate what works in community development.

As the nation’s leader in community d e ve l o p m e n t ,Enterprise cultivates, collects and disseminatesexpertise and re s o u rces to help communitiesa c ross America successfully improve the qualityof life for low-income people.

A C K N O W L E D G M E N T SAuthors: LaCharla Figgs, The EnterpriseFoundation; Carlene Morgan, President,Diversified Management Associates,Washington, D.C.Contributors: Bill Batko, Carter Cosgrove +Company, Ben Hecht, Catherine Hyde, Jane Usero

SPECIAL THANKSResearch and development of this manual wasmade possible by the National CommunityDevelopment Initiative, which is a consortiumof 15 major national corporations and founda-tions and the U.S. De p a rtment of Housing andUrban De velopment, and score s of public andprivate organizations. NCDI was created tosupport and sustain the efforts of communitydevelopment organizations.

FOR MORE INFORMATIONThe Enterprise Foundation10227 Wincopin Circle, Suite 500Columbia, Maryland 21044-3400

tel: 410.964.1230fax: 410.964.1918email: [email protected]

For more information about The EnterpriseFoundation or the Community DevelopmentL i b r a r y™, visit us at w w w . e n t e r p r i s e f o u n d a t i o n . o r g .To review our online community magazine, checkout w w w . h o r i z o n m a g . c o m .