LDOC Issue 01.02

description

Transcript of LDOC Issue 01.02

LDOCMonday, October 19, 2015Issue 01.02

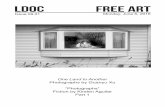

artistNathan pearce

A free bi-monthly photography and creative writing publication

eric Hazen“This Time Next Year”

“Midwest Dirt”

writer

kept waiting for him to open his eyes. My newborn nephew, Lucas, less than two days old, was laying at the end of the u-shaped neonatal intensive care unit with his eyes closed. Heat lamps hovered over his incubator. There were tubes everywhere. An oxygen mask wrapped around his face. An IV line ran directly to a vein on his head. A feeding tube ran through his nose and down his tiny throat, taped to his face to keep him from pulling it out. Sometimes he gagged. The surgeon and the doctor and the nurses all talked in percentages and acronyms that I didn’t want to understand. I just wanted him to open his eyes. It seemed so important that he open his eyes.

The day before nothing had seemed important enough to be taken seriously. My job sucked. My parents were pissed at me, and Sam had broken up with me.

I’d stopped to grab a pack of cigarettes and a pop at Coop’s on my way home from work. Coop’s is this shitty gas station and bait shop in a small clearing at the edge of the state hunting grounds. Randy, the owner, used to sell ammo on the sly before the state cops came after him. All the hunters still stopped there anyway to stock up on jerky and coffee.

I screeched my car to a stop beneath the blinding fluorescent flicker under the canopy. In the dark you can see it glowing against the trees a mile down the road. It was late, there wasn’t anybody else there.

A bell clanged on the door as I walked into

the familiar smell of Coop’s. They kept utility sinks full of minnows along the back wall for the fishermen and, mixed with the gasoline fumes, salted snacks, and burnt coffee, the smell was something between a forgotten fish tank and the backseat of your grandpa’s car.

“Say it ain’t so!” a voice I half recognized hollered from behind the counter. I turned to see Chris Bylsma, one of my brother Joe’s friends from high school walking toward me.

Chris had been on the hockey team with Joe. He had been good too. Big and fast and skilled, all-state his junior and senior year. Some people in town thought he was good enough to go as far as he wanted to. I used to kind of worship him when I was a kid. But he didn’t look like he was playing much anymore. He didn’t really look like he’d been doing much of anything lately. He had a gut that swayed and rippled in front of his large frame. His face was fleshy and bloated.

He looked me up and down. “Still looking like a little fucking punk,” he said, pointing at my ripped up jeans and greasy blue hair.

The last time I’d heard Joe talk about Chris it was just to say that he was working at some plant in Muskegon and that his girlfriend was pregnant again. I knew my friends Dave and Ian and a lot of other people were buying weed from him, but I hadn’t seen him in a couple years.

“What the hell are you doing here?” I said, hearing echoes of Sam when she’d said the same thing to me when I showed up at her house stoned and drunk on the night she broke up with me.

I

“Eh, you know, working,” he said. He’d been laid off from the plant and Randy had him working under the table. “Unemployment don’t cut it when you got brats to feed,” he said, looking down at the dirty floor.

I opened the cooler and read the label of every single bottle. I couldn’t stand to look at Chris fucking Byslma saying shit like “unemployment” and “laid off.” The gut and that fat, bloated face made me feel horrible in a way that I couldn’t quite categorize.

“If you’re not finding what you’re looking for in there I got a couple beers stashed in the back,” he said over my shoulder. He looked so pathetically grateful when I said yes.

We went outside and leaned against the wall next to Chris’ pickup truck as we slurped at our beers. We didn’t say much, just stared out into the darkened woods like something might burst out of the trees at any second and change everything or at least give us a topic for conversation. He asked about my brother a little bit. I didn’t know what to ask him. How’d you end up here? How’d you go from star athlete to fat, laid off slob drinking beers with an 18 year-old kid outside of the shit hole you work at?

What the hell are you doing here? That question wouldn’t stop rolling around my stomach. Not even a second beer, sucked down quick so I could get away from Chris as fast as possible, made it sit still.

I threw my can in the back of Chris’ truck with a hundred other empties and told him I’d see him later. He walked me back toward my car.

“You ever want to burn them all down?” he asked me with a messy, slow slur that I hadn’t noticed before, pointing back toward the trees. “Just set them on fire and see what’s hiding in there, or what it’d be like to see as far as you wanted in any direction without all those trees in the way?”

“I guess I never thought about it,” I said with my car door half open. I must have given him a look because he shook his head and laughed too loudly.

“Yeah,” he said, “Hey, tell your brother I said hi, will ya?” He punched me in the arm and stumbled back toward the store.

I pulled back onto the road, forgetting the cigarettes and pop I’d stopped for, and tried not to imagine the woods on either side of my car on fire, squirrels and bunnies and baby foxes running for their lives from Chris Bylsma with a flame thrower and a beer in his hand.

Everything was a joke. And on the day that

Lucas was born, I was sitting on my parents’ front porch laughing. They were already at the hospital with my brother and his wife so Dave and Ian and I decided to raid their fridge while they were gone. We were finishing the beer we’d stolen and recounting some trouble we’d gotten into with a pair of bolt cutters at the local zoo a few nights before.

We were also waiting for our new weed guy to call. Bylsma wasn’t answering Dave’s calls.

Well, actually, I was supposed to be waiting for Joe to call and tell me it was time to come to the hospital and see the baby. I was kinda hoping the weed guy would call first. That way, I could get stoned before I had to leave.

When the phone finally rang it was Joe. “Hey dude,” I said, trying to sound excited.

“Dude...” my brother said, “Dude, can you get here quick?” I’d never heard his voice sound that way, like his breath was shaking inside his lungs and he was fighting back tears filled with razor blades. “Please,” he said.

I don’t know. Maybe it was the sound of his voice. Maybe it was seeing Bylsma the night before. But when he said “Please,” something in my brain flashed on. A light that had been out for a while.

I sprinted off the porch to my car, knocking over the small table that held Dave and Ian’s beers. “What the fuck, man?” Ian said. I got to the car and he yelled, “Where are you going? How are we supposed to pick up the herb?”

I made it to the hospital in 15 minutes. When the thick, wide doors to the maternity ward swung open, I saw Joe sitting on a bench at the far end of a long hallway. He was in scrubs. His head was in his hands. My parents sat on either side of him. My mom had her arm around his shoulders.

A nurse sitting at the reception desk said, “Sir, you need to sign in.” I ignored her.

Joe had looked up and then he was moving down the hallway toward me. I stepped past the nurse holding her clipboard for me to sign and stepped into the hardest hug I have ever shared with my brother. There was nothing to say. I wrapped my arms around him and he cried. Thick, heavy sobs that started in his guts and shook his whole body. And I cried because I’d never seen him cry like that before.

It felt like months since I’d seen him. Before his wife Jessica had gotten pregnant, we hung out almost everyday. But then there were ultrasound appointments and trips to pick out baby clothes and he just didn’t have time for me anymore.

There were deep gray bags under his eyes. He hadn’t shaved and the stubble crawled across his

chin in uneven patches.A doctor approached us. I let go of Joe so he

could hear what the doctor had to say and it felt like the cruelest thing I had ever done to him.

“You can come back in now,” the doctor said. “We’re going to be moving him to surgery in a couple minutes.”

Joe rushed through a door and I looked after him and then back at my parents in their waiting room chairs, confused at what I’d just heard. “Surgery?” I said aloud.

The nurse with the clipboard made it clear that I wasn’t allowed to follow him and that I had better sign in.

On the other side of that door, while my parents—who were just one more mortgage payment and two more screaming matches away from divorce—awkwardly tried to explain what was happening without actually looking at or speaking to each other, Joe would pick up his son for the first time, his son with wispy brown hair just like his and a dimple on his left cheek like his mom.

Completely unsure of what to do with a newborn, he would try to hold him in front of Jessica’s face. It had been an emergency C-section and the heavy anesthetic blurred her eyes.

“I can’t see him,” she would keep saying, “please let me see him before you take him away.”

I wasn’t allowed into the room with my brother and sitting in the waiting room with my parents was not a place I wanted to be. I escaped to my car to have a cigarette. While I sat there imagining what was going on in the operating room, my phone rang. It was the new weed guy. I let it ring.

I walked into the waiting room twenty minutes later and found my parents. My mom had her head on my dad’s shoulder. They were holding hands. It was the first time I’d seen them touch each other for a long time. They stood up as I walked toward them and my dad put his hands on my shoulders and looked right into my eyes, the way he’d been doing every time I’d seen him lately, trying to decide if I was high or drunk or whatever. For once my eyes were clear. “I’m glad you’re here,” he said.

Around 3am, after his surgery, after they ran all his tubes, after they had him stabilized, the nurses let us into the NICU to see Lucas and Joe and Jessica. All of us gathered around Lucas’ incubator and looked for any sign of movement. He still hadn’t opened his eyes.

And we stayed there for three months.When you spend that long around a hospital,

you start clinging to all these clinical terms. These shorthand ways of explaining all the confusing and terrible things that won’t stop coming at you, these sanitized acronyms that don’t really mean anything. Ours was CDH. Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia.

We repeated it like a mantra. When his temperature wouldn’t stabilize, when he caught an infection, when they had to run a central line through his leg, when they wouldn’t let us touch him, all we could say was CDH.

We said it to the phone calls and the cards and the emails, CDH, Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. It was so clean, so bloodless, so much easier than saying that he had been born with a

hole in his diaphragm and that all of his insides had pushed up through that hole, displacing his heart, putting so much pressure on his lungs that they hadn’t developed completely. So much easier than explaining that the surgeons had opened him up and tried to put everything back together again.

CDH.And each time we said it, we moved just a

little bit closer to each other. The NICU at North Ottawa Community Hospital became like an intensive care unit for my entire family.

“CDH,” I said to Sam when she called. She’d just heard what had happened. It was good to hear her voice, even though she sounded so far away. I missed her. Not in a relationship, “please take me back” kind of way. Just her. Just Sam the person.

I said it to Dave when he called too. He wasn’t calling about Lucas. He called to tell me that Bylsma was gone, that they’d found him beneath the tree he had hung himself from. The branch had snapped. The thick leaves had covered his entire body and the hunter that had found him hadn’t known he was there until he tripped over Chris’ leg. Dave wanted me to know that I was probably the last one to see him. I wanted Dave to know that Chris had died a long time ago, but I didn’t say a word.

CDH.I said it to myself when I was sitting next to

Lucas’ incubator, looking at those tiny fingers and toes—fingers and toes that I was falling in love with. And those silent, still eyelids, those eyes that I wanted so badly to open.

And when they opened, what would they see? What would my nephew see when he looked at me?

It wouldn’t have been much at that moment. A kid too scared of the future to do anything but hide from it. A boy clinging to the debris of the past while the present roared past him.

And what if they never opened at all? What if this tiny thing with nothing but the future ahead of it never even had a chance to see the world he could be a part of ?

What was the moment that you realized things could be different? That things could be better? The moment you stood up or let go or fought back, the moment you asked for help or realized or finally understood?

For me, it was a moment during that third month in the hospital. It was late afternoon, the sun was out, the hospital was quiet. I’d just gotten done with an early shift at work. I slipped into the NICU and the nurse with the clipboard smiled at me and waved me in.

I sat down in the creaky wooden rocking chair next to Lucas. The heat lamp over his incubator buzzed, a steady beep counted each flicker of his heart.

It was the moment that I leaned back in the rocking chair and the legs of the chair gave out a low groan and Lucas jerked his head at the sound.

It was the moment that I rocked forward again, leaned over the edge of the incubator. It was the moment that I looked down.

And there they were--these huge, round, bright blue eyes—looking right at me.

They were wide open. •

The second installment of this issue will be available on the third Monday of this month; same time, same train stations.

www.l-doc.org

Nathan Pearce (born 1986) is a photographer based in Southern Illinois. He also works in an auto body repair shop. In addition to making photographs, he makes photobooks and zines. He is the co-founder of Same Coin Press, an independent photobook and zine publishing collective. His work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally and is in several public and private collections. www.nathanpearcephoto.com

Eric Hazen is a company member at 2nd Story, where he tells stories, produces a podcast and plays with sound. He holds an MFA from Columbia College Chicago and works for the award-winning art and design blog Colossal.

LDOC is a free photography and creative writing publication distributed every first and third Monday at the following Red Line stops: Loyola Ave, Belmont Ave, Chicago Ave, Lake St, 69th St, and 95th St. LDOC features a new local artist and writer each month, creating an accessible installment-based art experience for the Chicago commuter.

Visit l-doc.org to subscribe, submit, and purchase prints.

LDOC is currently fully funded by the 2015 Crusade Engagement Grant from Crusade for Art. www.crusadeforart.org