Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean. The Inter...

Transcript of Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean. The Inter...

♯11 second semester 2017 : 144-151

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean… / Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero

Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero (Universidad del Atlántico, Colombia)

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean. The Inter-American Modern Art Salons of Cartagena (1959) and Barranquilla (1960 and 1963)

ISSN 2313-9242

♯11 second semester 2017

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean… / Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero 144

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean. The Inter-American Modern Art Salons of Cartagena (1959) and Barranquilla (1960 and 1963) Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero (Universidad del Atlántico, Colombia) In the mid-twentieth century, three editions of the Salones Interamericanos de Arte Moderno were held, one in Cartagena (1959) and two in Barranquilla (1960 and 1963). Artists and intellectuals very active in the inter-American circuits of the time were involved in the salons. The events led to, for instance, the opening—premature in the Colombian context—of modern art museums in Cartagena (1959) and in Barranquilla (1960).1 Latin American art history has pointed out on many occasions the reinforcement of ties between the United States and the region after World War II. Due, in part, to ideological interests, art circuits took shape and inter-American exhibitions, salons, and biennials sprouted up around the continent during the Cold War. Crucial to that process was the work of the Organization of American States (OAS) and of the director of its Visual Arts Unit, José Gómez Sicre (1916-1991).2 The salons in Cartagena and Barranquilla formed part of that inter-American fabric; they were a privileged setting for Gómez Sicre’s work in Colombia and a key factor in his relations there.3 Though artistic and cultural institutionalism was, at the time, still quite precarious in both cities, there was, starting in the mid-forties, an active group of avant-garde artists and intellectuals in each; their initiatives gave rise to the first art institutions in the local

contexts. The inter-American salons provided an opportunity to further those processes and to legitimize them through internationalization. Interplay of interests A number of factors were at play in the close relationship between the OAS’s Music and Visual Arts Units and the cities of Cartagena and Barranquilla, among them Gómez Sicre’s interest and affinity with local artists like Alejandro Obregón and Enrique Grau, whom he repeatedly called the central figures in groundbreaking modern art in Colombia (Gómez Sicre, 1963).4 Furthermore, Gómez Sicre’s counterpart as the head of the OAS’s Music Unit from 1951 to 1975 was Guillermo Espinosa (1905-1990),5 a musician from Cartagena. At the same time, both Cartagena and Barranquilla were port cities undergoing processes of modernization. During the first half of the twentieth century in particular, they were very attractive to North American investment and as locations for multinational companies. If, as stated above, the art institutions in those cities were incipient and erratic in their operations, a process of modernization had been underway in both since the forties, one that entailed a series of concerns and initiatives on the part of artists, writers, thinkers, and local cultural administrators.6 Those players were the engine behind new art venues; they attempted to put in circulation and to legitimize, in their local contexts, new visual languages and the idea of the “modern” and professional artist.7 The inter-American salons, then, were not an isolated project, but part of a mechanism that entailed, among other things, a series of earlier salons. Over the course of two decades, they were held erratically; their names, scales, and scopes varied as well. Seven editions of a regional salon called El Salón de Artistas Costeños were held from 1945 to 1953. That salon was then turned into a nationwide event of which two editions were held in Barranquilla (1955 and 1959) and one in Cartagena (1959); artists more active and known on the larger Colombian scene participated in that national version of the salon. Finally, those national salons led to the inter-American events. In all of its incarnations, the salon stimulated exchange between the two cities and between the Caribbean region and the wider Colombian art

♯11 second semester 2017

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean… / Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero 145

scene. A single group of local cultural administrators and artists was involved in the organization of the salon, among them Alejandro Obregón—from Barranquilla—and Enrique Grau and Cecilia Porras—from Cartagena. All of them were also active participants in the Bogota art scene, specifically in the group led by Marta Traba after her arrival in Colombia in 1954. They were the minds behind “true” modern art in Colombia, as opposed to the earlier generation which had been tied to localisms and nationalisms. These local processes, though recent, were growing. And throughout the fifties—in a context where the art field was still extremely precarious—a strategy was enacted to legitimize and renew art, to support young local artists, and to create new cultural spaces. The tension between nation and region was evident in the earlier salons in Cartagena and Barranquilla. In the information that circulated, particularly in the press, the tendency to praise the quality of the artists from the region as compared to “national art” as a whole is patent; frequent mention is made of the artists and writers from the Caribbean region that, together, were at the forefront of Colombian modernism. As a result, local elites began to support regional talent as a fundamental part of Columbian modern art,8 and Cartagena and Barranquilla as unquestionable centers of the country’s cultural movement. It is essential to point out, along those lines, the historical tension between the two largest cities in the Caribbean region and the center of the country—especially the capital—a tension with deep roots in politics and economics. Cartagena was the most important port during the colonial era, and there were always tensions over what city would be the country’s capital. Strategically located at the mouth of the Magdalena River—for a time the country’s most important transportation route—Barranquilla was, starting in the late nineteenth century, the country’s largest port. That, along with quick modernization, particularly in the twenties and thirties, brought remarkable growth. Starting in the forties and fifties, however, the city began to decline as river transportation grew less and less important and the thrust of the economy shifted to coffee, which implied moving activity to the port of Buenaventura on the Pacific. The economic and industrial decline of Barranquilla

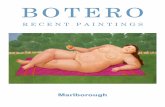

generated visible tension because it was associated with centralism. In the inter-American salons, a number of different interests came together at strategic moments. If, for Gómez Sicre, the salons were key to his work in Colombia and to the consolidation of the type of avant-garde he was interested in promoting, they represented, for local players and their initiatives, a fertile occasion to make connections and to find legitimation through, for instance, internationalization. There was, then, a synergy of projects. Common traits of the inter-American salons in the Caribbean region of Colombia In 1959, the IX Festival de Música de Cartagena was held. Guillermo Espinosa had been the organizer of the festival—an attempt to foster cultural rebirth in the city—since 1945. From his new post at the OAS, he resuscitated a festival that had not been held since 1953, and gave it a new inter-American scope. On the occasion of the ninth edition of the music festival, the Exposición de Pintura Interamericana de Cartagena was organized with the support of Gómez Sicre. (Fig.1)

Fig. 1. General view of the Exposición Interamericana de Pintura Contemporánea de Cartagena at the Galería del Palacio de la Inquisición. From left to right: Objeto negro (1956) by Oswaldo Vigas, an unidentified work by Ángel Hurtado, Composición en negro (1958) by Enrique Grau, Casa de Venus (1957) by Fernando de Szyszlo and Carnicero (1957) by José Luis Cuevas. Photo published at the Boletín de Artes Visuales of the Unión Panamericana, N. 5, May-December 1959. Gómez Sicre’s support was sought one year later in Barranquilla in an effort, organized on the occasion of the anniversary of the city’s founding, to follow the example set by Cartagena and turn the Salón Anual de Barranquilla into an inter-American Salon. The

♯11 second semester 2017

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean… / Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero 146

idea was an initiative of the Centro Artístico,9 particularly of writer Álvaro Cepeda Samudio (1926-1972) and of Obregón. Gómez Sicre’s presence in the city was nothing new. Since 1956, the local press had reported on his visits to Barranquilla—which pursued many different aims—as well as his whereabouts as he worked on projects throughout the continent. Furthermore, Gómez Sicre contributed personally to various publishing projects that gave rise to new spaces for art and culture in the press in Barranquilla. In 1956 and 1957, after the Hojas Literarias supplement was created, Gómez Sicre periodically submitted extensive articles on modern art, in defense of abstraction, and in opposition to political or ideological art. (Fig.2)

Fig. 2. A local newspaper highlights the visit of José Gómez Sicre to the city of Barranquilla. At the photo, Alejandro Obregón (right) and the director of the Sección de Artes Visuales holding the brochure “La OEA al servicio del arte”. Diario del Caribe, November 13, 1961.

The third inter-American salon was held three years later, in 1963. It coincided with the celebration of the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the city’s founding, occasion for a series of events. The Centro Artístico took advantage of the opportunity to refloat the idea of a major salon that formed part of a broader campaign to promote Barranquilla as cosmopolitan city of progress and civilization.10 The common features of the three salons held in the Caribbean region of Colombia attest to Gómez Sicre’s repeated deployment of the same strategies throughout the continent. 11 The salons spread certain ideas about art, circulated certain images, and insisted on the importance of a single group of artists that interested Gómez Sicre.12 Emphasis on the events’ remarkable scale was an attempt to place Cartagena and Barranquilla at the center of the continent.13 Furthermore, Gómez Sicre invited other figures from the rest of the country and beyond to participate in the salons, figures prestigious enough to shift attention from what was actually going on in these cities and to provide legitimacy. Those guests—who sometimes formed part of the jury—gave interviews and lectures, and communicated ideas, sometimes published as texts, in the local, Colombian, and international press about what was going on in the cities and about the conception of modern art promoted. One frequent and key guest was Argentine critic Marta Traba. On the occasion of the 1959 edition of the Salón de Cartagena, she wrote an article, “Un laurel para Cartagena”14 (1959), for the Colombian press backing the initiative; she also wrote the introduction to the catalogue of the Salón de Barranquilla in 1960. The media covered her visit to the show widely, publishing interviews in which the critic stated that it was the best show she had seen in Colombia.15 (Fig.3) At the same time, Gómez Sicre also advocated the idea that the salons grant purchase prizes to build the collections that would give rise to modern art museums in Cartagena and Barranquilla—an idea resoundingly embraced by the local actors who had supported the formation of regional salons in coastal cities.16 In fact, at each of the inter-American salons over ten prizes were awarded. Those award-winning works, along with works that participated in previous salons, became part of

♯11 second semester 2017

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean… / Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero 147

both modern art museums’ founding collections.

Fig. 3. Marta Traba and Alejandro Obregón visiting the II Salón Anual de Pintura. El Heraldo, April 12, 1960. Meanwhile, artists and other local actors made the most of the salons as a means to further their own projects. The international salon was a way to legitimize the languages of modern art in local contexts where they were still met with much resistance and to consolidate a network of institutions that would establish, in no uncertain terms, the pre-eminence of the strain of modern art local actors were developing. Marta Traba played a crucial role as the advocate of a new generation of Colombian artists in which the three artists from the Caribbean were central figures. The formalist reading: seeking common traits in Latin American art The salons’ administrative strategies were tied to Gómez Sicre’s interest in defining Latin American art as a recognizable corpus and in building a solid circuit that would legitimize it. The artists selected were deemed, by Gómez Sicre, a group representative of Latin American art. Time and again in exhibition catalogues and in public statements, the idea that the salons evidenced common traits that defined the artists in the region was emphasized rather than the value of the works of individual artists. As an array of researchers have studied in other contexts, the specific bent of Gómez Sicre’s reading of Latin American art consisted of frank rejection of the social realism associated with

Mexican muralism, as well as Indianist and Americanist movements; he upheld instead a type of art that would dialogue with the international languages of the European avant-gardes without losing its “Latin American accent”. His interest revolved around a strain of art that might have certain connections to local contexts, but that veered to the universal and could be read from a formalist perspective.17 That approach hoped to neutralize political contents and to defend freedom as maximum value of creation in democratic contexts. At his presentation at the opening of the Salón de Cartagena, Gómez Sicre associated new Latin American art with Cubism; he urged viewers to focus on emotion, inner strength, color, and other visual values as they looked at the works.18 During this period,19 Marta Traba seconded Gómez Sicre’s support of a supposed formalism, a stance that displaced artists associated with muralism and Americanists; the Cartagena and Barranquilla salons were privileged venues where the affinity between the Argentine critic and the Cuban cultural administrator grew.20 The salons were also strategic in the generational rift taking place in the dynamics and relationships in the art field in Colombia at the time, a period that witnessed the emergence of a historiographic discourse according to which modern art in Colombian was born with this new generation. While this topic deserves study from multiple perspectives, I will focus on one. The figure of Alejandro Obregón was particularly dear to Traba and Gómez Sicre, and they agreed he was the great innovator of Colombian art. Indeed, he was awarded first prize at the two Barranquilla salons; he was also awarded a purchase prize at the Cartagena salon, where no distinctions were drawn between first and second prizes. Winning international prizes alongside artists considered, in the framework of the salons, the best in the continent was, for Obregón, substantial backing as he continued to consolidate legitimacy both locally and nationally. Though the three salons, as well as Traba and Gómez Sicre’s discourse in the period, doggedly upheld formalism and a self-referential modern art devoid of references to political issues or contents, Alejandro Obregón was not an artist inclined to pure abstraction. Indeed, his work repeatedly addressed political issues and

♯11 second semester 2017

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean… / Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero 148

violence in Colombia. While, in this effort to depoliticize contents, the salons attempted to form a group of artists around an exaltation of formal values to which abstraction was key, the works and artists on exhibit in them did not always match that vision. It is also true that Obregón managed to devise strategies to formulate a dialogue between both components—the pictorial and the political. Though pictorial problems are structural even to his works that address political issues, some of those issues were too recurrent to be overlooked. (Fig.4)

Fig. 4. Alejandro Obregón, Estudiante muerto (El velorio), 1956. Oil on Canvas - Collection Museo de Arte de las Américas. Such paradoxes put Gómez Sicre and Marta Traba on the spot. One prime example would be the fact that, in 1956, Obregón’s Estudiante Muerto (El velorio) [The Dead Student (The Vigil)] (1956) was the work brought into the permanent collection of the Pan-American Union gallery. In that painting, Obregón makes explicit reference to the tragic killing of students on June 8 and 9, 1954, during the dictatorship in Colombia. Obregón had been awarded the Guggenheim for that work in 1956, and that may well be why it was purchased by the Pan-American Union. Regardless, it blatantly problematizes the ideas that Gómez Sicre was advocating. It is clear, then, that Gómez Sicre’s readings were, at times, decontextualized; he looked at certain works through the lens of formalisms, thus emptying them of content. To that end, he focused on the fact, pointed out above, that Obregón grappled with structural pictorial problems even in his most political works. In the aforementioned work, for instance, he addressed the theme of the dead

student by means of the still life—painterly resource par excellence—while also making reference to a classic work from art history like Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.21 Marta Traba also had to resort to convoluted rhetoric to distance that painting by Obregón from any possible association with political art. In an article she wrote on the award granted to Obregón’s Estudiante Muerto (El velorio), she wrote:

What the critic can do is tell the viewer beholding Obregón’s paintings that it is useless to look for any resemblance, any connection with nature, with morality, or with history in them. […] But can a work of art be wholly unbound from comparison? Yes, it can and it must stand alone—as if it were placed in a caisson—even if the work resists as Obregón’s painting does. 22

Even though it is earlier than the salons that this text discusses, I have offered this example because of how resoundingly it illustrates the contradictions implicit to the circuit that Gómez Sicre attempted to activate in the salons; it makes patent the inconsistency between the defense of certain aesthetic values and the intention to link those values to artists who, in some cases, contradicted them outright in their works. The solution in the Cartagena and Barranquilla salons was not to talk about specific works, but about the exhibitions as a whole in a vision that insisted on joining together a group of artists on the basis of general descriptions. Emphasis was placed on overlaps that shaped a sort of collective temperament that was thought to incline Latin American artists toward abstraction, and abstraction was associated with a vast range of visual pursuits that—like in the case of Obregon—were not always abstract. The exhibition format was very effective, then, not only because of its ability, as an institution, to provide legitimacy, visibility, and circulation, but also because the exhibition, as Gómez Sicre conceived it, facilitated grouping together artists and works. Differences were smoothed over to emphasize certain traits on the basis of which the idea of Latin American art could be built. Conclusions The inter-American salons, as well as the relationship between artists and art administrators from the Caribbean region of

♯11 second semester 2017

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean… / Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero 149

Colombia and the inter-American network, its prime advocate José Gómez Sicre, and his ally in Colombia, Marta Traba, formed part of an effective strategy for legitimation. On the basis of historiographical accounts, they succeeded in making visible the avant-garde from the Caribbean region of Colombia and in positioning it—and Alejandro Obregón as the artist most representative of the modern avant-garde rupture—as fundamental to the historical processes of modern art in Colombia. The salons were possible thanks to a convergence of interests between, on the one hand, the circuit that was taking shape throughout the continent due, in part, to the efforts of the OAS and, on the other, the work of a group of local artists and intellectuals that had been coming together to further an art institutionalism capable of affording them recognition and legitimacy and of allowing them to work on their art in a professional fashion. Furthermore, the salons and the projects they yielded, like the creation of modern art museums in Cartagena and Barranquilla, ensued alongside processes of modernization in both cities. It was for that reason that cultural projects also enjoyed the backing of certain local elites. Like Gómez Sicre, those elites saw in the salons an opportunity for their cities to occupy a central place in the Americas. Regardless of that convergence of processes and interests, we find that the definition of Latin American art put forth in the salons—a definition that attempted to tie it to a depoliticized formalism and to a sort of hygiene that would liberate Latin America from the legacies of muralism and from the dangers of political art associated with leftist ideas—was not necessary in keeping with what some artists were doing. Along those lines, I cite the specific example of Alejandro Obregón, the emblematic artist of the salons’ project in Colombia. This tension opens up new perspectives from which to examine the works that circulated at the salons and the ones that then formed part of the founding collections of museums of modern art in Cartagena and Barranquilla. Indeed, such reexamination is necessary to attempts to contextualize works and to distance them from the readings formulated at the salons themselves, that is, readings determined to see those works as tight clusters in keeping with a social and political hygiene heralded as the new

state of Latin American art. The organizers of the salons strategically insisted on the idea of the group of works in order to divert attention from what the works and artists themselves had to say. By that means, they fortified a specific idea of modern art.

Traducción: Jane Brodie

N0tes 1 On the creation of museums, see my article “Procesos locales y circuitos transnacionales. El proyecto interamericano y la génesis de los museos de arte moderno de Cartagena y Barranquilla”, written for the book Art Museum of Latin America edited by Gina MacDaniel Tarver and Michel Greet to be published by Routledge in early 2018. 2 A Cuban critic and curator, he was trained in diplomacy and consular law (1939), receiving a PhD degree in social sciences, politics, and economics from the Universidad de la Habana in 1941. Notwithstanding, from an early age he took an interest in art, writing reviews and working in the sphere of cultural administation by organizing and curating shows in Cuba. In 1946, he was named director of the Visual Arts Unit of the Pan-American Union (the OAS Secretariat in Washington). The relevant writings on José Gómez Sicre and OAS are (in chronological order): Shifra Goldman, S., La pintura mexicana en el decenio de la confrontación. 1955-1965, Plural 85, 1978, pp. 33-44; Andrea Giunta, Vanguardia, internacionalismo y política. Arte argentino en los sesenta, Buenos Aires, Paidós, 2001; Michael Wellen, Pan-American Dreams: Art, Politics, and Museum-Making at the OAS, 1948-1976, University of Texas at Austin, PhD dissertation, unpublished, 2012; Claire F. Fox, Making Art Panamerican. Cultural Policy and the Cold War, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2013; Alessandro Armato, “La ‘primera piedra’: José Gómez Sicre y la fundación de los museos interamericanos de arte moderno de Cartagena y Barranquilla” Revista Brasileira do Caribe, XII, 24, pp. 382-404, 2012; Nadia Moreno, Arte y juventud. El salón Esso de artistas jóvenes en Colombia, Bogota, IDARTES, 2013; Alessandro Armato, Estética, política y poder. La influencia de Nelson Rockefeller, el MoMA y la OEA en la construcción de Sao Paulo como foco de irradiación para el arte moderno en Latinoamérica: los casos del MAM-SP y de la bienal (1946-1959), IDAES-USAM, Master Thesis, Historia del Arte Argentino y Latinoamericano, Buenos Aires, unpublished, 2014; William López, “José Gómez Sicre y el origen de una red continental polarizante: impacto en el ámbito colombiano” in María Clara Bernal (Ed.), Redes intelectuales. Arte y política en América Latina, Bogota, Uniandes, 2015, pp. 339-375; Isabel Cristina Ramírez, Arte y modernidad en el Caribe. Procesos locales y circuitos regionales, nacionales y transnacionales de la vanguardia artística costeña, 1940–1963, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogota, PhD Dissertation, unpublished, 2016. 3 Gómez Sicre’s first action in Colombia was to organize the exhibition 32 Artistas de las Américas, held in Bogota

♯11 second semester 2017

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean… / Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero 150

in 1949. For that event, he formed an alliance with the Escuela de Bellas Artes de Bogotá and with the Museo Nacional; he met with Alejandro Obregón, director of the former institution at the time. Gómez Sicre’s relationship with neither the school nor the museum proved lasting, though, and it was not until 1964, with the Salón Intercol de Artistas Jóvenes, that Gómez Sicre once again organized an exhibition in the Colombian capital. His relationship with Alejandro Obregón and his work in the cities of Cartagena and Barranquilla, meanwhile, was constant throughout the forties. 4 José Gómez Sicre, “Para la pintura, el mañana es hoy”, Diario del Caribe newspaper, April 23, 1963. 5 A musician from Cartagena who had studied in Italy and Germany, Guillermo Espinosa was a recognized orchestra conductor in Colombia and throughout Latin America. He conducted the Sinfónica Nacional de Colombia and was the head of the OAS’s Music Unit. He organized a number of cultural initiatives in the city of his birth. 6 Particularly important in that group of intellectuals were the following writers, journalists, and artists: Alejandro Obregón, Cecilia Porras, Enrique Grau, Orlando Rivera, Héctor Rojas Herazo, Gabriel García Márquez, Álvaro Cepeda Samudio, Alfonso Fuenmayor, Germán Vargas, Bernardo Restrepo Maya, Meira del Mar, Néstor Madrid Malo, Sonia Osorio, Eduardo Lemaitre, Aurelio Martínez Canabal, Miguel Sebastián Guerrero, Eric Stern, and Jaime Gómez O’Byrne 7 This period was marked by a great deal of tension between, on the one hand, painters who had been working in the region and who generally defended an artistic tradition based on mimesis and classical European art and, on the other, those who supported modern or new art. 8 In 1959, on the occasion of the Salón Nacional de Cartagena, local critic Eric Stern defended support for national art and rejected regionalist distractions. Notwithstanding, he backed what he viewed as the tendency to defend “material facts that pursue the clear and intentional, and—in all likelihood—very healthy end of combating the dominant voice called centralism”. He went on to say “we don’t want to debate now if painters from the inland are as worthy or less worthy than painters from the coast. We fully agree with the opinion of Gómez O'Byrne when he says that the three paintings by the coastal painters are the best [in the show]. What we don’t agree with is the assertion that it is on the coast that the country’s most forward-looking expression is found”. (Stern, 1959) 9 A private institution created in 1905, the Centro Artístico de Barranquilla brought together different members of the local elite—individuals with social capital, as well as artists, intellectuals, and businessmen—interested in supporting the city’s progress and culture. 10 For the celebration of the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the founding of Barranquilla, a range of initiatives was undertaken and discourses articulated in different publications. A campaign that revolved around restoring Barranquilla’s past glories as supreme Colombian city of progress and civilization was launched. On April 7, the actual day of the anniversary, local newspapers published special editions that upheld the city in those terms. An article entitled “150 años de continuo

progreso” [150 Years of Steady Progress] explained that “the city exercises vast influence on intellectual and cultural spheres”; it recounted the importance, along those lines, of the Centro Artístico de Barranquilla, founded in 1905. In closing, the article described Barranquilla as the “city that has embraced the boldest advances of the modern era while it struggles to rival leading cities; its social and economic position and prestige are almost unmatched in the entire republic”. A few pages later, the article “El futuro de Barranquilla está en construcción” [The Future of Barranquilla is in the Making], which spoke of “billion-peso industrial projects underway”, was illustrated by a reproduction of the model of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Barranquilla whose construction the text announced. (El futuro de Barranquilla está en construcción, 1963). See “El futuro de Barranquilla está en construcción” (unsigned), Diario del Caribe newspaper, April 7, 1963. 11 Andrea Giunta, op. cit.; Alessandro Armato, Estética, política y poder…, op. cit.; William López, op. cit. 12 The following artists, for instance, participated in all three salons: Sarah Grilo (Argentina), Manabu Mabe (Brazil), José Luis Cuevas (Mexico), Armando Morales (Nicaragua), Fernando de Szyszlo (Peru), and Alejandro Obregón, Enrique Grau, Cecilia Porras, and Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar (all from Colombia). 13 Gómez Sicre often described these salons as the most important in the country and, indeed, the continent. He compared them to the São Paulo Biennial and to the Córdoba Biennial in Argentina. 14 Marta Traba, “Un Laurel para Cartagena”, Revista Semana, Bogotá, June 9, 1959. 15 Marta Traba, “La mejor exposición que he visto en Colombia”, El Heraldo, Bogotá, April 12, 1960. 16 Even at the salons’ first versions in the late forties, their coordinators and organizers had made public the intention to eventually turn them into nationwide events that would lead to the creation of museums. Along those lines, Alfonso Fuenmayor, director of cultural affairs for the Department of Cartagena, stated in 1947, “I dream […] about the creation of a Colombian modern art museum, the publication of a monthly magazine as a bulletin of the cultural outreach program, and the expansion to a national scale of the coastal artists’ salon...” (González, 1947). In Rafael González, “Un año de cultura en la Costa. Entrevista a Alfonso Fuenmayor”, El Espectador newspaper, December 24, 1947. 17 Formalist ideas circulated widely in those years and enjoyed the theoretical and critical support of specialists like North American critic Clement Greenberg, as well as backing from institutions like the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York and its long-term director, Alfred Barr. On the basis of a vision of art as autonomous, the formalist stance supported reducing or even doing away with naturalist references to the outside world; pictorial and formal elements were instead the basis for art’s reflection and experimentation. For formalism, the work of art’s intrinsic concerns bore no relationship to concerns of a social, political, or ethical nature. 18 “La exposición latinoamericana de arte moderno fue inaugurada en solemne acto” (unsigned), El Universal newspaper, May 26, 1959.

♯11 second semester 2017

Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean… / Isabel Cristina Ramírez Botero 151

19 The two critics agreed for a specific period; differences later arose between Traba and Gómez, mostly because the gist of Traba’s political and aesthetic thinking changed dramatically starting in the mid-sixties. 20 Alessandro Armato, “José Gómez Sicre y Marta Traba: historias paralelas” in the seminar Synchronicity, Contacts and Divergences in Latin American and US Latino art, Univesity of Texas at Austin, 2012, pp. 118-127. 21 Carmen María Jaramillo, Alejandro Obregón. El mago del Caribe, Bogotá, Asociación de Amigos del Museo Nacional, 2001; Isabel Cristina Ramírez, Geografías Pictóricas. La exploración del espacio en el paisaje de Alejandro Obregón, Bogota, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Colombia, 2013. 22 Marta Traba, “Alejandro Obregón en la Sociedad de Arquitectos” in Marta Traba, Textos escogidos, Bogotá, Colseguros, 2002 [1956], pp. 88-89.

How to correctly cite this article Ramírez Botero, Isabel Cristina; “Latin American Art in the Colombian Caribbean. The Inter-American Modern Art Salons of Cartagena (1959) and Barranquilla (1960 and 1963)”. In caiana. Revista de Historia del Arte y Cultura Visual del Centro Argentino de Investigadores de Arte (CAIA). No 11 | 2nd. semester 2017. Pp 144-151 URL: http://caiana.caia.org.ar/template/caiana.php?pag=articles/article_2.php&obj=289&vol=11 Reception: November 21, 2017 Acceptance: December 14, 2017