Late Pleistocene coastal paleogeography of the Queen Charlotte … · 2020-01-31 · Dan J. Smith,...

Transcript of Late Pleistocene coastal paleogeography of the Queen Charlotte … · 2020-01-31 · Dan J. Smith,...

Can. J. Earth Sci. 40: 1755–1766 (2003) doi: 10.1139/E03-071 © 2003 NRC Canada

1755

Late Pleistocene coastal paleogeography of theQueen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia, Canada,and its implications for terrestrial biogeographyand early postglacial human occupation1

Renée Hetherington, J. Vaughn Barrie, Robert G.B. Reid, Roger MacLeod,Dan J. Smith, Thomas S. James, and Robert Kung

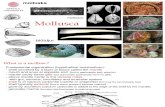

Abstract: Molluscs, sediment lithology, and published sub-bottom profiles are used to deduce sea levels, outline theinfluence of glacially induced crustal displacement, and reconstruct the paleoenvironment of the northeast Pacific lateQuaternary coastline. Geo-spatial modelling shows subaerially exposed land that could have been inhabited by plantsand animals, and also coastally migrating early North American peoples. Ice-free terrain, present by at least 13 790 ±150 14C years BP, a land bridge, and edible molluscs are identified. Queen Charlotte Islands (QCI) late Pleistocenecoastal paleogeography may assist in explaining the biogeography of many terrestrial plant and animal species alongthe broader northeastern Pacific margin and provide evidence for researchers seeking late Pleistocene – early Holoceneglacial refugia. Late Pleistocene – early Holocene coastlines that are not drowned and that may harbour early archaeologicalsites are identified along the western QCI, where migrants probably first travelled and the westernmost British Columbiamainland, where the effects of glacial ice were reduced.

Résumé : Des mollusques, la lithologie des sédiments et des profils publiés du sous-sol du fond sont utilisés pourdéduire les niveaux de la mer, définir l’influence des déplacements de la croûte causés par la glace et reconstruire lepaléoenvironnement de la côte nord-est du Pacifique au Quaternaire tardif. Des modèles géospaciaux montrent des terressubaériennes exposées qui auraient pu être habitées par des plantes et des animaux ainsi que par des peuples nord-américainsprimitifs qui migraient sur la côte. Des terrains libres de glace, présents depuis au moins 13 790 ± 150 14C annéesavant notre ère, un pont terrestre et des mollusques comestibles sont identifiés. La paléogéographie de la côte des îlesde la Reine Charlotte au Pléistocène tardif peut aider à expliquer la biogéographie de plusieurs espèces de plantes etd’animaux terrestres le long de la marge étendue du Pacifique nord-est et fournir des évidences pour les chercheurs quirecherchent des refuges glaciaires au Pléistocène tardif – Holocène précoce. Les côtes du Pléistocène tardif – Holocèneprécoce qui ne sont pas inondées et qui pourraient contenir des sites archéologiques anciens sont identifiés le long desîles de la Reine Charlotte occidentales, vers lesquelles des peuples migrateurs ont probablement tout d’abord voyagé, etsur la partie continentale la plus à l’ouest de la Colombie-Britannique, où les effets de la glace de l’ère glaciaireétaient moindres.

[Traduit par la Rédaction] Hetherington et al. 1766

Introduction

The traditional “Clovis First” (Haynes 1969; West 1981)hypothesis suggests that the first Americans were large gamehunters who migrated from northeast Asia across the Beringianland bridge ca. 12 000 14C years BP, spreading southward

through a continental “ice-free corridor” located east of theCanadian Rockies (Fig. 1). However, research into the timingand extent of Wisconsinan glaciation (White et al. 1985;Lemmen et al. 1994; Dyke 1996; Jackson et al. 1997) precludesthis possibility between 11 500 and 20 000 14C years BP.Further, archaeological finds in North and South America

Received 12 December 2002. Accepted 3 July 2003. Published on the NRC Research Press Web site at http://cjes.nrc.ca on18 December 2003.

Paper handled by Associate Editor J.R. Desloges.

R. Hetherington.2 School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of Victoria, PO Box 3055 STN CSC, Victoria, BC V8W 3P6,Canada.J.V. Barrie, R. MacLeod, T.S. James, and R. Kung. Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada, 9860 W. SaanichRd., PO Box 6000, Sidney, BC V8L 4B2, Canada.R.G.B. Reid. Department of Biology, University of Victoria, PO Box 3055 STN CSC, Victoria, BC, V8W 3P6, Canada.D.J. Smith. Department of Geography, University of Victoria, PO Box 3055 STN CSC, Victoria, BC, V8W 3P6, Canada.

1Geological Survey of Canada Contribution 2002278.2Corresponding author (email: [email protected]).

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:29 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

1756 Can. J. Earth Sci. Vol. 40, 2003

predate 11 500 14C years BP (Sandweiss et al. 1998; Keeferet al. 1998; Dillehay 1989), and, although most remaincontroversial, the Monte Verde site in Chile, dated to at least12 500 14C years BP (Dillehay 1989), is generally accepted asa pre-Clovis site. These findings have led various researchersto propose an alternate migration route for early humans —a water route along Pacific North and South America thatpassed by the Queen Charlotte Islands (QCI), British Columbia(B.C.) (Heusser 1960; Fladmark 1979; Josenhans et al. 1995;Heaton et al. 1996; Fedje and Josenhans 2000; Mandryk etal. 2001; Fig. 1). At present, the earliest archaeological evidencefor human occupation of the B.C.–Alaskan coast is~10 300 14C years BP (Dixon 2001; uncorrected).

The hypothesis that the first peoples of North and SouthAmerica migrated via a coastal route carries with it thepresumption that the QCI region had a suitable climate andsufficient natural resources to make habitation possible. Coastalinhabitants would have been influenced by shifting glacialice, changes in sea level, and migrating coastal zones. Herewe present the temporal and spatial dimensions of the lateQuaternary coastline along the northeast Pacific continentalshelf and ascertain the role that glacially induced crustaldisplacements played in the creation of a viable early coastalmigration route.

The QCI are located 150 km west of mainland B.C. (Fig. 1),across a shallow continental shelf. During the Wisconsinanglaciation the paleogeography of the QCI was noticeablydifferent (Josenhans et al. 1997). Regional paleocoastlineswere markedly influenced by eustasy and glacio-isostaticcrustal adjustments during and subsequent to the last glacialmaximum (LGM). These adjustments varied both temporallyand spatially due to variations in ice thickness, duration ofice coverage, elastic thickness of the lithosphere, and mantleviscosity (Lewis et al. 1991; James et al. 2000), generatingsteep crustal tilting and a rapid crustal response. Subsequentto the LGM, sea level was up to 120 m higher on the B.C.mainland, and more than 150 m lower in the adjacent QCIarchipelago (Clague et al. 1982; Josenhans et al. 1997;Appendix, Table A1; Fig. 2a).

Material, methods, and shellfish biomass

Over 375 geo-referenced 14C dates from raised beach depositsand underwater sediment cores were reviewed from publishedresearch and Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) unpublishedarchive data. Based on this analysis 27 submarine sedimentcores that possessed evidence for constraints on past sealevel were further sampled and analyzed for fauna, flora,radiocarbon datable material, and lithology in the context ofbathymetric, published sub-bottom profiles. An additional23 samples were obtained and analyzed from raised beacheson the QCI, and 65 underwater grab samples were obtainedby H. Josenhans and D. Fedje in 1998 from Juan PerezSound, QCI. Eleven new 14C dates were obtained from thisadditional sampling. In total, 76 samples provided sufficientlywell-constrained sea-level evidence to enable paleocoastlinemodelling for the period 14 250 to 8750 14C years BP(Appendix, Table A1).

The 23 bulk samples collected from high-stand deposits atHaines Creek on Graham Island, and Lockeport estuary, upperArrow Creek, and George Bay on Moresby Island werewet-sieved using 1 and 2 mm screens. Other high-stand datafrom Mary Point and Cape Ball on Graham Island, andMcNeil River, Kitimat, Hirsch Creek, and Port Simpson onthe B.C. mainland were obtained from previous research.Sixty-five underwater grab samples, focusing on fluvial features,river terraces, alluvial fans, and deltas, obtained by H. Josenhans,D. Fedje, and others during a Canadian Coast Guard ShipVector 1998 cruise from Juan Perez Sound, QCI werewet-sieved using 3 and 6 mm mesh. Submarine sedimentcores obtained by the GSC between 1981 and 1995 werereviewed, and those containing lithologies, sedimentarystructures, shell material, or radiocarbon dates of interest(27 cores) were sampled (4 cm3) at regular intervals andscreened using 710 µm (medium sand) or 63 µm (silt – finesand). All sampled cores, underwater grab samples, and raisedbeaches sampled by the principal author, were studied forpaleoecology and 14C datable material. Paleobotanical andfaunal data were collected and identified, and paleohabitatinterpretations were made based on the habitat characteristicsof present marine mollusc and fish species (Hetheringtonand Reid 2003). No additional microfaunal research wasdone, although data and interpretations from previous studiesin the region were incorporated in our findings.

Mollusc species were identified by the primary author on

Fig. 1. Map of study area in Queen Charlotte Islands, Canadawith inset of North America showing traditional migration routein yellow and coastal migration route in red. Localities identified:1, Cape Ball; 2, Cook Bank; 3, Goose Island Bank; 4, Haines Creek;5, Juan Perez Sound; 6, Goose Island Trough; 7, Kitimat; 8, PrinceRupert; 9, Masset; 10, Brooks Peninsula, Vancouver Island.

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:30 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

Hetherington et al. 1757

Fig. 2. (a) Schematic representation of the amount (m) of relative sea-level adjustment in the QCI region. The weight of ice pushedthe mainland down, while adjacent areas were uplifted, forming a peripheral bulge. (b) Net relative sea-level change for the interval12 750 to 13 250 14C years BP, showing change in net relative sea level compared to present elevation in metres (see colour bar). Thewhite line (A–A1) indicates where no net relative sea-level change occurred, as a result of crustal displacement exactly offsettingeustatic sea-level change. Dark blue indicates areas where net relative sea levels were lower than present. Green indicates areas wherenet relative sea levels were higher than present. (c) Isostatic crustal displacement for the interval 12 750 to 13 250 14C years BP, showingchange in crustal elevation relative to present-day elevation in metres (see colour bar). The observed sea-level change at Barbados(Fairbanks 1989) is used as a proxy for eustatic sea-level change. Isostatic crustal displacement was generated by subtracting Barbadossea-level curve (estimated to be between 106 m below mean sea level (msl) at 14 000 14C years BP and 36 m below msl at 9000 14Cyears BP) from relative sea-level observations (Fig. 2b), and taking its negative. The white line (Z–Z1) indicates the line along whichno crustal displacement occurred. Dark blue indicates subsidence under substantial glacial ice within the preceding 1000 years. Red,orange, yellow, and green indicate uplifted areas where little to no ice was present. The yellow line (X–X1) locates the cross-sectionshown in Fig. 2d. (d) A time series of isostatic crustal displacement cross-sections from Dixon Entrance southeast to QC Sound for allmapped intervals showing forebulge position. Greyed lines indicate interpolated and extrapolated data. Glacial ice retreated from DixonEntrance subsequent to 13 750 14C years BP, illustrated by more than 100 m of crustal uplift at northern Hecate Strait (A). Forebulgepersistence in QC Sound and Hecate Strait after 13 750 14C years BP implies continued ice presence on the B.C. mainland until atleast 10 000 14C years BP.

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:34 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

1758 Can. J. Earth Sci. Vol. 40, 2003

the basis of shell exterior, colour, thickness, curvature, fracturepatterns, and comparison with shellfish collections (Univer-sity of Victoria, Victoria, B.C., Parks Canada, and the per-sonal collection of R.G.B. Reid) and standard references(Cornwall 1955; Dunnill 1968; Abbott 1974; Bernard 1979;Morris et al. 1980; Kozloff 1996; Harbo 1997). Shells wereblotted dry and then weighed using an electronic digital sci-entific balance to the nearest 0.1 grams. Edible intertidalmollusc shell weights were multiplied by species specificbiomass factors (Erlandson 1984; Moss 1989) to determineedible biomass levels represented. Selected intertidal mol-lusc specimens were chosen for 14C accelerator mass spec-trometry (AMS) dating.

Radiocarbon dated samples used for paleogeographicreconstruction were restricted to those possessing a clearindication of deposition elevation relative to sea level at thattime. Shells from intertidal molluscan species having narrowdepth tolerances were chosen for 14C AMS dating. To ensureconsistency among dates obtained from a variety of laboratoriesover the last 30 years, the dating methodology was reviewedfor all dates and a marine reservoir correction factor of800 years (Southon et al. 1990; J.J. Clague, personalcommunication, 2001) was applied to all normalized 14Cshell dates.

Molluscs, which are valuable indicators of environmentaland sea-level change, were used with geological data to identifychanges in relative sea levels. Relative sea-level data andgeostatistical interpolation were used to create paleogeographicmaps. Using Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI)GRID® GIS (geographic information system) module, a rastergrid was generated for the study area detailing the trend ofrelative sea-level change for each selected time interval, basedon observations at each sample site. A present-day digitalelevation model was produced from the most current CanadianHydrographic Service bathymetric and National TopographicData Base topographic digital data for the region. Thesegrids were combined to form sum-sea-level and sum-elevationchange models, which depict the net change in relative sealevel and land surface at selected time intervals. Spline-tensioninterpolation was used to infer relative sea-level change infour-dimensional space. The Spline-tension interpolationtechnique requires that the modeled surface pass through alldata points (14C dated sample localities) and possess a minimumsurface curvature. This method permitted tuning of the modelto incorporate a relatively flexible lithosphere, evident in thedivergence of relative sea levels throughout the region as iceand water loading varied during and subsequent to glaciation(Franke 1982; Mitas and Mitasova 1988). The amount oftension applied to the model, which dictated the amount ofcrustal flexure, was varied until a weight parameter of 15was selected. The relatively high weight value of 15 impliesa flexible lithosphere, which is consistent with the divergenceof relative sea-level observations throughout the region as iceand water loading varied during and subsequent to glaciation.

Crustal displacement maps were created by subtractingeustatic sea-level change (Fairbanks 1989) from the relativesea-level change grid and taking its negative. An error in totaleustatic sea level of up to 20 m during maximum glaciationmay be implied when Barbados is compared with other far-fieldsites such as Bonaparte Gulf, Huon Peninsula, and Tahiti(Milne et al. 2002). However, during the interval of this

study 8250 to 14 250 14C years BP, far-field site sea-levelobservations are very similar, with Barbados providing themost extensive data, making the Barbados sea-level curve agood approximation of eustatic sea-level change (Peltier 2002).

Results and discussion

Sea-level change and crustal displacementRelative sea-level maps generated from these data show

the magnitude of sea-level change throughout the region relativeto present (Fig. 2b). Line A–A1 on Fig. 2b indicates zerorelative sea-level change — the point where eustatic sea-levelchange was completely offset by crustal displacement. Isostaticcrustal displacement was isolated by removing global eustaticsea level (Fairbanks 1989) from paleosea-level data. Isostaticcrustal displacement maps illustrate temporal changes in themagnitudes and extent of crustal flexure, relative to presentcrustal elevation, as a glacial forebulge developed (Fig. 2c).

Ice extentGlacial ice attained its maximum extent at �15 500 14C

years BP (Blaise et al. 1990). After �14 000 14C years BP(Hetherington et al. 2003) and prior to 12 650 ± 50 14C years BP(Beta-114465; Appendix, Table A1; Archer 1998) glacial icebegan retreating from eastern Dixon Entrance generating 100 mof rebound (Fig. 2d; Hetherington et al. 2003). Cross-sectionsfrom northwest Dixon Entrance to southeast QC Sound forall mapped intervals indicate that a relatively constant forebulgeelevation persisted between 13 250 and 10 250 14C years BP(Hetherington et al. 2003), implying a fixed ice-front andcontinued ice presence on the B.C. mainland until at least10 000 14C years BP (Clague et al. 1982; Hetherington et al.2003). By 12 650 ± 50 14C years BP (Beta-114465; Archer1998) Dixon Entrance was ice-free, providing clear navigationeast to the B.C. mainland, where edible molluscs Tresusnuttallii, Clinocardium nuttallii, Saxidomus giganteus, andMytilus sp. colonized a productive gravel beach.

Paleogeographic reconstructionsLowered eustatic sea level combined with crustal uplift

permitted terrestrial conditions to develop on two emergentcoastal plains; one extended eastward from the QCI and theother developed in QC Sound extending northward fromVancouver Island (Fig. 3a). Terrestrial plant material fromDogfish Bank and Cape Ball (Appendix, Table A1; TO-3738;GSC-3222) suggest that a treeless, tundra-like environmentextended east from QCI from at least 13 790 ± 150 14C years BP(TO-3738; Clague et al. 1982; Mathewes 1989; Barrie et al.1993). Eighteen submarine sediment cores from Hecate Straitand Dixon Entrance and highstand deposits at Cape Ballindicate the subaerial exposure of this now-drowned north-eastern coastal plain until at least 9130 ± 90 14C years BP(TO-9307, Appendix, Table A1). Molluscan and sedimentologicalevidence (Appendix, Table A1) indicates that lowered eustaticsea level combined with isostatic uplift resulted in the subaerialexposure of a southern coastal plain (Fig. 3a) from 15 200 ±490 14C years BP (GSC-3746; Luternauer et al. 1989a).Nineteen samples were recovered from submarine sedimentcores, terrestrial, or intertidal beach deposits in the QC Soundand Cook Bank region (Appendix, Table A1) and imply per-sistence of the southern coastal plain until 9810 ± 80 14C

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:34 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

Hetherington et al. 1759

years BP (TO-1256; Clague et al. 1982; Luternauer et al.1989a; Barrie and Conway 2002) or perhaps as late as 7820 ±70 14C years BP (TO-4362).

Downwasting of ice to the north and east resulted in isostaticuplift, and, despite rising eustatic sea levels, northern HecateStrait closed by �11 750 14C years BP (Fig. 3b), creating anarrow, elongate, shallow-water embayment (the Hecate Sea;Patterson et al. 1995) that opened southward into QC Sound.The resulting land bridge connected the B.C. mainland andthe QCI, facilitating faunal, floral, and potential land-basedhuman migration. Separation of Hecate Sea from the openmarine waters of Dixon Entrance and fresh water from melting

glacial ice likely led to a reduction in salinity and sea-surfacetemperature in Hecate Sea.

Implications for terrestrial biogeographyThe late Pleistocene coastal paleogeography of the QCI

has implications for the biogeography of many terrestrialplant and animal species along the broader northeastern Pacificmargin and provides evidence for researchers seeking latePleistocene – early Holocene glacial refugia (McCabe andCowan 1945; Foster 1965; Calder and Taylor 1968; Warneret al. 1982; Hebda et al. 1997; Ogilvie 1989, 1997; Reimchen1994; Byun et al. 1997; Byun 1999). QCI late Pleistocene

Fig. 3. (a)Paleogeography of QCI region between 12 750 and 13 250 14C years BP. (b) Paleogeography of QCI region between 11 250and 11 750 14C years BP. (c) Paleocoastlines persisting from 10 250 to 12 750 14C years BP that intersect present subaerial topographyshown in red. Westernmost paleocoastlines along the B.C. mainland are less likely to have been influenced by glacial ice than moreinland sites. (d) Paleocoastlines persisting from 12 750 to �14 250 14C years BP that intersect present topography shown in red.Paleocoastlines located along the west coast of QCI provide the greatest archaeological site potential. Dixon Entrance would have beenice-free only late in this time interval. Westernmost paleocoastlines along the B.C. mainland are less likely to have been influenced byglacial ice than more inland sites.

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:39 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

coastal paleogeography may assist in explaining the survivaland migration of the large number of QCI endemic andwidely disjunct species found on Brooks Peninsula, northernVancouver Island, B.C. (Fig. 1). For instance, Hebda et al.(1997, p. 15.3) suggests that the character of high-elevationplant communities on the Brooks Peninsula “clearly resemblethose on the QCI and scattered sites on the central coast ofB.C.” Ogilvie (1997, p. 5.37) found that the Brooks Peninsulavascular flora, though impoverished, are rich in rare speciesand are of diverse affinities. He discovered nine taxa onBrooks Peninsula that were previously known only as endemicson the QCI (Ogilvie 1997, p. 5.1). Ligusticum calderi, arestricted oceanic pine tree species that is not adapted forlong distance dispersal, is present in early deglaciationvegetation on Brooks Peninsula (Hebda 1997, p. 9.40).Further, Chinnappa (1997, p. 6.7) found that the chromo-some numbers of Ligusticum calderi from Brooks Peninsulaand the QCI agree and both are endemic to the two areas.Warner et al. (1982) suggest that plant macrofossil evidencefrom Cape Ball, QCI indicates a well established flora by16 000 years BP and implies the presence of glacial refugiaon mountain nunatuks or on a submerged coastal “platform”in Hecate Strait. In addition, Nagorsen and Keddie (2002)recovered 12 000-year-old mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus)skeletal remains from two caves on northern VancouverIsland, implying the presence of ice-free conditions and thepersistence of ice-free refugia on the continental shelf. QCIregion paleogeographic reconstructions show the presence ofexposed coastal plains on the continental shelf and thedevelopment of a land bridge and a narrow Hecate Sea,which may have facilitated the migration of terrestrial andanimal species between the QCI and Vancouver Island. Upliftedcoastal plains may have acted as migrating coastal refugiafor early floral, faunal, and potentially human populations.

Paleoenvironment and Younger DryasThe appearance of the bivalve molluscs Serripes groenlandicus

and Clinocardium ciliatum (Appendix, Table A1) signify theonset of a short interval 10 900 ± 50 14C years BP (CAMS-48155; Fedje and Josenhans 2000) to 10 260 ± 80 14C years BP(RIDDL (E87A22-87); Barrie and Conway 2002), of cool(maximum < 9 �C) sea-surface temperatures around thesouthern limits of Hecate Sea and Cook Bank. Sea-surfacecooling is supported by paleooceanographic studies (Patterson1993; Patterson et al. 1995) and palynological evidence(Mathewes 1993) of the late-glacial Younger Dryas coolingevent between 10 700 and 10 000 14C years BP in the QCIand southeastern Alaska (Engstrom et al. 1990). During thistime, sea-surface temperatures at Goose Island Bank remainedtemperate, perhaps due to strong vertical tidal mixing in thepresence of reduced coastal run-off and reduced upwelling inGoose Island Trough (R.E. Thomson, personal communication,2002). Malacological evidence indicates temperate sea-surfaceconditions reappeared in Juan Perez Sound, southern MoresbyIsland, by 10 190 ± 40 14C years BP (CAMS-49629; Fedjeand Josenhans 2000) and in Cook Bank by 9940 ± 75 14Cyears BP (RIDDL-979; Luternauer et al. 1989b).

Edible resources and productivity of the intertidal zoneCritical to ascertaining productive early coastal zones is

the identification of edible molluscs, which potentially represent

an important subsistence resource for people. By edible, werefer to those species having sufficient size to be worth theeffort of collecting and those species recorded as havingbeen used by early peoples (Quayle and Bourne 1972; Ellisand Swan 1981; Ellis and Wilson 1981; Erlandson 1984;Harbo 1997). Edible species first appear in submarine sedimentcores from Hecate Strait and QC Sound at 13 220 ± 80(TO-1335) and 13 210 ± 150 14C years BP (GSC-3711;Luternauer et al. 1989a), respectively. A Clupea harenguspallasi (edible Pacific Herring) caudal vertebrae and a sculpin,possibly Gymnocanthus (Cottidae), pre-operculum spine werefound overlying intertidal samples dating to 13 210 ± 15014C years BP (GSC-3711; Luternauer et al. 1989a). Thebivalve molluscs Macoma nasuta and Mytilus trossulus werethe first to recolonize after ice retreat, a function of theirability to withstand low sea-surface temperatures and highsediment influx. Edible bivalve molluscs Saxidomus giganteus,Tresus nuttallii, Clinocardium nuttallii, and Simomactra falcataappeared shortly afterward. The total edible biomass representedin samples from southern Moresby Island, Haines Creek,and Juan Perez Sound, dating between 8020 14C years BP(Hetherington and Reid 2003) and 11 150 ± 50 14C years BP(CAMS-47674; Hetherington and Reid 2003), comparefavorably with commercially viable modern beaches in theQCI and southern B.C., which sustain an annual average ediblebiomass harvest (Saxidomus giganteus) of between 1085 and5425 g/m3 (Quayle and Bourne 1972). A decline of edibleintertidal biomass is recorded in Juan Perez Sound between10 900 ± 50 (CAMS-48155; Fedje and Josenhans 2000) and10 100 ± 80 14C years BP (CAMS-9992; Josenhans et al.1995), coincident with cooler sea-surface temperatures(Hetherington 2002; Hetherington and Reid 2003).

Dispersal routesHumans were impeded from travelling through northern QCI

and Dixon Entrance until sometime after 14 000 14C years BPbecause of presence of ice (Hetherington et al. 2003). Priorto this, any migrants would have had to skirt the outer QCI,where limited evidence (Barrie and Conway 2002) indicateslowered sea level. Although glacial ice was present, and inplaces extremely thick (Clague et al. 1982, Clague 1983),ice-free conditions persisted on two coastal plains, and openocean conditions were present from at least �13 220 14Cyears BP (TO-1335) in Hecate Strait, and 12 650 ± 50 14Cyears BP (Beta-114465; Archer 1998) in Dixon Entrance(Fig. 3a). Edible molluscs, quick to recolonize once sedimentationrates and sea-surface temperatures were conducive and pelagicmarine fish, such as herring Clupea harengus pallasi, andpotentially other edible fish and sea mammals were availableto provide subsistence resources for potential inhabitants.Between �11 750 and �10 750 14C years BP, an emergentland bridge required any migrants to travel along the upliftedwest coast of QCI or to traverse overland (Fig. 3b). Between10 900 ± 50 14C years BP (CAMS-48155; Fedje and Josenhans2000) and 10 260 ± 80 14C years BP (RIDDL (E87A22-87);Barrie and Conway 2002), cooler sea-surface temperaturesreduced edible molluscan biomass (Hetherington 2002;Hetherington and Reid 2003) in the Hecate Sea, potentiallyrequiring people to migrate greater distances to collect coastalresources and increase their reliance on land-based resources.It should be noted that the coarse resolution of the radiocarbon

1760 Can. J. Earth Sci. Vol. 40, 2003

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:39 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

dating does not preclude changes in biogeography and resourcepotential within mapped intervals, which may have allowedshort periods of rapid human migration not necessarily capturedin the current model. For example, during the interval whenthe land bridge persisted, additional resources may haveincreased the potential of habitation.

Potential early habitable landscapesNumerous resource-rich coastal zones and estuaries in Hecate

Strait and QC Sound have been cored and dated (Appendix,Table A1), and although these would make excellent potentialearly habitable landscapes, they are now drowned and difficultto access. Identification of potential early habitable landscapesthat are not drowned would aid future archaeological investi-gations. The intersection between paleocoastlines obtainedfrom paleogeographic reconstruction maps (see Figs. 3a, 3b)and present-day subaerial topography gives the location ofsuch habitable landscapes where possible early archaeologicalsites may be located. Figures 3c and 3d illustrate the locationsof accessible paleocoastlines that persisted throughout theperiod �12 750 to 10 250 14C years BP and between �14 250and 12 750 14C years BP, respectively. Paleocoastlines ofparticular archaeological interest lie along the west coast ofQCI, where migrants probably first traveled, and the western-most sites along the B.C. mainland, where the effects of glacialice are reduced. Paleocoastlines that appear on both Figs. 3cand 3d persisted from �14 250 to 10 250 14C years BP, offeringthe greatest opportunity for long-term colonization andarchaeological site visibility.

Conclusions

The paleogeographic and paleoenvironmental reconstructionsas determined in this study are of special importance becausethey provide evidence of ice-free subaerially exposed productivehabitat that could have been inhabited by plants, animals,and humans by at least 13 790 ± 150 14C years BP (TO-3738;Barrie et al. 1993). Paleoreconstructions indicate that coastalmigrants were likely impeded from migrating through northernQCI and Dixon Entrance until sometime after 14 000 14Cyears BP, due to the presence of ice. Prior to this time, anyearly coastal migrants would have had to have skirted thewest coast of QCI. Paleogeographic reconstruction mapsestimate the location of potential and accessible early (priorto 10 000 14C years BP) coastal locales where archaeologicalsites may be sought. Paleocoastlines of particular archaeo-logical interest lie along the west coast of QCI, where earlymigrants probably first traveled, and along the westernmostB.C. mainland, where the effects of glacial ice were reduced.The presence of a land bridge and reduced coastal zone pro-ductivity during a Younger Dryas interval between 10 900 ±50 14C years BP (CAMS-48155; Fedje and Josenhans 2000)and 10 260 ± 80 14C years BP (RIDDL (E87A22-87); Barrieand Conway 2002) potentially altered migration and habitatconditions, forcing early peoples to migrate greater distancesto collect coastal resources and (or) increase their relianceon land-based resources. Confirmation of these findings mustawait future archaeological survey. Paleoreconstruction accuracywould benefit from further well-constrained sea-level obser-vation data, particularly along the southern B.C. mainland.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the followingindividuals for their contribution to this paper. Cartography:Richard Franklin, Parm Dhesi, and Patrick Bartier. Fieldworkand dating support: Jim Haggart and Daryl Fedje. Invertebrateidentification: Phil Lambert. Fish identification: Becky Wigen,Pacific Identification Company, and Cindy Wright. Libraryresearch: Pam Olsen. Oceanography: Richard E. Thomson,Jean-Pierre Guilbault, Joe Linguanti, and Roy Hourston.Geology and paleoenvironment: John Clague, Kim Conway,and Rolf Mathewes. Geophysics: Roy Hyndman and KristinRohr. Global Positioning System (GPS) measurements: CarmelLowe. We appreciate early reviews by Kim Conway (GSC),Ralph Currie (GSC), and Daryl Fedje (Parks Canada), andcontributions by one anonymous reviewer, and the thoughtfulreviews by J. Desloges and Alwynne Beaudoin (ProvincialMuseum of Alberta, Edmonton), which contributed greatlyto the improvement of this paper. Research funding has beengenerously provided by the GSC, University of Victoria,Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada,Parks Canada, The Ord, and Linda Anderson InterdisciplinaryScholarship fund. This paper is a contribution to UNESCOand the International Geological Correlation Program, ProjectNo. 464.

References

Abbott, R.T. 1974. 2nd ed. American Sea Shells: the Marine Mol-luscs of the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts of North America. VanNostrand Reinhold Co., New York.

Archer, D.J.W. 1998. Early Holocene landscapes on the north coastof B.C. Canadian Archaeological Association, 31st annual meeting,Victoria, B.C., Abstracts, p. 34.

Barrie, J.V., and Conway, K.W. 2002. Rapid sea level change andcoastal evolution on the Pacific margin of Canada. Journal ofSedimentary Geology, 150: 171–183.

Barrie, J.V., Conway, K.W., Mathewes, R.W., Josenhans, H.W., andJohns, M.J. 1993. Submerged Late Quaternary terrestrial depositsand paleoenvironment of northern Hecate Strait, British Columbiacontinental shelf, Canada. Quaternary International, 20: 123–129.

Bernard, F.R. 1979. Bivalve Mollusks of the Western Beaufort Sea.Contributions in Science, Natural History Museum of Los AngelesCounty, Los Angeles, Calif.

Blaise, B., Clague, J.J., and Mathewes, R.W. 1990. Time of maximumLate Wisconsin glaciation, west coast of Canada. QuaternaryResearch, 34: 282–295.

Byun, S.A. 1999. Quaternary biogeography: Insights from mtDNAphylogeography of endemic vertebrates from Haida Gwaii. Ph.D.thesis, University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C.

Byun, S.A., Koop, B.F., and Reimchen, T.E. 1997. North Americanblack bear mtDNA phylogeography: Implications for morphologyand the Haida Gwaii glacial refugium controversy. Evolution,51: 1647–1653.

Calder, J.A., and Taylor, R.L. 1968. Flora of the Queen CharlotteIslands, Part 1. Systematics of the vascular plants. ResearchBranch, Canada Department of Agriculture, Monograph 4, Queen’sPrinter, Ottawa, Ont.

Chinnappa, C.C. 1997. Cytogeographic studies on the vascular plantsof Brooks Peninsula. In Brooks Peninsula: an ice age refugiumon Vancouver Island. Occasional Paper No. 5. Edited by R.J.Hebda and J.C. Haggarty. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria, B.C.,pp. 6.1–6.7.

Hetherington et al. 1761

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:39 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

1762 Can. J. Earth Sci. Vol. 40, 2003

Clague, J.J. 1983. Glacio-isostatic effects of the Cordilleran IceSheet, British Columbia, Canada. In Shorelines and isostasy.Edited by D.E. Smith and A.G. Dawson. Institute of BritishGeographers, Special Publication 16, Academic Press, London,pp. 321–343.

Clague, J.J., Harper, J.R., Hebda, R.J., and Howes, D.E. 1982. LateQuaternary sea levels and crustal movements, coastal BritishColumbia. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 19: 597–618.

Cornwall, I.E. 1955. Canadian Pacific Fauna, 10. Arthropoda, 10e.Cirripedia. Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Ottawa, Ont.,pp. 22–40.

Dillehay, T.D. 1989. Monte Verde: A Late Pleistocene Settlementin Chile. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Dixon, E.J. 2001. Human colonization of the Americas: timing,technology and process. Quaternary Science Reviews, 20: 277–299.

Dunnill, R.M. 1968. A taxonomic and ecological investigation ofthe genus Macoma (Pelecypoda) in southern British Columbia.M.Sc. thesis, University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C.

Dyke, A.S. 1996. Preliminary paleogeographic maps of glaciatedNorth America. Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 3296.

Ellis, D.W., and Swan, L. 1981. Teaching of the Tides: Uses of Ma-rine Invertebrates by the Manhousat People. Theytus Books,Nanaimo, B.C.

Ellis, D.W., and Wilson, S. 1981. The Knowledge and Usage of Ma-rine Invertebrates by the Skidegate Haida People of the QueenCharlotte Islands. Queen Charlotte Islands Museum Society,Skidegate, B.C.

Engstrom, D.R., Hansen, B.C.S., and Wright, H.E., Jr. 1990. Apossible Younger Dryas record in southwestern Alaska. Science,250: 1383–1385.

Erlandson, J.M. 1984. Faunal analysis of the invertebrate assemblage.In The Hidden Falls Site, Baranof Island, Alaska. Edited by S.D.Davis. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service,Sitka, pp. 151–179.

Fairbanks, R.G. 1989. A 17,000-year glacio-eustatic sea level record:influence of glacial melting rates on the Younger Dryas eventand deep-ocean circulation. Nature, 342: 637–642.

Fedje, D.W., and Josenhans, H. 2000. Drowned forests and archaeologyon the continental shelf of British Columbia, Canada. Geology,28: 99–102.

Fladmark, K.R. 1979. Routes: alternate migration corridors for earlyman in North America. American Antiquity, 44: 55–69.

Foster, J.B. 1965. The evolution of the mammals of the QueenCharlotte Islands, British Columbia. Occasional papers of theBritish Columbia Museum, Victoria, B.C., Paper 14.

Franke, R. 1982. Smooth interpolation of scattered data by localthin plate splines. Computers and Mathematics with Applications,8: 237–281.

Harbo, R.M. 1997. Shells and Shellfish of the Pacific Northwest: AField Guide. Harbour Publishing, Madeira Park, B.C.

Haynes, C.V., Jr. 1969. The earliest Americans. Science, 166: 709–715.Heaton, T.H., Talbot, S.L., and Shields, G.F. 1996. An ice age

refugium for large mammals in the Alexander Archipelago,southeastern Alaska. Quaternary Research, 46: 186–192.

Hebda, R.J. 1997. Late Quaternary paleoecology of Brooks Peninsula.In Brooks Peninsula: An Ice Age Refugium on Vancouver Is-land. Occasional Paper No. 5. Edited by R.J. Hebda and J.C.Haggarty. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria, B.C., pp. 9.1–9.48.

Hebda, R.J., Howes, D., and Maxwell, B. 1997. Brooks Peninsulaas an ice age refugium. In Brooks Peninsula: An Ice Age Refugiumon Vancouver Island. Occasional Paper No. 5. Edited by R.J.Hebda and J.C. Haggarty. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria, B.C.,pp. 15.1–15.7.

Hetherington, R. 2002. Interdisciplinary Insights into Paleo-

Environments of the Queen Charlotte Islands/Hecate StraitRegion. Ph.D. thesis, University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C.

Hetherington, R., and Reid, R.G.B. 2003. Malacological insights intothe marine ecology and changing climate of the late Pleistocene –early Holocene Queen Charlotte Islands archipelago, westernCanada, and implications for early peoples. Canadian Journal ofZoology, 81: 626–661.

Hetherington, R. Barrie, J.V., Reid, R.G.B., MacLeod, R., and Smith,D.J. 2003. Paleogeography, glacially-induced crustal displacement,and Late Quaternary coastlines on the continental shelf of BritishColumbia, Canada. Quaternary Science Reviews. In press.

Heusser, C.J. 1960. Late Pleistocene environments of Pacific NorthAmerica. American Geological Society, Special Publication 35.

Jackson, L.E., Jr., Phillips, F.M., Shimamura, K., and Little, E.C.1997. Cosmogenic 36Cl dating of the Foothills erratics train, Alberta,Canada. Geology, 25: 195–198.

James, T.S., Clague, J.J., Wang, K., and Hutchinson, I. 2000.Postglacial rebound at the northern Cascadia subduction zone.Quaternary Science Reviews, 19: 1527–1541.

Josenhans, H.W., Fedje, D.W., Conway, K.W., and Barrie, J.V.1995. Post glacial sea levels on the western Canadian continentalshelf: evidence for rapid change, extensive subaerial exposure,and early human habitation. Marine Geology, 125: 73–94.

Josenhans, H.W., Fedje, D.W., Pienitz, R., and Southon, J. 1997.Early humans and rapidly changing Holocene sea levels in theQueen Charlotte Islands – Hecate Strait, British Columbia, Canada.Science, 277: 71–74.

Keefer, D.K., deFrance, S.D., Moseley, M.E., Richardson, III J.B.,Satterlee, D.R., and Day-Lewis, A. 1998. Early maritime economyand El Niño events at Quebrada Tacahuay, Peru. Science, 281:1833–1835.

Kozloff, E.N. 1996. Marine Invertebrates of the Pacific Northwest.University of Washington Press, Seattle, Wash.

Lemmen, D.S., Duk-Rodkin, A., and Bednarski, J.M. 1994. Lateglacial drainage systems along the northwestern margin of theLaurentide ice sheet. Quaternary Science Reviews, 13: 805–828.

Lewis, T.J., Bentkowski, W.H., and Wright, J.A. 1991. Thermalstate of the Queen Charlotte Basin, British Columbia: warm. InEvolution and Hydrocarbon Potential of the Queen Charlotte Ba-sin, British Columbia. Geological Survey of Canada, Paper 90-10, pp. 489–506.

Luternauer, J.L., Clague, J.J., Conway, K.W., Barrie, J.V., Blaise,B., and Mathewes, R.W. 1989a. Late Pleistocene terrestrial depositson the continental shelf of western Canada: evidence for rapidsea-level change at the end of the last glaciation. Geology, 17:357–360.

Luternauer, J.L., Conway, K.W., Clague, J.J., and Blaise, B. 1989b.Late Quaternary geology and geochronology of the centralcontinental shelf of western Canada. Marine Geology, 89: 57–68.

Mandryk, C.A.S., Josenhans, H.W., Fedje, D.W., and Mathewes,R.W. 2001. Late Quaternary paleoenvironments of NorthwesternNorth America: implications for inland versus coastal migrationroutes. Quaternary Science Reviews, 20: 301–314.

Mathewes, R.W. 1989. Paleobotany of the Queen Charlotte Islands.In The Outer Shores. Edited by G.G.E. Scudder and N. Gessler.Queen Charlotte Islands Museum Press British Columbia, Skidegate,B.C., pp. 75–90.

Mathewes, R.W. 1993. Evidence for Younger Dryas-Age coolingon the north Pacific coast of America. Quaternary Science Reviews,12: 321–331.

McCabe, T.T., and Cowan, I.M. 1945. Peromyscus maniculatusmacrorhinus and the problem of insularity. Transactions of theRoyal Canadian Institute, 25: 17–215.

Milne, G.A., Mitrovica, J.X., and Schrag, D.P. 2002. Estimating

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:39 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

Hetherington et al. 1763

past continental ice volume from sea-level data. Quaternary ScienceReviews, 21: 361–376.

Mitas, L., and Mitasova, H. 1988. General variational approach tothe interpolation problem. Computers and Mathematics withApplications, 16: 983–992.

Morris, R.H., Abbott, D.P., and Haderlie, E.C. 1980. Intertidalinvertebrates of California. Stanford University Press, Stanford,Calif.

Moss, M.L. 1989. Archaeology and Cultural Ecology of the Prehis-toric Angoon Tlingit. Ph.D. thesis, University of California,Santa Barbara, Calif.

Nagorsen, D.W., and Keddie, G. 2002. Late Pleistocene mountaingoats (Oreamnos americanus) from Vancouver Island: bio-geographic implications. Journal of Mammology, 81: 666–675.

Ogilvie, R.T. 1989. Disjunct vascular flora of northwestern VancouverIsland in relation to Queen Charlotte Islands’ endemism and Pacificcoast refugia. In The Outer Shores. Edited by G.G.E. Scudderand N. Gessler. Queen Charlotte Islands Museum Press, Skidegate,B.C., pp. 127–130.

Ogilvie, R.T. 1997. Vascular Plants and Phytogeography of BrooksPeninsula. In Brooks Peninsula: An Ice Age Refugium onVancouver Island. Occasional Paper No. 5. Edited by R.J.Hebda and J.C. Haggarty. Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria, B.C.,pp. 5.1–5.48.

Patterson, R.T. 1993. Late Quaternary benthic foraminiferal biofaciesand paleoceanography of Queen Charlotte Sound and southernHecate Strait, British Columbia. Journal of Foraminiferal Research,23: 1–18.

Patterson, R.T., Guilbault J-P., Thomson R.E., and Luternauer, J.L.1995. Foraminiferal evidence of Younger Dryas age cooling on

the British Columbia shelf. Géographie physique et Quaternaire,49: 409–428.

Peltier, W.R. 2002. On eustatic sea level history: Last GlacialMaximum to Holocene. Quaternary Science Reviews 21: 377–396.

Quayle, D.B., and Bourne, N. 1972. The Clam Fisheries of BritishColumbia. Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin, 179.

Reimchen, T.E. 1994. Predators and evolution in threespine stickleback.In Evolution of the Threespine Stickleback. Edited by M.A. Belland S.A. Foster. Oxford University Press, Oxford, U.K., pp. 240–273.

Sandweiss, D.H., McInnis, H., Burger, R.L., Cano, A., Ojeda, B.,Paredes, R., Sandweiss, M. del C., and Glascock, M.D. 1998.Quebrada Jaguay: early South American maritime adaptations.Science, 281:1830–1832.

Southon, J.R., Nelson, D.E., and Vogel, J.S. 1990. A record of pastocean-atmosphere radiocarbon differences from the northeast Pacific.Paleoceanography, 5: 197–206.

Warner, B.G., Mathewes, R.W., and Clague, J.J. 1982. Ice-freeconditions of the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia, atthe Height of Late Wisconsinan glaciation. Science, 218: 675–677.

West, F.H. 1981. The Archaeology of Beringia. Columbia UniversityPress, New York.

White, J.M., Mathewes, R.W., and Mathews, W.H. 1985. LatePleistocene chronology and environment of the ‘ice free corridor’of northwestern Alberta. Quaternary Research, 24: 173–186.

Appendix

Appendix appears on the following page.

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:40 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

1764 Can. J. Earth Sci. Vol. 40, 2003

Lab

No.

(Sam

ple

No.

)L

ongi

tude

(dec

imal

°)L

atit

ude

(dec

imal

°)L

ocat

ion

Pre

sent

elev

atio

n(m

)M

RC

14C

date

Unc

erta

inty

(yea

rs)

Ref

.M

ater

ial

date

d

Sea

-sur

face

Tem

pera

ture

(°C

)E

nvir

onm

ent

ofde

posi

tion

TO

-436

2–1

29.7

952

.05

QC

Sou

nd–1

0978

2070

*Te

rres

tria

lor

gani

csn/

aT

?G

SC

-234

3–1

29.9

854

.21

McN

eil

Riv

er–4

8790

150

1@

Cli

noca

rdiu

mnu

ttal

lii

n/a

SM

/IT

O-9

312

–131

.46

52.4

6U

pper

Arr

owC

reek

688

0070

*@

Pro

toth

aca

stam

inea

+4

to+

14I/

fres

hw

ater

infl

uxC

AM

S-1

8999

–131

.45

52.4

6A

rrow

Cre

ek12

8850

702

spru

cene

edle

n/a

SM

CA

MS

-625

37–1

33.1

053

.94

Hai

nes

Cre

ek2

9000

50*

%A

cmae

am

itra

+4

to+

14S

M/p

rote

cted

oute

rco

ast

TO

-930

7–1

30.5

952

.97

Hec

ate

Str

ait

–118

9130

90*

%O

live

lla

baet

ica

+1

to+

25I/

estu

ary

GS

C-3

129

–131

.88

53.7

0C

ape

Bal

lR

iver

791

6090

3§

Abi

essp

.n/

aT

RID

DL

-121

1–1

32.5

754

.05

Mar

yP

oint

Loc

atio

nB

891

7011

04

@Sa

xido

mus

giga

nteu

s+

2to

+21

I/es

tuar

yT

O-9

306

–130

.59

52.9

7H

ecat

eS

trai

t–1

1892

0010

0*

@Sa

xido

mus

giga

nteu

sn/

aI/

estu

ary

GS

C-2

425

–128

.64

54.1

0K

itim

atR

iver

3093

0090

1,3

Con

ifer

ous

woo

dn/

aS

M/d

elta

CA

MS

-108

36–1

31.4

752

.46

Mat

heso

nIn

let

–27

9350

605

@Po

dode

smus

mac

hroc

hism

a–2

to+

14I

RID

DL

-120

5–1

32.5

754

.05

Mar

yP

oint

Loc

atio

nB

894

6013

04

@Sa

xido

mus

giga

nteu

s+

2to

+21

I/es

tuar

yT

O-4

889

–131

.12

53.6

0H

ecat

eS

trai

t–6

894

8070

*W

ood

+4

to+

17I

CA

MS

-108

34–1

31.4

752

.46

Mat

heso

nIn

let

–27

9550

705

@Po

dode

smus

mac

hroc

hism

a–2

to+

14I

TO

-489

0–1

31.1

253

.60

Hec

ate

Str

ait

–68

9660

70*

Woo

d+

4to

+17

IC

AM

S-1

0835

–131

.47

52.4

6M

athe

son

Inle

t–2

796

8080

5@

Podo

desm

usm

achr

ochi

sma

–2to

+14

I

GS

C-2

492

–128

.60

54.0

5H

irsc

hC

reek

9897

1016

01

@M

yatr

unca

tan/

aI

TO

-129

6–1

30.5

952

.97

Hec

ate

Str

ait

–118

9720

70*

%O

live

lla

sp.

+1

to+

25I

TO

-440

5–1

32.0

154

.21

Dix

onE

ntra

nce

–96

9770

906

$A

rthr

opod

a,ci

rrip

edia

n/a

SM

/dro

wne

dsp

itC

AM

S-1

0837

–131

.47

52.4

6M

athe

son

Inle

t–2

798

1060

5@

Myt

ilus

sp.

–2to

+14

IT

O-1

256

–129

.19

51.8

7G

oose

Isla

ndB

ank

–121

9810

a80

6@

Spis

ula

falc

ata

+4

to+

24I

TO

-174

–128

.49

51.4

9G

oose

Isla

ndT

roug

h–1

9298

4012

07

$B

alan

usgl

andu

lus

+3

to+

12I/

quie

tba

yT

O-1

337

–130

.53

53.0

2H

ecat

eS

trai

t–1

1198

5070

*@

Mod

iolu

sre

ctus

n/a

IT

O-3

737

–132

.13

54.1

2D

ixon

Ent

ranc

e–3

398

6070

*U

nide

ntif

ied

mar

ine

biva

lve

n/a

I

RID

DL

-979

–128

.44

51.0

0C

ook

Ban

k–9

499

4075

8Te

rres

tria

lpe

at+

3to

+18

I/ex

pose

dT

O-1

73–1

29.5

151

.24

Out

erG

oose

Isla

ndT

roug

h–2

8410

010

807

@N

ucul

ana

cell

ulit

a–1

to+

14S

M/s

ubti

dal

CA

MS

-999

2–1

31.4

752

.46

Mat

heso

nIn

let

–27

1010

080

5@

Myt

ilus

sp.

n/a

SM

/bra

ckis

hC

AM

S-4

9628

–131

.46

52.4

9Ju

anP

erez

Sou

nd–5

510

140

4010

@Sa

xido

mus

giga

nteu

sn/

aI

CA

MS

-496

29–1

31.4

152

.45

Juan

Per

ezS

ound

–65

1019

040

10@

Saxi

dom

usgi

gant

eus

+2

to+

14I

GS

C-3

159

–131

.88

53.7

4C

ape

Bal

l5

1020

090

3Te

rres

tria

lpe

atn/

aT

RID

DL

(E87

A22

-87)

–128

.52

50.9

5C

ook

Ban

k–1

0410

260

806

Uni

dent

ifie

dm

arin

ebi

valv

e–1

to+

6I/

cool

RID

DL

-983

–128

.44

51.0

0C

ook

Ban

k–9

410

290

808

Woo

d+

1to

+9

SM

/hea

vysu

rf

Tab

leA

1.R

adio

carb

onda

tes

and

inte

rpre

tati

ons

for

Que

enC

harl

otte

Isla

nds

regi

on,

Can

ada.

Ap

pe

nd

ix

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:40 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

Hetherington et al. 1765

Lab

No.

(Sam

ple

No.

)L

ongi

tude

(dec

imal

°)L

atit

ude

(dec

imal

°)L

ocat

ion

Pre

sent

elev

atio

n(m

)M

RC

14C

date

Unc

erta

inty

(yea

rs)

Ref

.M

ater

ial

date

d

Sea

-sur

face

Tem

pera

ture

(°C

)E

nvir

onm

ent

ofde

posi

tion

TO

-349

5–1

31.3

252

.89

Hec

ate

Str

ait

W.

–116

1036

080

5Tw

ign/

aL

/bra

ckis

hR

IDD

L(E

87A

22-1

21)

–128

.52

50.9

5C

ook

Ban

k–1

0410

370

140

6U

nide

ntif

ied

mar

ine

biva

lve

n/a

I/es

tuar

y

NA

-1(E

87A

13-1

72)

–128

.63

51.1

5C

ook

Ban

k–1

4010

370

120

9U

nide

ntif

ied

mar

ine

biva

lve

+1

to+

7S

M

TO

-373

5–1

31.3

252

.89

Hec

ate

Str

ait

W.

–116

1039

070

*U

nide

ntif

ied

mar

ine

biva

lve

–3to

+15

I

CA

MS

-496

30–1

31.4

052

.46

Juan

Per

ezS

ound

–107

1039

050

10@

Saxi

dom

usgi

gant

eus

n/a

IR

IDD

L-

(E87

A23

–83)

–128

.44

51.0

0C

ook

Ban

k–9

410

400

140

8W

ood

n/a

TN

A-2

(E87

A4-

140)

–128

.67

51.1

4C

ook

Ban

k–1

2210

430

130

9W

ood

n/a

I/T

RID

DL

-985

–128

.44

51.0

0C

ook

Ban

k–9

410

470

7511

Roo

tn/

aT

RID

DL

-981

–128

.44

51.0

0C

ook

Ban

k–9

410

485

708

Woo

d+

1to

+9

T/S

MN

A-3

(V94

A18

-481

)–1

31.7

152

.78

Log

anIn

let

–220

1056

070

2B

ranc

hlet

n/a

L/S

M/b

rack

ish

TO

-125

4–1

29.0

851

.94

Goo

seIs

land

Ban

k–1

3310

640

706

@M

acom

ain

cong

rua

–2to

+16

I/es

tuar

yR

IDD

L-9

84–1

28.4

451

.00

Coo

kB

ank

–94

1065

035

08

Woo

dn/

aT

TO

-125

7b–1

29.1

951

.87

Goo

seIs

land

Ban

k–1

2110

660

806

@Sa

xido

mus

giga

nteu

s+

4to

+24

IC

AM

S-1

8601

–131

.40

52.4

4B

urna

byS

trai

t–1

1110

670

602

Woo

dn/

aS

M/T

/FT

O-1

342

–129

.25

51.8

5G

oose

Isla

ndB

ank

–124

1073

070

6@

Zir

faea

pils

bryi

–1to

+25

Low

IN

A-4

(V94

A11

-81)

–131

.40

52.4

4B

urna

byS

trai

t–1

1110

760

602

@M

ytil

ussp

.n/

aF

/SM

CA

MS

-481

55–1

31.4

052

.49

Juan

Per

ezS

ound

–120

1090

050

10@

Pro

toth

aca

stam

inea

+2

to+

9I

CA

MS

-339

32–1

30.8

253

.80

Hec

ate

Str

ait

–114

1103

060

6W

ood

n/a

SM

/del

taC

AM

S-5

4600

–131

.40

52.4

9Ju

anP

erez

Sou

nd–1

3011

060

50#

@Sa

xido

mus

giga

nteu

s+

4to

+16

I/es

tuar

yC

AM

S-4

7674

–131

.40

52.4

9Ju

anP

erez

Sou

nd–1

2811

150

5010

@P

roto

thac

ast

amin

ea+

4to

+14

I/es

tuar

yC

AM

S-5

4601

–131

.40

52.4

9Ju

anP

erez

Sou

nd–1

2211

160

50#

@P

roto

thac

ate

nerr

ima

+4

to+

14I

CA

MS

-476

75–1

31.3

952

.49

Juan

Per

ezS

ound

–125

1129

050

10@

Pro

toth

aca

tene

rrim

a+

4to

+14

IC

AM

S-3

3927

–132

.60

53.4

0R

enne

llS

ound

–152

1129

060

*W

ood

n/a

A/S

MC

AM

S-4

9631

–131

.41

52.4

9Ju

anP

erez

Sou

nd–1

1911

330

5010

@P

roto

thac

ate

nerr

ima

+4

to+

19I

TO

-133

6–1

31.9

753

.24

Hec

ate

Str

ait

–109

c11

360

706

@C

lino

card

ium

nutt

alli

i+

2to

+19

I/sh

elte

red

CA

MS

-262

78–1

30.8

253

.80

Hec

ate

Str

ait.

–114

1148

060

6D

ecid

uous

woo

dn/

aS

M/d

elta

CA

MS

-339

28–1

32.6

053

.40

Ren

nell

Sou

nd–1

5211

820

60*

Woo

dn/

aA

/SM

CA

MS

-337

96–1

32.6

053

.40

Ren

nell

Sou

nd–1

5212

370

60*

@C

oope

rell

asp

.n/

aA

/SM

TO

-125

5–1

29.0

851

.94

Goo

seIs

land

Ban

k–1

3312

380

906

Wor

mtu

bes

n/a

I/es

tuar

yC

AM

S-3

3929

–132

.60

53.4

0R

enne

llS

ound

–152

1238

060

*W

ood

n/a

A/S

MG

SC

-311

2–1

31.8

853

.74

Cap

eB

all

512

400

100

3Te

rres

tria

lpe

atn/

aT

TO

-930

8–1

30.5

453

.02

Hec

ate

Str

ait

–111

1252

010

0*

@Sa

xido

mus

giga

nteu

sn/

aI/

estu

ary

TO

-930

9–1

29.0

851

.94

Goo

seIs

land

Ban

k–1

3312

540

140

*$

Bal

anus

glan

dulu

sn/

aI/

estu

ary

Bet

a-11

4464

–130

.43

54.5

4P

ort

Sim

pson

5012

580

5012

@Sa

xido

mus

giga

nteu

s+

2to

+15

I/es

tuar

yT

O-7

7–1

28.4

951

.49

Goo

seIs

land

Tro

ugh

–192

1262

080

7@

Mac

oma

nasu

tan/

aS

M/i

rreg

ular

lyfl

ushe

dB

eta-

1144

65–1

30.4

354

.54

Por

tS

imps

on50

1265

050

12@

Tres

usnu

ttal

lii

+2

to+

15I/

estu

ary

TO

-930

5–1

29.1

951

.87

Goo

seIs

land

Ban

k–1

2112

710

100

*@

Myt

ilus

tros

sulu

s+

4to

+24

I/pr

otec

ted

CA

MS

-262

82–1

30.8

853

.96

Hec

ate

Str

ait

–77

1290

060

13@

Myt

ilus

sp.

+1

to+

20I

TO

-349

2–1

31.3

053

.87

Dog

fish

Ban

k–3

113

190

100

14D

war

fw

illo

wpl

ant

n/a

T

Tab

leA

1(c

onti

nued

).

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:41 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen

© 2003 NRC Canada

1766 Can. J. Earth Sci. Vol. 40, 2003

Lab

No.

(Sam

ple

No.

)L

ongi

tude

(dec

imal

°)L

atit

ude

(dec

imal

°)L

ocat

ion

Pre

sent

elev

atio

n(m

)M

RC

14C

date

Unc

erta

inty

(yea

rs)

Ref

.M

ater

ial

date

d

Sea

-sur

face

Tem

pera

ture

(°C

)E

nvir

onm

ent

ofde

posi

tion

GS

C-3

711

–128

.49

51.4

9G

oose

Isla

ndT

roug

h–1

9213

210

150

7@

Mac

oma

nasu

tan/

aS

M/i

rreg

ular

lyfl

ushe

dT

O-1

335

–130

.84

53.2

6H

ecat

eS

trai

t–1

4413

220

80*

@M

acom

ana

suta

+1

to+

15S

M/d

elta

/hig

hse

dim

ent

infl

uxG

SC

-322

2–1

31.8

853

.74

Cap

eB

all

813

700

100

3B

ryop

hyte

sn/

aT

TO

-373

8–1

31.3

053

.87

Dog

fish

Ban

k–3

113

790

150

14Te

rres

tria

lpl

ant

n/a

TT

O-4

888

–131

.23

53.9

4H

ecat

eS

trai

tW

.–2

5d14

180

110

13&

Cas

sidu

lare

nifo

rme

n/a

SM

/col

dG

SC

-374

6–1

28.4

951

.49

Goo

seIs

land

Tro

ugh

–192

1520

049

07

Uni

dent

ifie

dm

arin

ebi

valv

e+

1to

+16

SM

/sil

ty

Not

e:M

RC

,m

arin

ere

serv

oir

corr

ecte

dra

dioc

arbo

nye

ars

befo

repr

esen

t.T

,te

rres

tria

l;SM

,sh

allo

w;

I,in

tert

idal

;F,

fluv

ial;

A,

allu

vial

;R

ef.,

refe

renc

es.

@,

Mar

ine

mol

lusc

-biv

alve

(cla

m)

shel

l;%

,M

arin

em

ollu

sc-g

astr

opod

(sna

ilsan

dM

exic

anha

ts)

shel

l;$,

Bar

nacl

e;&

,fo

ram

inif

era;

§,Fi

r(t

ree)

.1.

Low

den,

J.A

.,an

dB

lake

,W

.,Jr

.19

79.

Geo

logi

cal

Surv

eyof

Can

ada

radi

ocar

bon

date

sX

IX:

Geo

logi

cal

Surv

eyof

Can

ada,

Pape

r79

-7.

2.Jo

senh

ans,

H.W

.,Fe

dje,

D.W

.,Pi

enitz

,R

.,an

dSo

utho

n,J.

1997

.E

arly

hum

ans

and

rapi

dly

chan

ging

Hol

ocen

ese

ale

vels

inth

eQ

ueen

Cha

rlot

teIs

land

s–

Hec

ate

Stra

it,B

ritis

hC

olum

bia,

Can

ada.

Scie

nce,

277:

71–7

4.3.

Cla

gue,

J.J.

,H

arpe

r,J.

R.,

Heb

da,

R.J

.,an

dH

owes

,D

.E.

1982

.L

ate

Qua

tern

ary

sea

leve

lsan

dcr

usta

lm

ovem

ents

,co

asta

lB

ritis

hC

o-lu

mbi

a.C

anad

ian

Jour

nal

ofE

arth

Scie

nces

,19

:59

7–61

8.4.

Sout

hon,

J.R

.,N

elso

n,D

.E.,

and

Vog

el,

J.S.

1990

.A

reco

rdof

past

ocea

n–at

mos

pher

era

dioc

arbo

ndi

ffer

ence

sfr

omth

eno

rthe

ast

Paci

fic.

Pale

ocea

nogr

aphy

,5:

197–

206.

5.Jo

senh

ans,

H.W

.,Fe

dje,

D.W

.,C

onw

ay,

K.W

.,an

dB

arri

e,J.

V.

1995

.Po

stgl

acia

lse

ale

vels

onth

ew

este

rnC

anad

ian

cont

inen

tal

shel

f:ev

iden

cefo

rra

pid

chan

ge,

ex-

tens

ive

suba

eria

lex

posu

re,

and

earl

yhu

man

habi

tatio

n.M

arin

eG

eolo

gy,

125:

73–9

4.6.

Bar

rie,

J.V

.,an

dC

onw

ay,

K.W

.20

02.

Rap

idse

ale

vel

chan

gean

dco

asta

lev

olut

ion

onth

ePa

cifi

cm

argi

nof

Can

ada.

Jour

nal

ofSe

dim

enta

ryG

eolo

gy,

150:

171–

183.

7.L

uter

naue

r,J.

L,

Con

way

,K

.W.,

Cla

gue,

J.J.

,an

dB

lais

e,B

.19

89b.

Lat

eQ

uate

rnar

yge

olog

yan

dge

ochr

onol

ogy

ofth

ece

ntra

lco

ntin

enta

lsh

elf

ofw

este

rnC

anad

a.M

arin

eG

eolo

gy,

89:

57–6

8.8.

Lut

erna

uer,

J.L

.,C

lagu

eJ.

J.,

Con

way

,K

.W.,

Bar

rie,

J.V

.,B

lais

e,B

.,an

dM

athe

wes

,R

.W.

1989

a.L

ate

Plei

stoc

ene

terr

estr

ial

depo

sits

onth

eco

ntin

enta

lsh

elf

ofw

este

rnC

anad

a:ev

iden

cefo

rra

pid

sea-

leve

lch

ange

atth

een

dof

the

last

glac

iatio

n.G

eolo

gy,

17:

357–

360.

9.B

arri

e,J.

V.

1991

.C

onte

mpo

rary

and

relic

ttit

anif

erou

ssa

ndfa

cies

onth

ew

este

rnC

anad

ian

cont

inen

tal

shel

f.C

ontin

enta

lSh

elf

Res

earc

h,11

:67

–79.

10.

Fedj

e,D

.W.,

and

Jose

nhan

s,H

.W.

2000

.D

row

ned

fore

sts

and

arch

aeol

ogy

onth

eco

ntin

enta

lsh

elf

ofB

ritis

hC

olum

-bi

a,C

anad

a.G

eolo

gy,

28:

99–1

02.

11.

Bar

rie,

J.V

.,B

ornh

old,

B.D

.,C

onw

ay,

K.W

.,an

dL

uter

naue

r,J.

L.

1991

.Su

rfic

ial

geol

ogy

ofth

eno

rthw

este

rnC

anad

ian

cont

inen

tal

shel

f.C

ontin

enta

lSh

elf

Re-

sear

ch,

11:

701–

715.

12.

Arc

her,

D.J

.W.

1998

.E

arly

Hol

ocen

ela

ndsc

apes

onth

eno

rth

coas

tof

B.C

.31

stan

nual

mee

ting

Can

adia

nA

rcha

eolo

gica

lA

ssoc

iatio

n,V

icto

ria,

B.C

.,A

bstr

acts

:34

.13

.B

arri

e,J.

V.,

and

Con

way

,K

.W.

1999

.L

ate

Qua

tern

ary

glac

iatio

nan

dpo

stgl

acia

lst

ratig

raph

yof

the

nort

hern

Paci

fic

mar

gin

ofC

anad

a.Q

uate

rnar

yR

esea

rch,

51:

113–

123.

14.

Bar

rie,

J.V

.,C

onw

ay,

K.W

.,M

athe

wes

,R

.W.,

Jose

nhan

s,H

.W.,

and

John

s,M

.J.

1993

.Su

bmer

ged

Lat

eQ

uate

rnar

yte

rres

tria

lde

posi

tsan

dpa

leoe

nvir

onm

ent

ofno

rthe

rnH

ecat

eSt

rait,

Bri

tish

Col

umbi

aco

ntin

enta

lsh

elf,

Can

ada.

Qua

tern

ary

Inte

rnat

iona

l,20

:12

3–12

9.*,

prev

ious

lyun

publ

ishe

d,G

eolo

gica

lSu

rvey

ofC

anad

a.#,

prev

ious

lyun

publ

ishe

d,Pa

rks

Can

ada.

a Inco

rrec

tda

tein

refe

renc

edpu

blic

atio

n.b In

corr

ect

lab

num

ber

inre

fere

nced

publ

icat

ion.

c Dep

thof

sam

ple

adju

sted

toac

cura

tely

refl

ect

bath

ymet

ric

dept

hat

site

loca

tion.

d Dep

thof

sam

ple

adju

sted

toac

cura

tely

refl

ect

bath

ymet

ric

dept

hat

site

loca

tion.

Tab

leA

1(c

oncl

uded

).

J:\cjes\cjes4012\E03-071.vpDecember 11, 2003 10:32:41 AM

Color profile: DisabledComposite Default screen