Language & the Mind LING240 How many colors can Color ...

Transcript of Language & the Mind LING240 How many colors can Color ...

1

Language & the MindLING240

Summer Session II, 2005Color Categories & Perception

Lecture7

How many colors canyou name?

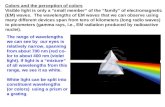

hue

brightness

saturation

wavelength

intensity

purity

3 Dimensions of ColorOscillation frequency oflight radiation

Amplitude oflight radiation

Intensity of dominantwavelength, relative toentire light signal

Brightness

Saturation

Maunsell color chips

How would you divide these up?

2

Maunsell color chips

huebrightness

Berlin & Kay (1969)

“The prevailing doctrine of American linguists and anthropologistshas, in this century, been one of extreme linguistic relativity.Briefly, the doctrine…holds that each language performs theencoding of experience into sound in a unique manner. Hence,each language is semantically arbitrary relative to every otherlanguage. According to this view, the search for semanticuniversals is fruitless in principle. This doctrine is chieflyassociated in America with the names of Edward Sapir and B. L.Whorf. Proponents of this view frequently offer as a paradigmexample the alleged total semantic arbitrariness of the lexicalcoding of color. We suspect that this allegation of totalarbitrariness in the way languages segment color space is a grossoverstatement.”

Relativistic Position

“Our partitioning of the spectrum consists of the arbitrary impositionof a category system upon a continuous physical domain…The Shona speaker froms a color category from what we callorange, red, and purple, giving them all the same utterlyunpronounceable name. But he also makes a distinction within theband we term green. Here we have a clear case of speakers ofdifferent languages slicing up perceptual world differently. And, ofcourse, it is also the case that the kinds of slices one makes arerelated to the names for the slices available in his language.”

(Krauss, 1968)

Cross-cultural Studies

(Berlin & Kay, 1969)

Berlin & Kay findings supportthe universalist hypothesis

“Although different language encode in theirvocabularies different numbers of basic colorcategories, a total universal inventory of exactly11 basic color categories exists from which the 11or fewer basic color terms of any given languageare always drawn.”

3

Implicational Hierarchy ofColor Terms

whiteblack red

greenyellow blue brown

purplepinkorangegrey

< < < < <

(Berlin & Kay, 1969)

2048 possible groups of these colors - but only 22 (<1%) are actuallyfound in languages

Cross-cultural Studies• Studies dating back to 19th century• 1972 - Eleanor Rosch - ‘Dugub’ Dani

community, Papua New Guinea– 2 color terms (‘dark’, ‘light’)– Good color perception, similarities to English

speakers• Better recognition of 8 ‘focal’ colors• Verbal paired-associate learning for focal/non-

focal colors Eleanor RoschUC Berkeley

Cross-cultural Studies

• Criticisms of Berlin & Kay conclusions

–Small samples of speakers

–Over-reliance on Western, literatesocieties

Kay & Rieger, 2003

• Data collected in situ from 110unwritten languages

• Languages spoken in small-scale, non-industrialized societies

• Average of 24 native speakers perlanguage

• 330 color chips named, one at a time• Asked to tell which is the best example

of their basic color terms

(Kay & Regier, 2003)

Kay & Rieger, 2003

• Questions

– Do color terms from different languagescluster together in color space to a degreegreater than chance?

– Do color terms from unwritten languages ofnon-industrialized societies fall near colorterms from written languages ofindustrialized societies?

4

(Kay & Regier, 2003)

“Certain privilegedpoints in color spaceappear to anchor thecolor naming systemsof the world’s systems,viewed as a statisticalaggregate.”

Maunsell color chips

MacLaury (1997), Elemental Chromatic Colors

Debi RobersonU. of Essex, UK

Jules DavidoffU. of London, UK

Berinmo tribeNew Guinea

English

Berinmo

(Davidoff, 2001)

Questioning Universality• Experiments

– I. RECOGNITION MEMORY

– II. PAIRED-ASSOCIATE LEARNING

– III. SIMILARITY

– IV. CATEGORY LEARNING

– V. RECOGNITION

5

Recognition Memory

• First just name all the color chips

• Then look at 1 chip at a time. It’s thentaken away for 30 seconds, and youmust point to the color you say in thewhole array.

Paired-Associate Learning

• Speakers learn arbitrary associationsbetween (non-)focal colors andobjects (e.g. palm nuts - nol)

• Berinmo did not find it easier to formassociations to the English focal set ofstimuli than to the non-focal set

Categorical Perception

• If categorical effects are restricted to linguisticboundaries, the 2 populations should showmarkedly different responses across the 2category boundaries (green-blue and nol-wor)

• If categorical effects are determined by theuniversal properties of the visual system, thenboth populations should show the sameresponse patterns

English

Berinmo

(Davidoff, 2001)

Maunsell color chips

Similarity Judgments• Choose the “odd man out” in a set of 3 color

chips

• Perceptual distances were the same for eachpair in the set

• Observers judged colors from the samelinguistic category (for their language) to bemore similar; they were at chance fordecisions relating to other language’s colorcategories

6

Category Learning• Taught to divide the color space at 4 places:

– blue/green (English-only boundary)– yellow/green (English-only boundary)– nol/wor (Berinmo-only boundary)– green1/green2 (no language boundary)

• Shown 6 chips, and told 3 were from categoryA and 3 were from category B

• Then asked to sort into category A and B -given feedback until they reached the criterion

Recognition Across/Within Categories

English speakers showed significantly superiorrecognition for targets from cross-categorypairs than for those from within-category pairsfor the green-blue boundary, but not for thenol-wor boundary. Berinmo speakers had theopposite pattern.

Their Conclusions• “At the very least, our results would indicate that

cultural and linguistic training can affect low-levelperception.”

• “Our data show that the possession of color termsaffects the way colors are organized into categories.Hence, we argue against an account of colorcategorization that is based on an innately determinedneurophysiology. Instead, we propose that colorcategories are formed from boundary demarcationbased predominantly on language. Thus, in asubstantial way we present evidence forlinguistic relativity.”

Black: MacLaury (1997), Elemental Chromatic ColorsBlue: Kay (2005), Berinmo color centroids

But…Kay & Kempton (1984)• English: distinction between green & blue• Tarahumara (northern Mexico): no lexical distinction

‘grue’

• Subjects were given triads of color chips & had to pickwhich one was “most different” from the other two

? ?

7

Kay & Kempton (1984)• A-H were the 8 color chips used

• The numbers represent the perceptual distancesbetween the hues

Kay & Kemton (1984)

A Closer Look• This part seems to support the Whorfianhypothesis

• English speakers seem to judge twocolors to be perceptually further apart ifthey cross a color boundary

A Closer Look

• This part also seems to support theWhorfian hypothesis

• English speakers seem to judge twocolors to be perceptually further apart ifthey cross a color boundary…but theTarahumara speakers also have someof this effect

One Thought• Maybe this is a result of people naming the colorsin order to make their decision

• So the effect of language is not on perception ofcolor but on strategy for encoding color

• So what happens when the experimenters eliminatethe ability to name the color?• Prediction: English speakers should lose their“Whorfian bias”

Eliminating the Naming Bias•The English subjects (the one who showed the “Whorfianbias”) were shown triads of color chips again• This time, they were only able to see 2 of the 3 colorchips at any given time

• “Tell me which is bigger: the difference ingreenness between the two chips on the left orthe difference in blueness between the two chipson the right”

Same chipcalled “green”and “blue”

8

Results• Englishspeakers seemto choose thepair with thelarger perceptualdifference asmost different,whether or not itcrosses thelanguagecategoryboundary

The “Whorfian effect” disappears!

More on Verbal Encoding of Colors(Roberson & Davidoff, 2000)

• Subjects were shown a color and then asked toread color words (verbal interference) or look at amulticolored dot pattern (visual interference)

• Subjects then shown 2 color chips - the originalcolor and one that was 1 or 2 color chips away

• Asked which was the original color

Within category identificationAcross category identification

Verbal interferenceonly interferes withacross-categoryidentification. Thissuggests that verbalencoding is whatcauses judgementsof greater perceptualdistance

• So what do we conclude aboutlinguistic relativity and color…?