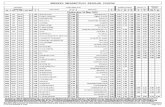

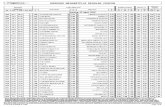

Field102040FG Action Regulation Football Mandatory Standards Training.

Labour Standards in Football -...

Transcript of Labour Standards in Football -...

1

A Case Study of a Nike Vendor in Sialkot, Pakistan

Pakistan Institute of Labour Education & Research

L a b o u r S t a n d a r d s i n

M a n u f a c t u r i n g I n d u s t r yFootball

June 2009

First published June 2009ISBN

Published byPakistan Institute of Labour Education & Research

PILER CentreST-001, Sector X, Sub-Sector VGulshan-e-Maymar, Karachi-75340, PakistanTel: (92-21) 6351145-7Fax: (92-21) 6350354Email: [email protected]

Research AdvisorKaramat Ali

Research Team Leader &Author of the ReportZeenat Hisam

Project ManagerZulfiqar Shah

Field CoordinatorTariq Awan Malik

Consultant-LawyersMunazza HashmiRana Amjad Ali

Field Team MembersAasma CheemaNadira AzizOwais Ahmad RazaMehrunnisaZahid Ali

Sialkot Field Support StaffGhaffarKashif Mahmud KhanMuddassir

Cover Design and LayoutK. B. Abro

2

The Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER), engaged with labourissues for the last 25 years, has undertaken to review the changing trends and the factorsimpacting adversely on the workers' lives and the working conditions, and document theworkers' struggles to counteract these forces. This report attempts to put together a picture

of the current status of labour in the country.

The report aims to facilitate the role of the civil society as a watchdog of human rights related towork and workplace. A constant vigil and monitoring of labour laws violations can serve as a usefultool in the struggle to ensure rights enshrined in the Constitution, national legislation and interna-tional covenants and standards.

The report covers the period up to December 2006 and is based on two categories of sources. Firstly,the secondary sources which range from print media and the internet, to the latest official reportsand documents, research studies and articles available on the subject. Secondly, and of particularsignificance, is the PILER's direct engagement and interaction with workers and labour organizationsin the informal sector, trade unions, civil society groups and representatives of state labour institu-tions.

The assessment of conditions of work and employment put together in this report is based on thework undertaken by the PILER programme and field staff members in recent years. Besides smallsurveys, rapid assessments and sector profiles, the national conventions of workers in the textile,brick kilns, transport, construction and light engineering sectors organized by PILER in 2005 havecontributed richly to the report. Information sharing by workers' representatives, trade unionists,social activists during seminars, training workshops and consultative meetings organized by PILERand the help sought by the workers through the Labour Rights Helpline services have also providedinsights in to the assessment.

The report, first of its kind, acknowledges being deficient in many aspects in view of the constraintsin documentation and systematic data collection prevalent at all levels of society. The constraintsinclude non-cooperation of state governance structures to share data related to labour, lack of dis-passionate critique of labour legislation, and the lack of a unified institutional mechanism at non-governmental level to monitor labour matters.

PILER looks forward to critical review, comments and suggestions for improvement in future report-ing.

Karamat AliExecutive DirectorApril 2007

3

Preface

T

4

1. The Study: Introduction

1.1. Objectives1.2 Methodology1.3 Data Collection Process1.4 Constraints

2. The Context: Football Manufacturing in Sialkot

2.1 Decentralization: Cutting Labour Costs2.2 Technology: Writing on the Wall2.3 Labour Standards in Foot ball Industry: Exclusion and Oversight2.4 ILO Labour Conventions: Ratification and Reality2.5 Code of Conduct and Corporate Social Responsibility: The New Paradigm2.6 State Regulatory Mechanisms2.7 Focus on Child Labour versus Core Labour Standards: The Missing Link2.8 Prioritization of Issues in the Global Supply Chain2.9 Macro Policies and Livelihood Options2.10 The Industrialist's Mindset2.11 Cost of Labour Compliance: View from Above

3. The Field: Production Process and the Work Place

3.1 Switch from Home to 'Centre': Changing Labels3.2 The 'Monitorable Stitching Centres' 3.3 Saga Sports Purposely-built Work Centres: Introduction of a New Concept3.4 Saga Management: Benevolent Employer

4. The Workers: Life and Work Conditions

4.1 Socio-Economic Indicators4.2 Employment Status and Work Conditions4.3 Wage Structure and Facilities4.4 Subcontracting through Makers4.5 Peshgi or Advance Payment System4.6 Workplace Preferences and Collective Resistance4.7 Monitoring Mechanism4.8 Workers' Age and Child Labour4.9 Knowledge of Nike Code of Conduct, ILO Conventions and National Labour Legislation

5

Contents

4.10 Unionization 4.11 Status of Workers employed at the Main Factory

5. The Women Workers

5.1 Saga's Machralla Community Center5.2 Preference for Work Centres 5.3 Solidarity, Collective Resistance and Bargaining5.4 Gender and Access to Information5.5 Gender and Wage Differential

6. Post-Saga Employment Status

6.1 Impact of Closure6.1.1 Economic Hardship for the Household6.1.2 Impact on Children's Schooling6.1.3 Impact on Women's Income6.2 Entitlements and Claims6.3 Registration with Employees Old-age Benefit Institution6.4 Registration with Punjab Employees Social Security Institution6.5 Post-Closure Claims of Entitlement through Legal Support

7. Can Sialkot Take the Lead?

71. Sialkot Football Manufacturing Industry: Key Issues7.2 The Way Forward: The Sialkot Model 7.2.1 A Rights-based and Holistic Approach7.2.2 Workers' Representation7.2.3 Industry-based Employers' Associations 7.2.4 Tripartism at the Local Level7.2.4 Strong State Labour Institutions and Mechanisms7.2.5 Research and Development7.2.6 Human Resource Development

6

Sialkot district is a hub of industrial clustersproducing sports goods, leather goods andsurgical instruments for local and foreign mar-kets. Linked to an increasingly sophisticated

global finance and marketing system, the Sialkotlabour-intensive business model and productionprocesses are still largely family-owned, cottage-based and informal, relying on a semi-literate, semi-skilled workforce operating in precarious conditionsunder weak state regulatory mechanisms.

Global business, pushed by the western media, civilsociety and the end-consumers on fulfilling its corpo-rate social responsibility, singled out an element of theprevalent informal labour relations in 1996: the use ofchild labour in the football industry. The threat to localbusiness led the Sialkot industrialists to sign theAtlanta Agreement in 1997 to rid the industry of childlabour. Facilitated by the other three signatories—theILO, the UNICEF and the state body—the subsequent

implementation of the Sialkot Project succeeded, byand large, in its focused mission: child free labour infootball manufacturing. The other crucial terms andconditions—denial of free association and collectivebargaining, low wages, lack of social protection andoccupational health and safety—prevalent in theindustry were overlooked by all stakeholders (localindustrialists, state bodies, international organizationsincluding the ILO, the civil society and the academi-cians who researched the issue).

It was after a decade of the Atlanta Agreement thatthe industry faced consequences of non-compliance oflabor standards. In November 2006, the Nike Inc.cancelled its order of hand-stitched soccer balls to itscontracting manufacturer, Saga Sports Private Limited,on charges of violation of labour standards, includingallegation of child labour. One of the several largesports goods exporters in Sialkot, Saga Sports wassupplying 15,000 to 25,000 balls per day to Nike

7

1. The Study: Introduction

Inc. Saga Sports closure caused loss of job to 7,387men and women workers. According to Nike Inc.:That decision was due to the factory's inaction on cor-recting significant labor compliance violations and afundamental breach of trust with factory management.Among the violations was widespread, unauthorizedoutsourcing of Nike production inside homes in thesurrounding area.1

By December of 2006 Nike had decided to withdrawfrom Saga Sports, although the phased withdrawalwas not completed until March 2007. With the deci-sion to withdraw, a Request for Proposals was drawnup and advertised in the Pakistan business media seek-ing new suppliers of hand-stitched soccer balls thatcould work with Nike to develop and to maintain pro-duction within a social environment that complied fullywith the company's code of conduct. On 15thFebruary 2007, Nike issued a public letter to stake-holders in which it stated, "Nike is committed to plac-ing soccer ball production back in Pakistan with a newmanufacturer operating a new business model thatstrongly supports workers' rights." With the letter Nikeissued a tender, seeking business proposals. Afterextensive appraisal of technical and social complianceaspects of the responding factories by Nike, a newsupply contract was initiated with the Silver StarGroup. The agreement included workers' training inlabour rights and the company's code of conduct.

During this period, the Nike Inc. also mediatedthrough Just Solutions Network, a European NGO, tosupport an action research project in Sialkot imple-mented by Pakistan Institute of Labour Education &Research (PILER) during April to March 2008. Thecomponent of legal support to the retrenched workers,however, has continued in 2009. Simultaneously, aprogramme of labour education in the new supplyfactory was also initiated by Nike Inc., mediatedthrough Just Solutions Network and implemented byP I L E R .

1.1 Objectives

The project aimed to explore the ex-Saga workers'life and past/current work situation, the produc-

tion processes in place, particularly the concept andthe reality of 'work centres' or 'monitorable stitchingcentres' and probed the extent of non-compliance of

labour standards in football manufacturing focusingon Saga Sports. The project also sought to sensitizea number of the identified ex-Saga workers on labourstandards, national labour legislation and code ofconduct. Legal aid was provided to those amongretrenched workers who could claim entitlements fromSaga Sports. The sacked workers were assisted torelocate in the new supply chain.

The project attempted to facilitate emergence of amulti-stakeholders (manufacturers-employers, workers,state officials, trade union bodies, civil society repre-sentatives) consensus on a framework leading to somesort of institutional mechanism for corporate socialresponsibility and labour standards compliance andmonitoring in Sialkot.

1.2 Methodology

8

The objectives of the action research—pertaining toinquiry of the problem and support to the affected

workers—and the specific condition of the partici-pants (workforce in transition) necessitated a blend oftools. Collaborative inquiry with main research partic-ipants (the sacked workers) yielded information andinsights through one-to-one interaction and question-naire filling, focus group discussions, informal meet-ings and labour education interactive workshops.Meetings and broad-based consultations with otherstakeholders—representatives of ex-Saga Union, localtrade union federation, state officials (Employees Old-age Benefit Institution, Punjab Employees SocialSecurity Institution, Provincial Labour Department,Local Government), members of Sialkot Chamber ofCommerce and Industry, ILO and IndependentMonitoring Association on Child Labour (IMAC) offi-cials—facilitated understanding of the larger perspec-tive and shed light in to the dynamics of variant roles

of the key stakeholders.

1.3 Data collection process

At the time Nike Inc. announced its intention to pullout in November 2006, the Saga Sports

employed a workforce of 7,637 of whom 5,257 werepiece-rate workers residing in more than 400 rural set-tlements dispersed in three tehsils of the district(Sialkot, Pasrur, Daska)—spread over 3,016 kilome-tres—and converging to work at the Saga-operatedtwelve (12) large official stitching centers located inthe semi-rural settlements of the district.2

By the time the support project began in April 2007(one month after the last Nike orders had been ful-filled), all of Saga Sports' 5,257 piece-rate contractworkers had already lost work. The 2,380 permanentemployees were retrenched in phases. Only about250 employees were reported to be working at theSaga Sports main factory producing leather gloves inlate December 2007 when the field work came toend.3

The detailed list of the Saga Sports' contract work-ers/permanent employees and the Saga WorkCenters were used for mapping. Initial visits to the 12villages were made and the PILER field teams talked tothe local people about the closed Saga Work Centerlocated in that particular village and enquired aboutthe ex-stitchers who came from the surrounding vil-lages.

In the second stage, two teams, comprising one maleand one female investigator each, visited 4 to 7 vil-lages surrounding each Saga Work Center to locatethe listed retrenched workers by name and address.The questionnaire was tested in the first round of infor-mation collection and revised.

Initial group discussions with ex-Saga workers wereorganized in those villages where the work centerswere located. The discussions took place in the tradi-tional village community meeting space locally calleddera or chaupaal. Selection of the villages for discus-sions was made in view of the number of the identi-fied and available workers (15-25 workers). Focusgroup discussions were held with the assistance ofproactive ex-Saga workers who showed willingness to

9

mobilize and gather ex-Saga workers. By the time theproject wound up its field work in December 2007,the team had interacted with a total of 2,484 ex-Sagaworkers, scattered in 250 villages.

Unstructured interviews and one-to-one meetings wereheld with other stakeholders-representatives ofMinistry of Labour, Sialkot Chamber of Commerceand Industry, Pakistan Workers' Federation, MatrixSourcing, Independent Monitoring Association onChild Labour and Community Development Centre.

1.4 Constraints

Access to the sacked workers in identified villagesturned out to be a difficult and time consuming

process as many workers by that time had eitheralready found stitching work, or were actively lookingfor work outside the village, or had taken up menial,odd jobs to feed the families and were not availableduring the days. It was after some time that the wordof the teams' persistent visits spread around and theworkers took time out to meet the field teams. Not allthe sacked workers could be located in view of timeand resource constraints. Apparently some of them

joined the ever growing 'foot loose'4 labour evermoving from one district/town to other in search ofdaily wage, low-skilled, manual labour or any low-paid work.

Saga Sports management refused to meet the teamwhen approached on several occasions.Understandably they neither had time, nor desire tobrief the team on the failure of a company onceranked as the most successful in Sialkot. The study,thus, does not contain any version of Saga Sportsown perspective on the issue. The Saga Sports work-ers' union also kept a cordial distance with the PILERteam though a couple of its representatives participat-ed in some of the workshops and seminars.

Sialkot's industrialists, specially the major footballmanufacturers, were suspicious and distrustful of thePILER intervention, particularly in the beginning whenthey competed for the contract by the Nike Inc. Later,however, they participated in the consultations andseminars held by PILER and granted interviews to thePILER team members.

10

Hand-made leather and wooden sports goodsproduction in Sialkot dates back to late nine-teenth century when locally crafted sports

goods were made to order for the ruling British.Cottage-based, export-oriented industry survived theexchange of population--departure of Hindu tradingcommunity, and induction of Muslim peasants andcraftsmen-in 1947. The industry, comprising small,family-owned enterprises, received state support dur-ing the 1960s and saw the emergence of mediumsized firms employing labour who came from the sur-rounding villages to the city-based units.

Today the inflatable ball is the core product ofPakistan's sports goods industry. Sialkot supplies 22per cent of total world exports5 , through a network of3,229 village-level sourcing or cottage enterprises

and informal labour.6 In 2005 the sports goods indus-try contributed US$ 318.8 million to the nationalexchequer.7

2.1 Decentralization: Cutting Labour Costs

Informalisation of labour in Sialkot began in the1970s when the state policies, apparently promis-

ing a better deal for labour, led to growing demandsfor improved terms and conditions—including theright to unionize and collective bargaining—in majorindustrial cities. In a bid to forestall it repercussions,the Sialkot entrepreneurs instead of devising strategiesto maintain efficient, productive and well-integratedlabour, took the easy way out—cutting labor costs—through decentralizing the production. The rudimenta-ry automated processes of football manufacturing(panel cutting, screen-printing, quality control) were

11

2. The Context: Football Manufacturing in Sialkot

kept at the city-based units and the labour-intensivepanel-stitching was sub-contracted out to the village-based workforce.

A development that coincided with and augmentedinformalisation of labour related to technology. Till1970s the pieces of football, made of leather,demanded strength and a high level of skill for stitch-ing and only men did it. Football manufacturingunderwent expansion in the 1980s when syntheticmaterial totally replaced the leather. Synthetic panels,much lighter than leather, could now be sewn togeth-er by women and children as well.

Another decisive factor that led to the expansion ofemployment of semi-skilled, under-paid, piece raterural workers in late 1980s onward was the transfor-mation of global economy and the international capi-tal movements towards labour-intensive, unregulatedlabour markets. As a production site, Sialkot, with itspromise of much lower production cost of sportsgoods—9 to 10 percent as measured by the finalprice paid by the consumer8—attracted a number ofmulti-national brand companies (i.e. Nike, Adidas,Puma, Reebok). Within two decades, production offootballs in Sialkot had increased eight hundred fold:from 5.2 million footballs in 1980-81 the number shotup to 40-43 million in 2000-01. The number of sub-contracted workers increased from 5000-7000 in1980-81 to 54,000 workers in 2000-01. A down-ward trend in production is noticeable since then,indicating a wave of transformation linked to techno-logical changes and globalization. In 2003-04, thenumber of balls produced annually fell to 33-35 mil-lion and the number of workers taking this occupationdeclined to 41,000 - 44,000.9

2.2 Technology: Writing on the Walls

The evolution of football making—from pig's blad-der (1800) to vulcanized rubber (1836) to inflat-

able rubber bladders (1862) to mass production(1888)—was accelerated with the induction of syn-thetic material (1960s). In the 1980s synthetic leatherhad totally replaced hard leather. After severalimprovements based on material development, tradi-tional ball construction reached its limits. In 2000 anew ball production technique, thermal bonding, wasdeveloped to ensure consistent quality and perform-

ance from one ball to the next. The technique resultedin the first automated, thermal bonded, seamlessTeamgeist Berlin match ball used in the FIFA WorldCup (July 2006). The design and technology was per-fected by Adidas, Germany, and balls were pro-duced by the brand's suppliers in China andThailand.

Since then there is no turning back. Machine-madeballs were used in the 2008 Beijing Olympics Gamesand the 2010 and 2014 FIFA World Cup would usethe seamless balls. Romanticizing the dexterouslycrafted hand-made football and the centuries old her-itage of human stitching skills notwithstanding, the eraof manual craftsmanship seems to be ending. Nike,however, is of the view that there will always be aniche for hand-stitched balls hence it decided to con-tinue production from Sialkot.

Viewed in the historical context, mechanization andautomation always win out in the end. Resistance tochange is a natural human reaction yet the momentumof technological change carries in its force the com-plex dynamics of social, economic, historical and cul-tural factors that eventually over ride all resistanceand push communities to change and adapt. Thespeed of adaptation to technological change varies,though.

Addressing technology has never been a priority forthe Sialkot sports goods industry and is indicative ofan inward-looking, narrow approach rather than anopen, receptive-to-change strategy. Lack of timely andadequate response to changes in technology has costdearly in the recent past: the technology shift fromwood-based material to aluminum-based alloys andthen to graphite and other synthetic materials in theproduction of hockey sticks and badminton, squashand tennis rackets wiped out this component almostentirely from Sialkot in early 1990s. The process ofchange has accelerated with the advancement in nan-otechnology: since 2005 carbon nano-tubes arebeing used in the production of hockey sticks andsports rackets.

The stakeholders' consultation facilitated by theSialkot Chamber of Commerce and Industry inJanuary 2007 revealed reluctance on the part of the

12

manufacturers to read the writings on the wall: theyseemed to be avoiding a full-throated debate on theissue, though the second generation industrialistsacknowledged the impending impact of technologicaltransformation on the Sialkot industry.

Similarly, in the subsequent consultation called by theMinistry of Labour, facilitated by the ILO-Pakistan, inFebruary 2007—that led to the document titledSialkot Initiative 2007—technology did not figure asa key issue.

2.3 Labour Standards in Football Industry:

Exclusion and Oversight

Right to work and earn a decent living under con-ditions of freedom and dignity is granted under

the Constitution of Pakistan in its Article 3 and Article37c10, and though national labour legislation hasturned increasingly restrictive and exclusionary overthe years, particularly with respect to the workers'right to unionize and bargain collectively, variousstatutes (i.e. Factories Act, Minimum WagesOrdinance) contain provisions to safeguard some ofthe basic standards. As the crucial monitoring mecha-nism, labour inspection by state bodies, has almostceased to exist since the Punjab Industrial Policy 2003(putting a stop to inspection in the province) andLabour Inspection Policy 2006 (diluting inspectionand advocating self-reporting) came into effect, viola-tions have become a norm, more so in small andmedium-sized establishments. Football industry inSialkot is no exception.

The existing laws contain provisions for contractlabour. These provisions, however, are violated byemployers due to a lacunae: section 2 (f) (iv) of theWest Pakistan Industrial and Commercial Employment(Standing Orders) Ordinance 1968 declares the'establishment of a contractor' as an independentestablishment, thus making it easier for both principalemployer as well as contractor to escape law. Thecontract system keeps the owner indemnified againstnon-observance of labour laws.

Subcontracted workers in Sialkot football industry,removed from the regulated environs of formal worksites and largely excluded from protective legislation,

are a part of the bulk of informal workforce (72.6 percent ) in the country. Low wages, lack of social pro-tection and lack of representational security charac-terize their work conditions. Unorganized and dis-persed in surrounding villages, with low literacy leveland little or no access to information on labour rightsand legislative mechanisms, football stitchers are vul-nerable to both local and global forces.

The regular workers employed at the main factoriesthat lined the Daska Road leading to the city, farehardly any better. Placed at the lower end of produc-tion hierarchy, these workers are largely deprived ofentitlements due to non-issuance of employment con-tract by the manufacturer and bypassing of applicablerules and regulations.

2.4 The Atlanta Agreement 1997 and Sialkot

Initiative 2007

The Atlanta Agreement, and the subsequent projectto eliminate child labour from football industry,

was termed successful. The success, though, was lim-ited. Three reasons can be cited for its limitations.Firstly, it did not embrace the full range of labour stan-dards but focused on child labour as if child labourexists in a vacuum. Secondly, though a tripartitearrangement it excluded workers' representation. Theissue of child labour was not just linked to childrenwho stitched footballs, but involved adult workers whomade a conscious choice to put their children to wagelabour. Thirdly, the Agreement came about inresponse to external stimuli. The threat to brand imageperceived by international companies played a cru-cial role. The business community in Sialkot waspushed by the global stakeholders to remove the stig-ma from the produce. These included the InternationalFederation of Football Association (FIFA), WorldFederation of Sports Goods Industry (WFSGI), theInternational Confederation of Free Trade Unions(ICFTU), the International Labour Organization (ILO)and the leading football manufacturers such as Nike,Adidas, Reebok, Mitre (UK).

The Sialkot Initiative 2007, that followed a tripartiteworkshop jointly organized, in December 2007, bythe Government of Pakistan and the ILO after Nike'scancellation of the contract, suffers from similar and afew additional drawbacks (i.e. over-emphasis on

13

monitoring and the role of IMAC), including its lack ofa holistic approach. The Initiative 2007, till today,remains a document.

2.5 ILO Labour Conventions: Ratification and

Reality

Pakistan is a signatory to the UN UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights 1948 that recog-

nizes the right to work, to freely choose employmentand to have just and favourable working conditions,and to the 1998 ILO Declaration on FundamentalPrincipals and Rights at Work that pledges to 'pro-mote opportunities for women and men to obtaindecent and productive work, in conditions of free-dom, equity, security and human dignity'.

Pakistan has ratified all the eight core ILO conventionsthat codify the four most basic human rights related tothe world of work—the right to organize and engagein collective bargaining, the right to equality at work,the abolition of child labour and the abolition offorced labour.

Signing and ratification of international covenantsand standards put only a moral binding on the gov-ernment: practically it has little or no impact on theground. The ILO supervisory bodies (i.e. Committee ofExperts on the Application of Conventions andRecommendations) continue to urge the government toamend legislation to ensure core labour rights to allworkers.11 In Sialkot, the emphasis has been on theabolition of child labour—and that too mainly in thefootball industry—while other critical labour rights vio-lations have been sidelined by all stakeholders.

2.6 Globalization and Corporate Social

Responsibility: The New Paradigm

Global transformation is leading to greater inter-linking and interdependence of economies,

reshaping labour relations in the process. Expansionof international trade and international capital move-ments is impacting societies in unprecedented ways.Economic growth, generation of wealth and newdevelopment opportunities are benefiting the coun-tries that have a competitive advantage in certainareas. In Asian countries, competitive advantage islow production cost due to low labour cost and this in

turn is leading to greater informalization of labour.Contractual, home-based work relations are becom-ing a norm, replacing long-term employment rela-tions. The workforce stands unorganized, fragmentedand dispersed in various smaller locations andunconnected spaces. The impact of labour unions theworld over is much reduced.

The labour movement in Pakistan is weak, fragmentedand beset with a myriad of problems emanating fromsocial milieu and political culture and economy atlarge. The workforce is largely uneducated. Around90 per cent of the workforce is unorganised henceunaffected by labour movement. In the miniscule for-mal sector, rate of unionisation is very low. The exist-ing unions are divided along ethnic and sectarianlines, have undemocratic culture and lack committedand enlightened leadership. An important drawbackof the labour movement is its lack of acknowledge-ment of women's role in productive economy andinduction of women workers in its rank and file. All

14

said and done, despite its many weaknesses, labourmovement has struggled throughout against repressivemeasures and legislation.

Competitive advantage is driving manufacturers andemployers to further cut labour cost and local power-ful stakeholders—manufacturers, industrialists, statebodies—deliberately sideline national laws and inter-national standards. Pro-industrialist policies andunconditional heavy subsidies to industries in Pakistanhave not translated in to better bargain and betterconditions for workers. Weak labour regulation andpoor implementation of labour standards in countrieswhere MNCs are shifting production, like in Pakistan,have created a vacuum and compelled MNCs toaddress labour compliance issues in the subcontract-ed production places in response to increasing pres-sure from consumers in their home countries.

The business environment in the 21st century hasevolved under the forces of globalisation, supply

chain complexity, existence of consumer and humanrights pressure groups, and the presence of fiercecompetition across the globe. In this environment, it isimperative for a successful and profitable MNC tohave a positive corporate image. The corporatebrand name must be free from any and all negativeconnotations.

To achieve this goal, one of the tools employed by theMNCs is the development and stipulation of codes ofconduct for constituent members of their supply chainwho may be operating in any of the numerous coun-tries of the world. The MNCs are developing codes ofconduct in compliance with international labour stan-dards codified in the ILO conventions. Many ratifyingcountries, though commit themselves to bring legisla-tion within the parameters drawn by the ILO stan-dards, fail to do so.

Development of codes is a sensitive and difficult taskespecially in countries where the state and local gov-ernments are lax in implementing existing laws. It isalso possible that the levels set by the state laws maydeemed to be not high enough for the requirements ofthe MNCs. In some cases the state laws may be defi-cient and may not be addressing an issue, which is ofconcern to the MNC. Hence the need for developmentof their own private codes of conduct for the con-stituent members of the supply chain. In case wherethe codes and the existing national legislation differ,the provision that gives high level of protection toworkers apply in the company's code of conduct.

The company's codes of conduct is a voluntary com-mitment by the MNC, though usually the company'smotives—either strategic, defensive or ultruistic—arestrong enough to compel the company to honour andpush for implementation of its code of conduct. Themode of implementation is mostly dependant on moralobligation on the part of the constituent member, orthe local vendor, in the supply chain. The ultimatelever remains in the hand of the MNC: that it can takeits business relationship elsewhere if the local vendoris not implementing the code and the MNC wants thecode to be implemented.

Consumer and media pressure for fair trade is leadingto an increasing number of codes produced after con-

15

sultation and negotiation with stakeholders includingtrade unions. The Nike Code of Conduct, for instance,was produced after input from the InternationalTextile, Garment and Leather Workers' Federation(ITGLWF).

However, due to the overwhelming informal nature ofeconomy in developing countries and lack of legalcoverage to informal workers even when the codesare implemented, the benefits tend to remain limitedto permanent and regular workers and '…contractworkers experience little change' in their working con-ditions.12 Nike's provision for formal, custom-builtwork centres in Sialkot was supposed to address com-pliance issues related to informal work place. Thoughthe vendor (Saga Sports) did provide formal, custom-built centre, it failed to abide by the code and keptmore than 90 per cent of its work in the informal cat-egory which ultimately brought cancellation of thecontract by Nike.

A recent MIT study indicates that codes of conductproduce results only in those countries that have bet-ter implementation of national labour laws and arefound to be linked to '…the ability of the labourinspectorate to enforce labour laws and standards inthe country'.13

A PILER study of the Karachi garment factories sup-plying to the US and the European brands (i.e. Warl-Mart, C&A, Disney, Karstadt Quelle, la BlanchePorte) revealed non-compliance of labour standardsdespite existence of the codes of conduct of respectivebrands and the SA8000 accreditation of each facto-ry.14 Another PILER study on small and medium-sizedenterprises indicated that most enterprises do not com-ply with labour laws and are averse to collective bar-gaining.15

2.7 State Regulatory Mechanisms

The Ministry of Labour, Manpower and OverseasPakistanis is responsible for labour and employ-

ment policy formulation, legislation, administrationand implementation. Labor and employment are thesubjects listed under the concurrent legislative list andthe provincial governments are also mandated to for-mulate policies on their own.

Punjab Industrial Policy 2003 eliminated inspection ofindustries/workplaces by labour inspectors in viola-tion of ILO Convention 81 ratified by Pakistan. Theinspection was replaced by a self-declaration systemfor units having 50 or more workers. This also lapsedin June 2005 after completion of the 2-year period asthe government did not notify its extension. TheLabour Department, the Punjab Employees SocialSecurity Institution, and the Employees Old-ageBenefit Institution, however, remain restricted fromconducting inspections of the industrial units.

In 2006 the government came up with LabourInspection Policy and physical labour inspection wasdone away with in other provinces as well. The pro-cedures to replace physical inspection as spelled outin the policy document were vague and did not mate-rialize. The Labour Inspection Policy 2006 wasapproved by the federal ministry and the documentshared with stakeholders in Feb 2008. The Policynow envisages setting up a National LabourInspectorate and Provincial Labour Inspectorates toserve as focal points for all labour inspection functionsin the provinces, including that of Social SecurityInstitutions and the EOBI. At the moment the policyremains on paper.

2.8 Focus on Child Labour vs Core Labour

Standards: The Missing Link

Child labour has shown an increasing trend inPakistan. The total number of children aged 10-

14 years, engaged in a wide range of paid activities,rose from 2.12 million in 2003-04 to 3.06 million in2005-06.16 Currently labour force participation ratein this age group is 13.65 percent.17 The increase inchild labour is linked to informalisation and theexpanding low-paid, unprotected, home-based workthat does not generate decent income and compeladults to supplement the household income throughchild labour. Another key factor is lack of compulso-ry, adequate schooling facilities. Over 6.4 millionchildren are reported to be out of school in Pakistanand available to the segmented labour market.18

Though not included in the list of 39 hazardous occu-pations for children19, child labour in the footballindustry of Sialkot has been the focus of heightenedglobal and national concern, academic debate and

16

contesting viewpoints of a wide array of stakehold-ers—consumers and media groups in the US andEurope, international human and labour rights organ-isations, global business partners, national civil socie-ty, industrialists, state bodies and academicians.While the western media pressure after the 1994World Cup and the 1996 ban imposed by the FIFAon the use of child labour in soccer ball production leftthe state and the local industry with no choice but torid itself of child labour, some academicians critiquedthe consequences of the undertaking done 'on the bid-ding of the West'.20

What did not come under scrutiny were the wide-spread violations of labour rights in the football indus-try and the crucial link between these violations andchild labour: low adult wages, informal labour rela-tions and lack of social protection that compel vulner-able families to supplement household income throughchild labour. Child labour occurs in an environment inwhich there is a reasonably high demand for labourand a low degree of labour empowerment.21 Lowlevel of labour empowerment in Sialkot and its mixwith a 'fierce entrepreneurial spirit'22 and weak stateregulatory mechanisms were overlooked both by aca-demicians and the project planners. Nike Inc. accept-ed after a decade (in 2007) that core labour stan-dards were not addressed in contract manufacturingof soccer balls:

'Based on the outcomes of the FIFA meeting held inNovember 2006, and our own findings, it is ourbelief that any revised agreement needs to addresshow one ensures adherence to core labour stan-dards—not just the issue of child labour'.23

Worth mentioning is the prevalence of child labour inanother equally important, export-oriented sector-Sialkot's 100-year old surgical instruments industry.Local stakeholders' low-intensity delayed action andthe absence of global stakeholders' concerns throwup questions on exclusive focus on child labour in foot-ball industry. Unlike football stitching, cottage-basedsurgical instruments manufacturing involves extremelyhazardous processes. Yet it was in 2004 that the ILO-IPEC started its project to combat child labour in thissector.24

Child labour in the surgical instruments industry (pres-ent since decades) went unnoticed by the global busi-ness because the end buyers are faceless institu-tions—private hospitals, state health services—deal-ing with dull and drab and unmentionable routine ofsickness, ageing and death, unlike consumers, indi-vidual players and professional teams, associatedwith the glamorous world of sports that celebrates life,youth and fitness.

2.9 Prioritization of Issues in the Global Supply

Chain

When a US media report first exposed childlabour in Sialkot football manufacturing in

1995, it galvanized the entire western media, humanrights organizations and the US legislators. The resultwas the Foul Ball Campaign launched by theInternational Labour Rights Forum. Sialkot city becamethe site of investigation against violations of childrights by global stakeholders. The campaign led toadoption of the Code of Labour Practice for all manu-facturers by the International Federation of FootballAssociations (FIFA) in 1996, and the signing of theAtlanta Agreement by the Sialkot Chamber ofCommerce and Industry, the ILO, the UNICEF andSave the Children Fund UK in February 1997.Subsequently, a monitoring system was put in place,children were phased out from the football industryand the stakeholders saw to it that the footballs pro-duced in Sialkot were labeled 'child labour free'.

In contrast to the uproar and subsequent action of themid 1990s to address the issue of child labour, theNike cancellation of the contract on non-complianceof labour standards, leading to massive lay-off inSialkot in 2007, did not stir the global media and nei-ther lead to any campaign by global stakeholders.

2.10 Macro policies and livelihood options in

Sialkot District

Sialkot district, a hub of labour-intensive industrialclusters, comprises largely a population (73.8 per

cent) officially defined as rural.25 The district is one ofthe most fertile lands fed by Chenab River, DeghNullah and Aik Nullah (flowing from the Jammu Hills)and the Marala Ravi Link Canal. The main crops arewheat, rice and maize. Change in land tenure pat-

17

tern, since the last four decades, has led to a declinein tenancy and an increase in the number of smallowner-cultivated farms. Rising number of small owner-cultivated farms, though, has not led to increase inproductivity and crop production growth hasremained stagnant.

In Sialkot district too fragmentation of farms is increas-ing and the cultivated farm area declining. In the dis-trict, the percentage of farms under 12.5 acresincreased from 91 percent in 1990 to 95 per cent in2000.26 Another characteristic of the district is thegrowth of peri-urban areas around Sialkot city. Thisgrowth is manifest in a higher rate of fragmentation ofagricultural land and land use change in settlementsadjoining the city.

Almost 50 per cent of the households in the district aredescribed officially as agricultural households,depending on agriculture and livestock.27 The ambi-guity of official definition of 'rural population' is man-ifest in significant difference within official data: inpopulation census (1998) 73.8 per cent of Sialkotpopulation is termed rural; in the 2000 agriculturalcensus 50 per cent is labelled 'agricultural house-holds'.

This study, however, indicates a different picture: forthe majority of the respondents, football stitching wasthe main source of income. High prices of agricultur-al inputs, low acreage and weather uncertaintieshave greatly reduced income from land. In addition,small farmers, due to low holding capacity are com-pelled to market their produce soon after harvest atlow price and purchase food requirements at highprices. Government policies have favoured largefarmers through subsidies in water and agriculture.Large farmers have benefited from credit schemes andcheaper access to mechanization.

Unprofitable farming is pushing many households tosell their small landholdings as indicated by severalcase studies of workers during this research.Landlessness and low return on agriculture have com-pelled households to depend mainly on wage work inthe manufacturing sector—sports goods, leathergoods and surgical instrument—in Sialkot.

2.11 The Industrialist's Mindset

The study shows an informal, non-professional man-agement style operating in Sialkot where industri-

al firms are owned and managed by immediate fam-ily members and blood relatives with a minimum ofprofessional staff at the managerial level.

'A typical management system of a company consistsof two tiers: the first comprises of the owner/entre-preneur (top management) and the second opera-tional staff. There is no link between the two tiers, i.e.middle management is either weak or non-existent'.28

The firms subcontract out work at piece-rate to distant,under-privileged, low-skilled, less-educated, ruralworkforce. The relationship between the employerand the worker in this case is much worse than theclassic unequal industrialist-worker relationship. Theowner-industrialist often tends to adopt the role of apatron-sustainer of the 'poor unemployed people'.This is sustained through nepotism and informal pro-cedures of hiring and firing, lack of implementation oflabour standards and services rule, and selective-spo-radic display of 'benevolence' instead of adhering toinstitutionalized mechanisms to ensure access to enti-tlements and established facilities.

The local industrialists looked down upon workers, orkammis, with scorn and disapproval and use deroga-tory words and stereotypes--jahil, nashaie, kaahil(ignorant, addicts, lazy).29 The industrialist believesthat the workers are poor because of their owndoings: 'they don't work hard'. The industrialist thinkshe has to make the best out of a semi-skilled, semi-lit-erate workforce who stands no chance for animprovement. 'Because that's the way they are'. Theindustrialist seems to hold as deterministic a worldview as held by workers about their own situation.

Interaction with manufacturers indicated a number ofmisconceptions or untested assumptions about work-ers. Generally held perceptions among the manufac-turers included unwillingness on the part of the work-ers to come and work in the city. 'They cling to theirvillages, like frogs in the well', 'They want work attheir door steps', etc.

In focus group discussions the workers talked of the

18

constraints. The daily commute to the city incurs trans-port and food cost and unless the wages are aboveRs. 5,000 per month, the workers find it uneconomi-cal to work in the city. Many villages are about 30 to50 km away from the city. With link roads in terribleshape, commuting time increases twofold. 'Besides,how can we get a better paid job in the city? Wehave no education and no other skill.'30

Many local manufacturers are in possession of theSA8000 certification, which according to a source'…is being sold in the city on thela (hawking cart) byaccrediting companies for Rs. 200,000 each'.

Several of the manufacturers believe they take care ofthe workers' rights and it is the workers who are outto exploit them and sabotage their businesses.

'We care a lot about our workers. We know if wegive them due rights they will cooperate with us oth-erwise they give us a real hard time. For example,during peak production days they can put us in trou-ble through non-cooperation. You don't know theexcuses workers come up with for poor performance,absenteeism and for not achieving the targets.'

According to one of the leading manufacturers, work-

19

ers in the registered main factories get due rights. Thecontractual labour, working from home, or in privatesheds, are not entitled to any rights and as such,states the manufacturer, there is no question of labourlaws violation. The manufacturers who do accept thatworkers are not getting a fair deal, think enhancedlabour cost would impact their businesses adversely.

'Your business will collapse if you increase labourcost beyond a certain point. You don't know howsharp the MNCs are. It's a cut-throat world out there.They want the best of the product at the cheapest cost.And there are so many countries with even cheaperlabour than Pakistan. How do you expect Sialkotindustrialists to survive in this scenario?'

According to the local manufacturers, the industryhas already squeezed its margin of profits to

avoid child labour and is losing its competitive edgeto China where labour is much cheaper. The industri-alist '… cannot pay the same benefits to piece-rate,contract workers as to the salaried, permanent work-er'.31 The older generation of industrialists, in controlof their businesses currently, seemed to be quite out ofsync with changing global scenario. The second gen-eration-owners' sons and male kins-qualified in busi-ness management, has yet to take charge. Most ofthese young men are working under the tutelage oftheir fathers.

2.12 Cost of Labour Compliance: View from Above

The argument that labour compliance is a costlyaffair and hampers growth of small and medium-

sized enterprises does not just reflect a (narrow) visionupheld by Sialkot manufacturers, it is an off-shoot ofmacro policy analysis and advice of internationalfinancial donors (IMF, World Bank, AsianDevelopment Bank). '…The Banks hold that the impo-sition of typical labour standards can hamper povertyreduction in Pakistan'.32 However, neither officialdata nor field assessments support the argument thatlabour compliance is a serious constraint in thegrowth of MSEs.33

A similar simplistic analysis—funded by the EuropeanUnion—of the constraints faced by Sialkot entrepre-neurs, implying a justification for lack of labour com-pliance, is attributed to the small size of the enterpris-es:

'Their small size puts a lot of constraints on the com-panies themselves and adds insufficiencies to the sec-tor's overall dynamics as well. These firms only focuson "me too" products, mostly compete on prices, tryto grab other companies' customers (usually by offer-ing lower prices), don't invest anything on R&D, pro-vide very little, if any, customer after-sales support andat times create a bad image for the country'.34

20

In terms of development Sialkot ranks as the thirdleast deprived district on the national scale trailingbehind only Karachi and Lahore.35 Known for its

thriving small and medium-size entrepreneurial cultureand its contribution to the national exchequer, Sialkothas also received famed for its Airport and the DryPort built and run by the private sector and itsexporters' voluntary contribution (0.3 per cent of theirexport invoice amount) to the Sialkot DevelopmentFund.36 The Sialkot exporters have had the distinc-tion of having made an effort to rid the football indus-try of child labour through signing the AtlantaAgreement a decade ago. Sialkot industry is domi-nated by the presence of foreign brands, voluntarily

committed to ethical business practices in contractingfactories through respective codes of conduct. Allthese facts conjure up images of a labour force inSialkot as the one receiving a fair share of benefits ofglobal supply chain production. There is a disconnect,however, between these assumptions and the lives ofthe workers as lived by them.

3.1 Switch from Home to 'Centre': Changing

Labels

Hand-stitched football manufacturing is a labourintensive process employing a large number of

informal piece rate workforce. Football productionhas low and high seasons (World Cup/other match-

21

3. The Field: Production Process and the Work Place

es/promotional campaigns by foreign brands)depending on orders from the foreign brand compa-nies. The contracting football manufacturer, with aproduction base/factory in the city to undertake initialand end processes (screen printing, panel cutting,hole-making, quality checking and packing) subcon-tracts the manual stitching of the panels to individualsubcontractors called 'makers' in local parlance. The'maker', himself a village-based worker—albeit rela-tively better-positioned and mobile—identifies stitch-ers in need of work in his own village and the sur-rounding areas.

Before engaging the stitchers, the 'maker' raisesmoney either through accessing credit or selling hisown meager assets to clear the first hurdle to his ownearning: 'advance' cash demanded by individualworkers. This 'advance' is given on the basis of theorder (number of footballs to be supplied) and thecapacity of the worker to stitch a certain number ofballs besides the stated need of the stitcher (i.e. med-ical treatment, daughter's wedding). The advancevaries from Rs. 2,500 to Rs. 15,000. With cash inhand to be paid to stitchers, the maker takes thework—football panels to be sewn together—to thestitchers' doorsteps and later deliver back the stitchedfootballs to the production base. The maker charges acommission (Rs. 3 per ball) from the manufacturer forthis service.

Prior to the signing of the Atlanta Agreement in 1997,football stitching was carried out by men, women andchildren in their respective homes in the surroundingvillages. The Sialkot Project that followed the AtlantaAgreement undertook to phase out child labourthrough a monitoring mechanism involving voluntaryparticipation of the manufacturers.

'Under the project, the participating manufacturerswere required to transfer their work from houses to (a)place, which could be monitored by the ILO-IPEC. Forsetting up such a center, the basic criteria agreed withthe SCCI was that wherever minimum of 5 stitchersmale or female or both could sit together and therespective manufacturer placed a small sign boardoutside that should be treated as a center.'37

The condition of 5 stitchers was later modified to 3

stitchers per center in case of women.38 This transferof work from houses to 'monitorable place' meantleaving one's own abode and working in a similarhouse in the same village or a nearby village. Thewomen continued to work in their own houses as eachhousehold comprising an extended family systemoften has more than three female members.

3.2 The 'Monitorable Stitching Centres'

The 'Monitorable Stitching Centres'—declared assuch by the ILO-IPEC and later by IMAC—are thus

mostly modest abodes of the villagers, dingy shops orprivate sheds located in rural areas. Outside theshops or sheds, one can catch glimpse of small rustysignboards indicating simply: Stitching Centre. Attimes the signboard also displays the name of manu-facturer in smaller font size. Common village houses-turned-centres generally do not have any signboard.The large houses or haveli, often owned by the absen-tee landlords, or other influential persons, areadorned by the names of the owners who rent thesepremises to the manufacturers. The large houses, withseveral rooms and covered verandahs, accommodate50 to 150 stitchers. Inside these 'centers' the IMACcertificate in English and the manufacturer notices inUrdu, are found glued to the walls.

The 'Stitching Centers' are mandated to have basicfacilities i.e. electricity fixtures, safe drinking water,toilets. As only a wooden, short-legged stool, with orwithout back support, is required for each stitcher tosit on, plus a wooden tool, called khancha, to bepressed against the two knees to aid stitching, noteven a room in the house is required to be exclusive-ly allocated to this activity. The stools are stacked afterwork in a corner of the room, or shoved under bed.We found stitchers working in the courtyard under theneem tree shade indicating inadequacy of physicalenvirons or congestion in the rooms.

The ILO-IPEC monitoring of these home or informalwork places labeled as 'stitching centers' was handedover to the Independent Monitoring Association forChild Labour (IMAC) in 2002. The only issue for mon-itoring was child labour.39 Later in 2003 the monitor-ing of basic infrastructure (adequate space, sittingarrangement, lighting, ventilation, hygiene, safedrinking water, toilet) was brought in, but this condi-

22

tion was waived for '3-women centers'.40

In 2007, the IMAC 12-member field team was moni-toring more than 2,500 football stitching centers for87 manufacturers. The ILO-IPEC monitoring entailedrandom physical visits of the center to ascertain childlabour if any, and filling up of a form with basic factsabout the center (i.e. number of workers, amount ofwork done, wages paid).

"The 2-member ILO-IPEC team was accompanied by arepresentative of the manufacturer. We used to ques-tion his inclusion in the team but apparently therewere pressures from the manufacturers. There was nodirect institutional complaint mechanism. The workers'complaints were not conveyed to the management.The monitoring teams gave the gathered (basic) infor-mation to the coordinator who presented it in theSCCI scheduled meetings attended by AtlantaAgreement signatories. If any violation on childlabour issue was found, the management was issuednotice immediately."41

The monitoring process thus excluded core labourrights other than child labour, and the exclusion wasnot by default but by choice. The ILO field team mem-bers did not ask any question relating to core labourrights and neither gave any information on the ILOcore conventions or workers' constitutional rights.

"If all the information is given, you raise the (workers')expectations which you cannot fulfill. Workers shouldbe handled carefully, they should not be provoked (todemanding their rights)".42

It is probable that the instructions on withholding infor-mation on core labour rights were not given to thefield members explicitly. Yet the team membersimbibed the ethos of the ILO work objectives in Sialkotas it filtered down from the top. The objective was'focus on child labour' and field team members madethe tunnel vision part of their work ethos.

The fact that ILO-IMAC monitoring was critiqued in theinner circle all way long by major stakeholders didnot bring about a change:

'….the brands would have preferred IMAC to be

closed—they thought it was useless and un-reformable. In the end, they agreed to support IMAC'scontinued existence. The reasons were: it wouldembarrass the ILO to state publicly their view onIMAC, and because the SCCI are familiar with IMACand cannot handle change.'43

This refutes the assumption that flaws in project designsurface later. The fact is: often the flaws are apparentat the planning stage but due to vested interests thestake-holders maintain a tacit silence for a consider-ably long period.

3.3 Saga Sports Custom-built Work Centres:

Introduction of a New Concept

Saga Sports Pvt. Ltd. was the first local vendor inSialkot that constructed, maintained and operated

12 large, formal workplaces in rural areas exclusive-ly for football stitching, primarily to meet the Nike'srequirement for a child labour-free production.44 Thecentres were managed by the main factory, located atDaska Road, Sialkot city, where all productionprocesses (panel cutting, screen-printing, repair, pack-aging, quality control) except stitching, were under-taken.

One of the 12 centres, the Machralla Centre, wasexclusively for women, while two other centers hadseparate halls and toilet facilities for women. Theremaining centres were all-male centres. The SagaSports' work centres' capacity ranged from 350 to650 workers. The centers collectively drew 4,537workers from approximately 350 surrounding villagesspread over 3,016 km area. In addition, Saga Sportsunofficially outsourced work to 50 'mini-centres' nei-ther owned nor operated by Saga Sports.45 Thesemini-centres were closed down in June 2006 whenSaga Sports received the first complaint from Nike.46

The Saga Sports work centers, custom-built on largerpremises, comprised spacious halls, storage areasand basic facilities (ventilation, lighting, toilets, drink-ing water, canteen, clinic, fair price shop, baby carecentre, open space and plantation). The centers withofficial paraphernalia and protocol—registration ofworkers, timings, supervision, pick-and-drop andlunch facilities—provided a formal work place to aninformal labour. Formalization of the workplace,

23

however, did not lead to formalisation of work rela-tions. The workers remained piece-rate contract work-ers. Unlike houses-turned-centres, the custom-built for-mal centers eliminated child labour within these prem-ises and its incidences got reduced to occasionalcheating (reporting incorrect age) through forgedbirth certificate.

The Saga Sports work centers introduced the conceptof work outside home for both men and women home-based workers. There was initial resistance from thecommunities towards this restructuring of work placeas it caused loss of flexibility (of timing) and freedom(from supervision) of working at home. The resistanceof men towards their own employment in the centerssubsided soon as the Saga centers had many attrac-tive features. But male resistance against womenworking at the centers continued for a long time.

3.4 Saga Management: 'Benevolent' Employer

Saga's owner, late Mr. Sufi Khursheed—who hadsigned the Atlanta Agreement 1997 on behalf of

the Sialkot Chamber of Commerce and Industry—hada patron-father image among the workers. All of theex-Saga workers contacted and talked to during thestudy, remembered him as a man of kind dispositionand generosity. The workers, due to their ignoranceof the existing state social security facilities consid-ered the amount of Rs. 50,000 or less that Mr. Sufigave on death/disability of worker as a personalbenevolent gesture rather than a worker's entitlementstipulated by the state under the Workers' WelfareFund Act.

One of his qualities as recollected by the workers washis accessibility and intermingling with workers, aquality prized in modern corporate culture as well. Ofthe surveyed workers, 91 per cent reported the behav-iour and the attitude of the 'employer' at the work-place as good towards them. Apparently for them theterm 'employer' referred to the owner as many work-ers recounted taking his or her personal or officialproblem to him and he would solve it. Thus it seems,the entire system depended on role of the 'Patron'.

As the system lacked professional management,appropriate channels and lines of communication forconflict resolution and smooth industrial relations, the

edifice collapsed with the death of Mr. SufiKhursheed, the 'Patron'. Many stories told by theworkers indicate that the relations between supervi-sors and the workers at the centre deteriorated rapid-ly thereafter. Several workers narrated incidences ofharassment and abusive tactics by the managementpersonnel at the Saga work centres.

The benevolent role of the owner was very much inline with the dominant social stratification and hierar-chy based on zaat, beraderi, occupation and accu-mulated wealth and the family-based entrepreneurialemployer-craftsmen relations that have evolved histor-ically in Sialkot. The entire supply chain is character-ized with the same familial-kinship model. At the topis the ultimate 'Patron' or owner of the factory/estab-lishment. Power then filters down to a couple of man-agers who are either sons or close relatives of the

24

owner, who subcontract orders to 'makers', the next inline of 'patrons'. The 'maker' obliges his own kith andkin and neighbours though here the stitcher, whom themaker awards work, exercises some power to negoti-ate 'advance'. This 'empowerment' of the stitcher hascome about solely due to the 'seasonal' and contrac-tual nature of the work itself: the contracting brandwants a specific number of balls at specific date andunless the balls are sewn by stitchers on time, the ulti-mate loser is the local manufacturer. The loser next inline is the 'maker' who earns commission per ballstitched. The stitcher has very little at stake to beginwith: his or her loss is minimum since s/he is gettingless than the minimum wage and nothing else. As theother limited livelihood options available to the work-er are similarly low-paid, switching to menial work,casual labour, or surgical instruments making is nothard as the case studies in the following section

demonstrate. The stitcher is part of a foot-loose, float-ing labour and has learned to eke out a living any-way.

3.5 Occupational Health and Safety

The main process in the production of inflatableballs—stitching of panels by hand—-is done while

squatting on a low stool, with a wooden khanchapressed between the knees. The khancha is used tosecure leather panels and give freedom of movementto arms. The stool, used at home or small stitching cen-tres, is made of wood and often has no back support.In Saga stitching centres stools were provided withback support. However, the act of stitching is such thatmost of the time the worker has to bend his head andcrouch a bit forward for better grip and firmness of thestitch. The back support, if it is there, can be used onlysparsely while taking a rest or changing the posture.Even when the stool is padded, or is made if ropestring or synthetic material for flexibility, sitting onsuch a stool for long hours is a physically tiring actand may give back ache, pain in the legs and hardsensation to the bums. Stitching done for longer dura-tion can also tire the eyes.

Another process, making equidistant holes in thepanel for the threaded needle to go through, can bedone through a simple machine or a cast dye.However, at many places the workers have to do itmanually through pressing the marked dots with thethick needle. Utmost care is needed to make holesmanually as slight deviation from the mark may causeinjury to the fingers.

The lamination and cleaning of synthetic leather, theinitial production processes, involve use of chemicals,particularly bonding, or gluing, solution. This solutioncan lead to addiction if inhaled frequently. In the cot-tage units, no safety masks are provided to the work-ers in this section. Incidences of addiction to bondingsolution were mentioned by workers during fieldinvestigation.

One reason of predominance of young workers (15-30 years) can be linked to physical exertion and stam-ina required for foot ball stitching that cannot beundertaken for sustained period by older people. Football stitching seems to have potential to accelerate or

25

trigger joint-related illnesses (i.e. arthritis).

3.6 Trade Unions in Sialkot

Historically, Sialkot manufacturing industry has beencottage-based, comprising informal work force scat-tered in rural settlements, hence there is no legacy oflabour movement in the district comparable to union-ization that existed in the public sector industrialestablishments in big cities in the 1960s and 1970s.With the expansion of export-oriented manufacturingof sports goods and surgical instruments in the 1980sand subsequent increase in the workforce, a handfulof trade unions did emerge in Sialkot.

According to national industrial relations law only oneunion in an establishment can have the status of col-lective bargaining agent if it wins the election throughsecret ballot. 'In effect, therefore, registered tradeunions which fail to get elected and certified as thecollective bargaining agent have no role in the pre-scribed procedure of industrial relations'. The lawmeant to curb multiplicity of unions, in effect hasaided employers to install 'pro-management' unionthrough corrupting the trade unionists and outlawinggenuine representation of workers.

The implanting of 'pocket union'--as called in localparlance-- is a national malaise and obstruct forma-tion and operation of genuine trade unions.Contributing factors are a weak and fragmentedlabour movement and overbearing individual impulsefor self interest versus values of cooperation, trust andcollective interest.

Three trade union federations—Pakistan Workers'Federation, All Mehnatkash Labour Federation andNational Labour Federation—are said to be operativein Sialkot, each claiming to have 10 to 12 localunions as members. A total of 62 trade unions in var-ied sectors—sports goods, sports wear, leather, surgi-cal instruments, banking, etc—are registered with theDistrict Officer Labour, Sialkot. Of these, only 25unions hold the status of collective bargaining agent.48

Two trade unionists, Niaz Ahmad Naji, GeneralSecretary All Mehnatkash Federation, and SardarRehmatullah, Genereal Secretary, Saga Workers'Union, Saga (Pvt Ltd.) were listed members (repre-senting workers) of the following committees of stateinstitutions:49

Dispute Resolution Committee, EOBI Sailkot, District Committee of Management Workers'Children Education Cess; District Scrutiny Committee for Marriage Grants, Death Grants and Talent Scholarships; District Allotment Committee for Allotment of Flats & Houses and Labour Colonies; School Management Committee of the Workers Welfare School, Punjab Workers' Welfare Board.

As indicated by the case study, no evidence of aneffective role of trade unions, particularly of the SagaWorkers Union, could be established in Sialkot.

26

For a better understanding of the life situation ofworkers in Sialkot district, it befits to start yourjourney from Cantonment area, subsequent to

your disembarkment either at the Sialkot Airport or atDaewo Bus Station and lodging in a comfortable zonein the city. After crossing the barricaded archway onthe 3-laned, two-corridor Kashmir Road, you coursethrough a neat, wide asphalt, lined on one side forconsiderable length by the green Garrison Park andleafy bungalows on the other. Ahead, the roadsideshave a row of big shops of local designers, a mall ortwo and the eateries. The Kashmir Road at the far endtakes on a T-shape and here is the most striking fea-ture of Sialkot. Lined by single-storey, swanky shops ofinternational brands and food chains, the peacefulambience of the street with wide footpaths on both

side evokes for a fleeting instant the images of theAmerican suburbia.

Besides the barracks, the officers' mess-turned-into-commercial Chowinda Meadows restaurant, the hos-pital and the army's other establishments, theCantonment area comprises residential neighbour-hoods inhabited by the army officers and the localelite. The area is serviced by the cantonment boardand is equipped with requisite social and physicalinfrastructure—underground sewerage, solid wastemanagement, schools, parks, service shops, internetcafes. In the morning and afternoon one comes acrossarmy trucks plying as school buses ferrying children toand fro!

27

4. The Workers: Life and Work Conditions

Once you leave the Cantonment, the contours of thereal city start to emerge: traffic congestion, narrowroads cluttered with small shops and vendors. Manyof the old adjoining residential neighbourhoods havenarrow brick-paved lanes with open drains on bothsides. The newly emerging settlements have smallagricultural plots in between brick houses. As youmove outside the city towards rural settlements, youfind the link roads either under construction or in poorcondition. None of the towns and settlements in thedistrict has underground sewerage system. Most ofthe link roads leading to towns and rural settlementsare lined with ribbons of development—vending andservices shops, hardware stores, warehouses andsheds—flanked by lush green wheat fields and yellowblossoms of mustard, or rice paddies, that give a falsesense of prosperity of the common dwellers of the dis-trict.

4.1 Socio-economic Indicators

The settlements, large or small, have brick-pavedlanes and open drains. The houses are of a mixed

stock. The majority (79.4 per cent) of the ex-Sagaworkers lived in pucca (of reinforced concrete)dwellings and 48 per cent had two-room structures.Average family size was 6 to 7 members. A signifi-cant number, 30 per cent, did not have toilet facilityat home while the number of workers who reportedlack of access to safe drinking water supply was high(75.5 per cent). The overwhelming majority, 96.4percent, reported to be living in own house. The own-ership of the living space serves as bulwark againsteconomic hardships providing at least security of shel-ter.

The majority (90 per cent) had no source of incomeother than football stitching indicating almost totallack of alternative livelihoods (i.e. agribusiness, dairy

production, agricultural processing) in the largelyrural/semi-urban Sialkot district. Some reported mea-ger livestock, a couple of buffalos or goats. Just about4 per cent workers were earning a little additionalincome through cultivation of their small piece of land.

'I have a 2-acre piece of land where I cultivate wheat,rice and some vegetables. But from land you get onlytwo crops a year. I was getting just Rs. 10,000 fromselling one crop. Two crops mean less than Rs. 2,000per month. How can a family of seven survive on thatincome? I have been stitching football since the last18 years, soon after I finished Matric. I worked inSaga for 6 years. I was getting Rs. 3,180 per monthwhen I left Saga.'

Mian Mohammad Riaz, Lalaywali, Kalowal

The study indicates that football stitching is the onlysource of income for an overwhelming majority andeven the households owning small pieces of land,football stitching is the main source of income. Itrefutes the notion held by policy makers and acade-micians that football stitching is a source of addition-al income for the households taken up largely bywomen and children to save money for special occa-sions. i.e. marriage of daughters.50

Majority (72.7 per cent) of the ex-Saga workers wereyoung, 15-30 year-old, and male (74.5 per cent). Theliteracy rate, 79 per cent, was much higher than theaverage rate of 56 per cent literacy in the province ofPunjab.51 This indicates accessible primary educationfacilities in the district, a fact corroborated by the dis-trict's ranking as the third least deprived. But the levelof literacy was low: 39 per cent had just 5 years ofschooling; 22 per cent had studied up to 8 yearswhile just 11 persons had passed 10th grade. Thedata correspond to the high drop-out rate in the coun-try. The male workers cited lack of secondary schoolfacilities, poor quality of education, irrelevant curricu-la in government schools and lack of prospects ofemployment in better paid occupations as the reasonswhile women simply said their parents could notafford secondary education.52 None reported exis-tence of technical education facilities with the excep-tion of a few computer skills centres in large settle-ments.

28

'Our village, of about 5000 population, has no mid-dle level school for boys. The closest secondary schoolis five km away in Chaprar. There is no public trans-port so you have to walk 10 km everyday. Except afew, none of us could avail secondary schooling.Besides what quality of education do you get at a gov-ernment school in a small place like this? So I got intostitching football after I finished primary school. Ilearned football stitching when I was 8 years old. ButI want my son to have a different life. I plan to admithim in a private school. I want him to have good edu-cation'.

Javed, Najwal

4.2 Employment Status and Work Conditions at

Saga Sports

At the Saga Sports, an overwhelming majority—84.4 per cent—worked on piece-rate and just

15.6 per cent were regular employees. Ninety-twoper cent reported they were never given any appoint-ment/contract letter: none of them were aware of theimportance of this key document that establishes their

legal identity as worker.

More than half of the workers had worked in Saga upto five years, while 41 per cent worked 6 to 10 years.This indicates the Saga Sport had a relatively stablework force, negating general perceptions amonglocal vendors about stitchers' whimsicality and highturnover. If the workers are relatively satisfied, or thinkthey have no better options, they prefer to stay withthe employer. Saga Sports, aside its last years of mis-management, was reputed as 'the best option avail-able' company among the workers and their commu-nities.

4.3 Wage Structure and Facilities

At the time Saga Sports retrenched its workers in2007, the majority (84 per cent) was being paid

less than the minimum wage of Rs 4,600 per monthfixed in August 2006 by the government under theMinimum Wage Ordinance. Twenty-four per centreported a measly monthly income of up to Rs. 2,500only. Twenty-two percent were getting between Rs.2,500 to Rs. 3,500 and 38 per cent were paid up toRs. 4,500.

The study reveals that Saga Sports was paying evenless to its workers in earlier years. Sixty-eight (68) percent of the workers reported a salary of up to Rs.2,500 per month and 22 per cent were getting up toRs. 3,500 at the time of joining the company severalyears ago when its owner Sufi Khursheed was alive.Though late Sufi Khursheed was revered by the work-ers and remembered as a kind-hearted employer, thefact remains that labour standards were grossly vio-lated in his times as well. None of the workers wereaware of the Minimum Wage Law and of the period-ic raise in minimum wage by the state.

29

As the majority of workers were on piece-rate andwithout any contract letter, they were not registeredwith the state-run social security institutions (EOBI,SSI). Free transport, lunch and tea, basic medical helpthrough once-a-week access to a doctor plus free med-icines, and fair price shops at each work centre, how-ever, provided some relief to the workers. These min-imum facilities played a role in conferring a 'positive'image to Saga Sports among its workforce. Thoughnominal, these non-cash benefits translated in to asubstantial chunk of monthly expenditure of the house-holds.

Several of the permanent workers, who possessedrelevant registration cards, reported access to med-ical facilities through social security hospital. None ofthe contract workers were provided medical supportto prolonged illnesses (i.e. hepatitis, typhoid), injuries(not related to work place) and deaths. Many workersnarrated incidences of illnesses that required a largesum (Rs. 10,000 to Rs. 75,000) for treatment raisedpersonally either through loans from relatives or saleof meager family assets.

'My brother died of heart attack while at work atSaga. The management promised to give his family asum of Rs. 200,000 but never gave the money.'

Ghulam Mustafa, Nowshera

Physical infrastructure at the Saga stitching work cen-tres were reported by the workers to be adequate interms of space, lighting and ventilation and toilet facil-ities, though according to several workers unhygienicconditions prevailed particularly in the toilet, kitchenand canteen areas. The stools were padded and theworkers were provided panels with pre-done holes.

4.4 Subcontracting through 'Makers'

The case studies, focus group discussions and fieldvisits revealed that the traditional system of sub-

contracting and providing advanced payment toworkers was widespread at Saga Sports despite theprovision of the formal work centers that Saga builtand operated to avoid downstream subcontractingand the system of advance payment or 'peshgi'. SagaSports would pick out stitchers and offer them the sub-contracting work as 'makers', (local term used for sub-

contractors in Sialkot). A 'maker' enters into an unwrit-ten contract with the manufacturing company and itspivotal condition is the number of workers he under-takes to mobilize to complete an order (received bythe manufacturer from an international brand compa-ny) on time. The maker gets commission per piecefrom the manufacturer/vendor and is responsible fordelivery of the material (football panels) to the work-ers at his/her door step or at the stipulated work cen-tre. He then collects the finished footballs and deliversthe order back to the manufacturer.