KORNGOLD - download.e-bookshelf.de

Transcript of KORNGOLD - download.e-bookshelf.de

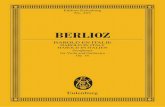

Edition EulenburgNo. 8048

KORNGOLDSYMPHONY IN F©

Op. 40

Eulenburg

ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD

Ernst Eulenburg LtdLondon · Mainz · Madrid · New York · Paris · Tokyo · Toronto · Zürich

SYMPHONY IN F�Op. 40

Preface/Vorwort . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . I

I. Moderato ma energico . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

II. Scherzo (Allegro molto) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78

III. Adagio (Lento) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146

IV. Finale (Allegro) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 196

© 1977 Schott Musik International, MainzPreface © 2000 Ernst Eulenburg & Co GmbH, Mainz

for the Europe excluding the British IslesErnst Eulenburg Ltd, London

for all other countries

All rights reserved.No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted in any form or by any means,electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of the publisher:

Ernst Eulenburg Ltd48 Great Marlborough Street

London W1V 2BN

CONTENTS/INHALT

When Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897—1957)wrote his Symphony in F sharp around the middle of this century, times were hard for this genre. Thetrend-setting protagonists of the New Music of thetime avoided it because of the aesthetic and ideo -logical ballast which it had inherited from the nineteenth century. If they did occasionally revert tothis genre, they preferred to adopt an experimentalapproach, or at least to give the works titles with adiminutive connotation: Chamber Symphony (Schön -berg, Eisler), Sinfonietta (Hindemith), 6 LittleSymphonies (Milhaud), Simple Symphony (Britten)or Short Symphony (Copland). (Of course, almost all these composers also wrote ‘big’ symphonies, butthey owe their reputation as avant-garde composersmore to the ‘small’ ones.) The influence of the NewMusic and its theoreticians has now waned some-what, and the dwindling respect for their historicaland philosophical authority has made it possible tolook at the history of twentieth-century music in adifferent way. Hence we are confronted with the factthat the classic-romantic symphonic tradition hadnot by any means come to an end with Bruckner andMahler and that in this century just as many sym-phonies have been written within this tradition aspreviously. And if they were not in every case thework of composers of the first rank, then that too isto be blamed on the dictatorial imposition of theview of history that held sway for so long.Composers such as Dmitry Shostakovich, SergeyProkofiev, William Walton, Ralph VaughanWilliams, Arthur Honegger, Gian FrancesoMalipiero and, last but not least, Erich WolfgangKorngold were not minor masters, and a reappraisalof these composers and their position in the historyof twentieth-century music is under way or at leastimminent.As regards Korngold, there were tragic circum-stances which cast a particular shadow over his life-history, musically as well as politically speaking. Itwas his fate, in both spheres, that he had the badluck, as he grew up, to be drawn into the cultural andaesthetic ambit of Vienna. Firstly, it was there, at theheart of the New Music, that he acquired, as early asthe 1930s, a slightly over-ripe traditional flavour.Secondly, it was from there that he had to go intoexile when the National Socialists marched in, al -though he was still celebrated in operatic circles(opera did not attract much attention from the NewMusic and remained a genre for traditionally ori -ented composers.) The former effect was tragic inas-much as Korngold had not only always thought ofhimself as a ‘modern’ composer, but had also alwaysbeen celebrated as such when he was a child pro d -

PREFACE/VORWORT

Als Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957) um dieMitte dieses Jahrhunderts seine Symphonie in Fisschrieb, hatte diese Gattung einen schweren Stand.Die damals tonangebenden Protagonisten der NeuenMusik gingen ihr wegen ihres ästhetisch-ideolo -gischen Ballastes aus dem 19. Jahrhundert aus demWeg, und wenn sie doch einmal darauf zurück -griffen, dann vorzugsweise unter experimentellenGesichts punkten oder zumindest unter Benutzungvon diminuierenden Namen: Kammersinfonie (Schön-berg, Eisler), Sinfonietta (Hindemith), 6 Kleine Sin -fonien (Milhaud), Simple Symphony (Britten) oderShort Symphony (Copland). (Zwar haben fast allediese Komponisten auch „große“ Sinfonien ge -schrieben, den Ruf der Avanciertheit jedoch verdan-ken sie eher den „kleinen“). Der Einfluß der NeuenMusik und ihrer Theoretiker ist inzwischen etwasverblaßt, und der schwindende Respekt vor derengeschichtsphilosophischem Diktat hat einen anderenBlick auf die Musikgeschichte des 20. Jahrhundertseröffnet. Dieser Blick konfrontiert uns mit derTatsache, daß die klassisch-romantische Traditionder Sinfonie keineswegs mit Bruckner und Mahleran ihrem Ende angekommen war und daß in diesemJahrhundert nicht weniger Sinfonien in eben dieserTradition geschrieben wurden als in dem zuvor. Undwenn ihre Komponisten nicht immer in die ersteReihe gehörten, so liegt auch das am Diktat deslange Zeit gültigen Geschichtsbildes. Komponistenwie Dmitrij Schostakowitsch, Sergej Prokofiew,William Walton, Ralph Vaughan Williams, ArthurHonegger, Gian Francesco Malipiero und nichtzuletzt auch Erich Wolfgang Korngold waren keineKleinmeister, und eine Neubewertung dieser Kom -ponisten in der Musikgeschichte des 20. Jahr hun -derts ist im Gange oder steht zumindest bevor.

Was nun Korngold betrifft, so ist dessen Biogra phie –und zwar die musikalische wie die politische – vonbesonderer Tragik überschattet. Daß er das Pechhatte, in den Wirkungskreis Wien hineingewachsenzu sein, wurde ihm nämlich in beiderlei Hinsichtzum Schicksal: Erstens bekam er dort, im Zentrumder Neuen Musik, schon in den dreißiger Jahreneinen leichten Hautgout des Überkommenen, undzweitens mußte er von dort – obwohl inOpernkreisen immer noch gefeiert (die Oper wurdevon der Neuen Musik weniger bedient und bliebeine Gattung der traditioneller orientierten Kom -ponisten) – emigrieren, als die Nationalsozialisteneinmarschierten. Ersteres war insofern tragisch, alssich Korngold nicht nur immer als ein „Moderner“gefühlt hatte, sondern in seiner Wunderkindzeit stetsauch als solcher gefeiert wurde. Um der Wahrheit

igy. However, to be perfectly honest it must beadded that throughout his period in ViennaKorngold, who at the age of 14 was already in fullpossession of his musical and technical powers, wasnot greatly affected by the problems of compositionwhich beset many composers of the time. His mu -sical personality was directed more towards prac-tical music-making than towards theoretical analysisin the manner of, for example, Schönberg,Stravinsky or Bartók. Furthermore, his musical butreactionary father Julius (that much may be said ofhim without belittling his contribution to music criticism in Vienna) influenced him in ways thatwere not always helpful. Hence it is not surprisingthat Erich Wolfgang Korngold wrote what wereperhaps his most important works when the reasonsfor his exile no longer applied and his father had alsodied (at the same time, in 1945).As is generally known, Korngold spent the periodafter 1934 in Hollywood composing film music. Hewas outstandingly successful (two Oscars forAnthony Adverse and The Adventures of RobinHood), and thereby became an inspiration for awhole generation of composers of film music. Buthe never made any secret of the fact that he did notfreely choose this activity at all but was forced intoit by the pressures of his life in exile. Korngoldwould have much preferred to continue writing operas and music for the concert hall, but in his newhomeland there was nothing like the same demandfor these that he had been used to in the old. Hencein the period up to the end of the war, apart from themusic for about twenty films which ensured survivalfor him and for other exiles who were close to him,Korngold composed hardly any music (there are afew exceptions) to which he gave an opus number.Like the other exiles with whom Korngold kept inclose contact (Arnold Schönberg, Thomas Mann) helived for the day when the war in Europe would beover and they would return and continue where theyhad left off in 1934. This was why Korngold an -nounced in 1946 that he had written his last musicfor a film, music which already contained parts of acello concerto conceived as a concert piece over andabove its use in the film. He then composed, in re -latively rapid succession, the String Quartet No. 3,the Violin Concerto in D major, The Silent Serenade(a stage comedy with music), the SymphonicSerenade for string orchestra in B flat major and theSymphony in F sharp for large orchestra. The ViolinConcerto (premiered by Jascha Heifetz in St. Louisin 1947) immediately began a relatively successfullife on the concert circuit, which has continued tothe present day. Korngold was encouraged by thissuccess to hope that everything would now oncemore be as it had been before the war.

His first journey home to native Vienna was sched -uled for May 1949 and the euphoria which this gen -erated had a direct influence on the composition of

die Ehre zu geben, muß man allerdings auch fest-stellen, daß Korngold, der mit 14 Jahren bereits imVollbesitz seiner musikalisch-handwerklichen Fähig -keiten war, während seiner ganzen Wiener Zeitwenig berührt war von den Problemen desKomponierens, von denen damals viele Kompo -nisten umgetrieben wurden. Seinem musikalischenWesen nach war er eine eher musikantische Naturals eine theoretisch-durchdringende wie z.B. Schön -berg, Strawinsky oder Bartók. Hinzu kam, daß seinmusikalisch-reaktionärer Vater Julius (man kann daswohl so sagen, ohne seine Verdienste als WienerMusikkritiker zu schmälern), nicht nur förderndenEinfluß auf ihn hatte. Und so wundert es nicht, daßErich Wolfgang seine vielleicht wichtigsten Werkeschrieb, nachdem sowohl der Anlaß für dieEmigration hinfällig wurde, als auch der Vater starb –was zeitlich zusammenfiel (er starb 1945). Wie allgemein bekannt ist, verbrachte Korngold dieZeit nach 1934 in Hollywood mit dem Komponierenvon Filmmusik. Aber obwohl er damit größte Erfolgefeierte (2 Oscars für Anthony Adverse und TheAdventures of Robin Hood) und zum Vorbild einerganzen Generation von Filmmusik kom ponistenwurde, hat er nie einen Hehl daraus gemacht, daß erdiese Tätigkeit keineswegs frei willig, sondern nurunter dem Druck der Emigration ausgeübt hat. Viellieber hätte Korngold weiterhin Opern und Musikfür den Konzertsaal geschrieben, aber dafür gab esin der neuen Heimat längst nicht den Bedarf, den eraus der alten gewohnt war. So ist in der Zeit bisKriegsende außer ca. 20 Film musiken, die ihm undanderen, nahestehenden Emigranten das Überlebengesichert haben, von wenigen Ausnahmen abge -sehen, kaum Musik entstanden, der Korngold eineOpusnummer gegeben hätte. Wie auch die anderenEmigranten, zu denen Korngold engen Kontaktpflegte (Arnold Schön berg, Thomas Mann), lebteman auf den Tag hin, an dem der Krieg in Europabeendet sein und man wieder dorthin zuückkehrenwürde, um da anknüpfen zu können, wo man 1934aufgehört hatte. So kam es, daß Korngold 1946 seineletzte Filmmusik ankündigte, die bereits Teile einesCellokonzertes enthielt, das über seine Verwendungim Film hinaus schon als Konzertstück gedacht war.In relativ schneller Folge entstanden nun das 3. Streich quartett, das Violin konzert in D-Dur, Diestumme Serenade (eine Komödie mit Musik), dieSymphonische Serenade für Streichorchester in B-Dur und die Symphonie in Fis für großesOrchester. Das Violinkonzert (1947 von JaschaHeifetz in St. Louis uraufgeführt) trat auf Anhiebeinen relativ erfolgreichen Weg durch die Konzert sälean, der bis in unsere Tage reicht, und Korngold ver-band mit diesem Erfolg die Hoffnung, daß nun alles wieder so werden würde, wie es vor dem Kriegwar. Die erste Heimreise nach Wien stand im Mai 1949an, und die Euphorie, die sie auslöste, mündeteunmittelbar in die Komposition der Symphonie in

IV

the Symphony in F sharp. His first major attempt towrite symphonic music, the Sinfonietta Op. 5 of1912, had been a great success for the composer,who was 15 years old at the time. Now he wanted toreturn home as a serious composer with the wholehistorical weight of the genre behind him. In con-trast to the almost careless manner in whichKorngold had composed in his youth, the Symphonyin F sharp, like almost all the works composed afterthe war, is permeated by a powerful structuralimpulse. It can be seen that in each of these worksthere is a particular technical problem, generally onerelating to harmony, which it was the composer’sintention to express and to resolve. Whereas in theViolin Concerto it was the attempt to derive every -thing with strict formal clarity and concentrationfrom the tonic-dominant relationship, in the CelloConcerto Korngold seems to have wanted to savourthe charm of melody alternating irridescently be -tw een major and minor. The Symphony in F sharpbears witness to nothing less than the challenge ofrethinking once again the harmonic relationships inthe exposition of a main sonata movement.

Unlike the Violin Concerto, which still employscomparatively pure functional harmony, the Sym -phony has a harmonic language which, though tonal,can no longer be adequately analysed in functionalterms. On a superficial level this can even be seen inthe keys which the two works are described as beingin: the Symphony is described as being in „F sharp“,the Violin Concerto, in contrast, in D major. To thatextent Korngold was harking back to his earlyworks, which were undoubtedly progressive as farharmony was concerned (the Sinfonietta is in B andthe Concerto for Piano, left hand, and orchestra of1923 is in C sharp).The key of the symphony is, it is true, indicated inthe traditional manner: the first movement is pre -ceded by six sharp signs, but only rarely is it poss-ible to identify a pure chord of F sharp major, exceptat the end of the movement. Even in the two charac-teristic opening chords of the first subject of themovement, the second chord is admittedly in F sharpbut is made more astringent by the addition of anaugmented fourth. Because, furthermore, there is nofifth it takes on an ambiguity which is also a con -stitutive feature of the movement in other respects: itcould equally well be a chord of the seventh on Bsharp, likewise without the fifth and with an aug-mented fourth. The ambiguity is resolved at figure 9when the second subject enters, all six sharps arecancelled and the following passage is in C, whichcould also be read as an enharmonic equivalent of Bsharp, up to the entry of the main subject in the homekey at the reprise. The upshot of this is that no lessthan half the movement stands in a tritone relation-ship to the other half – a relationship which is al- ready inscribed in that opening chord.

Fis. Sein erster großer sinfonischer Wurf, die Sinfo -nietta, op 5 aus dem Jahre 1912, hatte dem damals15jährigen schon große Erfolge beschert, und aber-mals sollte es das ganze historische Gewicht derGattung sein, mit dem Korngold sich als ernst zunehmender Komponist zurückmelden wollte. Aberim Gegensatz zu der fast sorglosen Art, mit derKorngold in seiner Jugend komponiert hat, ist dieSymphonie in Fis, wie fast alle Werke, die nach demKrieg entstanden sind, von einem starken konstruk-tiven Impetus durchdrungen. Man stellt fest, daß essich jeweils um ein bestimmtes satztechnisches,meist harmonisches Problem handelt, das zum Aus -druck und zu einer Lösung gebracht werden sollte.War es im Violinkonzert der Versuch, alles in stren-ger formaler Klarheit und Reduktion aus dem Ver -hältnis der Tonika-Dominant-Beziehung heraus zugestalten, schien Korngold im Violon cellokonzertden Reiz einer zwischen Dur und Moll changieren-den Melodik auskosten zu wollen. Und dieSymphonie in Fis gar zeugt von nicht weniger, alsder Anstrengung, die harmonischen Verhältnisse imSonatenhauptsatz noch einmal neu zu über denken.

Anders als das Violinkonzert, das sich einer nochrelativ reinen Funktionsharmonik bedient, weist dieSinfonie eine Harmonik auf, die zwar tonal, aberfunktional nur noch unzulänglich zu deuten ist.Äußerlich ist das schon an den Tonartbezeichnungender Werke ablesbar: die Sinfonie ist als in „Fis“ ste-hend bezeichnet, das Violinkonzert hingegen in D-Dur. Insofern knüpfte Korngold damit an seine inharmonischer Hinsicht durchaus fortschrittlichenFrühwerke an (die Sinfonietta steht in H und dasKonzert für Klavier linke Hand und Orchester von1923 in Cis).

Zwar ist die Sinfonie tonartlich noch herkömmlichnotiert, d.h., dem ersten Satz stehen sechs Kreuzevor; jedoch gelingt es nur selten, außer am Satzendeeinen reinen Fis-Dur-Akkord ausfindig zu machen.Schon in den beiden für das erste Thema des Satzescharakteristischen Einleitungsakkorden steht derzweite zwar in Fis, ist aber mit der übermäßigenQuarte verschärft. Dadurch, daß ihm zudem dieQuinte fehlt, bekommt er eine Doppeldeutigkeit, diefür den Satz auch noch in anderer Hinsicht kon -s titutiv ist: Es könnte ebenso ein Septakkord in Hissein, auch ohne Quinte und mit übermäßiger Quarte.Der Doppelsinn wird nun bei Ziffer 9 ein gelöst,wenn mit dem Einsatz des zweiten Themas allesechs Kreuze aufgelöst werden und das Folgende biszu dem in der Grundtonart erklingenden Reprisen -einsatz des Hauptthemas in C steht, was auch alsenharmonisch verwechseltes His zu lesen wäre. Dasheißt letztlich, daß nicht weniger als die Hälfte desSatzes im Tritonusverhältnis zur anderen angelegt ist– was diesem Anfangsakkord schon eingeschriebenist.

V

The actual main subject is every bit as ambivalent asthe relationship of this chord to the home key. Itunfolds in the clarinet from bar 4 (with upbeat) viathese same chords. It evokes associations with atwelve-tone row rather than with a tonal melody andcould be notated in C as easily as in F sharp. It isalso interesting to see in what key Korngold locatesthe second subject: having already marked out themost radically opposed tonal centres of C and Fsharp within the first subject, he puts the second sub-ject exactly in the middle between them: in E flat (aharmonic logic suggesting associations withBartók). It is not until we come to a third subject,beginning at figure 14, that we have a simple dom -inant – not, however, the dominant of F sharp butinstead that of C. And in this key of G the exposi tioncomes to an end; there is no concluding or trans -itional passage, and the development begins at fi g -ure 18 in the same key. It is characterised not somuch by sallies into remote keys — in a movementlocated between F sharp and C there are no remotekeys left — as by various attempts at developing thefirst and third subject together in the brass.

The procedure leading to the reprise of the third sub-ject is also interesting: it enters at first in E flat, thekey of the second subject, breaks off, repeats theentry in its own key of G and then after four barsbreaks off again. Only the third attempt, with adownward shift of a semitone, brings a sense of lib -eration with its entry and continuation in the homekey. It might be felt that in this procedure the prin -ciple of catharsis in the reprise in sonata form hasbecome the real theme of the work, and that the tech-nical aspects of a quest for the home key by way ofa subsidiary theme have been pondered on at length.

These examples are intended to show how, in an agewhich confronted him with the end of tonality,Korngold tried in his own way to give it a continuinglegitimacy by finding new meanings in it. Whetheror not he succeeded may be left an open question,however that may be it can be said without ex -a g gera tion that such intense reflections on musicalproblems such as are woven into the compositionalfabric of this symphony, would have been alien tothe young Korngold.In almost all his works written after the warKorngold made use of themes from film musicwhich he had composed in Hollywood. In theSymphony in F sharp the Adagio in particular, alarge-scale slow movement reminiscent of Brucknerand Mahler, was suggested by a theme from ThePrivate Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, while in thefourth movement a theme from Kings Row can beheard. Although the matter is sometimes presenteddifferently, this fact does not imply any reference tothe films in question. Furthermore, it is in most casesmerely a question of the basic shape of a musicalsubject, which is then treated in a completely new

Ebenso ambivalent, wie dieser Akkord sich zurGrundtonart verhält, ist auch das eigentliche Haupt -thema. Es breitet sich auftaktig ab Takt 4 über dennämlichen Akkorden in der Klarinette aus. EherAssoziationen an eine Zwölftonreihe weckend als aneine tonal gebundene Melodie, könnte es ebenso gutin C wie in Fis stehen. Interessant ist weiterhin, wieKorngold nun das zweite Thema tonartlich plaziert:Da mit Fis und C die tonal gegensätzlichsten Poleschon innerhalb des ersten Themas abgesteckt sind,setzt er das zweite Thema genau in die Mitte dazwi-schen – es steht in Es. (Eine harmonische Logik, dieAssoziationen an Bartók aufkommen läßt.) Erst eindrittes Thema, bei Ziffer 14 beginnend, steht dannschlicht in der Dominante; aber nicht in der von Fis,sondern von C. In diesem G schließt auch dieExposition, und ohne Schluß- oder Überleitungs-gruppe beginnt bei Ziffer 18 in derselben Tonart dieDurchführung. Diese ist nun weniger vomAufsuchen entfernter Tonarten gekenn zeich net – ineinem Satz, der durch Fis und C abgesteckt ist, gibtes keine entfernten Tonarten mehr – als von ver-schiedenen Ansätzen, das erste und dritte Thema imBlech miteinander durchzuführen. Interessant ist ebenfalls der Vorgang, der zur Reprisedes dritten Themas führt. Es setzt nämlich zuerst inEs an, der Tonart des zweiten Themas, bricht ab,spielt den Einsatz noch einmal in seiner eigenenTonart durch, in G, um nach vier Takten noch einmalabzubrechen. Erst der dritte Versuch bringt mit einerHalbtonrückung nach unten den erlösenden Einsatzund den Fortgang in der Haupttonart. Man könntemeinen, daß durch diesen Vorgang das Prinzip derKatharsis in der Sonatenreprise thematisiert und dasAufsuchen der Haupttonart durch ein Nebenthemazum Gegenstand satztechnischer Grübelei gemachtwurde. Diese Beispiele sollten zeigen, wie Korngold aufseine Weise versuchte, in einer Zeit, die ihm dasEnde der Tonalität vor Augen führte, diese durchneue Sinnfindungen noch zu legitimieren. Ob dasgelingt, mag dahingestellt bleiben; auf jeden Fallkann man ohne Übertreibung behaupten, daß der -maßen intensive Gedanken über musikalische Pro -bleme, wie sie dieser Sinfonie einkomponiert sind,dem jungen Korngold fremd gewesen wären.

Korngold hat in fast allen Werken, die nach demKrieg entstanden sind, Themen aus Filmmusikenverarbeitet, die er in Hollywood komponiert hatte. Inder Symphonie in Fis wurde vor allem das Adagio,ein breit angelegter, an Bruckner und Mahler erin-nernder langsamer Satz, von einem Thema aus ThePrivate Lives of Elizabeth and Essex angeregt,während im vierten eines aus Kings Row anklingt.Trotz bisweilen gegenteiliger Darstellung sind indiesem Umstand keine Verweise auf die jeweiligenFilme enthalten. Meistens ist es auch nur noch dieGrundgestalt eines Themas, die dann in ganz ande-rer Umgebung völlig neu behandelt wird. Das

VI

Thema war stets die zentrale Kategorie vonKorngolds Verständnis vom Komponieren und re -präsentierte den Großteil seiner musikalischenVorstellungskraft. Deshalb erscheint es verständlich,wenn er diese Themen nicht für immer auf derTonspur eines Filmes verkommen lassen wollte. Unglücklicherweise hielt der Besuch in der AltenWelt nicht, was Korngold sich davon versprochenhatte. Die geplanten Aufführungen seiner Werke lie-fen, wenn überhaupt, nur unter größten Schwierig -keiten ab, was seinen Niederschlag auch in derSinfonie fand. Im Juli 1949 schrieb Korngold nochan seine Mutter in Hollywood: „,… Ich könnte alsobehaupten, daß meine Europareise bisher ziemlicherfolgreich verlaufen ist!‘ Nun, im Oktober 1950,hatte sich seine Meinung über den Erfolg seinerReise grundlegend geändert. Er saß wieder, vor sichhingrübelnd, stundenlang auf einem Platz underklärte, er habe die Lust an der Komposition derSymphonie verloren.“1 Wenn der Anschein nichttrügt, ist diese Enttäuschung aus dem letzten Satzherauszuhören. Die Wiederholung des Schlusses desersten Satzes am Ende des letzten (mit einemangehängten Crescendo) scheint dem Finalproblemauszuweichen und wirft ein Licht auf die Ver -zweiflung, die bei Korngold einsetzte, nachdem ersich mit dieser Sinfonie so viel vorgenommen hatte.Dennoch, oder vielleicht gerade wegen dieser miß -lichen Umstände und des Niederschlages, den sie imWerk gefunden haben, repräsentiert diese Sinfonieein Stück Gattungsgeschichte in einer Zeit, dieschon keinen Sinn mehr dafür zu haben schien. Auch die Uraufführung der Sinfonie im Oktober1954 in Wien während einer weiteren, schon we -sent lich ernüchterter angetretenen Europareise,geriet zum Fiasko. Zu wenige Proben und eine man-gelnde Aufführung veranlaßten Korngold, den Mit -schnitt dieses Konzertes für den Rundfunk löschenzu lassen. Erst 1972, 15 Jahre nach Korngolds Tod,machte eine Platteneinspielung mit Rudolf Kempeund den Münchner Philharmonikern das Werk ineiner angemessenen Interpretation zugänglich undin den späten 80er Jahren konnte endlich durch diezunehmende Anzahl weiterer Aufführungen undEinspielungen die Sinfonie als das erkannt werden,was sie ist: eines der Hauptwerke von ErichWolfgang Korngold.

Helmut Pöllmann

way in a completely different context. In Korn gold’smind the musical subject was always the centralcompositional concept; it constituted the major ele-ment in his musical imagination. Hence it seemsunderstandable that he did not want to leave thesesubjects to moulder in a film sound track.Unfortunately Korngold’s visit to the Old World didnot live up to his expectations. Plans to perform hisworks could be realised, if at all, only with extremedifficulty, a fact which also left its mark on theSymphony. In July 1949 Korngold was still writingto his mother in Hollywood: ‘“. . . so I could say thatmy trip to Europe has been fairly successful up tonow!“ But by October 1950 he had completely changed his mind regarding the outcome of his trip.Once again he would sit brooding for hours in thesame place, declaring that he had lost all pleasure inthe composition of the Symphony.’1 Unless appear -ances are deceptive, this disappointment can beheard in the final movement. The repetition of theending of the first movement at the end of the last(with an added crescendo) seems to be a way ofside-stepping the problem of how to end the work,and sheds some light on the despair which besetKorngold, who had intended to do so much in thisSymphony. Nevertheless, or perhaps preciselybecause of these unfavourable circumstances and themark which they left on the work, this Symphony ispart of the history of the genre in an age whichappeared to have lost all ability to appreciate it.

The Symphony was first performed in Vienna inOctober 1954 during a further trip to Europe, a tripwhich this time, however, was undertaken in a con-siderably more sober frame of mind. It was anotherfiasco. Too few rehearsals and an inadequate per -formance led Korngold to withdraw the recording ofthe concert that had been made for the radio. It wasnot until 1972, 15 years after Korngold’s death, thatan adequate interpretation of the work was madeaccessible in a gramophone recording with RudolfKempe and the Munich Philharmonic. Then with thegrowing number of further performances andrecord ings in the late 80s it at last became possibleto appreciate the Symphony for what it is: one ofErich Wolfgang Korngold’s major works.

Helmut PöllmannTranslation: David Jenkinson

1 Luzi Korngold, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Wien 1967, S. 951 Luzi Korngold, Erich Wolfgang Korngold (Vienna, 1967), p. 95.

VII

Flutes 1-3 (3 doubling Piccolo)Oboes 1, 2Clarinet (B�)Bass Clarinet (B�) 1,2Bassoons 1, 2Double BassoonHorns (F) 1-4Trumpets (C) 1-3Trombones 1-4TubaTimpaniPercussion

CymbalsGongLarge drumGlockenspielXylophoneMarimba

HarpPiano (and Celesta)Violin I 16Violin II 14Violas 10Violoncellos 10Double basses 8

Duration: approx. 55 Minutes

3 Flöten (3. auch Piccolo)2 Oboen2 Klarinetten in B1 Baßklarinette in B2 Fagotte1 Kontrafagott4 Hörner in F3 Trompeten in B4 PosaunenTubaPaukenSchlagzeug

BeckenGongGroße TrommelGlockenspielXylophonMarimbaphone

HarfeKlavier (auch Celesta)16 Violinen I14 Violinen II10 Violen10 Violoncelli8 Kontrabässe

Aufführungsdauer: ca. 55 Minuten

ORCHESTRATION/ORCHESTERBESETZUNG

pizz.

Kontrabaßdiv.

pizz.

pizz.

pizz.Violoncello

div.

pizz.

pizz.Violadiv.

pizz.

pizz.

Violine IIdiv.

pizz.

pizz.Violine I

div.

pizz.Moderato ma energico

Klavier

Schlagzeug

Marimbaphon

Kontrafagott

2

Fagott

1

Klarinette(B)

1

Moderato ma energico3 3

8b

I

EE 7043

SYMPHONY IN Fop. 40

© 1977 Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG, MainzErnst Eulenburg & Co GmbHNo. 8048

Erich Wolfgang Korngold(1897–1957)

Kb.div.

Vcl.div.

div.Vla.

Viol.div.

II

Viol.div.

I

Klav.

Schlzg.

Kfg.

2

Fag.

1

Klar.(B)

3 3

3 3

3

3

3 33 3 3 3

Marimbaphon

1

8b 8b 8b

2

arco 3

arco 3

arco3 3 3 3

3arco 3 3 3

arco 3

arco 3

3arco

3 3 3

3

33

3 3

3

3

33

1 3 3

Klar.(B) 1

Baßkl.(B)

1

2

Fag.

Kfg.

Hr. (F)

Schlzg.

34

Klav.

Viol. I

IIViol.div.

tutti

Vla.div.

Vcl.

Kb.

div.

div.

Marimbaphon

8b 8b

3

Kb.div.

3 33

33

6 6

pizz. arco3div.

Vcl.3 3

33

36 6

pizz.arco

3

3

33

3 6 6 6 3 3

Vla.div.

3

33

3 6 66 3 3

33

3

33 6 pizz. arco 3

div.Viol. II 3

33

36 6 pizz. arco

3

Viol. I

33

3

3 6 6 3 3 3 3

Klav.

Schlzg.

Marimbaphon

Hr. (F) 34

3

Kfg.

2

Fag.

1

Baßkl.(B)

33

Klar.(B) 1

33

3

3

3

3

3

8b 8b

4

3

3

3

3

6

6

pizz. 33

3

366333366pizz.333366pizz.

3

3

3

366pizz.

3

3

3

3

6

6

p

i

z

z

.

3

33

3

6

6poco

2

Schlzg.MarimbaphonKb.div.

div.Vcl.

Vla.div.

div.Viol. II

Viol. I

Klav.

Kfg.

Fag.

1

2

Klar.1

1

2

Fl.

(B)8b5

div. Tutti arco

arco

pizz.arco

3

arco

3

arco

33

3 3 33

poco3

33 3 3

poco3

3

33 31.Fl.12

1Ob.

3a 2Klar.(B)(B)Baßkl.1

2

2

1Fag.

Kfg.

Hr. (F) 3

Schlzg.MarimbaphonKlav.Viol. I

Viol. IIdiv.div.div.

Vla.

Vcl.Kb.

338b6

Kb. 3

Vcl.

div. tutti

7

3Vla.(unis)arcodiv.

7

3Viol. II

(

u

n

i

s

)

div.unis

73Viol. I

p

o

c

o

r

i

t

.

a tempo

73Pk.3

marc.

Tr. (B)

12

3

43

3.

a

2

3

Hr. (F)12

a 232

3

Fag.1

3

2

3

Klar.

(B)

1

3

1.

Fl. 12a 2 poco rit.3a tempo7

3

7

Kb.3

3

3 3

Vcl.3 3

3 div. 5

3

Vla.3

3 3

Viol. II

3

div.

3

3

Viol. I

poco accel.

33 3

(poco più)

Pos. 1poco

43

3 3 3.

Hr. (F)

12

3 a 2

Fag. 12

a 2

3

33

Baßkl.(B)

3

3 3

Klar.(B)

12

3 33

Ob. 21

3 3

a 2

3

Fl. 12

a 2

poco accel.

3

(poco più)

div.

a 2

8

Kb.3 div.

3

Vcl.

(unis)3

7

3

Vla.

6

73

Viol. II

7

3

Viol. I

div.(unis) a tempo

73

Pk.

3

marc.

Pos. 1

poco

Tr. (B) 12

3

34

3. 3

Hr. (F)

12

a 23

Fag. 12

3

Klar.(B)

12

3

Ob. 12

Fl. 12

4 a tempo a 2

73

9

Kb.

3 63 6 3 3 3

Vcl.

6 66 6 6 6 6 6

Vla.

6 66 6 6 6

6 6

Viol. II6

6 6 6

Viol. I

poco string.3

3

43

a 2 3 3Hr. (F)

12

a 2 3 3

Fag. 12

3a 2

33

Klar. 12

3 33

div.

(B)

poco string.5

6

Kb.3 3 3

3

Vcl.3 3 3

div. 5

3

3

Vla.3 3 3

Viol. II

3 3

3

Viol. I

poco accel.

3 3 3

(poco più)

Pos. 1poco

43

3 3 a 2Hr. (F)

12

3 a 2

Fag. 12

a 2

3

3 3

Baßkl.(B)

3

33

Klar.(B)

12

3 33

Ob. 21

3 3

a 2

3

Fl. 12

poco accel.

3

(poco più)

a 2

div.

8

10

Kb.div.

Vcl.div.

6 6

Vla.

Viol. II

6 6

Viol. I

rit. Tempo I

Klav.

Schlzg.

Marimbaphon

Pk.

Tb.

43

Pos.21

Tr. (B) 23

1

43

a 2Soli

3 3

Hr. (F)21

a 2Soli

3 3

Kfg.

Fag.

(B)

21

Ob. 21

Fl. 21

8

Picc (3)

Tempo I 6rit.

Baßkl.

Klar.(B)

a 2a 2

12

a 2

8b

11

Kb.

3 3 3 3 33 3

Vcl. 3 3 3 3 33 3

Vla.3 3

3

3 3

Viol. II

3 33

3 3

Viol. I3 3

33

3

Klav.

Schlzg.

Marimbaphon

Pk.

Tb.

34

Pos.

12

Tr. (B)123

34

3 3

3 3Hr. (F)

12

3 3

3

Kfg.

Fag. 12 3 3 3

3

3

Baßkl.

3 3 3

Klar. 12

3

3 3

Ob.

3

3

Fl.3

3 3

(B)3

3

3

3

3

3

a 2

a 2

a 2

a 2

3

3

a 2

div.

1

1

2

2

(B)

8b

a 2

a 2

a 2

12

Kb.

Vcl.

Vla.

Viol. II3 3

3 3 3 33

Viol. I3 3

3 3 3 33

Klav.

Pk.

Tb.

Pos.3

12

43

Hr. (F)

12

Kfg.

2

Fag.

1

Baßkl.(B)

Klar.(B)

12

Ob. 12

3

Fl. 12

3 3

3

a 2 a 2

1.

1.

a 2 Soli

a2.

cresc.

cresc.

cresc.

3

3

cresc.

div.

8b 8b

13

3

Kb.div. 3

Vcl.

div.7 3

Vla.

div.unis. 7

3

Viol. II

7

3

Viol. I

poco rit. a tempo

7

3

8b

Klav.

Pk.3

marc.

Tb.

Pos.321 1. 3.

3

Tr. (B) 21

3

43

a 2 3Hr. (F)

12

3

Kfg.3

23

Fag.1 3

Baßkl.(B)

37 3

Klar.(B) 2

1

37 3

Ob. 12

1.

3

23

Fl.

17 3

Picc. (3)poco rit. 7 a tempo

3

14

Kb.

unis.

3 3 3

3

Vcl. 3 3 3

3

3

3 35

Vla.div.

3 3 3

5

Viol. II3 3

35

Viol. I

poco accel.

3 3 3

div.poco più

Klav.

Tr. (B) 12

3

34

3 a 2Hr. (F)

12

3 3 a 2

2

3 3 3Fag.

1 3 3 3

Baßkl.(B)

3

3

Klar.(B)

12

a 2

3 3

Ob. 12

3 3

Fl. 12

Picc. (3)

poco accel.

3

poco più

15

Kb.

Vcl.div.

Vla.div.

Viol. II

Viol. Idiv.

Klav.

Pk.

34

Hr. (F)

12

Kfg.

2

Fag.

1

Baßkl.(B)

Klar.(B)

12

Ob. 12

div.

8

8b

16

Kb.div.

3

Vcl.div.

Vla.div.

Viol. II

Viol. I

Klav.

34

Hr. (F)

12

Fag.

23

1

L’istesso tempo, cantabile

L’istesso tempo, cantabile

9

espr.

8b

17

3 3

Vcl.div. in 3

33

3 3

Vla.div. in 3

3

3

Viol. II

Viol. I

Tr. (B) 1

con sord. 3

34

Hr. (F)

12

dolce 3

23

Fag.

1

Baßkl.(B)(B)

Klar. 12

a 2 3

Ob. 13

2

Fl.

15

Solo 1.

3

3

1. Pult

1. Pult

espr.

espr.

(B)

div.

18