Kingfisher 2004

-

Upload

college-of-humanities -

Category

Documents

-

view

234 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Kingfisher 2004

The Kingfisher 2005

A P U B L I C A T I O N O F T H E

C O L L E G E O F H U M A N I T I E ST H E U N I V E R S I T Y O F U T A H

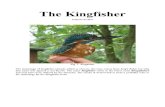

“What does not change is the will to change,” begins Charles Olson’s

poem “The Kingfisher.” In Greek mythology, the kingfisher paradoxically

is associated both with transformation — the story of Alcyon and Ceyx

whom, in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Zeus turned into a pair of birds — and

with the idea of “halcyon days” — a period of calm seas and of general peace and serenity.

In Gerald Manley Hopkins sonnet, “As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame,” the

iridescent plumage of this spectacular bird is celebrated as an image of both the multiplicity and

unity of God’s creation. And in Amy Clampitt’s poem, which bears the same title as Charles

Olson’s, “a kingfisher’s burnished plunge, the color/of felicity afire, came glancing like an arrow/

through landscapes of untended memory.”

Transformation, calm, multiplicity, unity, felicity, disturbance, revelation. To poets, the kingfisher

magically embodies all of these — a joining of opposites, a preservation of variety, an embrace

of challenge and change.

The College of Humanities extends this poetic tradition by adopting the kingfisher as a symbol

of these fundamental concepts which we in the Humanities practice and teach. We believe in

their profound and lasting importance. We are pleased to offer you this inaugural issue and

thank you for the role you play in promoting our mission of lifelong learning.

Robert Newman

Dean

College of Humanities | The University of Utah255 S. Central Campus Drive | 2100 LNCO | Salt Lake City, UT 84112

801.581-6214 | fax 801.585.5190

2 DEPARTMENTS, CENTERS, NEW INTERDISCIPLINARY INITIATIVES

3 THE COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AT A GLANCE

4 DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION

The United Consumers of America or, Is there a Citizen in the House?

6 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH

Excerpt from “Resistance to Literature”

8 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY

The Elements of Effective History Instruction: One Professor’s View

10 DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE

Valuing Multilingualism

12 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS

Language Preservation

14 DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY

How Bioethics Becomes Even More Intense

16 MIDDLE EAST CENTER

Overheard...

18 TANNER HUMANITIES CENTER

Diversity and Democracy

20 ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAM, LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES PROGRAM, INTERNATIONAL STUDIES PROGRAM

Civil Society

22 UNIVERSITY WRITING PROGRAM

Writing , The Ghost Major

24 REACHING OUT TO THE COMMUNITY

26 LIFE IN ITS FINER MEANINGSThe Gordon B. Hinckley Endowment for British Studies

28 WEST SIDE STORIESA Group of U of U Students Discovers The Power of Storytelling

32 THE NATURAL WORLDA Program to Create an Ethic of Place

36 FROM THE ARCTIC TO THE REDROCKA Celebration of Environmental Humanities

38 POETRY

41 O.C. TANNER HUMANITIES HOUSE

42 CONVOCATIONMay 6, 2004 ta

ble o

f con

tent

s T

he K

ing

fis

he

r 2

00

4

The College of Humanities is the second-largest college on campus and is at the core of

the University of Utah’s mission and the experience of higher education. The Humanities

offer of an approach to a conscience in a complex world.

Professors study and teach essential skills and tools for thinking and communicating that

apply readily to everyday practical situations, emphasizing a commitment to community,

and awareness of our integral function in a multifaceted global culture. Through research

and pedagogy that illustrate healthy questioning and shifting frontiers, and attempts at

inclusion and connection, we offer approaches that are fundamentally democratic. We

thereby help to produce better-informed, thoughtful world citizens with a foundation for

nuance and flexibility.

All undergraduates enroll in Humanities courses at some point in their academic pursuits.

Each year, about 2500 of these students choose to focus their studies on Humanities,

choosing from the College’s 21 majors. The College confers one-fifth of the University’s

diplomas annually. Graduate students number about 400 and have matriculated into

one of 14 Master’s and 13 Ph.D. programs. The College’s 170 tenured and tenure-

track faculty have published 60 books and more than 300 articles in the past three years;

possess international distinction as scholars; are the most frequent

winners of University teaching and research awards; and are the most diverse in terms of

ethnicity and gender in the University.

T H E C O L L E G E O F H U M A N I T I E S A T A G L A N C E

But life is short, and truth works far and lives long: let us speak the truth.

-Arthur Schopenhauer, 1818

CommunicationEnglishHistory

Languages & LiteratureLinguisticsPhilosophy

CENTERS

Middle East CenterTanner Humanities Center

University Writing Program & Center

Masters DegreesEnvironmental Humanities*

Asian Studies*—

MajorsInternational Studies

—Minors

Animation StudiesPeace and Conflict

Latin American StudiesApplied Ethics

—Centers & ProgramsApplied Ethics Program

Documentary StudiesCenter for American Indian Language*

* Evolv ing programs or centers that are pending Univers i ty approval

NEW INTERDISCIPLINARY INITIATIVES

DEPARTMENTS

2 3

More than 1700 undergraduate students have declared Communication their major, making it the single largest major on the entire University campus.

NEW PROGRAMS ADDED IN 2004

• Interdisciplinary minor in Animation Studies

• Interdisciplinary minor in Peace and Conflict Studies

• Masters in Conflict Resolution

• Values and Ethics initiative

OF INTEREST…With the financial support of the National Science Foundation, Professor Tarla Rai Peterson is exploring ways to avoid natural resource conflict by improving decision makers’ abilities to present scientific and technical information to their constituents. Peterson is also coordinating the public outreach component of a Department of Energy grant. Her role centers on strategies to help people negotiate conflicting perspectives toward climate change, economic development and local and regional government.

—The department’s Conflict Resolution program continues to flourish. Having expanded beyond traditional “alternative dispute resolution,” the program now covers a broad range of topics, including facilitation, consensus building, facilitated negotiation and several forms of mediation and restorative justice.

—With the generous support of a $1 million grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Professors Maureen Mathison and Ann Darling have established a comprehensive – and successful – educational experience for College of Engineering students, focused on speaking, writing and teamwork skills.

STELLAR FACULTY…

10 books published in the past three years10 faculty teaching awards, including 5 prestigious Distinguished Teaching Awards

D E P A R T M E N T O F C O M M U N I C A T I O N

THE UNITED CONSUMERS OF AMERICAOR, IS THERE A CITIZEN IN THE HOUSE?

“We are a nation of consumers.” So say the media, our recent presidents, most CEOs, and just about everybody else. We barely pause when the New York Times refers to mainland China not as a people or a country but as an emerging market of 1.25 billion consumers.

Why are we no longer citizens? My undergraduate students tell me that the term sounds old-fashioned — a throwback to the pre-electronic age. At the same time, young people know, or feel, that being a consumer isn’t what life is all about.

In 1900, “consumption” referred to waste and to tuberculosis. With the birth of lifestyle advertising in the 1920s, advances in mass production in the middle of the century, and the infusion of marketing into all domains of society in the 1990s, consumption became not simply something we do to live but what we do and who we are.

The consumer movements of the 1960s-70s brought us needed information about the products and services that we were buying. Still, the overall trend of the past several decades has been to elevate consumption to a (the?) main goal of our society. As writer Adam Gopnik observes, consumerism was the 20th century’s “winning ism.”

So, what’s wrong with giving people what they want? One major problem is that a consumer has rights but not necessarily a lot of responsibilities. A citizen, by contrast, is actively engaged in the public realm beyond the self and the moment. The other big problem is that the drive to consume more and more is a vicious cycle. The basic message of advertising is “You are not okay. You’d better buy more stuff.” Instead of paving the road to happiness, this message keeps people in a pothole of permanent dissatisfaction.

The ways we talk about ourselves, our values, and our goals are worth listening to. For example, today’s popular student-as-consumer metaphor is valuable for insisting on greater accountability in education, but it fails to engage the process of learning to learn that runs through a liberal-arts education.

Consumers we are, but that’s not all.

George Cheney, Professor of Communication

4 5

Students in the English Department benefit from programs such as British and American Literature, American Studies, Creative Writing, English Education, and Rhetoric and Composition. The Department’s Ph.D. program in Creative Writing is consistently ranked among the top ten in the country.

Somebody Ought to Write a Poem for PtolemySomebody ought to write a poem for Ptolemy,So ingenious in being wrong, he was almost a poet.Can anyone follow his configurations?How he cut a tortured path for every planetUntil his numbers matched what he could see,Every one spectacularly wrong.You would think, in all those years of calculations,He would, at least, have suspected a simpler way.Maybe he even knew it all along – The stationary sun, ellipses, everything But kept it to himself as too unseemlyOr to save his pregnant wife from all that spinningAnd wait beside her in a quiet placeThat he, himself, had rendered motionless.

Jacqueline Osherow, 2004 University Distinguished Professor

OF INTEREST…

Professor Meg Brady and the students in her “Folklore Genres: Life Stories” class interviewed, recorded and transcribed the fascinating life stories of senior citizens living in Salt Lake’s Multi-Ethnic Senior High-Rise.

—Among the department’s alumni are such distinguished writers and leaders as Wallace Stegner, Terry Tempest Williams and Gordon B. Hinckley.

D E P A R T M E N T O F E N G L I S H

Excerpt from “RESISTANCE TO LITERATURE”

It would be too much to suggest that literature, preserving the ghostly knowledge of our discarded past, can somehow heal the breach that has opened up between human beings and the phenomenal world, but surely it goes some distance in that direction. I also think it’s necessary to keep faith with the readerly absorption that protects some space where the empirical world – the world of necessity – does not press us to acquire some immediately profitable knowledge of its operations. I firmly believe that critical analysis can intensify, rather than disrupt, this relation.

I enjoy reading art history, but I’ve realized over the years that its value for me lies less in the particular arguments than in its making me look and look again at the images it is describing or decoding, and I distrust any literary criticism that does not make me want, indeed compel me, to reopen the book of poetry or fiction and let its language do its work again and perhaps differently. This is certainly the primary business of literary instruction, to extend and enlarge the scope of rapt attention and to allow students to see that the effects of the text have not exhausted themselves at a first or even second or third reading.

It is an article of faith, perhaps a superstition, with me that I never teach a literary text, however familiar, without rereading it, but it also turns out to be necessary: the text is never the same as I remembered it. Somehow, magically, the text I am now reading is also the one my students have read. Whether by some subtle shift in the Zeitgeist, some change in the institutional context, some invisible reconstitution of the community of readers, we meet on the same ground, if not always with the same responses, questions or enthusiasms.

Barry Weller, Professor of EnglishDirector of Graduate Studies

6 7

The Department of History offers courses ranging from ancient Mesopotamia, Greece, and Rome to the modern Middle East, Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Students are trained in critical thinking, analysis, and effective communication.

STELLAR FACULTY…In the past year, four history department faculty members won College or University-wide recognition for their excellence in teaching. Bob Goldberg was awarded the Hatch Prize, the University’s most prestigious teaching award; Janet Theiss received the Ramona Cannon Award for Teaching Excellence in the Humanities; and Beth Clement was named this year’s Honors Distinguished Professor by the University Honors Program. Ron Coleman was honored by the Office of the Associate Vice President for Diversity with one of this year’s University Diversity Awards.

RECENT EMERITI…Jim Clayton and Alan Coombs, both respected professors in the History Department, retired this past year from full-time status in the department. Jim Clayton had been with the University for 41 years, and Alan Coombs had been here for 36 years. Both have had a significant impact on the department and on students, and they will be missed.

OF INTEREST…Congratulations to Mira Green, a graduate student in the History Department, who traveled to Rome this summer to attend the summer program at the American Academy, the premier American program in Ancient Studies in Italy.

—Yana Walton, a junior pursuing a double major in History and Gender Studies who is particularly interested in gender roles in the United States and Asia, recently was honored with the first annual Susannah Topham Memorial Scholarship, established by Barry and Trisha Topham, in memory of their daughter. The Topham Scholarship covers the cost of tuition and books for one year.

D E P A R T M E N T O F H I S T O R Y

THE ELEMENTS OF EFFECTIVE HISTORY INSTRUCTION: ONE PROFESSOR’S VIEW

The highest goal of teaching is to empower students to think and learn for themselves. Good teachers inspire students to reach beyond themselves; they equip students to do work they didn’t believe themselves capable of doing; they provoke strong reactions by challenging students’ assumptions and inspiring their curiosity.

Three things are essential to the success of history students. First, students need to learn that “doing” history is an active intellectual process that generates interpretation and meaning, not simply a record of facts. It is possible—indeed, very common—for people to agree on all the salient facts of a situation, and yet to draw very different conclusions. Second, students need to analyze sources from the period we are studying in order to appreciate the texture of the past on its own terms. Third, to work with the information and ideas presented to them, students need to cultivate the ability to read with discernment, to think critically, and to write clearly and effectively.

History professors introduce students to the past on its own terms, and at the same time empower them to think through interpretive problems and make arguments about its meaning and relevance. The study of history inspires contradictory reactions in students. On the one hand, they immediately recognize parallels between past events and current issues. The study of history provides insight and leverage for modern problems. On the other hand, these parallels are never simple; the study of history brings with it many elements of shocking strangeness. The past speaks to us by analogy, but its analogies are always imperfect. This paradox—the persistence of essential problems in a world of constant, dramatic change—is the engine of history.

Eric Hinderaker, Professor of History Chair of the Department of History

8 9

D E P A R T M E N T O F L A N G U A G E S & L I T E R A T U R E

American Sign LanguageArabic

ChineseClassics

Comparative LiteratureFrench

GermanModern Greek

HebrewItalian

JapaneseKoreanPersian

PortugueseRussianSpanishTurkish

STELLAR FACULTY…Todd Reeser, an Assistant Professor in French, recently completed an academic year as a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow, at the National Humanities Center in North Carolina. Utah’s first representative at the Center, Reeser was selected as one of only 35 scholars from a pool of 550 applicants. While in residence there, Reeser completed his first book, Moderating Masculinity in Early Modern Europe, which is currently under review. He is at work on a second book on the reception of Platonic sexuality in Italy and France in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

The Department of Languages and Literature is committed to fostering a critical and comprehensive understanding of diverse cultures, through the study of literature, language, art, ideas, history and socio-political contexts.

OF INTEREST…Languages and Literature courses are multicultural, interdisciplinary, and integrate language, literature, film, music, popular culture, and media across geographical boundaries. Current departmental initiatives focus on three areas: developing lecture series on film, literature, and cultures around the world; developing a series of courses with a comparative focus that bring together various linguistic and national traditions; and fostering service learning and community outreach programs with various language communities in the area.

—The department also offers an extensive array of study abroad programs in countries such as Chile, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, and Spain, which afford students unique opportunities to live the languages and cultures of the host countries.

VALUING MULTILINGUILISM

This past February, night talk show host Conan O’Brian took his show to Canada. The Canadian government had decided to sponsor the show in an attempt to regain tourist trade lost during the SARS epidemic of 2003. The visit ended in scandal over a skit involving a sock puppet and a French Canadian couple: The puppet, greeting visitors to the Quebec City Winter Carnival and having ascertained the provenance (and separatist leanings) of the unfortunate couple, screamed at them “You’re in North America – learn the language!”

Through the puppet, Conan gave voice to America’s ambivalence towards other tongues. On the one hand, there exists a fundamental belief that the English language must be the tie that binds. On the other hand, policy makers, government officials and journalists routinely lament the populace’s lack of linguistic expertise, expertise required for the nation to compete in an increasingly global world.

In an article on multiculturalism and the study of foreign language, Margaret Talbot remarks, “Americans don’t like to learn difficult languages.” It is true that you can’t produce experts in a matter of weeks or months. It takes a long time and a lot of work to become usefully proficient in another language. But what is also true is that you can’t expect people to pursue a path that isn’t valued by society at large. Not many students want to risk their GPA on Russian, Urdu or Turkish. They don’t see the point. And therein lies the problem. There has to be a point other than the shifting target provided by the latest headlines.

In fact, there are all sorts of compelling reasons to study a foreign language to a truly proficient level. A student may be one law degree recipient among many, yet another accountant or aspiring young physician, yet if they couple these goals with professional proficiency in a language other than English they will find unique opportunities. To support this goal, we need to find a way to separate national identity from the view that promoting proficiency in other languages is somehow un-American. We need to find a way to value and reward linguistic and cultural competence. In short, we need to turn linguistic diversity into a good thing.

Jane Hacking, Associate Professor of Russian

10 11

Linguistics is the study of language structure, use, variation and change. Linguistics students are exposed to a scientific approach to the study of human language and develop an understanding of the central role that language plays in human society and human cognition. The Department, which has 12 regular and three auxiliary faculty members, currently serves more than 370 undergraduate students. Fully two-thirds of students in the Linguistics department are focused on teaching English as a Second Language (ESL).

OF INTEREST…Through the various ESL teacher education programs, including the ESL Endorsement Program with the local school districts, the Department has produced more than 1000 teachers in the past ten years.

INNOVATIVE RESEARCH…With the generous support of funding from the National Science Foundation, faculty members have undertaken to preserve, transcribe and translate the extensive collection of Wick R. Miller’s Shoshone and Goshute tapes, recorded in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Dr. Miller, an internationally recognized linguist, was the founder of the Linguistics Program at the University of Utah. Documentation and translation of these tapes is critical to the language revitalization efforts of the Shoshone and Goshute tribes – and critical to the preservation of a unique and important native language that is at risk of extinction.

—Building on the tremendous faculty strength in Native American language and culture preservation, the Linguistics Department has recently announced an emerging Center for American Indian Language. The Center is dedicated to: (1) urgent and ambitious research on the endangered languages and cultures of Native America; (2) the training of students to address scholarly and practical needs involving these languages and their communities of speakers (with training for native speakers and those whose heritage languages are involved); and (3) working with community members towards linguistic and cultural revitalization where languages and cultures are endangered.

D E P A R T M E N T O F L I N G U I S T I C S

LANGUAGE PRESERVATION

As a linguist, I have been asked by the Northwest Band of Shoshoni to document the imperiled dialect of their language. I can do this through the creation of a reference grammar, a dictionary and a fully analyzed collection of oral narratives. However, beyond documentation, it takes a community with fluent speakers to “revitalize” a language’s infinite capacity for creative change.

Despite the efforts of linguists to document Shoshone dialects, they remain endangered. They are at risk – along with most of the world’s 6000 languages – of being overwhelmed by the few languages spoken by hundreds of millions. The culprit? Cultural globalization. Kids shift from “local” to “world” languages, opting for the winners of the language wars as easily as they buy logo T-shirts.

Lest we disparage language documentation, recall the smiling Etruscans. As intriguing as any ancients, they’re mute! Only un-deciphered fragments remain of their meager tomb inscriptions. The mind leaves no potsherds – an unrecorded language, no bones.

So what? Survival of the Fittest! But when these fragile languages are lost – we all lose. Our culturally homogenized, ten billion descendants will talk about very little, in the few languages left. The ethnosophere is shrinking faster than the biosphere. We can now clone a dodo, but not a language. Jurassic Park for languages? Not even in Hollywood.

The rationale for intervention is clear and multifarious. When we needed quinine, surely a native led us to it. What secret herb or insect awaits translation from an unstudied language? Yet, forget Culture and Science; forget poets and sages; self-preservation alone dictates the rescue of this endangered lore. Language is no museum piece. It’s alive – ever changing. While no written grammar can capture the infinite creativity of a living language, documenting it is better than losing it. Keeping it alive by revitalizing it, when faltering, is better yet. The Northwest Shoshone people have opted for the latter. I’m with them. Consider these utopian words from the Book of Esther 1:22:

“… to every province according to the writing thereof, to every people after their language, that every man should bear rule in his own house and speak according to the language of his people.”

Mauricio Mixco, Professor of Linguistics

12 13

The Philosophy Department is successfully building on its strengths in ethics, applied ethics, philosophy of science and cognitive science. The department seeks to integrate these strengths with one another, e.g., philosophy of biology complements applied work in bioethics and environmental ethics — and with University initiatives — for example, cognitive science complements the research underway at the University’s new Brain Institute.

RECENT EMERITI…

Professor Yukio Kachi recently announced his retirement after 32 years of teaching in the Department of Philosophy. A teacher of Ancient Chinese philosophy and Ancient Greek philosophy, Dr. Kachi was awarded the University Distinguished Teaching award and named a University of Utah Presidential Teaching Scholar in 1997. He will be sorely missed by his students and colleagues.

NEW FACULTY…

Shaun Nichols, newly appointed as a full professor, has been teaching for the past ten years at the College of Charleston. His fields are cognitive science and philosophy of psychology. Nichols’ most recent book is Sentimental Rules: On the Natural Foundations of Moral Judgment, to be published this year by Oxford University Press. This year he will teach a course on free will and a seminar on the cognitive science of religious belief, among other offerings. A fine scholar, Nichols is a marvelous addition to faculty strengths in cognitive science and in ethics.

D E P A R T M E N T O F P H I L O S O P H YHOW BIOETHICS BECOMES EVEN MORE INTENSE

Bioethics—the study of moral problems in medicine—is a hot field,ranging from doctor-patient truthtelling to stem cell research to physician-assisted suicide. But bioethics is often taught in an across-the-board way, addressing a full range of topics far too quickly.

What if you took a more focused look at a concentrated set of issues in medicine? Recently, Jay Jacobson MD and Charles B. Smith MD, both infectious-disease specialists, and I did just that, by co-teaching a course on “Ethics and Infectious Disease.”

When we started, our plan was to examine emerging diseases, antibiotic resistance, and biowarfare, which we did. But because it’s essential to understand technical medical issues as well as the philosophical ones, we provided updates on new infectious disease information based on reports from the Centers for Disease Control.

First, there were a few isolated reports trickling in from China of an unknown syndrome; we didn’t pay much attention. We had read about classic problems like the plague in Greece at the time of Thucydides and in medieval Europe, but those seemed problems of the past whose only contemporary analogue was AIDS. But reports kept trickling in. Nobody knew what to do, and although the condition was given a name, SARS, nobody knew how to stop or treat it. It was spreading, and often fatal. Many in our class were pre-med students, and it was becoming clear that SARS affected health-care workers with unusual frequency.

The class became much more serious: are physicians obligated to treat patients with potentially lethal infectious diseases? As the disease appeared just a plane ride away, we debated the ethics of universal involuntary quarantine for anyone exposed, state-required immunization if a vaccine were ever to be developed, and issues of justice about who should get first access to treatment and how health care resources should be prioritized. We were scared, students and instructors alike, since we understood more fully than the public at large just what could be at stake.

Fortunately, SARS was contained, at least as far as we know. But none of us will forget this class experience, with physicians, students and an ethicist, together addressing issues of compelling social concern. We’re preparing to teach the class again in Spring 2005. While we are certainly not wishing for the emergence of another new disease or an episode of biowarfare, we are well aware that real learning happens fast in the real world. What, we are wondering, will happen next?

Margaret P. Battin, Distinguished Professor of PhilosophyAdjunct Professor of Internal Medicine, Division of Medical Ethics

14 15

Since 1960, the MEC has continually secured highly competitive grants from the Department of Education, making it one of the oldest National Resource Centers for Middle East Studies in the United States.

OF INTEREST.. .The MEC and the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, with financial support from the Utah Humanities Council, sponsored a workshop, titled, “Contact Across The Sahara: Caravans, Carpets, Calligraphy,” that attracted 122 teachers, students, and members of the local community. The workshop was free and open to the public and explored how elements of Middle Eastern culture traveled along the caravan routes throughout the known world, bringing new ideas, art forms, and flavors to the surrounding civilizations. The keynote address was given by Terrie Chrones, a culinary historian. Other lectures in the workshop included:

“Across the Sahara-Islamic Influences,” presented by Bernadette Brown, Curator of African, Oceanic, and New World Art at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts. Brown discussed the impact Islam had on sub-Saharan Africa’s art forms and the cultural changes it brought about.

“The Middle East: A Political Update,” presented by Ibrahim Karawan, Director of the University of Utah’s Middle East Center and Professor of Comparative Politics. Karawan discussed the cultural and historical forces influencing the Middle East today.

—This spring, the Center will once again send a delegation of its best students to the National Model Arab League in Washington, DC, where they will be representing Jordan. Additionally, the Center has the distinct honor of hosting the Regional Rocky Mountain Model Arab League on the University of Utah campus (February 2005). Schools from around the region are invited to send a team to this competition, which has grown significantly in recent years, and which requires rigorous and thoughtful preparation on the part of student participants.

M I D D L E E A S T C E N T E R

“There was no military answer, he understood very well, to the challenges of the Palestinian uprising… another reason for Rabin to opt for a political solution. To his dismay, he discovered that the Israelis’ one time legendary stamina was showing signs of erosion and he became doubtful as to their capacity to withstand the threat facing their country. Israeli society, he told me during a flight to the Golan Heights in the spring of 1993, was no longer the mobilized and pioneering society it used to be. It had lost, he told me, its fighting spirit. The question is not whether Rabin was right or wrong; what matters is that this is the way he perceived it at the time.”

Shlomo Ben-Ami, Israel Minister of Public Security

“We tend to think that one conflict is much like another and that conflict in the year 2004 is probably a lot like conflict in the year 1980. Dead wrong... A number of academics seem to believe that because the Cold War brought an era of stability to international relations, that the Cold War in retrospect was not such a bad thing. …20 years ago, two times more people on average lost their lives to conflict than do today and there were twice as many conflicts as there are today. So, contrary to what you would believe from looking at the leering headlines of the press, the situation today is a great deal better. That is one big change.”

David Malone, President, International Peace Academy

OVERHEARD.. .

Each spring since September 11, 2002, the Middle East Center has sponsored a lecture series for the general public on topics ranging from terrorism and the Iraq crisis, to the peace process in the Middle East. The following excerpts derive from the remarks of two of this year’s distinguished lecturers:

16 17

The Obert C. And Grace A. Tanner Humanities Center fosters innovative humanistic inquiry and scholarship. The Center’s public programs create opportunities for lively dialogue among scholars, students and citizens on issues (from ancient to contemporary) pertaining to the human condition. Every year, the Center selects and supports the work of up to eight internal and external residency fellows on the basis of their seminal research projects. Founded in 1988 by Professor Norman Council (then Dean of the College of Humanities), the Center was endowed and renamed in 1995 through a generous gift from the family foundation of Obert C. Tanner, renowned philanthropist and late Professor Emeritus of Philosophy.

OF INTEREST.. .

35 high school teachers from the intermountain area participated in the Center’s annual Summer Teacher Workshops. These workshops focused on understanding linguistic and cultural variation in classrooms.

“This will be useful as I continually work with Latino students and their families. Hearing the historical accounts of Latin Americans broadened my perceptions and helped me to think more globally about different cultures that come to our schools.”

– 2004 Workshop Participant

Katharine Coles“Out of the Cradle: A Memoir of Family and Country”

Lisa Flores“Contested Terrains: Rhetorical Visions of the National Body in United States Immigration Discourse”

Gema Guevara“Challenges to the Nation: Diaspora, Race and Gender”

Mauricio Mixco“Shoshoni Language Maintenance and Revitalization”

Maeera Y. Shreiber (NEH Fellow in Residence)“Dwelling and Displacement: Towards a Jewish American Poetics” Erika Bsumek“Indian-Made®: The Construction and consumption of Navajo Identity, 1860-1940” Dana Luciano“Revisions of Mourning: Loss, Nationality and the Longing for Form in Nineteenth Century America” Hale Yilmaz“Learning, Resisting, Living: Negotiating the Kemalist Reforms in Trabzon, 1923-1938”

2003-2004 FELLOWS

T A N N E R H U M A N I T I E S C E N T E R

DIVERSITY AND DEMOCRACY

Nowhere are issues like “Democracy” and “Diversity” more carefully studied and theorized about, more hotly debated and more controversial, more open to honest discussion and scholarly research, than in American universities: after all, the study and theory of democratic culture and civil society are the very basis of the intellectual debates that have raged across campuses in this country since the 1960’s.

And yet it is very rare that such academic study and theorizing ever leads directly to actual change and implementation at the level of national or international policy-making. We may be the intellectuals and experts who have written the most current and sophisticated scholarly books and articles — on Islamic debates in the Middle East, on race and gender and sexuality in the United States, on the endangered languages of minority populations, and so on; yet rarely are we heard by those in power. At times of national and international upheaval about democratic and civil society in both the United States and abroad (such as is clearly the case at the present time), this disjunction — between scholarly expertise and practical powerlessness–is particularly frustrating. Indeed, it was the parallel and widespread frustration on college campuses at a comparable moment of national and international crisis during the Vietnam War era that led directly to the student protests during the late Sixties and early Seventies.

How can we bridge theory and praxis on issues of national and global policy? How do we cross academic and policy boundaries? We need to merge the study and the actual practice of democracy; we need to learn how to get our message out — and to package our recommendations outside of the hardbound monograph on dusty library shelves.

And we intend to do just that with a focused, College-wide theme for the academic year 2005-2006: “Democracy and Diversity: The Role of the University in Creating Democratic Culture and Civil Society.” We invite all friends and alumni of the College to look forward to, and to participate in, “Democracy and Diversity 2005-2006.”

Vincent J. Cheng, Shirley Sutton Thomas Professor of English,Director, Obert C. and Grance A. Tanner Humanities Center

18 19

A S I A N S T U D I E S P R O G R A M

The Asian Studies program is an interdisciplinary and transregional major crafted from courses offered in a wide variety of departments, including Architecture, Anthropology, Art History, Economics, Geography, History, Languages and Literature, Linguistics, Political Science, Philosophy and Theatre. Areas of emphasis include Art, China, Cultural Studies, Eastern Philosophy, Japan, Korea, Linguistics, Political Science, and Asian History.

—

L A T I N A M E R I C A N S T U D I E S P R O G R A M

This program offers cross-disciplinary approaches to Latin America, a major world region that includes South and Central America, Mexico and the Caribbean. It draws on faculty and courses from the Departments of Anthropology, Economics, English, Geography, History, Languages and Literature, Linguistics, and Political Science, the Ethnic Studies and Gender Studies Programs, and the Colleges of Architecture, Business, and Nursing. Latin American Studies offers students the opportunity to deepen their understanding of this important region and will strengthen the ability of students to interact with Latinas/os both at home and abroad, whether as citizens, in private enterprise or government work.

—

I N T E R N A T I O N A L S T U D I E S P R O G R A M

This new program carries the reputation of being one of the most innovative programs at the Unviersity. While housed within the College of Humanities, it represents a joint venture with the School of Business and the College of Social and Behavioral Science. Courses give students descriptive, analytical and methodological tools to help understand the world and the United States in a global context. It is the College’s fastest growing major, with more than 200 students declaring International Studies as their major last year.

CIVIL SOCIETY

“Civil society” has been one of the most fashionable buzzwords of social science and popular discussion in the past decade. The idea was fundamental in 18th century European thought, and re-emerged in the 1980s as a way of understanding developments in the Peoples’ Democracies of Eastern Europe. Its existence has been seen as a fundamental prerequisite for the existence of democratic political systems. But in the 1990s, even as democracy seemed to spread, it also became apparent that civil society had multiple, often conflicting meanings.

The prominence of civil society in contemporary discussions is an indicator that what have been relatively settled forms of relationships between the political and social, the state of the public, are today in flux. The challenge in maintaining and extending democratic politics will be in re-imagining these relationships in ways that take into account not only western traditions of democracy, but also the aspirations of peoples of different parts of the world for individual liberty, economic well being, security from violence and social support in their lives.

The uncertainty and ambiguity of the meaning of civil society, however, raises questions about the process of inventing — and reinventing — civil societies in different parts of the world with different traditions than the West. There are not going to be simple answers to these questions. Nor for that matter can uniform answers be imposed around the world. Yet the answers that we find to these difficult questions will be, for good or ill, among the most important legacies we leave to the future.

Jim Lehning, Professor of History Director, International Studies Program

20 21

The University Writing Program was established in 1983, one of the first of its kind in the United States. The program offers a Ph.D in Rhetoric and Composition, as well as a minor in Literacy. All of its graduates hold tenure-track positions in higher education, and many have gone on to become directors of writing programs at other institutions.

OF INTEREST…

Last year the University Writing Program had approximately 20 percent of the student body enrolled in its courses – more than 5000 students per academic year.

—

The Western States Rhetoric and Literacy Conference, regularly co-hosted by the University Writing Program, was written up in a national composition journal as one of the best-quality conferences today for those in writing.

—

The University Writing Program is part of a generous $1 million William and Flora Hewlett Foundation Grant that integrates writing, speaking and teamwork into courses offered in the College of Engineering. The goal of the CLEAR project is to improve communication and leadership skills, incorporate ethics into the undergraduate curriculum, and conduct research to better understand how engineers communicate.

—The newly opened University Writing Center, run by the University Writing Program, averaged 70 student contact hours per week in its first year tutoring students on how to improve their writing.

U N I V E R S I T Y W R I T I N G P R O G R A M

WRITING, THE GHOST MAJOR

The history of writing instruction in American universities is an interesting, albeit little known one. From the time of A.S. Hill, a professor charged with creating composition courses at Harvard in the 1870’s, to contemporary times, writing instruction has changed both in focus and purpose. Initially, the focus was on grammar and correctness, traits that demonstrated students’ social standing as they wrote essays about “great” literature, such as the works of Shakespeare. At that time writing instruction was under the umbrella of English Studies, and literature played a dominant role in the teaching of writing. Writing was a means by which to refine one’s tastes, to instruct common folk by instilling in them upper-class ways of thinking.

In the 1970’s the study of writing came into prominence. Researchers such as Mina Shaughnessy and Janet Emig launched the first of many important studies that showed connections between writing and thinking. These early studies helped motivate a research program for the discipline. What constitutes “good” writing? How do students compose? What are the differences between expert and novice writers? What are the rhetorical conventions of various disciplines? How does gender influence writing? What about social class or ethnicity? Questions such as these shifted the exclusive focus of writing from producing the perfect grammatical paper as a measure of appropriateness to how people approach and perform writing from their lived experience in particular contexts.

The variety of university writing instruction offered today prepares students to write in multiple situations. All students earning a bachelor’s degree, regardless of major, are expected to know how to write. Writing is the ghost major.

Looking forward, writing will assume an even greater function in a globalized world as it will be used with increasing frequency and speed to relay information across continents, through different media, and among peoples of diverse backgrounds.

Maureen A. MathisonAssociate Professor of Communication Director, University Writing Program

22 23

RENAISSANCE GUILD The Renaissance Guild, which claims as members some of Salt Lake City’s best and brightest citizens, meets quarterly to engage in intellectually stimulating conversation about a book they have read in common. Recently, the Guild studied four very diverse and thought-provoking books:

Final Harvest , A Collection of Poems, by Emily Dickinson (Robert Newman, Dean, College of Humanities, Facilitator)Terror in the Name of God: Why Religious Militants Kill, by Jessica Stern (Ibrahim Karawan, Director of the Middle East Center, Facilitator)The Riddle and the Knight: In Search of Sir John Mandeville, the World's Greatest Traveler, by Giles Milton(Lindsay Adams, Facilitator)The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, by Anne Fadiman (Kim Lau, Facilitator)

HUMANITIES HAPPY HOURIn his famous essays, Michel de Montaigne observed (c. 1580), “the most fruitful and natural exercise for our minds is, in my opinion, conversation. I find the practice of it pleasanter than anything else in life…” He adds, “Just as our mind is strengthened by communication with vigorous and orderly intellects, it is impossible to say how much it loses and is debased by our constant intercourse and association with mean and feeble intellects.”

The College of Humanities has created a space in Salt Lake City where individuals can exercise their minds through pleasant conversation with vigorous and orderly intellects. This space is called the “Humanities Happy Hour” and it occurs on the third Thursday of each month at Squatter’s Brew Pub in downtown Salt Lake City. Halfway through each Happy Hour, an award-winning professor from the College of Humanities serves an “Intellectual Hors d’Ouevre” — a 10-minute talk on a subject that is timely, timeless and provocative. Intellectual hors d’oeuvres offered in the past have included, “Pleasure and the Good Life (or Cows, Fools and Englishmen),” “Monolingualism and its Discontents,” and “Looking for Angels in Utah: An East Coast Jewish Poet in the West.” Good conversation abounds.

R E A C H I N G O U T T O T H E C O M M U N I T Y

COMMUNITY SCHOLARSHIPS FOR DIVERSITYThe College has recently created an important scholarship fund to support students who are the first in their families to get a college education. There is little financial support to help these students come to the university. We hope to change this – through an annual Community Scholarships for Diversity campaign.

For first-generation students, a scholarship represents economic opportunity for a better life – for themselves, their families, and the entire community. The Community Scholarships for Diversity, designed to provide full-ride scholarship support for qualified students, is supported entirely by community gifts – individuals contributing as little as $25, and corporations contributing up to $10,000. Regardless of the amount, one hundred percent of each gift goes toward scholarship support. The Roger Leland Goudie Foundation generously matched these gifts in 2003.

In its inaugural year, the Community Scholarships for Diversity provided scholarship funds for four highly qualified students – students who otherwise might not be able to realize their dreams for a university education.

SPONSORSHIP OF A LATINO/A YOUTH SOCCER LEAGUEIn August 2003, the College of Humanities signed an agreement to become a “presenting sponsor” of an 80-team Latino/a youth soccer league in Salt Lake County. The league’s official name is “La Liga de Futbol Soccer Mexico Utah.” Players in the Liga, which include 1600 girls and boys, range in age from six to 19 years old, and many are children of undocumented workers. At least 4000 Latino parents and other family members are at the soccer fields each weekend cheering their favorite players.The players wear uniforms imprinted with “Colegio de Humanidades”, and information about higher education is distributed during the games.

Community response has been enthusiastic, especially among the fastest-growing population in Salt Lake County, the Latino community, for whom soccer is like a second religion. Many see this sponsorship as an innovative and meaningful way to engage a Latino population where 36 percent of students drop out of high school and where, if they graduate, only six percent go to college and get a bachelor’s degree. The College’s sponsorship is heralded as a model community outreach program at townhall meetings held throughout the county. It has been featured in Latino media and has spread by word of mouth across the entire valley.

24 25

Even as a young man serving an LDS mission to London in the early 1930s, University of Utah alumnus Gordon B. Hinckley believed in the power of the humanities to enhance life: “From the reading of good books there comes a richness in life that can be obtained in no other way… To become acquainted with real nobility as it walks the pages of history and science and literature is to strengthen character and develop life in its finer meanings.” His parents, schoolteachers, and the University of Utah professors helped instill in President Hinckley a love of good books and learning. This love spans a lifetime. Today those who know President Hinckley see plainly how his years of study have resulted in a life that is superbly developed in its “finer meanings.” His is a well-trained and vigorous mind whose creativity, thought and expression are dedicated to the service of others.

There are many called to a spiritual ministry following a formal education in the humanities. The famous religious reformer Martin Luther (it is less well known that he was a great humanist scholar) wrote that “God could not do without” wise men and women.” The study of the human condition, of history, of philosophy and ethics, of language and expression, of beauty and love – collectively these subjects constitute the humanities. The wisdom of those who have studied “good books” and who labor in spiritual service is essential, and belongs to us all.

President Hinckley graduated from the University of Utah in 1932, and thought seriously about attending graduate school. He served a mission for his church in England, and his three years there would lead to a myriad of spiritual callings. He has responded to these opportunities with continual and devoted service from the 1930s to the twenty-first century. Through all of these years President Hinckley has never lost his commitment to good books and learning. As the 1998 Commencement Speaker at the University of Utah, President Hinckley held up his college Shakespeare text and affirmed its continuing relevance and importance to him. The young man who grew up on a farm in rural Utah found his way through “good books and learning” to “a richness of life that can be obtained in

LIFE IN ITS FINER MEANINGSThe Gordon B. Hinckley Endowment for British Studies

no other way.” The College of Humanities at the University of Utah is honored to celebrate its distinguished alumnus Gordon B. Hinckley, whose remarkable career reveals his ongoing dedication to wisdom and to helping others live abundantly.

The Gordon B. Hinckley Endowment for British Studies in the University of Utah’s College of Humanities will perpetually fund an innovative British Studies program that will serve as a national magnet and model for premier scholarship, teaching, and community engagement.

Specifically, The Gordon B. Hinckley Endowment will establish a rigorous and interdisciplinary curriculum in British Studies, provide scholarships and study abroad opportunities to the most deserving students, attract the best faculty, and support first-rate academic conferences and public lectures. The centerpiece of this endowment will be an internationally recognized chaired professorship named in honor of President Hinckley.

The College of Humanities is pleased to announce that The Gordon B. Hinckley Endowment for British Studies has for three years funded scholarships and study abroad opportunities in Great Britain. And thanks to the generous contributions of the Endowment’s recent donors, we are honored to announce that the funding has been secured to endow The Gordon B. Hinckley Chair in British Studies. The College is currently conducting an international search for a scholar with impeccable credentials to make this the most significant and celebrated chair at the University of Utah. The Hinckley Chair will be of such stature as to attract additional faculty members of high quality and brilliant undergraduate and graduate students.

“From the reading of good books there comes a richness in life that can be obtained in no other way…”

26 27

WEST SIDE STORIESA GROUP OF U OF U STUDENTS DISCOVERS

THE POWER OF STORYTELLING

By Ann Jardine Bardsley

Excerpts of an article published in Continuum Magazine, September 2004 Reprinted with permission

They’re small, simple, and unadorned. But the oral histories Meg Brady’s students recorded, transcribed, and published last year have a sacred quality to them.

Collectively called “West Side Stories,” each blue-gray book chronicles the first-person narratives of a resident at the Multi-Ethnic Senior Citizens High Rise (MESCH), a government-subsidized apartment building for low-income seniors in downtown Salt Lake City. And each represents a connection between senior and student.

The 20 students in Brady’s service-learning course, “Folklore Genres: The Life Story,” learned about the importance of establishing rapport with their storytellers—then did so by playing cards with and distributing groceries to the seniors. They learned about story devices, recording equipment, and about what kinds of questions to ask—and not ask. They learned patience as each hour of taped interview extended into seven hours of transcription. They learned that by sharing intimate details of their lives, the seniors gave them—and future generations—the gift of legacy. As listeners, they were changed forever.

As one student, Eliza Van Orman, wrote about the experience: “Being forced to ask questions and, more importantly, to listen, caused me to reflect more carefully on the magnificently complex breadth of human experience, while simultaneously appreciating that the basic elements of human concern cut across the demarcations of age, sex, and culture.”

That “complex breadth” is exemplified by the distillation of stories in “The Lady from Latuda—A Life Story of Alice Kasai,” as told to student Lisa Brault. The history recounts how Kasai’s parents married outside their social class in Japan, then came to America; about life in the mines in Carbon County, Utah; climbing the hills to get out of Helper, Utah, to marry her husband against her parents’ wishes; the repeal of Utah’s former anti-interracial marriage law; and Kasai’s work in the Japanese Citizenship League. Especially poignant are the stories about her husband’s internment during World War II.

29

My husband was picked up that night of Pearl Harbor. He was in Idaho having dinner with his friends. The FBI had the sheriff up there…put him in jail…First, they sent him to Missoula, Montana. They sent him to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and then they sent him to Camp Livingston, Louisiana; Bismark, North Dakota; and Fort Sill, Oklahoma. I was getting ready to join him at Crystal City, Texas, from where I was living on 2nd Avenue. I was getting someone to take care of my home during my absence. And all of a sudden they brought him home, without any forewarning or anything after two years. We had letter exchanges, but they were all censored, just like prisoners’ letters. I don’t understand why they did that…

At the beginning of the course, some students revealed that despite their love for their grandparents, they were uncomfortable and scared around older people. “One of my goals was to bridge the intergenerational gaps. And that happened,” says Brady, an English and ethnic studies professor. “The students learned about people who were very different from themselves.”

One student, Kendra Thompson, took Myrtle Muir, a now-blind, 94-year-old woman, to Liberty Park because she loved walking there when she was younger. Another student, Peter Bennion, worked at the Indian Walk-In

Center with Charlie Piper, an Arapaho Indian. The two became such good friends that Bennion began inviting Piper to his home for dinner. Chinese residents at MESCH, who had been reluctant to come to group activities because they didn’t speak English, participated in card night because two of Brady’s students spoke their language. Another student, who spoke Portuguese, cooked with five Brazilian women. “Real relationships were formed,” Brady says.

When the class ended, half of the students, from a mix of majors, wanted to analyze the common themes and values that emerged from the stories they had collected. So Brady added a class in the spring semester and the group continued to meet—and eat pizza and Chinese food—on Wednesday evenings at her home. “That changed me,” says Brady, who has taught at the University for 25 years. “I realized that preserving life stories was the most exciting work I could think of doing for the rest of my career.”

The author of Some Kind of Power: Navajo Children’s Skinwalker Narratives (University of Utah Press, 1984), Brady understands the potential of stories told from the heart and soul. “Sometimes when you ask questions, the people never stop talking. It’s like they’ve been waiting to tell their story all this time, and being asked releases the

Professor Meg Brady

floodgate,” she says, her slight drawl reflective of her Texas roots. “Oral history life stories differ from biographies in that the stories reveal how people construct their lives. It doesn’t matter if the incidents they recount are true. What’s important is they show how each person wants to be remembered.”

Another compilation, “Heart, Mind, and Soul: Reflections of a Hardcore Drifter,” is the story of Don Desimone, as recorded and transcribed by student Jef Jones. Born in Boston, Desimone was abandoned by his mother, became a ward of the state, and ran away—for the first time—at age 11. Desimone tells of being a “fatalist” all his life, riding rails, staying in “jungles” (hobo camps), and being named 1992-93 Hobo King at the National Hobo Convention in Brit, Iowa. He describes his “skills of survival”—digging through dumpsters, jumping onto trains, and always carrying a bedroll—as well as the mother who abandoned him.

Brady has several new venues for gathering life stories. Her YourStory project, patterned after StoryCorps’ recording studio in New York City’s Grand Central Station, offers a way for Utah families to humanize pedigree charts by preserving the actual voices of older generations. YourStory will be located in a recording room in the new Museum of Utah Art & History (MUAH), a Smithsonian affiliate, in Salt Lake City. For $10, participants can conduct hour-long recording sessions, guided by a trained facilitator, and then take away a professional-quality CD. With the participant’s permission, a copy of the story will be added to the archive at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress and Special Collections at the U’s Marriott Library. Brady is also applying for a grant to support a Storymobile, equipped with a recording studio, that will travel throughout the state to involve high school students, their parents, and grandparents in a multi-generational sharing of important family stories.

A member of a support group for families and friends of terminally ill patients at the Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI), Brady also plans to begin life stories work there and with those in hospice care. For individuals who are dying or very old, recording life stories can take on great urgency. Last December Brady received an e-mail from Amanda Lancaster, one of her “Life Story” students. Lancaster’s MESCH interviewee had died three days earlier. “I am taking the books to his son this week, and I know that it will be so special to them,” Lancaster wrote, adding that the project had changed her focus in life. “I am excited to go interview my grandmother and work on her life story now.”

—Ann Jardine Bardsley, an alumna of the University of Utah College of Humanities (BA English 1984), is a public relations writer in the University’s Marketing & Communications Office.

30 31

THE NATURAL WORLDA Program to Create an Ethic of Place

By Malcolm G. Scully

Reprinted with permission of Chronicle Review, Chronicle of Higher Education, August 2004

When Terry Tempest Williams was an undergraduate at the University of Utah, she wanted “a curriculum that honored both literature and the landscape.” She longed for courses in literary biology or environmental English, but when she proposed them to professors in either the English or the biology department, she recalls, “They laughed me out the door.”

Now, some 30 years later, Williams, an acclaimed writer, naturalist, and environmental campaigner, has returned to the university with the goal of putting into place what she desired then. She is the university’s first Annie Clark Tanner Fellow in Environmental Studies and one of the chief proponents of an incipient program in “environmental humanities” in the university’s College of Humanities.

The master’s-degree program — assuming it receives the expected approvals as the proposal moves through the bureaucracy — would enroll its first 15 students in the fall of 2005. Utah officials say it would be among the first graduate-level programs in the United States to bring the perspectives of such disciplines as communications, English, history, linguistics, and philosophy to bear on the kinds of environmental issues that have divided communities across the country — and nowhere more than in Utah.

The state has been the scene of environmental battles for years, and Williams has been engaged in many of them. In one essay, “The Clan of the One-Breasted Women,” she writes of the “downwinders” — people who lived downwind of the Nevada site where atmospheric nuclear tests were conducted in the 1950s and early ‘60s. “During those years when we were testing atomic bombs above ground, when we watched them for entertainment from the roofs of our high schools,” she told an interviewer recently, “little did we know what was raining down on us, little did we know what would appear years later. ... With so many of

Pending final approval by the Regents, the College will be offering a new graduate program in Environmental Humanities, starting in Fall 2005. By definition, an Environmental Humanities perspective seeks to understand a biotic or ecological community as encompassing both humans and the natural world. Further, the study of language, discourse, rhetoric, and literary, philosophical, and historical traditions is crucial for understanding and furthering environmental ethics and values in our contemporary world. In this innovative and important program, students will learn to master the rhetorical, ethical, historical and cultural issues that are at the core of environmental studies.

the women in my family being diagnosed with breast cancer, mastectomies led to one-breasted women. I believe it is the result of nuclear fallout.”

Whether it be establishing the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, restricting cattle grazing on public lands, mediating disputes over water rights, or cleaning up uranium tailings in the Colorado River, environmental challenges are inescapable in Utah. They are not issues that affect someone somewhere else; they roil communities and conversations every day.

Given that, says Robert D. Newman, dean of the university’s College of Humanities, “what better place than Utah to position such a program. It is a practical laboratory” for the environmental humanities.

The program, its “vision” statement says, is intended to “have long-term influence on how we think about our relationship and our responsibility to life on our planet.” The statement adds, “We believe that the preservation of biodiversity and the thoughtful consideration of long-term conservation require fundamental shifts in cultural practices best introduced through a humanities-based education in these issues.”

Author, environmental campaigner, and Annie Clark Tanner Fellow in Environmental Humanities Terry Tempest Williams.

phot

o: C

hery

l Him

mels

tein

32 33

It is unusual to hear a new master’s-degree program described in terms of its potential for creating a sense of “community” and for “healing” political and cultural wounds, but those terms come up frequently when proponents of this environmental-humanities program discuss their ambitions for it. Williams says that the approach of the environmental humanities can create “an ethic of place” in Utah, which can lead to “a cultural healing in a state that has been so divided on environmental issues.”

“What we are desperate for, as human beings,” she told the authors of a recent study of the views of environmental writers, “is a world where there is no separation. It means an integration of the arts with the sciences, so that we’re moving in all these worlds simultaneously.”

Dean Newman hopes that the program will help the state step back from the polarization that has surrounded many environmental issues. “How has the rhetoric surrounding these issues become so twisted?” he asks. “Part of the mission,” he adds, “is to expand the conversation beyond sound bites, to add depth and breadth to the conversation.”

In that way, he says, the quality of environmental decision making could be enhanced. Examining the historical, social, and cultural contexts of environmental problems, rather than treating them in a piecemeal way, should enable people to make better, and more widely accepted, decisions about how to mitigate environmental damage and live in sustainable communities.

Williams hopes that such contexts can bring people who see the world from fundamentally different perspectives together in discussions of what matters most to them about their communities. “You need a level of sustainability and civility to survive” in a community, she says. Despite the differences, “you become neighbors. You discover what you can agree on. Alternatives arise.”

She acknowledges, however, that achieving an ethic of place has led her to take the long view, to embrace what she calls “revolutionary patience.” You have to be passionate, she says, but patient as well.

Those are lofty goals for an incipient program, and some of the proponents acknowledge that their rationale is based on some as yet unproven assumptions that can be embodied in two sets of questions:

First, does the concept make sense philosophically? Can the humanities and the environment be integrated in a discipline with a set of principles that amounts to an intellectually coherent approach to reality, or is it simply a collection of environmentally focused courses from a variety of disciplines? Proponents hope it will be both, or that, while it may start as the latter, it will become something more — something that not only prepares students to work at the intersection of social, political, economic, and environmental concerns, but also creates a new sense of place, a new concept of how humans belong in place, a sense of stewardship rather than exploitation.

Second, can the program attain enough institutional purchase to continue beyond the enthusiasm of the founder generation, and what are the administrative elements necessary to ensure that survival? Some proponents caution that, since the faculty members will be based in their own departments rather than in a new department of environmental humanities, it may be difficult to generate the collegiality and interaction necessary to give the program professional and intellectual coherence.

But those are questions that any new interdisciplinary program confronts. For the present, the concept is being fueled by enthusiasm for an approach that, if it lives up to expectations, will unite ecosystem science with humanistic perspectives. The proponents seem confident that a critical mass of students will enroll and that those students will demonstrate the value of those perspectives in overcoming the divisiveness that has marked environmental decision making in Utah and elsewhere.

If they do so, they will have demonstrated that an interdisciplinary approach that transcends departmental boundaries and the separate cultures of science and the humanities can take hold within the intellectually cautious world of higher education.

John C. Polyani, a Nobel laureate in chemistry who teaches at the University of Toronto, said in a 1998 speech, “In science, the crucial balance is between seeing things whole and seeing them in part. Nature deals in forests, scientists seldom even in trees. For we decompose what we see, to the level of atoms and molecules. By putting on blinkers and seeing only a part of a complex phenomenon we reveal connections previously hidden from view.

“These linkages are the stuff of science. But in the process of delving for hidden patterns the larger pattern called a forest can be lost to view. Then the strength of science, which lies in its sharp but narrow focus, becomes its weakness.”

The tricky task the proponents of the environmental-humanities program have set for themselves is to strike a balance, not only between seeing things whole and seeing the particulars, but also between conflicted citizens and between conflicting demands. While no single program can accomplish the reconciliation — of people with one another and of people with their surroundings — that Williams envisions, it could be a start.

—Malcolm G. Scully is The Chronicle’s editor at large.

http://chronicle.comSection: The Chronicle ReviewVolume 50, Issue 49, Page B15Front page | Career Network | Search | Site map | HelpCopyright © 2004 by The Chronicle of Higher Education

34 35

Subhankar Banerjee’s photographic tour of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was visually stunning. Banerjee asked, how can this landscape – which many refer to as “America’s Serengeti” and which indigenous peoples name “the sacred place where life begins” – be called by others a “flat, white nothingness?” Banerjee’s art showed that the Arctic surges with cultural and environmental diversity. The area comprises but five percent of the Alaskan Arctic coast, the rest of which is open for oil and gas development. This five percent would yield a six-month national energy supply. Will issues of conservation and human rights be traded for this finite supply?

David Sibley spoke of the millions upon millions of birds who nest in the Arctic where, during the brief summer months, there is an abundance of life...and then how they migrate south, many to wilderness areas in Utah, traveling in waves, rolling and mixing, dispersing and coming back together again. The rhythm of their migration is a rhythm that connects us to our ancestors, our childhood, and to the rest of the world. “In too many places on this earth, we’ve drowned out the music and isolated ourselves from the rhythm. Seeing and hearing the music of nature reminds us that we don’t control nature; we live in constant interaction with it.”

Terry Tempest Williams concluded the evening by affirming that public lands possess spiritual values that cannot be measured in economic terms. The Red Rock desert of southern Utah teaches us what time and space create – silence, stillness, and patience. “We can learn something from Red Rock country and from the Arctic,” William said, “we can learn humility in the face of creation...and faith in one another for exercising restraint in the name of what lands should be developed and what lands should be preserved.”

“From the Arctic to the Red Rock” will long be remembered as the intellectual equivalent of Cirque du Soleil. Even as Cirque inspires audiences with the lyrical potentialities of the human form, this event, co-hosted by the College and The Nature Conservancy, inspired attendees with the reverent beauty of the Arctic and the Red Rock wilderness areas, and with the rhythmic pulse of bird migrations connecting each landscape.

During the evening, inspiration flowed from Arctic photographer Subhankar Banerjee, Audubon illustrator David Allen Sibley, author Terry Tempest Williams, poet Nicole Walker, and from environmentally-inspired music performed by members of the Utah Symphony.

FROM THE ARCTIC TO THE REDROCK

A Celebration of Environmental Humanities

NOVEMBER 4, 2004

36

photo: Subhankar Banerjee

I See Almost

I see almostA complete horizonOf plumes of rainAnd the sound they makeAlso visibleMarks the hour downDeeply for meAn instance of earthWhen earth is heavenly

I think there must be a place all summerIn the air and onThe whole horizonWhere it’s Heaven all the time -Donald Revel, Professor of English

From Traumerei

now the hardest chord is struck, two notes morethan the octave, a reach most have toroll or flubto protect the joints’ knit,dazzle the initiate’s ear, float away

even the record’s very spittingas she places the thorn-shaped needle backat the measure she wants me to hear—listen—smoothing down the square of sunlightI want to seepleated again on her gray dress—

-Paisley Rekdal, Assistant Professor of English

From Good Eye

So: happiness. I think all the timeOf luck. Once, I raised my eyes to seeA flock of southbound geese inscribe theMoon:V for virtue, voracious, velocity’s Swift kick to the ribs, for the flightOf beating ghosts, for geese wheelingTo their private star, some small lightOnly they can read by. How do they feelIt?A signal on the brain, in the heartCall it lodestar, magnet, pulling them

Across the helpless heavens. I’ve noSuch art.

-Katherine Coles, Associate Professor of English

P O E T R Yi s l a n g u a g e a t i t s m o s t d i s t i l l e d and most powerful.

-Rita Dove

38 39

Other Notes

Nobody would notice the graveyarddark of the path, the rough of it, the graveland dirt length of it, the silent stretch of it.Her bright eyes turned these things over

as she passed, impelled by some secret

to continue. Her footfalls disappeared noiselessly into the dim timeless dream. Who wouldn’t notice the loud paradepreceding her? One man, the noise

of his song echoed over the sound

of her measured steps. He wasn’t listeningto discern if she followed—though his face was screwed up in an incredible grimace. He was listening to his lyre,how the world sang back to him. As if sadness

were something he could name, own, slipinto his pocket. This was his idea of love. He thought to save her, prove his gift. Nobody would notice her white hands tucked into the dark warm folds of her dress, the slow pace of her, the sweet grey shade

of her. She couldn’t hear grief playing in his song. The display didn’t registeror draw her along like love. Other noteslulled her, darker: a dirge, the feel

of her own voice in her throat, pomegranates

split wide and set on a stone table. No one but she could have made this songand none would take notice of her secret tune which led him up the steep path, which sent

him like an arrow shot from night

toward morning. Not even he knew she was singing, though he obeyed. Whenhe stood a jubilant, anxious silhouette against the garish gates, she stopped her song

abruptly. She may as well have called to him.

- Max Freeman, HBA English ‘03Originally published in Nimrod International Journal, “Vietnam Revisited” issue, www.utulasa.edu/nimrod

Each year, twelve undergraduate students from the College of Humanities are selected to live in the O.C. Tanner Humanities House in historic Fort Douglas. Selection is highly coveted by Humanities students for financial housing support, but more importantly for the enhanced academic experience represented by residency in this unique environment.

“The experience offered me more in the way of intellectual and personal growth than I could ever have thought possible or necessary,” said a recent resident. “My eyes were opened to other aspects of humanities studies by talking to majors of philosophy and English about religion, ethics, literature, and poetry. I had the opportunity to participate in house-based lectures, events, films, poetry readings and dinners with professors.”

This year’s student residents come from a wide variety of interests and life experience. They are 12 bright, energetic and dedicated students from across the College. Collectively, they speak and are studying six different languages and are involved in many activities across campus. They have received the most prestigious scholarships in the college and across campus, including the Utah Opportunities Scholarship, Larry H. Miller Scholarship, and the Steffenson-Cannon Scholarship, as well as many departmental scholarships.

When students talk of their experience as residents of the Humanities House, they refer to ‘expanding horizons,’ ‘being part of a community’, or being ‘immersed’ in an environment of academic rigor. “My housemates,” noted one resident, “are my girlfriends, my confidants, my heroes and my teachers.”

Students selected to live in the Humanities House for the 2004-2005 academic year include: Nick Rothacher, SpanishBrittani Bennally, EnglishChristina Day, EnglishShannon Garner, EnglishSarah Jackson, Mass CommJeremiahKendall, LinguisticsSheena McFarland, Mass CommJaymes Myers, Speech CommRobert Powell, French & SpanishJustin Stanley, EnglishKellie Stirling, MES, Speech CommChi Chi Zhang, Mass Comm

O . C . T A N N E R H U M A N I T I E S H O U S E

—

40 41

HONOREES AT THIS YEAR’S CONVOCATION INCLUDED:

Laura Weiss, 2004 Exemplary Undergraduate and Convocation SpeakerKanita Lipjankic, Young Alumni Association’s Outstanding Senior Award

Jacqueline Osherow, University Distinguished Professor AwardLorna Matheson, Distinguished Honorary Alumna

Ann Hart, Ph.D., Distinguished Alumna