Kaushik 2015

-

Upload

fauzi-djibran -

Category

Documents

-

view

242 -

download

0

Transcript of Kaushik 2015

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 1/29

International Journal of Bank MarketingInnovation adoption across self-service banking technologies in India

Arun Kumar Kaushik Zillur Rahman

Article information:

To cite this document:Arun Kumar Kaushik Zillur Rahman , (2015),"Innovation adoption across self-service bankingtechnologies in India", International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 33 Iss 2 pp. 96 - 121Permanent link to this document:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-01-2014-0006

Downloaded on: 31 January 2016, At: 14:28 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 113 other documents.

To copy this document: [email protected] fulltext of this document has been downloaded 755 times since 2015*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

Florian Moser, (2015),"Mobile Banking: A fashionable concept or an institutionalized channel infuture retail banking? Analyzing patterns in the practical and academic mobile banking literature",International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 33 Iss 2 pp. 162-177 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2013-0082

Ali Saleh Al-Ajam, Khalil Md Nor, (2015),"Challenges of adoption of internet banking service inYemen", International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 33 Iss 2 pp. 178-194 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-01-2013-0001

Vishal Mishra, Sridhar Vaithianathan, (2015),"Customer personality and relationship satisfaction:Empirical evidence from Indian banking sector", International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 33 Iss 2pp. 122-142 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-02-2014-0030

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emerald-

srm:277061 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emeraldfor Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submissionguidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The companymanages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, aswell as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources andservices.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of theCommittee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 2/29

*Related content and download information correct at time of

download.

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 3/29

Innovation adoption across

self-service banking technologiesin IndiaArun Kumar Kaushik and Zillur Rahman

Department of Management Studies, Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee, India

Abstract

Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to analyze the various antecedent beliefs predicting customers’attitudes toward, and adoption of, self-service technologies (SSTs) available in the banking industry.Design/methodology/approach – A descriptive research design with survey approach is used todevelop and test a conceptual model of adoption for all three self-service banking technologies (SSBTs).Findings – The results of the comparative analysis showed that antecedent beliefs affecting adopters ’

attitude vary across different SSBTs. It extends and tests the technology acceptance model (TAM) byincluding two additional antecedents from the theories of adoption behavior.Research limitations/implications – All three SSBTs included in the paper are from the bankingindustry, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other industries. Many other limitationswere also reported.Practical implications – The findings reveal why and how customers decide to adopt differentSSBTs and why a few SSBTs are more widely accepted than others. The practicality of the findingsguides managers and designers of technological interfaces.Social implications – People will also benefit from the effective implementation of SSTs.Originality/value – This study stands out as one of the early studies to empirically examinethe antecedents-attitude-intention relationship across different SSBTs available in Indian bankingindustry.

Keywords Marketing, Service, Consumer behavior, Banking, Banking industry, Self-service

Paper type Research paper

1. IntroductionIn the changing scenario from product-centric to customer-centric approaches, thefocus of marketers has shifted toward their customers and more deliberately on theirexperiences (Garg et al., 2010; Yousafzai, 2012). Many innovative financial solutionsfor insurance, credit products, and transaction processing services have grownconsiderably in the past few decades (Nejad and Estelami, 2012). The impact has beenmainly profound in the services arena through the development of self-service

technologies (SSTs). In recent time the four basic types of self-service bankingtechnologies (SSBTs) available which significantly affect the traditional bankingservices delivery. First the automatic teller machines (ATMs), which were started in thelate 1970s; electronic fund transfer at the point of sale, introduced in the early 1980s;telephone banking in the mid-1990s; and internet banking (IB), which emerged in thelate 1990s (Meuter et al., 2000; Curran et al., 2003; Mcphail and Fogarty, 2004; Curranand Meuter, 2005). As the twenty-first century develops, all these SSBTs play their keyroles in the banking services delivery process.

Information technology (IT) and the internet have emerged as a dynamic mediumfor channeling transactions between customers and firms in virtual marketplaces

International Journal of Bank

Marketing

Vol. 33 No. 2, 2015

pp. 96-121© EmeraldGroupPublishing Limited

0265-2323

DOI 10.1108/IJBM-01-2014-0006

Received 14 January 2014Revised 5 May 201415 May 2014Accepted 18 June 2014

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at:

www.emeraldinsight.com/ 0265-2323.htm

The authors would like to thank the Indian banks for their support in collecting data.

96

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 4/29

(Eriksson et al., 2008; Sayar and Wolfe, 2007; Rahman, 2003). Due to this, bankcustomers access their bank accounts, transfer funds, review transaction details,pay their bills online, and conduct transactions electronically virtually anytime and

anywhere. Additionally, there are several other advantages of this, such as cost savingsfor banks and convenience for customers by 24/7 access to their account (Xue et al.,2011; Yoon and Steege, 2013). In many cases however, both service employees andcustomers were averse to adopting new technology (Griffy-Brown et al ., 2008).

With this technological growth, researchers have begun to explore the role of consumer expectations and innovativeness regarding the adoption of SSTs (Kaushikand Rahman, 2014). A few early studies described the key factors leading to customersatisfaction/dissatisfaction while using SSTs (Dabholkar, 1996; Meuter et al., 2000).Some studies explored the customers’ capacity and willingness as predictors of adoption (Walker et al., 2002; Mazzarol and Reboud, 2005) and others investigatedthe attitudes of customers regarding adoption intention (Dabholkar, 2000; Plouffeet al., 2001; Curran et al., 2003). There is an overabundance of academic literature thatexamines the key factors that influence customers ’ evaluation of newly introducedSSTs (Dabholkar and Bagozzi, 2002; Meuter et al., 2005).

The basic technology acceptance model (TAM) is an extended work of theory of reasoned action (TRA) proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975). TAM was primarilydeveloped by Fred Davis and Richard Bagozzi (Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989) to replaceseveral TRA attitude construct measures with two new constructs, i.e. perceivedease of use (PEOU) and perceived usefulness (PU). The TRA and TAM work on theassumption that if an individual makes an intention to act, then he/she will be freeto act without limitations (Davis et al., 1989). Past studies using the TAM in the contextof innovation adoption have mainly emphasized: model replication for empirical evidenceon the relationships between PU, PEOU and technology use/adoption (Adams et al., 1992;

McKechnie et al., 2006); theoretical support for PU and PEOU (Adams et al., 1992;Eriksson and Nilsson, 2007; Celik, 2008); and an extension of TAM suggested by Legriset al. (2003), which includes a few additional constructs as direct determinants of attitude,intentions or use, and model modification by combining TAM with other models(Chan and Lu, 2004). A comparison of TAM, TRA and the theory of planned behavior,Yousafzai et al. (2010) showed that TAM was empirically superior to the others.

Following this, the present study extends the TAM by including two additionalantecedents (i.e. need of interaction and perceived risk (PR)) that have not been deeplyexplored in extended TAM studies. It mainly aims at comparing the adoption behaviorof customers across SSBTs used in India. The study makes a major contribution bydeveloping an extended model that increases the explanatory power of attitude toward

the adoption of SSBTs and contributes to various adoption behavior theories. Next,a comparison across technologies presents how the antecedents vary from onetechnology to another. This information is important for designers who make technologicalinterfaces and for marketing managers who must develop suitable marketing andpromotional strategies for the wider adoption of a particular technological interface.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: a literature review related to theevolution of service delivery and the different kinds of SSBTs (Section 2), thedevelopment of a conceptual model and derived hypotheses (Section 3), researchmethodologies (Section 4), the findings and a discussion based on different analysesusing structural equation modeling (SEM) with empirical data from customers of Indian banking industry (Section 5), the conclusion and implications (Section 6) and

finally the limitations and further research directions (Section 7).

97

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 5/29

2. Prior research and theoretical background 2.1 Evolution of service deliveryOver the last few decades, the delivery of certain services has changed from human

interaction to technology that can provide 24/7 self-service opportunities (Meuter et al.,2000). This evolution of service delivery is different from the replacement of humanlabor with automatic machines in the agricultural and manufacturing industries(Ong, 2010). Past studies on the adoption of technology in different services such as thehospitality sector confirm that a growing number of consumers are prefer DIY (Do-It-Yourself) opportunities and in some cases are eager to use SSTs in food service andlodging establishments. SSTs began as service delivery systems to increase revenue forservice providers instead of adding value to their service quality. For example, an ATM serves as a 24/7 cashier, which saves labor costs and gives bank customers accessto services at their own convenience (Xue et al., 2011; Fitzsimmons, 2003).

2.2 SST In the last few decades, IT applications have changed the landscape of the serviceindustry. The term “SST” was first used by Meuter et al. (2000) and defined as“technological interfaces enabling customers to use a service independent of directservice-employee involvement.” Today, technology-oriented interactions have thepotential to determine the long-term success of a business (Meuter et al., 2005) andthe role of SSTs in customer interactions has increased significantly. In subsequentstudies, the term SST and its definition has gained wide acceptance among otherresearchers (Curran and Meuter, 2005; Lee and Allaway, 2002; Forbes, 2008). Althoughnumerous studies have explored the successful adoption of new technology, thepopularity of self-service kiosks (SSKs) for check-in at airports, and in different service

arena (e.g. hospitality services) has finally made SSTs a familiar technology (Mayock,2010; Ostrowski, 2010).Nearly all service industries have encountered new technological innovations that

have transformed traditional service delivery into modern practices. Hotel customers,who once faced incompetent service experiences like long queues, operational delays,etc., prefer to the use of SSTs (Kasavana, 2008). With a high acceptance rate of newSSTs at the workplace, more and more banks are now implementing different SSTsto enhance their service quality standards, operational efficiencies, and mostimportantly overall customer satisfaction. The continuous advancement fromtraditional service delivery to modern SSTs is important for all the service industries(Cunningham et al., 2009).

2.3 Types of SST There are different types of SSTs available in different sectors in the marketplace, butthe majority of studies on SSTs primarily emphasized on the customer satisfactionthat derived from adopting and using SSTs (Meuter et al., 2000). Many of these studiesfocussed on new and single SSTs in a specific context, adopter’s attitude and intention(Curran et al., 2003; Dabholkar, 2000; Plouffe et al., 2001) and the technological readinessof SSTs (Parasuraman, 2000; Liljander et al., 2006; Lin and Hsieh, 2006). In a crucialstudy, Meuter et al. (2000) conceptualized the various SST options and presenteddifferent technology interfaces (i.e. telephone-based technologies and interactive voiceresponse systems, internet-based interfaces, interactive kiosks, and video technologies)

along with their end use such as customer service, transactions, and customer self-help.

98

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 6/29

Different SSTs allow service providers to design and develop more advanced anduser-friendly machines with multiple functions. Technological advancements providefirms with the flexibility to select an appropriate type of technology interface that suits

their purpose. A few basic types of SSTs that are commonly accepted in differentsectors are discussed below: 2.3.1 SSKs. SSKs are the most widely accepted SST that offers numerous services

to consumers in new and optimum ways (Wentzel et al., 2013). While SSKs have beenaround for quite some time, more and more financial institutions are adopting them.Initially, they resemble an ATM, but they are capable of performing numerousadditional services. These additional services go beyond the capacities of IB and handleoperations that previously required human interaction during working hours. Thesebanking kiosks offer bank customers the ability to check current funds, print passbooks,pay bills, submit cheques, deposit and withdraw cash, and many other features. In asurvey conducted by Celent Research in 2012, it was found that nearly two-thirds of

credit unions and one-third of banks surveyed already use or plan to use personal tellermachines, self-service terminals, or kiosks within the next year.Although studies on man-machine interactions have been made since Taylor ’s and

Gilbreths’ time, different aspects of operating a banking kiosk remain unknownsince it is a recently introduced channel for delivering select services in retail-banking.To introduce new information delivery systems to retail customers, banking facilities,operations, and employees must be in a position to support the banking transactions(McKenna, 1995). Additionally, bank kiosk occupancy is another matter of concern.Many times, we found long queues in front of ATMs and bankers are worried aboutsuch issues. Another key concern is how service firms should price new innovationsin order to justify their investment (Nejad and Estelami, 2012). The successful

implementation of SSKs depends mainly on the acceptance rate and the realistictimeframe for recovering the initial investment because adopters only adopt technologiesthat are beneficial to them, which generally takes time (Lui and Piccoli, 2010). There arestill not enough banking kiosks, especially for nationalized banks of developing countrieslike India.

2.3.2 Internet-based self-services. The internet offers a huge range of self-servicesopportunities for bank customers (Rahman, 2004). It enables them to interact directlywith companies to find out useful information, make queries, and deal with employeeson a range of issues. Initially, it was found that most banks pursue poor and ineffectivestrategies for moving customers toward online banking (Sarel and Marmorstein, 2003,2004). Furthermore, only a few studies have addressed the key influential variables that

strongly influence IB (Kolodinsky, 2004; Machauer and Morgner, 2001), but now thisquestion has attracted a great deal of academic interest (Alhudaithy and Kitchen, 2009;Yousafzai, 2012). Moreover, there are many customers who switch to internet-basedservices because they perceive them as easy to use, enjoyable, and convenient (Meuteret al., 2000; Yen, 2005).

2.3.3 Mobile-commerce (m-commerce). M-commerce differs from electronic-commerce(e-commerce) because it clearly allows users access to real-time information, a certainlevel of control and quick access to information (Kim et al., 2010). With of the high levelof mobile technology penetration among consumers, the mobile landscape has beenemerged as an important channel for companies to market their products and services.However, Hinson (2010) estimated that around 90 percent of the people from developing

countries do not have access to financial services. The study also argued that low income

99

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 7/29

or marginal workers must be offered mobile banking if the traditional financialsetting does not allow them to access banking services. The advancement in mobileinterfaces and the popularity of 3G mobiles has continuously increased the number

of mobile users worldwide. This increase in mobile users will positively contribute to thegrowth of m-commerce.Smart phones were forecasted to increase from 161.4 million units in 2009 to 415.9

million units by 2014. The increase in popularity for Samsung smart phones, Applei-Phones, Blackberry devices, and the introduction Goggle’s Android phones havesparked a huge demand in the smart phone market. Additionally, the numberof consumer applications (apps) has also increased exponentially, with the majority of apps available across almost all types of mobile devices. Smart phones have becomethe preferred device for voice, data, and video capabilities among consumers (Kumar,2010). Most financial organizations use mobile banking (Riivari, 2005) and IB (Raecheland Bruce, 2008) in order to improve business-customer relationships, and to reduce

overall costs. However, service providers must have better knowledge about typicalmobile banking to add value to their marketing actions (Laukkanen and Pasanen,2007). Despite the many advantages of m-commerce, the use of mobile banking is still inits infancy and IB retains its first position as the most accepted channel in e-banking(Laukkanen, 2007a, b; Laukkanen and Cruz, 2009).

3. Research model and hypotheses3.1 AttitudeEagly and Chaiken (1993) defined attitude as a psychological tendency that isexpressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor. It isnever easy to measure the attitudes of people because their attitude toward technologyin general is not stable (Blackhall et al., 1999). However, it can be measured toward a

specific technology (Daamen et al., 1990). Past literature also shows an individual’sattitude toward adoption is strongly dependent on the type of SST (Dabholkar, 2000;Plouffe et al., 2001; Curran and Meuter, 2005; Collier et al., 2014). Curran et al. (2003) alsomentioned the distinguishable attitudes of people toward different SSTs. Additionally,as customers are more and more exposed to a wide range of SSTs implementedby service firms, their past experiences influence their subsequent attitudes toward theadoption of SSTs (Wang et al., 2012). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1. Attitudes toward different SSBTs (in the case of same service delivery) willvary from one SSBT to another.

An important assumptions from innovation literature (Rogers, 2003) is highly adopted

innovation is perceived as more beneficial. In a recent study by Wang et al. (2012), itwas clearly mentioned that past positive experiences of users with one SST (e.g. onlineflight check-in) might inspire a user to use another SST (e.g. online hotel reservation)since both have similar technologies. Dimitriadis and Kyrezis (2011) also note that thetransaction type strongly influences customer’s attitude toward the adoption of distincttechnologies. Since we have included different technologies in our research, we proposethe following hypothesis for a comparative analysis:

H2. Attitudes toward highly adopted SSBT will be more positive that those poorlyadopted.

TRA (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975) clearly postulates that an individual’s consciously

intended behavior is a result of his attitude toward performing the behavior (Ajzen and

100

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 8/29

Fishbein, 1980). Furthermore, the relationship between these two constructs has beenextensively researched over the last few decades (Taylor and Todd, 1995; Dabholkar,1996; Legris et al., 2003; Celik, 2008). One of the most common findings is evidence

that supports attitude toward technology as a key antecedent to intention to adopt aparticular technology with a few salient antecedent beliefs predicting those attitudesand intentions (Adams et al., 1992; Dabholkar, 1996; Davis et al., 1989; Erikssonand Nilsson, 2007). A meta-analysis of empirical findings shows that an individual ’sintentions to use/adopt an SST are primarily determined by his or her attitude towarduse (Meuter et al., 2005). Thus, we can propose that:

H3. Attitude toward a specific SSBT will affect behavioral intention to adopt or usethat SSBT.

3.2 Antecedent beliefsIn the present study, we have included four antecedent beliefs to predict attitudestoward three different SSBTs, ATM banking, phone banking (PB), and SSKs (e.g.passbook printing, token machine, cash depositor kiosk). Although, Shih and Fang(2006) concluded that the addition of extra variables does not improve the explanatorypower of the original model, it did increase the explanatory power of attitude andbehavioral intention. These four antecedent beliefs are summarized in Table I.

Recent studies have found that a person is more likely to have a positive attitudetoward SSTs perceived as easy to use, useful, controllable, and not risky (Wang et al.,2012; Alhudaithy and Kitchen, 2009; Yousafzai et al., 2010). PEOU has a directsignificant impact on behavioral intention but only in the early stages of adoption(Venkatesh et al., 2003; Davis, 1989). When adopter experience increases, this impactbecomes indirect and operates through PU (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). Therefore, wepropose the following hypotheses in order to verify these relations in our comparative

analysis. This will help in understanding whether these relations vary across differenttechnologies:

H4. Ease of use of the SSBT will be positively related to attitudes toward a specificSSBT.

H5. PU of the SSBT will be positively related to attitudes toward specific SSBT.

Sl.no.

Antecedentbelief Definition Reference studies

1 Ease of use Degree to which a user would find the useof a particular technology to be free fromeffort on their part

Davis et al. (1989), Adams et al. (1992),Dabholkar (1994), Igbaria et al . (1995)

2 Perceivedusefulness

Perceived usefulness is the subjectiveprobability that using the technologywould improve the way through whichone could finish a given work

Jackson et al . (1997), Mathieson (1991),Taylor and Todd (1995)

3 Need forinteraction

An aspiration to keep personal contactwith others during a service encounter

Dabholkar (1992), Bateson (1985),Meuter et al. (2000)

4 Perceivedrisk

A probability of certain outcomes given abehavior, and the danger and severity of negative consequences from engaging inthose behaviors

Peter and Tarpley (1975), Murray (1991),Dabholkar (1996), Meuter and Bitner(1998), Gatignon and Robertson (1991)

Table I.Antecedent beliefs aspredictor of attitudes

101

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 9/29

Customer interactions with service employees can develop interpersonal relationshipsbetween them (Berger and Calabrese, 1975). The need for interaction betweencustomers and service providers became necessary to deliver a technical quality

service (Seth et al., 2005). According to Seth et al. (2005), technical quality is the qualityof what customers perceive as the outcome of their interaction and what is crucial tothem and their evaluation of the quality of service. However, using SSTs obviouslylacks this interaction and eliminates interpersonal relationships. Relationship buildingis a valued aspect for building a customer base, especially in the context of serviceconsumption (Dabholkar, 2000). In addition, Cunningham et al. (2009) reported thatcustomers analyze SSTs based on the employee contact infused into the transactionprocess. Using SSTs may be less effective for a few customers, while a differentcustomer base may adopt or use different SSTs rather than interacting with servicepersonnel. However, there is a lack of evidence to confirm this assumption (Hilton et al.,2013; Kallweit et al., 2014). Thus, we offer the following hypothesis:

H6. Need for interaction with service personnel will be negatively related toattitudes toward SSBTs.

PR from the theory of perceived risk (TPR) is another antecedent belief included as adirect measure of customer attitude. It has been extensively researched and foundnegatively associated with attitudes of potential adopter (Dabholkar, 1996; Meuter andBitner, 1998; Gatignon and Robertson 1991). Murray (1991) mentioned that customersseek out enough information to decrease PR while purchasing a service. However, inmany studies on technology framework the concept of risk has been discussed undervarious terms like reliability (Dabholkar, 1996), accuracy and recovery (Meuter andBitner, 1998). For customers with an online banking facility, security is the keyfacilitator variable for its use in the future, while continuous improvements in online

services can be a prohibitive variable (Katuri and Lam, 2006). A few other studies havereported that PR is a key variable for innovation adoption because individuals aremore likely to adopt technology that is easy to use, enjoyable, and convenient (Meuteret al., 2000; Yen, 2005), and if they are offered low-cost or low-risk use of technology(Black et al., 2001). There is still a need for current studies on this construct, thuswe propose:

P7. PR of adopting or using SSBTs will be negatively related to attitudes towardSSBTs.

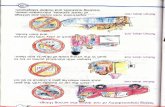

3.3 Development of model Our study extends the technological adoption model by including two additional

external variables. In our extended model, there are now four antecedent beliefsas direct predictors of an individual’s attitude toward different SSBTs. Furthermore, itis proposed that an individuals’ attitude affects his/her behavioral intention to adoptSSBT. This model will be tested with the three SSBTs included in our research.This will boost the robustness of our testing and analyze the consistency of relationsamong all the variables across all three SSBTs (Figure 1).

4. Methodology4.1 Research designIn order to analyze the factors of intended usage of SSTs in the banking industry,a descriptive research design with a survey approach has been applied to collect

empirical data from bank customers in India. The banking industry has been targeted

102

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 10/29

because of its history of introducing different and innovative technologies to deliverquality service to its customers. Therefore, it also allows us to test our adoption modelacross different technologies. Second, it is a widely distributed service industrywhere customers are highly involved in the transaction process. Services offered by thebanking industry are similar throughout India, which increases the generalizability of our research.

According to a recent report on payment systems by the Reserve Bank of India

(RBI), there has been a steady growth in the number of electronic transactions routedvia SSTs, resulting a dramatic fall in the number of paper-based transactions(e.g. transactions through cheques/demand drafts) over the years. The upward trend of electronic transactions in both numbers and values can easily found in the RBI annualreports. In 2004-2005, the total number of electronic transactions were only 228.9million with a value of Rs. 1,087.50 billion, have increased to 1159.84 million with a totalvalue of Rs. 22,075.33 billion in 2011-2012. This is more than the total value of paper-based transaction of Rs. 20,868.24 billion in 2011-2012. Thus, in recent years electronictransactions are a preferred and secure medium by which people transact a largeamount of money. This shows importance of studying consumers’ perceptionregarding the implementation of SSTs in the banking industry.

A survey instrument was designed to measure the four predictors of attitudes (ease

of use, PU, need for interaction, PR) along with attitude and intention constructs.It consists of three sections with questions related to the antecedent beliefs andsubject’s attitude toward each of the three SSBTs and intentions to adopt SSBTs.In all three sections, each respondent was asked about the same antecedents orpredictors of attitudes, but only one of the three SSBTs in each section. It was typicalfor respondents to answer all three sections, but on the other hand, it was necessary forcomparing the opinion of the same respondents for all three technologies.

4.2 Construct measurement It was difficult to find an existing summated scale, especially with PR since risk

has been discussed under various terms like reliability (Dabholkar, 1996), accuracy and

Ease of Use

Perceived

Usefulness

Need of

Interaction

PerceivedRisk

Attitudes

toward SSTs

Intention to

adopt or useSSTs

Antecedent Beliefs Attitude Construct Behavioral Intention

Figure 1.

Antecedent-attitude-intention model

103

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 11/29

recovery (Meuter and Bitner, 1998). Our instrument includes all four existing constructs,i.e. ease of use, PU, need for interaction and PR, which were measured by a seven-pointLikert Scale with endpoints of 1 (strongly agree) and 7 (strongly disagree). All the items

under the risk construct were developed and used to answer questions about theexperience of bank customers regarding SSBTs. The attitude construct was measured bya seven-point semantic differential scale with endpoints of very good/very bad, verypleasant/very unpleasant and strongly like/strongly dislike. In each section, the constructwas measured by three items across all three categories of SSBTs. The reliability of scale items as well as whole scale was determined by Cronbach’s α values, which areshown in Table II.

4.3 Data collectionPilot testing of the instrument was completed by a sample of 130 bank customers usinga convenience sampling technique before the final data collection. This study onlyselected voluntary participants. All the participants were randomly selected in frontof banks located at convenient locations in several major cities in North India.Participants were limited to individuals 18 years of age or older and permanent residesof India with their own bank account. After the initial survey, 52 respondents answeredto all questions based on antecedent beliefs of ATM banking available in the firstsection, 27 respondents answered all questions related to antecedent beliefs of PB inthe second section, 38 respondents answered questions related to the same antecedentbeliefs in the case of SSKs in the last section and the remaining 13 respondentsanswered all sections of survey instrument. A principle component factor analysis(PCA) with Varimax rotation was applied to make a clear differentiation betweenfactors across all three SSBTs.

For the final data collection, more than 2,000 people were targeted through an online

survey, while approximately 262 people were approached through an offline survey.For the online survey, the e-mails IDs of bank customers were taken from varioussources like personal contacts, account sections of colleges/universities and from a fewbanks. A blind random survey was also conducted with the help of “Google form,”which is a web-based tool that collects information from users via a personalizedsurvey or quiz. All the necessary instructions and objectives of research were clearlymentioned in the initial part of this form. The majority of responses were from majorcities like Delhi, Mumbai, Chandigarh, and Bangalore in India. After reviewing thesurvey submissions, the online survey resulted in 374 usable responses with a responserate of 18.7 percent, but 17 respondents that were found unusable for inclusion in thefinal analysis.

A total of 619 respondents were included in the final analysis with an instructionthat they can answer either one section of their own choice or all three. Out of 619respondents, 223 people answered only the first section about their antecedent beliefson ATMs, 167 people answered only the second section of PB and last 185 answeredonly the last section based on SSKs, and only 44 respondents responded to all threesections. Thus, our sample covered all three categories of SSBTs. Since we receivedonly a few responses on all three SSBTs from the same respondent, we decided againstanalyzing the perceptions of people who had experience and answered questions fromall three SSBTs. This offers an opportunity for further research with an objective of analyzing one’s perception across all SSBTs.

The majority of customers (approx 54 percent) were adult students (e.g. master’s

and doctoral students) because we can easily reach and target them. They are frequent

104

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 12/29

C r o n b a c h ’ s α

v a l u e s

A

n t e c e d e n t b e l i e f s ( i n c l u d e d i n

P

r e s e n t s t u d y )

D e s c r i p t i o n o f s c a l e i t e m s

I t e m s a d o p t e d f r

o m

P r e t e s t

S t u d y

E

a s e o f u s e

L e a r n i n g t o u s e S S T w a s e a s y

F i n d i n g S S T s d i f f i c u l t t o u s e

E a s y t o b e c o m e s k i l l f u l b y u s i n g S S T

D a v i s e t a l . ( 1 9 8 9 ) , D a b h o l k a r ( 1 9 9 4 )

0 . 9

0

0 . 8

1

P

e r c e i v e d u s e f u l n e s s

S S T i s u s e f u l f o r b a n k i n g

U s i n g t h e S S T i m p r o v e s t h e b a n k i n g

U s i n g t h e S S T m a k e s b a n k i n g e a s i e r

A d a m s e t a l . ( 1 9 9 2 ) , D a v i s e t

a l .

( 1 9 8 9 ) , I g b a r i a e t a l . ( 1 9 9 6 ) , J a c k s o n

e t a l . ( 1 9 9 7 )

0 . 9

3

0 . 8

9

N

e e d f o r i n t e r a c t i o n

E n j o y t o s e e t h e w o r k i n g p e o p l e a t b a n k

P e r s o n a l a t t e n t i o n o f b a n k e r s i s n o t i m p o r t a n t

P e o p l e d o t h i n g s f o r m e t h a t n o m

a c h i n e c o u l d

D a b h o l k a r ( 1 9 9 6 )

0 . 7

4

0 . 7

2

P

e r c e i v e d r i s k

F e l l i n g s e c u r e w h i l e u s i n g t h e S

S T f o r

b u s i n e s s i n b a n k i n g

F e e l i n g s a f e w h i l e u s i n g t h e S S T f o r b a n k i n g

K n o w i n g t h a t t h e S S T m a y h a n

d l e m y

b u s i n e s s c o r r e c t l y

A l i t t l e d a n g e r a b o u t a n y t h i n g m

a y g o w r o n g

w h e n I u s e t h e S S T

D a b h o l k a r ( 1 9 9 6 ) , M e u t e r a n d

B i t n e r ( 1 9 9 8 ) , M u r r a y ( 1 9 9 1 )

0 . 7

9

0 . 7

6

A

t t i t u d e s t o w a r d S S T s

F e e l i n g g o o d o r b a d a b o u t u s i n g t h e S S T

F e e l i n g p l e a s a n t o r u n p l e a s a n t w h i l e u s i n g

t h e S S T

Y o u r l i k i n g o r d i s l i k i n g w h i l e u s i n g t h e S S T

B a r k i a n d H a r t w

i c k ( 1 9 9 4 ) ,

D a b h o l k a r ( 1 9 9 6 ) , H a r r i s o n e t a l .

( 1 9 9 7 )

0 . 9

3

0 . 9

1

I

n t e n t i o n t o a d o p t o r u s e S S T s

I n y o u r r o u t i n e b a n k i n g h o w l i k

e l y a r e y o u t o

u s e t h e S S T ?

C u r r a n a n d M e u t e r ( 2 0 0 5 )

n a

n a

N o t e s : D u r i n g S u r v e y , t e r m s “ A T M s t e c h n o l o g y ” , “

P h o n e b a n k i n g ”

a n d “ S e l f - s e r v i c e K i o s k s ”

w e r e u s e d i n s t e

a d o f S S T s ; s o m e o f t h e i t e m s w e r e r

e v e r s e - c o d e d

a

t t h e t i m e o f f i n a l a n a l y s i s ; a t t i t u d e

t o w a r d S S T s s h o w s l o w e s t v a l u e o

f t h e t h r e e C r o n b a c h α ’ s f o r a l l t h r e e S S T s

Table II.Reliability analysis

of antecedent beliefsand their scale items

105

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 13/29

users of banking services because they have a monthly scholarship as income. Otherreasons for including students in the majority of samples are their high propensityto adopt technologies, the availability of SSTs on campus and their ability to learn new

technologies. Additionally, students have also been taken as a sample in past adoptionstudies in various contexts such as developers and deliverers of e-learning that need tobetter understand how students perceive and react to various elements of e-learning(Park, 2009). Selim (2003) also stated that there was a need to investigate TAM withweb-based learning and university students. Lee et al. (2005) did a similar study onuniversity students’ adoption behavior toward an internet-based learning medium.In our research, all the students were asked to complete at least one section of thesurvey instrument. However, we targeted both students and people from otheroccupations such as the service, business, and agriculture sectors.

5. Core findings and discussion

5.1 Analysis of construct ’ s reliability

Although the scales used to measure the antecedent beliefs and other behavioralconstructs were adopted from past literature and were pre-tested, they need to bereviewed for reliability under the conditions of the current study. All the predictorsof attitude toward SSBTs were found reliable with sufficient values of Cronbach’s α asshown in Table II.

In Table II, all the constructs and their corresponding items show high internalconsistency since Cronbach’s α for all constructs are higher than the minimumsatisfactory value of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978). Cronbach’s α for each attitude scale acrossall three SSBTs were 0.96 for ATMs, 0.91 for PB, and 0.93 for SSKs indicating a higheroverall internal consistency for all the scales.

5.2 Descriptive analysisThis section provides an analysis of primary responses collected from the field andonline survey. The respondents were 62 percent male and 38 percent female. The agegroup ranged from 18 to 72 years old, with an average age of 38, which evidenced amajority of young people in our research. Income and education levels were foundnormally distributed across all three categories of SSBTs.

In addition, several other crucial issues were explored, such as how often they wentto their bank, usage rate of SSBTs, and their awareness of different SSBTs. More than78 percent of the respondents have used ATMs, whereas only 13 percent have used PBand 47 percent respondents had familiarity with SSKs. The SSKs are relatively new

technologies offered by banks to deliver services like passbook printing, tokenmachine, and cash deposits, etc. However, its usage rate is higher than PB but lowerthan ATM banking. The majority of respondents (93 percent) mentioned they knewabout their bank’s ATM, but only 43 percent people indicated they use PB and 73percent people responded positively about the availability of SSKs as an alternative tousing a bank’s live customer services. All these results are given in Table III.

Based on the facts given in Table III, we may conclude that ATMs are more widelyaccepted SSBTs than the other two categories. A reason for this might be becauseATMs were introduced much earlier than the other two SSBTs, but still there might beother reasons like making a single cash deposit (e.g. salary deposited once in onemonth) but several withdrawals over the course of a month. People prefer to have cash

available and make withdrawals according to their requirements. For this, they use

106

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 14/29

ATMs more than a cash deposit kiosk. Despite the wide availability of PB for manyyears, it has not achieved widespread adoption even though India is a country withsecond largest number of phone users (approx 867.8 million phones in use up to 30

April, 2013) after China. The low usage rate of SSKs is somewhat understandablebecause it is a new technology offered by a few banks at select branches. ATMs aredirectly affected by the other two SSBTs. For example, using ATMs decreases the needto visit a bank where SSBTs are available. For instance, a person requires a quicktransaction statement; he may prefer to use the ATM for the same purpose rather thangoing and using a passbook printing kiosk available at the branch.

5.3 Test of hypothesesThree attitude items for each SSBT were included in our study. Therefore, nine itemswere included in the instrument for measuring attitudes toward the SSBTs. Theprinciple component and Varimax rotated factor analysis on the complete set of all nine

attitude items showed three separate factors. All three factors can also be seen by aScree plot, which is a graphical representation of the Eigen values for all the variables.The factor loadings for each SSBT were found much higher than the minimumacceptable values of 0.50. The factor loading values for each SSBT ranged from 0.789 to0.912 (see Table IV).

A multivariate technique (SEM) is mainly used to test and validate a model in thepresent study. The correlations among all the factors were measured while applyingthe SEM. The overall correlation model indicated a good fit with a significant χ 2-valueof 2.314, a comparative fit index (CFI) value of 0.963 ( W0.9), and a root mean squareerror of approximation (RMSEA) value of 0.0578 ( W0.05). The average varianceextracted for each construct ranged from 0.74 to 0.81 for all three attitude constructs

SSTs Items to measure attitude Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

ATMs (SST 1) Like/dislike 0.905Pleasant/unpleasant 0.876Good/bad 0.842

SSKs (SST 3) Like/dislike 0.912Pleasant/unpleasant 0.889Good/bad 0.821

Phone banking (SST 2) Like/dislike 0.904Pleasant/unpleasant 0.823Good/bad 0.789

Table IV.Results of

exploratory factoranalysis for attitude

measure

ATMs Phone banking SSKs

Response toward usageUsed 174 78% 22 13% 87 47%Never used 49 22% 145 87% 98 53%

Response toward AwarenessKnow that bank offers SST 155 93% 72 43% 135 73%Know that bank does not offer 05 03% 38 23% 35 19%Do not know whether bank offers or not 07 04% 57 34% 15 8%

Table III.Usage and

awareness regardingdifferent SSTs

107

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 15/29

across the different SSBTs. All these values exceed 0.5, the minimum acceptable valuesindicating the validity of all constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Netemeyer et al.,1997). If the average variance extracted for each construct is higher than the square

of the correlation between the constructs, then discriminant validity is demonstrated(Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001; Fornell and Larcker, 1981). For each case in ourmeasurement model, the lowest average variance extracted is 0.71, which is muchhigher than the highest squared correlation value (0.27). Therefore, it provides evidencefor discriminant validity between all our constructs. The results from the factoranalysis and correlation analysis of SEM provide evidence for three separate anddistinct attitudes toward each of the SSBTs supporting our first hypothesis ( H1 ).

The average sum scores of attitude toward each of SSBTs were analyzed andcompared in Table V. The attitude construct was measured by a seven-pointdifferential scale with endpoints of the most positive attitude indicated by a value of 1to the most negative indicated by a value of 7. The mean values of this attitudeconstruct for were 2.73, 4.32, and 3.36 for ATMs, PB, and SSKs, respectively. Thissupports the fact that the people who participated in our study had a more familiarattitude toward ATMs, followed by SSKs and the least favorable attitude toward PB.

These scores were further compared in order to analyze significant differencesbetween attitudes toward adoption of all three SSBTs. To do so, a paired-sample t -testwas applied that showed significant differences between each of the possible pairs of all three SSBTs. When we compare the t -values in Table V, it shows that the maximumdifference in attitude exists between the ATM and PB and then PB and SSKs. Theset -values in both cases are more than 11, on the other side, the t -value between PBand SSKs is just seven. However, all are highly significant with a significant p-value(0.000o0.001). Earlier we discussed that the most widely used SSBT are ATMs,followed by SSKs and then PB. Thus, our findings here provide sufficient support for

our hypothesis ( H2 ) that the most positive attitude is toward the highly adopted SSBT(ATMs) and the least positive attitude is toward the poorly adopted SSBT (PB).

5.4 Test of antecedent beliefs hypothesesAs introduced earlier, there are four antecedent beliefs that were presumed to influenceattitudes toward each of the SSBTs. In our analysis, SEM plays a crucial role for testingall the hypotheses of antecedent beliefs. The sample size of 619 respondents and aminimum of 167 respondents for each of the SSBTs are adequate for applying the SEM (Hair et al., 1998). Each of the models tested in our study consists of four similarantecedent beliefs as main constructs with either three or four scale items, anotherconstruct of “attitudes toward SSBTs” with three-scale items, and a single-itemconstruct “intention to adopt or use SSBTs.” Therefore, we have 17 observed variablesand 153 data points included in our model (Byrne, 2001). The number of estimated

Scale Mean Paired difference Correlation t -value df Sig.

Average ATM Scale 2.73 −1.59 0.37 −18.26 109 0.000Average PB Scale 4.32Average ATM Scale 2.73 −0.63 0.28 −7.23 109 0.000Average SSK Scale 3.36Average PB Scale 4.32 −0.96 0.43 −11.02 109 0.000Average SSK Scale 3.36

Table V.Paired sample t -test

108

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 16/29

parameters in each test for all three models of the three SSBTs is 44, which denotes 109degrees of freedom for all three tests. Thus, this model is recursive in nature and itsidentification should not be problematic (Hair et al., 1998).

5.4.1 ATM model . A total of 223 respondents replied to all the questions related toATMs. The χ 2-value of ATM model was 229.637 with degree of freedom 109, providinga ratio of χ 2/dof giving a value 2.10, which is quite acceptable with a significant p-value.The RMSEA value of 0.089 is a bit higher but lies within acceptable limits. The CFIvalue of 0.95 is well acceptable. The R 2-value showing the proportion of varianceexplained by independent variables for dependent variables are 59.7 percent for attitudestoward ATMs and 49.8 percent for behavioral intentions to adopt or use ATMs. Boththese values indicate their large effect sizes. The path analysis shows a significant path(at the 0.001 level) from attitude toward ATMs to behavioral intention to adopt ATMssupporting our third hypothesis ( H3 ). In Figure 2, we find the path coefficient (0.213) fromease of use to attitudes toward ATMs was also significant at the 0.05 level, while the path

coefficient (0.617) from PU to attitude toward ATMs was also significant at the 0.001level. Both of these support H4 and H5 . The paths from the last two constructs (i.e. needto interaction and PR) to attitude construct were not found significant enough eitherat the 0.001 level or 0.05 level, therefore we do not have support for H6 and H7 for theATM model.

5.4.2 PB model . A total of 185 responded to questions related to PB. It was found tobe the least adopted technology out of all three SSBTs included in our study. It maybe that the PB model is not quite as strong as the ATM model. The χ

2-value of thismodel was 279.789 with same degree of freedom (109), resulting a ratio 2.56 between thechi-square and degree of freedom values, which is still well acceptable. The RMSEAvalue of 0.093 is much higher but once again lies within acceptable limits of o0.1

(Browne and Cudeck, 1993). The CFI value of 0.907 is once again acceptable.The proportion of the variance explained ( R 2 ) by independent variables for both thedependent variables are 32.7 and 19.2 percent for attitudes and intentions toward PB,respectively. These once again indicate their large effect sizes. The path from attitude

0.213**

R 2 = 0.498R

2 = 0.597

2 / dof = 2.1

Ease of Use

Intention toadopt or use

SSTs

Perceived

Usefulness 0.753*0.617* Attitudes

toward SSTs0.019

PerceivedRisk

Need ofInteraction

0.037

CFI = 0.95

RMSEA = 0.089

Notes: * p<0.001; ** p<0.05

Figure 2.ATMs model

109

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 17/29

to intention is again significant at the 0.001 level and supports H3 . In this case, only thepath from PR to attitude toward PB was found significant enough at the 0.001 level,which provides support for H7 and no support H4, H5 , and H6 (Figure 3).

5.4.3 SSKs model . A total of 185 respondents answered questions related to SSKs.The χ 2-value of ATM model was 239.324 with same degree of freedom of 109, providinga ratio of χ 2/dof for a value of 2.19, which is once again acceptable with a significant p-value. The RMSEA value of 0.083 is high but lies within acceptable limits. The CFIvalue of 0.91 is again acceptable. The proportion of the variance explained ( R 2 ) byindependent variables for dependent variables are 43.3 and 39.2 percent for attitudestoward SSKs and for behavioral intentions to adopt SSKs, respectively. Both of thesevalues indicate their large effect sizes. The significant path from attitudes toward SSKsto behavioral intention to adopt SSKs supports H3 . Only the path from PU to attitudetoward PB was found significant enough at the 0.001 level. Hence, it supports H5 butinsignificant paths from the three remaining antecedents to attitude construct (i.e. ease

of use, need to interaction, and PR) do not support H4, H6 , and H7 (Figure 4).

6. Conclusion and implications of study6.1 Summary of findingsBy comparing adoption behavior across different SSBTs, our findings clearly showedhow factors predicting customer’s attitude vary across these technologies. Table IIIreveals how adoption varies from one technology to other by showing ATMs as themost widely accepted SSBT (78 percent) followed by SSKs (47 percent) and PB (13percent). The difference between ATMs and PB adoption implies the fundamentaldifference in their appeal to service customers in the banking industry. In addition,there is a significant difference between the mean attitude toward ATMs (2.73) and the

mean attitude toward SSKs (3.36) with ATMs being better thought of by customersas compared to SSKs. Surprisingly PB, which has been available long before SSKs, hasnot achieved widespread adoption by banking customers. Customers ’ attitude toward

R 2 = 0.192R

2 = 0.327

2 / dof = 2.56

Ease of Use

0.113

Intention toadopt or use

SSTs

Perceived

Usefulness 0.553*0.043 Attitudes

toward SSTs0.014

Perceived

Risk

Need ofInteraction

0.691*

CFI = 0.90

RMSEA = 0.093

Notes: * p<0.001; ** p<0.05

Figure 3.Phone banking model

110

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 18/29

PB is significantly more negative as compared to ATMs and SSKs. This suggests theneed for improving the marketing appeal of PB.

The present research emphasized a comparison of these SSBTs in order to identifythe key factors that affect their adoption by customers. Service providers mayanticipate these factors as critical to the proper implementation of various SSTs intheir firms. In the present research, we have already confirmed that the more positive

the attitude toward any SST, the more widely it will be adopted, but what drivesthe customers’ attitude toward SSTs is also very important. We have tested fourantecedent beliefs and interestingly their impacts vary across different SSBTs. We alsofound that PU is a significant predictor of attitudes toward ATMs as well as towardSSKs, but not for PB. Similarly, PEOU was found a significant predictor of attitudetoward ATMs, but surprisingly not for the other two SSBTs. This finding reveals thatusefulness is more important than how to use in case of SSKs and PB. PR was found tobe a significant predictor of attitude toward PB. This shows that people do not wantto use PB due to associated risks. Thus, different antecedent beliefs need to beconsidered while designing and implementing SSTs.

However, the findings of our study do not completely support several other studies.

For instance, Curran and Meuter (2005) suggested PU as a key predictor of attitudetoward PB and PR as a key predictor of attitude toward online banking adoption. Thiscontroversy might have occurred because different contexts, since we targeted bankingcustomers in India while they studied populations in northwest USA, which is acomparatively more developed location. Surprisingly, none of the three tested modelsshowed any significant relation between “need for interaction” and attitude toward anyof the SSBTs. However that does not mean it is not an important construct. In fact, itmust be concluded that its role as a predictor of attitude is not supported by our study.

As we have discussed earlier, two of the SSBTs included in our study (ATMs andPB) have a huge difference in terms of adoption by the banking customers. However,these two SSBTs have been available for a long time in the present context.

The statistics in Table III clearly show that ATMs have been widely accepted, but PB

Ease of Use

0.013

Intention to

adopt or use

SSTs

Perceived

Usefulness 0.614*0.693* Attitudes

toward SSTs0.117

Perceived

Risk

Need of

Interaction

0.081 R 2 = 0.392R

2 = 0.433

2 / dof = 2.19

CFI = 0.91

RMSEA = 0.083

Notes: * p<0.001; ** p<0.05

Figure 4.SSKs model

111

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 19/29

has not. If we compare the models of these two SSBTs, it shows that not even a singleantecedent belief significantly influences both the SSBTs. In case of ATMs, PEOU,and PU were two key influencers, while in other case of PB, only PR was found an

important factor that negatively affects attitude toward adoption. By combining theresults of adoption rates and path analysis in the models, it is reasonable to concludethat banking customers widely adopt SSBTs that are easy to use and useful for them,but not those with a certain degree of risk. However, this comparison also presents alimitation since it does not clearly show whether the low adoption rate is causedby the technology design used by banks in case of PB or a promotional issue.Therefore, additional empirical studies are needed to clarify this issue of lowacceptance rate of PB.

In the case of SSKs, the results of the structural model show that only PU was asignificant predictor of attitude toward SSKs. In this situation, it can be concluded thatbanking customers perceive it as useful since it ultimately offers many services likecash/cheque deposits, passbook printing, and queue tokens, etc. Comparing the resultsof the SSKs and ATMs structural models shows that ease of use is a significantpredictor of attitude toward ATMs, but not of attitude toward SSKs. This reveals thatcustomers treat SSKs as useful technology causing a good adoption rate (47 percent),but not ease of use since they are relatively new. Therefore, we can conclude thatbanking customers reactions are positive, but more efforts are required to increasecustomer’s awareness about the use of SSKs.

There are two primary marketing issues faced by service firms implementing SSTs.The first issue is customer reaction to the design of SSTs and second is customers ’

education regarding how to use and ease of use. However, a service customer mighthave problems understanding an entirely new SST (Li and Calantone, 1998) becausethey are only familiar and comfortable with their habitual services. Therefore, any SST

should be designed in a way that combines new technology with a service encounterthat customers are already familiar. This will increase the chances of adoption.

Finally, we can conclude that the widespread adoption of SSBTs must be useful andeasy to use as in the case of ATMs. If any SSBT (like SSKs) is simply being useful butnot easy to use, it is comparatively less adopted by banking consumers. This findingprovides a fact that marketing strategies must address the antecedent beliefs thatare even more important for a specific SST. In the case of PB, service providersmust overcome consumer uncertainties regarding its secure use and then developappropriate marketing strategies. Banking consumers do not find PB as useful or easyto use as other SSBTs (e.g. ATMs and SSKs). In our case, the (13 percent) adoption ratewas 13 percent, which is quite low compared to other SSBTs. If PB is easy to use,

then this should be made clear to banking customers with effective advertisingstrategies. However, if it is not so then banks must change their equipment to makethem easier to use.

6.2 Theoretical implicationsWhile past studies have contributed a considerable amount to understanding as to whycustomers adopt new technologies, our findings also contribute theoretically to theliterature in several ways. First, the present study shows that the basic TAM (Davis,1989) can also be extended by adding two external variables (i.e. need to interaction andPR) and is applicable in the context of banking technology adoption. Additionally, thisstudy contributes to technology adoption literature by including two external variables

while recent studies examined adoption with different variables like technology

112

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 20/29

readiness toward SSTs (Parasuraman, 2000; Lin and Hsieh, 2006), social environmentalvariables (Shi et al., 2007), individuals’ psychological variables (Yoon and Steege, 2013),and so on.

Second, with a few possible exceptions (e.g. Curran and Meuter, 2005) this study isthe only recent study that has compared different SSBTs in a developing countrywith the objective to identify and differentiate key factors affecting attitude towardadoption. Many studies reported that PR negatively affects technology adoption(Kim et al., 2010; Lee, 2009; Grabner-Kräuter and Faullant, 2008). However, in somesituations, customers are weighing risk and usefulness and are willing to make trade-offs between these two (i.e. risk and usefulness) that motivates them to use or acceptnew technology. These potential trades-offs, where a customer weighs the importanceand role of different factors in their adoption decision process, have not been widelyexplored in past studies (Yoon and Steege, 2013). Our findings show that customerswith lower risk and security concern may be willing to trade off because of the highPU as in the case of ATMs and SSKs.

6.3 Managerial implicationsOur study also provides several implications for service providers. It supports the factthat multiple factors are at work for different SSTs and some factors are moreinfluential than others under certain conditions. SSTs that are useful, well-planned, andeasy to use are more widely adopted by service consumers (e.g. Meuter et al., 2000; Yen,2005). The findings of our study will help service providers plan and design effectiveSSTs in order to provide more efficient consumer services. The majority of consumers(34 percent in the case of PB) claimed they did not receive any information on PB fromtheir respective banks. Thus, banks need to pay more attention to how well they deliverthe message about the availability of SSTs and their advantages to consumers.

If the innovations and their associated advantages can be properly conveyed toconsumers, it will reduce resistance to innovation adoption (Ram, 1987). Hence,effective communication strategies need to be developed to maximize customers’awareness of SSTs availability.

A close examination of all three SSBTs included in the present study show thatall three.

SSBTs can be differentiated in terms of their role in service encounters. Each of thethree technologies has different predictors of attitude. As mentioned earlier, the newestSSBT (i.e. SSKs) had PU as a significant predictor, while the more established SSBTs(i.e. ATMs and PB) had entirely different predictors. For instance, ATMs had PEOUand PU as key predictors, while PB had PR as a significant predictor. Thus, the PU is

the common predictor for two of the most widely adopted SSBTs. This denotes thatany SST with usefulness has more chances of being adopted. Therefore, designersmust focus on effective technological functions and managers must communicate theiruseful points to customers. PB has been introduced for many years, but has not beenwidely adopted because of a risk factor. It seems logical that firms introducing arelatively new SST would have to deal with a period of risk or uncertainty untilprospective adopters have learned about the operation and benefits of the new SST. Tomake it more acceptable, bank managers must develop effective trial programs in orderto reduce the PR. Customer trialability (i.e. the degree to which a customer perceives thebank offering a chance for him/her to try IB prior to any decision to adopt) is considereda key variable in such a situation (Black et al., 2001). However, Puschel et al. (2010)

did not find any significant relationship between trialability and IB adoption.

113

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 21/29

7. Limitations and future research directionsAs in the case of any empirical research, there are various limitations to our study.First, we have included three SSTs only from the banking industry. This limits the

generalizablity to other industries. Our model can also be implemented in studies usingmultiple SSTs in various industries to provide additional support to our study. Second,other factors like technology readiness, trust, and subjective norms could be includedto increase the predictive power of attitude construct. Next, the use of an onlinequestionnaire can increase response error because they may fill out the questionnairearbitrarily due to a lack of clarification assistance.

We have explored a relatively new area of research on consumers’ adoption of SSTs,where approximately half of the variance in attitude toward SSTs can be explained byconstructs included in our study. However, it is crucial to identify the other key factorsthat account for the other of the half variance. Another important suggestion forfurther studies relates to the usage of multiple channels in service encounters. Serviceconsumers are not only faced various SSTs in service organizations, but also haveseveral SST modes of SSTs (Patrício et al., 2003) that perform similar services to choosefrom. The majority of studies emphasized consumer behavior toward specific SSTs tounderstand why consumers adopt a specific SST. While it is important to understandwhy they choose one SST over another and what are the key variables affecting theirdecisions to adopt, It is more important from a firms ’ point of view because the costs of implementation vary across SSTs. Future research may consider the impact of variousfactors/antecedents on innovativeness in different stages of consumer’s adoptionprocess. A traditional six-step adoption process that begins with awareness and leadsto commitment illustrates how our research relates to the process of innovationadoption and commitment (Rogers, 2003). Until now, it is not well understood whycustomers decide to try SSTs and why some SSTs are more widely accepted than

others. For this, further studies should focus on how the different factors/antecedentsaffect the different stages of the adoption process. For instance, Meuter et al. (2005)explored key factors that influence the initial SST trial decision. With past studiesfinding evidence for the relationship between attitude and intention constructs (Chauand Hu, 2002; Chen et al., 2002; Vijayasarathy, 2004), attitude is also predicted to actas a mediator between various antecedents and intention to use technology. Since, thepresent study mainly aims at comparing key antecedents for different SSTs in banking,and not considering the mediating effect of attitude between antecedents and intentionto adopt, which provides an additional path of research.

References

Adams, D.A., Nelson, R.R. and Todd, P.A. (1992), “Perceived usefulness, ease of use, and usage of information technology: a replication”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 227-247.

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980), Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior ,Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Alhudaithy, A.I. and Kitchen, P.J. (2009), “Rethinking models of technology adoption for internetbanking: the role of website features”, Journal of Financial Services Marketing , Vol. 14No. 1, pp. 56-69.

Barki, H. and Hartwick, J. (1994), “Measuring user participation, user involvement, and userattitude”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 59-82.

Bateson, J.E.G. (1985), “Self-service consumer: an exploratory study”, Journal of Retailing , Vol. 61

No. 3, pp. 49-76.

114

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 22/29

Berger, C.R. and Calabrese, R.J. (1975), “Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond:toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication”, Human Communication Research, Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 99-112.

Black, N., Lockett, A., Winklhofer, H. and Ennew, C. (2001), “

The adoption of internet financialservices: a qualitative study”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management ,Vol. 29 No. 8, pp. 390-398.

Blackhall, L.J., Frank, G., Murphy, S.T., Michel, V., Palmer, J.M. and Azen, S.P. (1999), “Ethnicityand attitudes towards life-sustaining technology”, Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 48No. 12, pp. 1779-1789.

Browne, M.W. and Cudeck, R. (1993), “Alternative ways of assessing model fit”, in Bollen, K.A.and Long, J.S. (Eds), Testing Structural Equation Models, Sage, Newbury Park, CA,pp. 136-162.

Byrne, B.M. (2001), Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming , Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ.

Celik, H. (2008), “

What determines Turkish customers’

acceptance of internet banking?”

, International Journal of Bank Marketing , Vol. 26 No. 5, pp. 353-370.

Chan, S.C. and Lu, M.T. (2004), “Understanding internet banking adoption and use behavior:a Hong Kong perspective”, Journal of Global Information Management , Vol. 12 No. 3,pp. 21-43.

Chau, P.Y.K. and Hu, P.J. (2002), “Examining a model of information technology acceptance byindividual professionals”, Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 18 No. 4,pp. 191-229.

Chaudhuri, A. and Holbrook, M.B. (2001), “The chain of effects from brand trust and brandaffect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty”, Journal of Marketing , Vol. 65 No. 2,pp. 81-93.

Chen, L.-D., Gillenson, M.L. and Sherrell, D.L. (2002), “

Enticing online consumers: an extendedtechnology acceptance perspective”, Information & Management , Vol. 39 No. 8,pp. 705-719.

Collier, J.E., Sherrell, D.L., Babakus, E. and Horky, A.B. (2014), “Understanding the differences of public and private self-service technology”, Journal of Services Marketing , Vol. 28 No. 1,pp. 60-70.

Cunningham, L.F., Young, C.E. and Gerlach, J. (2009), “A comparison of consumer views of traditional services and self-service technologies”, Journal of Service Marketing , Vol. 23No. 1, pp. 11-23.

Curran, J.M. and Meuter, M.L. (2005), “Self-service technology adoption: comparing threetechnologies”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 103-113.

Curran, J.M., Meuter, M.L. and Surprenant, C.F. (2003),“

Intentions to use self-service technologies:a confluence of multiple attitudes”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 209-224.

Daamen, D., van der Lans, I. and Midden, C. (1990), “Cognitive structures in the perception of modern technologies”, Science, Technology, and Human Values, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 202-225.

Dabholkar, P.A. (1992), “Role of affect and need for interaction in on-site service encounters”, inSherry, J.F. and Sternthal, B. (Eds), Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 19, Associationfor Consumer Research, Provo, UT, pp. 563-569.

Dabholkar, P.A. (1994), “Incorporating choice into an attitudinal framework: analyzing models of mental comparison processes”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 100-118.

Dabholkar, P.A. (1996), “Consumer evaluations of new technology-based self-service options: aninvestigation of alternative models of service quality”, International Journal of Research in

Marketing , Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 29-51.

115

Innovationadoption

across SSBTs

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 23/29

Dabholkar, P.A. (2000), “Technology in service delivery: implications for self-service and servicesupport”, in Swartz, T.A. and Iacobucci, D. (Eds), Handbook of Service Marketing and Management , Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 103-110.

Dabholkar, P.A. and Bagozzi, R.P. (2002), “

An attitudinal model of technology-based self-service:moderating effects of consumer traits and situational factors”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 30 No. 3, pp. 184-201.

Davis, F.D. (1989), “Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 319-339.

Davis, F.D., Bagozzi, R.P. and Warshaw, P.R. (1989), “User acceptance of computer technology: acomparison of two theoretical models”, Management Science, Vol. 35 No. 8, pp. 982-1003.

Dimitriadis, S. and Kyrezis, N. (2011), “The effect of trust, channel technology, and transactiontype on the adoption of self-service bank channels”, Service Industries Journal , Vol. 31No. 8, pp. 1293-1310.

Eagly, A.A. and Chaiken, S. (1993), The Psychology of Attitudes, Harcourt Brace College

Publishers, Fort Worth, TX.Eriksson, K. and Nilsson, D. (2007), “Determinants of the continued use of self-service technology:

the case of internet banking”, Technovation, Vol. 27 No. 4, pp. 159-167.

Eriksson, K., Kerem, K. and Nilsson, D. (2008), “The adoption of commercial innovations in theformer central and eastern European markets: the case of internet banking in Estonia ”, International Journal of Bank Marketing , Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 154-169.

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975), Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction toTheory and Research, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Fitzsimmons, J.A. (2003), “Is self-service the future of services?”, Managing Service Quality,Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 443-444.

Forbes, L.P. (2008), “When something goes wrong and no one is around: non-internet self-servicetechnology failure and recovery”, Journal of Service Marketing , Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 316-327.

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservablevariables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50.

Garg, R., Rahman, Z. and Kumar, I. (2010), “Evaluating a model for analyzing methods used formeasuring customer experience”, Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management , Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 78-90.

Gatignon, H. and Robertson, T.S. (1991), “Innovative decision processes”, in Robertson, T.S. andKassarjian, H.H. (Eds), Handbook of Consumer Behavior , Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs,NJ, pp. 316-348.

Grabner-Kräuter, S. and Faullant, R. (2008), “Consumer acceptance of internet banking: theinfluence of internet trust”, International Journal of Bank Marketing , Vol. 26 No. 7,pp. 483-504.

Griffy-Brown, C., Chun, M.W.S. and Machen, R. (2008), “Hilton hotels corporation self-servicetechnology”, Journal of Information Technology Case and Application Research, Vol. 10No. 2, pp. 37-57.

Hair, J.F. Jr, Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L. and Black, W.C. (1998), Multivariate Data Analysis, 5thed., Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Harrison, D.A., Mykytyn, P.P. Jr and Riemenschneider, C.K. (1997), “Executive decisions aboutadoption of informationtechnology in small business: theory and empirical tests”, Information Systems Research, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 171-195.

Hilton, T., Hughes, T., Little, E. and Marandi, E. (2013), “Adopting self-service technology to do

more with less”

, Journal of Service Marketing , Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 3-12.

116

IJBM 33,2

7/26/2019 Kaushik 2015

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/kaushik-2015 24/29

Hinson, R.E. (2010), “Banking the poor: the role of mobiles”, Journal of Financial Services Marketing , Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 320-333.

Igbaria, M., Guimaraes, T. and Davis, B.D. (1995), “Testing the determinants of microcomputer

usage via a structural equation model”, Journal of Management Information Systems,Vol. 11 No. 4, pp. 87-114.

Igbaria, M., Parasuraman, S. and Baroudi, J.J. (1996), “A motivational model of microcomputerusage”, Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 127-143.

Jackson, C.M., Chow, S. and Leitch, R.A. (1997), “Toward an understanding of the behaviouralintentions to use an information system”, Decision Sciences, Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 357-389.

Kallweit, K., Spreer, P. and Toporowski, W. (2014), “Why do customers use self-serviceinformation technologies in retail? The mediating effect of perceived service quality”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 21 No. 3, pp. 268-276.

Kasavana, M. (2008), “The convergence of self-service technology”, Hospitality Upgrade, August27, Hospitality and Tourism Complete database, spring, pp. 122-128.

Katuri, S. and Lam, M. (2006), “Switching customers from branches to internet: a credit union ’s journey”, Journal of Financial Services Marketing , Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 229-248.

Kaushik, A.K. and Rahman, Z. (2014), “Perspectives and dimensions of consumer innovativeness:a literature review and future agenda”, Journal of International Consumer Marketing ,Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 239-263.

Kim, C., Mirusmonov, M. and Lee, I. (2010), “An empirical examination of factors influencingthe intention to use mobile payment”, Computers in Human Behavior , Vol. 26 No. 3,pp. 310-322.

Kolodinsky, J.M. (2004), “The adoption of electronic banking technologies by US consumers”, The International Journal of Bank Marketing , Vol. 22 No. 4, pp. 238-259.

Kumar, A. (2010), “Smartphone power: How can hotels harness and manage it?” HospitalityUpgrade, March 1, available at: www.hospitalityupgrade.com (accessed July 10, 2012).

Laukkanen, T. (2007a), “Customer preferred channel attributes in multi-channel electronic banking”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , Vol. 35 No. 5, pp. 393-412.

Laukkanen, T. (2007b), “Internet vs mobile banking: comparing customer value perceptions”, Business Process Management Journal , Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 788-797.

Laukkanen, T. and Cruz, P. (2009), “Comparing consumer resistance to mobile banking in Finlandand Portugal”, in Filipe, J. and Obaidat, M.S. (Eds), E-Business and Telecommunications,Springer, Berlin, pp. 89-98.

Laukkanen, T. and Pasanen, M. (2007), “Mobile banking innovators and early adopters: how theydiffer from other online users?”, Journal of Financial Services Marketing , Vol. 13 No. 2,pp. 86-94.