Journal Week 5

-

Upload

michael-j-stephenson -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Journal Week 5

Architecture Design Studio Three: Air

JOURNAL

Michael J Stephenson

contents

week 1 - Adding to the discourse of Architecture

pages 4-6

week 2 - Expression of interest

pages 11~...

introduction

When I started studying Architecture, I recall that in one of my very fi rsts lectures, we

were briefl y introduced to the notion of parametric design, and if I strain my memory, I seem

to recall it being described as designing on a mathematical grid. Coming fresh from a year of

studying in the Bachelor of Science degree, I found this notion of design comforting, for it seemed

to have rules, formulaes and strict solutions. Even with an infi nite number of variables possible,

each variable could only lead to one solution, which could be found through study. I did not see any

room for abitrary/creative decisions.

I continued to study with this notion of designing to a formula, which usually manifested as ratios

between components in my designs, and I felt uneasy when I made decisions based purely on

intuition or creative pulls.

Eventually, I came to understand that designing from intuition alone was not ‘wrong’, even if

I couldn’t explain the dimensions I had chosen for the design, or likewise, if I couldn’t explain

stylistic choices I made. I started this year believing that I could be far more creative and effi cient if

I just simply followed my intuition fi rst, and dissected my reasoning afterwards.

But now I fi nd that my studio class will be purely parametric and I am torn between which

approach to take. My understanding of the ‘mathematical grid’ has broadened, as has my

understanding of what variables are available to be manipulated... but my understanding of where

the intial idea comes from is still developing. Do I start with a pre determined volume of material

and change variables until I have a form? Or do I start with a form (developed arbitrarily) which I

then tweak through parametric design?

I can’t help but feel that the latter is not truly utilising the potential of parametric design, but I feel

that the former is too guilty of the same.

Perhaps you start with a formula, which you then add more variables to, and add limits, and venn

diagramtic exclusions/inclusions... though the formula need not concern numbers at all. I feel that

this line of thinking is what true parametric design should be, and that the manipulation of vectors

should be an expression of the manipulation of the variables that we fi nd in all architecture.

With this said, I think that Parametric Design can be the purest form of design, as it has the

potential to be totally free of the abitrary, whilst maintaning infi nite solutions as it will be the

creative character of the individual designer that chooses just how to manipulate the variables.

This will make up part of my argument for choosing Parametric Design in my Expression of

Interest response. I will also write a conclusion at the end of semester to compare how my ideas

have changed.

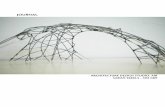

The project featured here fi rst is one of my own. It is a bridge I designed very early in my degree. The brief

was to design a bridge connecting the south and north sides of the yarra river, between Birrarung Marr and

theAlexandra gardens. The brief called for inspiration to be taken from the surrounding environment, and

designing with context in mind was a must. There were of course many ways to approach such a project, as

many different modes of design were in the vicinity to be referenced, that is to say, that the site laid itself open to

drawing from a multitude of different styles. Ultimately, I chose to reference the trees in the Alexandra gardens.

The elms trees in particular with their draping criss crossing branches, and the knobbly form of the fi g trees

bases, which created space within itself, that subsequently fi lled with earth and water and had sprouted new

plants within them.

The branches of the trees grew within and around each other in a way which at fi rst glance would look chaotic.

There direction looked unguided and unreasoned but at the same time looked ‘natural’ it looked right. This

organic form was something I wanted my design to mimic, for rather than the bridge looking purposely

conspicuous, as if saying, ‘Behold, My Architecture!’, I wanted it to almost be overlooked completely, until the

moment when one wished to cross the river and realised there was a bridge there.

Of course, building a bridge made to look like trees, would probably stick out more than technicolour monolith.

So what I ended up designing was a proposal for the management of the growth of four mammoth Moreton Bay

fi g trees, with a construction period of 200 years, and exceptionally diffi cult scaffolding designed to manipulate

and shape the growth of the trees (retrospectively I realise that Moreton Bay Figs would probably not have been

ideal for such a project). Its fi nal result would be four giant trees, two a side, growing out to meet each other

in the middle of the river, with the branches and intertwining to become a complex network. Finally, through

the voids and supported by cables and struts attached to the main ligaments of the trees, a slender wooden

pedestrian footbridge would be laid, hidden amongst the canopy.

week 1 - the discourse of Architecture

It would be an impossibly long term build, unheard of in this modern age.

It would be especially long considering the fi nal product would only be a simple footbridge.

For something so incredibly diffi cult to execute, the simple idea behind it was planting four trees.

It would raise questions about its worth.

It would raise argument for designing for the sake of aesthetics alone.

And the strongest contribution it would make would be as its encouragement to push the boundaries even

further...to think even further outside the box. Because, undertaking such a long term, and expensive build for

such minimal results is a ludicrous idea... one that no one would ever seriously consider.

But imagine if it had been built, and imagine how it would boggle the minds of those who saw it and knew its

history. They would probably shake their heads in disbelief and state the money could have been put to better

use. (Although there is equal chance that it would be viewed as a cheap alternative taken by the council, as

it could be interpreted that the trees were already there and that city planners took advantage of it and tied a

footbridge to it).

Image from - http://architectureau.com/calendar/exhibitions/a-new-building-for-the-university-of-melbourne/

Pictured are the design for Melbourne University’s new Architecture Building, and CH2 (Council House Two). Both are recent

projects (with the Architecture Building not even yet started) and both display similar qualities to each other. CH2 was an

important development for Melbourne, as it was the fi rst building to truly embrace sustainable architecture in it’s design.

Likewise, John Wardle Architects design for MU’s new Architecture building also incoporates its eco-friendly qualities into

the aesthetics of the design. Movable shutters to control the intake of sunlight are present in both designs, and both designs

embrace their form into the overall style of the building, rather than trying to conceal their presence.

What this adds to the discourse of Architecture is evidence for arguing that sustainable architecture can not only look ‘good’ but

can also have it’s own form and langauge which eventually may even experience a revival hundreds of years from now.

It could equally bring about discussion concerning whether sustainable architecture is restricted to a certain style, as ditacted by

the required forms of the sustainable features.

week 1 - the discourse of Architecture

Images from -http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/AboutCouncil/MediaCentre/ImageGallery/Pages/CH2imagegallery.

week 1 - Rhino Webinar Part 2 defi nitions

week 1 - Rhino Webinar Part 3 defi nitions

Above: example of what goes wrong when selecting curves individually, in this case whilst

using the loft command.

week 1 - the discourse of Architecture

Grasshopper Excercises

Development of Initial Idea

Development of argument for use of Parametric Design

week 2 - Parametric Design

Rotate AXIS

‘Mushroom’

RoRoRoRoRoRoRoRoRotatatatatatatt tteteteetetetetteeeeeeee AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAXXXIXXXXXIXIXIXIXIIX SSSS SSSSSSS SSSS

‘M‘M‘M‘MMMMMMMusususususususshrrrrrrrrhrhrhrhhhhhh ooooooooooooooooooooommmmm’m’m’mm’m’mmmmmmmm

EX-LAB BEND

GRASSHOPPER DEFINITIONS

week 2 - Parametric Design

Bezier Curves:

Standard (Above)

Loft Added (Left)

Rotate 3D

week 2 - Parametric Design

With Parametric Modelling comes a

entirely new method of design. The ability

to make countless iterations which can be

almost infi nite in their degrees apart, is made

relatively extremely fast and easy compared

to other methods (such as hand drawings or

computerized models). When used correctly

with the appropriate structure present in

programs such as ‘Grasshopper’, the slight

change of a single variable can drastically alter

the entire design. The scope possible from

such actions is infi nite and of a completely new

genesis compared to iterations by hand (or by

singular steps through computer modelling).

The designer can now experiment at his or

her fl eeting desire without having to invest

hours of work into an iteration which has no

guarantee of success. Instead, they can make a

couple of quick changes to variables concerning

things as simple as magnitude, or dimensional

plane, or the relationship between two discrete

components, and end up with a form which is

entirely unexpected.

As such, the use of Parametric Design should

not inherently present the risk of restricting the

creativity of the designer (due to the softwares

pre supposed ideas of the design process),

but rather present them with so much creative

freedom that the risk involved relates to having

too many ideas. Creative constraints will be

self-imposed by the designer, allowing for very

personal designs to be created (perhaps more

individual than those possible with pencil and

paper).

Rotation on Axis - 1

Rotation on Axis - 2

The only difference between these two forms,

is the ‘t’ input on the PERP FRAME node.

week 3 - Scripting Architecture

These are the results from the defi nitions on ‘Extracting Iso curves from a surface’. Creating a

curve in rhino, referencing said curve in Grasshopper and then Lofting gave rise to the above

form. Extracting the curves created the mesh like network of curves on the surface. I then added

a Sum Surfaces component into Grasshopper which has the inputs for a start and end curve. I

used the U direction output and V direction ouputs from the ISO component as these inputs. With

multiple start and end curves, all of which were in pairs, the resulting form has the same basic

structure as the original surface, but is now a series of surfaces.

I would put the form on the right down as one of the unexpected results one can get from

parametric operations. It is totally arbitrary, but none the less looks very interesting... a lot like a

turbine of sorts.

week 3 - Scripting Architecture

SECTIONING A SURFACE WITH HORIZONTAL PLANES

Grasshopper Defi nition I realise now after completing this excercise, that I

did not fully understand what I was doing at the time.

Retrospectively I see that this Grasshopper defi nition

is for creating uniform sections within a specifi c

boundary (something I should have grasped from

the title alone). This would be particulary useful

when it comes to creating section elevations for a

2D presentation, or more importantly, for allowing

detailed analysis of the model’s form during the

design process.

Funnily enough, I also discovered a second use

for this defi nition, albiet one which is probably

achievable through a shorter method. The intial lofted

surface (still visible in the above image) was quite

jagged and not at all a smooth form. After creating

the sections on the surface, I had a detailed mesh of

curves, which after baking into Rhino, I was able to

turn into a surface of much higher resolution than the

original.

ADDING A SURFACE ‘FROM CURVE NETWORK’ + RENDER

week 3 - Scripting Architecture

One of the recent projects I stumbled across during my travels on the internet is the Moon

Studio project. This project’s team consists of two architects and an astronautical physicist,

who are funded by NASA. Their goal is to design structures that could/would be built via

Contour Crafting, a process which uses robotic machines to build structures using materials

made from the moon’s geological composition. As this project is incredibly advanced, it will

no doubt involve serious scripting in every step of the design process. Designing structures

for such a foreign site will require constant testing and simulations to be run on the design

to check everything from its basic structural soundness, to its ability to protect again solar

storms, gamma rays, and of course the vacumn of space. The designs will therefore have to

be permenantly integrated into computer programs so that such things can be tested. And if

they will be built by robots, they will need to be blueprinted in exact accurate terms, so that

they can be built via more scripts. The robotic lunar machines will carry out a process much

like 3D printing that is currently in use in many studios around the world.

Aside from a practical need for CAD, the advantages of Parametric Design in this case are

clear. No doubt a huge number of iterations will be needed after every step of the testing pro-

cess, so the ability to easily manipulate discrete components and update the entire blueprint

instantly will be a certain must... Likewise, the ability to manipulate the quantity of the same

component at once, and/or update its relation to adjoining components will certainly be an

absolute necessity.

Furthermore, designing for the moonscape is a completely new realm for Architecture,

and surely traditional modes cannot apply here (or rather, should not apply here). The style

should be a unique style that is both akin with the moon, and also only possible on the moon.

The gravitational differences surely throw traditional load bearing structures out the window,

and allow a much larger choice of solutions. The possibilties available to exploit materials to

whole new levels open up relatively infi nite design solutions. Using algorithms that express

the requirements of the structure, the limitations of the robotic builders, the necessary order

in which the structure need be built in order for the robotic builders to be able to complete

the design in the fastest and most effi cient way, can be used to create a script that nearly de-

signs the structure itself. Using algorithms from nature can help design a growth system that

would allow the structure to become its most effi cient and most intuitive form.

Basically, in a realm of which not one person has enough experience of yet to truly under-

stand, how can architects who have never been to the moon, create a style suited to it? So

complex and intrepid with engineering is the design problem, that a design simply cannot be

calculated by hand alone. In such a harsh environment, and at the very beginning of architec-

ture here, no choice can be made that is not purely functional. The design must be born out of

its practical use, with no concession being made to aesthetics alone.

RAMBLINGS ON PARAMETRIC DESIGN

That said, choices of the aesthetic which have no implication on the functionality of

the design still need to be made, and still need to be made creatively, ie, made by

humans, not robots, and this is the role of the Architect. For the absolute cutting

edge of mankind’s acheivements/endevours, what could be more suiting than the

cutting edge of mankind’s Architecture.

Like space exploration, Parametric Design is also a realm not yet fully understood,

and by no means has anyone discovered its full potential. The designs possible are

as infi nite as space itself. In an enviroment not yet used as a site for architecture,

the design solutions are beyond the grasp of our current knowledge.

Parametric Design is not traditionalist... it is futurist. It is the design method, which

style is that of infi nite possibilities.

Wyndham City is a town set to grow exponentially over the next few years, and

as such, its gateway should be a symbol of the city’s future. It will be designed by

technology bound to be outdated, but that was at the cutting edge at the time of the

idea’s conception. The design itself will grow, at least in the sense that it’s under-

standing, its meaning, its symbolism will grow with the city. It could even be far

beyond its time, and waiting for the city behind it to catch up with it... it will be a

point on the horizon which the city is aiming towards... it will symbolise the future,

not the past. It will be the new style, and the new style is only possible through

parametric design.

http://uscmoonstudio.blogspot.com.au/#!/

http://parasite.usc.edu/

http://blobwallpavillion.wordpress.com/page/4/

http://www.deathbyarchitecture.com/searchBookmarks.html?method=SearchTag

&tag=scripting

week 3 - Scripting Architecture

This is a project called BLOOM. Designed Parametrically it holds a form which is quite typical

of the design method... one which is elegant, light, fl uid, and contemporary. Additionally, its

integration in to software allows its components to be ordered, numbered, and cut using an

automated laser cutter.

I have included it here as I believe it has very close similarities to our brief for the Western

Interchange Gateway. It is an installation piece, with no purpose further than to create dis-

course. It contains elements which are present in architecture, mainly, the enclosed spaces it

creates, and the role of light in such places. Furthermore, and most importantly, it has been

designed with thermodynamics in mind...

This particular project bears important relation to my own ideas, in that I have been toying

with the idea of creating a structure that changes with time, so to symbolise the growth of the

city of Wydnham. What is special about ‘Bloom’ is that it is constructed of hypersenstive sheet

metal, that when heated (ie when exposed to sunlight) it curls up, mimicking the actions of a

fl ower.

Designing such a structure outside the realm of modelling software would be an ardious task

fi lled with constant iterations. Here is the clear advantage of parametric design.

SECTIONING A SURFACE WITH HORIZONTAL PLANES

http://dosustudioarchitecture.blogspot.com.au/

week 3 - Scripting Architecture

Sectioning a Solid using a movable point

and variable plane rotations.

This is a very useful defi nition to know. It

allows you to turn your 3D model (a solid)

into a bounding box, and then project

planes onto it. The projected planes can

then be used as sectional cuts through

your model.

week 3 - Scripting Architecture

3D SERIES ARRAY MOVE Defi nition.

This script allows us to generate a huge

number of repeating forms very ‘cheaply’

(low use of Grasshopper components).

Ensuring to select the ‘Graft’ mode on the

output from the ‘MOVE’ component, we can

plug the results from a single dimensional

move into a second dimension, and again

into a third. It seems easily possible that

we could add more steps into the script

so that every repeating move is slightly

different... perhaps based on a random

number generator. We could design a

script that adds a different direction onto

every second repeat, which then goes

onto start its on series array. I imagine

this would be something like rampant cell

mutation, growing exponentially and out of

control.

week 3 - Scripting Architecture

ORIENT OBJECTS AROUND A CIRCLE

This defi nition allows us to create re-

peating copies of an object (in this case

a curve) around a circle. We have vari-

ables such as the radius of the circle

and the number of repeats (planes).

Simple manipulation of the radius can

give very dynamic results (on right).

week 4

CREATE A 3D GRID OF POINTS FROM REFERRED GEOMETRY

The defi nition for creating a 3D grid based

from a single referenced point in Rhino.

The defi nition for creating a 3D grid based from

a single referenced surface in Rhino.

I was unable to get this script to work correctly.

I had to reference the surface a second

time as the base geometry for the MOVE

component to acheive the bottom right form.

week 4

MOVE A GRID OF POINTS USING A MATHEMATICAL FUNCTION

Iteration 1

Iteration 2

Iteration 3

week 4

MOVE A GRID OF POINTS USING GRAPHS

week 4

MOVE A GRID OF POINTS USING A RANDOM FUNCTION

Here, I used the arbitrary curve

from the previous excercise

and added the random function

defi nition to it. I used a high

multiplication for the amplitude

of the random number

generator, so it resulted in

quite a tall form. I then baked

the resultant points into Rhino

and used an autosort ‘curve

from points grid’ command to

create a curve. I extruded the

curve in one direction, then

again in a different direction,

creating the 3D form seen here.