Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1 Spring 1989 - cdn.ymaws.com · and to take seriously the information on the...

Transcript of Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1 Spring 1989 - cdn.ymaws.com · and to take seriously the information on the...

Journal

of the

American Historical Society of Germans from Russia

Vol. 12, No. 1 Spring 1989

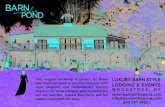

On the cover; These new and old (far left) buildings are located at the extreme north end of Rohrbach, Odessa

District. The house in the background is painted white and has a red tiled roof; the roof in the foreground is of a gray, corrugated material. The metal fence is painted a deep blue, and the brick columns supporting the fence are painted white. The grapevine in the foreground is about the only remnant remaining in the village of a once-thriving viniculture in this area.

Published by

American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 631 D Street • Lincoln, Nebraska 68502-1199 • Phone 402-474-3363

Edited by: Jo Ann Kuhr and Mary Rabenberg

® Copyright 1989 by the American Historical Society of Germans From Russia. All rights reserved.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A VISIT TO ROHRBACH, ODESSA DISTRICT, IN 1988 William M. Wiest ............................................................. 1

THE DUNDEE, KANSAS, COLONY Marjorie Andrasek ........................................................... 13

THE YOUNGEST CHILD Hertha Karasek'Strzygowski Translated by Sally Tieszen Hieb .........................………………................... 15

BUKOVINA-GERMAN PIONEERS IN URBAN AMERICA Sophie A. Welisch ...........……..............................................19

BOOK REVIEWS THE MENNONITE KLEINE GEMEINDE HISTORICAL SERIES

Reviewed by Edward R. Brandt................................................ 27 DIE INSEL CHORTITZA

FINSTERNIS UND LIGHT

LICHT UND SCHATTEN Reviewed by Lawrence Klippenstein ............................................ 28

MONETARY VALUES IN 1909 ................……………………………………………….................................. .29

SCHOOL DAYS IN GROSSLIEBENTAL .............................…………………………………………............. .30

WE SING OUR HISTORY…………………….. Lawrence A. Weigel.......................................................... 31

GAMES AND ENTERTAINMENT IN THE EARLY PART OF THIS CENTURY Solomon L. Loewen .......................................................... 33

THE POWER OF A PHOTOGRAPH Peter W. Schmidt............................................................ 39

A VISITOR FROM THE SOVIET UNION S.D.R.......................................................................41

BOOKS AND ARTICLES RECENTLY ADDED TO THE ASHGR ARCHIVES Frances Amen and Mary Rabenberg ............................................ 45

THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH IN KIND, VOLGA REGION ....…………………………….. .50

Three farm workers going to one of two stores on the east side main street in Rohrbach. The sign is for khieb, or bread.

A typical horse-drawn wagon in Worms. Note the German-style fence with white brick pillars.

The House of Culture (cultural center) near the center of Rohrbach. Note the statue of Lenin and the banner referring to the Nineteenth Congress of the Communist party of the Soviet Union.

This older house with the thatched roof is the first building seen at the entrance to Rohrbach.

ii

A VISIT TO ROHRBACH, ODESSA DISTRICT, IN 1988 William M. Wiest

Members of AHSGR with ancestral roots in Rohrbach, Worms, Landau, Speier, or any of the other former German settlements north of Odessa in the Berezan' Valley may well wonder about the current status of these villages and the general surrounding countryside; for example, do the villages still exist, and does the area remain as productive and beautiful as our forefathers described it? John Philipps, writing as someone who grew up there in the early part of this century, wrote "Nature has made the Beresan Valley one of the most blessed areas along the coast of South Russia. It is richly endowed with vast meadows, valleys, level plains (Steppes), green vineyards, flourishing gardens, golden wheat fields and overhead a deep blue sky.... No other land in the world can pride itself on such an abundance of black earth."1 In August 1988 my wife Thelma and I with my parents, Mr. and Mrs. William W. Wiest of Reedley, Califor-nia, traveled to Rohrbach to see for ourselves; we found that, although Rohrbach is much changed in some respects, this ancestral home to many North American Germans from Russia retains many of its former pleasant features. Situated about 65 miles north-northeast of Odessa, Rohrbach (renamed Novosvetlovka in Soviet times) can easily be reached by auto in a two-hour drive on paved and mostly quite good highways. In hindsight, getting to Rohrbach was not difficult, but considerable advance planning, determination, and just plain good fortune were essential ingredients of our trip there in 1988.

While growing up between Loveland and Greeley in Colorado, my father frequently had heard his parents refer to Rohrbach, where they had been born in the early 1880s. His parents, Friedrich Karl Wiest and Katherina Croissant, with two small children, Friedrich F. and Lydia (and another on the way—my father), had immigrated to the U.S. in 1908 from Stavropol in the North Caucasus, specifically from the village Friedrichsfeld (renamed Zolotarevka). Ap-proaching 80 years of age, my father has long hoped that he would have the opportunity to see the ancestral village of his parents and other relatives. This unforgettable opportunity came for our family in August 1988 while we were traveling in the Soviet Union with Assiniboine Travel, Ltd. of Winnipeg, Manitoba. Our tour group was composed primarily of persons with similar interests in tracing roots in "South Russia"; the tour was designed especially to allow detailed exploration of former Mennonite

villages—those in Khortisa near Zaporozhye, and those in Molochna, about 50 miles south-southeast of Zaporozhye. The ease with which tourists now visit the former Mennonite colonies inspired the four travelers in our family to apply for permission to visit Rohrbach, even though Rohrbach has never, to our knowledge, been on an official Intourist itinerary!2 Our Canadian travel agency had informed us in advance that there were no guarantees about such side trips, and this advice had been confirmed when we first made our request to Intourist in Moscow several days earlier. We were told, "Maybe it is possible—it will be more convenient to wait until you get to Odessa to apply," a reply that we feared might be the beginning of indefinite postponement.3

My father's parents, Friedrich Karl Wiest and Katherina (Croissant) Wiest, in 1929. Both were born in Rohrbach in the early 1880s. They immigrated to Colorado in 1908 with two children, Fredrick F. and Lydia, and had ten more children in America. My grandfather had been a leather worker in Russia, but in the U.S. he and my grandmother became dairy and sugar beet farmers near Johnstown, Colorado, and later they had vineyards and fruit orchards near Dinuba in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

1

In view of these uncertainties, we were delighted when our inquiry to the Intourist Service Bureau in Odessa produced a quick and favorable decision: "Yes," we could deviate from the planned itinerary in Odessa for one day, and "Yes," we would be allowed to go by auto to visit Rohrbach (Novosvetlovka)! I had described the approximate location of Novosvetlovka to our Soviet guide, though it was not listed on my road map (Eastern Europe, Freytag & Berndt, Vienna) which included the western U.S.S.R. Therefore, I was somewhat surprised when our Intourist guide so readily reassured us that we would be provided with a driver who would know how to find Novosvetlovka. It all seemed quite straightforward, and we were pleased that no further discussion seemed to be called for. Our car and driver were waiting for us outside the Krasnaya Hotel in Odessa at 9:00 a.m. the next day. Only a few words passed between our driver and the Intourist office personnel before we departed—at a wheel-squealing pace that made us all exchange concerned glances and hang on to anything in reach. Our driver spoke only Russian, and my knowledge of the language was quite rudimentary, so there was not a great deal of conversation. However, I could read the Cyrillic road signs and within 10 to 15 minutes became alarmed that we seemed to be heading in the general direction of Kiev or even more westerly. In response to my inquiry, our driver pointed out on my map the general area toward which he was heading—about 60 miles northwest of Odessa.4 To his consternation I then pointed out the area where we thought Novosvetlovka should be located, though neither his nor my map showed the village. I pointed to a region about 65 miles northeast of Odessa, about 10 to 15 miles west of the Bug river, somewhat south of Voznesensk and directly east of Berezovka. This description of the approximate location of Rohrbach was based on various maps by Karl Stumpp that I had studied before we left home, as well as on information about the location of Rohrbach provided by AHSGR. Though we had the Stumpp maps with us, I did not consider it quite politic to be waving "German maps" at our somewhat frustrated driver; so we agreed to return to the Intourist Service Bureau at the hotel for further consultation.

The flurry of discussion that followed made us increasingly concerned that the delay in our departure, as well as the general confusion about the location of Novosvetlovka, might cause our whole trip to be cancelled. Fortunately, personnel in the Service Bureau were quite willing to examine my Stumpp maps alongside their own

Three of Friedrich Karl Wiest's younger siblings in Russia; Katherina, Jakob, and Eduard. Only one of his sisters, Elizabeth, immigrated to North America; the rest of his family remained in Russia. After 1929 contact with them suddenly ended—until January 9, 1989, when a letter arrived from the Soviet Union. I had written to a Rudolf Wiest in Kustanai, Kazakhstan, to inquire if he had knowledge about my grandfather or any of his brothers and sisters who had stayed in Russia. The letter received on January 9 gave the names and current locations of the living children of my grandfather's four brothers and two sisters who had remained in Russia. By February we had received three letters from the Soviet Union, all in German. The whole family is now looking forward to continuing correspondence with my father's sixteen first cousins! We hope we will be able to meet these cousins soon.

2

and to take seriously the information on the postcard we had received from AHSGR showing the coordinates of Novosvetlovka (47 ° 12' N, 31° 11' E). The person in charge even placed telephone calls to a local Orthodox priest and to a Roman Catholic priest after I re-emphasized that Novosvetlovka had been a German (Lutheran and Reformed) village called Rohrbach; neither priest could confirm the location of Rohrbach (Novosvetlovka)—-nor even that it still existed. Finally, an hour and a half later, we left Odessa again, this time with the stipulation that there was no guarantee that we would get to our destination but that we should drive in the general direction and stop to ask for directions along the way. Earlier travelers to the Soviet Union hear this description of our being casually told to "go and look for it" with near disbelief—apparently glasnost is having impor-tant effects! Our driver seemed in good humor again and intent on making up for lost time by driving even faster than on our first departure.

To make matters worse, many trucks and tractors we passed were belching a black smoke screen. My family and I agreed that generally we were being driven about 50 percent faster than we considered safe. We later noticed that our driver was not atypical, and in fairness I should add that we witnessed only one minor accident in the relatively congested traffic of Odessa in the late afternoon.

The northeast side of Odessa ended abruptly. On one side of the road stood a mix of warehouses, factories, and rows of large, nearly identical apartment houses; on the other side, there was an alfalfa field that stretched almost to the horizon. In only a few minutes we were racing at 120 kilometers per hour along a straight four-lane divided highway6 that, for most appearances, could have been grazing land in the Texas Panhandle except for the long, swampy lakes ("limans") in many of the mile-wide swales breaking an otherwise flat land.

Street scene in Odessa as we were leaving for Rohrbach.

Before we were out of Odessa, we all hit the ceiling more than once as our too rapidly speeding car (an otherwise quite comfortable "Gaz") bucked like a bronco crossing railroad tracks or dips in the street; once we bypassed a very busy section where traffic was clogged with slow-moving tractors by leaping over the curb and doing a quick end run on a pothole-filled "frontage road." More than once we also found our two-lane road suddenly converted into three lanes when our driver impatiently passed a car, motorcycle, truck or tractor, in spite of oncoming traffic, all the while leaning hard on the car's horn.

Divided highway approximately 10 to 15 miles out of Odessa.

After about 20 miles the terrain became less hilly and the road narrowed to two lanes, still well paved and now bordered on both sides by a mixture of acacia, mimosa, and locust trees, many in bloom. Beyond the trees were fields of recently harvested grain (wheat or barley with the straw piled into round stacks every 50 feet or so), sunflowers in dazzling yellow bloom, alfalfa, corn, and other row crops, as well as pastures with grazing "Red German" and Holstein cattle. Very large tractors and modern combines were sitting in the fields along with somewhat primitive—looking wooden wagons, the latter

3

A pastel-colored (blue) house in Bere&ovka. 4

presumably for hauling straw. In the fields there were also smaller tractors pulling haying equipment—cutting, chopping, and blowing green alfalfa into trailers designed for unloading into trench silos by winch. Every half-dozen miles or so we could see clusters of large buildings about a quarter mile off the road; we supposed they were dairy and other farm buildings as well as apartments of state (or perhaps collective) farm workers. Only rarely did we see a single house or barn standing alone in a field or by the road. As we proceeded northward we remarked to one another several times on the surprisingly good condition of most of the roads; after we were about 30 miles from Odessa, most of the traffic consisted of large and small trucks and tractors pulling farm implements or trailers.

Approaching Berezovka we encountered our first intersection with a flashing red light. Our driver flagged another driver who stopped while they discussed how to get to Novosvetlovka. Apparently the advice was indirect for our driver continued to look puzzled, and shrugged his shoulders in a nye znayu (don't know) gesture,

as he turned left off the main road to drive a few miles into Berezovka. Except for a few random impressions, the town was rather nondescript: scattered, pastel houses (purple, yellow, blue, green, and pink) with embroidered curtains, several children and a mongrel dog dodging tractors and trucks scurrying on and across the road lined with dusty trees, rusting farm machinery, and the least appealing public rest rooms any of us had ever encountered. But profusely growing dandelions, pigweed, and other invasive green plants among the roses and dahlias of the public park were reassuringly familiar, and the warm, sunny, and slightly breezy midday (about 82° F) was quite pleasant.

Less than ten minutes after he left us to ask for further directions, our driver walked briskly back to the car. His gait and smiling face told the good news, elaborated by a head nod and hand gestures implying that he had learned something interesting. In my primitive Russian I asked him whether he now knew where to find Novosvetlovka and his reply was an immediate and enthusiastic "Da!"

This yellow arch is the entrance to Worms from the highway.

5

We were now off to Vinogradnoye,6 just a few miles up the road northeast of Berezovka. We stopped for about five minutes for further directions in this village (which we later learned was the former German village of Worms). The main part of this settlement seemed to be to the east of the highway; a large, yellow stucco-covered arch functioned as a kind of grand opening to the town; a gaggle of large black and white geese hovered near a clump of grass where a leaky faucet was dripping near the side of the road. Rubber-tired and wooden-wheeled wagons drawn by horses shared the streets with more trucks and tractors. I thought I recognized the pattern of a typical German village in the white-painted brick pillars that anchored ironwork fencing that ran alongside the road and in front of the village buildings. Beyond the fences houses were surrounded by locust trees in full bloom as well as an occasional walnut tree.

Our driver Grisha (we were now exchanging names, and he seemed to be becoming as enthusiastic about this adventure as we) used hand signals to say that we were within 10 to 15 kilometers of Novosvetlovka. A few miles up the road in a northwesterly direction, a small monument (displaying a schematic wheat plant and a red star) marked the spot where we made a sharp turn to the right, now heading south-southeast. Grisha said we were now within 7 to 8 kilometers of Novosvetlovka! We thought the countryside was particularly beautiful with very productive-looking, dark black soil, mostly level and planted into corn and alfalfa, but some freshly plowed. The road, now narrower and nearly straight all the way, was being re-asphalted for a few miles by grading equipment that looked much like any in North America.

At this marker the road to Rohrbach turns off from the main highway.

Sign, NOVOSVETLOVKA, at entrance to Rohrbach.

Most of the way the road was now thickly bordered on both sides by tall, healthy-appearing poplars.

We rounded a corner and saw a quite prominent sign, at least 20 feet high, "NOVOSVETLOVKA," followed soon after by the first building, a thatched-roofed structure with a woman standing nearby wearing the expected Russian-Ukrainian peasant head scarf. We proceeded all the way down to the end of "main street," a distance estimated to be about three-quarters of a mile. Main street ran along the east side of a quarter-mile-wide shallow valley; what appeared to be a small stream was about equidistant between this main street and another parallel street on the other side of the valley. Houses and larger buildings appeared to be much farther apart on the other street (west side of the valley); we pooled our estimates and arrived at the guess that there were from 150 to 200 houses and other buildings, and that 90 percent of all buildings appeared to be occupied houses. Only a small number of houses were clearly abandoned; these appeared to be very old, with crumbling stucco revealing the basic stone construction. All of the houses, even the few new ones, were built in a style described by Philipps; that is, most appeared to be about '*60 feet long, 30 feet wide, and 11 feet to the eaves" and have the gabled end facing the street.8 As was true in the past, most houses we saw were built of stone or brick; a few had reed-thatched roofs, and some older buildings still had red-tiled roofs with walls of stone or brick. The most common roofing material appeared to be a corrugated grey nonmetallic material, perhaps asbestos. The gables and windows of many houses, especially 6

the newer or better kept ones, were decorated with strips of wood carved in artistic patterns— perhaps reflecting recent Ukrainian influence.

As for the overall layout, we noted that the main street in Rohrbach looked very much like the descriptions given by Stumpp, Philipps, and others; for example, the wide street was bounded on both sides by a 50- to 60-foot-wide strip with trees (acacia, locust, and mimosa) and grass, with a narrow gravel-covered sidewalk between the trees and the fence fronting most houses. The continuous line of the fence, consisting of white-painted brick pillars supporting iron (and sometimes wooden) rods, was broken by a latched swinging gate in front of each house. Front and side yards of many houses had flower gardens with hollyhocks, morning glories, and ornamental plants, some rather overgrown, as well as apricot, walnut, and plum trees; other front yards were bare of any plants. We did not venture into any backyards, but what we could see suggested vegetable gardens, storage cellars (some caving in from disuse), chicken houses, wood piles, and

sometimes considerable disarray. The street scene was generally quietly pastoral, graced with the sounds of birds singing, mourning doves cooing in the trees, and roosters crowing in the backyards; this tranquil setting was frequently interrupted by passing trucks or tractors whose loudly whining transmissions seemed to this farm-raised witness's ears to call for lubrication! The main street was almost all paved, the exception being that part nearer the center of the village where two stores were located and where much of the truck and tractor traffic stopped or turned around. On the main street children (and some adults) rode by on bicycles, with playful dogs chasing them and chickens, ducks, and geese scattering. At midday most of the ducks and geese ceased wandering the street and the surrounding grassy strip, preferring instead to cluster in the moist shade of the acacia trees. During our less than three-hour stay in Rohrbach, we saw at least a half-dozen trucks and tractors, two horse-drawn wagons, and only two automobiles.

View of the main street (east side) from the north to the south.

7

We explicitly asked our driver to inquire regarding the location of the cemetery. It was about a quarter mile up a gently sloped road to the east—one of only two roads we saw perpendicular to the north-south orientation of the main street near the center of the village. The cemetery appeared to be square, perhaps 150 yards or more on each side; it was immediately obvious to us that even a cursory survey of the cemetery would require hours. In a hurried ten-minute glance, we did not find gravestones with German names, having time to examine only an ex-ceedingly small fraction of the rather large number of grave markers. Many graves had markers surrounded by fancy ironwork, and some had photos of the deceased and engraved words in the Cyrillic alphabet. We met a peasant

startled and became somewhat self-conscious: yet after a while she became very animated and friendly while talking to us in Ukrainian. After some frustrating moments of trying to communicate more about who we were and what we were interested in, we had to leave words aside and express our warmth to her with our smiles and gestures. She reciprocated in this nonverbal communication, and we all waved fond good-byes as we left the cemetery. Such an experience strongly reinforces one's intentions to learn more of the language before the next trip!

Grisha now took control, deciding that it was time for us to break into the sack lunches that Intourist had packed for us. He stopped at one of the two store-like places in the center of town, a building marked simply, Kafe, in Cyrillic. The

View of the cemetery in Rohrbach showing the ironwork surrounding many graves.

The KAFE where we ate our sack lunch prepared by Intourist. This was one of the two stores in Rohrbach.

woman in the cemetery who apparently had just laid fresh flowers at a grave. She seemed somewhat wary, yet curious about encountering four foreigners, two with cameras and a camcorder; a question put to her in German as to whether she spoke or understood German drew only an uncomprehending stare. But when I repeated the question in Russian she immediately answered 'Nyet' I then inquired (in Russian) whether she knew people living in the village now who could understand German, to which she replied in the affirmative. My further attempt to ask that she take us to these persons who spoke and understood German was apparently not successful—whether because she simply did not understand me or because she was hesitant to act on our request, I do not know. On learning that we were Americans, she at first looked

only other place in the village that appeared to be a store was directly across the street, with the simple sign for bread in Cyrillic, Khieb. After a moment Grisha motioned for us to come inside where he had arranged for our use of a table and chairs. The stop in a relatively cool place was a welcome relief, since the noon heat was approaching the upper 80s0 P. The main items available in the store seemed to be soft drinks, beer, coffee, tea, cold cuts, and cheese. But we had more bread, cheese, fried chicken, cold cuts, cucumber, mineral water, watermelon, and tomatoes than we could eat in our brown bags, so further purchases were not necessary. The woman in charge in the "cafe" sliced our watermelon and served it to us on plates with forks and spoons.

8

After our late lunch we continued to explore around the village. It was clear that we were somewhat unexpected curiosities to many of the villagers; yet they kept a polite distance and did not initiate conversation. We approached several groups of young people to say hello, to give them our best wishes, and to offer small metal "lapel pins" as gifts (of the sort that were received, even sought after, with great enthusiasm by Soviet youths in the cities). Three 18- to 20-year-old young men sitting on a motorcycle with sidecar seemed ill at ease by my offer, yet they accepted and said "Spasibo" (thank you). They seemed far more inhibited than the suave urban young people I had talked to the night before in Odessa— probably an unsurprising reflection of urban-rural differences in the amount of exposure to foreigners. It was easier to engage in simple talk with a group of four youngsters (three boys and a girl, all appearing to be 14 to 16 years old) who were sitting on a bench attached to the fence in front of a house. They were also quite shy, yet after we had visited awhile, they stood up and offered their seats to us (Sadites' pozhaluys ta). They seemed quite willing to try to understand my undoubtedly amusing Russian as long as I was willing to entertain them! Our general impression was that the current occupants of Rohrbach do not frequently see people from out of town, to say nothing of foreign tourists!

Other people we tried to talk to included three men who drove up in one of the two cars we saw in the village—to a large public building prominently displaying pictures of Marx, Engels, and Lenin. We thought the building, not far from the village center, might be a school, perhaps of 1950 vintage. One men wore a T-shirt with the English words, "SOS Marine" and a drawing of a ship's navigating wheel; we were not able to learn from them what the building was nor the significance of the shirt.

One of our most poignant encounters was with an elderly woman missing most of her teeth; she was carrying a bucket of fresh milk—foamy as if just extracted from a cow. (We later saw a milk receiving station a few hundred yards to the north toward which she was walking.) She seemed very eager to talk, but her speech was particularly hard for me to make out. My wife Thelma filmed our attempted conversation with a video camera while the woman gesticulated vigorously and spoke loudly (almost loud enough to be heard over the passing tractors and rattling, empty alfalfa trailers). I later learned from friends who understand Ukrainian that she was explaining that many of the houses in the village had been badly damaged or entirely destroyed during the last war, and that many of the houses had been rebuilt.

Three boys and a girl in front of a house in Rohrbach. The bench is attached to the fence.

9

A view of the west side of Rohrbach taken from the center of the east side where an unpaved road connects the two parallel streets.

One more large building deserves comment. It

was too big and its style too Soviet to be considered a former church; it appeared to be a community center, with large red banners extolling the Nineteenth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The building also had another feature that marks most Soviet public places—a large statue of Lenin dominating the open square in front of the building.

As we were leaving town, I snapped a picture of a grapevine growing near a house at the edge of town; this vine was the only evidence of what used to be a thriving wine-growing industry, according to Philipps. A few hundred yards later, I asked Grisha to stop so I could take a picture of the sign, NOVOSVETLOVKA. While we were parked on the side of the road, two older men in a truck stopped to talk to us. In response to my question they answered, "Yes, this is 'Old Rohrbach' and there is another place (gesturing toward the north) that the former German settlers called 'New Rohrbach.'" I was pleased to have that bit of confirmation that we had indeed been in the village of my grandparents, especially because of the confusion at the beginning of the trip and because various Stumpp maps show a

small "N Rohrbach" [Neu-Rohrbach] a few miles north of the old original settlement of Rohrbach.

What did we learn by visiting Rohrbach? Clearly, not as much as we would have liked to find out, but perhaps of most importance for a first trip was the discovery that the village still stands in the same place, and that it is possible to drive there from Odessa in about two hours. Our family hopes that our trip will encourage others from AHSGR to visit Rohrbach, Worms, Landau, Speier, and other former German communities near Odessa. Changes now being made in the Soviet Union (glasnost, and perestroika, for example) make this an extremely opportune time to travel there and to make meaningful human contact with people; we experienced much warmth from many people and felt that they are eager for more interaction with North Americans. Our trip was emotionally meaningful to each of us—an experience we will never forget. We also realize that we have barely scratched the surface in beginning to describe the current state of our ancestral village; clearly, with continuing intensive exploration, there is much more to be learned about the history and current status of these villages where unsere Leute lived.9

10

Notes

Philipps, John. The Tragedy of the Soviet Germans: A Story of Survival, (Privately published, 1983), p. 8. Intourist is the official Soviet agency that makes all travel arrangement's for foreign tourists. Such a fear was not entirely unfounded: when we first arrived in Moscow, we had also requested permission to travel to Stavropol while the remainder of our group went to Kiev or Yalta (with the plan to rejoin them at Alma Ata). In each city we visited, this request was met with, "Maybe, but it will be more convenient to apply in [the next city]"; eventually, the next city was the last, and we were not able to go to Stavropol. In fairness I should note that our request to visit Stavropol, from which we wanted to go to Friedrichsfeld (where my grandparents were married and where my father was conceived) was clearly of a different magnitude from the request to visit Rohrbach, in that it required changes in flight and hotel arrangements for several days. Unlike Saratov on the Volga (from which region my mother's parents, Karl A. Buxman and Maria Weber, emigrated in 1901), Stavropol is among the Soviet cities explicitly listed as available to foreign tourists; I intend to include Stavropol in the official itinerary on my next visit and hope that soon the Saratov region will also be open. On a 1986 Soviet map of the Ukraine and Moldavia, I later discovered that the area our driver was pointing to shows a small village named Novosvetovka, north-northwest of Tiraspol! (Note the missing letter"!" in this case!) To further confuse matters this Soviet map also shows a small town (less than 10,000) named Novosvetlovka a few miles southeast of Voroshilovgrad in the eastern Ukraine, north of Rostov-on-Don. A road map (Cartographia} of the Western Soviet Union printed in Hungary (1987) lists the latter Novosvetlovka, but not Novosvetovka; none of these maps show "our" Novosvetlovka, the former Rohrbach! The novice in matters Soviet should be aware that certain town and village names are used repeatedly; for example, the index for the aforementioned Soviet map shows four separate places named Novoselovka, two places named Novoselskoye, etc. Fortunately, one can find Novosvetlovka (formerly Rohrbach) on the Tactical Pilotage Chart (F-3B), produced by the Defense Mapping Aerospace Center, St. Louis, AFS, Missouri 63118. ATTN: PP (scale: 1: 500.000). On this map "Rohrbach" is shown as a village lying in a narrow valley with a small stream running through it in a southerly direction; the orientation and

shape of the village is nearly identical to that shown on Karl Stumpp's map Karte der deutschen Siedlungen im Gebiet (Oblast) Odessa (AHSGR Map ^2). The orientation and shape of the village is also shown quite clearly on a topographical map prepared by the Soviet Corps of Army Engineers in 1930, available at the Library of Congress. A photocopy of an RAF (Royal Air Force) aerial photograph taken directly over Worms and Rohrbach in the early 1940s also shows the two villages—in considerable detail-in precisely the orientation as depicted by Stumpp on his map. Further, one can make out the cemetery on the east side of Rohrbach on this photograph. I received this photograph from Mrs. Wilma (Wiest) O'Bannon of Stockton, California, just after we returned from the Soviet Union. This and aerial photographs of other villages may be obtained through the Cartographic & Architectural Branch (GSA), National Archives, Washington, D.C. 20408.

11

Map of Rohrbach prepared in 1930 by the Soviet Corps of Army Engineers at a scale of1:50,000. Map courtesy of Brent Mai.

On my map {Eastern Europe^ Freytag & Berndt, Vienna), the highway is unnumbered and about midway between Highway 20 north to Kiev and Highway 23 east to Nikolayev. When we returned to the U.S., I was surprised to discover in the book by Philipps that Vinogradnoye is the Russian name of the village of Worms, approximately 5 to 7 miles from Rohrbach, and shares much the same history and fate. We regretted that we had limited time (only about 2'/2 hours) to spend in Rohrbach and were therefore unable to make a more complete and quantitative record of what we saw. We did not go across the valley to the other parallel street, in part because our driver was hesitant to drive on what appeared to be a very bumpy, unpaved road connecting the two and in part because we did not have the time to walk there. Of course, we would have preferred to stay all day or longer, to count houses and other buildings, to get a better sense of the number of graves in the cemetery, and to look thoroughly for the old churches or their ruins. Philipps wrote that Rohrbach had a Neo-romanesque-style Evangelical Lutheran church with a bell tower on one side of the church and that there was also a Reformed prayer house, later made into a club house by the Soviets (p. 34).

Unfortunately, our driver was quite insistent that we leave Rohrbach in time to be back at our hotel in Odessa by 4:30 p.m., perhaps according to his instructions. Now that we know precisely how to get to Rohrbach, it is easy to plan how we will use this opportunity "next time"!

8. Philipps. p. 52. 9. I will be glad to provide copies of maps and detailed

instructions about how to drive from Odessa to Worms or to Rohrbach for anyone who plans such a trip. I would also offer the following advice: if you are reasonably comfortable with the Russian or Ukrainian language you can rent a car in Odessa and drive by yourself, at your own pace, to the villages. To follow such advice you would need an International Driver's License, obtainable at AAA in Canada or the U.S. If you do not feel comfortable with the idea of driving in the Soviet Union, it is possible to rent a car with driver as we did. If your command of the language is not sufficient, by all means pay the extra cost of hiring a translator-guide to accompany you. Finally, unless Intourist policy changes, those planning extended research in any of the villages near Odessa will be required to return each night to an Intourist-arranged hotel in Odessa.

Approaching Worms (Vinogradnoye) on our way to Rohrbach.

12

THE DUNDEE, KANSAS, COLONY

Marjorie Andrasek Shortly after the completion of the Santa Fe

Railway through Kansas in 1872, the railroad company, through its immigrant bureau, advertised extensively throughout all sections of Europe—including Russia—that it had land for sale for those seeking new homes. The railroad company often arranged transportation for the emigrants from Russia to their destination in America. Agents were stationed in New York to meet and guide the new immigrants to their new homes in Kansas. By these means, a large portion of the ancestors of the present population of Barton County was induced to settle here. They improved these lands to the present state of productiveness and became factors in making this country what it is today.

This particular group of Mennonites arrived in Kansas in the fall of 1874 and wintered in Pawnee Rock. The majority of them had lived in small communities or villages in Russia. They had been engaged in weaving, lumber sawing, and farming. In their villages in Russia, they had found it necessary to form a compact body with a responsible head. At first, they attempted the same manner of organization in Barton County in a colony they settled 1 mile east of the present town of Dundee, Kansas, in the spring of 1875. Although the original plans called for twenty families, only fifteen families came under the agreement and settled in this colony. They entered the whole of section 16 under the Homestead Act, and they bought the whole of section 9 from the Santa Fe Railway Company on payments that covered eleven years. Both sections were divided originally into twenty equal parts. This gave to each family a tract of 32 acres on each section, or 64 acres in all.

On section 16 they built houses out of lumber and made their gardens. On section 9 they planted their crops. The fifteen cottages formed a village. The colony at Dundee was fashioned after the colonies of Russia. Their homes were built in a straight line and placed an equal distance apart. The only house out of line was the house of the leader or Schultz of the colony. His residence served as a council house.

The church was built on section 17 in 1875. It was built of limestone hauled in by ox teams from a stone quarry at Olmitz, Kansas, 20 miles away. My grandparents, Christian Schultz and Helena Rudiger, were the first couple to be married in this church. The stone church remained for many years after the colony broke up. It was

no longer in use but stood as a memorial until destroyed by a tornado on May 4, 1950. I remember how sad Mother and Dad were about the destruction of the church. They often recalled special memories about it. They remembered walking with other young people to this church for the Singstunde, or "singing hour," on Sunday afternoons. After the church was completed, a cemetery was laid out about a quarter mile southwest of the church. My grandmother, Lizzie Rudiger, my grandparents, Christian and Helena Schultz, and my parents, Sam and Eva Boese, are all buried in this cemetery—as are many other relatives. Abraham Seibert was the first pastor of this Mennonite congregation. He was not a resident of the village but lived with his parents about 2 miles southeast of the settlement. The church was also used for German classes once they were started.

Interior of the stone church, built in 1875, facing east

Those who made up the village were the families of Cornelius D. Unruh, Cornelius Thomas, Henry Seibert, Christian C. Schultz, Mrs. Lizzie Rudiger, Andrew P. Unruh, Andrew A. Seibert, Mrs. Susan Unruh, Benjamin P. Smith, Jacob Seibert, Benjamin Unruh, Andrew B. Unruh, Peter Unruh, Cornelius P. Unruh, and Peter H. Dirks. Henry B. Unruh also purchased his first home from this colony, but he is not included among the original settlers as he was not a resident until March 1876.

One settler very important to this colony was Christian C. Schultz. When he first arrived in America in 1874, he worked in a wagon factory in Latonia, Ohio. The next year he came to the

13

colony in Barton County, Kansas, to join his former neighbors from the area of Karolswalde, Volhynia. He bought a quarter section of land for the use of this colony. (We believe this was the land in section 17 on which the church was built.) He helped others not as fortunate as he with the financing of their homes. It is said that Christian's house was the best built of all in this colony. He helped build the stone church in 1876. On August 5 of that year, Christian was married in this church to Helena Rudiger, the eldest child of the widow, Mrs. Lizzie Rudiger. Christian and Helena lived in this colony for one year, then they homesteaded a farm 5 miles north of Pawnee Rock, Kansas. Here their fourteen children were born, one of which was Eva, my mother.

This photograph of Christian Schultz, age 69, and his two youngest daughters, Martha Schultz Koehn, age 18 (left) and Lena Schultz Unruh, age 20, was taken in 1911.

The last house to remain standing in this colony was that of the widow, Mrs. Lizzie Rudiger. My grandfather, Christian C. Schultz, helped build it for his future mother-in-law and her children. The house was built in the spring of 1875 on the north side of the Santa Fe Railway. It was built of drilled and pegged lumber. The Santa Fe Railway shipped the lumber for this house—as well as for all the immigrants' homes in this colony—from Michigan to Dundee free of freight charges. The approximate cost of the lumber for Great-grandmother Elizabeth's house was $40.35. The cost of the lumber for her beds, table, benches, fuel box, and shelves was $15.65 per 1000 feet. The house had dirt floors at first, and later wooden floors were put in. It was patterned after the Russian homes which had their house, fuel and storage shed, and barn under one roof. The attic in Great-grandmother's house was used for storing grain, which was carried in sacks up a ladder. Great-grandmother's sons also slept in the attic.

The home of Elizabeth Rudiger after it had been moved to land south of the tracks. A built-on cellar was added with a "walk-in" door from inside the house.

Later the house was moved to the south side of the track where Mrs. Rudiger had purchased 80 acres for $364.00. In 1969 the house was sold and moved to Pawnee Rock, Kansas, where it still stands today as a museum.

The original intentions of the Dundee colony were never carried out. The scheme was found impractical in the country after a trial period of three or four years. Because their holdings were independent of their village agreement, families one by one sold their first little homes and bought larger and better farms in other localities of the county. They are now classed among Barton County's most substantial and best citizens.

14

THE YOUNGEST CHILD* Hertha Karasek-Strzygowski Translated

by Sally Tieszen Hieb No, it really wasn't a simple matter to sketch the

people in this village. The smaller children, who were left to themselves all day, were timid and easily frightened. The older ones had to be in school or faraway in the pasture tending the cattle. The ladies and the younger women would very gladly have posed for me to sketch them, but they worked in the collective [farm] from early morning till late in the evening. During the short noon break, the children had to be cared for, and their only cow had to be milked. They didn't return home till late in the evening, dead tired, and even then they had to tend to unfinished housework. Now, during the harvest season, there was seldom a day free from work, which they urgently needed for the small garden surrounding their house. They wanted to cultivate and harvest as much as possible in order to provide this very necessary subsidy to their meager living. The old women weren't required to work at the collective anymore, but they labored steadfastly around the house with the energy of their past peasants' life, or they performed light work in their home for the collective in order to earn a little money for them-selves. They thought that sitting still for an hour and doing nothing during the middle of a workday was being presumptuous and the work of the devil. On the other hand, Sunday had strict regulations: worship service, hours of devotion, singing, and reading the Bible filled the day. Nonetheless, I succeeded in persuading the people to sit and pose during the scant free time they had. Slowly and steadily my portfolio filled.

There were always guests in Mother Fenske's kitchen these days, women and young girls from the neighborhood. The first ones arrived at the break of day; they were already sitting in the kitchen between four and four-thirty. From my bed in the next room, I could overhear what they were talking about to hard-of-hearing Mother Fenske and how she had to tell them just exactly what "her artist" had accomplished. The women who had watched while I sketched said, "She draws everything exactly as it is—the hair, the

*This is the twelfth chapter of Wolhynisches Tagebuch to appear in translation in the AHSGR Journal. The original book, in German, may be borrowed from the AHSGR archives through the interlibrary loan facilities of your local public or college library.

eyes, the moustache of Old Wenzler—and one can easily see that he is a good man and that God has laid many burdens on him." "And in Old Steffen," said one of the other ladies, "one can see that he cannot hear. And because she sketches everyone so precisely, then everything she tells us about Germany must also be exactly so." But then when one of them said, "She is just like we are, she speaks like we do, I believe she must be from Volhynia," then my heart beat with joy, because I now knew that they thought of me as one of them. They couldn't have expressed it more plainly or impressively.

The women also came often during their short noon break and sat in a row on the long bench in front of the large, sky-blue stove, like swallows on a wire. They chewed and spit out their sunflower seeds in an amazing rhythm. Their bright eyes beneath their white head scarves looked at me confidently and expectantly. Every day I saw the same thing when I came with my portfolio; a childlike enchantment lit up their faces. Naturally, I always had to start with the first page before I dared show the last, unseen sketch. Of course, they knew exactly what was on each page. I would not have dared to skip a single one. They always discovered something new in the expressions of the familiar faces of their friends and neighbors which had escaped them before. They critiqued and compared until one or the other of the women would say with a deep sigh, "Such pictures! If only we could have them of our husbands and brothers."

One day Father Wenzler, too, stood at the door with his gnarled walking stick in his hand, his quilted vest buttoned high, and his boots covered with white dust. Hurriedly, almost sternly, he demanded to see my "sketched photographs," as if it were his duty as village elder to watch carefully over what this artist was doing in his village. He tapped the floor with his stick domineeringly and impatiently, as if he had to have the pages in hand more quickly. He was always in a hurry on his daily rounds.

With a furrowed brow and a tightly compressed mouth, he looked at the sketches thoroughly, one after the other, from top to bottom—and naturally also the back side—as one would observe a cow from all angles to determine whether everything was in order. He was dead serious about it. It was only when he saw his own portrait that a faint smile came over his

15

16

wrinkled face. Then immediately a very stern inquiry followed. "Soon you will have sketched all the old ones and also the oldest one. All that is missing now is the youngest one."

The youngest! Dear God, to be able to sketch a child! After all these faces stamped with pain, after all of these sorrow-laden eyes, to draw a carefree, small child with a dreamy, delicate expression imprinted on its face, and a smile, light and untroubled! How relaxing to be able to sketch such a little, innocent human being!

Now I suddenly felt how much my work here had torn at my heart and how much I had empathized with them from their sketchy narrations in all their misery and distress, how aware I had become of each smallest, harsh line of their faces. "Yes, I would like to sketch the youngest," I exclaimed ardently. "The youngest one! An infant!"

"An infant!" It sounded almost harsh from the lips of the old one. "We don't have such a one in all of our village." Suddenly his face seemed to turn to stone, every line as if chiseled with a knife. He pointed through the open door with his walking stick at a small house somewhat apart. "Over there is where our youngest lives! Liskes' Elfriede! Four years old!"

His voice was very stern. One felt that he almost took it as a disgrace that there were no longer any infants in the village, no longer any colonist children? Don't they signify happiness, wealth, and blessings? They are gifts from the hand of God which one was to guide with strictness and kindness in order to please God and man. In earlier times it was taken for granted that there were ten, twelve, or more children, and all were provided for, and their future was secured.

Oh, what a joy it was at that time, such a growing, healthy, overflowing village which grew far out into the surrounding countryside! There was never a lack of joyous children's laughter, of busy hands. The old people never lived in want or solitude.

At the time of the First World War, wasn't there enough misery when they were deported and so many children died from fatigue, starvation, and typhoid fever enroute to the distant east? At that time, however, one knew that many more children would be born, and that was a consolation in their sorrow. But now all hope was in vain. Indeed, of all the inevitable grief which they had already endured, this was now the most difficult affliction which God the Lord had sent

them—sent them and all the villages without men throughout all Volhynia.

Toward evening, a wisp of smoke climbed over Frau Liske's house, straight as a candle into the fading, clear-as-glass autumn sky. "Well, you can go to see her now," said Mother Fenske. "She is at home. Oh, she keeps everything nice, the house, the furniture, the poultry, and the garden; everything is meticulous. All this for her husband. She is the only one who still believes that he will return." She said this almost compassionately.

The little, whitewashed house stood there almost like a little island of tranquility, completely surrounded by tall sunflowers, dahlias, and asters. A new, young rose bush, the first I had seen in this village, sent forth tendrils in front of one of the polished windows.

The young woman with the pretty, suntanned face, standing at the draw well, looked almost girlish. She was happy that I was finally coming to her too. With what pride she showed me the small house; the room, with the luxuriantly looking potted flowers at the window, with sparse but clean furniture. On the table was a red-embroidered linen cloth which gave the un-pretentious room an almost festive character. A dark, painted chest stood against the wall. "Old Steffen built this for our wedding," said Frau Liske, and she lifted the heavy lid. There lay her entire wealth, clean and delicately kept. One piece after another was shown to me: new, coarse linen hand towels, a small bolt of linen. "Everything was woven by Frau Bonn on her old weaver's loom." Carefully wrapped in a piece of cloth were several snow-white balls of wool from her own sheep. A flowered lady's dress "From the time when my husband was still here," a warm, little dress of Elfriede's, and at the bottom, covered with a clean cloth, were infants' shirts, a tiny, pink bonnet, a few small jackets, and next to that, a carefully folded man's white shirt, a woolen shawl, a few new, heavy woolen men's socks, and a pair of dark trousers. Indeed, it really seemed as if everything stood in readiness to welcome home the distant, missing husband.

In the kitchen was a monstrosity of a stove such as the peasants in this village without men built. This particular one was washed in a lustrous light green with many areas built into it and many protuberances. It looked like an ancient fortress. A little girl, wrapped in a large, white shawl, sat on a bench in front of it. Light blond strands of hair fell in her face to her overly serious blue eyes.

17

A stove typical of the type used by the peasants in Volhynia. Note the many nooks and shelves.

So this was Elfriede, the youngest child in the village. Her mother nodded to her encouragingly and stroked her slender shoulders with a restrained, tender gesture. "She is four years old now and has never known her father," the woman next to me said quietly as her almost happy face took on a grave and helpless expression. "In 1937 they deported him, shortly before Christmas. And now we wait and wait, day after day. But no one knows when he will come." It was as though her thoughts circled constantly around this grief and clung desperately on a small hope.

At that time they worried for weeks and listened in the cold winter to hear whether the auto would come which would break into the village like a wolf and take out their men. Until one day in the severest winter it actually happened, and the last fifteen men were carried away. "We couldn't say a word that night because of our pain and sorrow," the young woman next to me said quietly. "Two months later this child was born, a gift from God and a comfort in sorrow. Oh, how one would have liked to have had more children."

It was not the first time that I had been aware of how much these young women without men longed to have additional children. I almost had the impression that this yearning was greater and more natural than the longing for the missing men whose picture slowly faded. Indeed,

these women themselves had grown up with a multitude of brothers and sisters, eight or ten were average. That meant an active life in the house of one's parents. Everything was planned together—work, pleasure, and sorrow were experienced together. No one had known such lonely hours as little Elfriede had to bear day after day, And every year again a little baby brother or sister, which needed to be tended, lay in the cradle. The half-grown girls already learned then to lend a motherly hand and so grew into their future, early motherhood naturally. But that was now all wrenched away from them, and to many young women it seemed as though life had lost its true meaning and value.

However, it had never occurred to such a woman to look at another man without positive verification of her widowhood. For that matter, where was there a suitable man for her anyway? She could have run through all the German villages in a wide area. It would have been futile. They were without men just as was her village.

There seldom was a woman who decided to marry a Ukrainian. That was against the colonists' precepts. Of course it wasn't the same anymore as the oldest ones reported it had been in the earlier times, that when a maiden transgressed against this strict colonist rule and had anything to do with a stranger or married him, she was disowned by the family and the com-munity. In the most intimate circles one heard cruel, harsh stories secretly repeated by the older ones in order to warn the youth, even though these customs had been loosened since—and particularly at the time of—the "New Order."

So the women remained lonely and waited. In-deed, God had laid a difficult destiny on them, but they had to bear it and had to bury all their yearning for additional children.

I sketched little Elfriede, the youngest child in the village, the next day. She sat there on the stove bench again, waiting for her mother, tightly wrapped in her woolen shawl. A fainthearted smile brightened her small face for just a moment. Then she again sat quietly and frightened, holding the apple which I had brought her tightly in her small hand. I told her simple, short stories and several jokes, but she did not lose the very serious expression in her large eyes. No doubt, too much loneliness had already impressed itself in her little child's heart; she was too conscious of her mother's distress. Perhaps already at the time when she was still in her mothers womb....

18

BUKOVINA-GERMAN PIONEERS IN URBAN AMERICA*

Sophie A. Welisch The New World has acted as a magnet, attracting

Europeans since the time of its discovery by Christopher Columbus in 1492. People abandoned the Old World for many reasons, among them to escape religious and political oppression, to seek adventure, and most importantly, to improve their economic status. Until the mid-nineteenth century the British Isles, the German states, and Scandinavia provided the majority of America's newcomers. But with the political and economic upheavals in southern and eastern Europe in the last decades of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the focus of immigra-tion shifted to Italy, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, with 2,145,266 coming between 1901 and 1910 from the latter country alone.

Impoverished, unskilled, and functionally illiterate, most of these so-called New Immigrants arrived after the closing of the frontier in 1890, that is, after the free land available under the Homestead Act had already been settled. Too poor to buy land, they congregated in America's cities, creating ethnic ghettos the existence of which gave established Americans the impression that these last newcomers were truly inassimilable and should be barred from entry into the country. Subjected to bigotry, discrimination, and economic exploitation, it has been estimated that a full third of the New Immigrants eventually returned to their homeland.

Among this latter group we find the first Bukovina Germans, whose total number-included in the overall statistics for Austria-Hungary—cannot be determined with any degree of accuracy. This essay attempts to describe the three waves of emigration from Bukovina, the conditions they encountered, and their response to their new environment. The author, the daughter of Bukovina Germans who came to America in 1923, has had first-hand acquaintance with several hundred Landsleute (compatriots) and their descendants over the past five decades. With few exceptions this narrative is limited to the men and women from the villages of Bori, Gurahumora, and Paltinossa—people

* Translated into German and published as "Deutschbohmische Pioniere in den Stadten Amerikas," in Bori, Karlsberg und andere deutschbohmische Siedlungen in der Bukowina, ed. by Rudolf Wagner (Munich, 1982), pp. 41-59; reprinted in Der Sudostdeutsche (Munich), Apr. 15, 1982, pp. 3, 7 and May 15, 1982, pp. 3,5.

within the author's range of contact—and in no way claims to be an exhaustive or definitive study of the subject.

Bukovina-German immigration can be divided into three periods: 1860-1914, 1920-1924, and 1947-1957, coinciding with historic events of global significance. During the first period, immigration to the United States was unrestricted except to those of Chinese ancestry and those deemed criminals, derelicts, and prostitutes, who had been excluded by congressional legislation as early as 1882. All others who could afford the passage could freely enter the country where, indeed, they were welcomed as a source of cheap labor. In New York Harbor newcomers passed the world-famous Statue of Liberty which offered its own special welcome in the form of an inscription on its base:

Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breath free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore, Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me; I lift my lamp beside the golden door.

After a superficial medical examination at Ellis Island, the immigrants were set ashore on the streets of New York to fend for themselves. But once inside the golden door, difficult conditions awaited them, especially if they had no friends or relatives to receive them. After leaving Ellis Island they wandered through the streets of New York hoping to find someone who could speak their language, and more often than not, they spent their first few nights sleeping out-of-doors. Sometimes potential employers met ships at the docks and offered the immigrants jobs and temporary shelter.

We find anywhere from one to seven or eight members of the following families arriving from southern Bukovina before the First World War: Belina, Boca, Brandl, Braun, Croiter, Czicek, Davidowitsch, Ducke, Dumka, Erbert, Fuchs, Gall, Haas, Habatsch, Harti, Hellinger, Hilgarth, Hoffmann, Horn, Joachimsfchaler, Kisslinger, Klostermann, Kraus, Kuczyncki, Lakota, Lang, Lohmer, Loy, Marczan, Moritz, Neumayer, Nowecki, Pelczar, Reichhardt, Sawilla, Schaffhauser, Schindelar, Schmidt, Seidi, Spitzschuhe, Stranacher, Sturza, Swoboda, VoUmuth, Wamsiedler, Winzinger, Wlodkowski, Zigelli, and Zim-

19

mermann. Drawn to America by economic need, most were either unmarried men and women in their late teens or early twenties or married men who had left their families behind until they became established. Aside from their inability to speak English, their job skills found little application in the urban economies of New York, Detroit, or Chicago. Coming from an agrarian, pre-capitalistic society, most had been farmers with a side profession such as forestry, black-smithing, shoemaking, barrel binding, or carpentry. Bukovina's women were even less prepared vocationally than its men. With none but domestic skills, they took employment as housekeepers, seamstresses, cooks, waitresses, or factory workers, sharing the lowest ranks of the American labor market with thousands of other immigrants of their generation. They were poor, but they did not know it. Josefa Braun of Gurahumora, now ninety-two years of age, recalled that in 1912 she earned three dollars per week, of which one dollar went for rent, the second for food, and the third she spent as she saw fit, for which she considered herself the most fortunate of women. Joseta Kraus, writing to her mother shortly after her arrival and working as a counter girl in her brother-in-law's bakery commented, "Mother, you can't believe how good things are here. In Paltinossa we had Krapfen (doughnuts) only twice a year; here I can eat them every day."

Before the First World War, no social services for the sick or the indigent existed. If one wanted to eat, one had to work. America's laissez-faire philosophy held that poverty was an evil of one's own making, so one had best see to one's own needs. But work was nothing new to the Bukovina Germans, most of whom willingly accepted any available employment, often with German-speaking entrepreneurs who had arrived earlier and were already established. They had to learn new trades and crafts, with some becoming bakers, stone masons, machinists, seamen, butchers, and tailors. Twelve hours per day, six or seven days per week, at $12 per week were typical working conditions at the turn of the century. At this time beef sold for 10 cents a pound, chicken for 7 cents a pound, sausage for 12 1/2 cents a pound. One could get bread for 2 cents a pound and a quart of milk for 6 cents, a pair of children's shoes for 50 cents and adult shoes for twice that amount.

About one-fourth of one's monthly income had to be set aside for housing. For $4 per week one might rent two small rooms. In some cases four to five families had to share a common toilet and sink in the hall of the building. As relatives

joined family members already here, they moved in with them, adding to further overcrowding. Landsleute usually congregated in similar sections of the city, sometimes in the same building, sharing their rooms with newcomers as needed.

Saving a little from their salaries, many sent money to their relatives in Bukovina, awaiting the time when they had sufficient funds to return to their homeland to buy that extra acreage. The influx of money back home served as a motivation for others to immigrate to America. In addition, letters—typical of travel literature throughout the ages—often exaggerated the conveniences and glamorized the lifestyle, so some who came in response to rags-to-riches stories faced considerable disappointment. The author is reminded of Stefanie C. who arrived in America as a young woman of seventeen years. Shortly after disembarking in New York, she asked her relatives for a rake. When asked why she thought she needed a rake in the city, she answered candidly, "Why to rake up the dollars from the street." Instead of a rake she settled for a mop and worked for the next forty years as a cleaning woman in a large insurance company.

While economic conditions gradually improved, social adjustments still remained difficult. Coming from small villages in which everyone knew and cared for one another, where a high degree of intermarriage and familial interrelationship existed, and where people readily became involved in other people's business, the immigrants now found themselves in an impersonal city where one could live for years without speaking to or even knowing the names of one's neighbors. Some returned to Bukovina either to escape exploitative labor conditions in a cheerless city or because they had saved enough money, or simply because of homesickness. Rosina Kisslinger departed the United States on three dif-ferent occasions, each time disposing of all her possessions and intending to stay in Gurahumora. But it was not the same as she had remembered it. Used to urban conveniences, she would strike a match and walk to the stove, looking for the gas jet, and then realize that before making a fire, she first had to go outdoors to chop wood. Another time she took a drinking glass and started looking around for a faucet, forgetting that water had to be drawn from the neighbor's well. These people became true displaced persons, no longer comfortable in their native villages and not at home in the New World.

The American immigrant experience proved to be a sobering one in other ways as well. Those

20

whose families had been more affluent in Bukovina or who had attended Volkschule (elementary school) for an extra year or two initially thought of themselves as a bit superior to their less fortunate Landsleute. But what one's family owned in the old country did one little good in America. All started on a reasonably equal basis and moved ahead by their wits and by the sweat of their brow. Moreover, the American social structure, considerably freer and less rigid than that of Europe, provided daily lessons in equality. When a young immigrant from Bori saw a Catholic priest kicking a football around with some boys on the street and later recognized his daughter's fourth-grade teacher working with a pick and shovel on a highway construction job during his summer vacation, he experienced a culture shock which remained with him all his life.

Another area of adjustment concerned religious life. Some New York churches, including Most Holy Redeemer at 131 East Third Street and St. Nicholas Church at Second Street

and Avenue A, under the care of the beloved Father John Nageleisen, offered religious services in German until the late 1920s. But the American Catholic Church, dominated by an entrenched Irish hierarchy, by and large seemed insensitive to the needs of the immigrants and often seemed overly concerned with financial issues. In Bukovina the state subsidized the clergy whereas in the United States a constitutional separation of church and state forced the former to be entirely self-supporting. Johann W. of Gurahumora learned this on his very first Sunday in New York when he was turned away from the church door for lack of a 10-cent admission charge. The commercialization of Christmas and Easter, the de-emphasis on processions and on devotion to the Blessed Mother, and the non-observance of saints' days and of fasting changed at least the external aspects of the religion which traditionally had given the Bukovina Germans spiritual strength. Not sur-prisingly, this led to a degree of alienation and in some cases to a total break with the church.

The funeral cortege of Wenzel Kraus in Paltinossa, Bukovina (1937), the Reverend Sigmund Muck officiating. Almost the entire ethnic community turned out for occasions such as funerals. On the day of interment, the funeral party proceeded on foot from the home, where the deceased had been waked, to the church for a final religious service, and finally to the place of burial. Standard bearers with church flags and crucifixes led the way.

21

Before World War I New York had a thriving German district on the Lower East Side with restaurants, shops, newspapers, a theater, and later a movie house. But long hours of work left little time for recreation. By far the favorite pastime became spending a day at the beach at Pelham Bay, accessible for only a 5-cent subway fare. Sunday after Sunday our Landsleute met at Pelham Bay for swimming, football, picnicking—often their only relief from the factories and sweatshops.

Not used to the high level of consumerism in a capitalistic system, the Bukovina Germans invariably commented on the wastefulness of American society. Perfectly good clothing, furniture, and appliances were simply discarded, daily, generating tons of garbage per city block. Occasionally our Landsleute sifted through what others had thrown away and took what they considered functional. Moreover, they often found it impossible to part with their own worn-out items, even long after they ceased being ser-viceable. The author recalls one gentleman who throughout his fifty-seven years* residence in America owned only two overcoats. But frugality, thrift, and self-denial brought results. In time the immigrants became established, bought their own homes, and provided their children with a better education than they themselves had acquired. Many a long-established American wondered how these newcomers managed to get ahead, considering they usually held low-paying jobs and had only marginal command of the state language.

The children of Bukovina Germans born in the United States or coming with their parents as infants quickly learned English by exposure to America's many institutions for assimilation, especially its schools. By their tenth or eleventh year, they usually had lost their fluency in German. When parents spoke German, children responded in English; in time the parents shifted to English also. Causes for the rapid loss of German identity are several: first, parents, often bordering on illiteracy and speaking a dialect laced with Romanian idioms, lacked the educational background to give their children an in-depth linguistic experience; secondly, the anti-Germanism unleashed by the world wars made it desirable to avoid drawing attention to oneself by speaking the language of America's foe; in addition, if the children were to succeed, they needed a good command of English; and finally, as a small dispersed minority in a sea of English-language speakers, assimilation at best remained only a matter of time.

With the outbreak of World War I, immigration from Bukovina temporarily ceased, not to resume again until 1920. By the terms of the Treaty of St. Germain, signed September 10, 1919, Bukovina became an integral province of the Kingdom of Romania, with its German population acquiring the status of an ethnic minority. Subjected to Romanization, to discrimination in land reform programs, employment and education, and with its young men facing twenty-one months of compulsory military service under what they viewed as barbarous conditions, a second wave of Bukovina Germans left for the New World in search of a better life. But economic motives no doubt outweighed political considerations in opting for emigration. A population explosion, begun in the late nineteenth century and continuing into the first decades of the twentieth, threatened to proletarianize the peasantry. Families with less than a half-dozen children were the exception. Unable to assure the livelihood of their many offspring by further subdividing their already meager land holdings, parents urged their more adventurous progeny to seek their fortunes in America. So, for example, we find immigrating to the New World ten of the twelve children of Marie and Wenzel Neumayer (Gurahumora); five of the ten children of Theresia and Josef Braun (Gurahumora); three of the seven children of Marie and Leon Loy (Paltinossa); three of the seven children of Theresia and Wenzel Kraus (Paltinossa); five of the eight children of Marie and Ignatz Schaffhauser (Bori); and seven of the nine children of Karolina and Wenzel Hilgarth (Bori).

Daughters for whom dowries had to be provided and who upon marriage joined the extended family of their husband were often the ones encouraged to leave. Asked why she immigrated to the United States, Anna B. quite frankly replied: "I was superfluous at home." Theresia Kraus considered her four daughters as "stones around her neck," while Susanna Loy noted:

Since we were considered better off than most, the community expected my mother to provide me with a substantial dowry; but as a recent widow with five young sons, she felt it would take all her resources to see that they learned a trade and had sufficient land to eke out a living. In order to insure that my brothers got my share of our father's legacy, she suggested I go to America.

22

Between 1920 and 1924 we find the arrival of younger members of families already here as well as some new ones: Balog, Bedner, Brandl, Braun, Burkowski, Czicek, Ducke, Dumka, Gall, Haas, Habatsch, Hassi, Hilgarth, Horn, Kisslinger, Kraus, Lang, Loy, Miller, Moldowan, Neumayer, Niedzielski, Nowecki, Pelczar, Pilsner, Schafarczek, Schaffhauser, Schindelar, Stauber, Tanda, Tomaschefski, Turczany, Winzinger, and Welisch. As with the earlier immigration, most came as unmarried young men and women, poorly skilled for urban pursuits, but ambitious and willing to learn. Although impoverished, usually coming with a small wicker suitcase, the clothes on their back, and indebted for their travel expenses to some relative already in the States, no Bukovina German, to the author's knowledge, ever turned to criminal activities or to vagrancy. On the contrary, within a short time they found suitable employment, sometimes even acquiring a small business of their own (bakery, barber shop, dress factory, grocery store, cement block factory), bought homes, and

settled down as stable taxpayers and law-abiding citizens.

An exception to the Bukovina Germans' usual compliance with the law and respect for authority came with their response to the Volstead Act (1919). This federal legislation made provisions for the enforcement of the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, prohibiting the sale of intoxicating beverages of more than 0.5 percent of alcohol per volume. Prohibition had long been a political issue, and with the First World War the movement gained rapid momentum. Wartime conser-vation policies necessitated limiting liquor output in addition to which the closing of the breweries, owned and operated by Germans (Schlitz, Anheuser-Busch, Budweiser, Pabst) became a patriotic duty. Our Landsleute responded by frequenting "speakeasies," that is, places where intoxicating beverages were sold without a license, or by distilling their own alcohol. 'Josefa Schaffhauser, a great-grandmother of seventy-seven years, points with

Bakery of Karl Schaffhauser (extreme right) in Brooklyn, NY, ca. 1923. Karl immigrated to the United States from Bori, Bukovina, in 1912. By the eve of the First World War, his economic circumstances were so strained that he was on the verge of borrowing money to return to his homeland. Yet by the 1920s he was not only an experienced baker but also owned and operated his own bakery with adjacent restaurant. Typical of small entrepreneurs of the period, Karl hired members of his own family to assist him in his business. With the onset of the Great Depression, he was forced to declare bankruptcy and died shortly thereafter at the age of 39.

23

pride to a still her husband used during Prohibition to make whiskey from plums, grapes, or cherries. Nor has the still had time to accumulate rust since the repeal of the Volstead Act in 1933. Son Karl makes frequent use of it, Tante Josefa explained as she handed the author a jigger of 100 proof Kirschbranntwein (cherry brandy) to sample. In the Detroit area some Bukovina Germans indulged in isolated instances of "bootlegging" alcohol across the Canadian border; this involved great risk to life and limb, not so much from the intervention of the law as from organized crime.

With America's return to isolationism after World War I and in response to nativist pressure groups, the United States government moved to curtail immigration. In 1921 Congress introduced a quota system, restricting immigration to 3 percent of those of a particular ethnic group here in 1910, for an overall total of 367,803 annually. Considering this number still too generous, Congress in 1924 further reduced immigration to 2 percent of those nationalities living in the United States in 1890. This legislation favored populations from northern and western Europe and drastically limited those from the south and east. Immigration from Bukovina, included in the Romanian quota of 377 per year, came to a virtual standstill overnight. But Canada, with extensive uninhabited lands, still welcomed settlers. Some Bukovina Germans opted for immigration to Canada after 1924, later entering the United States illegally somewhere along its poorly patrolled 3000-mile border. Those who had become American citizens and had returned to Bukovina after the war could reimmigrate freely and without difficulty at any time.