Kitaro Nishida Intelligibility and the Philosophy of Nothingness

Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x]...

-

Upload

juan-serey-aguilera -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x]...

-

8/9/2019 Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x] JIN BAEK -- Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

1/7

JIN BAEK

Pennsylvania State University

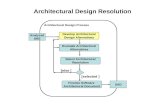

In order to reconcile the breach between the typologist and the populationist in contempo-

rary architecture, this article discusses Kitaro Nishidas philosophy of emptiness. The article first

introduces Asian artistic examples to illustrate the significance of emptiness in art. It then

discusses Nishidas emptiness as the ultimate foundation of reality from which being and nonbeing

coemerge. The article also summarizes three interrelated lessons from Nishidas emptiness pertain-

ing to architecture: the dialectic of opposites, the bodily subject of immersion, and the dialectic

between the ideal and the real. The article finally explicates these concepts by discussing Asian

and Western architectural examples.

Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of

Emptiness and Its Architectural

Significance

IntroductionIn the Atlas of Novel Tectonics, Jesse Reiser and

Nanako Umemoto discuss the error of the typol-

ogist and endorse the position called popula-

tionist. In deploying their argument, they quote

the contradistinction between the typologist and

the populationist defined by Ernst Mayer (1904

2005), a leading evolutionary biologist of the

twentieth century, who states that for the typol-

ogist the type (eidos) is real and the variation an

illusion, while for the populationist, the type (the

average) is an abstraction and only the variation is

real.1 Accordingly, for the typologist, whose

interest is in abstracted essence, tangible varia-

tions appear as mere degradations. In contrast, for

the populationist, the abstract universal eradicates

individual differences and falls far short from

the real.

Although intriguing, this argument recapitu-

lates the debate between idealism and realism in

Western thinking that dates from Greek philosophy.

Platos idealism, in which truth exists in a preexist-

ing universal, and Aristotles empiricism, in which

sense-perception leads to the recognition of the

universal, are echoed in the typologist and popu-

lationist arguments. The populationists may argue

that their position is more radical than Aristotles

empiricism. Despite the fact that Aristotle valued

the particular as the gate to the universal, he

bypassed it eventually in the process of appre-

hending what the entity is. Aristotle wrote that

though the act of sense-perception is of the

particular, its content is universalis man, for

example, not the man Callias.2 In contrast, the

populationist position maintains the side of the

individual by proliferating discrete or serialized

variations. Such variations are not simply copies of

the universal. Rather, they belong to a completely

new category, in which, according to Gilles Deleuze,

individual entities are like false claimants, built on

dissimilitude, implying a perversion, an essential

turning away from the universal.3 However, like

Platos idealism, this celebration of heterogeneity

by the populationist does not resolve the presumed

antagonistic relationship between the universal and

the particular.

In contrast, this article intends to elucidate

how the typologist and the populationist, and

idealism and realism, are interdependent, one being

the basis for the operation of the other. For this

purpose, it introduces the Asian philosophy of

emptiness by Kitaro Nishida (18701945), the

father of the Kyoto Philosophical School (Figures 1

and 2). The article first introduces Asian artistic

examples to illustrate the significance of emptiness

in art. It then discusses Nishidas emptiness as the

concrete universal from which being and nonbeing

coemerge. The article also summarizes three inter-

related lessons from Nishidas emptiness that

are relevant to architecture: the dialectic of oppo-

sites, the bodily subject of immersion, and the dia-

lectic between the ideal and the real.The article

finally explicates these concepts by discussing

the architectural theories and works of Aldo van

Eyck (19181999), Tadao Ando (1941), and Aldo

Rossi (19311997).

Emptiness in Asian ArtEmptiness operates as the foundational principle in

traditional genres of art in Asia such as Japanese

garden design and the sumie painting of the

Southern Sung School in China. According to

William LaFleur, a scholar in Japanese Religious

Studies, these genres espouse the philosophy of

emptiness in the form of the dialectic of opposites.

To verify his point, LaFleur brings ones attention to

the arrangement of contrasting qualities in the

Japanese garden such as the soft moss and the

hard stepping stones. For him, this type of

arrangement first reflects the Buddhist view that

things that are inanimate in Western classification

are considered to retain spirit. The artist of a

Japanese garden positions things of spiritual char-

acter in such a way that they create a coordinated

37 BAEK Journal of Architectural Education,

pp. 3743 2008 ACSA

-

8/9/2019 Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x] JIN BAEK -- Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

2/7

balance between forces. In this fashion, the garden

brings into special focus the underlying related-

nessof things, the mutuality which exists in spite ofdifferences between hard and soft, great and small,

and observer and observed.4

According to LaFleur, this philosophical ori-

entation is also found insumiepainting. First of all,

LaFleur cautions one not to see the large,

unpainted space in a sumie painting as corre-

sponding to Buddhist emptiness. For him, this

mistaken view originates from a facile mimeticism

but would also involve a fundamental misunder-

standing of the meaning of emptiness.5

The valueof the void is not that it makes palpable and

concrete something metaphysical called non-

being but that it operates to make possible a series

of relationships and reciprocities.6 Asumie paint-

ing thus presents a harmony not of formal

symmetry but of reciprocity between the void and,

for instance, a dark silhouette of a wagtail at the

bottom of the canvas (Figure 3).7 On these

grounds, LaFleur rejects any of the two mistaken

positionsone emphasizing being and the otheremphasizing nonbeingin favor of the reciprocity

of not being one without the other.8

EmptinessThe reciprocity between opposites that LaFleur

discusses in reference to Asian art is a facet of the

philosophy of emptiness expounded by the thinkers

of the Kyoto Philosophical School. Among the

thinkers, Nishida is the most towering figure. His

philosophy of emptiness can be traced to the

ancient Indian philosophy ofsunyata or emptiness.Later, Acharya Nagarjuna (c. 150250 CE), the

founder of the Madhyamaka School of Mahayana

Buddhism, introduced emptiness to Buddhism in

the process of solidifying Buddhisms key doctrines

such as no-self and dependent origination.9

Nishida revived this religious philosophy to con-

front the objective and materialistic perspectives of

modernity. Overcoming the idea of the universal as

the abstracted denominator of things, Nishida

articulated emptiness as the concrete universalfrom which the individual differences emerge in

their unmitigated particularity. This emptiness, the

ultimateeidos, was a topos in which beings emerge,

exist, and evaporate.

Emptiness is often understood as nonexis-

tence, a void that is symptomatic of a predominant

fixation on objects. In contrast, Nishidas emptiness

is neither nothing nor the suffocating void of lim-

itless expansion in which things are at best deso-

lately scattered. Rather, it is the ultimatefoundation of reality that transcends ideas of

being and non-being. Subsequently, what is

operating in emptiness is a double negation: the

negation of being, which leads to nonbeing, and

the negation of nonbeing. The second negation

does not amount to being, which would be the case

in formal logic. Instead, according to Nishida, it

leads to the awareness of a horizon where the

confrontation between being and nonbeing is

transcended in favor of their coemergence.10

Because of this dependence of being onnonbeing and eventually on emptiness, Nishida

endorses the principle of impermanence while

rejecting the self-sufficiency of being itself. The

impermanence of ones self should be understood

not as the deprivation of identity but as ones

openness and capacity to accept the other as ones

own self, the basis of deepest empathy. For Nishida,

the deepest form of empathy is devoid of condi-

tioned feelings and emotions; consequently, it is

open to fully accept what is offered by the world.11

Based on this preliminary examination of

Nishidas emptiness, the following three lessons can

be elicited.

The Dialectic of OppositesNishidas refutation of the self-sufficiency of

a being is relevant to the issue of identity. The

identity of a being is determined not by what is

believed to be existent within itself but by its

dialectical relationship with the opposite, like themoment in which one finds ones self to be the

being of warmth in reference to coldness envel-

oping and penetrating the body. What is seen as

internally present in an entity is existent in the first

instance because of the external presence of its

opposite. The entity and its opposite are inter-

twined through the principle of inverse corre-

spondence, a higher level of accord that emerges

1. Kitaro Nishida. (Courtesy of the Museum of Kitaro Nishidas

Philosophy.)

2. Tadao Ando, Museumof Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy, Unokemachiin Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan, 2001. (Photograph by Steven Rogers, courtesy of the

photographer.)

Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

Significance

38

-

8/9/2019 Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x] JIN BAEK -- Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

3/7

from the disposition of asymmetrical qualities.

According to David A. Dilworth, this symmetrical,

yet reversed, reciprocity is the logic of is and

yetis not and that of simultaneity, and bi-

conditionality, of opposites without their highersynthesis.12

One should not misunderstand this dialectical

logic as indicating a middle ground between the

two coemerging identities. This type of dialectic is

not dialectical (sublational) in a Platonic or

Hegelian sense; it does not postulate another level

of being or noematic determination.13 For exam-

ple, this logic does not mean to synthesize gray out

of white and black. This kind of synthesis merely

produces another static entity only to lose thecreative energy emanating from the juxtaposed, yet

inseparable, synthesis of the two opposites. In

contrast, in Nishidas logic, white and black are

intertwined with each other to augment their indi-

vidual efficacy.This logic formulates a contradictory

synthesis operating on a deeper level of intui-

tion that sees relatedness between contrasting

elements.14

The Bodily Subject of ImmersionIt is erroneous to think that Nishidas emptiness is

solely an issue of disembodied consciousness.

On the contrary, for Nishida, the self as empty

vessel is actualized through the sensing body.

Sensation is concerned not with measuring out-

side phenomena based on predetermined con-

cepts, ideas, and values but with unconditionally

accepting phenomena as ones own self. For

Nishida, this was a form of knowing superior to

reflective judgment, which he named the cogi-tation of cogitation and Ur-thinking.15 This

type of sensational immersion, when the capacity

of ones self to accept what the world offers rea-

ches a limit, is creative. In this context, Nishida

claimed that when the self of true immersion is in

operation, it falls within the matrix of the Created

to the Creating (tsukurareta mono kara tsukuru

mono e).16

In fact, the sensational immersion of the

pre-I, in which the I in confrontation with the

world has not yet emerged, is not an unreceptive,

static union with the environment but, according to

Nishida, already a higher form of activity.

17

In eachimmersion, the perceiver faces a test of capacity

in terms of being united with what the world offers

in abundance. The reciprocity between what the

perceiver can take in and what the world offers

activates movements of the body toward the cre-

ation of things into which the surplus is invested.

The work created in this fashion is not a represen-

tation of the concept of the author but, as Nishida

argued, an extension of the bodily subject that

accommodates the surplus that the sensing bodyalone cannot fully accept.18 Through its sensational

capacity and through its act of creation, the body

actively engages with the atmosphere of a setting

and as such actively knows it.

The Dialectic Between the Ideal andthe RealEmptiness as the profound phase of the I is

a concrete universal that allows the emergence of

the particular I in dynamic resonance with theenvironment. This twofold structure of the I

presents a unique relationship between the uni-

versal and the particular. Ones identity emerges

not through the intentionality of the ego but,

according to Nishida, through the self-delimitation

of the infinite and eternal emptiness into a finite

and temporal content. The nondifferentiation of

emptiness is articulated into the palpable sense

of the I in codependent origination with its

opposite.Nishidas concept of the universal that delimits

itself voluntarily into a temporal and finite content

is partly Hegelian because it includes the principle

of self-individuation. However, according to Masao

Abe (19152006), a member of the Kyoto Philo-

sophical School, because Hegels concrete universal

becomes Absolute Spirit, it absorbs the reality of

particular entities into its own all-encompassing

3. Mu-chi, Wagtail on a Withered Lotus. (Courtesy of MOA Museum

of Art, Atami, Japan.)

39 BAEK

-

8/9/2019 Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x] JIN BAEK -- Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

4/7

subjective-objective reality. In contrast, Nishidas

concrete universal does not have its own indepen-

dent reality apart from the particular entities in

which it manifests itself. Therefore, it is Absolute

Nothingness, a total lack of reality in and foritself.19

Thanks to this nature of the universal, the

ideal, such as eternity or infinity, is felt only through

the real, while the real emerges as the function of

self-individuation of the ideal. Accordingly, there is

no ideal unless there is the real, and there is no real

unless there is the ideal. Using Nishidas metaphor

of the infinite line and a finite line, the infinite line

that cannot be represented in any finite form by

definition is felt through the finite broken line, notbecause the broken line represents the infinite line

but because the former reciprocates with the latter

through the logic of inverse correspondence.20 In

this way, infinity and finitude are joined. Likewise,

the universal and the particular are joined through

this kind of reciprocity.

Architectural Lessons of EmptinessUp to now, this article has summarized three les-

sons from Nishidas emptiness: the dialectic ofopposites, the bodily subject of immersion, and the

dialectic between the ideal and the real. Next, it

explicates these lessons further by discussing

architectural theories and works of Aldo van Eyck,

Tadao Ando, and Aldo Rossi.

The Dialectic of Opposites in theArchitecture of Aldo van EyckIn architecture, the idea of twin-phenomena by

Aldo van Eyck is an example of the dialectic ofopposites. As a member of Team X, van Eyck sought

to transcend the categorical and monodimensional

comprehension of the human being in modernism.

In this process, van Eyck turned not to the cele-

bration of heterogeneous multiplicity but to a kind

of Nishidian dialectic, which he called twin-phe-

nomena. For example, the uniqueness of a circular

configuration comes from the fact that its rim

embodies the duality between the centrality of

looking inward to find the communal center and the

peripherality of looking outward until one finds the

distant horizon (Figure 4). It was neither about

the center nor about the horizon and neither aboutcommonality nor about individualistic heterogene-

ity but about their copresence.

Like the non-Hegelian dialectic of Nishida, the

zone of in-between such as the rim of the circle

does not neutralize differences but sustain their

simultaneous presence: inwardness versus out-

wardness, centrality versus peripherality, pro-

tected versus open, and public versus private.

According to van Eyck, this intermediary zone,

where opposites coexist, allows simultaneousawareness of what is significant on either side.

Moreover, an in-between place in this sense

provides the common ground where conflicting

polarities are reconciled and again become twin

phenomena. 21 In this regard, good architecture

does not impose a meaning by favoring one value

over the other between individuality and collectiv-

ity or between peripherality and centrality. Rather,

it lays out a platform on which the contrasting

values are copresent.

The Bodily Subject of Immersion in theArchitecture of Tadao AndoThe joining of differences to form a higher level of

accord is conducted through the perceiving body in

movement. The moving body immeasurably meas-

ures and comes to terms with the array of opposing

qualities. It actively knows a given setting not

through judgment but through immersion. It is this

body that, in the case of the Japanese garden, feels

the solid firmness of the stepping stone to integrate

it with the visual softness of the moss covering thelanterns. The visual and the tactile are reciprocal,

forming an ensemble not only for sensorial richness

but also for the trustworthiness of the vertical

posture.

In the phenomenal array of different qualities,

one is never able to experience them in an omni-

present fashion.The tactile firmness of the stone is

4. Aldo van Eyck, diagram on the twofold value of the circular configuration. (Reproduced fromAldo van Eycks, Works and compiled by Vincent

Ligtelijn, B asel: Birkhauser Verlag, 19 99.)

Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

Significance

40

-

8/9/2019 Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x] JIN BAEK -- Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

5/7

felt first, and then, the visual perception of the

softness of the moss takes place. It is the body that

synthesizes these qualities offered at different

moments in a dialectical fashion. This actively

knowing body renews the significance of memory.

22

It joins what has been with what is now, defining

memory not as the depository of past events but as

the active metaphorical faculty in which the present

is coalesced with the past. Memory is an intuition

that sees relatedness in discrete qualities, related-

ness configuring itself not because of common

attributes but in spite of differences. This meta-

phorical search of memory overturns the boundary

of the conventional in its constant demand to

embrace opposites, incompatibles, and even abso-lute contradictions.

Tadao Andos Church of the Light (1989) in

Ibaraki, Japan, serves as a religious example for the

operation of the actively knowing body. The

molding of darkness, one of the primary themes in

Andos architecture, functions as the precondition

for ones encounter with the light coming through

the cross-form opening at the end of the sanctuary.

Before this presence of the dramatic cross filled

with glowing light, one, who is enveloped in dark-ness, does not measure what is offered but is pre-

reflectively attracted to it (Figures 5 and 6). Surely,

the visitor has come into the chapel in order to

encounter the cross. In this uncanny drawing of the

visitor toward the cross, however, such seeming

activity comes to be conjoined with the passivity in

which he or she is encountered by the cross, as if

the cross had been waiting for the visitor. The

linear axis of the central aisle now overcomes its

role as a habituated compositional technique.It starts to coincide with and guide the move-

ment of the actively knowing body that faces

things axially. Here, almost without ones know-

ing, there occurs a movement from darkness

to light.

In accepting unconditionally what a setting

offers, the body actualizes ones emptiness, the

deepest phase of self. This body is the very agent

for an experience that is ineffable, numinous, and

awesome. Such an experience even appears as if it

were spelled by magic. Its inexplicable depth

emerges precisely from the renunciation of the

hegemonic subjectivity that would analyze the

setting with pregiven ideas, values, and criteria.

At the moment when incomprehensible types of

phenomena such as extreme atrocity, love, andreligious experiences are presented, ego has no

choice but to disintegrate because of its incapa-

bility to apprehend them in an emphatic union. As

argued previously, for Nishida, the truest form of

emphatic union takes place only when one opens

up his or her selfhood to fully accept what the

setting offers. This acceptance is anything but

a passive submission; behind this acceptance is

the highest form of will to renounce ones ego, not

the will to impose ones egoistic value upon the

world.

The Dialectic Between the Ideal and theReal in Aldo Rossis Theory of TypeNishidas dialectic between the ideal and the real

illuminates the significance of each architecturalcreation as a particular expression of a shared ideal.

The architect is not a heroic figure who imposes

values upon a setting but a monad that expresses

the ideal. In this articulation of the ideal of the

collective human dwelling, the illusion of a manip-

ulative mastery over the built environment disin-

tegrates. The mirage of a complete control over

the quality of architecture and of an absolute

5. Tadao Ando, Church of the Light, view of interior 1, Ibaraki, Japan,

1989. (Courtesy of Tadao Ando Architect and Associates.)

6. Tadao Ando, Church of the Light, view of interior 2, Ibaraki, Japan,

1989. (Courtesy of Tadao Ando Architect and Associates.)

41 BAEK

-

8/9/2019 Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x] JIN BAEK -- Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

6/7

simulation of a settinghow it would appear in the

realdissolves. The real is now released from themechanism of prediction, control, and regulation. It

further operates as a glimpse into the otherwise

indescribable ideal.

One theory in architecture and urbanism that

we may understand using the Nishidian dialectic

between the ideal and the real is the theory of type

by Aldo Rossi (Figure 7). Rossi asserted that if

a building is to acquire the status of a monument

in the city, the core of the building should be

empty. This emptiness represents the capacity andopenness of a monumental building to accept

a performance that was not intended in its original

conception.23 David Leatherbarrow further quali-

fied Rossis idea of a monument in reference to

Rossis theory of type. According to him, a monu-

mental building can modify itself because it is

typologicallysuitable for the change. The Roman

basilica and the Christian church share the plot of

an axial progression that terminates at a raised

podium.24

The reason a Roman basilica can oper-ate as a Christian church of worship is because

both buildings seek to embody authority and

exaltation.

In this context, Rossi claimed that no type

can be identified with only one form, even if all

architecture forms are reducible to types.25 This

statement originates from Quatremere de Quincys

(17551849) argument that all is precise and

given in the model, all is more or less vague in the

type and developments and variations of formscan be simplified to their elementary principle. 26

Like Quatremere de Quincy, Rossi seems to

emphasize the reduction of particular buildings to

define their type. I would argue, however, that it is

possible to interpret Rossis statement in such

a way that it contrasts with the reductionist per-

spective; that type is a common ground that allows

the emergence of different monumental forms and

expressions rather than a logical abstraction sec-

ondary to the formation of particular forms.

If we understand Rossis type as an ideal that is

manifested in multifarious articulations, the rela-

tionship between the type and the particularmonumental forms is not that of the Platonic ideal

and its degradation but the Nishidian dialectic

between the ideal and the real. Again, there is no

ideal, unless there is the real, and there is no real,

unless there is the ideal. The ideal is felt and con-

cretized through the real, and the real with partic-

ularity constantly aims at reaching the ideal, as if

the ideal were a kind of limit point in integral and

differential calculus. Likewise, a type such as

authorityan ideal value in human historycomesto be palpable through a particular expression

a monumental building embodies.

Following Nishidas ideas further, it is not that

the ideal is logically abstracted from the particular

forms but that particular forms emerge as recog-

nizable from the beginning, thanks to the universal

operating at their depth. The reason one sees an

infinite line out of a broken piece of line drawn on

a blackboard is not because the infinite line is

logically derived from it. Rather, it is because fromthe beginning, one has an intuition of the infinite

line, and in turn, the broken line acquires its sig-

nificance in the dialectical reciprocity with the

intuited ideal or the infinite line. Despite Rossis

claim of the necessity to conduct a logical reduction

of particular forms to determine their type, the

truth of the matter is that the type has to be already

presupposed in therecognition of the monumental

forms themselves. Nevertheless, the significance of

Rossis typology should not be minimized. This isbecause it opens a path to locate type away from

the visible, formal realm in favor of the dialectic

between the unrepresentable ideal and the

represented real.

ConclusionsNishidas idea of emptiness offers a series of sig-

nificant architectural lessons. First of all, it locates

7. Piazza del Campo at Siena, Italy. (Photo by Steve Cooke, courtesy of the photographer.)

Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

Significance

42

-

8/9/2019 Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x] JIN BAEK -- Kitaro Nishidas Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural

7/7

architectural quality in a dialectical arena where

opposing values are copresent and interdependent.

This arena is equipped with the actively knowing

body of memory that senses and synthesizes the

values. Furthermore, this arena disavows theantagonism between idealism and realism. Instead,

it endorses the mutually enlivening dialectic

between the ideal and the real, the infinite and the

finite, and the eternal and the temporal. In this dia-

lectic, the side of the real is not denigrated but serves

as the dialogic party for the presence of the ideal.

Another lesson one can derive from Nishidas

emptiness pertains to the status of the author in

architectural creation. Nishida was critical of the

dichotomy between the author as the retainer ofa representational will and the world as the material

to be appropriated. He saw the author first and

foremost as the subject of immersion in the atmo-

sphere of a setting. This view of authorship relates

to key concepts of phenomenology. For instance, in

his idea of a saturated phenomenon, Jean-Luc

Marion redefined the subject into a receiverfrom

the world rather than the transcendental I who

constitutes the world before himself or herself.27 In

this redefined status of authorship both by Asianand by Western thinkers, the subject exists not as

the I of the manipulative master but as the pre-

I of empathy who is open to what is offered by the

world. The creation of a work conducted by the

pre-I compensates for the limitations of the self

through its boundless emphatic capacity. For this

reason, Nishida called such a work of art the pure

body (junsui shintai) of the artist, which is

apprehended prereflectively.28

Paradoxically, the hegemonic authorship, inwhich the author heroically collects the data of

a given context, deciphers them, selects figurative

motifs, and fabricates novel forms, endures in

contemporary architecture. For instance, accord-

ing to Manuel De Landa, the author outfitted with

genetic algorithms becomes the breeder of a

species of virtual form and the creator of a sig-

nature-bearing, abstract, topological diagram of

architecture. He or she is also the hacker, who

fabricates the code needed to bring extensive

and intensive aspects together and who [hacks]

biology, thermodynamics, mathematics and other

areas of science to tap into the necessary resour-ces.29 As many claim, this redefinition of authorship

by the populationist position is provocative. How-

ever, the breeder, the creator (of a topological dia-

gram), and the hacker are still different versions of

traditional hegemonic authorship. In addition, the

topological diagram, a primary product of such

authorship from which myriads of populating,

genetically bred variations are supposed to occur, is

little concerned with the continuity of the humane,

cultural world other than presenting sheer possibili-ties. How can one transform these sheer possibilities

into real possibilities that are meaningful in the

context of humanity?

One thing is clear. With the popularity of

thinking like Reiser and Umemotos, the discipline of

architecture is to a certain degree under the illusion

that the solution for the typologist is found in the

populationists emphasis on heterogeneous varia-

tions of entities in the space of absolute transpar-

ency and expansion. It is time to ask, however,whether we are not taking too facile a path to solve

the problem. Simultaneously, we should remind

ourselves of what Nishida struggled to grasp about

three-quarters of a century ago: Emptiness is the

concrete universal coexisting with the particular.

Notes

1. Jesse Reiser and Nanako Umemoto,Atlas of Novel Tectonics (New

York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006), p. 226.

2. Aristotle,Posterior Analytics , book II, chapter 19, 100b, pp. 1518, in

Richard McKeon, ed.,The Basic Works of Aristotle (New York: Random

House, 1941), p. 185; Robert E. Carter,The Nothingness Beyond God: An

Introduction to the Philosophy of Nishida Kitaro (St. Paul, MN: Paragon

House, 1997), pp. 2233.

3. Gilles Deleuze, Plato and Simulacrum, Rosalind Krauss, trans.,

October27 (1983): 47.

4. William LaFleur, Buddhist Emptiness in the Ethics and Aesthetics of

Watsuji Tetsuro,Religious Studies 14, no. 2 (June 1978): 247 (LaFleurs

italicization).

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Masao Abe, Non-Being andMu : The Metaphysical Nature of

Negativity in the East and West, Religious Studies 11, no. 2 (June

1975): 186.

9. The literature on Nagarjunas argument is numerous. One example

would be the following offered by William LaFleur: Nagarjunas philo-

sophical enterprise was directed to the rigorous analysis of entities which

someone might somehow assume to havesvabhava, self-existent reality

or existence in and of itself. Nagarjuna radically rejected any such possi-

bility and attempted to demonstrate that each and every entity was

empty of such self-existence. Another term, then, for this would be

dependent origination, or, even preferably, co-dependent origination.

W. LaFleur, Buddhist Emptiness in the Ethics and Aesthetics of Watsuji

Tetsuro, 244.

10. Kitaro Nishida,Complete Works (Nishida Kitaro Zenshu) (Tokyo:

Iwanami shoten, 1947), pp. 21719, 22931.

11. Kitaro Nishida,Art and Morality, David A. Dilworth and Valdo H.

Viglielmo, trans. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1973), pp. 1819.

12. David A. Dilworth, Introduction and Postscript, in Kitaro Nishida,

Last Writings: Nothingness and the Religious Worldview, David A.

Dilworth, trans. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1987),

pp. 56, 13031.

13. Ibid.

14. Kitaro Nishida,Fundamental Problems of Philosophy: The World of

Action and the Dialectical World, David A. Dilworth, trans. (Tokyo: Sophia

University, 1970), p. 22.

15. K. Nishida,Complete Works (Nishida Kitaro Zenshu), pp. 12326.

16. K. Nishida,Last Writings: Nothingness and the Religious Worldview,

p. 57.

17. K. Nishida,Complete Works (Nishida Kitaro Zenshu), 12930.

18. Ibid., p. 236.

19. Ibid., pp. 13839, 227; Joseph A. Bracken,The One in the Many:

A Contemporary Reconstruction of the God-World Relationship (Grand

Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2001), p. 114.

20. K. Nishida,Complete Works (Nishida Kitaro Zenshu), p. 141.

21. Aldo van Eyck,Aldo van Eycks Works , compilation by Vincent

Ligtelijn, Gregory Ball, trans. (Basel: Birkha user, 1999), p. 89.

22. K. Nishida,Complete Works (Nishida Kitaro Zenshu), pp. 13133.

23. Aldo Rossi,The Architecture of the City(Cambridge: MIT Press,

1984), p. 60.

24. David Leatherbarrow,The Roots of Architectural Invention: Site,

Enclosure, Materials(New York: CambridgeUniversity Press, 1993), p. 76.25. A. Rossi,The Architecture of the City, p. 41.

26. Quatremere de Quincy, Type in Encyclopedie Methodique, Paris,

1825, Anthony Vidler, trans., in Oppositions Reader, Selected Papers

1973-1984(New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), p. 128.

27. Jean-Luc Marion,Being Given: Toward a Phenomenology of

Givenness(Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), pp. 24852.

28. K. Nishida,Complete Works (Nishida Kitaro Zenshu), pp. 12829.

29. Manuel De Landa, Deleuze and the Use of the Genetic Algorithm in

Architecture, in Ali Rahim, ed.,Contemporary Techniques in Architecture

(New York: Wiley-Academy, 2002), pp. 912.

43 BAEK

![download Journal of Architectural Education Volume 62 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1531-314x.2008.00238.x] JIN BAEK -- Kitaro Nishida’s Philosophy of Emptiness and Its Architectural Significance](https://fdocuments.us/public/t1/desktop/images/details/download-thumbnail.png)

![The Journal of Creative Behavior Volume 42 Issue 2 2008 [Doi 10.1002%2Fj.2162-6057.2008.Tb01290.x]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/577c79b51a28abe05493c113/the-journal-of-creative-behavior-volume-42-issue-2-2008-doi-1010022fj2162-60572008tb01290x.jpg)

![Nations and Nationalism (Wiley) Volume 1 Issue 1 1995 [Doi 10.1111%2Fj.1354-5078.1995.00053.x] Michael Hechter -- Explaining Nationalist Violence](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/577cc7341a28aba711a049dc/nations-and-nationalism-wiley-volume-1-issue-1-1995-doi-1011112fj1354-5078199500053x.jpg)

![AGREEMENT FOR PROFESSIONAL SERVICES FOR [ARCHITECTURAL ... · AGREEMENT FOR PROFESSIONAL SERVICES FOR [ARCHITECTURAL / ENGINEERING ... [architectural] [engineering] [landscape architectural]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5b4b573d7f8b9aa82c8cbbe7/agreement-for-professional-services-for-architectural-agreement-for-professional.jpg)

![Art History Volume 30 Issue 3 2007 [Doi 10.1111%2fj.1467-8365.2007.00553.x] Sonja Neef -- Killing Kool- The Graffiti Museum](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/577ccf9c1a28ab9e78902912/art-history-volume-30-issue-3-2007-doi-1011112fj1467-8365200700553x.jpg)