Journal Final No.1 Vol.2 Jul- Dec 2013

-

Upload

hong-kheng -

Category

Documents

-

view

39 -

download

7

description

Transcript of Journal Final No.1 Vol.2 Jul- Dec 2013

EDITORIAL BOARD

Editor –in - Chief

Prof. (Dr). Kao Kveng Hong

Angkor Khemara University, Cambodia

Cambodia University of Specialties, Cambodia

Assistant and Members

Prof. (Dr.) Chhiv Thet

Paññāsāstra University of Cambodia, Cambodia

H. E. (Dr.) Mik Saphanaret

Bayon Book Publishing and National University of Management, Cambodia

Prof. (Dr.) Sao Lim Houth

Angkor University, Cambodia

Prof. (Dr. h.c.) Tithsothy Dianorin

Angkor University, Cambodia

Lect. Ma Bun Seng Rithy, PhD Candidate

Cambodia University of Specialties, Cambodia

Prof. Met Vichet

Vanda Accounting Institute, Cambodia

Prof. Leng Dina

Bayon Book Publishing Manager, Cambodia

INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD

Prof. (Dr.) Daniel Esteban Odin

The Business University of Costa Rica, Central America

Prof. (Dr.) Kvenghong Kao

St. Clement University, United Kingdom (UK)

Prof. (Dr.) George Reiff

EIILM University; India, Universidad Empresarial, Central America

Prof. (Dr.) Frederick U. Ozor

University of Gambia, West Africa

Prof. (Dr.) Arif Anjum

Managing Editor, International Journal of Management Studies, India

Prof. (Dr.) Andrew Ssemwaga

Kigali Independent University, West Africa

Prof. (Dr). Jayanta K. Nanda

Ravenshaw University, India

Prof. (Dr). Oyat Christopher

Gulu University, Northern Uganda, East Africa

Vol. 1, No. 2, July – December, 2013

IAJDR is the Official International Academic Journal of the University Group and Bayon

Book Under the Management of Asia Marketing Solution Co., LTD.

OFFICE:

Address 1: 1733 Pyrenees Ave, Apt 121, Stockton, California, CA95210, USA.

Address 2: 1607 South West Sylvester Lane, Florida, FL34984, USA.

Published Address 3: 2nd

Floor, No. 40Eo, St 324, Sangkat Beoung Salang, Khan Toulkok, Phnom

Penh, Cambodia, Phone: (855) – 23 6336889

Government Reg. No. 7112 MOC/ D/ REG

DISTRIBUTION OF THE JOURNAL:

The IAJDR Journal is distributed worldwide through our International and local Agencies. Both

Print and Online of The Journal is distributed to 180 Universities worldwide with total 150

Countries. This is not included the availability from sales in the Markets.

© Copyright with Bayon Book Publishing is under the management of Asia Marketing Solution

Co., LTD. No part of the publication may be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the

Editor-in- Chief, International Academic Journal of Development Research. However, the views

expressed in the articles or research papers are those of the authors and not of the editorial board or

publisher.

LANGUAGE POLICY:

IAJDR is an English Language publication and the Editorial Board aims to ensure that contributors

use grammatically correct and idiomatically appropriate English language. However, for many of

our contributors English is a second and even third language and from time to time a strict language

policy is modified to ensure that good articles are not excluded simply because they do not meet the

highest English standards. We also hold it to be important that material be not over edited, providing

its message is considered to be clear to the majority of our readers. The general objective that

IAJDR is to create conditions whereby all informed persons are able to contribute to the ongoing

debates, regardless of their English language competence and their lack of familiarity with accepted

journal protocols.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER

The publishers, authors and editors are not responsible for the results of any actions on the basis of

information in this work, nor for any errors or omissions. The publishers, authors and editors

expressly disclaim all and any liability to any person, whether a purchaser of this publication or not,

in respect of anything and the consequences of anything, done or omitted to be done by any such

person in reliance, in whole or part, on the contents of this publication. The views expressed in this

work are not necessarily the official or unanimous view of the office bearers of the IAJDR.

Web Site: www.ams-groups.com, www.bayonbook.com

Email: [email protected]

CONTRIBUTIONS: Contributions should be forwarded to

Prof. (Dr.) Kao Kveng Hong [email protected] or [email protected]

Prof. Leng Dina at [email protected] or [email protected]

Please note the Notes to Contributors at the back of this edition

International Academic Journal of Development

Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1 No.2, July-December, 2013

Contents Title Page

1. Capital Structure Analysis of Oil Industry:

A case study of Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (INDIA).

-Dr. S. K. KHATIK 1-20

2. History of Restriction of the Use and Display of Foreign

Educational Credentials through laws and decrees in

Germany from 1939 to 2012

-Georg Reiff 21-42

3. Glocal Operation Management

Step Ahead For Effective Supply Chain Managers

-Dr.Shakti Prasad Mohanty and Dr.Sanjay Kumar Rout 43-45

4. The Developing Concept Of The Professional The Nature

And Future Of Professionalism, And Its Implications For Academics,

Executives And Public Administrators

-Dr. Daniel Valentine 46-51

5. Relevance of Physics Education Programmes of The University of

the Gambia To the Teaching of Senior Secondary School

Physics in the Gambia.

- Dr.Nya Joe Jacob 52-73

6. Collective Learning and Knowledge Development in the Evolution of

Regional Clusters of High Technology SMEs in Europe

-Dr .David Keeble And Dr.Frank Wilkinson 74-91

7. Opportunity Of Financial Investmen In Cambodia

-Dr. Chhiv S. Thet 92-123

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

1

Capital Structure Analysis of Oil Industry – A case study of

Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (INDIA).

Dr. S. K. Khatik (Ph.D., M. Phil, M.Com)*

ABSTRACT

Capital structure, or what is generally known as capital mix, is very important to control the overall

cost of capital in order to improve the earnings per share of shareholders. After globalization and

liberalization, various financial sector reforms were started by governments, such as reducing rates

of interest, Sale of Shares of PSUs etc., which directly affected the capital structure planning of

firms. Due to this situation, the oil industry also reorganized their capital structure. The financing

of a capital structure decision is a significant managerial decision. Initially, the company will have

to plan its capital structure at the time of its promotion. Subsequently, whenever funds have to be

raised for finance and investment, a capital structure decision is involved. In this research article,

researchers try to evaluate the concept of capital structure, capital structure planning and patterns

of capital structure in BPCL Ltd. We found that BPCL uses the maximum possible reserve fund and

long-term debt in their capital structure planning. During the study period, the company raised

more and more long-term funds to meet their development and expansion needs because debt is a

cheaper source of finance, especially from 2005-06 onwards when rates of interest decreased

regularly in the Indian capital market. But in this study it is found that EBIT is greater than the cost

of capital, which was favorable for the company, but it is also giving alarming indication for the

company because debt capital has been increasing continuously and it leads to financial risk. These

things may cause losses in near future.

Keywords: Debt-Equity, Financial Leverage, Capital Gearing, Solvency, Debt Services,

Proprietary funds

I. Introduction

Capital structure is the mix of debt and equity

securities that are used to finance companies

assets. It is defined as the amount of permanent

short-term debt, preferred stock, and common

equity used to finance a firm. Financial

structure is sometimes used as synonymous

with capital structure. However, financial

structure is more comprehensive in the sense

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

2

that it refers to in aggregate; the amount of total

current liabilities, long-term debt, preferred

stock and common equity used to fiancé a firm.

Therefore, capital structure is only a part of

financial structure, which refers mainly to the

permanent sources of the firm s financing.

Nonetheless, the present study considers the

source, which does not explicitly fall under the

definition of capital structure.

Decision on capital structure formulation or

long term financing is influenced by multiple

factors. Much of the focus as laid in the

research on the subject pertains to the target

capital structure, which the firm believes the

best in terms of the financial goals. Financial

economics has made a significant progress in

explaining the incentives that make companies

choose particular financing policies .In the last

two decades, a number of choices have been

proposed to explain the variations in the debt

equity ratio among firms. Increasingly the

profession is moving beyond an examination of

the basic leverage choice to the more detailed

aspects of financing decisions

The term capital structure is used to represent

the proportionate relationship between debt and

equity. Equity includes paid up share capital,

share premium, reserves and surplus (retained

earnings). Debt includes debenture and long-

term loans. The estimation of capital

requirements for current and future needs is

important for a firm and equally important is

the determining of the capital mix. Equity and

debt are the two principal sources of finance for

a business. ―The financing decisions have two

components. First, to decide how much total

funds are needed and, second, to decide the

source or their combinations to raise such

funds. The total quantity of fund needed,

however, depends upon the investment decision

of the firm. Given that the firm has good

estimates of how much capital funds are

needed, the problem then remains one of

determining the best mix of different sources to

be used in raising the required funds. The

process that leads to the final choice of the

capital structure is referred to as the capital

structure planning.‖ The financing of a capital

structure decision is a significant managerial

decision. The company will initially have to

plan its capital structure at the time of its

promotion. Subsequently, whenever funds have

to be raised to finance investment, a capital

structure decision is involved. ―In order to run

and manage a company funds are needed right

from the promotional stage up to the end,

finances play an important role in a company‘s

life. If funds are inadequate, the business

suffers and if the funds are not properly

managed, the entire organization suffers. It is,

therefore, necessary that a correct estimate of

the current and future need of capital be made

to have an optimum capital structure, which

will help an organization to run its work

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

3

smoothly and without any stress.‖ Estimation

of capital requirement is necessary, but the

formation of a capital structure is important.

According to Gerstenbeg ―Capital structure of a

company refers to the composition or make up

of its capitalization and it includes all long-term

capital resources viz.; loans, reserves, shares

and bonds.‖ The capital structure is made up of

debt and equity securities and refers to the

permanent Financing of a firm. It is composed of

long-term debt, preference share capital and

shareholder funds. Keeping this background in

view, an attempt has been made by the researchers

to evaluate the ‗capital structure‘ of BPCL which

are leading oil refineries in public sector in India.

II. About the Company

BPCL is one of the leading

petrochemical company in India. In the

financial year 2011-12, the total revenue from

operations was 2, 11,972.97 Crores. On 24th

January 1976, the Burmah Shell Group of

Companies was taken over by the Government

of India to form Bharat Refineries Limited. On

1st August 1977, it was renamed Bharat

Petroleum Corporation Limited. Opening up of

the Indian economy in the nineties brought with

it more competition and challenges, kindled by

the phased dismantling of the Administered

Pricing Mechanism (APM) and emergence of

additional capacities in the region in refining

and marketing. It was also the first refinery to

process newly found indigenous crude

(Bombay High), in the country. It has four

main refineries are located in Mumbai, Kochi,

Numaligarh and Bina. BPCL imports products

depending upon the domestic demand supply

scenario. BPCL on a regular basis imports its

LPG requirements mainly from the Middle

East. Occasional there are import requirements

of Gasoil, Kerosene, Gasoline and Base Oil.

BPCL exports products from its refineries on a

regular basis. The products which are exported

regularly are Fuel Oil, Naphtha and Base Oil

(Group II). Products exports are done on both

FOB and CFR basis. Both import and export of

products are done through tender. Tender

invitations are only sent to counterparties who

are registered with BPCL. Companies

interested in registering with BPCL for

buying/supplying products.

III. Objectives of study

This research study fulfils the following

objectives:

i. To examine the capital structure pattern

and policy of BPCL Ltd.

ii. To examine the relationship between

profitability and capital structure

Company.

iii. To give suggestions for improvement of

the capital structure position of BPCL.

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

4

IV. Hypotheses of the study

Following are the null hypotheses of the study:

i. There is no significant difference in

debt and equity capital in BPCL.

ii. There is no significant difference in

EBIT and EBT in BPCL.

V. Limitations of the study

i. This study is based on an analysis of

the financial statement for 10

financial years i.e. 2003-2012 of

BPCL.

ii. For the analysis of capital structure,

only secondary data, which are

derived from the annual reports, has

been taken in this study.

VI. Data and Research Methodology

To analyze the capital structure of

BPCL, secondary data, collected from the

annual reports of the company, was used along

with other published material of the companies.

For the analysis of capital structure, the annual

reports from the year 2002-03 to 2011-12 used

in this study. For an analysis of the capital

structure of the company, the ratios of capital

structure, common size statement and trend

analysis techniques are used. Statistical

techniques, such as mean growth rate and

coefficient of variation, are also used in

relevant areas. To make calculation much

easier and logical, the data are approximated in

the relevant places. For the analysis of the

capital structure of BPCL, the following ratios

related to capital structure are used:

Debt equity, Interest coverage

Funded debt to total capitalization,

Fixed asset to net worth

Proprietary fund Ratio, Solvency

Fixed assets to long-term funds, Capital

gearing

Total investment to long-term liabilities,

Reserve to equity capital

Financial leverage, Earnings per Share.

VII. Appraisal of capital structure

The capital structure of a company consists of

debt and equity securities, which provide

Finance for a firm. An optimum capital

structure is one that maximizes the market

Valuation of the firm‘s securities in order to

minimize the cost of its capital.

VIII.Findings with detailed discussion

Debt Equity Ratio: The debt-equity ratio is

calculated to measure the extent to which debt

financing has been used in a business. The ratio

indicates the proportionate claims of owners

and outsiders against the firm‘s assets. The

purpose is to get an idea of the cash available to

outsiders on the liquidation of the firm. As a

general rule there should be an approximate

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

5

mix of owner‘s funds and outsider‘s funds in

financing the firm‘s assets. However, the

Capital structure analysis of the oil industry

owners want to carry on their business with a

maximum of outsider‘s funds in order to

reduce the risk of their investments and to

increase their earning per share by paying a

lower fixed rate of interest to outsiders. On the

other hand, outsiders want those Shareholders

(owners) to invest and risk a proportionate

share of their investments. Therefore, the

interpretation of this ratio depends upon the

financial policy of the firm and upon the firm‘s

nature of business.

Total Debt

Debt Equity Ratio = —————

Total Equity

Table no.1. Debt Equity Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

According to table no. 1, the debt equity ratio

for the year 2003 was 0.85:1. The ratio then

decreased in the year 2004 which was then

0.60:1. This ratio then increased and was 0.76:1

in the year 2005 and in the year 2006 the debt

equity ratio again increased and was 1.06:1.

This ratio further increased and was 1.19:1 in

the year 2007. In the year 2008 the debt equity

ratio was 1.41:1 and in the year 2009 the ratio

Year Debt(Rs.) Equity(Rs.) Debt-Equity Ratio

2003 4032.42 4,747.43 0.85

2004 3512.12 5,849.72 0.6

2005 4850.64 6388.43 0.76

2006 9729.44 9139.43 1.06

2007 12211.8 10273.5 1.19

2008 16503.7 11676.8 1.41

2009 22410.7 12128.1 1.85

2010 23054.5 13086.7 1.76

2011 19979.4 14057.6 1.42

2012 25861.2 14913.9 1.73

Mean 14214.6 10226.2 1.26

S.D. 8058.95 3400.59 0.42

C.V. 56.69% 33.25% 33.27%

Growth Rate 541.33% 214.15% 104.15%

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

6

was at its maximum when it was 1.85:1. The

debt equity ratio then decreased in the year

2010 when it was 1.76:1 and then further

decreased in the year 2011 when it was 1.42:1.

In the year 2012 the ratio was 1.73:1. The

overall average of debt equity ratio for the

period of the study was 1.26:1 and the standard

deviation was 0.42.The coefficient of variation

for the debt equity ratio was 33.27% and the

growth rate for the same was 104.15%.

Funded Debt to Total capitalization: The

ratio establishes a link between the long-term

funds raised from outsiders and total Long-term

funds available in the business. Funded debts to

total capitalization are also one of the important

ratios that explain the capital structure position

of a company. There is no rule of thumb but,

still, the lesser the reliance on outsiders the

better it will be. Also, the smaller the ratio the

better it will be. That the portion of debt

finance increases. It means that, in the study

period, the company has taken long-term

borrowing and ratio increases due to decreases

in free reserves.

Funded Debt

= —————————

Total Capitalization

Table no.2. Funded Debt to Total Capitalization Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Year Funded

Debt(Rs.) Total Capitalization(Rs.)

Funded Debt to Total

Capitalization Ratio

2003 4032.42 8,779.84 0.46

2004 3512.12 9,361.84 0.38

2005 4850.64 11239.1 0.43

2006 9729.44 18868.9 0.52

2007 12211.8 22485.4 0.54

2008 16503.7 28180.6 0.59

2009 22410.7 34538.8 0.65

2010 23054.5 36141.2 0.64

2011 19979.4 34037 0.59

2012 25861.2 40775.1 0.63

Mean 14214.6 24440.8 0.54

S.D. 8058.95 11373.4 0.09

C.V. 56.69% 46.53% 16.57%

Growth Rate 541.33% 364.42% 38.09%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

7

Interpretation

Table no 2, depicts that the funded debt to total

capitalization ratio was 0.46:1 in the year 2003.

The funded debt to total capitalization ratio in

the year 2004 was 0.38:1 and the ratio for the

year 2005 was 0.43:1. In the year 2006 the

funded debt to total capitalization ratio was

0.52:1 and the ratio for the same was 0.54:1 in

the year 2007. In the year 2008 the ratio was

0.59:1 and in the year 2009 the ratio was

0.65:1. In the year 2010 the funded debt to total

capitalization ratio was 0.64:1 and the ratio in

the year 2011 was 0.59:1. The ratio for the

same was 0.63:1 in the year 2012. The overall

average of the funded debt to total

capitalization ratio was 0.54:1 and the standard

deviation was 0.09. The coefficient of variation

for the funded debt to total capitalization ratio

was 16.57% and the growth rate for the same

was 38.09%.

Proprietary Ratio: This ratio established the

relationship between shareholders funds and

the total assets of the firm. The components of

this ratio are shareholder‘s funds and total

assets. As the proprietary ratio represents the

relationship of owners funds to total assets, the

higher the ratio (the share of the shareholders in

the total capitalization of the company) the

better is the long-term solvency and, from the

capital structure point of view, this ratio

indicates the extent to which the assets of the

company can be lost without affecting the

interest of the creditors of the company.

Proprietary Funds

Proprietary Ratio = ————————

Total Assets

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

8

Table no.3. Proprietary Fund Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Year Proprietary Fund(Rs.) Total Assets(Rs.) Proprietary Fund Ratio

2003 4,747.43 23,140.63 0.21

2004 5,849.72 25,225.43 0.23

2005 6388.43 28755.74 0.22

2006 9139.43 39361.3 0.23

2007 10273.5 45592.53 0.23

2008 11676.8 55496.22 0.21

2009 12128.1 61373.34 0.2

2010 13086.7 69459.46 0.19

2011 14057.6 73006.91 0.19

2012 14913.9 83337.37 0.18

Mean 10226.2 50474.89 0.21

S.D. 3400.59 20238.1 0.02

C.V. 33.25% 40.10% 8.64%

Growth Rate 214.15% 260.13% -12.77% Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

From table no.3, it is known that the

proprietary fund ratio was 0.21:1 in the year

2003 and the proprietary ratio was same for the

year 2004, 2006 and 2007 with value of

0.23:1. The proprietary ratio in the year 2005

was 0.22:1. In the year 2008 the ratio was

0.21:1 and the ratio in the year 2009 was

0.20:1. The proprietary fund ratio was same in

the year 2010 and in the year 2011 when it was

0.19:1 and in the year 2012 it was 0.18:1. The

overall average of the proprietary fund ratio

was 0.21:1 and the standard deviation was 0.02.

The coefficient of variation for the proprietary

fund ratio was 8.64% and the growth rate for

the same was -12.77%.

Solvency Ratio: The ratio indicates the

relationship between the total liabilities of

outsiders to total Assets of a firm. This ratio is

a small variant of equity ratio and can be

simply calculated as 100 – equity ratio.

Generally, the lower the ratio of total liabilities

to total assets, the more satisfactory or stable is

the long-term solvency position of a firm.

External Liabilities

Solvency Ratio = —————————

Total Assets

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

9

Table no.4. Solvency Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Year External Liabilities(Rs.) Total Assets(Rs.) Solvency Ratio

2003 12027 23,140.63 0.52

2004 11922.2 25,225.43 0.47

2005 14018.6 28755.74 0.49

2006 19136.4 39361.3 0.49

2007 23485.6 45592.53 0.52

2008 31084 55496.22 0.56

2009 35242 61373.34 0.57

2010 40185.7 69459.46 0.58

2011 41937.7 73006.91 0.57

2012 52093.7 83337.37 0.63

Mean 28113.3 50474.89 0.54

S.D. 13390.8 20238.1 0.05

C.V. 47.63% 40.10% 8.83%

Growth Rate 333.14% 260.13% 20.27%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

According to table no. 4, the solvency ratio in

the year 2003 was 0.52:1 which decreased and

was at its lowest in the year 2004 to 0.47:1.

The solvency ratio was the same for the year

2005 and 2006 when it was 0.49:1. In the year

2007 the solvency ratio then increased and was

0.52:1. The solvency ratio again increased in

the year 2008 when it was 0.56:1. The ratio

further increased and was same for two years

i.e., for 2009 and 2011 when it was 0.57:1. In

the year 2010 the solvency ratio was 0.58:1 and

in the year 2012 the solvency ratio was at its

maximum when it was 0.63:1. The overall

average of the solvency ratio was 0.54:1 and

the standard deviation was 0.05. The

coefficient of variation for the solvency ratio

was 8.83% and the growth rate for the same

was 20.27%.

Fixed Assets Ratio: The ratio establishes the

relationship between fixed assets and

shareholders fund. If the ratio is less than

100%, it implies that owner‘s funds are more

than total fixed assets and the shareholders

provide a part of the working capital. When the

ratio is more than 100%, it implies that owner‘s

funds are not sufficient to finance the fixed

assets and the firm has to depend upon

outsiders to finance the fixed assets. There is no

‗Rule of thumb‘ to interpret this ratio but 60%

to 65% is considered to be a satisfactory ratio

in the case of an industrial undertaking. The

ratio of fixed assets to net worth indicates the

extent to shareholders funds is into fixed assets.

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

10

Net Fixed Assets

Fixed Assets Ratio = ————————

Net Worth

Table no.5. Fixed Assets Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Year Net Fixed Assets(Rs.) Net worth(Rs.) Fixed Assets Ratio

2003 6,366.22 4,747.43 1.34

2004 7,453.48 5,849.72 1.27

2005 8348.67 6388.43 1.31

2006 11085.5 9139.43 1.21

2007 11833.4 10273.54 1.15

2008 12735.4 11676.84 1.09

2009 14003.3 12128.11 1.15

2010 16187.1 13086.71 1.24

2011 17011.6 14057.62 1.21

2012 17731.4 14913.86 1.19

Mean 12275.6 10226.17 1.22

S.D. 3819.66 3400.59 0.07

C.V. 31.12% 33.25% 5.93%

Growth Rate 178.52% 214.15% -11.34%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

From table no.5, it is known that the

fixed assets ratio was 1.34:1 in the year 2003

which was the maximum. In the year 2004 the

fixed assets ratio decreased and was 1.27:1 and

then the fixed assets ratio increased and was

1.31:1 in the year 2005. The fixed assets ratio

decreased and was the same for two years i.e.,

2006 and 2011 when it was 0.21:1. In the year

2007 the fixed assets ratio then decreased when

it was 1.15:1 and was the same in the year 2009

as well. In the year 2008 the fixed assets ratio

was 1.09:1. The fixed assets ratio then

increased in the year 2010 when it was 1.24:1

and in the year 2012 the fixed assets ratio was

1.19:1. The overall average of the fixed assets

ratio was 1.22:1 and the standard deviation was

0.07. The coefficient of variation for the fixed

assets ratio was 5.93% and the growth rate for

the same was -11.34%.

Fixed Assets to long-term funds: The ratio

indicates the extent to which the total assets are

financed by the long-term funds of the firm.

Generally, the total of fixed assets should be

equal to total long-term funds. But, where fixed

assets exceed the total of long-terms funds it

implies that the firm has been financing a part

of the fixed assets out of liquid funds or

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

11

working capital, which is not a good policy.

And, if the total long-term funds are more than

the total fixed assets, it means that a part of the

working capital requirements are being met out

of the long-term funds of the firms:

Fixed Assets

= ———————

Long term funds

Table no.6. Fixed Assets to Long Term Funds Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Year Net Fixed Assets(Rs.) Long Term Funds(Rs.) Fixed Assets to Long

Term Funds Ratio

2003 6,366.22 8,779.84 0.73

2004 7,453.48 9,361.84 0.8

2005 8348.67 11239.07 0.74

2006 11085.5 18868.86 0.59

2007 11833.4 22485.37 0.53

2008 12735.4 28180.58 0.45

2009 14003.3 34538.76 0.41

2010 16187.1 36141.21 0.45

2011 17011.6 34037.03 0.5

2012 17731.4 40775.08 0.43

Mean 12275.6 24440.76 0.56

S.D. 3819.66 11373.42 0.14

C.V. 31.12% 46.53% 24.26%

Growth Rate 178.52% 364.42% -40.03%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

Table no 6, shows that the fixed assets to long

term funds ratio in the year 2003 was 0.73:1

and in the year 2004 the ratio was 0.80:1. In the

year 2005 the fixed assets to long term funds

ratio was 0.74:1 and in the next year it was

0.59:1. The ratio for the year 2007 was 0.53:1

and in the year 2008 it was 0.45:1 and it was

same for the year 2010 as well. In the year

2009 the fixed assets to long term funds ratio

was 0.41:1 and in the year 2011 the fixed assets

to long term funds ratio was 0.50:1. At the end

in the year 2012 the ratio was 0.43:1. The

overall average of the fixed assets to long term

funds ratio was 0.56:1 and the standard

deviation was 0.14. The coefficient of variation

for the fixed assets to was 24.26% and the

growth rate for the same was -40.03%.

Long term funds ratio : Interest coverage

Ratio Net income to debt service ratio or

simply debt service ratio is used to test the debt

servicing capacity of a firm. The ratio is also

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

12

known as interest coverage ratio or Coverage

ratio or fixed changes cover or times interest

earned. This ratio is calculated by dividing the

net profit before interest and tax by fixed

interest charges. It indicates the interest-paying

capacity of a firm.

Operating profit

= ——————————

Fixed Interest Charges

Table no.7. Interest Coverage Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Year EBIT(Rs.) Fixed Interest

Charges(Rs.)

Interest Coverage

Ratio (Times)

2003 2,239.48 245.95 9.11

2004 2,740.49 104.97 26.11

2005 1496.15 139.8 10.7

2006 654.61 247.41 2.65

2007 3300.31 532.67 6.2

2008 3269.76 672.47 4.86

2009 3170.48 2166.37 1.46

2010 3377 1010.95 3.34

2011 3495.67 1100.78 3.18

2012 3683.76 1799.59 2.05

Mean 2742.77 802.1 6.96

S.D. 937.76 679.71 7

C.V. 34.19% 84.74% 100.57%

Growth Rate 64.49% 631.70% -77.52%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

According to table no. 7, the interest coverage

ratio was 9.11 times in the year 2003 and the

same in the year 2004 was 26.11 times, which

was the maximum, then it decreased and was

10.70 times in the year 2005. The interest

coverage ratio in the year 2006 was 2.65 times

which increased in the year 2007 and was 6.20

times. The interest coverage ratio was 4.86

times in the 2008 and in the year 2009 the

interest coverage ratio was 1.46 times. This

ratio increased in the year 2010 when it was

3.34 times which then decreased in the year

2011 to 3.18 times. The interest coverage ratio

in the year 2012 was 2.05 times. The overall

average of the interest coverage ratio was 6.96

and the standard deviation was 7.00. The

coefficient of variation for the interest coverage

ratio was 100.57% and the growth rate for the

same was -77.52%.

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

13

Capital Gearing ratio: The term capital

gearing is used to describe the relationship

between equity share capital, including reserves

and surpluses, and preference share capital and

other fixed interest-bearing loans. If preference

shares capital and other fixed interest-bearing

loans exceed the equity share capital including

reserves the firm is said to be highly geared.

The firm is said to be have a low gearing ratio

if preference shares and other fixed interest-

bearing loans are less than the equity capital

and reserves.

Equity Share Capital

= —————————————————

Preference shares & Long Term Loans

Table no.8. Capital Gearing Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Year Equity(Rs.) Preference Share &

Long Term Loans(Rs.) Capital Gearing Ratio

2003 4,747.43 4032.42 1.18

2004 5,849.72 3512.12 1.67

2005 6388.43 4850.64 1.32

2006 9139.43 9729.44 0.94

2007 10273.5 12211.83 0.84

2008 11676.8 16503.74 0.71

2009 12128.1 22410.65 0.54

2010 13086.7 23054.5 0.57

2011 14057.6 19979.41 0.7

2012 14913.9 25861.18 0.58

Mean 10226.2 14214.59 0.9

S.D. 3400.59 8058.95 0.36

C.V. 33.25% 56.69% 39.30%

Growth Rate 214.15% 541.33% -51.02%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

From table no.8, it is known that the capital

gearing ratio was 1.18:1 in the year 2003 and

the ratio in the year 2004 was 1.67:1. The

capital gearing ratio was 1.32:1 in the year

2005 and in the year 2006 it was 0.94:1. In

the year 2007 the capital gearing ratio was

0.84:1 and in the year 2008 the capital gearing

ratio was 0.71:1. The capital gearing ratio was

0.54:1 in the year 2009 and in the year 2010

the ratio for the same was 0.57:1. The capital

gearing ratio in the year 2011 was 0.70:1 and

it was 0.58:1 in the year 2012. The interest

coverage ratio in the year 2012 was 2.05

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

14

times. The overall average of the capital

gearing ratio was 0.90 and the standard

deviation was 0.36. The coefficient of

variation for the capital gearing ratio was

39.30% and the growth rate for the same was

-51.02%.

Total Investment to long term Funds:

The next ratio is calculated by dividing total

long-term funds by long-term liabilities.

Shareholders‘ funds and long-term liabilities

are components of total investments, and

debentures and long-term loans are

components of long-term liabilities,. This

ratio explains the position of long-term

liabilities in total investments. Normally, a

lower portion of long-term liabilities in total

investments is considered good in case of

solvency position of business.

Total Investment

= ——————————

Long term Liabilities

Table No.9. Total Investments to Long Term Liabilities Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Years Long Term

Funds(Rs.)

Long Term

Liabilities(Rs.)

Total Investments to Long

Term Liabilities Ratio

2003 8,779.84 4032.42 2.18

2004 9,361.84 3512.12 2.67

2005 11239.1 4850.64 2.32

2006 18868.9 9729.44 1.94

2007 22485.4 12211.83 1.84

2008 28180.6 16503.74 1.71

2009 34538.8 22410.65 1.54

2010 36141.2 23054.5 1.57

2011 34037 19979.41 1.7

2012 40775.1 25861.18 1.58

Mean 24440.8 14214.59 1.9

S.D. 11373.4 8058.95 0.36

C.V. 46.53% 56.69% 18.65%

Growth Rate 364.42% 541.33% -27.59%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

According to table No. 9, the total investment

to long term liabilities ratio in the year 2003

was 2.18:1 which then increased in the next

year to 2.67:1. The total investment to long

term liabilities ratio in the year 2005 was 2.32:1

and the ratio then decreased and kept on

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

15

decreasing. In the year 2006 the ratio was

1.94:1. The total investment to long term

liabilities ratio in the year 2007 was 1.84:1 and

it was 1.71:1 in the year 2008. The total

investment to long term liabilities ratio in the

year 2009 was 1.54:1 and for the year 2010 the

ratio was 1.57:1. The total investment to long

term liabilities ratio was 1.70:1 in the year 2011

and it was 1.58:1 in the year 20 12. The

overall average of the total investment to long

term liabilities ratio was 1.90 and the standard

deviation was 0.36. The coefficient of variation

for the total investment to long term liabilities

ratio was 18.65% and the growth rate for the

same was -27.59%.

Reserve fund to equity share capital: The

next ratio establishes the relationship between

reserves and equity share capital. The ratio

indicates that how much profit does the firm

generally retain to fund for future growth. The

higher the ratio, the better is the position of the

firm generally:

Reserves & Surplus

= ———————————

Equity Share Capital

Table no.10. Reserve Fund to Equity Share Capital Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Years Reserve Fund (Rs.) Equity Share

Capital(Rs.)

Reserve Fund to Equity

Share Capital Ratio

2003 4,447.43 300 14.82

2004 5,549.72 300 18.5

2005 6088.43 300 20.29

2006 8777.88 361.54 24.28

2007 9912 361.54 27.42

2008 11315.3 361.54 31.3

2009 11766.57 361.54 32.55

2010 12725.17 361.54 35.2

2011 13696.08 361.54 37.88

2012 14552.32 361.54 40.25

Mean 9883.09 343.08 28.25

S.D. 3375.84 28.2 8.17

C.V. 34.16% 8.22% 28.93%

Growth Rate 227.21% 20.51% 171.51%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

16

Interpretation

Table no 10, shows that in the year

2003 the reserve fund to equity share capital

ratio was 14.82:1 which was the lowest and

then the ratio increased and it kept on

increasing for the remaining study period. In

the year 2004 the reserve fund to equity share

capital ratio was 18.50:1 and in the year 2005

the reserve fund to equity share capital ratio

was 20.29:1. The ratio in the year 2006 was

24.28:1 and in the next year i.e. in 2007 the

reserve fund to equity share capital ratio was

27.42:1. The ratio for the same was 31.30:1 and

it was 32.55:1 in the year 2009. The ratio in the

year was 35.20:1 and it increased to 37.88: 1 in

the year 2011 and further increased in the year

2012 to 40.25:1. The overall average of the

reserve fund to equity share capital ratio was

28.25 and the standard deviation was 8.17. The

coefficient of variation for the reserve fund to

equity share capital ratio was 28.93% and the

growth rate for the same was 171.51%.

Financial leverage: The term financial

leverage refers to the use of fixed charges, such

as a debenture, and the use of variable charges

or securities, such as equity shares, in the

financial structure and total assets of the firm.

So, the financial leverage refers to the presence

of a fixed Charge in the income statement of

the firm. This fixed charge is fixed in amount

and does not vary with the changes in the

EBIT, whereas the return available to the

equity shareholders, which is a residual

balance, is affected by the changes in EBIT.

EBIT

= —————

EBT

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

17

Table no.11. Financial Leverage Ratio (Rs. In Crores)

Years EBIT(Rs.) EBT(Rs.) Financial Leverage Ratio

2003 2,239.48 1993.537 1.12

2004 2,740.49 2635.515 1.04

2005 1496.15 1356.348 1.1

2006 654.61 407.195 1.61

2007 3300.31 2767.644 1.19

2008 3269.76 2597.287 1.26

2009 3170.48 1004.11 3.16

2010 3377 2366.05 1.43

2011 3495.67 2394.89 1.46

2012 3683.76 1884.17 1.96

Mean 2742.77 1940.67 1.53

S.D. 937.76 745.74 0.6

C.V. 34.19% 38.43% 39.29%

Growth Rate 64.49% -5.49% 74.04%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

According to table no.11, the financial leverage

ratio in the year 2003 was 1.12:1 and in the

year 2004 the ratio was 1.04:1. This ratio

increased in the year 2005 when it was 1.10:1.

The financial leverage ratio in the year 2006

further increased and was 1.61:1. In the year

2007 the financial leverage ratio was 1.19:1

and this ratio in the year 2008 was 1.26:1. This

ratio was highest in the year 2009 when it was

3.16:1 and then it decreased in the year 2010 to

1.43:1. The financial leverage ratio in the year

2011 was 1.46:1 and in the year 2012 the ratio

increased to 1.96:1. The overall average of the

financial leverage ratio was 1.53 and the

standard deviation was 0.60. The coefficient of

variation for the financial leverage ratio was

39.29% and the growth rate for the same was

74.04%.

Earnings per Share (EPS)

Total earnings divided by the number of

share. Companies often use a weighted

average of shares outstanding over the

reporting term. EPS can be calculated for

the previous year ("trailing EPS"), for the

current year ("current EPS"), or for the coming

year ("forward EPS"). Note that last year's EPS

would be actual, while current year

and forward year EPS would be estimates.

Net profit after preference dividend

= ———————————————

No. of Equity Share

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

18

Table no.12. Earnings per Share (Rs. In Crores)

Years Earnings for Equity

Shareholders(Rs.)

No. of Equity

Shares

Earnings per

Share

2003 1,250.03 30 41.67

2004 1,694.57 30 56.49

2005 965.8 30 32.19

2006 291.65 36.15 8.07

2007 1805.48 36.15 49.94

2008 1580.56 36.15 43.72

2009 735.9 36.15 20.36

2010 1537.62 36.15 42.53

2011 1546.68 36.15 42.79

2012 1311.27 36.15 36.27

Mean 1271.96 34.31 37.4

S.D. 452.62 2.82 13.47

C.V. 35.58% 8.22% 36.01%

Growth Rate 4.90% 20.50% -12.95%

Source: Compiled from the annual reports of BPCL. (From 2003 - 2012)

Interpretation

From table no.12, it is known that the earning

per share for the year 2003 was Rs.41.67 which

increased to Rs.56.49 in the year 2004. The

earning per share for the year 2005 was

Rs.32.19 and it was Rs.8.07 in the year 2006.

The earning per share for the year 2007 was

Rs.49.94 and in the year 2008 the earning per

share was Rs.43.72. The earning per share was

Rs.20.36 for the year 2009 and in the year 2010

the earnings per share was Rs.42.53. The

earning per share for the year 2011 was

Rs.42.79 and it was Rs.36.27 in the year 2012.

The overall average of the earning per share

was Rs.37.40 and the standard deviation was

13.47. The coefficient of variation for the

earning per share was 36.01% and the growth

rate for the same was -12.95%.

Testing of Hypothesis

H01 : The Coefficient of Correlation

between Debt and Equity was 0.70

which shows a positive relation between

Net profit and Net sales. It means that

both Debt and Equity were moving in

the same direction but relatively at a

moderate pace. When Students t test

was calculated with these two

parameters, the calculated value of t=

38.81 was less than the table value of t=

2.305. Hence the null hypothesis is

rejected and alternate hypothesis stands

accepted. It shows that there is

significant difference between Debt and

Equity during the period of study.

H02 : The Coefficient of Correlation

between EBIT and EBT was 0.96 which

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

19

shows a higher positive relation

between Current Assets and Current

Liabilities. It means that both EBIT and

EBT were moving in the same direction

but relatively at a higher pace. When

Students t test was calculated with these

two parameters, the calculated value of

t= 3.82 was more than the table value of

t= 2.305. Hence the null hypothesis is

rejected and alternate hypothesis stands

accepted. It shows that there is

significant difference between EBIT

and EBT during the period of study.

Findings and Suggestions

The Debt Equity position of the

company is not adequate as per the

financial aspect, because a company can

easily employ a debt capital up o 2:1

times. This will be adequate for the

company as per the Indian scenario.

During the study period it has employed

less debt capital in the business. But

after 2005-06 the debt capital has been

increasing up to 2011-12, which is good

sign for the company. Company enjoys

worth of debt capital in their business.

Funded debt to total capitalization in the

beginning stage was not satisfactory but

it gradually increased till 2011-12.

Proprietary ratio was low during the

period of study. It needs upliftment of

this ratio for better future prospects.

Solvency ratio of the firm was

satisfactory. Fixed assets to net worth of

the firm was also not satisfactory. Fixed

assets to long term loans was

satisfactory as the firm was having good

financial policies.

Interest coverage ratio of the firm was

satisfactory. It was able to overcome the

Financial risk and able to bear the

financial cost timely.

Capital gearing ratio observed low

gearing value in the starting years and

then it shifted to high gearing value in

remaining years.

Financial Leverage of the firm was

satisfactory as it was able to pay the

interest on long term loans and

advances timely.

In the beginning years the firm does not wanted

to take financial risk as the amount of debt

capital employed in the business was low. But

BPCL have return on capital employed greater

than the rate of interest, then after the company

increased the debt capital. The capital structure

of the firm may be adequate, but it may require

some improvement in the debt capital position

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

20

of the business as per the nature of the

business. The company should make better

investment avenues for utilization of huge

amount of reserves and surplus.

References

Annual reports of bpcl from 2003 to 2011-12

Balwani, N. (2000) Accounting and Finance

for Managers, Amexcel Publisher‘s

Private Ltd., p.772.

Banerjee, S.K. (2000) Financial Management,

S. Chand and Company, New Delhi.

Bhalla, V.K. (1997) Financial Management

and Policy, 1st ed., Anmol Publications,

Engler, G.N. (Ed.) (1973) Managerial Finance:

Cases and Readings, Inc, Dalla. Galgotia

Publishing Company, New Delhi, p.860.

Guthmann, H.G. and Dougall, H.E. (1995)

Corporate Financial Policy, 4th

ed.,

Prentice Hall of India Pvt. Ltd, pp.84-85.

Hampton, J.J. (1998) Financial Decision-

Making, Concepts, Problem and Cases,

Prentice Hall of India Pvt. Ltd, New

Delhi.

Jagdish, Prakesh, Rao and Shukla (1996)

Administration of Public Enterprise in

India, Himalaya Publishing Company,

New Delhi.

Khan and Jain (1997) Financial Management,

Tata McGraw Hill Publishing

Company, New Delhi. New Delhi.

Pandey, I.M. (2000) Financial Management

Theory and Practices, Vikas Publishing

Company, New Delhi.

Rustagi, R.P. (2000) Financial Management,

Theory, Concept and Problems, 2nd ed.,

Wachowicz, V.H.J.C. (1998) Fundamental of

Financial Management, 9th ed.,

Prentice Hall Inc, New Delhi.

Walker, E.W. (1974) Essentials of Financial

Management, Prentice Hall of India Pvt.

Ltd, New Delhi.

* Dr. S. K. KHATIK (Ph.D., M. Phil, M.Com)

Professor & Head, Department of

Commerce, Barkatullah University,

BHOPAL.

Dean, Faculty of Commerce, Barkatullah

University , Bhopal. Chairman, Board of

Studies Commerce, Barkatullah University,

BHOPAL.

Mobile: 9425382036

E-Mail: [email protected]

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

21

History of Restriction of the Use and Display of Foreign Educational

Credentials through laws and decrees in Germany from 1939 to 2012

Dr. Georg Reiff*

ABSTRACT

Contemporary Germany is usually known as a democratic country, deeply integrated into the US-

American dominated Western political bloc. However, little-known to the general public, there are

obviously legal remnants that stem from the previous infamous Hitler Regime. After seeing some

fellow alumni from a non-German distance learning university in 2007 encountering problems in

Germany, I decided to investigate deeper the underlying legal structure and legal principles. The

objective was to shed light whether or not the problems of those fellow alumni were caused not only

by old laws for example coming from Imperial times but by legal principles that were directly

created during the Hitler times in Germany. On a secondary basis, it was also scientifically sound

to investigate whether or not such severe restrictions like in Ger-many occur in other countries as

well and on what principles they are based. As an instrument of inquiry the historical method of

comparison as specified first by Bern-heim in 1889 and others afterwards has been used. Due to the

fact that all legal texts are documented online through the German Government very well and up to

date, they are without disambiguation regarding the sources, and so it was entirely possible to draw

up a less than desirable picture of how foreign educational credentials are treated in contemporary

Germany with the indirect help of German authorities. The achievement was not only an

explanation of how come that foreign credentials in Germany oftentimes cause such trouble for the

holder but the very reason behind a structure that actually hunts down perceived perpetrators in a

way unbecoming for any Western democratic state became obvious – the use of false legal

principles stemming in full from a totalitarian state in a totalitarian time.

Key Words: History of Restriction, Display, Foreign Educational Credential, Decrees,

laws.

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

22

I. Introduction

In these times of globalization, the world

moves closer together and this also applies to

the field of education and the use of foreign

educational credentials. Also, more and more

people inside and outside Germany wish to

pursue their studies and continuing education

together while having a professional career.

The establishment of UNESCO is for example

a major step in recognizing this change in

international education early on. Often studies

take place even outside the German jurisdiction

or we have the case where non-Germans

migrate to Germany in order to live and work

there and further their respective careers.

II. Background and Context

The oldest university in Europe, the University

of Bologna, was founded in 1088. In Bologna,

the interests of the Holy Roman Emperor of

German Nation were crucial for the

development of an effective university

education for lawyers. Competition to the

papacy as a secular power was dependent on

this in order not to depend on and to deal

exclusively with monks and clergy as civil

servants. Instead there was the aim to build up

a work force of non-clergy civil servants as

well within the empire.

The development of universities, especially

established for the Legal Education can be

considered a separation process from the

educational monopoly of the Church that lasted

from the end of Rome in 476 until then. The

contrary was for example the emergence of the

University of Paris. By centralizing education

in a single school of higher education it was

supposed to better monitor theologians and

therefore avoid heresies. Its name is related to

the times of Robert de Sorbon, who once

started teach-ing with 5 penniless students in

order to give them a theological education long

before the creation of the University of Paris.

The members of the Sorbonne, founded by

Papal Bull were under the Pope‘s rule and

ecclesiastical jurisdiction and not at all under

the legal authority of the French king.

The French king also confirmed this. The

jurisdiction was exercised by the Chancellor of

the University who was not a member of the

university, but acted as a representative of the

bishop. He also awarded the academic degrees.

The University of Paris and its degrees were

the templates for almost all Western uni-

versities, particularly the British, among them

prominently Oxford University and the German

universities. Thomas Aquinas studied e.g. in

Paris and entered the faculty 1248 as a teacher

of philosophy with such acclaim that he

received the titles of Doctor Universalis and

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

23

Doctor Angelicus. One can consider those titles

as the blue prints for later doctoral programs.

Originally, the doctorate was therefore a purely

religious matter and the first three doc-tors in

the sense of ecclesial dignity thus are the

Doctors of the Church, Ambrose, Jerome and

Augustine. Pope Gregory I, however, saw the

trend of times and quickly changed the law in

order to make the doctorate also the highest

degree for all faculties.

This historical course of events is ultimately the

reason why churches in the U.S. till today hand

out merely religiously motivated doctorates to

their bible scholars and dig-nitaries according

to the old tradition. Such doctoral church

honours, however, should not be considered as

exactly equal compared to that what modern

academic degrees are.

Like the doctorate, the bachelor degree is also

an academic degree since the 13th Cen-tury,

albeit the lowest ranking. It was also awarded

first at the University of Paris.

The middle level between Bachelor and Doctor

is the Master of Arts (Magister Ar-tium), which

has its precedence in antiquity and throughout

the Middle Ages as conclusion of the studies of

the seven liberal arts (Septem Artes Liberalis).

It means something like "Master of Arts" in a

wider sense and is therefore not limited to

artistic areas. Historical example of this degree

is in turn again from the University of Paris at

which the German mystic Meister Eckhart

(Master Eckhart in English) re-ceived his

master's degree in 1302, when he passed the

final exam in Paris. He then worked as a

teacher at the University of Paris, and at the

same time he became the first provincial of his

religious order in Germany.

III. Overview of the History of

Restrictions of Foreign Degrees

The first occurrence of a restriction in

Germany for the use of foreign degrees

occurred under the knocked out Weimar

Constitution in 1939 when ―Imperial

Chancellor‖ and then already de facto

totalitarian dictator Adolf Hitler promulgated a

new law governing the use of foreign degrees

in Germany. The law was aimed predominantly

at Jewish scholars who often had titles and

degrees from foreign Torah Colleges, but it

also applied to many opposition persons who

were not in line with the purification mania of

National Socialist ideologists. It is noteworthy

that in 1939 though formally in existence, the

democratic constitution of the Weimar

Republic had already been knocked out for six

years by the so-called Enabling Act of 1933.

This Act permitted the National Socialist

Regime to act at will outside the provisions of

the democratic constitution in order to

implement rules and regulations according to

their totalitarian will.

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

24

In regards to foreign education, the National

Socialists expressed their totalitarian views in a

law named the Academic Degree Act

(Akademisches Grad Gesetz). This was

promulgated in June 1939. In particular,

Section 1 of the law provided that:

German nationals who obtained an

academic degree from a foreign

university were required to seek

permission from the Imperial Minister

for Science, Education and Peoples

Education to display (display and use in

public) this degree.

The permission (for displaying the

degree) could be given in general in

regards to academic degrees from

certain foreign universities.

It is further stated (Section 2) that:

Among the requirements which are

mentioned in Section 1, the Imperial

Minister for Science, Education and

Peoples Education can withdraw a

previously given permission for

displaying a foreign academic degree

and in the case of a general permission

(Section 2:2) the Minister can order the

withdrawal (of the permission) in

individual cases.

In July 1939, a Decree was issued entitled:

―Regulation Implementing the Law on the use

of Academic Titles‖ (AkaGrGDV) and

Schwarz-Rot-Goldene Titelträger, page 32,

Schneekluth Publishers, 1971 . This regulation

referred to Section 8 of the Act and prescribed

that:

An application for authorization to

display a foreign degree (Section 2:1

and Section 3 of the Act) must be

presented directly to the Minister for

Science and Education. The application

shall contain the following:

matriculation certificate, study and audit

evidence or a certified copy of the

award certificate and a certified

translation into German, all must be

accompanied by: curriculum vitae.

As to be considered a temporary stay (in

Germany) in the sense of Section 3:2 of

the Act, the subject‘s stay may not

exceeds the period of three months.

Following the license (to

use/display/mention a foreign degree), a

certificate is is-sued to the applicant.

The aforementioned provisions shall not

apply in cases where the approval has

been given generally for displaying a

particular foreign university‘s degrees

according to Section 2:2 of the Act.

The withdrawal of a domestically

conferred university degree is to be

decided by a committee consisting of

the Rector of the University and the

Deans. At universities, where

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

25

structuring into faculties (departments)

is missing, the deans are replaced by

two lecturers of the university appointed

for a period of five years by the

Imperial Minister for Science and

Education.

The decision of the Committee shall be

effective upon delivery. Notification is

in accordance with the rules of civil

procedure regarding servicing one of its

motions.

The decision on a waiver of a

withdrawal (Section 4:4) is possible

after consulting the aforementioned

Committee according to Section 3:1 of

this Regulation.

The validity of this specific regulation ended

together with the Academic Degree Act in

2007, surviving its creator by 62 years.

However, we shall see (below) that exactly

those legal principles, which governed the

Academic Degree Act and especially the

‗Regulation Implementing the Law on the use

of Academic Titles‘ have been incorpo-rated in

the General Permission Decree from April

2000 and the Educational State Laws that

followed.

The following paragraphs set out what has

changed in recent years in the understanding of

the law nationally and the state laws of

Germany and what one has to look at the

various levels of regulations. However, this

dissertation will show that even the new laws in

Germany that lead on the surface to the transfer

of responsibility regarding presentation of

educational credentials towards the citizens, no

matter whether they are local or foreign, are

deeply tainted. I would have agreed with this

relatively reasonable approach by the

legislature till I noticed that there has taken

place a simple compilation of previous laws

and regulations which are based on quite

draconic law principles from a non-democratic

dictatorial time. Therefore, it should also be

mentioned that Germany is in an unprecedented

way the hardest jurisdiction when it comes to

the use of foreign credentials and that does in

my opinion not really go along with the

principle of alleged open-mindedness that the

Federal Republic of Germany wants to make

the world-public and her own populace believe

in.

This present dissertation here is the first of its

kind that has been made available for foreign

academicians and also workers who are

credential holders and intend to work and live

in the Federal Republic of Germany. As part of

the European Union it is only natural that

mobility of the work force of all of Europe and

the world will bring far more foreign credential

holders to Germany than in the past. As

German regulations are more than just strict

and hardly comparable to the regulations in

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

26

other regions of the world, this dissertation is

intended to spare the reader legal hassle,

embarrassment and possible court appearance

and fines in Germany. A book for the general

public is planned immediately afterwards.

1. Displaying and Using a

Degree - Then and Now:

Having noted the contents of the Law,

we need to consider a definition for

‗displaying, mentioning and using a degree‘

(einen Grad führen). To display, mention, use

(führen) a degree publicly in Germany means

the following:

Putting the academic title on a letter

head

Putting the academic title on a business

card

Putting the academic title on bell

Mentioning the title more than once

when talking to another individual, even

at different occasions

But, it is the opinion of this author that the

Germans had and still have: (1) a rigid idea of

what constitutes holding a degree; (2) no regard

for free speech in the matter. Further, I will

argue that the law (Section 4:3) opens the door

wide for individual dis-crimination in that an

individual can be forbidden to hold a foreign

academic degree even if the use of his specific

foreign alma mater was generally permitted in

Germany. The ‗lucky ones‘, whose foreign

degrees were recognized, had them

―nostrificated‖, i.e. converted into matching

German degree, a process only known to most

of us through the recognition of our driver‘s

licenses when we change the country of resi-

dence.

2.The Legal Position Today

The 1939 Act and the accompanying

Regulation was only revoked in 2007

(Bundesrecht aufgehoben durch Art. 9 Abs. 2 G

v. 23.11.2007. To understand this long delay

we need to refer to what happened to Germany

after the 8th of May 1945. Germany lost the

WW II and the winners had a problem as they

had enabled United Nations basic structures

and the Atlantic Charter before the end of the

war. According to the legal basics prescribed it

was not permitted to annex other country‘s

territory. Although, German territory was

annexed and mainly given to Poland (and half

of the East German Province East Prussia to the

Soviet Russians themselves) whose eastern

territory in turn was annexed by Soviet Russia

and incorporated mainly into Belo Russia).

Thus, to facilitate an on-going presence in

Germany, the Allies of WWII did simply not

―close down‖ the Weimar Republic (still

German Realm or German Empire) but

partitioned it into three parts and erected two

puppet states, one in the West, Federal

Republic of Germany, one in the Middle,

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

27

German Democratic Republic GDR (nowadays

historically erroneously called East Germany)

and a third part that was separated, emptied of

the prevalent German population by ethnic

cleansing and given to Poland and then Soviet

Russia as described above.

The West German ‗puppet state‘ FRG

prevailed over the Communist counterpart, the

German Democratic Republic‘ due to its

economic strength and in 1990 the GDR was

incorporated in the FRG with the blessing of all

former Allies of WW II. As the an-nexation

still cannot be legally finalized according to

current international law, as a shrewd legal

solution the Federal Republic of Germany

claimed to be identical with the German Realm,

in regards to the territory ―partially identical‖.

So we have the schizophrenic fact that on one

hand the FRG has dropped for herself all

claims of the lands that have been given to

Poland. On the other hand, due to the FRG‘s

claim to be the German Realm it must maintain

to accept a population that can show, for

example, a German family name or a German

grandfather or grandmother from the annexed

third part of Germany. We will encounter

effects of this internationally little known fact

later on within the educational laws of

contemporary Germany.

This annexation issue is also the reason why to

date a German constitution does not exist, but a

surrogate constitution called ―Basic Law‖. In

addition, it is the reason why there is no

formally correct peace treaty between Germany

and its former enemies but the so-called 2+4

Treaty that defines and approves certain

changes in the FRG‘s status and is presented

usually as the equivalent of a Peace Treaty.

This legal gymnastics is illustrated best as

something similar to the Operating System,

Windows, with all its contemporary layers of

modern user interfaces, under which we find

the old-fashioned DOS system. If we compare

the old laws of the German Realm with DOS,

and if we compare the contemporary laws of

the Federal Republic of Germany with modern

Versions of Windows Operating Systems, we

see what is expressed in Article 123 of the

Basic Law of the FRG.

Contemporary Germany has some underlying

laws of the German Realm and some

regulations developed by the former Allied

Occupiers (SHAEF) that are still in force. As

the Allies of WW II, mainly the US, brought

their ideas of laws into the Federal Republic of

Germany, it goes without saying that education

became an affair of the federal states in

Germany as well. And so the above-mentioned

Academic Degree Law from 1939

(Akademisches Grad Gesetz) survived its

creator Mr Hitler for five decades and was

incorporated into State law and Statutes. With

the advent of the European Union, however,

those old legal structures have led to friction

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

28

and an increasing number of legal actions have

put the FRG leadership under pressure to effect

change. For instance, EU Directive 89/48/EEC,

established in 1988, stipulates that there may

not be any form of discrimination against

degrees from membership states of the EU, so

in April 2000 Germany‘s Permanent

Conference of State Education Ministers,

promulgated the General Permission Decree

and all 16 states agreed to implement the

provisions till the dead line in 2005.

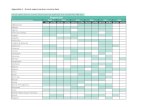

3. What do the 16 German State

Laws Say Today?

The General Permission Decree from

2000 and all State laws require that a foreign

degree must come from a university/college

that is recognized as such in the country of

origin. Furthermore, the conferred degree must

be recognized by the country of origin.

However, some state laws only require that the

university/college itself be recognized. In Table

1, those states marked with ―1‖ permit foreign

degree if the university/college is

governmentally recognized. Those marked ―2‖

require that not only the university/college but

also the degree itself must be recognized

explicitly by the government. Honorary degree

must always come from institutions that are

gov-ernmentally permitted to issue the

corresponding academic degree. Concerning

this, only a few states permit the use of an

abbreviated degree (marked with ―3‖), whereas

the hardline states require the degree written in

complete words (marked ―4‖). There is one

state (Mecklenburg) that discriminates openly

against transfer of academic credits from

private academies located in Germany and

elsewhere towards academic degrees at foreign

universities as practiced, for example, by the

University of Wales7 in the United Kingdom.

The state is indicated with ―5‖. Another state

(Hesse) indicates that the foreign degree must

be considered ‗an academic degree according

to European regulations‘; this remains obscure

as no EU law is mentioned, neither is there any

indication given that the regulation requires

observance of the educational laws of the 27

EU Member states. This ‗exceptionally

intelligent work‘ of German jurisprudence is

marked with ―6‖.

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

29

Table 1: Indications of the Requirements of

State Laws Relating to Foreign Degrees8

(Refer Text)

Baden-Württemberg 1 4

Bavaria 1 3

Berlin 2 4

Brandenburg 2 4 5

Bremen 1 3

Hamburg 1 4

Hesse 2 3 6

Mecklenburg-Pomerania 2 4

Lower Saxony 2 3

North Rhine Westphalia 1 3

Rhineland Palatine 2 4

Saarland 2 4

Saxony 2 3

Saxony-Anhalt 2 4

Schleswig-Holstein 2 4

Thuringia 1 4

4.The General Permission Regulation

Grundsätze für die Regelung der

Führung ausländischer Hochschulgrade im

Sinne einer gesetzlichen Allgemeingen

ehmigung durch einheitliche gesetzliche

Bestimmungen (Beschluss der

Kultusministerkonferenz vom 14.04.2000)

Basic principles for regulating the use / display

/mention of foreign higher educational degrees

in terms of a general statutory authorization by

uniform legislation (Resolution of the

Education Minister Conference of 14.04.2000)

1. Ein ausländischer Hochschulgrad, der

aufgrund eines nach dem Recht des

Herkunftslandes anerkannten Hochschul

abschlusses nach einem ordnungsgemäß durch

Prüfung abgeschlossenen Studium verliehen

worden ist, kann in der Form, in der er

verliehen wurde unter Angabe der verleihenden

Hochschule geführt werden. Dabei kann die

verliehene Form ggf. transliteriert und die im

Herkunftsland zugelassene oder nachweislich

allgemein übliche Abkürzung geführt und eine

wörtliche Übersetzung in Klammern

hinzugefügt werden. Eine Umwandlung in

einen entsprechenden deutschen Grad findet

mit Ausnahme zugunsten der nach dem

Bundesvertriebenengesetz Berechtigten nicht

statt. Entsprechendes gilt für staatliche und

kirchliche Grade.

1. A foreign higher education degree,

which was awarded according to the law of the

country of origin as a recognized academic

degree after due study concluded by

examination, can be used/ displayed/

mentioned in the wording in which it was

awarded while also mentioning the awarding

higher education institution. Furthermore, the

original wording of the award may be

transliterated (into Latin letters) and the permit-

ted acronym or the evidently generally used

abbreviation may be used/ displayed/

International Academic Journal of Development Research (IAJDR) Vol. 1, No. 2, July-December, 2013

30

mentioned and a literal translation (into

German) may be added in brackets.

A conversion into a corresponding German

degree does not take place except for those

entitled according to the Federal Displaced

Persons Law (from the former Eastern

Provinces, which are now de facto parts of

Russia and Poland). The same applies to

governmental and ecclesiastical degrees.

2. Ein ausländischer Ehrengrad, der von einer

nach dem Recht des Herkunftslandes zur

Verleihung berechtigten Hochschule oder

anderen Stelle verliehen wurde, kann nach

Maßgabe der für die Verleihung geltenden

Rechtsvorschriften in der verliehenen Form

unter Angabe der verleihenden Stelle geführt

werden. Ausgeschlossen von der Führung sind

Ehrengrade, wenn die ausländische Institution

kein Recht zur Vergabe des entsprechenden

Grades im Sinne der Ziffer 1 besitzt.

2. A foreign honorary degree, awarded by an