Points South: Ambrose Bierce, Jorge Luis Borges, and the ...

Jorge Luis Borges

description

Transcript of Jorge Luis Borges

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 1 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Jorge Luis Borges

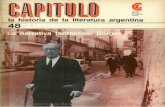

Borges in 1951, by Grete Stern

Born Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges24 August 1899Buenos Aires, Argentina

Died 14 June 1986 (aged 86)Geneva, Switzerland

Occupation Writer, poet, translator, editor, critic,librarian

Language Spanish

Nationality Argentine

Signature

Jorge Luis BorgesFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges KBE(Spanish: [ˈxorxe ˈlwis ˈβorxes] audio ) (24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer,essayist, poet and translator, and a key figure in theSpanish language literature. His work embraces the"character of unreality in all literature".[1] His best-knownbooks, Ficciones (Fictions) and The Aleph (El Aleph),published in the 1940s, are compilations of short storiesinterconnected by common themes, including dreams,labyrinths, libraries, mirrors, fictional writers, philosophy,and religion.

Borges's works have contributed to philosophicalliterature and also to the fantasy genre. Critic ÁngelFlores, the first to use the term magical realism to define agenre that reacted against the dominant realism andnaturalism of the 19th century,[2] considers the beginningof the movement to be the release of Borges's A UniversalHistory of Infamy (Historia universal de la infamia).[2][3]

However, some critics would consider Borges to be apredecessor and not actually a magical realist. His latepoems dialogue with such cultural figures as Spinoza,Camões, and Virgil.

In 1914 his family moved to Switzerland, where hestudied at the Collège de Genève. The family travelledwidely in Europe, including stays in Spain. On his returnto Argentina in 1921, Borges began publishing his poemsand essays in surrealist literary journals. He also workedas a librarian and public lecturer. In 1955 he wasappointed director of the National Public Library andprofessor of English Literature at the University ofBuenos Aires. He became completely blind at the age of55; as he never learned braille, he became unable to read.Scholars have suggested that his progressive blindness helped him to create innovative literary symbolsthrough imagination.[4] In 1961 he came to international attention when he received the first PrixInternational, which he shared with Samuel Beckett. In 1971 he won the Jerusalem Prize. His work wastranslated and published widely in the United States and in Europe. Borges himself was fluent in severallanguages. He dedicated his final work, The Conspirators, to the city of Geneva, Switzerland.[5]

His international reputation was consolidated in the 1960s, aided by his works being available in English, bythe Latin American Boom and by the success of García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude.[6] Writerand essayist J. M. Coetzee said of him: "He, more than anyone, renovated the language of fiction and thus

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 2 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

opened the way to a remarkable generation of Spanish American novelists."[7]

Contents

1 Life and career1.1 Early life and education1.2 Early writing career1.3 Later career1.4 International renown1.5 Later personal life

2 Political opinions2.1 Anti-Communism2.2 Anti-Fascism2.3 Anti-Peronism2.4 Military junta

3 Works3.1 Hoaxes and forgeries3.2 Criticism of Borges' work3.3 Sexuality3.4 Nobel Prize omission

4 Fact, fantasy and non-linearity4.1 Borgesian conundrum

5 Culture and Argentine literature5.1 Martín Fierro and Argentine tradition5.2 Argentine culture5.3 Multicultural Influences

6 Influences6.1 Modernism6.2 Political influences6.3 Mathematics

7 Ancestry8 Notes9 References10 Further reading

10.1 Documentaries11 External links

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 3 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Jorge Luis Borges in 1921

Life and career

Early life and education

Jorge Luis Borges was born into an educated middle-class family on24 August 1899. They were in comfortable circumstances but notwealthy enough to live in downtown Buenos Aires. They resided inPalermo, then a poorer suburb. Borges's mother, Leonor AcevedoSuárez, came from a traditional Uruguayan family of criollo(Spanish) origin. Her family had been much involved in theEuropean settling of South America and the Argentine War ofIndependence, and she spoke often of their heroic actions.[8] Borges's1929 book Cuaderno San Martín includes the poem "IsidoroAcevedo", commemorating his grandfather, Isidoro de AcevedoLaprida, a soldier of the Buenos Aires Army. A descendant of theArgentine lawyer and politician Francisco Narciso de Laprida,Acevedo fought in the battles of Cepeda in 1859, Pavón in 1861, andLos Corrales in 1880. Isidoro de Acevedo Laprida died of pulmonarycongestion in the house where his grandson Jorge Luis Borges wasborn. Borges grew up hearing about the faded family glory. Borges'sfather, Jorge Guillermo Borges Haslam, was part Spanish, partPortuguese, and half English, also the son of a colonel. BorgesHaslam, whose mother was English, grew up speaking English athome and took his own family frequently to Europe. England and English pervaded the family home.[8]

At nine, Jorge Luis Borges translated Oscar Wilde's The Happy Prince into Spanish. It was published in alocal journal, but his friends thought the real author was his father.[9] Borges Haslam was a lawyer andpsychology teacher who harboured literary aspirations. Borges said his father "tried to become a writer andfailed in the attempt." He wrote, "as most of my people had been soldiers and I knew I would never be, I feltashamed, quite early, to be a bookish kind of person and not a man of action."[8]

Borges was taught at home until the age of 11, was bilingual in Spanish and English, reading Shakespeare inthe latter at the age of twelve.[8] The family lived in a large house with an English library of over onethousand volumes; Borges would later remark that "if I were asked to name the chief event in my life, Ishould say my father's library."[10] His father gave up practicing law due to the failing eyesight that wouldeventually afflict his son. In 1914, the family moved to Geneva, Switzerland, and spent the next decade inEurope.[8] Borges Haslam was treated by a Geneva eye specialist, while his son and daughter Norahattended school, where Borges junior learned French. He read Thomas Carlyle in English, and he began toread philosophy in German. In 1917, when he was eighteen, he met Maurice Abramowicz and began aliterary friendship that would last for the rest of his life.[8] He received his baccalauréat from the Collège de

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 4 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Adolfo Bioy Casares, VictoriaOcampo and Borges in 1935

Genève in 1918.[11][Notes 1] The Borges family decided that, due to political unrest in Argentina, they wouldremain in Switzerland during the war, staying until 1921. After World War I, the family spent three yearsliving in various cities: Lugano, Barcelona, Majorca, Seville, and Madrid.[8]

At that time, Borges discovered the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer and Gustav Meyrink's The Golem(1915) which became influential to his work. In Spain, Borges fell in with and became a member of theavant-garde, anti-Modernist Ultraist literary movement, inspired by Guillaume Apollinaire and FilippoTommaso Marinetti, close to the Imagists. His first poem, "Hymn to the Sea," written in the style of WaltWhitman, was published in the magazine Grecia.[12] While in Spain, he met noted Spanish writers,including Rafael Cansinos Assens and Ramón Gómez de la Serna.

Early writing career

In 1921, Borges returned with his family to Buenos Aires. He had little formal education, no qualificationsand few friends. He wrote to a friend that Buenos Aires was now "overrun by arrivistes, by correct youthslacking any mental equipment, and decorative young ladies".[8] He brought with him the doctrine ofUltraism and launched his career, publishing surreal poems and essays in literary journals. Borges publishedhis first published collection of poetry, Fervor de Buenos Aires, in 1923 and contributed to the avant-gardereview Martín Fierro. Borges co-founded the journals Prisma, a broadsheet distributed largely by pastingcopies to walls in Buenos Aires, and Proa. Later in life, Borges regretted some of these early publications,attempting to purchase all known copies to ensure their destruction.[13]

By the mid-1930s, he began to explore existential questions andfiction. He worked in a style that Argentinian critic Ana MaríaBarrenechea has called "Irreality." Many other Latin Americanwriters, such as Juan Rulfo, Juan José Arreola, and Alejo Carpentier,were also investigating these themes, influenced by thephenomenology of Husserl and Heidegger and the existentialism ofJean-Paul Sartre. In this vein, his biographer Williamson underlinesthe danger in inferring an autobiographically-inspired basis for thecontent or tone of certain of his works: books, philosophy andimagination were as much a source of real inspiration to him as hisown lived experience, if not more so.[8] From the first issue, Borgeswas a regular contributor to Sur, founded in 1931 by VictoriaOcampo. It was then Argentina's most important literary journal andhelped Borges find his fame.[14] Ocampo introduced Borges toAdolfo Bioy Casares, another well-known figure of Argentine

literature, who was to become a frequent collaborator and close friend. Together they wrote a number ofworks, some under the nom de plume H. Bustos Domecq, including a parody detective series and fantasystories. During these years, a family friend Macedonio Fernández became a major influence on Borges. Thetwo would preside over discussions in cafés, country retreats, or Fernandez's tiny apartment in the Balvaneradistrict. He appears by name in Borges's "Dialogue about a Dialogue",[15] in which the two discuss theimmortality of the soul.

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 5 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Jorge Luis Borges in the 1940s

In 1933, Borges gained an editorial appointment at the literary supplement of the newspaper Crítica, wherehe first published the pieces collected as Historia universal de la infamia (A Universal History of Infamy) in1935.[8] The book includes two types of writing: the first lies somewhere between non-fictional essays andshort stories, using fictional techniques to tell essentially true stories. The second consists of literaryforgeries, which Borges initially passed off as translations of passages from famous but seldom-read works.In the following years, he served as a literary adviser for the publishing house Emecé Editores and from1936 to 1939 wrote weekly columns for El Hogar. In 1938, Borges found work as first assistant at theMiguel Cané Municipal Library. It was in a working class area[16] and there were so few books thatcataloguing more than one hundred books per day, he was told, would leave little to do for the other staffand so look bad. The task took him about an hour each day and the rest of his time he spent in the basementof the library, writing and translating.[8]

Later career

Borges's father died in 1938. This was a particular tragedy for thewriter as the two were very close. On Christmas Eve that year,Borges suffered a severe head injury; during treatment, he nearlydied of septicemia. While recovering from the accident, Borgesbegan playing with a new style of writing for which he wouldbecome famous. His first story written after his accident, "PierreMenard, Author of The Quixote" came out in May 1939. One of hismost famous works, "Menard" examines the nature of authorship, aswell as the relationship between an author and his historical context.His first collection of short stories, El jardín de senderos que sebifurcan (The Garden of Forking Paths), appeared in 1941,composed mostly of works previously published in Sur.[8] The titlestory concerns a Chinese professor in England, Dr. Yu Tsun, whospies for Germany during World War I, in an attempt to prove to theauthorities that an Asian person is able to obtain the information that they seek. A combination of book andmaze, it can be read in many ways. Through it, Borges arguably invented the hypertext novel and went on todescribe a theory of the universe based upon the structure of such a novel.[17][18] Eight stories taking up oversixty pages, the book was generally well received, but El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan failed to garnerfor him the literary prizes many in his circle expected.[19][20] Victoria Ocampo dedicated a large portion ofthe July 1941 issue of Sur to a "Reparation for Borges." Numerous leading writers and critics fromArgentina and throughout the Spanish-speaking world contributed writings to the "reparation" project.

With his vision beginning to fade in his early thirties and unable to support himself as a writer, Borges begana new career as a public lecturer.[Notes 2][21][22] He became an increasingly public figure, obtainingappointments as President of the Argentine Society of Writers and as Professor of English and AmericanLiterature at the Argentine Association of English Culture. His short story "Emma Zunz" was made into afilm (under the name of Días de odio, Days of Hate, directed in 1954 by Leopoldo Torre Nilsson).[23]

Around this time, Borges also began writing screenplays.

In 1955, he was nominated to the directorship of the National Library. By the late 1950s, he had becomecompletely blind. Neither the coincidence nor the irony of his blindness as a writer escaped Borges:[8]

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 6 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Borges at L'Hôtel, Paris, 1969

Nadie rebaje a lágrima o reprocheesta declaración de la maestríade Dios, que con magnífica ironíame dio a la vez los libros y la noche.

No one should read self-pity or reproachInto this statement of the majestyOf God; who with such splendid irony,

Granted me books and night at one touch.[24]

The following year the University of Cuyo awarded Borges the first of many honorary doctorates and in1957 he received the National Prize for Literature .[25] From 1956 to 1970, Borges also held a position as aprofessor of literature at the University of Buenos Aires and other temporary appointments at otheruniversities.[25] In the fall of 1967 and spring of 1968, he delivered the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures atHarvard University.[26]

As his eyesight deteriorated, Borges relied increasingly on his mother's help.[25] When he was not able toread and write anymore (he never learned to read Braille), his mother, to whom he had always been close,became his personal secretary.[25] When Perón returned from exile and was re-elected president in 1973,Borges immediately resigned as director of the National Library.

International renown

Eight of Borges's poems appear in the 1943 anthology ofSpanish American Poets by H.R. Hays.[27][Notes 3] "TheGarden of Forking Paths", one of the first Borges stories tobe translated into English, appeared in the August 1948issue of Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, translated byAnthony Boucher.[28] Though several other Borgestranslations appeared in literary magazines and anthologiesduring the 1950s, his international fame dates from theearly 1960s.[29]

In 1961, Borges received the first Prix International, whichhe shared with Samuel Beckett. While Beckett had garnereda distinguished reputation in Europe and America, Borgeshad been largely unknown and untranslated in the English-speaking world and the prize stirred great interest in hiswork. The Italian government named BorgesCommendatore and the University of Texas at Austinappointed him for one year to the Tinker Chair. This led tohis first lecture tour in the United States. In 1962, two majoranthologies of Borges's writings were published in Englishby New York presses: Ficciones and Labyrinths. In thatyear, Borges began lecture tours of Europe. Numeroushonors were to accumulate over the years such as a Special Edgar Allan Poe Award from the MysteryWriters of America "for distinguished contribution to the mystery genre" (1976),[30] the Balzan Prize (for

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 7 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

María Kodama at the 2010 FrankfurtBook Fair

Philology, Linguistics and literary Criticism) and the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca and the Cervantes Prize(all 1980), as well as the French Legion of Honour (1983).

In 1967, Borges began a five-year period of collaboration with the American translator Norman Thomas diGiovanni, through whom he became better known in the English-speaking world. He also continued topublish books, among them El libro de los seres imaginarios (Book of Imaginary Beings, (1967, co-writtenwith Margarita Guerrero), El informe de Brodie (Dr. Brodie's Report, 1970), and El libro de arena (The Bookof Sand, 1975). He also lectured prolifically. Many of these lectures were anthologized in volumes such asSiete noches (Seven Nights) and Nueve ensayos dantescos (Nine Dantesque Essays). His presence, also in1967, on campus at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA) influenced a group of students amongwhom was Jared Loewenstein, who would later become founder and curator of the Jorge Luis BorgesCollection at UVA,[31] one of the largest repositories of documents and manuscripts pertaining to the earlyworks of JLB.[32]

Later personal life

In 1967, Borges married the recently widowed Elsa Astete Millán.Friends believed that his mother, who was 90 and anticipating herown death, wanted to find someone to care for her blind son. Themarriage lasted less than three years. After a legal separation, Borgesmoved back in with his mother, with whom he lived until her death atage 99.[33] Thereafter, he lived alone in the small flat he had sharedwith her, cared for by Fanny, their housekeeper of many decades.[34]

From 1975 until the time of his death, Borges traveledinternationally. He was often accompanied in these travels by hispersonal assistant María Kodama, an Argentine woman of Japaneseand German ancestry. In April 1986, a few months before his death,he married her via an attorney in Paraguay, in what was then acommon practice among Argentines wishing to circumvent theArgentine laws of the time regarding divorce.

On his religious views, Borges declared himself as an agnostic.[35]

Jorge Luis Borges died of liver cancer in 1986 in Geneva and wasburied there in the Cimetière des Rois. Kodama, his widow and heir

on the basis of the marriage and two wills, gained control over his works. Her assertive administration of hisestate resulted in a bitter dispute with the French publisher Gallimard regarding the republication of thecomplete works of Borges in French, with Pierre Assouline in Le Nouvel Observateur (August 2006) callingher "an obstacle to the dissemination of the works of Borges". Kodama took legal action against Assouline,considering the remark unjustified and defamatory, asking for a symbolic compensation of oneeuro.[36][37][38] Kodama also rescinded all publishing rights for existing collections of his work in English,including the translations by Norman Thomas di Giovanni, in which Borges himself collaborated, and fromwhich di Giovanni would have received an unusually high fifty percent of the royalties. Kodamacommissioned new translations by Andrew Hurley, which have become the standard translations inEnglish.[39]

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 8 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Borges and the Argentine writerErnesto Sabato.

Political opinions

Anti-Communism

In an interview with Richard Burgin during the late 1960s, Borgesdescribed himself as an adherent of Classical Liberalism. He furtherrecalled that his opposition to Marxism and Communism wasabsorbed in his childhood. "Well, I have been brought up to thinkthat the individual should be strong and the State should be weak. Icouldn't be enthusiastic about theories where the State is moreimportant than the individual."[40] After the overthrow via coupd'etat of President Juan Domingo Perón in 1955, Borges supportedefforts to purge Argentina's Government of Peronists and dismantlethe former President's welfare state. He was enraged that theCommunist Party of Argentina opposed these measures and sharplycriticized them in lectures and in print. Borges's opposition to theParty in this matter ultimately led to a permanent rift with hislongtime lover, Argentine Communist Estela Canto.[41] In later years,Borges frequently expressed contempt for Marxists and Communistswithin the Latin American intelligentsia. In an interview with Burgin,Borges referred to Chilean poet Pablo Neruda as "a very fine poet"but a "very mean man" for unconditionally supporting the SovietUnion and demonizing the United States.[42]

Anti-Fascism

In 1934, Argentine ultra-nationalists, sympathetic to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, asserted Borges wassecretly Jewish, and by implication, not a "true" Argentine. Borges responded with the essay "Yo, Judío" ("I,a Jew"), a reference to the old "Yo, Argentino" ("I, an Argentine"), a defensive phrase used during pogromsof Argentine Jews to make it clear to attackers that an intended victim was not Jewish.[43] In the essay hesays that he would be proud to be a Jew, with a backhanded reminder that any "pure" Castilian might belikely to have Jewish ancestry from a millennium ago.[43]

Both before and during the Second World War, Borges regularly published essays attacking the Nazi policestate and its racist ideology. His outrage was fueled by his deep love for German literature. In an essaypublished in 1937, Borges attacked the Nazi Party's use of children's books in order to inflame antisemitism.He wrote, "I don't know if the world can do without German civilization, but I do know that its corruptionby the teachings of hatred is a crime."[44]

In a 1938 essay, Borges reviewed an anthology which rewrote German authors of the past to fit the Naziparty line. He was disgusted by what he described as Germany's "chaotic descent into darkness" and theattendant rewriting of history. He argues that such books sacrifice culture, history and honesty in the name ofdefending German honour. Such practices, he writes, "perfect the criminal arts of barbarians."[45] In a 1944essay, Borges postulated,

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 9 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Nazism suffers from unreality, like Erigena's hell. It is uninhabitable; men can only die for it, liefor it, wound and kill for it. No one, in the intimate depths of his being, can wish it to triumph. Ishall risk this conjecture: Hitler wants to be defeated. Hitler is blindly collaborating with theinevitable armies that will annihilate him, as the metal vultures and the dragon, (which musthave known that they were monsters), collaborated, mysteriously, with Hercules."[46]

In 1946, Borges published the short story "Deutsches Requiem", which masquerades as the last testament ofOtto Dietrich zur Linde, a condemned Nazi war criminal. In a 1967 interview with Burgin, Borges recalledhow his interactions with Argentina's Nazi sympathisers led him to create the story.

And then I realized that those people that were on the side of Germany, that they never thoughtof German victories or the German glory. What they really liked was the idea of the Blitzkrieg,of London being on fire, of the country being destroyed. As to the German fighters, they took nostock in them. Then I thought, well now Germany has lost, now America has saved us from thisnightmare, but since nobody can doubt on which side I stood, I'll see what can be done from aliterary point of view in favor of the Nazis. And then I created the ideal Nazi.[47]

Anti-Peronism

In 1946, Juan Perón began transforming Argentina into a Justicialist system with the assistance of his wifeEva. Almost immediately, the spoils system was the rule of the day, as ideological critics of the new orderwere dismissed from government jobs. During this period, Borges was informed that he was being"promoted" from his position at the Miguel Cané Library to a post as inspector of poultry and rabbits at theBuenos Aires municipal market. Upon demanding to know the reason, Borges was told, "Well, you were onthe side of the Allies, what do you expect?"[48] In response, Borges resigned from Government service thefollowing day.

Perón's treatment of Borges became a cause célèbre for the Argentine intelligentsia. The Argentine Societyof Writers (SADE) held a formal dinner in his honour. At the dinner, a speech was read which Borges hadwritten for the occasion. It said,

Dictatorships breed oppression, dictatorships breed servility, dictatorships breed cruelty; moreloathsome still is the fact that they breed idiocy. Bellboys babbling orders, portraits of caudillos,prearranged cheers or insults, walls covered with names, unanimous ceremonies, merediscipline usurping the place of clear thinking... Fighting these sad monotonies is one of theduties of a writer. Need I remind readers of Martín Fierro or Don Segundo that individualism isan old Argentine virtue."[49]

In the aftermath, Borges found himself much in demand as a lecturer and one of the intellectual leaders ofthe Argentine opposition. In 1951 he was asked by anti-Peronist friends to run for president of SADE.Borges, then suffering from depression caused by a failed romance, reluctantly accepted. He later recalledthat he would awake every morning and remember that Perón was President and feel deeply depressed andashamed.[50] Perón's government had seized control of the Argentine mass media and regarded SADE withindifference. Borges later recalled, however, "Many distinguished men of letters did not dare set foot insideits doors."[51] Meanwhile, SADE became an increasing refuge for critics of the regime. SADE official LuisaMercedes Levinson noted, "We would gather every week to tell the latest jokes about the ruling couple and

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 10 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Borges in 1976.

even dared to sing the songs of the French Resistance, as well as 'La Marseillaise'."[51]

After Evita's death on July 26, 1952, Borges received a visit from two policemen, who ordered him to put uptwo portraits of the ruling couple on the premises of SADE. Borges indignantly refused, calling it aridiculous demand. The policemen icily retorted that he would soon face the consequences.[52] The regimeplaced Borges under 24-hour surveillance and sent policemen to sit in on his lectures; in September itordered SADE to be permanently closed down. Like much of the Argentine opposition to Perón, SADE hadbecome marginalized due to persecution by the State, and very few active members remained.

According to Edwin Williamson,

Borges had agreed to stand for the presidency of theSADE in order [to] fight for intellectual freedom, buthe also wanted to avenge the humiliation he believedhe had suffered in 1946, when the Peronists hadproposed to make him an inspector of chickens. In hisletter of 1950 to Attilio Rossi, he claimed that hisinfamous promotion had been a clever way thePeronists had found of damaging him anddiminishing his reputation. The closure of the SADEmeant that the Peronists had damaged him a secondtime, as was borne out by the visit of the Spanishwriter Julián Marías, who arrived in Buenos Airesshortly after the closure of the SADE. It wasimpossible for Borges, as president, to hold the usualreception for the distinguished visitor; instead, one ofBorges' friends brought a lamb from his ranch, andthey had it roasted at a tavern across the road fromthe SADE building on Calle Mexico. After dinner, afriendly janitor let them into the premises, and theyshowed Marías around by candlelight. That tinygroup of writers leading a foreign guest through adark building by the light of guttering candles wasvivid proof of the extent to which the SADE had beendiminished under the rule of Juan Perón.[53]

On September 16, 1955, General Pedro EugenioAramburu's Revolución Libertadora toppled the electedgovernment and forced Perón to flee into exile. Borges was overjoyed and joined demonstrators marchingthrough the streets of Buenos Aires. According to Williamson, Borges shouted, "Viva la Patria," until hisvoice grew hoarse. At his mother's prompting, the de facto Aramburu regime appointed Borges as theDirector of the National Library.[54]

In his subsequent essay L'Illusion Comique, Borges denounced the conspiracy theories which the PeronistState had spread through the press and speeches. In conclusion, he wrote:

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 11 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

...one can only denounce the duplicity of the fictions of the former regime, which can't bebelieved and were believed. It will be said that the public's lack of sophistication is enough toexplain the contradiction; I believe that the cause is more profound. Coleridge spoke of the"willing suspension of disbelief," that is, poetic faith; Samuel Johnson said, in defense ofShakespeare, that the spectators at a tragedy do not believe they are in Alexandria in the first actand Rome in the second but submit to the pleasure of a fiction. Similarly, the lies of adictatorship are neither believed nor disbelieved; they pertain to an intermediate plane, and theirpurpose is to conceal or justify sordid or atrocious realities.[55]

In a 1967 interview, Borges said, "Perón was a humbug, and he knew it, and everybody knew it. But Peróncould be very cruel. I mean, he had people tortured, killed. And his wife was a common prostitute."[56]

When Perón returned from exile in 1973 and regained the Presidency, Borges was enraged. In a 1975interview for National Geographic, he said "Damn, the snobs are back in the saddle. If their posters andslogans again defile the city, I'll be glad I've lost my sight. Well, they can't humiliate me as they did beforemy books sold well."[57] After being accused of being unforgiving, Borges quipped, "I resented Perón'smaking Argentina look ridiculous to the world... as in 1951, when he announced control over thermonuclearfusion, which still hasn't happened anywhere but in the sun and the stars. For a time, Argentinians hesitatedto wear band aids for fear friends would ask, 'Did the atomic bomb go off in your hand?' A shame, becauseArgentina really has world-class scientists."[57]

After Borges' death in 1986, the Peronist Partido Justicialista declined to send a delegate to the writer'smemorial service in Buenos Aires. A spokesman for the Party said that this was in reaction to "certaindeclarations he had made about the country."[58] One Peronist declared that Borges had made statementsabout Evita Perón which were "unacceptable." Later, at the City Council of Buenos Aires, a storm ragedwhen Peronist politicians decided to give only conditional support for a condolence on the writer's death.[58]

Military junta

During the 1970s, Borges at first expressed support for Argentina's military junta, but was scandalized by thejunta's actions during the Dirty War. In protest against their support of the regime, Borges ceased publishingin the newspaper La Nación.[59]

In 1985 he wrote a short poem about the Falklands War called Juan López y John Ward, about two fictionalsoldiers (one from each side), who died in the Falklands, in which he refers to "islands that were toofamous". He also said about the war: "The Falklands thing was a fight between two bald men over acomb."[60]

WorksWardrip-Fruin and Montfort argue that Borges "may have been the most important figure in Spanish-language literature since Cervantes. He was clearly of tremendous influence, writing intricate poems, shortstories, and essays that instantiated concepts of dizzying power."[61]

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 12 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Tomb of Jorge Luis Borges, Cimetièredes Rois, Plainpalais.

In addition to short stories for which he is most noted, Borges also wrote poetry, essays, screenplays, literarycriticism, and edited numerous anthologies. His longest work of fiction is a fourteen-page story, "TheCongress", first published in 1971.[8] His late-onset blindness strongly influenced his later writing. Borgeswrote: "When I think of what I've lost, I ask, 'Who know themselves better than the blind?' – for everythought becomes a tool."[62] Paramount among his intellectual interests are elements of mythology,mathematics, theology, integrating these through literature, sometimes playfully, sometimes with greatseriousness.[63]

Borges composed poetry throughout his life. As his eyesight waned (it came and went, with a strugglebetween advancing age and advances in eye surgery), he increasingly focused on writing poetry, since hecould memorize an entire work in progress.[64] His poems embrace the same wide range of interests as hisfiction, along with issues that emerge in his critical works and translations, and from more personal musings.For example, his interest in idealism runs through his work, reflected in the fictional world of Tlön in "Tlön,Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" and in his essay "A New Refutation of Time".[65] It also appears as a theme in "OnExactitude in Science" and in his poems "Things" and "El Golem" ("The Golem") and his story "TheCircular Ruins".

Borges was a notable translator. He translated works of literature in English, French, German, Old English,and Old Norse into Spanish. His first publication, for a Buenos Aires newspaper, was a translation of OscarWilde's story "The Happy Prince" into Spanish when he was nine.[66] At the end of his life he produced aSpanish-language version of a part of Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda. He also translated (whilesimultaneously subtly transforming) the works of, among others, William Faulkner, André Gide, HermannHesse, Franz Kafka, Rudyard Kipling, Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, and Virginia Woolf.[Notes 4] Borgeswrote and lectured extensively on the art of translation, holding that a translation may improve upon theoriginal, may even be unfaithful to it, and that alternative and potentially contradictory renderings of thesame work can be equally valid.[67] Borges also employed the devices of literary forgery and the review ofan imaginary work, both forms of modern pseudo-epigrapha.

Hoaxes and forgeries

Borges's best-known set of literary forgeries date from his early workas a translator and literary critic with a regular column in theArgentine magazine El Hogar. Along with publishing numerouslegitimate translations, he also published original works, forexample, in the style of Emanuel Swedenborg[Notes 5] or OneThousand and One Nights, originally claiming them to betranslations of works he had chanced upon. In another case, he addedthree short, falsely attributed pieces into his otherwise legitimate andcarefully researched anthology El matrero.[Notes 5] Several of theseare gathered in the A Universal History of Infamy.

At times he wrote reviews of nonexistent writings by some otherperson. The key example of this is "Pierre Menard, Author of theQuixote", which imagines a twentieth-century Frenchman who triesto write Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote verbatim, not by having

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 13 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Jorge Luis Borges Monument inSantiago de Chile

memorized Cervantes's work but as an "original" narrative of his own invention. Initially the Frenchmantries to immerse himself in sixteenth-century Spain, but he dismisses the method as too easy, instead tryingto reach Don Quixote through his own experiences. He finally manages to (re)create "the ninth and thirty-eighth chapters of the first part of Don Quixote and a fragment of chapter twenty-two." Borges's "review" ofthe work of the fictional Menard uses tongue-in-cheek comparisons to explore the resonances that DonQuixote has picked up over the centuries since it was written. He discusses how much "richer" Menard'swork is than that of Cervantes's, even though the actual text is exactly the same.

While Borges was the great popularizer of the review of an imaginary work, he had developed the idea fromThomas Carlyle's Sartor Resartus, a book-length review of a non-existent German transcendentalist work,and the biography of its equally non-existent author. In This Craft of Verse, Borges says that in 1916 inGeneva "[I] discovered, and was overwhelmed by, Thomas Carlyle. I read Sartor Resartus, and I can recallmany of its pages; I know them by heart."[68] In the introduction to his first published volume of fiction, TheGarden of Forking Paths, Borges remarks, "It is a laborious madness and an impoverishing one, themadness of composing vast books, setting out in five hundred pages an idea that can be perfectly relatedorally in five minutes. The better way to go about it is to pretend that those books already exist, and offer asummary, a commentary on them." He then cites both Sartor Resartus and Samuel Butler's The Fair Haven,remarking, however, that "those works suffer under the imperfection that they themselves are books, and nota whit less tautological than the others. A more reasonable, more inept, and more lazy man, I have chosen towrite notes on imaginary books."[69]

On the other hand, Borges was wrongly attributed some works, like the poem "Instantes".[70][71]

Criticism of Borges' work

Borges's change in style from regionalist criollismo to a morecosmopolitan style brought him much criticism from journals such asContorno, a left-of-centre, Sartre-influenced Argentine publicationfounded by David Viñas and his brother, along with otherintellectuals such as Noé Jitrik and Adolfo Prieto. In the post-Peronist Argentina of the early 1960s, Contorno met with wideapproval from the youth who challenged the authenticity of olderwriters such as Borges and questioned their legacy ofexperimentation. Magic realism and exploration of universal truths,they argued, had come at the cost of responsibility and seriousness inthe face of society's problems.[72] The Contorno writersacknowledged Borges and Eduardo Mallea for being "doctors oftechnique" but argued that their work lacked substance due to theirlack of interaction with the reality that they inhabited, anexistentialist critique of their refusal to embrace existence and realityin their artwork.[72]

Sexuality

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 14 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Jorge Luis Borges Monument inLisbon

With a few notable exceptions, women are almost entirely absent from the majority of Borges's fictionaloutput.[73] There are, however, some instances in Borges's writings of romantic love, for example the story"Ulrikke" from The Book of Sand. The protagonist of the story "El muerto" also lusts after the "splendid,contemptuous, red-haired woman" of Azevedo Bandeira[74] and later "sleeps with the woman with shininghair".[75] Although they do not appear in the stories, women are significantly discussed as objects ofunrequited love in his short stories "The Zahir" and "The Aleph".[76] The plot of La Intrusa was based on atrue story of two friends. Borges turned their fictional counterparts into brothers, excluding the possibility ofa homosexual relationship.[77]

Nobel Prize omission

Borges was never awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, something which continually distressed thewriter.[8] He was one of several distinguished authors who never received the honour.[78] Borgescommented, "Not granting me the Nobel Prize has become a Scandinavian tradition; since I was born theyhave not been granting it to me."[79] Some observers speculated that Borges did not receive the award in hislater life because of his conservative political views; or more specifically, because he had accepted anhonour from dictator Augusto Pinochet.[80][81]

Fact, fantasy and non-linearityMany of Borges's best-known stories deal with the nature of time("The Secret Miracle"), infinity ("The Aleph"), mirrors ("Tlön,Uqbar, Orbis Tertius") and labyrinths ("The Two Kings and the TwoLabyrinths", "The House of Asterion", "The Immortal", "The Gardenof Forking Paths"). Williamson writes, "His basic contention was thatfiction did not depend on the illusion of reality; what matteredultimately was an author’s ability to generate 'poetic faith' in hisreader."[8] His stories often have fantastical themes, such as a librarycontaining every possible 410-page text ("The Library of Babel"), aman who forgets nothing he experiences ("Funes, the Memorious"),an artifact through which the user can see everything in the universe("The Aleph"), and a year of still time given to a man standing beforea firing squad ("The Secret Miracle"). Borges also told realisticstories of South American life, of folk heroes, streetfighters, soldiers,gauchos, detectives, and historical figures. He mixed the real and thefantastic, fact with fiction. His interest in compounding fantasy,philosophy, and the art of translation are evident in articles such as"The Translators of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights". Inthe Book of Imaginary Beings, a thoroughly researched bestiary ofmythical creatures, Borges wrote, "There is a kind of lazy pleasure in useless and out-of-the-wayerudition."[82] Borges's interest in fantasy was shared by Bioy Casares, with whom he coauthored severalcollections of tales between 1942 and 1967.

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 15 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Often, especially early in his career, the mixture of fact and fantasy crossed the line into the realm of hoax orliterary forgery.[Notes 5]

"The Garden of Forking Paths" (1941) presents the idea of forking paths through networks of time, none ofwhich is the same, all of which are equal. Borges uses the recurring image of "a labyrinth that folds backupon itself in infinite regression" so we "become aware of all the possible choices we might make."[83] Theforking paths have branches to represent these choices that ultimately lead to different endings. Borges sawman's search for meaning in a seemingly infinite universe as fruitless and instead uses the maze as a riddlefor time, not space.[83] Borges also examined the themes of universal randomness and madness ("TheLottery in Babylon") and ("The Zahir"). Due to the success of the "Forking Paths" story, the term"Borgesian" came to reflect a quality of narrative non-linearity.[Notes 6]

Borgesian conundrum

The philosophical term "Borgesian conundrum" is named after him and has been defined as the ontologicalquestion of "whether the writer writes the story, or it writes him."[84] The original concept put forward byBorges is in Kafka and His Precursors—after reviewing works that were written before Kafka's, Borgeswrote:

If I am not mistaken, the heterogeneous pieces I have enumerated resemble Kafka; if I am notmistaken, not all of them resemble each other. The second fact is the more significant. In each ofthese texts we find Kafka's idiosyncrasy to a greater or lesser degree, but if Kafka had neverwritten a line, we would not perceive this quality; in other words, it would not exist. The poem"Fears and Scruples" by Browning foretells Kafka's work, but our reading of Kafka perceptiblysharpens and deflects our reading of the poem. Browning did not read it as we do now. In thecritics' vocabulary, the word 'precursor' is indispensable, but it should be cleansed of allconnotation of polemics or rivalry. The fact is that every writer creates his own precursors. Hiswork modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future."[85]

Culture and Argentine literature

Martín Fierro and Argentine tradition

Along with other young Argentine writers of his generation, Borges initially rallied around the fictionalcharacter of Martín Fierro. Martín Fierro, a poem by José Hernández, was a dominant work of 19th centuryArgentine literature. Its eponymous hero became a symbol of Argentine sensibility, untied from Europeanvalues – a gaucho, free, poor, pampas-dwelling.[86] The character Fierro is illegally drafted to serve at aborder fort to defend it against the indigenous population but ultimately deserts to become a gaucho matrero,the Argentine equivalent of a North American western outlaw. Borges contributed keenly to the avant gardeMartín Fierro magazine in the early 1920s.

As Borges matured, he came to a more nuanced attitude toward the Hernández poem. In his book of essayson the poem, Borges separates his admiration for the aesthetic virtues of the work from his mixed opinion ofthe moral virtues of its protagonist.[87] In his essay "The Argentine Writer and Tradition" (1951), Borgescelebrates how Hernández expresses the Argentine character. In a key scene in the poem, Martín Fierro and

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 16 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Borges in 1976

El Moreno compete by improvising songs on universal themes such as time, night, and the sea, reflecting thereal-world gaucho tradition of payadas, improvised musical dialogues on philosophical themes.[86][88]

Borges points out that Hernández evidently knew the difference between actual gaucho tradition ofcomposing poetry versus the "gauchesque" fashion among Buenos Aires literati.

In his works he refutes the arch-nationalist interpreters of the poem and disdains others, such as criticEleuterio Tiscornia, for their Europeanising approach. Borges denies that Argentine literature shoulddistinguish itself by limiting itself to "local colour", which he equates with cultural nationalism.[88] Racineand Shakespeare's work, he says, looked beyond their countries' borders. Neither, he argues, need theliterature be bound to the heritage of old world Spanish or European tradition. Nor should it define itself bythe conscious rejection of its colonial past. He asserts that Argentine writers need to be free to defineArgentine literature anew, writing about Argentina and the world from the point of view of those who have

inherited the whole of world literature.[88] Williamson says"Borges's main argument is that the very fact of writing fromthe margins provides Argentine writers with a specialopportunity to innovate without being bound to the canons ofthe centre, [...] at once a part of and apart from the centre,which gives them much potential freedom".[86]

Argentine culture

Borges focused on universal themes, but also composed asubstantial body of literature on themes from Argentinefolklore and history. His first book, the poetry collectionFervor de Buenos Aires (Passion for Buenos Aires), appearedin 1923. Borges's writings on things Argentine, includeArgentine culture ("History of the Tango"; "Inscriptions onHorse Wagons"), folklore ("Juan Muraña", "Night of theGifts"), literature ("The Argentine Writer and Tradition",

"Almafuerte"; "Evaristo Carriego"), and national concerns ("Celebration of the Monster", "Hurry, Hurry","The Mountebank", "Pedro Salvadores"). Ultranationalists, however, continued to question his Argentineidentity.[89]

Borges's interest in Argentine themes reflects, in part, the inspiration of his family tree. Borges had anEnglish paternal grandmother who, around 1870, married the criollo Francisco Borges, a man with amilitary command and a historic role in the Argentine Civil Wars in what is now Argentina and Uruguay.Spurred by pride in his family's heritage, Borges often used those civil wars as settings in fiction and quasi-fiction (for example, "The Life of Tadeo Isidoro Cruz," "The Dead Man," "Avelino Arredondo") as well aspoetry ("General Quiroga Rides to His Death in a Carriage"). Borges's maternal great-grandfather, ManuelIsidoro Suárez, was another military hero, whom Borges immortalized in the poem "A Page toCommemorate Colonel Suárez, Victor at Junín." The city of Coronel Suárez in the south of Buenos AiresProvince is named after him.

His non-fiction explores many of the themes found in his fiction. Essays such as "The History of the Tango"or his writings on the epic poem "Martín Fierro" explore Argentine themes, such as the identity of theArgentine people and of various Argentine subcultures. The varying genealogies of characters, settings, andthemes in his stories, such as "La muerte y la brújula", used Argentine models without pandering to his

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 17 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

readers or framing Argentine culture as "exotic".[89] In fact, contrary to what is usually supposed, thegeographies found in his fictions often do not correspond to those of real-world Argentina.[90] In his essay"El escritor argentino y la tradición", Borges notes that the very absence of camels in the Qur'an was proofenough that it was an Arabian work. He suggested that only someone trying to write an "Arab" work wouldpurposefully include a camel.[89] He uses this example to illustrate how his dialogue with universalexistential concerns was just as Argentine as writing about gauchos and tangos.

Multicultural Influences

At the time of the Argentine Declaration of Independence in 1816, the population was predominantly criollo(of Spanish ancestry). From the mid-1850s on waves of immigration from Europe, especially Italy andSpain, arrived in the country, and in the following decades the Argentine national identity diversified.[8][91]

Borges therefore was writing in a strongly European literary context, immersed in Spanish, English, French,German, Italian, Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse literature. He also read translations of Near Eastern and FarEastern works. Borges's writing is also informed by scholarship of Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, andJudaism, including prominent religious figures, heretics, and mystics.[92] Religion and heresy are explored insuch stories as "Averroes's Search", "The Writing of the God", "The Theologians", and "Three Versions ofJudas". The curious inversion of mainstream Christian concepts of redemption in the latter story ischaracteristic of Borges's approach to theology in his literature.

In describing himself, he said, "I am not sure that I exist, actually. I am all the writers that I have read, all thepeople that I have met, all the women that I have loved; all the cities that I have visited, all myancestors."[79] As a young man, he visited the frontier pampas which extend beyond Argentina into Uruguayand Brazil. Borges said that his father wished him "to become a citizen of the world, a great cosmopolitan,"in the way of Henry and William James.[93] Borges lived and studied in Switzerland and Spain as a youngstudent. As Borges matured, he traveled through Argentina as a lecturer and, internationally, as a visitingprofessor; he continued to tour the world as he grew older, finally settling in Geneva where he had spentsome of his youth. Drawing on the influence of many times and places, Borges's work belittled nationalismand racism.[89] Portraits of diverse coexisting cultures characteristic of Argentina are especially pronouncedin the book Six Problems for don Isidoro Parodi (co-authored with Bioy Casares) and the story "Death andthe Compass", which may or may not be set in Buenos Aires. Borges wrote that he considered Mexicanessayist Alfonso Reyes "the best prose-writer in the Spanish language of any time."[94]

Borges was also an admirer of some Oriental culture, e.g. the ancient Chinese board game of Go, aboutwhich he penned some verses,[95] while The Garden of Forking Paths had a strong oriental theme.

Influences

Modernism

Borges was rooted in the Modernism predominant in its early years and was influenced by Symbolism.[96]

Like Vladimir Nabokov and James Joyce, he combined an interest in his native culture with broaderperspectives, also sharing their multilingualism and inventiveness with language. However, while Nabokovand Joyce tended toward progressively larger works, Borges remained a miniaturist. His work progressed

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 18 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Plaque Jorge Luis Borges at 13 ruedes Beaux-Arts in Paris

away from what he referred to as "the baroque": his later style is far more transparent and naturalistic thanhis earlier works. Borges represented the humanist view of media that stressed the social aspect of art drivenby emotion. If art represented the tool, then Borges was more interested in how the tool could be used torelate to people.[61]

Existentialism saw its apogee during the years of Borges's greatestartistic production. It has been argued that his choice of topics largelyignored existentialism's central tenets. Critic Paul de Man notes,"Whatever Borges's existential anxieties may be, they have little incommon with Sartre's robustly prosaic view of literature, with theearnestness of Camus' moralism, or with the weighty profundity ofGerman existential thought. Rather, they are the consistent expansionof a purely poetic consciousness to its furthest limits."[97]

Political influences

As a political conservative, Borges "was repulsed by Marxism in theory and practice. Abhorringsentimentality, he rejected the politics and poetics of cultural identity that held sway in Latin America for solong."[98] As a universalist, his interest in world literature reflected an attitude that was also incongruentwith the Peronist Populist nationalism. That government's confiscation of Borges's job at the Miguel CanéLibrary fueled his skepticism of government. He labeled himself a Spencerian anarchist, following hisfather.[99][100]

Mathematics

The essay collection Borges y la Matemática (Borges and Mathematics, 2003) by Argentine mathematicianand writer Guillermo Martínez, outlines how Borges used concepts from mathematics in his work. Martínezstates that Borges had, for example, at least a superficial knowledge of set theory, which he handles withelegance in stories such as "The Book of Sand".[101] Other books such as The Unimaginable Mathematics ofBorges' Library of Babel by William Goldbloom Bloch (2008) and Unthinking Thinking: Jorge Luis Borges,Mathematics, and the New Physics by Floyd Merrell (1991) also explore this relationship.

Ancestry

Notes1. ^ Edwin Williamson suggests in Borges (Viking, 2004) that Borges did not finish his baccalauréat (pp. 79-80): "he

cannot have been too bothered about his baccalauréat, not least because he loathed and feared examination. (He wasnever to finish his high school education, in fact)."

2. ^ "His was a particular kind of blindness, grown on him gradually since the age of thirty and settled in for good afterhis fifty-eighth birthday." From Manguel, Alberto (2006) With Borges. London: Telegram Books pp. 15–16.

3. ^ The Borges poems in H. R. Hays, ed. (1943) 12 Spanish American Poets are "A Patio", "Butcher Shop","Benares", "The Recoleta", "A Day's Run", "General Quiroga Rides to Death in a Carriage", "July Avenue," and"Natural Flow of Memory".

4. ^ Notable translations also include work by Melville, Faulkner, Sir Thomas Browne, and G. K. Chesterton.

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 19 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

4. ^ Notable translations also include work by Melville, Faulkner, Sir Thomas Browne, and G. K. Chesterton.

5. ^ a b c His imitations of Swedenborg and others were originally passed off as translations, in his literary column inCrítica. "El teólogo" was originally published with the note "Lo anterior ... es obra de Manuel Swedenborg, eminenteingeniero y hombre de ciencia, que durante 27 años estuvo en comercio lúcido y familiar con el otro mundo." ("Thepreceding [...] is the work of Emanuel Swedenborg, eminent engineer and man of science, who during 27 years wasin lucid and familiar commerce with the other world.") See "Borges y Revista multicolor de los sábados:confabulados en una escritura de la infamia" by Raquel Atena Green in Wor(l)ds of Change: Latin American andIberian Literature Volume 32 2010 Peter Lang publishers, ISBN 978-0-8204-3467-4

6. ^ Non-linearity was key to the development of digital media. See Murray, Janet H. "Inventing the Medium" The NewMedia Reader. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003

References1. ^ Jozef, Bella. "Borges: linguagem e metalinguagem". In: O espaço reconquistado. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 1974,

p.43.

2. ^ a b Theo L. D'Haen (1995) "Magical Realism and Postmodernism: Decentering Privileged Centers", in: Louis P.Zamora and Wendy B. Faris, Magical Realism: Theory, History and Community. Duhan and London, DukeUniversity Press pp. 191–208.

3. ^ On his conference "Magical Realism in Spanish American" (Nova York, MLA, 1954), published later in Hispania,38 (2), 1955.

4. ^ In short, Borges's blindness led him to favour poetry and shorter narratives over novels. Ferriera, Eliane FernandaC. "O (In) visível imaginado em Borges". In: Pedro Pires Bessa (ed.). Riqueza Cultural Ibero-Americana. Campus deDivinópolis-UEMG, 1996, pp. 313–314.

5. ^ Borges on Life and Death (http://southerncrossreview.org/48/borges-barili.htm) Interview by Amelia Barili6. ^ (Portuguese) Masina, Lea. (2001) "Murilo Rubião, o mágico do conto". In: O pirotécnico Zacarias e outros

contos escolhidos. Porto Alegre: L & PM, p5.7. ^ Coetzee, J.M. "Borges's Dark Mirror", New York Review of Books, Volume 45, Number 16. October 22, 1998

8. ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Don’t abandon me" Tóibín, Colm London Review of Books 2006-05-11.(http://www.lrb.co.uk/v28/n09/toib01_.html) Retrieved 2009-04-19

9. ^ Harold Bloom (2004) Jorge Luis Borges (Bloom's biocritiques) Infobase Publishing ISBN 0-7910-7872-810. ^ Borges, Jorge Luis, "Autobiographical Notes", The New Yorker, 19 September 1970.11. ^ Borges and His Fiction: A Guide to His Mind and Art (http://books.google.co.uk/books?

id=oHzs8vuBQU8C&pg=PA16&dq=borges++Coll%C3%A8ge+de+Gen%C3%A8ve+baccalaur%C3%A9at&hl=en&sa=X&ei=G-PDULCbCMK30QXuroD4Dg&sqi=2&ved=0CDgQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=borges%20%20Coll%C3%A8ge%20de%20Gen%C3%A8ve%20baccalaur%C3%A9at&f=false) (1999) Gene H. Bell-Villada, University of Texas Press,p. 16 ISBN 9780292708785

12. ^ Wilson, Jason (2006). Jorge Luis Borges. Reaktion Books. p. 37. ISBN 1-86189-286-1.13. ^ Borges: Other Inquisitions 1937–1952. Full introduction by James Irby. University of Texas ISBN 978-0-292-

76002-8 (http://www.utexas.edu/utpress/excerpts/exboroth.html) Accessed 2010-08-1614. ^ "Ivonne Bordelois, "The Sur Magazine" Villa Ocampo Website"

(http://www.villaocampo.org/ing/historico/cultura_1.htm). Villaocampo.org. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 20 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

(http://www.villaocampo.org/ing/historico/cultura_1.htm). Villaocampo.org. Retrieved 2011-08-24.15. ^ Borges, Jorge Luis. Trans. Mildred Boyer and Harold Morland. Dreamtigers. University of Texas Press, 1985, p.

25.16. ^ Boldy (2009) p. 3217. ^ Bolter, Jay David; Joyce, Michael (1987). "Hypertext and Creative Writing" (http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?

id=317431). Hypertext '87 Papers. ACM. pp. 41–50.18. ^ Moulthrop, Stuart (1991). "Reading From the Map: Metonymy and Metaphor in the Fiction of 'Forking Paths' ". In

Delany, Paul; Landow, George P. Hypermedia and Literary Studies. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London,England: The MIT Press.

19. ^ "Borges, Jorge Luis (Vol.32)" (http://www.enotes.com/poetry-criticism/borges-jorge-luis). enotes. Retrieved 2008-12-03.

20. ^ Wardrip-Fruin, Noah & Montfort, Nick (2003). The New Media Reader. MIT Press.21. ^ , Alberto Manguel (2006) With Borges, London:Telegram Books pp. 15–16.22. ^ Woodall, J: The Man in Mirror of the Book, A Life of Luis Borges, (1996) Hodder and Stoughton pxxx.23. ^ "Days of Hate" (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0046947/). Imdb. Retrieved 2008-12-04.24. ^ Jorge Luis Borges (1984) Seven Nights, A New Directions Book pp 109-110.

25. ^ a b c d Burgin (1988) p xvii26. ^ "The Craft of Verse: The Norton Lectures, 1967-68" (http://www.ubu.com/sound/borges.html). UbuWeb: Sound.

Retrieved 1 January 2014.27. ^ H. R. Hays, ed. (1943) 12 Spanish American Poets. New Haven: Yale University Press p118-139.28. ^ Jeffrey Alan Marks (2008) Anthony Boucher: A Biobibliography McFarland publishers, p77 ISBN 978078643320929. ^ Borges, Jorge Luis (1998) Collected Fictions Viking Penguin. Translation and notes by Andrew Hurley. Editorial

note p 517.30. ^ Edgar Awards (http://theedgars.com/edgarsDB/index.php)31. ^ UVA, Special Collections Library. http://www2.lib.virginia.edu/small/collections/borges/32. ^ Montes-Bradley, Eduardo. "Cada pieza es de un valor incalculable" Cover Article. Revista Ñ, Diario Clarin.

Buenos Aires, September 5th, 2011.33. ^ Norman Thomas Di Giovanni, The Lessons of the Master34. ^ "Fanny", El Señor Borges35. ^ Israel Shenker (April 6, 1971). "Borges, a Blind Writer With Insight"

(http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/08/31/reviews/borges-insight.html). New York Times. Retrieved 30 April 2013."Being an agnostic means all things are possible, even God, even the Holy Trinity. This world is so strange thatanything may happen, or may not happen. Being an agnostic makes me live in a larger, a more fantastic kind ofworld, almost uncanny. It makes me more tolerant."

36. ^ María Kodama demanda a un periodista francés por difamación y reclama nada más que 1 euro(http://edant.revistaenie.clarin.com/notas/2008/05/14/01671869.html)

37. ^ Se suspendió un juicio por obras de Borges: reacción de Kodama(http://edant.revistaenie.clarin.com/notas/2008/05/15/01672570.html)

38. ^ (Spanish) Octavi Martí, Kodama frente a Borges, El País (Madrid), Edición Impresa, 16 August 2006. Abstractonline (http://www.elpais.es/articulo/revista/agosto/Kodama/frente/Borges/elpporcul/20060816elpepirdv_1/Tes); fulltext accessible online by subscription only.

39. ^ Richard Flanagan, "Writing with Borges",

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 21 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

(http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2003/07/12/1057783281684.html)The Age (Australia), 12 July 2003. Accessed2010-08-16

40. ^ Burgin (1968). p. 104.41. ^ Edwin Williamson, Borges: A Life, pp. 332–333.42. ^ Burgin (1968) pp. 95–6

43. ^ a b De Costa, René (2000) Humor in Borges (Humor in Life & Letters). Wayne State University Press p. 49 ISBN0-8143-2888-1

44. ^ Jorge Luis Borges, Selected Nonfictions, p 200.45. ^ Selected Nonfictions, page 201.46. ^ Borges, Selected Nonfictions, page 211.47. ^ Burgin (1968), pp 31-332.48. ^ Williamson (2004) p. 29249. ^ Williamson (2004) p. 29550. ^ Williamson (2004) p. 312

51. ^ a b Williamson (2004) p. 31352. ^ Williamson (2004) p. 320.53. ^ Williamson (2004) pp. 320-321.54. ^ (Spanish) Jorge Luis Borges. Galería de Directores, Biblioteca Nacional (Argentina)

(https://web.archive.org/web/20080416034854/http://www.bibnal.edu.ar/paginas/galeriadirec.htm#borges) at theWayback Machine (archived April 16, 2008). (archived from the original(http://www.bibnal.edu.ar/paginas/galeriadirec.htm#borges), on 16 April 2008.)

55. ^ Jorge Luis Borges, Selected Nonfictions, p. 410.56. ^ Burgin (1969), p 121

57. ^ a b National Geographic, March 1975. p. 303.

58. ^ a b Williamson (2004) p. 49159. ^ Willis Barnstone, With Borges on an Ordinary Evening in Buenos Aires, University of Illinois Press, 1993. pp. 30-

31.60. ^ Falkland Islands: Imperial pride (http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/feb/19/falkland-islands-

editorial)

61. ^ a b Wardrip-Fruin, Noah, and Nick Montfort, ed. (2003). The New Media Reader. Cambridge: The MIT Press,p. 29. ISBN 0-262-23227-8

62. ^ Borges, Jorge Luis. (1994) Siete Noches. Obras Completas, vol. III. Buenos Aires: Emecé63. ^ Unthinking Thinking: Jorge Luis Borges, Mathematics, and the New Physics (1991) Floyd Merrell, Purdue

University Press pxii ISBN 978155753011064. ^ New York Times May 7, 1972 "The Other Borges Than the Central One"

(http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/08/31/reviews/borges-brodie.html)65. ^ Reading Borges After Benjamin: Allegory, Afterlife, and the Writing of History (2008) Kate Jenckes, SUNY Press,

p136, p117, p101, p136 ISBN 978079146990366. ^ Kristal, Efraín (2002). Invisible Work. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-8265-1408-1.67. ^ Jorge Luis Borges, This Craft of Verse, Harvard University Press, 2000. pp. 57–76. Word Music and Translation,

Lecture, Delivered February 28, 1968.

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 22 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

68. ^ Borges This Craft of Verse (p104)69. ^ Borges Collected Fictions, p6770. ^ University of Pittsburgh, Borges Center (http://www.borges.pitt.edu/bsol/iainst.php) Jorge Luis Borges, autor del

poema "Instantes", by Iván Almeida. Retrieved January 10, 201171. ^ Internetaleph (http://www.internetaleph.com/detail/showdetail.asp?objtype=4&objid=4&langid=en&pid=74),

Martin Hadis' site on The Life & Works of Jorge Luis Borges. Retrieved January 10, 2011

72. ^ a b Katra, William H. (1988) Contorno: Literary Engagement in Post-Perónist Argentina. Teaneck, NJ: FairleighDickinson UP, pp. 56–57

73. ^ The Queer Use of Communal Women in Borges's "El muerto" and "La intrusa", paper presented at XIX LatinAmerican Studies Association (LASA) Congress held in Washington DC in September 1995.

74. ^ Hurley, Andrew (1988) Jorge Luis Borges: Collected Fictions. New York: Penguin p197.75. ^ Hurley, Andrew (1988) Jorge Luis Borges: Collected Fictions. New York: Penguin p20076. ^ Hurley, Andrew 1988) Jorge Luis Borges: Collected Fictions. New York: Penguin77. ^ Keller, Gary; Karen S. Van Hooft (1976). "Jorge Luis Borges's `La intrusa:' The Awakening of Love and

Consciousness/The Sacrifice of Love and Consciousness.". In Eds. Lisa E. Davis and Isabel C. Tarán. The Analysisof Hispanic Texts: Current Trends in Methodology. Bilingual P. pp. 300–319.

78. ^ Feldman, Burton (2000) The Nobel Prize: a History of Genius, Controversy and Prestige, Arcade Publishing p57

79. ^ a b Guardian profile. "Jorge Luis Borges" 22 July 2008(http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/jun/10/jorgeluisborges). Accessed 2010-08-15

80. ^ "Briton Wins the Nobel Literature Prize." James M. Markham. The New York Times 7 October 1983(http://www.nytimes.com/1983/10/07/books/83nobel.html). Accessed 2010-08-15

81. ^ Feldman, Burton (2000) The Nobel Prize: a History of Genius, Controversy and Prestige, Arcade Publishing p8182. ^ Borges, Luis Borges (1979) Book of Imaginary Beings Penguin Books Australia p. 11 ISBN 0-525-47538-9

83. ^ a b Murray, Janet H. "Inventing the Medium" The New Media Reader. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.84. ^ Ella Taylor (July 18, 2010). "Book review: The Thieves of Manhattan by Adam Langer". Los Angeles Times.85. ^ Jorge Luis Borges (February 1988). Labyrinths: Selected Stories & Other Writings. New Direction Books. p. 201.

86. ^ a b c Gabriel Waisman, Sergio (2005) Borges and Translation: The Irreverence of the Periphery BucknellUniversity Press pp. 126–9 ISBN 0-8387-5592-5

87. ^ Borges and Guerrero (1953) El "Martín Fierro ISBN 84-206-1933-7

88. ^ a b c Borges, Jorge Luis and Lanuza, Eduardo González (1961) "The Argentine writer and tradition" LatinAmerican and European Literary Society

89. ^ a b c d Takolander, Maria (2007) Catching butterflies: bringing magical realism to ground Peter Lang Pub Inc pp.55–60. ISBN 3-03911-193-0

90. ^ David Boruchoff (1985), “In Pursuit of the Detective Genre: ‘La muerte y la brújula’ of Jorge Luis Borges,” Inti:Revista de Literatura Hispánica no. 21, pp. 13-26.

91. ^ "Velez, Wanda (1990) ''South American Immigration: Argentina''. Yale University, New Haven Teachers Institute"(http://www.yale.edu/ynhti/curriculum/units/1990/1/90.01.06.x.html). Yale.edu. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

92. ^ Bell-Villada, Gene Borges and His Fiction: A Guide to His Mind and Art(http://www.utexas.edu/utpress/excerpts/exbelbor.html) University of Texas Press ISBN 978-0-292-70878-5

93. ^ Williamson, Edwin (2004). Borges: a life. Viking. p. 53. ISBN 0-670-88579-7.94. ^ Borges Siete Noches, p156

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 23 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

94. ^ Borges Siete Noches, p15695. ^ "El Go" (http://gobase.org/reading/stories/?id=12). GoBase. Retrieved 26 August 2011.96. ^ Britton, R (July 1979). "History, Myth, and Archetype in Borges's View of Argentina". The Modern Language

Review (Modern Humanities Research Association) 74 (3): 607–616. doi:10.2307/3726707(http://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F3726707). JSTOR 3726707 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/3726707).

97. ^ de Man, Paul. "A Modern Master", Jorge Luis Borges, Ed. Harold Bloom, New York: Chelsea House Pub, 1986. p.22.

98. ^ New york Times Article. Paid Subscription only(http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/08/31/reviews/970831.31gonz01.html)

99. ^ Yudin, Florence (1997). Nightglow: Borges' Poetics of Blindness. City: Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca.p. 31. ISBN 84-7299-385-X.

100. ^ Bell-Villada, Gene (1981). Borges and His Fiction. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 13.ISBN 0-8078-1458-X.

101. ^ Martinez, Guillermo (2003) Borges y la Matemática (Spanish Edition) Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires.ISBN 950-23-1296-1

102. ^ Boldy, Steven. A Companion to Jorge Luis Borges. Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2009. pp. 9–14. ISBN 9781855661899

Further readingAgheana, Ion (1988). The Meaning of Experience in the Prose of Jorge Luis Borges. Frankfurt Am Main: P. Lang.ISBN 0-8204-0595-7.Agheana, Ion (1984). The Prose of Jorge Luis Borges. Frankfurt Am Main: P. Lang. ISBN 0-8204-0130-7.Aizenberg, Edna (1984). The Aleph Weaver: Biblical, Kabbalistic and Judaic Elements in Borges. Potomac: ScriptaHumanistica. ISBN 0-916379-12-4.Aizenberg, Edna (1990). Borges and His Successors. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-0712-X.Alazraki, Jaime (1988). Borges and the Kabbalah. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30684-1.Alazraki, Jaime (1987). Critical Essays on Jorge Luis Borges. Boston: G.K. Hall. ISBN 0-8161-8829-7.Balderston, Daniel (1993). Out of Context. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1316-2.Barnstone, Willis (1993). With Borges on an Ordinary Evening in Buenos Aires. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.ISBN 0-252-01888-5.Barrenechea, Ana María (1965 LC 65-10764). Borges the Labyrinth Maker. Edited and Translated by Robert Lima.New York City: New York University Press.Bell-Villada, Gene (1981). Borges and His Fiction. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1458-X.Bioy Casares, Adolfo (2006). Borges. City: Destino Ediciones. ISBN 978-950-732-085-9.Bloom, Harold (1986). Jorge Luis Borges. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-87754-721-1.Bulacio, Cristina; Grima, Donato (1998). Dos Miradas sobre Borges. Buenos Aires: Ediciones de Arte Gaglianone.ISBN 950-554-266-6. Illustrated by Donato Grima.Burgin, Richard (1969) Jorge Luis Borges: Conversations, Holt Rhinehart WinstonBurgin, Richard (1998) Jorge Luis Borges: Conversations, University Press of MississippiDe Behar, Block (2003). Borges, the Passion of an Endless Quotation. Albany: State University of New York Press.ISBN 1-4175-2020-5.Di Giovanni, Norman Thomas (1995). The Borges Tradition. London: Constable in association with the Anglo-

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 24 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Di Giovanni, Norman Thomas (1995). The Borges Tradition. London: Constable in association with the Anglo-Argentine Society. ISBN 0-09-473840-8.Di Giovanni, Norman Thomas (2003). The Lesson of the Master. London: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-6110-7.Dunham, Lowell (1971). The Cardinal Points of Borges. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0983-1.Fishburn, Evelyn (2002). Borges and Europe Revisited. City: Univ of London. ISBN 1-900039-21-4.Frisch, Mark (2004). You Might Be Able to Get There from Here. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.ISBN 0-8386-4044-3.Kristal, Efraín (2002). Invisible Work. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 0-585-40803-3.Laín Corona, Guillermo. "Borges and Cervantes: Truth and Falsehood in the Narration”. Neophilologus, 93 (2009):421-37.Laín Corona, Guillermo. "Teoría y práctica de la metáfora en torno a Fervor de Buenos Aires, de Borges”.Cuadernos de Aleph. Revista de literatura hispánica, 2 (2007): 79-93.http://cuadernosdealeph.com/revista_2007/A2007_pdf/06%20Teor%C3%ADa.pdfLima, Robert (1993). "Borges and the Esoteric". Crítica hispánica. Special issue (Duquesne University) 15 (2).ISSN 0278-7261 (https://www.worldcat.org/issn/0278-7261).Lindstrom, Naomi (1990). Jorge Luis Borges. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-8327-X.Manguel, Alberto (2006). With Borges. City: Telegram. ISBN 978-1-84659-005-4.Manovich, Lev, New Media from Borges to HTML, 2003 (http://www.newmediareader.com/book_samples/nmr-intro-manovich-excerpt.pdf)McMurray, George (1980). Jorge Luis Borges. New York: Ungar. ISBN 0-8044-2608-2.Molloy, Sylvia (1994). Signs of Borges. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1406-1.Murray, Janet H., Inventing the Medium, 2003 (http://www.newmediareader.com/book_samples/nmr-intro-murray-excerpt.pdf)Núñez-Faraco, Humberto (2006). Borges and Dante. Frankfurt Am Main: P. Lang. ISBN 978-3-03910-511-3.Racz, Gregary (2003). Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) as Writer and Social Critic. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press.ISBN 0-7734-6904-4.Rodríguez, Monegal (1978). Jorge Luis Borges. New York: Dutton. ISBN 0-525-13748-3.Rodríguez-Luis, Julio (1991). The Contemporary Praxis of the Fantastic. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8153-0101-4.Sarlo, Beatriz (2007). Jorge Luis Borges: a Writer on the Edge. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-84467-588-3.Shaw, Donald (1992). Borges' Narrative Strategy. Liverpool: Francis Cairns. ISBN 0-905205-84-7.Stabb, Martin (1991). Borges Revisited. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-8263-X.Sturrock, John (1977). Paper Tigers. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-815746-0.Todorov, Tzvetan (1970). Introduction à la littérature fantastique. Paris: Seuil.Toro, Alfonso (1999). Jorge Luis Borges. Frankfurt Am Main: Vervuert. ISBN 3-89354-217-5.Volek, Emil (1984). "Aquiles y la Tortuga: Arte, imaginación y realidad según Borges". In: Cuatro claves para lamodernidad. Analisis semiótico de textos hispánicos. Madrid.Waisman, Sergio (2005). Borges and Translation. Lewisburg Pa.: Bucknell University Press. ISBN 0-8387-5592-5.Williamson, Edwin (2004). Borges: A Life. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-88579-7.Wilson, Jason (2006). Jorge Luis Borges. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-286-7.Woscoboinik, Julio (1998). The Secret of Borges. Washington: University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-1238-5.Mualem, Shlomy (2012). Borges and Plato: A Game with Shifting Mirrors. Madrid and Frankfurt:

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 25 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

Iberoamericana/Vervuert. ISBN 978-8484895954.

Documentaries

Eduardo Montes-Bradley (Writer/Director) (1999). Harto The Borges (Feature Documentary). USA: Patagonia FilmGroup, US.Ricardo Wullicher (Director) (1978). Borges para millones (Feature Documentary). Argentina.David Wheatley (Director) (1983). Profile Of A Writer: Borges and I (http://ubu.com/film/borges_portrait.html)(Feature Documentary). Arena.

External links

Jorge Luis Borges (http://www.dmoz.org/Arts/Literature/Authors/B/Borges%2C_Jorge_Luis/) atDMOZWorks by Jorge Luis Borges on Open Library at the Internet ArchiveRonald Christ (Winter–Spring 1967). "Jorge Luis Borges, The Art of Fiction No. 39"(http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4331/the-art-of-fiction-no-39-jorge-luis-borges). ParisReview.BBC Radio 4 discussion programme (http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0076182) from In our time.(Audio 45 mins)Jorge Luis Borges at The Modern Word (http://www.themodernword.com/borges/index.html)Borges Center, University of Pittsburgh (http://www.borges.pitt.edu/).The Friends of Jorge Luis Borges Worldwide Society & Associates (http://amigos-de-borges.net/site/english/main/)

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jorge_Luis_Borges&oldid=617412936"Categories: Jorge Luis Borges 1899 births 1986 deaths Classical liberals Argentine agnosticsArgentine anti-fascists Argentine anti-communists Argentine people of English descentArgentine essayists Argentine librarians Argentine people of Portuguese descentArgentine people of Spanish descent Argentine people of Uruguayan descent Argentine poetsArgentine short story writers Argentine translators Argentine writers Argentine writers in FrenchArgentine screenwriters Blind people from Argentina Blind writers Burials at Cimetière des RoisCancer deaths in SwitzerlandCommanders Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of GermanyDeaths from liver cancer Edgar Award winners English–Spanish translators Hyperreality theoristsJerusalem Prize recipients Latin American people of British descent Légion d'honneur recipientsKnights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Writers from Buenos Aires Postmodern writersPremio Cervantes winners Prix mondial Cino Del Duca winners French–Spanish translators

31/07/2014 21:14Jorge Luis Borges - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Page 26 of 26http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorge_Luis_Borges

German–Spanish translators Translators from Old English Translators from Old NorseTranslators to Spanish Translators of Edgar Allan Poe Translators of Franz Kafka20th-century Argentine writers