Johnson, Jean - The Huapango. a Mexican Song Contest

-

Upload

sonmexicano -

Category

Documents

-

view

36 -

download

3

Transcript of Johnson, Jean - The Huapango. a Mexican Song Contest

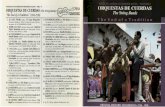

The Huapango: A Mexican Song ContestAuthor(s): Jean B. JohnsonSource: California Folklore Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Jul., 1942), pp. 233-244Published by: Western States Folklore SocietyStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1495742Accessed: 17/01/2010 22:36

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available athttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and youmay use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained athttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=wsfs.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printedpage of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Western States Folklore Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toCalifornia Folklore Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

The Huapango: A Mexican Song Contest

JEAN B. JOHNSON

THE EASTERN COASTAL region of Mexico, comprising principally the modern state of Veracruz, is one of the most sharply definable musical areas of Middle America. The music of this region contrasts clearly with, say, that of the West Coast, the typical product of which is the mariachi corrido (ballad), of Jalisco, and likewise contrasts with that of other

regions. In Veracruz itself there are several rather sharply defined musical

subareas. In the northern part of the state, in the region known as la Huasteca, the characteristic song style is represented by the cancion huasteca, sung in minor keys. In the southern areas, the huapango has its focus in the river or coastal towns of Medellin, Alvarado, Tlacotalpan, and formerly, in the city of Vera Cruz itself.

In recent times, the term huapango has been indiscriminately used for the musical style of the entire Mexican Atlantic seaboard. In a modified form, the style has spread throughout Mexico, to places as far away from the coast as Jalisco and Sinaloa. The songs of the interior often bear only a slight resemblance to the true huapango. In the i9th century, the

huapango had its only focus in this coastal region, but the almost com-

plete lack of evidence prevents me from outlining the entire area of its typical occurrence. As a musical style, its closest affinities are with Cuban and Caribbean song. The huapango can be legitimately treated as a culture-complex, or association of cultural elements.

The verses of the huapango are sung while a vigorous, stamping, heel- and-toe dance is in progress. Both men and women participate in the dance, and although the partners face each other, the movements of each are executed more or less independently. The dance is performed on a

rectangular platform, elevated perhaps a foot from the ground. The plat- form acts as a sounding board, in the manner of a "foot-drum." It is built

especially for the purpose, and is usually village property. The dance (fandango) is held outdoors on Saturday nights or on special festive occa- sions.

[233]

CALIFORNIA FOLKIORE QUARTERLY

A full musical accompaniment consists of harp, violin, guitar, jarana,' maracas,2 and rasps of various sorts. The selections played are traditional melodies and rhythms; any number of improvised verses may be set to such a son as Pdjaro Cut. The noisy jarana and the harp are the very heart of the huapango and the music of the region. Circumstances may reduce the instrumental ensemb-le to guitar and jarana, and in recent years harpists have decreased rapidly in numbers. Medellin was formerly famous for its harpists; today one would be hard put to find more than two or three in the entire township.

As the dance is in progress, anyone who feels inclined may sing his verses. The verse may be a clever new composition which the singer wishes to present for public approval; it may be of a more topical nature,

teasing or even insulting one of the dancers or spectators, or it may be a declaration of love. Verse 19, for example, is a barb directed at a man from a neighboring town who was attempting to steal the singer's sweetheart. One may be sure that such a verse would not go unanswered. Other verses are humorous and amorous in content, or complain of a sweetheart's fickleness. The verses are characteristically sung in a falsetto voice, a sort of modified flamenco technique.

The exchange of the barbs of verse may continue until one or the other of the contestants runs out of both wit and verse, to his chagrin and the vast amusement of the spectators. Both men and women participate in the contest, and contests with three contestants, generally a woman and two would-be suitors, are not uncommon. It is hardly necessary to add that these contests frequently become heated, and often end tragically in a flash of daggers beside the river. One singer boasts publicly, however, that he offended none with his verses (Verse 17).

A girl's popularity is often gauged by the number of verses sung to her, or about her, at the fandango. Regrettably, the old-style huapango is

rapidly passing away, and the younger people no longer have the verse-

making interest or ability of the older generation. The flowing and flounced creole costume of the Jarochas' is now seen rarely outside of carnival time.

Certain persons enjoy a wide reputation as wits and versemakers. These have at their command a large stock of verses and couplets which are prac-

1A stringed instrument approximately one-half the size of a tenor guitar, with six gut strings. It produces a very strident sound, and frequently carries the melody.

2 Gourd and calabash rattles. 3 Jarocho; in some parts of Spain, a brusque, somewhat insolent person; Mex., a native of

the coast of Veracruz.

234

A MEXICAN SONG CONTEST 235

tically public property. By rearranging these materials, and adding a line here and there, a verse suitable for each occasion can rapidly be impro- vised. Occasionally, the singer may rework a series of lines to form a two or three-verse lyric passage (33a, b), or in songs like "La Iguana," (the Iguana), and "El Gavilan" (the Hawk), verses may be put together and

arranged so as to tell a story. Frequently the versemaker's rhyme fails him, leaving irregularities

and rough spots, which he tries to conceal as skillfully as possible by his

delivery (cf. Verse 5, 2; 23, 4; 30, 2). Often the entire verse makes little actual "sense," but employs large, meaningless, or obscure words which the illiterate composer has devised (cf. Verses 16 [desinquieta], 37). "Per-

haps the words don't mean much," says El Chiquito, a famous singer, "but

they sound so nice, don't you think?"

Although conclusive evidence cannot be presented here, the song con- test is, of course, a common European trait, and is widespread in Spain. The Basque form is known as the bertsolari (versolari).' The song contest seems to occur in the New World wherever lasting centers of Hispanic culture were established. In Venezuela, the joropo seems very similar to the huapango,' while in the Argentinian region the style is represented by the famous payador, which forms an integral part of Rojas' concept of the Gauchesco.6

There can be no doubt that the huapango complex was a Spanish intro- duction into Mexico at a very early date, especially as it relates to the song contest, versemaking, verse forms, and musical aspects. The dance and the plank platform have been casually cited as having an African or Carib- bean origin. Although no proof of this can be adduced at the present time, an African origin of these features remains a possibility in coastal Veracruz, which was a center of slave importation from the early part of the i6th century. The present population shows definite negroid physi- cal characteristics. In the Veracruz area, the Indian groups surrounding the mestizo population of the coast have accepted principally the dance, the dance platform, jarana, guitar, and a simplified form of the music. The harp rarely occurs; women do not ordinarily dance. The song contest, with improvisation of verses, is lacking among monolingual Indian com-

4 Personal communication from Mr. Juan Bilbao. 6 Ibarra, T., Young Man of Caracas (1941), p. 129. 6Rojas, R., La Literature Argentina (Madrid, 1924), vols. 1 and 2, gauchescos, passim;

Salaverria, J. M., Vida de Martin Fierro, chap. 13, El Payador Siniestro (Madrid, 1934); Hernandez, J., Martin Fierro.

CALIFORNIA FOLKLORE QUARTERLY

munities, or is much reduced in communities with a small mestizo popu- lation residing among the Indians.7

An Aztec derivation has been proposed for the word huapango, but no

etymological demonstration has been made.8 A Nahuatl source is not

likely, but it is safest to leave the question open. One may safely recognize the probability that the huapango complex, as it exists today, fuses ele- ments from several sources.

The following verses were collected in 1941 in the town of Tlacotalpan, Veracruz, situated on the Papaloapan River (Nahuatl; river of the butter-

flies), some thirty kilometers above its mouth. The Spanish town was founded in the i6th century on the site of an earlier aboriginal settlement. It is famous for its music, and has produced many noteworthy poets and

musicians, among whom may be mentioned the contemporary Mexican musicians Agustin Lara, Lorenzo Barcelata, and the singer "Tofia la

Negra." There are no Indians in the town. The informants were two elderly men, Encarnaci6n Cruz (Verses 1-24),

and Feliz Ordofiez Montiel (Verses 35-41), nicknamed El Chiquito ("Tiny") because of his tallness. Lola Malpica, an elderly woman, dic- tated verses 25-32. It is interesting to note that Lola took the idea of El

Chiquito's verse (33a, b), and reworked it to fit a particular occasion

(Verse 28).' The three informants enjoy great local reputation as poets and wits.

1. Baj6 un angel de alla arriba, Directo a un consejo darme, Lo guardare mientras viva, Nunca intentare casarme, Porque a mi <que me motiva, Siendo libre, cautivarme?

An angel came down from on high to give me a piece of advice, which I shall keep as long as I live-never do I intend to marry, because, what should moti- vate me, being free, to make a captive of myself?

7These remarks refer to the huapango among such people as the Chinantec of the village of Chiltepec on the upper Papaloapan, and to the Popoluca communities in the vicinity of Lake Catemaco in southern Veracruz. See Foster, G., Notes on the popoluca, Publ. No. 51 of the Inst. Panam. de Geo. e Hist., M6xico, 1940.

8 Divila Garibi, I., Del Nahuatl al Espaiiol (Mexico, 1939), p. 360. 9 Mr. John H. Green accompanied the writer and recorded electrically a good sampling of

the music.

236

A MEXICAN SONG CONTEST

2. Yo pretendi a una de edad, Por experimentar mi suerte, Y me dijo, "iVen acai!"

"No puedo corresponderte", "iMira lo viejo que estas", "Y asi un amor ni divierte!".

I courted an elderly woman, just to try my luck. She said to me, "Come here! I can't return your affection. Look how old you are! Such an affair isn't even amusing!"

3. No de cobarde me quejo, Muchachos, pongan sentido, El que ame que haga reflejo, Porque yo estoy convencido, Que el que ya va para viejo, De todo es aborrecido.

Not from cowardice do I complain. Boys, consider! Let him who loves re- flect, because I am convinced that he who is growing old is bored with every- thing. 4. El coraz6n se me entume,

Cada vez que llego al huerto, El alma se me consume, Mi cuerpo se queda inerto, Al respirar el perfume, De un bot6n recien abierto.

My heart grows torpid whenever I arrive at the orchard. My soul consumes me, my body remains inert when I smell the perfume of a newly-opened bud.

5. Hasta el trono de Cupido, Me subi para devisarte, Hagame el favor que yo te pido,'? Que hagas lugar para hablarte, No sea que muera sentido, Y despues venga a asustarte.

Up to the throne of Cupid I climbed to see you. Do me the favor that I beg of you! Let me speak to you. Let it not be that I should die suffering, and afterward come to frighten you!

6. Los dedos no son parejos, Puedes tomar la medida, No te lleves de consejo, Ni de lo que otro te diga, Porque aunque mi amor viva lejos, Pero de ti no se olvida.

The fingers are not even-you may take their measure. Don't take as advice even that which another might tell you, because even though (I and) my love should live afar, it (my love) would not forget you.

10 Correct form, hazme.

237

CALIFORNIA FOLKLORE QUARTERLY

7. Me subi a un alto pino, Por ver si te devisaba, Y como el pino era fino, De verme llorar, lloraba.

I climbed a tall pine, trying to look for you. And since the pine was fine, see- ing me weep, it wept.

8. Me subi como la guia, Hasta el ultimo elemento, Y puse mi escribania, En las salas del silencio, No hay pluma como la mia.

I ascended like the guide, up to the last element, and put my writing desk in the halls of silence. There is no pen like mine.

9. Aunque me priven de verte, En mi amor no han de privar, S61o la palida muerte, Es la que me ha de quitar, Que yo deje de quererte.

Even though they deprive me of seeing you, they cannot deprive me of my love; only pale death can keep me from wanting you.

io. Una carta te escribi, Y no me la has contestado, Compadecete de mi, Porque estoy apasionado, Desde aquel dia que te vi.

I wrote you a letter, and you have not answered. Pity me, because I am im- passioned, since that day I saw you.

11. No se cual sera el motivo, Que tu no me puedes ver, Siendo yo tu preferido, Dime, Cdesprecias, mujer, Porque me ves abatido?

I do not know why you will not see me, since I am your chosen one. Tell me, woman, do you despise me because you see me downcast?

12. Hasta aca me di6 el olor, Del agua que te has echado, No se si sera la flor, Que cargas en tu peinado, O la ilusi6n del amor, Que me trae apasionado.

Even here the odor of the water with which you sprinkled yourself reaches me. I do not know if it is the flower which you carry in your hair which bears me impassioned, or if it is the illusion of love.

238

A MEXICAN SONG CONTEST

13. Vida mia, me has despreciado, Siendo el angel de tu imagen, Pero no estoy fastidiado, En ver tus crueles pasajes, Porque Dios me ha destinado, Para rendirte homenajes.

My life, you have despised me; I, who am the angel of your image. But I am not exasperated when I see your cruel passages, because God has destined me to render you homage.

14. Pretendi a una jovencita, De trece afnos, muy graciosa, Yo la pretendi chiquita, Porque comprendi una cosa, Que el que corta flor tiernita, Todo el perfume lo goza.

I courted a very young and graceful girl of thirteen years. I courted her young because I understood one thing; he who plucks a budding flower enjoys all the perfume.

15. Te amo con carifio firme, Pero tu te me engrandeces, Hazme favor de decirme, Si mi amor no te mereces, Por eso deseo morirme, Todos los dias que amanece.

I love you with firm affection, but you are "getting big on me." Do me the favor of telling me if you don't merit my love; because of that, I want to die every day at dawn.

16. Quisiera ser la peineta, Que nevega en tus cabellos, Pero mas me desinquieta, Esos ojitos tan bellos, Que le he de seguir la veta, Hasta quedarme con ellos.

I should like to be the comb which navigates in your hair, but more exciting are those beautiful little eyes. I shall follow their path until I remain with them.

17. En mi juventud cumplida, Bastante gusto me di, Cante la Pascua Florida, Pero a ninguno ofendi, Porque veo que en esta vida, Todo tiene su hasta alli.

In my completed youth, I had plenty of fun. I sang the flowery Easter, but offended none, because I see that in this life, you can go so far and no farther.

239

CALIFORNIA FOLKLORE QUARTERLY

i8. De que sirve tu amor, Corresponde a mi carifio? Si me niegas el fulgor, Que yo ocasiones te rifio, Que me regales la flor, Que te vi, siendo un nifio.

What good is your love to me if you refuse me the warmth and the flower that I saw in you when I was a boy, when I demand them of you? (meaning obscure).

19. Si eres buena Mexicana, No consientas ese intento, Que este quiere carne humana, No pretiende casamiento, Tiene una novia en Santana Pedida hace mucho tiempo.

If you are a good Mexican girl, you won't permit his intention, for this fellow wants human meat. He doesn't offer marriage; he has had a sweetheart in Santana betrothed to him for a long time.

20. Dicen que me han de quitar, Las veredas por donde ando, Todito me han de quitar, Y todito ire dejando, Pero dejarte de amar, S6lo Dios sabra hasta cuando.

They say they are going to take away from me the paths on which I walk. Everything they will take from me, and everything I would leave-but to cease loving you, only God knows when!

21. Me han de quitar el riego, El agua, el fuego, y el viento, Me quitaran mis intentos, Eso es lo que no consiento.

They are going to take away from me the irrigation water, the fire, and the wind. That they should take away my intentions, to that I won't agree.

22. El coraz6n traigo herido, De una pasi6n importuna, Lo que jamas he creido, Que me quiera bien ninguna, Porque en el amor he sido, Hombre de mala fortuna.

I bear a wounded heart from an unfortunate passion. I have never believed that anyone would love me well, since I have been an unfortunate man in love affairs.

240

A MEXICAN SONG CONTEST

23. Cuando yo era tu querer, Mi nombre era muy nombrado, Hoy que no me puedes ver, Hasta mis letras borradas, Pero en fin que hemos de hacer, Si naci para desgraciado.

When I was your love, my name was very famous. Now that you won't see me, even the letters are erased (of my name). But, after all, what can we do, if I was born to be unfortunate.

24. Un dia de mucho pensar, Cogi el camino y me fui, Y dije a poquito andar,

"iQue desgraciado nacil", Y me volvi a regresar, Acordaindome de ti.

Thinking long one day, I took the road and went away. After walking a bit, I said, "What a miserable fellow I was born to bel," and I turned to return, thinking of you.

25. Ya me voy, ya no me voy, Ya me pongo el pie en el estribo, (Muchacho Tlacotalpefio, Quien quiere ir conmigo?

I am on my way, I am not on my way, I am already putting my foot to the stirrup. Tlacotalpan boys, who wants to go with me?

26. Adios, negrito, me voy, Tu amor sera de quien quieras, Estos suspiros que doy, Para que veas que de veras, Que siempre tu duefia soy, Aunque tu ya no me quieras.

Goodbye, Blackie, I am going, you may love whom you please. I am sighing so that you will see that truly I will always be your mistress, even though you may no longer want me.

27. Eres, vida mia, la dama, A quien amo con empefio, Y como de mi te aclama, En donde me rinde el suefio, La calle cojo por cama, De cabecera un ladrillo, De las paredes me abrazo, Sofiando que estoy contigo.

You are, my life, the lady whom I needs must love, and since it (sic, my love), acclaims you. Wherever sleep overtakes me, I seize the street as a bed, a brick as a pillow, and, embracing the walls, I dream that I am with you.

241

CALIFORNIA FOLKLORE QUARTERLY 242

28. En las cumbres de un olivo, Un pajarito canto, Con su pecho adolorido, Como ahora tengo yo. Mal haya el haber querido, Un amor Zacatecano, Porque por haberme dormido, Me la han pegado en la mano.

On the tips of an olive tree, a little bird sang, its breast, like mine, filled with pain. Unhappy the day I loved a love from Zacatecas, because, having fallen asleep, they struck my hand (i.e., deceived me).

29. Tienes la ceja arqueada, Un mirar tan excelente, Y tu nariz afilada, Y una perla en cada diente.

You have arched eyebrows, such an excellent look, and your narrow nose, and a pearl in each tooth.

30. dQue corazon has tenido, De verme en tanto penar? (sic) Un papel no es recibido, Asi como no he de estar, De tu gratitud sentido.

What kind of a heart have you, seeing me in such pain? A paper is not re- ceived, thus I do not have to be offended at your ingratitude (meaning obscure).

31. Acuerdate que pusiste, Tu mano sobre la mia, Y llorando me dijiste, Que jamas me olvidaria, iFue lo primero que hicistel

Remember that you put your hand over mine, and, weeping, told me that you would never forget me. It was the first thing you didi

32. No hay como saber dar gusto, A quien gusto sabe dar, El que a mi gusto me diere, Yo gusto le habla de dar.

There is nothing like knowing how to give pleasure to him who knows how to give pleasure. To him who would give me pleasure, I would (also) pleasure him.

A MEXICAN SONG CONTEST

33. a) A las cumbres de un olivo, Una calandria cant6, Con su pecho adolorido, Como ahora tengo yo, Mal haya el haber querido.

b) Yo tenia mi cascabel, Con su piedrecita de oro, Y se me cay6 en el mar, Acaso por eso lloro, Ni me siento suspirar.

a) On the tips of an olive tree, a calender sang, its breast, like mine, filled with pain. Unhappy the day that I loved!

b) I had my (gourd) rattle, with its little golden pebble, but it slipped away from me into the sea. Perhaps that is why I weep, nor do I feel myself sigh.

34. Yo pretendi a una mujer, Era blanca y hermosota, Y cuando la fui a ver, Me contest6 con la boca,

"Tu debes de comprender, "Viejo, que tu ya no soplas"."

I courted a woman who was white, big, and beautiful. When I went to see her, she answered me with her mouth, "You ought to understand, old fellow, that your amorous days are over."

35. Yo pretendi a una catrina, Por el lujo de la ropa, Y me respondi6 la indina,'

"Viejito, tu ya no soplas, " 'ta bueno para cuidar gallina".

I courted a city girl on account of the luxury of her clothing. The haughty girl replied, "Little old fellow, you are done for-you are only good to watch the chickens."

36. Yo pretendi a una catrina, Andando en mi borrachera, Y me respondi6 la indina,

"iDeje Ud. de tontera, "Porque hoy la ropa fina, "No se la pone cualquiera!".

Drunk on a bender, I courted a city girl, and the haughty girl replied, "Stop your foolishness-nowadays not everyone can wear fine clothes!"

U soplar "to blow." Vulg., to be capable of amorous activity, to be good for. " Veracruz colloq. indina; Castilian indigna.

243

CALIFORNIA FOLKLORE QUARTERLY

37. Una mujer me ha contado, Que yo fui su perdici6n, Pero estoy desengafiado, Y creo que tengo raz6n, El que ha de ser desgraciado, Ya lo saca de naci6n.

A woman told me that I was her ruin, but I have no illusions, and I believe that I am right (when I say) that he who is destined to be unfortunate already is marked from his birth.

38. Todos me dicen que soy, Basura de toda broza, En el lugar en donde estoy, Hasta el gusto me retosa, Lastima que yo ya voy, MIas pa' viejo que otra cosa.

All tell me that I am rubbish and sweepings wherever I am. Even pleasure mocks me. What a pity that I am on the way to old age.

39. Me voy pa' Jerusalem, A ver si alla me mejoro, Y como vaya bien, Te mandare un carro de oro, Que anda el mismo que el tren.

I am going to Jerusalem to see if I can better myself there. Should it go well with me, I will send you a car of gold, which runs the same as the train.

40. Cigarro extra de la Havana, Fumaba la vida mia, Y dicen las de Santana,

"iQue rica categoria, "Blanca seda, fina lanal".

"Extra" cigarettes of Havana my life (sweetheart) used to smoke. The girls of Santana said, "What class! White silk and fine wool!"

41. Tuve una novia en las lomas, Y mucho amor me tenia, Delirando en tu persona, Yo vine a los quince dias, Ya me la encontre pelona, Yo ya no la conocia.

I had a sweetheart in the hills who loved me very much. But, returning after two weeks, inflamed with you, I saw that she was bald, and no longer did I know her (i.e., comparing her with you).

244