John Cage Amores

description

Transcript of John Cage Amores

Amores

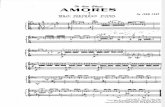

Composed in early 1943 after Cage moved to New York City, as a concert piece.

Choreographed by Merce Cunningham in 1949. Amores contains four movements:

1. Solo for prepared piano

2. Trio for 9 tom-toms and a pod rattle

3. Trio for 7 wood blocks

4. Solo for prepared piano

Eighteen notes are prepared using 9 screws, 8 bolts, 2 nuts and 3 strips of rubber. Similarly to

Bacchanale, the performer is instructed in the score to "determine position and size of mutes

by experiment". This was one of Cage's earliest works to use Cage's rhythmic proportions

technique. The structure of the second movement, for example, is based 10-bar units each

divided into four sections: 3, 2, 2, 3. The proportion 3, 3, 2, 2 is used similarly in the second

solo for prepared piano.

John Cage's "Trio" from Amores (1943): A Study of Rhythmic Structure and Density

John Welsh

John Cage's percussion music of the late 1930s and 1940s is striking with regard to its

structure and unique sonic identity. Toward this end, Cage sustains a high level of

compositional craftsmanship. Consistency and balance are integral to the organization and

composition of such works as his Imaginary Landscape series (1939-1952), Credo in Us

(1942), She Is Asleep (1943) and Amores (1943) - among others. Deeply rooted in numerical

procedures and containing an economy of sonic materials, these works reveal a carefully

calculated sense of dramatic growth.

Cage's Amores (1943), for percussion trio and prepared piano, contains a third

movement - "Trio" - scored for seven woodblocks (see Appendix A). The woodblocks are

distributed as follows:

Thus, three different registers/pitches are notated. In this work of limited resources, Cage

creates a remarkably rich level of activity and a clear formal design. The score for the "Trio"

has been reprinted on the next pages. The formal and dynamic design is supported by the

entrance of different rhythmic modules. It begins "piano" with the next change of dynamics

"pianissimo" appearing in measure 23 followed by a diminuendo beginning in measure 28.

Measure 13 begins in the same manner as the opening except for the metric displacement of

the rhythmic modules. This design is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Sectional dynamic scheme of Cage's "Trio" from Amores.

More significant in this formal design, however, is the interplay of two basic modules

(now called Module A and B, see Example 1 below) and their variants, from which the entire

"Trio" is composed.

Example 1: Rhythmic modules in Cage's "Trio" from Amores

Module A is really three repetitions of a basic cell. Because the three repetitions

appear in a single rhythm during the course of the work, it is the author's decision to label

Module A as cited. (The first three measures of the "Trio" clearly illustrate this grouping.)

The exact combinations of these two modules can be observed in the resultant rhythm of the

entire movement.

Figure 2: Resultant rhythm of the "Trio" from Cage's Amores

Each section has been marked off in the above chart with a dotted line. Within each

section, phrases have been identified as well. These phrases reveal the formation of activity.

In fact, Cage's "Trio" is concerned, on the micro- and macro- levels, with a consistent increase

in the level of activity. On the micro level, the A and B modules themselves gain in activity,

while, despite the decreasing dynamic level, the entire work slowly generates more and more

energy.

The resultant rhythm will be examined with regard to the increase in activity (i.e.

increases in attacks.) Consider Section I which divides into three phrases, each, four measures

in duration: phrase 1 (mm. 1-4), phrase 2 (mm. 5-8), and phrase 3 (mm. 9-12). The patterns of

fluctuation in activity determines this division. Each begins slowly and then speeds up. This

aspect is significant and forms the basis for the entire "Trio". Furthermore, the two modules

themselves are rhythmically distinctive -module A features values and module B features

values. A shift from the A module to the B module produces a new rhythmic identity and a

more dense texture as can be observed in phrase 1 of Section I (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Section I, phrase #1 (mm. 1-4)

The increase in attacks in the resultant rhythm can be examined further. A determination can

be made regarding the rate of attacks per ; in this way, both modules can be observed

either together or independently as they unfold during the course of the work. For example,

in phrase 1, Module A contains 3 attacks, 3 attacks and 3 attacks, a total of nine attacks

spanning a duration of 18 ) s. Consequently, for Module A there are 0.5 attacks per

For Module B, there are 9 attacks spanning 6 s; the rate of attacks per is

1.5. In moving from the A to the B Module, the rate of attacks per is tripled. A clear pattern

of activity formation has been drawn, and Cage is consistent in his utilization of this

technique throughout the work.

The rate of attacks per for the resultant rhythm of the entire work is summarized in Figure 4

(below). In this chart, which describes the activity of the resultant rhythm, the attacks listed

under Module A are those that are clearly variants of Module A and/or feature the

characteristic eighth values. The same is true for Module B, and its characteristic sixteenth

and triplet values. The totals on the right display a steady increase in attacks per in three of

the four sections. There is a gradual increase in attacks culminating in Section III. Section IV

balances the ending with the opening section.

With regard to Section I, Module A steadily increases in attacks per (from .50 to

.78) while these attacks are occurring within decreasing time frames (from 18 s to 14 s).

For the B Modules, the rate of attacks per decreases (while the duration increases);

however, 1.25 and 1.10 attacks per are still far above those of the A Module. Compared to

the A Modules (horizontally in the chart), the B Modules show a substantial increase in

activity. In phrase 1 alone there are 1.50 attacks per and that is three times greater than that

of the A Module. The rate of attack is nearly doubled in phrase 2 when moving from Module

A to Module B. In phrase 3, the same comparison reveals a slight increase in the attack rate.

Section II consumes less time (ten measures) with only two phrases. Remarkably, phrase 1 is

consistent with phrase 1 of Section I. Module A contains .50 attacks per ; while, Module B

has 1.42 attacks per ). The only significant change here is that Module B maintains its high

attack level over an extended time period (12 opposed to 6 earlier.) Phrase 2 shows a

dramatic increase in the attack rate per for Module A. In a 10 duration, there are .70

attacks per , while Module B nearly maintains its high level of activity (1.40 attacks per

over 20 ).

The intensification for each module occurs separately. Module B is highlighted in

Section III, Module A in Section IV. In Section III, the A Module appears briefly. Nearly the

entire section involves the B Module (1.47 attacks per maintained over 30 s) while Module

A sounds only 0.50 attacks per . Therefore, with regard to the rate of attacks in the resultant

rhythm, for Module A there is a precise and consistent increase in the formation of activity

culminating in Section IV (its highest rate maintained over its longest duration/appearance).

Likewise, Module B increases its activity level by spanning out and slowly assuming more

time, yet very nearly maintains 1.50 attacks per ) . Module B reaches its zenith in Section

III.

Figure 4: Rate of Attacks Per Eighth

The Interaction of Rhythmic Modules

The next area to be addressed concerns the modules themselves. ;How are they juxtaposed?

How do they relate to one another? Taken 'together, do the modules reflect the formal design

and do they support the activity gain that was so prominent in the resultant rhythm?

Figure 5 reveals the entrance and duration of each module during the course of the work. As

the piece unfolds, the sections grow shorter while the space or time between module entrances

decreases. With regard to the balanced proportions displayed in Cage's early music, the A

Module enters in the order: Player 1, 2, and 3; the B module enters in reverse fashion. In

addition, each B Module entrance is 16 s apart (mm. 4, 7, and 11).

If the succession of entrances is traced through the entire "Trio," the increase in activity will

clearly be discerned. With reference to the preceding chart, each section has been divided

where appropriate to reflect the opening series of entrances (dotted, line in Figure 5 below ):

that is, an A Module followed by an A and B Module (simultaneously) then succeeded by an

A Module. (This is the first portion of Section I). The second half of Section I begins with an

A Module displaced to the second beat. This displacement is one of the primary vehicles for

development in Amores. In Section I (first half), the time of 18 s passed before any new

entrance. In the second half, after the displaced A Module appears, a denser texture emerges

when a B Module enters after only 2s. Next, Players 2 and 3 enter with A Modules;

however, this occurs earlier than in the first half, thus creating an overlap of three A Modules.

Player 1 concludes the section with a B module which creates a balance in this section: each

player performs two A Modules and one B Module (each appearing at a regular time interval

of 16 s).

Section II begins in the same manner as Section I, with an unaccompanied statement of

Module A now displaced to the upbeat of one. Recall that in Section I, Players 2 and 3 entered

after 18 s with an A and B Module respectively. Consistent with the acceleration of activity

that is the hallmark of Cage's "Trio," in Section II (m.1,6) the A Module enters at the expected

time (after 18 s) to parallel the opening, but the B Module (Player 3, m. 16) enters early:

an eighth-note's duration exactly. This is the first time the B Module has entered before the A

Module. To reinforce this acceleration there are two consecutive statements of the B Module.

This increase in activity can be seen as well in the second half of Section II. After the A

Module enters displaced (Player 2, m. 16), there is another A Module sounded by Player 3.

This statement enters after 17 s) or one eighth sooner than usual. The third A Module

enters after just 4 s. Finally, Player 1 sounds three B Modules in succession, now propelling

the work into Section III.

Figure 5: Entrances and Durations of the Modules

Section III includes a series of five repetitions of the B module (four successive and one

overlapping) which has now completely overtaken in predominance from the A Module.

(Section I had only one statement of the B module at a time; Section II had two and three in

succession.) In Section III, the B Module reaches intensification with five statements: four

(Player 3) and one (Player 1) with the only overlap of B Modules occurring in measure 27.

The rests between B Modules in mm. 25 and 26 begin to decrease the attack rate and thin the

texture of the work in preparation for the ending.

In Section III, Player 1 (m. 23) sounds an A Module followed by Player 2 (with an A Module)

only nine eighth notes later. This is the smallest amount of time yet between first and second

soundings of an A Module. To elicit the intensification for the A Module, Cage utilized the

technique of elision. The first elision appears with Player 2 in measure 27 as illustrated in

Example 2.

Example 2: Rhythmic Elision in m. 27

Along with this significant departure from the techniques of the earlier part of the work, the

elision is combined with melodic inversion, thereby signaling even greater activity in the A

Module. These successive statements produce longer phrases constructed from the A Module

and its melodic variant. The focus in Section IV (mm. 28-33) shifts to the A Module and

functions as a final exclusive intensification of this idea. A second elision displays the

intertwining of A Modules and sounds with Player 3 (mm. 28-31, see Example 3.)

Example 3: Rhythmic Elision in m. 28-31

The Structuring of Coincidental Attacks

Now consider a count of the multiple attacks (i.e. 2, 3, and 4 simultaneous attacks) .

This is charted in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Simultaneous Attacks

An important observation can be made regarding the rate of multiple attacks per The

rate increases through Sections III and IV, creating the most dense textures in the "Trio." This

runs parallel with the intensification of Modules A and B. These totals are summarized in

Figure 7.

Section I 0.333

Section II 0.383

Section III 0.437

Section IV 0.500

Figure 7: Rate of Multiple Attacks per

Now consider a detailed look at these multiple attacks. While there seems to be an equal

distribution among all the players, the number of tutti attacks (i.e. 3 or 4 attacks) is

significant. In Section I, the only tutti attack occurs in measure 11, where the cadence for the

entire first section takes place. All three players simultaneously strike the lowest woodblock,

thereby punctuating the increased activity rate. A slight increase in the rate of multiple attacks

per occurs in Section II. This acceleration is further enhanced in Section III with three

tutti attacks. In measure 25, beat 3, a significant tutti attack occurs - Player 1 with its two

attacks and Players 2 and 3 with one apiece. This is the only such tutti in the "Trio". In

Section IV, while the rate of multiple attacks is its highest, only one triple attack /appears. At

this point in the composition, Cage begins to prepare a final cadence - here there is a gradual

thinning of the texture and exclusive emphasis on the eighth-note rhythmic values. Along

with the non-sustaining quality of the woodblock, this introduces silence near the final

cadence, balancing the sound and silence interaction of the opening few measures.

The conclusion of the work is prepared with great care. Until measure 31-33, the

multiple attacks have avoided the downbeats, occurring only four times previous to mm. 31-

33. At the downbeat of measure 31, Players 2 and 3 simultaneously strike their lowest

woodblock, again at the downbeat of measure 32, and a third time in measure 33, thus

emphasizing and stabilizing the triple meter for the first time in the "Trio."

The final chart to be considered (Figure 8) is of a more globally statistical nature,

containing attack points in all voices and their distribution throughout the "Trio."

Figure 8: Attack Points

Players 1 and 3 have the most attacks; they also sound the B Module more times. Player two

performs Module B only once (in Section I). The only significant number with regard to

attacks per section can be observed in Section I, where each of the players has 26 attacks,

creating an initial state of balanced distribution between the players., More important,

however, is the number of total attacks per section per (the right side of the chart). The rate

of attack points per ) rises until Section III, coinciding with the high level of multiple

attacks and soundings of the B Module. Thus, the most dense texture of the work is formed.

The final cadence is prepared by the dramatic decrease in attacks in Section IV.

In conclusion, Cage's "Trio" is a classic example of a clear unfolding of activity and formal

design through the juxtaposition of two distinct modules. This is supported by the resultant

rhythm, the intensification and movement of each module, the multiple attack rate, and the

attack points. The statistical calculations reveal with great clarity the compositional precision

of John Cage which is especially evident in his percussion music of the 1930s and 1940s.

Consistency, balance, and an economy of means are the mind-set for Cage's early music. This

can be further witnessed in a statement by the composer himself:

Patsy Davenport heard my Folkways record. She said, 'When the story came

about my asking you how you felt about Bach, I could remember everything

perfectly clearly, sharply, as though I were living through it again. Tell me,

what did you answer? How do you feel about Bach?' I said I didn't remember

what I'd said -that I'd been nonplused. Then, as usual, when the next day came,

I got thinking. Giving up Beethoven, the emotional climaxes and all, is fairly

simple for an American. But giving up Bach is more difficult. Bach's music

suggests order and glorifies for those who hear it their regard for order . . . .

Some people say that art should be an instance of order so that it will save

them momentarily from the chaos that they know is just around the corner.

Jazz is equivalent to Bach (steady beat, dependable motor) and the love of

Bach is generally coupled with the love of jazz . . . . Giving up Bach, jazz, and

order is difficult. Patsy Davenport is right. It's a very serious question. For if

we do it – give them up, that is - what do we have left?2

1 With permission from Peters Edition. The recording of the "Trio" from Amores reproduced

on the accompanying sound cassette for this issue features Edmund Fay as Player I, James

Pugliese as Player II and Charles Descarfino as Player III, recording engineer Manfred

Knoop, recorded at Mohawk Recording Studio, River Edge, New Jersey.2 John Cage, Silence, Weslayan University press, Middletown, 1973, pp. 262-263.

APPENDIX A:

ORGANIC STRUCTURES IN JOHN CAGE'S EARLY PERCUSSION MUSIC

Thomas DeLio

John Cage’s Amores (1943) represents a farsighted and significant moment in the evolution

of music in the 20th century—a vortex of oppositional impulses within which both organic

and inorganic based methodologies are drawn together within one compositional framework.

In this talk I will focus on one instance of his organic approach to composition. Oddly

enough, this seems to be one of the least understood aspect of his music. His well-known

work with indeterminate procedures has been the subject of much discussion and

examination. The concomitant rejection of personal taste as a guiding force for his creative

impulses is well documented. However, it is not often acknowledged how beautifully

Cage could design music while relying on his own personal tastes, as the first and third

movements of Amores can readily attest. Indeed, these movements can easily stand in

response to any who still persist in the tired view that Cage was a philosopher whose music is

more interesting to talk and think about than to hear (or therefore analyze).

In each of these movements a unique form develops that can only have arisen from the

specific materials employed. Their interactions shape each movement in very specific ways

that could not have been achieved using any other materials. In the first and third movements

form and materials are entirely codependent. The third movement, in particular reveals,

Cage‘s remarkable skill in fashioning a truly multi-layered musical design from the simplest

of sonic materials, one that captures the ebb and flow of time in a thoroughly hierarchical

fashion—a true sign of organic thinking.

The Amores of John Cage (review)

Paul Cox

From: American Music

Volume 29, Number 1, Spring 2011

pp. 113-116 | 10.1353/amm.2011.0010

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

This examination of Cage’s 1943 work, Amores, for percussion trio and prepared piano,

continues a promising trend of book-length studies of individual Cage works. For over

twenty-five years, Thomas DeLio, a composition and theory professor at the University of

Maryland, has been at the forefront of developing new analytic approaches to Cage’s music.1

In this case, he devotes a separate chapter to an analysis of each of Amores’ four movements,

charting the minutiae of Cage’s varied soundscape, from prepared piano timbres in the first

and fourth movements to composite rhythmic structures and “density of percussion attack

points” in the second (for nine tom-toms and pod rattle) and third (for three sets of

woodblocks).

While immersed in the book’s detailed charts, scores, and graphs, a nagging question arises:

what would Cage think of all this theoretical attention?2 In a moment of rhetorical whimsy, he

himself once scribbled (then crossed out) two questions: “Why analyze music? Why not listen

to it?”3 Cage’s thinking at the time was premised on moving beyond formalist positions in

order to open our ears to the wide range of sounds around us. He notes in “Listening to

Music” (1937) that since modern music (and non-Western music) does not follow the rules of

traditional Western art music, listeners are free to hear sounds without fear that they “mistook

the Development for the Recapitulation.” As Cage sums up, “music need not be understood,

but rather it must be heard.”4

Though DeLio’s mission is clearly to help us understand Amores, he does so on Cage’s terms

by treating all sounds—pitched or percussive—equally. By organizing these sounds into a

logical schema, he then uses analytic methods far removed from the formal and harmonic

methods familiar to Cage in the late 1930s. For example, he draws on statistics for an analysis

of the second movement, tracking the “density” of tom-tom attacks and their mean average

per second throughout (59). The result reveals a previously unknown symmetry to Cage’s

rhythmic language.5 This is one of many insights to be gleaned from DeLio’s work, and while

this book is geared primarily toward theorists, and especially to those interested in exploring

new modes of nonharmonic analysis, this is by no means a typical collection of analyses.

In the opening chapter, “Introduction: A Modernist Vortex,” DeLio sidesteps the worn

debates of twentieth-century music: high art versus low art, serialism versus indeterminacy,

Stravinsky versus Schoenberg, and so on. Instead, he grounds his reading of Amores in

modernist poetics and the opposition between organic and inorganic form, drawing on

Marjorie Perloff’s delineation of two streams: the Symbolist (T. S. Eliot and Charles

Baudelaire) evolving from Romantic notions of organic form, and the anti-Symbolist (Arthur

Rimbaud and Gertrude Stein), characterized by an inorganic or indeterminate approach.6 The

organic is characterized by a clear interdependency between form, content, and artistic

intention: “The artwork becomes an image of the individual; its form and process one with the

self” (4). Conversely, the inorganic severs the link between artist and work in order to more

directly conjure the phenomena of experience.

Traditionally these two approaches have been separated in modernism studies. DeLio,

however, argues that they should be considered together, contending that their coexistence

and interdependence is a “central paradigm” of modernism. Using Amores as a case study, his

assessment is unequivocal: Amores “represents a farsighted and historical moment in the

evolution of music in the twentieth century—a vortex of oppositional impulses within which

the organic and inorganic are drawn together in order to reveal their mutual interdependence. I

refer to the design of Amores as a vortex in that it draws vastly different, seemingly unrelated

ideas together” (15). DeLio uses Ezra Pound’s term “vortex,” defined as “the point of

maximum energy,” to capture the dynamism of Cage’s oppositional aesthetic.7

A central element in determining organic or inorganic form is...