Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

Transcript of Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 1/74

BUILDING MISSOURI’S

URBAN AND TRANSPORTATION

INFRASTRUCTURES TO SUPPORT

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Jerome J. Day

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 2/74

Contents

Page

Abstract 4

Executive Summary

Introduction 4

The Vitality of Missouri in the Kansas City – 5Columbus, Ohio, Urban Corridor

Models of Urbanization

Missouri’s Role

Missouri’s Advantages

Interstate 70, the Transportation Backbone 10Infrastructure of the KanCol Corridor

Investment in Transportation Infrastructure –Historical Survey

Decline in Missouri’s Historic Role

Justification of Investments – Return on Investment

Missouri’s Experience – Comparison of U.S.Highway 63 and U.S. Highway 65

The Way Forward: The KanCol and Kansas City – 16Saint Louis Urban Corridors

Understanding Urban Corridors

2

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 3/74

Steps to be Taken

Working Collaboratively Rather than Competitively

The Way Forward: The Interstate 70 20Transportation Infrastructure for Urban Corridor Economic Development

Recent Planning for Interstate Highway 70

Proposals for New Interstate Highway 70 Corridors

Corridors of the Future Program 28

Opportunities for the Future 32

Introduction

Environmental Opportunities

Enhanced Railway Opportunities

The Urban Corridor Benefits Reiterated

Benefits to Passenger Rail

Summary of Opportunities

Solution: New Railroad in the Urban Corridor 39

Review of Railway Technology

Safety

Lower Operating Costs per Ton-Mile,Now and in the Future

Reduced Rolling Friction

3

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 4/74

Reduced Aerodynamic Friction

Reduced Fuel Costs – Possibility of Electric Power

Improved Yard and Railway Operations

Lower Labor Costs, More High Skilled Jobs

Higher Speed, Quicker End-to-End Delivery

Concluding Remarks

Financing 56

Improved Prospects for Investments inInfrastructure

Current Situation

Loss of Gasoline Tax Revenue

Comment on Usage Fees Versus Fixed Fees

Charging of Tolls for Highway Usage

Summary and Conclusions 68

End Notes 70

About the Author 73

4

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 5/74

BUILDING MISSOURI’SURBAN AND TRANSPORTATION

INFRASTRUCTURES TO SUPPORTECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Abstract

This paper presents the case for Missouri promoting more rapid economic growth by developing a Saint Louis– Kansas City Urban

Corridor as a component and model for a subsequent, larger Kansas City– Columbus, Ohio Urban Corridor. In the course of thedevelopment of these Urban Corridors, very substantially enhanced transportation infrastructure investments would be necessary inorder to realize the opportunities presented, and to obtain thebenefits envisioned. This would involve large increases in thecapacity of Interstate Highway 70, as well as opening up large areasof low-cost land for location of new business ventures nearby to thenew highway developments.

This paper addresses the federal “Corridors of the Future” program,as well as addressing proposals that have been made to add Truck-Only Lanes (TOL’s) to the existing Interstate Highway 70. It alsoconsiders alternatives for providing advanced-technology freight transportation (based on enhancements of the current intermodal model), as well as high-speed passenger rail services that could beconsidered if the Urban Corridor concept were to be implemented.

Finally, the paper elaborates the benefits of installing an advanced-technology freight railroad, with provision for passenger services, inthe Urban Corridor proposed in this paper. It further contrasts thecomparative benefits and costs of rail and truck movement of freight,including movement of freight by Truck-Only Lanes (TOL’s). Theanalyses presented include a discussion of financing alternatives.

5

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 6/74

Executive Summary

The following summarize the major conclusions of this paper:

• The Urban Corridor concept is a valuable paradigm for futureurbanization. It enables and provides high-quality, high-speed, localized access toefficient, effective, and economical automobile, truck, transit, and rail passenger and freight movement. It discourages urban sprawl, preserves open spaces, andis environmentally friendly.

• The Urban Corridor requires a high-speed, high-capacity, and robustmultimodal transportation infrastructure for people and freight.

• The best model for freight movement is the proven intermodal model.

• Freight movement within the Urban Corridor would be most economicallyprovided on an enhanced, 21st-century railway running down an Interstatemedian strip.

• Freight movement on the new railway would be best provided byelectrically-propelled transporter vehicles, which are, in more conventional terms,simply independently controllable and operated, electrically-powered flatcarscarrying conventional shipping containers.

• The intermodal model is best further developed by new, current-day andfuture-technology railways. These would evolutionarily supplement and replace inthe Urban Corridor much of our historic 19th-century railway technology andoperational practices. This would greatly increase freight hauling capacity andreduce costs. Further, it would reduce the minimum long-haul trip for intermodaloperations to about half what it is today, for locations near an intermodal transfer point. Finally, it would reduce relatively the truck density on the Interstates,thereby reducing congestion, and improve the driving environment for automobiledrivers.

• Future transportation infrastructure and maintenance could well befinanced by Public-Private Partnerships and user fees, such as tolls. Gasoline taxrevenues are dwindling with the advent of alternative power sources for automobiles. Financing from general revenues is dysfunctional.

• Almost all of the benefits ascribed to Truck-Only Lanes (TOL’s) would bebetter realized by the Urban Corridor development featuring, among other benefits, high-speed, timely movement of freight by railway to an intermodal

6

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 7/74

transfer point. The one exception is that trucks better serve shorter-haul freightmovement.

• The advanced-technology, electrified railway, as proposed in this paper,would result, in the areas in which might be implemented, in a new freight

movement paradigm, and in an increased volume of rail freight movement thatwould revolutionize modern concepts of rail freight movement.

• Even if the enhanced, advanced-technology railway proposed in thispaper did not use electric power, a current day-technology railway installed in themedian strip of a new Interstate highway in the Urban Corridor would generatefreight cost savings and other benefits sufficient to justify its installation.

We need to ask key Missouri leaders and policymakers to consider the question of what kind of urban and economic future we want for Missouri. We need to consider

whether the Urban Corridor, combined with I-70 North, is the most cost-effective,most environmentally sensitive, and most efficient way to achieve this better future.

If we have the will and determination to achieve this better transportation future,along with a viable plan, then a way will surely be found to overcome what are thelargest obstacles, namely the financial issues.

7

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 8/74

Introduction

Missouri today is facing the same economic challenges that it has always faced:how to produce economic opportunity, growth, and prosperity. However, Missouriis now uniquely presented with two great opportunities to aid in meeting thesechallenges and attaining these goals. If Missouri were to invest private and/or public money into an integrated infrastructure expansion across central Missouri, Ibelieve the entire state would benefit greatly.

The first opportunity arises from the urbanization that is already occurring alongthe Saint Louis– Jefferson City and Columbia– Kansas City Urban Corridor. This isoccurring as a dynamic component of the larger Kansas City– Columbus, Ohio,

Urban Corridor. The development of this Urban Corridor is aligned to the Interstate70 highway transportation corridor.

The second opportunity is the redevelopment of the Interstate 70 highway itself.This requires investment that will enable maximum economic development benefit,concurrently with the same investment providing a long-term solution to theoverloading and congestion that over the past decade have become ever moreevident and wasteful.

In the past several years there have been many new developments, including theelection of a new national administration and Congress, as well as a new Missouriadministration and legislature, and an economic downturn. Collectively andperhaps paradoxically in some respects, these present a better long-termenvironment for proposals to now address more comprehensively thetransportation infrastructural needs for handling automobile, truck, large-scale railfreight movement, and high speed inter-city passenger rail service.

The view that Missouri now faces a more favorable environment for taking a moresubstantive stance, is prompted by the growing recognition that Missouri hasserious deficiencies in its economic and transportation infrastructures.Furthermore, there is growing concern that a lack of an integrative approach totransportation and urbanization, as well as ecological issues, require a reformedapproach to addressing many of these issues in a comprehensive, integratedmanner. The Urban Corridor paradigm provides a framework for accomplishingthis.

Additionally, other trends and events in the recent past, favoring the railwaydevelopments now being proposed, have led to increasing awareness of the needto achieve greater economy in the use of petroleum fuels. This need is due to thedepletion and rising costs of these fuels, and the adverse impacts of their use

8

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 9/74

where not absolutely necessary. Taking these adverse economic andenvironmental concerns into account, as a policy matter, could encourage us toseek to attract and make provision to move long-distance freight and people bynew technology, such as modernized rail systems, rather than seeking to movemore freight via highways.

This paper will also consider how financing of the proposals presented may bestbe carried out.

The proposals in this paper are directed to two opportunities for improvement. Firstare the economic development opportunities that the Urban Corridor modelpresent as an alternative model of urbanization to the current model of expandingconcentric rings of suburbs around major cities. The second opportunity involvesthe more economical and environmentally friendly transportation services that anenhanced 21st-century railway infrastructure would provide for freight andpassenger traffic. In neither case should these proposals be seen as an exercise in

centralized urban or industrial planning. Instead, the proposals are presented toafford a wider choice of opportunities for considering what sort of developments wewish to be afforded to us in the 21st century.

9

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 10/74

The Vitality of Missouri in the Kansas City–Columbus, Ohio, Urban Corridor

Models of Urbanization

At the outset, a few words about Urban Corridors: demographers and economicgeographers generally identify three great corridors of people and economicactivity in the United States. The first to develop was the Boston– Washington, D.C. corridor and the cities between them, which is sometimes called the BosWashcorridor. The second corridor to develop was the Chicago– Pittsburgh corridor connecting the cities in between, including Detroit. ChiPitts is the name given to it.

The third to develop was the San Francisco–San Diego corridor, including itsinterconnected cities. It is named SanSan. [1] Among other distinguishingcharacteristics of these elongated urban concentrations of people is the integrationof economic activity in the corridors, and that they are served by substantialtransportation infrastructures. Historically, the Atlantic and Pacific waterways, aswell as the Great Lakes, have fostered economic development by affordingeconomical transport of people and goods. Missouri has seen the same effect onthe Mississippi River and the Missouri River. In the latter half of the 19th century,the development of railroads played the same role that water transportationinfrastructure played in promoting economic growth and well-being in the earlier period. In the 20th century, highways took over as the primary transportation

infrastructural impetus to economic development and urbanization. As a result, wehave seen the ongoing development of these elongated Urban Corridors whosetransportation infrastructures, preeminently now highways, have fostered theinterlinking of the cities and economic activities along their corridors. By providingquicker, higher-capacity, less costly interlinking of people and businesses alongthe corridors, these transportation infrastructures have greatly fostered economicgrowth, jobs, and prosperity. They have, as well, greatly improved the livelihood of people living in adjacent rural areas by reducing the costs of delivery of agriculturalproduction materials. Equally, they have reduced costs in getting agriculturalproducts to both expanding local and national urban markets as well as overseasexport markets.

As a pattern for economic development, the vitality of Urban Corridors cannot beoveremphasized, partially because this pattern has not been widely recognized.Conventionally, most people think of urbanization as a process in which a coremajor city expands outwards in all directions along the existing streets and roadsconnecting it to other major cities. Suburban towns develop, and later more distant“ex-urbs” develop. This might be described as the agglomeration model of

10

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 11/74

urbanization wherein successive rings of urbanization develop around major corecities.

However, this pattern of development has several disadvantages. Among thedisadvantages is the tendency to overload existing transportation infrastructures,

particularly roads and highways. These tend to be organized along historical star-shaped patterns with traffic flowing to inner hubs in order to interchange to another highway out to the destination point. A partial solution to this has been thedevelopment of ring highways surrounding the central city. This was firstexemplified by the building of Massachusetts Route 128 around Boston in the1950’s, predating the Interstate System. Route 128 was originally built to whatwould become Interstate-standards, with two limited-access traffic lanes in eachdirection. By the time that it was completed in the early 1960’s, Route 128 hadattracted so much industrial, commercial, and urban development in its environsthat serious congestion was occurring. This led to widening to three lanes. Todaywidened Route 128 has been re-designated as a component of Interstate 95.

The original widening of this highway attracted so much additional developmentand traffic that a decision was made to build a second, outer ring road aroundBoston about 10 miles further outside of Boston. Today, this is Interstate 495, andit is now heavily congested, with no relief in sight. At this point, it is cautionary toconsider whether Massachusetts’ double-ring highway was the best choice to meettheir urban development needs. Probably, an elongated Boston–Worcester–Springfield (Massachusetts) Urban Corridor westward from Boston would havebetter served the development of the state, particularly considering the extremeurban and financial problems Springfield and the western part of that state facetoday with the dying of old industries. But such an urbanization corridor could notdevelop so long as toll-free ring Interstates were opening up new office park andindustrial sites around Boston. The attractiveness of Springfield and the westernpart of the state has been further reduced by the congested MassachusettsTurnpike (Interstate 90). It is the sole Interstate-standard highway to Worcester and Springfield, and it is heavily tolled with infrequent interchanges.

This story is told because it illustrates that simply building more ring highways andfurther development of hub and spoke configurations around major cities does notreally offer a solution to congestion problems in modern urbanization. It simplyencourages patterns of urbanization and further congestion that harms our citiesand their surrounding areas and makes them a less desirable place to live for many people. It aggravates the very problems that it is meant to solve.

A further problem with this pattern of urbanization is that it tends excessively todraw people out of rural areas, and because these areas become depopulated,they are unattractive as locations for new industrial and commercial activities.Disparities follow, intensifying this pattern. Inner cities tend to deteriorate, chokedby congestion, and sprawling parking lots. As commercial activity diminishesdowntown, the inner city becomes populated by urban poor living in older,

11

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 12/74

substandard housing, with substandard schools and low-paying jobs asbusinesses desert the cities for more attractive locations in the suburbs and ex-urbs. Young people, in particular, desert the countryside for better-paying jobs inthe outer urban areas surrounding the major cities. A tremendous demanddevelops for an ever more extensive web of expensive higher-capacity highways

to serve this agglomerative urbanization process.

Alternatively, the Urban Corridor pattern of development tends to draw industry,commercial establishments, and people to the areas between the great cities, tothe areas between Kansas City and Saint Louis, or between Kansas City andColumbus, Ohio, for example. For several obvious reasons, as will be discussedlater, such an Urban Corridor development requires a very robust and efficienttransportation infrastructure to form the backbone of the Urban Corridor.

Missouri’s Role

Before going on to consider other aspects of the transportation infrastructure of Urban Corridors, some additional remarks are in order about Missouri’s role in thedevelopment of the United States’ transportation infrastructure.

Apart from the previously noted development of the BosWash, ChiPitts, andSanSan corridors, there is another great shift in the demographics and economicgeography of the United States that should be noted. Historically, our UnitedStates’ population and centers of economic activity have been shifting to the westand south.

This continues into the current day, and there is every reason to conclude that thiswill continue into the future. This now presents Missouri with a new opportunity toreassert its traditional role as gateway to the West. This traditional gateway role ispotentially now being expanded. Missouri stands astride the major landtransportation route connecting the old BosWash and ChiPitts Urban Corridorswith Mexico and the western and southwestern United States. The United States’rapidly increasing trade with Mexico is already leading Texas to plan new roadbuilding along the Interstate 35 route in that state running from the Mexican border at Laredo, Texas, to the Oklahoma state line. This is the first part of their Trans-Texas Corridor project, which has been widely reported. Of special interest is a

recently reported article in the Los Angeles Times. [2] Notably, most of thedeveloping trade traffic of Chicago and the northeastern United States with Mexicocurrently tends to naturally flow across Missouri. Although much of this traffic maylikely seek to follow the Interstate 44 route across Missouri, it still enhancesMissouri’s role as a Mid-Continent gateway and crossroads, which a Kansas Cityto Columbus, Ohio, corridor also seeks to embellish.

12

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 13/74

Even more noteworthy is another transportation infrastructural aspect of the rapidlygrowing North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA). This association of theUnited States with Canada and Mexico is producing rapidly increasing North-Southtrade and truck transport between the three countries. At the southern end, thisaccounts for the needs Texas is addressing in building a new highway along I-35.

However the same Los Angeles Times article previously cited [2] describes asecond phase of the Trans-Texas Corridor:

“The second phase of the corridor, whose planning contract has yetto be handed out, would build a similar highway from the westernedge of the Mexico border to east Texas. This might one day link toa separate, federally initiated eight-state expansion of Interstate 69,which currently runs between Port Huron, Mich., and Indianapolis.”

The northern end point of I-69, Point Huron, is near Detroit, and is at the westernend of Canada’s heavily industrialized corridor linking to Toronto and Montreal.

Therefore, Port Huron and Detroit are the natural point of entry for NAFTA tradebetween Canada and Mexico, and trade between Canada and the United Statesareas west and south of Detroit. Much of this rapidly increasing traffic might beexpected to travel through the corridor from Indianapolis along I-70 to Kansas City,and I-35 to Texas, or via I-44 across Missouri to I-35. That is, Missouri couldexpect to host this traffic unless the Trans-Texas Corridor’s second phase to eastTexas were to draw this traffic to a more easterly and southerly route bypassingMissouri, say through Dallas, Little Rock, Memphis, Nashville, and Louisville toIndianapolis. This southern route would also be attractive to much of the rapidlygrowing United States– Asian trade traffic that now (according to anecdotalreports) travels via I-70 through Missouri between southern California ports andChicago and the northeastern United States.

This presents a vital opportunity for Missouri to further attract these traffic flows.Missouri also faces the opportunity to embellish its image and role as thecrossroads and gateway to the west, southwest, and Mexico. Although it mayseem that Missouri has little to benefit economically from traffic that simply transitsMissouri, such traffic is nevertheless very important. Its importance is that it buildsMissouri’s image as a place at the crossroads, and a center around which trade,commerce and people congregate. This translates into a desire for companies towant to locate their business operations in Missouri.

If we can better establish the concept of a Saint Louis– Kansas City UrbanCorridor, then we could greatly promote the attractiveness of Missouri as a locationfor industrial, commercial, and high-technology firms and institutes. Furthermore, if we can promote the advantages and feasibility of the Kansas City– Columbus,Ohio, corridor, what I will now call the KanCol Corridor, then it would help to secureMissouri’s role as the new Mid-Continent center of economic progressiveness andrapidly increasing prosperity.

13

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 14/74

14

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 15/74

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 16/74

Interstate 70, the Transportation BackboneInfrastructure of the KanCol Corridor

Investment in Transportation Infrastructure: Historical Survey

Most people view highways not as investments, but simply as a way to getsomeplace. Many Americans look upon tax spending on road maintenance or building new highways as a necessary evil to alleviate congestion and failinginfrastructure, such as building bridges or repairing pot-holed roads. However, thiswas not always the prevailing mindset. In times past, to a much greater extent than

today, people have seen building new transportation infrastructure as aninvestment in the future, which establishes a foundation for subsequent economicgrowth and development. Such investments satisfy some of the necessaryconditions for developing markets, creating jobs, lowering costs, and promotingprosperity. People need to regain the sense that expenditures for transportationinfrastructure can accomplish much more productive purposes. Theseexpenditures must not be conceived as solely or primarily for addressing problemsof congestion and failing bridges and highways. We need to be makinginvestments in infrastructures that will alleviate congestion and make repairs. Butadditionally, and more importantly, the investments, not simply expenditures, mustadd substantially increased new capacity, and also relieve stress on existing

facilities. Still more vital, we should attempt to make these investments in amanner that opens the way to new and substantially greater economicdevelopment and prosperity, in conjunction with promoting a beneficial model of urbanization.

There are many imaginative, historical examples of making massive suchtransportation infrastructural public investments for achieving development, growthand prosperity. It is very important to understand the economic as well as theoverall impact that investments in transportation infrastructure have had on thedevelopment of the United States. If we choose to do so, we can maketransportation infrastructural investments in a way which convey multiple benefitsextending well beyond the direct transportation benefits.

The initial historical example is the development of the National Road, also knownas the Cumberland Road, first authorized by Congress in 1806 to run westwardfrom Cumberland, Maryland. Although in 1825 Congress subsequently authorizedconstruction to continue to Jefferson City, Missouri, construction only reached asfar as Vandalia, Illinois, by 1839. At that time, allotted federal funding ran out, and

16

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 17/74

further construction ceased. The advent of railroads lessened interest incompleting the road to Jefferson City.

Another very significant early example in terms of its impact on the development of the nation is the building of the Erie Canal across New York State. Completed in

1825, it was at the time derisively known by skeptics as Governor Dewitt Clinton’s“Big Ditch.” This canal provided inexpensive, water-borne transportation linking theentire Great Lakes region to the Hudson River, New York City, and the AtlanticOcean. It made that city the business capital of the nation. It was the primaryinfrastructural investment that led to the entire ChiPitts Urban Corridor development.

Another example is the massive public/private transportation infrastructureinvestment made in the building of the Trans-Continental Railroad from Omaha toSan Francisco immediately after the Civil War. This was not an investment madeto meet existing transportation needs. It was made because the existence of the

railroad would encourage the economic development of the western United Statesand thereby facilitate the movement of people and goods, thus generating theprosperity that would validate its building.

A further example is the massive public investment in the building of the PanamaCanal. This investment was made to reduce transportation costs between theUnited States’ East and West coasts. It was an investment made to realize anopportunity to foster the economic development as well as world status of thenation.

Other examples can be briefly mentioned. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, for over 100 years, has been making public investments in support of navigation onthe Mississippi River and its tributaries. Additionally, it has made publicinvestments in the Atlantic Inter-Coastal Waterway and the Gulf Inter-CoastalWaterway. Additional examples of public investments in transportationinfrastructure are the U.S. Highway System of the 1920’s and the InterstateHighway System of the 1950’s. Finally, there is the example of the FederalAviation Air Traffic Control System.

Decline in Missouri’s Historic Role

It is also important to realize the impact of the aforementioned historicalinvestments on the shaping of Missouri’s central role, and later its decline, in thedevelopment of the nation’s transportation infrastructure.

Missouri established its initial gateway role by providing for water-borne accesswestwards on the Missouri River, for traffic delivered to it from the Ohio andMississippi Rivers. It further provided the heads of the overland Santa Fe Trail, and

17

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 18/74

the Oregon and California Trails. Additionally, through the development of theoriginal National Road toward Missouri, and the National Road’s full embodimentin U.S. Highway 40, Missouri supported the preeminent coast-to-coast highway.

Subsequently, Missouri has seen its role and recognition diminish.

The building of the Erie Canal shifted northward the original traffic route to thewest. The major route traveled across New York State and bordering the GreatLakes along what has become the ChiPitts corridor. With the subsequentdevelopment of the railroads in the period before the Civil War, the Great Lakesnorthern line was predominant, greatly reinforcing the ChiPitts corridor development. So much so was this northern line of development reinforced thatwhen the Trans-Continental Railroad was built, it was logically seen as anextension of the railroads from Chicago, across existing railroads in Illinois andIowa to Omaha and on to San Francisco.

The earlier overland trail routes from the Kansas City area were abandoned, aswell as the Pony Express route from Saint Joseph, Missouri. Although in the1920’s the National Road was extended across Missouri as U.S. Highway 40 toSan Francisco, when the Interstate System was developed, the new coast-to-coasthighway became Interstate 80. Interstate 80 follows the line of the Interstate-standard toll roads previously extending from New York to Chicago. Interstate 80then follows the line of the railroads across Iowa and the Trans-ContinentalRailroad to San Francisco.

Interstate 70, however, the successor to the coast-to-coast U.S. Highway 40primary route, does not extend to the West Coast. It ends at an insignificant

junction with North-South Interstate 15 in the deserts of Utah.

Justification of Investments – Return on Investment

The defining characteristic of all of the above-cited investments is that they werenot made to primarily address existing transportation problems. They were madeto better realize opportunities for economic growth and development. They weremade in anticipation of the benefits that would flow from them in terms of agricultural development, commerce, industrial development, and general well-

being. The investments were made to establish conditions promotive of futuregrowth and prosperity. The investments were made to realize major opportunitiesto improve our economic livelihood.

As will be elaborated upon in the subsequent sections of this paper on InterstateHighway 70, it is not timely nor within the scope of this paper to deal substantivelywith financing aspects of what is now being proposed. Nevertheless it is beingasserted that if we choose to adopt the Urban Corridor development proposals in

18

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 19/74

this paper, we might perceive ourselves to be making investments in somethingmuch greater and beneficial. We would be making an investment in our economicfuture, and yielding much greater benefits beyond the transportation realm. Wewould not be simply making expenditures for maintenance, rebuilding, andcongestion alleviation. Consequently, it would be remiss to not address financial

criteria for assessing whether a proposed financial investment is well analyzed andconsidered.

Typically, financial analyses of investment proposals center on such concepts ascost/benefit analyses, the rate return on the investment, the discounted cash flowsstemming from the investment, and the net discounted present value of the futureincome stream arising from the investment. Without attempting to elaborate onthese various measures, it is sufficient, for current purposes, to simply note thatsuch measures are conceptually valid and proper for analyzing the investmentsproposed in this paper.

There in fact exists a considerable body of literature presenting cases in whichsuch measures have been computed for various transportation infrastructureprojects. One reported “Net rate of social return on highway capital was about 35%in the 1950’s and 60’s; it declined to about 10% in the 1980’s, or just about equalto rates of return on private capital.” [3] The high initial rate of return and its later decline may be attributable to a supposition that in the earlier years, more vital,higher return–yielding highways were built. In the later years, presumably less-urgent highways were built.

Despite such measures having been computed in many cases, there exist somerather thorny issues in developing such measures.

Firstly, using such analytic measures usually requires that there be a well-definedlife for the investment. (How long would the investment remain productive?)Related to this is how to account for repairs and maintenance expenditures, andtheir prospective timing and costs.

Secondly, these analytic methods tend to presume that there is a well-definedincome stream that the investment project would generate as the return on theinvestment. However, depending on how the infrastructure investment is financed,there may or may not be such an income stream.

For example, if public finance (taxes) is used, and tolls are not levied, there isunlikely to be any specifically identifiable revenue stream generated. If privateinvestment is to be used, then a revenue stream (typically tolls) would have to begenerated to repay the private investors who financed the project.

Perhaps the most difficult matter to analytically deal with is the variety of benefitsthat investments in transportation infrastructure yield, but which are very difficult toquantify. Some examples include: how much would it be worth to reduce

19

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 20/74

congestion by some notional amount? How much would property values beincreased in the vicinity of the new transportation investment? How much wouldthese increase property tax revenues? How many new jobs would be created bynew business investments locating in the vicinity of the new highway because it isthere? (Would the investment be located somewhere else in Missouri anyway if

the highway not have been built?) The examples could go on and on.

One approach may be to look at existing examples wherein there does exist anidentifiable revenue stream in the form of tolls, and ask how much people would bewilling to pay for the immediate personal benefits that a highway project yields tothem when they use the highway. One example that can be cited is the tolls onInterstate 95 in New Hampshire. For the 18-mile distance that I-95 runs throughNew Hampshire, the automobile toll amounts to over 11 cents per mile. If anautomobile traveler gets 18 miles per gallon of gasoline, then a gasoline tax of $2.00 per gallon would have to be levied to yield the same revenue! Admittedly, inNew Hampshire’s choice to set such a high level of tolls, there seems to be a

tendency to charge however much the levels of traffic can support. Yet so manypeople want to use this highway and pay such tolls, that I-95 in New Hampshirehas four lanes in each direction for its entire length. New Jersey also has high tollson the New Jersey Turnpike, and a large number of lanes in both directions. For atrip over the New Jersey Turnpike’s 148 miles, the toll amounts to 6 cents per mile.Equivalently, a gasoline tax of $1.21 per gallon would be required from a driver toraise the same revenue. In California, State Route 91, for a 10-mile length, has tollrates varying hourly from a low of 13 cents per mile to a high of 99 cents per mile.Also in California, State Route 73, at peak times, charges almost 31 cents per milefor an 18-mile length of road.

To summarize, while it may be rather difficult to quantify the non-financial returnsfrom investments in transportation infrastructure, the real benefits at the personallevel are very large, and many people are ready to pay comparatively high rates toobtain the personal benefits that superior highways provide to them. Having saidthat, it is nonetheless quite clear that they are not willing to pay for suchinvestments from general tax revenues or gasoline taxes. The reason for thisdifference is quite obvious: People are willing to pay for what they use if andwhen they use it. They are not willing to pay for what they seldom use or perceive others using more and obtaining differential benefit to their owndisadvantage.

In the final analysis, most people, but not all, inherently perceive the return oninvestment in Interstate Highway transportation infrastructures as yielding benefitsfar greater than the costs. But because the benefits accrue very unevenly todifferent individuals, most people are not willing to further socialize the costs of such investments. They prefer that those to whom the greater share of the benefitsaccrue should shoulder a greater share of the costs. This is a major reason for theresistance to increased gasoline taxes to fund repair and development of theInterstate System.

20

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 21/74

This question of who pays what and how much naturally leads into a further discussion of how to finance the building and operation of the transportationinfrastructure that must be put in place to support the Urban Corridor. However,this discussion will be deferred until a later section of this paper on Financing.

Missouri’s Experience – Comparison of U.S. Highway 63and U.S. Highway 65

In Missouri we can see specific examples of the effects of demographic shifts andchanges in economic activity and prosperity. Significantly, these changes aredirectly related to transportation infrastructure investments, or lack thereof. Theexamples are what have been happening over the past 20-30 years along the U.S.Highway 63 and 65 corridors between Interstate 70 and the Iowa state line.

Along Highway 65, the towns of Lineville, Mercer and Spickard have beenbypassed, and show few signs of increasing economic activity. The towns of Trenton and Princeton also show few signs of increasing prosperity. Chillicotheand Carrolton appear to be prospering somewhat more, but not especially so. Bycomparison, along Highway 63, Kirksville, Macon, Moberly, and rural areas nearbyare prosperous and developing rapidly.

There are certainly many disparate factors involved in accounting for the economicdifferences along these two highway corridors. But undoubtedly, a major factor isthat Highway 65 has remained as it was engineered early in the last century, a

two-lane, and by today’s standards, a low-capacity highway. It is a difficult highwayfor commercial traffic. No one would likely locate a major job-producing venturealong this highway. Highway 63, on the other hand, has been mostly upgraded to afour-lane, divided center strip, Interstate-standard highway. Which came first, themodern highway, or the economic prosperity that attracted people and businessesto locate along this corridor, necessitating the highway development? In truth, theyhave progressed concurrently. But unquestionably, putting in place a modernhighway infrastructure has been a condition as well as a cause for the economicdevelopment that is occurring so remarkably along the Highway 63 corridor.

21

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 22/74

The Way Forward: The KanCol and Kansas City –Saint Louis Urban Corridors

Understanding Urban Corridors

In considering how to best go about building these Urban Corridors, threeimportant points need to be kept in mind at the outset.

The first point is that these Urban Corridors already exist as geographical anddemographic entities aligned along Interstate 70; and they are currentlydeveloping, albeit they are developing rather slowly as well-organized corridors.

They currently do not display significant integration as economic entities. Thus, it ispossible to speak of them as existing entities, although unrecognized andunderdeveloped. It is also appropriate to speak of “Urban Corridors” as somethingto be identified and further developed to better realize the benefits that accrue.These benefits include those arising from using the Urban Corridor concept tobetter organize our thoughts and actions in economic development matters. In thispaper, as the occasion demands, “Urban Corridors” are alternatively construed inconceptual terms, or as currently existing (albeit underdeveloped as such) realities.Otherwise, they will more frequently be treated as something to be developedbecause the benefits that accrue from the Urban Corridor concept are currently notbeing much realized.

The second point to note is that further developing the Kansas City– Columbus,KanCol, Urban Corridor would be much more significant in overall economicimpact. However, because of its size, and the various states and other interestsinvolved, promoting it and actually making significant progress in developing itwould early-on be more difficult to achieve. Moving forward with the developmentof the Kansas City– Saint Louis Urban Corridor would be much easier because of the natural advantages that Missouri already has for this development, as havebeen previously cited. Consequently, the remainder of this paper will primarily beconcerned with how to get started with the Missouri portion of the KanCol corridor.Progress on development of this latter portion would serve as an incentive and

model for the development of the full KanCol corridor.

The third point to keep in mind is that initially beginning to move forward with aKansas City– Saint Louis Urban Corridor concept does not really cost much. Thisinitial impetus, while only a starting point, could ultimately affect economic reality,unleashing real economic forces in the private sector which make investments toachieve the growth and prosperity inherent in the Urban Corridor developmentconcept. Nevertheless, as the next section of this paper makes clear, a full

22

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 23/74

exploitation of the Urban Corridor concept, for all of the benefits that accrue from it,would require massive investment in the I-70 transportation infrastructure in theKansas City– Saint Louis Urban Corridor.

In summary, while Urban Corridors are certainly an economic reality, they also

represent a state of mind in certain respects. It is timely to move forward with our thinking in terms of Urban Corridor concepts.

Steps to Be Taken

For current purposes, it is sufficient to realize that in moving forward with thedevelopment of the Kansas City– Saint Louis Urban Corridor, promotion is the vitalstarting point. Through public relations, educating the citizenry, and relatedmeasures, we can promote the concept that Missourians come together and

actively pursue a more unified social and economic community, as well as a newmodel of urbanization. It would involve a cooperative, coordinated, integrated,interlinking of the people, communities, and economic activity of those who livealong a rapidly developing Urban Corridor into a larger social and economiccommunity. It would transcend, but not otherwise affect, existing county, town, or other civil or governmental boundaries or jurisdictions, except to urge people livingwithin them to work together more closely and collaboratively. This is not economicplanning. It is better enabling and empowering community and economicdevelopment and well-being, as well as addressing existing urbanization androadway congestion problems.

Obviously, there is a great amount of public education that needs to be done to sellthis concept and generate support for it. Before people would buy into it, andsupport it, they must understand it in all of its aspects. This is going to requireextensive analytical cost / benefit studies and further comparison of the corridor model of urban development with the current agglomeration model. Comparativeenvironmental studies would be needed, along with further studies of thecomparative impacts of both models on nearby and distant rural areas and smaller cities and towns. Further studies on the potential impact on property values wouldbe necessary.

Besides these public analytical studies, which are aimed at better informing people

about the corridor concept, it would be necessary to bring closer together thosepeople along the corridor who are already promoting economic development alongthe corridor. This is most important. Relevant to this are many business groups,fraternal groups, civic organizations, Chambers of Commerce, private and socialand other community organizations and governmental organizations, as well asindividuals. These all involve key people who are actively working to improveeconomic conditions in their various communities and circles of interest and

23

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 24/74

acquaintance. By and large, many of these now direct their efforts largely atbettering their respective local communities.

When it comes to attracting business investment, such efforts by local boosterscan give the appearance of competition among those who could better present

themselves somewhat differently. Those promoting investment and economicdevelopment could present themselves firstly as part of the Missouri communityand economic environment, then the Urban Corridor community and economicenvironment, and finally as part of their local community and economicenvironment. These local connections would be integral parts of larger, closely-knit, highly economically integrated, mutually supporting, collaborating,cooperating, coordinated economic whole.

Working Collaboratively As A Region and State

If, for example, Saint Louis and Kansas City were seen to be competing for thesame investment project by a large national or multinational company, then theywould likely each be perceived as promoting themselves at the expense, and tothe detriment of, the other. This is more likely to produce a lose/lose/lose outcome:a loss for Saint Louis, a loss for Kansas City, and a loss for Missouri. On the other hand, if both cities were to first encourage the company to invest and locate inMissouri, then to promote investment and location along the Kansas City– SaintLouis corridor, and as a subsidiary matter, invest and locate in their own city, thena successful outcome for Missouri, the corridor, and one city or the other is muchmore likely to occur. For the city that did not win, well, probably they would not

have won anyway. But in a larger sense, albeit smaller way, they still would havewon. As a part of the larger Missouri and Urban Corridor communities, thesuccesses and increased prosperity of any local community contributes to thebetterment of the whole. Finally, for the city whose bid for the investment did notsucceed, they could look forward to better prospects in the next case, because inan Urban Corridor atmosphere of community mutual support, their prospects wouldbe enhanced by the efforts of the broader community.

As a starting point in moving forward with the Urban Corridor development, this isthe sort of thinking that must come to animate the efforts of all who are promotinginvestment and economic development along the Urban Corridor.

Prompting people to work together more cooperatively and collaboratively can beachieved by actually bringing the key people into more frequent interaction witheach other in their daily work, in attending conventions, sharing booths at tradeshows and investment seminars, or traveling together in foreign trade missions.The list could go on and on. However, the idea is clear: Missourians couldsubstantially benefit if they find ways to demonstrate that the Missouri leadersalong the corridor are working cooperatively and collaboratively to improve

24

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 25/74

economic conditions along the corridor, for the betterment of new investor members of the corridor community, as well as for the current members of thecorridor community.

In summary, at this initial stage, Missourians face a vital opportunity to move

forward with the Urban Corridor development by getting together with Missouri’skey players in economic development and transportation development. Gettingtogether could be the first step to begin promoting the Urban Corridor concept and

justifying the investment in transportation infrastructure that it requires.

25

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 26/74

The Way Forward: The Interstate 70Transportation Infrastructure for Urban Corridor

Economic Development

Recent Planning for Interstate Highway 70

A few years ago, the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT) initiated apraiseworthy public consultation process concerning what to do about InterstateHighway 70, particularly the congestion that was ever increasing. Threealternatives were put forward for consideration.

One alternative would be to simply increase the capacity of I-70 by widening it tothree lanes or more throughout its full length. This would require substantialrebuilding of overpasses, bridges, and interchanges, as well as the roadway itself.This would all have to be done while the existing highway traffic had to beaccommodated, causing further congestion in many already congested locationswhile construction was in progress in that area. Nevertheless, this alternative hasadvantages, in that it could be implemented gradually as funding permitted,upgrades could be first put in place in the most congested areas, and it could bereadily seen by the public as trying to do something immediately about the worstproblem areas.

A second alternative would be to upgrade U.S. Highway 50 to full Interstate-standard throughout its entire length. Highway 50 is currently approximatelyInterstate-standard for about 70 miles eastward from Kansas City, and a few mileswestward and eastward of Jefferson City. This alternative would draw traffic awayfrom the existing I-70, thereby alleviating congestion. However, constructionbetween Saint Louis and Jefferson City would be relatively expensive because of unfavorably hilly terrain, and would probably require bypassing many towns. Also,the routing into southwest Saint Louis would be problematic for through traffic toand from Illinois.

The third alternative presented would be the building of a new I-70 highway,presumably along an open field pathway north of the existing highway. Again, itwould probably be far enough northward to go through open land, and avoid thesubstantially higher land acquisition costs closer to the existing I-70. And it wouldpresumably afford direct Interstate highway services to a string of towns across thestate which are now somewhat more distant from Interstate 70. Finally, and mostimportantly, at its interchanges and frontage roads, a new I-70 would open tens of thousands of acres of relatively low-cost land for industrial and commercial

26

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 27/74

development. Such land would be extremely attractive for business developmentbecause of its ready access to a new Interstate-standard highway. Equally,hundred of thousands of acres of low-cost land would be made much moreattractive for urban development.

Although the Missouri Department of Transportation merits commendation for itsefforts to elicit public input into the decisions on how to address the problems withInterstate 70, it appears that an economically inferior alternative has won out. Itappears that the decision has been made to substantially widen and rebuild theexisting I-70. I perceive that this outcome is the result of two considerations.

First of all, as Missouri’s Department of Transportation is charged with building andmaintaining the state roadways, the Department is constrained to find the mostcost-effective engineering solution to problems which present themselves, such asthe I-70 congestion problem. It is neither explicit nor implied that the Departmenthas a responsibility to look into matters of urbanization policy or economic

development in making such decisions on highway development. These are theresponsibility of others in the state government. Yet, these latter matters are soclosely intertwined with transportation infrastructure development that suboptimaldecisions are likely to result from not taking all of these relevant issues intoconsideration.

The second consideration leading to the decision not to pursue the building of anew I-70, I am sure, is the matter of cost. It is well known that in Missouri, and inthe entire country, it is increasingly difficult to find money to even properly maintainexisting highways and bridges, much less build new ones. The Interstate System,largely designed and built over 50 years ago, is overloaded and much of it is wornout. So long as it is thought that road building and maintenance must be financedby taxes, and fuel taxes at that, the situation is only likely to deteriorate in thecurrent environment. There are many factors contributing to this, but it is not myintention to address these matters in this paper, except to note one very importantpoint.

If discussions about how to ensure future growth and development opportunities,and in particular, highway maintenance, repair, and congestion matters, aredominated at the outset by cost and finance issues, then there might never be anyprogress. We must first consider what our future infrastructure needs might be,without undue regard to cost and financing. If we find a development that issufficiently attractive and desirable, then we can study whether we can find a wayto afford the cost and finance the investment. For the current purposes, it issufficient to say that if we find that an enhanced Urban Corridor developed aroundan improved transportation infrastructure is sufficiently attractive and desirable, inthe face of whatever costs, then we might be able find a way to finance theinvestment, either publicly, privately, or in combination. In order to launch such amassive undertaking, we must consider future possibilities and which options willlead to improvement, carefully identifying the most effective way forward.

27

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 28/74

Proposals for New Interstate Highway 70 TransportationCorridors

So, what exactly is being proposed as the new transportation infrastructure for theSaint Louis– Kansas City Urban Corridor?

Let us consider the traffic volume along I-70 today, and include the natural trafficdemand growth that can be expected in the future even if the Urban Corridor concept is not supported. Additionally, let us include the much greater trafficdemand that would be induced by the economic development resulting from theUrban Corridor implementation. The U.S. highway system which begandevelopment in the 1920’s was overwhelmed by the time of the 1950’s. Similarly,the Interstate Highway System designed in the 1950’s is in many areas

overwhelmed today. It appears that any new highway development tends tobecome overwhelmed in about 40 years. Therefore, I shall take approximately 40years as a planning horizon.

Considering the three alternatives put forward by the Missouri Department of Transportation, over the next 30 to 40 years, or even sooner, Missouri may need, if it desires high growth and prosperity, to implement aspects of all three alternatives.The first and most urgent transportation priority is to build a new Interstate-standard highway between Saint Louis and Kansas City. Subsequently U.S.highway 50 should be upgraded through its entire length to Interstate-standard. Inthe meantime, as necessary for repair and conservation, and to meet very urgent

congestion problems, the existing I-70 can be addressed. The latter efforts neednot be primarily directed at expensive increases in the capacity of the existing I-70.The primary focus could be to drain off new traffic and existing traffic to the twonew alternatives. We should not want to attract more traffic to a direct upgrade of the existing I-70, nor to attract more traffic to the existing approaches to SaintLouis and Kansas City. The latter traffic increases should be served by the twonew highways into these cities.

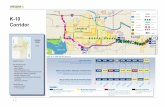

The result should be that by year 2050 or so, Missouri would have three Interstate-standard highways providing the backbone structure for the Urban Corridor between Kansas City and Saint Louis, along with a complementary provision for

railway traffic. For convenience purposes, I will refer to them as the existing I-70, acompletely new I-70 North, or I-70N, and a renamed U.S. 50 which I will call I-70South, or I-70S. This, in part, follows the established convention in which I-35 splitsinto I-35W through Minneapolis, and I-35E through St. Paul, Minnesota.

The new I-70N could follow an alignment similar to the existing U.S. highway 50,the renamed I-70 South. That is to say, I-70N can optimally be about 20 miles or so north of existing I-70. Without being prescriptive, it might, for example, follow an

28

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 29/74

alignment from northern Saint Louis through such towns and cities as Mexico,Moberly, then Marshall or Carrollton to Excelsior Springs and connecting to I-35/ I-435 into Kansas. As the existing I-270 connector in northern Saint Louis to I-70 inIllinois is already congested, another crossing of the Mississippi River would likelybe necessary, probably to the vicinity of Alton, Illinois, and the junction nearby of I-

70 and I-55. For the time being, this could be seen as a part of the subsequent,greater KanCol Urban Corridor development. Interestingly, these developments, if they can be realized, would likely prompt Illinois to promote further development inthe Chicago–Saint Louis corridor and the KanCol corridor.

In considering this proposed Urban Corridor with its three parallel Interstate-standard highways, it is important to recognize the tremendous potential for economic development that such a plan presents. I am talking about a band,roughly 50 miles in breadth across the 250-mile width of central Missouri, withevery location within 10 to 20 miles of an Interstate-standard highway. This wouldbe, in every respect, a very attractive region. To the north of the corridor would be

green agricultural regions. To the south of the corridor would be the green forestedregions of Missouri’s recreational lakes and rivers and the Ozark Mountains.

I am also talking about a new transportation corridor that is environmentallysensitive, in that I-70N and I-70S would tend to maintain substantial green areasbetween themselves and the existing I-70. I-70N should enable long-term growthand embody an extra-wide median separator for future expansion, undergroundutilities, such as optical fiber cables, and future high-speed passenger and/or freight services via railway, monorail, or whatever is developed in the future.

With respect to the new I-70N to be built through open country, the land acquisitioncosts may be relatively low. The entire length would present thousands of veryattractive, relatively low-cost building areas well served by superior transportationfacilities. It would be extremely attractive for businesses seeking new productionsites and office parks. Near the interchanges and along the frontage roads, therewould be thousands of low-cost business building sites with very close access toInterstate-standard transportation. Additionally, the building of I-70 North, and thenearby businesses it would attract, would also make the inexpensive land near thehighway very attractive for urban development. The business and commercialdevelopment, together with the residential development that would spring up,attracted by the businesses, would constitute the building of the Urban Corridor.

On the other hand, the alternative of simply increasing the capacity of the existingI-70 would only attract more traffic to that sole roadway between Kansas City andSaint Louis, shortly creating new congestion problems, and failing to create themuch greater private investment and economic development that I-70 North wouldproduce.

Can there be any doubt that if the alternative of simply upgrading the existing I-70is implemented, then soon after the expansion is completed, we would again be

29

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 30/74

faced with renewed congestion and needs to alleviate it? And at that time, theproblems would be even more intractable because of the increased urbanizationthat would have occurred alongside the existing I-70. Finally, we would have, in theinterim, foregone the much greater economic growth and development that wouldhave occurred if the low-cost land along an I-70 North and its associated freight

and passenger rail infrastructures had been more readily accessible to privateinvestment and development.

Getting started with the building of I-70 North, at this stage, would require asubstantial public education campaign to present and justify the reasons for goingforward with this project. In large measure, this would require the same initialefforts as described above for moving forward with the Urban Corridor concept.

30

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 31/74

CORRIDORS OF THE FUTURE PROGRAM

One of the more significant recent transportation development events is theapproval announcement by the Federal Highway Administration of the Interstate 70Corridors of the Future Phase II Application [4]. This Application is a joint proposalof the Departments of Transportation of Missouri, Illinois, Indiana and Ohio for “Interstate 70 Dedicated Truck Lanes”. The dedicated “Truck-Only Lanes” (TOL’s)are envisioned to be the existing dual-use (automobile and truck) lanes of theexisting I-70. The plan suggests the building of new automobile lanes alongside,but separated from, the existing I-70 lanes, which would become Truck-OnlyLanes. The Application was put forward under the leadership of the IndianaDepartment of Transportation, and was approved for initial funding totaling to $5

million.

What is being proposed is to rebuild the existing I-70 highway in situ , along with itsoverpasses and interchanges, while it remains in operation, and to build additionaltraffic lanes alongside it for automobiles. This is quite at variance with what hasbeen proposed in the earlier sections in this paper regarding the Urban Corridor concept and a new I-70 North transportation infrastructure including provision for rail and freight passenger services.

At this point, we are faced with the decision of whether it is better to move forwardwith addressing the congestion problems on I-70 with a completely new UrbanCorridor multimodal transportation infrastructure, or installing Truck-Only Lanes inthe existing I-70 corridor. This involves looking at the Corridors of the Future

Application more closely, in comparison with the alternative of moving more freightby rail. The remainder of this paper will be largely addressed to this topic, alongwith financing issues. I shall now address the issue of what are the relative meritsof the Urban Corridor concept, as proposed in the preceding sections of this paper vis-à-vis the “Truck-Only Lanes” (TOL’s) proposal. We must ask ourselves whatwould be the better course of action. Answering this will ultimately require that weaddress issues relating to increased movement of freight by enhanced rail rather than by relying on Truck-Only Lanes.

The Introduction of the Corridors of the Future Application states:

“Our shared goal is to reduce congestion and improve safety on the(I-70) Corridor and, thereby, improve commerce and expandeconomic growth to our region. Our vision is to accomplish this bydeveloping a dedicated truck-only lane (TOL) Corridor along theapproximate 800 miles of I-70 that crosses our four states.” [5]

31

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 32/74

The proposal presents three major sections entitled Clear Need , Clear Solution,and Clear Path to Success, and includes many statistical tables and figures tosupport each section.

Overall, with the exception of one major aspect, the proposal embodies well- justified, well-documented and well-presented statements of the needs, major design aspects, and implementation plan for moving forward with the development.However, while Truck-Only Lanes are the proposed designed solution, and theproposal documents the use of limited access lanes elsewhere in the country, mostof the examples cited are high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes to encouragecarpooling. Further, for reasons that the remainder of this paper will make clear, itis dubious that the Truck-Only Lane conceptual design is the most cost-effectivedesign. This is especially true when one takes into consideration the broader economic benefits to be achieved as outlined in previous sections of this paper presenting the Urban Corridor concept.

Additionally, to the extent that benefits are sought through reduced mixing of carsand trucks on the same roadway, there is another design alternative that seemsnot to have been considered. The motivating arguments for the design proposal for Truck-Only Lanes are relief from congestion, and safety benefits deriving fromseparating freight movement by large trucks from automobile movement. Thealternative of separating long-haul freight from trucks through relatively greater useof railways seems not to have been considered.

Finally, the Truck-Only Lane proposal presents the potential for technologicaladvances that may be forthcoming with a new, modernized truck highwayinfrastructure, such as “high speed electronically controlled vehicle operation, trucktrains that move cabs between yards on an automated conveyance system wherethey are assembled and dissembled, etc.” [6] However, many of the sameadvantages are potentially more readily and economically realizable with a new,modernized railway infrastructure, either instead of or in addition to Truck-OnlyLanes.

The second paragraph of SECTION 1: Clear Need of the Application documentstates that the “proposed truck-only lane paradigm offers the prospect that theproject can provide a corridor of such length and breadth as to change America’snational interstate transportation model” (Italics added). [7]

The next paragraph states that the “vision of this project is the vision of the future,providing economies of scale required to influence, and potentially shift freightmovements across the Midwest and the United States” (italics added). [8]

The Application document additionally comments on the 800-mile length of theproposed Truck-Only Lanes:

32

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 33/74

“This distance will, in some cases, make the Corridor an attractive,cost-effective alternative to rail, enabling rail loads to be morecost/effectively transferred to trucks in Kansas City or Columbus,bypassing the significant rail congestion in Chicago that is adetriment to time-sensitive shipments.” [9]

The above statements clearly indicate that what is at hand here is a developmentthat would likely culminate in a change in our country’s future freight movement asmomentous as the decision in the 1950’s to allow trucks onto the new Interstatehighway system. It is additionally stated in many places throughout the Applicationthat it is not a good idea, for safety and other reasons, to mix automobile traffic andtruck traffic in the shared usage of the same highway. In retrospect, we may askwhether we made a mistake in earlier years in providing inducements to shiftfreight from railroads to highway trucking. But that is likely to lead to a fairly sterilediscussion. So also it is sterile to discuss whether a mistake was made when webuilt the Interstate Highway System in such a fashion that it resulted in the

agglomeration model of urban growth. The real situation is “this is where we arenow,” presenting the question of, “How do we best move forward?” Morespecifically, the real question before us now is whether, considered from variousaspects, it is better to try to move relatively more freight on an enhanced highwayor on an enhanced railroad infrastructure.

Finally, the Application places great emphasis on the automobile drivers’ distasteand discomfort with sharing a highway with trucks. But, as a solution, the idea of Truck-Only Lanes is oversold, in that smaller trucks would still be allowed in theautomobile lanes. More importantly, it would still be the case that there would be alltypes of trucks driving along with automobiles on most parts of the InterstateSystem. Trucks sharing the road only becomes a problem when congestion getsout of hand and when the proportion of trucks on the highway in relation toautomobiles gets so high that the automobile drivers begin to feel hemmed in. Theproblem is not trucks, per se. The problem is lack of highway capacity andcongestion. The answer is to reduce relatively the number of trucks on the highwayshared with automobiles, but not necessarily by the introduction of Truck-OnlyLanes.

It is not exactly clear why the four state Departments of Transportation havechosen this particular approach. There are probably a variety of reasons of greater or lesser appeal to the various Departments. In Missouri’s case, it seems clear thatthe Department is wary of the problems in financing the project in the face of widespread public distaste for tolling of transportation facilities. It wouldpresumably be easier to obtain legislative acquiescence to tolling of trucks to aidthe financing of a truck-only highway. Yet, as will be addressed in the subsequentFinancing section of this paper, selective user fees in the form of modern electronictolling is the only broadly feasible and equitable long-term solution to the highway-financing conundrum.

33

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 34/74

In Indiana’s case, there remains great interest in extending Interstate 69 to theMexican border. (See this paper’s subsection on Missouri’s Role.) If the I-70 truck-only lane proposal is implemented, it would greatly promote Indiana’s case for implementing the extension of I-69 and making Indianapolis the hub for adeveloping truck-only highway system.

In any case, it is apparent, that while the state Departments of Transportationgenerally have a responsibility with respect to railroads within their respectivestates, they have a much larger constituency in the trucking industry than in therailroad industry. But can this be allowed to be a justification for providing thetrucking industry competitive support over and above the railroad industry? Didn’tthe United States already make this same mistake once (in the 1950’s) whensanctioning the Interstate System to be used for shifting freight away from therailroads, with all of the ensuing complications that are now leading to a proposalsfor freight-only highways?

To summarize briefly, the Corridors of the Future Phase II Application documentpresents very well the case for enhanced infrastructure for freight movement. Butthe main points that are made for providing Truck-Only Lanes on the highwayapply equally well for enhanced rail facilities. Most of the benefits of Truck-OnlyLanes are better achievable from moving a greater portion of freight by animproved-technology railroad infrastructure. This, incidentally, is the same situationthat occurs with respect to freight movement by rail and high-speed passenger rail.Again, similarly, there are complementary as well as contrary issues between railmovement of freight and high-speed passenger rail. So also there are such issuesbetween truck and rail movement of freight. The challenge is to determine the mostappropriate, or optimized balances, partially by ensuring level playing fields for allparticipants, including the broader public, while securing maximum environmental,economic, and social benefit.

I shall now examine more concisely the nature and relative benefits of movingmore freight by rail rather than more by long-haul trucking.

34

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 35/74

OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE

Introduction

This section of this paper presents a broad treatment of the comparative benefitsthat would be offered by an enhanced railroad infrastructure in the previouslyproposed Urban Corridor development. Good references for gaining a deeper understanding of key issues in developing an integrative approach to nationaltransportation infrastructure are contained in Future Options for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways [10] and Freight - Rail Bottom LineReport [11].

Environmental Opportunities

There are various legislatively mandated requirements that any project, such asthose discussed in this paper, must satisfy. It is not the purpose of this paper to gointo these specific issues in any great detail. This subject is adequately well-covered in the Corridors of the Future Phase II Application [4] document; at leastinsofar as current requirements are concerned. However, it is only reasonable withrespect to the future to adopt a planning stance that anticipates future

developments in this area, especially in instances in which such can be done atlittle or no alternative additional costs.

With regard to possible future eventualities, we all know that there is increasingpublic concern about all types and sources of pollution, particularly with respect totransportation, air, water, and noise pollution.

There are widespread and conflicting views about the extent to which thebyproducts of internal combustion engines fueled by petroleum or other carbonproducts contribute to air pollution, and especially whether or not this is asignificant factor affecting global climate change. Indeed, there are even differingviews on whether carbon dioxide should be considered an air pollutant. Yet we arehearing an increasing outcry for reducing our “carbon footprint” and for introducingcarbon taxes.

In any case, it is well recognized that, per ton-mile of freight delivered, usingtechnologies currently in place, rail transport of freight produces substantially lessair pollution. Not only that, but because alternative power sources (see sub-section

35

8/8/2019 Jerome Day Paper on I-70 corridor

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/jerome-day-paper-on-i-70-corridor 36/74

below on Electric Power ) are less likely to be available to trucking, rail freight canbecome even more efficient and environmentally friendly.

Regarding water pollution, this is not a significant reason for preferring rail freightmovement to truck movement, except for minor matters. The wearing down of tires

leaves rubber residue on the highway, which subsequently becomes part of therainwater runoff. Also, the petroleum-based (asphalt) surfaces on some of theroadways, through wear, become a pollutant. Finally, where snow and ice are awinter problem, the use of various melting compounds (primarily salt) is a cause for concern to some people.

One reason for co-locating a railway in the median of a highway is that it better enables noise control measures to be implemented if railways and highways areco-located.

What may be taken as the final word on this issue is contained in the American