Jane Somerville

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

joao-antonio-granzotti -

Category

Social Media

-

view

497 -

download

0

Transcript of Jane Somerville

Profiles in CardiologyThis section edited by J. Willis Hurst, MD and W. Bruce Fye, MD, MA.

Jane Somerville

Carole A. Warnes, MD, FRCP, FACCDivision of Cardiovascular Diseases and Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic,Rochester, Minnesota, USA

Address for correspondence:Carole A. WarnesFrom the Division of CardiovascularDiseases and Department ofInternal MedicineMayo ClinicRochester, MN 55905, [email protected]

Jane Somerville (Figure 1), born Jane Platnauer in London,England, in 1933, can arguably be described as the mother of‘‘Grown up Congenital Heart Disease (GUCH).’’ Althoughofficially retired, she continues to travel the world andpursue her passion of clinical teaching of this sub-specialty.There can be no doubt she has trained more fellows incongenital heart disease than any other physician, so muchso that a large fan club of ex-fellows called ‘‘the Unicorns’’gathers at every World Congress of Pediatric Cardiology (ameeting she founded) to celebrate her life and work. Shepursued her interest in adult congenital heart disease at atime when the focus of the world was on pediatric cardiologyand cardiac surgery; no one having recognized the need totake care of this increasing population as they grew up. Inan era when very few women physicians were recognized,she became internationally renowned as a world leader inher field.

Her father was a theater critic, and her mother, a stronginfluence in her life, worked on Vogue magazine. In WorldWar II, Somerville was sent to a boy’s school, which shebelieves, helped shape her life and her later interactionswith the male-dominated medical profession. She went onto study science at Queens College, London, and wasaccepted by Guy’s Hospital Medical School when it wasonly the third year that female students were admittedand comprised only 8% of the class. She still recalls theexcitement surrounding a medical school lecture from thevisiting US surgeon, Dr. Alfred Blalock of Johns Hopkins.He described his success with the Blalock Taussig shunt, apioneering surgical procedure for the treatment of cyanoticheart disease (usually tetralogy of Fallot) that transformedthe lives of children with this form of congenital heartdisease. The novel extra-cardiac operation turned themfrom blue to pink in minutes. She decided then to become acardiac surgeon and worked for Sir Russell Brock, a leadingsurgeon of the day.

She remembers long and difficult surgical procedures,high surgical mortalities, and harrowing nights withseverely ill children. She recognized her limited techni-cal skills as a surgeon and changed course to become acardiologist. In the late 1940s, she met her future husband,Dr. Walter Somerville, a distinguished cardiologist whomshe married in 1957. He introduced her to Dr. Paul Woodwho captivated her with his diagnostic clinical skills and log-ical deductive reasoning. In 1958, she became a registrar atthe National Heart Hospital where she later was responsibleto Paul Wood. This was an exciting time in congenital heart

disease when much was being discovered in the area of clin-ical diagnosis and cardiac catheterization. Wood, a masterclinician, taught Somerville about meticulous interpretationof clinical signs and auscultation in relation to physiologyand hemodynamics. Fascinated by congenital heart disease,she recognized the need to understand pediatric cardiologyand, against the rules, escaped periodically to work at theHospital for Sick Children in Great Ormond Street in Lon-don, learning about infant medicine and surgery with Drs.Bonham Carter and David Waterston.

Despite the challenges of being a woman cardiologist inthat era, Dr. Somerville ‘‘broke the glass ceiling’’ and wasappointed as a Consultant at the National Heart Hospital in1967. She recognized that following the huge successes ofpediatric cardiac surgery there was a rapidly increasingpopulation of adolescents and adults with congenitalheart disease requiring informed medical care. Theirnew medical issues were challenging and serious, oftenneeding reoperation, and cardiologists were not trainedto deal with their special problems. Thus, the conceptof GUCH was born. Pioneering cardiac operations wereundertaken at the Heart Hospital by her friend and surgicalcolleague Donald Ross with whom she wrote many ground-breaking articles,1–7 including the first report of the useof a homograft aortic valve to repair pulmonary atresia in1966.2 She began to understand the unique needs of thispopulation, and became determined to develop a specialhospital unit to provide care. When she set her sightson a goal, no obstacle got in her way. Always feisty andprepared for battle, she succeeded in raising money and in1975 opened the world’s first dedicated ward for childrenand adolescents with congenital heart disease: appropriatelynamed after her mentor, the ‘‘Paul Wood Ward.’’ This was aunique environment where children and adolescents couldmingle with each other and their families. It included an areato play for younger patients with a dedicated play leader whocould help them talk through their problems, and a kitchenwhere adolescents and families could make coffee or have asnack. Older adolescents enjoyed the interactions with theyounger patients, often trying to help and support them.Even patients in their 20s needing admission wanted to goto the Paul Wood ward rather than a regular adult ward, andit was hard to deter them.

Always passionate about patient care and teaching,Dr. Somerville was a hard task-master. As well as quicklypointing out others’ shortcomings, she could be self-critical;indeed a sign on her office door read ‘‘The courage to beimperfect.’’ Teaching was an important part of her clinical

Received: July 2, 2007Accepted with revision: August 17, 2007

Clin. Cardiol. 31, 4, 183–184 (2008) 183Published online in Wiley InterScience. (www.interscience.wiley.com)

DOI:10.1002/clc.20279 2008 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Profiles in Cardiology continued

life: she traveled worldwide and many fellows went toLondon to study with her. Her ward rounds were legendary:though she was often late, fellows stood to attention andwaited patiently for the ‘‘arrival’’ knowing that great clinicalteaching was to follow and there was much to be learned.Any debate about the nuances of a murmur or heartsounds, and the phonocardiogram was produced so theissue could be resolved. Students could not be faint ofheart, since if they had not studied, they might be loudlychastised, and the morning rounds might last until 3 PM.when hypoglycemia might supervene. Those who stayedthe course were rewarded with her generosity, support, andfriendship.

In 1980, she held the first World Congress of PediatricCardiology in London (an idea she conceived in the bath,she relates), which was a huge success, and enhanced thevisibility of the subspecialty. She later united this meetingwith the Congress of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery to enhancecollaboration and research between the two disciplines.

In 1989, the National Heart Hospital was closed andabsorbed into the Brompton Hospital. This was not an easytransition, but undeterred, with her usual determination,she reestablished a special ward for the adolescent andadults, ultimately named the Jane Somerville GUCH Unitin 1996. In the early 1990s, she was the founder, and thenChairman, of the European Society of Cardiology WorkingGroup on GUCH. She developed, and became Presidentof the GUCH Patients Association in 1994 and secured itsfunding from the British Heart Foundation. In 1995, shegave the first Paul Wood lecture at the British CardiacSociety appropriately titled ‘‘The Master’s Legacy.’’ She wasappointed Professor of Cardiology in 1998 and retired fromthe Brompton Hospital in 1999.

Despite this busy and successful professional life, Janeand Walter had 4 children, with whom she is very close, andshe now has 4 grandchildren. Her beloved Walter passedaway in 2005. She has many interests outside medicineincluding roof gardening, antique collecting, particularlyopaline glass and silver, and opera. Never idle, she stilllectures worldwide with wit and wisdom, and helps establishGUCH services around the world. When asked the 3 thingsof which she is most proud, she reports ‘‘My family,marrying Walter and my Unicorns everywhere.’’ The 100-strong group of ex-fellows was named the Unicorns becauseof Somerville’s characteristic response to someone wholacked imagination was to prod her forefinger repeatedlyto her forehead and ask ‘‘Have you ever seen a unicorn?’’

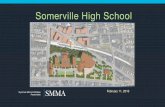

Figure 1: Jane Somerville (1933 –).

Her Unicorns are now scattered all over the world,9 manyhaving established Adult Congenital Heart units of theirown, continuing to spread the passion for this uniquesubspecialty that she inspired in them. Truly, she is themother of GUCH.

References1. Somerville J: Gout in cyanotic congenital heart disease. Br Heart J

1961;23(1):31–342. Ross DN, Somerville J: Correction of pulmonary atresia with a

homograft aortic valve. Lancet 1966;2:1446–14473. Somerville J: Management of pulmonary atresia. Br Heart J

1970;32:641–6514. Somerville J: Congenital heart disease–changes in form and

function. Br Heart J 1979;41:1–225. Taylor NC, Somerville J: Fixed subaortic stenosis after repair of

ostium primum defects. Br Heart J 1981;45:689–6976. Warnes CA, Somerville J: Tricuspid atresia in adolescents and adults:

current state and late complications. Br Heart J 1986;56:535–5437. Bull K, Somerville J, Ty E, Spiegelhalter D: Presentation and attrition

in complex pulmonary atresia.[see comment]. J Am Coll Cardiol1995;25:491–499

8. Somerville J: Paul Wood lecture. The master’s legacy: the first PaulWood lecture. Heart 1998;80:612–618, discussion 618–619

9. Somerville J: Spotlight: Jane Somerville, MD, FRCP, FESC.Interview by Robert Short. Circulation 2007;115:f61–f63

184 Clin. Cardiol. 31, 4, 183–184 (2008)C.A. Warnes: Jane SomervillePublished online in Wiley InterScience. (www.interscience.wiley.com)DOI:10.1002/clc.20279 2008 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.