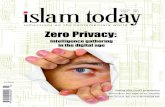

islam today - issue 15 / January 2014

-

Upload

islam-today-magazine-uk -

Category

Documents

-

view

228 -

download

5

description

Transcript of islam today - issue 15 / January 2014

Saving Muslim Women?

Prophets and Profit

The Mystery of the Holy Grail

UK £3.00

issue 15 vol.2January 2014

Mandela’s legacy must live on

2

Disclaimer: Where opinion is expressed it is that of the author and does not nec-essarily coincide with the editorial views of the publisher or islam today. All infor-mation in this magazine is verified to the best of the authors’ and the publisher’s ability. However, islam today shall not be liable or responsible for loss or damage arising from any users’ reliance on information obtained from the magazine.

January 2014

Issue, 15 Vol, 2 Published Monthly

islam today magazine intends to address the concerns and aspirations of a vibrant Muslim community by providing readers with inspiration, information, a sense of community and solutions through its unique and specialised contents. It also sets out to help Muslims and non-Muslims better understand and appreciate the nature of a dynamic faith.

Publisher: Islamic Centre of England 140 Maida Vale London, W9 1QB - UK

ISSN 2051-2503

Managing Director Mohammad Saeed Bahmanpour

Chief Editor Amir De Martino

Managing Editor Anousheh Mireskandari

Political Editor Reza Murshid

Health Editor Laleh Lohrasbi

Art Editor Moriam Grillo

Layout and Design Sasan Sarab – Michele Paolicelli

Design and Production PSD UK Ltd.

Information [email protected]

Letters to the Editor [email protected]

Contributions & Submissions [email protected]

Subscriptions [email protected]

www.islam-today.net

Follow us on facebook www.facebook.com/islamtodaymag

Ahmad Haneef

Alexander Khaleeli

Ali Jawad

Batool Haydar

Cleo Cantone

Francis Gilbert

Frank Julian Gelli

Hamid Waqar

Mohsen Biparva

Muhammad Reza Amirinia

Contact us

Editorial team

Back CoverA 30 feet steel sculpture to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Mandela’s capture. Designed by Marco CianfanelliLocated in Howick, South Africa

CoverHand print of Mandela 46664 was Mandela’s prison numberin Robben Island

Islamic Centre of England

3

From the Editor5 Prisoner ‘46664’

News6 News from around the world

Life & Community 10 Sukuk - A Progression of Islamic

Finance

Hamid Waqar presents an in-depth expla-

nation of the ins and outs of one of the

most popular Islamic contracts; sukuk

14 Me, myself and God

Batool Haydar thinks that the best ‘me

time’ is that which is spent on nurturing

the essential relationship our soul has

with God

Arts20 Masterpiece

‘30 Days of Running in the Space’- Ahmed

Basiony

21 In the spotlight

Nermine Hammam - Digital manipulation

and painting

22 Photography

Khalil Nemmaoui, Morocco

The Place to BE

The Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar

Hajj: The Journey Through Art

23 Heritage

The Ferozkoh (Turquoise Mountain)

exhibition - Leighton House

Addendum

Moderate Enlightenment, 2007- Gouache

on wasli Imran Qureshi (born 1972)

24 Leighton House Museum

Obsessed with an idealised Islamic past,

Lord Leighton’s legacy is where east meets

west says Cleo Cantone

Review28 Saving Muslim Women?

Why did Afghan women not throw off

their burqas after the Taliban were over-

thrown? Mohsen Biparva finds the answer

in a new book by Lila Abu-Lughod

Cover32 Mandela’s legacy must live on

Remembrance ceremonies for Mandela

have attracted a plethora of world leaders

to South Africa. Reza Murshid questions if

their presence does justice to the memory

of Mandela

Feature 36 Migration in the name of faith

The inclusive paradigm by which Islam

views all peoples and nations has encour-

aged Muslims to look outwards and inter-

act with other cultures, says Ali Jawad

Opinion 40 Education for Sale?

Changes to our education system have

helped to create some very wealthy people

instead of helping needy students, believes

Francis Gilbert

Faith 44 Prophets and Profit: an Islamic

perspective on wealth

Alexander Khaleeli explains the Prophetic

narration, ‘This world is a prison for the

believer and a paradise for the disbe-

liever.’

48 From Knowledge to Belief

There is a close relation between knowl-

edge, belief and action. Ahmad Haneef

traces the process of acquiring belief and

the path leading to it

4

Glossary of Islamic Symbols The letters [swt] after the name of Allah [swt] (God), stand for

the Arabic phrase

subhanahu wa-ta’ala meaning: “Glorious and exalted be He”.

The letter [s] after the name of the Prophet Muhammad[s],

stands for the Arabic phrase sallallahu ‘alaihi wasallam,

meaning: “May Allah bless him and grant him peace”.

The letter [a] after the name of the Imams from the progeny

of the Prophet Muhammad[s], and for his daughter Fatimah[a]

stands for the Arabic phrase ‘alayhis-salaam, ‘alayhas-salaam (feminine) and ‘alayhimus-salaam (plural) meaning

respectively: (God’s) Peace be with him/ her/ them.

Interfaith52 The Mystery of the Holy Grail

The Holy Grail, whatever its elusive nature,

is of high spiritual interest to people of the

sister monotheistic faiths, says Frank Gelli

Health 56 Can HIV cells cure Cancer?

Experimental procedures on a six-year-old

leukaemia sufferer raise the question of

how far medical science should go to find

cures for acute illnesses?

58 Milk Teeth: Beyond a fairy tale

To have a healthy set of adult teeth we

should first look after our milk teeth, says

Laleh Lohrasbi

Places60 St Petersburg; A Northern Jewel

Mohammad Reza Amirinia travels to

St Petersburg and finds a city that has

embraced the present but also retained its

historical splendour

What & Where66 Listings and Events

Friday Nights Thought Forum - Islamic Centre of England

The Muslim DNA - A two day personal development

course – AlKauthar Institute

Islamic Soundscapes in China; Conference – SOAS

Love Muhammad; The Prophet of Mercy - World Forum

Proximity

Islamic Civilisation and the Islamic Tradition; past and

present (Edinburgh University)

The Special Tribunal for Lebanon: A Critical Perspective

– LSE

Qalam: the art of beautiful writing - Birmingham Muse-

ums and Art Gallery

Child Abuse and Neglect - The Muslim Institute

Agency and Gender in Gaza….. – LSE

Documentary film and discussion - Birmingham Museums

and Art

6th Annual Winter Walk for Gaza (London & Manches-

ter) - Muslim Hands

‘Can Muslims Escape Misogyny?’ Conference - The Deen

Institute

The Arab Uprising: results and prospects - LSE

Writing Competition - The Young Muslim Writers Awards

Spiritual Mysteries and Ethical Secrets - Islamic Centre

of England

5

In 1964 Mandela was arrested by the South African police and impris-oned on Robben Island. He was the 466th prisoner to arrive that year.

His prison number 46664 was in fact a combination of prisoner number and the year of his arrival. In this issue of islam today our designer has chosen to put together two elements to tell a concise story: The Hand and the Number.

The hand at the centre of the cover is Mandela’s own handprint, which is his own artwork known as the ‘Hand of Africa’. The African continent at the centre is said to have appeared by accident, but is nevertheless highly significant. The number 46664 has been overlaid with the flags of those influential countries which were either associated with the foundation of the apartheid state or supportive of it till the end, especially Great Britain and the United States of America.

Mandela’s incarceration lasted almost three decades. Eighteen of these years were spent in a small concrete cell where he slept on a straw mat. He was abused and tortured by the guards. His eyesight was damaged by the long hours he was forced to toil in the prison quarry in the searing sunlight. His jailer did not permit him to attend his mother’s funeral, nor that of his son when he died some time later. Not many

would have been able to withstand this kind of maltreatment.

Even though Reagan and Thatcher sided with the apartheid regime and ignored his calls for change, Mandela forgave and later met them. Mandela was no prophet and yet people believed in him wholeheartedly, especially the downtrodden masses who yearned to be delivered from years of suffering and marginalisation.

Prophetic characteristics can be present in all human beings. In the case of Mandela his capacity for forgiveness stood out. Upon his release he sought to move South Africa on from its diabolical past, reconciling oppressor and oppressed in a new, racially equal “rainbow” nation.

As Muslims we are not strangers to the narrative of forgiveness. Our great Prophet Muhammad(s) - whose birthday we commemorate this month - amazed everyone when he returned triumphant to his native Makkah after many years of persecution, opposition and military attacks. His Makkan tormentors would have expected a severe retribution from him but instead they received the promise of forgiveness and a general pardon.

Prophets are our examples for how to live and use our resources to benefit the whole of humanity. They

are strong and unbending individuals with an overwhelming ability to love. They aim to unify instead of exacting revenge and seek dialogue over diktat. They endeavour to win the hearts and minds of people, not just their compli-ance. Their divine mandate is what makes them special but from time to time their qualities are manifested in ordinary people. They have taught us that although inferior in worldly power and means, the righteousness of one’s cause allied to an unyielding resolve can positively change the world. If we respect Mandela today it is because we have seen in him the reflection of a character familiar to us, someone we love with all our heart, our beloved Prophet Muhammad(s). Whenever we recognise his qualities in others we will always be drawn towards them.

True leaders have the ability to trans-late vision into reality and ultimately they empower their people. Mandela was a man, a lawyer, a visionary leader but not a saint. He was a great figure in history, not above it and we salute him as a dear friend. •

‘Prisoner 46664’

EditorFrom the

6

Police force approves hijab for female cops Police in the Canadian city of Edmonton have approved a design for a headscarf for Muslim female officers.

The hijab design covers the head and neck, but not the face, according to a press release issued by Edmonton Police Services (EPS).

EPS currently does not have any applicants requesting to wear a hijab but police wanted to be proactive and ‘reflect the changing diversity in the community, and to facilitate the growing interest in policing careers from Edmonton’s Muslim community,’ it said.

‘Regardless of race, culture, religion, or sexual orientation, it is important that anyone who has a calling to serve and protect Edmontonians, and passes the rigorous recruitment and police training standards, feels welcome and included in the EPS,’ said spokesman Kevin Galvin.

Police said the changes to the tradi-tional garment have been supported by members of Edmonton’s Muslim community.

OIC report shows Islamophobia on the rise in the WestThe Organisation of Islamic Coopera-tion’s annual Islamophobia report has criticised what it calls a ‘culture of intolerance of Islam and Muslims’ in the West.

The OIC report is comprised of five main chapters and several annexes aimed at documenting ‘incidents of slandering and demeaning Muslims and their sacred symbols including attacks on mosques, verbal abuse and physical attacks against adherents of Islam, mainly due to their cultural traits.’

The report points to ‘the institution-alisation of Islamophobia’ in Western countries saying: ‘… the film, “Inno-cence of Muslims”, the publication and reprints of provocative materials by several European newspapers including the most recent one entitled “Tyranny of Silence”, the infamous “Burn A Qur’an Day” move by a Florida Pastor, the Congressional hearings by the Chairman of the US House of Representatives Committee on Home-land Security on the “radicalisation of American Muslims” in Washington DC on March 11, 2011, together with the anti-Muslim rhetoric by some right-wing conservative politicians and new emerging Islamophobes, have contrib-uted enormously to snowballing Islamo-phobia and manipulating the mind set of ordinary Western people to develop a

“phobia” of Islam and Muslims.’

According to the OIC report, the ‘perpetuation of Islamophobia…has become increasingly widespread, which, in turn, has caused an increase in the actual number of hate crimes committed against Muslims. These crimes range from the usual verbal abuse and discrimination, particularly in the fields of education and employment, to other acts of violence and vandalism, including physical assaults, attacks on Islamic centres and the desecration of mosques and cemeteries.’

The OIC report suggests that freedom of expression is used as a pretext to allow attacks on Islam. In this manner, protection is given to ‘the perpetrators of Islamophobia, who seek to propagate irrational fear and intolerance of Islam, [who] have time and again aroused unwarranted tension, suspicion and unrest in societies by slandering the Islamic faith through gross distor-tions and misrepresentations and by encroaching on, and denigrating, the religious sentiments of Muslims.’

OIC tells Myanmar to respect Muslims’ rightsAt the end of a three-day tour, the Organisation of the Islamic Confer-ence (OIC) has told Buddhist-majority

A m

odel

wea

ring

the

EP

S U

nifo

rm w

ith h

ijab

head

scar

f opt

ion

News

CANADA GUINEA

MYANMAR

7

Myanmar to repeal ‘laws restricting fundamental freedoms’ after more than 240 Muslims were killed by Buddhist mobs during 2013.

Before the OIC delegates left Myanmar, they visited minority ethnic Rohingya Muslims who fled the violence and are now living in squalid conditions in camps along the border with Bangla-desh in Myanmar’s Arakan state, also known as Rakhine.

Headed by Secretary General Ekme-leddin Ihsanoglu, the OIC delegation called on the government to continue legal reforms.

According to press reports, the Myanmar government responded by saying it would help ‘put an end to all acts of violence, protect the civilian population from violence and ensure full respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, including in Rakhine State.’

Myanmar has refused to grant citizen-ship to 800,000 Rohingya and told them to ‘return’ to Muslim-majority Bangla-desh even though many Rohingya have lived on the Myanmar side of the border for generations.

About 3,000 Buddhists led by robed

monks marched through Sittwe, capital of Arakan state, to protest against the OIC’s involvement in the Southeast Asian nation’s ethnic problems.

The protesters also converged on Sittwe’s airport to voice their anger when the OIC delegates’ plane arrived, before the officials transferred to heli-

copters to reach the Rohingyas’ isolated camps.

About 5,000 of the 240,000 Rohingya who fled their homes because of the clashes welcomed the OIC when the delegates visited camps for internally displaced people near Sittwe.

The 57 nations that comprise the OIC make it the world’s largest international Islamic organisation. The OIC describes itself as ‘the collective voice of the Muslim world.’ It has a permanent delegation at the United Nations.

Muslims Worldwide pay tribute to Nelson Mandela

Palestine

Palestinian leaders heaped praise on Nelson Mandela after the death of the revolutionary South African leader. Palestinian Authority president Mahmoud Abbas said:

‘The Palestinian people will never forget his historic statement that the South African revolution will not have achieved its goals as long as the Pales-tinians are not free.’

Hamas called Mandela one of the biggest supporters of the Palestinian cause. Today a great freedom fighter, Nelson Mandela has died, one of the world’s most important symbols of freedom,’ said senior Hamas official Moussa Abu Marzouk.

Iran

Iran’s president Hassan Rouhani tweeted: ‘With a heavy heart, we say goodbye to Nelson Mandela. Surely, his legacy will remain a source of inspira-tion and courage for all people.’

Ali Akbar Velayati, Iran’s former foreign minister, praised Mandela for playing a pivotal role in the fight against racism. Velayati said the Islamic Republic of Iran was the first country Mandela visited before he took office in 1994.

Former Iranian Presidents Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani also paid tribute to Mandela. Rafsanjani said that South African anti-apartheid revolutionary figure had told him that ‘Iran was the ideal destination for South Africans as the Islamic Republic had also experi-enced many difficulties over its resist-ance to repression and dictatorship.’

USA

The Council on American-Islamic Rela-tions (CAIR), the largest Muslim civil rights and advocacy organisation in the United States, said in a statement that

MANDELA TRIBUTES

8

his death was a loss for all humanity and that the South African leader will remain an example to those fighting for human rights.

The statement said: ‘throughout his life, Nelson Mandela served as an example of strength in adversity to all those fighting for freedom and justice. His legacy of uncompromising perseverance in the face of bigotry and injustice will live on for generations to come. He was a unique historic figure. From his jail cell, he demonstrated vision and courage, and taught the world the true meaning of steadfastness. Outside his cell, he demonstrated statesmanship, reconciliation and pragmatism. As the Prophet Muhammad(s) said: “For every day on which the sun rises, there is a (reward) for the one who establishes justice among people.” ’

Muslim Separatists on verge of peace deal with ManilaMuslim separatists in the Philippines have moved a step closer to a landmark peace deal with Manila that will give them autonomy, but there remain significant obstacles to an end to violence.

The two sides have reached agreement on sharing power in Muslim-dominated parts of the southern Philippines and hope to reach a final deal in the coming weeks.

‘We are in the home stretch,’ said Amado M Mendoza Jr, a political science professor at the University of the Philippines who is monitoring the negotiations.

The deal seeks to bring peace to the southern Philippines which has been racked by violence for more than a century. Many Muslims in the region believe that the Christian-dominated government in the north has oppressed them and taken their resources.

Muslim separatist groups, fuelled by such sentiments and by grinding poverty in the country’s south, have been fighting for an independent state for decades. The conflict has killed tens of thousands of people and has caused the resource-rich southern Philippine island of Mindanao to lag behind the rest of the country in economic and social development.

In October 2012, the Philippine govern-ment signed a framework peace agree-ment with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, the country’s largest Muslim insurgent group. That was followed in July by a wealth-sharing deal in which the two parties agreed that 75 percent of the tax revenue from metallic minerals mined in the region would stay

in Mindanao. In addition, 50 percent of the taxes collected from fossil fuels developed in the region would remain.

The details of the power-sharing agreement have not been released, but government officials indicated that the national government would retain authority over national defence, foreign policy and monetary issues. The newly formed autonomous region, to be called Bangsamoro, is expected to have broad local powers.

The announcement noted that the two sides were still negotiating an agree-ment on what was termed ‘Bangsamoro waters.’ ‘This is probably a reference to the control of coastal resources in the autonomous region,’ Mr Mendoza said. The Philippine Department of Energy has identified untapped oil and gas reserves in the Sulu Sea, along the coast of the Bangsamoro area.

Another aspect of the agreement to be negotiated involves what the two parties call the ‘normalisation’ of armed fighters in the insurgent group. This would involve incorporating the fighters into the Philippine military, the local police or other government security forces.

The most sensitive aspect of the next round of negotiations is likely to be the disarmament of the fighters who do not join the government military or security forces. The government forged a peace deal in the 1990s with another separa-tist group, the Moro National Liberation Front, but many fighters retained their weapons, and violence continued.

Hajj app intends to help pilgrims The Hajj can be a gruelling journey, full of physical and mental demands. With three million pilgrims packed into Makkah, it’s easy for things to go wrong. A UAE - based company has recently released the HajjSalam app to help pilgrims perform their religious duties.

‘Our goal is to help Muslims focus on the spiritual aspects of Hajj by relieving

News

UAE

PHILIPPINES

9

some of the pressure of the process and logistical challenges that cause so many issues,’ said Ali Dabaja, founder and CEO.

The HajjSalam app, which works in real time and recognises the user’s location, prompts pilgrims with the prayers and rituals they are supposed to perform at any given moment. There’s even a counter for the ‘tawaf,’ a ritual where pilgrims are supposed to circumam-bulate the Kaaba - the holy sanctuary that was built by Abraham and his son Ishmael - seven times.

Released last year by Mobily, a Saudi Arabian mobile phone company, the Hajj AR App has a camera that guides pilgrims to where they need to be. Other apps include mapping technology, and a Hajj journal that can integrate with social media platforms so pilgrims can tweet or post Facebook updates. There are at least 15-20 free Hajj apps

Dozens of women take part in the Inter Faith netball tournamentA netball tournament was organised by Tameena Hussain, 24, of Aldebury Road and Sergeant Helen Kenny from Thames Valley Police

Taking place for the second year at Cox Green Leisure Centre in Highfield Lane, women were encouraged to come down and take part for free.

Tameena said: “This helps to bring about better understanding and cohe-sion within our diverse communities.

“It’s for them to take part and build those relationships.

“It’s not about being competitive, it’s about having fun and making new friends”.

Sgt Kenny added: “I think it is important to strengthen the relationship between women and the police so that people are confident to come to us with issues

that we can resolve.

“Sport is a great way to break down barriers and build trust”.

Inter Faith Week ran all last week across England, Northern Ireland and Wales to highlight work done by inter-faith groups, celebrate diversity and encourage interaction between people from different backgrounds.

Safeway Apologises to Muslim WorkerSafeway, the second largest superstore chain in North America, has given a job back to a Muslim woman who was told she couldn’t wear her Islamic headscarf while at work at its El Dorado Hills, California., service station.

Rosemary Hassan was originally told by a manager she could wear the scarf, but an assistant manager didn’t get the memo, and told Hassan to remove the scarf or quit. Hassan quit.

But after learning of the incident, Safeway managers said the company’s policies allow headscarves, and offered Hassan her job back.

‘I felt my beliefs are stronger than a job, even though it was a really good job,’ Hassan said.

But now, Safeway said it was all a misun-derstanding. The company does have a dress code, but said, ‘the company does adjust these standards where needed to accommodate religious needs of employees.’ Safeway said she can have her job back and wear hijab.

Hassan said she’d like to put this all behind her and return to work, as long as she’s able to wear her hijab.

Pope urges coexistence, says Qur’an does not condone violence Pope Francis has issued his first Apos-tolic Exhortation (Evangelii Gaudium), translated into English as The Joy of the Gospel. In the 224-page document, the Pope has contrasted ‘violent fundamen-talism’ with ‘authentic Islam.’

The latter, he wrote, was ‘opposed to every form of violence.’

Attacks on Christian communities in the Middle East have left in their wake hundreds of victims and played havoc with Christian communities that have coexisted with Muslims for over 14 centuries.

While urging Christians to ‘avoid hateful generalisations’ about Islam, the Pope also called ‘humbly’ on Islamic countries to guarantee full religious freedom to Christians.

The Pope concluded the discussion by asserting that ‘authentic Islam and the proper reading of the Qur’an are opposed to every form of violence.’

Pope Francis I

VATICAN

UK

US

10

Following our previous articles on aspects of Islamic finance and the interest generated by the 9th World Islamic Economic Forum held in London, we have been requested by our readers to discuss in more detail how shari’ah compliant financial transactions work. Here Hamid Waqar presents an in-depth explanation of the ins and outs of one of the most popular contracts; sukuk

SUKUKA Progressionof Islamic Finance

11

12

Islam is a religion that teaches man to excel in all dimensions of life. It teaches man how to deal with any situation in such a way that

he can secure divine satisfaction. One important aspect of life is his financial dealings. Islam has not been silent in this aspect - rather many principles have been provided allowing one to derive financial recommendations and prohibitions from them.

There are plenty of rules pertaining to trade, partnership, banking, investment, and loans. There are also areas of finan-cial transactions which are prohibited, for instance interest (riba) and anything to do with sinful products, such as wine and alcohol. The main areas which constitute a prohibited and invalid financial transaction from the Islamic point of view are: speculation (maysir), unjust enrichment or unfair exploita-tion, interest, and uncertainty (gharrar).

A sukuk is an Islamic finan-cial investment scheme and some forms of it have been approved by the shari’ah. The official definition provided by the Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) is that sukuk certifi-cates are: “certificates of equal value representing undivided shares in the ownership of tangible assets, usufructs and services or (in the ownership of) the assets of particular projects or special investment activity.” The sukuk is an actual certificate which proves the ownership of interest in the tangible asset giving the possessor interest in that asset in proportion to his investment.

The sukuk product was developed to address the shortage of Islamic financial schemes which serve as long-term investments and which can be traded on the secondary market. There were reasons that such schemes were rare, such as practicality and shari’ah compliance. The practical aspect was that there was not an existing secondary market where one could trade invest-ments. The sukuk solved this problem because it constitutes real ownership of

a tangible asset allowing the investor to easily trade it. The sukuk product has grown immensely ever since the first sovereign sukuk bond was issued by the Central Bank of Bahrain in 2001.

The most important characteristics of the sukuk product, which are in direct contrast to its conventional cousin, the interest bond, are: First, the sukuk certificate points to a form of joint ownership of the profits of the business project or physical assets. This is why they must be organised in connection with a familiar Islamic partnership contract. The contracts can have condi-tions placed upon them in accordance with the well-known prophetic tradition: “Believers are upon their conditions.”

The second characteristic of Islamic sukuk revolves around the method of distributing profits. The method by which they are distributed is dependent

upon the type of contract that was issued. These fall into three main categories.

The first group is based on the purchase and sale of the loan. It is comprised of the sukuk al-istisna’ and sukuk al-murabaha and is the closest to the conventional interest bond. In this sukuk, the owner receives speci-fied profits over a specified period of time. There are differences of opinion regarding the permissibility of these sukuk. The majority of Shia scholars allow the sale of loans to third parties while the majority of Sunni scholars and a minority of Shia scholars, including Ayatollah Khomeini, consider it to be an instance of interest. An example of this would be if a government decides to develop a highway, but instead of paying the contractors in cash, they

issue sukuk al-istisna’ certificates which the contractor can sell on the secondary market. The contractor then sells the certificates for a specified price and the buyer knows that after a certain amount of time he will receive a percentage of any profits.

The second group is based on the purchase and sale of physical assets. The most prominent sukuk in this category is the sukuk al-ijara, especially with the condition of ownership after the lease agreement is finalised. When the owner of the sukuk certificate sells it to a third party in the secondary market what he is actually doing is selling his portion of the physical asset to the future owner. Islamic scholars are unanimous in condoning this type of contract.

The third group is based on a partner-ship in the profits of an economic

venture. In this sukuk, the owner of the sukuk certificate becomes an investment partner for an economic project. He is given a portion of the profits of the said project in relation to the amount of his certificate. For instance, let us imagine purchasing a sukuk for the building of a metro line. The more progress that is made on the project the more

valuable the sukuk certificates become and when the project finishes the value of the completed project is distributed amongst the owners of the sukuk certificates. Thus, the potential profits of these sukuk certificates are based on predictions that do not necessarily actualise. There is always the risk of a loss.

The third defining feature of the Islamic sukuk is based on securing the principal investment. The difficulty in promising the return of the principal investment from an Islamic perspective is that it takes risk out of the equation. This would seem to be in contradiction to the tradition: “The one who gains [potential] profit [can] incur [potential] loss.” According to this tradition, and the principles of Islamic finance, the investor must have a certain amount

A sukuk is an Islamic financial investment scheme and some forms of it have been

approved by the shari’ah

13

of risk in his investment. Hence, if the issuer of the sukuk goes bankrupt he would not be able to return the prin-cipal investment of the owners of the sukuk contracts.

Therefore, if the issuer of the sukuk does not promise a return of the prin-cipal investment then it is completely in congruence with the shari’ah. The question remains, what if the return of the principal investment is promised in the form of a condition of the sukuk contract? The answer to this question depends on which of the three above mentioned categories the sukuk falls under:

Promising the return of the principal investment based on the purchase and sale of a loan

In this group, the financial institution which offers the sukuk al-murabaha takes on the position of the repre-sentative of the owners of the sukuk certificates and uses their investments to purchase an asset outright and then sell that asset in the form of a long-term sale on credit (bay al-nasiyah). Then, the purchaser of the asset will pay the amount of the principal coupled with the specified profit to the representative of the investors. One example of this might be that the issuer of the sukuk certificate, as the representative of the owner of the certificate, purchases a housing development and then sells it to a third party for a profit with payment made over an extended period of time.

When this sukuk is sold in the secondary market the principal invest-ment and specified profits transfer ownership as well. In this case, if one accepts the purchase and sale of loans in the secondary market the security of the principal investment and specified profits will become an essential part of the sale on credit. But, if one does not accept this sale, as some prominent Shia scholars and the majority of Sunni scholars do not, then selling the sukuk contracts on the secondary market would be problematic. Therefore, in order for it to remain lawful, some scholars only allow the owner of the certificates, as in the housing develop-

ment example, to retain them until expiry, while others allow for sale on the secondary market for profit or loss.

Promising a return of the principal investment based on the purchase and sale of physical assets

The financial institution of this group, representing the owners of the sukuk certificates, purchase and then lease a physical asset. They collect lease payments and issue them to the owners of the sukuk certificates. At the end of the rental period they either transfer ownership of the leased property to the renter (if the contract was a lease with the condition of ownership) or it is returned and sold in the market (if the contract was a normal lease agreement).

Promising the return of the principal investment based on a partnership

The financial institution which issues the sukuk certificates collects the investments of the owners of the certificates and then uses them in the construction of industrial, agricultural, or commercial projects in a partnership contract with other parties.

The popular Islamic opinion is that one partner cannot stipulate a promise of recovering the principal investment from another partner as a condition of the partnership contract. This obvi-ously leaves open the potential risk of financial loss incurred from issues such as negligence or poor performance. A number of contemporary scholars have attempted to mitigate this risk of loss by permitting the condition of compensation for possible loss by one of the parties in the contract. This usually means that the culpable partner will compensate the investor for any loss on his investment. •

Hamid Waqar is an American Islamic scholar, graduated from Islamic seminaries.

12

9

11

5

9 3

2

7

1Me Time

14

12

9

11

5

9 3

2

7

1Me Time

15

Batool Haydar believes that in our hectic world the best ‘me time’ is that which is spent trying to connect with

the Creator

12

9

11

5

9 3

2

7

1Me Time

16

In many ways, we live a life filled with purpose. We have ambitions, careers, friends, family and commu-nity to occupy us. We often wonder

at how fast a week has passed by or that a weekend is over before it even begins. Our ‘To Do’ lists grow by the day, increasing in number before we’ve managed to cross out existing tasks.

Given the quantity of work we manage to go through and the achievements we gather along the way, one would imagine that we manage to get every-thing we want done and live lives that are fulfilled, if some-what frantic. However, surveys show that a large percentage of people - especially women - are unhappy with the quality of their life despite being otherwise successful.

In secular society, there has been a growing emphasis on finding and respecting ‘me time’ i.e. taking some time off on a regular basis to allocate to yourself. The suggestion is to use this time for hobbies or meditation or even just to sit quietly and not think about the next task or chore that awaits you.

Allison Cohen, a family therapist living in Los Angeles says, “We’re a multi-tasking society. If we’re having a conver-sation with a friend, we’re thinking about the other things we have to get done. Instead, you need to be present in the moment. Whatever you’re doing for you, don’t be thinking about your grocery list or the PowerPoint presenta-tion. There’s a lot of time in our day that we could be enjoying, but we lose it because we’re focused on what we have to do next.”

When we begin to become more aware, then the pockets of quality time we gain do help us to relax and reenergise, but this isn’t always enough. We may be left temporarily rested and ready to

jump back into the whirlwind of activity, but we still carry around a deeper thirst for something to fulfil us in a more permanent way. This is why we need the breaks of ‘me time’ regularly to refuel us, because the process of being drained is a continuous one.

Within Islam, the concept of ‘me time’ takes on a unique form, that if imple-mented properly, can actually sustain our energy longer and give us a more dynamic quality of life. The basic premise of faith is to know and be aware that God is present with us at all times; that every time we seek to be alone and away from the distractions surrounding us, we are actually presented with an opportunity to be more aware of His Presence. The easiest way to start is by using the time we already have allocated daily for communion with God.

For most of us, daily prayers are an obli-gation and the relief that we feel comes after we have performed them, almost as if we have shifted a burden from our shoulders. True relief is to be found in the act of prayer itself as the Prophet Muhammad(s) used to tell Bilal when asking him to recite the adhan (call to prayer): “O Bilal, give us rest with it.” In the Qur’an, God Himself assures us that “…Verily! The hearts find rest in God’s remembrance!” (13:28)

If we realise the magnitude and value of such moments, we will appreciate every chance we get to indulge in them.

Prayer will then become the time we use to turn back to our real roots and to connect with the Creator. The harmony achieved through such a process is something that will resonate with His creation in our daily routines.

Building upon this foundation, we can then find an infinite amount of ‘me time’ as we learn to become more aware of the presence and support of God in every moment of our existence. This awareness in turn will allow us to fully appreciate that there is no independent ‘me’ within us that can be complete or

at peace without Him.

Although it may sound compli-cated, finding time to be with yourself and God only requires determination and whatever time you have to spare when-ever you have it. Here are some ways in which to start re-focusing your perspective.

Focus in Five Minutes

If you have only five minutes or so to spare, start by adding anyone or as many as you can of the following to your daily routine.

y Pause for a few seconds before you perform your wudhu (ablution) for prayer and think about the purpose and importance of the meeting ahead of you.

y Try reciting adhan and iqama (the call to prayer) before you begin praying and concentrate on the words and how they are meant to prepare you for the main prayer.

y After and between prayers, take time to recite some tasbih or dhikr (invoca-tion) with understanding and make a regular habit of this.

y Take time from your schedule to pause, breathe deeply and slowly and simply remember that God is present with you and simply a thought away.

y Save some du’a (supplication) or recitations on your mp3 player or iPod and take a few minutes to listen to them when things get especially busy.

“Certainly We have created man and We know to what his soul tempts him, and We are nearer to

him than his jugular vein.” (Qur’an 50:16)

[...] remember that anything you do is aimed at spending quality time with your own self and nurturing the essential

relationship your soul has with God.

12

9

11

5

9 3

2

7

1Me Time

17

Thrive in Thirty Minutes

When you have more time at hand, try and allocate half an hour to some of the following activities:

y Make a list of books on Islamic topics of interest or on areas of religion that you feel you need to learn more about and then start reading them, one chapter at a time.

y If you have a park nearby, go for a brisk walk. The fresh air will clear your head and as you walk, if you observe the people around you, you will begin to understand many things about human behaviour. Sometimes, we forget to appreciate how much better we have it than so many others.

Soul-search in sixty minutes

On weekends or days off, try to socialise:

y Pick a speaker you like and listen to their talks. Take notes, listen again and if you can, join - or create - a study circle where you can discuss what you have heard.

y Find a class online or at a community centre that you can join. It could be Islamic-oriented or more hobby-based, but remember to find a connection to God through it regardless.

y Volunteer. Sometimes the best place to find the Creator is amongst His Creation. Meet people, help them, be a little selfless and in the process seek to understand and connect with the Love and Mercy of God.

y Spend time reciting the Qur’an slowly and calmly. We often neglect reciting the book that is the essence and foundation of our faith. Just reciting it in Arabic will soothe your soul, and when you add the element of under-standing, you will discover new depths every time you open it.

Through all of this, remember that anything you do is aimed at spending quality time with your own self and nurturing the essential relationship your soul has with God. Don’t allow these precious efforts to become part of another routine or chore. Imam Ali(a)

says: “…be lenient to (your soul), and do not force it. Engage it (in worship-ping) when it is free…”

Based on this, try either the suggested activities or different ones and if at first one doesn’t work for you, simply shift to another until you slowly develop the inclination towards them. The aim is to discover things that you will lean towards and look forward to eagerly so that it truly becomes about finding the best in yourself, God-Willing! •

18

For subscriptions by post, send a cheque payable to the Islamic Centre of EnglandWrite ‘islam today magazine’ on the back.

Please note that the above fees are for the UK only and include postage.For subscriptions outside the UK please write to: [email protected]

Subscribe online:http://www/islam-today.net/subscribe.asp

or at

DIGITAL EDITION

6 months £10.00

12 months £18.00

PAPER EDITION

6 months £25.00

12 months £48.00

19

20

Masterpiece ‘30 Days of Running in the Space’- Ahmed Basiony 1978-2011

“O Father, O Mother, O Youth, O Stu-dent, O Citizen, O senior. You know this is the last chance for our dignity, the last chance to change the regime that has lasted the past 30 years. Go down to the streets and revolt, bring your food, your clothes, your water, masks and tissues and a vinegar bot-tle. And believe me, there is but one small step left. They want war, we want peace, and I will practice proper restraint until the end, to regain my country’s dignity.”

Ahmed Basiony’s final Facebook status 26 January 2011

Ahmed Basiony was born in 1978 in Cairo. He was an artist and activist.

His work played a crucial role in fusing the message of art and revolution. Basiony is considered one of the most important figures in contemporary Egyptian art. Known initially for his large-scale expressionistic paintings, his art was varied, beginning with more traditional artistic interpretation, and developing along unconventional lines.

He won first prize in painting in the 2001 Salon of Youth for his earlier, more classical work. But his develop-ment as an artist was intense and often radical, with his later work being more experimental. Initially involving new media and multimedia installations, Basionys work continued to evolve toward digital sound and performance art. His development and learning were often supervised by the artist Dr. Shady El Noshokaty, who would later curate Basiony’s final work.

In ‘30 Days of Running in the Space (2010)’, Basiony put on a solo perfor-mance for one hour per day for thirty days. This entailed wearing a plastic suit that covered his entire body and running on the spot. Digital sensors were used to calculate the amount of sweat he produced in relation to the number of steps he took. The data, displayed on a large screen, reflected the physiological changes of his body in motion: the energy being transferred, calories being consumed, and the waste emitted through sweat.

Through the use of a graphic grid and geometrical coloured shapes, Basiony conveyed how energy is transformed. He attempted to show how we as humans are being consumed by time, and also

provoke reflection on the notion that vain actions lead to nothing, and how, often by just living or existing, we are running but not going anywhere. This led me to consider how pivotal inten-tion is in relation to action, and how necessary it is to incorporate progres-sive movement into one’s life. Our lives should be a dynamic movement that enables us to be truly alive and make inroads into self-discovery as opposed to just mounting the hamster wheel for the umpteenth time in order to satisfy our basic needs. By running in one place and getting nowhere, Basiony is asking us to question our place in the world. Where are we going? Why are we here?

Through this piece of performance art, Basiony was able to raise ideas about being and responsibility and awaken them in the public consciousness. But

as history now documents, Basiony was shot and killed by police on 28 January 2011 during the first week of the Egyp-tian uprising. What makes his work a masterpiece for me is how his message continued posthumously.

Basiony died protesting against the regime and simultaneously filming the peaceful crowds that had gathered in Tahrir Square. He captured images of violent responses by the police and compiled them against footage of hundreds of protesters praying their salat [compulsory prayer] together in the square.

Basiony’s friend Shady El Noshokat, having accessed Basiony’s computer after his death, noticed that there were images of the uprising juxtaposed

ARTS Art Editor Moriam Grillo

21

against Basiony’s 2010 performance. El Noshokat immediately recognised what Basiony’s intentions would have been, had he lived to express them.

The unedited partnering of images from ‘30 Days of Running in the Space (2010)’ and protest footage of Basiony’s experi-ence in Tahrir Square were combined to create a video installation. This instal-lation occupied two series of five large screens which play two twelve-minute films in staggered succession. The images force the viewer to engage with one reality or the other as the screens are placed in such a position that both could not be observed simultaneously.

‘30 Days of Running in the Space’ (2011) is two things: a performance piece in which Basiony explores ideas of consumption alongside footage he captured moments before his demise. But what do these two pieces have in common apart from the artist who conceived them?

I believe that by playing both alongside one another, Basiony is able to further develop his message, which like the fluid situation in Egypt at the time developed rapidly. With his performance installa-tion a year before the uprising, Basiony made a statement about how the action of just one person has the ability to be transformative. Basiony extended this statement to represent the actions of many people, all standing together in one place with the shared intention of transforming a regime that had been in place for thirty years. A masterpiece indeed.

Ahmed Basiony represented Egypt at the Venice Biennale. The exhibition for the Egyptian Pavilion was conceived by Shady El Noshokat and curated by Aida Eltorie.

In the spotlight Nermine Hammam

Nermine Hammam’s work is inspired by the early days of the Egyptian revolu-tion and her encounters with soldiers in Tahrir Square. The image featured is part of a group of photomontages combining photographs of army troops with images of colour-saturated idyllic landscapes. Her works are intricate composites of layered images, which use a distinctive style to combine digital manipulation and painting. Using an array of colours Hammam presents photographs which appear larger than life. Her composition adds to the endeavour, by placing her subjects in ways which suggest compromise.

Hammam said that her series, Uppekha, examines war and the notions of power that reside within it. Her intention is to convey humanness and vulnerability by reclaiming the soldier’s individual identity. “My work is an exploration of the frailty that crouches behind stereo-types of force, masquerading within the military, which seeks to reveal the

vulnerability of youth parading behind the weaponry and masculinity, whilst questioning the reality of power and its construction.”

She is one of many Arab artists whose work has been celebrated because of the uprisings, and the world’s fascination with Arab culture which arose from it. ‘Unfolding’ is a series of stylised vintage Japanese landscapes, juxtaposed with explicit footage of police brutality which occurred after the revolution. In Unfolding, the artist uses the art of camouflage to diffuse violent imagery. By hiding injured behind some foliage, Hammam creates a form of propaganda which nulli-fies the fear factor of authority. She implores the viewer to look closer, and re-examine what they can see in order to realise the full magnitude of what is conveyed. Hammam developed the idea for this series from her own experience of watching a young protester die in Tahrir Square, while, a short distance away, city life continued oblivious to the tragedy.

Hammam lives and works in Cairo.

22

PhotographyKhalil Nemmaoui, Morocco

Khalil Nemmaoui was born in Morocco in 1967. His first photographic images were published in 1993, and his first exhibition followed in 1997. A series of his photographs were nominated for the Prix Pictet 2010 and won the prize of The Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie at the 2011 Rencontres de Bamako.

The moment I laid eyes on this photo-graph, I was completely enthralled by its simplicity and splendour.

Khalil Nemmaoui has a well-established career in photography and the compo-sition of these images does much to express his visual prowess.

Having worked as a photojournalist since the early nineties, Nemmaoui first focused on portraiture, after taking up photography as an art form, before

returning to landscape.

Nemmaoui has a keen eye for detail and uses his vision to weave interesting stories out of ordinary things.

La maison de l’arbre comprises of a series of photographs which attempt to rework depictions of landscape. By presenting a man-made structure as integral to nature, Nemmaoui succeeds in preserving classical notions of

terrestrial art. He introduces a new way of perceiving the world through our ever-changing landscapes. Nemmaoui is fascinated by space and form. He invites us to involve ourselves in that same fascination, to look at things in a playful way, to change our perception by choosing carefully where he aims his camera.

Nemmaoui has managed to combine two diverse structures into one form.

What I like most about this photograph, apart from the fact that one’s eye is directed both vertically and horizontally, is the way the branches reaching toward the heavens are set against a glowing sky. It is as though a halo surrounds the tree in a way that leaves ordinarily would, reinforcing a whimsical notion that is reflected in the name of the series.

Khalil Nemmaoui lives and works in Casablanca and Paris.

The Place to BEThe Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar

Hajj: The Journey Through Art

Through January 2014

This exhibition, which is a collabora-tion with the British Museum, allows visitors to explore the Hajj pilgrimage. Incorporated within it is an outdoor photography display featuring the work of five international photographers.

It is also an opportunity to see a variety of artwork which has never before been on public display.

23

HeritageTurquoise Mountain Arts

Turquoise Mountain Arts is a non-profit, non-governmental organisation specialising in urban regeneration, business development, and education in traditional arts and architecture. It provides jobs, skills, and a renewed sense of national pride to Afghan women and men.

It was established in 2006 under the patronage of HRH The Prince of Wales and the President of Afghanistan, to revive traditional Afghan arts, crafts and architecture. The organisation founded an Institute of Traditional Afghan Arts and Architecture with four craft schools in calligraphy, miniature painting, woodwork, jewellery, and ceramics.

Ferozkoh [which translates as Turquoise Mountain] is an exhibition at Leighton House London which presents a selec-tion of works created specifically for the exhibition by the students and teachers of Turquoise Mountain’s Institute for Afghan Arts and Architecture in Kabul. Each item was inspired by an historical object in the Museum of Islamic Arts’ permanent collection.

The theme of the Ferozkoh exhibition is the preservation of Islamic art in the modern world, and the role of educa-tion in its transmission and translation.

The exhibition showcases four of the great empires of Afghanistan and their material culture. The Ghaznavids, Timurids, Mughals and Safavids. In Ferozkoh, you will see objects of antiq-uity from the MIA collection, twinned with modern objects created by the students and teachers at Turquoise Mountain in Afghanistan.

These works demonstrate how Afghan artisans have renewed their traditions through effort, wit, skill and imagina-tion. It reflects a deep sense of Afghan pride.

AddendumModerate Enlightenment, 2007- Gouache on wasli

Imran Qureshi (born 1972).

This miniature form of painting grew out of manuscript illumination and has a strong narrative quality to it. For Qureshi, there is an exquisite tension between the modernity of his sitters and the strict parameters of the ancient practice itself.

A selection of Imran Qureshi’s minia-ture work is on exhibition at Gallery 916 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Roof Garden Commission: Imran Qureshi’s Miniature Paintings

Through February 2, 2014. •

Moriam Grillo is an interna-tional artist. She holds Bach-elor degrees in Photography, Film and Ceramics. She is also a freelance broadcaster, photographer and writer.

24

25

Recently reopened after substantial refurbishment in 2010, Leighton House is one of London’s best-kept secrets.

Nestled in a wing of Holland Park, the house is surrounded by its own oasis of

greenery. There is nothing particularly noteworthy about the exterior, and after a walk through the park’s exotic menag-erie of peacocks, Leighton’s garden in this season amounts to little more than a large lawn. Enter the house and

after passing through the ticket and merchandise area (no glorified museum shop, just some tastefully arranged objects, postcards and books for sale) you arrive in the staircase hall. Here a stuffed peacock perches near a superb

Arab Hall - Leighton House

Leighton House Museum

Where east meets west

Cleo Cantone visits the former studio house of Lord Leighton. An Eastern-flavoured dwelling with Victorian eclecticism

26

wooden cabinet inlaid with mother of pearl and the walls are lined with a mixture of Victorian green glazed tiles and Turkish Iznik-style tiles: the perfect eclectic collection of a well-travelled Victorian gentleman.

Only Frederic Leighton was not just a traveller but a painter, sculptor and collector. Not only did he make a number of purchases on his travels, mostly to the Middle East, but what he could not obtain he would sketch and commission a trusted craftsman back in England to reproduce. Although associated with the Pre-Raphaelite school, Leighton’s increasingly frequent trips to North Africa and the Middle East brought a distinctively ‘Orientalist’ flavour to his paintings.

Not surprisingly, therefore, he instructed his architect, George Aitchison to include an Arab Hall which was added to the ground floor of his Kens-ington house between 1877 and 1879. There is nothing more incongruous than a traditional Arab courtyard complete with functioning fountain in the midst of an equally traditional British house, yet from a Muslim perspective, nothing could seem more natural. Then as you hear the comments of fellow visitors that the sound of the trickling fountain would drive them mad, it slowly sinks in that you are not somewhere in the Middle East but right in the heart of

London. Indeed, when you zoom in to the festive array of Islamic decoration, you realise that it is a pot-pourri of different epochs, styles, countries and traditions.

The layout of the hall is reminiscent of courtyards in Syria and Egypt with even the odd echo of Palermo’s Ziza (see Cantone “Sicily: Glory of the Ocean”, Islam Today, issue 11, September 2013: 60-65). Consisting of four pointed arch ivans - the one facing the entrance is windowless, the other two flanking arches have mashrabiyya covered open-ings while the arch facing the entrance features a niche - one could go as far as to say it is like a mihrab as it is the main focus of the hall. It contains tiles of miniature Persian figures dating from the 17th century known as kubachi.

The central dome is supported by four corner squinches simply painted in black and white bands reproducing the ablaq effect of alternating dark and light shades of marble typically used in Mamluk and later Ottoman

architecture. The dome’s gilded decora-tion which was lost in the 1940s due to damp has been restored complete with delicate Ottoman-style stencilled floral motifs.

Surrounding the drum are glass-stained windows allowing a subdued light to penetrate the hall. A brass ‘gazolier’ hangs from the dome: it is formed by a circular band from which sprout elec-tric bulbs which replaced the original gas lights in the 1890s. The design of the lamp was based on Leighton’s

own sketches of mosque lamps and executed by the architect of the house.

The walls of the hall are covered in Syrian and Turkish tiles displaying a variety of styles: from the floral Iznik type to the calligraphic band that underlies the second floor mashrabiyya. Inscribed

on the 42 calligraphic panels is a verse from the Qur’an’s first six ayahs of surah Ar-Rahman.

Virtually inconspicuous are the tiles produced by another famous Victorian ‘Orientalist’, William de Morgan, to replace the missing 17th century tiles collected by Leighton in the old city of Damascus from buildings that were allegedly being demolished when he visited the city in 1873.

Leighton employed a number of contacts, including the then British consul in Damascus, to procure items for his private collection of ‘oriental’ art.

The 19th century saw something of a boom for European collectors exporting vast quantities of Islamic artefacts back to their homelands where they would either remain in their private collections, sold off to the Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert) or exhibited at the Great Exhibitions held in European capitals to showcase

The walls of the hall are covered in Syrian and Turkish tiles displaying a variety of styles: from the floral Iznik type to the calligraphic band that underlies the second floor mashrabiyya. Inscribed on the 42 calligraphic panels is a verse from the Qur’an’s first six ayahs of surah Ar-Rahman.

Frederic Leighton (1830-1896)

27

the ‘inferior’ qualities of their colonial subjects.

With no expense spared for his Arab Hall, Leighton had the mosaics made from glass tesserae in Venice and shipped back to London. Their motifs feature peacocks, female-headed beasts similar to Al-Buraq, dragons, falcons and birds, snakes as well as signs from the Zodiac and curly vines.

In the drawing room hangs a collection of Spanish lusterware plates, called Hispano-Moresque due to their dual Christian-Spanish and Islamic heritage. These plates, reflecting the taste of the age for the ‘Moors’ of Spain together with the ‘Persians’, were credited for having introduced to Europe the type of pottery known in Italian as majolica. In the adjacent dining room, with its reproduced Victorian red wall paper, a collection of Turkish Iznik plates and other vessels adorns the walls and mantelpiece. This type of distinctive pottery stands out because of the appearance of the colour red.

Thought to have been developed on the island of Rhodes by Persian potters, this particular shade became the distin-guishing characteristic of Iznik ware (used in modern day Turkey).

The visitor is then led back to the stair-

case to gain access to the second floor and the silk room where Leighton’s own paintings hang next to those of both his contemporaries and famous Renais-sance artists like Rossellino, a pupil of Donatello’s, and Tintoretto. Before entering the proprietor’s studio, there is a low couch in the window bay screened by the mashrabiyya that overhangs the Arab Hall below. The oriental theme slightly dilutes in the studio but among the artist’s small figurative sculptures that he used as models for his paint-ings, there are also a couple of portraits of ‘oriental’ subjects he presumably painted on his travels: a Persian pedlar and a turbaned man.

At the end of this vast room, on one side of which is a raised platform with a grand piano, is a wooden gallery acces-sible by means of a concealed staircase. Through here is a space dedicated to temporary exhibitions. Currently on show is “Ferozkoh: Tradition and Conti-nuity in Afghan Art - A conversation between the Present and the Past”. This exhibition is the product of a collabora-tion between the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) in Qatar and the Turquoise

Mountain Institute for Afghan Arts and Architecture in Kabul. Artists from the latter institute were invited by MIA to study the objects of Islamic art in their collection and draw inspiration from them to produce new works. It is a unique opportunity to view the original artefact next to the new one. A short film records the Afghan artists’ thoughts and impressions about this collabora-tion and the skills they learned in the process. Some of the woodwork pieces are scattered throughout the museum: a bookcase in the drawing room, pendant

Jali balls in the Arab Hall and a carved Nuristani figure in the entrance by the staircase. In the coming winter months there will be a series of talks, concerts, readings and film screenings to accom-pany the exhibition.

Leighton’s legacy lives on in his house turned museum. What is interesting is that today the collectors are not only westerners - the pieces on show from Qatar eloquently illustrate this gentle shift eastwards, a sign of a kind of re-appropriation of a glorious past by

the Qatari elite. Leighton and his fellow Victorian collectors were perhaps unduly obsessed with an idealised Islamic past so the work carried out by the young Afghan artists today is vital not only to preserve the traditions of craftsmanship of one part of the Islamic world, but to give them new meaning, re-invent them even, and keep them alive in today’s rapidly changing world. •

Dr Cleo Cantone holds a PhD from the University of London. Her book “Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal”, based on her doctoral research, has recently been published by Brill.

[..] when you zoom in to the festive array of Islamic decoration, you realise that it is a pot-pourri of different epochs, styles,

countries and traditions.

28

Lila Abu-Lughod begins her book by recalling Time magazine’s cover of August 2010, showing a young Afghan

woman whose nose had been cut off as a punishment by her Taliban husband and his family. Underneath the picture ran the headline: “What Happens if We Leave Afghanistan?”– a message that implied women would be the first victims in the event that western forces withdrew from Afghanistan.

Abu-Lughod, who is an anthropologist, finds it difficult to reconcile her own first-hand knowledge about Muslim women with the view portrayed by the American media and believed by the majority that ‘Muslim women do not have rights’. With this book she aims to debunk that myth through recounting the experiences of Muslim women she knows, telling their stories, describing their lives, their aspirations and their struggles to create better lives. This is an attempt to add some nuance to the stereotype of Muslim women as a homog-

enous, undifferentiated block through demonstrating the complexities of their characters, their societies and their lives. Western representation of Muslim women, as Abu-Lughod points out, has a long history, going back to the first centuries of Islam, extending to the Middle Ages, through colonial times and beyond. She argues however that after the attacks of September 11, 2001 the image of oppressed Muslim women received a boost and became linked to a renewed sense of mission to rescue them. To support the so-called war on

Book review

Saving Muslim Women?

Are Muslim women really oppressed? Why is the West so keen to rescue them? Mohsen Biparva reviews Lila Abu-Lughod’s new book, Do Muslim Women Need Saving?

‘Because of our recent military gains in much of Afghanistan, women are no longer imprisoned in their homes.’ Laura Bush, 2001

29

terror and to give it moral justification, all sort of representations of Muslim women’s plight proliferated in the media.

The first issue that the author chooses to tackle is the veil, or rather the politics of the veil. With its different names and styles, the veil has become the most notable symbol of the oppression of Muslim women. It has become a popular belief in recent years that when women cover themselves, it must always be the result of coercion by, or capitulation to male pressure. To explain that veiling does not necessarily stand for lack of independent agency, Abu-Lughod has to explain the cultural meaning and the function of the veil in Muslim societies. She refers to western liberal commentators’ bafflement that Afghan

women did not throw off their burqas after the Taliban were removed in 2001, asking why this should be surprising. ‘Did we expect that once “free” from the extremist Taliban these women would go “back” to belly shirts and blue jeans or dust off their Chanel suits?’

In explaining often obvious things, she stresses the fact that the burqa was not invented by the Taliban. It was the local form of covering among the Pashtun and several other Afghan ethnic groups. Similar to many other forms of coverings, the burqa marks the symbolic separation of male and female domains, associating women with family and home rather than the public sphere. Referring to Hanna Papanek, an anthropologist who worked in Pakistan in the 1970s, she calls the burqa a ‘port-

able seclusion’ or in a more familiar expression a ‘mobile home’.

In this manner, the burqa is the exten-sion of home and family space that marks the responsibility and modesty of its wearer, and assures her protec-tion from the harassment of strangers in the public sphere. This is done by symbolically signalling to all that they are still in the sanctuary of their private space and remain under the protection of the family. It also has significance in showing someone’s social status - the blue burqa, for example, is usually worn by women from respectable and strong families. She shows that there are many different types of coverings in Islamic societies, all with their particular cultural meanings and social connota-tions. One of these is the modest

30

31

Islamic dress that has been adopted by Muslim women since the mid-1970s that apart from projecting modesty and piety can be seen as a sign of educated urban sophistication, or in her opinion, a sort of modernity. She argues that in some countries like Iran, women play with colour, tightness, or a wisp of hair to display political and class resistance.

Abu-Lughod challenges arguments made by some rescue-Muslim-women circles in the US who compare the struggle for gender equality with the anti-slavery movement. She believes for example that in the anti-slavery movement, activists would endeavour to change their own society, to convince their own governments to stop the trade in slaves, whereas in these gender-equality campaigns, it is all about persuading men in “other” places to end their violence against “their” women. By this, she believes, activists of this kind ignore or trivialise inequalities and violence against women in their own societies to make legitimate concern about sexual violence in places like Afghanistan. For example, statistics show that US maternal mortality rate is much higher than Italy’s, or that US prisons house a relatively higher proportion of women convicted of killing their abusive lovers or husbands.

The advocates of rescuing Muslim women according to Abu-Lughod, share several beliefs, foremost of which is a mythical place she calls “IslamLand”. IslamLand is a place where things are most wrong, most notably for Muslim women, and they are wrong because of the religion of Islam. This provides them with a sense of moral superiority enabling them to identify with the moral “we” who knows what is wrong and what is right. Abu-Lughod explains that while accusing Islam of being misogynistic is easy, it is almost impossible to ask whether Christianity or Judaism are misogynistic too.

She also takes issue with the failure to recognise the sheer diversity of Muslims. There is no generalised picture. A “Muslim woman” can be an old woman in Somalia, a poor Bangladeshi peasant, a Palestinian filmmaker, a Lebanese writer or the Oxford-trained former prime minister of Pakistan. They are all Muslim women.

Abu-Lughod goes on to describe a new type of feminism emerging in Islamic societies that is different from the popular genre of Muslim women’s memoires represented by writers such as Ayan Hirsi Ali. This new type of feminist quotes frequently from the Qur’an; she is familiar with Islamic law and legal tradition, knows her rights according to Islamic law, invokes examples from early Muslim history and writes sophisticated articles. Abu-Lughod tells the story of these real women and tries to encourage her western readers to listen to their voices.

One benefit of listening, she argues, is to understand that matters are not that simple. It may also help us realise that we are not disconnected from those realities that are shaped by global politics, international capital and modern state institutions. Abu-Lughod explains all this through the stories of her real-life heroines from rural Egypt where she has spent years as an anthro-pologist. Through their stories she shows that despite western popular western stereotypes Muslim women are more than just anonymous oppressed women calling out to the West to come and rescue them. •

Lila Abu-Lughod is the Joseph L. Buttenwieser Professor of Social Science at Columbia Uni-versity, where she teaches anthropology and women’s studies.

Do Muslim Women Need saving? by Lila Abu-Lughod, Harvard University Press, 2013, £29.95

32

33

Nelson Mandela has left this world, a world which during his years as a freedom fighter gave him grief and suffering

but also later bestowed upon him international recognition and fame as peacemaker and nation builder.

Mandela’s worldwide appeal cannot be understated. Masses around the world who despaired of their own opportunist politicians grew fond of this icon of integrity and resistance. To them, he was a breath of fresh air, an aberration in an otherwise long litany of political scandals, sleaze and corruption. That is why one satirical magazine suggested that Mandela was actually ‘the first politician who was being missed’ after his death.

A Life Devoted to Struggle

Mandela could have been an African tribal chief, had he followed on the footsteps of his father. Instead Madiba, as he was affectionately known, decided to become a lawyer to help his people escape the inhumane and barbaric laws imposed by South Africa’s white settlers.

Early in his youth Mandela joined the African National Congress and emerged as one of its leading figures. He was hoping to continue on the path of non-violent resistance to the govern-ment’s racist policies, but the ruthless suppression of peaceful demonstrators forced him to engage in a campaign of subversion against the regime.

Mandela was eventually arrested for his opposition to apartheid and put on trial on charges of treason. During his trial he gave a six-hour speech which ended with his famous statement that he was ready to die for the creation of a society in which the equality of all races could be ensured.

Mandela was sentenced to life with hard labour, to be served on the dreaded Robben Island. For 13 years, he worked in the island’s quarry. Even there he continued the resistance, encouraging others to work as slowly as possible. One of his warders later said: ‘I watched him take 10 minutes to lift his pick over his head.’

On the mainland, the struggle against

Mandela’s legacy must live on Remembrance ceremonies for Mandela

have attracted a plethora of world leaders to South Africa. Reza Murshid questions if their presence does justice to the memory of Mandela

34

apartheid continued unabated despite the increasing brutality of the police. The South African youth became increasingly radicalised. As the new young firebrands arrived at Robben Island, they also came under Mandela’s influence. He quickly emerged as the person who would lead the freedom struggle.

An international campaign began in the 1980’s to secure Mandela’s release. The Pretoria regime reacted by offering him freedom from incarceration on condition that he would discontinue his political activity. Mandela rejected the offer. His message to his people was read at a rally by his daughter Zindzi: ‘Your freedom and mine cannot be separate.’ Despairing, FW de Klerk, the new South African president, decided to release him unconditionally.

After his release, the regime hoped that Mandela would become a recluse. But he became more and more the centre of domestic and inter-national attention. In 1993 Mandela received the Nobel Peace Prize along with FW De Klerk. It was the first time that a peace prize had been shared by a former prisoner and his erstwhile jailer.

In 1994 Mandela was elected as the country’s president. Some 23 million people voted the first election in the nation’s history in which blacks were given the chance to vote.

After his first term in office Mandela kept his promise to step down. He turned his attention to causes that were close to his heart; children and the fight against AIDS. He linked his celebrity status to charity to ensure some good would come out of the Mandela brand.

Nation Builder

When Mandela walked free from prison, he was a visionary without any bitterness. It was the lack of acrimony on his part that elevated him from revolutionary to nation builder. This made him stand out against most other

revolutionaries of the twentieth century who initiated civil wars in their own countries and played havoc with the unity, prosperity and dignity of their nations after they came to power.

Mandela was able to put past conflicts and tensions behind him and make South Africa the economic powerhouse that it is today. White supremacists would have you believe that South Africa was doing well before Mandela came to power. Nothing is further from the truth. The country was on a down-ward slope, its economic growth under serious strain from the anti-apartheid divestiture movement that encouraged foreign companies to pull out.

Mandela knew how to create a sense of

community and nationhood between different ethnic and religious groups in the new Rainbow Nation. In the early years of his presidency, he attended the final of the Rugby World Cup to cheer on the national team, an all-white unit playing a white game which many considered the last preserve of apart-heid.

An African Leader with a Legacy

Mandela was the first leader from the so-called Dark Continent who was taken seriously by former colonial powers. Some African leaders prior to him had not been given the chance to project themselves onto the world stage as robustly as Mandela. The colonial powers had been successful in suppressing the good qualities of African leaders by nipping them in