Islam Assembled | The Caliphate Grail: The General Islamic ...

Transcript of Islam Assembled | The Caliphate Grail: The General Islamic ...

I.

'slam Ass eThe Advent of t h e4 11 1 1 1 1 '

rnar

MARTIN KRAMER

ISLAMASSEMBLED

The Advent of the Muslim Congresses

MARTIN KRAMER

New York Columbia University Press 1 9 8 6

N I N E

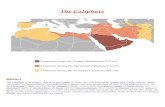

THE CALIPHATE GRAILThe General Islamic Congress for

the Caliphate in Egypt, 1926

VER TWO YEARS of intensive organizing effort preceded the0Cairo caliphate congress of May 1926. Immediately following the ab-olition of the Ottoman caliphate in March 1924, the leading ulama ofthe mosque-university of al-Azhar met and issued a proclamation an-nouncing their intention to convene a Muslim congress in a year's time,an event to which representatives of all Muslim peoples would be in-vited. The congress, convened in Egypt, "the most excellent of Islamiclands," would do no less than designate a new caliph, and so end thedisarray into which the Turkish decision had cast the Muslim world.'In Cairo, a preparatory committee of Azhar ulama planned the agendaof the congress and the invitation of delegates from throughout theMuslim world. Elsewhere in Egypt, there emerged a string of fourteen"caliphate committees," working in support of the congress and thepreparatory committee. Through additional branch committees, theirreach extended to every major Egyptian population center, and theirparticipants soon numbered in the hundreds.2 I n l i n e w i t h a t r a d i t i o n a lpolicy of religious tolerance, Great Britain had declared the restorationof the caliphate a religious problem in the solution of which Britainwould not interfere. The organizers thus were able to pursue their ac-tivities in Egypt without fear of hindrance.

But despite this declaration, the caliphate congress was not strictly areligious matter, for the royal palace had a hand in the effort. Muchevidence suggests that the organizers hoped not simply to solve theproblem of the caliphate, but to prepare the ground for an Egyptiancaliphate in the person of King Fifad I (r. 1 9 2 0-1 9 3 6 ) . T h e s e i n c l i n a t i o n s

were impossible to conceal, and the congress was shadowed by thesuspicion that its conclusions were foregone. The resulting domesticcriticism by opponents of the monarchy led to a postponement of thecongress for a year. Then the failure of the organizers to secure wideparticipation led to a modification of the agenda to exclude the actualselection of a caliph. A further blow was dealt by the simultaneouspreparation of a rival Muslim congress in Mecca (see following chapter).

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL 8 7

When the Cairo congress fi nally met, it was only to declare that thecaliphate was still possible, and that the subject demanded further ex-amination. The participants then dispersed in the anticipation that theywould elaborate upon this verdict the following year. But no effort wasmade toward this end, and the congress never reassembled.

The Cairo congress is the first for which extensive sources survive,among them proceedings and an archive. The Azhar preparatory com-mittee even published a special periodical in Cairo, as a means forcirculation of official proclamations and articles in support of the pro-jected congress. The proceedings themselves were published serially inArabic by Rashid Rida, in Urdu translation by the Indian Muslim activistand organizer cInayat Allah Khan Mashriqi, and in French translationby Achille Sekaly.3 O n t h e b a s i s o f t he p r o ce e d in g s as t r an s la t ed by

Sekaly, and the periodical press, a number of contemporary observerswrote secondary studies, o f which Arnold Tpynbee's was the mostinfluential.'

In subsequent years, various relevant memoirs and published lettersof participants appeared. A son of Shaykh Muhammad al-Ahmadi al-Zawahiri, who was a leading Egyptian participant and later Shaykh al-Azhar, published his father's reminiscences concerning the event.5 R a -shid Rida wrote a brief behind-the-scenes account, and in his publishedletters to Shakib ArsIan he also discussed the congress and its anteced-ents.° Documents from several state archival collections added muchmore to the picture from the perspective of those foreign governmentswhich saw themselves affected by the Cairo proceedings. Some of thesesources and others were combined by Elie Kedourie in his broader studyof Egypt and the caliphate question, part of which was devoted to theCairo caliphate congress.7 T h i s w a s t h e fi r s t e x a m i na t i o n t o p r es s b e yo n d

the formal proceedings to arrive at another level of evidence and inter-pretation, and there to discover a complex web of rivalries that deter-mined the course of the congress.

Two other archival collections then not available fu lly illuminate thatfurther side of the congress. The first is the archive of the Egyptianroyal palace, which contains several relevant files on preparations forthe congress and the extent of palace involvement!' The second is acollection of 133 documents which constitute what remains of the con-gress papers, and wh ich were deposited in the lib rary o f a l-Azhar.9

The initiative was ostensibly that of the Shaykh al-Azhar, but wasvery much under the supervision of his personal secretary and presidentof the higher council of Azhar ulama, Shaykh Muhammad Faraj al-Minyawi. Planning the congress alongside him were members of an

88 THE CALIPHATE GRAIL

inner circle of initiates; beyond that working group was an outer circleof aides and supporters, who lent their names and time to the effort.Among the initial supporters was Rashid Rida, who only recently haddescribed his vision of an elected caliphate in a compendium of hisideas on the subject, published in 1922. There he developed his earliercongress ideas (see chapter 3), and advocated a full-blown caliphal bu-reaucracy, under a caliph chosen by "those who loose and bind" andendowed with spiritual authority.'''

For so massive an undertaking, the organizers required a budget.Although every opportunity was taken by the organizers and the kingto deny any connection between them, the organizers turned to theroyal palace for the necessary funds from the outset, and a solicitationletter from three of the principal congress organizers to an unnamedpalace functionary gives details. The authors first dealt with the problemof creating a supportive domestic organization at the grass roots:

We believe that the spread of the appeal within Egypt will require or-ganizations in the capital of each district (mudiriyya); the creation of branchcommittees for those organizations in the countryside; and the selectionof able preachers (khutabal to spread the word, win hearts, and caressears---all to gain approval for the idea of the congress, and then to prepareminds afterwards to accept whatever is decided, so that the appeal willbe ultimately successful.

In discussing the requirements of the campaign abroad, the authorspointed to the considerable effort invested by supporters of Husayn'sMeccan caliphate in the propagation of their message:

As for spreading the word abroad, we believe that in principle this willrequire a special journal distributed free of charge throughout the Muslimworld. The congress secretariat is prepared to edit this journal. Since wecannot count on the Egyptian press to publish the tracts of the congresssecretariat, like they publish those in support of the other so-called cal-iphate [in the Hijaz], this requires haste in establishing a special journalat the congress secretariat. i t is no secret that the Hijaz, as is clearfrom a glance at Palestinian, Syrian, and other newspapers, is pursuingits own appeal through several means. The newspaper a l-Q i b l a h a s b e e nespecially designated for this propaganda. And emissaries have been sentto various lands, and will t ry to distribute publications to the pilgrimsthis year. This is how the situation appears to us. The opinion of yourexcellency is more sublime.0The answer from the palace to this entreaty does not survive, but the

periodical began to appear regularly in October 1924, in a format thatrequired a substantial outlay of money. Shaykh Muhammad Faraj al-Minyawi, the principal signatory of the solicitation, was the journal'seditor, and his editorial line exactly reflected that of his letter:

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL 8 9

A caliphate established in Mecca, among the barren rocks and amassedsands of the desert, would be an unstable caliphate parting at the seams.The beduin would plunder its strength and undermine its foundations.

Egypt at present is more independent than others, better fortified againstthe raids of Beduin (al-acrab), and freer than any Muslim land in theEast.l2The palace channeled the necessary funds through the government

ministry responsible for religious endowments, which, unlike other min-istries, fell under the direct supervision of the palace. The Shaykh al-Azhar wrote to the ministry requesting funds to cover an unexplaineddeficit, and in 1924 received EE2,500 for this purpose; the Shaykh al-Azhar accounted for the money as having been spent on the congress.13This financial connection was concealed until well after the conclusionof the congress, permitting the organizers to maintain that the congresswas strictly the initiative of a group of disinterested ulama.

It was not without cause, then, that those Egyptians opposed to themonarchy and its aggrandizement similarly opposed the congress. First,the royal family bared their internal dissensions. cUmar Tusun (1872-1944), an independently wealthy Alexandrian prince and prolific am-ateur historian, wrote to then-Prime Minister Sad Zaghlul upon theabolition of the Ottoman caliphate, asking the government's opinionon the possibility of holding a Muslim congress in Egypt to settle thecaliphate question. Tusun clearly envisioned himself as chief organizer,for he had maintained an interest in wider Muslim affairs throughouthis career, and knew Turkish and Persian. Zaghlul, in his reply, deferredthe decision to the king, so a short time later Tusun arrived at cAbdinPalace at the head of a delegation of supportive ulama to press theirrequest.14 T h ey m et on ly the first sec re ta ry , and asked him to remind

the king of their desire to organize a caliphate congress in Egypt. Butthe maverick prince was rightly considered less than sympathetic to theking's ambitions, and so the palace threw its weight behind the far lessindependent Azhar committee. Tusun, once excluded from the congressplans, began to patronize a popular Sufi shaykh, Muhammad Madi Abual-cAzaDim (1869-1937), who had already organized a r ival congresscommittee of Azhar ulama disaffected with their palace-oriented col-leagues. While the Tusun-Abu al-cAzeim committee, w ith its fewbranches, was decidedly weaker than its rival, it nonetheless complicatedthe task of the Azhar committee both within Egypt and abroad, andbecame a convenient vehicle for others hostile to the royal palace.15A group of religious zealots under the leadership of the blind ShaykhYusuf al-Dijwi (1870-1946) made the task s till more diffi cult. D ijw ihad gained renown for his leading role in the tr ial and persecution ofShaykh 'Ali cAbd al-Raziq, and was convinced of the necessity of an

90 T H E CALIPHATE GRAIL

active and vital caliphate.'6 B u t h i s g r o u p , a l s o f o r m ed i m m e di a t e l y a f te r

the abolition of the Ottoman caliphate, opposed an Egyptian caliphate,because vice-ridden Egypt was not governed by Islamic law. Egypt asa geographic and cultural entity was certainly the Muslim land mostworthy of the caliphate, wrote Shaykh Dijwi and his associates in amanifesto, but the "legal order in our country is invalid." The Afghans,who maintained the holy law of Islam, were "the single community topreserve the principles of their religion," and had succeeded the Turksto Muslim primacy. " If Afghanistan had what Egypt has, in geographiclocation and situation at the meeting point of east and west, and sci-entific and economic centrality, the Muslims from one corner of theworld to another would be stirred to recognize its amir as caliph." Egypt"could yet win for herself the affection once held for the Turks andnow held for the Afghans," but only if the king would enforce Islamiclaw, throughout the land. Shaykh Dijw i guaranteed that he and hisfollowers then would respond by promoting the caliphate of the Egyp-tian royal house.17 T h e p a l a c e w a s n ot e n t hu s i as t i c a bo ut this s u gg e st i on ,

resented the unfavorable comparison of Egypt with Afghanistan, andlater had the police open an investigation of Shaykh Dijwi's group.According to an official communiqué, "they were occupied with a ques-tion that did not concern them."18Opposition then began to spread beyond the ulama in the Tusun-Abu al-cAzaDim and Dijw i circles to various liberals and nationalistsanxious lest the palace wield the caliphate to intimidate domestic rivals.The political struggle within Egypt had intensified in 1924, with theelection and installation of a Wafdist government led by the nationalistleader Saccl Zaghlul (1857-1927), who had just returned from exile. I twas not long before tension developed between the Wald and the palace,and between the two central actors in the Egyptian political arena,Zaghlul and King Read.

Zaghlul as prime minister initially wavered on the question of anEgyptian caliphate, but then decided against seeking the title for Egypt'sruler.19 H is i nt er io r minister and nephew, Fath Allah Barakat, issued

orders to provincial governors that they withhold all assistance fromthe Azhar caliphate committees, and banned sharica court judges fromserving as members.2° A t a l a t e r d a t e , a f t er Z a g hl u l h ad r e si g ne d his

ministry, his party went so far as to subsidize the Tusun-Abu al-cAzaDimcommittees, so resolute was the Wafdist determination to thwart thepalace's designs.21 I n s u c h a c h a rg e d p o l it i c al a t mo s ph e re , the c on gr es s

plans suffered from their association with the ambitions of the Egyptianruling house. The appearance of serious domestic opposition was thusthe most probable cause of the Azhar committee's January 1925 decisionto postpone the congress for one year.22

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL 9 1

Domestic opposition could not forestall indefinitely a project whichenjoyed the open support of Azhar ulama and the covert aid of theroyal palace. The issue soon became not whether the congress wouldtake place, but who would arrive from Muslim states and communitiesbeyond Egypt to participate in a forum very likely to insist upon Egypt'scentrality in Islam. According to Rashid Rida, who served on the pre-paratory subcommittee for invitations, the Azhar committee appealedto kings, sultans, princes, and heads of important religious societiesthroughout the Mus lim world, to respond and participate. Sectariandifferences were disregarded: Wahhabis, Ibadis, Zaydi and TwelverShicis, and even the Agha Khan of the Ismacilis, were invited, althoughthe question of the caliphate was not posed to these sects by the Turkishact of abolition.23 Y e t h e r e a g a in , t he i d e n ti fi c at i o n of the c on gr es s with

the palace, and the fragmented state of Mus lim opinion, worked todefeat the organizers.

One instance concerned the dissemination of the Azhar invitation inShici Iran. On his own initiative, the Egyptian minister to Iran, cAbdal-cAzim Rashid Pasha, lobbied at Teheran and Qumm to convince boththe government and leading Shici ulama to send authorized delegatesto Cairo. The first evidence of cAbd al-cAzim's activity dates from Oc-tober 1925, when he inserted an article in a Baghdad newspaper stronglyattacking the Abu al-cAzaim caliphate committee.24 B y N o v e m b e r , h ehad successfully planted a eulogistic front-page article about King FuDadin an Iranian newspaper; the piece, printed under a portrait of Egypt'smonarch, described Read as "defender of Is lam."25 I n M a r c h 1 9 2 6 , aSoviet radio broadcast to Iran criticized the caliphate congress, and cAbdal-cAzim responded by inserting counter-propaganda in two Iraniannewspapers.26 T h i s s e r v ic e he p ai d f or : "The n ew sp ap er business will

do absolutely nothing without recompense," for "the state of povertyin this country has a great effect on any service in all branches." Helamented "the weak means that the foreign ministry has put in ourhands—the sum of 150 pounds."27In January 1926, cAbd al-cAzim opened a round of personal diplomacywith a visit to Qumm for meetings with religious figures. The ulamaexpressed their concern about the recent territorial gains of the Saudimovement in Arabia, and this gave cAbd al-cAzim a chance to discussin detail Egypt's pursuit of an anti-Wahhabi policy "since the time ofMuhammad cAli Pasha."28 B u t i t w a s n o t u n t i l F e b r ua r y t h at t he E gy p-

tian minister heard that the caliphate congress was scheduled definitelyfor May. He immediately warned his superiors that "this country hasa strange belief about the caliphate," citing Twelver Shici doctrine, butthis did not deter him.29 D u r i n g M a r c h , h e r e c e iv e d a b a tc h of p r in t ed

invitations to the congress from Husayn Wali, one of the Cairo organ-

92 T H E CALIPHATE GRAIL

izers, with a request that the Egyptian minister distribute them. Thishe did, through the Iranian premier, all the while stressing that timewas short and urging speedy replies.30In fact, as Sir Percy Loraine reported, the Iranian government was"rather embarrassed" at the suggestion that Iran partic ipate,3' a n d a nelaborate game of evasion began. The Iranian premier informed cAbdal-cAzim that the decision rested with the ulama, but the ulama repliedthat the decision rested wi t h the government. Wh e n cAbd a l-cAzimpressed Iran's minister o f information, he was to ld that the ulama hadagreed in principle to participation, but final word was delayed becauseof difficulties in contacting Shici authorities in Najaf. Could the congressbe postponed? cAbd al-cAzim countered that the ulama had told himthat they were in total agreement, and that the matter was in the handsof the government. The Iranian minister replied that the ulama spokewhat they knew to be false themselves, because the real diffi culty wastheir inability to agree on who would represent them at Cairo.32cAbd al-cAzim began to appreciate the futility of his efforts. An in-timate of Riza Shah told him that the Shah preferred to see the congressconvened in the Hijaz, as he was certain that the ruler of any otherhost country would be elected caliph. The holy cities were the gibla ofall Muslims, and therefore neutral sites. cAbd al-cAzim tried at lengthto explain that Cairo was an equally neutral site, but parted discouraged."The circumstances which I witness here weaken any hope that Iranwill accept the invitation to the congress."33A prominent calim then astonished cAbd al-cAzim with yet anothercounter-proposal: Najaf was a more appropriate site for the congress,since Egypt was under British influence. cAbd al-cAzim replied thatNajaf was located in territory under British mandate, while Egypt wasindependent, and he saw in this a further sign that Iranian participationwas unlikely ." cAbd al-cAzim suggested to his own government that,in order to secure Shici cooperation, the agenda of the congress beexpanded beyond the caliphate question to matters of general Musliminterest.35 B u t b y t hi s t ime , the Br it ish au tho ri ti es in Egypt had become

rather annoyed with cAbd al-cAzim's lobbying. Unenthusiatic them-selves about the congress, they thought it better that Iran abstain fromparticipation, and that cAbd al-cAzim be instructed that Iranian rep-resentation was a matter between Azhar shaykhs and Persian mullahs,not diplomats and foreign ministers.36 W i t h i n a m o n t h , c A b d a l -c A z i m

was sent a reprimand from the Egyptian royal diwan, informing himthat the invitation to the congress was solely the work of men of religion,and that the Egyptian government had no official connection with thecongress.37

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL 93

Perhaps the British insisted on the reprimand; perhaps some Egyptianauthority decided that reluctant Iranian attendance was more a liabilitythan an asset to the ultimate election of Read as caliph. cAbd al-cAzimcould offer only this apology: " I f I discussed the matter, it was becauseI saw it as my obligation toward an invitation issued from my country."38When the Shaykh al-Azhar finally wired an invitation, the Iranian gov-ernment announced that the Shici ulama had not had adequate time tostudy the caliphate question, and authorized Iran's diplomatic repre-sentative at Cairo to attend only as a spectator.39With the establishment of Saudi control over the holy cities of Arabia,reading Saudi attitudes assumed a new urgency. In a letter to the Shaykhal-Azhar, Ibn Sacud had promised his support for the Cairo caliphatecongress provided that the participants represented the majority of Mus-lims. He declared himself willing to recognize the decision of such acongress as binding, and denied any personal caliphal ambition:4° B u the feared that an elected caliph—particularly a Egyptian one—mightlay some claim to the holy cities only recently occupied by his forces.The Egyptians already had attempted to establish a religious protectorateover the Hijaz, shortly before the triumph of Saudi arms.41 T h e C a i r oorganizers thus could not have been surprised when Ibn Sacud sent nodelegate to their congress, for he had little to gain from its success, andmuch to loose from a decisive outcome.

The Azhar committee anticipated more from Muslim India, wherethe fate of the caliphate had evoked profound concern among Sunniand Shici alike. The Indian Khilafat Committee, under the leadershipof two brothers, Muhammad cAIi (1878-1931) and Shawkat cAli (1873--1938), commanded a following which reached the proportions of a massmovement in the early 1920s, and the Azhar committee regarded theparticipation of the organization in the Cairo caliphate congress as criticalif the resolutions of the projected congress were to bind this largestMuslim community. But the Khilafat Committee leaders were wary ofEgyptian intentions. When rumors reached Delhi in late March 1924that the Azhar ulama planned to proclaim Read caliph, Shawkat cAlicabled Sacd Zaghlul from Delhi expressing the hope that Egyptian ulama"do not intend any hasty action regarding future of khilafate." TheKhilafat Committee was attempting to convince the Turks to appointone of their own to the office, but should this effort fail, "future ofkhilafate should be left to be settled by proposed world muslim con-ference.'42 S h aw k a t c Al i w ar ne d the Shaykh al-Azhar that "undue haste

in [a] matter of such grave importance is likely to be as dangerous asundue delay or neglect."43 L a t e r S h a w k a t c A l i a s k ed f o r d e t ai l s a bo u t

the way in which the caliph would be selected. He hoped for unanimous

94 THE CALIPHATE GRAIL

agreement, but "Muslims of the far distant places would be fewer com-pared with local visitors who could swamp them easily. I think eachcountry must be assigned votes on a population basis though it maysend only fewer representative[s]." He anticipated the dispatch of alarge Indian delegation, but "there have not been wanting men whosuggested that Cairo would not be a suitable place for the Conferenceas there was a chance of official interference [which] would like tounduly influence its deliberations."'"

An opportunity to make the Egyptian case in person was presentedto Azhar ulama in the summer of 1925, when two of the leading lightson the Khilafat Committee, Mukhtar Ahmad Ansari (1880-1936) andHakim Ajmal Khan (1863-1927), reached Egypt during a tr ip to theMiddle East. Ansari once had been an unrestrained Turcophile, and asa physician educated in England had led the All- India Medical Missionto aid Ottoman war wounded during the Balkan campaign in 1913. Hewas familiar with the charges leveled against the proposed congress,and so the task of the Egyptian organizers was not an easy one. Ansarihad already made this plain. Attending a reception in his honor duringa stopover in Jerusalem, he mentioned a number of congress sites pre-ferred by Indian Muslims, but ruled out Egypt because of the presencethere of a strong party determined to resolve the caliphate issue in favorof King FuDad.45In Cairo, the Azhar ulama, Shaykh Minyawi foremost among them,encircled Ansari and Ajmal Khan from the moment they descendedfrom their train. The Indian Muslim envoys were polite, but seemed toprefer the company of Shaykh Abu al-cAza'im, with whom they metoften. By this, they gave cause to conclude that the Indian KhilafatCommittee shared in the critique of those Egyptians opposed to thecongress.46 L a t e r, S h aw ka t cA li wrote to Abu al-cAzaim in a congrat-

ulatory tone, and the Tusun-Abu al-cAzaim committee began to speakof itself as if in close association with the Khilafat Committee.47 T h efinal decision taken in Delhi was not unexpected. Once Ajmal Khanhad returned to India and met with the 'Ali brothers, they togetherdecided to formalize their abstention by declining the Azhar invitation.Ansari, who was still in the Middle East, gave this explanation:

The present circumstances are not propitious for holding the congress, inview of the political controversy and dispute over the constitutional rightsof the [Egyptian] people, and the circulation of the rumor abroad that theulama of al-Azhar are motivated in this course by a hidden force, em-ploying spiritual, religious influence in a struggle against the nationalistparties that are demanding the rights of the people. I do not credit theserumors with truth for a moment. But the insistence of the ulama in holdingthis congress in Cairo despite the wi l l o f all the other Muslim lands

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL 9 5

encourages belief in these rumors and their expression as established facts.I would not want my Egyptian brethren, who deliberate and think overtheir every action, to damage their position of centrality in the Muslimworld.

If the Egyptian ulama elected a caliph alone, Ansari warned that thisfigure would become "the laughingstock of the Mus lim world." Heinstead advocated an annual Mus lim congress, based upon what hedescribed as proportional representation and so empowered to elect atruly popular caliph.48 M u s l i m I n d i a w a s u l t i ma t e l y r e p re s e nt e d at the

Cairo congress by a single participant, cAllama cInayat Allah KhanMashrigi (1888-1963), a Cambridge-trained mathematician, teacher, andlater founder of the militant pro-Axis Khaksar movement. Althoughlater a man of influence, he was not yet well known, and the lack ofan authoritative Indian Muslim voice at the congress was an unconcealedblemish.49The participation of an important Indonesian delegation would alsohave done much to enhance the findings of a caliphate congress heldin Cairo, for in the Indo-Malay periphery was a populous Mus limcommunity which had drawn closer to Egypt, al-Azhar, and the ideasof Islamic reform as propounded by Muhammad cAbduh and RashidRida in al-Manar.5° A n a l l i a n ce o f p o l i ti c a l a c t iv i s ts and u la ma in Java

had succeeded in creating and directing a mass organization, the SarekatIslam, under the leadership o f Umar Sayyid Tjokroaminoto (1882—1934).51 R as h id R ida , who had his own correspondents in Java, dis-

patched the congress invitations to Sarekat leaders. In December 1924,four to fi ve hundred Sarekat activists met at Surabaja to select themovement's delegates to Cairo and to determine the policy which theywere to represent. Three members from Java were selected to proceedto Cairo and convey the Sarekat plan, which argued that the powersformerly exercised by the caliph should be delegated to a council, themembers of which would be chosen from various Mus lim countries.The president of this council, elected by its members, would assumethe title of caliph.52It soon became known that the smaller but expanding Muslim re-formist movement, the Muhammadijah, based both in Java and westernSumatra, had also been invited to send a delegation to Cairo, and plannedto do so.53 N o w t he S ar ek at Islam and the Muhammad ij ah were then

experiencing a period of heightened rivalry, so that Tjokroaminoto be-gan to disparage the rival delegation's mission, and to insinuate thatthe Sarekat Islam might not participate in the Cairo congress after all.By the time of embarkation, he had hear rumors that King Fu'ad wouldbe declared caliph at Cairo, and this he made the pretext for possibleabsentation. "As matters stand," he declared once embarked, "we have

96 T H E CALIPHATE GRAIL

heard nothing as yet from the Committee at Cairo which sent out theinvitations. It is not impossible that the English may endeavor to bringtheir influence to bear by causing King Read to be proclaimed Caliph.If such a thing should occur—in other words if the Caliphate is to haveits seat at Cairo—then, so long as I am a representative of Dutch India,I will never give my consent to the proposal, which would be in conflictwith the Koran."54During a stopover in Arabia, Tjokroaminoto allowed himself to beconvinced that such a development would be the inevitable outcomeof a caliphate congress held in Cairo, and he did not bother to proceedto Egypt. The Azhar caliphate committee had to rest content with atwo-man Muhammadijah delegation, led by the Sumatran reformer Abdal-Karim Amrullah [Hadji Rasul] (1879-1945).5' T h i s w a s a d i s a p p o i n t -

ment, one which assured that the decisions of the caliphate congresswould become embroiled in the divisive domestic politics of one of themost populous quarters of the Muslim world.

It was also hoped to attract Muslims from another important andpopulous region, the Soviet Union. An invitation was extended to MusaCarullah Bigi[yev] (1875-1949), a Tatar colleague of Ismail Gasprinskii's,and a reformist publicist and theologian who had studied many yearsearlier in Egypt. While there, Musa Carullah had known cAbduh per-sonally, and wrote a lengthy study of Afghani and cAbduh.56 M u s aCarullah had no sympathy for national communism, but chose none-theless to remain in the Soviet Union and attempt to reconcile his faithwith communism. There he received four invitations to the caliphatecongress from the Azhar organizers, and he decided to attend.57 B u tshortly before his departure the mufti of Ufa denounced the impendingcaliphate congress as under the thumb of "imperialist" (British) dom-ination.58 M u sa C ar u ll a h a lmost cer ta in ly did not share this view of the

congress, but Egyptian consular authorities in Istanbul did not knowthis; and when Musa Carullah arrived on his way to Egypt, they ap-parently became concerned lest a Soviet Muslim delegate appear at thecongress and disturb the proceedings by making a similar accusation.The Egyptian consul refused to issue Musa Carullah a visa, leaving himmuch perplexed and unable to attend the proceedings.59The presence in Egypt of influential North African and Syrian com-munities had led Egyptians to consider these regions as immediate cul-tural and political hinterlands.60 T h e p a r t i c i p a t i o n o f M u s l i ms f r om

North Africa and Syria in the Cairo congress was probably regarded asa minimal requirement for success, and it was perhaps for this reasonthat the Azhar committee took an ususual step to assure participation.A secret appeal was made to France, which ruled Algeria, Tunisia, andSyria.

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL 97

This subject was first raised in discussion with the French ambassadorin Cairo, Henri Gaillard, in November 1924: "The persons who arepreparing the congress have spontaneously asked me to single out, ontheir behalf, those Muslim figures in Algeria, Tunisia, and Syria, whoseem to me the most suited for participation in the congress." In Gail-lard's opinion, France stood to benefit from compliance with this request,for if French authorities did not provide a list of names, the selection"risks being guided by those Syrian and North African elements inCairo or Alexandria who are the least favorable to France."51Gaillard's argument was discussed at length by the Commission In-terministerielle des Affaires Musulmanes sitting in Paris. On the onehand, some held the v iew that too much was at stake for France toadopt a policy of nonintervention in a question as important as that ofthe caliphate. The Cairo congress might emerge as a significant politicalevent directly affecting French interests. Critics of this opinion held thatthe congress, if left alone, was liable to fail to agree on the selection ofa caliph and so collapse, and that France could best contribute to thisresult by preventing the dispatch of delegates from her Muslim pos-sessions. Eventually the Commission settled on a compromise. If, despiteall the apparent obstacles, the congress seemed about to take place, thenFrance would communicate a list of participants to the organizers at thelast minute. These participants would not really participate at all, butwould act strictly as informants, for it would be hazardous to impartprecise instructions to them in favor of one or another policy :52The Quai notified Gaillard that he would receive a list of participants.He was instructed to use his judgment in choosing the moment fortransmitting the lis t to the Azhar committee, and was cautioned thatthis moment be deferred as long as possible, to avoid the controversieslikely to arise from the selection.63 G a i l l a r d a g r e e d . " B u t n o s u c h l i s t s

were ever compiled. The Governor General of Algeria, when asked tosupply names, expressed himself certain that the congress would notmeet or would fail if it did, "the Muslims not having proven, at anytime, their aptitude in the organization of a council on this scale." Hetherefore did not now wish to transmit such a list, for he felt that noprecaution could prevent its being leaked, thus provoking an unhealthypublic discussion concerning those selected. A list of qualified AlgerianMuslims would be submitted i f the congress seemed inevitable, butcommunication of a list of names from Algiers would be deferred untilthe last possible moment:55 A t t h e s a m e t i m e , t h e G o v e rn o r G e ne r a l

prevented the rise of a sympathetic movement in Algeria. cAbd al-HamidIbn Badis (1889-1940), Algeria's leading Muslim activist, wrote to theorganizers in Cairo that the French did not want Algerian notables toparticipate in the congress, and that he doubted whether he could rep-

98

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL

resent Algeria because formation of a local committee was "impossi-ble."66The French High Commissioner in Beirut felt otherwise. He believedthat Syrian Muslim participation was inevitable, and that prudent prep-aration was essential. From Syria he proposed to send to Cairo onlyreligious personalities of indisputable character, chosen with discretionand uninvolved in agitation against the French. "Without imposingcategorical instructions on the delegates, it would be politic to directthem toward the candidature [for the caliphate] that seems most ad-vantageous to the interests of Syria and those of France in the East. Inorder that the actions of these delegates not be contested, it is essentialthat they appear to have escaped our direc tion."67 B u t h e r e a g a i n n olist was prepared, for once the postponement of the congress was an-nounced by the organizers, Gaillard wrote to Beirut that the collectionof names had become "pointless."68 T h e A z h a r c o m m i t t e e , d e s p i t e h a v -

ing gone so far as to solicit the names of participants from a non-Muslimpower, thus had achieved nothing, and once left to its own devicesachieved no success at all in the matter of Syrian participation. Theémigré Syrian activist Shakib Arslan showered advice upon the com-mittee from his European exile, but he would not attend.69 T h e s e l f -exiled Tunisian reformist and activist cAbd al-cAziz al-Thacalibi, thenin Iraq, did accept an invitation, but he preferred to be admitted as amember of the Iraqi delegation, for reasons which he did not make clear.The caliphate committee which did function in Tunis sent no repre-sentative, for it had been deterred by Abu al-cAzalm's campaign againstthe congress.7°

Shortly after the renewal of the Azhar committee's activities, the vice-rector of al-Azhar wrote a letter to cAbd al-Karim (1883-1963), leaderof the Riffi an resistance against the Spanish protectorate in northernMorocco and the French-supported ruling cAlawi dynasty, requestingthat the resistance movement send delegates to the congress!' Furtherletters from cAbd al-Karim to the Azhar committee, intercepted byBritish postal authorities at Tangier, indicated that the correspondentswere on close terms, and that funds were being dispatched secretly bythe Azhar committee to cAbd al-Kar im.72 B y t h e i r c u l t i v a t i o n o f c A b d

al-Karim, the Azhar committee hoped to attract a delegation of somestanding from a distant region, an aspiration still unfulfi lled only threemonths before the rescheduled congress. In cAbd al-Karim, the com-mittee found a willing party from a major geographic periphery, onewho, because of his embattled position, enjoyed a prestige in the widerMuslim world conferred by a continuing resistance to foreign encroach-ment.

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL 9 9

Upon learning of this invitation, Gaillard immediately complained tohis contacts at al-Azhar. "I have informed the committee that to inviteor accept delegates from Abdelkerim is not admissible, for the doublereason that Abdelkerim has revolted against the sovereign of his country,and because that sovereign is recognized as caliph in Morocco."73 T h ecommittee replied to Gaillard defensively and untruthfully , claimingthat cAbd al-Karim had solicited the invitation himself, and Gaillarddid not pursue the matter further.74Far more persistent, and ultimately successful, was Spain, cAbd al-Karim's principal battlefield adversary. A note verbale delivered to theEgyptian legation in Madrid by the Ministerio de Estado spoke of the"profound displeasure that would be caused in Spain by anything whichwould signify official or semi-official recognition of this political per-sonality, or would demonstrate deference toward representatives of achief in rebellion against the legitimate authority of the Spanish Pro-tectorate of Morocco."75 W h i l e t h e E g y p t i an s c o n s id e r e d t hi s r e qu e st ,

the Spanish ambassador in London pressed British authorities to makeBritish influence in Egypt felt among the members of the Azhar com-mittee.76 A sk e d f or his comments on this Spanish request, Lord Lloyd

in Cairo argued that, "while realising that the presence of Riff delegatesat Cairo might be inconvenient to the Spanish Government, I ventureto deprecate any intervention on our part in such a delicate matter," onaccount of British neutrality in all that was related to the issue of thecaliphate.77 A B r i t is h F o re i gn O ffic e o ffic ia l thus informed his Spanish

opposite number that "to our regret we cannot usefully take any suchaction as that suggested."78But this exchange was overtaken by events, for the Egyptian gov-ernment decided on its own accord to satisfy Spanish desiderata in anote verbale disclaiming all connection with the congress, and professingnonrecognition of the "rebel" cAbd al-Karim. "In order to bear witnessto its desire to maintain the best relations with the Spanish government,the Egyptian government is disposed to refuse entry to delegates of thisrebel into Egyptian terr itory ."79 E g y p t i a n a u t h o r i t i e s a d h e r ed t o t h is

policy, and the interests of Morocco were defended at Cairo by a shaykhof a religious order, described explicitly in a French diplomatic sourceas a Spanish political agent.K

With the approach of the revised congress date, the organizers of theCairo congress, in surveying the results of their campaign abroad, werebound to concede that an attempt to elect a caliph on such a narrowbase would inv ite profound embarrassment. Yet the Azhar and thecongress were far too intertwined for the committee, after nearly twoyears of highly publicized work, to cancel the event without even greater

100 T H E CALIPHATE GRAIL

embarrassment. Resort to the option of another postponement wouldhave opened the committee to intensified charges of political incom-petence and organizational ineptitude. At a meeting of the preparatorycommittee in late A p ri l 1926, Shaykh Mustafa a l-Maraghi sought anhonorable exit f rom this impasse by suggesting a fundamental revisionof the congress agenda. No longer would the congress aspire to elect acaliph. Instead, it would define the caliphate, determine whether it wasnecessary, determine the personal requirements of the office, and decidewhether it was now possible to establish such a caliphate. If the caliphatewas deemed impossible in this age, the congress would determine whatmeasures to take. If it was deemed possible, the congress would searchfor the appropriate means of selection.8' B u t t h e c o m m i t t e e w o u l d d e l e t e

from the agenda the discussion of the candidates and the selection orelection of one as caliph. This probably reflected the discouragementof King RIDad, who told Gaillard two months before the agenda revisionthat the congress would be a short one and would not designate a caliphbecause the Muslim world was too thoroughly divided over the issue."

With the opening of the congress, the extent of the defeat in thematter of participation became embarrassingly manifest. The Egyptianorganizers were there in force, and a sizable delegation of notablesdescended from Palestine by train. Otherwise, attendance was meager.Even Rashid Rida, who actively participated in the organizing com-mittee, and later published the proceedings, did not attend in person,and privately predicted disaster for the impending congress." At anearly stage, he diagnosed the faults of his fellow organizers, to whichhe made this allusion: "The important thing is that our colleagues, themembers of the preparatory committee here, lack everything that isessential in both intelligence and initiative for this project. I cannot saymore than this ."84

To these two years of controversy and negotiation, the actual pro-ceedings of the congress proved anticlimactic. The congress divided intothree committees, which prepared reports for the plenum on varioustheoretical aspects of the caliphate. But the preparatory committee hadset down a charter (see appendix 5) which established procedures, andthe discussion of the constitutional gaps left by this document occupiedmuch of the time of the plenary sessions. The argument revolved aroundthe manner in which resolutions were to be adopted. The Egyptianorganizers were eager to pass on to substantive questions, bu t otherparticipants insisted that internal regulations be set down with greaterclarity. "The congress has already held three sessions, and th is is thefourth [and last]," said Shaykh Min ya wi urgently, " ye t we have st ill

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL

done nothing. We did not assemble to discuss secondary questions, butto present Muslims with useful work ."85 T h e c o n s t i t u t i o n a l p r o b l e m s

were never fully sorted out, but were left aside at Egyptian insistence.On substantive issues, the congress essentially divided along Egyptian

and non-Egyptian lines. The former group was led by the Azhar or-ganizers, and the latter by cAbd al-cAziz al-Thacalibi, who had oncebefore played this role of opposition-bloc organizer. During the Pil-grimage Congress of 1924 in Mecca he had thwarted Husayn of Mecca,and for this reason probably was invited to Cairo. But now he turnedhis organizing skills as spoiler on the Azhar organizers themselves.Thacalibi was overheard by a police agent in his hotel lobby planningwith other non-Egyptians to disturb the work of the congress, the Mo-ment it touched on the issue of candidacy for the caliphate(' The objectof the Egyptian organizers was to avoid such a disturbance, yet preventany decision that precluded a future caliphate of the Egyptian rulinghouse. To those who claimed that Qurashi descent was an essentialattribute of the caliphate—a condition which would have ruled out anEgyptian caliphate—the Egyptians insisted that historical practice hadinvalidated the requirement. To those who claimed that the caliphatewas no longer possible at all, given the sorely divided state of the Muslimworld and the inability of any one Muslim ruler to defend it, ShaykhZawahiri responded in for c e7 A c a n d i d a t e e l e c t e d b y a s u b s e qu e n t

congress, i f that congress were more representative, would meet therequirements of the sharica by virtue of his election by a consensus ofMuslims.88In this manner, the congress, after only four plenary sessions heldover less than a week, resolved itself into a decision to convene againthe following year, in what it was hoped would be a more representativefashion. The participants, without apparent enthusiasm, committedthemselves to establishing branches in their own countries, and theyassented to a proposal that the next congress take place in Cairo. I tseems that the agenda for the following year was then to be determinedat the banquet which closed this fi rst congress, but a reporter wrotethat the participants passed the banquet in eating rather than discussion,and most went home without any idea of what the next caliphatecongress would under take9

Even before the first congress, Rashid Rida had proposed that it meeta second time, and each Muslim territory would have one vote in thereconvened assembly. He even offered to write a tract on the caliphatespecifically for submission to such a congress.9° B u t t h e r e i s n o e v i d e n c e

that any attempt was made by the organizers to reconvene the congress

102 T H E CALIPHATE GRAIL

the following year. For all intents and purposes, the General IslamicCongress for the Caliphate had folded.

The experience was not wholly without a sequel, for Shaykh Mustafaal-Maraghi apparently felt himself capable of achieving what the Azharcommittee had not achieved. He had contributed something to the ges-tation of the congress idea, with his proposal of 1915 (see chapter 5).He had also participated in the preparations for the 1926 congress,although the failed event was essentially the work of others. In lateryears, with the elevation of a young, charismatic king in the person ofFaruq I (r. 1936-1952) his former tutor Maraghi rose in stature. AsShaykh al-Azhar, he began once more to work discreetly for the emer-gence of an Egyptian king-caliph, and to campaign openly for a Muslimcongress.

The congress suggestion this time reappeared not in the formal contextof the caliphate—an invitation to certain defeat—but in the less con-troversial framework of Sunni–Shici reconciliation. In this initiative,Shaykh Maraghi had an active ally. "For more than a year, I have beentrying to lay the foundations for an accommodation between the Sunnaand the Shica." cAbd al-Rahman cAzzam, Egypt's minister to Iraq in1938, justified his overtures by pure raison d' [,tat , i n a d i p l o m a t i c d i s p a t c h

to Cairo:

Al-Azhar would become the principal school of Islam in the world, inwhich the people of the various Islamic schools could study their fiqh.

this would strengthen Egypt's religious influence among the Shica ofIraq, Yemen, Iran, Afghanistan, and India, and naturally would be fol-lowed by an enhancement of Egypt's political centrality. Experience showsthat the political influence drawn by a state from a religious appeal is asturdy and strong one, resistant to the vicissitudes of t ime '

cAzzam Pasha reported that he already had approached influential Iraqipoliticians and ulama, including three of the most prominent majtahids:Shaykh Muhammad al-Husayn Al Kashif al-Ghita', Shaykh cAbd al-Karim al-jazaDiri, and the made a l-t a g h d , A y a t A l l a h A b u a l -H a s a n I s -

fahani. To them, he spoke of Muslim unity, the need for a Mus limcongress to examine religious issues, and the role of al-Azhar as a uni-versity for all the sects of Islam.

Where had these ideas originated? A year earlier in Egypt, cAzzamhad raised these issues with Shaykh Maraghi, who had been in fullagreement. The diplomat now asked his foreign ministry to presentthree concrete proposals to the Shaykh al-Azhar. cAzzam suggested firstthat Maraghi visit Najaf and Karbala, an act which cAzzam expectedwould have a tremendous effect; second, that al-Azhar accept studentsfrom madhahib other than the Sunni four, and allow these students to

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL 1 0 3

study flak from ulama of their own madhahib; and last, that ShaykhMaraghi "call for a general Islamic congress among the ulama, whosepurpose will be religious," and whose task would be the reconciliationof the various sects ( a l-t a g r i b b a y n a a l-m a d h a h i b ) .9 2 T he f o r ei g n m i ni s t ry

acceded, and sent a copy of 'Azzam's dispatch to Shaykh MaraghL93But the initiative had already been taken. In late October 1936, 'Abdal-Karim al-Zanjani, a Najafi calim, arrived in Egypt for a stay whichlasted nearly two months. Shaykh Maraghi held a tea party for him,and the Shici rapidly became a popular speaker around Cairo's Muslimactivist c ircuit.94 Z a n j a n i' s t h em e w as t he i d en t it y of Sunni and Shii

interests, and his biographer devotes a chapter to a comparison of Zan-jani and _lama' al-Din al-Afghani.95After Zanjani's return to Iraq, Shaykh Maraghi began to correspondwith him. Maraghi's hope, he once confided to Lord Lloyd, was thatMuslim countries would send delegates "to sit on a permanent sort ofSupreme Islamic Council, eventually to be established at Cairo, whereall questions affecting any one of them as a member of the IslamicUnion, would be considered and a common policy formulated."96 T othis end, Shaykh Maraghi began to speak openly of a reconciliation ofthe sects,97 a n d d e ci d ed to i nv ol ve the Shii Twelver community of Iraq

in this plan through his new acquaintance. Zanjani does not appear tohave counted for much at Najaf, and certainly there were ulama of farhigher standing and distinction to whom Shaykh Maraghi might haveturned. That the Shaykh al-Azhar chose to cultivate Zanjani was perhapsrelated to the Iraqi caiim's past fl ex ibility in matters concerning thecaliphate. In 1924, Zanjani offered his allegiance to Husayn of Meccaas caliph.98 T h i s a c t, u n co n ve n ti o na l by any Twelver Shici standard, set

Zanjani squarely on the side of political expendiency in matters of thecaliphate.

And to Shaykh Maraghi this was essential. For at exactly the sametime, he had won over the leader of Ismaili Shicism to a radical prop-osition: "Before his departure [from Egypt]," wrote Lampson in Cairo,"the Aga Khan enformed me on February l l t h of the gist of his con-versation with Sheikh el Maraghi. He said that the Sheikh had quotedhistorical precedents for local rulers assuming local Caliphate titles inthe past. Sheikh el Maraghi had urged that the same thing could properlybe done in Egypt today, and if done by one Muslim ruler, it woulddoubtless be done by others."99Shaykh Maraghi first asked Zanjani's opinion of the proposed Muslimcouncil in February 1938.100 Zanjani replied favorably, but then addedtwo reservations. He first stressed that the Shici public believed thatgovernment appointees were removed from divine favor, and so rep-resentation on the council had best be nongovernmental. His second

104 T H E CALIPHATE GRAIL

point was that a site free from foreign influence was essential to thesuccess of the plan."' Maraghi answered that he too preferred men ofreligion as delegates, but saw no reason not to include some prominentfigures who were not ulama. He avoided the question of the proposedsite by not mentioning it, and went to some pains to assure Zanjanithat he had not made an attempt through official channels to transformNajafi religious institutes into appendages of al-Azhar, although he didhope for closer t ies .102Just below the surface of the correspondence was an evident tension.Zanjani had successfully conveyed to Maraghi that he understood theShaykh al-Azhar's centralizing aim, and was not much in sympathywith an Egyptian bid for ascendancy. Another source reported thatZanjani "did not commit himself to any opinion regarding the suggestionthat King Faruq should be proclaimed c aliph."03 Z a n j a n i h a d d r a w n h i s

line on the wrong side of Shaykh Maraghi's plans; with the collapse ofhis scheme for a Muslim council, Maraghi severed his Najaf connec-tion.'" The Shaykh al-Azhar did not visit that city, and appears to havemade no further initiative to secure a Shici constituency. Dur ing thesubsequent six years until his death, Shaykh Maraghi occasionally re-turned to the congress theme, but did not pursue it actively, and noserious attempt was ever again made in Egypt's era of constitutionalmonarchy to convene a Muslim congress in Cairo. There were those inthe palace who continued to covet the caliphate for Egypt, but theysought to win their prize by guile, as in January 1939, when a palace-inspired crowd acclaimed Faruq caliph as he departed from Friday pray-ers."05This expressed the loss of self-assurance caused al-Azhar by the Cairocaliphate congress. Much of the argument for Egyptian primacy restedon the claim that Cairo, as the cradle of al-Azhar and modern Muslimreform, was entitled to the deference accorded the capital city of a faith.This assertion substituted theological preeminence for military prowessas the principal attribute of centrality in Islam, and then insisted uponthe absolute supremacy of Egypt in the field of Muslim learning. Neitherassumption had made much headway beyond Egypt. Military prowessstill counted for a great deal, and made for the continued prestige amongMuslims enjoyed by republican and secular Turkey. And even thosewho recognized the importance of cultural and theological primacy werenot bound necessarily to Egypt. At the turn of the century, al-Azhar,underminded by self-imposed isolation and state neglect, was s t illroughly equal in stature to institutions of Muslim learning in Tunis,Damascus, and Deoband. The subsequent transformation in the Egyp-tian preception of Egypt's relative standing in Islam owed much to theextensive reform of al-Azhar. It was also tied to the emergence of the

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL 1 0 5

Shaykh al-Azhar as the preeminent religious dignitary within Egypt,finally superseding the leaders of the two great Egyptian religious con-fraternities.1c6

But the effects of these changes had not been felt beyond Egypt whenthe Cairo caliphate congress put them to a rigorous test. The resultswere unfortunate, for al-Azhar's preeminence was not widely acknowl-edged, a fact which the congress exposed but could not rectify. Theimpact in Cairo, both in al-Azhar and the royal palace, was chastening.Egypt's bid for the caliphate and primacy in Islam survived the setbackof 1926. But the technique of the Muslim congress was shed in favorof outright self-assertion, in what one diplomat called Egypt's "pursuitof the Caliphate Grail."107

A P P E N D I X F I VE

THE GENERAL ISLAMICCONGRESS FOR THE CALIPHATE

IN CAIRO

Charter adopted by the preparatory committee of the Congress in itssession of Sunday, Shawwal 12, 1344/April 25, 1926.

Ar t. 1. —The Congress shall be presided over by His Eminence, theShaykh al-Azhar.

Art. 2. —The Congress shall have a vice president, who shall benamed by the administrative committee of the Congress, and who shallcarry out the duties of the president in the event of his absence.

Ar t. 3. —The president of the Congress shall preside over the sessions,give the floor, direct questions, announce the resolutions, and speak inthe name of the Congress.

Art. 4. —The maintenance of order shall be the responsibility of theCongress participants, under the supervision of the president on behalfof the Congress.

Ar t. 5. —The Congress secretariat shall consist of the secretary gen-eral and his assistants, who must know the languages of the participantsin order to make the necessary translations, should circumstances requirethis.

Ar t. 6. —The secretary general shall examine the credentials of thedelegates, in conformity with the invitations issued by the Congress.He shall record their names, and their addresses in Egypt and in theirown countries, in a special register. He shall issue each delegate with apass indicating his name, title, and country.

Art. 7. —The secretariat shall establish the agenda of each of thesessions of the Congress, shall transcribe the proceedings, record the

SOURCE: Sekaly, Le Congri's du KhalifaL 4 2-4 5 .

184

APPENDIXES

resolutions, take attendance, and keep a lis t of those delegates whodesire the floor.

Art. 8. —The secretariat shall edit the proceedings and the resolutionsof the commissions, and submit reports to the president of the Congress.

Ar t. 9. —The president shall open and close the sessions, and set thedate of the next meeting at the close of each session.

Ar t. 10. —Arabic shall be the official language of the Congress. Thosewho do not know it well may speak and comment in their own lan-guages, after the secretariat has translated and distributed their speechesand papers to the other members. As for ordinary remarks, they shallbe translated during the sessions themselves.

Ar t. 11. —The first meeting of the Congress shall be an inauguralsession for the presentation of members. At that time, a commissionshall be named, chosen from among the members, to examine thespeeches, proposals, and papers before they are read to the Congress.This Commission shall submit the results of its examination to theCongress president, indicating which communications may be deliveredto the Congress, and a schedule for their presentation.

Art. 12. —In its second session, the Congress shall examine theagenda, and determine the number of sessions as well as the agenda ofeach session. The Congress may form commissions to study certainquestions, should it so choose.

Ar t. 13. —The commissions shall examine the matters submitted tothem, and each shall separately submit a report containing the resultsof their deliberations. Each commission shall appoint one of its membersas rapporteur, and his report shall be presented to the Congress at apredetermined time.

Ar t. 14. —The president shall transmit proposals and other com-munications received by him to the relevant commissions.

Ar t. 15. —Every member of the Congress has the r ight to speakduring a session, after having requested and obtained the permission ofthe president, on a first-come, first-served basis, following the scheduledspeakers.

A rt . 16. —Remarks shall on ly be addressed to the president o r theCongress assembly.

THE CALIPHATE IN CAIRO 1 8 5

Ar t. 17. —The speaker shall not stray from his subject, repeat some-thing that has already been said, or speak twice on the same subject.

Ar t. 18. —Interruption of the speaker shall not be permitted, exceptto call him to order, which is the prerogative of the president.

Ar t. 19. —The president shall conclude the discussion if no memberdesires the floor to present a new point of view.

Ar t. 20. —Should a group of members request that discussion beclosed, the president shall solicit the advice of the Congress.

Ar t. 21. —Votes shall be conducted by alphabetical roll call.

Ar t. 22. —Resolutions regarding the questions on the agenda andspecific propositions shall be passed by a majority of those memberspresent. In the event of a tie, the president's vote shall be decisive.

Art. 23. —The secretariat, under the supervision of the president,shall count the votes and determine the results, which shall be an-nounced by the president.

Ar t. 24. —The secretariat shall edit the minutes of each session'sdeliberations, and shall read them at the beginning of the followingsession. If there are no objections, the text shall be considered approved.It shall be signed by the president of the session and the secretary generalor his representative, then transcribed in a register and signed again.

Ar t. 25. —The president shall communicate letters and correspond-ence of any importance to the Congress.

Ar t. 26. —The sessions of the Congress shall be public, and admissionshall be by personal pass.

of the Arabian Peninsula and edi tor of al-Qibla, i n a letter to lamal al-Husayni , secretaryof the Arab Executive Committee (Jerusalem), October 11,1922, ISA, division 65, fi le 15.

15. Al-Qibla, July 17,1922.16. Adi b Abu al - D iba (Mecca) to Jamal al -Husayni (Jerusalem), July 18, 1922, ISA,

division 65, fi le 7.17. W . E. Marshal l (Jidda), dispatch of August 30,1922, L/P&S/10/926, P. 4048.18. R. W . Bul lard (Jidda), dispatch of August 29,1923, U P&S/10/926, P. 3841 (E9280/

653/91) .19. R. W . Bul lard (Jidda), dispatch of October 31,1923, U P&S/10/926, P. 4682 (E1151/

653/91) .20. A hosti le but wel l -documented account of the var ious pledges of allegiance offered

to H usayn appears i n al-Manar (July 1924) , 25(5) : 390-400. For a col lection o f similarmaterials, see Oriente Modern° (1924), 4: 226-39. The Meccan al-Qibla for March and Apr i lcarried many professions of allegiance fr om w idely scattered parts.

21. R. W . Bul lard (Jidda), dispatch of Apr i l 30,1924, U P&S/10/1115, P. 2434 (E4379/424/91) . One of the tw o "Javanese" members was a pilgr ims' guide. See R. W . Bul lard,dispatch of M ay 29,1924, U P&S/10/1115, P. 2798 (E5217/424/91) .

22. Oriente Modern° (1924), 4: 2 9 5-9 6 ; a l - Q i b l a , A p r i l 3 , 1 9 2 4 .

23. For the congress and its proceedings, see Oriente Moderno (1924), 4: 600-602; and al-(2ibla for the m onth of July 1924. The text of the charter appears in al-Qibla, July 7,1924.The insistence upon Arabic as the offi cial language did not prevent the use of unoffi ciallanguages at the congress, and al-Qibla, July 17,1924, repor ts that the proceedings weretranslated i nto Turkish, Persian, and Indonesian.

24. Kel l ar El M enouar , Alger ian subject and Gerant du consulat de France (Jidda),dispatch of August 4,1924, AEC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.

25. O n these incidents, see Ar nold Green, The Tunisian Mama, 1 8 7 3-1 9 1 5 , 1 8 5 - 8 7 ; a n d

Nicola Ziadeh, Origins of Nationalism in Tunisia, 98-102. On the opinions current i n Tunisiaon wider Musl im affairs, just before Tha'al ibi ' s depar ture, see B6chir Tl i l i , " Au seuil dunationalisme tunisien. Documents inedi ts sur le panislamisme au Maghreb (1919-1923) ."

26. R. W . Bul lard (Jidda), dispatch of August 30,1924, U P&S/10/1115, P. 3971 (E7907/424/91).

27. Si r Henry Dobbs, Br i tish H igh Commissioner (Baghdad), telegram to Secretary ofState for Colonies, September 24,1924, L/P&S/10/1124, P. 3884.

28. Kawakibi suggested that security in the Hijaz be provided by a mixed mil i tary forceunder the command of the caliph's advisory counci l . Kawakibi , Umm al-oura, 211-12.

29. Si r Henr y Dobbs (Baghdad) , telegram to Secretary of State for Colonies, October26,1924, F0371/10015, E9441/7624/91. W rote Dobbs of Faysal: " I consider that he wi l lprobably receive considerable number of rebuffs. These may enl ighten (him?) more thanany of my arguments can do as to the true atti tude of Moslems in other countr ies towardthe Hashimite fami ly and the Hedjaz question. I trust therefore that I may be given earlyinstructions to inform him that there is no objection to his proposals."

30. O n thi s episode, see M ar t i n Kramer , " Shaykh Maraglu' s M ission t o the Hi jaz,1925.

210 N E W CALIPH IN ARABIA

9. THE CALIPHATE GRAIL

1. For the text of the proclamation, see Majallat al-mzetamar al-islami al-'amm 1P1-khilala bi-Misr (October 1924), no. 1,20-23; Achille Sekaly, Le Congres du Khali/at et le Congres du MondeMusulman, 29-33; and Arnold J. Toynbee, Survey of International Affairs 1925, 1: 5 7 6-7 8 .

2. There exists in ' Abdin Palace an exhaustive list, near ly sixty pages long, of the names

THE CAL I PHATE GRAI L 2 1 1

of al l the members of the pr incipal and branch committees; see MRI, fi l e 761, "Li j an al-khi lafa al- islamiyya bi -M isr ." O n the organization of committees i n Upper Egypt, seeFakhr al-Din al-Ahmadi al-Zawahiri, al-Siyasa wa'l-Azhar, min mudhakkiral Shaykh al-Islamal-Zawahiri, 210.

3. Rashid Rida, "M udhakk i r at mu' tamar al - khi lafa al- islamiyya"; clnayat Al l ah KhanMashriqi, Khitab-i mu'lamar-i khilalat; Sekaly, Congri,s d u K h a l i / a t , 4 - 1 1 , 2 9 - 1 2 2 . F o r c o m p l a i n t s

about the integr i ty of the offi cial proceedings, which are the basis for al l these publ ishedversions, see al-Siyasa, June 21,1926.

4. Toynbee, Survey 1925, 81-91; and also F. Tai l lardat, "Les congres inter islamiques de1926."

5. Zawahir i , al-Siyasa wel-Azhar, 207-17.6. Al-Manar (March 14,1926) , 26(10): 789-91; Shakib Arslan, Sayyid Rashid Ride aw ikha'

arbein sanna, 335 ff.7. El ie Kedour ie, "Egypt and the Cal iphate, 1915- 52," 183- 89,193- 95.8. O n this archive, see M ar ti n Kramer, "Egypt' s Royal Archives, 1922-52."9. These papers had been kept by H usayn W al l , the congress secretary, and wer e

presented to the l ibrary of al -Azhar mosque i n 1967 by one of his nephews. The cor -respondence concerning the fi le i tsel f gives cause to doubt that the col lection is complete.For a prel im inary study of the mater ial, see M ahm ud Sharqawi, "Di rasat watha' i q a nmu' tamar al - khi lafa al- islamiyya 1926."

10. These ideas are discussed by Malcolm H . Ker r , Islamic Reform: The Political and LegalTheories of Muhammad 'Abduh and Rashid Rida, 183-85.

11. M uham m ad Faraj al - M i nyaw i and ' Abd al -Baqi Sur rur Na' im to unnam ed ad-dressee, M ay 20,1924, DWQ, ' Abdi n: al - khi lafa al- islamiyya, uncatalogued box.

12. Majal lat al-mu'lamar (1925), no. 7,167- 68.13. According to the minister, as quoted in al-Manar (May 31,1927) , 28(4): 316. Fur ther

details i n al-Manar (May 2,1927) , 28(2): 156-57.14. Text of Tusun's letter and Zaghlut's reply in al-Mugattam, March 20,1924. On Tusun,

see Gaston W ei t, "Son altesse le Pr ince Omar Toussoun,"15. T he meeting w hi ch ended i n the creation o f thi s committee is descr ibed i n al-

Mugaltam M ar ch 22, 1924. A thor ough account o f A bu al - ' Aza' im ' s campaign, w i thextensive ci tations fr om his personal correspondence, is given by ' Abd al - M un' im M u-hammad Shuqm f, al-Imam Muhammad Madi Abu al- 'Azeim, 219-46. O n his career, see F.de Jong, "M uham m ad Mac

16. See Yusuf al-Dijwi, al-Islam wa-usul al-hukm waTradd 'alayhL17. Handwr i tten Arabic text of manifesto, undated, signator ies Yusuf al -Di jwi , et al.,

in MR1, fi l e 763.18. Detai ls on the investigation i n Ahm ad Shafi q, Hawilyyat Misr al-siyasiyya, 4(3) : 40;

Gail lard (Cairo), dispatch of February 9,1926, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.19. Accor ding to diplomatic sources, Zaghlul , immediately fol l ow i ng the decision o f

the Turks to abol ish the cal iphate, urged Fu'ad to declare himself cal iph, and to use thiscaliphate as a lever against the Br i tish. See H . Gai l lard (Cairo), dispatch of M ar ch 12,1924, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4; H igh Commissioner (Cairo), dispatch of March 29,1924,F0141/587, fi le 545. According to another account, Zaghlul di d no more than ask Fu'adabout his intentions; see Shafi q, Hawliyyal, 4(3): 149-50.

20. Al-Siyasa, September 15,1925.21. Gai l lard (Cairo) to H i gh Commisioner (Beirut) , M ar ch 26, 1926, AFC, car ton 71,

fi le 13/4.22. Text of January 17,1925 decision in Arabic, Turkish, Persian, French, and English,

in Majallat al-mulamar (January 1925), no. 4.23. Al -Manar (March 14,1926) , 26(10): 789-90.

2 1 2 THE CAL I PHATE GRAI L

24. cAbd al-cAzim Rashid (Teheran), dispatch of October 12, 1925, M N , fi le 763. Al lcorrespondence fr om and to ' Abd al-cAzirn is fr om this fi le, unless another reference isgiven.

25. ' Abd al - ' Azim dispatch, November 16, 1925. The dispatch includes the relevantissue of the newspaper, dated November 16, 1925.

26. French translations from the Persian newspapers, i n MRI, fi le 763.27. ' Abd al-cAzim dispatch, M ar ch 16, 1926, DWQ, ' Abdi n: al - khi lafa

uncatalogued box.28. ' Abd al - ' Azim dispatch, January 11, 1926.29. ' Abd al - ' Azim dispatch, February 18, 1926.30. ' Abd al - ' Azim dispatch, March 25, 1926.31. Sir Percy Loraine (Teheran), telegram of March 4, 1926, F0371/11476, E1511/1511/65.32. ' Abd al - ' Azim dispatch, Apr i l 13, 1926.33. ' Abd al - ' Azim dispatch, March 25, 1926.34. cAbd al - ' Azim dispatch, Apr i l 13, 1926.35. Unattr i buted note, n.d., L/P&S/11/261, P. 838 ( in fi le 3125).36. M i nute (author ' s name i l legible), March 5, 1926, F0141/587, fi le 545.37. Taw fi g Nasim (Cairo) to ' Abd al - ' Azim (Teheran), Apr i l 4, 1926.38. ' Abd al - ' Azim dispatch, Apr i l 22, 1926.39. Oriente Moderno (1926), 6: 268.40. ' Abd al-cAziz Ibn Sacud to the Shaykh al -Azhar , December 9, 1925, Azhar File,

document 111.41. O n this attempt, see Kramer, "Shaykh Maraghl 's Mission to the Hi jaz."42. Shawkat ' Al i and Ki fayat Al l ah (Delhi) , telegram to Sad Zaghlul (Cairo), M ar ch

27, 1924, DWQ, Pr ime M inistr y: al - khi lafa al- islamiyya, uncatalogued box.43. Shawkat ' Al i (Al igarh) to Shaykh al -Azhar (Cairo), M ar ch 14, 1924, Azhar File,

document 4.44. Shaw kat ' Al i (Bombay) t o Husayn W al i (Cairo) , January 15, 1925, Azhar Fi le,

document 117.45. Distr ict Commisioner (Jerusalem) to Chief Secretary, August 21, 1925, L/P&S/10/

1155, P. 3908.46. See the note on the visi t, "descr ibed by Police as coming for m a usual ly rel iable

source," i n G. Ll oyd (Cairo), dispatch of October 25, 1925, L/P&S/11/261, P. 3921.47. Tex t of letter fr om Shawkat ' Al i to Abu al- 'Aza' im, i n al-Watan, October 8, 1925.

See also the repor t on a meeting of the committee under Abu al - ' Aza' im i n al-Ak-hbar,October 17, 1925.

48. Al-Liwa al-misri, M ar ch 31, 1926. O n the fai lure of the Azhar organizers to swayHakim Ajm al Khan as wel l , see Arslan (Lausanne) to ' Abbas H i lm i , October 3, 1925,AHP, 118:160.

49. On Mashr igi and the Khaksars, see Shan Muhammad, The Khaksar Movement in India.50. See W i l l iam R. Roff, " Indonesian and M alay Students i n Cairo i n the 1920's."51. On Tjokroaminoto, see Almez, H. O. S. Tjokroaminoto; on the Sarekat Islam, see Deliar

Noer, The Modernist Muslim Movement in Indonesia, 1 9 0 0-1 9 4 2 , 1 0 1 - 5 3 .

52. Crosby (Batavia), " N ote on the Native Movement and on the Political Si tuation inthe Nether lands East Indies General ly," January 3, 1925, F0371/11084, W 1038/156/29,Tjokroaminoto (Jogjakarta) to Husayn Wali (Cairo), January 2, 1925, Azhar File, document78.

53. O n the Muhammadi jah, see Noer , Modernist Muslim Movement, 73-83.54. Java Bode, March 24, 1926, as translated i n Crosby (Batavia), dispatch of March 25,

1926, F0371/11476, E623/1511/65.55. On Hadj i Rasul, see Noer , Modernist Muslim Movement, 37-38. On the delegation and

its role in Cairo, there is an account in Hadj i Rasul's biography by his son, Hamka (Hadj i

THE CALIPHATE GRAIL

102-10; Toynbee, Survey 1925, 5 7 8-8 1 .

2 1 3

Abdul Malik Karim Ammllah), Ajahku, Riwayat hidup Dr. Abd. Karim Amrullah dan perdjuangankaum agama, 91-101.

56. O n M usa Carul lah, see Abdal l ah [Battal - ] Taymas, Musa Carullah Bigi ; Ror l ich,"Transi tion Into the Twentieth Centur y," 58-62.

57. Interview i n Istanbul w i th Musa Carul lah, i n al-Liwe al-misri, M ay 25, 1926.58. Text of letter fr om m uft i to Kal inin, kvestia, M ar ch 18, 1926.59. M usa Carul lah sent a l engthy letter o f protest t o the Azhar committee, w hi ch

apparently is preserved i n Shaykh Zawahir i ' s papers; see Zawahir i , al-Siyasa wel-Azhar,214.

60. See Andr e Raymond, "Tunisiens et Maghrebins au Caire au dix-hui tieme siecle,"and Alber t Hourani , "The Syrians in Egypt in the Eighteenth and N ineteenth Centur ies."

61. Gai l lard (Cairo), dispatch of December 12, 1924, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.62. M inutes of meeting of November 7, 1924, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.63. M ini s tr y (Paris) to Gai l lard (Cairo), January 13, 1925, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.64. Gai l lard (Cairo), dispatch of January 31, 1925, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.65. Gover nor General Steeg (Algiers) to Foreign M inistr y, November 19, 1924, AFC,

carton 71, fi le 13/4.66. ' Abd al -Hamid Ibn Badis (Constantine) to Husayn W al i (Cairo), October 4, 1924,

Azhar File, document 37. On Ibn Badis, see Al i Merad, 1bn Bddis, commentateur du Coran, 23—51. For his atti tude toward the congress, and his demand that Alger ian Muslims participate,see al-Shihab, Apr i l 22, 1926.

67. General Sarrail (Beirut) , dispatch of January 7, 1925, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.68. Gai l lard (Cairo) to Sarrail (Beirut) , February 24, 1925, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.69. Ar s lan (Ber l in) t o Shaykh Faraj al - M i nyaw i (Cairo), November 29, 1924, Azhar

File, document 71; memorandum by Minyawi , January 27, 1926, quoting letter from Arslandated January 6, 1926, Azhar File, document 127.

70. Thi s is impl ied by the sor t o f questions subm i tted i n a letter by the committeechairman Ahm ad Taw fi q al - M adani (Tunis) to Husayn W al i (Cairo), Rabi ' II, 3, 1343,Azhar File, document 48.

71. Letter from Husayn Wali (Cairo) to ' Abd al-Kar im, February 18, 1926, in al-Mugattam,February 20, 1926.

72. Correspondence, translations, i n AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.73. Gai l lard (Cairo), telegram of February 20, 1926, i n AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.74. Gai l lard dispatch of February 22, 1926, AFC car ton 71, fi le 13/4.75. Note verbale, M ar ch 12, 1926, MRI, fi le 763.76. M ar quis de M er r y del Val to Sir W i l l iam Tyrrel l , March 17, 1926, F0371/11920,

W 2249/2249/28.77. Ll oyd (Cairo), dispatch of Apr i l 10, 1926, F0371/11920, W 3227/2449/28.78. R. H. Campbel l to Manuel de Ynclan, Apr i l 28, 1926, F0371/11920, W 3227/2449/

28.79. Foreign M inistr y (Cairo) to Legation (Madr id) , March 28, 1926, MR1, fi le 763.80. Urbain Blanc (Rabat), dispatch of Apr i l 23, 1926, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.81. Ll oyd (Cairo), dispatch of M ay 25, 1926, F0371/11476, E3178/1511/65.82. Gai l lard (Cairo), dispatch of February 28, 1926, AFC, car ton 71, fi le 13/4.83. R ida to Arslan (n.p., n.d.) , i n Arslan, Sayyid Rashid Rida, 367.84. R ida (Cairo) to Arslan, January 1, 1925, i n Arslan, Sayyid Rashid Rida, 352.85. Sekaly, Congrs du Khali/at, 96.86. Cairo C i ty Police repor t of M ay 16, 1926, i n F0141/587, fi le 545.87. T he argument against the possibi l i ty of the cal iphate belonged to that committee

on which the Egyptian presence was negligible. The assumptions of its report were provenlargely accurate. For texts, see al-Manar (August 18, 1926), 27(5): 370-77; Sekaly, Congrisdu Khali/at,

2 1 4

11, 1938, F0371/21838, E1527/1034/65.

10. T H E F AT E OF M EC C A

THE CA L I P HA TE GRAI L

88. For his response to the committee repor t mentioned i n the previous note, see al-Manar (September 7, 1926), 27(6): 449-53; Sekaly, Congres du Khalitat, 110-15. For his logicin pursuing thi s approach, w hi ch essential ly adjour ned the congress, see Zawahir i , al -Siyasa wel-Azhar, 216-17.

89. Al-Siyasa, June 21, 1926.90. Al-Manar (May 13, 1926), 27(2): 143.91. ' Abd al-Rahman 'Azzam (Baghdad), dispatch of Apr i l 10, 1938, MRI, fi le 1243.92. Ibid.93. Foreign M inister to Chief of the Royal D iwan, M ay 5, 1938, MRI, fi l e 1243.94. H is stay i n Egypt is chronicled exhaustively by M uham m ad Hadi al -Daftar , Seta

min rihlat al-imam al-Zanjani wa-khutabuhu fi'l-aqtar al-carabiyya wel-cawasim al-islamiyya, 1: 41—88, 293-488.

95. Ibid., 190-260. In contrast, a Br i tish diplomat at Baghdad w i th w hom the shaykhsometimes confer red found him " an oi l y creature and not at al l tr ustwor thy." V. H ol t(Baghdad) t o J. A . de C. Ham i l ton (Alexandr ia) , June 28, 1938, F0371/22004, J3026/2014/16.

96. Sir Miles Lampson (Cairo), dispatch of March 25, 1938, F0371/21838, E1114/1034/65.

97. For an example fr om Apr i l 1938, see Ahm ad Shafi g, Acmali bacda mudhakkirati, 289.98. Al-Qibla, July 7, 1924, for text of pledge.99. Lampson (Cairo), dispatch of February 17, 1938, F0371/21838, E1114/1034/65.100. Maraghi (Cairo) to Zanjani (Najaf) , February 26, 1938, reproduced by Muhammad

Said Al Thabit, al-Wanda al-islamiyya aw al-tagrib bayna madhahib al-muslimin, 68-71.101. Zanjani (Najaf) to Maraghi (Cairo), Apr i l 9, 1938, i n Thabi t, al-Wanda, 72-76.102. M ar aghi (Cairo) to Zanjani (Najaf) , M ay 3, 1938, i n Thabi t, al-Wanda, 77-79.103. V . H ol t (Baghdad) to J. A. de C. Ham i l ton (Alexandr ia) , June 28, 1938, F 0371/

22004, J3026/2014/16.104. Zanj ani di d appear at a Damascus congress o f ulama later i n 1938. Ther e he

successfully proposed a resolution endorsing cooperation between madhahib, and the con-gress decided to create a committee to consider a more general congress of ulama devotedto the sectarian problem. The Damascus congress, a local affai r , was never reconvened.See Mugarrarat mu'lamar al-culame al-awwal, 14; Oriente Modern° (1938), 18: 552-53.

105. O n thi s i nc ident and the events sur rouding i t , see Kedour ie, " Egy pt and theCal iphate," 204-5; and DWQ, ' Abdi n: al - khi lafa al- islamiyya, uncatalogued box, fi le onthe "supposed oath of al legiance."

106. See Daniel Crecelius, "The Emergence of the Shaykh al -Azhar as the pre-eminentReligious Leader i n Egypt."

107. I n comments on Egyptian aspirations by Sir Percy Loraine (Ankara) to RonaldCampbell, March

1. Sekaly, Le Congres du Khali/at et le Congres du Monde Musulman, 11-25, 125-219.2. See Toynbee, Survey 1925, 308-19. W r i ti ng i n other languages but relying upon the

same sources were Tai l lardat, " Les congres inter islamiques," and Hadsch M ob. N afi 'Tschelebi, "D ie Bmderschaft Arabiens und der islamische Weltkongress zu Mekka 1926."

3. Mater ial related to the Meccan congress was cul led by Shaykh Zawahir i ' s son fromsome papers that remained i n his father ' s possession. Zawahir i , al-Siyasa wa'l-Azhar, 229—63.