Islam and the Baha'i Faith: A Comparative Study of … · 2017-09-26 · 11. Ibn Arabî – Time...

Transcript of Islam and the Baha'i Faith: A Comparative Study of … · 2017-09-26 · 11. Ibn Arabî – Time...

-

200148cacoverv05b.jpg

-

Islam and the Baha i Faith

Muhammad Abduh (18491905) was one of the key thinkers and reformersof modern Islam who has influenced both liberal and fundamentalist Mus-lims today. Abdul-Baha (18441921) was the son of Baha ullah (18171892),the founder of the Baha i Faith; a new religion which began as a messianicmovement in Shii Islam, before it departed from Islam.

Oliver Scharbrodt offers an innovative and radically new perspective on thelives of these two major religious reformers in nineteenth-century MiddleEast by placing both figures into unfamiliar terrain. While one would classifyAbdul-Baha, leader of a messianic movement which claims to depart fromIslam, as an exponent of heresy in Islam, Abduh is perceived as an orthodoxSunni reformer. This book, however, argues against the assumption that bothrepresent two extremely opposite expressions of Islamic religiosity. It showsthat both were influenced by similar intellectual and religious traditions ofIslam and that both participated in the same discussions on the reform ofIslam in the nineteenth century.

Islam and the Baha i Faith provides new insights into the Islamic back-ground of the Baha i Faith and into Abduhs own association with so-calledheretical movements in Islam. This book is a valuable resource to anyoneinterested in the Baha i Faith and its Islamic roots and in the intellectualhistory of modern Islam.

Oliver Scharbrodt is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at WesternKentucky University, USA. His research interests lie in the study of modernIslam and of Iranian Shiism and Sufism.

-

Culture and civilization in the Middle EastGeneral Editor: Ian Richard NettonProfessor of Islamic Studies, University of Exeter

This series studies the Middle East through the twin foci of its diverse cultures andcivilizations. Comprising original monographs as well as scholarly surveys, it coverstopics in the fields of Middle Eastern literature, archaeology, law, history, philosophy,science, folklore, art, architecture and language. While there is a plurality of views, theseries presents serious scholarship in a lucid and stimulating fashion.

PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED BY CURZON

The Origins of Islamic LawThe Qur an, the Muwatta and MadinanAmalYasin Dutton

A Jewish Archive from Old CairoThe history of Cambridge UniversitysGenizah collectionStefan C. Reif

The Formative Period of Twelver Shi ismH. adth as discourse between Qum andBaghdadAndrew J. Newman

Qur an TranslationDiscourse, texture and exegesisHussein Abdul-Raof

Christians in Al-Andalus 7111000Ann Rosemary Christys

Folklore and Folklife in the United ArabEmiratesSayyid Hamid Hurriez

The Formation of HanbalismPiety into powerNimrod Hurvitz

Arabic Literature An OverviewPierre Cachia

Structure and Meaning in MedievalArabic and Persian Lyric PoetryOrient pearlsJulie Scott Meisami

Muslims and Christians in Norman SicilyArabic-speakers and the end of IslamAlexander Metcalfe

Modern Arab HistoriographyHistorical discourse and the nation-stateYoussef Choueiri

The Philosophical Poetics of Alfarabi,Avicenna and AverroesThe Aristotelian receptionSalim Kemal

-

PUBLISHED BY ROUTLEDGE

1. The Epistemology of Ibn KhaldunZaid Ahmad

2. The Hanbali School of Law and IbnTaymiyyahConflict or concilationAbdul Hakim I Al-Matroudi

3. Arabic RhetoricA pragmatic analysisHussein Abdul-Raof

4. Arab Representations of the OccidentEast-West encounters in ArabicfictionRasheed El-Enany

5. God and Humans in Islamic ThoughtAbd al-Jabbar, Ibn Sna andal-GhazalMaha Elkaisy-Friemuth

6. Original IslamMalik and the madhhab of MadinaYasin Dutton

7. Al-Ghazal and the Qur anOne book, many meaningsMartin Whittingham

8. Birth of The Prophet MuhammadDevotional piety in Sunni IslamMarion Holmes Katz

9. Space and Muslim Urban LifeAt the limits of the labyrinth of FezSimon OMeara

10. Islam ScienceThe intellectual career of Nizam al-Din al-NizaburiRobert G. Morrison

11. Ibn Arab Time and CosmologyMohamed Haj Yousef

12. Muslim Women in Law and SocietyAnnotated translation of al-T. ahiral-H. addads Imra tuna fi l-shar cawa l-mujtama c, with an introductionRonak Husni and Daniel L. Newman

13. Islam and the Baha i FaithA comparative study of MuhammadAbduh and Abdul-Baha AbbasOliver Scharbrodt

-

Islam and the Baha i FaithA comparative study of MuhammadAbduh and Abdul-Baha Abbas

Oliver Scharbrodt

-

First published 2008by Routledge2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canadaby Routledge270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informabusiness

2008 Oliver Scharbrodt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted orreproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafterinvented, including photocopying and recording, or in anyinformation storage or retrieval system, without permission inwriting from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication DataScharbrodt, Oliver, 1976

Islam and the Baha i Faith : a comparative study of MuhammadAbduh and Abdul-Baha Abbas / Oliver Scharbrodt.

p. cm.(Culture and civilization in the middle east)Includes bibliographical references and index.1. Bahai FaithRelationsIslam. 2. IslamRelationsBahai

Faith. 3. Islamic renewal. 4. Abdu l-Bah, 18441921.5. Muhammad Abduh, 18491905. I. Title.

BP378.7.S35 2008297.9315dc22 2007041599

ISBN10: 0415774411 (hbk)ISBN10: 0203928571 (ebk)ISBN13: 9780415774413 (hbk)ISBN13: 9780203928578 (ebk)

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledgescollection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

ISBN 0-203-92857-1 Master e-book ISBN

-

To my mother

Le Printemps adorable a perdu son odeur!Baudelaire

-

Contents

Preface xiNote on transliteration and translations xiiiMaps and illustrations xiv

1 Introduction 1

2 The formative years: mysticism and millenarianism 29

3 Into modernity 57

4 Succession and renewal 84

5 Charisma routinised 114

6 Creating orthodoxy: the view of posterity 145

Epilogue 168

Notes 176Bibliography 215Index 233

-

Preface

When I first came across the historical links between Muhammad Abduhand Abdul-Baha Abbas during my graduate studies at SOAS (School ofOriental and African Studies), I was immediately fascinated and excitedabout the idea of investigating further into this unlikely relationship:between the great Sunni reformer of the nineteenth century, one of thefathers of modern Islam, and the leader of a post-Islamic new religionwith origins in Shii messianism. Initially, I planned to undertake researchinto their historical relationship, envisaging myself digging through archives,libraries and private collections in search of correspondence and unknowndocuments. However, I came to realise that such a research agenda wouldnot have warranted a PhD thesis. With the help of my supervisor, Irecognised the potential of a comparative study of both figures and themovements which they headed. It would put them in unfamiliar terrain,connecting the Salafi thinker Abduh with Islamic esotericism andmillenarianism, and Abdul-Baha, as the son of the founder and later leaderof the Baha i Faith, with the gedankenwelt of the nineteenth-century MiddleEast. It would say something about the religious and intellectual roots whichboth figures shared and the similarity and convergence between the Salafisand Baha is, even after they had diverged into different directions. By pro-viding an unusual perspective on Abduh and Abdul-Baha, I hope to saysomething new about the intellectual history of modern Islam, the Islamicroots of the Baha i Faith and the dynamics of Islamic(ate) reform move-ments insights which hopefully contemporary followers of Abduh andAbdul-Baha, Salafis and Baha is, will find challenging and stimulatingas well.

Many people have contributed to the realisation of this book. First andforemost, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Prof. ChristopherShackle, who has been a source of guidance and inspiration while I con-ducted my research. I feel extremely fortunate to have worked with him. Iwould also like to thank Prof. Paul Gifford, the departmental research tutor,for his support and encouragement. Prof. Ian Netton was kind enough toinclude this book in his series on Culture and Civilization in the Middle East.At Routledge, I would like to thank Joe Whiting for his belief in the value of

-

this study and Natalja Mortensen for her assistance during the preparationof the book manuscript.

During one of our many evening discussions over a cup of Turkish coffee,Necati Alkan made me aware of the historical link that exists betweenAbdul-Baha and Muhammad Abduh. This initiated my interest in these twofigures which resulted in this book. Franklin Lewis was the first who sug-gested a comparative study of both figures a piece of advice which I havefollowed and for which I am very grateful. Fiona Missaghian-Moghaddamconvinced me many years ago of the importance of pursuing the academicstudy of religions and became my mentor in my early years as a student. Shehas always reminded me of the ultimate purpose of scholarship.

I wish to express my gratitude to the Haj Mehdi Arjmand Memorial Fundand Iraj Ayman for the financial support without which I could have neverundertaken this research. The University of London Central Research Fundand the SOAS Additional Award for Fieldwork funded my research trips toEgypt and Lebanon in 2003. During my stay in Beirut, Vahid Behmardi tookgreat care of me and provided useful help and support. The staff at thearchives of al-Ahram and of the IDEO in Cairo were very helpful and patientwith my requests.

During the course of this research, a number of people made useful sug-gestions and contributed various ideas to this book. I would like to thankNecati Alkan, Behrooz Bahrami, William Clarence-Smith, Kamran Ekbal,Armin Eschraghi, Khazeh Fananapazir, Adil Khan, William McCants,Moojan Momen, Betsy Omidvaran, Susan Stiles-Maneck, Katja Triplett andBarbara Zollner. Needless to say, all the errors and shortcomings of thisstudy are entirely my own.

I would like to thank my wife Yafa and my son Hadi for their patienceduring the final months of the preparation of the book, when they had toaccept long periods of my absence while I was busy finalising the manuscript.The Shanneik family, in spite of everything else, allowed me time and spacefor the completion of the book in the summer months of 2007. Finally,I would like to express my gratitude to my mother and my stepfather, Dagmarand Karl-Heinz Krner. Although never sharing my fascination with thestudy of Islam, their support and their sacrifices in the first place allowed meto write this book.

Oliver ScharbrodtBowling Green, Kentucky

xii Preface

-

Note on transliterationand translations

This book follows the transliteration system of the International Journal ofMiddle East Studies. Only technical terms and quoted passages in Arabic andPersian have been completely transliterated. For the sake of simplicity, I haverefrained from fully transliterating names (personal, geographical, etc.) andhave chosen a very straightforward way of writing names consisting of geni-tive constructions (e.g. Abdul-Baha, Jamalud-Din, Abdur-Raziq).

Quotations from the Qur an are taken from the recent translation byM. A. S. Abdel-Haleem (The Qur an: A New Translation, Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2004). All other translations in this book are my own.

-

Maps and illustrations

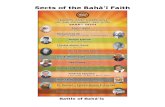

1.1 The Middle East in the late nineteenth century 52.1 Sayyid Jamalud-Din al-Afghani 453.1 Abdul-Baha in Edirne 633.2 Muhammad Abduh in London 705.1 Abdul-Baha 1225.2 Muhammad Abduh 1316.1 Muhammad Rashid Rida 157

-

1 Introduction

In early August 1887, several Beirut newspapers announced the departure ofthe famous Abbas Effendi al-Irani,1 who left the city heading towardsAkka, the former crusader fortress in Palestine. During his stay in Beirut,Abbas Effendi met ulama , notables and government officials who flocked tovisit him spending the whole night talking with him under the moonlight.2

The newspaper announcements are not short of his praise. They describethe impact he had on the people he met during his visit, people who wereimpressed by both his immense knowledge and his extraordinary personality,for he had such good character traits that he had won over the heartsimmediately and made friendship to him an absolute priority.3 AbbasEffendi, more commonly known as Abdul-Baha, had arrived in Beirut in lateJune 1887.4 Not much is known of the purpose of this visit to Beirut apartfrom the constant stream of visitors to him consisting of the great men ofthe city.5 Among the many men he met, one name, however, is known:Muhammad Abduh.

Muhammad Abduh (18491905), the Egyptian-born Muslim reformerexiled to Beirut at that time, had been famed for his opposition to the Britishoccupation of his country in 1882. Together with his mentor and teacherJamalud-Din al-Afghani (183897), he published the anti-British journalAl- Urwa al-Wuthqa (The Firmest Bond ) in Paris, before he settled in Beirutin 1885. One of his students in Beirut, Shakib Arslan (18691946), who laterbecame famous as an Ottoman politician and Arab nationalist, briefly men-tions in his account of Abduhs stay in Beirut the encounter between histeacher and Abdul-Baha which must have taken place some time betweenlate June and early August 1887:

None of the notables or his acquaintances journeyed to Beirut withoutcoming to greet him. He honoured and exalted each one and, even if heconflicted with him in belief, he did not cease to respect him. Foremostamong those he honoured was Abbas Effendi al-Baha, the leader ofBabism (al-babiyya), even though the Babi creed (al-t

arqa al-babiyya) is

different from what the shaykh believes and is the creed (tarqa) that al-

Sayyid Jamalud-Din refuted so strongly. But he revered Abbas Effendis

-

knowledge, refinement, distinction, and high moral standards and AbbasEffendi similarly honoured Abduh.6

Abdul-Baha Abbas Effendi (18441921) was an Ottoman prisoner at thetime of his visit to Beirut. He was the son of the founder of the Baha i Faith,Mirza Husayn Ali Nuri Baha ullah (181792) who was exiled from Iran tothe Ottoman Empire.

Shakib Arslan notes the differences between Abduh and Abdul-Baha interms of their religious beliefs. Abduh, the Sunni scholar and reformer,appears to be miles away theologically from Abdul-Baha, leader of a so-called heretical movement whose founder claims to be a new prophet afterMuhammad. Nevertheless, according to Arslan, the two men held each otherin high esteem. But was their encounter in Beirut just accidental? Was theirgood rapport solely based on the mutual appreciation of their knowledge andcharacters? Was Abduh aware at all of Abdul-Bahas affiliation with theBabis? Or did the two men meet in Beirut because they shared more with eachother than their common mutual admiration? It will be shown that Abduhmet the famous Iranian from Akka at a time when their paths not onlycrossed accidentally, but when their lives and careers were at an importantcrossroad which connected both for a moment but led to the parting of theirways in the future.

Millenarianism and reform in the nineteenth century

Abdul-Baha and Muhammad Abduh belonged to the same generation ofMiddle Easterners who witnessed the demise of the traditional socio-politicalorder within the region and the questioning of traditional Muslim religiosityas preserved by its guardians, the ulama . The two men were not only passiveobservers of the unfolding events but also responded to these changes andtried to influence developments with their own efforts. They lived in a timewhen the intrusion of Western modernity into the Middle East gained anunprecedented momentum. An increasing awareness of the scientific, military,economic and political dominance of Europe initially triggered responsesfrom Middle Eastern rulers to modernise their countries.

The first state which responded to the supremacy of Europe and initiated amodernisation process was the Ottoman Empire. The period of the Tanz

mat

reforms (183976), a series of governmental and legal reforms aiming atmodernising the Ottoman Empire, constituted the beginning of the modern-isation of the Middle East. As the ideological and administrative backbone tothis modernisation policy, the Ottoman sultans sent young diplomats toEurope to build a new Western-educated elite, who would spearhead andformulate the reforms. The Tanz

mat reforms gave the impetus for the mod-

ernisation of Middle Eastern societies and created the intellectual climate forthe acceptance of European ideas and values. The government officials whohad been sent to Europe not only returned with the necessary skills to ensure

2 Introduction

-

the administrative centralisation of the Ottoman Empire but also carriedwith them the ideas of European liberalism with notions of popular sover-eignty, constitutionalism and parliamentary democracy.7 Egypt followed theexample of the Ottoman Empire and sent young, bright men on educationalmissions to Europe and supported the creation of Western-style educationalinstitutions in order to yield a new Western-educated elite for the modernisa-tion of the Middle East.

The ulama experienced the new modernisation drive of the secular rulersas a disruptive force, interfering in their traditional domains of education andlaw, and depriving them of both the economic and the intellectual sources oftheir authority in the long term. In the Ottoman Empire the ulama consti-tuted a kind of aristocratic class closely connected with the bureaucraticapparatus of the government. They provided judges, scribes and other gov-ernment officials and the graduates of their educational institutions had pro-vided the educated elite, governing the country. In the past, secular rulersturned to them for advice and guidance. Now under the new direction of stateadministration, they lent their ears to foreign advisors and bureaucrats withsecular training. The conservative intellectual climate of the madrasa, whichwere completely ignored in the drive to modernise educational institutions,generated ulama who were increasingly hostile to the modernisation oftheir societies. The ulama became an endangered elite and had to realise thattheir education was rendered useless in the new modern state bureaucracy.Whereas the state and the new class of modern bureaucrats constituted agroup open to change and to the adoption of Western ideas and concepts, theintellectual orientation of the ulama was characterised by conservatism andaimed to preserve the status quo.8 Ideologically, reforms were branded as un-Islamic and foreign in origin. However, from a non-ideological perspective,the ulama s opposition to such reforms stemmed from their legitimate fearof losing their traditional authority in the new socio-political orders whichMiddle Eastern rulers were so keen to establish.9

Criticism of the nature of the reforms came also from the agents of thosereforms themselves. An increasing number of Middle Eastern intellectualswho came in contact with European thought grew dissatisfied with the direc-tion of the reforms undertaken by the ruling elites. For them, military andadministrative reforms alone were not sufficient and wider-reaching reformsneeded to be accomplished. The rulers were interested in creating a powerful,centralised state. Their reform initiatives were often intended to consolidatetheir autocratic rule. Economic prosperity was sought through establishingcommercial links with Europe and by inviting European advisors to the coun-try. Both the apparent autocracy of Middle Eastern rulers and their increas-ing foreign dependence alienated a number of intellectuals and members ofthe state bureaucracy who more and more demanded the introduction ofdemocratic reforms and the independence from foreign influence. As the for-eign domination of the Middle East gained further momentum in the latterhalf of the nineteenth century, many intellectuals and bureaucrats assumed a

Introduction 3

-

dissident stance towards the regimes in the Middle East opposing their col-laboration with European powers and their utter absolutism. Political liberal-isation was seen as means of gaining independence from both foreign influenceand indigenous autocratic rule.

Intellectually, these reformers had to formulate a position of dissidenceagainst the Middle Eastern sovereigns, who increasingly turned into localagents of European colonialism, and against conservative forces within thereligious establishment which denounced any engagement with the modernworld as being contrary to the basic tenets of the Islamic tradition. AccusingMiddle Eastern regimes of blindly imitating European ideas and concepts,these reformers felt the need for an intellectual reconciliation of such ideaswith the Islamic tradition. By tracing modern ideas back to Islam, they couldargue against the conservative opposition to them and against the over-reliance of Middle Eastern regimes on the West. The intellectual reconcili-ation of Islam with modernity would show that neither was it necessary tocollaborate with European powers for the implementation of such reformsnor were they in contradiction to Islam.

Who had the intellectual resources for a thorough reconsideration of theIslamic tradition? The mainstream of the ulama was conservative in attitudeand opposed the adoption of Western ideas as part of the modernisationprocess for ideological and non-ideological reasons. As most of the ulama were rather unwilling to engage intellectually with the modern world, theirmonopoly on religious discourse was challenged by a new class of intel-lectuals who, often coming from a traditional religious background, adopteda religious tone to justify the introduction of reforms. Many reformers beganwith a self-reflective analysis of the state of the Muslim world and the reasonsfor its weakness. This self-diagnosis implied a critique of traditional religiousauthority. The ulama were blamed for the demise of Islam in the modernworld because their strict adherence to a medieval and outdated scholarlytradition had led to the intellectual stagnation of Muslims. The nature ofreligious authority was put under scrutiny due to the perceived decline ofIslam attributed to the shortcomings of the religious and political establish-ment. Reformers therefore became both political and religious dissidents andpositioned themselves in opposition to the establishment, asking such ques-tions as: What intellectual traditions of political and religious dissent doesIslam offer? Which alternative models of religious authority allow a creativereinterpretation of the Islamic tradition?

Origins of religio-political dissent in Islamic messianism

Throughout the history of Islam, dissident movements have opposed thereligious and political establishment. In the same manner as religious dissi-dents had challenged the authority of the ulama in the past, nineteenth-century reformers considered traditional Islam as represented by the ulama to have fallen short of responding adequately to the challenges of the modern

4 Introduction

-

Fig

ure

1.1

The

Mid

dle

Eas

t in

the

late

nin

etee

nth

cent

ury.

-

world. As intellectuals and bureaucrats in the nineteenth century who foughtagainst absolutist rule and European colonialism in the Middle East, revo-lutionary movements in Islamic history have combated political regimeswhich were perceived as being corrupt, autocratic and immoral. Very oftensuch movements which attached themselves to notions of religo-politicalauthority were felt to be more authentically Islamic.

Since the revolt of Mukhtar al-Thaqafi (6856) in the name of Muham-mad ibn al-Hanafiyya al-Mahdi (the rightly-guided one), religious and pol-itical dissent in Islam has found one expression in movements around theMahdi, the saviour who would restore Islam and bring true guidance for theMuslim community. The Mahdi, as the divinely appointed charismatic leaderof the community, would initiate a return to the perfection of the propheticage and revive pure and authentic Islam as it existed at the time of theProphet Muhammad. From the time that Mukhtar revolted against theUmayyad caliph and chose a son of Ali ibn Abi Talib as the right leaderof the Muslim community, Mahdis and their messianic movements haveappeared in Islamic history as forces of opposition and dissent against thereligious and political establishment of their times.

Originally, al-Mahdi was a political title designating the rightly-guidedleader of the Muslim community who would restore justice and oppose theillegitimate usurpers to the caliphate as embodied by the Umayyad dynasty.The hope for the arrival of such a leader was particularly strong among theearly Shia which was in its infancy, a political movement in support of theleadership claims of a member of the Hashimid clan, the clan of the ProphetMuhammad. It was believed that the Mahdi by virtue of being part of the ahlal-bayt, the family of the Prophet, partakes of his charisma and thereforewould rule in a similar fashion as the Prophet had. Mukhtars revolt in thename of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya initiated a series of Hashimid revolts inthe name of or led by a member of the clan of the Prophet. The revolt, whichwas eventually successful and which overthrew the Umayyad dynasty, resultedin the Abbasid Revolution of 750. Being descendents of Muhammads pater-nal uncle Abbas and therefore members of the Hashimid clan, the Abbasidsappealed to Shii sentiments of religio-political leadership by a member of thefamily of the Prophet and exploited the notion of a return (dawla) to theprophetic age in their propaganda.10 Once the Abbasids assumed power, theyadopted messianic names like al-Saffah, al-Mansur or al-Mahdi as part oftheir caliphal titles in order to express their charismatic authority.11

Once in power, however, the Abbasids launched severe persecutions againstthe Shia, seeing them as potential sources for political dissent, who mightchallenge the Abbasid rule by putting forward a claimant to the leadershipwho may have been more closely related to the Prophet or even be one of hisdirect descendants. The Abbasids turned to the ulama and patronised theformation and consolidation of Sunni Islam which took shape with the com-pilation of canonical traditions attributed to the Prophet, and the emergenceof Islamic jurisprudence and Islamic theology. The ulama would prove to be

6 Introduction

-

a conservative force rejecting political and religious dissent and acceptingAbbasid supremacy as necessary for the unity and stability of the Islamiccommunity.12

The radicalism of the Shia was also softened after the Abbasid revolution.As previous Hashimid revolts had failed and the apparent vindication of theShia with the success of the Abbasid revolution proved to be disastrous forthem, more quietist and accommodative models of leadership became moreattractive. The descendents of Husayn, the grandson of the Prophet who waskilled by the Umayyads in Karbala in 680, abstained from political actionsand remained quietist. The Husaynid branch of the Hashimid clan, led byMuhammad al-Baqir and Ja far al-Sadiq, and its purely religious and apolit-ical understanding of authority transformed the early Shia from a political toa sectarian movement. For Ja far al-Sadiq, being Imam did not require theactual possession of political power but rather signified the access to a reposi-tory of hidden knowledge which the Imam receives via divine inspiration inorder to act as a channel of divine guidance for his followers.13

Although the members of the Husaynid branch, who would provide theline of Imams of the later Twelver Shia, refrained from political activism, theinitial hope for the rule of the Mahdi was also expressed around them. WhenMuhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya died, some of his followers refused to believethat he had died but assumed that he had gone into occultation (ghayba) andwould return in the immediate future as the Mahdi and rule over the Islamiccommunity. Similar speculations arose after the death of Ja far al-Sadiq andof his son Musa al-Kazim.14 Some of their followers likewise upheld thebelief that they had merely gone into occultation and would return soon toreverse the existing political order. This notion of occultation would proveuseful after the death of the 11th Imam Hasan al- Askari and in the ensuingconfusion about his succession. Most Shia believed that his son went intooccultation and would return in the future as the Mahdi. The adoption of thenotion of occultation by the Twelver Shia had three effects. It ultimatelysuppressed the tradition of religio-political dissent of the early Shia by post-poning both the return of the Mahdi and the establishment of a just andlegitimate Islamic government to the distant future. The eschatological con-notations of the Mahdi also became more pronounced as he would appearshortly before the Day of Judgement. Finally, with the end of the line of theImams, the ulama assumed religious authority and, as their Sunni counter-parts had done before, formed the Twelver Shia as a religious sect by compil-ing traditions attributed to the Imams and developing Shii jurisprudence andtheology. The dissident nature of the early Shia was finally forsaken, henceallowing the Shia to assimilate into the Muslim mainstream.

Shii messianic movements and Sufism

Certain groups within the Shia upheld a dissident stance towards mainstreamIslam and offered alternative models of religious authority which challenged

Introduction 7

-

the religious monopoly of the ulama and which were more inclined towardsindividualised and charismatic forms of leadership as existed with the earlyShia. A more radical offshoot of the Shia, who believed in the transfer of theImamate from Ja far al-Sadiq to his eldest son Ismail, preserved early Shiireligio-political dissidence. While initially believing in the occultation andeventual return of Ismails son Muhammad as Mahdi, leaders of the Ismailislater claimed descent from Muhammad ibn Ismail and announced them-selves to be the promised Mahdi. The messianic claims of Sa id ibn Husayn,who took the name Ubaydullah al-Mahdi in 909, led to the foundation of theFatimid dynasty which challenged the claims of the Abbasids to the caliphatefor almost two centuries. The messianic claims of the leaders of the Nizaribranch of the Ismailis with their headquarters in Alamut in northern Iran inthe eleventh and twelfth centuries were likewise utilised to oppose the existingpolitical order in a militant struggle led by the Imam-Mahdi. Unlike themainstream Shia, which considered the line of the Imams to have terminatedwith the 12th Imam, the Ismailis believed in the continuation of their charis-matic authority and thereby preserved the tradition of religio-political dis-sent of the early Shia. For the Ismailis, there always has to be a single livingpersonification of divine guidance, a proof (h

ujja) of God on earth.15 Ismailism

provided both a political and intellectual alternative for those Muslims dis-content with the Abbasid caliphate and the emerging Sunni traditionalismand disappointed by the quietism the Twelver Shia had adopted. The IsmailiImams offered charismatic and messianic authority that allowed the continu-ation of divine communication with humanity. Furthermore, Ismaili thoughtwas more open towards rationalism and the Greek philosophical heritage andtherefore appealed to Muslim intellectuals who could not identify with thetraditionalist orientations of Sunni and Twelver Shii ulama .16

Although politically less radical, another group also offered an alternativenotion of religious authority a model of religious authority that was alsocharismatic and akin to the religious authority of the Shii Imams. MysticalIslam or Sufism challenged the authority of the ulama and their ratherliteralist and legalist approach to the Qur an offering, similar to the Ismailis,more esoteric readings of scripture that aimed at revealing its hidden mean-ings. The Sufis invested authority in the friends of God (awliya allah), peoplewho were considered to be close to God, and put the Perfect Man (al-insanal-kamil ) on top of a hierarchy of saints. The Perfect Man as the Sufi saintclosest to God would, in imitation of the Prophet and similar to the ShiiImams, act as a mediator between God and humanity and would providedivine guidance, and hence be rightly-guided in a spiritual and intellectualsense.17 Sufism as a religious movement within Islam transcended sectarianboundaries and introduced charismatic authority as an alternative to thescholarly authority of the ulama to both Shia and Sunnis. Sufi notions ofcharismatic authority could be used to express disillusionment with thereligious establishment as embodied by the ulama and implicitly containthe messianic expectation of the human leader, divinely or rationally guided,

8 Introduction

-

who would restore order and justice and establish the ideal rule of theSage.18

The amalgamation of Sufism, Ismaili political activism and Shii messian-ism led to a proliferation of messianic movements in the fourteenth andfifteenth centuries during and after the frail rule of the Ilkhanid dynasty inIran (12561353). One of the earliest was initiated by Fazlullah Astarabadi(d. 1394) who claimed to be not only the Mahdi but also an agent of divinerevelation. While he was initially concerned with extracting the hidden spirit-ual message from the Qur an by employing esoteric interpretative techniquesbased on the letters of the Qur anic text, the persecution of the members ofthe heretical Hurufi sect as they were called led to their politicisation andmilitant activism. The messianic claims of Sayyid Muhammad Nurbakhsh(d. 1463) were of a similar nature. Stemming from the environment of ShiiSufism like Fazlullah, Nurbakhshs claims of being the Mahdi were com-bined with his spiritual identification with prophetic figures of the past likeJesus and Muhammad. Like the Hurufi sect, Nurbakhsh was not primarilyinterested in seizing political power as part of his messianic mission butdevoted much of his time to teaching the mystical path towards God. Aconsciously political and militant expression of Shii messianism was themovement initiated by his contemporary Sayyid Muhammad ibn Falah al-Musha sha (the radiant) (d. 1461 or 1465) who managed to rally the Arabtribes of Southern Iraq in a revolt against the local rule of the TurcomanQaraqoyunlu tribe.19

The mystical-cum-messianic movements, which combined claims to cha-rismatic authority with political activism, provided the background out ofwhich the Safavid Order under the leadership of Ismail managed to conquerIran and to establish the Safavid dynasty.20 Once the Safavids captured powerin Iran, the heretical claims to the charismatic authority of Ismail and thelater shahs of the Safavid dynasty had to be de-emphasised. The Safavidsturn to Twelver Shiism can be understood as a move to routinise their cha-rismatic authority in the transformation of the Safavid Order from a mes-sianic movement to the ruling dynasty. The early Safavid Shahs realised thatthe messianic nature of their religio-political authority was useful in initiatinga revolution but could not provide a stable ideological foundation for theorganisation of a state.21

Despite the suppression of Sufi messianism under the institutionalisedreligion of the ulama , mystical and esoteric strands of Shii Islam couldsurvive in Safavid Iran and found exponents in the School of Isfahan. Theyearning for alternative modes of religio-political authority found expres-sion in the representatives of this theosophical school like Mulla Sadra(15721641). Similar to the Sufis, Mulla Sadra upheld the divine guidance ofthe Perfect Man who had been embodied by the Prophets and Imams in thepast and who could be embodied by anyone who reaches the final stages ofthe mystical journey towards God. Although always placed in the margins ofShii religiosity, the esotericism of the School of Isfahan and its orientation

Introduction 9

-

towards charismatic authority survived in Iran until the nineteenth century.Although theosophists like Mulla Sadra refrained from political activism,their esoteric inclinations kept the Shii tradition of religious dissent alive a dissent that was articulated only intellectually by Mulla Sadra and hisfollowers but that had the potential to erupt in open political dissidence.22

Typology of Islamic messianism

Throughout Islamic history, messianic aspirations have challenged the repre-sentatives of the religious mainstream and offered alternative loci of religio-political authority. Messianic hopes might lie dormant in mystical and esoterictraditions and then suddenly erupt after periods of millenarian anticipationand eschatological speculations. Many messianic movements were militantand launched a jihad to overthrow the existing political order as the Abbasids,Fatimids or Safavids did; other claimants to the Mahdiship saw their missionas apolitical and non-militant, and restricted to spiritual guidance. For theHurufis and the Nurbakhshis, the Mahdi was the supreme mystical guide,devoid of any political pretensions.23

As part of a general typology of Islamic messianism, one can discern notonly different attitudes towards militant struggle but also different objectivesand mandates, in particular between the Sunni and Shii understanding of therole of the Mahdi. Generally, the Mahdi has always been a rather marginalfigure in Sunni Islam. Despite the traditions of his eschatological role thatfound their way into the canonical h

adth collections of Sunni Islam, the

belief in the Mahdi has never played a central role in Sunni creed.24

Central to the messianic mandate of the Sunni Mahdi is his call to a returnto pristine Islam as it existed at the time of the Prophet and his followers. TheSunni Mahdi accepts the finality of Islam and the completeness of thereligious law (shar a) and advocates a stricter adherence to Islam in times of aperceived demise of Islamic religiosity and of an assumed rise in moral laxity.While the Sunni Mahdi agrees with the definition of the religious mainstreamas pronounced by the ulama in theory, he disagrees with the performance ofthe religious establishment which has failed to protect the Islamic tradition.25

His messianic mission is very often connected with the notion of the renewalor the restoration (tajdd ) of Islam and the figure of the centennial renewer(mujaddid ) whom, following a prophetic tradition, God sends to the Muslimcommunity at the beginning of each century. As a consequence, the SunniMahdi demands from his followers a stricter observance of Islamic law sothat they may distinguish themselves from the religious mainstream whichhas failed to live up to religious standards.26

Shii messianism entails a different dynamic. For the Shii Mahdi, as for hisSunni counterpart, the role model of the early community is still valid andthe messianic age he inaugurates re-creates the time of the Prophet. But thereturn to the prophetic age has different implications. Following the Shiiunderstanding of continuous divine guidance under the Imams and the

10 Introduction

-

cumulative nature of this guidance which increases religious knowledge overtime, according to esoteric strands of Shiism in particular, the mandate of theShii Mahdi is less restricted:

His return to the prophetic age of Islam is a return to the age of religiouscreativity, a return to the prophetic paradigm and the model of theImams with the aim of constructing a new religious dispensation.27

The understanding of the mission of the Mahdi as being similar to that ofthe Prophet Muhammad is very often taken to the radical conclusion that,like the Prophet, the Mahdi initiates a new religious dispensation. WhereasTwelver Shiism follows the Sunni conception of the Mahdi as the enforcer ofthe shar a, Ismailis have taken traditions attributed to the Imams stating thatthe Mahdi will come with a new cause to mean that he will abrogate Islamand the shar a and bring a new religion in its stead. Ismaili claimants to theMahdihood gained notoriety for their abrogation of the shar a like Hasanala dhikrih al-salam, leader of the Nizari-Ismailis in Alamut, who in 1164announced the advent of the Day of Judgement and declared Islamic law inconsequence as no longer binding.28 But also outside Ismailism, the potentialclaim to a new religious dispensation was very often realised by leaders ofShii messianic movements, as the examples of the Hurufi and Nurbakhshisects show.

Messianism and religious revival in the nineteenth century

The different types of Islamic messianism reoccurred in the nineteenth cen-tury. The political, economic, social and cultural dislocation the Muslimworld experienced, the occupation by foreign powers and the general feelingthat something had gone wrong in Islamic history created a variety of mes-sianic movements in the Middle East and the wider Muslim world. Many ofthese messianic movements shared a Sufi background in the sense that theclaimant to messianic authority had been affiliated with a Sufi order or ven-erated as a Sufi saint prior to their assertion of being the Mahdi. This obser-vation serves as further evidence of the dormant millenarian potential withinSufism that can erupt under certain circumstances and transform an ordinarySufi saint into the Islamic saviour.29

The Mahdi uprisings of 18815 in Sudan are an example of a militantmessianic movement in a Sunni context. At the time when Egyptian controlover Sudan was weakened, Muhammad Ahmad ibn Abdullah claimed to bethe promised Mahdi in 1881. Both in the person of Muhammad Ahmad andin the movement which he began several of the Sunni features of Islamicmessianism became manifest. The dormant messianism of Sufism can be wellexemplified by him, as Muhammad Ahmad was a Sufi saint who enjoyed theveneration of the local tribal population and then turned into the Mahdi.Following the Sunni mandate of the Mahdi, he saw himself as the restorer or

Introduction 11

-

renewer (mujaddid ) of authentic Islam which had been perverted in his time.His identification with the mujaddid was also facilitated, as he began to raisehis spiritual claims shortly before the beginning of the fourteenth centuryof the Islamic era (which started 12 November 1882). As the mission ofthe Mahdi entails a militant uprising against any illegitimate government,Muhammad Ahmad instigated a jihad against the Egyptians as the embodi-ment of illegitimate and unjust rule in Sudan at that time. The troops ofthe Mahdi managed to conquer Sudan and even resisted the combinedefforts of Egyptian and British armies to suppress them. Shortly before hisdeath in 1885, the Mahdi managed to establish an independent state inSudan.30

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (18351908) is an example of a messianic figurestemming from the environment of South Asian Sufi Islam with an explicitlynon-militant and apolitical understanding of his mission. Born in the villageof Qadiyan in the province of Punjab, he first established himself locally as awell-respected religious scholar before making claims to being the mujaddidor renewer of Islam on the eve of the fourteenth century of the Islamic era.Ghulam Ahmad felt that he was the one to assume this role in his time whenthe ulama had failed to preserve the integrity and authenticity of Islam,when the Islamic community had reached an unprecedented level of corrup-tion, and Muslim lands were occupied by Christians whose missionariesthreatened the very survival of the Islamic community. For Ghulam Ahmad,being the centennial renewer of Islam implied holding a special spiritualstatus as well. Not only was he the promised Mahdi but also a new prophetwho received divine revelations to purify Islam and return to the model of theearly community.31 The notion of a return to pristine Islam as part of itscentennial renewal and the perception of the Mahdi re-enacting the missionof the Prophet were radicalised by Ghulam Ahmad in his claims to be aminor prophet after Muhammad. The controversial nature of such a claim isobvious, given the fundamental Muslim belief in the finality of Muhammadsprophethood. Ghulam Ahmads claims show that messianic authority canarise out of opposition to the perceived failure of the traditional holders ofreligious authority and can implicitly if not explicitly challenge fundamentalMuslim doctrines.

The Babi and Baha i movements are examples of two historically linkedmessianic movements with a Shii background. Their origins and evolutionswill be described in greater detail later. Muhammad Ahmad in Sudan, GhulamAhmad in India, the Bab and Baha ullah in Iran are each nineteenth cen-tury manifestations of the different types of Islamic messianism. WhileMuhammad Ahmad and the Bab conceived their mission as being of a mili-tant nature, Ghulam Ahmad and Baha ullah considered themselves to bemerely spiritual Mahdis providing religious guidance for their followers.More importantly, they all also give evidence of the different dynamics ofmessianism in Shii and Sunni Islam. While the Sudanese Mahdi and GhulamAhmad intended to restore pristine Islam, for the Bab and Baha ullah their

12 Introduction

-

messianic mission meant the abrogation of Islam and the beginning of a newreligious dispensation.

Hence, traditions of religio-political dissent in esoteric, mystical and mil-lenarian strands of Islam also re-emerged in the nineteenth century. The Babiand Baha i movements in Iran and the Ottoman Empire, the Mahdi uprisingsin Sudan and the Ahmadiyya in South Asia are just some examples ofhow dissident traditions preserved in Sufism and Shiism can suddenly leadto messianic eruptions. But how and why are these modern expressionsof religious dissidence in Islam relevant for those government officials, bur-eaucrats, intellectuals and modernist religious scholars who laboured forthe reform of Islam and the modernisation of Middle Eastern societies?Bureaucrats and intellectuals on the one side, Mahdis and prophets on theother side responded in their own ways to the emergence of Western modern-ity in the nineteenth-century Middle East. What they all shared is a dissidentstance towards the religious and political establishment and a yearning foran alternative vision of Islam created by new forms of religious authority.Muslim reformers like Muhammad Abduh shared with contemporary mes-sianic movements like the Baha i movement their origins in the mystical andesoteric traditions of Islam which provided them with the intellectual meansto position themselves, like the Mahdis and their followers, in oppositionto political regimes in the Middle East and the upholders of the Islamictradition, the ulama . It has been shown that many of the most promi-nent reformers in the nineteenth-century Middle East were associated withmovements of a mystical or millenarian nature.32

Charisma and its routinisation

This study is an exercise in the analysis of religious change focusing particu-larly on transformations of religious authority in the context of nineteenth-century Middle Eastern reform movements. In their opposition to the religiousestablishment, Abdul-Baha and Muhammad Abduh embodied or attachedthemselves to alternative loci of religious authority which were endowed withcharismata as represented by mystical and millenarian strands of Muslimthought. However, later they had to reconcile their origins in religious dissi-dence in order to perpetuate their legacies for posterity.

Max Webers studies on the nature of charismatic authority and its routin-isation are used to describe the evolution of Abdul-Baha and Abduh asIslamicate religious reformers who shared common origins in mystical andmillenarian traditions of Islam and who, at later stages of their careers asreligious leaders, offered contradictory responses to the perceived decline oftraditional Islam. One starting point in Webers sociology of religion is theideal-typical contrast between priest and prophet. Weber assumes the inher-ent ritualism and traditionalism of religion: das Heilige ist das spezifischUnvernderliche33 (the sacred is the specifically unchangeable). The pastnessof the sacred is illustrated by the scrupulous repetition of rituals and the

Introduction 13

-

canonisation and dogmatisation of religious beliefs that occur during theestablishment of religious institutions. For Weber, clearly defined rituals, acanonical set of sacred scriptures, and a hierarchy of institutions overseeingthe adherence to both are part of the stereotyping tendencies of religionswhich act to prevent change and to preserve the tradition. The church is theinstitutional embodiment of this attitude and the priest the holder of author-ity within the church due to his association with a sacred tradition. As areligious functionary of the church, the priest officiates at its rituals andensures that their proper performance is effective in connecting lay followerswith the sacred. The priest is socialised within an educational tradition ensur-ing his proper instruction into the canonical beliefs of the church and enablinghim to preserve their authenticity.34 The church thereby offers its lay followerspermanence35 as an institution that has become daily routine36.

Weber positions the ideal type of the prophet as opposite to the priest. Theprophet is understood as a purely individual bearer of charisma, who byvirtue of his mission proclaims a religious doctrine or divine commandment37:

The personal call is the decisive element distinguishing the prophet fromthe priest. The latter lays claim to authority by virtue of his service in asacred tradition, while the prophets claim is based on personal revelationand charisma.38

Charismatic authority stands outside daily routine, is of an extraordinarynature and is strongly personalised. The person endowed with charismaticauthority displays qualities which deviate from ordinary behaviour and pro-vide him with a special status distinguishing him from ordinary people. In thecase of the prophet, his proximity to God and his election as transmitterof divine revelations constitute his supra-natural, not commonly accessibleauthority. Weber realises not only the predominance of charismatic authorityin times of social, economic, political or religious crisis39 but also its revo-lutionary character. The legalistic order of the church personified by thepriest establishes rules and norms to preserve tradition and the sacredness ofthe past. It is inclined towards permanence and routine. Charisma disruptsthe rules and norms of tradition, turns everything that is held sacred upsidedown, and demands the submission to the absolute novel and innovative. ForWeber, charismatic authority is die spezifisch schpferische revolutionreMacht der Geschichte40 (the specifically creative revolutionary force of his-tory). The prophet exhibits religious charisma and stands outside the churchtradition. For Weber, charisma religiously speaking is heretical: it makes asovereign break with all traditional or rational norms: It is written, but I sayunto you. 41

Weber acknowledges not only the revolutionary character of charismaticauthority but also its inherent instability. The holder of charismatic authorityconstantly needs to prove his legitimacy by revealing proofs of his charismaticelection. A prophet needs to provide a constant stream of revelations so as to

14 Introduction

-

manifest his special relationship with God.42 The instability of charismaticauthority becomes particularly manifest when its holder dies. If the sectariancommunity which has emerged as the result of the charisma of its founderwishes to continue its communal bond, it needs to enter a process that Webercalls the routinisation of charisma. The charismatic authority of the founderneeds to be traditionalised and rationalised in the formation of a religiousorganisation like a church. While initially the religious movement wassectarian in character, as it seceded from the church, it, now, turns itself into anew church organisation. In the new church the exceptional charismaticauthority of its founding figure becomes routinised with the establishmentof an organisational hierarchy, the rules and norms of a religious traditionand a conceptualisation of authority based on membership in the hierarchyand adherence to the rules and norms of the tradition.43 The originally revo-lutionary and innovative and, for Weber, heretical nature of charismatic auth-ority and of the sectarian movement it initiated thereby becomes orthodox.

One of the problems of Webers typology is its obvious ideal-typicalcharacter based on dichotomies like priest and prophet, church and sect,orthodox and heterodox, tradition and charisma. Webers distinction betweencharisma and its routinisation assumes a dichotomy between church and sectbut also links them to each other in an organic development, accordingto Peter L. Berger. Whereas a sect stresses charismatic leadership and theimmediacy of the spirit, this charisma is secularised in the process of itsroutinisation when the sect assumes a systematic structure and becomes achurch. Then, the spirit becomes profane and the sacred is encapsulated in asecular organisation.44 As the transformation of a sect into a church illus-trates, the assumed dichotomy between orthodoxy and heterodoxy is ratherartificial and, as this study will illustrate, ultimately not very useful in explain-ing how a dissident movement positions itself towards the religious traditionout of which it has emerged. The relationship between the religious main-stream and a charismatic eruption within it can oscillate between being con-frontational and symbiotic. Dissident movements have been embraced withvariable success in order to alleviate their opposition to the religious estab-lishment. The Christian concept of ecclesiola in ecclesia and the Islamicnotion of ikhtilaf al-madhahib intend to define the religious mainstream inthe broadest possible sense in order to appease and to embrace possibledissidents.45

The need of a religious tradition to redefine itself particularly arises whenits established institutions become vulnerable and fail to provide identityand security for the members of its community. In such a crisis milieu although not only then charismatic movements challenge the authorityof the religious mainstream. However, such dissident movements, whichsecede from the religious establishment by addressing its failure to provideidentity and security, do not necessarily constitute a counter-model of thereligious mainstream but rather cherish the very values which the tradition issupposed to uphold. Charismatic movements attempt to realise values which

Introduction 15

Book CoverTitleCopyrightContentsPrefaceNote on transliteration and translationsMaps and illustrations1 Introduction2 The formative years: Mysticism and millenarianism3 Into modernity4 Succession and renewal5 Charisma routinised6 Creating orthodoxy: The view of posterityEpilogueNotesBibliographyIndex