Inter-modal network externalities: Complementarities between roads,...

Transcript of Inter-modal network externalities: Complementarities between roads,...

Inter-modal network externalities: Complementarities between roads,

canals, and ports in Britain, 1760-1830

Dan Bogart1 Department of Economics, UC Irvine

3151 Social Science Plaza Irvine CA 92697-5100

Abstract How does the expansion of one transport mode influence the expansion of another transport mode? This paper examines whether inter-model network externalities influenced the development of roads, canals, and port infrastructure in Britain from 1760 to 1830. It uses data on all acts of Parliament approving road, canal, and harbor improvements to test whether there was an inter-connection between road, canal, and harbor development. The results indicate that road projects had a positive spillover effect on canal development, but not vice versa. Harbor development also influenced canals but to a lesser extent.

Keywords: transport modes; network externalities; decentralization; British transport

1 I would like to thank David Levinson and Gary Richardson for providing helpful comments on earlier drafts. I would also like to thank Patricia Suzuki for providing valuable research assistance.

1

Transport networks consist of many infrastructure modes like roads, rivers, canals,

railroads, airports, and seaports. The different modes can be complementary because

some goods move through the network via road, water, rail, and air. For example, goods

might enter through a port before being shipped by road, water or rail to a market. If the

port is too small then goods will have difficulties reaching road, rail, and canal networks,

and thus these latter modes will be less valuable to users. Similarly, if road, canal, or rail

networks are underdeveloped, then the port will be less valuable to users as well.

Different infrastructure modes can also be complementary because of specialization.

Congestion can occur when passengers and freight share the same mode or when light,

high-value freight share the same mode as heavy, low-value freight. An expansion in

road or airport networks might reduce congestion on water or rail networks because

passengers or light, high-value freight would then shift to roads or air. Similarly an

expansion in water or rail networks might reduce congestion on roads and in the air.

In theory inter-modal externalities influence the private and social value of transport

networks; however, in practice it is not clear they have a substantive impact on valuation

when compared with ‘fundamental’ demand factors like, higher economic growth or

lower interest rates. Furthermore, it is not clear that spillovers are symmetric across

modes. For example, it is possible that canals raise the value of roads and railroads more

than the other way around.

In this paper, I use history to examine the influence of inter-modal network

externalities on infrastructure development. Specifically, I study this issue in the context

road, canal, and harbor development in Britain from 1760 to 1830. Before the arrival of

railways, Britain had one of the most extensive transport networks in the world. Its

2

turnpike roads, rivers, and canals connected major cities with one another as well as with

agricultural hinterlands and natural resources, like coal and iron. Britain’s coastline was

also well-served by harbors, where ships of all sizes could unload food and coal before

reloading cotton textiles and iron wares for export.

Most of the roads, harbors, and canals were built or improved in the mid-eighteenth

and early nineteenth centuries. Each road, harbor, and canal project was authorized

through an act of Parliament, which granted rights-of-way, the authority to collect tolls,

and authority to issue bonds secured on the income from tolls. The acts were initiated by

proposals from local individuals, cities, or county officials and were approved and

modified by Parliament. The transport system thus emerged through a mixture of

decentralization, centralization, and private participation.

I use time-series data on the number of road, canal, and harbor improvement acts in

each year to identify whether inter-modal externalities had a substantive impact on road,

canal, and harbor development. Acts provide a measure of the number of road, canal,

and harbor projects approved by Parliament. My assumption is that local groups

proposed road, canal, and harbor acts whenever their expected economic benefits

exceeded their expected costs. If there were inter-modal externalities, then the expected

economic benefits of a canal improvement act should be higher when more road and

harbor improvements are approved. The same relationship may hold from canals and

harbors to roads as well as from canals and roads to harbors.

I first establish the correlation between differences in road, canal, and harbor acts (i.e.

the difference in acts passed between t and t-1). The data show a positive correlation

between the difference in road acts in year t and the difference in canal acts in year t.

3

There is also a positive correlation between the difference in canals acts in t and the

difference in roads acts in t-1 as well as the difference in harbor acts in t-1.

The correlations suggest there may have been spillovers from road and harbor

improvements to canal improvements. I explore this hypothesis further by specifying an

econometric model that relates differences in canal acts in year t with differences in road,

harbor, and canal acts in year t-1, along with differences in interest rates, the growth of

industrial production in t-1, and dummies for war years. The results show that increases

in roads and harbor acts are associated with increases in canal acts, but only the variable

for roads acts is statistically significant.

I also address endogeneity by performing a two-stage least squares estimation. In one

specification, I use political variables, like election years and years with new prime

ministers as instruments for differences in road acts. In a second specification, I also use

lagged differences in interest rates, the growth of industrial production, and war dummies

as additional instruments. The two-stage least squares results still show that increases in

road acts are associated with increases in canal acts, but the effect is only statistically

significant when all instruments are included. These results suggest there is reasonably

strong evidence that road projects had a positive spillover effect on canals.

The findings have implications for the literature on the development of the British

transport network. Canals are often regarded as the most important transportation

improvement of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (see Duckham, 1983 for an

overview). The results here suggest that road improvements were also important because

they complemented canal improvements as well as aiding in the expansion of road

transport services.

4

The results also have implications for contemporary policy-making. The initiative

for and the planning of British transport improvements was decentralized, and as a result

some canal projects might have been delayed by the slow development of road projects

with significant spillovers. In such cases, it would appear that policy-makers can

encourage the development of transport networks by helping to coordinate, or perhaps

subsidize, certain projects.

The paper is organized as follows. The first section provides background on roads,

harbors, and canals in Britain. The second section introduces the data. The third section

presents the econometric analysis. The fourth section concludes.

I. Background on British roads, harbors, and canals

In eighteenth century Britain, most large-scale transport improvements required an

act of Parliament. Common law and statutory law dating from the 1500s dictated that

local inhabitants were required to provide for the maintenance of nearby roads, rivers,

and harbors, but they were not required to improve them. Even if one wanted to build a

new road, canal, or harbor it would have been difficult without first obtaining rights-of-

way. The easiest way to obtain rights-of-way was through an act of Parliament. In the

eighteenth century, acts could be very specific by giving a group of individuals, a city, or

a company the right to improve a particular road, canal, or harbor. Improvements might

include new construction, the diversion or widening of an exiting route, or simply better

maintenance. Acts were also crucial because they gave individuals, cities, and

companies’ rights to levy tolls and issue bonds secured by the income from the tolls. The

tolls and bonds provided the financial sources which paid for most projects. The tolls

5

were particularly important for roads because they allowed local communities to shift

part of the tax burden to through-travelers (see Levinson, 2002).

Throughout the 1700s and early 1800s Parliament passed literally thousands of acts

dealing with local infrastructure (Innes 1998). Interestingly very few of these acts were

initiated by the ministry or Parliament. Instead local individuals and officials initiated

acts with petitions submitted to Parliament. For example, in 1742, the Justices of Peace,

gentlemen, and other persons living near the road between Harlow and Great Chesterford

submitted the following petition stating the need for an act to improve their road:

The aforesaid road about 25 miles in length, is by reason of the deepness of the soil and many heavy carriages passing through it, become very ruinous and in the winter many parts are almost impassable for wagons and carriages, and also for horses laden; and other parts are dangerous to travelers, and the roads cannot by ordinary course appointed laws and statutes be effectually amended without the aid of an act of parliament2 The preceding petition resulted in the passage of an act “for repairing and widening”

the road between Harlow and Great Chesterford in the same year of 1742.3 The act

named the several individuals living near the road as trustees and gave them authority to

levy tolls, purchase land for road widening, and issue bonds secured by the tolls. Such

acts are sometimes referred to as ‘turnpike acts,’ because they authorized the erection of a

gate for collecting tolls. A similar procedure was used for canal and harbor acts with

local individuals, cities, and county officials providing the impetus for improvement, and

Parliament modifying and approving projects.

This decentralized process for proposing projects had implications for the

development of the British transport network. On the one hand, it may have promoted

efficient infrastructure investment because locals had more information about which 2 This passage came from the Journals of the House of Commons, 8.12.1743. 3 Ibid. 23.2.1743.

6

projects should be implemented, and the reliance on local revenue sources prevented the

financing of unnecessary projects. On the other hand, decentralization could have

promoted inefficient investment because locals did consider whether their project raised

the value of other projects, or whether it provided information about the value of other

projects. There is some evidence that network and neighbor effects operated within

transport modes. For example, it appears that some communities delayed their road

improvements until other communities improved contiguous roads (Bogart, 2007). It is

not clear, however, whether spillovers exited between infrastructure modes, like roads,

canals, and harbors.

Many historians of British transport emphasize the complementarities between roads,

canals, and coastal transport rather than competition between the modes. For example,

Baron Duckham (1983, p. 132) suggests that ports, like Liverpool, were spurred by the

development of canals in their hinterland and even further away. John Armstrong and

Philip Bagwell (1983, p. 161) argue that in many ports, coastal ships “fed the river barges

and canal boats with traffic and in return were fed by them.”

Eric Pawson (1977) also argues that developments in land and water transport were

inter-dependent; noting that many turnpike roads were connected with river ports (p.

164). Pawson also suggests, however, that economic growth and speculation provided a

foundation for both canal and road improvements in the 1790s (p. 129). Pawson’s last

point raises an alternative hypothesis, namely that road, canal, and harbor developed in

tandem because economic growth and financial development increased the demand for

all three infrastructure modes. In the following sections, I use data on road, canal, and

harbor improvement acts to investigate whether inter-modal network externalities

7

influenced the development of roads, canals, and harbors, after controlling for economic

growth and financial development.

II. Data

This section provides an overview of the data on road, canal, and harbor improvement

acts as well as economic and political data on Britain. The Parliamentary Archives in

London maintains a database, Portcullis, which provides the title of every act starting in

1500. I use Portcullis to identify every act dealing with specific road, canal, and harbor

improvements between 1760 and 1830. The data is particularly useful because it

identifies the location and the year when every road, river, and canal project was

approved by Parliament.

There were two main types of road, canal, and harbor acts. The first type created a

new statutory authority with rights to improve or construct a road, canal, or harbor. For

example, an act in 1790 created a new authority for “making and maintaining a navigable

Canal from Merthyr Tidvile to and through a Place called The Bank, near the Town of

Cardiff in the County of Glamorgan.”4 Another act in 1769 created an authority for

“repairing, improving and better preserving of the Harbour and Quay of Wells, in the

County of Norfolk.”5 Yet another act in 1787 was “for amending, widening and keeping

in Repair the Road leading from the Town of Nottingham to the Town of Mansfield, in

the County of Nottingham.”6

The second main type of act amended rights granted in a previous act. Some

amendment acts renewed or enlarged the powers of existing statutory authorities.

4 See Portcullis HL/PO/PU/1/1790/30G3n118 5 Ibid. HL/PO/PU/1/1769/9G3n9 6 Ibid. HL/PO/PU/1/1787/27G3n32

8

Renewals were most common in road acts which granted rights to levy tolls for 21 years

at a time. When the term was set to expire, road authorities usually petitioned for a new

act granting another term of 21 years, but did not necessary propose additional

improvements. Other amendment acts included new projects that were to be undertaken

by the same statutory authority. For example, an act in 1824 was passed “to abridge,

vary, extend and improve the Bristol and Taunton Canal Navigation, and to alter the

Powers of an Act of the Fifty-first Year of His late Majesty for making the said Canal.”7

In this particular case, the rights of the Bristol and Taunton canal company were amended

so that they could improve and extend the canal.

The variety of acts presents a challenge for my analysis because not all road, canal,

and harbor acts marked the approval of a new improvement project. For roads, I use

William Albert’s (1972) series of acts that initiated turnpike authorities on roads that

were not previously under their control. Albert’s series has been used by many economic

historians and is generally regarded as a close approximation for all road acts that

authorized new improvements. I use the Portcullis data to create a similar series of canal

improvement acts by combining all acts for making canals with amendment acts that

authorized extensions, branches, or variations of the canal route. I also combine all acts

that authorized construction, repairs, or extensions to quays, docks, piers or any other

work related to harbors. Together the data consist of an annual time-series on all road,

canal, and harbor improvement acts between 1760 and 1830.

I also incorporate other variables that proxy for factors affecting the costs and

benefits of road, canal, and harbor improvements. Interest rates are likely to influence

the costs of financing road, canal, and harbor improvements because they all entailed 7 Ibid. HL/PO/PB/1/1824/5G4n221

9

large up-front investments in materials and structures. Interest rates are measured using

the real yield on long-term government bonds, known as 2 1/2% consols. Bond yields

come from the Global Financial Database and are available on an annual basis from 1760

to 1830. For the inflation rate, I use a three-year moving average of the percentage

change in Greg Clark’s (2001) consumer price index.

Real G.D.P. growth is likely to influence the benefits of road, canal, and harbor

improvements by increasing the revenues for these projects. Unfortunately, there is no

widely-accepted time-series on annual British G.D.P. growth between 1760 and 1830.

Instead, I use Crafts and Harley’s (1992) estimates of the annual growth rate for

industrial production. Manufacturing was the most dynamic sector in the British

economy and thus the growth rate of industrial production represents a key component of

G.D.P. growth. Warfare is another factor that is likely to affect the benefits of roads,

rivers, and canals because it changed domestic and international trade patterns. The

general histories by Holmes and Szechi (1993) and Evans (2001) provide all years when

Britain was at war. I also use these works to identify election years and years when a

new prime minister took office.

III. Analysis of Inter-modal Network Externalities

In this section, I analyze whether inter-modal network externalities influenced the

development of roads, canals, and harbors in Britain. It is useful to begin by examining

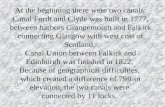

the time-series patterns for road, canal, and harbor improvement acts (see Figure 1). The

number of road improvement acts ranged between 0 and 30 and were highest in the

1760s, 1790s and 1820s. The number of canal improvement acts ranged between 0 and

10

22 and were highest in the 1790s. Harbor improvement acts ranged between 0 and 7 and

were highest in the 1800s and 1820s. The correlation between road and harbor acts is

close to zero, but there is a positive relationship between canal acts and roads acts

(ρ=0.15) and between canal acts and harbor acts (ρ=0.20). There is also a positive

relationship between the difference in canal acts between year t and t-1 and the difference

in road acts between year t and t-1 (ρ=0.18). There is a smaller relationship, however,

between differences in canal acts between year t and t-1 and differences in harbor acts

between t and t-1 (ρ=0.03).

The following analysis focuses on the relationship between differences in the number

of road, canal, and harbor improvement acts in year t rather than the number of road,

canal, and harbor improvement acts in year t. A positive correlation between the

difference in canal acts and the difference in road acts implies that yearly increases

(decreases) in canal acts are associated with yearly increases (decreases) in road acts,

while a positive correlation between the levels implies that more (less) canal acts in a

year are associated with more (less) road acts in a year. In other words, the differences

capture the short-run relationship, while the levels capture the long-run relationship. I

examine differences rather than levels in order to lessen concerns that the time-series are

non-stationary. Moreover, a short-run correlation implies the long-run correlation, but

not necessarily the other way around. I also focus on the relationship between

contemporaneous and lagged differences in acts because simultaneity makes it difficult to

determine whether increases in roads in year t caused increases in canals in year t, or vice

versa.

11

Table 1 shows the correlations between lagged and contemporaneous differences in

road, canal, and harbor acts. The strongest correlations are between the difference in

canals acts in year t and the difference in road and harbor acts in t-1 (see column 3).

There is also some positive relationship between differences in road acts in t and harbor

acts in t-1, but it is not very strong. Differences in harbor acts appear to be unrelated to

lagged differences in road and canal acts.

Overall the correlations suggest that road and harbor improvements may have had a

positive spillover effect on canal projects. To investigate this possibility further, I

examine the following econometric model explaining differences in canal improvement

acts in year t:

ttttttt warxcanalharborroadcanal εδγλβα +∆++∆+∆+∆=∆ −−−− 1111 (1)

The variables 1−∆ troad and 1−∆ tharbor are the difference in road and harbor

improvement acts in year t-1. If there were inter-modal network externalities, then an

increase in road or harbor acts in t-1 should increase canal acts in t. 1−∆ tcanal is the

difference in canal improvement acts in year t-1. I include this variable because an

increase in canal improvement acts in the preceding year may reduce the number of

profitable projects in the current year.

1−tx includes a constant, the growth rate of industrial production in t-1, and the

difference in the real yield on govt. bonds in t-1. A higher growth rate in industrial

production should lead to an increase in canal improvement acts, while an increase in the

yield on government bonds should lead to a decrease in canal acts. twar∆ is the

12

difference in a dummy for war years between year t and t-1. One hypothesis is that war

lowered the costs of passing canal acts, because Members of Parliament recognized the

need for inland transport during times of international conflict. If the cost of passing

canal acts were indeed lower in times of war, then there should be a positive sign on

twar∆ because canal acts should increase when wars were initiated and they should

decrease when wars ended.

Table 2 reports the regression estimates of equation (1). The main finding is that

differences in road acts in t-1 have a positive and statistically significant effect on the

difference in canals acts in t. This provides some initial evidence that road improvements

had a positive spillover effect on canals. Differences in harbor improvement acts in t-1

are also positively related to differences in canal acts in t, but the coefficient is not

statistically significant. The results also show a positive relationship between canal

differences and a higher growth rate of industrial production, as well as a negative

relationship between canal differences and increases in the real yield on government

bonds. Neither of these variables are statistically significant however. Lastly there is a

positive and significant relationship between wars and canal development. The onset of a

war appears to have increased canal acts while the end of a war decreased canal acts.

Although the regression shows a positive and significant effect from differences in

road acts in t-1, it is possible that the coefficient is biased because of measurement error

or omitted variables. Measurement error could arise because some road acts dealt with

large and important roads, while others did not. If large and important roads had greater

spillover effects then the same difference in roads acts may capture high spillovers in

some years and low spillovers in other years. It is not easy to identify the bias from

13

measurement error, but if the difference between the observed variable and its true value

has a mean of zero and positive variance, then we know that the coefficient estimate will

be biased downwards (see Wooldrige, 2002). In our case, that would imply that the

coefficient on 1−∆ troad in table 2 understates the spillovers from roads to canals.

Omitted variables could also bias the estimate of spillovers from roads to canals

because it is difficult to measure all factors which are related to both canal and road acts.

One possibility is that greater optimism about future economic growth increased both

road and canal acts. For example, recall Pawson’s (1977, p. 129) argument that

speculative financiers helped to spur the development of canals and roads in the 1790s. If

this were the case, then there would be a positive correlation between road differences in

t-1 and the error term in equation (1), and the estimates of spillovers from road to canals

would be biased upwards.

In principle, measurement error and omitted variables problems can be addressed

through two-stage least squares, but it is difficult to find an instrumental variable that is

correlated with differences in road acts in t-1, but uncorrelated with the error term in t. I

propose to use dummies for election years and dummies for years in which there was a

new prime minister as instruments. Elections occurred every 7 years, and thus their

timing was exogenous. Elections could influence road acts by either raising or lowering

the cost of passing acts. One possibility is that Members of Parliament devoted less time

to passing roads acts in election years because they were busy with their campaign.

Another is that Members were less likely to engage in logrolling around elections. These

hypotheses suggest that dummy variables for election years might be suitable instruments

for differences in road acts in t-1. Specifically, I use a dummy variable if year t was an

14

election year and another dummy if it preceded an election year. The only potential

problem is that elections may have affected canal acts as well. Thus I need to make an

assumption that elections affected road acts and not canal acts.

The arrival of a new prime minister may have also affected the costs of passing road

acts because new prime ministers would want to increase their support by encouraging

legislation with local benefits for Members of Parliament. Road acts shared some

features of ‘pork-barrel’ legislation. They targeted a specific constituency and were

valued by Members of Parliament. By contrast, canal acts generally affected a larger area

and so they were not as useful to Prime Ministers who were trying to target the benefits

of legislation to the constituency of particular Members. I include the difference in a

dummy variable that equals 1 if there is a new prime minister in year t-1 as another

instrument for differences in road acts in t-1. I label this variable ∆Prime Minister in t-1.

Aside from political variables, I also estimate a specification that includes the

difference in road acts in t-2, the difference in the real yield on government bonds in t-2,

the growth of industrial production in t-2, and the difference in the war dummy in t-1 as

instruments for differences in road acts in t-1. Two-year lagged differences are valid

instruments as long as they are not correlated with differences in canal acts in year t after

including one-year lagged differences of all these variables. I have already implicitly

made this assumption by not including two-year lagged differences in equation (1).

Table 3 shows the first-stage estimates for differences in road acts in t-1. The first

specification includes ∆Road in t-2 and the political variables as instruments. The second

specification adds the difference in the real yield on government bonds in t-2, the growth

of industrial production in t-2, and the war dummy in t-1 as instruments. The estimates

15

show that the instruments in the second specification are more highly correlated with

differences in road acts in t-1. The election dummies are both negative and significant.

The difference in the real yield on government bonds in t-2 is negative and significant

and the growth of industrial production in t-2 is positive and significant. Overall the

instruments are jointly significant at the 95% confidence level, but the f-statistic is 2.31

indicating that the explanatory power of the instruments is not as high as one would like.

Table 4 reports second-stage estimates for differences in canal acts in t. The columns

correspond to the same specifications for the first-stages reported in table 3. In both

cases, the second stage drops the difference in harbor acts in t-1 because this variable is

also endogenous. I also drop the difference in canal acts in t-1. The main finding is that

the difference in road acts in t-1 still has a positive effect on differences in canal acts in t,

although it is statistically significant only in the second specification that includes the

difference in real yields on government bonds in t-2, the growth rate of industrial

production in t-2, and the difference in the war dummy in t-1 as additional instruments.

Overall the estimated effect of spillovers from roads to canals is larger in the two-stage

least squares estimates than in ordinary least squares. These results provide reasonably

strong evidence that there was a positive spillover from road improvements to canal

improvements. More generally, it indicates that inter-modal network externalities

influenced the development of the British transport network from 1760 to 1830.

IV. Conclusion

Transport networks represent a combination of several infrastructure modes. Each

mode can operate independently, but only to a limited extent because of the need for

16

trans-shipment. Goods entering ports rarely stay near the harbor, and instead they are

shipped by rail, road, or waterway to distant markets or factories. Some goods, like

agricultural products, are shipped by road from dispersed locations before being

transported by rail or water over greater distances. Different modes also complement one

another by relieving congestion. Without adequate roads or airports, passengers and

light, high-value goods must be shipped by rail or water, thus adding to congestion on

these modes. Likewise without rail and waterways, freight and heavy, low-value goods

will add to congestion on roads and in the air.

Although it is clear that different modes are complementary, it is not obvious that

inter-modal externalities affect the development of transport networks. For example, it is

not evident that private or public authorities would build or improve fewer roads if ports

and other waterways were under-developed. The potential for inefficient investment is

likely to be greater when decision-making is decentralized, because individuals or

organizations do not take spillovers into account when they choose whether to undertake

a project.

This paper uses history to address whether inter-modal network externalities can have

a significant effect on the development of transport networks. It focuses on the

construction and improvement of roads, canals, and harbors in Britain from 1760 to 1830.

Over this 70-year period, Britain made substantial investments in its transport network,

making it one of the most extensive in the world. British transport development was also

unique in that it was highly decentralized. Local individuals, cities, and county officials

initiated projects by submitted petitions to Parliament, who then modified and approved

proposals through acts. I use data on road, harbor, and canal improvement acts to

17

investigate whether there were spillovers between these three modes. The econometric

results show that canal acts increased whenever road and harbor acts increased in the

preceding year. The two-stage least squares estimates suggest the increases in road

improvements acts likely caused canal acts to increase in the following year.

The results have implications for the literature on the development of the British

transport network during the Industrial Revolution period. Canals are often viewed as the

most important infrastructure improvement of this era, and there are also suggestions that

canals spurred the development of other infrastructure modes. The results here suggest

that canals did not have spillover effects on roads and harbors. Instead, canal

improvements were driven partly by improvements in roads and harbors. The results also

have broader policy implications because they suggest that inter-modal network

externalities can influence the development of transport networks, particularly under a

decentralized system of decision-making. It is not yet clear whether there was under-

investment or delays in canal improvements because road and harbor authorities did not

internalize the spillovers from their investment, but it does appear that there was a

potential for inefficiency. Future research may reveal whether decentralization has

consequences for efficiency and thus whether some type of policy intervention is

warranted.

18

References

Albert, William. 1972. The Turnpike Road System in England, 1663-1840. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Armstrong, John and Philip Bagwell. 1983. “Coastal Shipping.” Pp. 142-176 in

Transport in the Industrial Revolution, edited by Aldcroft, Derek and Michael

Freeman. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Bogart, Dan. 2007. “Neighbors, Networks, and the Development of Transport Systems:

Explaining the Diffusion of Turnpike Trusts in Eighteenth-Century England.”

Journal of Urban Economics 61: 238-262.

Clark, Greg. 2001. “Farm Wages and Living Standards in the Industrial Revolution:

England, 1670-1869.” Economic History Review 3: 477-505.

Crafts, Nicholas, and C. Knick Harley. 1992. “Output Growth and the British Industrial

Revolution: A Restatement of the Crafts-Harley View.” The Economic History

Review 45: 703-730.

Duckham, Baron F. 1983. “Canals and River Navigations.” Pp. 100-141 in Transport in

the Industrial Revolution, edited by Aldcroft, Derek and Michael Freeman.

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Evans, Eric J. 2001. The Forging of the Modern State: Early Industrial Britain 1783

1870. London: Longman.

Global Financial Data. 2007. “United Kingdom 2 1/2% Consol Yield .”

http://www.globalfinancialdata.com/index.php3?action=detailedinfo&id=1301

(last updated August, 2007).

Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons. 1803. Journals of the House of Commons

19

London.

Holmes, Geoffrey and Daniel Szechi. 1993. The Age of Oligarchy: Pre-Industrial Britain

1722-1783. London: Longman.

Innes, Joanna. 1998. “The Local Acts of a National Parliament: Parliament’s Role in

Sanctioning Local Action in Eighteenth-Century Britain.” Pp. 23-47 in

Parliament and Locality,1660-1939, edited by David Dean and Clyve Jones.

London: Edinburgh University Press.

Levinson, David. 2002. Financing Transportation Networks. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Parliamentary Archives. 2007. “Portcullis.”http://www.portcullis.parliament.uk/DserveA/

(last updated August, 2007).

Pawson, Eric. 1977. Transport and Economy: The Turnpike Roads of Eighteenth

Century Britain. New York: Academic Press.

Wooldridge, Jeffrey. 2002. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data,

Cambridge MA: M.I.T. Press.

20

Tables

Table 1: Correlations: road, harbor, and canal improvement acts, 1760-1830

(1)

∆Road in t

(2)

∆Harbor in t

(3)

∆Canal in t

∆Road in t-1

-0.21

-0.06

0.31

∆Harbor in t-1

0.13

-0.56

0.19

∆Canal in t-1

-0.07

0.01

-0.21

Sources: see text. Notes: ∆x in t-1 references to the difference in variable x between year t and t-1.

21

Table 2: Determinants of differences in Canal Improvement Acts

Dependent variable: ∆Canal in t

Variable Coefficient

(standard error) ∆Road in t-1

.112

(.057)* ∆Harbor in t-1

.195

(.161) ∆Canal in t-1

-.206 (.169)

∆Real Yield on Government Bonds in t-1

-.065 (.052)

Growth rate of industrial production in t-1

.057

(.053) ∆War Dummy in t

3.218

(1.88)* Constant

-.016 (.344)

N

69

R-square

0.32

Notes: Robust standard errors reported. * indicates statistical significance at 90% or above.

22

Table 3: First-stage Coefficient estimates for Instruments

Dependent variable: ∆Road in t-1

Variable

(1) Coefficient

(standard error)

(2) Coefficient

(standard error) ∆Road in t-2

-.233 (.140)

-.297

(.152)* Election Dummy for t

-1.68 (1.65)

-3.981 (1.83)*

Election Dummy for t-1

-1.69 (1.35)

-3.18

(1.69)* ∆New Prime Minister in t-1

2.45

(1.64)

2.36

(1.43) ∆Real Yield on Government Bonds in t-2

-.327

(.133)* Growth rate of industrial production in t-2

.383

(.202)* ∆War Dummy in t-1

-.517 (2.01)

Constant

.647 (.99)

.378

(1.20) ∆Real Yield on Government Bonds in t-1, Growth rate of industrial production in t-1, and ∆War Dummy in t included

Yes

Yes

F-statistic for joint significance of instruments (P-value)

1.54

(0.20)

2.31

(0.03)

N

68

69

R-square

0.20

0.32

Notes: Robust standard errors reported. * indicates statistical significance at 90% or above.

23

Table 4: Second-stage estimates for Differences in Canal Acts

Dependent variable: ∆Canal in t

Variable

(1) Coefficient

(standard error)

(2) Coefficient

(standard error) ∆Road in t-1

.206

(.149)

.224

(.109)* ∆Real Yield on Government Bonds in t-1

-.026 (.060)

-.022 (.056)

Growth rate of industrial production in t-1

.101

(.066)

.102

(.069) ∆War Dummy in t

2.98

(1.96)

2.895 (1.76)

Constant

-.091 (.370)

-.092 (.373)

∆Road in t-2, Election in t, Election in t-1, ∆New Prime Minister in t-1 included as instruments

Yes

Yes

∆Real Yield on Government Bonds in t-2, Growth rate of industrial production in t-2, and ∆War Dummy in t-1 included as instruments?

No

Yes

N

68

68

Notes: Robust standard errors reported. * indicates statistical significance at 90% or above.

24

Figures

Figure 1: The Number of Road, Harbor, and Canal Improvement Acts, 1760-1830

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

1760

1763

1766

1769

1772

1775

1778

1781

1784

1787

1790

1793

1796

1799

1802

1805

1808

1811

1814

1817

1820

1823

1826

1829

Act

s in

eac

h Ye

ar

roads canals harbors sources: see text.