Indian Streetscape- Screen

-

Upload

nivedhithavenkatakrishnan -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of Indian Streetscape- Screen

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

1/21

Mohenjo-daro to Mumbai - Indian Streetscape

ByK. Munshi

ProfessorMiddle East Technical University

06531 Ankara, TurkeyTel: 90-312-210 6205

email: [email protected]

I am thankful to the organisers of this

conference for inviting me to present apaper. Time was short for preparation as

the invitation came on 3 April 2001 and thepaper was to be sent on 16 April 2001. I

therefore tried hard to do as much justice aspossible to the topic of this paper and tocomplete it in time, as it would be pity to

miss the opportunity to meet eminentdesigners of Turkey at the conference in this

great historical city of Istanbul.

From the title of this paper you must haverightly guessed that I come from India,

Hindistan, as you know it, and these days I

am visiting professor at METU. You mighthave also noticed that I chose the word'streetscape' rather than street furniture. One

reason is that there is not any significantactivity regarding the design of street

furniture, as we generally understand fromEuropean perspective. Therefore there are

not many modern, good, authentic andhonest examples of street furniture, which

could be shown at this conference.Nevertheless, having such a long and rich

history, of architecture behind us, there aremany things, which could be presented. The

Indian streetscape is one such topic, whichcan be discussed because it is so rich and

varied.

I have chosen a theme that takes us on ajourney of looking at streetscape from the

very earliest times of lndian (Indus)

civilisation through the Buddhist age, andbriefly discuss its impact on the streetscape

of recent times.

Harrapan age

The earliest civilisation of which we havesome record is the Indus Valley Civilisation,

known as the Harappa culture from themodern name of the site of its two great

cities, one on the left bank of River Ravi inPunjab and Mohenjo-daro, the second city,

is on the right bank of the Indus River, some400 km from its mouth.

Harrapa Civilisation - Sites

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

2/21

It has been difficult for the historians to fixthe date of beginning of this civilization, but

from the faint indications, it seems thatIndus cities began in the first half of 3

rd

millennium BC and continued well into the

2

nd

millennium.

Each city had a well-fortified citadel, which

seems to have been used for both religiousand governmental purposes. The regular,

rectilinear grid plan of the streets and strictuniformity in such features as weights and

measures, the size of the bricks (1:2:4 ratio)and even the layout of the great cities,

suggests of a single centralised state.

The important feature of Harappanstructures apparently was, that they were

very utilitarian and devoid of anyarchitectural decorations or embellishments.

The street plans of Indus cities remained

unchanged for about 1000 years, with citieshaving similar plans. To the west of each

was a 'citadel', an oblong artificial platform30-50 feet high and about 1200 x 600 feet in

area.

Harappa CityHypothetical reconstruction

The main streets, some as much as 30 feetwide were quite straight and divided the city

into large blocks, within which werenetworks of narrow unplanned lanes.

The Main Street

Lanes on which the doors opened

Standardised burnt brick of good quality was

the usual building material for dwellinghouses and public buildings alike. The

houses, often of two or more stories, thoughvaried in size, were all based on much the

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

3/21

same plan with a central square courtyard,around which there are number of rooms.

Central Courtyard in a Harappa house

This plan is followed today in buildings of

traditional type and even palaces, though thematerials used are varied.

The entrances were usually in the side

alleys, and no windows faced the streets.This is a unique feature, which must have

presented a monotonous streetscape of brickwalls. There is however no evidence of use

of color to enliven the environment and, ofcourse the remains of that would not have

withstood the vagaries of time, if at all it

was there.

Interior of a Harrapa house

Bath in Harrapa house

The houses had bathrooms, the design ofwhich shows that the Harappan, like the

modern Indian, preferred to take the bathstanding, by poring pitchers of water over

his head. The bathrooms were provided bythe drains, which flowed into sewers under

the main streets, leading to soak pits. Thesewers were covered throughout their length

by large brick slabs. This would have beenanother unique feature of their streetscape.

Covered drains under the Main Street

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

4/21

Covered drains under the lanes

The most striking of the few large buildings

is the great bath in the citadel area ofMohenjo-Daro. This is an oblong bathing

pool 39 x 23 feet in area and eight feet deepconstructed of beautiful brickwork. It could

be opened by a drain at one corner and wassurrounded by a cloister on which opened a

number of small rooms.

The Great Bath at Mohanjo-daro

This concept of tank has been carriedforward till today and we have many

examples, which can be found in templesand palaces and stairwells of Gujarat.

Stair-wells of Gujarat

Ghats on rivers

The Indus Civilisation declined probablysometime early in the second millennium

BC for the excavations reveal that its citieswere then falling into a state of decay. A

Greek writer relates that here were 'theremains of over a thousand towns and

villages once full of men'.

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

5/21

Remains of a Harappa city

Vedic Age

After this decay, when art of building comes

into view, this no longer consists of well laidout cities of finished masonry, but takes a

much more rudimentary form of humblevillage huts constructed of reeds and leaves

and hidden in the depths of the forest.

Vedic Age style thatched huts as of today

This culture, where the elementary type offorest dwelling appeared probably towards

the end of second millennium BC and incourse of time laid the foundations of Vedic

age.

We still find remnants of such living invillages across India and therefore not

difficult to imagine the streetscape of thosetimes with mud walls of the huts on both

sides of main lanes, and thatched roofsextended to cover the front verandah.

Village hut - today

It is of interest to note that these mud and

thatch dwellings also do not have the doorsor windows opening on the main lanes like

what we see in Harappa culture.

Indian village streetscape - today

It can probably be said that Vedic peoplecarried forward some visual architectural

features / symbols from the earlier Harappaculture, although the technology of brick

making was lost along the way or it was

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

6/21

found expensive and not relevant to theirnew way of living.

Two theories of exodus of the people of

Indus civilization from their abodes that

could be plausible are, one the devastatingfloods and water logging ravaged their citiesand farm lands or changed course of rivers

creating draught, and two, they weremassacred and looted by foreign aggressors

forcing them to the East into the forests ofGangetic plains, or basins of Narmada,

where they survived on forest foods, andcattle which they brought along. Cattle have

been important for Vedic people as it wasfor Harappa people, and probably became

the primary means of survival in difficulttimes after migration,. The importance of

cattle is evident from the terracotta seals ofHarappa culture.

Harappa terracotta Seal Sacred bull

The cow, which provided sustenance,therefore, became Mother and Holy, in

Vedic Age as well; which it is even now.

Looking at the similarities in the use ofbangles all the way up the arms of women

from Kuchh and the bronze statue ofDancing girl excavated from Mohenjo-

daro, it could be inferred that some of these

people moved to the South into the places,which is now Gujarat and happened to retain

some of the traditions of the earlier times.

If we accept this, we can say that colourful

motifs that people of Kuchh use to decoratethe walls of their homes could possibly have

also come from their earlier aesthetictraditions of Harappa.

Kuchh houses - today

The stepped decoration and particularly theprofile on the walls of these huts is akin to

the brick arches of the windows, doors anddrain outlets of Harappa houses.

It does not seem possible that people with

high engineering and building skills asHarappans, the civilized city dwellers, and

hygiene conscious people, could be so bereftof any aesthetic sense, leaving the brick

walls bare, un-plastered and withoutembellishments. One could probably assume

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

7/21

that walking along the wide avenues was acolourful experience with plastered walls

painted with colored motifs as we see on thewalls of Kuchh village huts.

Drain outlets with stepped brick arches

Stepped motifs on mud huts in Kuchh

The proportions and decoration on the ShivaPashupati Seal and the design on the

garment of The Priest King is a testimonyto their sense of aesthetic sensibility.

Having to protect themselves and theirproperties from the ravages of wild animals,

Vedic people surrounded their littlecollection of huts (Grama) with special kind

of fence or palisade. This fence took the

form of bamboo (easily available material inthe forests) railing, with the upright posts(Thabha), which were supported by 3

horizontal bars called Suchi, or needles asthey were threaded through holes in the

uprights.

The important element of Indian streetscapewas the village fence or palisade, which later

became the emblem / icon of protection.

From its bamboo origins it was incarnatedand immotalised in stone in Buddhist

architecture of Stupas.

Thabha and Suchis in stone at Sanchi Stupa

It was universally used, not only to enclosethe village, but as a fencing around fields

and to preserve anything of a special orsacred nature. In the palisade encircling the

village, entrances of a particular kind weredevised. These were formed by projecting a

portion of the bamboo fence forward, and aportion at right angle, to create an opening

on the side, so as not to have a throughpassage. A portion of the fence is raised up

to create the gateway arch (Gramadwara).

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

8/21

This configuration of the fences and gatescontinues to live in the architectural

conscience of Indian society and can be seenin the design of fences in todays villages

and towns and are the noticeable elements of

Indian streetscape.

Gramadwara inVedic village-Reconstruction

Village houses with Vedic style fences and

covered verandah

Through the Gramadwara the cattle passed

to and from their pastures. It survives in theform of Gopuram (cow-gate), the entrance

pylon of the temple enclosures in the south

of India.

From the design of Gramadwara (village-

gate) was derived the characteristic BuddhistArchway called Torna, a structure which

was carried with that religion to the FarEast,

Torna from Mukhteswar temple at Bhubaneshwar

It is known as the Torii in Japan and the Piu-lu of China as a symbol of protection and

safety. The Torna gates at the Stupa inSanchi are well known examples.

To-ri-i at a shrine in Japan and Torna at Sanchi

Towards the middle of first millennium BC

Vedic community expanded and the townsarose at important centres. The traditional

structural features were reproduced on alarger and in more substantial form. Due to

the rivalry between the various groups thetowns were strongly fortified. They were

surrounded by a rampart and woodenpalisades, which closely resembled the

original fences of Vedic village. This wasthe era of timber construction of the Vedic

Civilisation.

Cities largely of wooden construction beganto appear at various parts of the country, and

according to Dhammapala, the great

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

9/21

Vedic Cities a reconstruction from rock-

cut Buddhist caves

Buddhist commentator, they were plannedby an architect named Maha-Govinda who is

stated to have been responsible for thelayout of the several of the capitals of the

north India.

Vaishnava temple at Srirangam Grid plan

These cities were rectangular in plan andwere divided into four quarters by two main

thoroughfares intersecting at right angles,each leading to a city gate.

In the royal quarter, the palaces were built

around an inner courtyard and had a largecentral window for Darshan or salutation of

the king. This feature has been carriedthrough till recent times. The Mughal,

Rajput palaces had prominent centralbalconies for the purpose of salutation.

Since these had to face the street to the fullview of the people and therefore became an

important feature of Indian streetscape.

Rajput Palace at Udaipur

Palace pavilions with water fountains

The royal quarters had pleasure gardens with

pavilions having fountains and ornamentalwaters attached. In Vedic age these

pavilions were of wood and thatch and latermarble and stone were also used. The

tradition carries on and in many modern daypublic gardens, simulated wood and thatch

is also used for building pavilions.

With the rise of Mauryan dynasty towardsthe end of fifth century BC, marked cultural

progress was made. Among otherachievements, art of building, stimulated by

royal patronage took notable steps forward.Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador who

resided in the court of the EmperorChandragupta about 300 BC, gives a

striking picture of the Mauryan capital ofPatliputra - situated along the banks of

Ganges like immense castellated breakwater (15 Km. long and 2.5 Km. broad),

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

10/21

surrounded by stupendous timber palisadewith holes for archers. It was protected by a

wide and deep moat around it. At intervalswere bastions with towers, over five

hundred in number and as many as sixty-

four gates. The moat had floated lotus andother aquatic plants and was enclosed withusual railing palisade.

Mauryan capital Pataliputra with surrounding moat

a reconstruction

The balcony in front was minstrels' gallery,and the projected casements on each side

were priests chambers. Covered balconiesand decorative structure are prominent

features of frontage of the houses on thestreets and important elements of streetscape

in Maurayan times and thereafter.

Especially noticeable are the city gates, allof which were designed in much the same

way as gramdwara (village-gate) but inmuch more refined form of Torna. Near the

gateways is what seems to be a formidableangle-tower; while overhanging the walls

are pillared balconies, railed balustrades andmagic casements. Carpenters of the time

were highly skilled manipulators of woodcreating artistic results with embellishments

also having practical use, blending very wellthe functional aspects with aesthetics.

Even in the Rig-Veda the carpenter is

accorded a place of honour among allartisans, as village community depended on

them for some of its most vital needs ofconstruction and defense.

The arched window admitted light throughits tracery. The echoes of this are found in

later day marble, wooden or bamboolatticework called Pinjra.

Latticework examples in Buddhist caves

To filter the light and improve air circulationthrough Pinjra was the architectural

response to the hot climate to keep theinteriors cool and lessen the glare.

Pinjra dominated faade of Hawa Mahal Jaipur

Pinjra concept has been extensively used inRajput and Mughal palaces and in the

colonial period bungalows of the British.

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

11/21

Pinjras in palace windows

Colonial Bungalow with Pinjra (Jalis)

Later efforts were made to include stonemasonry along with wood to create city

walls. The beginnings are seen in the citywall of Rajgriha, the ancient capital of

Magadha, now in ruins at Rajgir, near Patna,in Bihar. The construction of masonry was

without mortar. These walls of greatstrength and of cyclopean proportions were

made by piling of massive undressed stoneseach between 3 & 5 feet in length but

carefully fitted and bonded together.

Massive stone masonry walls at Rajgir

Buddhist Architectural age

Third Mauryan ruler of Magadha, theemperor Asoka ascended the throne in BC

274. In BC 255, he inaugurated Buddhism

as state religion of the country. With thechange in religious system of India alsocame a marked advance in arts. The

principal contribution during this time were:1) series of edicts inscribed on the rocks

2) construction of Stupas 3) monolithicpillars 4) monolithic accessories to shrines

5) group of rock cut chambers. All thesewere part of public architecture, mostly

meant for spreading the message of theBuddha.

Wanting to immortalise the message ofBuddha, and symbolising the creed, a lofty

free standing column about 30 to 50 feet

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

12/21

high was devised and erected on speciallyselected sacred sites, each carrying above its

capital a magnificent Buddhist emblem

These were communication devices and

were distributed throughout Asokan Empire

and probably became the focal points in thecities of those times.

While the stupas were significant for theirstructures, the monolithic pillars could be

regarded for their artistic qualities.

Line of pillars at Rampurva, Laurya, Araraj,Nandangarh and Kolhua were evidently

placed at intervals along the ancient royalroute from Pataliputra to the borders of

Nepal (sacred land of Buddhism).

Since then, many kings and emperors haveused this device (pillars towers and

columns) to commemorate the victories orimportant events during their reign.

Many of these marked the courses of aPilgrim's Way to holy places and so were

important elements of streetscape of Asokanperiod and thereafter.

Pillars (Kos Minar) marking Grand TrunkRoad constructed by Sher Shah Suri

An important visual characteristic of all the

stone productions of Asokan period is thehigh lustrous polish resembling fine enamel

with which the surfaces even of rock cutchambers, were invariably treated. So

striking was this appearance that in fifthcentury, it excited the admiration of the

observant Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hien for hewrites that it was 'shining bright as glass'

despite weathering thousand years of harshclimatic conditions of Indian plains.

The Buddhist emblem of Dharma Chakra

(24 spoked wheel) is now part of the

National Flag of independent India. Thefour-headed lion, which is atop manyAsokan pillars, has become the seal of the

Government of India.

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

13/21

During next couple of centuries the Buddhist

art of building flourished, as is exemplifiedby Rock-cut architecture where the facades

were so intricately carved as if the materialwas wood.

Buddhist cave architecture

Stupas also became bigger, more complex

and highly decorative. The style reached itszenith in Amravati stupa, 250 AD.

The refinements took the form of replacing

the impermanent materials like brick and

Amravati Stupa

wood by stone. Chief among these is the

Stupa at Sanchi (reconstructed in B.C.150,

in Central lndia).

Stupa at Sanchi

It is interesting to note the similarities in thevisual concept of the gates and fencing at

Sanchi, to the Torna (gate) and the fencingin the early Vedic villages.

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

14/21

Sanchi Stupa Plan with 4 Torna gates

These elements have got so sanctified thateven now on special days, the Tornas made

from stringed flowers and leaves are placedon the doors of modem houses, gates of the

buildings, shop fronts to 'preserve what isinside and to ward off eviI. So deep rooted

is concept of Torna in Indian culture as asymbol of safety, it is tied across the bonnet

on the front of the vehicles for protection, onthe auspicious day of Dasera, becoming an

important element of streetscape even now.

Brick architecture flourished mainly in thealluvial plains of India where good quality

clay was available.

Immense buildings almost entirelycomposed of brick were constructed duringthe early medieval period at Mathura and

Benaras. Stupa at Budh Gaya and Sarnathand the shrines around it are good examples

of the brick architecture built in the 7th

Century AD. In these structures the gates

and fencing follows similar patterns ofTorna, Thaba & Suchi as in earlier Vedic

villages.

Great heights were a unique visual feature ofthese brick structures. These were probably

built due to ease of handling bricks becauseof their small size as opposed to stone,

which was heavy and could not be carried to

Stupa at Sarnath

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

15/21

such heights. Fa-Hien at the beginning offifth century and Hieun Tsiang in the

seventh century was much impressed bytheir tall proportions.

Nalanda Ruins

Referring to 'a great Vihara (Buddhistshrine) some two hundred feet high and toanother shrine containing a copper image

more than eighty feet high in a six storiedbuilding, the Hieun Tsiang writes about the

Nalanda, the great centre of learning - 'thesoaring domes reached to the clouds, and the

pinnacles of the temples seemed to be lost inthe mists of the mornings'.

They also talk about glittering metal roofs,

the glazed tiles of brilliant colours, thepavilion pillars richly carved in the form of

dragons, the beams painted red orornamented with jade, the rafters

resplendent with all the colours of rainbowand the balustrades of carved open work.

This profusion of colour and ornamentation

can also be seen in later day temple andother monumental structures.

Temple at Buddh Gaya when first built a

reconstruction

Geometric patterns found at Sarnath

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

16/21

In these brick structures, besides sculpturaland organic motifs, geometrical patterns are

also visible. While Nalanda is in the ruins,Buddha Gaya is the sole living example of

this style.

Mahabodhi Temple at Buddha Gaya

Modern age streetscape

During the early years of twentieth century

India saw a surge of big metropolitan citieslike Calcutta, Bombay, New Delhi and

others. The city of Calcutta served as thecapital of the British Raj till 1911 and has

Writers Building, Kolkata - Classical

preserved many buildings, which provide atestimony to the British period Classical

style in Calcutta.

Magnificent European architecture

dominated the new business and port city ofBombay with large public buildings, likeRailway stations, Post & telegraph offices in

Victorian Neo-Gothic style, and privatebuildings in similar styles along the main

streets like DN Road.

Railway Terminus, Mumbai- Neo Gothic

Streetscape D. N. Road, Mumbai

Marine Drive, Mumbai Art Deco Style

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

17/21

Art Deco building in Mumbai

Art Deco, a distinct new style ofarchitecture, was introduced in Mumbai in

the 1930s. It was well adapted to the cityalong with the Victorian Gothic of the

earlier century.

New Delhi became the capital of BritishIndia in 1911, which was planned by

Architect Lutyens.

Rashtrapati Bhawan Viceroys Palace

The initial precinct usually referred to, as

Lutyens Delhi is known for its wide, tree-lined boulevards and numerous significant

structures. The city was laid around twocentral promenades with focus on the axial

planning.

In the last 100 years or so many Indian citieshave grown through slow evolutionary

process and building activity took placewherever the land became available. There

Broad Avenues of New Delhi

seemed less of planning than was inevidence in the past. Agricultural land

around the old cities was converted intourban land. This activity gained tremendous

momentum during post independence eradue to partition, when millions of refugees

settled around big as well as small cities.Another important factor was migration

from rural hinterland to cities because ofrapid industrialization in and around cities

and lack of opportunities of work in ruralareas. First the houses came up and long

after, they were connected throughpathways, lanes or so called roads. Electoral

politics played the usual role and took thetoll. All these resulted in overcrowding and

Slums of Mumbai

development of slums without social andurban amenities. Notable examples are

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

18/21

Bombay, Calcutta, Kanpur where hugeslums rose right across the cities because of

this unplanned process. Due to politicalpatronage, the slums have become

permanent urban features. Almost half the

population of Bombay lives in these slums.

Along with this unplanned growth we see

many examples of planned citydevelopment. One good example is

Chandigarh - the capital city of northernstate of Punjab, which was designed by

celebrated French architect Le Carbusier.

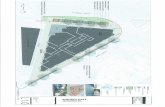

Chandigarh Grid Plan

Chandigarh was a grid plan with sectors for

residences, commercial areas, offices,markets etc. Emphasis was also put oncreating monuments - the buildings for

legislature, high court, but little attentionwas paid to objects of smaller scale like

Chandigarh Streetscape

street furniture - lampposts, bus stops etc.Since Chandigarh became a model for

development for many cities, naturally no

attention was paid to streetscape. Streetscapeemerged as default.

Chandigarh Streets

Another example of new city was the

development of Navi Mumbai (NewBombay), which was supposed to be a

counter magnet to the growing population ofBombay. We made the same mistakes again.

Architects with pretensions of city plannerslaid emphasis on apartment blocks, office

blocks, market blocks, and not on habitatconsiderations, sociology of the spaces,

community interactions. Dynamics of livingwas completely ignored. And Navi Mumbai

succumbed to the forces of evolutionaryprocesses. Now we see the hawkers

occupying the pavements, pedestriansspilling on the roads and vehicular traffic in

chaos.

Khargar Railway Station, Navi Mumbai

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

19/21

Notable exceptions have been design ofsuburban rail stations in New Bombay area,

which are modern, clean and have wellregulated traffic.

The trend that was recently witnessed wasthe rise and fall of builders' lobbyparticularly in Bombay. Archaic rent control

laws coupled with large influx of people andlimited land availability resulted in very

high real estate prices. Builders of apartmentblocks, office blocks started making huge

profits. At one time real estate prices werematching New York prices and with

woefully less amenities.

Upmarket Apartment Block, Mumbai

This resulted in many businesses shifting

offices to suburbs or to other cities. Lessnumber of people came to Mumbai resulting

in the slump in demand. Builders having gotused to high prices tried very hard to

maintain the price line. They offeredadditional and fancy amenities. The

apartment blocks came with club facilities,swimming pools, gymnasiums, satellite dish

connections etc. Building facades became

highly decorative particularly with Europeanmotifs. Gothic started rubbing shoulderswith art nouveau.

Columns and fountains sprung at road

crossings. Landscaping was done alongroads and around buildings. So one would

see a totally new ambience in these areas.

Now builders are competing to outdo eachother resulting in this neo eclecticism. And

that is what we have now in suburbanBombay.

Hiranandani Gardens Precinct, Powai

Mumbai

This trend is very disturbing to the puristsand modernists, as one can understand, but

their voices are quite subdued.Conservationists have however started

making some mark. One of the southBombay streets which is flanked by very

fine examples of colonial architecture hasbeen declared as heritage precinct and

efforts are made to show this in its full gloryby removing very large advertisement

hoarding, sign boards which hide thesebeautiful facades.

Kotachawadi Village in South Mumbai

Conservationists have also succeeded in

getting heritage status for the pre-colonialvillages, which are nestled in the city and

fortunately have so far retained their

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

20/21

architectural exclusivity, despite tremendouschange around them. The people living in

these villages are really proud of theirheritage and want to continue living there,

bearing many inconveniences and pressures.

Heritage listing will fortunately help them.

One of the recent movements spearheaded

by design institutions along with youngconservation architects, was the study of the

heritage precinct of South Bombay, to makerecommendations about its upkeep and

beautification, and also for the design ofstreet furniture, which will harmonise with

the streetscape of this area. These are merereports and we are not sure when these will

be implemented.

Street Art Gallery

This area being architecturally so very

interesting, many artists are patronising it.

Street art galleries have come up whereartists display at a very nominal charge. In

winter when the weather is good, everySunday a festival is held, now known as

Kala-Ghoda Festival named after theprominent crossing in the area.

These are organised by groups who are keen

on enhancing the cultural scape of Bombaystreets.

Performance at Kala Ghoda Festival

Jehangir Art Gallery in Mumbai

Our institute contributes in a small measure

to this activity. A few years back, Iorganised an exhibition titled 'Sculpture in

Light'; at Jehangir Art Gallery, the premierart gallery of Bombay situated at Kala-

Ghada.

Neons defacing building facades

-

7/23/2019 Indian Streetscape- Screen

21/21

The theme was to bring the fluorescent neonlights, used for advertising and which are

such eyesores on the beautiful facades of thebuildings around that area, into the interior

spaces and create objects of art from a very

interesting though highly abused material(lighted neon tube). These are some of thesmall though significant steps taken to

humanise the streetscape elements of thisvast metropolis of Bombay, known in local

Marathi language as Amci Mumbai (ourMumbai).

Neon Sculpture for the interior

I am afraid that this paper has not said

everything about the streetscape from'Mohenjo-Daro to Mumbai '. I have skipped

important periods of architectural history oflndia, notably post Buddhist Hindu and

Mughal period, which are better known, andwell documented, but I hope it will arouse

some more curiosity about the subject. Ifthat happens I will be happy.

References:1. Brown Percy, Indian Architecture

(Buddhist and Hindu Periods), D.B.Taraporewala Sons & co. Pvt. Ltd.,

Bombay, 1959.

2. Basham A.L., The Wonder that wasIndia - A survey of the history and culture ofIndian sub-continent before the coming of

the Muslims, Taplinger PublishingCompany, New York, l967.