In Quest Webern 2

-

Upload

onir-garcia-cerda -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

2

description

Transcript of In Quest Webern 2

-

August 30, 1945, just a fortiiiglit before his violent end.

A liandsome woman in her forties, brunette and gray-eyed, of gentle man-ner and kindly face, Hermine von We-bein had a long story to tell during that luncheon meeting, amid the din of noise and laughter in the crowded room. It was as if a mighty spring, gutted by years of work and isolation, suddenly gushed to the siu'face. Experiences, long repressed and thus much more intensi-fied within her soul, broke loose as if an inner vacuum had found resonance.

Vienna had fallen to the Russians on April 13, 1945. Many inhabitants had left the city. Hermine, widowed and childless, had felt that lier place was with her mother and sisters. She liad stayed on and soon found a lixelihood, as well as a measure of protection, by working as a seamstress for the occupy-ing army. She related how she and her sistei's would board a truck at dawn each morning to be brought to the work-rooms where soldiers' uniforms wei'e re-paired; how her sisters invented a ruse to cover up her own lack of sewing skill; how at night they would be returned to her mother's dwelling, an old house at Peichtoldsdorf. The days were long and hard, but infinitely better than the nights when tlie women would often have to hide from the prowling soldiers, drunk with wine and victory.

J_N due time, Hermine and her sisters had so gained the good will of the offi-cers in charge that they secured permis-sion to visit her father-in-law's erstwhile home in the nearby suburb of Maria Enzersdorf. A lieutenant and a soldier, the latter with fixed bayonet on his rifle, escorted them to a scene of cliaos, dam-age, and dispersement. The round family dining table had a hole sawed in the center to hold a bucket for the washing chores of the soldiers billeted in the house. Webern's violoncello had been kicked in. Sculptures of Webern, his yoimgest daughter, Christine, and Gus-tav Mahler had been thrown into the yard, as had been hundreds of books and music volumes from Webern's per-sonal library. The composer's letters and other papers had been scattered about; they eventualh' were gathered, mashed into coal sacks, and kept in the cellar as kindling material for the fire. Furnish-ings and other belongings, thrown out of the second floor apartment which had been Webern's home, were K'ing all arormd the yard.

Hermine and her companions went to work. Rucksack load by rucksack load, the brave young women carried tfie rem-nants of Webern's earthly possessions from Maria Enzersdorf to Perchtolds-dorf, a distance of four kilometers. In a loft, above her mother's living quarters, the salvaged properties were deposited.

4H

They formed a pitifid lot, dirtied by the grime of earth and gravel, soaked by moisture, partly torn and damaged. Much was already too far gone to war-rant being salvaged, and no one knows how much had been burned or blown away.

Hermine went on to relate how, after the return of her sisters-in-law and their mother to Vienna, she had led them to the hideaway in the attic. By her effort to save what she could, she had wished in the first place to bring comfort to Anton von Webern, then still alive. After his death, she fathomed that his widow and daughters would take joy in what now had become relics and memories. Instead, the sight of these battered rem-nants excited only anguish. Wilhelmine asked her daughter-in-law lo destroy the broken cello so that she might never again be reminded of it. She and her daughters selected from the piles of rescued articles those few whicli they wished to keep. Some time later, the daughters returned and, going once more through the stacks of materials, extracted tlie many letters which their father had written to their mother, now deceased. Determined that these letters were never to be read by an outsider, they committed all of them to the fire.

Subsequently no one had been to the attic again. Hermine, rather than de-stroying the cello as her mother-in-law had requested her to do, kept it in her own dwelling. Years later, in 1957, .she decided to have the cello repaired and took it to an old instrument maker named Franz Hofer, who was to give it a new front. He had never finished the job, although Hermine often urged him to do so. The same afternoon when we had lunch together, she would go to Mi'. Hofer and fetch the cello, whether it was repaired or not. If I wanted it for the Webern Archive, she would be glad to have me give it a permanent home.

The same evening, a few hom-s after our first rendez\Ous, we had been to the apartment of Hermine von Webern, and there the cello was waiting. Hermine had taken it out of Mr. Hofer's shop over the old man's protest that he had not yet finished the repair. He still had not been able to find the three fragments of the original front; the ragged splinters bore mute testimony to a brutal act.

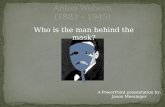

What had excited my special curiosity during our conversation was Ilermine's reference to a sculpture of Webern's head. The Webern Archive already housed the original terra cotta bust by Josef Humplik, of which a bronze rep-lica stands in the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien. But only two days earlier, during a meeting with a young musicologist, I had been shown a photo-graph of a Webern head which, in spite of many similar features, appeared to have been taken from a chfferent sculp-

ture. Now that Hermine had mentioned the bust, I wanted to convince myself. When she invited us to drive out to Perchtoldsdorf the next morning to take a look at the head in the attic, we quickly resolved to delay our departure from Vienna once again.

Now we were ofl' for the hunt on this nninviting, colorless morning of Austria's National Flag Day. The morning log grew even thicker as we approached Perchtoldsdorf, the medieval village at the outskirts of Vienna. Descending from one of the foothills of the Wiener Wald, we entered the small town and drove to the house at Hochstrasse 43, Hermine's parental home. Mrs. Fraii-ziska Schubert, her mother, still lived there. Hermine told us that .she and her sisters had resisted pressures to fiave the old house torn down; they wislied their aged mother to live out her days in fam-iliar surromidings.

We greeted Mi's. Schubert, just recov-ering from a cataract operation, and observed the same friendly mien and cheerful smile inherited by her daughter. A bowl filled with fragrant Italian prunes was oftered as a token of hospitality. The humble dwelling consisted of a combi-nation living and bedroom, with adjoin-ing kitchen; tlie stove provided warmth for both.

Out of the dimness of Mrs. Schubert's quarters, we stepped again into the court, thence entering an annex which once had served to house the carriage and farming utensOs. We clambered up a wooden ladder which led steeply to a trap door giving access to the loft. The attic was long and dark. Its only source of light came from a small window at the far end. Climbing over several beams, we made our way toward the window. There were old trunks, baskets, and boxes e\"erywhere. Books were stacked in piles. Among them lay heaps of print-ed music. Everything was covered by rubble, dust and cobwebs.

First, we located the Webern head, half hidden by a layer of debris. The sculpture proved indeed different from the well-known bust by Josef Humplik. This one, a plaster cast, apparently rep-resented a preliminary version. Then we came upon a sculptured head of Gustav Mahler, over life-size; as we were to learn, it had adorned the Webern home as long back as the children could re-m^ember, a testimony of Webern's vene-ration. The Mahler head was damaged, and its pedestal missing. Another Hump-lik sculpture, lying nearl)y, portrayed Webern's youngest child, Christine. Like the other busts, it is mentioned in the correspondence between the artists, pub-lished asAntonWchern Briefe an Hilde-gard Jone und Josef Humplik (Universal Edition, 1959).

While I was still examining the heads, Hermine and my wife Rosaleen had be-

SR/August 27, 1966 PRODUCED 2005 BY UNZ.ORG

ELECTRONIC REPRODUCTION PROHIBITED