In Play: An Important Tool for - Commerce Children's … An Important Tool for Cognitive ......

Transcript of In Play: An Important Tool for - Commerce Children's … An Important Tool for Cognitive ......

In ThIs Issue

FEATURE ARTICLE:

Play: An Important

Tool for Cognitive

Developmentpage 1

CLASSROOM HINTS:

Planning Assists

Children’s Executive

Function page 9

SPECIAL EDUCATION:

Play — An Intentional

Intervention!page 12

TRAINER-TO-TRAINER:

Supporting Executive

Function in Children’s

Playpage 14

NEWS BRIEFS

page 16

ASK US

page 16

VOLUME 24, NO. 3

Play: An Important Tool for Cognitive Development

Take a look at the play of Gabrielle, a

three-year-old who has a plan to play with

magnetic tiles:

At planning time, Gabrielle says, “I’m going to play with the doggies and Magnatiles in the toy area. I’m making a tall elevator.” At work time, Gabrielle builds with the magnetic tiles while playing with the small toy dogs, as she planned. She stacks the tiles on top of one another in a tower-like form—her “elevator”—then places some dogs in it. The elevator then falls over. She re-peats this several times but the eleva-tor continues to fall over. Gabrielle then arranges the magnetic tiles into squares, connecting them to form a row. Gabri-elle says to Shannon, her teacher, “I’m making doghouses because the elevator keeps falling down.” Shannon says, “I was wondering what you were building, because you planned to make a tall elevator going up vertically, and now you are using them to make doghouses in a long horizontal row. You solved the problem by changing the way you were building.” Gabrielle uses pretend talk while moving the dogs around. At one point she says, “Mommy, Mommy, we are hungry” and opens one of the doghouses and moves the dog inside where a bigger dog is placed. Gabrielle says, “Mommy says the food’s not ready, so go play.”

While moving the dogs around, Gabrielle says to herself out loud, “We have to find something to do until the food is ready.” Gabrielle says to Shannon, “Let’s pretend we are going to the park.” Shannon agrees and says, “I’m going to slide down the slide three times and then jump off the climber.” As Shannon pretends to do this with one of the dogs, Ga-brielle watches then copies her and says, “My dog jumped higher than yours.” She then says, “Mommy says we have to go home now. We need to move our dogs over there so they can eat.” The pretend play continues.

By SHANNON LOCKHART, HIgHSCOPE SENIOR EARLy CHILDHOOD SPECIALIST

Planning and recall times help children develop key cognitive skills that are part of executive function.

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 2

Play: An Important Tool for Cognitive Development, continued

At recall time, Gabrielle is using a scarf to hide some objects she played with. When it is her turn to recall, she gives clues about what is under the scarf. She shows the group a couple of magnetic tiles and dogs. Shannon asks her what she did with these materials during work time. Ga-brielle talks about the problem with the falling “elevator” and then recounts the story about the doggies.

Early childhood educators often make the point that “children learn through play.”

But what does this statement really mean? In the scenario described above, what

exactly is Gabriella learning as she plays? She is planning what she is going to do, car-

rying out her plan, and then recalling what she did (in the HighScope Curriculum, this

is known as the plan-do-review process). But did we realize that she is developing key

cognitive functions such as working memory, self-regulation (e.g., being aware of and

controlling her feelings and actions), internal language or “self-talk,” and the ability

to organize, focus, plan, strategize, prioritize, initiate, and perform other skills that

determine later success in school? Indeed she is, and these cognitive skills are all part

of what we call executive function — the cognitive abilities that control and regulate

other behavior. Play helps young children develop these abilities. Unfortunately, due

to the demands for accountability in public schools and pressure to accelerate young

children’s academic learning, time for play is either being eliminated or limited, and

play is much less often child-initiated or free from constraints.

In this article, we will review the legitimacy and validity of child-initiated play in

young children’s lives, and we will address the basics of executive function so that we

can become more intentional in our planning of, and support for, children’s play.

The Importance of Play

Stuart Brown, Founder of the National Institute for Play, has said that “play is any-

thing that spontaneously is done for its own sake…appears purposeless, produces

pleasure and joy, leads one to the next stage of mastery” (as cited in Tippett, July

2008; italics added). Edward Miller and Joan Almon describe play as “activities that

are freely chosen and directed by children and arise from intrinsic motivation”

(2009, p. 15). Jeannine Ouellette refers to play as “activity that is unencumbered by

adult direction, and does not depend on manufactured items or rules imposed by

someone other than the kids themselves” (Ouellette, 2007, para. 13). When children

play, they are actively engaged in activities they have freely chosen; that is, they are

self-directed and motivated from within.

Kenneth Ginsburg, stating the position of the American Academy of Pediatrics,

says that “play is essential to development because it contributes to the cognitive,

physical, social, and emotional well-being of children and youth” (Ginsburg, January

2007, p. 182). Play is so important to children’s development that the United Nations

High Commission for Human Rights (1989) recognizes it as a basic right of every child.

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

PUBLISHER CREDITS

HighScope Extensions is a practical resource for early childhood teachers, trainers, administrators, and child care providers. It contains useful information on the HighScope Curriculum and on HighScope’s training network.

Jennifer BurdMarcella WeinerJoanne TangorraEditors

Katie BrucknerPublications Assistant

Nancy BrickmanDirector of Publications

Kacey BeachMarketing Specialist

Sherry BarkerMembership Manager

Kathleen WoodardDirector of Marketing and Communication

Produced by HighScope Press, a division of HighScope Educational Research Foundation

ISSN 2155-3548

©2010 HighScope FoundationThe HighScope Foundation is an independent, nonprofit organization founded by David Weikart in Ypsilanti, MI in 1970.

Pretend play is particularly condu-cive to the development of self-talk, or children’s internal language about what they are doing and what they will do next.

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 3

The many books and articles written on the subject list a wide range of cognitive, emotional,

interpersonal, and creative benefits (refer to the sidebar on p. 4 for some highlights).

Many experts agree that play provides the foundation for learning and later academic

success. For example, research demonstrates the importance of child-initiated play (as op-

posed to play defined and directed by adults) in the development of language and literacy

skills. When children determine the direction and content of their own play, they have

many opportunities to hear and practice language. This type of language-rich play directly

influences future development of higher mental functions (Bodrova & Leong, 2007). When

children are allowed to initiate their own play, they are then able to express those choices in

words and to interact and converse freely with other children and adults. The International

Association for the Evaluation of Educational

Achievement (IEA) Preprimary Project, a cross-

national longitudinal study, found that children’s

language performance at age seven was signifi-

cantly higher when teachers had allowed children

to choose their own activities at age four (Montie,

Xiang, & Schweinhart, 2007).

Developmental psychologists identify four

types of child-initiated play: exploratory play

(discovering the properties of materials and tools,

not to make something, but for the pleasure of

doing it); constructive play (making things);

dramatic play (acting out “make believe” or

pretend situations and assuming various roles);

and for older children, games with rules.

Gabrielle was engaging in the first three types

of play, but especially in dramatic (make-believe)

play. When children spend time in make-believe play, they use self-directed talk and

develop other features of the critical cognitive skills of executive function (Spiegel, 2008).

We will look at how child-initiated play in general, and make-believe play in particular,

help to develop executive function.

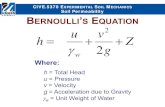

Components of Executive Function

Although researchers have not completely agreed on the elements of executive function,

Chris Dendy (2008) outlines five general components based on Russell Barkley and Tom

Brown’s work on attention deficit disorders. These components are presented below, with

the plan-do-review sequence described in Gabrielle’s play at the beginning of this article

serving to illustrate the connection between play and executive function.

Play: An Important Tool for Cognitive Development, continued

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Executive function (EF) is a term used to de-

scribe a set of mental processes that are

central to helping us organize and order our

actions and behaviors (Packer, 2009). It re-

fers to the cognitive abilities that control and

regulate other behaviors, and therefore en-

able goal-directed behavior. These include

the ability to initiate and stop actions, assess

and change behavior when needed, an-

ticipate outcomes, and plan future behavior

(Zelazo, Muller, Frye, & Marcovitch, 2003).

Executive function thus involves both concrete

behaviors and the ability to form abstract

concepts. We use executive function when

we perform such activities as planning, orga-

nizing, strategizing, delaying impulses, and

paying attention to and remembering details.

Children with high levels of self-regulation

and executive functioning do better in school,

both in academic areas such as literacy and

mathematics, and also in social adjustment

(Bodrova & Leong, 2007). “Poor execu-

tive function is associated with high dropout

rates, drug use, and crime…[whereas] good

executive function is a better predictor of suc-

cess in school than a child’s IQ” (Spiegel,

2008). These cognitive functions are begin-

ning to be developed long before children

enter formal schooling. In fact, the years

between three and five are especially impor-

tant in the development of executive function

because of changes in brain development

during this period, particularly in the frontal

cortex, which is responsible for regulating

and expressing emotion (Shore, 2003). En-

gagement in play is thus a major contributor

to physical and mental development.

What Is Executive Function?

By stocking the classroom with interesting materials that children can manipulate in various ways, teachers help children build organization and planning skills and develop their working memory.

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 4

Play: An Important Tool for Cognitive Development, continued

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Working Memory and Recall

The first component of executive function is working memory and recall, which is the abil-

ity to hold facts in one’s mind as well as being able to access them from one’s long-term

memory at any point in time (Dendy, 2008). In the HighScope preschool daily routine,

planning and recall times are opportunities for children to tap into their working memory

and articulate their ideas, choices, and decisions about what they want to do (planning

time), and remember and reflect on their work-time actions and experiences (recall time).

Planning builds children’s self-confidence and self-control while leading to more concen-

trated, complex play. Recall time exercises children’s capacities to form and talk about

mental images, helps them build their memory skills, and expands their awareness of time

outside the present. As presented in the diagram below, Gabrielle is exhibiting these func-

tions during her planning and recall.

Activation, Arousal, and Effort

The second component includes activation (getting started), arousal (paying attention),

and effort (finishing work). On a larger scale, this would apply to the whole plan-do-review

process. However, work time is the part of the day when children use these functions the

most because children are following through with their plans by getting the appropri-

ate materials, carrying through with their intentions while adapting to and solving any

1. Working Memory and Recall

Components of Executive Function in Gabrielle’s Play

2. Activation, arousal, and effort

3. Controlling emotions

4. Internalizing language

5. Taking an issue apart, analyzing the pieces, reconstituting and organizing it

Recalls what an elevator looks like and how to build one out of magnetic tiles.

Gets the materials needed to complete her plan.

Controls her emotions by not getting upset or showing frustration when the materials don’t work the way she wants them to. Uses “self talk”

during play as she manipulates the materials and pretends

Works out the problem with the magnetic tiles by using them in a different way.

Recalls the problem with the tiles and describes details of the stories about the dogs

Understands and uses basic concepts and roles of daily living.

Follows through with plan while adding to it and adapting to problems.

Listens to others’ ideas at recall.

Patiently waits for her turn at recall.

Talks to herself as she moves the dogs around, pretending.

The Importance of PlayIn its position statement on developmentally appropriate practice, the National Associa-tion for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) states, “Research shows that child-guided, teacher-supported play benefits children in many ways. When children play, they en-gage in many important tasks, such as developing and practic-ing newly acquired skills, using language, taking turns, making friends, and regulating emotions and behavior according to the demands of the situation. This is why play needs to be a sig-nificant part of the young child’s day” (Copple & Bredekamp, 2009, p. 328).

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 5

Play: An Important Tool for Cognitive Development, continued

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

problems that arise, and then completing the task. During work time, these functions are

used over and over again as children make new plans and follow through with them. As

presented in the diagram on p. 4, Gabrielle sticks with her plan throughout work time,

is highly engaged with pretend play, and solves problems and carries through with her

intentions until cleanup time. It is important to recognize that it takes purposeful play

for these cognitive functions to fully develop. Because their play is self-directed — and

therefore meaningful and purposeful to them — children are highly motivated to maintain

their engagement. Children who aimlessly wander around during free play are not exhibit-

ing the highest levels of complex play and strategizing needed to use and develop these

higher-level thinking skills. Likewise, when children’s play activities are directed by adults,

initiation (activation) is taken out of their hands, interest (arousal) is diminished, and

actions (effort) may be aimed at pleasing others rather than thinking about and learning

from their own experiences.

Controlling Emotions

The third component of executive function is controlling emotions, that is, the ability to

tolerate frustration and to think before acting or speaking. This is part of self-regulation.

Children with developed self-regulation are more able to control their emotions and be-

haviors, resist impulses, and exert self-discipline (Bodrova & Leong, 2007). Children who

participate in a consistent, reliable problem-solving approach (e.g., HighScope’s six steps

to resolving conflicts; Evans, 2002) learn to express strong emotions in nonhurtful ways;

appreciate their own views as well as the views of others; listen and discuss the details

of problems; recognize that when there is a problem, there are lots of possibilities for

solutions; and deliberate, negotiate, and collaborate with others while staying calm when

confronted with a conflict or a problem. When the magnetic tiles continued to fall down,

Gabrielle could have had an emotional “melt down” or shown strong frustration by kicking

at the tiles and walking away. However, due to her self-regulation skills, she stuck with the

task and solved the problem by building with the tiles another way. There is evidence that

some children who spend a significant amount of time using video games and watching

violent media programming imitate what they see, thinking these are acceptable behav-

iors, and do not know how to self-regulate when frustrated. These children may get angry,

even at the game itself (Anderson & Bushman, 2001).

Internalizing Language

The fourth component is internalizing language — using “self talk” — to control one’s

behavior and direct future actions. As adults, we internally talk to ourselves throughout

the day (e.g., to master problems, control emotions, and plan) — we just remind ourselves

Child-Driven Play

When children pursue play under their own impulse and initiative, they

• Practice decision-making skills• Discover their own interests• Engage fully in what they want to pursue

• Develop creative problem- solving skills

• Practice skills in resolving conflicts• Develop self-regulation• Develop trust, empathy, and social skills

• Develop language and communication skills

• Use their creativity and imagination

• Develop skills for critical thinking and leadership

• Analyze and reflect on their experiences

• Reduce stress in their everyday lives

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 6

Play: An Important Tool for Cognitive Development, continued

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Where Has Play Gone?

Many of us remember when we could go outside and play until the street lights came on or, in more inclement weather, when we played make-believe games with a friend in our bedroom or build things out of items we found lying around the house. Sadly, a daily time for children to freely choose what they want to do, whether indoors or outdoors, is in jeopardy. More and more, outdoor play is perceived as being too dangerous for children, so children are cooped up in their homes (Metro-com International, 2007). Both at home and at school, children are bombarded by television, DVD and computer games, violent toys that inhibit imaginative play, extracurricular activities, and academic pressure. Needless to say, little time is being allocated to creative play. Among the greatest threats to children’s creative play are television, video and DVD games, and computers. When children are mindlessly watching a screen, they are not engaging all of their sens-es. According to the Alliance for Childhood, children spend four-and-a-half hours per day involved in these activities (July 2009). Following a study connecting television watching with attention problems, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP; 2001) has recommended that young children — espe-cially those under three who are in the formative years of brain development — have no exposure to television, as a preventative measure against attention problems and subsequent risk of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Christakis, Zimmerman, DiGiuseppe, & McCarty, 2004). Yet studies cited by AAP and the White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity (2010) show 43% of children under age two watch television daily, and 90% of children aged 4 to 6 use screen media an average of two hours per day. A position statement by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), asserts that “research demonstrates that watching violent programs is related to less imaginative play and more imitative play in which the child simply mimics the aggressive acts observed on television” (The National Institute of Mental Health, 1982, as cited in NAEYC, 1994, p. 2). Furthermore, the majority of toys that children play with tend to be violent and expensive toys based on media pro-grams and which encourage children to reenact the aggressive behaviors they see on television, in commercials, or in movies. As children spend more time with media and items that promote violence, the less time they are engaged in activities that help them process violence. “Thus, as the need to work through violence increases, children’s ability to work it through can be seriously impaired” (Levin, 2007, p. 3). Another major threat to play is pressure to introduce academics. In Crisis in The Kindergarten (Miller & Almon, 2009), the authors argue that children are spending the majority of their day in literacy and math instruction and in standardized testing and test preparation, leaving less than 30 minutes (and sometimes no time at all) in play or choice time. The same restrictions and pressures are being placed on preschoolers. Research shows that the knowledge gained through this type of “cramming” and early pressure to learn ABCs and 123s fades by fourth grade (Miller & Almon, 2009).

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 7

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Play: An Important Tool for Cognitive Development, continued

not to talk back! With young children, private speech is key to these functions because

it helps the children direct their own actions; for example, what to do with their hands,

bodies, and voices, which in turn is part of developing self-regulation. Make-believe play

in particular is most helpful for the development of private speech. Alix Spiegel quotes

Laura Berk: “This type of self-regulating language…has been shown in many studies to be

predictive of executive function” (Berk as cited in Spiegel, 2008). Returning to the open-

ing scenario, as Gabrielle plays with the dogs, she uses private speech (internal dialogue)

as she directs the pretend play. Children who spend the majority of their time in teacher-

directed activities or watching television or computer screens — that is, listening to others

talk — miss out on opportunities to develop self-regulation through internal dialogue and

thought.

Complex Problem Solving

The fifth component of executive function is complex problem solving — taking an issue

apart, analyzing the pieces, and reconstituting and reorganizing it into new ideas. During

work time and small-group time, children are faced with many challenging problems as

part of carrying out their plans and completing tasks. Part of problem solving with young

children is helping them recognize that there is a problem and then involving them in the

process of finding a solution. When children are engaged and adults avoid jumping in and

solving problems for them, the children learn to rely on their own ideas and decision-

making skills and to see themselves as confident problem solvers. For Gabrielle, through

many experiences with magnetic tiles and solving problems, she needed no assistance in

solving the problem and coming up with a new idea to continue her plans. Children who

lack the experiences in play, and who spend most of their time in adult-organized activi-

ties, lack the creativity that it takes to solve problems mentally.

• • •

In summary, we as educators are entrusted with the responsibility of fully engag-

ing children’s minds and bodies in the way they learn best. By understanding the impor-

tance of play, how it helps to develop key cognitive functions, and what these functions are,

we can become more effective in protecting purposeful play and more intentional in our

interactions with children during their play. In this issue’s “Classroom Hints” article, we

will discuss strategies that assist in the development of execution function in young chil-

dren. However, most important, we must remember that play is simply about having fun!

Click here for entire newsletter

When adults are intentional in their interactions with children, validating their emotions and helping them find solutions to problems, children are better able to manage their own feel-ings and behaviors.

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 8

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Play: An Important Tool for Cognitive Development, continued

Shannon D. Lockhart, M.A., is a senior early childhood specialist with the HighScope Educational Research Foundation in Ypsilanti, MI. Shan-non has served as a national and international researcher; curriculum developer for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers; trainer; teacher; and educational consultant in the United States and abroad.

References

Alliance for Childhood. (n.d.). Time for play, every day: It’s fun — and fundamental. Retrieved July 23, 2009 from http://www.allianceforchildhood.org/sites/allianceforchildhood.org/files/file/pdf/projects/play/pdf_files/play_fact_sheet.pdf

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Public Education. (2001). Children, adolescents, and televi-sion. Retrieved May 13, 2010, from: http://aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/reprint/ pediatrics;107/2/423.pdf.

Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2001, September). Effects of violent video games on aggressive behaviour, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behaviour: A meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological Science, 12(5), 353–359.

Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. J. (2007). Tools of the mind: The Vygotskian approach to early childhood educa-tion. Columbus, Ohio: Pearson.

Christakis, D. A., Zimmerman, F. J., Digiuseppe, D. L., & McCarty, C. A. (April 2004). Early television exposure and subsequent attentional problems in children. American Academy of Pediatrics, 113(4), 708–713.

Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (Eds.). (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs: Serving children from birth through age 8. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of young Children.

Dendy, C. A. (February 2002). Executive Function…“What is this anyway?” Retrieved February 29, 2008, from http://www.chrisdendy.com/executive.htm

Evans, B. (2002). You can’t come to my birthday party! Conflict resolution with young children. ypsilanti, MI: HighScope Press.

ginsburg, K. R. (January, 2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and main-taining strong parent-child bonds. American Academy of Pediatrics, 119(1), 182–191.

Levin, D. (2007). Meeting children’s needs in violent times. In R. New & M. Cochran (Eds.), Early childhood education: An international encyclopedia. Westport, CT: greenwood Publishing group.

Metrocom International (Producer) for Michigan Television. (2007). Where do the children play? [DVD]. Ann Arbor: Regents of the University of Michigan.

Miller, E., & Almon, J. (March 2009). Crisis in the kindergarten: Why children need to play in school. Re-trieved March 27, 2009, from www.allianceforchildhood.org

Montie, J., Xiang, Z., & Schweinhart, L. (2007). The role of preschool experience in children’s development: Longitudinal findings from 10 Countries. ypsilanti, MI: HighScope Press.

National Association for the Education of young Children (July 1994). Media violence in children’s lives. Retrieved February 29, 2008, from http://www.naeyc.org/positionstatements

Ouellette, J. (October 16, 2007). The death and life of American imagination. The Rake: Magazine. Re-trieved July 28, 2009, from http://www.secretsofthecity.com/magazine/reporting/features/death-and-life-american-imagination

Packer, L. (December 9, 2004). What are the executive functions? Retrieved July 23, 2009, from http://www.schoolbehavior.com/conditions_edfoverview.htm

Shore, R. (2003). Rethinking the brain: New insights into early development, revised edition. New york: Families and Work Institute.

Spiegel, A. (February 29, 2008). Creative play makes for kids in control. Retrieved February 29, 2008, from http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=76838388

Tippet, K. (host and producer). (24 July, 2008). Play, spirit, and character. [interview]. Speaking of faith. [Radio broadcast]. St. Paul, Minnesota: American Public Media.

United Nations High Commission for Human Rights. (20 November 1989). Convention on the rights of the child (resolution 44/25). New york: Author.

White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity. (2010). Solving the problem of childhood obesity within a generation: Report to the President. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved May 12, 2010, from http://www.letsmove.gov/tfco_fullreport_may2010.pdf.

Zelazo, P. D., Muller, U., Frye, D., & Marcovitch, S. (2003). The development of executive function. Mono-graphs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Volume 68.

Yesterday, a number of children had difficulty staying engaged in large-group time. The teach-ers decided that it was not active enough and took too long. Today, the teachers decide to use the “freeze song” to help children understand where their bodies are in space and to give them opportunities to connect the words they use to the actions they perform to the music. As the music plays, the teachers imitate children’s actions. At certain points, the music stops, or “freezes.” At one point when the music stops, a teacher says, “Jamie, how should we make our bodies freeze?” Jamie says, “Touch your back.” The teacher says, “Everyone stop your bodies and touch your back.” Then the music starts again and children and teachers freely move their bodies. From this activity, children begin to learn how to control their bodies and actions, which in turn helps them to regulate their thoughts and feelings. At first, children will still move their bodies to the “freeze” parts, but once they have had more experiences with this start-and-stop action, they will become suc-cessful.

The scenario above illustrates how adults can help children develop

key cognitive skills (see “What Is Executive Function” in the feature

article). Teachers who are knowledgeable about self-regulation and

executive function are able to plan numerous activities that support

children in learning how to put words to their actions and control

their bodies. By setting up the classroom environment and the daily

routine for active learning, and by planning intentional interactions

with children, teachers help children to develop working memory,

self-regulation, internal language, and organization, planning,

and initiating skills, as well as other important cognitive abilities.

Next, we will look at ideas and strategies for planning the learning

environment, the daily routine, and intentional interactions to help

develop children’s executive function.

Planning the Learning Environment

Stable learning areas. By strategically arranging and organiz-

ing the classroom with stable learning areas (e.g., house, block, art,

book, and toy areas) and by stocking these areas with appropriate

open-ended materials (e.g., dishes, wooden blocks, paints), we begin

to help children see an organization in their environment upon

which they can rely. Children can then easily categorize and classify

information about their room and use this information to plan and

recall as well as carry out their intentions during work time. An or-

ganized learning environment also helps children who have trouble

regulating their emotions, in that it provides consistency in their

everyday lives.

Visual Supports. You can also create visual supports for children

and place them in the classroom where children can easily see and

use them. For example, you can make a pictorial daily routine chart;

a sequence chart that shows a step-by-step process for a task such

as washing hands; and social stories, which are simple drawings

illustrating classroom problem-solving scenarios, such as what to do

when one child accidentally knocks over another child’s block tower.

Timers (e.g., oven timers or homemade sand/salt timers in differ-

ent sizes) help children gain a sense of time and are often useful in

helping children resolve issues that arise during play, such as those

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 9

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Planning Assists Children’s Executive FunctionBy SHANNON LOCKHART

CLASSROOM HINTS

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 10

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

dealing with sharing and turn-taking. You can also use sign language

and make sign-language cards for children to view, and for children

who are having difficulty knowing where to place their bodies during

an activity, you can use visual markers such as carpet squares or

hula hoops.

Materials. Provide a variety of materials that support executive

function. For example, different types of small manipulatives (rocks,

shells, and shapes; small replicas of people, animals, and cars) lead

to children’s pretend play and the development of self-talk. Natural,

found, and recycled materials lend themselves to open-ended play,

including complex play, such as when children pretend “restaurant”

using sheets of paper for menus, yellow sponges and rocks for food,

and dishes. Dramatic play props also contribute to cooperative play

in which children negotiate roles, act out scenes, and problem-solve

situations.

One rule of thumb is to provide some but not all the props for

dramatic play scenarios, so that children tap into their imagination

and creativity to seek various materials from the different classroom

learning areas for making their own props.

Another suggestion that helps with self-regulation — as well

as reducing the number of conflicts within the children’s day — is

to have multiples of popular toys and materials. To enlist the full

range of children’s perceptual and cognitive abilities, these materials

should appeal to all of children’s senses (e.g., things made of metal;

objects having different textures; heavy objects such as small and

large wooden blocks; and sand and water).

Planning the Daily Routine

The overall routine. By providing consistency and opportuni-

ties for active learning, the overall daily routine plays an important

role in how children express their emotions; pay attention; and

solve complex problems, both those having a social basis and those

involving materials. Each part of the routine provides active learning

opportunities and allows for child choice — even when tasks such as

cleaning up have to be done.

It is also important to limit the number of transitions but to

plan for the transitions that are needed. For example, warn children

when a transition is approaching. This develops their ability to antic-

ipate events and plan accordingly. In addition, give children choices

(control) about what to do during transitions. When possible, ask for

and use children’s ideas about what to do during transitions.

When changes take place within the routine, such as when a

teacher is absent or a special guest is visiting, report these to chil-

dren by using a message board with simple drawings or by playing

guessing games. These strategies further give children a sense of

control over their day and allow them to anticipate events.

The transition from home to school can set the whole tone of

the day for a child and determine how much he or she will partici-

pate. Therefore, teachers need to help parent-child partners estab-

lish consistent morning rituals that children can trust in. Children,

like adults, find it easier to regulate their emotions when they know

what to expect and are reassured their needs will be met.

Plan-do-review. The plan-do-review sequence is an important

process that assists in the development of working memory and

recall as well as the other cognitive functions discussed in the lead

article. However, there are a few other strategies you can use to sup-

port children’s self-regulation and internal language: hide-and-seek

games; games that require children to stop and think (e.g., a modi-

fied Simon Says game without winners and losers, or a freeze song

with actions, as illustrated in the opening scenario); made-up stories

for children to act out; and large-group times in which children have

the opportunity to talk about what they are doing and to release

energy by stomping, jumping, twisting, bending, and squatting.

Classroom Hints, continued

Planning Intentional Interactions

Intentionally plan for activities that support executive function

and self-regulation throughout the daily routine. In this regard, it

is especially important to allot enough time for child-driven play

(45–60 minutes). During this time, which is called work time in the

HighScope Curriculum, play as a partner with children and follow

the children’s leads. You can facilitate children’s developing executive

function abilities by taking on roles assigned to you by the children

and modeling role playing without taking over the play. Model the

kind of language used in self-talk, or private speech, by telling chil-

dren what you are doing (e.g., “I’m going to wash off the table first

and then sit down in my seat for recall”). Additionally, when conflicts

or problems arise, implement the six steps to problem solving:

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 11

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Classroom Hints, continued

The Six Steps to Conflict Resolution

Step 1: Approach calmly, stopping any hurtful actions.Step 2: Acknowledge children’s feelings.Step 3: Gather information.Step 4: Restate the problem.Step 5: Ask for ideas for solutions and choose one

together.Step 6: Give follow-up support as needed.

For more information, see You Can’t Come to My Birthday Party!

Conflict Resolution With Young Children, by Betsy Evans (HighScope Press, 2002).

Using the six problem-solving steps specifically helps children

develop self-regulation as well as what is called “other-regulation.”

According to Bodrova and Leong (2007), children engage in other-

regulation before developing self-regulation. That is, they learn

about their own behaviors through recognizing and assisting in

the change of others’ behaviors. Take, for example, a child who has

difficulty taking turns. By placing that child in charge of the sand

timer, when other children have a problem with taking turns,

she can suggest using the sand timer. With repeated experience

in this role, she will understand that she can use the timer as

well and may have fewer emotional outbursts.

Another suggestion offered by Bodrova and Leong to help

children develop other-regulation is to plan experiences in

which children have to identify mistakes in the teacher’s work

or in written information — for example, to deliberately make

mistakes on the message board that children can correct, such

as the block symbol drawn in for the art area, or when copying

the movement of a child acting as leader during large-group

time. Children then see the adults as well as other children mak-

ing mistakes and can help correct them. When they do this, they

begin to internalize strategies for self-regulation when involved

in conflicts. By correcting adults who did not write on the mes-

sage board correctly or who miscopied an action, they begin to

see themselves as competent problem solvers.

• • •

By intentionally planning the classroom learning environment,

the daily routine, and our interactions with children, we can do

a great deal to support young children’s developing executive

function and self-regulation skills!

Click here for entire newsletter

Alyia happen because

adults do not understand

their role in play develop-

ment and intervention

and how IEP goals can be

met within the context of

children’s play.

When children have a

developmental delay or

a disability, we provide

interventions to close

the gap, regardless of

the delay or disability.

Considering a child’s

delay in language, social

development, physical

development, or cognitive

development, for example, doesn’t it make sense that allowing the

child more time to explore materials and people would help close

the gap? The research does, in fact, support this strategy. It is also

important to remember that adult support to the child is key.

For instance, if a child is delayed in his or her social development,

we would provide opportunities for the child to practice interact-

ing with peers, and we would do so through the support we give the

child within the context of the experience. So, for example, if Tomas

is reluctant to join a group of other children, we might imitate what

he does as he plays by himself a few feet away from the group and

then model how he might join in with the others. But when we pull

children away from natural opportunities to practice interacting

with peers and receive adult support in that context, we tend to send

a message that their choices and interests are not important.

As explained in the lead article, there is a growing body of evi-

dence supporting the many connections between cognitive develop-

ment and play initiated and sustained by children. Additionally, play

supports the development of language and social-emotional regula-

tion. So, as educators of young children with or without disabilities,

we need to recognize children’s ability to use play as an avenue to

learning and generalizing new skills or concepts. Therefore, play

with adult scaffolding — that is, supporting children at their cur-

rent developmental level and introducing new materials and gentle

challenges as children are ready — is an intentional intervention.

The support the adult gives to Tomas, above, is an example of this

approach.

At planning time, Alyia points to the picture of the sand and water table. Today in the table there is water and dish soap. Children have been washing a variety of materials such as plates, cars, and Legos. After Alyia points to the picture, her teacher comments, “Alyia, I see you pointing to the water table. You must want to wash today.” Alyia looks at her teacher and moves over to the water table and finds an item to wash. She is fascinated by the bubbles cre-ated by the dish soap and picks some up in her hand and lets them fall back in the water. About seven minutes pass, and an adult comes over to tell Alyia that she needs to come work with her but that Alyia can come back in a few min-utes. Alyia resists moving away from the activity she has just chosen but reluctantly complies as the adult negotiates with her. After several min-utes of working together, the adult continues to insist that Alyia stay, even though Alyia tries to indicate she is “finished.” After about 15 min-utes Alyia is released to go back to her choice of activities. Alyia does not return to the water table but moves about the room, searching for someone or something to engage with.

Whether it is playing in the block area with the plastic airplanes or

dressing the baby dolls, young children with disabilities can often

have difficulty maintaining engagement in play scenarios because

teachers and programs do not fully support uninterrupted free-play

time. In this article, we will look at why this is so and how adults can

support children’s free play.

Both HighScope and the National Association for the Education

of Young Children (NAEYC) recommend that children have at least

one hour of free play in a half-day session. Children with special

needs receive the same benefit — if not more — from this uninter-

rupted time to engage with materials and people of their choice.

Most early childhood classrooms that are inclusive or are de-

signed for children with special needs proclaim that play is central

to their program. Yet, in my experience, play time (work time in

the HighScope Curriculum) is often when adults pull children out

of their play to work with them in a directive way or to work on IEP

goals. I believe scenarios such as the one of the adult working with

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 12

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Play — An Intentional Intervention!By TERRI MITCHELL, HIgHSCOPE FIELD CONSULTANT AND EARLy CHILDHOOD ADMINISTRATOR, CANyONS SCHOOL DISTRICT, SANDy, UTAH

SPECIAL EDUCATION

When children are allowed to make choices and follow through

on their choices, with adult scaffolding children are much more likely

to maintain a topic in conversational turn taking; use and pretend

with materials; and initiate or invite others into their space. Choice

promotes self-confidence and self-control and leads to more focus,

concentration, and play. However, when adults pull children aside

to directively teach them — for example, about vocabulary, shapes,

or counting — they send the message that the adult’s agenda to com-

plete a specific task is more important than the child’s choice. We can

avoid sending this message by providing time, allowing for choice,

and engaging with children using appropriate interaction strategies.

That is, we can scaffold children’s learning in the context of their cho-

sen play rather than taking them away from their free-play activities.

Scaffolding in the Context of a Child’s Chosen PlayThe sample work-time scenario with Nathan (a teacher) and Hayden,

below, illustrates how supportive interaction strategies in the context

of children’s play create conditions for successful interventions with

young children.

Nathan and Hayden are in the block area. Hayden, who uses only a few words, typically moves from area to area with little intention to play and with low engagement with materials. Nathan notices as Hayden picks up a small plastic airplane and begins to move it around in the air. Nathan chooses to move a bit closer and picks up another nearby plastic airplane. Nathan begins making airplane noises. Hayden pauses the movement of his plane. Nathan states, “Plane flying!” Hayden begins to move his plane again. “Plane up…plane down,” says

Nathan as he flies his plane closer to Hayden’s space. Hayden smiles and begins to imitate the up-and-down motion with Nathan, who says, “My plane is going to land… (making plane sounds) down, down, down…stop.” Hayden stops to watch, then runs off to another area.

In this intervention scenario, Nathan scaf-folds Hayden’s learning in the context of Hayden’s play by imitating Hayden and then expanding on Hayden’s play (by making plane sounds), and fi-nally commenting on his own actions. This drew Hayden, even for a short while, into a beginning play scenario. This intentional intervention was specifically designed to support Hayden’s IEP goals of language development, initiative, and time on task. The anecdotal notes that Nathan might now write could include the amount of time Hayden engaged with Nathan and/or any lan-guage, sounds, or gestures Hayden used. In the next intentional intervention, Nathan may choose to comment on Hayden’s actions.

Adults can support children’s play by providing comments that

assist children in maintaining focus on the play, as Nathan did in the

scenario above. Adults make the comments, but they do so without the

expectation of a response from the child. The goal of this type of inter-

vention is to simply support the child in maintaining focus and expand-

ing upon his or her play, not to direct the play in any particular way.

• • •

Interaction strategies such as commenting, imitating, expanding on

children’s play, and repeating and rephrasing what children say are all

adult scaffolding strategies that help young children with disabilities

progress. We can also use them as part of intentional interventions

with young children as we validate children’s interests.

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 13

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Special Education, continued

Click here for entire newsletter

Terri Mitchell is a HighScope field consultant and cur-rently serves as the Early Childhood Administrator in Canyons School District in Sandy, Utah. Prior to join-ing Canyons, Terri was an educational specialist for the Utah Personnel Development Center, where she directed the training initiatives for early childhood special education classrooms across the state of Utah. Terri is a certified teacher in special education and early childhood special education. She has con-tributed her experience with instructional coaching, assessment, and systems change to the development of several high-quality early childhood programs.

This two-hour workshop is designed to inform teachers about what

executive function is and how they can support it through children’s

play. The objectives of this workshop are to enable practitioners to

(1) discuss the importance of play in children’s development;

(2) define executive function; and (3) identify intentional strategies

to assist in the development of executive function in the classroom.

What You’ll Need: Chart paper (Opening Activity and Central Ideas

and Practice); handout made from the sidebar in the feature article

titled “Child-Driven Play” (Central Ideas and Practice); pictures of

children at play (Central Ideas and Practice); definition of executive

function and the five components from the feature article (Central

Ideas and Practice); Initiative and Social Relations Key Experience

DVD — segment on power belts or footage of children involved

in pretend play or complex play and/or solving problems in play

(Central Ideas and Practice); executive function card game (make

by listing each of the five components of executive function on a

separate colored card, and make a set for each table; (Central Ideas

and Practice); support strategies from this issue’s “Classroom Hints”

article (Central Ideas and Practice).

Opening ActivityFavorite Activity

(15–20 minutes)

1. Have participants individually think about a favorite activity or

something they love to do and then share it with others at their

table while discussing the following questions:

• Why is this your favorite activity?

• What are some skills you learn from this activity?

• How does this activity support your knowledge, development, or

other aspects of your life?

2. After about 10 minutes, discuss participant answers as a whole

group. What will emerge from the discussion is that the activi-

ties people tend to love the most are those they choose to do, feel

confident doing, and are intrinsically motivated to engage in.

When they are the ones making choices and decisions about their

time and the activity, then they tend to be more engaged, they

learn new skills or hone existing skills, and they want to repeat the

activity — which in turn helps them become more confident and

successful. These are activities they find fun and interesting.

On chart paper, list the five factors of intrinsic motivation: enjoy-

ment, interest, sense of control, probability of success,

and feelings of competence and self-confidence (High-

Scope Educational Research Foundation, 2010). Emphasize that

play is what children do best!

Central Ideas and PracticeWhat Is So Important About Play?

(15–20 minutes)

3. Have participants form small groups. Pass out pictures of

children at play to each group. As participants look through the

pictures, ask groups to discuss why play is important to children’s

development. Create a master list by recording their answers on

chart paper.

4. Compare the list created in step 3 to the main points and sidebar

from the lead article. Be sure to emphasize that play is simply

about having fun! Summarize by explaining that play is vital to

children’s learning and that it is key to the development of execu-

tive function.

What Is Executive Function? (40 minutes)

5. Define executive function using the definition in the feature

article. Explain that executive function encompasses key cognitive

skills that children need for success later in school, and that even

very young children can begin developing these skills. Mention

that the more that we as teachers know about executive function,

the more effective we can be in helping children develop these

skills.

6. Discuss the five components of executive function as presented in

the feature article. Use the example of Gabrielle’s play from that

article or use examples from your own experiences with children.

7. Show the Initiative and Social Relations Key Experience DVD

segment on power belts and ask participants to look for the five

components of executive function as children are playing and

problem solving. Discuss responses as a whole group.

8. Pass out the executive function card game sets to each group

and have group members spread the five component cards out

across their tables. Then, using the pictures of children at play,

have the participants place the pictures under the component that

best describes what children are doing and learning. Have them

discuss why they chose that component. (Note: The play depicted

in the pictures may illustrate more than one component, but have

participants just choose one). Once all groups have completed the

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 14

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Supporting Executive Function in Children’s PlayBy SHANNON LOCKHART

TRAINER-TO-TRAINER

matching, have group members choose one picture and explain

the component to the whole group.

How Do We support Executive Function?

(25 minutes)

9. Divide participants into three groups. Assign each group one of

the following topics:

• Environment support

• Daily routine support

• Interaction support

Ask groups to come up with ideas that would support children’s

development of executive function according to their topic.

10. Once groups have finished, have each group present its group

members’ ideas. Compare their lists with the main points

presented in this issue’s Classroom Hints article, discussing any

strategies that were not covered.

Application Activity (10 minutes)

11. Together with the others in their group, have group members list

some strategies that will support the development of executive

function with the children in their own program.

Implementation Plan (5 minutes)

12. Have individual participants use the list from the application ac-

tivity to develop a plan of action for implementing these strategies

in their classroom.

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 15

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

Trainer-to-Trainer, continued

Click here for entire newsletter

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 16

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

NEWS BRIEFS ASK USBy SHANNON LOCKHART, M.A.

A child in my classroom is having a difficult time

following through with routines. He tends to

wander or run around at recall or snacktime and

does not follow through with what he is sup-

posed to be doing. This is very frustrating to the

teachers and disruptive to the class. Do you have

any suggestions on how to help him?

— A Preschool Teacher

The first suggestion is to make sure that you are follow-

ing a consistent daily routine and that the child knows all

about the routine. One way to make the routine concrete

for this child is to display it pictorially on the wall, so he

can see and refer to the daily routine segments through-

out the day. Another

way would be to get

pictures of this child

during each part of the

day and put them in

a small photo album

that he can look at

in the classroom

and with his parents

at home. This will

help build the child’s

memory of what takes

place first, second,

third, etc., and how

he is involved in each

part of the day.

The second suggestion

is to make sure that

you are incorporating

active learning. Take a

look at your routine and determine what parts of the day

the child is having the most difficulty with. Then deter-

mine if all the ingredients of active learning are present

(materials, manipulation, choice, child language and

thought, and adult scaffolding). If he is not being allowed

to make choices, this can lead to his not wanting to par-

ticipate because his interests are not being challenged.

For example, if he never participates in large-group time,

which is active and engaging, you could give him two

Introducing a new scoring level for the OnlineCOR!

We are very excited to announce that a new scoring level for

our OnlineCOR, preschool version, is now available. Based on

research that we have been conducting during the last year, as

well as in response to customer feedback, we will have a Level O

option available for OnlineCOR, preschool version, in addition to

the existing Levels 1–5. This feature has been research-validated

and will be especially helpful when assessing children who have

not yet met Level 1, and for children with special needs. For more

detailed information about this new Level O, and the research

supporting it, please click here.

Need a jump-start on your plans for large- or small-group times this fall? HighScope’s Ideas From the Field can help!

Ideas From the Field is a place where real teachers share their

favorite activities for large- and small-group times. We choose

the most innovative plans teachers send us and then post them

in an easy-to-follow format on HighScope’s Forums so that you

can quickly go from looking at an activity online to adapting it for

your classroom. Ideas From the Field is updated on a regular ba-

sis, so be sure to check back often to see a fresh idea for a teacher-

tested activity that you can use in your classroom (see our latest

Ideas From the Field now)

Save the date!2011 HighScope International Conference Plan to join us in Ypsilanti, Michigan, May 4–6, 2011, for this

popular annual event! Watch our Web site for details at

highscope.org as more information becomes available.

Click here for entire newsletter

VOLUME 24, NO. 3 • page 17

HIGHSCOPE | Extensions

ASK US, CONT.

choices that you can live with. For example, you might say,

“If you don’t want to participate in the group, you can stay

at the table or you can get a book to look at, but it is not a

choice to play with the toys during large-group time.” Be

consistent about following through with whatever choices

you are giving him.

A final suggestion: If the child is having problems following

routine tasks like getting ready for mealtimes or going to

the bathroom, then you may need to make a step-by-step

pictorial sequence of what he is supposed to do so he can

remember each part of the routine task. Children who have

problems with self-regulation and executive function are

often unable to remember each part of a simple task. They

only remember the last thing you told them. For example,

for washing hands you could take photographs of the child

(1) turning on the water, (2) wetting his hands, (3) rubbing

soap on his hands, (4) rinsing the soap off his hands, (5)

turning the water off, (6) getting a paper towel, (7) throwing

the paper towel away, and (8) going to the table for snack.

In this sequence, the child learns how to follow each step

so that he knows what he is to do with his body during this

time. After reviewing this repeatedly, these steps will even-

tually become a habit for the child and will be internalized

in his long-term memory.

Ann S. Epstein, PhD, is Senior Director of Curriculum Devel-opment at HighScope and is the author or coauthor of numerous research and cur-riculum publications, includ-ing The Intentional Teacher: Choosing the Best Strategies for Young Children’s Learning (published by the National Association for the Education of Young Children).

Click here for entire newsletter