If I am to be remembered. The life and work of Julian Huxley with selected correspondence: By Krisna...

-

Upload

anne-baker -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of If I am to be remembered. The life and work of Julian Huxley with selected correspondence: By Krisna...

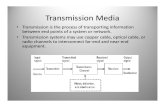

inception to the explosion of the bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In particular, they show how the teams of scientists and engineers tackled the many problems they faced in such a new field of research: at the start so much was unknown beyond the basic principle. It is a detailed, technical account that will best be appreciated by physicists, chemists, and engineers who have worked in research. They will most readily appreciate what it meant to have more or less unlimited support for a project that began in people’s minds as requiring perhaps two dozen physicists and an equal number of support staff to one that finally employed some 3000 technical workers.

Christine Sutton

Sir Jonas Moore. Practical Mathematics and Restoration Science. By Frances Willmoth. Pp. 244. Boydell Press. 1993. Hardback f35, US $63 ISBN 0 851 153216.

As well as being a careful reconstruction of the life of Sir Jonas Moore, this book provides a wealth of contextual detail, including life in early seventeenth century Lancashire; the problems faced by mid-century publishers and sellers of mathematical books; a brief history of the drainage of the Fens; the development of printed carto- graphy; attempts to build a defensible harbour in Tangier; and science in Restoration London. But the main story, told with clarity and learning, is of a determined individual who, sometimes against the odds, carved out a place for himself as a theoretical and practical mathematician during a period both of political uncertainty and of con- tention over the nature and use of mathematics. Willmoth weaves together a convincing account from an impressive range of sources, clearly identifying Moore as the champion of a unitary mathematics, integrating the theoretical and the practical.

In style the book is sometimes slightly truculent, particularly when referring to the contributions of, or omissions by, other historians. Nevertheless historians of mathematics, instruments, astron- omy, technology, and Restoration science among others will all find something of interest and value in this comprehensive biography.

M. E. W. Williams

Learning from Mt Hua. By Kathlyn Maurean Liscomb. Pp. 229. Cambridge University Press. 1993. f50 ISBN 0521 41112 2.

Biographical information about Wang Lti (Li) is sketchy. He was probably born in 1331, supposedly from a family of physicians, when China was under Mongol rule, but lived to see home rule established under the Ming dynasty in 1368. He died co. 1391. He was one of the leading physicians of his day and probably studied under Zhu Zhenheng (1281-1358), perhaps the most renowned of all Chinese doctors. He travelled widely to sit at the feet of other teachers. Of his writings only a collection of critical essays on medical ethics survives, but he is known to have written also books on astronomy, geomancy, and other topics.

Such biographical details as are available are

fully pursued and critically annotated, but the emphasis is on Wang’s other passion, that of landscape painting, which he indulged freely on his travels. In particular, he became fascinated by Mount Hua, the scenically magnificent sacred mountain of the west, which acquired for him a mystical significance. His style was highly individualistic and he followed no recognized school. This book reproduces and comments on some 50 paintings from his Mount Hua Album - eight of them in delicate colour - and a translation of, and commentary on, Wang’s own preface to it.

A delightful book: meticulously researched and written by a specialist on Ming art with a clarity of style that will appeal to scholars and general readers alike.

Trevor I. Williams

If I am to be Remembered. The Life and Work of Julian Huxley with Selected Correspondence. By Krisna R. Dronamraju. Pp. 294. World Scientific Publishing, Singapore. 1993. ISBN 9 810 21142 2.

In 1970 Sir Julian Huxley, who died in 1975 at the age of 88, wrote, ‘I seem to have been possessed by a demon, driving me into every sort of activity and impatient to finish anything I had begun’. Huxley, grandson of T.H. Huxley and great-grandson of Thomas Arnold, began his career as an academic biologist, but after he became secretary to the Zoological Society of London in 1935 he led an increasingly public life, culminating in his appointment in 1946 as the first Director-General of UNESCO. He became known to a wide public as a populariser of science, first in his collaboration with H.G. Wells and his son G.P. Wells in ‘The Science of Life’, and later in his appearances on the Brains Trust for the BBC. He was well-known as a humanist, believing that man alone, because of his control of the environ- ment, would be in control of evolution.

This book is interesting for the letters, selected from the collection of Huxley papers at Rice University, Texas, but the absence of an index to the letters is a drawback, as is the lack of an adequate index to the book as a whole. The first half of the book is a summary of Huxley’s life and career, but in 170 pages Dronamraju can only begin to cover the many aspects of Huxley’s life, a problem that he acknowledges in his preface. No full-length biography exists: Ronald Clark devotes small sections of ‘The Huxleys’ (1968) to Julian Huxley, but Huxley’s own two-volume autobiography, ‘Memories’ (1970 and 1973) remains the fullest account. Dronamraju’s book adds little to what has already been written, and it is time that a proper biography appeared, perhaps written by a scientist who writes as well as Huxley did himself.

Anne Baker

Non-verbal Communication in Science Prior to 1900. Edited by Renato G. Mazzolini. Pp. 620. Leo S. Olschki, Florence. 1993. Paperback. Lire 98ooO. ISBN 88 222 4069 3.

Archaeologists and prehistorians are accustomed to rely heavily on artifacts - ranging from arrow

heads to foundations of buildings - to inform their inquiries. In contrast, historians of science - interested largely in the period subsequent to the introduction of printing - are mainly con- cerned with written material. This book, the proceedings of a IUHPS conference held in Trento in October 1991, is a compelling reminder that we can all learn much from non-verbal sources. It comprises some 20 lectures, delivered by distinguished scholars. The themes range widely, from representations of animals and plants recently extinct to portraits of machines in fifteenth century Siena; the Gottingen collection (mostly instruments) of perinatal medicine to Victorian illustrations of palaeontological scenes; illustrations of seventeenth and eighteenth century textbooks of natural philosophy to laboratory design and the nature of physics.

These Proceedings differ in two important respects from most such works. First, apart from the usual trappings of scholarship - copious references, footnotes, etc. - it is profusely illustrated in both black-and-white and colour. Many of the illustrations derive from specialist collections and so will not be generally familiar. Second, there is a comprehensive (eight-page) index of names mentioned in the text: too often with such works it is difficult to relocate a topic noted in an earlier reading. The modest binding belies the treasures within; the organisers did well to concentrate their resources on the latter. Altogether one of the most interesting and stimulating books of its kind that has come my way for a long time.

Trevor I. Williams

Defining Science: William Whewell, Natural Knowledge and Public Debate in Early Victorian Britain. By Richard Yeo. Pp. 280. Cambridge University Press. f35, US $54.95 ISBN 0 521 43182 4.

‘Science was his forte but Omniscience his foible.’ Chiefly remembered as the target of this quip by Sydney Smith, William Whewell (1794-1866) was a Lancastrian who spent his entire career at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he served as Master from 1841. His sometimes rude and over- bearing manners may well have been a cloak to disguise his low-born social origins, for he was the son of an artisan and he married into ‘trade’. Significantly, he remarked on meeting the French physicist, J.B. Biot, that his ‘bad English and false accent’ made him feel superior.

Yeo’s fascinating book is, however, not a biography but an essay in Victorian ideas about science and culture. In this respect, Yea interprets Whewell not as a statesman of science, but as its ‘metascientific critic. ’ In 1834 Whewell coined the word ‘scientist’ for those who sought know- ledge of the material world, while between 1837 and 1840 he pioneered the critical study of the history and philosophy of science in five large volumes. Yeo shows how this literary activity related to Whewell’s anti-utilitarianism, his concern for the moral integrity of science, and to his far-reaching influence on liberal education. This is intellectual history at its most readable.

W. H. Brock

47

![Krisna Temple At Tornto Canada[1]](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/58f331841a28abe0628b45c3/krisna-temple-at-tornto-canada1.jpg)