'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

-

Upload

dorjeblueyondercouk -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of 'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

-

7/29/2019 'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

1/8

Studies in Musical Theatre Volume 3 Number 3 2009 Intellect Ltd

Article. English language, doi: 10.1386/smt.3.3.285/l

'I had a dream': 'Rose's Turn', musical

theatre and the star effigy

Jason Fitzgerald Yale College

Abstract

7 had a dream' analyses the climactic 'Rose's Turn' number, from Gypsy, in

the experience of live performance. Applying Joseph Roach's concept of the, celeb-

rity effigy and Scott McMillin's theorization of the musical's dual temporality,

Fitzgerald argues that, first, the book musical presents a fictive, world in which

non-celebrities rise to the, level of effigies and, second, that 'Rose's Turn' is Momma

Rose's attempt to turn that fiction into reality by superseding the celebrity pres-

ence of the, actress playing her.

Keywords

Gypsy

effigy

celebrity

Rose's Turn

Patti LuPone

identity

Every major production o Gypsy that Arthur Laurents has directed, begin-

ning with the 1973 London revival starring Angela Lansbury, culminates

in a disturbing dramatic trick. As the inevitable standing ovation for the

climactic number 'Rose's Turn' dies down, the actor playing Rose contin-

ues to bow, and she does not stop until she hears her daughter Louise

behind her, clapping her own hands at her mother's private histrionics.

Stephen Sondheim recalls the first time he saw this sequence in the thea-

tre: 'There was dead silence in the house, and she kept bowing. You real-

ized that you were looking at a mad woman, not at a musical' (quoted in

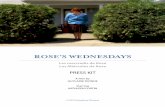

Garebian 1994: 122).My own experience of this staging was slightly different but equally

haunting. After Patti LuPone's performance of 'Rose's Turn' in the 2007

Encores! revival of Gypsy, which later became the fifth Broadway incarna-

tion of the show, I rose out of my seat and applauded - not dutifully, but

ecstatically - with the rest of the audience. When I realized that LuPone's

bowing was not motivated by our applause, however, I was stunned not

so much at Rose's madness as at my own. Laurents's directorial virtuosity

had caused an unsettling semiotic switcheroo: one moment I was an inno-

cent Patti LuPone fan, another moment I was a part of Momma Rose's

fictional world, an audience member who lived only in her head, and

therefore a cast member in her schizophrenic dream. As Louise (played by

Laura Benanti) walked onstage, I felt as 'caught' and as naked as Rose

herself. Confused (and returning, sheepishly, to my seat), I found myself

asking the same questions as she: 'Why did I do it? What did it get me?'

This essay is my first attempt to account for the uncanny quality of this

experience, in which I found myself on the other side of the divide between

'musical' and 'madwoman'.

Until its conclusion, 'Rose's Turn' seems to operate like any other musi-

cal show-stopper. A show-stopper, being one of those rare words that

-

7/29/2019 'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

2/8

means what it says, pauses the procession of the narrative fiction.

During a show-stopping performance, the audience experience more

closely resembles that of a concert than a musical play: there is no con-

cern for plot, character or circumstance, merely the appreciation of a

performer executing athletic vocal and/or physical feats, which are

rewarded with applause if they impress. Typically, these pauses are brief,

and they do not threaten the musical's ability to continue unravelling

thefiction

of its plot. 'Rose's Turn', however, is different. Once the song

is over, there is not another note of sung music in Gypsy, and the play

wraps itself up in haste. In the brief scenelet that follows the number,

Rose is a changed woman, shrugging off the drive for stardom - 'If I

coulda been, I woulda been' (Laurents et al. 1994: 107) - that had been

untameable only moments ago. Roles reverse as Louise becomes mater-

nal and Rose childlike and vulnerable. It would be unthinkable, with

Momma so deflated, to have so much as another scene change, never

mind another musical number. The wind has gone out not only of Rose's

sails but of Gypsy's.

The 'wind', in this case, is the ability of ordinary people to rise to the

level of the star. That the musical stage gives any character-

even the

plain, talentless older sister of Dainty June, let us say - the power to inhabit

the rarefied air of the celebrity, to possess what Joseph Roach (2007) has

playfully dubbed it', is the faith that defines Momma Rose and the musi-

cal she belongs to. It is in 'Rose's Turn' that she puts that faith to the

ultimate test, by trying to eliminate the boundary between character and

performer and, in so doing, turn the musical theatre's star-making power

upon herself. Her failure marks the collapse of the system of illusions that

makes the musical theatre possible.

Though Roach discusses what he calls 'It', 'a certain quality, easy to

perceive but hard to define, possessed by abnormally interesting people'

(Roach 2007: 1), in relation to historical persons, predominantly actors

and political figures, his theories apply to the characters in the fictional

world of Gypsy. Indeed, to become a 'star' - to grab hold of 'ft' - is the

Aristotelian action of this musical, in which each character is defined by

his or her distance from that condition. Among the many qualities Roach

ascribes to 'It' is the ability of the possessor to split, like a Renaissance

English king, into two bodies, 'the body natural, which decays and dies,

and the body cinematic, which does neither' (Roach 2007: 36). The 'body

cinematic' operates as an effigy, 'an image [...] synthesized as an idea' that

is 'not reducible to any single one of the materially circulating images of

the celebrity, but nevertheless generally available by association when

summoned from the enchanted memories of those imagining themselves in

communication with the special, spectral other' (Roach 2007: 1 7). The

endurance of the 'body cinematic', or effigy, beyond the physical life of the

celebrity was a foundational component of divine kingship, and it remains

a paradox of celebrity - one may die and also, like Elvis, live forever (Roach

2007: 69-71). I believe that the book musical form presents a fictive world

in which non-celebrities have effigies, and therefore two bodies simultane-

ously, one mortal and one immortal. The effectiveness of 'Rose's Turn' in

performance is best understood as pushing this fiction to its limit, until it

finally falls apart.

-

7/29/2019 'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

3/8

My thesis is inspired by Scott McMillin's struggle to articulate the nature

of the sung character in The Musical as Drama (2006). When describing

what happens to a character when it is given musical voice, McMillin's

language takes its place among centuries of vague descriptions of the seem-

ingly magical, mesmerizing quality of 'It'. He writes that music 'carries the

characters into new versions of themselves', that it 'intensiljiesj the dra-

matic moment and give[sj it a special glow of performance' (McMillin

2006: 42, 52). Characters with songs are 'larger' than others because the

songs 'extend their characters musically' (McMillin 2006: 67).

To understand the relationship between this mystical language and the

'It' effect of musical theatre characters, it is necessary to place McMillin's

descriptions in relation to his larger argument about musical theatre dram-

aturgy. In contrast to the long-running discourse of the 'integrated musi-

cal', McMillin places the 'crackle of difference' between spoken dialogue

and music at the centre of the musical's dramatic structure (McMillin

2006: 2). He then divides the musical into two temporal realities. Both plot

and character, he argues, are built on 'the tension between two orders of

time, one for the book and one for the numbers' (McMillin 2006: 6). The

former order of time 'moves [...] from a beginning through a middle to an

end' and is 'organized by cause and effect' McMillin 2006: 6-9), while the

latter 'is organized [...] by principles of repetition' and 'suspends book time'

through 'the repeated combinations of phrases and rhythms' (McMillin

2006: 9, 31 ). In other words, 'book time' is a mimetic representation of the

time of our everyday, or offstage, lives - lives that follow clocks, narrative

progression and order. 'Lyric time', on the other hand, is a representation

of a more radical experience of temporality, in which time moves not for-

ward but around, and seems to circle back on itself. From the character's

perspective, thanks in large part to the refrain around which most musical

theatre songs are structured, 'engagement in the song itself is not dialecti-

cal, it is not progressive, it is repetitive' (McMillin 2006: 37).

What emerges, then, is the stable effigy of the singing character over

and above the mortal character-in-speech. McMillin's two orders of time,

one built on progression and the other on stasis, are perfectly conditioned

to generate the 'two bodies' of Roach's celebrities. The character, when

not singing, moves and speaks with his or her 'body natural' - recogniza-

ble, humble, mortal. When the character 'rises' in song, however, the

'body cinematic', the effigy, takes over, frozen in time by the Utopian,

repetitive space of the lyric, which risks a semiotic collapse by seeming to

be 'a line that signifies itself, if such a thing were possible' (McMillin 2006:111). For audience members, then, musical theatre involves watching

'real' people (i.e. people who live in narrative 'book time') transcend the

limitations of the mundane self to gain, in essence, immortality.

The immortal, lyric 'self is stable, because it is frozen in time, as

opposed to the more mutable book 'self. As a result, this transformation,

most pronounced if not unique in the musical,1 is one possible explanation

for why characters prefer to announce their identities in lyric time than in

book time. Consider the preponderance of musical theatre songs that

announce and celebrate the self. The list of examples includes many of the

greatest songs in the musical theatre canon: 'I'm Just a Girl Who Can't

Say No', T Am What I Am', 'I'm Still Here', 'And I Am Telling You I'm

It is worth exploring

whether a similar

process divides recita-

tive from aria in

opera, for example.

-

7/29/2019 'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

4/8

Not Going', 'Hello, Dolly', '(I'm Only a) Cock-eyed Optimist', 'My Time of

Day', '(I Am) Sixteen Going on Seventeen', '(My) Corner of the Sky', 'Don't

Cry for Me Argentina'. And let us not forget that the point of 'Some People'

is to get to the essence of Rose's character, and that each performance of

'Let Me Entertain You' begins with, 'Hello everybody, my name's_!'

It is crucial to remember, however, that the pleasure of the musical for

the spectator - the pleasure of vicarious participation in a world in which

people (characters) speak through their effigies - is built on the fundamen-

tal illusion of the theatre. The art of'It' is a performer's art. The icon of the

fallen but fierce Effie White in the original production of Dreamgirls, for

example, would not have been possible without Jennifer Holliday's physi-

cal and vocal performance. Eurthermore, an audience is necessary to

receive the 'It' performance, to hear the repetitive rhythmic structure of its

music, and so to construct a character's effigy in lyric time. This aporia in

the effigy-building project of musical theatre, then, yields a tension: on the

one hand, audience members may vicariously claim the expressive powers

of the musical's major characters, available only in the lyric time of musi-

cal performance, as their own. On the other hand, as is true of any audi-

ence member's vicarious experience, it is the relationship between

performer and spectator, structured within the frame of theatrical fiction-

making, that creates those expressive powers in the first place.

In most musicals, this tension is productive; it yields the playfulness of

musical theatre. Gypsy is no exception, until Momma Rose sings 'Rose's

Turn', at which point she pushes the limits of the game too far, by trying to

claim the privileges of it' without the need of either performer or audience.

It is no surprise that Gypsy, through 'Rose's Turn', problematizes the

relationship between the book musical and the celebrity effigy. The very

subject of Gypsy is the musical theatre's potential to create stars. Gypsy

engages this subject matter by being a backstage musical, and thus employ-

ing both diegetic and non-diegetic musical numbers. The latter, which

McMillin calls 'out-of-the-blue numbers' (McMillin 2006: 112), are songs

that, unlike diegetic numbers, are not recognized as performances in the

world of the book. Examples of diegetic numbers include 'Honey Bun' from

South Pacific, 'A Bushel and a Peck' from Guys and Dolls and i Am What I

Am' from La Cage Aux Folks, all of which are performed by characters to

imaginary audiences, sometimes represented onstage but more often stood

in for by the real-world spectators. McMillin argues that the principle of

character 'expansion', the ability to create time-stopping effigies, is the

same in both categories-

'a pause [in book time] is a pause even when the

characters in the book hear it as a pause' (McMillin 2006: 105). But

because diegetic numbers create an inner performer-spectator relationship

within the fictive world constructed by the actual spectators, they are use-

ful in generating a meta-theatrical awareness of the musical's form.

Gypsy is built on the difference between diegetic and non-diegetic num-

bers, and calls its characters by different names depending on which kind

of number they're performing. During 'When Momma was Married' or

'Little Lamb', for example, the onstage characters are named June and

Louise. When performing their various iterations of 'Let Me Entertain

You', the same characters become Dainty June, Caroline the 'Moo' Cow

and, later, Gypsy Rose Lee. These latter figures are the effigies of June and

-

7/29/2019 'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

5/8

Louise. Approaching this phenomenon from a different theoretical perspec-

tive, Philip Auslander might refer to the diegetic versions of these charac-

ters as their 'musical personae', which, he argues, are the identities that

musicians 'perform' when they play or sing for their audiences in concerts

and other non-dramatic contexts (Auslander 2006: 102).2 Auslander

makes a similar argument for the relationship between spectator and con-

cert musician that 1 do between spectator and musical theatre character:

'Personae are always negotiated between musicians and their audiences

[...]. This suggests that the audience, not the performer, plays the most

decisive role in the process of identity formation' (Auslander 2006: 114).

Auslndern musical persona and Roach's celebrity effigy meet at the same

vanishing point: the indelible image produced by the star.

In the case of Dainty June, the spectator most responsible for construct-

ing her persona is not the fictional audience of the vaudeville circuit, but

Momma Rose herself, who conjures up Dainty June through sheer will

and vision. Rose positions herself, then, between the real-world audience

of Gypsy and the imaginary audiences of the diegetic numbers, and she

seems, at times, to occupy both roles. Her entrance cuts through both

spaces by 'coming down the aisle', as the stage directions indicate, 'and

onto the stage' (Laurents et al. 1994: 5),3 crossing first the boundary

between real-world audience and real-world stage, and then the boundary

between Uncle Jocko's audience and Jocko's own stage. Gypsy's audience

members may realize, at this moment, that while Rose was standing

behind them, they were sharing her point of view. Since diegetic numbers

ask the audience to stand in for the imaginary audience of the onstage fic-

tion, so the audience of Gypsy always remains aligned, in perspective if not

always in sympathy, with Rose.

To carry the point even further, Rose's relationship with her daughters

parallels the vicarious relationship between audience and musical theatre

character I've already described. She wants to be the star that she turns

her daughters into - knowing every line and movement of the Dainty June

numbers and, in at least one instance, forcing herself onstage with them

(Laurents et al. 1994: 41). At the same time, Rose holds firm to her posi-

tion as prime spectator - as Momma, continuously birthing her daughters'

onstage identities. When D.A. Miller describes 'the stage' of Gypsy as an

'extension, a universalisation' of the 'body of [the] Stage Mother' (Miller

1998: 74), he correctly identifies Momma Rose's power to construct, at

least in part, the musical world before us. But the metaphor should be

adjusted: she is an extension not of the stage but of the audience. This

principle only increases as the plot moves forward. The more grotesque

Dainty June's performances become, as she grows older and more inap-

propriate for the part, the more Rose becomes the only spectator whose

gaze constructs Dainty June out of June Havoc, ironically making June

even more Rose's exclusive property (until, of course, June's courageous

escape, when she disappears from Rose's view and, consequently, ours).

Significantly, Rose never has a diegetic number of her own. In terms of

Gypsy's fictional plot, if Rose were ever given her own stage time, she

would no longer require her daughters to fulfil her dream of stardom, and

the play would be over. In terms of Gypsy as a theatrical event, the same

is true. The precarious system of vicariousness and embodiment between

2. Auslander adapts his

terminology from

David Graver.

3. The stage directions

state that Rose's

voice is first heard

'from out front', and

that she enters by

'coming down the

aisle and onto the

stage' (Laurents et al.

1994: 5).

-

7/29/2019 'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

6/8

Rose and her daughters, and between the audience and Rose, that has

underlain the entire performance of Gypsy, breaks down in 'Rose's Turn'.

The drama of that number is the attempt by Rose to close the gap between

these two polarities, vicariousness and embodiment, and so to gain it', the

king's two bodies, without the assistance of an outside gaze. Rose even

speaks of an effigy that is within her, pleading for release - 'what I been

holding down inside of me' (Laurents et al. 1994: 104).

By the end of the secondact,

Rose, the perpetual spectator, has become

displaced. After working tirelessly to make first June and then Louise into

vaudeville stars, Louise has become a star of burlesque, proving that it' is

not exclusive to the imprurient. Though pushed onstage by Rose's own

hand, the newly emergent Gypsy Rose Lee negates Rose's role as both

mother and spectator. Gypsy's audience is worldwide, and her persona is

not constructed by Rose, who, in defiance, brings Louise her cow head

from the Dainty June act to remind her that her 'goal was to become a

great actress, not a cheap stripper' (Laurents et al. 1994: 99). More funda-

mentally, in her new role, Gypsy is quite literally not a child anymore: i'm

not my mothah!' she tells her audience as she removes her dress, inflicting

untold pain on her actual mother's ego (Laurents et al. 1994: 96).

With no star left to erect and no children left to mother, Rose tries at

last to turn her powers onto herself. When she declares to Gypsy, i made

you!' she implies that the audience's power to construct a star includes the

power to become one itself, and she goes on to test this theory. But even

from this opening moment, Rose is trapped in the language of the specta-

tor. Whether 'You [...] got it,/or you ain't' is the audience's prerogative, as

is the right to announce the performer in the third person: 'Ready or not,

here comes Momma!' (Laurents et al. 1994: 105). In effect, she is trying to

see, herself into celebrity. That she is unable to pronounce her own identity,

'Momma', is the first indisputable sign of failure: she cannot be audience

and performer, mother and child, subject and object, at once.

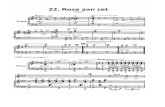

The song itself is markedly different from Rose's two prior star turns,

'Some People' and 'Everything's Coming Up Roses'. These numbers are

built on traditional, AABA (plus variations) popular song formats, with

predictable inner repetitions and refrains heard by the audience, lifting

Rose's character into lyric time as so many musical characters have done

before her. 'Rose's Turn', on the other hand, is built from the scraps of

these and other earlier songs, suggesting that Rose herself has heard them,

as we have, and that she is trying to capture for herself the glory with

which we have imbued her.

The music is dissonant, and no refrain is maintained for long, but Rose

almost succeeds in her ambition. 'Rose's Turn' would not be memorable if

it did not create, in the real-world audience, the impression of a woman

who is able to call forth her immortal effigy at will. Rose wills herself as

her own audience, wills her own musical persona, and so 'Rose's Turn'

appears to be a number that is neither diegetic (evoking an imaginary,

onstage audience) nor non-diegetic (heard only by the real-world audi-

ence), but liminal, and so somehow, daringly, real. This liminality is what

is so compelling about 'Rose's Turn'. The intensity of Rose's need to gain

an immortal 'body cinematic' is no less than the audience members' to

gain ones for themselves, as Gypsy, up to that point, has lured both the

-

7/29/2019 'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

7/8

audience and the character into a fictive belief in any individual's poten-

tial to become a star. 'Rose's Turn' creates the daring excitement that that

potential can be realized.

The effect of Rose's becoming her own spectator is achieved by break-

ing the harmony between musical theatre performer and character, steal-

ing the microphone from, in this case, Patti LuPone. D.A. Miller describes

it best: 'Rose has become the negation of the Star who plays her', or at

least, she has tried to (Miller 1998: 117). For if Rose's project were indeed

successful, she should be able to walk off the stage and through the audi-

ence (from whence she came), leaving LuPone behind, since she no longer

requires her assistance, or ours, to become a living effigy of herself.

LuPone's continuing to bow beyond the applause at the end of the

number is terrifying because, for a moment, we had believed Momma Rose

had succeeded, or at least, we had wanted to believe so badly that we had

stood up and applauded her, asking her to accept our presence and adora-

tion. For a split second of perception, the effigy had become more real than

the performer who created her. Of course, to applaud for a character rather

than an actor is madness. If LuPone, like Ethel Merman in the original

production o Gypsy, had broken character, I could have immediately disa-

vowed my lapse of rationality. Of course, I might have said if I were there,

I'm giving a standing ovation to the star performer. But by effacing her-

self, LuPone abandoned me when I needed her most. Louise's entrance

reasserted the semiotics of theatrical fiction-making - only characters

applaud for other characters - leaving Rose trapped, as before, in the fic-

tional world of Gypsy, with her mundane body natural. I, having applauded

a now-vanished effigy, was left to reckon with myself, as the surviving

witness to Rose's mad, but seductive, dream.

References

Auslander, Philip (2006), 'Musical Personae', The Drama Review, 50: 1, pp. 100-19.

Garebian, Keith (1994), The Making of Gypsy, Toronto: ECW Press.

Laurents, Arthur, Sondheim, Stephen and Styne, Jule (1994), Gypsy, New York:

Theater Communications Group.

McMillin, Scott (2006), The Musical as Drama, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Miller, D.A. (1998), A Place for Us: Essay on the, Broadway Musical, Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Roach, Joseph (2007), it, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Suggested citation

Fitzgerald, J. (2009), "I had a dream': 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star

effigy', Studies in Musical Theatre 3: 3, pp. 285-291, doi: 10.1386/smt.3.3.285/l

Contributor details

Jason Fitzgerald earned his MFA in Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism from Yale

School of Drama in 2008, and his AB from Harvard College in 2004. He is cur-

rently a teaching fellow at Yale College and a freelance theatre reviewer in New

York City.

-

7/29/2019 'I had a dream' - 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

8/8

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Title:

Source:

ISSN:

DOI:

Publisher:

'I had a dream': 'Rose's Turn', musical theatre and the star effigy

Stud Musical Theatre 3 no3 2009 p. 285-91

1750-3159

10.1386/smt.3.3.285/1

Intellect Ltd.

The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds, Bristol BS16 3JG, United Kingdom

The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it is reproduced

with permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is

prohibited. To contact the publisher:http://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/journals.php?issn=17503159

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or makeany representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independentlyverified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoevercaused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.