Hydrocephalus

-

Upload

govindaraju-subramani -

Category

Documents

-

view

122 -

download

0

Transcript of Hydrocephalus

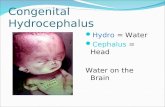

HYDROCEPHALUS

Evidence Base

Cartwright, C.C., and Wallace, D.C. (2007). Nursing care of the pediatric

neurosurgery patient. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

Hydrocephalus is characterized by an increased volume of cerebrospinal

fluid (CSF), which is associated with progressive ventricular dilatation. There are

two main categories of hydrocephalus: communicating and noncommunicating.

Hydrocephalus occurs with such conditions as tumors, infections, congenital

malformations, and hemorrhage. The incidence of hydrocephalus is 0.5 to 4 per

1,000 live births.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Noncommunicating hydrocephalus—obstruction of CSF flow within the

ventricular system; or, blockage of CSF flow from the ventricular system to

the subarachnoid space.

o May be partial, intermittent, or complete.

o More common than communicating type.

o Congenital causes

Aqueductal stenosis

Congenital lesions (vein of Galen malformation, congenital

tumors)

Arachnoid cyst

Chiari malformations (with or without myelomeningocele)

X-linked hydrocephalus

Dandy-Walker malformation

o Acquired causes

Aqueductal gliosis (post-hemorrhagic or postinfectious)

Space-occupying lesions (tumors or cysts)

Head injuries

Communicating hydrocephalus—CSF circulates through the ventricular

system into the subarachnoid space with no obstruction.

o Congenital causes

Achondroplasia

Arachnoid cyst

Craniofacial syndromes

o Acquired causes

Post-hemorrhagic (intraventricular or subarachnoid)

Choroid plexus papilloma or choroid plexus carcinoma

Venous obstruction (eg, superior vena cava syndrome)

Post-infectious

Clinical Manifestations

May be rapid, slow and steadily advancing, or intermittent. Clinical signs

depend on the age of the child, whether the anterior fontanelle has closed, whether

the cranial sutures have fused, and the type and duration of hydrocephalus.

Infants

Excessive head growth (may be seen up to age 3).

Delayed closure of the anterior fontanelle.

Fontanelle tense and elevated above the surface of the skull.

Signs of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) (see Box 46-1).

Alteration of muscle tone of the extremities, including clonus or spasticity.

Later physical signs:

o Forehead becomes prominent (“bossing”).

o Scalp appears shiny with prominent scalp veins.

o Eyebrows and eyelids may be drawn upward, exposing the sclera

above the iris.

o Infant cannot gaze upward, causing “sunset eyes.”

o Strabismus, nystagmus, and optic atrophy may occur.

o Infant has difficulty holding head up.

o Child may experience physical or mental developmental lag.

Pseudobulbar palsy (difficulty sucking, feeding, and phonation, which leads

to regurgitation, drooling, and aspiration).

BOX 46-1 Signs and Symptoms of Increased ICP in Infants and Children

▪Vomiting

▪Restlessness and irritability

▪High-pitched, shrill cry (infants)

▪Rapid increase in head circumference (infants)

▪Tense, bulging fontanelle (infants)

▪Changes in vital signs:

-Increased systolic blood pressure

-Decreased pulse

-Decreased and irregular respirations

-Increased temperature

▪Pupillary changes

▪Papilledema

▪Possible seizures

▪Lethargy, stupor, coma

▪Older children may also experience:

-Headache, especially on awakening

-Lethargy, fatigue, apathy

-Personality changes

-Separation of cranial sutures (may be seen in children up to age 10)

-Visual changes such as double vision

NURSING ALERT

It is important to measure head circumference because the infant's skull is highly

elastic and can accommodate an increase in ventricular size. Ventriculomegaly

may progress without obvious signs of increased ICP.

Older Children

Older children have closed sutures and present with signs of increased ICP.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Infant's head transilluminates, indicative of abnormal fluid collection (rarely

used).

Percussion of the infant's skull may produce a typical “cracked pot” sound

(MacEwen's sign).

Ophthalmoscopy may reveal papilledema.

MRI is the diagnostic tool of choice.

CT is also used for diagnosis in cases where sedation poses added risk due to

need for general anesthetic or in situations in which MRI is not available.

Management

Hydrocephalus can be treated through a variety of surgical procedures, including

direct operation on the lesion causing the obstruction, such as a tumor; intracranial

shunts for selected cases of noncommunicating hydrocephalus to divert fluid from

the obstructed segment of the ventricular system to the subarachnoid space; and

extracranial shunts (most common) to divert fluid from the ventricular system to an

P.1548

extracranial compartment, frequently the peritoneum or right atrium. CSF

production may also be reduced by medication or surgical intervention.

FIGURE 46-1 A ventriculoperitoneal shunt removes excessive cerebrospinal fluid

from the ventricles and shunts it to the peritoneum. A one-way valve is present in

the tubing behind the ear.

Extracranial Shunt Procedures

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt (see Figure 46-1):

o Diverts CSF from a lateral ventricle or the spinal subarachnoid space

to the peritoneal cavity.

o A tube is passed from the lateral ventricle through an occipital burr

hole subcutaneously through the posterior aspect of neck and

paraspinal region to the peritoneal cavity through a small incision in

the right lower quadrant.

o A ventricular access device is an implanted reservoir and catheter

used for premature neonates less than 2,000 g in lieu of a shunt. The

catheter drains fluid from the ventricles into the reservoir, which can

then be emptied using aseptic technique. When infant weight exceeds

2,000 g a shunt can be placed.

Ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt:

o A tube is passed from the dilated lateral ventricle through a burr hole

in the parietal region of the skull.

o It then is passed under the skin behind the ear and into a vein down to

a point where it discharges into the right atrium or superior vena cava.

o A one-way pressure-sensitive valve will close to prevent reflux of

blood into the ventricle and open as ventricular pressure rises,

allowing fluid to pass from the ventricle into the bloodstream.

Ventriculopleural shunt:

o Diverts CSF to the pleural cavity.

o Indicated when the VP or VA route cannot be used.

Ventricle-gall bladder shunt:

o Diverts CSF to the common bile duct.

o Used when all other routes are unavailable.

Most shunts have the following components:

o Ventricular tubing.

o A one-way or unidirectional pressure-sensitive flow valve.

o A pumping chamber.

o Distal tubing.

Programmable shunts are available. These can be programmed to a certain

flow pressure, and pressure settings can be readjusted based upon patient

response. A magnetic device is used to adjust the pressure setting of the

shunt valve. The use of a programmable shunt eliminates the need for

multiple surgeries or hospital visits to adjust shunt pressure.

Shunt Complications

Need for shunt revision frequently occurs because of occlusion, infection, or

malfunction, especially in the first year of life.

Shunt revision may be necessary because of growth of the child. Newer

models, however, include coiled tubing to allow the shunt to grow with the

child.

Shunt dependency frequently occurs. The child rapidly manifests symptoms

of increased ICP if the shunt does not function optimally. Onset may be

sudden or insidious.

Children with VA shunts may experience endocardial contusions and

clotting, leading to bacterial endocarditis, bacteremia, and ventriculitis or

thromboembolism and cor pulmonale.

Children with VA shunts require biannual or annual chest X-ray to check

length of tubing. Chest X-ray is also done during growth spurts, especially

during puberty. When tubing is short or close to being out of the right

atrium, shunt replacement needs to be scheduled.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on early diagnosis and prompt therapy and the underlying

etiology.

With improved diagnostic and management techniques, the prognosis is

becoming considerably better.

o Many children experience normal motor and intellectual development.

o The severity of neurologic deficits is directly proportional to the

interval between onset of hydrocephalus and the time of diagnosis.

Approximately two-thirds of patients will die at an early age if they do not

receive surgical treatment.

Surgery reduces mortality and decreases morbidity with a survival rate of

greater than 90%.

Complications

Seizures.

Herniation of the brain.

Spontaneous arrest due to natural compensatory mechanisms, persistent

increased ICP, and brain herniation.

Developmental delays.

Depression in adolescents is common.

Nursing Assessment

Infants

Assess head circumference.

o Measure at the occipitofrontal circumference—point of largest

measurement.

o Measure the head at approximately the same time each day.

o Use a centimeter measure for greatest accuracy.

Palpate fontanelle for firmness and bulging.

Assess pupillary response.

Assess level of consciousness (LOC).

Evaluate breathing patterns and effectiveness.

Assess feeding patterns and patterns of emesis.

Assess motor function.

Assess developmental milestones.

Older Children

Measure vital signs for signs of increased ICP.

Assess patterns of headache, emesis.

Determine pupillary response.

Evaluate LOC using the Glasgow Coma Scale.

Assess motor function.

Evaluate attainment of milestones, school performance.

Assess for behavioral changes.

Nursing Diagnoses

Ineffective Cerebral Tissue Perfusion related to increased ICP before surgery

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to reduced oral

intake and vomiting

Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity related to alterations in LOC and enlarged

head

Anxiety of parents related to child undergoing surgery

Risk for Injury related to malfunctioning shunt

Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume related to CSF drainage, decreased intake

postoperatively

Risk for Infection related to bacterial infiltration of the shunt

Ineffective Family Coping related to diagnosis and surgery

Nursing Interventions

Maintaining Cerebral Perfusion

Observe for evidence of increased ICP, and report immediately.

Assist with diagnostic procedures to determine cause of hydrocephalus and

indication for surgical intervention.

o Explain the procedure to the child and parents at their levels of

comprehension.

o Administer prescribed sedatives 30 minutes before the procedure to

ensure their effectiveness.

o Organize activities so that the child is permitted to rest after

administration of the sedative.

o Observe closely after ventriculography for the following:

Leaking CSF from the sites of subdural or ventricular taps.

These tap holes should be covered with a small piece of gauze

or other dressing per institutional policy.

Reactions to the sedative, especially respiratory depression.

Changes in vital signs indicative of shock.

Signs of increased ICP, which may occur if air has been

injected into the ventricles.

NURSING ALERT

Brain stem herniation can occur with increased ICP and is manifested by

opisthotonic positioning (flexion of head and feet backward). This is a grave sign

and may be followed by respiratory arrest. Prepare for emergency resuscitation and

corrective measures as directed.

DRUG ALERT

Sedatives are contraindicated in many cases because increased ICP predisposes the

child to hypoventilation or respiratory arrest. If they are administered, the child

should be observed very closely for evidence of respiratory depression.

Providing Adequate Nutrition

Be aware that feeding is frequently difficult because the child may be

listless, have a diminished appetite, and be prone to vomiting.

Complete nursing care and treatments before feeding so that the child will

not be disturbed after feeding.

Hold the infant in a semi-sitting position with head well supported during

feeding. Allow ample time for bubbling.

Offer small, frequent feedings.

Place the child on side with head elevated after feeding to prevent aspiration.

Maintaining Skin Integrity

Prevent pressure sores (pressure sores of the head are a frequent problem) by

placing the child on a sponge rubber or lamb's wool pad or an alternating-

pressure or egg-crate mattress to keep weight evenly distributed. Be mindful

of latex allergies and the type of padding used.

Keep the scalp clean and dry.

Turn the child's head frequently; change position at least every 2 hours.

o When turning the child, rotate head and body together to prevent

strain on the neck.

o A firm pillow may be placed under the child's head and shoulders for

further support when lifting the child.

o Keep weight off incision during immediate postoperative period.

Provide meticulous skin care to all parts of the body, and observe skin for

signs of breakdown or pressure.

Give passive ROM exercises to the extremities, especially the legs.

Keep the eyes moistened with artificial tears if the child is unable to close

the eyelids normally. This prevents corneal ulcerations and infections.

Reducing Anxiety

Prepare the parents for their child's surgery by answering questions,

describing what nursing care will take place postoperatively, and explaining

how the shunt will work.

Encourage the parents to discuss all the risks and benefits with the surgeon.

Help them to understand the prognosis and what to expect of the child's

neurologic and cognitive development.

Prepare the child for surgery by using dolls or other forms of play to

describe what interventions will occur.

Improving Cerebral Tissue Perfusion Postoperatively

Monitor the child's temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure (BP), and

pupillary size and reaction every 15 minutes until stable; then monitor every

1 to 2 hours or as indicated by child's condition and institutional policy.

Maintain normothermia.

o Provide appropriate blankets or covers, an Isolette or infant warmer,

or hypothermia blanket.

o Administer a tepid sponge bath or antipyretic medication for

temperature elevation.

Aspirate mucus from the nose and throat, as necessary, to prevent respiratory

difficulty.

Turn the child frequently.

Promote optimal drainage of CSF through the shunt by pumping the shunt

and positioning the child as directed.

o If pumping is prescribed, carefully compress the valve the specified

number of times at regularly scheduled intervals.

o Report any difficulties in pumping the shunt.

o Gradually elevate the head of child's bed to 30 to 45 degrees as

ordered. Initially, the child will be positioned flat to prevent excessive

CSF drainage.

Assess for excessive drainage of CSF.

o Sunken fontanelle, agitation, restlessness (infant).

o Decreased LOC (older child).

Assess closely for increased ICP, indicating shunt malfunction.

o Note especially change in LOC, change in vital signs (increased

systolic BP, decreased pulse rate, decreased or irregular respirations),

vomiting, pupillary changes.

o Report these changes immediately to prevent cerebral hypoxia and

possible brain herniation.

Prevent excessive pressure on skin overlying shunt by placing cotton behind

and over the ears under the head dressing and avoiding positioning the child

on the area of the valve or the incision until the wound is healed.

Maintaining Fluid Balance

Accurately measure and record total fluid intake and output.

Administer I.V. fluids as prescribed; carefully monitor infusion rate to

prevent fluid overload.

Use a nasogastric tube, if necessary, for abdominal distention.

o This is most frequently used when a VP shunt has been performed.

o Measure the drainage, and record the amount and color.

o Monitor for return of bowel sounds after nasogastric suction has been

disconnected for at least 30 minutes.

Give frequent mouth care while the child is to have nothing by mouth.

Begin oral feedings when the child is fully recovered from the anesthetic and

displays interest.

o Begin with small amounts of dextrose 5% in water.

o Gradually introduce formula.

o Introduce solid foods suitable to the child's age and tolerance.

o Encourage a high-protein diet.

o Observe for and report any decrease in urine output, increased urine

specific gravity, diminished skin turgor, dryness of mucous

membranes, or lethargy, indicating dehydration.

Preventing Infection

Assess for fever (temperature normally fluctuates during the first 24 hours

after surgery), purulent drainage from the incision, or swelling, redness, and

tenderness along the shunt tract.

Administer prescribed prophylactic antibiotics.

NURSING ALERT

All children who have had surgery require pain assessments. Although pain

management is institutionspecific, acetaminophen is often the medication of

choice. Also use alternative modes of pain management, such as distraction and

relaxation techniques and ensuring a quiet environment.

Strengthening Family Coping

Begin discharge planning early, including specific techniques for care of the

shunt and suggested methods for providing daily care.

o Turning, holding, and positioning.

o Skin care over shunt.

o Exercises to strengthen muscles—incorporated with play.

o Feeding techniques and schedule.

o Pumping the shunt.

Accompany all instructions with reassurance necessary to prevent the

parents from becoming anxious or fearful about assuming the care of the

child.

Help the parents to assist siblings to understand hydrocephalus and the

child's special needs. Encourage parents to spend individual time with

siblings and not to neglect their needs as well. Suggest family counseling if

needed.

Assist parents in locating additional resources.

o Social worker, discharge planner, or department of social services.

o Visiting or home health nurses or aides.

o Parent groups.

o Community agencies.

o Special programs at school.

Community and Home Care Considerations

Follow the community and home care considerations listed under Cerebral

Palsy on page Check shunt functioning regularly, and reinforce parental

performance of shunt checks and assessment for shunt malfunction and

increased ICP.

Perform total physical assessment regularly, looking for signs of trauma or

skin breakdown.

Patient should wear a MedicAlert bracelet when he or she starts to attend

school or daycare.

Make sure that parents or caregivers are certified in cardiopulmonary

resuscitation (CPR).

Family Education and Health Maintenance

Stress the importance of recognizing symptoms of increased ICP and

reporting them immediately.

Advise parents to report shunt malfunction or infection immediately to

prevent increased ICP.

Teach parents that illnesses that cause vomiting and diarrhea or illnesses that

prevent an adequate fluid intake are a great threat to the child who has had a

shunt procedure. Advise parents to consult with the child's health care

provider about immediate treatment of fever, control of vomiting and

diarrhea, and replacement of fluids.

Tell the parents that few restrictions are required for children with shunts

and to consult with the health care provider about specific concerns.

Alert parents that additional information and support are available from the

Hydrocephalus Association, www.hydroassoc.org.

FIGURE 46-2 Spina bifida. (A) Normal spine. (B) Spina bifida occulta. (C) Spina

bifida with meningocele. (D) Spina bifida with myelomeningocele.

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

No changes in vital signs, LOC, or head size; no vomiting; pupils equal and

responsive

Feeds every 4 hours without vomiting; no significant weight loss

No erythema, blanching, or skin breakdown; wound healing evident

Parents verbalizing purpose and type of operative procedure, risks, and

benefits

Shunt pumping without resistance; stable LOC and vital signs

Urine output equal to intake; skin turgor normal; electrolytes within normal

limits

Afebrile; no drainage from shunt site

Parents actively seeking resources, showing affection for patient and siblings